ABSTRACT

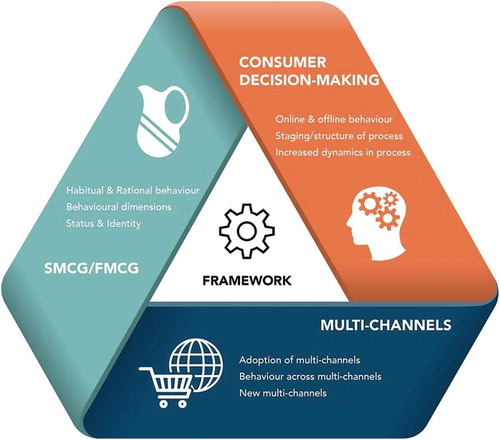

Currently, consumer decision-making is influenced by the spread of technology that has made multi-channel retailing possible. Multi-channel retailing can be defined as a retailer using a combination of separate and independent channels without any overlap for promoting and selling products and services. This study contributes to three research streams: consumer decision-making, multi-channel retailing and slow-moving consumer goods (SMCG). A theoretical framework is developed to examine the decision-making processes of two groups of consumers, Millennials and Mothers. As the aim of the study was to gain insight into consumer decision-making in the context of multi-channels it was designed to be exploratory and used an abductive approach. The empirical material was mainly collected via interviews in store and consumers’ homes. The interview data are complemented by in-store observations. Our findings show that multi-channels influence consumers’ decision-making and that there are differences between Millennials and Mothers. Different devices and channels are used at different stages of the decision-making process and we claim that they complement, rather than conflict with each other. Retailers need to understand that customers expect omni-channelling, which has a positive impact on brand and sales. We argue that retailers who want to remain competitive will need to move toward omni-channelling.

Introduction

Consumer decision-making plays a major role in the contemporary consumer’s everyday life. Consumer decision-making is being influenced by the spread of technology which makes multi-channel retailing possible. Multi-channel retailing can be defined as the use of a combination of channels to promote and sell products and services (Lewis, Whysall, and Foster Citation2014). To use two or more channels is not a new phenomenon, but the integration of them is, and the number of retailers using two or more channels has also increased (Lewis, Whysall, and Foster Citation2014).

Until recently there were two main channels for the distribution of goods, the website and the traditional store. These two channels have been treated as independent (Pantano and Viassone Citation2014). Communication via online channels no longer consists simply of two-way interactions between companies and consumers (Neslin et al. Citation2006); online channels also enable consumers to communicate with other consumers and with competitors. The boundaries between online and offline have been steadily eroding as new technologies have removed informational and geographical barriers (Brynjolfsson, Hu, and Rahman Citation2013). Today consumers have access to more information and can migrate across channels faster than ever before; decision-making is also more sophisticated (Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman Citation2015).

The increase in online channels, interconnectivity and mobility has affected the decision-making process and retailers need to adapt to this new environment. The challenge is to adapt these new technologies to be able to offer customers an efficient and pleasant shopping experience (Tyc Citation2013) and satisfy their expectations.

The number of customers who like to use multiple channels to shop is increasing. The increase in multi-channel customers has occurred because customers perceive that there are benefits to using multiple channels (Yan Citation2008). The purchase process has become highly personal, which is challenging for retailers. Retailers need a presence on existing platforms and need to integrate their presence on various platforms channels to remain competitive. Swedish multi-channel consumers spend approximately 40% more than single-channel consumers, which is another incentive for retailers to use multi-channels (E-Barometern Citation2016).

One can assume differences in the consumption habits of younger and older people. Younger people grew up in the digital world and one would expect them to make more extensive use of online channels than older generations. As today’s younger generations grow older their purchasing power increases and they will become retailers’ main target group. To capture the different patterns of consumer decision-making we focused on two groups of consumers that we will call Millennials and Mothers. Millennials are digitally literate, capable of multi-tasking and operate at ‘twitch speed’ (Karakas, Manisaligil, and Sarigollu Citation2015). Multi-channel shopping is natural for them and it is important to understand it is this generation’s decision-making processes that will influence the design of future retail distribution. Millennials are also interesting due to the time, energy and effort they spend, compared with previous generations, on high-involvement products (Parment Citation2013). This is something that could affect their decision-making.

There is already research into consumer decision-making about fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) (Kalnikaitė, Bird, and Rogers Citation2012; Campo and Breugelmans Citation2015; Chu et al. Citation2010) and one could question why it is not possible to apply this research to the category slow-moving consumer goods (SMCG) and whether there is a need for a new theory to deal with the multi-channel context. Findings from research on FMCG cannot be generalised to SMCG because the decision-making processes are different. Nordfalt (Citation2005) claimed that decisions about FMCG are spontaneous because only 35% of customers plan their decisions in advance. The consumer decision-making process for FMCG and goods that move at a medium rate is probably less rational and harder to grasp because decisions are made quickly and largely unconsciously.

SMCG are associated with rational and cognitive behaviour, high involvement and more complex decisions (Hamiln and Wilson Citation2004). We believe the decision process is slower and involves more steps than in the case of FMCG. Given the differences in how decisions are made about different categories of goods and the lack of research on SMCG, we argue that there is a need for a theory explaining the consumer decision-making within SMCG in a multi-channel context.

The aim of this study was to address this gap in knowledge by answering two specific research questions:

RQ1: How do different devices/channels influence the various stages of the consumer’s decision-making process?

RQ2: How does the availability of multi-channels influence the consumer decision-making for Millennials and Mothers?

The turnover from e-commerce is 6.9% of total retail turnover in Sweden and it increased by 19% during 2015. A recent report stated that technological advances would change consumer behaviour (E-Barometern Citation2016). Furniture and home decoration is increasing at 34%. Home decoration is particularly interesting to study as it is a product category that was neglected by early online purchasers (Ecommercenews Citation2015), and information from E-Barometern (Citation2016) indicates that multi-channel retailing is bringing changes to this category. Goods in this category have the typical attributes of SMCG such as high involvement and durability. Consumers will probably spend time with the decision-making process. This study investigated decisions about home decoration products, a subdivision of SMCG, to elucidate the consumer decision-making process in the context of multi-channel retailing.

Theory

Consumer decision-making

Consumers’ decisions and behaviour are an essential strand of research in various fields within consumer science. Researchers started to develop models to describe consumers’ decision-making process.

The first generation of models are called grand models. The aim was to describe rational actions involved in consumer decision-making and the relationships between them. Karimi (Citation2013) mentions three main models by Nicosia, Howard and Sheth and Engel-Kollat-Black. The grand models have limitations in that they take a positivist approach instead of using the consumer perspective (Karimi Citation2013). In addition, research carried out in the 1970s and 80s called into question the rationality of consumers’ decision-making. Kahneman, Slovic, and Tversky (Citation1982) found that human decisions are affected by heuristic biases and that consumers’ ability to make rational decisions is limited. Despite these limitations, the grand theory models do capture the different stages of consumer decision-making and they have been adapted by later researchers.

These adaptations yielded another group of models, which Karimi (Citation2013) calls classical models; this group is characterised by straightforward processes and conceives the decision-making process as a multi-stage process. The models omit the interrelation of elements as they are highly individual (Karimi Citation2013). The backbone of most classical models is the Engel–Kollat–Blackwell (Engel, Blackwell, and Kollat Citation1978) grand theory, which breaks the decision-making process into phases: problem recognition, search, alternative evaluation, purchase and outcomes. Researchers have tried to adapt the original model from 1968 to suit contemporary conditions. One example is the Engel–Kollat–Blackwell (EKB) model (Blackwell, Miniard, and Engel Citation2006), which added two further stages to the original five-stage model from 1968. The increased use of Internet and the possibilities it has opened up have altered consumers’ decision-making processes and the classical models have become inadequate.

Ashman, Solomon, and Wolny (Citation2015) investigated whether the EKB model was still valid in today’s shopping environment given the participatory culture (e.g. social media). They claimed that the EKB model is still valid but could be extended or re-evaluated in light of the new, participatory online environment. People’s needs have not changed, but the mechanisms for satisfying them have. Ashman, Solomon, and Wolny (Citation2015) also claimed that the sequence and length of each stage of the decision-making process has been influenced by socialisation and digitisation. Some stages have become more time efficient whereas others now take longer. The decision-making stages are performed but each decision stage might be repeated, skipped or enhanced (Wolny and Charoensuksai Citation2014).

The widespread use of the Internet has made decision-making more complex than existing models indicate. The retailer is not the only source of information; other consumers can also provide information and so the retailer has less control over and impact on consumers’ behaviour. Customers switch channels and go through decision-making stages several times. In research and practice, there has been a shift towards dynamic models.

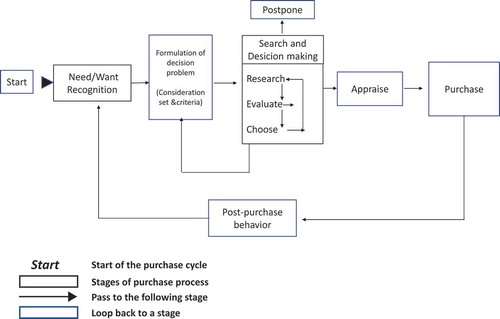

We regard the non-linearity of decision-making in a multi-channel context as theoretically important and so we decided to use Karimi’s (Citation2013) adaptation of the EKB model (2013) () to guide our research as it reflects the more dynamic nature of multi-channel decision-making, although it was developed to describe decision-making in relation to online channels.

Figure 1. Online purchase decision-making process model (adapted from Karimi Citation2013).

Multi-channel retailing

Multi-channel retailing is not a new phenomenon. An early example of a multi-channel retailer is Sears, which opened its first physical store in 1925 to complement the catalogues it had launched in 1886. The channels were not integrated in that era. It was not until the launch of the Internet that retailers started integrating the channels (Zhang et al. Citation2010). The introduction of online channels and the digitisation of society have changed the retail sector dramatically. The online channel has been a source of disruptive innovation in some retail sectors such as the travel industry (Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman Citation2015). Rigby (Citation2011) stated that the introduction of mobile channels can be viewed as another disruptor of the retail sector.

The new technologies allow consumers to use a variety of channels and thus switch between brands and retailers. Several channels can be used simultaneously, for example, one can search online for information in a physical store. The consumer is not limited to a specific retailer’s channels, which can have a negative impact on individual retailers. Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman (Citation2015) stated that experienced online shoppers tend to be less loyal to particular retailers. The spread of digitization had created a population of experienced online shoppers, which suggests that in the future consumers are likely to be less loyal to particular retailers.

Researchers have focused on the effects of adding online channels and the migration from offline to online channels. There has also been research into the effects of the increase in online channels, but there has been less investigation of the implications of channel integration (Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman Citation2015). The effects of mobile channels and apps on retail performance have also been investigated (Xu et al. Citation2014).

Rapid technological developments are a challenge for retailers. Rapp et al. (Citation2015) stated that consumers have started using mobile devices (tablets and smartphones) in physical stores to compare offers and search for information. The mobile channel is becoming the new mainstream shopping channel due to its superior availability and ease of use (Pantano and Timmermans Citation2014). Integration of online and offline channels leads to synergies rather than cannibalisation (Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman Citation2015), which should encourage retailers to adopt multiple channels. Kannan, Reinartz, and Verhoef (Citation2016) identified one major challenge for retailers, namely being able to trait and credit each valuable touchpoint the consumer encounters before the actual purchase. de Haan et al. (Citation2015) encouraged researchers to investigate the complementary ways in which different devices are being used and this study takes up that challenge.

Different channels are used interchangeably during the search and purchase process, which makes it difficult for the retailers to control which channels are used (Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman Citation2015). The adoption of mobile devices is an example of tools affecting the decision-making. The spread of social media and the participatory culture that has come with this has changed online behaviour dramatically. Social media allow customer-to-customer interactions without the involvement of the retailer, which is challenging for the retailer. The customer experience is based on a diverse range of touchpoints in different channels and media, which is challenging for retailers who are trying to provide a positive customer experience (Lemon and Verhoef Citation2016). Hall and Towers (Citation2017) investigated millennial shoppers and were surprised by the impact other people had on Millennials, which further reduces retailers’ impact and control.

We believe that the consumers’ channel preferences will change in favour of online channels and that the adoption rate of multi-channels will continue to increase. This would affect the decision-making process due to the characteristics of the new technologies, for example, availability and transparency. There is a possibility that consumers’ decision-making processes vary between channels and devices and this is something that we investigated. Findings from the research and the proposed theoretical framework is presented in .

Methodology

We explored the consumer’s decision-making process in depth, through an abductive approach as we were able to derive assumptions from previous research about consumer decision-making and multi-channels. Using an existing model (Karimi Citation2013) limited the analysis. Triangulation was used to increase the credibility and validity of the research (Bryman and Bell Citation2015). A thorough study of the topic was carried out before the start of the empirical work and a pre-interview was conducted to increase the validity of the data. The main method of data collection was in-depth interviews as our objective was to uncover underlying motivations and attain a deeper understanding of consumers’ decision-making processes (Malhotra Citation2010). We recorded six semi-structured, in-depth interviews (). Non-probability, convenience sampling was used (Malhotra Citation2010). This sampling method has limitations, for example, it may result in a biased sample and the results are not generalisable to the whole population. The aim of this exploratory study was not to produce generalisable findings but to generate ideas and insights, and so convenience sampling was appropriate (Malhotra Citation2010). This study is preliminary and we intend to carry out robust, quantitative research in the future. The data generated illustrates the decision-making process and was not intended to be used to develop a new model of the decision-making process.

Table 1. At home interviews.

The initial analysis consisted of independent interpretation of the transcripts by two of the authors. Two separate lists consisting of categories labelled after the consumer decision-making stages were generated. The two lists were merged into one of which we extracted themes and sub-themes. An example of the data analysis is how the theme ‘experienced time’ was generated from codes such as ‘time saving’, ‘time consuming’, ‘extensive search’, ‘always open’ and then merged into different categories such as ‘Time saving’, ‘Time consuming’, ‘Time indifferent’ and ‘Time unaware’. We then linked these categories to categories such as mobile devices, physical stores or computers. The categories and the relationships between them were related to stages in the decision-making process and to the two target groups, Mothers and Millennials. Based on relevancy and agreement about the themes related to the stages of consumer decision-making, we developed a final version of the analysis.

At home/depth interviews

We recruited participants through advertisement on Facebook and from our network of acquaintances. Multi-channel behaviour was a prerequisite and potential participants were asked about this before being accepted onto the study. Interviews lasted between 40 and 60 minutes and were conducted in the interviewees’ homes to have a natural setting for home decoration. The six interviews were conducted over two weeks during April/May 2016. The interviews were recorded and later transcribed.

In-store interviews

The in-depth interviews were complemented by in-store interviews. Most visitors to the store we used were women aged between 50 and 65 years, who fitted into the group of Mothers. The aim was to collect data about consumer decision-making in another setting. Ideally, we would have re-interviewed the participants we had interviewed at home, but they were not planning to buy home decoration items during the data collection period. Six short interviews (), lasting approximately 15 minutes each, were conducted. The customers were not willing to participate in longer interviews. The interviews were conducted after observing the respondents, and other people, entering the store. The in-store interviews and observations were conducted on April 28th, 2016 in a premium brand home decoration store in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Table 2. In-store interviews.

Observations

We carried out unstructured, disguised observations in the above-mentioned store, which is appropriate in exploratory research. This method is flexible but carries the risk of researcher bias. Natural observations mean that the authors really observed the customer behaviour, which allowed a more accurate understanding. The visitors were not aware that they were being observed and would therefore have behaved more naturally (Malhotra Citation2010). The findings were used to help interpret the interviews.

Results

Need/want recognition

Both groups stated that online and offline channels triggered decision-making and the Internet was the main influence. Popular online triggers were newsletters, preselected fashion sites and social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Mothers over 60 years old that we met in the store were reluctant to use online channels and seemed to spend relatively little time online, mostly carrying out basic activities such as emailing or reading news.

The Millennials were heavy users of smartphones and the smartphone is one of the main tools used at this stage of the decision-making process. Tablets were not the preferred choice of any group, the Mothers preferred computers. One advantage of online channels is the variety of formats such as pictures and videos; the physical store just offers one format. Both groups valued being able to access a retailer online after seeing something they desired in a physical store.

We could sense that Millennials made more spontaneous online visits, triggering their needs, than the Mothers. This probably has to do with the fact that they spend more time online and are more confident navigating between pages.

The Mothers said that they had recently started to do more online. We believe that this trend will increase due to the convenience of the online format and the digitization of many services. The differences between groups were not significant and online channels were an important influence on both groups as they spent a considerable amount of time online, especially the Millennials. Retailers should not underestimate the potential of online channels to attract customers at this stage of the decision-making process. This could be done by paying for placement in online searches or paying bloggers to write about a product, which would enable retailers to target a specific group of consumers. The Millennials were influenced by friends through electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) and social media, which corroborates the findings of Hall and Towers (Citation2017), who stated that other people are an important influence on Millennials’ decision-making, and Viswanathan and Jain (Citation2013), who claimed that Millennials are strongly influenced by social media and reference groups, implying that retailers have little control or influence. The Mothers were mainly influenced by word-of-mouth (WOM).

Formulation of decision problem

This involves the consumer creating mental models, which consists of criteria, alternatives and situational understanding (Karimi Citation2013). These mental models capture the consumer’s understanding of the decision problem and might change when the consumer considers new information in a new context. Examining these mental models is challenging as they are significantly influenced by unconscious and compulsive thinking of which consumers are not aware. Millennials tend to use a slower system of thinking because they operate more online and spend more time thinking. The Mothers spent less time online but admitted more frequent impulsive online behaviour, perhaps as a consequence of their superior financial resources.

Discounting is one of the tactics retailers use to push customers into impulsive behaviour. Both Mothers and Millennials admitted to behaving impulsively after seeing online newsletters, printed leaflets (more often mentioned than thick catalogues) or advertisements on websites. Our findings suggest that the discounting can be successful in both online or offline formats, success relies on pushing the consumer into a quick decision, before he or she starts to think rationally about a potential purchase. We did not detect any group differences in channel preference, but Mothers preferred to use computers for this activity while online whereas the Millennials preferred their smartphones.

Choice of device and channel appeared to be determined by what had been used during the need/want recognition stage as no reasons for switching were mentioned. Some Millennials seemed to skip this stage, making impulsive decisions instead. The Mothers also skipped this stage sometimes, especially when in a physical store, and when they did so they went directly to the purchase stage. Several Mothers stated that fear of goods being sold out was an important driver of impulsive decisions. They said that when faced with a time-limited offer or sale they almost did not consider any alternatives and spent limited time thinking about their decision problem. The Millennials appeared more flexible and did not offer excuses for their impulsive behaviour.

Search and decision-making

Decision-making has three main components; Research, Evaluate and Choose, with Postpone being another alternative stage in the search and decision-making (Karimi Citation2013).

Research and evaluate

Verhoef, Neslin, and Vroomen (Citation2007) introduced the concept Research shopper which involves consumers looking for information and searching via one channel and purchasing via another. The authors of this study were surprised to find that their interviewees perceived the Internet (and thus online retailers) primarily as an information-seeking tool and not a purchasing channel. We observed the same perception of Internet although Verhoef, Neslin, and Vroomen (Citation2007) published their article several years ago, when smartphones, tablets and social media were not widespread.

A difference between the groups is that the Millennials did more extensive online research. They spent a considerable amount of time doing online research, although they originally claimed to use the Internet for attaining time efficiency. Their online searches were more thorough and time-consuming than the corresponding offline searches would be. Consumers who search online carry out a more sophisticated search, but it takes them longer. We found that some of the Mothers did not conduct research before consuming goods and others said they preferred to do their research and decision-making online and then make the purchase in a physical store (webrooming). The main reason for this was that they wanted to feel, touch and see products before making the final purchase decision, as screens do not reproduce the real colours and texture. This is consistent with Blázquez’s (Citation2014) findings, and a similar limitation applies to traditional mail order services, which involve consumers choosing products from a printed catalogue, although colours and features might be reproduced better on the Internet than in printed catalogues. Consumers may have higher expectations of online product exposure.

The Mothers were aware of the Internet’s functionality and advantages but some did not want to conduct online research themselves, at least not for home decoration products, and they justified this in various ways. Some complained that online research resulted in information overload, which produced confusion rather than clarity. Flavián, Gurrea, and Orús (Citation2016) stated that consumers who use both online and offline channels experience an improved search and decision-making, which implies that multi-channel consumers should feel more confident in their decision-making than single-channel researchers, but this is not something we investigated in this study. Flavián, Gurrea, and Orús (Citation2016) argued that the aim of webrooming is to have confidence when making a purchase and our findings confirm that this is indeed the case. The Mothers were more inclined to webroom than the Millennials.

All interviewees argued strongly for the advantages of online research and most of them talked positively about being able to open windows for several different retailers simultaneously and thus getting a holistic overview of the offerings; the Mothers did this for some goods, although not for home decoration goods. The Mothers mainly used computers rather than smartphones or tablets for this stage due to the larger screen and ease of navigation, despite the fact that most mobile devices have touchscreen functionality. One can question whether it is necessary or advantageous to compare products and prices during the decision-making process for hedonistic consumption, where the main objective is not to purchase the most rationally suitable product, but to fulfil affective and emotional needs or desires. Consumers probably want to feel that they are behaving as informed, rational customers so they believe they are behaving rationally, even when their decision-making is based on hedonistic factors. Consumers feel more powerful after doing thorough research due to their increased knowledge (Foucault Citation1972).

One Mother pointed out one advantage of doing research online is that an online store is never closed. One can see the full range of colours and sizes online, which is not possible in a physical store due to limitations on supply. The consumers can thus experience a greater control of the total supply online compared to offline. This contradicts all the statements made by other interviewees about wanting to feel and touch products. The same Mother stated that she appreciates being able to do her research and shopping in late evening, when home decoration stores in Sweden are closed. The option to do research and shopping online at a time convenient to the individual may become more widely appreciated in the future as our society is becoming more individualistic.

Online window-shopping will improve as technological advances make new functionality possible. Shopping and window-shopping in a physical store could be perceived as a social activity and this was something noted by both groups. Retailers add functionality and features to enable social online shopping because Millennials, who are ‘digital natives’, will probably be more easily persuaded to shop online than the Mothers in our sample. Millennials already conduct social activities online through social platforms. That shopping can be perceived as a social event or form of entertainment may indicate that retail marketing directed towards Millennials should be experience-based.

The Millennials conducted their research with their smartphones, but most purchases were made via computer. This is in line with the findings of de Haan et al. (Citation2015) who stated that mobile devices increase traffic but also have lower conversion rates than fixed devices. The various devices complement each other but could be improved by the addition of smart software that ensures that consumers leave a digital footprint.

The Millennials were more positive about using smartphones or tablets during this stage, a consequence of their more frequent use of mobile devices, including during previous decision-making stages. One Mother stated that her poor eyesight made the smartphone, with its small screen, unsuitable for research and evaluation.

Rapp et al. (Citation2015) stated that consumers have started to use mobile devices in physical stores to compare offers and search for more information. We did not observe this, nor was such behaviour mentioned during interviews. This might be because home decoration goods is a category for which comparison of products from a mobile device while in a physical store is not widespread due to the characteristics of hedonic consumption.

There are physical stores which provide tablets to facilitate in-store decision-making and ordering. Christine, 49 years, stated explicitly that she would not place any orders with in-store technology. She wanted to use her own devices for reasons of security, integrity and ease of use. This is an indication that experienced online users neglect in-store technology. Less experienced online users might appreciate the availability of help from staff when ordering through in-store technology.

Webrooming is increasing, but there is still a lack of research on the topic although it is the most common cross-channel shopping behaviour. Our findings are consistent with research that there are more webroomers than showroomers and the number is increasing (Flavián, Gurrea, and Orús Citation2016).

The Mothers tended to use a smaller number of retailers probably because they were late adopters of Internet technology, and therefore not as adventurous and courageous online as the Millennials.

Whether research and evaluation was carried out on the same device as the preceding stage depended on the context. Interviewees did not mention any particular reason for switching devices when being online while an information seeking could continue online after seeing a good in a physical store.

Our findings suggest that, when it occurs, the ‘Research and Evaluate’ stage of Karimi’s model is prolonged, with both groups – particularly the Millennials – performing extensive research. This stage is mainly carried out online, regardless of the channel used in preceding stages. This implies that retailers should put resources into ensuring that their websites provide the information for which potential customers are searching. The Mothers preferred to buy goods in physical stores and when they do this, the research and evaluate stage does not take place. Retailers could consider treating their web stores mainly as promotional channels and sources of information to complement the physical stores and facilitate webrooming.

The Millennials perceived online stores as both information-seeking and purchasing channels, provided the payment appeared secure. New channels and platforms will emerge and it is important for retailers to try to understand the implications for consumers’ decision-making as understanding consumers’ perceptions of the new channels and platforms will provide competitive advantage.

Choose

It is difficult for online consumers to visualise a home decoration item and assess how it will fit in the home. Our interviewees had not used software apps from IKEA and other retailers but use may become more widespread as the digitization of society continues. One reason given for not downloading retailers’ apps was lack of storage capacity, which is consistent with Shankar et al. (Citation2016) who noted that the competition for downloading a retailer app is fierce.

Cornelia, 55 years, elaborates about the potential cost of returning goods (postage):

“The fact of potential return costs makes me avoid buying things online. I prefer to buy goods in Malmö, where I work, since I am sure I will be able to return the goods without paying any charges. I therefore also prefer to make spontaneous purchases in physical stores, because I know it would not be a big deal to return products.”

Both groups perceived the potential cost of returning goods as an obstacle to choosing an online retailer, but the Mothers seemed more reluctant to pay the costs and undertake the extra work, perhaps because the Millennials are growing up in a richer society and have more spare time.

Interesting to notice is the inclination of online spontaneous purchases where we are able to notice a tendency of the interviewees to prefer conducting spontaneous and impulsive purchases in physical stores. This is probably linked to the immediate gratification and satisfaction of receiving the product immediately. This also reduces the likelihood that future consumers will prefer showrooms to ordinary physical stores. Nicholson, Clarke, and Blakemore (Citation2001) claimed that Internet shopping (and therefore, we would argue, online decision-making) is linked to social and functional factors whereas shopping at physical stores is more strongly linked to hedonistic and social motives.

Cornelia, 55 years, stated that she does not like to leave a physical store without a purchase. This was also her reason for making most of her purchases offline. Online purchasing requires patience, retailers could try to compensate for lag between making the purchase and receiving the goods by offering lower prices online or they could guarantee fast delivery.

This stage was closely linked to the preceding stage and we could not detect any switching of devices before or during the Choose stage. Some interviewees stated that they chose a physical store to make the purchase, which implies that the physical and online channels are used in complementary fashion. The Choose stage may be skipped if a purchase is postponed, which leads us to the next stage.

Postpone

A disadvantage for retailers is the consumer’s ability to interrupt the decision-making process, postpone a decision or purchase and leave the retailer before a purchase has been made. Retailers do not want to be used solely as research channels and cede the position of purchase channel to competitors.

Some of the Millennials stated that many potential online purchases were not merely postponed but actually aborted, due to the characteristics of the online experience. A purchase seemed to be less of an obligation in the online environment. Anna, 20 years, said that termination of purchases happened to her occasionally. She told us that she usually watches TV while making purchases online (mainly via her computer) and sometimes is suddenly distracted and then decides not to purchase the item she had been considering. This implies that retailers could try to trigger purchasing through time-limited or tempting offers that discourage consumers from postponing purchases.

Postponing occurs both online and offline, but we found that when online the Millennials postponed more often than the Mothers, probably due to their heavy use of the Internet. The Millennials were more or less constantly connected and Anna, 20 years, who was a major shopper, seemed to be constantly involved in multiple purchase decisions. The Millennials were younger and had more spare time than the Mothers, which enabled them to spend more time on decision-making. They also had fewer financial resources, so purchases were more of a financial burden for them.

Physical stores have the advantage, for the customer, of immediate gratification and most Swedish retailers have generous rules which allow consumers to return a purchase for a complete refund, provided that they do so within seven days. In effect this means that the customer can postpone the final decision beyond the actual purchase. Returning goods may be perceived as time consuming and this might occasionally deter customers from returning purchases, but having the option of a free, easy-to-use return process may make customers more inclined to make rather than postpone a purchase.

Consumers may feel more relaxed and anonymous when doing research online, without pressure from store personnel to make a decision or purchase. Postponing is easy online, which is not only positive for the retailer as the consumer can choose another competing retailer after contemplation or just terminate the purchase. We argue that retailers must offer a smooth, user-friendly, rapid purchase to discourage consumers from aborting a potential purchase or switching to another retailer. Retailers could also treat online stores as promotional channels rather than sales channels.

Our findings indicate that the most interrupted purchases occurred when mobile devices were being used, especially smartphones, because Millennials frequently window-shopped. The Mothers did not postpone or interrupt their purchases as often, and not when they were in a physical store. Mothers who went from an online search to a physical store were not postponing the purchase, but they did interrupt the decision-making and purchase process because of a reluctance to make purchases online.

Appraise

This stage was included in Karimi’s (Citation2013) online decision-making model, although Karimi argued that it has been overlooked by researchers. This is a stage where consumers experience control due to the attained insights about their decision-making by reviewing the process and alternatives (Karimi Citation2013). This stage is interrelated to the formulation stage described above as it is a stage in which customers feel in control of the decision-making. Evaluation of alternatives could be perceived as an endless process, given the enormous supply of retailers, not only domestically but also globally.

Anna, 20 years, spent a lot of time online and stood out because she invested a lot of time in appraisal. She reviewed her decisions constantly and looking for the right home decoration item seemed to be an online hobby for her.

Of the Mothers group only Annika, 46 years, claimed occasionally to review the process online. Her effective usage of online channels may be related to her job, which involved using new technologies.

Compared with the Mothers, the Millennials spent more time using online channels in the search and decision-making stage and they seemed to transfer the same behaviour into the Appraisal stage with reviewing the process. We found that using online channels prolonged the appraisal stage due to new channels and devices such as comparison websites and smartphones. Using online formats and connected devices comes more easily to Millennials, and our Millennials tended to spend more time on the appraisal stage than the Mothers. They saw no reason to switch devices for this activity.

As already noted, today’s consumers tend to have more information advantages over retailers than in the past (The informed customer Citation2014), and they might be disappointed with retailers who offer limited amounts of channels. This goes for appraisal just as for the search and decision-making process and we argue that the appraisal stage is assuming more importance amongst consumers to the opportunities created by the availability of multi-channels.

Purchase

Karimi (Citation2013) claimed that ‘choosing the products’ and ‘performing the purchase task’ should be separated when considering online purchases as a stage could include offline channels as well. Goworeck and McGoldrick (Citation2015) listed the decisions required during the purchase process: (1) whether to purchase, (2) when to purchase, (3) where and (4) which payment method to use.

Lemon and Verhoef (Citation2016) stated that consumers prefer to use mobile channels for searching rather than purchasing and we were able to confirm this. We believe that attitudes to mobile channels will improve as digitisation continues and consumers become more used to mobile channels. We also expect technological improvements.

Anna, 20 years, was continually making and re-evaluating purchase decisions, which sometimes meant that in the end she did not buy a product she had at one point intended to purchase. This occurred because she used several devices and channels simultaneously and was frequently distracted. Online stores risk losing customers if they require customers to go through a long registration process or use complicated or insecure payment methods. Even Anna, at 20 years our youngest interviewee, expressed concerns about making online purchases and payments with a smartphone, as she did not consider this secure, although she was happy to use her computer for online purchases. We were surprised by this resistance and the main reason for it is that webpages are not optimised for smartphones, according to many of our interviewees, and so people perceive that something could go wrong, for example they might end up ordering the wrong product. One strategy retailers could adopt is to direct online visitors to a physical store to make their purchase. Another strategy would be to offer secure online payment, to increase consumers’ confidence. Ordering habitual products with a mobile device increases the order rate and size Shankar et al. (Citation2016). We were not able to confirm this, but Anna, 20 years, described shopping habits for FMCG that were in line with Shankar et al.’s (Citation2016) findings.

Pantano and Timmermans (Citation2014) stated that the mobile channel is becoming the new mainstream shopping channel, but our findings contradict this assertion. Consumers seem unwilling to take big risks when buying home decoration items because they are intended to last for a long time and involve more financial investment than FMCG. Anna, 20 years, was willing to take risks when ordering FMCG such as groceries. Some Millennials stated that conducting purchases of less expensive products is perceived as suitable since standardised, low involvements products are associated with lower risks of failures and therefore easier to purchase online.

Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman (Citation2015) stated that experienced online shoppers tend to become less loyal to retailers. Anna, 20 years, said she preferred to buy from web stores she knew or that her friends recommended. Our findings indicate that even experienced online shoppers, as many Millennials are, tended to rely on a few secure online stores and that trust in the security of payment systems was a major issue for both our groups.

The Millennials did not find switching devices for this stage inconvenient or disadvantageous, but such switching may have negative consequences for the retailer if it results in a purchase being postponed, aborted or made at a competitor’s store. Millennials were more likely to switch device during this stage than Mothers. The Millennials were more willing than the Mothers to make purchases online. The Mothers preferred to make purchases offline.

The main reasons given for not making a purchase online were concerns about payment security, shipping costs, return costs and concern that there would be problems when returning goods. Retailers could easily minimise these obstacles. Arora and Sahney (Citation2017) stated that consumers make their purchases offline due to ‘poor product diagnosticity’ online and this could be addressed by offering three-dimensional images of products or product videos. Our findings also indicate that poor product exposure was a concern, but not one of the main reasons for avoiding online purchasing. Flavian et al. (Citation2016) encouraged retailers to drive traffic from online channels to physical stores in order to increase the number of actual purchases.

No interviewee made any spontaneous statement about using in-store technology for conducting purchases. Use of in-store technology to order products is not, yet, widespread in Sweden.

Cornelia, 51 years, said that online she was a sophisticated, rational buyer whereas offline she was a rather impulsive and irrational buyer. She said that a disadvantage of being a sophisticated buyer was that it was more time consuming and sometimes more problematic.

Post-purchase

After consumers finish their purchase they might continue to what has been described as the post-purchase stage. Post-purchase behaviour may include eventual repurchasing and involvement in WOM and e-WOM feedback about the product or service purchased. WOM and e-WOM influence other consumers and the retailer has little control unless it pays for positive feedback, for example, by paying bloggers. Our data suggest that not every consumption decision will generate feedback. It is interesting to note that consumers tend to provide negative feedback more frequently than positive feedback.

There were differences between the groups. The Millennials tended to leave comments online, whereas the Mothers, especially those interviewed in the premium brand store, were more likely to be involved in offline WOM, although some stated that they did not talk to other people about their purchases. Thus, the Mothers in our sample have limited reach and little influence on future consumers. The Millennials had no device preferences when it came to leaving online comments. Most interviewees switched device for this activity due to the passage of time between making the purchase and commenting on it.

Comparison of consumers’ perceptions of multi- and omni-channel retailing

Picot-Coupey, Huré, and Piveteau (Citation2016) stated that there is a lack of academic consensus on definitions of multi- cross- and omni-channel retailing. One description of omni-channel retailing is that it entails channel integration so that the consumer experience is seamless, whereas in multi-channel retailing the channels are separate and non-overlapping (Verhoef, Kannan, and Inman Citation2015). Piotrowicz and Cuthbertson (Citation2014) described omni-channel retailing as an evolution of multi-channel retailing in which the customers have the same brand experience in every channel. They also describe multi-channel retailing as involving channels that are separate from one another, whereas in omni-channel retailing the customer moves between online and offline stores within a single transaction process. Ailwadi and Farris (Citation2017) emphasised that omni-channel retailing involves not only the use of multiple, integrated channels to support consumer research and purchasing but also the use of multiple channels (owned, paid and earned) to connect with consumers. Mosquera, Olarte Pascual, and Juaneda Ayensa (Citation2017) described omni-channel retailing from the retailer’s perspective, noting that it meant sharing inventory and customer information across channels and having a homogeneous pricing policy. Cross-channel retailing can be defined as partial integration of channels (Mosquera, Olarte Pascual, and Juaneda Ayensa Citation2017). We believe that retailers who wish to remain competitive will need to move toward omni-channel retailing.

Cornelia, 55 years, expressed disappointment with retailers such as H&M due to their shipping costs.

“I do not understand why stores like Boozt deliver without shipping costs but chains like H&M have shipping costs. . There are many H&M stores all over the cities so why am I not able to return things I bought online to their physical stores? I only buy things from H&M online if they are ‘online only’.”

Cornelia, 55 years, seemed to expect an omni-channel experience and was disappointed with the service offered by the retailer she criticised in the above quotation. Clearly she does not perceive H&M’s various channels as separate, although many retailers do treat their various channels as separate silos (Piotrowicz and Cuthbertson Citation2014) for accounting purposes, which, we believe, has a negative impact on the brand.

Cornelia, 55 years, spoke about the impact shipping costs had on her purchasing decisions:

“I found a pink bedspread at IKEA.se. I think it cost only SEK 59. The shipping cost was pretty high (SEK 39 I believe) compared with the price. I did not feel I could purchase the bedspread online because it felt like a bad deal, even though the total cost was very low. I would gladly pay SEK 100 for it online with another retailer if the shipping costs were included. I have still not bought a new bedspread… I might wait until the next time I’m passing an IKEA or until I see a nice bedspread somewhere else…”

All interviewees expressed concerns about shipping costs and felt it was important to avoid them, which can usually be done by ordering goods totalling above a certain value. Retailers could treat online channels as promotional vehicles instead of as independent profitable channels, as previously mentioned. Omni-channel offerings include click and collect (order online and collect in store) and the facility to order in-store for home delivery.

Emma, 24 years, told us that she found online stores more similar to one another than the different channels of a given brand:

“I think that online shops are very impersonal. I think that Jysk online is almost the same as IKEA online. There is a big difference between the physical stores when you visit them, but online they are all boring and soulless.”

This perception might reflect technological limitations on displaying products online, the online payment process, etc. Retailers need to make sure the brand experience is similar throughout the different channels.

Conclusions

Multi-channels influence today’s consumer decision-making for SMCG. Home decoration is a product category where customer adoption of multi-channel retailing has been late, and the decision-making process is different, we would argue, from that for FMCG. The characteristics of home decoration goods – durability, high involvement and slow-moving – make online-only decision-making less likely. Consumers use several complementary channels and devices and, if the retailer has tailored the service appropriately, this should strengthen the brand and improve the customer experience. We expect a further shift towards more online-only decisions and purchasing and this is something to which retailers will need to adapt. One major challenge for retailers is to retain potential customers at each of the different touchpoints. New technologies, such as traceable customer footprint software, will enable this.

The Mothers reported a shorter, more linear decision-making process than the Millennials, apparently because they wanted to spend less time on decision-making. Millennials have grown up in an online environment, they are used to the options and functions of the Internet and seem to have a slightly different decision-making process from older generations. The Millennials relied mainly on online channels during their decision-making, and we expect that technological improvements will soon eliminate the obstacles and disadvantages to conducting all stages of the decision-making and purchase process online. Retailers need to prepare for a context in which omni-channelling is mainstream. Embracing omni-channelling will be a key success factor in the future.

Theoretical contributions

Lemon and Verhoef (Citation2016) asked whether mobile devices are new channels or just devices that replace the desktop computer. Our findings suggest the latter. The Millennials seemed willing to replace their desktop computer with a smartphone when technology and security allow. They were heavy users of smartphones, which they used for need/want recognition and for searching and decision-making, but not to make purchases. This corroborates Lemon and Verhoef’s (Citation2016) finding that customers consider mobile channels suitable tools for the search stage but not the purchase stage. The smartphone was also used for post-purchase activities such as e-WOM, but both groups were reluctant to use smartphones to make purchases due to concerns about security. Tablets were used in preference to smartphones but were still used less than computers. The Mothers preferred buying goods in a physical store.

Being constantly connected is a lifestyle for the Millennials and we expect their extensive pre-purchase research to persist in later life, when they will have greater purchasing power and be the main target for many retailers. Our findings show that the ‘Research and Evaluate’ stage of Karimi’s (Citation2013) model is prolonged, if executed at all, as both groups in our study carried out extensive searches. This implies that retailers should ensure that their websites can supply the information for which potential customers in both groups are searching. The main reason given for doing research online was that it was more time efficient than other methods, which conflicts somewhat with the fact that both groups, but particularly the Millennials, spend a lot of time doing online research. The mobile channels can be viewed as disruptive elements of traditional search and decision-making activities (Rigby Citation2011) and our data supports this view. Verhoef, Neslin, and Vroomen (Citation2007) introduced the concept of the ‘research shopper’, someone who searches for information using one channel but purchases through a different channel. This behaviour was still common among both our groups. Our interviewees clearly preferred webrooming over showrooming. Their main reason for wanting to make purchases offline was that they wanted to see and touch the product in real life. Many interviewees stated they wanted immediate gratification, and in this case the delivery time puts online retailers at a disadvantage.

Mainly Millennials used mobile channels for the appraisal stage. To constantly review the process within multi-channels seemed natural for them. The Mothers preferred to skip this stage. Other people are a major influence on Millennials’ decision-making, which implies that in relative terms retailers lack control and influence.

Practical contributions

This study has revealed consumer resistance to online shipping costs and return costs (postage), although this was not the main topic for this study. Retailers should take efforts to tackle this obstacle if they wish to encourage online purchasing. Customers need an incentive to remain loyal to a retailer throughout the decision-making process.

There are retailers who treat their multi-channels as separate instead of embracing omni-channelling. We had interviewees who did not understand this approach; they felt that they were interacting with a single brand, regardless of the channel. Retailers need to be aware of this and adapt to consumers’ expectations.

Spontaneous purchasing was less frequent online. Retailers could try to prompt consumers to make purchases online by offering discounts or ‘online only’ products.

Retailers could also consider treating their web stores as mainly promotional and informational channels that complement their physical stores. We believe that the digitisation of society and changes in Western societies’ city planning will increase online decision-making and sales, so we do not recommend this as a long-term strategy as offline purchases will probably decrease in the future.

Both groups stated that retailers’ websites were not optimised for smartphones and gave this as their main reason for using computers rather than smartphones to make online purchases. We did not investigate the truth of this perception, but retailers should be concerned if they have optimised their websites but consumers remain unaware of this. The Millennials were aware of the existence of apps, but considered them unattractive because of the amount of smartphone storage capacity they take up.

Post-purchase behaviour is relevant in a multi-channel environment. The Millennials tended to use online channels to communicate their negative experiences whereas the Mothers used offline WOM. The reach of e-WOM is wider and retailers need to have strategies to meet this challenge. Both groups were reluctant to return goods, which is another form of post-purchase behaviour.

We have findings of consumers perceiving online channels with different retailers, similar to each other, called prototypical website design (Emrich and Verhoef Citation2015). We believe that e-commerce will evolve and online stores become more heterogeneous, with successful retailers seeking to distinguish their online presence from that of competitors to achieve brand synergies and competitive advantage.

Future research

As noted above, most of today’s multi-channel retailers use prototypical, channel-specific website designs instead of having a website design that correlates with the physical store to create a homogenous brand experience. We urge researchers to compare the effects of generic and brand-specific website designs on sales and brand image. Another interesting topic for future research is the current dearth of omni-channel retail offers. What are the negative effects of neglecting omni-channel retailing and what are the positive effects of embracing such an approach? Another issue is what the consumer decision-making process looks like in an omni-channel context. A quantification of this study is also recommended. Lemon and Verhoef (Citation2016) argued that studies about concepts such as choice overload, purchase confidence and decision satisfaction would be worthwhile because they influence the behaviour of consumers, who can choose to interrupt a search or postpone a purchase. They also recommended that firms should identify the triggers that determine whether a customer continues or interrupts the purchasing process and we suggest that this is also a question for academic researchers to address – what are the critical touch points during the decision-making process?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- “The Informed Customer”. 2014. Lund Business Review 21–24. http://www.lusem.lu.se/media/ehl/presentationsmaterial/lund-business-review-2014-en.pdf.

- Ailawadi, K., and P. Farris. 2017. “Managing Multi- and Omni-Channel Distribution: Metrics and Research Directions.” Journal of Retailing 93 (1): 120–135. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2016.12.003.

- Arora, S., and S. Sahney. 2017. “Webrooming Behaviour: A Conceptual Framework.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 45 (7/8): 762–781. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-09-2016-0158.

- Ashman, R., M. R. Solomon, and J. Wolny. 2015. “An Old Model For A New Age: Consumer Decision Making In Participatory Digital Culture.” Journal of Customer Behaviour 14 (2): 127–146. doi:10.1362/147539215x14373846805743.

- Blackwell, R. D., P. W. Miniard, and J. F. Engel. 2006. Consumer Behavior. 10th ed. Mason: South-Western.

- Blázquez, M. 2014. “Fashion Shopping In Multichannel Retail: The Role Of Technology In Enhancing The Customer Experience.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 18 (4): 97–116. doi:10.2753/jec1086-4415180404.

- Bryman, A., and E. Bell. 2015. Business Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brynjolfsson, E., Y. J. Hu, and M. S. Rahman. 2013. “Competing In The Age Of Omnichannel Retailing.” MIT Sloan Management Review 54 (4): 23–29. http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/competing-in-the-age-of-omnichannel-retailing/.

- Campo, K., and E. Breugelmans. 2015. “Buying Groceries In Brick And Click Stores: Category Allocation Decisions And The Moderating Effect Of Online Buying Experience.” Journal Of Interactive Marketing 31: 63–78. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2015.04.001.

- Chu, J., M. Arce-Urriza, -J.-J. Cebollada-Calvo, and P. K. Chintagunta. 2010. “An Empirical Analysis Of Shopping Behavior Across Online And Offline Channels For Grocery Products: The Moderating Effects Of Household And Product Characteristics.” Journal Of Interactive Marketing 24 (4): 251–268. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2010.07.004.

- de Haan, E., P. K. Kannan, P. C. Verhoef, and T. Wiesel. 2015. “The Role of Mobile Devices in the Online Customer Journey”, Marketing Science Institute, Working Paper Series 2015. Report No.15-124. Accessed 26 October 2017. http://www.msi.org/reports/the-role-of-mobile-devices-in-the-online-customer-journey/

- E-Barometern. 2016. http://www.postnord.se/sv/foretag/foretagslosningar/e-handel/e-handelsrapporter-och-kundcase/Sidor/e-barometern.aspx.

- Ecommercenews. 2015. https://ecommercenews.eu/

- Emrich, O., and P. C. Verhoef. 2015. “The Impact Of A Homogenous Versus A Prototypical Web Design On Online Retail Patronage For Multichannel Providers.” International Journal Of Research In Marketing 32 (4): 363–374. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2015.04.002.

- Engel, J. F., R. D. Blackwell, and D. T. Kollat. 1978. Consumer Behavior. Hinsdale, Ill: Dryden Press.

- Flavián, C., R. Gurrea, and C. Orús. 2016. “Choice Confidence in the Webrooming Purchase Process: The Impact of Online Positive Reviews and the Motivation to Touch.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 15: 459–476. doi:10.1002/cb.1585.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge. London: Tavistock Publictions.

- Goworek, H., and P. J. McGoldrick. 2015. Retail Marketing Management. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

- Hall, A., and N. Towers. 2017. “Understanding How Millennial Shoppers Decide What to Buy: Digitally Connected Unseen Journeys.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 45: 498–517. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-11-2016-0206.

- Hamiln, R. P., and T. Wilson. 2004. “The Impact Of Cause Branding On Consumer Reactions To Products: Does Product/Cause ‘Fit’ Really Matter?” Journal Of Marketing Management 20 (7–8): 663–681. doi:10.1362/0267257041838746.

- Kahneman, D., P. Slovic, and A. Tversky. 1982. Judgment Under Uncertainty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kalnikaitė, V., J. Bird, and Y. Rogers. 2012. “Decision-Making In The Aisles: Informing, Overwhelming Or Nudging Supermarket Shoppers?” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 17 (6): 1247–1259. doi:10.1007/s00779-012-0589-z.

- Kannan, P. K., W. Reinartz, and P. C. Verhoef. 2016. “The Path to Purchase and Attribution Modeling. Introduction to Special Section.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 33 (3): 449–456. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.07.001.

- Karakas, F., A. Manisaligil, and E. Sarigollu. 2015. “Management Learning at the Speed of Life: Designing Reflective, Creative, and Collaborative Spaces for Millennials.” The International Journal Of Management Education 13 (3):,): 237–248. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2015.07.001.

- Karimi, S. 2013. “A Purchase Decision-Making Model Of Online Consumers And Its Influential Factors Across Sector Analysis” (PhD diss.), University of Manchester.

- Lemon, K. N., and P. C. Verhoef. 2016. “Understanding Customer Experience Throughout the Customer Journey.” Journal of Marketing 80 (6): 69–96. doi:10.1509/jm.15.0420.

- Lewis, J., P. Whysall, and C. Foster. 2014. “Drivers And Technology-Related Obstacles In Moving To Multichannel Retailing.” International Journal Of Electronic Commerce 18 (4): 43–68. doi:10.2753/jec1086-4415180402.

- Malhotra, N. K. 2010. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation. 6th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Mosquera, A., C. Olarte Pascual, and E. Juaneda Ayensa. 2017. “Understanding the Customer Experience in the Age of Omni-Channel Shopping.” Icono 14–15 (2): 166–185. doi:10.7195/ri14.v15i2.1070.

- Neslin, S. A., D. Grewal, R. Leghorn, V. Shankar, M. L. Teerling, J. S. Thomas, and P. C. Verhoef. 2006. “Challenges And Opportunities In Multichannel Customer Management.” Journal of Service Research 9 (2): 95–112. doi:10.1177/1094670506293559.

- Nicholson, M., I. Clarke, and M. Blakemore. 2001. “One Brand, Three Ways To Shop: Situational Variables And Multichannel Consumer Behaviour.” International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 12 (2): 131–148. doi:10.1080/09593960210127691.

- Nordfalt, J. 2005. “Is Consumer Decision-Making Out Of Control?” (PhD diss.), Stockholm School of Economics.

- Pantano, E., and H. Timmermans. 2014. “What Is Smart For Retailing?” Procedia Environmental Sciences 22: 101–107. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2014.11.010.

- Pantano, E., and M. Viassone. 2014. “Demand Pull And Technology Push Perspective In Technology-Based Innovations For The Points Of Sale: The Retailers Evaluation.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21 (1): 43–47. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.06.007.

- Parment, A. 2013. “Generation Y Vs. Baby Boomers: Shopping Behaviour, Buyer Involvement and Implications for Retailing.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 20 (2): 189–199. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-10-2015-0169.

- Picot-Coupey, K., E. Huré, and L. Piveteau. 2016. “Channel Design to Enrich Customers’ Shopping Experiences: Synchronizing Clicks with Bricks in an Omni-Channel Perspective – The Direct Optic Case.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 44 (3): 336–368. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-04-2015-0056.

- Piotrowicz, W., and R. Cuthbertson. 2014. “Introduction To The Special Issue Information Technology In Retail: Toward Omnichannel Retailing.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 18 (4): 5–16. doi:10.2753/jec1086-4415180400.

- Rapp, A., T. L. Baker, D. G. Bachrach, J. Ogilvie, and L. S. Beitelspacher. 2015. “Perceived Customer Showrooming Behavior And The Effect On Retail Salesperson Self-Efficacy And Performance.” Journal of Retailing 91 (2): 358–369. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2014.12.007.

- Rigby, D. 2011. “The Future Of Shopping.” Harvard Business Review 89: 65–76.

- Shankar, V., M. Kleijnen, S. Ramanathan, R. Rizley, S. Holland, and S. Morrissey. 2016. “Mobile Shopper Marketing: Key Issues, Current Insights, and Future Research Avenues.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 34: 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2016.03.002.

- Tyc, D. 2013. “The Drivers To Successful Marketing For Omni Or Multi-Channel Retailers.” New Zealand Apparel 46 (2): 12–13.

- Verhoef, P. C., P. K. Kannan, and J. J. Inman. 2015. “From Multi-Channel Retailing To Omni-Channel Retailing.” Journal of Retailing 91 (2): 174–181. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2015.02.005.

- Verhoef, P. C., S. A. Neslin, and B. Vroomen. 2007. “Multichannel Customer Management: Understanding The Research-Shopper Phenomenon.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 24 (2): 129–148. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.11.002.

- Viswanathan, V., and V. Jain. 2013. “A “Dual-System Approach to Understanding “Generation Y” Decision Making.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 30 (6): 484–490. doi:10.1108/JCM-07-2013-0649.

- Wolny, J., and N. Charoensuksai. 2014. “Mapping Customer Journeys In Multichannel Decision-Making.” Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice 15 (4): 317–326. doi:10.1057/dddmp.2014.24.

- Xu, J., C. Forman, J. B. Kim, and K. Van Ittersum. 2014. “News Media Channels: Complements Or Substitutes? Evidence From Mobile Phone Usage.” Journal of Marketing 78 (4): 97–112. doi:10.1509/jm.13.0198.

- Yan, R. 2008. “Pricing Strategy For Companies With Mixed Online And Traditional Retailing Distribution Markets.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 17 (1): 48–56. doi:10.1108/10610420810856512.

- Zhang, J., P. W. Farris, J. W. Irvin, T. Kushwaha, T. J. Steenburgh, and B. A. Weitz. 2010. “Crafting Integrated Multichannel Retailing Strategies.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 24 (2): 168–180. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2010.02.002.