Abstract

Purpose

Many children with autism spectrum disorder do not have symbolic play skills. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of a training procedure on the acquisition, maintenance, and generalization of object-substitution symbolic play in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Methods

A single-case experimental design (multiple-probe across four behaviors) was used. One girl (5 years) and two boys (4–5 years) participated in this study. The training procedure involved withdrawing necessary items in play activities, supplying multiple substitutes, and providing hierarchical assistive prompts. Each child’s symbolic play responses across baseline, intervention, and follow-up conditions were recorded and graphed. Data analysis involved visual inspection of graphs.

Results

The results indicated that the procedure effectively increased and maintained object-substitution symbolic play. Generalization to untaught play activities occurred in all children, and symbolic play increased in the free play setting for one child.

Conclusions

Arranging play activities with missing items increased opportunities for children to engage in symbolic play. The training procedure can be used in clinical and educational settings as an initial step to establish and improve complex play behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder who lack such skills.

Many children with autism spectrum disorder have inappropriate play behaviors and do not demonstrate symbolic play.

Arranging play activities with missing items and systematic assistive prompts effectively increased object-substitution symbolic play.

Generalization of symbolic play to untrained play activities occurred after the intervention.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Play is important to children’s learning and development. Children learn through play by interacting with the materials and people involved in their play activities. Symbolic play is one important developmental milestone achieved around 2 years of age in typically developing children [Citation1] and is highly correlated with children’s language, social, and emotional development in late childhood [Citation1–3]. Symbolic play refers to children’s play activities that are not consistent with reality, including object substitutions (e.g., pretending a hat is a cup), attributions of pretend properties (e.g., pretending a doll is sleepy), and imaginary objects (e.g., pantomime) [Citation4–6]. Unfortunately, symbolic play is rarely observed in play activities by children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; [Citation7]) who suffer from difficulties in social communication, restricted interests or behavioral patterns. Teaching symbolic play to children with ASD is important because such play activities provide opportunities for learning various types of skills, engaging in social interactions with others, and developing a community of interest for leisure [Citation4,Citation5]. Symbolic play is recommended as one of the foundational skills in early intervention [Citation8,Citation9]. However, interventions aimed at specific symbolic play skills remain limited. Each type of symbolic play behavior is complex and involves different behavioral processes, and therefore, it is necessary to analyze the processes and develop intervention strategies accordingly.

Lee et al. [Citation10] attempted to analyze the behavioral processes in object-substitution symbolic play based on children’s acquisition of naming suggested by Horne and Lowe [Citation11] and developed a training procedure to increase object-substitution symbolic play. For example, in a caregiver-child interaction during bath time, the caregiver takes a bowl and says, “This is a boat.” Based on the new name given to the bowl (bowl = boat), the child moves the bowl on water in the bathtub (The play action of a boat is applied to a bowl). Using this paradigm, Lee et al.’s [Citation10] procedure involved presenting a common object, asking the child what else this object could possibly be (e.g., “What can you pretend with this?”), and requiring the child to perform the substitute’s play action using the common object. The name of the substitute was first prompted with a picture and then an echoic prompt plus an instructor modeled play action, if necessary. The results of their study indicated that children with ASD were able to generate multiple creative uses for each common object after training. However, the procedure requires conversational speech and may not be applicable to children who have limited or weak verbal expressions in their repertoire. Object substitutions observed in typically developing children’s play activities do not always involve intraverbal responses. Therefore, children who have receptive responses (e.g., selecting an object upon hearing its name or its conventional use) with limited verbal expressions can potentially acquire object-substitution symbolic play.

Other teaching methods to increase symbolic play in young children with ASD included video modeling, systematic prompts, and naturalistic teaching. Video modeling effectively increases imitative play behavior but generalization has to be programmed using matrix training [Citation12,Citation13] or multiple exemplars [Citation14]. Naturalistic teaching emphasizes following the child’s lead while incorporating assistive prompts or modeling in play settings [Citation15–17] or a combination of discrete trials and naturalistic teaching [Citation18,Citation19]. Although naturalistic strategies are reported to promote generalization of acquired skills compared to video modeling [Citation16], such interventions usually cover overall pretend play behaviors with limited descriptions of specific procedures and target behaviors, making it difficult for consistent implementation across instructors and settings. As discussed, the complexity involved in each type of symbolic play requires an operational analysis for the development of effective interventions. Such a behavior-analytic approach will not only establish complex play repertoires for the children in question but also provide clear-cut steps for reliable replications. In addition to this, naturalistic teaching requires the implementer to recognize and utilize naturally occurring events to increase the target behavior, which may not provide sufficient learning opportunities for children with ASD to acquire complex play skills. It is necessary to arrange the presentation of play activities to increase the likelihood for the target play behavior to occur.

Parsonson and Baer [Citation20] arranged the tasks with missing tools to teach preschool children creative problem solving in the form of improvisation. Improvisation was defined as performing a given task effectively by using a substitute to replace a missing part necessary for task completion. The researchers assigned tasks but did not provide one of the specific tools with a designated purpose for the tasks (e.g., a hammer was not provided for pounding down wooden pegs). Instead, they provided multiple alternate materials (e.g., a piece of brick) to evoke creative uses of these available materials for task completion. All five children increased the diversity of improvisations after training.

Improvisation of tools closely resembles object substitutions in which common items are used as substitutes to improvise in play activities. Both the unavailable item and its substitute may share similar characteristics that will suffice for the given task or play activity. The contrived situation in which the critical tool was missing potentially serves as a motivational variable [Citation21,Citation22] to increase creative use of available items. The interrupted chain procedure, similar to the procedure of improvisation in Parsonson and Baer [Citation20], involves removing necessary items in a series of chained responses to increase verbal request responses. Previous research has demonstrated that interrupted chain procedures effectively increase spontaneous verbal requests in children with ASD [Citation23–25]. For example, some of the items are removed from chained responses (e.g., making coffee, making a sandwich), thus making the participants more likely to request for necessary items in order to complete the task [Citation23,Citation24]. Interrupted chain procedures are also used to teach children with ASD to ask for information, such as “Where is it?” by giving the child an empty box without a toy and “Who is that?” by telling the child that the toy has been given to one of the teachers [Citation25].

A review of the literature suggests that requiring task completion with missing items increases the probability of alternate responses. Additionally, assistive prompts facilitate the acquisition of play responses, and multiple exemplars promote generalization of acquired play responses. It is possible to present play activities in which one of the necessary items is missing while other materials are available as potential substitutes to increase object-substitution symbolic play. Such a scenario is also commonly observed in children’s interactive play, where a child may suggest an activity (e.g., “Let’s cook!”) and another child responds by using a readily available item for that activity in the play context. However, no study has been conducted to evaluate whether object substitutions can be acquired through specific arrangements of play activities for children with ASD. It is imperative to develop an intervention procedure and evaluate the procedure.

To address the research gap and the practical need for interventions targeting complex play for children with ASD, the purpose of this study sought to evaluate the effects of a training procedure on the acquisition, maintenance, and generalization of object-substitution symbolic play in young children with ASD. The procedure consisted of the removal of necessary items in play activities with the addition of multiple substitutes and a least-to-most prompt hierarchy. The following research questions are addressed: (a) to what extent is object-substitution symbolic play acquired and maintained as a result of the intervention? (b) To what extent does the number of object substitutions change in untrained play activities after the intervention? (c) To what extent does the percentage of intervals engaging in symbolic play, functional play, and problem behavior change in a free play setting before and after the intervention?

Method

Participants

The participants were recruited from an inclusive preschool in northeast China. They all attended the preschool full time (8 h per day, 5 days per week). In the morning, they were in the resource room for specialized lessons based on their individualized education plan. The resource room had eight children, aged 3–6 years, with special needs (e.g., ASD, intellectual disabilities, Down Syndrome, developmental delays), one special education teacher, and two teaching assistants. The children were arranged to participate in individual instruction (i.e., 1:1 and 1:2) or small group instruction (e.g., circle time) in this room. They were in two different inclusive classrooms in the afternoon. Qiqi and Zhezhe were in a kindergarten classroom with 25 typically developing children (5–6 years), and Mile was in a preschool classroom with 20 typically developing children (3–4 years). Each inclusive classroom had two to three children with special needs, one head teacher, two teaching assistants, and a shadow for special children. All children participated in group lessons and activities in the inclusive classroom, including language, science, music, art, gym, recesses, and snacks.

The children’s scores on standardized tests were provided by the parents, and their verbal skills were assessed with the Chinese version of the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP) [Citation9,Citation26] by a behavior analyst in private practice. Qiqi was a 5-year-old girl. Her IQ score was 78 (borderline intellectual functioning), measured by the Chinese version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th edition (WISC-IV) [Citation27,Citation28]. Her score on the Chinese version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) [Citation29,Citation30] was 32, indicating mild to moderate autism symptoms. Qiqi’s VB-MAPP indicated that she requested preferred items with phrases (e.g., “want pen”), named at least 200 items/activities, followed at least 50 verbal directions with verbs and nouns, recognized six spatial prepositions (i.e., before, after, over, under, beside, and near), and imitated at least 10 different 3-step actions. She completed 25 fill-in tasks (e.g., “You sleep on the __), answered 25 “what” questions, and 12 “when,” “who,” “which,” and “where” questions. She asked two WH questions (i.e., What’s this?” and “When?”). She did not engage in conversations with peers.

Zhezhe was 5 years old at the time of the study. His WISC-IV IQ score was 59, indicating a mild intellectual disability. He scored 36.5 in CARS, in the category of mild to moderate autism. Based on Zhezhe’s VB-MAPP, he requested preferred items with phrases only when these items were within his eyesight. He named at least 150 objects/activities, followed at least 50 verbal directions with verbs and nouns, and imitated 10 3-step actions involving motor actions and objects. He responded to selection-based questions regarding “what,” “which,” and “who” and answered at least 12 WH-questions. He asked “What” and “When” questions but did not have conversations with peers.

Mile was a 4-year-old boy. His WISC-IV IQ score was 58, indicating a mild intellectual disability. His CARS score was 36 in the category of mild to moderate autism. Based on the VB-MAPP results, Mile requested preferred items within eyesight using the phrase “Help me,” named at least 100 items/activities, followed 50 verbal directions involving verbs and nouns, and imitated two-step directions. He was observed to attend to other children in group activities but did not imitate them. He answered one social question (i.e., What’s your name?) but did not answer any other social questions or engage in conversational speech with others.

Settings and materials

All probe and intervention sessions were conducted in an individual tutor room in the preschool. The room was 2 m × 1.5 m in size with toy/bookshelves attached to the right side of the wall and a table and chairs on the far corner from the door. The instructor and the child sat side by side on the floor with materials for the play activities laid out in front of them within a reachable distance. A video camera was placed on a tripod on their side. The materials used in the probe and intervention sessions included toy items for each play activity and common objects as substitutes ().

Table 1. Themes, activities, missing items, and examples of substitutes used in the study.

Free play observations were conducted in the resource room with the presence of a head teacher, two teaching assistants, and eight children. The resource room was 7 m × 3 m in size with toys, books, and instructional materials placed in organizers against the left wall. As the classroom was limited in space, the teachers had to arrange the play space by moving the table and chairs to the side and placing the toys and books in the space for recesses. The children were free to select activities of their choice. The items available during free play time included books, puzzles, toy cars, LEGO® DUPLO® blocks, snowflake discs, wooden blocks, Play-Doh®, toy musical instruments, and board games. The materials for the play activities with missing items and substitutes used in the intervention sessions were laid out on the table for children during this time.

Pre-experimental play skills assessment

Prior to the onset of the study, all children’s functional play and object-substitution symbolic play skills were assessed with the Developmentally-based Behavior Assessment for Children with Autism (DBACA) [Citation31] to ensure the intervention was appropriate for them. The DBACA is a semi-structured assessment in the domains of cognitive, physical, communication, and social development for children from 2 to 12 years old. It has been field tested in Chinese-speaking children in Taiwan with an average inter-score agreement of 92% (90–100%) and content validity verified by two experts in developmental psychology. The specific procedure for assessing functional and object-substitution symbolic play is described in Lee et al. [Citation10]. All three children scored a 2 (the maximum score) on function play, indicating that they had functional play skills. Qiqi and Mile scored a 0 and Zhezhe scored a 1 for object-substitution symbolic play, suggesting that their symbolic play skills were either not established or weak in their repertoire.

Target selection

The themes and target activities were selected from (a) observations of each participant’s free play activities in the classroom, (b) parental reports of each participant’s preferred activities and routine activities, and (c) observations of play activities by typically developing children in the participants’ classrooms. Each participant was observed in a free play setting where all necessary materials for the target activities were available. If the participant did not engage in the target activities, the target activities were presented with verbal instruction (e.g., “I’m hungry. Can you make some stir-fry for me?”) to complete the activities. The participants were either observed or tested that they could complete the target activities with materials provided.

Experimental design

A single-case experimental design involving multiple-probe across four behaviors [Citation32] was used to evaluate the effects of the procedure on the acquisition and generalization of object-substitution symbolic play. The four behaviors were four target play themes. Each theme included five play activities; each activity had two items missing requiring substitutes for activity completion. Themes 1–4 were taught under the intervention condition; Themes 5 and 6 were used to assess generalization.

The sequence of the conditions included baseline, intervention, and follow-up conditions. Free play observations were conducted prior to baseline and after the completion of the intervention condition for all four themes. Probe sessions for target themes were conducted across all conditions and counted toward criterion. Probe sessions for generalization play themes were conducted at baseline and after each target theme reached mastery criterion. The intervention was introduced to Theme 1 once a stable performance was reached at baseline. When the child achieved 60% accuracy in the intervention condition, baseline probes for Theme 2 were conducted before Theme 2 entered into the intervention condition. The same sequence occurred for subsequent target play themes. The intervention condition for each target play theme was completed when mastery criterion was achieved, which was 90% accuracy in three consecutive probe sessions or 100% in two consecutive probe sessions.

Response definitions

The primary dependent variables included (a) the percentage of correct responses for the target play themes and (b) the percentage of correct responses of the generalization themes in probe sessions. A correct response was defined as the child picked up one of the three substitutes and completed the play activity upon hearing the instructor’s verbal request to complete a play activity. An incorrect response was defined as the child had no response or displayed an irrelevant response to the requested play activity.

The secondary dependent variables included (a) the percentage of 5-s partial intervals engaging in functional play behaviors, (b) the percentage of 5-s partial intervals engaging in symbolic play behaviors, and (c) the percentage of 5-s partial intervals engaging in problem behaviors in free play observations. A functional play act was defined as the child played with an item with its conventional function (e.g., rolling a car). A symbolic play act was defined as the child engaged in (a) an alternate use of an object (e.g., moving a block on a train track), (b) a play activity without the object (e.g., moving his/her hand and saying, “Choo choo” without anything in hand), or (c) labeling an absent attribute of an object (e.g., moving a car and saying, “It is loud”). If the child’s play actions involved both functional play and symbolic play at the same time, it was coded as both. For example, if the child used a bowl as a basket (object- substitution symbolic play) for throwing a ball (functional play) during a 5-s interval, it was coded as both functional play and symbolic play for that interval. An act of problem behavior was defined as the child displayed repetitive or inappropriate play behavior (e.g., repetitive hand/finger movements, lining up/banging/tapping toys repeatedly), stereotyped speech or echolalic vocalizations (e.g., asking the same questions repeatedly), or aggression toward others (e.g., throwing objects toward others, biting, pinching, kicking others). Data of free play observations were collected using 5-s partial interval recording by watching video recordings of each child’s free play sessions.

Procedure

Probe sessions

Probe sessions of the target themes (Themes 1–4) were conducted across baseline, intervention, and follow-up conditions. One probe session was conducted prior to the intervention session for each theme. Each probe session consisted of one theme alternating the presentation of five activities with two missing items for each activity (10 objectives). Thus, a probe session included one theme with a total of 10 probe trials. Probe data were graphed and counted toward criterion. See for the themes, activities, missing items, and examples of substitutes.

Probe sessions for generalization themes (Themes 5 and 6) were conducted prior to baseline and immediately following each theme reached criterion. Follow-up probe sessions for all themes were conducted 1 week, 3 weeks, and 4 weeks after the completion of the intervention.

At each probe session, the instructor and the child sat next to each other on the floor. The materials for five activities of the target theme were placed behind the instructor. Each probe session consisted of 10 probe trials (five activities in one theme and two missing items for each activity). For each probe trial, the instructor presented the materials for one activity and allowed the child to explore the materials for 10 s. Three possible substitutes for the missing item were placed next to these materials. The three substitutes for each missing item were different in each trial, but the items used as possible substitutes shared a similar physical dimension (i.e., shape) with the missing item. After the child explored the materials, the instructor suggested a play activity by delivering an antecedent (e.g., “It’s dinner time. Let’s cook some dumplings”). If the child used one of the substitutes to complete the play activity, the instructor provided positive comments based on the child’s play actions as natural reinforcement to end the trial (e.g., “The dumplings are yummy! You’re a chef”). If the child did not respond correctly (e.g., banging the pot or putting it upside down), the instructor ignored the response and ended the trial. If the child did not respond within 3 s, the instructor ended the trial but provided a general positive comment (e.g., “Nice sitting”) to encourage the child’s participation. The instructors included two female graduate students of special education in their second year who received basic training to conduct research.

The same procedures for the probe sessions across all target and generalization themes were also conducted with six typically developing children in the preschool (three girls, three boys, ages 4–5) as a reference. The average accuracy for these children was 96.8% (95–100%) for all themes with 100% agreement between two observers.

Intervention

Each intervention session contained 10 instructional trials in one play theme with one trial for each objective (10 objectives: five activities and two missing items for each activity). The criterion for each objective was that the child responded to the objective correctly in two probe trials. If the criterion for an objective was met, the objective was then removed and other objectives were presented with more instructional trials in the intervention session.

The procedures for the instructional trials conducted in intervention sessions were identical to probe trials conducted in probe sessions, with the exception that a prompt hierarchy was implemented contingently upon incorrect or no responses. The prompt hierarchy consisted of (a) a gestural prompt of pointing to the substitutes, (b) a verbal direction asking the child to use one of the substitutes to complete the play activity (e.g., “If there are no dumplings, you can pretend those paper clips were dumplings”), (c) the instructor modeling the play activity using one of the substitutes, and (d) full physical guidance (e.g., gently assisting the child to pick up one substitute to complete the play activity). If the child responded correctly with the first prompt, the instructor provided praise to conclude the instructional trial. If not, the instructor ignored the incorrect response and provided the next prompt of the hierarchy until the child responded correctly to end an instructional trial.

Free play observation

Free play observations were conducted before baseline and after the completion of intervention during free play time in the resource room in the presence of teachers and other children. Each observation typically lasted 5, 10, or 15 min, depending on how the child’s classroom teacher organized the schedule for that day. During free play time, all children were free to select his/her own preferred activities in any area of the classroom. The play activities used in the intervention sessions were also available on the table with some missing items and substitutes during free play. The classroom teacher, assistants, and other children had natural interactions during this period of time.

Normative data of functional and symbolic play in the free play setting were obtained from the same six typically developing children who participated in the probe sessions. Each child was videotaped for 15 min in the free play setting with the same arrangements. The children spent 27.7–42.2% (M = 35%) of the time engaging in functional play and 15–43.9% (M = 28.3%) of the time engaging in symbolic play. The agreement between two observers was 98.6% (97–100%; k = .97 range: .76–1) for functional play and 95.5% (95–96%; k = .86, .84–.96) for symbolic play.

Procedural integrity and interobserver agreement

All probe and intervention sessions were videotaped for the purpose of assessing procedural integrity and interobserver agreement. A graduate student naïve to the purpose of the study was trained to assess procedural integrity and interobserver agreement. To assess the procedural integrity of the probe trials, the assessor examined the accuracy of each component involved in each probe trial, which consisted of the antecedent and the consequence for the correct or incorrect response. The assessor also examined each step of implementation (i.e., the antecedent, the prompts provided based on the hierarchy, and the consequence) for each instructional trial. At the same time, the assessor scored each response to evaluate point-to-point agreement for the probe trials. Agreement data for free play observations were assessed based on the response definitions via watching the video recordings.

Procedural integrity was assessed for 30% of the probe sessions randomly selected from each child in each theme across baseline, intervention, and follow-up conditions. It was also assessed for 30% of the intervention sessions randomly selected from each child in each theme. The percentage of procedural integrity was calculated using this formula: accurate steps of implementation ÷ total steps of implementation × 100. The average integrity was 99.2% (90–100%) for the probe sessions and 98.2% (90–100%) for the intervention sessions.

Point-to-point interobserver agreement was assessed for 30% of the probe sessions randomly selected from each theme under each condition for each child and 30% of the free play observations. The formula for the percentage of agreement is: the number of agreement ÷ total the number of agreement and disagreement × 100. The Kappa reliability coefficients (k) were obtained using IBM SSPS Statistics Version 19. According to Cicchetti [Citation33], the level of agreement is poor, fair, good, and excellent when reliability coefficient is below .40, between .40 and .59, between .60 and .74, and between .75 and 1.00, respectively.

The mean agreement for the probe sessions across conditions was 98.4% (k = .96) with a range from 90% to 100% (k: .74-1) for all sessions assessed. The agreement for free play sessions averaged 94.7% (90–98.3%; k = .83, .74–.92) for functional play, 98.7% (97.5–100%; k = .88, .75-1) for symbolic play, and 98.3% (92.8–100%; k = .92, .77-1) for problem behavior.

Social validity

A questionnaire (Supplementary Table S1) for parents was developed by the research team to assess social validity regarding the acceptability, feasibility, and satisfaction of the intervention. The questionnaires were administered after the last follow-up probe session. Of the total 14 items in the questionnaire, Items 1–5 measured the intervention acceptability, Items 6–10 evaluated the feasibility, and Items 11–14 were related to the parents’ satisfaction with the intervention results. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The last item was an open-ended question, asking parents to share their children’s experiences about the intervention or provide suggestions to improve the intervention.

Results

Acquisition of object-substitution symbolic play behavior

Overall, all three children required the most number of prompts in Theme 1, compared to prompts required for Themes 2, 3, and 4. They also required all three types of prompts (i.e., gestural, verbal, and modeling) in the initial intervention sessions for each theme but the number of prompts decreased to a low level in later intervention sessions (Range: Qiqi: 1–23; Zhezhe: 2–30; Mile: 0–50 prompts per session). The average instructional trials to criterion for each theme was 75 (30–150) for Qiqi, 62.5 (30–90) for Zhezhe, and 107.5 (0–200) for Mile.

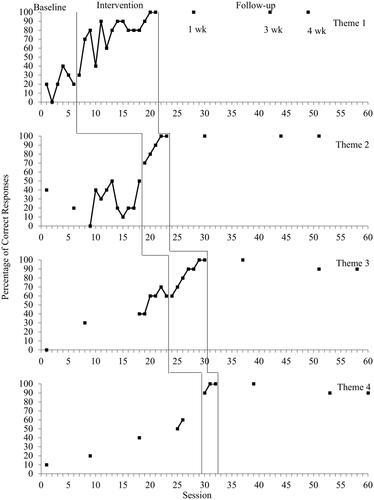

depict the percentage of correct responses in probe sessions for play themes 1–4 across baseline, intervention, and follow-up conditions for Qiqi, Zhezhe, and Mile, respectively. At baseline, Qiqi’s correct responses for Theme 1 were variable at a relatively low level (0–40%). When the intervention was introduced, Qiqi’s correct responses started at a low level, increased to a slightly high level with variabilities in the first six probe sessions, and then gradually ascended to the criterion in the 15th session (30–100%). Similarly, Qiqi’s correct responses for Theme 2 ranged variably between low and middle levels at baseline (0–50%) but increased to a relatively high level with a gradual ascending trend to criterion performance in five sessions in the intervention condition (70–100%). The baseline performance for Themes 3 stared at zero but gradually increased and remained at a middle level (0–70%). Her correct responses started at a middle level, gradually ascended to a high level, and reached criterion in seven sessions for Theme 3 in the intervention condition (60–100%). For theme 4, her baseline performance ranged from 10% to 60%, but immediately increased to 90% and reached mastery criterion in three sessions when the intervention was implemented. All target play themes were maintained at a high level for 4 weeks following the completion of the intervention (90–100%).

Figure 1. Percentage of correct responses for target themes in probe sessions across conditions for Qiqi.

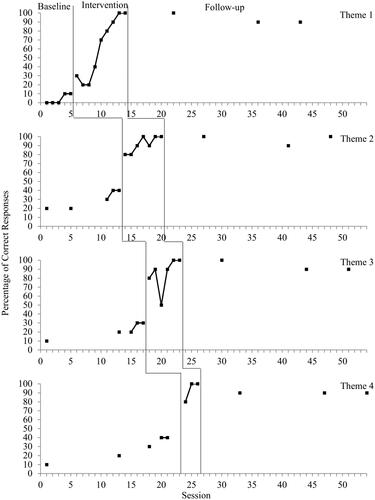

Figure 2. Percentage of correct responses for target themes in probe sessions across conditions for Zhezhe.

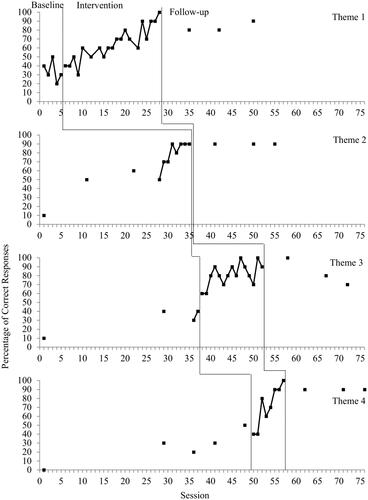

Figure 3. Percentage of correct responses for target themes in probe sessions across conditions for Mile.

Zhezhe had a low level of correct responses for Theme 1 at baseline (0–10%) but increased slightly and gradually ascended to a high level of criterion performance (20–100%) in the intervention condition. Zhezhe’s performance for Themes 2–4 displayed a similar pattern: a relatively low level of correct responses at baseline (Range: Theme 2: 20–40%; Theme 3: 10–30%; Theme 4: 10–40%) and a relatively high level of correct responses in the intervention condition (Range: Theme 2: 80–100%; Theme 3: 50–100%; Theme 4: 80–100%). No data overlaps occurred between baseline and intervention conditions. He required nine, seven, six, and three sessions to achieve mastery criterion for Theme 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. His maintenance performance was at a high level (90–100%) for all play themes in follow-up probe sessions.

At baseline, Mile’s correct responses for Theme 1 were variable within the range between 20% and 50%. His correct responses for Theme 1 started at the same level as baseline but gradually increased with an ascending trend to criterion performance in 20 sessions in the intervention condition. For Theme 2, his baseline performance started at a low level (10%) but increased to a middle level (60%) when the correct responses for Theme 1 had achieved 80% accuracy. His correct responses for Theme 2 continued to ascend and reached criterion in the 11th probe session at baseline without entering into the intervention condition. Mile’s correct responses for Theme 3 were at a relatively low level at baseline (10–40%). When the intervention was introduced, his correct responses increased to a relatively high level, without data overlapping baseline, in a variable ascending trend toward criterion after 15 intervention sessions (60–100%). Similarly, his correct responses for Theme 4 ranged from 0% to 50% at baseline but gradually ascended to a high level and reached criterion after eight intervention sessions (40–100%). In follow-up probe sessions, Mile maintained a high-level performance for all target themes (70–100%) in the follow-up condition.

Generalization of object-substitution symbolic play behavior

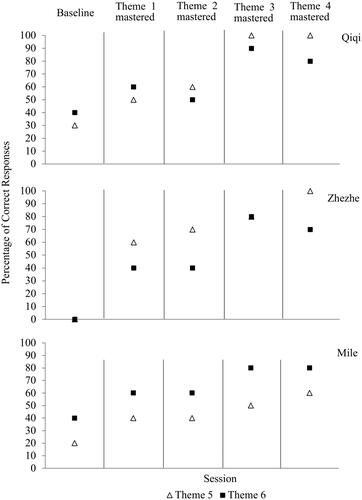

depicts the percentage of correct responses for generalization themes before and after the intervention. Overall, the data displayed a steady ascending trend. Qiqi’s untaught themes started from a relatively low level (30–40%), increased slightly (50–60%) after Themes 1 and 2 reached criterion, continued to a high level (90–100%) after Theme 3 reached criterion, and maintained at the high level (80–100%) after Theme 4 reached criterion.

Figure 4. Percentage of correct responses for generalization themes in probe sessions across conditions for three children.

Zhezhe’s initial performance for generalization themes were zero but increased to a middle level after Themes 1 and 2 reached criterion (Theme 5: 60–70%; Theme 6: 40–40%). His correct responses increased to 80% for both generalization themes after Theme 3 reached criterion. After mastering Theme 4, the percentage of accuracy was 100% for Theme 5 and 70% for Theme 6.

Mile’s data for generalization themes showed that both themes started at a relatively low level (20–40%) and increased to a middle level (40–60%) after Themes 1 and 2 reached criterion. The percentage of accuracy for Theme 6 increased to 80% after Theme 3 was mastered and maintained at the same level after Theme 4 was mastered. However, Theme 5 remained at a middle level (50–60%) after Themes 3 and 4 reached the criterion.

Free play observation

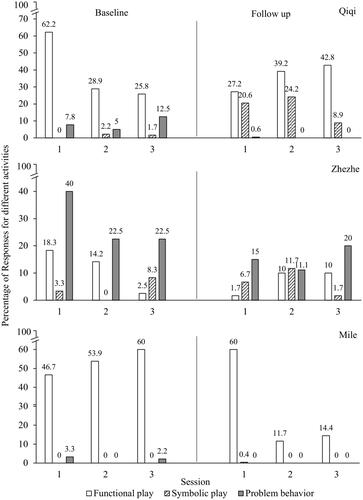

displays the percentage of engagement in functional play, symbolic play, and problem behavior in free play sessions before and after the intervention. Qiqi’s symbolic play averaged 1.3% (0–2.2%) at baseline and increased to 17.9% (8.9–24.2%) after the intervention. Her functional play stayed at a similar level (Baseline: M = 39%, Range: 25.8–62.2%; Follow-up: M = 36.6%; Range: 27.2–42.8%) while problem behavior decreased to almost zero occurrence after the intervention (Baseline: M = 8.4; Range: 5–12.5%; Follow-up: M = 0.2; Range: 0–0.6%).

Figure 5. Percentage of intervals engaging in functional, symbolic play, and problem behavior before and after the intervention for three children.

Zhezhe had a low level of symbolic play at baseline (M = 3.9%, Range: 3.3–8.3%) but increased slightly in follow-up sessions (M = 6.7; Range: 1.7–6.7%). His functional play decreased slightly (Baseline: M = 11.7%, Range: 22.5–40%; Follow-up: M = 7.2%, Range: 1.7–10%) while problem behavior decreased to a relatively low level after the intervention (Baseline: M = 28.3%, Range: 22.5–40%; Follow-up: M = 15.4%, Range: 11.1–20%).

Mile did not demonstrate any symbolic play at baseline but had 0.4% in one of the follow-up free play sessions. His functional play decreased to a relatively low level after the intervention (Baseline: M = 53.5%, Range: 46.7–60%; Follow-up: M = 28.7%, Range: 11.7–60%). He had a low level of problem behavior in baseline (M = 1.8%, Range: 2.2–3.3%) but decreased to zero occurrence in follow-up sessions.

Social validity

One parent for each child responded to the questionnaire and the average ratings were 4 (SD = 0) on intervention acceptability, 4.13 (SD = .35) on feasibility, and 3.75 (SD = .62) on satisfaction of the intervention. All three parents responded to the open-ended question. Qiqi’s mom reported, “Qiqi recently started to initiate pretend play at home. For example, one time she played pretend cooking with blocks and shared these pretend dishes with me.” Zhezhe’s mom noticed that Zhezhe’s pretend play increased during his free play time at home. Additionally, she suggested that we shorten the duration of each intervention session and that the next step of the intervention should focus on increasing Zhezhe’s spontaneous language during play. Mile’s mom also reported that Mile’s pretend play started to emerge and his independent play time also increased, which relieved her some additional time to complete housework. Two parents did not think the intervention improved their children’s play skills in the group setting and suggested that we develop a group-based intervention.

Discussion

The study aimed at teaching object-substitution symbolic play to children with ASD using the procedure consisting of the arrangement play activities with missing items and the use of systematic prompts. The results of the study provided preliminary evidence that the procedure was effective in increasing object substitutions in play activities for young children with ASD. Generalization of object substitutions to untaught play activities occurred in all children. Symbolic play in the free play setting increased for one child after the intervention.

Acquisition of object-dubstitution symbolic play behavior

The procedure used in this study effectively increased target symbolic play behavior for the children. The result was consistent with Parsonson and Baer [Citation20] which was also designed to increase alternate responses for task completion by removing necessary tools while providing substitute items. Similarly, the procedure in this study presented play activities with missing items but multiple substitutes were available, thereby increasing object substitutions in play activities. The role of motivation in increasing object substitutions in play activities can be explained by the value-altering and behavior-altering effects resulting from the arrangement of play activities with missing items. The reinforcing value of a substitute was increased momentarily so the child was more likely to play with it due to a request to complete a task without a necessary item designated for that particular purpose. The alternate responses were to either request for the missing item to complete chained responses [Citation23–25] or use a substitute creatively to complete a given task [Citation20]. In the present study, the children were required to modify their behavior by using a substitute to replace the missing item for ask completion. Therefore, creative uses of substitutes as alternate responses were increased in the play context.

Previous research has incorporated picture prompts into intraverbal training to facilitate creative play actions associated with new names given to an ordinary item [Citation10]. However, the training procedure requires the child to verbalize new names to an item and thus is limited to children who have relatively strong verbal expressions in their repertoire. The analysis of mother-child interactions [Citation11] and observations of children’s play activities suggest that object-substitution symbolic play can occur with or without speakers’ responses. In the present study, the verbal request to initiate a play activity simulated mother-child interactions but did not require the child to provide intraverbal responses. Thus, this procedure is appropriate for children who have limited speakers’ responses but demonstrate functional play but not symbolic play in their repertoire.

The assessments of specific play skills were important to determine whether the intervention was developmentally appropriate for the children. As suggested, functional play comes before symbolic play in the developmental sequence [Citation34], and therefore, the children must demonstrate strong functional play skills. The assessment of object-substitution symbolic play also provides supporting evidence that specific intervention targeting this type of play behavior is necessary.

Generalization of object-substitution symbolic play to untaught activities

The results of the study indicated that the interrupted chain procedure also facilitated generalization to untaught play activities (Themes 5 and 6) for all three children. Overall, the correct responses for generalization themes increased slightly after Theme 1 achieved criterion, stayed at the same level after Theme 2 reached criterion, ascended to a high level after acquiring Theme 3, and maintained at a high level after Theme 4 was mastered. It is suggested that the mastery of at least three play themes was required for generalization to occur at a high level of accuracy. One exception was that Mile acquired all objectives in Theme 2 at baseline without entering into the intervention, suggesting potential confounding extraneous variables at baseline. His mother reported that she and Mile had read a book pertaining to doll houses (Theme 2) and engaged in similar play activities at home. Thus, Mile’s experiences and familiarity with the activities in Theme 2 may have an impact on the results of the study.

As discussed, the verbal request inviting the child to complete a given task closely simulated children’s interactions, thus making generalization to other play activities more likely to occur. That is, the children have acquired generalized object substitutions by “improvising” from a substitute for the suggested play activity as in Parsonson and Baer [Citation20]. In this case, the alternate response of using a substitute in the play context constituted an act of object-substitution symbolic play behavior as a result of the arrangement of missing items with only substitutes available.

The multiple-exemplar experiences were further enhanced in the intervention sessions in which each theme included different activities and missing items with varied substitutes available for each instructional trial. Therefore, generalized alternate responses across missing items and their substitutes were established as a result. Such multiple exemplar training has been incorporated with video-based instruction to increase generalized pretend play to novel toys in children with ASD [Citation14]. The potential sources of reinforcement for task completion may be the play activities themselves, the opportunities to interact with another person, or adult praise. In this study, adult praise and comments were used as reinforcers to strengthen target play behavior. Tangible reinforcers were only used after intervention sessions, if requested by the children. Together, the presentation of play activities with missing items, multiple exemplars of activities and substitutes, the prompt hierarchy, and the reinforcement contributed to generalized creative uses of substitutes as in object-substitution symbolic play.

Free play observation

Free play observations showed that Qiqi’s symbolic play was increased to be within the range of the normative data after the intervention. Zhezhe’s symbolic play also increased slightly but did not reach the lower range of the normative data. Mile’s symbolic play did not increase after the intervention. Qiqi’s functional play stayed at the same level while the other two children’s functional play decreased after the intervention. All children’s problem behavior deceased during post-intervention free play sessions. Specifically, Qiqi and Mile had zero or a very low level of problem behavior with a concurrent increase in functional and symbolic play after the intervention. Although Zhezhe’s problem behavior decreased after the intervention, it was at a relatively high level compared to his functional and symbolic play behaviors, suggesting that problem behavior remain a barrier. The presence of Zhezhe’s problem behavior may be related to his limited improvement in symbolic play and the decrease of functional play in the free play setting. Additionally, an examination of the free play videos indicated that Zhezhe and Mile started to engaged in observing other toys or others’ play activities in free play sessions after the intervention. The increased observing behaviors of the two children may partially explain the decrease in their functional play as these behaviors were not coded.

Previous research has rarely evaluated generalization of acquired play skills in natural free play settings with the presence of other children. Barton [Citation15] conducted such observations and reported that children’s symbolic play increased in a free play setting. However, the increased level in the free play setting was lower than that in the instructional setting. Consistent with Barton [Citation15], the results of free play observations also indicated that the children’s symbolic play increased slightly in the free play setting. Despite increases in symbolic play or functional play, the children in this study did not engage in any play behaviors for the majority of time during free play, suggesting that toys were not conditioned reinforcers [Citation35]. Therefore, intervention procedures aimed at conditioning toys as reinforcers may be necessary to increasing engagement in toy play for these children. As discussed, the potential sources of reinforcement may come from the play activities, the interactions, or social praise. Besides toys not functioning as reinforcers, the low level of symbolic play may be partially explained by the fact that the availability of various toys and few initiations of others existed in the free play setting, compared to the limited play materials and adult initiations for play activities in the instructional setting.

Limitations and future directions

There are some limitations to this study. First, the procedure focused on responding but not initiating a symbolic play activity due to the fact that the antecedent events included a necessary item was missing and a verbal request to complete a task in the play context. Although verbal requests effectively established target symbolic play behaviors, they also inadvertently served as a prompt to prevent initiations by the child. Future researchers may refine this procedure by including a verbal request initially and then removing it when the target behavior is established. Additionally, future researchers can consider using peer mediation and implementing this procedure in the classroom. Second, the play themes used in this study may not necessarily be independent of each other. The covariation was evident as Mile reached mastery criterion for Theme 2 without intervention. Experimental control is compromised for themes that showed an increasing trend in correct responding at the time intervention was introduced (e.g., Qiqi themes 2 and 4, Zhezhe theme 1, Mile themes 3 and 4). Thus, the multiple-probe across behaviors design may not be the best option for this study. Additionally, the intervention was introduced prematurely for Qiqi’s Theme 3 while the baseline data displayed an ascending trend. It is necessary to continue baseline until a stable state is reached before entering into the intervention. Thus, the conclusions that can be drawn from the intervention are tenuous. It is possible that additional exposure to the play activities at baseline resulted in improvements in performance. As such, the specific mechanisms responsible for increases in symbolic play are unclear. Third, the effect of withdrawing items as a motivational variable was not isolated as the opposite condition (i.e., no missing items) was not included in the study, and therefore, it is not clear which components in the procedure (i.e., the missing items, the substitutes, and the prompt hierarchy) was responsible for behavior change. Although the children were tested or observed to perform the target play activities when necessary items were presented prior to the baseline, all children required all levels of prompts in the hierarchy to acquire the target behavior. It is possible that the children could still acquire the target play behavior without necessary items removed, as suggested by previous studies [Citation15,Citation36]. It is necessary to include the experimental condition in which all play materials are included to evaluate the effect of the motivational variable in future studies.

Reinforcement for correct responses implemented in probe sessions across conditions was designed for the purpose of isolating the effects of the procedure on the acquisition and generalization of the target symbolic play behaviors. If no reinforcement was delivered for correct responses in probe sessions, it is likely to put desired responses into extinction. Although reinforcement alone is likely to increase correct responses at baseline, the overall data indicated a limited effect of reinforcement until the intervention was introduced, except for Mile’s Theme 2. As discussed, the potential attribute to Mile’s criterion performance for Theme 2 without intervention was possibly related to exposures of similar play activities outside of the study. It is necessary to control such extraneous variables in future studies.

Despite these limitations, the results of the study were promising and have important implications for the intervention of play behaviors for children with ASD. The procedure developed based on the analysis of behavioral processes involved in object-substitution symbolic play can be an important initial step to increase such complex play behavior in children with ASD. The assessment of specific play skills is necessary for individualized play intervention. Relevant motivational arrangements can be incorporated into children’s play activities to evoke spontaneous complex play behavior in the play context for children with ASD who lack such play skills.

Supplementary_Table_S1.pdf

Download PDF (123.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- McCune L. Developing symbolic abilities. In: B. Wagoner, editor. Symbolic transformation: the mind in movement through culture and society. London (UK): Routledge Press; 2010. p. 193–208.

- Copple C, Bredekamp S, National Association for the Education of Young Children, editors. Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. 3rd ed. Washington (DC): National Association for the Education of Young Children; 2009. p. 352.

- McCune L. A normative study of representational play in the transition to language. Dev Psychol. 1995;31(2):198–206.

- Barton EE. Development of a taxonomy of pretend play for children with disabilities. Infants Young Child. 2010;23(4):247–261.

- Barton EE, Wolery M. Teaching pretend play to children with disabilities: a review of the literature. Top Early Child Special Educ. 2008;28(2):109–125.

- Leslie AM. Pretense and representation: the origins of “theory of mind”. Psychol Rev. 1987;94(4):412–426.

- Baron-Cohen S. Autism and symbolic play. Br J Dev Psychol. 1987;5(2):139–148.

- Partington JW. ABLLS-R – The Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills – Revised (The ABLLS-R). 3.2 ed. Pleasant Hills (CA): Partington Behavio Analysts; 2010.

- Sundberg ML. VB-MAPP: verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program. 1st ed. Concord (CA): AVB Press; 2008.

- Lee GT, Feng H, Xu S, et al. Increasing “object-substitution” symbolic play in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Behav Modif. 2019;43(1):82–114.

- Horne PJ, Lowe CF. On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. J Exp Anal Behav. 1996;65(1):185–241.

- Dauphin M, Kinney E, Stromer R, et al. Using video-enhanced activity schedules and matrix training to teach sociodramatic play to a child with autism. J Positive Behav Interv. 2004;6(4):238–250.

- MacManus C, MacDonald R, Ahearn WH. Teaching and generalizing pretend play in children with autism using video modeling and matrix training. Behav Intervent. 2015;30(3):191–218.

- Dupere S, MacDonald RPF, Ahearn WH. Using video modeling with substitutable loops to teach varied play to children with autism. J Appl Behav Anal. 2013;46(3):662–668.

- Barton EE. Teaching generalized pretend play and related behaviors to young children with disabilities. Exceptional Child. 2015;81(4):489–506.

- Lydon H, Healy O, Leader G. A comparison of video modeling and pivotal response training to teach pretend play skills to children with autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2011;5(2):872–884.

- Stahmer AC. Teaching symbolic play skills to children with autism using pivotal response training. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(2):123–141.

- Kasari C, Freeman S, Paparella T. Joint attention and symbolic play in young children with autism: a randomized controlled intervention study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(6):611–620.

- Kasari C, Gulsrud A, Freeman S, et al. Longitudinal follow up of children with autism receiving targeted interventions on joint attention and play. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(5):487–495.

- Parsonson BS, Baer DM. Training generalized improvisation of tools by preschool children. J Appl Behav Anal. 1978;11(3):363–380.

- Michael J. Establishing operations. Behav Analyst. 1993;16(2):191–206.

- Michael J. Motivating operations. In: Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL, editors. Applied behavior analysis. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Merrill Prentice Hall; 2007. p. 374–391.

- Albert KM, Carbone VJ, Murray DD, et al. Increasing the mand repertoire of children with autism through the use of an interrupted chain procedure. Behav Anal Pract. 2012;5(2):65–76.

- Hall G, Sundberg ML. Teaching mands by manipulating conditioned establishing operations. Anal Verbal Behav. 1987;5(1):41–53.

- Sundberg ML, Loeb M, Hale L, et al. Contriving establishing operations to teach mands for information. Anal Verbal Behav. 2001;18(1):15–29.

- Huang WH, Li D. Yu yan xing wei li cheng bei ping gu yu an zhi cheng xu [Tran: The verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program: The VB-MAPP]. Beijing (China): Peking University Medical Science Publishing House; 2017.

- Wechsler D. Wechsler intelligence scale for children® – fourth edition. San Antonio (TX): Psychological Corporation; 2003.

- Zhang HC. Wei shi er tong zhi li liang biao-di si ban [The Wechsler intelligence scale for children–4th edition]. Zhuhai (China): King-May Psychological Assessment Technology Development, Ltd.; 2008.

- Lu JP, Yang ZW, Shu MY, et al. Er tong gu du zheng liang biao ping ding de xin du xiao du fen xi [Reliability and validity analysis of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale]. Zhong guo xian dai yi xue za zhi. 2004;14(3):119–123.

- Schopler E, Reichler RJ, Renner BR. The childhood autism rating scale (CARS). Los Angeles (CA): Western Psychological Services; 2002.

- Feng H, Sun W-C. Tzu-pi cheng fa chan pen wei ping liang hsi tung [Developmentally-based behavior assessment system for children with autism]. Taipei (Taiwan): Hua-Teng Publisher; 2017.

- Gast DL, Lloyd BP, Ledford JR. Multiple baseline and multiple probe designs. In: Ledford JR, Gast DL, editors. Single case research methodology: applications in special education and behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Routledge; 2018. p. 239–282.

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284–290.

- Lifter K, Sulzer-Azaroff B, Anderson SR, et al. Teaching play activities to preschool children with disabilities: the importance of developmental considerations. J Early Intervent. 1993;17(2):139–159.

- Nuzzolo-Gomez R, Leonard MA, Ortiz E, et al. Teaching children with autism to prefer books or toys over stereotypy or passivity. J Posit Behav Intervent. 2002;4(2):80–87.

- Qiu J, Barton EE, Choi G. Using system of least prompts to teach play to young children with disabilities. J Spec Educ. 2019;52(4):242–251.