Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate a dog-walking program (called “Dog Buddies”) designed to address the need for evidence-based programs that create opportunities for people with cognitive disabilities to be more socially included in mainstream society. The research question was: Does community dog walking foster social interaction for people with cognitive disabilities?

Materials and methods

Single-case experimental design was used with four individuals (three with intellectual disability; one with Acquired Brain Injury (ABI)) recruited via two disability service providers in Victoria. Target behaviours included frequency and nature of encounters between the person with disability and community members. Change was measured from baseline (five community meetings with a handler but no dog) to intervention period (five meetings minimum, with a handler and a dog). Semi-structured interviews, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, provided three participants’ subjective experiences of the program.

Results

Dog Buddies increased the frequency of encounters for all participants. The presence of the dog helped to foster convivial encounters, community members were found to be more welcoming, and some participants were recognised or acknowledged by name over time in the intervention phase.

Conclusions

The dog-walking program offered a simple means of influencing the frequency and depth of community-based social interactions for people with cognitive disabilities.

The co-presence of people with disabilities in the community with the general population does not ensure social interaction occurs.

Both disability policy, and the programs or support that is provided to people with disabilities, needs to have a strong commitment to the inclusion of people with disabilities in mainstream communities.

Dog Buddies is a promising example of a program where the presence of a pet dog has been demonstrated to support convivial, bi-directional encounters of people with cognitive disabilities and other community members.

Dog-walking offers a simple means of influencing the frequency and depth of community-based social interactions for people with cognitive disabilities.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) outlines an imperative to ensure full and effective participation and inclusion in society of people with disabilities [Citation1]. Internationally, governments invest in a range of programs and strategies with the aim to build the inclusion of people with disabilities [Citation2–3]. However, research shows many of the funded human supports, assistive technology and supported housing options fail to assist people with disabilities to develop social connections in their local communities [Citation4–5]. This has been shown to cause exclusion for people living with cognitive disabilities, including people with intellectual disabilities [Citation6–7] and Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) [Citation8–9].

People with cognitive disabilities face additional barriers to social inclusion, including making decisions and expressing preferences regarding social activities that are important to them. Some of these may be directly related to existing cognitive-communication disorders [Citation10–12]. However, experiences are also shaped by community attitudes. When negative attitudes exist, these can present barriers to social inclusion in various life domains including community participation [Citation4,Citation8,Citation11]. Due to these combined factors, people with cognitive disabilities may experience few relationships with people other than paid staff or family [Citation9,Citation13–16], spend significant amounts of time in passive, home-based leisure tasks [Citation13,Citation17,Citation18], experience social isolation and feelings of loneliness [Citation13,Citation17,Citation18], and experience reduced self-determination and marginalisation [Citation11,Citation13,Citation19,Citation20].

Poor social and community integration outcomes not only affect the person with disability, but also impact quality of life outcomes of informal supporters. For people with cognitive disabilities, family members are one of the main social resources available – even when they are not living with the person with disability – and often are a key enabler to facilitating community participation [Citation21]. Family functioning and distress in relatives of a person with ABI have previously been found to be heightened when the relative with ABI was socially isolated, had few activities outside the family home, and had minimal leisure interests [Citation9,Citation22]. Past research has therefore highlighted the need for increased community resources and a stronger emphasis on programs that aid meaningful community participation [Citation9].

To enact the CRPD and avoid the potential of many years of negative psychosocial sequelae for the individual, their families and society as a whole, community integration outcomes that support social interaction must be improved [Citation4,Citation11]. Recent research however has highlighted both the personal lived experience, and complex and situated nature, of participation in meaningful activity [Citation23–24]. Building social participation opportunities for people with cognitive disabilities can be challenging, and may require targeted interventions as studies suggest that community presence alone does not lead to social inclusion [Citation9,Citation13–16,Citation19,Citation25].

Researchers have started to use the concept of “encounters” between strangers as a different way of thinking about social inclusion. Bigby and Wiesel [Citation26–27] investigated the nature and role of encounters in fostering social inclusion of people with cognitive disabilities, and the influence of support practices and other contextual factors on inclusivity of places and conviviality of encounters. Animals have been identified as an enabler to convivial encounters (involving a shared activity/common purpose with someone else, e.g., conversation about dogs). Specifically, for people with physical disabilities, studies have shown assistance [Citation28] and pet [Citation29] dogs can facilitate social interactions, and reduce social ostracism [Citation27]. Although there is a significant difference in the role of assistance animals versus pets, and specific to these two studies the dogs were not working in the same capacity, both suggest it was the animal’s presence that made the difference. More recently, assistance dogs were utilised by Bould and colleagues [Citation30] to pilot an individual dog-walking program in regional Victoria, Australia. The authors used evidence from the general population that walking with a pet dog fosters social interaction [Citation31–33] and proposed that dogs could act as catalysts for the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities [Citation30]. A comparison of two groups in that study (those who went out with a dog compared to those who went out without a dog) showed there were significantly more encounters between participants and strangers when a dog was present. Furthermore, those accessing the community with a dog experienced more positive encounters with other community members, were more quickly recognised and acknowledged, and showed greater confidence engaging with strangers.

The findings from Bould et al. [Citation30] demonstrate the feasibility and potential efficacy of animal assisted activity (AAA) programs as a means of influencing the frequency and depth of social interactions for people with intellectual disabilities. However, the Bould et al. [Citation30] study involved dogs and dog handlers from an assistance animal organisation with public access rights (i.e., the dog handler and dog were able to go inside cafés and shops). To date, there has been no research which has examined the effectiveness of AAA programs involving pet dogs and their handlers, who do not have the same public access rights. Rather, in Australia, business owners can choose whether or not they permit pet dogs onto their premises. Further research is also required to ascertain if such a model could extend to people experiencing other significant and permanent cognitive disabilities, for example people with ABI. By influencing the frequency and depth of community-based social interactions, this could influence a person’s mental health and wellbeing and improve their ability to adjust to life after injury [Citation34].

The current Australian disability policy and practice context is conducive to further exploration of the role of dogs in fostering social connections and inclusiveness. A no-fault $22B National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) funds “reasonable and necessary” disability related supports for 449,998 Scheme participants aged under 65 years at Scheme entry, with the second highest spend (16.2%) directed towards supporting social and community participation [Citation2,Citation35]. Nevertheless, an evaluation of the NDIS found no econometric evidence that the Scheme has impacted the social participation of people with disabilities, with cost, access, transport and communication cited as persistent barriers [Citation36]. To improve both Scheme and individual participant outcomes, there is a need to bring to the disability marketplace evidence-based programs that create opportunities for people with disabilities to have social interactions with people without disabilities in the community [Citation18,Citation26,Citation37].

The aim of the current study was to: (1) address some of the methodological limitations Bould et al. [Citation30] identified in their pilot study (i.e., only recording the total number of encounters); and (2) extend the dog-walking program to include pet (rather than assistance) dogs, as well as other groups of people experiencing cognitive disabilities living in Victoria, Australia. This could support the establishment of dog-walking programs that take account of the low level of pet ownership among people with cognitive disabilities who live in supported accommodation settings [Citation5], by connecting a dog and their owner and individualised support for people with disabilities to regularly engage with and/or walk a dog in their local community. The research question was: does community dog walking foster social interaction for people with cognitive disabilities?

In undertaking this research, the aim was to explore whether a pet dog accompanying a person with disability in a community space (such as a café, shopping centre or within local streets) could increase the frequency and depth of social interactions for people experiencing cognitive disabilities and the community members they engage with, and thus creating opportunities for greater social inclusion.

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from Monash University Human Research and Animal Ethics Committees (project ID’s: 22070 and 22072), prior to commencement of data collection.

Design

Mixed methods were used to evaluate the AAA program designed, which was called Dog Buddies. Single-case experimental design (SCED), applying the Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials Scale [Citation38], was used to determine the effect of the dog-walking program on the total number and different types of encounters, the dependent variables. An A-B design was used, repeated across four participants, and conducted as per design specific recommendations [Citation39–41], with each participant serving as his or her own control. The rationale for selecting this design to evaluate the intervention is the suitability of SCEDs for situations where the acceptability of the intervention and the feasibility of a randomised controlled trial have yet to be established. Such situations include participant heterogeneity and difficulty recruiting adequately powered samples, both of which applied in this study. The SCED methodology provides a means to test for cause-effect functional relationships between the intervention and its effect on the frequency and type of encounters, as well as the effect that repeated encounters can have on inclusivity and being known [Citation27,Citation42].

During each baseline and intervention meeting, the dog handler counted the total number and different types of encounters the participant experienced, using a customised printed form. At the end of each meeting, the handler then completed an online survey via Qualtrics (Supplemental Appendix A) including qualitative data to provide repeated measurements during the baseline phase, which was compared with the intervention phase, when the dog was introduced. Data recorded by the handler also included written descriptive information about each encounter, and handler reflections about each participant’s observed experiences during each meeting. Post-intervention, semi-structured interviews (Supplemental Appendix B) with the participant (where the person had the cognitive ability to participate in an interview) and a nominated support person explored subjective perspectives and experiences of the program. These qualitative data were combined to generate narratives of participants’ engagement with the program.

Participants

A sample of four participants was recruited by invitation between November and December 2019 via two registered NDIS providers offering home and community services (e.g., community participation, work capacity building, education and support initiatives) in metropolitan Victoria, Australia. The invitations asked organisations to circulate the information among the people they support and to assist anyone interested in hearing more about the study to contact the research team. Eligibility criteria comprised of being 18 years or older, experiencing a cognitive disability (e.g., intellectual disabilities; ABI), living in a community dwelling, a stated and/or demonstrated interest in participating in an activity with a dog in the community, and in receipt of NDIS-funded disability services.

Study timeframe

Due to the escalating COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, and the imposed lockdown in Victoria in 2020, the Dog Buddies program ran for an extended period from December 2019 to April 2021. A break in the program was required as part of government-enforced stay-at-home and physical distancing restrictions in place between March 2020 and January 2021.

Procedure

After the third-party recruitment process, written explanatory processes and signed consent for the research (with the option of consent for photography during the intervention phase) was gained from either the participant or their next of kin (for participants who required support for decision-making and the provision of informed consent). Participants and their key supporters were informed the study involved regular one-hour meetings in the local community; the first five meetings being with the handler alone (baseline Phase A), after which the intervention (phase B) – that is, the Dog Buddies program – would be implemented and the handler’s pet dog (a Labrador) would join them for all other meetings.

The intervention phase – “Dog Buddies”

The Dog Buddies program involved a person with cognitive disability going out into their local community with a dog handler and the handler’s pet dog. The handler, a doctoral candidate and a qualified teacher at a school with people with disabilities, received training from the first author (EB) prior to the program commencing. This included information about the micro-strategies needed to support, rather than obstruct, convivial encounters [Citation26]; definitions and features of the different types of encounters to be recorded; and how to complete the in vivo data collection and photography (where participant consent was provided), online survey data entry, and semi-structured interviews.

The handler’s dog (an eight-year-old Labrador, called “Barney”) had been trained and evaluated in public sectors and had a resulting good temperament. Although the dog had not received training or been evaluated to work with people with cognitive disabilities, the dog walked easily on a lead (i.e., at a gentle pace, and generally did not pull) and was known to be willing to accept pats from strangers, and be friendly towards other people and dogs. This was important given the overall aim of the program.

To build rapport, the handler (without their dog) initially met each participant at a location chosen by the participant, along with a nominated key support person. They talked about the Dog Buddies program, and discussed interests and the type of activities the participant would like to do in the community (e.g., visit cafes, shops, walks in local parks or the local community). The handler was also able to seek information on the participant’s support requirements, for example, their communication needs, or any physical or behavioural issues that may cause potential risks. No data was collected during this meeting. The participant and handler subsequently went out into the community five times without the dog (baseline phase A), after which the handler’s dog joined them for a minimum of five further meetings (intervention phase B). During the phase A and phase B meetings, a nominated support person only attended if requested by the participant. Although each participant was encouraged to go out regularly (with meetings scheduled the same time each week), the timing of each meeting remained flexible and study data collection provided a record about the pattern of meetings, and participants’ preferred frequency and number of meetings.

Instrumentation

Customised questionnaire

A measure of participant characteristics, community integration, and formal support arrangements was obtained via a customised questionnaire completed by a key support person who knew the study participant well. The questionnaire contained items about each participant’s gender, date of birth, disabilities experienced, and living situation. It also included the short form of the Adaptive Behavior Scale (ABS) Part 1 [Citation43], and the Quality of Social Impairment question from the Schedule of Handicaps Behaviours and Skills (HBS) [Citation44] to measure level of cognitive disability and social impairment respectively. For the participant with ABI, the Overt Behaviour Scale (OBS) [Citation45] was included in the questionnaire to measure presence or absence of nine categories of challenging behaviour, whilst the Aberrant Behavior Checklist [Citation46] was used to measure level of challenging behaviour for participants with intellectual disabilities. To understand the baseline level of engagement in a range of home, social and community activities, the final section of the questionnaire included the Community Integration Questionnaire-Revised (CIQ-R) [Citation47]. The CIQ-R allowed comparison of study participants’ scores with that of the CIQ-R normative data set matched on age, gender and living location [Citation47]. The reliability and validity of the published measures have been reported as acceptable by their authors.

Observational measure of encounters

A paper-based printed form was marked within each meeting, and then entered into an online survey. The survey was designed to record the frequency of the dependent variables, the total, and different types of encounters identified in the literature [Citation27,Citation42]. This included: positive encounters (defined as moments of conviviality; fleeting exchanges; or service transactions); exclusionary encounters (disrespectful comment or interaction from others that signals the person is not welcome because of their difference); and unfulfilled encounters (an opportunity for social interaction existed but the person with disability did not engage with the other person). Open-ended questions in the survey captured the handler’s perceptions of each participant’s experiences, their observations and reflections about each meeting, as well as a description of each encounter that occurred for the participant. This included: what happened in the encounter; who was involved; whether the participant was recognised by face; or whether they had become known by their name.

Photography

If agreed by the participant as part of the consent process, the dog handler took photographs during each meeting within the intervention phase, which were used as a visual prompt during the semi-structured interview at the end of the intervention period. These photographs were also provided to participants at program completion, for their own records and to share with others as desired.

Semi-structured interviews

Within two weeks of completion of the intervention period, the participant and a nominated support person were invited to take part in a semi-structured interview to capture their subjective experiences of the Dog Buddies program. Particular attention was paid to the interview design, to ensure it was accessible and inclusive of the perspectives of the participants, whilst accommodating their cognitive communication needs. As such, the semi-structured interview schedule was used flexibly, and to minimise any risk of stress and anxiety the interview took place at a location chosen by the participant (most often this was where the intervention had taken place e.g., a cafe; a park).

The interview schedule consisted of questions about why the participant wanted to take part in the program; what they liked or did not like; what difficulties and/or challenges they experienced; whether the program had made any difference to their life, including helping them to get to know new people or develop community social connections; and, whether they felt the program could be beneficial to other people. Two strategies were used to stimulate reflection and descriptions from study participants during the interview. The handler (who was known to each participant) conducted all interviews, and was accompanied by their dog during the interview process. If agreed by the participant as part of consent process, the photographs that were taken during the Dog Buddies program were then used as an additional visual prompt to promote reflection and discussion. Interviews ranged in duration from 10 and 20 min, were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim by the lead author (EB), with pseudonyms applied at the time of transcription to protect participants’ identities.

Analyses

Questionnaire data were entered into SPSS 27 statistical software and analysed using descriptive statistics to report demographic and disability related characteristics. For each participant an Adaptive Behaviour Scale (ABS) Part 1 score was derived from the short adaptive scale using the formula provided in Hatton et al. [Citation43]. A higher score indicates a higher level of adaptive behaviour, and a score of 151 or below indicates that a person has severe or profound level of cognitive impairment [Citation48]. For the participant with ABI, a count of presence of challenging behaviours, as measured by the OBS, was undertaken. For the participants with intellectual disabilities a total score on the ABC was calculated. A higher score on either the OBS and ABC indicates a higher presence of challenging behaviour [Citation45–46]. A total score on the CIQ-R was also calculated, comprising all 18 items, with potential scores ranging from 0 to 35 and this was compared to scores from the normative data set matched on age, gender and living location. A higher score on the CIQ-R indicates a higher level of community integration [Citation47].

The online survey data was exported from Qualtrics into SPSS 27 statistical software and for each participant the total number of positive, exclusionary and unfulfilled encounters were calculated for each meeting. Each case was evaluated separately, using a standard protocol for structured visual analysis, focusing on six features of the data making both within- and between-phase comparisons for response level, trend, variability, immediacy, consistency, and overlap [Citation49]. Percentage of data exceeding the median (PEM) was calculated to determine effect sizes. These can range from 0 to 100 percent [Citation50–51] and was calculated by determining the percentage number of intervention data that exceeded the median data point of the baseline phase. A score of 90%+ indicates the intervention was highly effective, 70–89% moderately effective, 50–69% minimally effective, and <50% ineffective [Citation52].

Two authors (EB and NW) analysed data from the online surveys and semi-structured interviews (conducted with three of the participants) using a narrative analysis approach [Citation53]. The existing literature about the different types of encounters [Citation27,Citation42] was used as a guide for constructing stories from the perspectives of the handler, the participant and their nominated supporter. Data from the semi-structured interviews with participants was limited, due to cognitive disabilities that impacted participants’ recall, and verbal expression of their perceptions and experiences. However, reflections recorded by the handler in the online survey captured verbal and nonverbal expressions (e.g., comments, gestures, facial reactions) of participants, providing additional rich information to aid analyses of participants’ experiences.

Results

Description of participants

Demographic and disability related characteristics are presented in . As can be seen, participants varied in age (23–61 years), three participants had a primary diagnosis of intellectual disability, two of whom also had autism, and one participant had an ABI.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Encounters

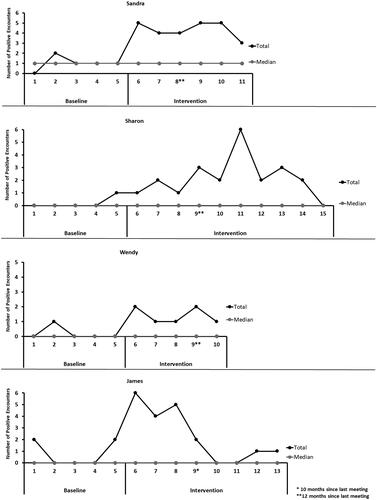

Visual inspection of the data indicated the presence of effects for the total number of positive encounters for each of the four participants. provides the dependent variable data for total number of encounters. The intervention was highly effective in increasing the frequency of encounters for the three participants with intellectual disability (Sandra (100%), Sharon (90%) and Wendy (100%)), and moderately effective (75%) for James, who was the participant with ABI. There was no effect for the number of exclusionary and unfulfilled encounters. For James, the handler was only able to record the presence or absence of unfulfilled encounters (not the total number that occurred), and he had no exclusionary encounters. Whereas for the other three participants there was one exclusionary encounter recorded (for Sandra at baseline), and unfulfilled encounters occurred in one meeting for Wendy, and two meetings for Sharon.

Figure 1. Single baseline for total number of positive encounters that occurred. The numbers on the x-axis indicate the meeting number in which data collection occurred.

Qualitative findings

Deidentified case studies are presented below for each of the participants to illustrate the main themes identified during data analysis.

Sandra

Sandra, aged in her 60's, lives in shared supported accommodation with 24-h staff support. Sandra’s overall CIQ-R score was 16, which is lower (meaning Sandra is less integrated into the community) than the Australian general population normative score of 22.66, when matched on age, gender and living location [Citation47]. She met with the handler eleven times over the course of the program; the first five, which did not include the dog, are summarised in .

Table 2. Summary of Sandra’s first five meetings (baseline Phase A) in the Dog Buddies program.

As shown in , Sandra’s confidence in interacting socially increased across the five meetings. This was partly facilitated by the routineness of each meeting: going to the same place each week to get coffee led to Sandra becoming known by the barista, and created positive encounters. As the handler noted, “when Sandra held out her money, the barista asked, ‘same coffee as last time?’ ” This increasing sociality was especially evident during the sixth meeting, when the handler’s dog, Barney, first accompanied Sandra for her outing to the coffee van. During this meeting, while walking Barney, Sandra both learned elements of dog care and had social interactions with people who she encountered. She had three fleeting social exchanges, and one fleeting moment of conviviality noted by the handler: “On our walk, we walked past four huskies. The owners were sitting at a bench. Sandra asked them what type of dog it was, and the owner replied to her.” This was a noticeably different interaction than Sandra had demonstrated in the previous meetings, and was followed by a longer exchange: “A woman heard us trying to work out the type of dog. She approached us and Sandra asked questions: ‘What type of dog? Boy or girl? Where does he sleep? What does he eat?’.”

The presence of Barney in the subsequent meeting gave Sandra more opportunities for social interaction. The handler noticed that this seemed to lead to more conversation between her and Sandra: “Sandra was increasingly chatty with me, sharing what she did on the weekend. She noticed the Guide Dogs Victoria emblem on my hat and we talked about what guide dogs do. She enjoyed giving Barney treats.”

Despite the success of the program in supporting Sandra’s social involvement, escalating government restrictions due to COVID-19 interrupted the schedule. There were also other factors that impacted Sandra’s participation, mostly based on conflicting messages from support workers and senior leaders from the disability service about Sandra’s interest in the program – there were some reports that Sandra was enjoying and wanted to continue the program and some that she did not. Ultimately, Sandra decided to continue with the program, with meeting eight occurring one year after the previous meeting. This meeting again involved a visit to the coffee van, and there was both a friendly service transaction, in which Sandra spoke to the barista, and two fleeting moments of conviviality, and one slightly longer exchange noted: “Whilst walking back from the coffee van, we went past two dogs and owner. Sandra asked, ‘Boy or girl?’ Dog owner replied, ‘The black one is a boy. The sable one is a girl’. Sandra then asked: ‘what is that on the nose?’. Dog owner: ‘That’s a gentle leader. Otherwise they pull’. Sandra replied: ‘Arhh. OK. Bye’.”

This level of positive and two-way interactions between Sandra and community members continued in the final three intervention phase meetings. During Meeting nine, the handler explained that “there were four fleeting moments of conviviality: three were with people who were walking their dogs on the path. Sandra was walking Barney, and posed the first question ‘what type of dog is that?’. Each person stopped and answered.” In Meeting 10, Sandra had a coffee service transaction and encounters with other dog walkers. The handler summarised one such encounter: “Sandra identified/pointed out a King Charles Spaniel (her favourite dog). The couple and their dog came to order coffee whilst we were waiting. A two-way conversation between the dog owner and Sandra included discussion about: dogs name, colour, age, where does he sleep. Sandra was holding Barney’s lead (he was lying down). Dog owner asked what his name was and Sandra replied proudly, ‘Barney’. Finished with a photo of Sandra, dog and dog owner.” Similar encounters occurred in the final meeting of the Dog Buddies pilot, and Sandra’s service transaction illustrated that, over time, she had become known, which meant that there were more exchanges beyond the coffee purchase: “The barista made general conversation about the weather. Finished with a direct ‘enjoy your coffee’ to Sandra to which she responded, ‘Thank you’.”

In the post-program interview, Sandra spoke about the routine of the meetings: “It was good…we went to the lake, saw ducks. I would have a take away at the lake, had a coffee” – and described Barney’s characteristics: “he’s a good boy… he likes to talk, cry, and talk.” She also explained what he liked to eat, “Carrots and biscuits”; the instructions she gave Barney, and described giving him a treat, “He heeled… sit… sit… then put my hand, held a treat in my hand.” Sandra also recalled times that she had met people whilst out walking Barney: “We saw people, talked to the ladies about Barney, and said hello to their dogs… One was a boy, name was King [referring to the King Charles Spaniel], brown and white.”

Overall, Sandra was observed by the handler to enjoy the meetings, and over the course of the program gained confidence in handling Barney and interacting with other people. However, the handler noted that there were particular considerations for people such as Sandra to participate in the Dog Buddies program: “The program would only work if [like Barney] it was an easy dog to walk on lead who would not pull, as Sandra would not have the strength or cognition to correct the dog’s behavior.” To facilitate Sandra’s participation in the program, collaboration and communication between the program team and support staff was also required.

Sharon

Sharon, aged in her 20's, lives at home with her parents, and attends a day program five days a week. She receives 1:1 staff support three days a week, and group support (1:4 staff: client ratio) two days a week. Sharon’s overall CIQ-R score was 7, which is lower than the normative score of 23.24 when matched on age, gender and living location [Citation47]. Over the course of the program, Sharon had 15 Dog Buddies meetings. The initial five meetings, prior to her introduction to Barney, were characterised by either no encounters or unfulfilled encounters, not including those with the handler and support worker (see ).

Table 3. Summary of Sharon’s first five meetings (baseline Phase A) in the Dog Buddies program.

It is notable that Sharon did have several positive interactions with dogs during the fifth meeting in the baseline phase. This trend continued once Barney was introduced to Sharon in Meeting six, where the handler noticed a change in Sharon’s body language: “Sharon smiled when she saw Barney. She said hello to Barney and me. She took Barney’s lead and seemed to walk with more purpose, rather than lugging herself along.” This change in disposition compared to previous meetings was accompanied by increases in verbal interactions, as the handler noted Sharon was more engaged with her compared to the earlier interactions, and willingly learned how to ask Barney to do tricks – “sit, drop, roll over, shake paws, walk through the tunnel. Sharon liked trying these (once each) and Barney mostly complied.”

The increased social interactions continued for Meeting seven, where Sharon had a fleeting exchange with the owner of a Labrador. This was followed by a convivial encounter: “In an off-leash area, another dog came up to Sharon when she was giving Barney a treat (other dog wanted one too). I said to Sharon that we should ask the owner before we do. Sharon walked with me to the owner and politely asked, ‘Excuse me. I need to tell you something. I was giving Barney a treat and your dog wanted to have one too. Is she allowed to have a treat too?’. The person responded respectfully, ‘yes, that is fine. But watch your fingers’.” At the end of the meeting, Sharon tried more tricks with Barney and the handler noted “the support worker said Sharon had told her mother that Barney was a very clever dog.”

In her last meeting prior to the COVID-19 restrictions, what was notable for the handler was Sharon’s engagement with Barney, even when she was otherwise not socially engaging with others: “She conversed with Barney at the start and whenever we stopped. She is very gentle with him. When we sat for a rest, a boisterous dog jumped on the bench next to us. Barney also jumped up. Sharon smiled and patted the two dogs. She enjoyed this interaction with the dogs.” In addition to this socialising, “Sharon did some activities with Barney, going over small hills, calling him through the pipes and calling Barney to heel. She seemed very happy with herself, there was a sense of pride in what she had achieved, using commands and rewards to encourage Barney to complete each activity.”

Due to COVID-19 impacts, the ninth meeting took place 12 months later, and was characterised by three fleeting convivial exchanges with other people. The handler reflected at the end of the meeting, “Sharon appeared confident in walking Barney. When Barney sniffed, I pulled his lead to keep him walking. Sharon told me to 'be patient'.” This instruction was notable in that Sharon initiated the social contact, albeit based on her interactions with Barney. The next meetings were similar, comprising fleeting exchanges with passers-by and other dog owners, while – more importantly – demonstrating increasing dog handling skills. These are summarised in .

Table 4. Summary of Sharon’s last six meetings (intervention Phase B) in the Dog Buddies program.

Over the course of the Dog Buddies pilot, it was clear that Sharon felt comfortable interacting with Barney and the other dogs encountered on their walks; once she met Barney, her disposition and motivation to take part in the program reportedly improved. Sharon’s different levels of engagement with people and dogs was evident during her interview. When asked if she enjoyed the program, she replied, “I don’t know…” Sharon then started talking to Barney, “oh Barney, it’s alright baby… it’s alright.” The support worker added: “This morning I said, ‘oh, we’re going to walk Barney, that'll be good, won’t it?’, and she said ‘yes’, so she definitely likes it.” Sharon was asked what she thought about walking a dog, and whether it was different to walking without a dog, and she replied, “I think it’s a bit nicer when you walk a dog, yeah.” The support worker added: “It makes me feel happier, does it make you feel happier if a dog comes on the walk? Sharon replied ‘yeah’.”

In summary, the Dog Buddies program appeared to positively impact Sharon’s experience, but the handler noted there were particular considerations for people such as Sharon to participate in the program: “I think it was important for me to be ‘low key’ so the emphasis was on time with Barney, and I think Barney being calm and well behaved was also important. To start with, she was reluctant to look up at either Barney or me and kept to herself. In 2021, there were times when she was smiling to herself. She tended to direct her comments to Barney and other dogs, rather than to me, or other people. I think her confidence engaging with others increased over time as she sometimes asked people if she could pat their dog.” Sharon’s participation highlights the benefits that simple activities, such as walking and playing or doing tricks with a dog, built within dog-related support programs can bring to people with disabilities, holding potential to enhance their self-identity, confidence, and social interactions.

Wendy

Wendy, aged in her 30's, lives in shared supported accommodation with 24-h staff support. Wendy’s overall CIQ-R score was 16, which is lower than the normative score of 23.73 when matched on age, gender and living location [Citation47]. She participated in 10 meetings, but due to her cognitive communication abilities, Wendy did not take part in an interview. She can understand simple sentences when combined with gestures, and uses communication cards which have a line drawing or picture to request items and services in the community (for example, to order food and drink). summarises the initial five meetings, prior to her introduction to Barney.

Table 5. Summary of Wendy’s first five meetings (baseline Phase A) in the Dog Buddies program.

As can be seen in , Wendy had very little engagement with others – including the handler – in the baseline phase. Part of this may have been due to fatigue, as the handler noticed that her other activities on the same day had impacted on her energy levels. Once Barney was introduced in the meetings, Wendy had convivial social interactions directed at her, although these remained fleeting and she did not always respond. Wendy also responded positively to Barney. The handler reflected, “Wendy was very comfortable giving Barney treats at the table and having him sit next to her.” However, once they started to walk, Wendy required additional support: “Wendy held Barney’s lead and walked with him along the street, whilst I held her other hand to help with stability. At one time Barney pulled over to some grass to smell it, Wendy let out a squeal and let go of the leash. I explained that she needs to hold tight to the lead and not let go. Wendy was able to give a slight tug when Barney wandered slightly. By the end of the meeting, Wendy had enough confidence to take Barney into a store (with the storeowner’s permission).”

These moments of conviviality increased in the subsequent meetings, although Wendy’s fatigue levels meant that Meeting seven was restricted to 45 min’ duration. During this time, Wendy took Barney past a table of older people and the handler noted: “Members of the group made two or three comments about Barney to us in general. Wendy smiled.” During the following meeting, Wendy had one service transaction in a coffee shop, and she also “had made [at home prior to the meeting] some dog biscuits for Barney. She gave these to Barney along with some carrot. We went for a short walk along the shopping strip.” While this suggests Wendy was engaged with the Dog Buddies program, the support worker told the handler, “I don’t think Wendy is benefiting from Dog Buddies as she has grown up with two dogs and I also have a dog who Wendy goes out with on occasion.” The support worker added, “‘Her Mum signed her up for the program without thinking about it’.” Due to the escalating COVID-19 environment in Victoria leading to stay-at-home restrictions, this was unable to be followed up more fully. However, having dogs around her on a regular basis might explain Wendy’s familiarity with Barney.

Wendy ultimately had two meetings only following the easing of restrictions. Meeting nine comprised a service transaction where, “Wendy went to the counter to purchase an item… Wendy did not make eye contact with the salesperson, but said thank you at the end of the transaction.” The following week she had another service transaction and was acknowledged by name, “The shopkeeper had met Wendy last week. When paying for lunch, the shopkeeper asked Wendy, ‘what score would you give the sandwich from 1 to 10?’. Wendy responded ‘10’.” The intermittent encounter with the same shopkeeper provided a means to progress social inclusion, and created an opportunity to have this longer exchange.

Following the pilot of the program, it was unclear whether Wendy significantly benefited from her participation in Dog Buddies for several reasons. The handler described these: “Wendy had difficulty walking and did not have fine motor skills in her left hand so taking Barney’s lead and walking was difficult. Wendy can understand simple sentences but finds it difficult to vocalise – she tends to grunt and/or nod or shake her head. Being out with Barney was not a novelty for Wendy as she has grown up with two small dogs. I also think the 2021 program did not continue, mostly due to her support worker’s negative attitude to it.” This suggests several elements required for successful program participation, including: strategies to identify and determine the level of interest of the person to be involved in the program, when they cannot clearly express preference and thus need support from others to do so; physical strength and mobility of the participant; and perhaps, most importantly, personal perspectives of the support personnel working with people with cognitive communication issues and how their perspectives may influence decisions regarding whether or not the person engages in a specific activity or program.

James

James is different from the other participants not only because of his gender, but also due to the nature of his disabilities. James experienced an ABI, with resulting cortical blindness (low vision), unsteady gait (requiring use of a four-wheeled walking frame), and an expressive motor speech impairment (dysarthria). Aged in his 50's, James lives by himself in a unit within a cluster development, which offers 24-h onsite staff support. James’ overall CIQ-R score was 10, which is below the normative score of 20.59 when matched on age, gender and living location [Citation47]. He participated in 13 meetings, and outlines James’s first five meetings, prior to his introduction to Barney.

Table 6. Summary of James’ first five meetings (baseline Phase A) in the Dog Buddies program.

During the baseline phase, the handler noticed that James often was in community settings that included other people, but did not always engage with them socially. However, he was noted to have generally convivial interactions when he was out in the community. At Meeting six where James met Barney, the handler and dog had joined his usual group of friends. James had one service transaction, a fleeting exchange and a moment of conviviality around a gardening magazine that he had brought with him. The handler noted: “James asked a person in the group to tell him what to plant during this season. Another person joined in and James talked to them both about his veggie garden. James also listened to different conversations between others at the table. He would add information: e.g.,: 'I'm the gorgeous one' - this was a joke which the others laughed at.” This meeting was interesting, as James appeared to transition from a passive spectator to a more active participant in the group. The handler reflected, “James had a permanent smile on his face. He held on to Barney's lead whilst sitting at the café and walked well next to James and his walker on the street.” This level of connection continued in Meeting seven, where James had a service transaction where he was acknowledged by name by the waiter, and then later had a conversation with her. James also had four moments of conviviality with friends at the café.

During Meeting eight, these group discussions continued and James was increasingly active: “he added two jokes to the conversation and contributed to a discussion of recipes: James is seen as being knowledgeable about food as he is a good cook.” The handler also noted that, “James is happy when Barney arrives (smiles). He holds Barney’s lead as we walk, but if he pulls to sniff something, he is unsteady with his walker. James feeds Barney treats at the table. He rests his head on James’ lap whilst he eats his toastie. James is happy to have Barney’s lead under his chair leg whilst they sit.” Over the course of the recent meetings, it was clear that James was forming a close bond with Barney.

The next meeting, 10 months later due to COVID-19 restrictions, took place at a park where James had two moments of conviviality. One was with a “puppy raiser of dogs for children with disabilities. She brought her dog across to James and we talked about the dogs. She included both of us in the discussion. The young dog (9 months) was happy for James to reach down to touch her. Then the woman's grandson joined us and patted Barney. The woman then asked for directions to a nearby attraction. James gave her the driving instructions for how to get there.”

During Meetings 10 and 11, there were no encounters, due to no other people being around at the time, although “James was relaxed and chatty. He also appeared to love having Barney there, and enjoyed patting Barney as he laid down next to him whilst we sat.” In Meeting 12, the social interaction was limited to a service transaction only. The final meeting involved a service transaction where James was acknowledged by name, when the waiter brought coffees to the table. The handler reflected, “James loved having Barney sit beside him. James fed Barney treats, patted his head, held his lead.” Due to James’s other health issues which required him needing surgery, this was his final meeting in the Dog Buddies pilot.

When asked to explain why he wanted to be a part of the Dog Buddies program, James said, “I love having contact with dogs, both physically and emotionally. I feel so good after having contact with Barney, such a beautiful dog.” James reported he found both Barney and the handler caring and kind, and he especially liked Barney’s nature: “I’d love a dog like Barney, so beautiful, just his nature, he is really friendly and accepting … and obedient, he’s very well trained. I love all different types of dogs, especially the ones that are service dogs. Some places don’t allow you to have pet dogs though, but it’s been great that this café has let us have Barney here.” The support worker added, “Dog Buddies has made James’ day a lot brighter, when he has sort of had a downer of a day, so it’s been good, as he always looks forward to seeing Barney.” Indeed, it was only his impending surgery that ended James’ involvement with Dog Buddies: “There’s nothing negative, all positive, it’s all been good so far. I just wish I could have walked more with Barney.” Similarly, when asked whether he found anything difficult, James said, “Just the walking, Barney can walk faster than me” – something that is likely to be a result of his other health issues.

When asked if Dog Buddies had helped him meet new people, James said, “I think so, yes. When we went to the park, Barney would see other dogs, then I would be able to engage with other people with their dogs. So, yeah, meeting other people out in the community, even though they might not be lasting friendships, it’s just nice to chat to other people.” Finally, James was asked if Dog Buddies could benefit other people, and he said, “it would be especially great for people in rehab facilities, they’d benefit from it.” However, at the same time, he noted that not everyone might benefit from the program: “It would only be for people who like dogs and care about dogs that it would work with.”

Discussion

The United Nations CRPD espouses that people with disabilities should experience the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms and have the right to be active members of society [Citation1]. There continues however to be a range of barriers to social and community participation of people with disabilities, and these barriers are experienced with increased frequency for those who are born with or acquire cognitive disabilities [Citation7–8]. Internationally, governments invest billions of dollars annually in disability support [Citation2–3]; however, current evidence – including that generated in the baseline phase of the current study – indicates that this investment does not equate to increased social connection or inclusion of people with disabilities [Citation4].

This paper has reported Single-case experimental design and narrative methodologies investigating the impact a novel animal-assisted activity (AAA) program on the frequency and type of encounters of people with cognitive disabilities and community members. The Dog Buddies program harnessed existing evidence that dogs can be catalysts to social inclusion, and considered the continuum of social interactions that can build inclusive experiences for people with cognitive disabilities within community life [Citation27]. Dog Buddies also addressed the low levels of pet ownership for people with cognitive disabilities by enabling regular contact with a dog within community settings [Citation5,Citation30].

Facilitating social participation of people with disabilities

Social inclusion of people with disabilities is compounded by both issues related to the disability (e.g., cognitive-communication disorders) as well as external factors including the social, financial and attitudinal environment the person experiences [Citation1,Citation10–12]. Dog Buddies aimed to impact these multi-factorial issues, building on pilot work of Bould et al. [Citation30]. The findings provide evidence that the addition of a dog to a AAA program that enables routine community access offers a simple and effective means of influencing the frequency and depth of social interactions for people experiencing cognitive disabilities and the community members they engage with. The program piloted in the current study draws on research recommendations encouraging individualised goal setting with people with cognitive-communication disorders to build social interaction, with participants involved in the selection of where they went out into the community with the dog, and who supported them [Citation10]. The program was also found to enable greater social reciprocity and opportunities for connection of oneself with others through the dog’s presence, an important focus for people who may experience cognitive disabilities [Citation12,Citation19,Citation25].

For many study participants, at baseline, they had limited or no encounters with others. This finding supports previous research that co-presence of people in the community does not ensure interaction between them [Citation9,Citation13–16,Citation19]. Similar to research exploring the benefits of dogs for people with [Citation28–30] and without disabilities [Citation29,Citation31,Citation33], during the intervention phase, the dog acted as a catalyst for encounters. A range of community locations were selected by participants, and encounters in the intervention phase (when the dog was present) were found to be different to the baseline phase. Often intervention phase encounters were more convivial than at baseline and, for some participants, community service staff (e.g., café staff), and people present within shared local spaces (e.g., at parks) became more interactive with the person with disability when the dog was present. Following, there was also evidence in the current study to support previous findings that the presence of a dog increased a person’s confidence [Citation28,Citation30], in this case helping participants to initiate interactions with the handler’s dog, other dogs and their owners, and other people in the community.

Familiarity with people with disabilities, that is, knowing someone as an acquaintance, friend or colleague, has been demonstrated to increase social inclusion, especially if exposure is consistent over time [Citation4]. By planning for routine community outings with the dog, and recording the total number, and different types of encounters, the findings have addressed a limitation identified by Bould et al. [Citation30] in their study, and demonstrated the non-exclusive nature of encounters [Citation27]. Fleeting exchanges and service transactions provided moments of conviviality but, for one participant, a service transaction (during the baseline phase) was exclusionary in nature. The timing and frequency of encounters also varied, from being short (e.g., the one time a participant interacted with a community member), to occurring more intermittently over a longer period of time, and for some participants they were recognised or acknowledged by name. For all participants, these encounters provided a means to progress social participation, creating opportunities to have longer exchanges, which were more convivial in nature.

Learnings from the pilot of the Dog Buddies program

Given government investment in individualised funding to support community participation, there are some learnings from the pilot of the Dog Buddies program. The training provided to the handler ensured their support practices provided opportunities to progress the social inclusion of participants. This could however be extended to include further training and support on strategies pertinent to each individual. The handler also highlighted two important personal qualities that would be required of the dog handler; a relaxed manner and ensuring emphasis was on the time spent with the dog. The temperament of the handler’s dog was also important to the overall aim of the program, as the dog was willing to accept pats from strangers, and was friendly towards other people and dogs. In this study the dog sometimes pulled gently to sniff something, which caused unsteady gait for two participants. The dog size and suitability of the dog to walk well on a lead under the direction of a participant is also important, and might require other strategies, such as a double lead system to be employed. Finally, there are several elements required for successful ongoing participation in the program. These include the participant liking and wanting to spend time with a dog, and having an identified goal focused on social and community participation. In addition, and perhaps most importantly for people who require support for decision-making due to cognitive disabilities – the skills, motivation and priorities of support personnel to observe a person’s reactions within activities and facilitate participation in programs that are aligned with the person’s interests, as demonstrated by these reactions.

Study limitations

Although addressing methodological weaknesses identified by Bould et al. [Citation30] (research methodology, including recording the total number and different types of encounters), there remain some limitations with the present study. Firstly, the CIQ-R was only measured at one point in time, so this study did not ascertain whether the Dog Buddies program positively impacted their level of community integration. Nevertheless, there were other confounding variables that could have impacted participants scores on this measure (i.e., COVID restrictions). Further, as encounters are building blocks to becoming known and forming new friendships in local communities [Citation42], more data (over a longer period of time) would be required to make conclusions about the impact of Dog Buddies on their community integration. Another limitation is the A-B design, and a multiple baseline would have strengthened the study design [Citation38]. However, once the dog was introduced to the program, it had to be considered whether it was practical and ethical to take the dog away. The main criticism of A-B SCEDs is that passage of time can cause someone to make progress, and causality cannot be fully differentiated from coincidence [Citation38]. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, within the intervention period, each participant had an extended break of 10–12 months and this was unavoidable. Yet, when the meetings resumed, the level of encounters generally remained above the median data point of the baseline phase. As such, the effect of the intervention was unlikely to be due to passage of time, or coincidence.

Future research

For continued success, it will be important that both policy and practice has a strong commitment to evidence-based programs that build the social inclusion of people with disabilities. Promoting encounters with others in the community should be seen as an integral part of the disability services and the support workers they employ. Further research is required to inform both policy and practice in this area.

The current study evaluated the use of a pet dog within an AAA program called Dog Buddies, designed to promote encounters for people with various cognitive disabilities. This program was in contrast to previous work piloting use of an assistance animal with people with intellectual disability [Citation30]. Future research may include: (1) expansion of participant populations who trial Dog Buddies, beyond people with intellectual disability or acquired brain injury (e.g., people with other disabilities or older adults) to further ascertain who can benefit from the program, and understand any potential challenges for individuals, beyond those highlighted with one participant in the current study; (2) the role the person with disability takes within the human-animal interaction (e.g., evaluating the social inclusion offered via attendance at local community dog club); or (3) the nature of the interaction (e.g., routine attendance of a person with disability at a dog park, without necessarily having a dog present with them themselves).

Whilst the current study built on the limited evidence base and study design issues previously identified [Citation30], it further highlighted the mixed methods design required for participatory action research. When people experience cognitive disabilities that impact communication, traditional methods of quantitative survey design or qualitative interviewing might not be appropriate [Citation24]. This necessitates the use of inclusive methodologies, and the triangulation of data methods and sources to explore the meaning or influence of moments in individuals’ everyday lives. The narrative analysis [Citation53] and photography used in the current study were very useful for data triangulation. Other methods that may be considered in future research evaluating intervention programs aimed at enhancing social participation could include expanded photographic methodologies (e.g., via Photovoice) [Citation54], or community-based observational ethnography, as well as digital storytelling [Citation23–24]. These methods, whilst noted to require larger investments of research time and money [Citation24], align with the CRPD [Citation1]. Specifically, article 21 of the CRPD identifies the right for people with disability to express themselves – and this includes through research participation – ensuring the voice of the person may be heard even when expressive communication issues associated with cognitive disability may exist.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of the current study have added to the limited evidence base of effective programs that support people with cognitive disabilities to be more socially included in mainstream society. Dog Buddies is an example of a program which can support community participation for people with disabilities by creating opportunities to have social interactions with people without disabilities in the community, based around a shared interest in dogs. Dog Buddies has potential to be scaled up nationally, with varied populations who experience reduced social participation outcomes. The structured, replicable nature of this study did however call for a dog handler with research skills to complete the data collection instruments. For scalability and long-term viability, volunteers with a pet dog could be recruited to become ‘Dog Buddies’ to a person with disabilities in their local community. Whilst it is noted that close attention would be required to consider both the skills of the volunteer and their dog – as well as the participant to engage with the handling of a pet dog (e.g., holding the lead; walking or using a wheelchair whilst with the dog) – this approach could offer a cost-effective program to facilitate encounters with community members. It would also provide opportunities for longitudinal studies to explore whether extended human-animal encounters in the community can lead to stronger social connections and the formation of friendships; improve the quality of programs provided through funded disability supports; and/or impact the quality of life outcomes of both program participants and their key supporters as well as the general population.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (88.2 MB)Appendix_B_Interview_Schedule.docx

Download MS Word (26.1 KB)Appendix_A_Online_Survey.docx

Download MS Word (30.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Thanks are extended to the participants, their supporters, and to the handler and their dog for their involvement in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; 2006 [cited 2021 Jun 30]. Available from: http://www.un.org/disabilities.

- Commonwealth of Australia. National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013; [cited 2021 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2020C00392.

- United Kingdom Government. Care Act 2014; [cited 2021 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted.

- Thompson D, Fisher KR, Purcal C, et al. 2011. Community attitudes to people with disability: scoping project. Canberra (ACT, Australia): Australian Government Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Winkler D, Callaway L, Sloan S, et al. Everyday choice making: outcomes of young people with acquired brain injury after moving from residential aged care to community-based supported accommodation. Brain Impair. 2015;16(3):221–235.

- Clement T, Bigby C. Group homes for people with intellectual disabilities: Encouraging inclusion and participation. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2010.

- Jamwal R, Enticott J, Farnworth L, et al. The use of electronic assistive technology for social networking by people with disability living in shared supported accommodation. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(1):101–108.

- Migliorini C, Enticott J, Callaway L, et al. Community integration questionnaire: outcomes of people with traumatic brain injury and high support needs compared with multiple matched controls. Brain Inj. 2016;30(10):1201–1207.

- Sloan S, Callaway L, Winkler D, et al. Changes in care and support needs following community-based intervention for individuals with acquired brain injury. Brain Impair. 2009;10(3):295–306.

- Behn N, Marshall J, Togher L, et al. Setting and achieving individualized social communication goals for people with acquired brain injury (ABI) within a group treatment. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2019;54(5):828–840.

- Devi N. Supported decision-making and personal autonomy for persons with intellectual disabilities: Article 12 of the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41(4):792–806.

- Marrus N, Hall L. Intellectual disability and language disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;26(3):539–554.

- Bigby C, Bould E, Beadle-Brown J. Conundrums of supported living: the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2017;42(4):309–319.

- Clement T, Bigby C. Breaking out of a distinct social space: Reflections on supporting community participation for people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2009;22(3):264–275.

- Forrester-Jones R, Carpenter J, Coolen-Schrijner P, et al. The social networks of people with intellectual disabilities living in the community 12 years after resettlement from Long-Stay hospitals. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2006;19(4):285–295.

- Verdonschot MM, De Witte LP, Reichrath E, et al. Community participation of people with an intellectual disabilities: a review of empirical findings. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009;53(4):303–318.

- Winkler D, Unsworth C, Sloan S. Time use following a severe traumatic brain injury. J Occup Sci. 2005;12(2):69–81.

- Tate R, Wakim D, Genders M. A systematic review of the efficacy of community-based, leisure/social activity programmes for people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Impair. 2014;15(3):157–176.

- Douglas JM. Conceptualizing self and maintaining social connection following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2013;27(1):60–74.

- McLellan T, Bishop A, Mckinlay A. Community attitudes toward individuals with traumatic brain inj. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(4):705–710.

- Zambrino N, Hedderich I. Family members of adults with intellectual disability living in residential settings: roles and collaboration with professionals: a review of the literature. Inquiry. 2021;58:004695802199130.

- Winstanley J, Simpson G, Tate R, et al. Early indicators and contributors to psychological distress in relatives during rehabilitation following severe traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21(6):453–466.

- Lal S, Donnelly C, Shin J. Digital storytelling: an innovative tool for practice, education, and research. Occup Ther Health Care. 2015;29(1):54–62.

- Hand C, Stewart K, Rudman DL, et al. Applying the go-along method to enhance understandings of occupation in context. J Occup Sci. 2021;2021:1–14.

- Callaway L, Sloan S, Winkler DF. Maintaining and developing friendships following severe traumatic brain injury: Principles of occupational therapy practice. Aust Occ Ther J. 2005;52(3):257–260.

- Bigby C, Wiesel I. Mediating community participation: Practice of support workers in initiating, facilitating or disrupting encounters between people with and without intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2015;28(4):307–318.

- Wiesel I, Bigby C. Mainstream, inclusionary and convivial places: Locating encounter between people with and without intellectual disability. Geographic Rev. 2016;106(2):201–214.

- Hart LA, Hart BL, Bergin B. Socializing effects of service dogs for people with disabilities. Anthrozoös. 1987;1(1):41–44.

- Shyne A, Masciulli L, Faustino J, et al. Do service dogs encourage more social interactions between individuals with physical disabilities and nondisabled individuals than pet dogs? J Appl Anim Behav. 2012;5(1):16–24.

- Bould E, Bigby C, Bennett PC, et al. More people talk to you when you have a dog” – dogs as catalysts for community participation of people with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2018;63(10):833–841.

- McNicholas J, Collis G. Dogs as catalysts for social interactions: robustness of the effect. Br J Psychol. 2000;91(1):61–70.

- Wood L, Giles-Corti B, Bulsara M. The pet connection: pets as a conduit forsocial Capital? Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1159–1173.

- Wood L, Martin K, Christian H, et al. The pet factor – companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122085.

- Gallagher M, Muldoon O, Pettigrew J. An integrative review of social and occupational factors influencing health and wellbeing. Front Psychol. 2015;1(6):1281.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme. Quarterly reports – Dashboard; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/publications/quarterly-reports.

- Mavromaras K, Moskos M, Mahuteau S, et al. Evaluation of the NDIS. Final report. Australia: National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University; 2018.

- Wilson N, Stancliffe R, Gambin N, et al. A case study about the supported participation of older men with lifelong disability at australian community-based men’s sheds. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;40(4):330–341.

- Tate R, Rosenkoetter U, Wakim D, et al. The risk-of-Bias in N-of-1 trials (RoBiNT) scale: an expanded manual for the critical appraisal of Single-Case reports. Sydney: John Walsh Centre for Rehabilitation Research; 2015.

- Barlow D, Nock M, Hersen M. Single case experimental designs: strategies for studying behavior change (3rd ed). UK: Pearson; 2009.

- Kazdin AE. Single-case research designs (2nd ed.). New York (NY): Oxford Press; 2011.

- Tate R, Perdices M. Quantitative data analysis for single-case methods, between-groups designs, and instrument development. Brain Impair. 2018;19(1):1–3.

- Wiesel I, Bigby C, Carling-Jenkins R. Do you think I’m stupid?: urban encounters between people with and without intellectual disabilities. Urban Stud. 2013;50(12):2391–2406.

- Hatton C, Emerson E, Robertson J, et al. The adaptive behavior scale-residential and community (part I): towards the development of a short form. Res Dev Disabil. 2001;22(4):273–288.

- Wing L, Gould J. Systematic recording of behaviors and skills of retarded and psychotic children. J Autism Child Schizophr. 1978;8(1):79–97.

- Kelly G, Todd J, Simpson G, et al. The overt behaviour scale (OBS): a tool for measuring challenging behaviours following ABI in community setting. Brain Inj. 2006;20(3):307–319.

- Aman MG, Burrow WH, Wolford PL. The Aberrant behavior checklist-community: factor validity and effect of subject variables for adults in group homes. Am J Mental Retard. 1995;100(3):283–292.

- Callaway L, Winkler D, Tippett A, et al. The community integration questionnaire – revised: Australian normative data and measurement of electronic social networking. Aust Occup Ther J. 2016;63(3):143–153.

- Beadle-Brown J, Bigby C, Bould E. Observing practice leadership in intellectual disability services. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2015;59(12):1081–1093.

- Parker R, Vannest K, Davis J. Effect size in single case research: a review of nine non-overlap techniques. Behav Modif. 2011;35(4):303–322.

- Ma HH. An alternative method for quantitative synthesis of single subject researches: Percentage of data points exceeding the median. Behav Mod. 2006;30:598–617.

- Manolov R, Solanas A. Percentage of nonoverlapping corrected data. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1262–1271.

- Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA. Synthesizing single subject studies: Issues and applications. Behav Modif. 1998;22(3):221–242.

- Riessman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008.

- Povee K, Bishop BJ, Roberts LD. The use of photovoice with people with intellectual disabilities: reflections, challenges and opportunities. Disabil Soc. 2014;29(6):893–907.