Abstract

Divergent community and practitioner perceptions of Natural Flood Management (NFM) may impact wide-scale uptake, but are under-researched, especially in peri-urban environments. This mixed-methods study used picture- and scenario-based exercises, interviews and envisioning workshops in a post-industrial, peri-urban area of Greater Manchester, UK. Key differences were unpacked, with community members showing less confidence in NFM, and more confidence in grey infrastructure than professionals. Community confidence in installed NFM measures was, however, higher following a major storm event. Analysis suggests the value of demonstrating how NFM reduces flood risk, together with other co-benefits, through early engagement plus interpretation in the landscape. Uncertainty around effectiveness can be addressed using a learning-through-doing approach, enabled through field observation by community members. There is potential to engage more effectively around multifunctional benefits, framing NFM as green infrastructure that enhances biodiversity and recreation from the start. These findings hold significance for increasing uptake of NFM worldwide

Research Highlights

Compared to professionals working in the field, community members showed less confidence in Natural Flood Management (NFM) measures and more confidence in grey infrastructure.

Community members who experienced extreme weather events after NFM measures were installed felt more confidence in NFM than community members contacted in the first phase of research (soon after installation). This is a finding in contrast to existing literature, which suggested a likely decrease in confidence.

Community buy-in is a crucial aspect of the ongoing management and monitoring of NFM measures, particularly in the absence of suitable long-term revenue funding.

Challenges with uncertainty around the effectiveness of, and responsibility for, NFM measures require a learning-through-doing approach, which is enabled through field observation by engaged community members.

It is important to explore the multi-functional co-benefits of NFM in early engagement, both with partners and communities. Such holistic exploration of potential measures, no matter what the driver for change, increases the likelihood of both community buy-in and beneficial synergies.

There are opportunities to better promote social learning and understanding of how NFM reduces flood risk through the use of interpretation boards, citizen science, engagement in planning and visioning public events and social media, to make the co-benefits and functions of NFM measures more tangible.

1. Introduction

Recent extreme weather events across the world, such as the flood damage to properties in Germany and deaths of subway passengers in China in 2021, underscore the potential for flooding to damage homes and infrastructure, and to impact lives and livelihoods. This is predicted to worsen significantly with climate change, resulting in a higher intensity of heavy precipitation events, especially given an increasingly likely overshoot of the target of keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Citation2022).

To reduce risk to communities, homes and businesses, “hard” river and flood engineering (herein referred to as “grey infrastructure”) has traditionally been deployed in areas prone to flooding (Dadson et al. Citation2017; Gunnell et al. Citation2019). Grey infrastructure includes river and stream channelization, river embankments and built structures to hold or divert water, including dams and levees. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of reliance on such approaches to flood risk management have been questioned since the 1980s (Wharton and Gilvear Citation2007). Grey infrastructure has been shown to provide only localised solutions to flooding and may even compound flood risk further downstream (Iacob et al. Citation2014). In addition, over-confidence in grey infrastructure has the potential to encourage continued development on floodplains, thereby increasing the cost of flood damage when they fail (Iacob et al. Citation2014).

More recently, an integrated approach to flood risk management has developed across Europe, driven by the European Union (EU) Floods Directive (2007/60/EC). This promotes the use of non-structural measures that build community resilience to flooding, and works with the natural processes of rivers and their associated ecosystems to reduce flood risk (European Union Citation2007). Such nature-based solutions (NbS) represent a paradigm shift away from grey infrastructure (Raška et al. Citation2022).

Landscape-based non-structural measures are referred to broadly as natural flood management (NFM), an exemplar of the broader concept of NbS (Bark, Martin-Ortega, and Waylen Citation2021). This term encompasses a range of techniques that help attenuate, slow and hold water on the land, thereby reducing flood risk (Holstead et al. Citation2017). The goal is to restore a river’s hydrology, morphology, ecology and natural function throughout its catchment (Wharton and Gilvear Citation2007).

Understanding stakeholder perceptions of NFM and traditional grey infrastructure is important if diverse actors are to participate effectively in flood risk planning and decision-making (Anderson and Renaud Citation2021). Key themes to emerge from prior research into perceptions are explored in the next section. Recent research has gone some way towards filling this gap, yet still there is a lack of understanding of key differences between the perceptions of the community members and professionals working in the field. This could impact on uptake at scale, particularly if community perceptions diverge with those of delivery organisations.

The overarching aim of this research was to understand perceptions and attitudes towards NFM within a peri-urban setting, with the following research questions:

How do local community perceptions of NFM compare to those of professionals involved in NFM schemes?

What are the implications of these groups’ perceptions for the further uptake of NFM?

What are the factors that shape increased uptake of NFM (drivers, enablers and barriers)?

The study area lies within the post-industrial landscape between the urban areas of Wigan and Leigh and is identified as the “The Flashes” by the Carbon Landscape programme (depicted on the map in ). This large-scale restoration programme, in an area scarred by centuries of extraction of coal and peat resources, ran for 5.5 years up to June 2022, and was funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund (Tippett, Deas, and Haughton Citation2022). Multiple delivery organisations are active in NFM projects in the area, including Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) and public sector bodies. Two NFM projects are currently operating within the Carbon Landscape and form the study area of this research, located within the Lower Mersey Catchment at Low Hall Local Nature Reserve and Bickershaw Country Park. Formerly a coal mine which became derelict, the country park is adjacent to a small urban settlement that in recent years has witnessed a notable upsurge in new housing development. This peri-urban environment, once seen as a post-industrial wasteland, is now being reimagined as an attractive place to live and work, promoted as part of the Carbon Landscape (Tippett, Deas, and Haughton Citation2022).

2. Situating NFM research and stakeholder perceptions of management

In light of increased flood risk through climate change, there is an urgent need to consider new ways to reduce flood risk throughout catchments. The use of NFM can offer multiple potential co-benefits. These opportunities to realise multi-functional benefits leads to NFM being described as a “win-win” measure (Anderson et al. Citation2022). There remains within the literature, however, a level of uncertainty in relation to effectiveness and scalability (Holstead et al. Citation2017; Ellis, Anderson, and Brazier Citation2021). Whilst a number of co-benefits may arise from NFM, the literature is lacking systematic quantification of these (Dadson et al. Citation2017). This gap is exacerbated by alternative ways of framing effectiveness that arise from multiple co-benefits (Connelly et al. Citation2020).

The difficulty of assessing the effectiveness of an NFM approach across a catchment may be compounded by the large number of delivery organisations involved in catchment-based projects. This can result in a lack of communication, planning and coordination between these organisations (Dadson et al. Citation2017).

A lack of confidence in NFM options may be a significant barrier to uptake. Waylen et al. (Citation2018, 1085) have suggested that this can stem from “modernist expectations for control of nature.” Howgate and Kenyon (Citation2009) suggest that it may be due to a limited understanding of NFM, concerns over its effectiveness, or simply that the concept is new and goes against what may be traditionally thought of as flood protection. Anderson et al. (Citation2022) suggests that although NbS in Europe is generally well supported, in part due to its range of societal benefits and perceived “naturalness,” community members who are aware of being at-risk of natural disasters can show preference for grey infrastructure over NbS, or a combination of both.

Historically, community and public perceptions of NFM have been under-researched (Howgate and Kenyon Citation2009). A recent survey (Bark, Martin-Ortega, and Waylen Citation2021) found that although there was broad support amongst practitioners, disagreement about how to enable and implement NFM persisted, in particular around funding mechanisms and responsibility. Another recent survey (Wells et al. Citation2020) looked at practitioner and land manager perceptions in a catchment in Nottinghamshire. This study uncovered a concern amongst professionals that there may be over-confidence in the community about NFM, with possible over-reliance on such measures to remove flood risk altogether. Neither recent study surveyed community members. Whilst Anderson et al. (Citation2022) did survey community members, they did not survey professionals in the same study. There is a lack of systematic comparison of perceptions of NFM between professionals and community groups. Addressing this gap may offer insight into where efforts can be made in co-learning to ensure that public perceptions are taken into account, the principles of NFM are effectively communicated, and opportunities for more meaningful stakeholder participation are realised.

Earlier research explored public perceptions of aesthetics, such as a Holstead et al. (Citation2017) study that found members of the farming community perceived NFM as unsightly and unkempt. While Gregory and Davis’s (Citation1993) work concerned public perceptions of river aesthetics rather than flood management options, their results indicate a preference for more “natural-looking” rivers. Those characterised by channelized concrete banks were considered the least aesthetically pleasing. Despite this, participants showed a preference for rivers without woody material. Chin et al. (Citation2008) work, based in America on river aesthetics, also showed a negative response by members of the public and students to woody material in rivers. These findings have implications for the uptake of NFM, which may be hindered by community and local perceptions of “natural” beauty and aesthetics, particularly where NFM options aim to introduce dead wood back into the watercourse through leaky barriers. These findings are supported by D’Souza, Johnson, and Ives (Citation2021), whose study found that community preferences were led around a scheme’s perceived naturalness, neatness or greenness.

A research gap around perceptions of NFM is particularly pronounced in the peri-urban environment. Little research has been conducted in this environment, despite its importance for ecosystem services and the pressures on it for extending the built environment, as highlighted by Gunnell et al. (Citation2019). Studies of public perceptions of NFM in the UK to date have only been undertaken in rural settings in Scotland and the Scottish Borders, with the exception of Auster, Puttock, and Brazier (Citation2020), who undertook a nationwide survey of beaver reintroduction in the context of flood management. They found support to be higher amongst those who identified as having more knowledge of likely effects of the reintroduction.

Our research explored community and professional perceptions of, and attitudes towards, NFM options within a peri-urban environment between the conurbations of Wigan and Leigh, Greater Manchester, UK. The findings offer potential to increase the uptake of NFM in the landscape and improve its long-term management, through enhancing the effectiveness of stakeholder engagement. This is especially important in peri-urban areas, which lie in close proximity to dense populations.

3. Methods

Three groups participated in the study, which was undertaken in two phases. Phase one (2019) included community members located in the vicinity of NFM interventions and professionals with backgrounds in NFM working in the area. Phase two (2021) included only additional community members, located in the same study area (see ).

Table 1. Summary of research participant groups.

A mixed method approach was used, in line with other studies in the research field (Kenyon Citation2007; Holstead et al. Citation2017; Anderson et al. Citation2022). A picture- and scenario-based exercise was designed to explore participants’ perceptions of flood risk management options, with images and a brief verbal description of NFM and grey infrastructure options (with four images each for NFM and grey infrastructure chosen from professional publications, see Appendix, online supplementary materials). Participants were asked to score the images against criteria on a scale of 0–5, with 0 being the lowest and 5 being the highest score. The criteria were: level of confidence for flood management, importance for wildlife and perceived beauty.

Efforts were made to avoid bias in the picture study by selecting a range of images for both NFM and grey infrastructure. These included both established and recent examples of NFM, showing varying vegetation structures from bare ground (recently completed and seen as likely to be perceived as less attractive) to more developed habitats. Efforts were made to include some more attractive looking examples of grey infrastructure from the range of available images. All participants noted in the table above took part in the picture- and scenario-based exercise.

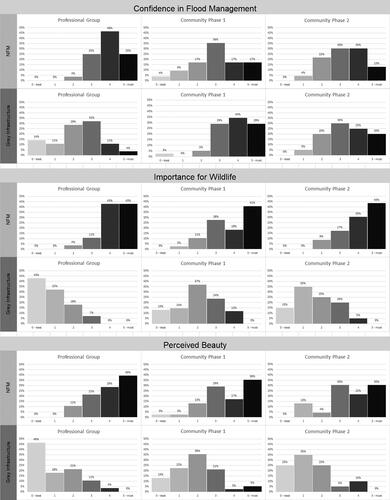

The combined results of the scores for NFM options and grey infrastructure options were converted to percentages to allow for comparison, as the number of participants from each group differed. The results from the responses to the pictures were collated in a series of bar charts, using the analytical method of comparing small multiples with standardised axes, to allow for comparison across different datasets and the visual recognition of patterns and key differences between them (Tufte Citation1990).

In phase one, additional data gathering was afforded by a series of in-depth semi-structured interviews with all seven of the professional participants and five of the community members. The interviews used open-ended prompts, to allow participants to elucidate key aspects of NFM from their perspective (see Appendix for the interview guide [online supplementary materials]). Interviews lasted 25–45 min in total and were audio recorded and transcribed. The picture exercise was given to both community members and professionals prior to the one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Given that there was a wide range of experience of NFM amongst the community members and between them and the professionals, introducing the images before the interviews was seen as a useful way to reduce any unevenness in understanding before the semi-structured interviews. Participants’ names and their employees/organisations have been anonymised.

Additionally, all phase one participants were asked to score their overall perceptions of NFM and grey infrastructure, based on the images they had seen, against the following criteria: climate change adaptation, ability to improve water quality and recreational value (key co-benefits of NFM that emerged from the literature review), and the need for ongoing maintenance, which was raised as a key issue in the literature.

Phase two was conducted during COVID-19 lockdown (Jan–March, 2021). This second phase made it possible to discuss NFM schemes nearly two months after an extreme storm even, Storm Christoph, in January 2021. Named by the UK Met Office on 18 January 2021, this storm brought a convective rainstorm and severe flooding to the UK including the study area (Ambiental Citation2021).

A digital survey tool (Mentimeter) was used to gather data during online meetings, including scoring in response to the picture- and scenario-based exercise (in this case using a composite of images from the original exercise due to the changed format of the meetings) and to gather key words to produce word clouds. Participants were not interviewed on a one-to-one basis, but supplementary qualitative data was gathered through the use of Ketso, a visual, tactile tool for concept mapping. This tool has been deployed in recent research into NFM as a “structured method to engage in dialogue and co-create knowledge across disciplines and practitioner groups” (Wingfield et al. Citation2021, 6241). In our research, it was adapted to be used remotely, with packs of individual Ketso kits, plus printed maps of the area, posted to individuals. Images of the ideas developed using the kits were photographed and shared online during the workshops using a digital noticeboard (Padlet).

Thematic analysis was utilised to look for patterns and emerging themes within the qualitative data, using a digital Ketso tool developed to analyse participatory data (Wengel, McIntosh, and Cockburn-Wootten Citation2019). Direct quotations selected from the interview transcripts and outputs from online meetings were used to add additional depth to the analysis.

4. Survey results

The following sections provide a comparison of perceptions between community and professional groups from the picture- and scenario-based exercises.

4.1. Confidence, wildlife and aesthetics

shows the combined charts for the scoring from these exercises. The results showed that confidence in NFM for flood risk management was notably higher in the professional group than either community group, with 71% scoring 4 and 5 (highest score) and with 0% scoring 0 (none) or 1 (lowest) for this parameter. The professional group also had a strikingly higher degree of lack of confidence in grey infrastructure options, with 14% having “no confidence” in grey infrastructure, compared to 3% in the phase one community group and 0% in the phase two community group.

Comparing the degree of confidence in NFM between the two community groups, phase one and phase two (Bickershaw) shows a marked difference between the groups. The phase two group had experienced an extreme rainfall event after the NFM measures were installed near their houses. Within this group, 43% selected options expressing higher confidence at 4 or 5, an increase from phase one at 34%. This is a particularly notable finding as this group included a mix of participants, not all of whom had been actively engaged in the work of the host organisation, albeit with a small sample.

With regards to perceptions of importance for wildlife, within the professional group there was a starkly contrasting pattern between NMF and grey infrastructure. In this category, 86% of the professionals selected 4 or 5 for the NFM options, in contrast to grey infrastructure for which 75% selected 0 or 1. Within both community groups (phase one and two), importance for wildlife scored more highly for NFM compared to grey infrastructure. This high scoring of NFM’s importance for wildlife, however, was less pronounced than that of the professional group.

Within all of the groups there was an overall pattern that NFM was perceived as more beautiful than grey infrastructure, though the difference between the two options was more striking within the professional group.

4.2. Multi-functionality and further co-benefits

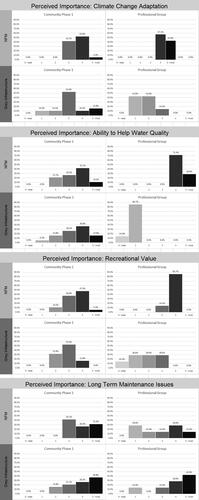

The following section explores perceptions of additional benefits and possible concerns, which were explored in phase one of the research. Results are summarised in .

Figure 3. Graphical representation of responses to questions around additional values of flood management options (community and professional groups Phase 1).

In the professional group, 100% of respondents scored the value of NFM for climate change adaptation as either 4 or 5, compared to 86% scoring grey infrastructure at 1 and 2. The professional group rated the importance of NFM for climate change adaptation as considerably higher than the community group, with 58% of the community group selecting 4 and 5.

Scores for water quality in the professional group also differed greatly between NFM and grey infrastructure, with importance for water quality being scored 4 or 5 by 100% of participants for NFM, compared to grey infrastructure, where 100% of participants selected a combination of 0 and 1. Scores for the community group were more evenly distributed across the scale for both NFM and grey infrastructure.

Within the professional group, recreation value scored considerably more highly for NFM options, with a strikingly high 86% of participants selecting 4, in comparison to grey infrastructure, with a total of 86% of the group equally distributed across the scores of 1, 2 and 3. The professional group rated the recreation value of NFM more highly than the community group, with only 53% of the community group rating it at 4 or 5.

Analysis of the word clouds developed from the phase two participants’ reactions to the options highlighted issues around a sense of whether sites felt well managed or neglected, which was linked to concerns around access. The descriptor “muddy” was commonly noted for the NFM options, and “wellington boots” were also mentioned, in contrast to a high degree of mention of the term “managed” for grey infrastructure. The issue of mud and difficulty in walking near some of the NFM measures was also discussed in the workshops as a barrier for many community members accessing and making the most of the sites. There was a sense expressed that this had been made worse by the NFM measures.

The professional group scored the need for ongoing maintenance higher for grey infrastructure, with 4 and 5 selected by 72%; compared to NFM that received a score of 4 or 5 from 43%. The community group scored ongoing maintenance issues highly for both grey infrastructure and NFM, but thought ongoing maintenance is considerably more of an issue for natural options than did those who are involved in the delivery of such measures.

5. Interview results

Post hoc thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews (undertaken with members of the professional and phase one community groups) revealed multiple themes that can be seen as broader, contextual shaping factors influencing the potential for, and uptake of, NFM. These emergent themes are used to structure the following analysis of the qualitative data gathered in the research.

5.1. Drive to enhance wildlife and biodiversity

The idea that NFM should be led by a drive for biodiversity gains and restoration of functioning ecosystems, rather than being those being framed as a co-benefit to this approach, was voiced by four out of the seven professional interviewees. These four respondents shared the view that flood risk reduction was an “added benefit” to the work their organisations and other land managers were already undertaking in wetland protection, restoration and creation.

NFM is not the main driver for me and from a [government agency] perspective…The driver is biodiversity, habitats and species; the broader natural capital benefits accrue from that. (Professional Group: government agency 2)

A similar narrative of the paramount importance of benefits for wildlife as a driver for action was also evident in the phase one community group. This could be attributed to the engagement undertaken by delivery partners, which primarily focussed on opportunities for wildlife and habitat improvement rather than flood risk reduction.

5.2. Stakeholder engagement and partnership

Working in partnership with community members and other stakeholders was a strong theme. Early community engagement was regarded by all members of the professional group as essential. It was seen to be important to allow “communities to feel they are contributing and connected to the outcome” and to “understand what communities think and not just rely on modelling” (Professional Group: government agency 2). Professional group: NGO 2 highlighted issues around engaging with the “very local people,” suggesting that although these communities would perhaps be the most influenced by the project, they were a “difficult to reach community that had more to worry about in their lives.” Several barriers to effective stakeholder engagement were presented during the interviews, including the number of separate groups and organisations active in the area, and difficulties in sharing knowledge effectively between them. These difficulties were exacerbated by funding restrictions and a lack of staff and time resource.

All individuals in community group phase one were aware of the term NFM. However, none felt they had the level of knowledge required to talk in depth about options and any potential benefits. It was considered that although there had been some media coverage around NFM, more could be done to educate about the issues of flooding and options to manage it.

Three of the five interviewees suggested that they would like to have more opportunities for engagement about specific NFM projects, with one member of the community group stating: “We would need to be sat down as a community and be consulted with, so we understand what could go wrong and how it would work.” Similarly, another community group member suggested that increased and earlier engagement of local interest groups and the communities was important “especially if they are affected by the works or by the flooding.”

5.3. Experience of flooding

Experience of flooding was considered by six of the seven professional group members as an important driver for public awareness, and one that could shift perceptions and levels of confidence in NFM. This was expressed by Professional Group: government agency 2 who noted that, “When people have experienced flooding near their house, they do not necessarily care for a natural solution, they just want a solution, and a solution that is going to work.”

The timing and frequency of flooding events was also considered important in raising people’s awareness of different flood management options, underscored by professional group: NGO 3 in relation to the residential areas around Low Hall Nature Reserve: “It’s around experience, and it’s not happened for a while around here. There needs to be ongoing work around people’s awareness of flooding, and what to do if there is a flooding event.”

Similar to the professional group, experience of flooding was a recurring theme with community members. However, unlike the professional group, the community members considered that those who had experienced flooding would be more likely to want NFM options. A member of the community group suggested that it was a fear of flooding that “kick-starts the community work” and that experience of a flood event will increase a community’s involvement in the planning and maintenance of NFM options. Without direct experience and risk of flooding, it was considered that “people don’t have time to think about these things” and “it’s probably low down on their agenda” (Community group: Wigan).

5.4. Evidence and communication

Within the professional group there appeared to be a mix of opinions with regard to the evidence base for NFM. Some respondents considered the approach “to be backed by science more than before”; in contrast, there were also concerns over the measurability of the wider benefits of the projects, “There is a difficulty proving if what has been done has benefits. The logic says it does but it’s difficult to actually measure” (Professional Group: government agency 3).

Several of the professional participants raised ideas about how this evidence was communicated to the wider public and decision-makers, suggesting a need to “communicate the added value, the opportunities and the costs” (Professional Group: government agency 2). However, there were concerns by others that the premise of NFM had been oversold by delivery organisations and politicians, and that it may be considered a “panacea” to flooding and other issues. Within the group, several individuals suggested that communication should instead focus on the clear message that NFM is only part of the solution to flooding.

NFM was conceptualised by a member of the Bickershaw community as a way of utilising natural resources in a visually pleasing way that has minimal impact on the landscape, “keeping the landscape intact and as natural as possible.” Members of the community group linked hard landscaping to increased water run-off and flooding, for example, “there is too much concrete and tarmac these days and nowhere for the water to go other than down the street and into the drain and rivers” (Community group: Wigan 2).

5.5. Funding, bureaucracy and processes

Interesting differences emerged in relation to capital projects for building NFM measures and revenue funding for their future maintenance. Funding was considered to be both an enabler and barrier by the professional group. Overall, the availability of capital funding for NFM in the area appears to have increased, driven in part by new funding streams. However, access to funding was still seen to be restricted by overly complex bureaucracy. In addition, for private landowners, restrictions to agri-environment funding and reduced availability of financial incentives were considered to be a barrier to engagement and NFM uptake.

A lack of revenue funding mechanisms for maintaining NFMs was considered to be a barrier to uptake, with revenue payments considered “generally something like gold dust” (Professional Group: NGO 2). This was seen to impact the ongoing efficacy of projects. In addition, reduced funding cycles were seen to drive “short-term solutions and short-term gains” (Professional Group: government agency 1), and were not considered conducive to the long-term environmental changes required. A suggested remedy for this shortfall in long-term revenue was payments for ecosystem services. However, the precise mechanism for this remained unclear, with concerns that the science behind this approach was “too difficult and expensive to work out” and would be unlikely to “form the basis of payments in the next 20–30 years” (Professional Group: land consultant).

5.6. Land availability and ownership

Patterns of land ownership and control were considered a barrier to the uptake of NFM options, particularly on privately owned land, where multiple individuals may need to be engaged with, for example:

In terms of getting the benefits, we need to engage with private landowners and that’s always been one of our biggest challenges; finding land, and landowner permission and interest. (Professional Group: NGO 2)

Other barriers to uptake include a lack of land availability and pressures from development. Pressures on land use within the peri-urban environment were emphasised by both the local environment NGO 1 and 2, suggesting a “loss of green space, and the pressure to build more housing in areas that could be used for NFM” (Professional Group: NGO 2). However, a more optimistic view was held by local environment NGO 3 who, within the context of the whole Mersey Catchment, suggested that there was “always somewhere we can work.”

6. Discussion

The aim of this research was to understand current perceptions and attitudes towards NFM. The context of the research was peri-urban, a hitherto under-researched area for NFM. This discussion returns to the research questions, looking at differences between community and professional perceptions of NFM, the impacts of these perceptions on wider uptake and then developing lessons for the future, revisiting the drivers, enablers and barriers explored in the analysis of “shaping factors” above. Five key themes emerged in the analysis, and these are used to structure the discussion below.

6.1. Confidence and the need for more effective communication around the way NFM works

Analysis of data gathered to answer the first research question, around differences in perception between community and professional groups, showed a striking difference in the level of confidence in NFM options, with the community groups showing less confidence in NFM compared to the professionals. The results also suggest that the community groups’ levels of confidence in grey infrastructure was similar to that of their level of confidence in NFM, whereas the professionals had considerably less confidence in grey infrastructure. This finding is echoed in the wider literature, such as in a survey conducted by Bark, Martin-Ortega, and Waylen (Citation2021), which found that confidence in, and support for, NFM measures was relatively higher amongst public sector and academic respondents involved in flood risk management than landowners and managers. Recent research by D’Souza, Johnson, and Ives (Citation2021) found that local communities are concerned about the effectiveness of NFM techniques when compared to more traditional flood defence measures, echoing earlier work by Howgate and Kenyon (Citation2009) and Waylen et al. (Citation2018).

A key finding from our research, however, was a difference in community perceptions in phase two of the research, when the community group showed a higher level of confidence in NFM than the community group in phase one. In the second phase, the community members included a mix of those who had been actively engaged with the recent changes on the site, and those who were relatively new to them. We had assumed that the inclusion of these with only recent involvement was likely to make the respondents less confident in NFM than the community group in phase one. The relatively high level of confidence that was shown could derive in part from the fact that these workshops were held shortly after Storm Christoph, which had acted well to demonstrate the value of the NFM interventions.

In contrast to this increased awareness of the possible value of NFM following Storm Christoph, the professional group in our study had demonstrated an expectation that the public would show more preference for grey infrastructure after they had experienced flooding events. Such preference for grey infrastructure following direct experience of flooding was found in both Werritty et al.’s (Citation2007) Scottish study and in Buchecker, Ogasa, and Maidl’s (Citation2016, 309) Swiss Alpine study, which found that “after the flood event, local populations in both valleys mostly favoured traditional measures of hazard control.” Although in this Swiss study there was a higher level of support for hard engineering solutions, they found that support for non-structural measures also remained high.

Our research throws a new light on the question of confidence and experience of flooding, suggesting the value of clearly demonstrating the mechanisms by which NFM reduces risk. In the case of the experience of Storm Christoph, images showing the NFM measures absorbing and spreading water on the landscape were shared on social media, possibly contributing to raising awareness of how the measures worked, as they gave experiential evidence of their effectiveness.

After carrying out the picture-scoring exercise in the phase two workshops, we showed these images of the measures in action during Storm Christoph. We also showed aerial photographs of the area before and after the NFM measures. We then discussed the way in which the measures operate across the landscape with participants. This led to an in-depth dialogue around of the need for more, and better, communication about the way that NFM functions. The potential value of such communication was echoed by both the newly and previously engaged community members. Even the relatively well-informed participants said they found it useful and inspiring to see such images during the workshop.

Discussing NbS for flood management, Anderson and Renaud (Citation2021) highlight that a lack of understanding about, and negative perceptions of, green measures can limit their uptake. They stress the need to both collect and demonstrate evidence of their value and functioning. A key idea to emerge in our research was the need for more interpretation in the landscape itself, to extend the reach and longevity of the communication. Participants reflected that whilst the images of the NFM in action shared on social media would reach some audiences, it would not reach all of those who use the local landscape. An idea was developed in the visioning workshops for interpretation boards that show the wider context of NFM in the landscape, which is not always visible from the ground. This could include aerial overviews of “before” and “after” pictures of NFM installations, photographs of NFM features before and during an extreme event, and information on the expected benefits and value for flood management and wildlife.

There are possible problems, such as vandalism, and finding the resources for design and installation. The boards would ideally be developed with input from community members, so that they were locally tailored and local people are more likely to feel ownership of them. As noted by Anderson et al. (Citation2022), consideration also needs to be given to including caveats as to the limits of such measures, to prevent reputational damage in the face of future flooding events.

Such interpretation boards, which make visible both the nature of the changes made and the way they work in storm events, could make the invisible more tangible. Provision of information through interpretation boards can be complemented by social media feeds of the measures in action and information in community newsletters. Anderson and Renaud (Citation2021) reflect on the value of finding ways to make the benefits of NFM more tangible to community members, and discuss the importance of multiple channels of communication, including active, two-way dialogue. Active engagement is essential to deepen knowledge, trust and learning over time. This can include visioning and engagement in planning the future of the area, public art and activities celebrating the water environment, and citizen science that collectively gathers data about the landscape. Hein et al. (Citation2016) highlight the value of public events and education for increasing public awareness of the value of flood plain restoration and public support for such measures in the face of competing societal demands.

Careful consideration of multiple channels of communication could effect changes in perception about NFM, without relying on participants to actually experience extreme flood events and NFM in action. This could also fruitfully be extended to smaller scale sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) to increase awareness of the purpose and functioning of such features. This may easily be overlooked in an urban environment, where the function of SuDS is not generally obvious to the casual observer, and they may be perceived as unkempt. Interpretation can highlight multi-functional benefits, showing the potential for water retention during extreme weather as well as the value for local wildlife.

6.2. Untidiness, mud and the need to carefully consider access and signposting

In our research, both the community groups and the professionals actively discussed leaky barriers as a positive element of NFM. This finding lies in comparison to that of D’Souza, Johnson, and Ives (Citation2021) whose study highlighted a key challenge that perceived untidiness could be a barrier to uptake. This in turn echoes earlier studies that discussed what might be seen as “unkempt” elements, as in the public preference for rivers free from woody material (Chin et al. Citation2008).

Perceptions of how easy a site is to access for recreation purposes are linked to a sense of whether it is seen as being well managed or not. Within the literature, recreation and amenity are considered as co-benefits of NFM (Posthumus et al. Citation2010). The phase one community group scored the importance of NFM for recreational opportunities as lower than the professional group. Concern was also expressed in the phase two community group around loss of access to sites from increased muddiness. This was perceived to have been intensified by the NFM measures, despite a sense of their increased aesthetic value.

There are opportunities to improve the recreational and amenity value of an area through NFM. In order to realise these benefits, however, both delivery agencies and community members must be aware of the potential and actively consider how to increase it. For instance, discussing future improvements to the site in Bickershaw in the phase two workshops, community members emphasised the need to consider access routes and muddy areas. They suggested providing information at key points in the landscape about the value of the NFM in order to explain why changes were being made. Delivery organisations need to design interventions with access and signposting in mind, and engagement around NFM would benefit from discussion of recreation in the planning stages.

Such consideration of recreation and information provision in the landscape can include thinking about how to boost knowledge and awareness of what makes the area special. The value of such engagement was shown in phase two of this research, which sat within a process of developing a National Nature Reserve. It included exploring the heritage and wildlife of the site with community groups. There were comments in the feedback around how this had helped several of the participants to enjoy their local area more: “Really informative. Has made me realise how much more I’m missing on my walks.” Early engagement and communication around recreation and multi-functional benefits is likely to result in more effective and extensive community use of the facilities.

6.3. Consideration of co-benefits in engagement, regardless of the driver for change

Kenyon’s (Citation2007) and Howgate and Kenyon (Citation2009) studies showed that community preference for NFM was influenced in part by additional perceived co-benefits. Anderson and Renaud’s Citation2021 review of public acceptance of NbS highlighted that “awareness and understanding of the measure” is even more important for acceptance of NFM than for grey infrastructure measures.

The differences in perceptions around access and recreational value amongst professionals and community groups in our study points to the need for a holistic consideration of how to maximise the value of co-benefits. In contrast, the link between NFM and importance for wildlife and biodiversity was a prominent theme to emerge in the analysis for both the professional and community groups, highlighted in the picture exercise, word cloud and the semi-structured interviews. These findings are supported by Kenyon’s (Citation2007) study, which suggested a preference from the public for NFM over grey infrastructure options for their wildlife value, especially from wetland creation and tree planting.

The importance of NFM options for water quality and climate change adaptation was rated lower by the community group than the professional group in phase one of the research. Engagement with communities around the NFM projects appear to have been influenced by the delivery organisations’ underlying delivery objectives; for example, much of the community work around the Bickershaw NFM project, completed by the Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester and North Merseyside, focussed on the wildlife and habitat creation element of the works, rather than water attenuation, reduced flood risk to local communities and water quality benefits.

In addition, community members are less likely to have direct experience of the complex trade-offs involved in managing for flood risk, climate change and water quality, which may go some way towards explaining these differences in perceptions. Experts are likely to have access to more detailed information than lay people, as well as more extensive knowledge of similar schemes in operation elsewhere. Lorenzoni, Nicholson-Cole, and Whitmarsh (Citation2007) suggest that although in the context of climate change there is widespread general awareness in England, knowledge of the causes, outcomes and possible solutions is less well-understood. This may explain the lack of connection made by participants between NFM and its potential for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Differences in perception could also be due to professionals being potentially subject to “group think,” or optimism bias encouraged by following government policy, which currently favours NFM. Community members may be wary of being at the front line of new policy experiments in flood risk, especially as their houses and neighbourhoods are in the line of damage if the hoped-for reduction in risk proves to be over-estimated. The lack of available evidence, and difficulty in measuring the co-benefits of NFM, was seen by individuals in the professional group as being a possible barrier to wide-scale uptake. This view is sustained by multiple studies including Howgate and Kenyon (Citation2009), Holstead et al. (Citation2017) and Dadson et al. (Citation2017).

The relationships between NFM, climate change and water quality are not easily observable, and the effects remain somewhat intangible, unlike, for example, changes in wildlife, which may be more easily observed and understood. A more holistic approach could be encouraged by communicating about NFM as a form of green infrastructure, an integrated approach to assembling natural assets with a high degree of connectivity across the landscape into a functional whole to give “multi-functional social, ecological and economic benefits” (Mell Citation2019, 19). In addition to considering these holistic benefits, there is an opportunity to improve engagement by communicating about the multiple possible co-benefits of NFM, no matter what the key driver/s are for the delivery organisation.

6.4. Engagement and partnership development as an ongoing and overlapping process

Community cooperation, particularly by those members that host NFM projects, is essential for wider successful uptake and implementation. Cooperation is influenced by the trust a community places in the delivery organisation, as well as their confidence in the proposed option (Howgate and Kenyon Citation2009). Early engagement with local communities is important to build trust, as well as interest in and ownership of natural resource management measures (Mostert et al. Citation2007; Tseng and Penning-Rowsell Citation2012). Building trust is an ongoing process, and at any stage in an engagement process, signposting links to earlier engagement that has happened in the area builds further trust and a sense that participants’ ideas are being listened to (Tippett and How Citation2020).

Within the Carbon Landscape, community buy-in and project legacy is a crucial aspect of the ongoing management and monitoring of the sites, much of which is completed with the help and support of volunteer groups, including through practical conservation activities, citizen science and informal “eyes on the ground” and communication between community members using the site and project officers. However, there remain challenges to engagement with “hard-to-reach” communities who may lack interest, time, finance or perception of adequate knowledge to actively participate in environmental projects. A key element of the process in phase two was to include skills development as part of the engagement. This aimed to make it more attractive for community members to commit their time to the project, and to build capacity in the area for long-term management (How and Tippett Citation2021). Exploring the impacts of including skills development in engagement could go some way towards addressing a challenge identified by Ellis, Anderson, and Brazier (Citation2021, 829) as little explored in the literature, namely “maintaining participant engagement beyond the design phase of NFM.”

Current UK policy on flood risk management can be considered a driver for NFM techniques. Despite the availability of new sources of capital funding, which was considered a major driver within the area, a lack of funding for community engagement, partnership working, and co-ordination was identified as a key barrier. This finding is supported by Waylen et al. (Citation2018), who suggest that NFM requires more varying expenditure over time than grey infrastructure. This points to the need to think of new ways to work in partnership and deliver multiple outcomes and benefits to secure funding. Payment for co-benefits from NFM was seen by respondents in Bark, Martin-Ortega, and Waylen’s (Citation2021) survey as a possible way to fund measures, promote efficiencies and encourage more holistic planning from the outset.

Recognition of the value of early engagement with the community around multi-functionality points to the value of also actively exploring and discussing potential co-benefits amongst partners. This could, in turn, help identify areas for potential alignment of objectives. Partners have different objectives and drivers for action, and will need to work to varying timescales relevant to their reporting and funding cycles. In order for them to work together effectively, there is a need to look for areas of alignment so that joint activities can help partners achieve their own objectives as well as work towards mutual benefit. This requires clarifying what the objectives of each are, looking for areas of commonality, and seeking projects and actions that can be pursued together that help meet those common objectives.

6.5. Learning-through-doing as fundamental to the process

Concerns over uncertainty were highlighted by the Professional Group: agri-environment consultant in this study, in particular over the potential liability to landowners in the case of failure and flood damage. Holstead et al. (Citation2017) propose that there is a level of fear over the uncertainty of the effects of NFM options, which acts as a barrier to uptake. Participants in their study also expressed apprehension should NFM measures, such as leaky barriers, fail and worsen flooding.

The Bickershaw “Slow the Flow” project can be seen as an example of adaptive management, where initial trials: meandering a section of concrete trapezoidal channel (part of the existing hard engineered drainage system across the site), and creating bunds to hold water back on the coal shale; allowed for a series of adjustments in response to learning. In this former mine site, there is a hidden set of underground pipes and legacy hard engineering. As the obvious concrete has been removed, buried pipes have been discovered through observation of unexpected water flows and effects of the new NFM systems, which led to adjusting the leaky dams in response to this field experience.

Oisalu (Citation2022) discusses the importance of learning by doing and starting with small-scale demonstration projects, especially in visible public spaces such as school grounds, as a means to raise awareness and support for NbS approaches to water management. This was seen as especially important in the Baltic States, where there is little experience of such measures to date. Complex interacting variables, such as the need to consider safety from areas of standing water that might freeze and pose a danger to pedestrians, attract mosquitos in hot weather (Oisalu Citation2022) or cause other unintended consequences, such as spreading invasive species through reconnecting previously isolated side-arms of water (Hein et al. Citation2016), also requires a learning approach across sectors and areas of expertise.

Oisalu’s (Citation2022) report also makes the point that any new measures will be implemented in a context of a changing climate – so will inherently require a learning approach to take into account new local conditions, such as the need for plants that will grow in hotter conditions. A related issue around learning and perceptions was experienced in Bickershaw, namely that water-related damage from flooding events, which could be attributed to a changing environment, was seen instead by local anglers as arising from the new NFM measures. Ways to set planned changes in the context of future climatic change needs careful consideration in communication plans.

Natural measures have greater scope than engineered measures to be adjusted in response to changing conditions and experience, as they are (literally) not cast in concrete. Such ability to adjust measures potentially offers a higher adaptive capacity in response to the variable impacts of climate change (Iacob et al. Citation2014), and demonstrates a way to work within uncertainty when making changes. It requires ongoing observation and management, especially in the early stages of project design and delivery. In Bickershaw this is facilitated by communication between community members, volunteers and the project team. Learning by doing has thus been strengthened with a blending of knowledge from practitioners and lay people.

6.6. Limitations and further research

Our research suggests fruitful areas for further exploration. This would benefit from research with a wider sample, as a limitation of the current study was the small number of individuals who took part in the semi-structured interviews. This was in part due to difficulties engaging with community group members, several of whom when contacted did not wish to be interviewed due to a lack of time, interest or perceived knowledge of the subject area. As a result of the limited sample, there may be some positive bias in the data, as community members in the first phase were already engaged with the Carbon Landscape through their involvement in community organisations. The aim of the workshops in the second phase had been to engage a wider section of the community around the Bickershaw site than those who had normally been engaged. This was achieved to an extent, with a few people recruited to the visioning workshops via social media, as opposed to their earlier interactions with the project.

It was not possible to re-contact the members of the community group that were surveyed in phase one after the storm event (as they were contacted through existing face-to-face meetings rendered impossible by lockdown). It would be useful to do picture- and scenario-based exercises with the same set of community members both before and after a storm event, as a test of shifts in perception. A further limit was that it was not possible to reproduce the full extent of the individual, more detailed picture- and scenario-based exercises with the community group in phase two, as the exercises were conducted as part of a broader visioning process and through online workshops.

A more general limitation is that using photographs to elicit responses in surveys gives a potential for perceptions to be influenced by issues to do with the nature and quality of the photographs, such as lighting and weather (Poledniková and Galia Citation2021). In this study, images were chosen from existing professional documents, with an attempt to minimise bias towards either grey infrastructure or NFM measures, including showing early-stage NFM measures (which may be perceived as less aesthetically pleasing than later-stage, vegetated measures). Further research could also fruitfully explore the use of photo manipulation of existing images to add NFM measures to existing landscapes, as was carried out in Poledniková and Galia’s (Citation2021) study of river restoration efforts.

The positive response to the pictures showing NFM in action in the visioning workshops points to the possibility that more could be to be done to communicate about the way NFM works and its potential benefits. This could include showing examples of NFM in action through a variety of communication methods, including interpretation boards in the landscape and social media. This could help build community confidence in NFM without people actually having to experience an extreme flooding event with measures in place. Testing the effectiveness and affordances of different graphics and images showing how NFM functions during flooding events is a potentially fruitful area for further research. This could be complemented by research into ways to adapt these to different local contexts, such as through use of historical maps combined with those representing the present day and future plans for NFM, before and after aerial photos showing changes in the landscape, and including information about co-benefits, such as improvements for local wildlife and recreation.

7. Conclusions

As extreme storm events and rainfall are likely to increase, understanding drivers for, and barriers to, widespread uptake of NFM is a key aspect of reducing flood risk. This research has added to the debate by exploring perceptions in hitherto under-researched peri-urban areas. It has unpacked differences in perception between community members and professionals working in the field, through analysing responses to picture- and scenario-based exercises. This led to several insights that cast a new understanding of our existing knowledge from the literature – in particular around a higher level of confidence in NFM measures shown by community members after a major storm event in their area than by those without this experience, and the value of showing the way NFM functions through images of measures in action. A further intriguing insight was the positive response by community members to leaky dams, traditionally seen as an “untidy” element of NFM. This could be in response to the engagement around benefits for wildlife, and points to the value of engagement around co-benefits no matter what the driver for change.

This research has shown the importance of early and active engagement in helping to build trust in delivery organisations and support for NFM measures. Our findings point to the value of exploring multi-functional benefits in such engagement – clearly linking landscape restoration aimed at wildlife improvements to flood reduction benefits, and conversely, communicating benefits for wildlife emerging from NFM measures (indeed, in many cases using these as the driver for NFM). A related insight linked to multi-functionality is the need to consider and discuss recreation, access and waymarking from the outset of project planning and community engagement.

The co-benefits of NFM interventions should be considered more holistically. Considering these measures as a form of green infrastructure, with a clear steer towards thinking of active transport through the landscape and accessibility, may help in this holistic reframing. Increased knowledge and discussion of the multi-functional co-benefits of NFM amongst partners and delivery organisations would enable new ways for them to work together effectively.

Given the need for a learning by doing approach, it is helpful to embed skills development in community engagement. This increases capacity for ongoing engagement and fruitful dialogue about changes in the landscape. It can also increase interest amongst those who may be harder to reach, as the engagement offers something of value to them. A further lesson is the need to consider multiple channels of communication in addition to active engagement. In particular, informational resources about the function and value of NFM situated in the landscape through interpretation boards can extend the reach and longevity of the learning.

A suitable funding mechanism that includes allocations for both capital spend and ongoing revenue payment for management and engagement could improve uptake of NFM. Opportunities may arise to create a suitable funding system that encourages NFM at the landscape scale through investment in natural capital and provision of ecosystem services (i.e. co-benefits of NFM). A key area for future research and practice is to consider how to make the most of potential co-benefits of NFM in any large-scale roll out, which includes consideration of how NFM is framed and communicated.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Power Point (9.2 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants and the partners and project officers of the Carbon Landscape Programme, who put in a huge amount of effort to ensure continued engagement throughout the lockdown of the pandemic. Special thanks are due to Fraser How for co-facilitating the phase two workshops, Matt Sanderson for his ingenuity in supporting digital engagement, and Mark Champion for sharing his insights on implementing NFM. Three anonymous reviewers provided detailed and helpful suggestions, which improved the flow and clarity of the argument, and helped firm up the international relevance of the findings. Graham Haughton, Arianne Shahvisi and Ian Dennis provided insightful reviews and feedback, but bear no responsibility for errors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ambiental. 2021. “UK Flood Report – Storm Christoph.” Accessed 22 October 2022. https://www.ambientalrisk.com/uk-flood-report-storm-christoph-2021/

- Anderson, Carl, and Fabrice Renaud. 2021. “A Review of Public Acceptance of Nature-Based Solutions: The ‘Why’, ‘When’, and ‘How’ of Success for Disaster Risk Reduction Measures.” Ambio: A Journal of Environment and Society 50 (8): 1552–1573. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01502-4.

- Anderson, Carl, Fabrice Renaud, Stuart Hanscomb, and Alejando Gonzalez-Ollauri. 2022. “Green, Hybrid, or Grey Disaster Risk Reduction Measures: What Shapes Public Preferences for Nature-Based Solutions?” Journal of Environmental Management 310: 114727. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114727.

- Auster, Roger, Alan Puttock, and Richard Brazier. 2020. “Unravelling Perceptions of Eurasian Beaver Reintroduction in Great Britain.” Area 52 (2): 364–375. doi:10.1111/area.12576.

- Bark, Rosalind, Julia Martin-Ortega, and Kerry Waylen. 2021. “Stakeholders’ Views on Natural Flood Management: Implications for the Nature-Based Solutions Paradigm Shift?” Environmental Science & Policy 115: 91–98. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.10.018.

- Buchecker, Matthias, Dominika Maria Ogasa, and Elizabeth Maidl. 2016. “How Well Do the Wider Public Accept Integrated Flood Risk Management? An Empirical Study in Two Swiss Alpine Valleys.” Environmental Science & Policy 55 (2): 309–317. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.021.

- Chin, Anne, Melinda Daniels, Michael Urban, Hervé Piégay, Kenneth Gregory, Wendy Bigler, Anya Butt, et al. 2008. “Perceptions of Wood in Rivers and Challenges for Stream Restoration in the United States.” Environmental Management 41 (6): 893–903. doi:10.1007/s00267-008-9075-9.

- Connelly, Angela, Andrew Snow, Jeremy Carter, and Rachel Lauwerijssen. 2020. “What Approaches Exist to Evaluate the Effectiveness of UK-Relevant Natural Flood Management Measures? A Systematic Map Protocol.” Environmental Evidence 9 (11): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s13750-020-00192-x.

- D’Souza, Mikaela, Matthew Johnson, and Christopher Ives. 2021. “Values Influence Public Perceptions of Flood Management Schemes.” Journal of Environmental Management 291: 112636. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112636.

- Dadson, Simon, Jim Hall, Anna Murgatroyd, Mike Acreman, Paul Bates, Keith Beven, Louise Heathwaite, et al. 2017. “A Restatement of the Natural Science Evidence Concerning Catchment-Based ‘Natural’ Flood Management in the UK.” Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Science 473 (2199): 1–19. doi:10.1098/rspa.2016.0706.

- Ellis, Nicola, Karen Anderson, and Richard Brazier. 2021. “Mainstreaming Natural Flood Management: A Proposed Research Framework Derived from a Critical Evaluation of Current Knowledge.” Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 45 (6): 819–841. doi:10.1177/0309133321997299.

- European Union. 2007. “Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the Assessment and Management of Flood Risks.” Official Journal of the European Communities L 288/27:27–34. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32007L0060.

- Gregory, K. J., and R. J. Davis. 1993. “The Perception of Riverscape Aesthetics: An Example from Two Hampshire Rivers.” Journal of Environmental Management 39 (3): 171–185. doi:10.1006/jema.1993.1062.

- Gunnell, Kelly, Mark Mulligan, Robert Francis, and David Hole. 2019. “Evaluating Natural Infrastructure for Flood Management within the Watersheds of Selected Global Cities.” The Science of the Total Environment 670: 411–424. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.212.

- Hein, Thomas, Ulrich Schwarz, Helmut Habersack, Julian Nichersu, Stefan Preiner, Nigel Willby, and Gabriele Weigelhofer. 2016. “Current Status and Restoration Options for Floodplains along the Danube River.” The Science of the Total Environment 543 (Pt A): 778–790. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.09.073.

- Holstead, Kirsty L., Wendy Kenyon, Josselin Rouillard, Jonathan Hopkins, and C. Galán-Díaz. 2017. “Natural Flood Management from the Farmer’s Perspective: Criteria That Affect Uptake.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 10 (2): 205–218. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12129.

- How, Fraser, and Joanne Tippett. 2021. Evaluation of Community Engagement: Towards a National Nature Reserve in the Flashes of Wigan and Leigh. Report for Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and Natural England. Manchester: The University of Manchester. https://carbonlandscape.org.uk/resource-category/fraser-how-joanne-tippett-evaluation-community-engagement-nnr.

- Howgate, Olivia, and Wendy Kenyon. 2009. “Community Cooperation with Natural Flood Management: A Case Study in the Scottish Borders.” Area 41 (3): 329–340. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00869.x.

- Iacob, Oana, John Rowan, Iain Brown, and Chris Ellis. 2014. “Evaluating Wider Benefits of Natural Flood Management Strategies: An Ecosystem-Based Adaptation Perspective.” Hydrology Research 45 (6): 774–787. doi:10.2166/nh.2014.184.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/.

- Kenyon, Wendy. 2007. “Evaluating Flood Risk Management Options in Scotland: A Participant-Led Multi-Criteria Approach.” Ecological Economics 64 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.06.011.

- Lorenzoni, Irene, Sophie Nicholson-Cole, and Lorraine Whitmarsh. 2007. “Barriers Perceived to Engaging with Climate Change among the UK Public and Their Policy Implications.” Global Environmental Change 17 (3-4): 445–459. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.004.

- Mell, Ian. 2019. Green Infrastructure Planning: Reintegrating Landscape in Urban Planning. London: Lund Humphries.

- Mostert, Erik, Claudia Pahl-Wostl, Yvonne Rees, Brad Searle, David Tàbara, and Joanne Tippett. 2007. “Social Learning in European River-Basin Management: Barriers and Fostering Mechanisms from 10 River Basins.” Ecology and Society 12 (1): 16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267838. doi:10.5751/ES-01960-120119.

- Oisalu, Sandra. 2022. “Barriers and Enablers for up-Scaling NbS in Urban Environment in the Baltic States.” LAND4FLOOD. COST Action CA16209, European Cooperation in Science and Technology. n.d. http://www.land4flood.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/VM_report-Up-scalingNBS-final.pdf.

- Poledniková, Zuzana, and Tomáš Galia. 2021. “Photo Simulation of a River Restoration: Relationships between Public Perception and Ecosystem Services.” River Research and Applications 37 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1002/rra.3738.

- Posthumus, H., J. R. Rouquette, J. Morris, D. J. G. Gowing, and T. M. Hess. 2010. “A Framework for the Assessment of Ecosystem Goods and Services: A Case Study on Lowland Floodplains in England.” Ecological Economics 69 (7): 1510–1523. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.02.011.

- Raška, Pavel, Nejc Bezak, Carla S. S. Ferreira, Zahra Kalantari, Kazimierz Banasik, Miriam Bertola, Mary Bourke, et al. 2022. “Identifying Barriers for Nature-Based Solutions in Flood Risk Management: An Interdisciplinary Overview Using Expert Community Approach.” Journal of Environmental Management 310: 114725. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114725.

- Tippett, Joanne, Iain Deas, and Graham Haughton. 2022. “Geo-Environmental Spatial Imaginaries: Reframing Nature Using Soft Spaces and Hybrid Rationalities.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 4: 1–15. doi:10.3389/frsc.2022.882929.

- Tippett, Joanne, and Fraser How. 2020. “Where to Lean the Ladder of Participation: A Normative Heuristic for Effective Coproduction Processes.” Town Planning Review 91 (2): 109–132. doi:10.3828/tpr.2020.7.

- Tseng, Chin-Pei, and Edmund Penning-Rowsell. 2012. “Micro-Political and Related Barriers to Stakeholder Engagement in Flood Risk Management.” The Geographical Journal 178 (3): 253–269. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2012.00464.x.

- Tufte, Edward. 1990. Envisioning Information. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

- Waylen, K. A., K. L. Holstead, K. Colley, and J. Hopkins. 2018. “Challenges to Enabling and Implementing Natural Flood Management in Scotland.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 11 (2): S1078–S1089. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12301.

- Wells, Josh, Jillian Labadz, Amanda Smith, and Mofakkarul Islam. 2020. “Barriers to the Uptake and Implementation of Natural Flood Management: A Social-Ecological Analysis.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 13 (Suppl. 1): e12561. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12561.

- Wengel, Yana, Alison McIntosh, and Cheryl Cockburn-Wootten. 2019. “Co-Creating Knowledge in Tourism Research Using the Ketso Method.” Tourism Recreation Research 44 (3): 311–322. doi:10.1080/02508281.2019.1575620.

- Werritty, Alan, Donald Houston, Tom Ball, Amy Tavendale, and Andrew Black. 2007. Exploring the Social Impacts of Flood Risk and Flooding in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive, Central Research Unit. https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20150219020106/http:/www.gov.scot/Publications/2007/04/02121350/0

- Wharton, Geraldene, and David Gilvear. 2007. “River Restoration in the UK: Meeting the Dual Needs of the European Union Water Framework Directive and Flood Defence?” International Journal of River Basin Management 5 (2): 143–154. doi:10.1080/15715124.2007.9635314.

- Wingfield, Thea, Neil Macdonald, Kimberley Peters, and Jack Spees. 2021. “Barriers to Mainstream Adoption of Catchment-Wide Natural Flood Management: A Transdisciplinary Problem-Framing Study of Delivery Practice.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 25 (12): 6239–6259. doi:10.5194/hess-25-6239-2021.