Abstract

In the field of participatory health research (PHR) and related action research paradigms, limitations of standard ethical codes and institutional review processes have been identified. PHR is highly situational and relational, part of a hierarchical health care context and therefore ethics of care has been suggested as a helpful theoretical approach that emphasises responsibilities and relationships. The purpose of this article is to explore the value of Tronto’s second-generation ethics of care for reflection on ethical challenges experienced by academic researchers. Using the design of a collaborative auto-ethnography, this article starts from a story of a researcher who deals with dilemmas in responsibility to care for co-researchers with lived experiences during a PHR study in the field of acute psychiatric care. By analysing the challenges together with all co-researchers, using a framework of ethics of care, we discovered the importance of self-care and existential safety for an ethical PHR practice. The reflexive meta-narrative shows that the ethics of care lens is useful to untangle moral dilemmas in all participatory research-related paradigms for all engaged.

Introduction

Participatory approaches to health and health care research are increasingly drawing the attention of researchers, decision-makers and civil society worldwide (ICPHR Citation2013a). Especially in Western European welfare states, which are under great pressure to reform their care policies (Grootegoed and Tonkens Citation2017), democratic and participatory approaches are undergoing a revival. The appeal to ‘active’ citizenship and participation is framed as furthering citizens’ voice and empowerment; citizens are invited to participate in policy and decision-making and the co-creation of care arrangements in their communities (Grootegoed Citation2013). This creates an ambiguous situation. On the one hand, there is more interest in participatory research approaches, and on the other hand, it has yet to be seen whether participation is more than just a token and co-optation in decisions to realise entrenchments (Barnes and Cotterell Citation2012).

Participatory health research (PHR) is an emerging research paradigm in the context of health and welfare (ICPHR Citation2013a), and a new branch on the tree of action research (Reason and Bradbury Citation2001). It is informed by a rich variety of participatory (action) research traditions from different countries and time periods, which all stress emergent designs, democratic decision-making, working from practice, learning-by-doing and a focus on human flourishing and social justice. The core and defining principle of PHR is to maximise the participation of those whose life or work is the subject of the research in all stages of the research process (ICPHR Citation2013a). This includes people in vulnerable health situations, and their capacity to take collective action to improve local situations as well as to reduce structural inequalities and health disparities.

PHR demands particular attention to ethical issues related to conflicting interests and power structures. PHR aims for democratisation of knowledge production, but takes place in a highly hierarchic context with dominant normative biomedical frameworks to health and illness, biomedical experts who consider their expertise as leading and positivism as the paradigmatic basis for most research (Bowling Citation2014). In such a context, the voice of service-users and those who are living in vulnerable situations is easily silenced. Several literature reviews have shown a range of ethical challenges in action research (Brydon-Miller Citation2008, 2012; Smith et al. Citation2010), community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Banks et al. Citation2013; Boser Citation2007; Mikesell, Bromley, and Khodyakov Citation2013; Souleymanov et al. Citation2016; Wilson, Kenny, and Dickson-Swift Citation2018), insider action research (Holian and Coghlan Citation2013) and PHR (Banks and Brydon-Miller, Citationforthcoming). All challenges focus on the balancing of hierarchies, collaboration with co-researchers, the establishment of trustful relationships, the sharing of control and ownership and working towards social justice. Responsibility is also a recurring issue (Groot and Abma Citationn.d.).

The role and procedures of ethical review processes by ethical boards of scientific institutes and their contributions in dealing with ethical dilemmas have been extensively discussed in the literature on participatory action research. Fouché and Chubb (Citation2017) argue on the basis of a literature review that ethical research committees are uninformed, underprepared and often unwilling to deal with projects of this nature. Ethical challenges of PHR- and PAR-related paradigms cannot easily be fixed by standard ethical codes and institutional review processes for research, and stretch beyond principles of privacy, anonymity, informed consent and confidentiality (Locke, Alcorn, and O’Neill Citation2013). More is needed from a good PHR process than just following these rules (Brydon-Miller Citation2008). Therefore, the International Collaboration for PHR developed a specific set of ethical criteria for PHR (ICPHR Citation2013b), including mutual respect, equality, inclusion, democratic participation, active learning, making a difference, collective action and personal integrity. Although these provide some guidance, the moral goodness of PHR is situational and relational. To gain more guidance in the situational dimension, Banks and colleagues (Citation2013) suggest ‘everyday ethics’ as an approach to negotiate ethical issues and challenges that arise in the practice of PHR.

This article builds further on their situational and relational approach using feminist ethics of care theories as inspiration to sensitise researchers for the multiple layers of moral responsibility in asymmetric caring relations, as Tronto (Citation1993) and Walker (Citation2007) among others note (Visse and Abma Citation2018). It is the explicit attention for the role of power and care in relationships that led us use ‘ethics of care’ as a theoretical approach to ethics in PHR (Balakrishnan and Cornforth Citation2013; Charles Citation2012; Jones and Stanley Citation2008). Bearing the neo-liberal climate and invisibility of care in Western countries as contextual factor in mind, the second-generation ethics of care of Joan Tronto (Citation2013) may shine light on the situational and relational ethical challenges of PHR in this era. The purpose of this article is twofold: (1) to unravel responsibilities among collaborating co-researchers in a PHR study in a context of psychiatry and (2) to explore the value of using an ethics of care framework to understand ethical challenges for co-researchers. The paper contains a co-constructed auto-ethnographic narrative about collaborative challenges for co-researchers. The narrative is written from the first person of a researcher. She, the first author, brings the perspectives of other co-researchers into the story. The narrative is structured and informed by the framework of the second-generation ethics of care (Tronto Citation2013). A discussion section ends with a reflexive meta-narrative to describe the value of the ethics of care lens to untangle moral dilemmas in PHR.

Theoretical framework

Ethics of care is a feminist-based ethical theory, focusing on responsibility, social interconnectedness and collaboration, that has emerged as a field of theoretical and applied interest in many disciplines (Barnes et al. Citation2015; Gilligan Citation1982; Noddings Citation2013; Sayer Citation2011; Tronto Citation1993, 2013; Walker Citation2007). This theory focuses less on abstract rules, principles and moral judgments, and more on caring and empathy. The understanding that humans are relational beings and interdependent is central to the theory (Barnes et al. Citation2015).

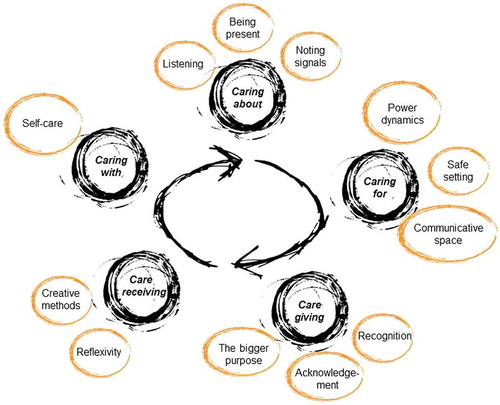

Tronto (Citation2013), an influential political ethicist, updated ethics of care in times of recent reforms in care to challenge the dominance of neoliberalism, which overvalues individualistic, self-autonomous and self-interested actions. She proposes a ‘second-generation ethics of care’ as a political argument for care together with a set of principles and actions within political and institutional systems as well as within interpersonal caring relations. According to this generation, ethics of care caring consists of five phases with different responsibilities (Tronto Citation2013): caring about – recognising a need for care, caring for – taking responsibility to meet that need, care giving – the actual physical work of providing care, care receiving – the evaluation of how well the care met the caring needs and caring with – caring needs to be consistent with democratic commitments to justice, equality and freedom for all, as visualized in .

Tula Brannelly (Citation2016) is one of the first participatory action researchers that interpreted the five phases and responsibilities of care to participatory research. She applied the stages of care to the research team, the participants and the wider community. An ethic of care framework offers context-specific ways of understanding and responding to the ethical challenges of undertaking PHR, and to the relational aspects of well-being identified by people during the course of the work (Ward and Gahagan Citation2010), for all co-researchers (Brannelly and Boulton Citation2017) in a PHR study, and responsive, participatory evaluation (Visse, Abma, and Widdershoven Citation2014; Visse and Abma Citation2018).

Collaborative auto-ethnography

Research setting

The Netherlands, as in other Western European welfare countries, is currently under great pressure to reform health care. Social, demographic and economic developments are challenging the sustainability of the welfare states (Grootegoed Citation2013). To respond to the growing ‘care crisis’ (Hochschild Citation1995), many European states are off-loading public responsibilities for care (Newman and Tonkens Citation2011) and encouraging citizens to become more self-sufficient. The appeal to ‘active’ citizenship is framed as promoting citizen voice and empowerment.

The clinical setting described in this paper is acute psychiatric care. We write about our experiences of working together in the first phase of a long-term PHR study that aims to enhance the quality of care of clients in urban emergency psychiatry. The first phase of the study aimed to start a dialogue about experiences of clients and other stakeholders in psychiatric emergency care. The study is subsidised by two psychiatric care institutions in the Netherlands and took place in 2016. Four of the co-researchers had lived experiences in psychiatric care and crisis.

Design

The paper presents a collaborative auto-ethnography (CAE), a collaborative, autobiographic and ethnographic form of qualitative inquiry. CAE is a ‘qualitative research method in which researchers work in community to collect their autobiographical material and to analyse and interpret their data collectively to gain a meaningful understanding of sociocultural phenomena reflected in their autobiographical data’ (Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez Citation2016). We choose this approach because it fits the principles of PHR, such as working participatively in all stages of our work together with those involved, sharing power, deep learning about self and others, valuing lived experiences of those involved and combining different perspectives (as well academic co-researchers as co-researchers with lived experiences).

Auto-ethnography (AE) uses autobiographic data and interprets cultural patterns (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011). According to the continuum of auto-ethnographies, which is anchored on two ends, one emphasising autobiography and the other ethnography (Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez Citation2016), we position this paper on the end of ethnographers. This means that we as researchers focus more on the cultural interpretation (ethno) of self (auto) than on the self (auto) and narration (graphy). In this paper, we use personal stories as a frame through which we interpret.

Author team

The research team of this CAE consists of six authors. The first author was a novice PHR academic researcher at the time of the study, having previously worked in qualitative research in a consultancy setting and a health care institution for 10 years. The last author is her PhD supervisor. Most of the other authors had collaborated with the first and last author in earlier studies. All authors were part of the team during the first phase of a long-term PHR study that aims to enhance the quality of care of clients in urban emergency psychiatry.

Four of the authors have lived experiences in psychiatric care and crisis. Some authors had several traumatic experiences with emergency care. One had experiences with coercion and two had experiences in crisis in which police were involved. Co-researchers also had experienced ‘silent crises’ without help of an acute psychiatric team or a freelance psychiatrist. To reduce the vulnerability of the authors, we choose to anonymise names in the narrative.

Reflexive research-writing process

We all participated in this CAE, but in different ways to build on the strengths of each individual and to keep in mind the limitations we all have. One co-researcher was dyslexic and could not read English language. To involve this co-researcher, the first author translated the texts and read them aloud. The last author had experience in writing auto-ethnographies, like ethno dramas (Baur, Abma, and Baart Citation2014; Schipper et al. Citation2010), counter stories (Teunissen, Visse, and Abma Citation2015; Woelders et al. Citation2015) and co-constructed auto-ethnographies (Snoeren et al. Citation2016; Snoeren, Niessen, and Abma Citation2012; Teunissen, Lindhout, and Abma Citation2018), but the process of collaboratively writing a CAE together in a team with co-researchers with a lived experience was new to all of us. It was a journey in which the decision-making about who collaborated in which part of the AE was coordinated by the first author. Coordination included activities described by Lowry, Curtis, and Lowry (Citation2004) as important in collaborative writing processes such as researching, socialising among members, communicating, negotiating, coordinating, monitoring the progress of the group.

The process of collaboration was an iterative process, in which we used a sequential model of collaboration (Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez Citation2016). The first step was collecting autobiographical data (personal memory, archival data and self-reflexive data). Data include field notes in a logbook and transcripts of evaluation sessions. In the second phase, the first author analysed her own data in a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), while writing a first narrative. The last author wrote dialogically to the first piece, adding her perspective, critical questions and theoretical reflections. This process continued (cf. Toyosaki et al. Citation2009). The first author had informal and formal personal conversations about the story with the co-researchers during the writing process. The formal conversations were audiotaped. Co-researchers added their experiences and perspectives to the story in these meetings. The conversations were transcribed verbatim. We used a mix of interpretive and confessional-emotive writing style (Lowry, Curtis, and Lowry Citation2004). The final step included proofreading by all team members and a final member check (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985) with all members.

Ethical considerations

Writing this CAE raises ethical questions about vulnerabilities of all involved in the story. As Tolich (Citation2010) argues, ‘vulnerability of people involved is much more than an informed consent procedure’. In this study, we used relational ethics and tried to practice what we preach. We anticipated the possible ethical issues in several concrete ways: (1) we do not use the names of authors in the narrative, (2) we have acknowledged vulnerabilities and power differentials of all involved, (3) we were selective about what to include, (4) we fictionalised pieces within the narrative and (5) we checked the story several times with all involved.

Reflections about the process of writing

This article was set up as an AE (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011) of the first author, together with the final author. While writing this piece, the first author felt morally challenged. Working from a PHR paradigm means maximisation of participation of those who live in the subject of the study, including the phase of academic writing. Writing an AE did not fit the principles of PHR. However, the topic of this piece and the whole process was sensitive to the people involved. The situation of our co-researchers was not always stable and the relations felt to be under pressure when the first author shared her plans of writing about the topic of this paper. One moment, a year before submitting this article, the authors decided to change the AE method and use the CAE design to do justice to the collaborative effort and co-ownership. In this article, readers will notice that the story is therefore not always as ‘multi-voiced’ as we wanted it to be. The whole writing process exemplifies in a sense our care ethical approach.

Experienced benefits and limitations of CAE

Writing a CAE together with co-researchers with lived experiences could boost trusting relationships among co-researchers, promote deep listening and creativity and offer collegial feedback (Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez Citation2016). Trusting thoughts and feelings to paper could also be confronting for yourself and the other team members. Not every co-researcher in the process liked to read what others thought and wrote, especially because co-researchers knew that this writing process would lead to a public paper. Despite these tensions and messiness (Cook Citation2009), we all experienced it as a fruitful process. Co-researchers noticed that they felt taken seriously and they learned from the hermeneutic process CAE of storytelling and re-storying. Writing and reflecting together enriched our meaning of the collaboration, including difficult and emotional phases.

Writing this CAE taught us three lessons about the process of writing collaboratively. Writing together about collaboration and care is not easy in times of emotional stress. Some distance and time seem necessary to reflect on the process. Besides writing and more in particular, academic writing in English was exclusionary for those who were dyslectic and not used to academic writing for an international audience.

The co-constructed story: caring relations in a PHR study

The narrative is written from the first person of a researcher. She brings the other perspectives of co-researchers into the story. The narrative is structured and informed by the framework of a second-generation ethics of care (Tronto Citation2013), as visualised in .

Figure 1. Five stages of a second-generation ethics of care of Tronto (Citation2013).

Prelude: responsibility to care?

I have been involved in PHR for three years now. In the studies I conduct, I work intensively together with co-researchers with lived experiences. It is the inclusive philosophy I embrace, and at moments I feel like a scholarly activist who promotes participatory approaches in development and evaluation of health policy and care. Although I love to work in this participatory way, it is not always easy and sometimes bumpy, especially concerning connectedness. I experience on a daily basis the ‘mess in participatory processes’ (Cook Citation2009) and the ‘swampy lowlands’ (Schön Citation1983). Also in writing this CAE, I experienced ‘mess’ while I was collaboratively researching the sensitive topic of collaboration with my co-researches.

One of the topics I most often reflected on was my responsibility towards the co-researchers with lived experiences. In my logbook, I wrote, for example:

November 2016. I got a message on my mobile phone on Friday evening from one of my co-researchers. She felt down. ‘I do not see any point in all this…’ What do I have to do at that moment? Did I do right by not calling back and waiting till Monday morning?

April 2017. In conversations with a co-researcher, I noticed that the research had a huge impact. One day I asked her, ‘How is life?’ She swallowed, and I saw tears in her eyes. After a moment she said, ‘I am expected to do this… I hope others will get better care by doing this.’ I asked her if she had support from others in his network. She said, ‘No, I do not talk about this with my psychiatrist. We talk about other things…’ Again, I was in doubt. What was my responsibility in this?

As co-researchers, we wondered if the framework of Tronto (Citation2013) could help us in facilitating a PHR study with a highly sensitive topic, to assess questions about responsibilities. This could inform our actions in PHR studies in the future. We now dive into our experiences and the interpretation of these experiences with the help of the ethics of care framework and its five steps of care.

Care about: balancing patronising and neglecting of the strong

The first step in the framework of Tronto (Citation2013) is caring about. Tronto describes this step as noticing someone’s or some group’s caring needs. The moral quality in this step is attentiveness. This means ‘a suspension of one’s self-interest and a capacity genuinely to look from the perspective of the one in need’ (Tronto Citation2013, 34). In the light of my overall questions about responsibility, I questioned what responsibility I had in being attentive to co-researchers. A more elaborated story about my struggle:

December 2016. In our group meetings, I observed that one of the co-researchers got upset more often, that her face grew gloomy now and then, and in her narrative I heard that nobody was listing to her. I interpreted this as that she was balancing in health and I was aware for possible harm of the research to her situation. I noticed it, but I did not know what to do with the signals. What is my moral responsibility in this? A week later, she told us that she withdrew her active involvement from the project for a while. I was also relieved that she took this decision because she told us that she had arranged support at home. I let it go. A few weeks later she felt better and re-joined the team actively.

A co-researcher: ‘I as a patient expert am full-grown. You are not responsible for my pain. You are not guilty for that…. Patient experts are not very vulnerable people. Do you understand what I mean? They are able to reflect on their own situations.’

A co-researcher: ‘This is a typical situation in psychiatry. You related my behaviour to my background of psychiatric problems and interpreted that the research about the emergency department of psychiatry was too much for me. But I did not tell anyone yet that I was diagnosed with cancer at that moment. You couldn’t know that. But your reaction is typical, based on prejudices about patient experts.’

A co-researcher: ‘If you are on the edge of a crisis, as I was in this study, the connection between my body and mind is broken. I did not felt my body. I was in “my head”. This means that I cannot feel signals of my body. I cannot be empathic, because I miss the signals in my body. This makes it difficult to connect with others. Being responsible or attentive to others is not possible at that moment.’

A co-researcher: ‘Well, I personally did feel “care”. I felt protected. It helped me. Your sensitivity... Psychiatric emergency care is not an easy subject to study for people with lived experiences in this subject. I can imagine that you identified needs incorrectly, because you are not familiar with the world of psychiatry and crisis, and do not have close friends who experienced psychiatric crisis situations.’

A co-researcher: ‘Two moments in this project, I was on the edge of a crisis and thought of extra medication. I knew that this project should be a challenge for all of us. And it was. I know that is part of the job of being a patient expert. I did not know you also was vulnerable and experienced it as heavy. It is good that you are open to us now.’

Care for: shared responsibility of each other’s safety

The second step is care for: ‘take on the burden of meeting the needs identified in step one’ (Tronto Citation2013, 34). I interpreted this as to create a safe setting, a communicative space (Kemmis Citation2006) together with each other, by sharing power and control over the process as a mutual responsibility. You can easily overlook this type of caring, because it is for example not described as an ethical principle in the PHR guidelines (ICPHR Citation2013b). Besides, it is traditionally limited to prevention of harm and only highlighted at the start of the process by the medical ethical committee to the principle investigator of the university, not to all co-researchers involved. It concerns a moral responsibility, that is to say, a responsibility for the well-being of people and for the ‘humanness’ of the process. One of the co-researchers reminded me, for example, of how she experienced our caring for:

A co-researcher: ‘We also discussed what conditions were necessary for co-researchers with lived experiences to feel safe in dialogue sessions about the conclusion of the research with professionals from the emergency department of the psychiatric hospital. For example, giving a stage for co-researchers to tell their story and have voice. The meeting started as a plenary with a song that was important for a co-researcher with lived experiences in times of crisis.’

A co-researcher: ‘I insisted to join a conference call with four of you, as organizers of the dialogue session. I made clear that we had to discuss conditions to feel safe at the session for clients with lived experiences. I thought it was important because you decided to organize the session in the building of the emergency department of the psychiatric hospital. The reason for this was that professionals of the department could join easily. It looked like you did not think about the clients and patient experts, who also were invited. Traumatic memories in relation to the emergency department in this building could be triggered.’

While writing this CAE, we heard from a co-researcher that she was confronted with psychiatric care workers in the dialogue session who treated her when she was in crisis. The moment I heard this, I was a bit shocked. I was not at all aware of that risk, and also not aware of this clash. I asked the co-researcher how she felt. She told me that the power dynamics were present and made the session very difficult for her.

A co-researcher: ‘I felt that I was seen as a client. Not as a “whole person”. Not at all as a patient expert or co-researcher. It was terrifying, because that is my current identity, role, and expertise nowadays. As a client, you always need to prove yourself again and again. Showing that you have distance to the subject of the study. Showing that it is not only “my story”, but the story of a range of clients.’

My lesson of this caring for is that conducting a PHR study in one town, together with clients and professionals, we need to speak out that people could know each other from a client–caregiver dynamic and be aware of this power dynamic to create existential safety.

Care giving: organise and connect

The third step in the framework is care giving. This step consists of the actual laborious activity of care (Tronto Citation2013). In my role as a facilitator, I give care via my attitude and flexible behaviour in order to attune to needs. Welcoming team members with open arms after a period of not seeing each other. Arranging practical issues, such as cookies at meetings, a flower as a gift, a card at Christmas, arrangements to make sure co-researchers arrive at the right location for meetings. The gifts that team members gave each other during the project were especially valuable for all of us – not only the presents we gave to the co-researchers with lived experiences who worked voluntarily, but also the presents that co-researchers gave to researchers who worked in the academy.

A co-researcher: ‘I was emotional one moment at a session. The rose I got from you a few minutes after that moment gave me strength. I appreciated that.’

A co-researcher: ‘Appreciating and working with the knowledge of patient experts is important, showing that they are valuable and acknowledging someone’s competences.’

This reminded one of the co-researchers of the financial compensation of the co-researchers with lived experience.

A co-researcher: ‘As Tronto reminds us, caring is more than an attitude. It is also a physical activity and involves thought, emotion, action, and work. One of the issues we did not care for is a proper salary for patient experts who participated for a voluntary fee. The fee they received for their contribution is not in line with their actions and knowledge they brought in the project. This feels as a moral dilemma.’

A co-researcher: ‘You should not forget that we get a lot of recognition from our work.’

A co-researcher: ‘Working on these studies means for me that I learn, I contribute to society, I have colleagues, I work on things that matter, I do matter, I exist.’

In sum, organising immaterial gifts and salary as recognition for the value of co-researchers with lived experiences is an important act of care giving. Reminding everybody involved of our shared purpose with the research, namely building together a more sustainable society, could also be seen as an act of care giving.

Care receiving: openness receive care

The fourth step in the framework is care receiving, observing responses to care and making judgements about it. This requires the moral quality of responsiveness (Tronto Citation2013). Continuously monitoring the participatory way of working is a translation of care receiving to PHR studies. After meetings, I informally evaluated the meetings one to one or in the group. This reflexive behaviour is a basic value of being an academic co-researcher in action research (ICPHR Citation2013a; Reason and Bradbury Citation2001).

One of the co-researchers brought in the theoretical notion of ethics of care.

A co-researcher: ‘We are all in the position of giving and receiving care, interdependent of each other. But receiving care from each other is not always simple. Not everybody accepts care from others in the group. Opening your heart to each other requires safety.’

A co-researcher: ‘I was surprised at the effect of this creative way of working. Making a drawing or talking about a picture is a good way to talk about emotions and it felt safe to share.’

A final surprising insight for me in care receiving was the fact that every co-researcher has one’s own goal by participating and everyone benefits somehow. One of the co-researchers told me that being triggered by traumatic experiences in the research helped her to start counselling for her trauma. I never thought of that positive side effect of the research. I always thought of side effects in terms of harm, not of healing.

Caring with: the edge of solidarity?

The final phase of care for Tronto (Citation2013) is caring with; caring needs to be consistent with democratic commitments to justice, equality and freedom for all. In my opinion, our PHR study was a vehicle to care with. The core principles of the PHR approach are also in line with this. By doing this PHR study, we tried to connect stakeholders (nurses, psychiatrists, family, patients/service users, management) to improve the emergency care together.

I noticed that some co-researchers with a lived experience felt a moral duty to solve problems in health care for one’s peers.

A co-researcher: ‘I work in this project to prevent that others will experience situations in care that I have experienced.’

A co-researcher: ‘Tronto reminds us to be self-reflexive on our own needs for care, and ensure that the self is not subsumed in a caring relationship. This self-care is needed to be able to act as a moral agent. Yet, being self-reflexive of our caring needs is a deeply emotional process, because it confronts us with our own vulnerability and interdependency in a world driven by meritocratic ideals and notions of being independent. Being vulnerable is all too easily confused with being weak and deplorable. This then leads to the hiding of vulnerabilities, especially in a context such as the university, to live up to the ‘norm worker ideal’.’

A co-researcher: ‘Self-care is necessary, especially in the precarious contemporary academic life in which permanent, fixed positions are rare, leading to insecurity, competition, and an enormous pressure to be academically productive and have social impact.’

A co-researcher: ‘A lot of patient experts have been isolated for a long time, and not felt valuable. When researchers, especially researchers from the honourable university, suddenly take you seriously, it is easy to not care for yourself. You can lose yourself, because you love the feeling of being valuable for society.’

Discussion

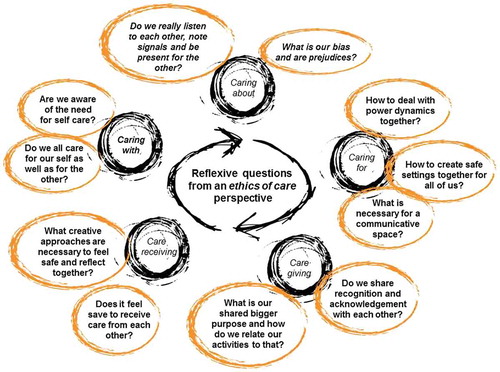

PHR is a relational, emotional and moral praxis. Those involved will encounter ethical issues on a daily basis (Banks et al. Citation2013), especially in studies with highly sensitive subjects such as acute psychiatric care. The value of Tronto’s (Citation2013) second-generation ethics of care is that it provides a framework for an in-depth analysis of asymmetric relationships to see the moral responsibilities of everybody engaged. It helps to tackle everyday issues around moral responsibility via a more in-depth way of inquiry. In this study, we learned about shared caring responsibilities in working together with co-researchers with lived experiences in PHR. See for a summary of issues, we uncovered in this study.

The ethics of care framework provides an additional lens, besides the PHR guidelines (ICPHR Citation2013b) to guide PHR co-researchers, and those working in related paradigms. It can help to sensitise researchers for the complex moral responsibilities of their work in a highly hierarchic context, and strengthen their reflexivity. The political caring perspective adds an important dimension which is often overlooked in society in general and research practices more in particular (Visse, Abma, and Widdershoven Citation2014; Visse and Abma Citation2018). This is not to say that participatory action researchers do not care. On the contrary, they do care, but this gendered kind of work typically remains invisible. This invisibility of care or the confinement of care to some sphere outside the research is exactly what motivated care ethicists to plea for crossing the boundaries between the private (care) and public (politics) domain (Tronto Citation1993).

We contend that an ethos of care should be part of PHR, because it deepens our understanding of our praxis and can help us to explain to others what it is that we do and strive for. In our study, the importance of existential safety came to the fore as an important concern in PHR additional to the existing guidelines (ICPHR Citation2013b). Not only highlighted by a medical ethical committee at the start of a study to a principle investigator, but a shared responsibility for all during a whole process. Moreover this CEA deepens the work of Brannelly (Citation2016), who first used the five-stage model of Tronto (Citation2013) in her work, with empirical findings from a context of psychiatric care. Stories like this one are important to develop our moral understandings of our praxis; it is through a myriad of stories and cases that we begin to discern our expertise (Nussbaum Citation2001; Ashcroft et al. Citation2005). Finally, our study emphasises the importance of care and self-care because PHR and other related participatory paradigms can and often are emotional labour. Care and self-care are especially important in a society governed by insecurity and precariousness as a new form of power over people (Bauman Citation2013; Vosman and Niemeijer Citation2017).

Implications for practice

Based on this research, we developed a compass for participatory researchers to reflect on their care relations. The compass consists of several questions, ordered in the five phase model of second-generation ethics of care (Tronto Citation2013). The questions are inductively based on the findings of this study. The aim of the questions is to stimulate reflexivity in research teams (see ).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ashcroft, R., A. Lucassen, M. Parker, M. Verkerk, and G. Widdershoven, eds. 2005. Case Analysis in Clinical Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511545450.

- Balakrishnan, V., and S. Cornforth. 2013. “Using Working Agreements in Participatory Action Research: Working through Moral Problems with Malaysian Students.” Educational Action Research 21 (4): 582–602.10.1080/09650792.2013.832347

- Banks, S., A. Armstrong, K. Carter, H. Graham, P. Hayward, A. Henry, T. Holland, et al. 2013. “Everyday Ethics in Community-Based Participatory Research.” Contemporary Social Science 8 (3): 263–277.

- Banks, S., and M. Brydon-Miller. Forthcoming. Ethics in Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-being: Cases and Commentaries. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Barnes, M., and C. Cotterell. 2012. “From Margin to Mainstream.” In Critical Perspectives on User Involvement, edited by M. Barnes and P. Cotterell, 15–26. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Barnes, M., T. Brannelly, L. Ward, and N. Ward, eds. 2015. Ethics of Care: Critical Advances in International Perspective. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Bauman, Z. 2010. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Baur, V., T. Abma, and I. Baart. 2014. “‘I Stand Alone.’ An Ethnodrama about the (Dis) Connections between a Client and Professionals in a Residential Care Home.” Health Care Analysis 22 (3): 272–291.10.1007/s10728-012-0203-6

- Bellingham, R., B. Cohen, T. Jones, and L. Spaniol. 1989. “Connectedness: Some Skills for Spiritual Health.” American Journal of Health Promotion 4 (1): 18–31.10.4278/0890-1171-4.1.18

- Boser, S. 2007. “Power, Ethics, and the IRB Dissonance over Human Participant Review of Participatory Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 13 (8): 1060–1074.10.1177/1077800407308220

- Bowling, A. 2014. Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and Health Services. London: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Brannelly, T. 2016. “Decolonising Research Practices with the Ethics of Care.” Nursing Ethics 23 (1): 4–6.10.1177/0969733015624297

- Brannelly, T., and A. Boulton. 2017. “The Ethics of Care and Transformational Research Practices in Aotearoa New Zealand.” Qualitative Research 17 (3): 340–350.10.1177/1468794117698916

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brydon-Miller, M. 2008. “Ethics and Action Research: Deepening Our Commitment to Principles of Social Justice and Redefining Systems of Democratic Practice.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, edited by R. Reason and H. Bradbury, 199–210. New York: Sage.

- Brydon-Miller, M. 2012. “Addressing the Ethical Challenges of Community-based Research.” Teaching Ethics 12 (2): 157–162.10.5840/tej201212223

- Chang, H., F. Ngunjiri, and K. A. C. Hernandez. 2016. Collaborative Autoethnography. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Charles, E. 2012. “Community Supported Agriculture as a Model for an Ethical Agri-Food System in North East England.” PhD thesis, New Castle University, New Castle.

- Cook, T. 2009. “The Purpose of Mess in Action Research: Building Rigour Though a Messy Turn.” Educational Action Research 17 (2): 277–291.10.1080/09650790902914241

- Ellis, C., T. E. Adams, and A. P. Bochner. 2011. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12 (1): 273–290.

- Fouché, C. B., and L. A. Chubb. 2017. “Action Researchers Encountering Ethical Review: A Literature Synthesis on Challenges and Strategies.” Educational Action Research 25 (1): 23–34.10.1080/09650792.2015.1128956

- Gibbs, C. 2005. “Spirit-aware Teacher and Learner: Relational Connectedness in Teaching and Learning.” Teachers and Curriculum 8 (1): 59–64.

- Gilligan, C. 1982. In a Different Voice. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Groot, B. C., and T. A. Abma. n.d. “Participatory Health Research with Older People: Navigating Power Imbalances towards Mutually Transforming Power.” In Participatory Health Research: Voices from Around the World, edited by M. Wright and K. Kongrats. Springer.

- Grootegoed, E. M. 2013. “Dignity of Dependence: Welfare State Reform and the Struggle for Respect.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam.

- Grootegoed, E., and E. Tonkens. 2017. “Disabled and Elderly Citizens’ Perceptions and Experiences of Voluntarism as an Alternative to Publically Financed Care in the Netherlands.” Health & Social Care in the Community 25 (1): 234–242.10.1111/hsc.2017.25.issue-1

- Hochschild, A. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hochschild, A. R. 1995. “The Culture of Politics: Traditional, Postmodern, Cold-modern, and Warm-modern Ideals of Care.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 2 (3): 331–346.10.1093/sp/2.3.331

- Holian, R., and D. Coghlan. 2013. “Ethical Issues and Role Duality in Insider Action Research: Challenges for Action Research Degree Programmes.” Systemic Practice and Action Research 26 (5): 399–415.10.1007/s11213-012-9256-6

- ICPHR (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research). 2013a. Position Paper 1: What is Participatory Health Research? Version: May 2013. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research.

- ICPHR (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research). 2013b. Position Paper 2: Participatory Health Research: A Guide to Ethical Principals and Practice. Version: October 2013. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research.

- Jones, M., and G. Stanley. 2008. “Children’s Lost Voices: Ethical Issues in Relation to Undertaking Collaborative, Practice-based Projects Involving Schools and the Wider Community.” Educational Action Research 16 (1): 31–41.10.1080/09650790701833089

- Kemmis, S. 2006. “Participatory Action Research and the Public Sphere.” Educational Action Research 14 (4): 459–476.10.1080/09650790600975593

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry, vols. 75. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Locke, T., N. Alcorn, and J. O’Neill. 2013. “Ethical Issues in Collaborative Action Research.” Educational Action Research 21 (1): 107–123.10.1080/09650792.2013.763448

- Lowry, P. B., A. Curtis, and M. R. Lowry. 2004. “Building a Taxonomy and Nomenclature of Collaborative Writing to Improve Interdisciplinary Research and Practice.” The Journal of Business Communication 41 (1): 66–99.10.1177/0021943603259363

- Mikesell, L., E. Bromley, and D. Khodyakov. 2013. “Ethical Community-engaged Research: A Literature Review.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (12): e7–e14.10.2105/AJPH.2013.301605

- Newman, J., and E. Tonkens. 2011. Participation, Responsibility and Choice : Summoning the Active Citizen in Western European Welfare States. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.10.5117/9789089642752

- Noddings, N. 2013. Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511817915

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury, eds. 2001. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. New York: Sage.

- Rykkje, L., K. Eriksson, and M. B. Råholm. 2015. “Love in Connectedness: A Theoretical Study.” SAGE Open 5 (1): 2158244015571186.

- Sayer, A. 2011. Why Things Matter to People: Social Science, Values and Ethical Life. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511734779

- Schipper, K., T. A. Abma, E. van Zadelhoff, J. van de Griendt, C. Nierse, and G. A. Widdershoven. 2010. “What Does It Mean to Be a Patient Research Partner? An Ethnodrama” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (6): 501–510.10.1177/1077800410364351

- Schön, D. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Smith, L., L. Bratini, D. A. Chambers, R. V. Jensen, and L. Romero. 2010. “Between Idealism and Reality: Meeting the Challenges of Participatory Action Research.” Action Research 8 (4): 407–425.10.1177/1476750310366043

- Snoeren, M. M., T. J. Niessen, and T. A. Abma. 2012. “Engagement Enacted: Essentials of Initiating an Action Research Project.” Action Research 10 (2): 189–204.10.1177/1476750311426620

- Snoeren, M. M., R. Raaijmakers, T. J. Niessen, and T. A. Abma. 2016. “Mentoring with (in) Care: A Co-constructed Auto-ethnography of Mutual Learning.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 37 (1): 3–22.10.1002/job.2011

- Souleymanov, R., D. Kuzmanović, Z. Marshall, A. I. Scheim, M. Mikiki, C. Worthington, and M. P. Millson. 2016. “The Ethics of Community-based Research with People Who Use Drugs: Results of a Scoping Review.” BMC Medical Ethics 17 (1): 25.

- Stanger, N. R. G. 2014. “(Re) Placing Ourselves in Nature: An Exploration of How (Trans) Formative Places Foster Emotional, Physical, Spiritual, and Ecological Connectedness.” Doctoral diss., University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- Teunissen, G. J., M. A. Visse, and T. A. Abma. 2015. “Struggling between Strength and Vulnerability: A Patient’s Counter Story.” Health Care Analysis 23 (3): 288–305.10.1007/s10728-013-0254-3

- Teunissen, G. J., P. Lindhout, and T. A. Abma. 2018. “Balancing Loving and Caring in Times of Chronic Illness.” Qualitative Research Journal. doi:10.1108/QRJ-D-17-00030.

- Tolich, M. 2010. “A Critique of Current Practice: Ten Foundational Guidelines for Autoethnographers.” Qualitative Health Research 20 (12): 1599–1610.10.1177/1049732310376076

- Townsend, K. C., and B. T. McWhirter. 2005. “Connectedness: A Review of the Literature with Implications for Counseling, Assessment, and Research.” Journal of Counseling & Development 83 (2): 191–201.10.1002/jcad.2005.83.issue-2

- Toyosaki, S., Pensoneau-Conway, S. L., Wendt, N. A., and Leathers, K. 2009. “Community Autoethnography: Compiling the Personal and Resituating Whiteness” Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies 9 (1): 56–83.10.1177/1532708608321498

- Tronto, J. C. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Tronto, J. C. 2013. Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality, and Justice. New York: New York University Press.

- Visse, M. A., and T. A. Abma. 2018. Evaluation for a Caring Society. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Visse, M. A., T. A. Abma, and G. A. M. Widdershoven. 2014. “Practising Political Care Ethics: Can Responsive Evaluation Foster Democratic Care?” Ethics & Social Welfare 9 (2): 164–182. doi:10.1080/17496535.2015.1005550.

- Vosman, F., and A. Niemeijer. 2017. “Rethinking Critical Reflection on Care: Late Modern Uncertainty and the Implications for Care Ethics.” Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 20 (4): 465–476.10.1007/s11019-017-9766-1

- Walker, M. U. 2007. Moral Understandings: A Feminist Study in Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ward, L., and B. Gahagan. 2010. “Crossing the Divide between Theory and Practice: Research and an Ethic of Care.” Ethics and Social Welfare 4 (2): 210–216.10.1080/17496535.2010.484264

- Wilson, E., A. Kenny, and V. Dickson-Swift. 2018. “Ethical Challenges in Community-based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review.” Qualitative Health Research 28 (2): 189–199.10.1177/1049732317690721

- Woelders, S., T. Abma, T. Visser, and K. Schipper. 2015. “The Power of Difference in Inclusive Research.” Disability & Society 30 (4): 528–542.10.1080/09687599.2015.1031880