ABSTRACT

Participatory Action Research (PAR) is often applauded for creating a more egalitarian relationship between researchers and research participants. Nonetheless, PAR studies, particularly those involving young people, have been critiqued for their claims about its benefits, particularly the assertion that PAR is ‘more’ empowering and/or morally and ethically ‘better’ than other research approaches. At the core of these critiques is discussion of the issue of power and the assertion that the very power structures that PAR researchers hope to deconstruct may be reinforced if they do not take measures to address the various power hierarchies that can emerge during the conduct of PAR. Drawing on a PAR study involving the participation of 12 separated young people in Northern France, this paper documents the use of a Structured Ethical Reflection (SER) framework to guide a critically reflective process. Researcher acknowledgement of power and privilege led to the implementation of approaches that supported greater participant engagement and ownership of the research. The SER not only enabled the identification of emergent power asymmetries, but also supported the development of strategies that aimed to address ethical dilemmas as they arose during the research process.

Introduction

Participatory Action Research (PAR) is a collective, self-reflective form of inquiry founded on an egalitarian relationship between the researcher(s) and research participants (Baum, MacDougall, and Smith Citation2006; Swartz and Nyamnjoh Citation2018). The approach permits a contextualised understanding of young people’s social worlds (Save The Children UK Citation2001) while supporting them to engage in ‘identifying problems in their own lives or communities, collecting and analysing data to understand the problems, and advocating for changes based on their evidence’ (Ballonoff Suleiman et al. Citation2019, 3). PAR is an asset-based approach that recognises and values young people as active agents within existing political, economic and social contexts (Brydon‐Miller and Maguire Citation2009; Cammarota and Fine Citation2010; MacDonald Citation2012). Through PAR, the knowledge produced by youth is valued and can be mobilised to guide social action (Chen, Poland, and Skinner Citation2007).

A growing body of literature suggests that young people derive benefits from engaging in PAR. For example, it is claimed that PAR enables youth to develop strategic thinking capabilities; that PAR engagement enhances health, education and development and fosters relationships with adults, potentially engendering a sense of empowerment (Ballonoff Suleiman et al. Citation2019; Cammarota and Fine Citation2010). PAR has been found to encourage critical consciousness which can, in turn, support young people to engage in dialectic reflection, to analyse challenging or unjust conditions and to act to mobilise change (Begum Citation2014; Watts, Diemer, and Voight Citation2011). Since PAR methodologies can be tailored to the needs of the participants, PAR can also enhance the validity, authenticity, and relevance of research (Ponciano Citation2013; Swartz and Nyamnjoh Citation2018).

Through PAR, researchers can recognise and also address ‘hidden’ power inequalities by developing collaborative partnerships with communities of young people to produce local knowledge. However, as Dona (Citation2007) asserts, PAR can also potentially reinforce existing power hierarchies; rightly questioning the assumption that transformations in power relations arise by simply involving beneficiaries in the research process. In other words, merely involving individuals in knowledge production does not guarantee that power hierarchies are addressed during, much less eliminated from, the research process. Moreover, assumptions about the benefits of involvement also largely ignore the uses and control of knowledge in influencing critical consciousness (Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2015) as well as the structural factors that shape the social, political, and historical conditions that impact on knowledge development (Janes Citation2016).

Some PAR studies have been critiqued for their far-reaching claims about its benefits, particularly the assertion that PAR is ‘more’ empowering and/or morally and ethically ‘better’ than other research approaches (Holland et al. Citation2010). As Dona (Citation2007) points out, participants may feel anything but empowered and, instead, feel overwhelmed or discouraged as they gain increased understanding of the struggles they face. Particularly when research involves the participation of children and/or young people, some researchers may claim that their research is ‘empowering’ despite the fact that the research process was highly managed or largely controlled by the researcher (Holland et al. Citation2010). Other PAR researchers have theorised agency and power as attributes that children and young people can ‘have’, be ‘given’ or ‘enabled’ by a researcher(s) (Holland et al. Citation2010). Importantly, if participants are excluded from processes related to decision-making, data analysis and/or action plan development, PAR studies can potentially manipulate community participation by merely following an agenda decided a priori by the researcher (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014). Finally, although in PAR, researchers do not assume an objective or neutral stance (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014), they have, at times, conceptualised power as repressive and as something ‘known’ to the researcher, thereby ignoring hidden power dynamics (Holland et al. Citation2010).

Drawing on a PAR study involving the participation of 12 separated young people in Northern France, this paper documents the use of a Structured Ethical Reflection (SER) framework to guide a critically reflective process and as a strategy to ensure that the nuances of power were recognised, questioned and addressed throughout the research process. The paper aims to contribute to ongoing discussion and debate about how PAR researchers can address power differentials within the research process, particularly in studies involving the participation of young people. We start by providing an overview of the context in which the study was undertaken and also outline the approach taken to participant recruitment, data collection and the analysis of data.

A PAR study with separated young people

Recent years have seen the gradual emergence of research investigating the situations and needs of separated children in several European countries, including Ireland (Horgan and Ní Raghallaigh Citation2019; Sirriyeh and Ní Raghallaigh Citation2018), Finland (Korkiamäki and Gilligan Citation2020), Italy (Rania, Migliorini, and Fagnini Citation2018), Greece (Buchanan and Kallinikaki Citation2020; Digidiki and Bhabha Citation2018), Belgium (De Graeve, Vervliet, and Derluyn Citation2017; Derluyn Citation2018), the UK (Chase Citation2013; Chase and Statham Citation2013; Thommessen, Corcoran, and Todd Citation2017), Slovenia (Sedmak and Medarić Citation2017), and Sweden (Çelikaksoy and Wadensjö Citation2017; Herz and Lalander Citation2017). However, the French literature on separated children has focused primarily on services and related debates about how to provide appropriate care, based on the perspectives of individuals within professional and government institutions (for example, Cheval Citation2019; Nincheri, Titia Rizzi, and Radjack Citation2019; Cheval, Guzniczak, and Vella Citation2019). Consequently, there is currently a paucity of research on separated children’s experiences of the transition to adulthood in France and understanding of these young people’s life experiences is extremely limited. This is despite repeated calls for research on aged-out separated young people that addresses the societal and structural constraints that may potentially influence how they negotiate the transition to adulthood (Healy Citation2018; Roberts et al. Citation2017).

A PAR study was designed to examine the experiences of separated children living in Northern France during the transition to adulthood. Separated children were defined as those living outside their country of origin without their parents or customary or legal guardians (Smith Citation2009). Once they turn 18, these young people typically face a loss of protections and have limited access to a range of services, including accommodation, welfare and psychosocial support (Bravo and Santos-González Citation2017; Chase and Statham Citation2013; Hek, Hughes, and Ozman Citation2012; Ní Raghallaigh Citation2007; Robinson and Williams Citation2015). At the study’s core was an acknowledgement of separated young people’s agency but, equally, of the structural constraints that they may confront as they transition to adulthood. PAR was the chosen methodological approach because of its capacity to provide detailed insight into the perspectives and experiences of separated young people while also supporting them to play an active role in the research process (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014).

The study’s participants

The research aimed to recruit young people who presented to child protection services as unaccompanied minors upon their arrival in France. In countries throughout Europe, a number of terms are used to describe children who migrate alone or without a parent(s) or guardian(s), including separated children, unaccompanied minors, separated asylum seeking children, and unaccompanied refugee children. Throughout this paper, the terms separated or aged-out young people are used interchangeably (Duvivier Citation2009) to describe separated youth who, at the time they participated in the research, were aged 18–24 years.

To create a rich picture of the transition period, both young people who had, and had not, been legally recognised as unaccompanied minors were included in the study. All of the study’s young people were recruited from the départementFootnote1 ‘Nord’ near the Belgian border, a region where large numbers of separated children have arrived since the late 1990s (Duvivier Citation2008; Frechon and Marquet Citation2017), generating intense local debate about policy and service responses to separated children. To be eligible for participation, young people had to be: a) aged between 18 and 24 years; b) have arrived in France before the age of 18 without their parent(s) or a guardian(s); and c) feel comfortable communicating in English or French.

Sampling and recruitment

Participant selection was guided by a sampling strategy that aimed to generate a diverse sample of youth who fit the study’s eligibility criteria. Recognising the complexity of accessing separated young people – a typically hard-to-reach population – and drawing on the first author’s pre-established contacts in the migrant youth services community,Footnote2 snowball sampling was the preferred approach to participant recruitment (Roschelle et al. Citation2018).

In France, unaccompanied minors typically arrive from Francophone Sub-Saharan African countries (Dambuyant Citation2019), including Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali (61% in 2017 and 2019; 67% in 2018) (Mission Mineurs Non Accompagnés (MMNA) Citation2020), and a majority of unaccompanied minors in France are males aged 16–17 years (Mission Mineurs Non Accompagnés (MMNA) Citation2020). Reflecting these trends, the final sample comprised 12 young people, including one female and 11 male participants; all were aged 18–24 years and had arrived in France from Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa as separated children. These young people had arrived as unaccompanied minors between the age of 15 and 17 years, approximately two to four years prior to their participation in the research. Recruitment focused on developing strong rapport with participants and was carried out incrementally between October 2018 and June 2019. To develop rapport and provide young people with detailed information about the research, seventeen individual recruitment meetings were held with potential participants. When a young person indicated an interest in participating in the research, s/he was invited to meet to discuss the research further and was provided with study information sheets and consent forms. Prospective participants were also provided with opportunities to ask questions about the research during these meetings. The study only included young people who gave their full verbal and written informed consent to participate in the research.

Data collection and analysis

In PAR, the use of several methods is recommended to generate a deeper, more authentic exploration of participants’ experiences and, through the triangulation of data, to overcome the limitations associated with the use of a single method (Kaukko Citation2015). Qualitative methods, particularly interviews and discussion-based workshops, are the most common data collection methods used in PAR (Howard and Somerville Citation2014). Interactive and participative methods are also popular in PAR studies because they promote participant involvement in, and ownership of, the research process (Swartz and Nyamnjoh Citation2018).

Data were collected through the conduct of 12 in-depth interviews and one participatory group project comprising three non-formal education workshops and 16 informal group meetings. The participatory group project aimed to encourage and foster trust and rapport (MacDonald Citation2012), with the aim of supporting young people to have an active role in the research (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014) while also supporting the development of a detailed understanding of the daily lives and experiences of the study’s participants. Deemed more appropriate than group contexts for the investigation of sensitive topics and delving deeper into participant responses (Mack et al. Citation2005), the in-depth interviews aimed to validate, and expand on, the data garnered from the group project (Busza and Schunter Citation2001; Swartz Citation2011). Twenty-four one-to-one informal encounters also occurred during the fieldwork phase of the project, including meetings with young people for coffee and walks, travelling to events together, and talking by text or telephone. These encounters aimed to strengthen researcher-participant rapport and to ensure that the research process was relevant to the individual needs of participants; they also helped to capture change in the everyday experiences and situations of participants over time and provided a space for young people to share more intimate experiences and perspectives (Holland et al. Citation2010). All data collection was conducted by the first author, who maintained a detailed journal documenting her reflections on and observations of these encounters, also recording emerging or new information on the everyday experiences of the young people. provides an overview of this PAR study’s process and data collection methods.

Table 1. An overview of the PAR process and the study’s data.

As documented in , the study’s data included audio-recordings, memos, journal entries and outputs from the group project, including short stories written by the young people, the production of a short film, a PowerPoint presentation, drawings, flipcharts and a selection of post-it notes. Audio recordings of the 12 in-depth interviews, as well as the recordings of workshops and certain social actions, were transcribed verbatim. The social actions, which were audio-recorded and transcribed, included two peer interviews and one policy conference workshop. The audio from the short film was also transcribed. Data analysis was iterative, commencing during the data collection process (Kaukko Citation2015) and included many cycles of action-reflection. Thematic analysis was selected to guide the analysis because of its flexibility and ability to support a complex interrogation of rich qualitative data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Rather than aiming to fit into pre-determined frameworks, thematic analysis aligns with a data driven approach (O’Malley Citation2018) and the action research orientation of listening, dialogue, and action.

The analysis was conducted in four phases (see ) and, during each of these phases, a process of open coding, followed by the identification of themes, was undertaken. NVivo was used as a data management tool. This phased approach to data analysis and theory building not only supported participant engagement, but also enabled the analysis of an extremely large volume of data generated from diverse sources (Jackson Citation2008). Phase 1 involved an exploration of emergent dilemmas and themes with the study’s participants arising from the transformation of personal concerns and experiences into public issues within the group (Genat Citation2009). During this phase, participants were given the opportunity to challenge the ways in which their experiences were represented and interpreted by the researcher through the provision of regular feedback to them during each workshop (Genat Citation2009). The emerging themes were then revised and redefined as necessary. During Phase 2, initial theory building commenced through the generation of initial codes, supported by the identification of emergent themes in the data. At each group meeting, the themes and interpretation of data were informally discussed with participants, who provided feedback by verifying, clarifying, or rejecting the researcher’s interpretation. Following this, the themes were revised, redefined and finalised during Phases 3 and 4 of the research process.

A collective critical reflection

Research conducted by Chase (Citation2009) on the emotional well-being of separated asylum-seeking youth in the UK placed strong emphasis on the impact of hidden power dynamics on young people, highlighting that research to date has often failed to fully consider the experiences or perspectives of separated youth who – repeatedly labelled as vulnerable – have, more often than not, been depicted as passive agents and ‘the other’. To address knowledge hierarchies such as those highlighted by Chase (Citation2009), the current study was committed to including aged-out separated young people in the construction of knowledge; an aim that was operationalised by endeavouring to create ‘open communicative spaces’ whereby all involved could partake in the critical thinking that informs inquiry (Kemmis Citation2008). Importantly, this approach recognised that authentic participation cannot be achieved by simply ‘climbing a ladder’Footnote3 but rather by aspiring, from the outset, to engage young people as full partners in the research process (Brydon-Miller and Kral Citation2019). The research process therefore aimed to support the meaningful engagement of participants, while also striving to capture the interplay of societal contradictions and structural (pre-)determinations that may limit their involvement (Chase et al. Citation2019).

Development studies scholars have called upon PAR researchers to tackle the influence of power structures on knowledge development by engaging with power issues as they emerge during the conduct of participatory research (Cornwall and Brock Citation2005; Hickey and Mohan Citation2004). Underpinned by a commitment to acknowledging and taking measures to mitigate against the manipulation of knowledge, critical reflection on the knowledge power hierarchies at play within the research process was deemed necessary. To this end, Paulo Freire’s seminal work on critical pedagogy was drawn upon as a lens through which to explore the power struggles and domination frequently embedded in the construction of knowledge (Freire Citation2005). According to Freire, a ‘culture of silence’ develops from the societal contradictions and power imbalances that leave marginalised populations unaware that they face limitations when exercising their right to consciously participate in societal transformation (Freire Citation2005). To overcome this ‘culture of silence’, individuals must undergo a process of ‘conscientisation’, which involves recognising power imbalances and societal contradictions, perceiving the reality of the ‘oppression’ as a limiting situation that can be transformed and, through this process of critical thinking, using the new understanding of reality as the motivating force for liberating action against the obstacles identified (Freire Citation2005). Freire understands the process of critical reflection as an action; in other words, the development of consciousness is itself an action (Crotty Citation1998), with critical reflection working to produce ‘theory-in-action’, whereby theory and action have a mediating dialogue or ‘praxis’ (Kaukko Citation2015, 49). As critical reflection occurs, further action takes place, creating what Freire terms ‘transformative power’ (Baum, MacDougall, and Smith Citation2006). The process of conscientisation cannot occur by finding solutions for people and is rather understood to occur in solidarity with people by way of dialogue (Crotty Citation1998).

Encouraging a process of conscientisation

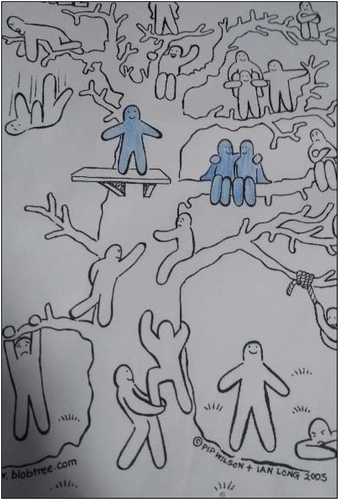

Underpinned by these principles and aiming to go further than simply including separated young people in the research, this PAR study aimed to support a process of conscientisation. Through a blend of methodologies and epistemologies, it endeavoured to encourage participants to be ‘critical’ and to investigate the consequences of different perspectives, systems and practices (Jordan Citation2009). All separated young people involved in the research process were invited to participate in a process of dialogue, critical reflection and action (Reason and Bradbury Citation2001) and encouraged to critically reflect on, and act against, real and apparent injustice, rather than for an intangible ideal of what should be just or rational (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2015). Collective reflections took place during the participatory group project, non-formal education workshops and informal group meetings. For example, during the first workshop, participants were provided with a notebook and invited to create a learning journal of their experiences of the research process. However, participants did not demonstrate interest in pursuing this activity. For this reason, during the collective meetings, participants’ learning experiences were instead collected through interactive evaluations, including colouring in ‘Blob trees’, which the participants then discussed in a group. presents a ‘Blob tree’ created by one participant at the first workshop evaluation, which he explained illustrated ‘the beginning of the research process’, adding that ‘we have to continue to develop [the project]’. A WhatsApp platform was used to support participants to document their experiences of, and provide feedback on, the research process. For example, in November 2018, one of the young people felt that there was not adequate engagement with the group project by other participants and asked them to ‘please fight for our project’. Participants also shared more intimate reflections and learning during the individual interviews and in the context of individual encounters with the researcher.

Image 1. A participant’s ‘Blob tree’ at the evaluation in workshop 1 (Wilson and Long Citation2005).

Group project participants were encouraged to create collective social actions where they decided, collectively, that the aim of the actions was to make visible the realities and experiences of the transition to adulthood. With this aim in mind, the group developed three awareness raising actions, namely: one PowerPoint presentation on the experiences of separated children in Northern France that was presented at a local festival on migration; one workshop, which made recommendations for durable solutions for children in migration in Europe and was delivered at an international policy conference; and one short film on the challenges faced by separated children when they arrive in France, which was presented at two academic events. The process of developing actions provided opportunities for participants to collectively reflect on the inequalities, structural barriers and social injustices confronted by separated young people, while the actions implemented encouraged a supplementary process of conscientisation with the wider community by including the perspectives of stakeholders (youth, social workers, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), academics, politicians, general public, etc.) who were invited to critically reflect on these issues with the young people. These initiatives also supported the young people to contest power structures by creating awareness of the challenges they faced and bringing these issues to debate within the wider community. For example, three young people represented the group members at an international policy event attended by high-level institutional actors, where they contested the structural inequalities experienced by separated youth at the age of 18 years.

Acknowledging power and privilege

The research was designed to support a participant-centred research process and to encourage participants to engage with the construction of knowledge. However, several specific steps were taken to address researcher power and privilege. These efforts were underpinned by a rejection of a solely repressive understanding of power, which suggests that power can be simply ‘given up’ by the researcher to less powerful participants (Janes Citation2016, 75); a perspective that ignores researcher privilege and risks generating and supporting the very power hierarchies it aims to circumvent (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014; Janes Citation2016).

A critical examination of power, privilege and knowledge construction is central to the conduct of research involving the participation of young people who may be labelled and understood as marginalised, vulnerable, and relatively powerless (McTaggart Citation1994). Foucault’s microphysics of power provided a useful frame through which the power hierarchies that appear within, and as a result of, the PAR processes can be acknowledged. Through this framework, power was recognised as located within the discourses, practices, and institutions inherent in all social relations (Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2015). It was acknowledged that power is not only exerted by one person over another but that it may be reinforced by the social relationships found within both external and internal research structures (Dona Citation2007). During the conduct of the research, it was therefore necessary to address the potential and, at times, less visible power plays found within the relationships formed during the research process (Gaventa and Cornwall Citation2015). For example, over the course of the research process, it became clear that there was a risk that a number of research participants may have been becoming overly reliant on the researcher’s support, giving rise to concerns that this could generate power asymmetries and lead a young person to feel obliged to continue his/her participation in the research. It was therefore important to take steps to avoid such power imbalances as they began to surface. Guided by Foucault’s framework on the microphysics of power, it was possible to question the unintentional spaces in which power may be present (Janes Citation2016).

While the microphysics of power model provides a framework or platform from which to mobilise an examination of power within social interactions, this conceptualisation does not account for the structural factors that shape the social, political and historical conditions that impact on knowledge development (Janes Citation2016). To ensure that the influence of such structural factors was considered throughout the conduct of the research, it was recognised that although power is dynamic, it is contextual, uneven, and inevitable; implicated in all spaces and positions. Particularly as the research progressed, the need to develop a safe space for dialogue and sharing – that would enable young people to address any perceived power ‘plays’ or dynamics – was recognised. To begin, the young people were invited to develop a ‘group agreement’ that addressed the functioning, type of communication and key principles of the group. Based on this agreement, the group’s functioning and progress was regularly reviewed by participants, who provided feedback on the research process and the role of both group members and the researcher. Throughout this process, it was acknowledged that researcher privilege cannot be removed or reduced, even if a researcher’s value system rejects oppressive systems and hierarchical practices (Janes Citation2016). Within a research process underpinned by such notions of power, it was possible to reflect upon the knowledge hierarchies produced and reproduced, including those claiming to be emancipatory. Tackling power dynamics within the research process in this way acknowledged the researcher’s positionality and the potential impact of this positionality on the relationships established with the study’s participants. To elucidate power and privilege, reflexivity and critical reflectivity were utilised during all stages of research process (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014).

A critical reflection on research practice

Reflexivity and reflectivity are commonly confused or conflated (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014). Fook (Citation1999) usefully distinguishes between reflexivity as a position and reflectivity as a process, while acknowledging that both work to complement each other. Reflexivity involves recognising and acknowledging the influence of the researcher’s position within social, cultural and structural contexts (Fook Citation1999; Shaw and Gould Citation2001) and requires the development of awareness of the influence of those assumptions and beliefs that shape the researcher's judgment, decisions and behaviours over the course of the research process (Gonnerman et al. Citation2015; Etherington Citation2004).

The process of reflectivity complements reflexivity in the sense that, having considered the influence of researcher assumptions and actions, the researcher then begins to understand her/his position in relation to others and alters their practice accordingly (Fook Citation1999). The ‘performance’ of this reflective process required researcher reflection on the research process and the associated actions of the researcher (single-loop learning) and, closer to notions of reflexivity, necessitated reflecting on the underlying assumptions underpinning these actions (double-loop learning) (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014; Argyris Citation1976).

Action researchers use a range of methods for reflective practice, including journaling, memo writing, storytelling, and autobiographies (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Citation2014). Drawing insight from the action research literature on children and young people (Kaukko Citation2016; Blanchet-Cohen and Di Mambro Citation2015; Ponciano Citation2013), a number of strategies were used to encourage shifts in uneven power dynamics. Reflective journaling and memo writing were particularly helpful in that they supported researcher reflection upon various challenges as they emerged in the field (Streck and Holiday Citation2015). With the aim of developing a culture of openness, participants were invited to provide feedback on the research process, while peers and gatekeepers provided support and advice on different issues and challenges that arose over time (including, for example, ethical issues, finding access routes to participants, adapting methods to better match young people’s perspectives). This approach to reflective practice led to the modification of data collection methods to better reflect participants’ preferences, which simultaneously enhanced the validity, authenticity and relevance of the research (Swartz and Nyamnjoh Citation2018; Ponciano Citation2013).

Guiding principles for reflection

The Structural Ethical Reflection (SER) model was incorporated into the research process to support reflective practice and to ensure that research decisions were underpinned by ethical principles and values. Originally designed with the aim of operationalising covenantal ethics, and echoing the underpinnings of feminist, communitarian and virtue approaches, the SER epistemological standpoint focuses strongly on social justice, the distribution and manipulation of power, and the co-generation of knowledge (Brydon-Miller, Rector Aranda, and Steven Citation2015). Covenantal ethics is ‘an ethical stance enacted through relationship and commitment to working for the good of others that is an inherent component of action research’ (Brydon-Miller Citation2009, 244). According to Brydon-Miller, Rector Aranda, and Steven (Citation2015, 598), virtue approaches to ethics focus on ‘the qualities of individuals themselves and the ways in which they are expressed in action’. Through the SER, it is possible to define a set of values that are used to guide actions, thus reframing research ethics as not only following specific ethical protocols towards personal reflection and dialogue on the complex ethical issues that researchers face. SER values include ‘a respect for people and for the knowledge and experience they bring to the research process, a belief in the ability of democratic processes to achieve positive social change, and a commitment to action’ (Brydon-Miller, Greenwood, and Maguire Citation2003, 15). Building on the ethical considerations addressed during the formal institutional ethical review process,Footnote4 SER aimed to ensure that all decision-making was guided by a key value system that would enable a fuller consideration of the complex ethical implications and challenges as they emerged, including power dynamics during all stages of the research process.

Using the SER as a primarily first-person process, the ethical values deemed central to researcher practice were identified. Of more than 60 ethical values, 14 key themes that represented the researcher’s core principles were established (Stevens, Brydon-Miller, and Raider-Roth Citation2016). Aiming to include the participants in the SER process, the SER remained unfinished until after the participatory group project began. During the early stages of the group project, a group agreement was developed to guide the work of the project, addressing the key practical, methodological, and ethical aspects of the research process. This agreement comprised several key principles and values (including, for instance, respect, inclusivity, solidarity, support, etc.), which were incorporated into the themes guiding the SER principles. Seven core principles, presented in , were chosen to guide reflection and decision-making during the research process. Developing a SER grid was the final step in the SER process. The grid was flexible and comprised questions that permitted the incorporation of the seven core values into each stage of the research process, with certain sections of the grid containing several questions that aimed to promote critical, ethical reflection throughout the research process.

Table 2. The seven core ethical principles guiding the research process.

An example of a SER guided reflection

The power of the researcher in the research process could not be denied in terms of the influence exerted by her during the initiation, implementation and conclusion of the project, including, for example, the fact that the institutional ethical review process precluded young people’s involvement in the initial design phase of the project. Power imbalances also emerged in the field because of the researcher’s privilege and positionality. During the course of data collection, for example, the first author sometimes found it difficult to navigate her ‘place’ in the research process; struggling at times to remain in the ‘facilitator’ role and sometimes becoming frustrated and questioning the dynamics of the group, which had become increasingly informal as the process advanced. The following journal entry, which was written after an informal group meeting in February 2019, captures some of these anxieties and a perceived need to exert greater control over the work arising from these meetings.

I was really exhausted afterwards [after the informal group meeting] but also thought about the fact that we are not getting a lot done. Many participants couldn’t attend and if felt like we didn’t get much work done during the meeting. However, we chatted about a lot of issues. I’m wondering about the atmosphere, perhaps it is a little too relaxed to get work done? And I am questioning how all of this might be managed in the future. Perhaps it would help if we got someone to provide support with the short films? We will have to see but, at the same time, it [the group work] is positive. I think it would be good to revisit some of the themes we talked about previously to support ongoing learning from the process. [Journal excerpt, 17 February 2019]

While such feelings of frustration were not explicitly voiced by the young people, a number did talk about feeling disappointed or annoyed during evaluations of their learning experience throughout the research process. For example, one young person became frustrated about the poor timekeeping of other group members. This participant discussed this issue with the group members and they collectively agreed changes aimed at improving timekeeping.

Journaling in this manner was the first step in the reflective process which, subsequently, went on to incorporate a Structured Ethical Reflection guided by the SER grid. The grid acted as a compass to ensure that the values underpinning the research process remained at the core of decision-making. In this example, considerable time was subsequently invested in reflecting on several questions contained in the SER grid. Many of these related to the theme of ‘inclusiveness’, including:

Is the process participant-led?

Is adequate space being created to ensure that participants’ needs are met?

Does the researcher need to step back and leave the participants to figure things out?

What is the role of the research and does the researcher’s position need to shift?

Through this process of reflection, the researcher realised that her struggle with different roles in the context of PAR was a product of her attempts to account for, manage, and control her subjectivity within the research process, linked to anxiety about ‘separating’ her different ‘selves’ (understood, at the time, as roles) (Heshusius Citation1994). By reflecting on the research process, questions were asked about whether these different ‘selves’ could or should in fact be controlled and managed; and if controlling them would help to shift power differentials within the research process. Gradually, the realisation emerged that to become embedded in the research process and truly understand the lives of the young people, the researcher must ‘let go’, if even temporarily, and shift to a state of complete attention. According to Heshusius (Citation1994), the process of ‘participatory consciousness’ involves the disappearance of the ‘self-conscious “I”’ and the development of awareness of a ‘deeper level of kinship between the knower and the known’, which requires an ‘attitude of openness and receptivity’. Heshusius (Citation1994, 18) explains the processes of participatory consciousness as ones where:

[R]eality is no longer understood as truth to be interpreted but as mutually evolving. The issue is not to define levels of completeness of merging, or of interpretation, as those who speak the metaphors and language of objectivity and subjectivity would want us to do, but to foster a participatory quality of attention. The question is not whether we have “reached” something but whether we can let go of something.

As the research progressed, rather than considering her different roles, the researcher began to practice a process of ‘inactive action’, which required ‘letting go’ and focusing only on being with the participants. Participants were encouraged to continue to engage with the research in their own way and at their own pace, which was increasingly recognised as critically important to gaining an authentic understanding of their lives. Planning was abandoned and attention directed to a far greater extent to listening, learning, and taking guidance from the study’s participants. Following this, the research process began to evolve more naturally and also supported meaningful participant engagement to a greater extent, including enabling the creation of informal spaces where participants and the researcher ‘hung out’, reflected, chatted, cooked, and ate together.

As the research process evolved and became increasingly participant-led, the co-construction of knowledge became more deeply aligned with young people’s everyday realities. Subsequently, when analysis of the data generated from the reflective journals was conducted, it became apparent that, despite early researcher concerns about inefficiency and a perception of needing to control, a process of ‘letting go’ facilitated the creation of environments of active participation, sharing and support which, in parallel, generated rich data. When chatting informally and ‘hanging out’, various topics arose naturally in conversation – without prompt – and these were discussed in great detail. In addition to providing a wealth of data and background information, these discussions supported the identification of key themes and also helped to ensure that the data were correctly interpreted. Emergent themes, as they developed during the data collection process, included interdependence, the interplay of structure and agency, and the notion of ‘wayfaring’ transitions (Wood Citation2017). Perhaps significantly, despite the emphasis frequently placed within care and aftercare services on autonomy at the age of 18 years (Frechon and Marquet Citation2017), the young people expressed a desire for a state of ‘interdependence’ that would better acknowledge and incorporate the role of their social support networks as they transitioned to adulthood. The interplay of structure and agency was strongly apparent in the lives of the young people, both before and during their transition to adulthood.

The guided process of critical reflection, as well as the researcher’s release of role-related concerns and the abandonment of a felt need to manage and control distance in relation to the participants, facilitated and encouraged a participant-led process which, otherwise, may have limited the power held by the participants and also potentially compromised accurate representations of the young people’s realities. Guided by the SER grid, the researcher learned to ‘go with the flow’, to trust the process and, most importantly, to trust the participants. Put differently, the researcher began to understand ‘the messiness, the nonlinear nature of learning, that is transformative: which turns our taken for granted assumptions upside down and enables us to see and act differently and restructure our relationship to the world’ (Weil Citation1998, 38). It also became clear that, in a PAR research process, researchers must strive to continuously address their preconceptions and prejudices and strive to create processes that work to ensure that the researcher remains committed to the values and philosophies guiding the research.

Conclusion

As discussed early in this paper, while a PAR approach can be beneficial to both the researcher and young people engaging with the research, a myriad of potential ethical and methodological challenges are likely to arise when conducting participatory research, particularly when researching marginalised populations such as separated young people. It is therefore critically important that researchers take steps that support them to acknowledge and address the power hierarchies that can potentially arise during the PAR process (Dona Citation2007). PAR researchers working with marginalised youth need to not only involve young people in research, but must go further to include them in the construction of knowledge (Reason and Bradbury Citation2001) and encourage them to engage with a process of dialogue, reflection and action with each other and the wider public. PAR researchers must also anticipate the practical and ethical implications of their research and ensure reflexive and critical reflective awareness of the emergence and interplays of power in the research process (Holland et al. Citation2010). By failing to do so, they run the risk of reinforcing the very power structures they work to deconstruct and may, albeit inadvertently, reinforce norms about how young people should behave, and exclude those who do not conform to these norms (Gallagher Citation2019).

Drawing from a PAR study with separated young people, this paper has documented the use of guided reflexivity and critical reflection as a strategy that aimed to ensure that the power dynamics that emerge in the research process were acknowledged and addressed. While, as action researchers, we are taught to expect the unexpected, the adoption of a Structured Ethical Reflection can support preparation for, and the development of, strategies that address the (sometimes) unexpected and complex ethical challenges that are likely to arise throughout the PAR process (Brydon-Miller, Rector Aranda, and Steven Citation2015). The Structured Ethical Reflection process described in this paper does not claim to be the only mechanism that might be useful to address researcher power; rather, we suggest that SER encouraged researcher awareness of actions, positionality and privilege and supported reflection on the extent to which researcher actions shape participant-led research (Brydon-Miller, Rector Aranda, and Steven Citation2015). As outlined, researcher reflection, alongside the participatory group’s core values and the guidance of the SER grid, enabled the implementation of strategies – including ‘inactive action’ – aimed at addressing power imbalances as they arose. This, in turn, enabled researcher adherence to the central aim of the research, which was to support and encourage a participant-led research process.

By documenting a critical reflective process, this paper has provided insights for PAR researchers working with marginalised youth aimed at supporting reflection on power asymmetries as well as the strategies that can be used to tackle unforeseen ethical dilemmas. Future studies could contribute by considering the benefits and challenges of approaches, including SER, that aim to encourage collective and individual critical reflection in the conduct of PAR with young people.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all of the young people who were so generous with their time and demonstrated enormous dedication and commitment to the research process. We also want to thank our colleagues, friends, partners and advisors in France, Ireland and internationally, who supported this research, particularly our colleagues at the School of Social Work and Social Policy, the Trinity Research in Childhood Centre (TRiCC), the Children’s Research Network (CRN), the Centre lillois d’études et de recherches sociologiques et économiques (Clersé), Voices of Young Refugees in Europe, the Council of Europe Youth Department, the Network for Educational Action Research in Ireland (NEARI), Action Research Group Ireland (ARGI) and the Collaborative Action Research Network (CARN). Finally, we would like to acknowledge the funding provided by Irish Research Council under the Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship Programme and the Higher Education Authority Ireland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. France is divided into regions, département and district. Belonging to a region, the département is the second-level administrative division of France. There are 101 département in France.

2. The first author had several years’ experience of working with local organisations across the département ‘Nord’ on projects targeting separated children and migrant youth.

3. ‘See Arnstein (Citation1969), Hart (Citation1987), and Hart (Citation2008) for detailed discussion of ‘ladders of participation’.

4. Ethical approval for the conduct of the research was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, School of Social Work and Social Policy, Trinity College Dublin.

References

- Argyris, C. 1976. “Single-loop and Double-loop Models in Research on Decision Making.” Administrative Science Quarterly 21 (3): 363–375. doi:10.2307/2391848.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Ballonoff Suleiman, A., P. J. Ballard, L. T. Hoyt, and E. J. Ozer. 2019. “Applying A Developmental Lens to Youth-led Participatory Action Research: A Critical Examination and Integration of Existing Evidence.” Youth & Society 53 (1): 26–53. doi:10.1177/0044118X19837871.

- Baum, F., C. MacDougall, and D. Smith. 2006. “Participatory Action Research.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 60 (10): 854–857. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.028662.

- Begum, S. 2014. “Gonogobeshona.” In The SAGE Encyclopaedia of Action Research, edited by D. Coghlan and M. Brydon-Miller, 384–385. London: SAGE Publications.

- Blanchet-Cohen, N., and G. Di Mambro. 2015. “Environmental Education Action Research with Immigrant Children in Schools: Space, Audience and Influence.” Action Research 13 (2): 123–140. doi:10.1177/1476750314553679.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bravo, A., and I. Santos-González. 2017. “Menores extranjeros no acompañados en Espana: Necesidades y modelos de intervención.” [Asylum-seeking Children in Spain: Needs and Intervention Models] 26 (1): 55–62.

- Brydon-Miller, M., A. Rector Aranda, and D.M. Steven. 2015. “Widening the Circle: Ethical Reflection in Action Research and the Practice of Structured Ethical Reflection.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, edited by H. Bradbury, 596–607. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Brydon-Miller, M., D. Greenwood, and P. Maguire. 2003. “Why Action Research?” Action Research 1 (1): 9–28. doi:10.1177/14767503030011002.

- Brydon-Miller, M., and M. Kral. 2019. “Reflections of the Role of Relationships, Participation, Fidelity, and Action in Participatory Action Research.” Educational Action Research 28 (1): 98–99. doi:10.1080/09650792.2020.1704364.

- Brydon-Miller, M. 2009. “Covenantal Ethics and Action Research: Exploring a Common Foundation for Social Research.” In Handbook of Social Research Ethics, edited by D. Mertens and P. Ginsberg, 243–258. London: Sage Publications.

- Brydon‐Miller, M., and P. Maguire. 2009. “Participatory Action Research: Contributions to the Development of Practitioner Inquiry in Education.” Educational Action Research 17 (1): 79–93. doi:10.1080/09650790802667469.

- Buchanan, A., and T. Kallinikaki. 2020. “Meeting the Needs of Unaccompanied Children in Greece.” International Social Work 63 (2): 206–219. doi:10.1177/0020872818798007.

- Busza, J., and B.T. Schunter. 2001. “From Competition to Community: Participatory Learning and Action among Young, Debt-bonded Vietnamese Sex Workers in Cambodia.” Reproductive Health Matters 9 (17): 72–81. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(01)90010-2.

- Cammarota, J., and M. Fine. 2010. Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Çelikaksoy, A., and E. Wadensjö. 2017. “Policies, Practices and Prospects: The Unaccompanied Minors in Sweden.” Social Work & Society 15 (1): 1–16.

- Chase, E., and J. Statham. 2013. “Families Left Behind: Stories of Unaccompanied Young People Seeking Asylum in the UK.” In Family Troubles?: Exploring Changes and Challenges in the Family Lives of Children and Young People, edited by J. Ribbens McCarthy, CA. Hooper, and V. Gillies, 223–231. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Chase, E., L. Otto, M. Belloni, A. Lems, and U. Wernesjö. 2019. “Methodological Innovations, Reflections and Dilemmas: The Hidden Sides of Research with Migrant Young People Classified S Unaccompanied Minors.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (2): 1–17.

- Chase, E. 2009. “Agency and Silence: Young People Seeking Asylum Alone in the UK.” The British Journal of Social Work 40 (7): 2050–2068. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcp103.

- Chase, E. 2013. “Security and Subjective Wellbeing: The Experiences of Unaccompanied Young People Seeking Asylum in the UK.” Sociology of Health & Illness 35 (6): 858–872. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01541.x.

- Chen, S., B. Poland, and H. A. Skinner. 2007. “Youth Voices: Evaluation of Participatory Action Research.” The Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 22 (1): 125.

- Cheval, P., B. Guzniczak, and S. Vella. 2019. “Harmoniser pour mieux protéger.” Les Cahiers Dynamiques 74 (1): 42–49. doi:10.3917/lcd.074.0042.

- Cheval, P. 2019. “Regards croisés autour des mineurs non accompagnés.” Les Cahiers Dynamiques 74 (1): 66–76. doi:10.3917/lcd.074.0066.

- Coghlan, D., and M. Brydon-Miller. 2014. The SAGE Encyclopaedia of Action Research. London: SAGE Publications.

- Cornwall, A., and K. Brock. 2005. “What Do Buzzwords Do for Development Policy? A Critical Look at ‘Participation’, ‘Empowerment’ and ‘Poverty Reduction’.” Third World Quarterly 26 (7): 1043–1060. doi:10.1080/01436590500235603.

- Crotty, M. 1998. “Critical Inquiry: Contemporary Critics & Contemporary Critique .” In The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process, edited by M. Crotty, 155–177. London: SAGE Publications.

- Dambuyant, G. 2019. “Accueil et accompagnements socio-éducatifs des mineurs non accompagnés au foyer de l’enfance. Bouleversements des prises en charge, adaptation des pratiques et complexité des mesures de protection.” Empan 116 (4): 66–73. doi:10.3917/empa.116.0066.

- De Graeve, K., M. Vervliet, and I. Derluyn. 2017. “Between Immigration Control and Child Protection: Unaccompanied Minors in Belgium.” Social Work and Society 15 (1): 1–13.

- Derluyn, I. 2018. “A Critical Analysis of the Creation of Separated Care Structures for Unaccompanied Refugee Minors.” Children and Youth Services Review 92: 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.047.

- Digidiki, V., and J. Bhabha. 2018. “Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Unaccompanied Migrant Children in Greece: Identifying Risk Factors and Gaps in Services during the European Migration Crisis.” Children and Youth Services Review 92: 114–121. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.040.

- Dona, G. 2007. “The Microphysics of Participation in Refugee Research.” Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2): 210–229. doi:10.1093/jrs/fem013.

- Duvivier, É. 2008. “Du «Temps du déplacement» au «Temps de l’institution»: Analyse des trajectoires migratoires d’un groupe de mineurs isolés pris en charge dans un foyer socio-éducatif de la métropole lilloise.” La Migration des Mineurs Non Accompagnés en Europe, E-Migrinter 2: 196–206.

- Duvivier, É. 2009. “Quand ils sont devenus visibles … Essai de mise en perspective des logiques de construction de la catégorie de « mineur étranger isolé ».” Pensée Plurielle 21 (2): 65–79. doi:10.3917/pp.021.0065.

- Etherington, K. 2004. Becoming a Reflexive Researcher: Using Ourselves in Research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Fook, J. 1999. “Reflexivity as Method.” Annual Review of Health Social Science 9 (1): 11–20. doi:10.5172/hesr.1999.9.1.11.

- Frechon, I., and L. Marquet. 2017. “Unaccompanied Minors in France and Inequalities in Care Provision under the Child Protection System.” Social Work & Society 15 (2): 1–18.

- Freire, P. 2005. “Chapter 1.” In Pedagogy of the Oppressed: With an Introduction by Donaldo Macedo. Translated by M. Bergman Ramos. 30th anniversary ed., 43–71. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Gallagher, M. 2019. “Rethinking Children’s Agency: Power, Assemblages, Freedom and Materiality.” Global Studies of Childhood 9 (3): 188–199. doi:10.1177/2043610619860993.

- Gaventa, J., and A. Cornwall. 2015. “Power and Knowledge.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, edited by H. Bradbury, 465–471. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Genat, B. 2009. “Building Emergent Situated Knowledges in Participatory Action Research.” Action Research 7 (1): 101–115. doi:10.1177/1476750308099600.

- Gonnerman, C., M. O’Rourke, S.J. Crowley, and T.E. Hall. 2015. “Discovering Philosophical Assumptions that Guide Action Research: The Reflexive Toolbox Approach.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, edited by H. Bradbury, 675–680. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Hart, R. A. 1987. “Children’s Participation in Planning and Design.” In Spaces for Children, edited by C. Simon Weinstein and T.G. David, 217–239. Boston: Springer.

- Hart, R. A. 2008. “Stepping Back from ‘The Ladder’: Reflections on a Model of Participatory Work with Children.” In Participation and Learning, edited by A. Reid, B. Bruun Jensen, J. Nikel, and V. Simovska, 19–31. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Healy, D. 2018. A Qualitative Study Exploring the Transition of Aged-out Unaccompanied Minors (Uams) from Foster Care into Direct Provision (DP). Cork: Community-Academic Research Links, University College Cork.

- Hek, R., N. Hughes, and R. Ozman. 2012. “Safeguarding the Needs of Children and Young People Seeking Asylum in the UK: Addressing past Failings and Meeting Future Challenges.” Child Abuse Review 21 (5): 335–348. doi:10.1002/car.1202.

- Herz, M., and P. Lalander. 2017. “Being Alone or Becoming Lonely? The Complexity of Portraying ‘Unaccompanied Children’ as Being Alone in Sweden.” Journal of Youth Studies 20 (8): 1062–1076. doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1306037.

- Heshusius, L. 1994. “Freeing Ourselves from Objectivity: Managing Subjectivity or Turning toward a Participatory Mode of Consciousness?” Educational Researcher 23 (3): 15–22. doi:10.3102/0013189X023003015.

- Hickey, S, and G. Mohan. 2004. “Towards Participation as Transformation: Critical Themes and Challenges.” In Participation: From Tyranny to Transformation? Exploring New Approaches to Participation in Development, edited by S. Hickey and G. Mohan, 3–24. London: Zed Books.

- Holland, S., E. Renold, N. J. Ross, and A. Hillman. 2010. “Power, Agency and Participatory Agendas: A Critical Exploration of Young People’s Engagement in Participative Qualitative Research.” Childhood 17 (3): 360–375. doi:10.1177/0907568210369310.

- Horgan, D., and M. Ní Raghallaigh. 2019. “The Social Care Needs of Unaccompanied Minors: The Irish Experience.” European Journal of Social Work 22 (1): 95–106. doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1357018.

- Howard, Z., and M. M. Somerville. 2014. “A Comparative Study of Two Design Charrettes: Implications for Codesign and Participatory Action Research.” CoDesign 10 (1): 46–62. doi:10.1080/15710882.2014.881883.

- Jackson, S. F. 2008. “A Participatory Group Process to Analyze Qualitative Data.” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 2 (2): 161–170. doi:10.1353/cpr.0.0010.

- Janes, J. E. 2016. “Democratic Encounters? Epistemic Privilege, Power, and Community-based Participatory Action Research.” Action Research 14 (1): 72–87. doi:10.1177/1476750315579129.

- Jordan, S. 2009. “From a Methodology of the Margins to Neoliberal Appropriation and Beyond: The Lineages of PAR.” In Education, Participatory Action Research, and Social Change. International Perspectives, edited by D. Kapoor and S. Jordan, 15–28. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kaukko, M. 2015. “Participation in and beyond liminalities: Action research with unaccompanied asylum-seeking girls.” PhD., Oulu: University of Oulu.

- Kaukko, M. 2016. “The P, A and R of Participatory Action Research with Unaccompanied Girls.” Educational Action Research 24 (2): 177–193. doi:10.1080/09650792.2015.1060159.

- Kemmis, S. 2008. “Critical Theory and Participatory Action Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, edited by P. Reason and H. Bradbury, 121–138. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Kemmis, S, R McTaggart, and R. Nixon. 2015. “Critical Theory and Critical Participatory Action Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, edited by H. Bradbury, 452–464. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Korkiamäki, R., and R. Gilligan. 2020. “Responding to Misrecognition – A Study with Unaccompanied Asylum-seeking Minors.” Children and Youth Services Review 119: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105687.

- MacDonald, C. 2012. “Understanding Participatory Action Research: A Qualitative Research Methodology Option.” The Canadian Journal of Action Research 13 (2): 34–50.

- Mack, N., C. Woodsong, K. Macqueen, E. Namey, and G. Guest. 2005. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. North Carolina: Family Health International.

- McTaggart, R. 1994. “Participatory Action Research: Issues in Theory and Practice.” Educational Action Research 2 (3): 313–337. doi:10.1080/0965079940020302.

- Mission Mineurs Non Accompagnés (MMNA). 2020. “Rapport annuel d’activité 2019.” Online: Ministère de la Justice Direction de la Protection Judiciaire de la Jeunesse.

- Ní Raghallaigh, M. 2007. “Negotiating changed contexts and challenging circumstances: The experiences of unaccompanied minors living in Ireland.” PhD., Dublin: Trinity College Dublin.

- Nincheri, F., A. Titia Rizzi, and R. Radjack. 2019. “« Je suis sans papiers, donc je n’existe pas ». Filiation et affiliations impossibles des jeunes étrangers exclus de la protection de l’enfance.” Empan 113 (1): 82–88. doi:10.3917/empa.113.0082.

- O’Malley, S. M. 2018. “Motherhood, mothering and the Irish prison system.” PhD., Galway: National University of Ireland Galway.

- Ponciano, L. 2013. “The Voices of Youth in Foster Care: A Participant Action Research Study.” Action Research 11 (4): 322–336. doi:10.1177/1476750313502554.

- Rania, N., L. Migliorini, and L. Fagnini. 2018. “Unaccompanied Migrant Minors: A Comparison of New Italian Interventions Models.” Children and Youth Services Review 92: 98–104. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.024.

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury. 2001. Introduction. In the SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 1–10. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Roberts, H. M., H. Bradbury, A. Ingold, G. Manzotti, D. Reeves, and K. Liabo. 2017. “Moving On: Multiple Transitions of Unaccompanied Child Migrants Leaving Care in England and Sweden.” International Journal of Social Science Studies 5 (9): 25–34. doi:10.11114/ijsss.v5i9.2523.

- Robinson, K. I. M., and L. Williams. 2015. “Leaving Care: Unaccompanied Asylum-seeking Young Afghans Facing Return.” Refuge 31 (2): 85–94. doi:10.25071/1920-7336.40312.

- Roschelle, A. R., E. Greaney, T. Allan, and L. Porras. 2018. “Treacherous Crossings, Precarious Arrivals: Responses to the Influx of Unaccompanied Minors in the Hudson Valley.” Children and Youth Services Review 92: 65–76. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.050.

- Save the Children UK. 2001. Breaking through the Clouds: A Participatory Action Research (PAR) Project with Migrant Children and Youth along the Borders of China, Myanmar and Thailand. London: Save the Children UK.

- Sedmak, M., and Z. Medarić. 2017. “Life Transitions of the Unaccompanied Migrant Children in Slovenia: Subjective Views.” Dve Domovini/Two Homelands 27 (45): 61–76.

- Shaw, I., and N. Gould. 2001. “Inquiry and Action: Qualitative Research and Professional Practice.” In Qualitative Research in Social Work, edited by I. Shaw and N. Gould,158–178. London: SAGE Publications.

- Sirriyeh, A., and M. Ní Raghallaigh. 2018. “Foster Care, Recognition and Transitions to Adulthood for Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Young People in England and Ireland.” Children and Youth Services Review 92: 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.039.

- Smith, T. 2009. Statement of Good Practice. 4th ed. Brussels: Separated Children in Europe Programme.

- Stevens, D. M., M. Brydon-Miller, and M. Raider-Roth. 2016. “Structured Ethical Reflection in Practitioner Inquiry: Theory, Pedagogy, and Practice.” The Educational Forum 80 (4): 430–443. doi:10.1080/00131725.2016.1206160.

- Streck, D.R., and O. J. Holiday. 2015. “Research, Participation and Social Transformation: Grounding Systematization of Experiences in Latin American Perspectives.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, edited by H. Bradbury, 472–480. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Swartz, S., and A. Nyamnjoh. 2018. “Research as Freedom: Using a Continuum of Interactive, Participatory and Emancipatory Methods for Addressing Youth Marginality.” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74 (3): 11. doi:10.4102/hts.v74i3.5063.

- Swartz, S. 2011. “‘Going Deep’ and ‘Giving Back’: Strategies for Exceeding Ethical Expectations When Researching Amongst Vulnerable Youth.” Qualitative Research 11 (1): 47–68. doi:10.1177/1468794110385885.

- Thommessen, S. A. O. T., P. Corcoran, and B. K. Todd. 2017. “Voices Rarely Heard: Personal Construct Assessments of Sub-Saharan Unaccompanied Asylum-seeking and Refugee Youth in England.” Children and Youth Services Review 81: 293–300. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.017.

- Watts, R. J., M. A. Diemer, and A. M. Voight. 2011. “Critical Consciousness: Current Status and Future Directions.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2011 134: 43–57. doi:10.1002/cd.310.

- Weil, S. 1998. “Rhetorics and Realities in Public Service Organizations: Systemic Practice and Organizational Learning as Critically Reflexive Action Research (CRAR).” Systemic Practice and Action Research 11 (1): 37–62. doi:10.1023/A:1022912921692.

- Wilson, P., and I Long. 2005. “Blob Tree.” Accessed 16 September 2021. www.blobtree.com

- Wood, B.E. 2017. “Youth Studies, Citizenship and Transitions: Towards a New Research Agenda.” Journal of Youth Studies 20: 1176–1190. doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1316363.