ABSTRACT

Heritage is a highly malleable concept that is constantly in flux and whose substance and meaning are continuously being redefined by society. From such a dynamic perspective, it is inevitable that new approaches and practices have developed for dealing with heritage in the context of planned development. While most scholars acknowledge the existence of various heritage approaches, one of the major defining features is often neglected: their distinctive outlook on spatial dynamics. In this article, the shifting role and purpose of heritage conservation in Dutch spatial planning is analysed. A conceptual framework is introduced that frames three approaches to the planning treatment of heritage; the sector, factor and vector approach, respectively. Although these approaches have developed in a historical sequence, the new did not replace the old but rather gained ground amongst different actors. Thus, three quite different ways of treating the past in the present now coexist in Dutch planning practice. Although this coexistence can raise conflict, we argue that contemporary heritage planning does not call for a one-size-fits-all approach, but rather for a mixed-mode model.

1. Introduction

From the 1990s onwards, the discourse on heritage definition across Western European states has expanded progressively (Vecco, Citation2010). Heritage architect Julian Smith, for example, observes a paradigm shift towards a landscape-based approach that recognizes the dynamic relationship between historic objects and their broader environment and to the people who shape and use them (Smith, Citation2015). Accordingly, there is a growing recognition that the historic environment is an integral part of our cities and landscapes, rather than a world set apart (Fairclough, Citation2008). Because the cultural landscape is inherently dynamic, preservation can no longer be the main objective. Instead, ‘management of change’ seems to be a more suitable definition for current conservation activity (Fairclough & Rippon, Citation2002). In this context, there is a growing demand to link preservation activity more proactively with the spatial planning process. It is argued that the proactive role of spatial planning is best suited for combining the past with contemporary use to ensure the continued existence of heritage assets (Denhez, Citation1997).

Although a landscape-based approach has become more prominent in heritage theory since the 1990s, a more dynamic and holistic approach to heritage in planning is not that recent. Already during the late nineteenth century, there were suggestions of a wider scope and scale of looking at the meaning and management of heritage conservation. In the European context, people like John Ruskin, Camillo Sitte and Patrick Geddes developed ideas on the importance of a wider scope for heritage conservation (Veldpaus, Pereira Roders, & Colenbrander, Citation2013). They saw the city and its landscape as a living ecosystem and emphasized the need for conservation of urban structure and fabric (Choay, Citation1999). From this beginning, ‘the planning treatment of heritage has sought to protect broad areas of historic, aesthetic, architectural of scientific interest, rather than simply focusing on individual monuments’ (Labadi & Logan, Citation2016, p. 5). Especially during the post-war period, many European countries developed a (legal) system of spatial planning, in which attention was given to heritage management principles and practice (Ashworth & Howard, Citation1999). This development was accelerated by the internationalization of the debate about, and approaches to, the protection and conservation of heritage and the connection between heritage, development and sustainability (Pickard, Citation2002a).

Despite the fact that global policy concepts promoting the integration of planning and the historical built environment has been developing since the beginning of the twentieth century, a gap can be observed between these concepts and their adoption in planning frameworks and practice. Indeed, whereas the work of heritage professionals and planners is infused by current ideas on heritage, they at the same time have to conform to the policies and regulations that are in force (Kalman, Citation2014). As is usual for official legislation, it reflects the established practice of the past rather than current developments (March & Olsen, Citation1989). Similarly, Pendlebury (Citation2009), reflecting on the heritage–planning nexus in the U.K., points out that despite the transformative potential of new ideas on, and conceptualizations of heritage, planning practice advanced on a more piecemeal basis. While the grand narratives of changing paradigms mentioned above seem to represent a helpful frame to understand and describe the evolution of heritage conservation as a discipline, the exact patterns of how it is practised in a planning context need to be analysed more carefully.

It is instructive to focus on the diversity of planning practices that have surfaced over time and currently prevail, and that cannot be simply captured by a universalized discourse. This paper therefore aims to take the specific case of the Netherlands as an example when it comes to answering the question of whether and how the planning treatment of heritage has changed and in how far the above-mentioned paradigms can be found in planning practice. Based on an analysis of half a century of Dutch spatial planning, this article argues that, in planning, three different approaches of dealing with heritage have evolved in the post-Second World War period: heritage as a spatial ‘sector’ (preserving heritage by isolating it from spatial development), heritage as a ‘factor’ in spatial dynamics (heritage as an asset and stimulus to urban and rural regeneration) and heritage as a ‘vector’ for sustainable area development (heritage determining the direction of spatial projects and developments).

We argue that, although these approaches evolved consecutively, the new did not replace the old but rather gained ground amongst different actors. Rather than observing a full-fledged paradigm shift towards a ‘new orthodoxy’, in which the classical, preservationist heritage approach is simply replaced by a more holistic, inclusive and dynamic approach, we use historic institutionalism theory to develop a more nuanced outlook which considers the various approaches of heritage in planning as layers, as parallel ways of working. This means that at least three quite different ways of treating the past in the present now coexist in current Dutch planning practice, which allows planners and heritage professionals to switch between approaches in line with the specific heritage context, scale and challenge at stake. This could of course also lead to (unresolved) tension between the different approaches. Current planning practice, however, does not call for a uniform mode that can be applied to all heritage issues, but rather for one that is capable of handling a variety of diverse approaches simultaneously, involving a variable mix of preservation, conservation and transformation.

Further unpacking the line of argumentation above, this paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we introduce concepts from historic institutionalism to analyse the expanding interrelationship of heritage and spatial planning in the Netherlands. We frame the Dutch experience into a conceptual framework that schematically models the increasingly interlinked nature of heritage conservation and the spatial planning process. We describe these linkages as the sector, factor and vector approach, respectively. Next, we reflect on the consequences of their coexistence in planning practice. Finally, the need for a multi-layered approach is discussed, as heritage planning is facing a diversity of new institutional and societal challenges. We argue that the key to contemporary heritage planning practice is the ability to realistically assess the potentials of a historic building, site or landscape in view of its broader context and apply different approaches accordingly.

2. The heritage–planning nexus: an institution-based view

Heritage conservation is a contested aspect of spatial planning. As Thompson (Citation2012, p. 11), citing R. Conroy, makes clear, ‘This is partly related to the complexity of identifying which aspects of the built environment should be retained for future generations, as well as reconciling conflicting options how to do this. It can also be difficult to establish definitive meanings for heritage value and significance, partly because the meanings of heritage have shifted from a narrowly aesthetic and historic understanding to one that includes social, economic and cultural components'. These shifting understandings are reflected in changing approaches to dealing with the past in planning practice. When exploring the process of heritage conservation in the Netherlands from theoretical initiation to its expression in planning practice, one can trace the threads from the origination of conservation ideas by innovative individuals, most notably, Victor de Stuers and Pierre Cuypers, to their adoption by voluntary groups identified with particular conservation aims (churches, castles, windmills, etc.), and the inclusion of conservation policies in national legislation and international convention (Kuipers, Citation2012).

Like many other European heritage systems, heritage conservation as applied through the Dutch planning system has late nineteenth-century roots (Ashworth & Howard, Citation1999). The radical transformations of the industrial city generalized the educated class to the presence of so-called ‘monuments’ and led to the formulation of a doctrine for their conservation, as well as the establishment of an official bureaucracy, legislative framework and professional experts to carry out the work (Choay, Citation1999). Parallel to developments elsewhere in Europe, a sophisticated infrastructure was created in the Netherlands to protect and preserve buildings as well as sites and broader areas (Pickard, Citation2002b). In the nineteenth century up to the Second World War, heritage conservation was developed as a discipline, which involved the documentation and listing of historical buildings, landscapes and archaeological remains. Public concern about the destruction of cultural resources and the need that was felt to document the material evidence being destroyed gradually led to protective measures and to some involvement at the national level. From the 1940s onwards, a basic legal framework was created, followed by the gradual development of a system of the care and protection of monuments.

The ‘Monumentenwet’ (Monuments and Historic Buildings Act) that came into force in 1961 provided the foundations for statutory protection and for a national ‘Register of protected monuments and historic buildings’. It furthermore linked the sectorial interest of heritage conservation with the laws and regulations of spatial planning by means of the instrument of the so-called ‘protected townscape’, enabling the conservation of larger areas. Protected townscapes were designated by the national government, whereupon the municipality was obliged to draw up a preservative zoning plan, which complied with the intentions of the designation. This means that in the Netherlands, for over 50 years, the establishment of the sectorial interest of heritage has been integrated into the laws and regulations of spatial planning, as well as the self-evident collaboration between central government (designation and listing) and municipalities (land-use planning). The heritage–planning nexus, as put forward by the 1961 ‘Monumentenwet’, has guided Dutch conservation practice for several decades. Since then, there have, of course, been other developments, which have caused the earlier centralized planning to become increasingly decentralized. The revised ‘Monumentenwet’ adopted by the Dutch Parliament in 1988 was an expression thereof as well as the 2009 ‘Modernization of Monuments Care’ or MoMo (Ministerie van OCW, Citation2009).

During the 1980s and 1990s, however, major changes took place, which transformed thinking about the conservation of historic buildings and landscapes into a much more dynamic concept of heritage (Janssen, Luiten, Renes & Rouwendal, Citation2014). This development reflected international trends in heritage definition, discursively widening the scale, scope and ambition of heritage conservation: from monumental objects (including townscapes) to a more holistic idea of heritage landscape, which also depicts immaterial aspects, and from expert-led authoritarian procedures towards more inclusive and participative community-led practices (Vecco, Citation2010). Early traces of this new thinking can be found in the Council of Europe’s Charter of the Architectural Heritage (1975) further developed in the 1985, ‘Granada convention’. It not only related to objects of exceptional quality, but also parts of cities and villages, and emphasized the role of spatial planning in maintaining the heritage and its social structure (Glendenning, Citation2013). Greater awareness of landscapes spread as a result of the 1972 international conference on the environment held in Stockholm, whereas the Brundtland Report introduced the idea of sustainable development. An extension of this concept some years later called for development to be attuned to and compatible with the cultural traditions and values of a community, opening the way for the identification of the cultural riches of the landscape ‘substratum’ and for an expanded notion of heritage including intangible aspects, as put forward by the Historic Urban Landscape approach (Bandarin & van Oers, Citation2012).

Set within this context of wider international discourses on heritage definitions, which contributed to broadening the concepts of heritage and its integrated conservation, post-war Dutch spatial planning has seen an infiltration of economic and social concerns subtly altering the way heritage is dealt with spatially. In fact, the post-war decades have followed a continuing series of responses and adaptations to the traditional preservationist ideal in heritage conservation. The interpretation of heritage as a ‘collection’ (in a repository) shifted towards heritage as ‘make over’ and, subsequently, as a ‘cultural representation’ (Grijzenhout, Citation2007). It is through these changing interpretations that heritage has been repositioned in spatial development: from a focus on (isolated) preservation to (integrated) conservation and, finally, a broader notion of heritage planning (Ashworth, Citation2011; Bosma, Citation2010). Furthermore, each interpretation can partly be characterized by the attitudes to spatial planning: from a rather sceptical position to a more hopeful one, and from a ‘culture of loss’ to a ‘culture of profit’, fostering social and economic development (Corten, Geurts, Meurs, & Vermeulen, Citation2014; Kolen, Citation2007).

These shifts in conceptualizations ‘in theory’, conventions and non-statutory government publications on heritage have been reflected in conservation efforts in planning practice through a process of institutionalization. New ideas slowly but gradually became codified in (national) policy documents, laws and treaties. These, in turn, structured the behaviour of actors in Dutch planning practice (Van der Cammen & De Klerk, Citation2012). Institutionalization in this respect is about making gradual changes in the understanding and acceptance of the role of heritage in the functioning of the present-day environment, and its routine application in planning practice. Indeed, a central tenet in the institution-based view on planning is that formal institutions (laws and regulations), informal institutions (norms, values and beliefs), and changes within these institutions over time shape behaviour and performance of actors in planning practice (March & Olsen, Citation1989).

Recent work on historical institutionalism focuses on patterns and processes of gradual institutional change (Sorensen, Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2013). As opposed to the punctuated equilibrium model of stability in between so-called ‘critical junctures’, this work stresses the idea that most institutional change may in fact occur through gradual processes of change. It starts from the premise that change is structured by existing conditions, interests and institutional structures. From this perspective, institutional transformation can be looked at as ‘constrained processes of adaptive change’ in which, as Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010) emphasize, power relations and positive feedback mechanisms are at work. Institutional continuity thus comes from the ongoing mobilization of, and by, those benefiting from the status quo. In their analysis of endogenous processes of institutional change, Mahoney and Thelen distinguish four possible modes of change, depending on the veto opportunities of the defenders of the status quo and of the level of discretion in implementation.

These modes range from layering to drift, and from displacement to conversion. The mode of ‘layering’ is about the creation of new policies without the elimination of the old. Sorensen (Citation2015, p. 29) argues that such layering occurs ‘in cases where strong veto players or points exist, it [then] may often be easier to add a new policy alongside an existing arrangement than to achieve formal reform or revision of the existing rules’. Indeed, the planning environment in which heritage conservation sits is held back by strong ideology and organizational structure. Over time, such layering of new policies over old ‘may transform the function and meaning of the older institution’. From a somewhat different perspective of the evolution of public governance in the Netherlands, Van der Steen, Scherpenisse, and van Twist (Citation2015) speak of a process of ‘sedimentation’ in which new governance approaches are not entirely replacing another, but instead superimposed over a previous approach. Transferred into the context of heritage planning, it is about a simultaneous presence of present and past, such as the restorations of the Italian architect Carlo Scarpa (1906–1978) do on the scale of the individual monument.

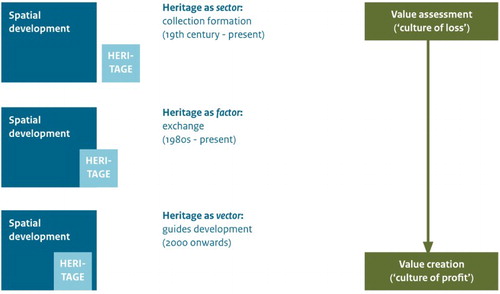

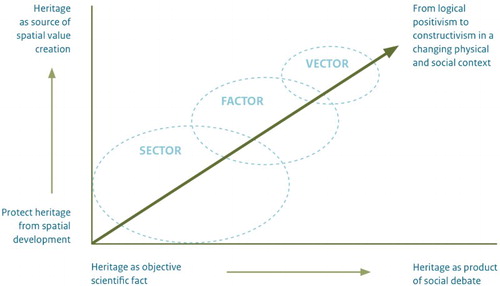

Accordingly, in this article, we use existing literature and examples from Dutch planning practice to construct different approaches through which the various guises of current planning treatment of heritage can be viewed. Relating the above interpretations to the domain of spatial planning and positioning them in time, we frame, somewhat schematically, three successively evolving approaches to heritage conservation in Dutch spatial planning; heritage as sector, as factor and as vector approach, respectively (). In proposing these planning approaches to heritage conservation, our purpose is to explore the flexible interpretations of what constitutes acceptable and desirable conservation practice, as well as the possible articulations between these different interpretations. In the following sections, these approaches are analysed not only as successive stages in the embedding of heritage conservation in the planning system, but also as different modes of dealing with and incorporating heritage in spatial plans and projects. In charting their development, we follow a chronological path, but the layering of the approaches is at least as significant as their historical sequencing.

3. Heritage as a spatial sector: protection and collection

The traditional approach, which we label ‘heritage as sector’, is based on the notion that socio-economic and spatial dynamics pose a constant threat to the cultural heritage. Counteracting forces must be organized to prevent possible loss, to save what is irreplaceable in both cultural and historical terms. The heritage as sector approach developed alongside the post-war expansion of the Dutch welfare state and its ‘regulatory’ planning system. Heritage preservation mainly served as a symbolic backdrop for the modern city and countryside shaped by the accelerating forces of modernization. An inherently modernist discourse got priority, dominated by a preservationist perspective on heritage aimed to save the most valuable relics from the past by classifying it as different from the present. Those scarce historic buildings deemed for preservation should be freed up of neighbouring edifices so that they could stand out in their grandeur. Consequently, the value of the monument did not lie in its performance as an economic or spatial resource, or in its representation of national identity, but in its therapeutic capacity at times of rapid societal change.

The 1961 ‘Monumentenwet’ suited the modernist worldview of saving and reframing the past by means of listing and ‘zoning’. It privileged the architectural merit and historic significance of the physical fabric of the individual monument (cf. Smith, Citation2015). Despite the fact that the ‘Monumentenwet’ introduced a specific instrument for area-based conservation, by means of the protected townscape intended to facilitate spatial dynamics, planners mostly kept to the old focus on monuments and sites and ignored the broader concepts of the urban structure and fabric. Instead, the protected townscape became a widely used instrument in the 1960s and 1970s for the protection of small rural and fortified towns as ‘art-historical monuments’ in their entirety, such as Heusden, Bourtange and Orvelte (Prins, Habets, & Timmer, Citation2014). For these sleepy old towns, historicist reconstruction was seen as a method to attract new economic drivers, particularly tourism. The preservation efforts coincided with demolition, clearance and transformation of what were termed outdated and obsolete inner cities and agricultural landscapes.

The need to include in the recognition of the single historical object the domestic and modest buildings that surround it, did not gain ground in early post-war planning practice. Also internationally, besides some exceptions (e.g. the 1960 Italian Charter of Gubbio, targeting protection and renewal of ancient city centres), the emphasis was on the individual monument, as is evidenced by the creation in 1965 of the International Council on Monuments and Sites that adopted the Charter of Venice as its foundational doctrine. In the first post-war decades, historic buildings were considered ‘irreplaceable’, and heritage was regarded as ‘stock’ that was being threatened, and henceforth, it was first and foremost conceived of in terms of its scarcity. Through a hierarchical, largely government-driven system of policy, legal and financial frameworks, a well-organized profession, trained on the basis of art-historical paradigms, worked to preserve and sustainably manage Dutch heritage resources. The system focused on forming (national) collections of historical objects and landscapes. The focus was on technical and instrumental issues associated with preservation and the material integrity of heritage objects and sites, including the development of methods for assessing the value of cultural heritage objects.

From this early beginning, the heritage as sector approach remained a strong force in Dutch planning practice. Contemporary examples include the comprehensive restoration of the Royal Palace on Dam Square in Amsterdam, the protection of the series of windmills at the World Heritage Site Kinderdijk and the phased renovation of mediaeval St John’s Cathedral in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. In the case of these statutorily listed monuments, the effort of heritage planners is mainly focused on the restoration of the object, urban structure or morphology. In adaptive reuse projects, a split is often made between, on the one hand, the architectural appearance (conservation), and, on the other, the technical development (update) and layout of the building (transformation).

One could argue that the assumptions and ideas underlying the earliest formulations of the heritage concept, as put forward by the 1961 ‘Monumentenwet’, are still in place, albeit in a more flexible guise and in an evolving framework (see below). However, the heritage as sector approach has also been capable of adapting itself to new challenges. In response to critique on favouring elitist and ‘highbrow’ heritage over more mundane heritage objects, more recent elements have been brought within the statutory framework. Subsequently, in the past quarter century, the heritage as sector approach underwent a typological and chronological expansion even to the extent that twentieth-century and vernacular heritage has now made its way into the categories of official listing (cf. Choay, Citation1999). An example is the recent comprehensive cataloguing and assessment of the art, architecture and urban design of the Dutch post-war reconstruction era that is coupled with more development-oriented incentives (Blom, Vermaat, & De Vries, Citation2017).

4. Heritage as a spatial factor: negotiation and revitalization

When it becomes clear and acceptable that not all historical objects can be preserved in good physical condition in the same way, a different approach to the conservation of heritage becomes necessary or desirable. Rigorous protection is then reserved for a selection of the most valued heritage objects. In other cases, a more dynamic and flexible approach gains ground, where heritage is seen as one of many factors that contribute to the quality of a place. The origins of the heritage as factor approach can be traced back to the late 1970s when local policy in Dutch cities established a more systematic and supportive environment for a wider and more dynamic scope of heritage conservation. It was acknowledged that fragments of the past not only retain heritage value but also use value and thus could be assimilated as distinctive elements of a larger contemporary urbanization. This development was fuelled by international ideas on the city’s urban fabric and the possibilities of transformation and urban renewal. The debates of the post-war years and the effects of Modernist transformations of city centres led to a pro-conservation reaction throughout Europe (Veldpaus et al., Citation2013).

Learning from the Malraux experience in France as well as from the Anglo-German and Italian morphological tradition, Dutch architects and planners discovered the city as a morphological and social structure (Crimson, Citation1997). In connection with a widespread strengthening of local voices in planning that opposed the post-war comprehensive redevelopment, the focus of conservation gradually expanded in the 1970s. In addition to the preservation of individual monuments, broader conservation concerns began to feature in local development plans. The Third Memorandum on Spatial Planning (from 1973 onward) made it possible for local governments to combine substantial resources for social housing and urban renewal with heritage conservation. As a result, urban renewal finally got off the ground and the existing city became the focus of municipal planning activities (Prins et al., Citation2014). Maastricht was to become famous for the restoration of the Stokstraat neighbourhood, the first inner city plan whose fundamental principle was respect for the historical structure.

As the renewed appreciation of the historic urban landscape grew, conservation inevitably implied consideration of the functionality of monuments and sites. After the economic crisis of the 1980s, when many industrial areas near the inner cities were abandoned, it soon became clear that simple protection was not enough for these redundant places; they needed to be given a new function. Hence, reuse of old buildings and the intensification of land use through the conversion of heritage sites became central themes (Nijhof, Citation1989). During the 1990s, heritage conservation began to orient itself more explicitly to the (urban) economy, resulting in a ‘partnership’ between (culture-led) regeneration and heritage. Defunct industrial landscapes, such as the Ceramique area in the city of Maastricht and the Kop van Zuid waterfront in Rotterdam, were successfully reworked to give them a new, mixed-use function secondary to their primary significance as heritage ensembles. This kind of strategic reuse of heritage coincided with a shift in spatial planning. Local planning turned towards a development-led and project-based approach (Priemus, Citation2002). In these mostly market-driven developments, the revitalization of heritage became a negotiable factor and heritage was consistently seen as an inherent quality that could be capitalized in order to make the city (and/or region) more attractive (Kloosterman & van der Werf, Citation2009).

The playing field of heritage conservation expanded further as a result of, amongst other things, the decentralization of policy on monuments and historic buildings in the late 1980s and the government’s growing market orientation over the same period, as exemplified by the Fourth Memorandum on Spatial Planning’s focus on public–private partnerships (PPS). Around the turn of the twenty-first century, the so-called Belvedere Memorandum, that established a national incentive programme, gave this trend new direction and focus (Ministerie van OCW, Citation1999). According to Belvedere, only through reuse or transformation, the obvious social and economic potential of heritage could be exploited, thereby underscoring the key role that place identity could play in boosting an area’s economic impact, even beyond attracting tourists. Heritage was placed in the framework of dynamic planning and decision-making processes as part of area developments such as the former industrial area Strijp S in Eindhoven or the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie (New Dutch Waterline), where the adaptive reuse of a great number of monumental buildings and landscape structures was at stake.

Within the newly emerging heritage as factor approach, not only historic but also present-day needs acted as a justification for (the financing of) heritage conservation in the context of area development. Rather than a goal in itself based on intrinsic qualities, conservation became part of large-scale revitalization and regeneration schemes. Whereas valuations in the past were carried out mainly in respect of object, now entire areas had to be described, analysed and valued contextually. Whereas previously agreements could be made about an intervention in a (single) building, now agreements had to be made by entering into public–private partnerships about the development of entire areas and their building stock (Baarveld, Smit, & Hoogerbrugge, Citation2014). Consequently, heritage experts took their place alongside planners, designers, housing associations, property developers and contractors, and provided input for the planning process in the form of arguments for and knowledge of the heritage, not in order to disrupt plans in their initial stages, but to enrich them.

The heritage as factor approach sees heritage as a component of spatial quality embedded in a new plan or regeneration scheme. The plan focuses not so much on the conservation of individual objects, but on the transformation of areas as a whole. The aim is, therefore, not so much on value assessment and rigorous consolidation, but the support of economic value and increase of cultural quality. Attractiveness becomes a more important consideration, in the attempt to create an appealing and interesting living environment, while authenticity becomes less of an argument. Depending on the situation, integrated renovation is just as much an option as is radical alteration or even well-argued demolition. After all, it is not so much the material substance of heritage that is the key, but the contact with the present; the degree to which heritage can be productively linked with present-day claims on territory.

The beginning of the twenty-first century showed a drive towards the codification of the heritage as factor approach in official legislation and policy guidance. Indeed, the 2009 MoMo programme called for a greater awareness for the reuse of heritage buildings and landscapes by means of integrating heritage conservation in mainstream planning policies (Ministerie van OCW, Citation2009). Although it emphasized the importance of cultural arguments in heritage conservation, it complemented these with economic ones. According to MoMo, heritage structures that are only preserved through (state) subsidies would have a precarious future, particularly in the wake of the growing vacancy of historic buildings and sites and the severe economic downturn (Asselbergs, Citation2008). This forced a clear change in the adaptive reuse of heritage properties. The old business model, which drew on public–private investments, no longer functioned and the heritage as factor approach was put to the proof. Currently, a more diverse practice of adaptive reuse is emerging, with new civic initiatives (Gelinck & Strolenberg, Citation2014).

5. Heritage as spatial vector: development and continuity

Spatial developments not only disrupt physical structures, but also tend to root out the stories and meanings associated with buildings and districts. Built and landscape heritage has an essential narrative dimension. Personal memories, genealogical links and scientific reconstructions of historical events impart a narrative structure to the past. Knowledge about what happened in a landscape, district, town, street or building can inspire and guide development to the next stage in both a physical and non-physical dimension. As such, the link between the history of a district or site and contemporary planning is made not (only) through physical structures, but (also) through intangible factors like stories or traditions. This can be useful if few physical traces of the past remain or if the past does not manifest itself in such a way that it immediately conjures up associations (e.g. archaeological relics that are preserved in situ). The heritage as vector approach inspires and guides spatial planning in the broader sense, supplying it with a historical narrative.Footnote1

The cultural shift in understanding heritage this way became apparent at the turn of the twenty-first century with the introduction of the concept of ‘intangible heritage’, bringing stories, traditions and performed culture into the heritage domain (cf. Harrison, Citation2013; Vecco, Citation2010). What used to be called folklore developed into a recognized repertoire of practices and the enactment, transmission and reproduction of these intangible values. The shift entailed a change in focus: from artefacts to people, their memories and genealogy alongside or combined with scientific reconstructions of historical events. These ideas gained momentum with the agenda of public participation put forward by MoMo (Hupperetz, Citation2008). The trend towards growing involvement, leading ultimately to co-creation of heritage values, was now given significantly more weight in planning policy.

Partly as a result of the aforementioned Belvedere programme, several experiments with the combination of immaterial continuity and spatial change were tested in planning practice. An interesting example of such a project is Welcome in My BackYard! (WiMBY!) (Provoost & Vanstiphout, Citation2007). Here, heritage acted as a catalyst for the revaluation and restructuring of the post-war housing district of Hoogvliet near Rotterdam. WiMBY!’s major goal was to break away from the ongoing generic revitalization methods and try to use the specific qualities of the area. The transformation was shaped by the reconceptualization of the ideals underlying the original, modernist design of the district and the social and cultural ties that have grown there over the years: both planned and unplanned, physical and non-physical. Different projects (schools, collective spaces for festive occasions, etc.) were carried out, enriching the renewal process. Continuity of the urban ensemble was achieved not in the preservation of physical structures but in terms of reuse, emotional attachments and (local) stories, thereby using mentality and intangible values as design theme. Concepts underlying or stories attached to buildings and landscape can be captured in a plan or design for renewal, making the more associative meaning of heritage recognizable and perceivable for the inhabitants and visitors. Heritage, in this case, is something that inspires and is fully integrated – in both a material and immaterial sense (Labuhn & Luiten, Citation2014; Meurs, Citation2016).

The concept of ‘biography of landscape’ – an account of the life of a constantly changing cultural landscape put forward by several Dutch academics – helps to capture the complex interplay between material and immaterial values (Bloemers, Kars, van der Valk, & Wijnen, Citation2010; Kolen, Citation2005). A biography is not merely a matter of recording historical data, accounts and events; it also imparts a measure of chronological coherence. It requires trans-disciplinary collaboration between heritage management and related disciplines, and between academic and non-academic sources of knowledge. It can be a useful tool for revealing the layers of history in a landscape in the dynamic context of planning, and of presenting it in an attractive way to designers in the form of atlases. Local citizens can be actively involved in capturing the life history of this landscape. The biography for the Drentsche Aa landscape, for example, acted as a tool for action research and community planning, stimulating a dialogue between residents, designers, nature conservationists and academics (Van der Valk, Citation2014).

Building on these biographical experiments, the heritage as vector approach sets current activities and initiatives in a dynamic spatial and temporal continuum. City and landscape are considered and assessed as a stratified or layered substratum, in which historical qualities are, or can be, present, but where a certain dynamic can also be said to exist. Here, traces of the past are like the illustrations in a book; they help interpret the story, make it accessible, but it makes little sense to isolate and preserve them in time or space (Kolen, Renes, & Hermans, Citation2015). Without the associated narrative, the historical context is soon forgotten and the physical forms and patterns that remain lose their meaning. The heritage as vector approach is therefore less reliant on the government or the private sector. Through an active dialogue with civic stakeholders, it deliberately attempts instead to tie in with broader society, which is where the narrative develops. As a result, the traditional hierarchy of experts and non-experts fades away: plans emerge pre-eminently from the stories and memories (and initiative) of local inhabitants in combination with the knowledge of experts.

The heritage as vector approach is out to achieve more differentiated cultural value creation, encompassing not only the historical or the economic, but also (and above all) the social layering in heritage: the different ways in which different people and groups identify with the heritage and attach value to it. The usage of heritage as a source of inspiration for local and regional development figures prominently in the recent national policy document ‘Character in Focus’ (Ministerie van OCW, Citation2011). This document was a follow-up to the MoMo policy, and can be considered as the next phase in modernizing Dutch heritage management. It rebrands the historic environment as symbiotic to concurrent goals related to spatial challenges in the fields of economics (rural regeneration, population decline), safety (water management) and sustainability (climate change, energy transition). It furthermore makes reference to heritage as a tool to engage communities and foster collaborative planning processes, and it underlines the importance of analysing the life history of the Dutch landscape, making it possible to move from a ‘collection’ of monuments to a multi-layered ‘connection’ of historic sites and landscapes (Ministerie van OCW, Citation2011, p. 6).

6. An expanding repertoire: dealing with multiplicity

The aforementioned historical trajectory has led to various ways of approaching our physical past in a planning context. The advent of each has certainly not precipitated any radical shifts between coordination mechanisms. Instead, they brought about an expansion of the repertoire of dealing with heritage in the context of spatial planning: from the sectorial preservation and protection of objects only, to the spatial development of larger heritage landscapes, to providing meaning in all kinds of social, economic as well as spatial processes. In parallel, the fixed, intrinsic and rather static vision of heritage conservation was challenged and more dynamic concepts emerged in response to new challenges, such as the transformation of defunct industrial sites and landscapes in the late 1980s or the relinquishing of planning controls and a growing class of bottom-up, grassroots initiatives in the post-crisis period.

Indeed, besides responding to the physical expressions of economic restructuring of the time, the various approaches reflect the structural transformations of the Dutch welfare state regime: from a strong emphasis on the public sector to a public/private mix and, currently, a ‘participation society’ which relies on civic sector initiatives. Consequently, the Dutch government has taken steps to introduce market-based and civic-based values into its ‘regulatory’ spatial planning system (Van der Cammen & De Klerk, Citation2012). Where the heritage as sector approach is part and parcel of the comprehensive planning effort of the welfare state, the heritage as factor approach coincides with the liberalization and privatization tendencies, relying much more on the market, as reflected by PPS (re)development projects since the 1980s. The heritage as vector approach both suits and fuels the current emphasis on co-creation and the do-it-yourself mentality promoted by retreating governments ().

Figure 2. Welfare state reform and heritage management: from institutionalization and marketization to socialization.

What connects the different approaches is their emphasis on a careful interpretation of history. The main difference lies in how they frame heritage issues and, subsequently, interpret the relationship between heritage and development. Whereas the heritage as sector approach tries to protect heritage from spatial development, the heritage as vector approach, on the other hand, sees heritage as product of a social process and uses it as a place-making tool. Dealing with heritage has broadened from an inward-looking, technical and instrumental perspective focused on the ‘intrinsic’ value and materiality of heritage towards a more open, strategic and political perspective, in which it is understood as the product of a broader social context, and in which immaterial dimensions also play a role (). This entailed a shift from logical positivism based on empirically observable and verifiable historical data to social constructivism, which allows scope for emotion and engagement, different cultural perspectives and various forms of appropriation (cf. Harrison, Citation2013).

As a result of the partial superimposition of new perspectives over previous approaches, heritage conservation now has at its disposal a number of mechanisms and logical frameworks for dealing with the past, which in contemporary planning practice exist in parallel and in combination, and are often mutually dependent on each other. The heritage as sector approach, which focuses on the formation of a national collection, is the oldest form of conservation practice, strongly rooted in a range of formal and informal institutions, with strong advocates and a large body of knowledge. Thus, it is still the most dominant approach in contemporary Dutch (as well as international) planning. The heritage as factor approach, which focuses on revitalization and negotiation, is only recently becoming a respected and much applied approach. Some of the ideas behind this approach have now filtered into official guidance. Finally, the heritage as vector approach, which focuses on development and continuity, is scarcely institutionalized, given its short history. The underlying shifts in ideas on heritage and a number of non-statutory government publications, like the aforementioned ‘Character in Focus’, have not yet been reflected as strongly in planning practice. The approach is still in the experimental stage, although locally support is growing.

Besides their different institutional embedding, the heritage as sector, factor and vector approaches each have their own ‘raison d’être’ in current planning practice. They frame heritage issues in their own way, resulting in different ways of formulating solutions to tackle current spatial challenges and, as a consequence, different types of planning and management strategies. The consequence of understanding the institutionalization of heritage in planning as a process of ‘layering’ is that it results in an increasingly mixed perspective, in which various approaches with their own principles and standards not only function alongside one another in contemporary planning developments, but also coexist in various combinations and differ in the significance of their overlap depending on the specific circumstances. This, of course, can lead to tension and conflict at the local level, as the interests and perspectives on the values of heritage and how to deal with it accordingly greatly diverge. Indeed, as Ashworth (Citation2011) emphasizes, conflicts over the usage of heritage in planning practice are often based on substantial differences in values. However, current ‘post-crisis’ planning practice with its limited resources, spatial differences and high pressures on land resources does not call for a new, uniform approach that can be applied as a standard, but rather for a mixed-mode model that is capable of handling a variety of diverse approaches simultaneously.

What is important and integral to current conservation efforts is the ability to assess different heritage resources in their context (location, spatial and policy issues, playing field), and apply the most suitable approach accordingly. How (the combination of) each approach is operationalized is context- and site-specific. Within the current ‘Character in Focus’ programme, a growing number of instruments have been developed that enrich the ‘toolkit’ of the heritage professional. Sector-type instruments such as restoration plans, cultural–historical analyses and valuation methods are now accompanied by factor approach frameworks, mapping area-based development processes, and explicating when and how can heritage professionals can add to these projects. Furthermore, biographies and visual accounts on the grand challenges such as water safety and energy transition place current efforts in a broader perspective and provide design principles just as well as historic solutions (RCE, Citation2016).

In this style of governance, success does not so much require a focus on the newest approach, but instead on the heritage professional’s ability to deal with multiplicity. Dealing with multiplicity involves making choices. The need to be more selective, and identify which approach is needed for a particular situation, is fuelled by the 2008 global economic downturn and subsequent ‘roll-out’ of austerity measures and changes in ‘regulatory’ spatial planning. National government is backing off to a further extent, as illustrated by the announcement of the Housing Minister to sell 34 state-owned listed buildings and monuments (Blok, Citation2013). The tasks and responsibilities of public, private and civil society partners are currently being revised, alongside modification of planning regulations and incentives. In particular, the ability of the local government and the private sector to perform and support heritage management is fading away as budget cuts, privatization and deregulation take hold in different degrees (Gelinck & Strolenberg, Citation2014).

These changes present new challenges for the different heritage approaches. Of course, the heritage as vector approach provides new opportunities at a time when Dutch spatial planning is abandoning large-scale, planned developments for more organic, bottom-up development strategies (Buitelaar & Bregman, Citation2016). The social orientation of the heritage as vector approach creates space for (dispersed) initiative, grassroots support and citizen engagement in the heritage management process. It is in keeping with the agenda of deregulation and a more focused government, as well as with the agenda of participation and co-creation, both sharpened by neoliberal political ideology and financial imperatives. However, in the new planning context, the heritage as sector approach continues to be relevant, albeit in an altered context and form, while the heritage as factor approach keeps its relevance for younger, large-scale heritage buildings and landscapes.

7. Conclusion

Based on our experiences in the Netherlands, we presented a classification of the planning treatment of heritage in three categories, which we labelled the sector, factor and vector approach, respectively. These three developed one after the other. This succession, however, did not indicate a full-fledged (and paradigmatic) transition in which the use of heritage in spatial plans and developments is completely reversed and displaced by new ways of working. Instead, all three approaches are still relevant and they complement each other in the present, enriched repertoire. Analysing the integration of heritage in mainstream planning as an evolutionary process of institutional layering which proceeded in small steps not only means that there is a continuous sedimentation in ideas on heritage, linking the issue of conservation to that of spatial development, but also of continuity of policy and practice.

Although there have been several formal reforms of the Dutch planning system over the last half century, these largely built on prior systems, and can therefore best be typified as incremental revisions. The process of incremental change is strengthened by the fact that policy changes in the field of heritage have not been enforced through replacement of legal systems but largely through legal ‘stretching’ (for instance, requiring local governments to take cultural–historical ‘values’ into account, not just listed buildings) and the adoption of non-statutory (supra)national policy documents and visions such as the Belvedere Memorandum and ‘Character in Focus’. It therefore has been a process of compliance through inspiration instead of legal enforcement (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). This explains, in part, why Dutch planning practice overall remains more wedded to the more clear-cut core statutory tasks of preservation as embodied by the heritage as sector approach rather than the wider scope and more dynamic usage of heritage as factor and vector approach, respectively.

As the process of integrating heritage conservation in spatial planning has been a layered one, it has resulted in an increasingly mixed perspective, in which various approaches have come to stand alongside one another. While some scholars regard the latest, more inclusive and development-oriented heritage as vector approach as the new orthodoxy that should guide planning practice (cf. Smith, Citation2015), we call for a rethinking of the casting aside of existing approaches. Rather, realigning traditional heritage practices and emerging approaches to society’s advantage is to be considered. The balance this requires is more in the vein of synchronization than it is transformation or displacement; the issue is not one of adopting a new paradigm, but instead about the art of selection from a repertoire, identifying which approach is best suited for a given situation. We therefore see no reason to highlight one approach over the other.

Successful contemporary heritage practices can no longer be characterized solely as public, private or civic; they are plural, often containing a mix of several approaches. Both the global protection of the outstanding universal values of UNESCO World Heritage sites and the protection of a characteristic yet mundane church in a small village that is given a new purpose in its community are part of this enriched, more plural heritage planning. The intrinsic historical significance that plays such a key role in the heritage as sector approach, with its associated protection mechanisms, remains relevant, but in a system where there is now also room for economic significance as featured in the heritage as factor approach, and the intangible values that feature in the heritage as vector approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments and suggestions that contributed to improving the article, as well as Prof. Dr. Jos Bazelmans (Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands) for his invaluable support, time and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The notion of heritage as a ‘vector’ for sustainable development has been discussed at the workshop Partnership for World Heritage Cities – ‘Culture as a Vector for Sustainable Development’, organized by the World Heritage Centre and local authorities in Urbino (Italy) in November 2002. Participants drew attention to the social and cultural riches of heritage (Bandarin & van Oers, Citation2012, p. 106).

References

- Ashworth, G. (2011). Preservation, conservation and heritage: Approaches to the past in the present through the built environment. Asian Anthropology, 10(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1080/1683478X.2011.10552601

- Ashworth, G., & Howard, P. (1999). European heritage planning and management. Exeter: Intellect Books.

- Asselbergs, F. (2008). De oude kaart van Nederland. Leegstand en herbestemming. Den Haag: College voor Rijksadviseurs.

- Baarveld, M., Smit, M., & Hoogerbrugge, M. (2014). Bouwen aan herbestemming van Cultureel Erfgoed. Den Haag: Platform31.

- Bandarin, F., & van Oers, R. (2012). The historic urban landscape. Managing heritage in an urban century. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell.

- Bloemers, T., Kars, H., van der Valk, A., & Wijnen, M. (2010). The cultural landscape & heritage paradox; protection and development of the Dutch archaeological–historical landscape and its European dimension. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Blok, S. (2013). Brief van de Minister voor Wonen en Rijksdienst; Beleidskader voor de Monumenten met Erfgoedfunctie van de Rijksgebouwendienst. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer.

- Blom, A., Vermaat, S., & De Vries, B. (2017). Post-War Reconstruction in the Netherlands 1945–1965. The Future of a Bright and Brutal Heritage. Rotterdam: NAi010 Publishers.

- Bosma, K. (2010). Heritage policy in spatial planning. In J. H. F. Bloemers, H. Kars, A. van der Valk, & M. Wijnen (Eds.), The cultural landscape & heritage paradox: Protection and development of the Dutch archaeological–historical landscape and its European dimension (pp. 641–652). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University press.

- Buitelaar, E., & Bregman, A. (2016). Dutch land development institutions in the face of crisis: Trembling pillars in the planners’ paradise. European Planning Studies, 24(7), 1281–1294. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1168785

- Choay, F. (1999). The invention of the historic monument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Corten, J. P., Geurts, E., Meurs, P., & Vermeulen, R. (2014). Heritage as an asset for inner-city development. Rotterdam: NAi010.

- Crimson. (1997). Re-urb. Nieuwe plannen voor oude steden. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010.

- Denhez, M. C. (1997). The heritage strategy planning handbook. Oxford: Dundrum Press.

- Fairclough, G. (2008). New heritage, an introductory essay – people, landscape and change. In G. Fairclough, R. Harrison, J. Shofield, & J. H. Jameson (Eds.), The heritage reader (pp. 297–312). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fairclough, G., & Rippon, S. (2002). Europe’s landscape: Archeologists and the management of change (EAC, Occasional Paper 2). Brussels: EAC.

- Gelinck, S., & Strolenberg, F. (2014). Rekenen op herbestemming. Idee, aanpak en cijfers van 25 + 1 gerealiseerde projecten. Rotterdam: NAi010.

- Glendenning, M. (2013). The conservation movement. A history of architectural preservation. London: Routledge.

- Grijzenhout, F. (2007). Erfgoed: de geschiedenis van een begrip. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Harrison, R. (2013). Heritage, critical approaches. London: Routledge.

- Hupperetz, W. (2008). Monumenten stemmen. Visies op de modernisering van de monumentenzorg. Amsterdam: Erfgoed Nederland.

- Janssen, J., Luiten, E., Renes, H. & Rouwendal, J. (2014). Heritage planning and spatial development in the Netherlands: changing policies and perspectives. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 20(1), 1–21. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2012.710852

- Kalman, H. (2014). Heritage planning: Principles and process. London: Routledge.

- Kloosterman, R. C., & van der Werf, M. (2009). Culture: A local anchor in a world of flows? Spatial planning and the role of cultural spatial planning in the Netherlands. In P. Benneworth & G. J. Hospers (Eds.), The role of culture in the economic development of old industrial regions (pp. 45–66). Wien: LIT.

- Kolen, J. (2005). De biografie van het landschap. Drie essays over landschap: Geschiedenis en erfgoed. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

- Kolen, J. (2007). Het historisch weefsel. Over de transformatie van de regio en de omgang met het verleden in de 21ste eeuw. In J. Rodermond (Eds.), Perspectief. Maakbare geschiedenis (pp. 46–77). Rotterdam: Stimuleringsfonds voor Architectuur.

- Kolen, J., Renes, J., & Hermans, R. (2015). Biographies of landscape: Geographical, historical and archaeological perspectives on the production and transmission of landscapes. Amsterdam: AUP (Landscape & Heritage Series).

- Kuipers, M. (2012). Culturele grondslagen van de Monumentenwet. KNOB Bulletin, 1, 10–25.

- Labadi, S., & Logan, W. (2016). Approaches to urban heritage, development and sustainability. In S. Labadi & W. Logan (Eds.), Urban heritage, development and sustainability (pp. 1–20). London: Routledge.

- Labuhn, B., & Luiten, E. (2014). Ontwerpen met erfgoed. Leren van de Belvedere-ervaring. Blauwdruk Publishers, Wageningen – Delft University of Technology (internal publication).

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2010). Explaining institutional change. Ambiguity, agency and power. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- March, J. C., & Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions: The organizational basis of politics. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Meurs, P. (2016). Heritage-based design. Delft: TU Delft.

- Ministerie van OCW. (1999). Belvedere. Beleidsnota over de relatie tussen cultuurhistorie en ruimtelijke inrichting. Den Haag: Author.

- Ministerie van OCW. (2009). Beleidsbrief Modernisering Monumentenzorg. Den Haag: Author.

- Ministerie van OCW. (2011). Kiezen voor Karakter. Visie erfgoed en ruimte. Den Haag: Author.

- Nijhof, P. (1989). Het industrieel erfgoed en de kunst van het vernietigen. Zeist: Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg.

- Pendlebury, J. (2009). Conservation in the age of consensus. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pickard, R. (2002a). European cultural heritage. Vol. 2, a review of policies and practice. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Pickard, R. (2002b). Area-based protection mechanisms for heritage conservation: A European comparison. Journal of Architectural Conservation, 8(2), 69–88. doi:10.1080/13556207.2002.10785320

- Priemus, H. (2002). Public-private partnerships for spatio-economic investments: A changing spatial planning approach in the Netherlands. Planning Practice and Research, 17(2), 197–203. doi: 10.1080/02697450220145940

- Prins, L., Habets, A. C., & Timmer, P. J. (2014). Bekende gezichten, gemengde gevoelens. Beschermde stads- en dorpsgezichten in historisch perspectief. Amersfoort: Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed.

- Provoost, M., & Vanstiphout, W. (2007). WIMBY! Hoogvliet. Toekomst, verleden en heden van een new town! Rotterdam: NAi.

- Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed. (2016). Handreiking Energie, erfgoed en ruimte. Amersfoort: Author.

- Smith, J. (2015). Applying a cultural landscape approach to the urban context. In K. Taylor, A. St. Clair, & N. Mitchell (Eds.), Conservering cultural landscapes. Challenges and new directions (pp. 182–197). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sorensen, A. (2015). Taking path dependence seriously: A historical institutionalist research agenda in planning history. Planning Perspectives, 30(1), 17–38. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2013.874299

- Taylor, Z. (2013). Rethinking planning culture: A new institutionalist approach. Town Planning Review, 84(6), 683–702. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2013.36

- Thompson, S. (2012). Introduction. In S. Thomposon & P. Maginn (Eds.), Planning Australia. An overview of urban and regional planning (pp. 1–14). Sydney: Cambridge University Press.

- Van der Cammen, H., & De Klerk, L. (2012). The selfmade land: Culture and evolution of urban and regional planning in the Netherlands. Houten: Spectrum.

- Van der Steen, M., Scherpenisse, J., & van Twist, M. (2015). Sedimentatie in sturing. Systeem brengen in netwerkend werken door meervoudig organiseren. Den Haag: NSOB.

- Van der Valk, A. (2014). Preservation and development: The cultural landscape and heritage paradox in the Netherlands. Landscape Research, 39(2), 158–173. doi:10.1080/01426397.2012.761680

- Vecco, M. (2010). A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11(3), 321–324. doi: 10.1016/j.culher.2010.01.006

- Veldpaus, L., Pereira Roders, A. R., & Colenbrander, B. (2013). Urban heritage: Putting the past into the future. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 4(1), 3–18. doi:10.1179/1756750513Z.00000000022