?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

A substantial area of permanently habitable land in Austria is already sealed to be used for residential, commercial, and infrastructural purposes. Although the annual land consumption used for these purposes has slightly decreased over the last 20 years, it is still at an alarmingly high rate. In 1996, the daily land consumption corresponded to over 30 hectares, while it dropped to about 10 hectares in 2016. In this paper the determinants of land consumption were confirmed within the econometric framework of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC). In the EKC it is assumed that there is an inverted-U shaped connection between the GDP and land consumption. In this conceptual framework, the effectiveness of spatial planning frameworks, such as the Austrian Spatial Development Concept (ÖREK), was tested. The results show that, in Austria, there is a general trend towards a decrease in land consumption. The effectiveness of spatial planning frameworks is, however, not discernible from the general influence of an increase in the GDP. Both the increasing scarcity of land (reflected in the increasing land prices) and the increased efficiency of the use of land (as a result of population density and urbanization), contribute to the reduction of land consumption. This indicates that additional and more effective policy instruments, such as brownfield and inward development, land mobilization strategies, higher land taxes and urban contractual agreements are all urgently needed to reduce land consumption to much lower sustainable levels.

1. Introduction and background

In 2016, of the total area of Austrian land, 6.7% was consumed to create residential and commercial areas, as well as to develop infrastructures. Over the past 20 years, the total extent of built-up land areas increased by 52%. In 1996, only 4.4% of the total Austrian land was consumed. However, while the extent of land that was consumed does not seem, in relation to the total land area of Austria, to be of major economic or ecological concern, one has to bear in mind that forests cover about 50% of the land in Austria and, in addition, the high Alpine mountain areas cover 20% of the land. Therefore, the proportion of land that is consumed is, in relation to that which is totally habitable land, much higher and currently amounts to 17% (STAT, Citation2017). Compared with the European average, Austria's land consumption is significantly greater than in the rest of the European Union (EU). On average, an EU citizen made use of 389 m2 of (sealed) land in 2006. In Austria, built-up areas amounted to 595 m2 (2006). In addition, in Austria, the increase in built-up areas was much faster (+32.2% from 1996 to 2006) than that in the EU (+8.8% from 1990 to 2006) (the figures for the EU are taken from Prokop, Jobstmann, & Schönbauer, Citation2011; those for Austria are the authors’ calculations based on UBA, Citation2017; and STAT, Citation2017).

In most cases, the surface of the ground on which an area is built up for residential, commercial or infrastructure purposes has to be covered, i.e. sealed, with impermeable material (such as concrete, asphalt, paving stones, and suchlike). However, this diminishes a wide range of ecosystem services of the soil. The major problems that arise when the ground is sealed off are not only that rainwater cannot be absorbed to supply the soil below with the moisture necessary for vegetation to grow. There is also no supply to maintain a certain level of groundwater (especially in highly productive agricultural land), and flooding has to be expected when there is heavy rainfall, especially over prolonged periods. Furthermore, there is the reduced mitigation of (urban) heat islands by impaired capacities of the environment to influence the local micro-climate. ‘Sealed soils can be defined as the destruction or covering of soils by buildings, constructions and layers of completely or partly impermeable artificial material […]. It is the most intense form of land take and is essentially an irreversible process’ (Jones et al., Citation2010). The subsequent loss of the benefits that the soil ecosystem provides has been widely documented (e.g. Lauf, Haase, & Kleinschmit, Citation2014; Smiraglia, Ceccarelli, Bajocco, Salvati, & Perini, Citation2016; Turner et al., Citation2016).

Of course, there are different factors that determine total land use and land consumption. On the one hand, the development of the economy, in regard to the use of resources for production and consumption, as well as the extension of infrastructures (e.g. highways, power plants, local utilities) determine how land is to be used (Colsaet, Laurans, & Levrel, Citation2018). Furthermore, demographic and social developments influence preferences, behaviour and demand, as well as people’s perceptions of land use in general. Such developments include, for instance, social change owing to the aging of society, smaller families, or a higher number of singles in households (Haase, Seppelt, & Haase, Citation2008; Salvati, Zambon, Chelli, & Serra, Citation2018). On the other hand, public authorities as the main decision makers in spatial planning, on several levels of government, facilitate, influence and manage land consumption. Many diverse spatial planning instruments are used, such as zoning plans, building codes, as well as regional and infrastructure development plans (Prokop et al., Citation2011).

In regard to (technical) infrastructure, Austria is a highly developed industrialized country regularly praised for its high quality road and energy networks, and municipal and regional utilities (e.g. water provision and waste management). Economic theory and many empirical studies infer that infrastructure development is crucial to economic and social development. Getzner (Citation2012) held a discussion on the determinants of the infrastructure investments for Austria and found some indication of a recently reversed causation. Owing to economic growth, policy makers and planners have the economic resources at hand to increase infrastructure investments. Thus, one of the main causes of land consumption owing to the extension of infrastructure networks is economic growth – instead of economic growth depending on infrastructure investments. This is in some contradiction to theories on regional development, in which it is argued that infrastructure investments cause or facilitate economic growth (for a recent meta-analysis of the economic effects of public works programmes, see Gehrke & Hartwig, Citation2018).

As a conceptual model, the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) is used and tested in this paper (see Sections 3 and 4.2 for more details). This model confirms that the explanatory power of economic growth (GDP, gross domestic product) is a determining factor in regard to the use of resources and land consumption, as well as the subsequent environmental effects of economic growth (e.g. pollution; see Dinda (Citation2004) and Stern (Citation2004), for reviews of this concept). In the EKC it is assumed that resource consumption increases when GDP also increases up to a certain turning point, after which economic growth can be further achieved while, at the same time, the use of resources is reduced (cf. Xepapadeas, Citation2005). In other words, environmental degradation, resource use and land consumption, are thought to grow at low levels of the GDP, and then to reach a peak (turning point). After this point, the use of resources declines while the GDP continues to increase. Such developments have been labelled as the decoupling of the GDP and resource use after the turning point of the EKC (e.g. Krausmann et al., Citation2009). The inverted-U functional form of the connection between the GDP growth and resource use can be explained in the following way: National economics in their early stage of development manage to grow by using more resources, e.g. for industrial production including heavy industries and mining. At higher levels of the GDP, environmental resource exploitation and pollution increase as well. Higher levels of the GDP also lead to an increased demand for environmental goods and services (e.g. recreation in unpolluted natural environments, biodiversity conservation). Consequently, citizens vote for stricter environmental regulation. In combination with the structural change of the economy with a higher share of the service sector that uses less resources, overall pollution is less when GDP levels are higher (a recent critical reflection of the EKC concept in regard to CO2 emissions can be found in Mardani, Streimikiene, Cavallaro, Loganathan, & Khoshnoudi, Citation2019). For Austria, Friedl and Getzner (Citation2003) tested this notion in regard to the CO2 emissions and found that the EKC hypothesis does not hold, at least, for the observation period. Getzner (Citation2009) tested the EKC hypothesis in regard to Austrian domestic material consumption (DMC) and also found no absolute decoupling between the GDP and material inputs to the Austrian economy. However, the per-unit use of a resource decreases owing to the higher efficiency of production, while the total use of resources still increases. One of many recent international studies on the connection between the increase in GDP and use of resources also does not find an EKC-type correlation (cf. Steinberger, Krausmann, Getzner, Schandl, & West, Citation2013; see Ekins, Citation1997, for a review of earlier evidence).

By now, there are hardly any papers available on the determinants of land consumption in the framework of the Environmental Kuznets Curve, although land consumption represents a key dimension of environmental degradation and the use of resources (Jones et al., Citation2010). One of the few empirical applications of the EKC concept put forward by Bimonte and Stabile (Citation2017a) was to test the EKC hypothesis concerning building permits in Italy. The authors found per-capita permits to be reduced when GDP levels are higher. However, in regard to the supply of new housing, Bimonte and Stabile (Citation2017b) found an N-shaped curve of the correlation between the supply of housing and the GDP. After an initial decrease in building activity following a higher GDP, it increased again.

Caldera and Johansson (Citation2013) found a direct connection between disposable household income and housing demand. Their paper is an international analysis of a wide range of OECD countries, and shows that a higher disposable income of households relates to increasing prices (on account of the scarcity of land) and housing demand. This positive correlation suggests that income growth is one of the major driving forces behind the increases in land consumption. As household incomes and as a result, living standards increase, the living space per capita diminishes and so, as a consequence, land consumption increases. Thus an increase in incomes not only has an effect on the demand for housing, but it is also an incentive to increase the housing supply. Green, Malpezzi, and Mayo (Citation2006) empirically confirm the level of income as an important determinant in regard to housing supply, together with other factors (e.g. prices) and – to a certain extent – land use regulations. Higher incomes may also lead to a further increase in land consumption (as built-up areas), if there is a greater demand for an additional residence, as well as for more extensive mobility – and, as a consequence, to further land sealing, not only for the construction of buildings, but also for the infrastructure.

Gennaio, Hersperger, and Bürgi (Citation2009) examined more closely the effects of land-use regulations on land consumption. They came to the conclusion that urban growth boundaries and green belts slow down the expansion of built-up areas in designated non-building zones, however, without completely stopping it (see also Bengston & Youn, Citation2006; Siedentop, Fina, & Krehl, Citation2016; Weitz & Moore, Citation1998). Anthony (Citation2004) provides quantitative, although not statistically significant, evidence for the effects of anti-sprawl policies on land consumption by examining growth management policies across 49 US States over a 15-year period. In the same vein, during a period of over 30 years, an ex-post evaluation of compact urban development in the Netherlands led to the conclusion that without such policies, the urban sprawl would probably have been much higher, however, without quantifying precise effects (Geurs & van Wee, Citation2006). Halleux, Marcinczak, and van der Krabben (Citation2012) stress the importance of regulation and land-use planning. The authors find that planning instruments do exert regulatory power to avoid urban sprawl, however, only in institutional and societal contexts that render land-use instruments effectively in a governance system that is functioning very well. Similarly, Gallardo and Martínez-Vega (Citation2016) stress the importance of effective policy implementation to reduce urban sprawl. Thus, despite the fact that there are land-use regulations, they may remain ineffective owing to the failure to implement them, as well as weak governance (Gallardo & Martínez-Vega, Citation2016); a lack of vertical and horizontal coordination between relevant actors (Faludi, Citation2000) or between planning goals and agendas (Stead & Meijers, Citation2009).

In order to empirically test the influence of GDP, whenever it increases, on land use, this study deals with the statistical analysis of the GDP land-use nexus by accounting for the federal structure of Austria (each of the nine Federal Provinces has its own land-use and building laws). The period from 1994 to 2016 is taken into consideration in order to show the potential influence of regulations, strategies and land-use concepts. The empirical estimations also include several variables denoting the occurrence of these regulations and concepts. As will be shown, an increase in the efficiency of land use can be observed over the period of analysis (i.e. a decrease of marginal land consumption per capita or the GDP unit within a given period of time). However, in the case in this study, spatial planning regulations, strategies and concepts do not seem to directly influence land consumption, and do not exert a discernible effect on reducing land loss.

The structure of the paper is as follows: The spatial planning frameworks of Austria, and the changes therein over the past 20 years are presented in Section 2. The conceptual model, methods and data are discussed in Section 3. The descriptive and econometric empirical results, as shown in Section 4.1 and 4.2, respectively. Finally, the results are summarized and discussed in Section 5 and the policy conclusions are drawn.

2. Overview of the development of spatial planning frameworks in Austria over the last twenty years

In Austria, the structure of planning regulation strongly reflects the federal layout of the broader regulatory system. Newman and Thornley (Citation1996, p. 34) classified Austria as a Germanic planning system featuring the high importance of the written constitution (basic laws) and a fragmented, federalized decision-making system. At the national level, spatial development concepts (Österreichisches Raumentwicklungskonzept, ÖREK) are published on a regular, (usually) 10-year basis (Humer, Citation2017). They are not legally binding, but guide policies at lower levels. The planning of laws fall under the jurisdiction of the nine Federal Provinces. The laws are adapted on a more or less regular basis, reflecting relevant developments and federal guidelines. Each Federal Province (Bundesland) also prepares legally non-binding development concepts. The 2100 municipalities and their city councils are responsible for local planning and land-use decisions. These draw on strategic, legally non-binding development concepts, legally binding zoning plans to classify plots based on their designated use, as well as more specific site plans for single plots. The Provincial Governments supervise local planning decisions and thus ensure that the municipalities conform to provincial planning concepts and laws, and are financially sound. The fragmented system and the spread of legal competences between the provincial and municipal levels leave room for ineffective policy implementation and enforcement. Although provincial governments have a supervising role in municipal planning decisions, the municipalities have a certain degree of autonomy in enforcing the provincial legal frameworks. For several years, the municipalities have made use of this autonomy and designated much more land for construction than actually needed. To some degree, the municipalities are given incentives to do so through the design of the tax system. As local taxes are calculated based on the economic output of companies, local governments compete in their attempt to attract companies. They, inter alia, use land for building purposes as a location factor to attract new businesses (UBA, Citation2016, p. 142). Moreover, as the rules for strategic environmental assessments (SEA) exist in Austria, that may provide a barrier to extensive land consumption and other environmental damage. Stoeglehner (Citation2010, p. 229) reports that only some 10% of the municipal spatial planning processes undergo a full SEA, which undermines the relevance of this instrument. Another major reason for policy failures to curb land consumption at the municipal level is the (local) political economy of land-use decision-making (Calabrese, Epple, & Romano, Citation2007; Hilber & Robert-Nicoud, Citation2013).

In recent years, measures to curb land consumption and land sealing have been intensified and spatial planning frameworks have been adapted at different government levels. In 2002, the Central Government published the ‘Austrian Strategy for Sustainable Development’ (STRAT). It set the target to reduce the annual increase in permanently sealed soil to only 10% of what it was in 2002 which should be achieved not later than the year 2010. In other words, the strategy aimed at reducing marginal land consumption from about 21 hectares (2002) to 2 hectares per day. In addition, limiting the increasing fragmentation of landscapes and the conservation of soil functions should be given priority (Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft [BMLFUW], Citation2011). In 2009, to increase the effectiveness of the sustainability strategy, the Central Government decided that a steady monitoring system of land consumption, based on a standardized methodology, should be implemented in all of the nine Federal Provinces.

Since then, all of the nine Federal Provinces have adapted their legal frameworks. In general, these changes fall into three categories: (1) The lawmakers introduced time-limited building permits. Many owners have plots of land that they do not intend, for different reasons, to develop at any time in the near future. Constantly issuing new zoning plans and building permits, however, leads to urban sprawl and inefficient land use. Time-limited building permits enable the municipalities to withdraw the right to build, or to re-zone building land to green land after a certain period. The specific rules, as well as the relevant periods, are not the same in the nine Federal Provinces. In Styria, for example, time-limited permits are not just an option, but mandatory for plots larger than 3000 m2. While this policy may contribute to more efficient zoning decisions, it can be applied only to newly-issued building permits, while those plots for which decisions were rendered in the past are exempted.

(2) Most of the Federal Provinces have introduced the possibility for municipalities to draw up their own development contracts with landowners. If a municipality sells land to a private owner, a contract may specify the option for future use, and the time frames for the completion of building projects. The contract may also oblige owners to contribute to the financing of infrastructure costs (e.g. water supply or waste-water management) for the plot (European Communities, Citation2011; on the potential pitfalls of contractual agreements from an economic perspective, cf., Getzner, Citation2017). Again, the specifics of the Federal Provinces are not all the same.

(3) Some of the Federal Provinces have implemented policies to mobilize existing land for building purposes that are currently unused (vacant land). In Lower Austria, for example, the municipalities can re-arrange plot boundaries in order to make plots more suitable for development, if the majority of the owners agree. Tyrol has implemented similar policies. In addition to these legal changes made by these Federal Provinces, a number of strategies and guidelines have been prepared. Noteworthy are, for example, the national guidelines in regard to brownfield mobilization, which was published in 2008. Furthermore, some of the Federal Provinces have adapted their development plans to protect green space more effectively, and to curb the fragmentation of landscapes and ecosystems. Despite these measures, land mobilization remains a serious challenge. In 2011, 26% of the land designated for residential construction was undeveloped (BMLFUW Citation2011, 13).

In comparison to the other EU countries, policies ‘on paper’ against further land consumption are rather strict in Austria. A report (European Communities, Citation2011, p. 17 ff.) found Austria to be one of eleven EU 28 countries that had implemented ‘specific measures to reduce soil sealing and sprawl’. Also, it was one of six countries that had specific policy targets in force, including a quantitative limit for annual land loss.

3. Conceptual model, data and methods

Following the discussion on the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) above, an analysis was made to test the influence an increase in the GDP would have on land consumption, as well as on the potential influence of land use regulations, strategies and land use concepts. In Section 4.2, the empirics of the conceptual EKC model is outlined in more detail. In this empirical model, the change in land consumption depends on the GDP per capita in an econometric panel setting. Furthermore, explanatory variables also include data on land use policies. The EKC concept is therefore a macro concept linking economic development and growth to environmental effects. There are, of course, many different empirical models, which explain and predict land consumption and land use (e.g. Chakir & De Gallo, Citation2013). For the purpose of this study, and given the available data, the empirical EKC approach of Bimonte and Stabile (Citation2017a) was adapted to the Austrian context as their paper is one of the first applying the EKC concept in the context of planning, construction, and land consumption.

For the data used, a clarification is necessary in regard to the sources of these data and the operationalization of land consumption, as well as changes when planning frameworks. For land consumption, this paper draws on data from ‘Statistics Austria’ (STAT, Citation2017) and the ‘Austrian Federal Environmental Agency’ (UBA, Citation2017). The statistical category of land consumption does not apply to the total territory of land use (including agricultural land), but accounts specifically for land in which the ground is permanently sealed for transportation, residential or commercial purposes. In addition, infrastructures, such as the facilities for the production of energy, are included. In , Section 4, a range of indicators on land consumption in this paper are presented.

Table 1. Land use: built-up areas in Austria: descriptive overview.

For changes in planning frameworks, systematically analysed spatial planning reports were made (BMLFUW, Citation2011; Lanegger & Froehlich, Citation2014; ÖROK, Citation2017; SIR, Citation2016) to identify, since 1995, the regulatory changes to curb land use. A distinction is also made between legally non-binding concepts and strategies (CS), as well as legally binding law changes (L). Furthermore, this paper differentiates between the Central Government level and the Federal Province level. The results conform to the timeline of the spatial planning laws of the ‘Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning’ (ÖROK, Citation2018). Regulatory frameworks that influence land use, but are not directly part of spatial planning regulation, were excluded (e.g. housing subsidies, fiscal constitution, infrastructure financing). An important point is that the data that is available for this paper includes only the changes in the legal frameworks at Central Government and Federal Provincial levels, but not for actual decision-making at the municipal level. As mentioned above, the analysed laws and the changes therein provide the regulatory context for municipalities with regard to the enforcement of spatial planning policies, although municipalities operate with a certain degree of autonomy. Thus, Central Government and Federal Province frameworks offer key insights into the development of land-use regulations. The analysed changes were discussed in the last chapter and are summarized in .

Table 2. Changes in existing frameworks targeting built-up areas.

In the first step, a descriptive analysis was carried out. The total and marginal (annual) change in land use and the GDP in Austria were mapped. In order to ascertain relevant changes, the changes of per-capita land use and the regional per-capita GDP for the nine Austrian Federal Provinces were then mapped. Finally, these changes in relation to changes in planning frameworks were examined. After the descriptive analysis, the statistical-econometric analysis examined the potential correlations in more detail.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Descriptive analysis: land use in Austria

presents an overview of a range of indicators of land use. Roughly, 3700 km2 of Austrian land was built up (sealed) in 1996. In 2016, the last year of the observation period, 5600 km2 of land was consumed. This land consumption corresponds to 4.4% and 6.7% of the total territory of Austria, respectively. These figures may not be impressive given that the total area of Austria is about 83,900 km2; however, one has to consider that approximately 20% of the Austrian topography is mountainous and above the tree line; and 50% of Austria is covered by forests. This means that, in 2016, of the total, permanently habitable land [Dauersiedlungsraum] which includes all residential, commercial, infrastructure, and agricultural land, about 17% of the ground surface was sealed. The surface of the ground within municipal settlement borders is sealed even more – i.e. in 2016, it was to a degree of almost 50%.

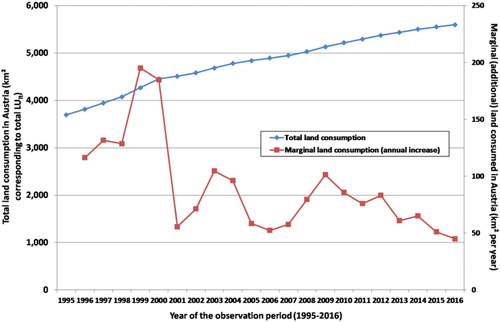

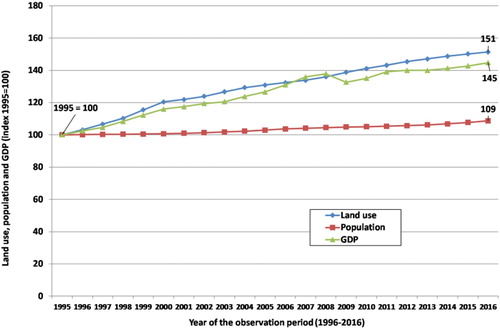

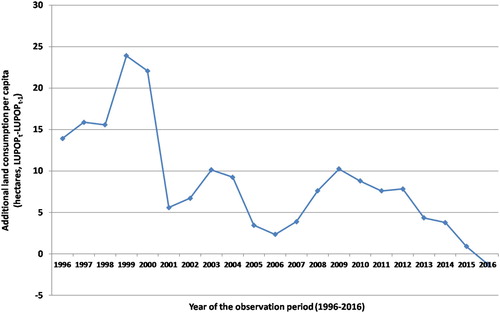

This development corresponds to an average daily land consumption of about 26 hectares. However, as as well as and indicate, marginal land use is slowing down. The daily average land consumption in the first ten years of the observation period from 1995 to 2005 amounted to about 33 hectares. From 2006 to 2016, about 20 hectares of land were sealed per day. Owing to the constant population growth and a constant decline of additional land use, the additional per-capita sealed ground was even slightly below zero in 2016 (). The total per-capita land consumption increased from 466 m2 to 649 m2; the population increased by roughly 8% and the population density decreased from 2147 to 1542 residents per km2 of the sealed ground. Demographic changes seem to further additional land consumption. The influence of economic growth is clearly visible in .

Figure 1. Total land consumption in Austria, and annual increase of land consumption (1995-2016). See for a description of the variables. Source: Own draft and calculations based on UBA (Citation2017) and STAT (Citation2017).

Figure 2. Total land consumption population and GDP growth in Austria (1995–2016; index 1995 = 100). See for a description of the variables. Source: Own draft and calculations based on UBA (Citation2017) and STAT (Citation2017).

Figure 3. Additional (increase) of land consumption per-capita (hectares per year). See for a description of the variables. Source: Own draft and calculations based on UBA (Citation2017) and STAT (Citation2017).

While shows both the increase of total land used, and additional sealed ground shows that land consumption increased by 50% over the past two decades, while the GDP increased by 45%; the population growth increased by approx. 9% – with a stronger growth rate in the following years after 2002/2003.

Therefore, land consumption – although slowing down now – is still a major environmental policy challenge. Land that is scarce is consumed and sealed, and thus removed from agricultural production. This is specifically relevant in those regions with the best soil quality and close to already existing residential and commercial areas.

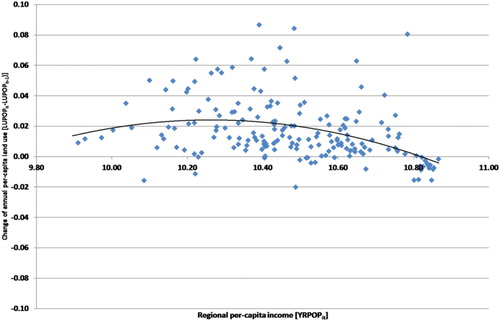

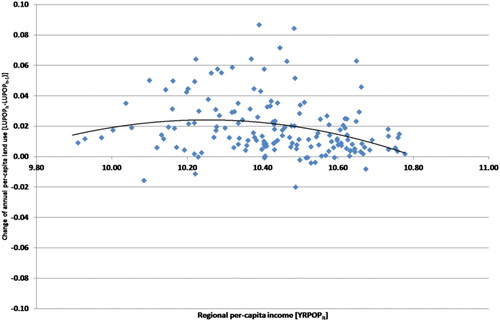

The EKC hypothesis briefly described in Sections 1 and 4.2 assumes a quadratic functional form between the GDP (per-capita at constant prices) and resource use, emissions, or – as in this case – land consumption. The current paper tests for common or different dependencies of land consumption and the GDP. therefore presents a scatterplot of the changes in land use (LUt − LUt−1) and regional GDP per-capita, i.e. the gross regional product of the nine Federal Provinces of Austria (see for a description of all of the GDP and land-use variables in this paper). As can be seen, there seems to be a slightly inverted U-shaped connection between the GDP per-capita and land use. However, this first impression has to be treated with caution, since the chart also includes the City of Vienna (which is not only a municipality, but also a Federal Province). For this reason, it has much higher GDP values than any of the other municipalities while, at the same time, it has a greater population density and thus a smaller per-capita degree of land consumption. Omitting Vienna from the data flattens the curve. Nonetheless, an inverted-U shaped function can still be detected.

Figure 4. The changes in per-capita land consumption, and regional per-capita GDP (with all nine Federal Provinces including Vienna). See for a description of the variables. Source: Own draft and calculations based on UBA (Citation2017) and STAT (Citation2017).

Table 3. Variables of the econometric estimations.

presents a similar picture by plotting (additional) per-capita land consumption (LUPOPt-LUPOPt-1), and regional GDP, but it excludes the City of Vienna. The EKC-compatible functional form is somewhat less pronounced since population growth reduces per-capita land consumption in addition to a diminishing marginal increase of land consumption in regard to the GDP.

Figure 5. The changes in per-capita land consumption, and regional per-capita GDP (In all nine Federal Provinces excluding Vienna). See for a description of the variables. Source: Own draft and calculations based on UBA (Citation2017) and STAT (Citation2017).

The inspection of the figures (especially and ) does not suggest a systematic pattern of land consumption in regard to the change of political frameworks. Rather, indicates that the periodic upward and downward developments of land consumption closely reflect economic development: the economic growth period until the burst of the dot-com bubble led to an increase of land consumption; after the recession of 2001, land consumption increased again and came to a peak in 2009. Land consumption began to decrease after the economic and financial crisis following 2009, and it is still decreasing.

In regard to the changes in the frameworks mentioned above and displayed in , there does not seem to be an apparent influence on land consumption, at least in the aggregate data; for instance, the Austrian sustainability strategy, issued in 2002, put forward a target of limiting land consumption to about 2 hectares per day. While daily land consumption is still about seven times higher than the political target, the development made since then does not indicate that this strategy has significantly influenced land consumption.

In order to analyse the potential correlations in more depth, it is necessary to turn to the statistical and econometric analysis.

4.2. Econometric analysis: the determinants of land consumption

The econometric analysis is basically a test of the EKC (Environmental Kuznets Curve) hypotheses as the underlying conceptual model that

the GDP (per capita) determines resource use, in this case, per-capita land consumption;

after a certain turning point, increasing the per-capita GDP leads to a reduction of additional (per capita) land consumption until the steady state in which GDP increases are achieved without further sealing of the land (i.e. land consumption comes to a halt); in other words, the GDP can be produced more efficiently in regard to land use;

land use will thus be decoupled from GDP growth.

As such, our operationalization of the conceptual model of the EKC hypothesis includes income (GDP), population, their changes over time, in a panel setting; i.e. we implicitly account for demographic changes and urbanization (e.g. urban development of Vienna). From this viewpoint, the EKC model is a macro model linking aggregate economic development to land use. However, in our analysis, we leave out other potential determinants of land use on the micro or meso levels such as land prices since such data are not available over time in the spatial aggregation that we are able to include.

Furthermore, to find out whether land use is also determined by the change of frameworks related to spatial planning and land consumption, further statistical tests were carried out. The empirical model consists of the following basic equation:(1a)

(1a)

(1b)

(1b) with LUit (LUPOPit) denoting total land consumption (total per-capita land consumption); the dependent variable will always be the change of land that is used from year t-1 to t. Subscript i indicates land use and the GDP of each of the nine Austrian Federal Provinces. Zit denotes a vector of additional variables depending on the equation. For instance, Zit includes the lagged land use variable (total or per-capita), dummy variables for the years of change when planning frameworks, and an autoregressive term AR(1). In addition, the model accounts for cross-section effects (fixed or random effects). For per-capita land use, the first equation will be used analogously.

Based on the description of the variables in , some of the variables are transformed into natural logs (ln). Taking the specification of the empirical equation of Bimonte and Stabile (Citation2017a) cited above, presents the results of a first set of estimations.

Table 4. Determinants of land use (total and per capita) in Austria: basic models.

The first estimation is a test of the change of land use (i.e. annual increase of land used for a given year) determined by income (GDP). In order to mirror the EKC hypotheses, the estimations follow a quadratic functional form for the GDP (variable YRPOPit). The results of the first estimation in indicate that GDP growth determines land use at a 10% level of significance. However, closer inspection of the estimation reveals that the level of the (lagged) variable of total land use and the auto-regressive term are highly significant. While the estimation has a Durbin-Watson statistic close to the optimal value of 2.0, and the F-statistic is highly significant, this specification seems mainly to be driven by the auto-regressive term. The explanatory power of the model measured by the adj. R2 is about 38% which is not entirely satisfying given the panel time series character of the data and the applied cross-section weights. Anyway, the significant quadratic functional form suggests that the annual change of land use (per capita) increases with a higher GDP (per capita), but at a diminishing rate. and have already indicated such a functional relationship. The econometric estimation therefore corroborates this preliminary finding.

includes two more econometric estimations that do not take the change of total land use as dependent variables but relate land use to the population in order to account for per-capita values and to capture the effects of demographic change. The second estimation deals with a specification that does not include fixed cross-section effects but accounts for random effects; furthermore, owing to the specification of the estimation (random effects), it is presented without an AR(1) term. While the explanatory power of the estimation is lower than that of the first estimation, the coefficients are of higher significance. However, the third estimation of has a much higher explanatory power than both estimations before, and shows (highly) significant coefficients. Again, the size and sign of the coefficients indicate that there is a quadratic functional form. Additional land use depends on the per-capita amount of land already used up to the previous year. This is also conforming to our expectations, since Federal Provinces with a high percentage of land that is sealed for residential, commercial and transport purposes leave less options for further land use.

The estimations in may be considered as a starting point to discuss the potential impacts of new spatial planning strategies, instruments and laws. As indicates, there are several regulatory reforms implemented in the nine Federal Provinces. Without going into detail (estimations can be provided upon request), none of the regulations at the Federal Province level had a significant effect on per capita land use and land consumption in any of the individual Federal Provinces.

However, as the estimations of may suggest, federal (national) regulations and frameworks seem to have some effect on marginal land use per capita. The fourth estimation of is a test to find out whether the Austrian sustainability strategy may have had some effect, or not. The estimation leads to a significant negative coefficient of the variable denoting the years from 2002 onwards. From a statistical perspective, after 2002, land use was – ceteris paribus – lower than before. The other coefficients remain in the same order of magnitude, but at a generally higher level of significance.

Table 5. Determinants of per capita land use in Austria: testing the influence of regulation.

The fifth estimation is a test of a similar influence of the ‘Austrian Ministry of the Environment’s’ 2008 guidelines to mobilize brown fields, and to re-develop and intensify uses of land (inward development). Again, the coefficient of this variable is highly significant while the other coefficients are stable. These results imply that these guidelines may also have an effect on land use policies.

In 2009, a new regulation was put into effect to allow a transparent assessment of land use with common methods and definitions, aiming at recording and raising awareness of land use and land consumption. The respective coefficient is also highly significant (sixth estimation) and therefore indicates that this regulation does have some influence on land use decisions.

It seems, however, that single regulatory steps and land use strategies may have only a combined effect; therefore, the last estimations were tests to assess the influence of all three Central Government policy frameworks in a joint model. The seventh estimation revealed that the significance of the coefficients that denote regulatory changes disappears. The results therefore indicate that a single strategy or policy document might not have a measurable effect when considered in a joint model. Rather, the variables for periods after the passing of such strategies reflect the general trend towards a reduction of additional annual land use. The lack of significance of the combined time variables suggests that this general trend may be caused by other determinants than regulatory changes.

The inclusion of a time trend variable for the different periods (e.g. from 2000 onwards) does not change the explanatory power of the model. Therefore, the significance of the time dummy variables in implies a certain downward shift of per-capita land use. However, this shift does not seem to follow a steadily decreasing trend. The growth and thus density of the population are more likely to reduce per-capita land use in cities than concrete policy instruments.

5. Discussion, conclusion and planning implications

Excessive land consumption may have a wide range of negative external effects, both in economic as well as environmental terms. The costs of infrastructure development (e.g. networks of roads, energy, water and sewage) are high in newly designated residential areas, especially in rural areas. These economic effects are relevant given narrow budgets in many municipalities in the current post-crisis context.

In this paper the determinants of land consumption in the econometric framework of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) are ascertained. Although land consumption represents a key dimension of environmental degradation and resource use, the determinants of land consumption have, so far, hardly been in the focus of the EKC concept (Bimonte & Stabile, Citation2017a).

The analysis shows an increase in land use efficiency and a decrease in marginal land consumption per capita. Evidence was found of a slightly inverted U-shaped relationship between GDP per-capita and land use, indicating to some degree the validity of the EKC thesis. This has to be treated with caution, as the city of Vienna is not only a municipality but also a Federal Province with a higher GDP than other municipalities, greater population density and thus less per-capita land consumption. This may generally distort the results. However, even when Vienna is excluded from the analysis, the EKC-compatible form is detectable, indicating a diminishing marginal increase in land consumption for built-up areas in regard to GDP. The econometric estimations indicate that land consumption continues to be dominated by increases in the GDP. However, this influence whenever GDP increases is gradually but steadily declining in the course of time (as indicated by the quadratic functional form of the estimated equation).

Planning policies and instruments, though, do not seem to make a clear-cut discernible difference. Although Austria ranks among the countries with the strictest planning frameworks in place, and new regulatory instruments and guidelines have recently been implemented to curb land consumption, the analysis does not reveal any statistically significant and discernible effect of spatial planning regulations, strategies and concepts on land consumption. None of the regulations issued by the Federal Provinces exert a statistically significant influence on land use in all provinces. At the Central Government level, the Austrian sustainability strategy, the ‘Austrian Ministry of the Environment’s’ 2008 guidelines, as well as the new regulation in 2009 that allows for a transparent assessment of land use with common methods and definitions, all show a highly significant coefficient in these estimations. This means that, in the period after 2002, when the policies were implemented, additional land consumption lessened. A general trend cannot be detected empirically. However, when Central Government policies are considered together, they no longer exert a statistically discernible influence, and so their relevance in the attempt to reduce land consumption is questionable.

Our results raise two broader questions. The first is what causes the relative decrease in land use for built-up areas, if it is not first and foremost planning? One factor to consider is the household income. As a major determinant of housing demand, stagnating or dropping incomes will slow down the supply of new housing and, as a consequence, the need for land use. Already in the years leading up to the ‘Global Financial Crisis’ of 2008, but particularly since then, the increases in household incomes in Austria have become less, with the first quartile (the poorest 25%) even experiencing a real income loss. The median income at constant prices increased only slightly between 2005 and 2016 (by +1.2%), while it decreased markedly for the quartile of households with the lowest income (−6.5%) (all data from STAT, Citation2018).Footnote1 If the development of household income plays an important part in reducing land use – and thus built-up areas – the recent decline in the marginal increase of land use may not be sustainable. Once income development catches up again, land use consumption levels may return to pre-crisis levels without changes in land use and zoning policy.

In addition to the arguments above, it seems that increasing land prices have played an important role in slowing down further land use, especially over the past ten years. Prices have increased significantly in recent years, with particular growth in and around urban areas (especially in Vienna). As land prices increase, households purchase less and then smaller plots to build on, particularly in times of stagnating incomes. Furthermore, newly built flats are often smaller than the older ones, owing to high per-m2 prices. As land is becoming scarcer, and more permanently habitable areas are sealed, municipal decision makers are becoming more reluctant to convert agricultural land to become residential areas, even if land owners put pressure on them to do so in order to earn windfall profits from rising prices. An additional factor is urbanization, relating to less intense land use in urban areas as compared with rural ones (e.g. multi-storey building vs. detached single-family homes). Urbanization has gained in size at a significant rate in recent years and in several cities in Austria the population has gained in size more than the rural areas, although ongoing sub-urbanization processes have paralleled this development. Population density has especially increased in urban areas. Vienna – by far the biggest city of Austria with a population of 1.8 million – has gained more than 200,000 new residents in the last ten years alone, a significant number of whom have migrated from rural areas (Stadt Wien, Citation2018). Meanwhile, the high prices for land in the cities lead to the construction of smaller housing units and reduced dwelling size, are an incentive for more efficient land use patterns.

The second issue that the analysis brought into question was how to account for the apparent insignificance of planning measures in reducing land loss. A key point to consider in this regard may relate to the regulatory form and the fragmented set-up of the Austrian planning system. On the one hand, several concepts to reduce land consumption were implemented at the Central Government level. However, they are all strategic concepts and legally non-binding. Thus, in practice, municipalities are not forced to change their way of making decisions, despite federal recommendations to do so. Meanwhile, legal changes have been made at the provincial level by confronting the municipalities with new legal frameworks for local development and zoning. Anyway, it is still the responsibility of municipalities to enforce these new rules, despite the supervisory role of Federal Provincial Governments. The results of this paper cast doubt on whether local governments have adapted their way of decision-making to conform with the new policy frameworks. However, our dataset has allowed only tracking changes to planning regulations and parallel changes in land use only on Central Government and Federal Province levels. Further research is also required in regard to how municipal decision-making reacts to changes in the legal frameworks.

On the other hand, the limited influence of planning measures relates to the status quo of zoned land. As mentioned above, almost one-third of the land that is currently designated for construction in Austria is undeveloped. Some Federal Provinces have implemented measures to mobilize this land as part of the implemented legal changes by, for example, introducing instruments to re-arrange plot boundaries (Lower Austria, Tyrol). Meanwhile, at the Central Government level, strategies to mobilize such land have been introduced. Nonetheless, most of the implemented legally binding instruments relate to land that is newly zoned, which has diminished the effectiveness of the measures taken. Still, land taxes are generally too low to provide an incentive for more efficient land use.

What are the conclusions that can be drawn for planning? Land consumption measured by annual marginal land sealing is still one of the highest in Austria compared with other European countries. Besides residential development, land use is driven by the expansion of infrastructure (e.g. highways and other roads, railroads). Additional land consumption has dropped from 33 hectares per day (1996–2006) to about 20 hectares (2007–2016); this corresponds to an additional per-capita land consumption of about 11.7 m2 (1996-2006) and 5.4 m2 (2007-2016). Still, the ‘Austrian Strategy for Sustainable Development’ aims at reducing the total additional land consumption to 2 hectares per day. Therefore, reality is indeed far away from officially stated political concepts and objectives. The reduction of additional per-capita land consumption within a given period of time is certainly a first priority, but not a sufficient measure for more sustainable land use. Therefore there is the urgent need to develop new and more effective spatial planning instruments to supplement the current frameworks, and to implement existing policies more effectively.

‘The Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning’ (ÖROK) recommends eight measures to curb land consumption through effective local planning measures (ÖROK, Citation2017, p. 16f) namely:

to include long-term guidelines on land use in the local development plans, encompassing, at minimum, an analysis of required land for building purposes, and strategic objectives for future land consumption;

to apply restrictive criteria for newly zoned land according to local needs;

to make use of compact zoning that integrates new land for building purposes into existing settlement structures;

to reduce the extent of existing, undeveloped land for building purposes by withdrawing building rights on existing land and by issuing time-limited permits to obtain new land for building purposes;

to introduce a new category building ban into zoning plans to protect valuable land;

to restrict holiday and secondary homes;

to prevent construction activities outside the land designated for building purposes; and

to reduce occasion-related zoning and, as far as possible, to relate zoning to the strategic development plans of the municipality.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are, of course, the responsibility of the authors. The authors thank M. Galka for research assistance with regard to a previous version of the underlying database. The authors acknowledge financial support by the TU Wien University Library Open Access Funding Programme.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 While Austrian GDP grew by a much larger rate, the small increase in median income per employee is due to the significant increase in part-time and low-paying jobs.

References

- Anthony, J. (2004). Do state growth management regulations reduce sprawl? Urban Affairs Review, 39, 376–397. doi: 10.1177/1078087403257798

- Bengston, D. N., & Youn, Y.-C. (2006). Urban containment policies and the protection of natural areas: The case of Seoul's greenbelt. Ecology and Society, 11(1), article 3. https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/4920 doi: 10.5751/ES-01504-110103

- Bimonte, S., & Stabile, A. (2017a). Land consumption and income in Italy: A case of inverted EKC. Ecological Economics, 131, 36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.08.016

- Bimonte, S., & Stabile, A. (2017b). EKC and the income elasticity hypothesis – land for housing or land for future? Ecological Indicators, 73, 800–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.10.039

- BMLFUW (Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft). (2011). Grund genug? Flächenmanagement in Österreich. Fortschritte und Perspektiven. Vienna: Author.

- Calabrese, S., Epple, D., & Romano, R. (2007). On the political economy of zoning. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 25–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.09.004

- Caldera, A., & Johansson, A. (2013). The price responsiveness of housing supply in OECD countries. Journal of Housing Economics, 22, 231–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jhe.2013.05.002

- Chakir, R., & De Gallo, J. (2013). Predicting land use allocation in France: A spatial panel data analysis. Ecological Economics, 92, 114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.04.009

- Colsaet, A., Laurans, Y., & Levrel, H. (2018). What drives land take and urban land expansion? A systematic review. Land Use Policy, 79, 339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.08.017

- Dinda, S. (2004). Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis. A survey. Ecological Economics, 49, 431–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.02.011

- Ekins, P. (1997). The Kuznets curve for the environment and economic growth: Examining the evidence. Environment and Planning A, 29, 805–830.

- European Communities. (2011). Report on best practices for limiting soil sealing and mitigating its effects (Final report). Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c20f56d4-acf0-4ca8-ae69-715df4745049/language-en.

- Faludi, A. (2000). The Performance of spatial planning. Planning Practice and Research, 15, 299–318. doi: 10.1080/713691907

- Friedl, B., & Getzner, M. (2003). Determinants of CO2 emissions in a small open economy. Ecological Economics, 45, 133–148. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(03)00008-9

- Gallardo, M., & Martínez-Vega, J. (2016). Three decades of land-use changes in the region of Madrid and how they relate to territorial planning. European Planning Studies, 24, 1016–1033. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1139059

- Gehrke, E., & Hartwig, R. (2018). Productive effects of public works programs: What do we know? What should we know? World Development, 107, 111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.031

- Gennaio, M. P., Hersperger, A. M., & Bürgi, M. (2009). Containing urban sprawl – Evaluating effectiveness of urban growth boundaries set by the Swiss land use plan. Land Use Policy, 26, 224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.02.010

- Getzner, M. (2009). Determinants of (de-)materialization of an industrialized small open economy. International Journal of Ecological Economics and Statistics, 14(1), 3–13.

- Getzner, M. (2012). Gesamtwirtschaftliche Wirkungen von Infrastrukturinvestitionen. Wirtschaftspolitische Blätter, 59(3), 371–387.

- Getzner, M. (2017). Innovative vertragliche Instrumente der Stadtentwicklungs- und Wohnpolitik aus ökonomischer Sicht. In J. Suitner, R. Giffinger, & L. Plank (Eds.), Jahrbuch Raumplanung 2017 (pp. 83–95). Vienna: NWV – Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag.

- Geurs, K. T., & van Wee, B. (2006). Ex-post evaluation of thirty years of compact urban development in the Netherlands. Urban Studies, 43, 139–160. doi: 10.1080/00420980500409318

- Green, R. K., Malpezzi, S., & Mayo, S. K. (2006). Metropolitan-specific estimates of the price elasticity of supply of housing, and their sources. American Economic Review, 95, 334–339. doi: 10.1257/000282805774670077

- Haase, D., Seppelt, R., & Haase, A. (2008). Land use impacts of demographic change – lessons from Eastern German urban regions. In I. Petrosillo, F. Müller, K. B. Jones, G. Zurlini, K. Krauze, S. Victorov, B.-L. Li, & W. G. Kepner (Eds.), Use of Landscape Sciences for the assessment of environmental security. NATO Science for Peace and Security series C: Environmental Security (pp. 329–344). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Halleux, J. M., Marcinczak, S., & van der Krabben, E. (2012). The adaptive efficiency of land use planning measured by the control of urban sprawl – The cases of the Netherlands, Belgium and Poland. Land Use Policy, 29, 887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.01.008

- Hilber, C. A. L., & Robert-Nicoud, F. (2013). On the origins of land use regulations: Theory and evidence from US metro areas. Journal of Urban Economics, 75, 29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2012.10.002

- Humer, A. (2017). Linking polycentricity concepts to periphery: Implications for an integrative Austrian strategic spatial planning practice. European Planning Studies, 26, 635–652. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1403570

- Jones, A., Panagos, P., Barcelo, S., Bouraoui, F., Bosco, C., Dewitte, O., … Yigini, Y. (2010). The state of soil in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Krausmann, F., Gingrich, S., Eisenmenger, N., Erb, K.-H., Haberl, H., & Fischer-Kowalski, M. (2009). Growth in global materials use, GDP and population during the 20th century. Ecological Economics, 68, 2696–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.05.007

- Lanegger, J., & Froehlich, G. (2014). Bodenlos? Flächeninanspruchnahme in Österreich. Arbeiterkammer Niederösterreich, Arbeiterkammer Niederösterreich.

- Lauf, S., Haase, D., & Kleinschmit, B. (2014). Linkages between ecosystem services provisioning, urban growth and shrinkage – A modeling approach assessing ecosystem service trade-offs. Ecological Indicators, 42, 73–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.01.028

- Mardani, A., Streimikiene, D., Cavallaro, F., Loganathan, N., & Khoshnoudi, M. (2019). Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and economic growth: A systematic review of two decades of research from 1995 to 2017. Science of the Total Environment, 649, 31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.229

- Newman, P., & Thornley, A. (1996). Urban planning in Europe: International competition, national systems, and planning projects. London: Routledge.

- ÖROK. (2017). ÖROK Empfehlung Nr. 56: Flächensparen, Flächenmanagement & aktive Bodenpolitik. Wien: Author.

- ÖROK. (2018). ÖROK Rechtssammlung – Abschnitt II: Rechtssammlung. Retrieved fro https://www.oerok.gv.at/raum-region/daten-und-grundlagen/rechtssammlung/rechtschronik.html

- Prokop, G., Jobstmann, H., & Schönbauer, A. (2011). Overview of best practices for limiting soil sealing or mitigating its effects in EU-27. Final report to the European Commission, DG Environment, Brussels.

- Salvati, L., Zambon, I., Chelli, F. M., & Serra, P. (2018). Do spatial patterns of urbanization and land consumption reflect different socioeconomic contexts in Europe? Science of the Total Environment, 625, 722–730. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.341

- Siedentop, S., Fina, S., & Krehl, A. (2016). Greenbelts in Germany’s regional plans - An effective growth management policy? Landscape and Urban Planning, 145, 71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.09.002

- SIR. (2016). Baulandmobilisierung und Flächenmanagement. Salzburger Institut für Raumordnung & Wohnen (SIR), Salzburg.

- Smiraglia, D., Ceccarelli, T., Bajocco, S., Salvati, L., & Perini, L. (2016). Linking trajectories of land change, land degradation processes and ecosystem services. Environmental Research, 147, 590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.11.030

- Stadt Wien. (2018). Bevölkerungsstand [Population numbers]. Retrieved from https://www.wien.gv.at/statistik/bevoelkerung/bevoelkerungsstand/

- STAT. (2017). Data retrieved from Statistik Austria’s data bank on regional GDP, population, and land use aggregates. Vienna: Author. Retrieved from statistik.a.

- STAT. (2018). Data retrieved from Statistik Austria on annual person income of employees 2005-2016; on consumer price index (CPI). Vienna: Author. Retrieved from statistik.at.

- Stead, D., & Meijers, E. (2009). Spatial planning and policy integration: Concepts, facilitators and inhibitors. Planning Theory & Practice, 3, 317–332. doi: 10.1080/14649350903229752

- Steinberger, J. K., Krausmann, F., Getzner, M., Schandl, H., & West, W. (2013). Development and dematerialization: An international study. PLoS One, 8(10), 1–11. Paper No. e70385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070385

- Stern, D. (2004). The rise and fall of the environmental Kuznets curve. World Development, 32, 1419–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.03.004

- Stoeglehner, G. (2010). Enhancing SEA effectiveness: Lessons learnt from Austrian experiences in spatial planning. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 28(3), 217–231. doi: 10.3152/146155110X12772982841168

- Turner, K. G., Anderson, S., Gonzales-Chang, M., Costanza, R., Courville, S., Dalgaard, T., … Wratten, S. (2016). A review of methods, data, and models to assess changes in the value of ecosystem services from land degradation and restoration. Ecological Modelling, 319, 190–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2015.07.017

- UBA. (2016). Elfter Umweltkontrollbericht. Umweltsituation in Österreich. Umweltbundesamt. Retrieved from www.umweltbundesamt.at/fileadmin/site/publikationen/REP0600.pdf

- UBA. (2017). Landnutzung und Flächeninanspruchnahme. Vienna: Austrian Environmental Protection Agency (Umweltbundesamt, UBA). Retrieved from umweltbundesamt.at

- Weitz, J., & Moore, T. (1998). Development inside urban growth boundaries.: Oregon's empirical evidence of contiguous urban form. Journal of the American Planning Association, 64, 425–440. doi: 10.1080/01944369808976002

- Xepapadeas, A. (2005). Economic growth and the environment. In K. G. Mäler, & J. R. Vincent (Eds.), Handbook of environmental economics (Vol. 3, pp. 1219–1271). Amsterdam: North Holland.