ABSTRACT

Empirical research on urban shrinkage is being conducted around the globe, since many countries are confronted with the phenomenon of shrinking cities. So far, the research on urban shrinkage has focused strongly on case studies, which is why we can benefit from a diverse and empirically rich knowledge base on the phenomenon and its regional manifestations. By bridging and comparing the European and Japanese academic discourse, we aim to identify the different recurring theories and key issues discussed under the umbrella term ‘urban shrinkage’ and strive to uncover blind spots of the debate. For this purpose, we conduct a qualitative meta-analysis of 100 empirical cases that are documented in the literature dealing with shrinking cities in the EU and Japan. This meta-analysis is based on comparative qualitative content analysis. It reveals a regionally differentiated pattern of various causes, effects and responses documented for shrinking cities in Western, Mediterranean and post-socialist EU countries and in Japan. Based on these findings, we offer an agenda for future research by suggesting an integrative perspective on the context-specific dynamics of urban shrinkage. We argue for an integrative understanding of shrinking cities in order to develop a valid knowledge base for evidence-based policy recommendations.

Introduction

Over recent decades, urban shrinkage has become a global phenomenon (Richardson & Nam, Citation2014). As cities are shrinking in different parts of the world, there are several national strands of research focusing on different aspects and manifestations (Pallagst, Wiechmann, & Martinez-Fernandez, Citation2013). It is only in the last few years that an international discourse has started to bridge these national debates (Martinez-Fernandez, Audirac, Fol, & Cunningham-Sabot, Citation2012). Next to inner-European comparisons (Haase, Bernt, Großmann, Mykhnenko, & Rink, Citation2016a; Mykhnenko & Turok, Citation2008; Turok & Mykhnenko, Citation2007; Wolff & Wiechmann, Citation2017), cross-continental comparisons dealing with shrinkage in Europe (particularly in Germany) and in the US were published (Pallagst, Fleschurz, & Said, Citation2017; Zingale & Riemann, Citation2013). However, different national and regional strands of research are still unevenly represented in the international discourse. Recently, urban shrinkage discourse has become broader and has started to look at the phenomenon in countries like Australia, Japan and Russia (Batunova & Gunko, Citation2018; Mallach, Haase, & Hattori, Citation2017; Martinez-Fernandez et al., Citation2016). Cross-continental studies that offer a comparative analysis of urban shrinkage and explore governance responses in different national contexts are still at an early stage. These comparative studies increase the visibility of the previously less known and accessible debates in the international community and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of urban shrinkage. This article draws on the emerging cross-continental debate by providing a qualitative meta-analysis of prevalent topics and blind spots in the literature dealing with shrinking cities in the EU and Japan.

As the research on urban shrinkage is strongly case-study-based, we can benefit from diverse and empirically rich knowledge about the phenomenon and its regional manifestations. The case studies draw on diverse theoretical frameworks and thus far the debate lacks a common theoretical foundation (Haase, Nelle, & Mallach, Citation2017; Sousa & Pinho, Citation2015). However, since the turn of the millennium, scholars have driven a theoretical debate on urban shrinkage by developing typologies, conceptual approaches, or heuristic models based on inductive theorizing (Haase et al., Citation2016a; Haase, Rink, Großmann, Bernt, & Mykhnenko, Citation2014; Wolff & Wiechmann, Citation2017).

Although there are global macro-trends that change cities worldwide, there are socio-cultural, demographic, political and economic conditions that vary by regional context and shape the pathways of shrinking cities and consequently the national discourses (Haase et al., Citation2017). Numerous single and comparative case studies show that, within Europe, shrinking cities manifest themselves in different ways (Haase et al., Citation2016a). How regional conditions and debates frame urban shrinkage processes becomes even more apparent when comparing shrinking cities in the EU and Japan. In Europe (and in the US) urban shrinkage, according to the literature, is closely associated with economic decline, while urban shrinkage in Japan is closely linked to demographic factors. As population loss and ageing have been challenging Japanese regions and cities for many decades, population shrinkage has been a very popular theme for academics in Japan (Hattori, Kaido, & Matsuyuki, Citation2017). The demographic change is also an increasing challenge for shrinking cities in Europe, as low fertility and ageing can cause and exacerbate problems of urban shrinkage. Regarding these developments, we argue that the Japanese debate provides important lessons for identifying blind spots in the literature dealing with shrinking cities in the EU and reflecting the role of demographic change in these cities.

Against this background, we draw upon a variety of case studies and systematically review the various causes, effects and responses offered in the empirical literature on shrinking cities in EU and Japan. In so doing, we outline and compare the theoretical explanations and empirical dimensions of urban shrinkage in a cross-continental meta-analysis, based on a comparative content analysis. Although several literature reviews about urban shrinkage have been published (Cunningham-Sabot, Audirac, Fol, & Martinez-Fernandez, Citation2013; Hoekveld, Citation2014; Reis, Silva, & Pinho, Citation2016), a systematic meta-analysis has not thus far been conducted. Based on the findings of our meta-analysis, this comparative article has a twofold goal. Firstly, it sketches out the prevalent and recurring topics in the empirical literature in EU and Japan and, secondly, based on these results, it provides an agenda for further empirical research on urban shrinkage.

This paper is structured as follows: first, we explain the scope of and the methodology used in the meta-analysis. In the results section, we report on the theoretical and empirical explanations of urban shrinkage as identified in the literature dealing with cities in the EU and Japan. In what follows, the results are carefully interpreted and compared with previous comparative research on shrinking cities, before concluding with a research agenda proposing an integrative perspective on the dynamics of shrinking cities.

Methodical approach and scope of the meta-analysis

As urban shrinkage is a multifaceted phenomenon concerning cities of various sizes and types across the globe, we begin by defining the substantive scope of the meta-analysis. First, we want to clarify what the term ‘urban’ comprises in the strands of literature dealing with EU and Japanese cases. When analysing empirical studies dealing with urban shrinkage, it becomes obvious that a broad range of city types are summarized under the term ‘urban’. Aside from large cities with more than 200,000 residents (Bontje, Citation2004; Rink, Haase, Grossmann, Couch, & Cocks, Citation2012; Sato & Morimoto, Citation2009), there are also small and medium-sized cities with little more than 5,000 residents (Alves, Barreira, Guimarães, & Panagopoulos, Citation2016; Kotilainen, Eisto, & Vatanen, Citation2015), which are studied under the term ‘shrinking city’. Furthermore, there are articles that focus on the metropolitan area or on parts of cities, like the inner city or the urban fringe (Elzerman & Bontje, Citation2015; Hara & Asano, Citation2014; Ohno et al., Citation2006).

Second, the international discourse lacks a common definition but instead offers several approaches for trying to define the term ‘shrinkage’ through qualitative and quantitative characteristics. A quite frequently used definition, for instance, is given by Wiechmann and Bontje (Citation2015, p. 5), who define a shrinking city as ‘a densely populated urban area with a minimum population of 10,000 residents, which has faced population losses in large parts for more than two years and is undergoing economic transformations with some symptoms of a structural crisis’. In the European discourse, most scholars agree on a loss of population as a necessary characteristic for the phenomenon of urban shrinkage. Similarly, the Japanese discourse characterizes shrinkage as long-term depopulation caused by demographic factors like ageing and low birth rates (Hattori et al., Citation2017). For the meta-analysis, we do not exclude certain definitions of urban shrinkage a priori. In order to reflect the existing scientific discourse, we also consider papers that use the terms ‘shrinking cities’ or ‘urban shrinkage’. In brief, the selection of articles for our meta-analysis includes urban neighbourhoods, cities or agglomerations of different sizes and trajectories, which are experiencing or have experienced an episodic, long-term or continuous decline in population.

With this in mind, the article systematically explores empirical case studies dealing with cities in the EU and Japan in order to address the following research questions:

How is the phenomenon of urban shrinkage explained and discussed theoretically in the literature on shrinking cities in the EU and Japan?

Which causes, effects and responses can be identified in the empirical studies? Are there regional key issues or blind spots and how can they be explained and interpreted?

Which lessons can be learnt from the empirical knowledge bases in different geographical contexts for future research?

We address these questions by applying a meta-analysis, which, in the past, has hardly been attempted in non-clinical research and was only rarely used to synthesize qualitative research. This type of analysis first appeared when the sociologist Charles Ragin (Citation1987) developed qualitative comparative analysis to evaluate context-specific circumstances related to macro-social and political developments such as peasant revolts, regime failure and ethnic political mobilization. We will conduct a qualitative comparative meta-analysis to transform the findings in 70 scientific papers of 100 empirical cases into contingency tables in order to reveal the key issues and blind spots of the respective regional debates. We used the database Scopus to search for empirical case studies dealing with shrinking cities in the EU and the academic database CiNii to search for scientific papers published in academic journals and books in Japan. The search string for EU cases was ‘shrinking city OR urban shrinkage OR urban decline OR Schrumpfung OR schrumpfende Stadt’. We included the German terms for shrinkage, as, after reunification, the rapid shrinkage of German cities broadly influenced the urban shrinkage debate in the last decades (Nelle et al., Citation2017). The search for Japanese papers included the following translated terms: ‘shrinking city OR shrinking OR depopulation’. This would allow papers that not only explicitly use the term ‘urban shrinkage’ to appear but also similar terms that are often used synonymously (Fol & Cunningham-Sabot, Citation2010; Großmann, Bontje, Haase, & Mykhnenko, Citation2013). At least one of the terms must be part of the title or the abstract of the selected papers. The search was limited to scientific articles (and those in press) as well as book chapters in English, German or Japanese in the field of social science. We took into account the period from 2005 to (30 September) 2017, when the debate in Europe began to heat up due to the project and the following publication series Shrinking Cities (Oswalt, Citation2005, Citation2006; Oswalt & Rieniets, Citation2006). Publications that provide no empirical results for the phenomenon of urban shrinkage or lack a clear geographical focus on at least one city were excluded from the analysis. We included single cases, comparative case studies (more cities in one country) and cross-national comparisons in the analysis. When comparative studies deal with more than one city in a qualitative way, we analysed each city as a single case in order to be able to distinguish the geographical context.

For the analysis, we compare the well-developed empirical discourse on urban shrinkage in the EU with the emerging debate on urban shrinkage in Japan. Both, the EU and Japan are highly developed regions affected by widening spatial disparities and depopulation processes. Although, the EU member states and Japan provide different forms of government (unitary and federal systems), there is a close degree on many aspects on economic and demographic developments. We see merits in contrasting the variety of shrinkage in EU with the demographic focus on shrinkage in Japan. In terms of low birth rates, ageing population and demographic decline, Japan shows one of the most dramatic situations and has a rapid increase of shrinking cities (Wirth, Elis, Müller, & Yamamoto, Citation2016). However, literature on shrinking cities in Japan has been, compared to the North American discourse (e.g. Shetty & Reid, Citation2014; Wiechmann & Pallagst, Citation2012; Zingale & Riemann, Citation2013) underrepresented in the international perspective and cross-national comparisons so far. In comparing the literature on EU and Japanese cities, we see potentials to get a better understanding of how patterns of the global phenomenon of urban shrinkage are discussed regionally.

We distinguished between the regions of Western Europe, Mediterranean Europe, post-socialist Europe and Japan based on the locations of the shrinking cities. For the region of Western Europe, we mainly included case studies from France, Western Germany and the UK. For the region of Mediterranean Europe, we took into account cities in Southern Europe, including in Italy, Spain and Portugal. The shrinking cities of the former Eastern Bloc countries (EU member states), including East Germany, we considered for the region of post-socialist Europe. The post-socialist transition that occurred after the political change in Central and Eastern EU countries caused a unique combination of demographic and economic effects that resulted in a high number of rapidly shrinking cities (Cunningham-Sabot et al., Citation2013). Due to the specific circumstances of the German reunification, the East German cities are addressed separately in the following sections.

In order to answer the first research question concerning theoretical explanations of urban shrinkage, we initially analysed the theoretical discourse in a qualitative way. To analyse how urban shrinkage is argued and explained empirically we draw upon a heuristic classification of causes, effects and responses, as these three aspects of shrinkage are essential in (almost) all of the reviewed studies. The categories of causes, effects and responses were derived inductively from the material during the analysis of the case studies and evaluated quantitatively. We included those causes, effects and responses that were highlighted or discussed as a priority in the studies. It is important to say, that, in particular, the categories of causes and effects cannot always be clearly differentiated or attributed, as different factors are interrelated and can mutually influence each other. However, we follow the prevalent classification and descriptions as presented in the empirical case studies. The mapped data were transferred into descriptive tables and, in a second step, translated into contingency tables which were used for frequency analysis, in order to evaluate the collected qualitative data of the papers regarding the frequencies of the categories. Subsequently, the results are discussed and, based on this, a research agenda is provided.

Theoretical and empirical explanations of urban shrinkage in Europe and Japan

For the meta-analysis, we analysed 70 papers of the European and Japanese urban shrinkage discourse (see the full reference list that is available online as supplemental data). Of these, 17 papers provide (cross-) national comparisons, whereas the remaining papers focus on single cases. In total, the papers provide 100 cases of shrinking cities.

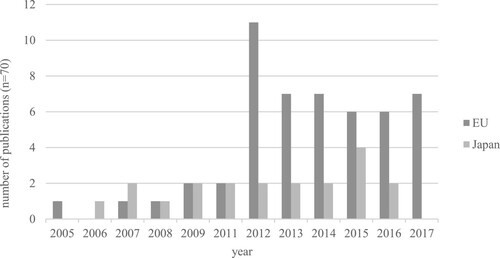

In Europe, urban and economic developments associated with urban shrinkage, such as deindustrialization and housing vacancies, already began to appear in scientific and policy debates in the 1970s (Martinez-Fernandez et al., Citation2012). The beginning of a broader scientific debate on urban shrinkage, however, dates back to the mid-2000s and reached its peak in the year 2012 (see ). While causes and effects dominated past studies, more recent empirical research on shrinking cities in Europe shows an increasing shift towards governance responses. In Japan, the term shrinking cities [縮小都市] is relatively new in academic debate as, traditionally, most of the research on shrinkage has focused on rural areas and municipalities. The term ‘shrinking cities’ first appeared in the Japanese literature in the year 2000 but, initially, only in papers dealing with urban shrinkage in Europe or the US. Most of the analysed articles focus on the evaluation of planning policies that mainly seek to manage the built environment, whereas theoretical and conceptual perspectives tend to fall short in the Japanese literature (Okabe, Citation2010).

Studies concerning cities in Western and post-socialist Europe dominate the sample (each category makes up roughly 30%). Of the case studies, 11% deal with urban shrinkage in Mediterranean Europe and 20% focus on Japanese shrinking cities. Seven North American cities are not covered in the meta-analysis but were comparatively discussed in some European papers. This uneven spatial distribution results from the systematic selection of studies and should be taken into account when reading the following results. Over half of the cities have more than 200,000 inhabitants, while only one-third of the cases focus on (small- and) medium-sized cites. The remaining studies focus on various scales or parts of the cities.

As mentioned before, there is no universal definition of the term ‘urban shrinkage’. Two-thirds of the given definitions focus on population decline as the major dynamic. One quarter of the articles also mention the dimension of economic decline, whereas multidimensional definitions are barely used. Before discussing the empirical factors linked to urban shrinkage in the European and Japanese case studies, we provide a brief overview of the theoretical explanations identified in the European and Japanese literature.

Theoretical explanations of urban shrinkage

Urban shrinkage is connected to a variety of theories and theoretical concepts in both the European and the Japanese discourse. These range from theories of migration and political power to economic polarization and aim either at explaining the causalities of, or dealing with, urban shrinkage.

The majority of current research examines theoretical concepts of globalization processes and uneven development as drivers for urban shrinkage. These polarization processes (dating back to the origins of Myrdal, Citation1957) are found to result in growing economic inequalities between the cities. Some cities succeed in this global network of comparative advantage and specialization, while others fail and face a decline in population (Couch & Cocks, Citation2013; Cunningham-Sabot et al., Citation2013). Plöger and Weck (Citation2014) widen this theoretical perspective by drawing on the multidimensional concept of peripheralisation, a central component of which is the socio-spatial production of centres and peripheries through actors.

Aside from these macro-scale approaches, the topic of suburbanization provides a frequent explanation for urban shrinkage in both the European and the Japanese discourse. Suburbanization processes are linked to population and business migration from the urban centres to the urban fringes of the cities and their surrounding zones (Tanaś & Trojanek, Citation2015). The Japanese discourse focuses on the spatial dimension of suburbanization and highlights the uncontrolled expansion of cities by referring to the concept of urban sprawl (Iwasaki, Iwamoto, Matsukawa, Nakade, & Higuchi, Citation2007; Yamashita & Morimoto, Citation2015). In this context, suburbanization is attributed to rapid ageing, housing vacancy and the urban decay of inner cities (Shimizu & Sato, Citation2011).

The process of suburbanization is also one of the stages of the urban life-cycle model, which was adopted by some scholars in the European and Japanese urban shrinkage discourse. The Chicago School first established this model in the 1920s at the scale of urban neighbourhoods. The approach highlights the evolutionary characteristics of population development and describes alternating dynamics of population growth and shrinkage. Some authors distinguish between four cyclic stages of urban life: urbanization, suburbanization, dis-urbanisation and re-urbanisation (Couch & Cocks, Citation2013; Kabisch & Grossmann, Citation2013; Kim, Onishi & Suga, Citation2007).

An emerging theoretical approach in European and Japanese literature, which also highlights the evolutionary perspective on shrinking cities, is that of resilience (Okabe, Citation2010). The concept originally evolved in the discipline of ecology and can be defined as ‘the capacities of a system to maintain its core functions’ when hit by sudden changes (Kotilainen et al., Citation2015, p. 58). In recent years, concepts of resilience have increasingly raised attention in the research on urban shrinkage. Concepts of resilience are connected to sustainable development and are often applied to investigate shrinking cities from a long-term perspective (Alves et al., Citation2016; Okabe, Citation2010). In this context, cities are defined as complex and adaptive systems which have the ability to react to external shocks (e.g. natural disasters or economic crises). Cities and their communities are considered to have the capacity to adapt, to transform or to resist disturbances and to maintain their economic, social and environmental functions. According to Kotilainen et al. (Citation2015), resilience provides a conceptual tool to explain why some cities overcome a shock and recover while others do not. Moreover, Alves et al. (Citation2016) argue that resilience is a fruitful approach to identify shrinking cities’ strength and capacities in order to formulate appropriate policies.

Recently, studies have increasingly focused on governance as a conceptual and analytical tool to sketch out how public and private actors plan and manage the challenges of shrinking cities. Bernt (Citation2009), for example, introduced the term ‘grant coalitions’ (instead of growth) between municipal authorities and housing companies in the East German regeneration programme ‘Stadtumbau Ost’ as a new mode of governance. In the more recent past, scholars have stressed the importance of integrating the third sector in governance processes when discussing depopulation and concepts like social cohesion (Cortese, Haase, Großmann, & Ticha, Citation2014) or co-production (Schlappa, Citation2017).

Causes of urban shrinkage

Although the clear majority of the papers we analysed view population loss as the fundamental aspect of the term ‘urban shrinkage’, in Europe this narrative has a strong economic dimension. As shown in , urban shrinkage is predominantly linked to deindustrialization processes in studies focusing on Western Europe (46%). For instance, a significant number of empirical studies in the UK deal with the transformation of former industrial cities like Liverpool or Manchester. Cities in the UK faced the challenge of deindustrialization earlier than did continental Europe, and most have already reached a critical turning point. The majority of the formerly shrinking cities in the UK have overcome processes of deindustrialization and are experiencing a population increase; however, they are still coping with the societal challenges brought about by rapid economic decay during the 1990s (Mace, Hall, & Gallent, Citation2007; Ortiz-Moya, Citation2015; Rink, Citation2012).

Table 1. Causes of urban shrinkage by region (in order of decreasing shares of cases mentioning specific causes).

Deindustrialization also seems to be the major topic for shrinking cities in Mediterranean (31%) and post-socialist Europe (32%). Reinforced by the post-socialist transformation of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), the cities in Eastern Germany were particularly hit by the decline in industry.

Suburbanization (or urban sprawl) is the second most discussed effect on shrinking cities. Nineteen per cent of all cases are concerned with suburbanization processes. This term describes the migration of residents and functions from the inner city to the city region. Suburbanization and its link to urban shrinkage is one of the major topics in the Japanese context (32%). Urban shrinkage processes in Central and Eastern Europe, including Eastern Germany, are mainly driven by the post-socialist transformation that has severely affected the cities’ demographic and economic development. Qualitative content analysis further shows that out-migration is closely linked to the shrinkage debate in Europe, due to its direct impact on population decline. The Japanese literature focuses mostly on demographic change, which is characterized by low birth rates and an ageing population. Environmental pressures like pollution or climate change are addressed as drivers for urban shrinkage for some Mediterranean cities – the Italian industrial city of Taranto, for instance, suffered from massive water and air pollution caused by iron industries in recent decades (Camarda, Rotondo, & Selicato, Citation2015). One effect of this deterioration is out-migration. In some Portuguese coastal cities, severe climatic conditions like drought and heatwaves affect the environment and are seen as factors that also cause out-migration (Barreira, Agapito, Panagopoulos, & Guimarães, Citation2017; Guimarães, Nunes, Barreira, & Panagopoulos, Citation2016b).

Effects of urban shrinkage

The multifaceted causes of urban shrinkage lead to a variety of implications and affect the state of the shrinking cities in many ways. Meta-analysis identifies three major topics concerning the state of shrinking cities in Europe: housing vacancy, unemployment and economic decline. As reveals, one quarter of all cases are affected by housing vacancy. Aside from the post-socialist and Western European contexts, this aspect also determines the discourse on Japanese cities. A large proportion of studies dealing with housing vacancy has been conducted for Eastern Germany. The crisis of the East German housing industry and the high vacancies, which are linked to the reunification and the transformation of the political system in Eastern Germany, formed the starting point of an increasing political and academic interest in Europe (Haase et al., Citation2017). To date, a good deal of knowledge about housing vacancy in terms of shrinkage has been accumulated. For instance, Bernt (Citation2009) deals with the role of housing companies in governance processes while Kabisch and Grossmann (Citation2013) conducted a long-term survey on demographic shifts and housing estates in Eastern Germany. Couch and Cocks (Citation2013) identify different types and causes of urban housing vacancies in Liverpool and discuss adequate policy responses. In the Japanese literature, Yamashita and Morimoto (Citation2015) propose a method to estimate temporal and spatial patterns of housing vacancy by analysing the data on property tax lists and water metre records of individual houses in a Japanese city. In addition to housing vacancy, economic decline and unemployment are the most intensely debated implications for shrinking cities in Europe. Unemployment, with its socio-economic dimension, is widely debated all over Europe, particularly for shrinking cities in Mediterranean Europe (31%). Economic decline seems to be a crucial concern for shrinking cities in Western Europe, as it is discussed by 33% of the studies dealing with Western European cities.

Table 2. Effects of urban shrinkage by region (in order of decreasing shares of cases mentioning specific effects).

Urban decay, defined as a run-down built environment, is the most striking effect discussed for Japanese cities (61%) but is only marginally mentioned in European articles. Next to social disorder and crime, the effect of urban decay is also discussed for Mediterranean cities. Furthermore, a few contributions discuss segregation processes that can emerge in the form of the spatial separation of low-income groups in neighbourhoods (Cortese et al., Citation2014). Scholars dealing with shrinking cities in Western Europe also pay some attention to the changed demand of social infrastructures due to a decreasing population (Nelle, Citation2016). The communicative dimension of urban shrinkage, referred to as stigmatization in , has received only marginal attention in the empirical debate thus far (Gribat & Huxley, Citation2015).

Responses to urban shrinkage

The reported responses are of an even greater variety and cover social, economic, environmental and planning responses. shows that housing renewal and urban regeneration are the most discussed responses in the case studies analysed, particularly in contributions about Western European (26%) and Mediterranean cities (42%). The demolition of housing is the dominant response reported for the Japanese cities (42%) but it is also a major topic for cities in Eastern Germany, which are included in the category of post-socialist Europe (17%).

Table 3. Responses on urban shrinkage by region (in order of decreasing shares of cases mentioning specific responses).

The meta-analysis further shows that economic recovery and diversification are often mentioned by the case studies. How to improve economic performance by branch diversification and how to recover the local economy are challenges which shrinking cities are dealing with all over Europe (Bernt et al., Citation2014). Another economic response is innovation and entrepreneurship, which emerges primarily in the cities of Eastern Germany. In contrast, the attraction of foreign direct investment carries more weight in the post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe – for instance, in former mining cities in Romania (Constantinescu, Citation2012). The role of culture and tourism-led regeneration policies also differs geographically: cultural projects play a role for shrinking cities in Western Europe (Cunningham-Sabot & Roth, Citation2013) but are missing in the Mediterranean and Japanese discourse. One aspect discussed for cities of Eastern Germany, Mediterranean Europe and Japan are bottom-up civil society initiatives (Guimarães et al., Citation2016b; Okabe, Citation2010; Schlappa, Citation2017). Active ageing projects have attracted the attention of some academics dealing with case studies on Europe (Cortese et al., Citation2014). Only a few papers focus on environmental improvements for shrinking cities. These responses range from re-engineering projects of the built environment (Mulligan, Citation2013) to developing green spaces in former vacant areas (Nefs, Alves, Zasada, & Haase, Citation2013). Some authors focus on educational policies addressing skill gaps or raising the general level of residents’ education in shrinking cities in Germany (Nelle, Citation2016; Plöger & Weck, Citation2014). Even though the demographic change is the dominating pressure in the Japanese discourse, social responses are somewhat limited – in contrast, physical environmental management and spatial planning strategies are frequently discussed. The papers address, for instance, land-use control that aims at concentrating urban structures and allocating areas with high vacancies for demolition, renaturation or agricultural usage by instruments such as zoning. Another planning approach mentioned is transportation system management that refers to multimodal strategies to optimize mobility (Hara & Asano, Citation2014; Morimoto, Citation2011).

This overview shows inner-European differences between Western Europe, post-socialist Europe and Mediterranean Europe and, in particular, between the EU and Japan. On the one hand, the empirical debate in Western Europe is closely associated with old industrial cities and economic decline and, on the other, with the challenges of the housing sector. In sum, a broad spectrum of responses ranging from urban and housing renewal to economic diversification and cultural regeneration or bottom-up initiatives is mentioned in the analysed studies. The cases located in post-socialist regions show a similar focus but additionally stress the accelerating factor of post-socialist transformation processes and give more attention to the demolition of housing (limited to cities in Eastern Germany) as well as economic recovery. The Mediterranean debate additionally takes up environmental disasters and climate change as drivers for depopulation that have not played a role in the European discourse thus far. Interestingly, Mediterranean studies highlight socio-economic effects and physical consequences on the urban environment, while development in the housing sector plays a minor role. The majority of the Japanese studies confirm the focus on demographic change (ageing and low birth rates) as a causal factor but shift to the built environment when discussing its effects (urban decay or housing vacancy) and responses (housing renewal and planning). In sum, it seems that regional discourses might have highlighted some aspects of the complex urban shrinkage phenomenon while neglecting others. However, it is important to note, that some studies show a more differentiated picture on shrinkage, with an integrative view that considers the different demographic, economic, social and cultural dimensions and temporal dynamics of urban shrinkage (e.g. Elzerman & Bontje, Citation2015; Pallagst et al., Citation2017; Savitch, Citation2011).

Discussion and research agenda

The meta-analysis provides a comprehensive picture of the status quo and the blind spots of empirical research, which is discussed under the terms ‘shrinking cities’ or ‘urban shrinkage’. Although the selection process and analytical framework were designed to critically reflect upon the empirical knowledge base, there are some restrictions with this method. For our analysis, we draw upon the familiar categories of causes, effects and responses, which turned out to be the ‘lowest common denominator’ of the reviewed empirical literature on shrinking cities. This classification enables consideration of a wide range of factors and the outlining of prevalent regional argumentation patterns of shrinkage. However, it also determines the structure of the possible outcomes to a certain degree. Therefore, we want to stress that some studies show a much more complex picture of shrinkage that overcomes the classification causes, effects and responses and provides a relational or alternative perspective on the phenomenon. For instance, Bartholomae, Nam, and Schoenberg (Citation2017) critically discuss the interplay of post-industrial transformation, economic decline and population loss in German cities and question the usage of population decline as a single indicator for defining urban shrinkage.

Additionally, we must admit that it was not possible to comprehensively analyse the temporal dynamics of shrinking processes, as most of the studies give only a vague impression of their temporal trajectories.

Discussion of comparative meta-analysis results

The first research question sought to clarify how shrinkage is explained theoretically in the literature dealing with EU and Japanese cities. Most of the papers start out with a short overview of the debate by highlighting population loss as the major dynamic and reflecting upon the causes and effects that are associated with the phenomenon of shrinkage in general. If at all, (macro)-theories, theoretical approaches or conceptualisations are presented in the empirical literature and vary in their depth of explanation. These theories mainly focus on the causes of shrinkage and shed only partial light on the complex phenomenon. Theories, like those of uneven development or suburbanization, have a long tradition in the shrinking debate. However, compared to the causes, effects and responses identified, they provide a narrow view of this multifaceted phenomenon. Furthermore, most of the applied theories were developed to explain processes of urban expansion. Indeed, this qualitative meta-analysis confirms the argument, that the debate seems to lack a coherent theoretical conceptualization (Haase et al., Citation2017; Sousa & Pinho, Citation2015).

However, a promising concept that takes into consideration different dimensions of urban shrinkage is that of peripheralisation (Kühn, Citation2015; Weck & Beißwenger, Citation2014). We are in line with Bernt (Citation2016), who suggested elaboration of this conceptual approach in the context of shrinkage; however, we do not want to stress its multiscalar but, rather, its multidimensional, perspective for analysing shrinking cities. While the multiscalar perspective focuses on the disadvantaged position of cities or regions as an outcome of socio-spatial inequalities on different levels, the multidimensional perspective distinguishes social, economic, political and communicative dimensions and highlights the interaction of these for explaining the downgrading of socio-spatial units. In this context, out-migration is only one contextual factor next to political dependencies, economic decoupling or stigmatization.

A comparative meta-analysis addressed the second research question in a bid to identify causes, effects and responses and to explain recurring patterns that emerge in the different regional debates. Like the theoretical perspectives, the empirical focus on the EU and Japan provides a fragmented perspective on the variety of shrinkage. Indeed, the analysis offers a plurality of causes, effects and, in particular, responses; however, most of the papers address a few recurring topics. Well-known and broadly discussed topics related to urban shrinkage dominate the empirical literature in EU regions, while others are neglected. On the contrary, the Japanese empirical literature continues its focus on natural demographic causes.

A very prominent topic that is broadly empirically discussed in both regions is housing vacancy. This could be due to the fact that this issue is not only easy to quantify for discourse and policy, but also seems to be a manageable and operational factor for policy-makers to address (Mallach et al., Citation2017). The discussion on the symptomatic effects, such as housing vacancy and the challenges of housing industries, however, might overshadow a more relational discussion of the underlying and less obvious challenges.

Besides the focus on housing, the recent perception of shrinking cities in post-socialist and Western Europe emphasizes economic challenges. As the shrinkage debate developed during the profound crisis of the industrial sector in North America and Europe in the 1970s, the identified economic focus might be related to the historical path of the debate (Fol & Cunningham-Sabot, Citation2010; Martinez-Fernandez et al., Citation2012). However, the meta-analysis also reveals that a broader notion of urban shrinkage as a societal or physical phenomenon is nascent in the literature on EU cities.

The findings of the younger empirical debate in Mediterranean Europe show different patterns. On the one hand, the studies focus on environmental pressures on the European agenda of urban shrinkage that might be a challenging factor for cities all over Europe in the near future. On the other, they primarily address socioeconomic effects (unemployment, segregation and social disorder) and the built urban environment (urban decay and urban regeneration). In this context, we want to highlight two Portuguese studies, which change the perspective on the phenomenon and undertake a survey to explore residents’ attitudes to urban shrinkage (Barreira et al., Citation2017; Guimarães, Nunes, Barreira, & Panagopoulos, Citation2016a). Looking through alternative glasses by exploring the internal perception might be a promising avenue to alter the notion of urban shrinkage.

Distinct differences mark the emergent urban shrinkage debate in Japan, which is closely intertwined with demographic change and long-term depopulation. This is not an unexpected result, as issues of low fertility and ageing have been prominently discussed in Japan in recent decades in the context of rural areas. More surprising is that the socio-demographic change that is presented as a ‘given pre-condition’ in Japan and the social and economic effects are barely discussed in the literature. Instead, the studies look at the effects and responses that address vacant properties and planning issues. This could be potentially explained by four factors. First, the debate might be influenced by national policy, which recently came up with tools to deal with and to reduce vacant properties (Hattori et al., Citation2017). Secondly, the term ‘shrinking cities’ was ‘imported’ from North America and Europe to Japan and has been mainly used in the field of city planning, which focuses on the management of shrinking cities in terms of physical aspects such as the built environment. Thirdly, the issues of demographic change, including a low birth rate, ageing and depopulation, were initially more serious in rural areas and, thus, socio-demographic implications tended to be discussed in the field of rural planning, which has been disconnected from the discourse of city planning in Japan. Fourthly, against the background of a unitary governmental system, the economic consequences of shrinkage might, instead, be addressed from a national or prefectural perspective in a local context dealing with single urban areas. However, it is difficult to provide a comprehensive explanation as to why the Japanese debate remains rather silent on social and economic challenges in shrinking cities.

In general, it appears likely that regional conditions and policy frameworks strongly affect these regional discourses (Haase et al., Citation2017). However, detailed interpretation of the regional frameworks would go beyond the purpose of this article and has been recently discussed in the literature (Haase et al., Citation2017; Mallach et al., Citation2017). In contrast, based on our meta-analysis, we want to move on to the revealed but underrepresented topics in the debate in order to identify research gaps and to provide an agenda for further empirical research.

Apart from the prevalent issues, few scholars demonstrate interest in topics, which have been rather marginalized in the international discourse so far (Großmann et al., Citation2013). Among these are environmental, social or communicative perspectives. Some studies focusing on shrinking cities in the EU, for instance, shed light on environmental planning responses or educational improvements (e.g. Mulligan, Citation2013; Plöger & Weck, Citation2014), while others refer to the problematisation of urban shrinkage in policy discourses (e.g. Gribat & Huxley, Citation2015; Zingale & Riemann, Citation2013). The variety of topics presented could provide enriching dimensions for a more integrated perspective and a better understanding of shrinkage processes as they reflect the multidimensionality of the phenomenon.

Additionally, the meta-analysis revealed the under-represented temporal dimension in the case studies. As mentioned before, it was not possible to consider temporal dynamics in the analysis, as not all of the empirical case studies indicate a time line for the processes analysed. Indeed, most of the studies mention whether cites are affected by short-term or long-term depopulation; however, a temporal classification of the various dynamics of urban shrinkage processes, based on the given studies, cannot really be carried out. For instance, urban shrinkage processes in post-socialist countries occurred more rapidly than they did in Western Europe. In these former socialist countries, deindustrialization processes were accelerated by the post-industrial transformation that, vice versa, caused out-migration and reinforced demographic change. As these underlying dynamics are difficult to grasp, the case studies tend to focus on trajectories of depopulation and to overlook the temporal complexity of urban shrinkage dimensions.

Towards a dynamic and integrative research agenda

Hereinafter, we reflect on previous conceptual key literature and on our results in order to address our fourth question. We enquire into the lessons that can be drawn from this status-quo analysis of empirical studies in Europe and Japan in order to inform further research. This study has systematically reviewed the empirically rich knowledge base offered by different disciplines and research designs. The meta-analysis shows that since the first pioneering global project Shrinking Cities in the mid-2000s (Oswalt, Citation2005, Citation2006; Oswalt & Rieniets, Citation2006), the debate has conceptually and empirically become more diverse. These additional perspectives were supported by the emergence of a growing number of inter-urban and cross-national comparative studies. In total, the debate shifted from dealing with causes and effects of shrinking, which dominated the debate in the beginning, towards studying the broad range of policy and governance responses. However, to date, there is still little empirical knowledge about the effectiveness of these responses.

Based on our findings, we argue for a more dynamic and integrative research agenda on urban shrinkage beyond regional discursive boundaries or framing. By doing so, we do not call for a holistic perspective by single studies when investigating shrinking cities, but we rather argue for a more differentiated and relational view on the phenomenon. What this claim means, what it comprises and which issues could be raised in future empirical studies are explained in what follows.

First, as already pointed out, the temporality of the different dimensions is largely absent in empirical studies thus far. The narrow focus on the temporal aspect of population trajectories hampers not only a comprehensive understanding of urban shrinkage but also the interpretation of any applied responses. As there is no strict temporal parallelism of the various processes, it might be interesting to gain a more precise understanding of how the underlying, asynchronous dynamics are interrelated and how they affect the pathways of shrinking cites.

Second, we argue for an integrative framework for investigating urban shrinkage that takes into consideration different dimensions and underlying dynamics. In line with scholars, such as Haase, Rink, and Großmann (Citation2016b) and Haase et al. (Citation2014), we see potential in the inductive theorizing of urban shrinkage based on empirical evidence. Therefore, the identified range of dimensions in the EU and Japanese studies, in particular the identified variety of governance responses, could serve as a basis for further heuristic theory building, in order to conceptually consider the effectiveness of the applied responses. Furthermore, the concept of peripheralisation (Kühn, Citation2015) seems to be a promising conceptual basis on which to take such a multidimensional and integrative perspective on the phenomenon that might support cross-national comparison.

Third, Großmann et al. (Citation2013) pointed out the potential of cross-national comparisons to uncover blind spots of national debates. By contrasting the different regional strands in the EU and Japan, our meta-analysis could discover some under-represented aspects that have often been overlooked in the respective regional debates. The Western European debate, for instance, stresses economic development and discusses a wide range of economic responses; however, it often neglects the demographic or environmental aspects of urban shrinkage. Cross-national or cross-continental studies could transfer under-represented issues to other regions and question how cities in other regional contexts cope with the thus-far-unnoticed manifestations of urban shrinkage. As a narrow perspective leads to a fragmented understanding of the phenomenon, it is important to identfy any research gaps and to reflect upon the various dimensions discussed in the different regional contexts in order to synchronise and link these debates. Furthermore, interesting insights could be gained by examining why these factors have or have not been considered in the regional strands thus far.

Fourthly, and related to the above, scholars of urban studies should employ a more relational perspective on the different dimensions of urban shrinkage. Shrinking cities have to tackle a variety of demographic, economic, social, cultural or environmental challenges that are closely intertwined and that might exacerbate or even balance each other out. A relational perspective could imply a shift from a rather one-dimensional focus – for instance, on housing challenges – to a more comprehensive perspective that sheds light on the interrelation of the different dimensions of urban shrinkage, for instance, under the more encompassing perspective of social cohesion. Moreover, as profound changes can be assumed, further research should be undertaken to explore the relationship between demographic change and the economic, social and built environment of declining cites. Hence, a relational approach could involve tackling questions that combine related aspects, such as, for instance, urban planning for an ageing and decreasing population or alternative urban economic pathways against the background of demographic change and depopulation.

Fifth, as mentioned above, there is still little international knowledge about the effectiveness of policy responses (Hospers, Citation2014). Based on the broad knowledge base about causes, effects and responses, it deserves further investigation into and evaluation of the effects that the variety of responses has on the trajectories of developments within the cities. Are the applied policy responses successful in addressing the challenges in question? Are these responses coordinated and harmonized with each other when dealing with urban shrinkage? Are there problems associated with urban shrinkage which are not sufficiently addressed by the policy agenda? Considering the raising complexity of governance and the growing field of actors involved in policy making, it would also be interesting to evaluate the way in which state and non-state actors, e.g. from civil society, influence the fruitful implementation or the failure of policy actions and measures.

Finally, scholars claimed that the national debates were conducted separately and experiences of national case studies often remained unconnected to one another. They argue for bridging and contextualizing these national debates in order to promote a fruitful knowledge exchange (Großmann et al., Citation2013; Mallach et al., Citation2017). Our meta-analysis shows that the debate became not only more geographically differentiated in the EU over the last years, but also gathered evidence that the literature is shifting from the mere accumulation of global knowledge on shrinking cities towards an intertwined analysis of different debates. However, the vast majority of the empirical studies still provide a static analysis of local structures and policies. By taking into consideration national contexts, the empirical knowledge base should also enable researchers to offer some policy recommendations and to share lessons between individual cities. Based on the suggested integrative approach, it should be more feasible to provide theoretically grounded, evidence-based and place-specific policy recommendations in order to not only reflect on but also to contribute to the ongoing policy and planning discourse.

Supp_Info_references_meta-analysis.pdf

Download PDF (137 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Robert Musil, Peter Görgl, and two anonymous referees for critical and helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alves, D., Barreira, A. P., Guimarães, M. H., & Panagopoulos, T. (2016). Historical trajectories of currently shrinking Portuguese cities: A typology of urban shrinkage. Cities, 52, 20–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.008

- Barreira, A. P., Agapito, D., Panagopoulos, T., & Guimarães, M. H. (2017). Exploring residential satisfaction in shrinking cities: A decision-tree approach. Urban Research and Practice, 10(2), 156–177. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2016.1179784

- Bartholomae, F., Nam, C. W., & Schoenberg, A. (2017). Urban shrinkage and resurgence in Germany. Urban Studies, 54(12), 2701–2718. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016657780

- Batunova, E., & Gunko, M. (2018). Urban shrinkage: An unspoken challenge of spatial planning in Russian small and medium-sized cities. European Planning Studies, 26(8), 1580–1597. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1484891

- Bernt, M. (2009). Partnerships for demolition: The governance of urban renewal in East Germany’s shrinking cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(3), 754–769. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00856.x

- Bernt, M. (2016). The limits of shrinkage: Conceptual pitfalls and alternatives in the discussion of urban population loss. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(2), 441–450. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12289

- Bernt, M., Haase, A., Großmann, K., Cocks, M., Couch, C., Cortese, C., & Krzysztofik, R. (2014). How does(n’t) urban shrinkage get onto the agenda? Experiences from Leipzig, Liverpool, Genoa and Bytom. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(5), 1749–1766. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12101

- Bontje, M. (2004). Facing the challenge of shrinking cities in East Germany: The case of Leipzig. GeoJournal, 61(1), 13–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-004-0843-7

- Camarda, D., Rotondo, F., & Selicato, F. (2015). Strategies for dealing with urban shrinkage: Issues and scenarios in Taranto. European Planning Studies, 23(1), 126–146. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.820099

- Constantinescu, I. P. (2012). Shrinking cities in Romania: Former mining cities in Valea Jiului. Built Environment, 38(2), 214–228.

- Cortese, C., Haase, A., Großmann, K., & Ticha, I. (2014). Governing social cohesion in shrinking cities: The cases of Ostrava, Genoa and Leipzig. European Planning Studies, 22(10), 2050–2066. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.817540

- Couch, C., & Cocks, M. (2013). Housing vacancy and the shrinking city: Trends and policies in the UK and the city of Liverpool. Housing Studies, 28(3), 499–519. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.760029

- Cunningham-Sabot, E., Audirac, I., Fol, S., & Martinez-Fernandez, C. (2013). Theoretical approaches of shrinking cities. In K. Pallagst, T. Wiechmann, & C. Martinez-Fernandez (Eds.), Shrinking cities. International perspectives and policy implications (pp. 14–30). London: Routledge.

- Cunningham-Sabot, E., & Roth, H. (2013). Growth paradigm against urban shrinkage: A standardized fight? The cases of Glasgow (UK) and Saint-Etienne (France). In K. Pallagst, T. Wiechmann, & C. Martinez-Fernandez (Eds.), Shrinking cities. International perspectives and policy implications (pp. 99–124). London: Routledge.

- Elzerman, K., & Bontje, M. (2015). Urban Shrinkage in Parkstad Limburg. European Planning Studies, 23(1), 87–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.820095

- Fol, S., & Cunningham-Sabot, E. (2010). “Déclin urbain” et Shrinking Cities: une évaluation critique des approches de la décroissance urbaine [Urban decline and shrinking cities: A critical assessment of approaches to urban regression]. Annales de géographie, 674(4), 359–383. doi: https://doi.org/10.3917/ag.674.0359

- Gribat, N., & Huxley, M. (2015). Problem spaces, problem subjects: Contesting policies in a shrinking city. In E. Gualini (Ed.), Planning and conflict: Critical perspectives on contentious urban developments (pp. 164–184). New York: Routledge.

- Großmann, K., Bontje, M., Haase, A., & Mykhnenko, V. (2013). Shrinking cities: Notes for the further research agenda. Cities, 35, 221–225. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.07.007

- Guimarães, M. H., Nunes, L. C., Barreira, A. P., & Panagopoulos, T. (2016a). Residents’ preferred policy actions for shrinking cities. Policy Studies, 37(3), 254–273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2016.1146245

- Guimarães, M. H., Nunes, L. C., Barreira, A. P., & Panagopoulos, T. (2016b). What makes people stay in or leave shrinking cities? An empirical study from Portugal. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1684–1708. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1177492

- Haase, A., Bernt, M., Großmann, K., Mykhnenko, V., & Rink, D. (2016a). Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(1), 86–102. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776413481985

- Haase, A., Nelle, A., & Mallach, A. (2017). Representing urban shrinkage – the importance of discourse as a frame for understanding conditions and policy. Cities, 69, 95–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.007

- Haase, A., Rink, D., & Großmann, K. (2016b). Shrinking cities in postsocialist Europe – what can we learn from their analysis for today’s theory-making? Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography, 98(4), 305–319.

- Haase, A., Rink, D., Großmann, K., Bernt, M., & Mykhnenko, V. (2014). Conceptualizing urban shrinkage. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(7), 1519–1534. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/a46269

- Hara, N., & Asano, J. (2014). A study on occurrence factors and residential environment in shrinkage of densely inhabited districts in local non area-divided cities. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 50(3), 886–891.

- Hattori, K., Kaido, K., & Matsuyuki, M. (2017). The development of urban shrinkage discourse and policy response in Japan. Cities, 69, 124–132. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.02.011

- Hoekveld, J. J. (2014). Understanding spatial differentiation in urban decline levels. European Planning Studies, 22(2), 362–382. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.744382

- Hospers, G. J. (2014). Policy responses to urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. European Planning Studies, 22(7), 1507–1523. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.793655

- Iwasaki, M., Iwamoto, Y., Matsukawa, T., Nakade, B., & Higuchi, S. (2007). Study on the reduction of non-divided zoning area. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 42(1), 136–143.

- Kabisch, S., & Grossmann, K. (2013). Challenges for large housing estates in light of population decline and ageing: Results of a long-term survey in East Germany. Habitat International, 39, 232–239. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.12.003

- Kim, C., Onishi, T., & Suga, M. (2007). Study on depopulation and transformation of urban structure - for all urban areas in Japan from 1970 to 2000. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 42(3), 835–840.

- Kotilainen, J., Eisto, I., & Vatanen, E. (2015). Uncovering mechanisms for resilience: Strategies to counter shrinkage in a peripheral city in Finland. European Planning Studies, 23(1), 53–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.820086

- Kühn, M. (2015). Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities. European Planning Studies, 23(2), 367–378. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.862518

- Mace, A., Hall, P., & Gallent, N. (2007). New East Manchester: Urban renaissance or urban opportunism? European Planning Studies, 15(1), 51–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310601016606

- Mallach, A., Haase, A., & Hattori, K. (2017). The shrinking city in comparative perspective: Contrasting dynamics and responses to urban shrinkage. Cities, 69, 102–108. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.008

- Martinez-Fernandez, C., Audirac, I., Fol, S., & Cunningham-Sabot, E. (2012). Shrinking cities: Urban challenges of globalization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36(2), 213–225. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01092.x

- Martinez-Fernandez, C., Weyman, T., Fol, S., Audirac, I., Cunningham-Sabot, E., Wiechmann, T., & Yahagi, H. (2016). Shrinking cities in Australia, Japan, Europe and the USA: From a global process to local policy responses. Progress in Planning, 105, 1–48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2014.10.001

- Morimoto, A. (2011). The effect of shrinking city on local government finance and global environment. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 46(3), 739–744.

- Mulligan, H. (2013). Environmental sustainability issues for shrinking cities: US and Europe. In K. Pallagst, T. Wiechmann, & C. Martinez-Fernandez (Eds.), Shrinking cities: International perspectives and policy implications (pp. 279–302). London: Routledge.

- Mykhnenko, V., & Turok, I. (2008). East European cities – patterns of growth and decline, 1960–2005. International Planning Studies, 13(4), 311–342. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563470802518958

- Myrdal, G. (1957). Economic theory and under-developed regions. London: G. Duckworth.

- Nefs, M., Alves, S., Zasada, I., & Haase, A. (2013). Shrinking cities as retirement cities? Opportunities for shrinking cities as green living environments for older individuals. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(6), 1455–1473. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/a45302

- Nelle, A. (2016). Tackling human capital loss in shrinking cities: Urban development and secondary school improvement in Eastern Germany. European Planning Studies, 24(5), 865–883. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1109611

- Nelle, A., Großmann, K., Haase, A., Kabisch, S., Rink, D., & Wolff, M. (2017). Urban shrinkage in Germany: An entangled web of conditions, debates and policies. Cities, 69, 116–123. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.02.006

- Ohno, H., Ukai, T., Hidaka, J., Yamazaki, Y., Otake, M., Tanaka, Y., … Oshima, K. (2006). Future image for the Tokyo metropolitan area: How is the city planning for shrinking cities. Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “Jusoken”, 33, 135–146. doi: https://doi.org/10.20803/jusokenold.33.0_135

- Okabe, A. (2010). Urbanism of shrinking society. Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “Jusoken”, 36, 5–17.

- Ortiz-Moya, F. (2015). Coping with shrinkage: Rebranding post-industrial Manchester. Sustainable Cities and Society, 15, 33–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2014.11.004

- Oswalt, P. (2005). Shrinking cities. International research. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

- Oswalt, P. (2006). Shrinking cities. Interventions. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

- Oswalt, P., & Rieniets, T. (2006). Atlas of Shrinking cities. Ostfildern: Hatje Canttz.

- Pallagst, K., Fleschurz, R., & Said, S. (2017). What drives planning in a shrinking city? Tales from two German and two American cases. Town Planning Review, 88(1), 15–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2017.3

- Pallagst, K., Wiechmann, T., & Martinez-Fernandez, C. (2013). Shrinking cities. International perspectives and policy implications. New York: Routledge.

- Plöger, J., & Weck, S. (2014). Confronting out-migration and the skills gap in declining German cities. European Planning Studies, 22(2), 437–455. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.757587

- Ragin, C. C. (1987). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Reis, J. P., Silva, E. A., & Pinho, P. (2016). Spatial metrics to study urban patterns in growing and shrinking cities. Urban Geography, 37(2), 246–271. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1096118

- Richardson, H. W., & Nam, C. W. (2014). Shrinking cities: A global perspective. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Rink, D., Haase, A., Grossmann, K., Couch, C., & Cocks, M. (2012). From long-term Shrinkage to re-growth? The urban development trajectories of Liverpool and Leipzig. Built Environment, 38(2), 162–178.

- Sato, A., & Morimoto, A. (2009). The effect of shrinking degree on reduction of administrative management and maintenance cost in compact city. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 44(3), 535–540.

- Savitch, H. V. (2011). A strategy for neighborhood decline and regrowth: Forging the French connection. Urban Affairs Review, 47(6), 800–837. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411416443

- Schlappa, H. (2017). Co-producing the cities of tomorrow: Fostering collaborative action to tackle decline in Europe’s shrinking cities. European Urban and Regional Studies, 24(2), 162–174. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776415621962

- Shetty, S. & Reid, N. (2014). Dealing with decline in old industrial cities in Europe and the United States: problems and policies. Built Environment, 40(4); 458–474.

- Shimizu, K., & Sato, T. (2011). Optimal timing of migration from depopulation Districts in urban Suburban areas. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 46(3), 667–672.

- Sousa, S., & Pinho, P. (2015). Planning for shrinkage: Paradox or paradigm. European Planning Studies, 23(1), 12–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.820082

- Tanaś, J., & Trojanek, R. (2015). Demographic structural changes in Poznań downtown: In the light of the processes taking place in the contemporary cities in the years 2008 and 2013. Journal of International Studies, 8(3), 128–140. doi: https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2015/8-3/10

- Turok, I., & Mykhnenko, V. (2007). The trajectories of European cities, 1960–2005. Cities, 24(3), 165–182. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2007.01.007

- Weck, S., & Beißwenger, S. (2014). Coping with peripheralization: Governance response in two German small cities. European Planning Studies, 22(10), 2156–2171.

- Wiechmann, T., & Bontje, M. (2015). Responding to tough times: Policy and planning strategies in shrinking cities. European Planning Studies, 23(1), 1–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.820077

- Wiechmann, T., & Pallagst, K. (2012). Urban shrinkage in Germany and the USA: A comparison of transformation patterns and local strategies. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36(2), 261–280. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01095.x

- Wirth, P., Elis, V., Müller, B., & Yamamoto, K. (2016). Peripheralisation of small towns in Germany and Japan – dealing with economic decline and population loss. Journal of Rural Studies, 47(Part A), 62–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.07.021

- Wolff, M., & Wiechmann, T. (2017). Urban growth and decline: Europe’s shrinking cities in a comparative perspective 1990–2010. European Urban and Regional Studies, 25(2), 1–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776417694680

- Yamashita, S., & Morimoto, A. (2015). Study on occurrence pattern of the vacant houses in the local hub city. Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, 50(3), 932–937.

- Zingale, N. C., & Riemann, D. (2013). Coping with shrinkage in Germany and the United States: A cross-cultural comparative approach toward sustainable cities. URBAN DESIGN International, 18(1), 90–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2012.30