ABSTRACT

Recent years have witnessed much experimentation with smart specialization strategies (RIS3) and entrepreneurial discovery processes (EDPs) in European regions. The EDP can be seen as an opportunity to address institutional questions. Because institutional patterns can explain why some policies are eventually successful while others are not, looking at the institutional context of regional economies can increase the effectiveness of regional policy. This article argues that the EDP functions as a framework to discover institutional patterns specific to a regional economy, and to define policies either consistent with existing institutions or aiming at institutional change. The article proposes a conceptual framework to understand and analyze the two institution-related roles of the EDP, first as an institutional discovery process and second as an institutional change process. The article builds on empirical case studies in two regions (Lower Austria, Austria and South Tyrol, Italy) and two small countries (Slovenia and Croatia). The case studies focus on how these regions or countries organized the EDP that eventually led to the formulation of their RIS3, and on the institutional dynamics of the EDP in discovering and changing institutions. The article concludes with policy implications that contribute to the debate on post-2020 EU Cohesion Policy.

Current EU cohesion policy is characterized by its strategic use of the smart specialization approach. Given the importance of a region’s institutional context for socio-economic processes such as innovation and entrepreneurship (Glückler & Bathelt, Citation2017), the effectiveness of regional policy hinges on its consistency with the institutional context and on its ability to facilitate the institutional changes needed. Still, the debate on how to discover regional specializations tended to focus on ‘techno-economic potentials’ (Kroll, Citation2015, p. 2080) while often ignoring complex, underlying institutional elements of the regional context (Kroll, Citation2015, pp. 2080–2081). While there is a growing consensus that the entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP) is constrained ‘by underdeveloped institutional contexts in less-developed EU regions and countries’ (Radosevic, Citation2017b, p. 347), what is called ‘institutional context’ in literature is usually limited to governance questions. The present article follows a more specific definition of institutions distinct from formal governance and including more intangible aspects of institutional context (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Glückler & Bathelt, Citation2017; Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016). I argue that looking at the institutional context of an economy with its prescriptive rules, organizations, and institutions understood as ‘stable patterns of social practice’ (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014, p. 346) as well as related processes of institutional change (Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016) is important for two reasons. First, doing so enables agents to gain a more thorough understanding of their regional economies with their capabilities, assets, and trajectories. Second, considering an economy’s institutional context enables policymakers to design institution-sensitive policies (Benner, Citation2017a), i.e. policies either consistent with existing institutions or focusing on effective institutional change. Designing institution-sensitive policies calls for tools to discover institutional patterns which are often not obvious, and to consider the opportunities and limits of institutional change. The article therefore conceptualizes the role of the EDP as an institutional discovery and change process, and presents findings from four case studies (Lower Austria, Bolzano-Alto Adige/South Tyrol, Slovenia and Croatia) on the institution-sensitivity of the EDP.

Smart specialization in Europe

Smart specialization is a major pillar of the European Union’s regional or cohesion policy and can be seen as the EU’s industrial policy (Radosevic, Citation2017a). In fact, the concept developed from one focusing on the EU’s ambition in strengthening its R&D landscape through specialization into a spatial one facilitating the diversification of regional economies into new entrepreneurial opportunities within a domain of specialized skills and knowledge (McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015). Regions are supposed to organize a participatory public-private EDP to identify regional capabilities and agree on promising fields of specialization. The EDP is meant to generate a research and innovation strategy for smart specialization (RIS3) that embodies a common vision supported by public and private agents alike, and to define actions to be implemented together (Foray, David, & Hall, Citation2009, Citation2012; Sotarauta, Citation2018, pp. 191–193).

In the EU, smart specialization strategies are an ex-ante conditionality for access to innovation-related funding by the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) (Radosevic, Citation2017a, p. 20). Smart specialization strategies shall be designed either regionally or nationally (the latter particularly in the case of smaller countries) with some form of EDP. How precisely to do so leaves ample room for experimentation among European countries and regions (e.g. Kroll, Citation2015). During this experimentation process, a number of challenges became apparent, such as the identification of the appropriate spatial level for the EDP and RIS3, continuing legacies of top-down planning, or limited capabilities for evidence-based policymaking (Capello & Kroll, Citation2016). Governance-related problems such as lacking capabilities of public-private coordination including a ‘culture of hierarchical policymaking’ (Kleibrink, Larédo, & Philipp, Citation2017, p. 6) as well as intra-governmental complexity have emerged as serious bottlenecks (Kroll, Citation2015, pp. 2082–2084) and are often but imprecisely subsumed under the header of ‘institutional’ problems. One might add to these factors low trust in government (Kleibrink et al., Citation2017, p. 11), presumably a considerable institutional problem in Southern and Eastern European countries. On the positive side, the survey undertaken by Kroll (Citation2015, pp. 2091–2094) suggests that Southern and Eastern European regions have benefitted from their EDPs not mainly because of resulting ‘discoveries’ of specializations but because of the introduction of new, bottom-up policymaking approaches. This insight is important for governance aspects of smart specialization but treats only a small part of the institutional context of a national or regional economy. Understanding how the EDP can function as a vehicle for institutional discovery and change is highly relevant and requires a clear conceptual understanding of what makes up the institutional context of an economy.

The role of institutional context in regional development

In the literature, there is a long-standing discourse on the role of institutions for national and regional economic development (e.g. Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; Amin & Thrift, Citation1994; Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Glückler & Bathelt, Citation2017; Hall & Soskice, Citation2001; Hall & Thelen, Citation2008; Lehmann & Benner, Citation2015; Putnam, Citation1995; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Rodríguez-Pose & Di Cataldi, Citation2015; Sotarauta, Citation2018; Sotarauta & Beer, Citation2017; Storper, Citation1997; Zukauskaite, Trippl, & Plechero, Citation2017). Despite the ambiguity about the role and nature of institutions, there seems to be a consensus that institutions matter for regional development because they shape the institutional context of regional (or national) economies and condition processes related to economic growth such as innovation and entrepreneurship (Glückler & Bathelt, Citation2017; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017).

However, how precisely institutions matter for regional development lacks a rigorous conceptualization and remains a subject of debate (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). Apart from fundamental problems in defining institutions and observing institutional patterns, the precise mechanisms that link institutions to economic outcomes are rarely explained. While economic geographers have for a long time felt that there is a deeply socio-institutional dimension to regional development, and while recent approaches have once again set the institutional dimension of economic development on the agenda (e.g. Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012), two essential gaps have yet to be closed. First, we need a better understanding of how institutions affect the processes of regional development. And second, rather than looking primarily at idiosyncratic cases of success and failure, we should understand how processes of policymaking have to look like to reveal, understand and consciously affect the particular institutional patterns in a given economy with the opportunities and limitations they represent.

There is considerable ambiguity about the term ‘institutions’. Often, the boundaries between formal institutions, informal institutions, and organizations are blurred (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013, pp. 1037–1038), and vague use of terms such as Storper’s (Citation1997) ‘untraded interdependencies’ and Putnam’s (Citation1995) ‘social capital’ adds to the complexity. In some instances, institutional questions are narrowed down to matters of governance such as government effectiveness and quality (e.g. Rodríguez-Pose & Di Cataldi, Citation2015) and thus to organizations and (some) formal institutions such as laws while ignoring more subtle institutional patterns of interactions between agents. In an attempt to achieve more clarity, Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014, p. 346) define institutions as ‘ongoing and relatively stable patterns of social practice based on mutual expectations that owe their existence to either purposeful constitution or unintentional emergence.’ These patterns include, for example, customs, routines, attitudes, mentalities, (dis)trust, reputation, the affinity to cooperate or compete, personal relationships, social capital (Putnam, Citation1995), or much of what is often vaguely called ‘culture’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013, p. 1038). Prescriptive rules such as explicitly codified laws and regulations as well as organizations understood as collective agents such as government agencies are distinct from institutions (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014, p. 346; Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016). There are various interactions between these three components of an economy’s institutional context. Glückler and Lenz (Citation2016) propose a taxonomy of interactions between prescriptive rules (as established by policies) and institutions. This taxonomy includes reinforcing, substituting, circumventing, and competing relationships (Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016). Benner (Citation2017a) argues that the institution-sensitivity of regional policies is important for policy effectiveness, and that institution-sensitivity requires that policies focus on the consistency between rulemaking and institutional realities. Apart from these static rule-institution relationships, an economy’s institutional context is shaped by dynamic processes of institutional change through upward and downward causation (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016). While upward causation is driven by micro-level agency (Benner, Citation2014, Citation2017b), downward causation is driven by policymaking that leads to institutional change.

Taking these thoughts on institutions and institutional change together, I propose a working definition of institutional context that will guide the remainder of this article. The institutional context of an economy is the ensemble of existing institutions as defined by Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014, p. 346), their interactions with prescriptive rules and organizations, and processes of institutional change through upward and downward causation.

While every institutional context is unique, it may be useful to consider stylized types of institutional contexts that can help us identify the mechanisms at work between institutional patterns and economic outcomes. The dichotomy between coordinated market economies and liberal market economies proposed by Hall and Soskice (Citation2001) has become widely known, but its focus on national economies makes it less useful for regional development, and the idea of non-coordinated, liberal economies appears too general to capture subtle institutional differences among regions within Continental Europe. Amin and Thrift (Citation1994), Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy (Citation2018, p. 7) and Zukauskaite et al. (Citation2017) propose the notion of institutionally or organizationally thick and thin regions but, according to the definitions of institutions and institutional context followed here treat specific parts of a region’s institutional context only. For the remainder of this article, I propose the following stylized classification of regional (or smaller national) economies building on ideas of institutional and organizational thickness (Amin & Thrift, Citation1994; Trippl et al., Citation2018, p. 7; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017):

High-coordination economies often build on a corporatist model of economic organization, are organizationally thick with strong intermediate organizations (e.g. regional development agencies, chambers of commerce) and have a rich heritage of socio-economic coordination through institutional thickness (e.g. based on mutual trust and reputation) built in long-term routines of cooperation between agents including in public-private governance processes.

Low-coordination economies are institutionally and organizationally thin, as is evident through the absence or weakness of intermediary organizations, mutual distrust between agents and notably between enterprises and government, a tradition of top-down policymaking, and a history of weak cooperation.

When it comes to smart specialization, the type of institutional context can be expected to be highly relevant. During the EDP, public-private dialogue needs to rest on institutions such as trust and credibility (European Commission, Citation2018, p. 41). For instance, institutionally-related problems such as conflicting institutional patterns, failures to mobilize stakeholder participation or shortcomings in building a common vision can hamper the process (Sotarauta, Citation2018, pp. 193–197). Capello and Kroll (Citation2016, p. 1395) cite a ‘lack of connectedness, entrepreneurial spirit, (…) quality of local governance and a critical mass of capabilities to develop collective learning processes’ as possible constraints to the implementation of the smart specialization approach. These aspects are strongly related to institutional context since lacking connectedness or weak collective learning capabilities may suggest the prevalence of institutions biased against collaboration, while entrepreneurial attitudes are often based on institutions such as risk adversity or employment preferences. Institutional problems on the regional level further include ‘mutual distrust and a weak cooperation culture’ (Trippl et al., Citation2018, p. 12). As Trippl et al. (Citation2018, p. 8) conclude, regions ‘where institutional challenges prevail, that is, where the values of innovation and collaboration are contested’ may find it more difficult to embark on the EDP and to involve a sufficient number of relevant stakeholders.

At the same time, there is a need for high context specificity when looking at the role institutions play. As Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2013) argues, there is no set of universally good or universally bad institutions but the precise role of prevalent institutional patterns for economic development depends on the spatial and temporal context. This means that while the EDP may be confronted with institutional obstacles, the context specificity it is supposed to ensure can contribute to more institution-sensitive policymaking. These relationships between institution sensitivity and the EDP are further explored in the next section.

The EDP as an institutional discovery and change process

While the term EDP figures prominently in the smart specialization literature, the EDP itself is not rigorously conceptualized. There is no theoretically sound definition of what precisely qualifies as and characterizes an EDP and what sets it apart from other policy design processes. For the sake of this article, some conceptual clarity is sought be proposing the working definition of the EDP as a systematic effort of public-private dialogue that draws on quantitative and qualitative evidence, includes the pooling of knowledge either multilaterally (e.g. in conferences or focus groups) or bilaterally (e.g. in interviews), focuses on prioritization and action planning, and is meant to codify an emerging regional consensus on cross-sectoral economic development in a RIS3.

The basic ideas behind the EDP are collective self-discovery of comparative advantages and promising opportunities for new path creation (Asheim, Grillitsch, & Trippl, Citation2017) as well as policy experimentation in an uncertain and complex environment (Foray, Citation2017; Hausmann & Rodrik, Citation2003; Radosevic, Citation2017a). These ideas do not apply only to ‘hard’ economic realities such as growth and employment which can be analyzed quantitatively, but equally to the institutional context of national or regional economies. Radosevic (Citation2017a, p. 20) traces the inherent rationale of the EDP back to the Hayekian-Polanyian idea that tacit knowledge can be identified within the cognitive framework of private agents in markets but extends it to the non-market setting of a participatory, collective prioritization and action planning process. The same idea applies to institutional context. If the EDP enables agents to make prioritization decisions on the basis of their pooled tacit knowledge about capabilities and promising techno-economic trajectories, so does it for tacit knowledge about the economy’s institutional context. Revealing and understanding the institutional context agents act within may be the primary analytical merit of the EDP, much more so than discovering concrete business opportunities which is probably best left to micro-level entrepreneurial agency (Benner, Citation2014, Citation2017b). If, as Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2013, p. 1043) argues, building economic development around the idiosyncratic institutional patterns prevalent in a given regional economy requires a process that strengthens policy embeddedness, an EDP as defined above could prove a valuable exercise in building capabilities for policy design and implementation.

By making tacit institutional knowledge explicit, the EDP can serve as a basis for tackling institutional change explicitly or implicitly, either through downward causation (i.e. through policymaking during RIS3 implementation) or through upward causation (i.e. through agents’ behaviour changing during or after the EDP). Because ‘the analysis and subsequent learning that accompany EDP can change individuals views’ (Radosevic, Citation2017a, p. 21), the fact that agents participate in an EDP can lead to institutional change through upward causation driven by agents. In this sense, the EDP can contribute not only to self-discovery in terms of ‘learning what one is good at producing’ (Hausmann & Rodrik, Citation2003, p. 605) but equally in terms of learning which institutional context one is embedded in. By making tacit knowledge about institutional context explicit, agents involved in the EDP can become capable of affecting their institutional context, either by agreeing on policies for downward causation of institutional change, or through behavioural changes leading to upward causation of institutional change. In the latter case, behavioural change can occur unconsciously.

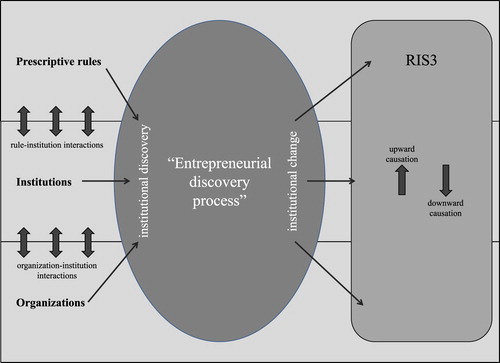

illustrates the stylized framework of the EDP as a process of institutional discovery and change. Building on the elements of institutional context proposed by Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014), the framework distinguishes between prescriptive rules, institutions and organizations. Following Glückler and Lenz (Citation2016), rule-institution interactions such as institution-reinforcing rules, institution-circumventing rules, institution-competing rules, rule-substituting or rule-circumventing institutions are represented as double-sided arrows between prescriptive rules and institutions in . The elements of the regional or national institutional context as well as their relationships with each other enter the EDP through institutional discovery. This means that the EDP should include an evidence base gathered through institutional analysis, e.g. through qualitative research. Depending on the normatively set policy goals to be achieved by the eventual RIS3, agents involved in the EDP should design policies, set priorities, and agree on actions in a way that is consistent with the institutional context as analyzed, or in a way that aims at the institutional change desired. Institutional change can happen through upward causation (e.g. through behavioural changes in the EDP or in RIS3 implementation) or through downward causation. Downward causation is driven by rules including those shaped by the policies defined in the eventual RIS3. In practice, this institutional change process can occur either explicitly and deliberately through policies aiming at downward causation through rules set by the RIS3, or unconsciously through upward causation of institutional change caused by behavioural changes. Provided that the EDP is understood as a permanent process leading to the repeated adjustment of the RIS3 through policy learning, upward institutional change can provoke changes of the RIS3 and thus on the level of rules.

In economies characterized by an absence of institutional or organizational thickness (Amin & Thrift, Citation1994; Trippl et al., Citation2018, p. 7; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017) and thus in the stylized type of low-coordination economies, upward causation of institutional change may eventually lead to institutional leapfrogging, meaning the comparatively quick establishment of institutions such as trust or routines of cooperation. While ‘regions with functioning mechanisms for policy alignment will (…) be in an advantageous situation’ (Trippl et al., Citation2018, p. 7), institutional leapfrogging implies that regions lacking these long-established mechanism still have a chance to catch up. However, institutional leapfrogging needs credibility and reinforcement to be sustained. This is why the EDP is best thought of as a permanent process requiring committed and effective implementation of the RIS3.

Institutional analysis as the evidence base of the institutional discovery process can be more effective when looking not only inside the region but also outside. Involving diaspora agents such as students, workers, scientists or entrepreneurs who left the region to study, work, or start a business elsewhere can facilitate discovering institutionally-founded constraints to path development. Diaspora agents may hold relevant explicit or tacit knowledge on how their new host regions differ from their regions of origin in terms of ‘culture’ or ‘mentality’. Through such an approach, institutionally-founded lock-in (Grabher, Citation1993) or other institutional conditions that limit path development in a region can be unveiled. This is important because institutional patterns should not necessarily be thought as beneficial to economic growth but can be damaging or constraining. Indeed, seemingly beneficial institutional patterns such as trust or tight relationships and related institutional thickness can entrench a regional economy in a lock-in situation (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013, p. 1041), calling for institutional change. Revealing these harmful institutional patterns and identifying promising avenues for institutional change require open and inclusive policy processes. As a forum to agree on policies for institutional change, the EDP provides an opportunity to do so but will need to include ‘outsiders’ such as entrepreneurial newcomers, students, or immigrant entrepreneurs, and to hedge the dangers of rent-seeking and capture by vested interests (Benner, Citation2014; McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015, pp. 1298–1299; Sotarauta, Citation2018, p. 192).

When agreeing on policies to be included in the RIS3, it makes sense for agents to use the institutional evidence base gathered through institutional discovery to consider the likelihood of policy effectiveness in terms of institutional context. Some policies (e.g. institution-competing rules) might be less promising than others (e.g. institution-reinforcing rules), and policies should be selected accordingly (Benner, Citation2017a; Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016). Insofar, the EDP functions as an institutional discovery process but not necessarily as an institutional change process. Policies are then designed in an institution-sensitive way and aim at institutional consistency. During the EDP, agents can discuss and consider in which situations to focus on institutional change and how to achieve it, and in which situations to focus on institutional consistency.

Based on the framework elaborated in the section, the following section looks at the institution-sensitivity of EDPs in four case studies.

Case studies

The present section takes a look at the institution-sensitivity of the EDP and RIS3 in two regions (Lower Austria and Bolzano-Alto Adige/South Tyrol) and two small countries (Slovenia and Croatia). These cases were selected because of the diversity they represent, enabling a comparison of different institutional prerequisites for these regions or countries to embark on the smart specialization exercise. As diversified regions in older EU member states, Lower Austria and South Tyrol are expected to have a longer experience in developing and implementing regional innovation strategies (RIS) under the framework of EU cohesion policy, and an organizational landscape arguably used to steer this process. They thus represent high-coordination economies. Slovenia and Croatia, in contrast, are transformation economies newer to the EU for whom a participatory policy approach such as smart specialization represents a break with earlier top-down policymaking traditions. Thus, the institutional context could be expected to differ markedly from the other two cases and represent the stylized types of low-coordination economies. Given the small size of Slovenia and Croatia, the different spatial scales (regional and national) of the case studies were not expected to hamper the comparability, but in organizational terms could actually provide added insights.

The case studies are based on a document analysis of RIS3 and (where available) additional literature as well as 10 semi-standardized interviews with 12 practitioners and stakeholders conducted either in person or over the phone or on Skype in August and September 2018. Interviewees were selected among facilitators of the EDP in government agencies and intermediate organizations, and selection was based in part on recommendations by interviewees. Case study research focused on the following questions:

Did the EDP function as an institutional discovery process and if so, how (institutional discovery)?

Were policies designed in a way consistent with existing institutions (institutional consistency)?

Do policies focus on achieving institutional change (downward causation)?

Did the EDP lead to institutional change through new patterns of behaviour (upward causation)?

These questions served as tools to test the hypotheses that the EDP in high-coordination economies focuses mainly on institutional consistency (H1) while in low-coordination economies the EDP focuses more on institutional change through downward causation (H2) and may eventually bring about upward causation as a by-product (H3).

Lower Austria

Lower Austria published its current economic strategy in 2014. The region’s RIS3 has to been seen within the main lines of Lower Austria’s regional policy that have evolved over time. The first major policy pillar is the setup of four science and technology parks (‘technopoles’) for fields such as medical biotechnology, agrifood, environmental technologies, medical technologies or materials. The second pillar focuses on network promotion in cluster initiatives for industries such as construction, food, plastics, or mechatronics. The strategy includes an analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) of Lower Austria’s regional economy, but this analysis does not refer to any aspects of institutional context (Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning, Citation2016, p. 43; Office of the Provincial Government, Citation2014).

Under its objective of fostering entrepreneurship, the RIS3 calls for ‘awareness raising concerning business start-up (as early as school and college)’ with the intention of ‘improving the business start-up environment in order to encourage schoolchildren and students as well to consider the idea of founding a business as an option’ (Office of the Provincial Government, Citation2014, p. 17). This policy objective implicitly aims at institutional change to strengthen entrepreneurial attitudes.

Interviewees stressed the RIS3’s character as an overarching umbrella to the region’s pre-existing programmes such as the technopoles and clusters programmes started in 2004 and 2007, respectively. By not directly defining areas of specialization, the RIS3 is designed to leave agents with a considerable degree of flexibility to react to trends by having cluster networks or technopoles cover new themes. The priorities currently pursued are the result of a long-term, incremental process of finding niches of specialization in the regional economy. Due to the long-term nature of the technopole and cluster programmes and the stable funding framework provided by the provincial government, policymakers have apparently managed to create stable expectations.

Since Lower Austria’s provincial government embarked upon participatory strategy design with the elaboration of its first regional innovation strategies in the late 1990s, the EDP was not a fundamentally new experience. While firms were invited to dialogue workshops, the EDP’s backbone was a small, closed circle consisting of the provincial government and the region’s economic development agencies managing cluster networks, technopoles, and other networking schemes. These agencies conducted needs assessments and interviews among their client companies. Interim results were repeatedly coordinated with membership organizations such as the chamber of economy and the regional business association. Agencies could rely on their long-standing experience in liaising with companies through cluster and technopole managers and on trust built over time. Companies were motivated to participate in the EDP because they were convinced that their input would be taken seriously.

Interviewees emphasized that while agents do seek to learn from good practices from other regions, practices are adapted to the region’s (institutional) context through a process of discussion. Intermediary organizations such as the chamber of economy play a translating role here. Since the chamber maintains a network of local offices staffed with advisors, chamber employees are in close contact with companies and can be expected to know the local economic context well. Similarly, cluster or technopole managers are in close touch with their member or client companies and are embedded in the local institutional context.

RIS3 implementation is steered through a permanent coordination process between the provincial government and intermediary organizations. If and when major deviations from pre-defined objectives become apparent, development agencies are requested to conduct surveys among their client companies, again building on the trust built in long-standing cooperation in clusters, technopoles or similar schemes. Company involvement in RIS3 implementation is thus indirect. This coordination process underscores the corporatist nature of policymaking in Lower Austria. The coordination process between the provincial government and intermediate organizations is understood both as a bottom-up mechanism to align policy with firms’ needs, and as a top-down process of enhancing the outreach of policy priorities (e.g. digitalization) among firms. Indirect coordination between the provincial government and companies through intermediary organizations is facilitated by long-standing cooperation between these intermediaries and companies and the trust built there, e.g. in cluster and technopole schemes or, in the case of the chamber, local branch offices and sectoral associations. For instance, joint initiatives between the provincial government and the chamber of economy to support the innovative upgrading of companies started in 1979 and include local counselling for individual companies.

Bolzano-Alto Adige (South Tyrol)

The Italian province of Bolzano-Alto Adige (South Tyrol) published its RIS3 in 2014, a process that was preceded by various other policy initiatives, strategies and studies such as a 2012 study on the setup of a technology park elaborated by the Free University of Bolzano. With its German-speaking majority and its location at a European north–south transportation axis, the province’s RIS3 defines as its mission to position the regional economy as a hub between Italian, Austrian and German markets. As a continuation or previous studies and strategies, the RIS3 lists the following areas of specialization: energy and environment, alpine technologies, food technologies, information and communication technologies and automation, creative industries, and natural spa treatments and medical technologies (Autonomous Province of Bolzano-Alto Adige, Citation2014).

Referring to aspects of institutional context, the RIS3 notes the difficult relationship between business and academia, the province’s bi-cultural heritage, and a certain degree of hesitation by regional agents to seize related opportunities. Further, the strategy seeks to increase firms’ absorptive capacity. As an overarching institutional objective, the RIS3 calls for an improvement of the regional innovation ‘culture’ (Autonomous Province of Bolzano-Alto Adige, Citation2014, pp. 8, 16–18).

The RIS3 includes a SWOT analysis of the province’s regional economy. The analysis refers mainly to ‘hard’ economic and does not include aspects of institutional context. The only aspect vaguely related to institutions is the bilingual capacity of the province’s population classified as an opportunity (Autonomous Province of Bolzano-Alto Adige, Citation2014, pp. 18–20).

South Tyrol’s EDP included focus group discussions among associations, enterprises and R&D entities, workshops, and a survey among enterprises. The RIS3 mentions that the EDP precedes the smart specialization approach. For instance, a participatory prioritization process in the energy and environmental sector dates from 2002 while in other sectors, participatory strategy design processes are younger but still precede the smart specialization era. The RIS3 does not explicitly aim at institutional change but does define actions to promote cooperation between agents and notably between firms. RIS3 implementation was foreseen as a participatory process continuing the EDP (Autonomous Province of Bolzano-Alto Adige, Citation2014, pp. 20–28, 56–58, 67–69).

During the interviews, some nuances emerged. Despite prior experience with participatory strategy design, the EDP was considered a new approach that came at a formative time when the present innovation system of the province was still emerging. During the EDP, in-depth face-to-face interviews with companies were carried out and arguably established a trustful atmosphere for companies to share information. Private-sector involvement in RIS3 implementation is limited to annual meetings of the innovation board and thus less extensive than foreseen in the RIS3. Nevertheless, the EDP is seen to have changed the dynamics of cooperation in the regional economy. Collaboration between the university and firms is believed to have considerably improved, with firms now actively approaching the university for collaborative R&D and joint ESIF-supported projects. However, due to the province’s rather small economy, cooperation among agents was not scarce even before the EDP. Many agents knew each other, implying a considerable stock of social capital. The EDP benefited from cluster and networking support schemes of economic development agencies because agencies’ staff knew major companies and enjoyed their trust and a good reputation. The EDP made explicit an established consensus on the trajectory of regional development to be pursued: a trajectory focused on supporting export-oriented SMEs in existing areas of specialization. The formulation of this vision made implicit, tacit institutional knowledge on agents’ shared vision of economic development explicit. Entrepreneurship was not a major pillar of this consensus because a lack of entrepreneurial ‘culture’ was perceived to be a characteristic of the regional economy. Still, the need to strengthen the regional innovation system was a shared goal that included eventually improving the framework conditions for entrepreneurship. The major vehicle to do so was the setup of the ‘NOI’ technology park, an idea that precedes the EDP. Thus, South Tyrol’s EDP exhibited a strong degree of path dependency and followed the trajectories established by previous collaborative schemes without radical institutional change. Even so, the shared vision embodied in the RIS3 is seen to have reinforced agents’ and companies’ awareness on the need to cooperate, including in university-industry collaboration.

Slovenia

Slovenia’s RIS3 defines priority areas including smart cities and smart buildings, sustainable tourism and food production, health/medicine, mobility, and materials (Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy, Citation2015). While the analytical part of the Slovenian RIS3 includes a SWOT analysis of the national innovation system, aspects of institutional context are virtually absent. The only point mentioned that somewhat relates to institutional context is weak cooperation between agents in the innovation system (Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy, Citation2015, pp. 6–7).

Compared to Baltic countries, Karo, Kattel, and Cepilovs (Citation2017, pp. 283–284) state a fairly extensive consultation of business representatives such as the Chamber of Commerce and Industry during the Slovenian EDP. The subsequent elaboration of action plans by ‘strategic partnerships’ including public and private agents and co-funded by them is seen as a continuation of the EDP. In sum, 1,500 participants were involved in the process (Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy, Citation2015, pp. 10–12, 44–46).

The Slovenian RIS3 does not explicitly focus on aspects of institutional change but lists cooperation between agents and entrepreneurship as themes to be supported. However, institutionally founded preconditions for cooperation such as trust or risk tolerance are not explicitly addressed (Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy, Citation2015).

The interviews revealed that due to the small size of the economy, agents often knew each other before and cooperation did occur to some degree. Still, the EDP introduced a new approach in two ways. First, it represented a new approach to policymaking because it gave firms a voice in strategy design. Second, it was a forum for building trust among firms. The EDP primarily focused on SMEs which were reluctant initially because they feared marginalization by larger firms. After the economic crisis Slovenia previously had suffered from, firms were looking for the government to provide policy guidance and were willing to cooperate with the government and amongst each other to develop a new growth model. Additionally, since Slovenia’s first draft RIS3 was rejected by the European Commission, agents feared that ESIF funding might be lost because of conditionality. These perceptions arguably facilitated the EDP.

The government’s coordination team learned about aspects of institutional context during the process. For example, they were surprised by the high willingness of companies to cooperate with government. After screening quantitative data such as the incidence of university-industry collaboration, the team visited agents to find out more about the nature and problems of cooperation. It is likely that these qualitative interviews gave coordinators a deeper implicit understanding of parts of the economy’s institutional context.

Key people organizing the EDP managed to convince firms to share their visions and strategies because of the prospect of collaborative projects being supported through cohesion policy funds, and because these key people were seen as independent and trustworthy. Trust built in these interactions enabled firms to contribute confidential information to the EDP. In open call for ideas, the government offered businesses the possibility to mark information as confidential. As confidential information did not leak, companies’ trust in the process was reinforced. Business support organizations such as the Ljubljana Technology Park acted as mediators and contributed to trust-building. While firms sent representatives from technical levels instead of top management, the EDP gave these technical and lower management staff an opportunity to widen their scope of cooperation by getting in touch and cooperating with agents they had not known before, including SMEs and entrepreneurs. In this sense, interviewees saw the EDP as having led to the emergence of new routines. The strategic platforms coordinating RIS3 implementation and the continued practice of the coordinators on the governmental side to talk to companies in a permanent dialogue process may confirm these new routines of cooperation and trust-based relationships.

Croatia

Croatia published its national RIS3 in 2016. The EDP that led to Croatia’s RIS3 involved a series of regional and thematic stakeholder workshops as well as expert working groups. The resulting priority areas include pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, health services, nutrition, energy technologies, environmentally friendly technologies or materials, vehicle manufacturing, transport, logistics, cyber security, dual-use technologies, demining, production/processing, and wood as well as key enabling technologies and information and communication technologies as cross-cutting priority subjects (Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds, Citation2016).

The Croatian RIS3 mentions that it ‘should be based on available resources and attitudes’ (Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds, Citation2016, p. 13, emphasis added), a hint to the relevance of institutional context. In more detail, the strategy repeatedly refers to the need for establishing an innovation, investment, business, entrepreneurial, or university-industry collaboration culture (Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds, Citation2016, p. 15, 82, 151, 169, 170, 181, 190). This sensitivity to ‘culture’ is consistent with the Croatian strategy’s SWOT analysis listing a ‘limited patenting and commercialisation culture’ as well as further institution-related factors such as weak university-industry collaboration and a mismatch between research and economic demand as weaknesses (Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds, Citation2016, pp. 77–78). Interviewees confirmed weak university-industry cooperation is a problem, although one not unique to Croatia.

During the EDP, organizations such as the national innovation agency BICRO as well as cluster organizations were involved in strategy design, either by providing data or through interviews. Company representation was indirect through cluster organizations. To a considerable degree, evidence used in the process was collected by external experts. This strong reliance on external expertise may have been a weakness of the approach pursued. The Croatian Chamber of Economy played a mediating role between government and companies. The chamber’s local offices contacted member companies and convinced them to participate in EDP activities such as public consultation meetings. The chamber’s efforts may have been important to convince company managers that the RIS3 would be different from previous government strategies with limited impact because of the ESIF conditionality. It thus seems as if on an institutional level, the chamber’s relational assets and the reputational effects of EU policy (in the form of the ex-ante conditionality) helped in overcoming firms’ reluctance towards getting involved in participatory strategy design. Still, it seems as if the tight time frame of the EDP gave some agents a feeling of not being able to express their opinions sufficiently. Apparently the EDP was a challenging stage for agents, which is not surprising given that this comprehensive exercise of gathering evidence and aligning policy priorities was an approach new to Croatia’s innovation policy.

Interviewees confirmed the lack of cooperation among agents in the innovation system and notably between companies and academia. Some behavioural changes can be seen after the EDP. For instance, firms seem to be more confident in their ability to voice their policy concerns, e.g. by being more active in commenting policy decisions through social media. Parts of the academic landscape seem to have become more open towards university-industry collaboration. Within the government, new routines of cooperation between ministries and with agents outside the government have been anchored. More generally, the EDP has created a sense of stability because previously, Croatian innovation policy was unstable and subject to frequent changes. The EDP, the existence of the RIS3 and its status as fulfilling an ESIF conditionality may have contributed to more stable expectations among companies towards the innovation policy landscape.

Conclusions from the case studies

The case studies led to some insights relevant for the research questions pursued:

Did the EDP function as an institutional discovery process and if so, how?

While explicit institutional analysis was not part of the EDP in any region or country studied, analytical tools such as focus groups and interviews may have generated (tacit) knowledge on institutional knowledge, although this knowledge is not clearly reflected in the RIS3 or their SWOT analyses. The strategy that comes closest to including at least an implicit institutional analysis is the Croatian one which often refers to the need for ‘cultural’ change in the economy. However, the vague notion of ‘culture’ is not explained in further detail, thus probably more obscuring than elucidating aspects of institutional context in need for institutional change.

In Slovenia, stakeholder interviews arranged after screening the outcomes of the quantitative analysis may have contributed to coordinators’ understanding of the institutional context, as have their experiences made throughout the EDP. In this way, companies’ expectations and attitudes towards cooperation became apparent. Thus, though there was no formal and explicit institutional analysis involved, the EDP did actually function as an institutional discovery process on some aspects of institutional context.

The experience of South Tyrol’s EDP confirms the importance of in-depth company interviews. In both South Tyrol and Lower Austria, the EDP benefitted from a long-standing legacy of public-private cooperation under previous strategies and notably in clusters, technopoles, and similar networking schemes. Even without an explicit institutional analysis performed, it is likely that a large amount of tacit institutional knowledge was available to policymakers during the EDP.

Diasporas were not used as sources of institutional knowledge in either case.

Were policies designed in a way consistent with existing institutions (institutional consistency)?

Consistent with the lack of explicit institutional analysis, the RIS3 analyzed do not explicitly address institutional consistency. However, RIS3 can still be implicitly institutionally consistent. Tacit knowledge gained during focus group discussions or interviews can indeed ensure a considerable degree of institutional consistency of the resulting RIS3. In South Tyrol, the depth of implicit institutional knowledge available in the EDP may well have facilitated agreeing on the common vision embodied in the RIS3 which reinforced routines of cooperation even without radical institutional change. Similarly, the fact that Lower Austria’s current RIS3 builds on previous strategies and long-standing networking schemes that have generated routines of cooperation between companies and economic development agencies has arguably contributed to the emergence of trust and social capital that the RIS3 presupposes. The trust and context knowledge enjoyed by intermediary organizations ensure institutional consistency. Since company involvement in Lower Austrian strategy design and implementation is to a large degree indirect and builds on close relationships between economic development agencies with their client companies, Lower Austria’s approach follows a corporatist model that presupposes a high degree of institutional consistency.

Do policies focus on achieving institutional change (downward causation)?

Probably owing to the lack of explicit institutional analysis, policies aiming at downward causation of institutional change are rarely found in the RIS3 analyzed. Still, Lower Austria’s RIS3 includes at least an implicit policy for downward causation of institutional change through its call to strengthen entrepreneurial attitudes through education. While not anchored in the RIS3, some approaches used by intermediary organizations in Lower Austria such as publishing success stories to increase peer pressure among competing companies can be seen as implicit policies of downward causation of institutional change and, through the corporatist coordination mechanism between the provincial government and intermediary organizations, are part of RIS3 implementation.

While the Croatian RIS3 addresses institutional aspects such as a weak ‘culture’ of university-industry cooperation, the vagueness of the analysis in institutional terms means there is no clear link between institutional realities and policies. Explicit policy interventions aiming at downward causation of institutional change are therefore not observable.

Taken together, the case studies suggest that the opportunities of the EDP in formulating policies for downward causation of institutional change are rarely seized.

Did the EDP lead to institutional change through new patterns of behaviour (upward causation)?

Several interviewees mentioned that the EDP was more important than its formal outcome (RIS3) because the EDP led to behavioural change in agents’ attitudes towards cooperation and to trust-building among each other. This finding relates to processes of institutional change such as a higher willingness towards university-industry collaboration found by Trippl et al. (Citation2018, p. 14) in weaker European regions.

The Slovenian experience offers an example of how the EDP can be made a permanent process through public-private action planning and project implementation. Such an approach can help anchoring a participatory and cooperative policymaking style and thus eventually lead to new behavioural patterns and durable institutional change.

The Croatian case is interesting because the brokering role of the chamber of economy in convincing companies to participate in the EDP, the credibility lent to the EDP through the ESIF conditionality, and the experience of the EDP itself seem to have altered private-sector agents’ behaviour, thus bringing about some degree of upward causation. The willingness of companies to engage more confidently in participatory public-private policymaking is an example for this kind of institutional change, although its durability and strength cannot be judged yet.

When comparing the four cases, it seems as if the EDPs organized in Lower Austria and South Tyrol were largely consistent with existing institutional realities in the regional economies and generally led to the definition of institution-reinforcing rules through the policies and actions anchored in the RIS3. For example, the fact that South Tyrol’s RIS3 explicitly codified a formerly tacit consensus about the pathway of regional development to be followed by public and private agents is a clear example for an institution-reinforcing rule. The other two cases, Slovenia and Croatia, can serve as examples for the upward causation of institutional change through the EDP. In these cases, the ESIF conditionality can be seen as an institution-circumventing rule because it motivated public and private agents to work together, thus breaking established routines of isolated policymaking by government and limited cooperation between private and public agents as well as between companies and academia. By implementing this institution-circumventing rule set by EU policy, agents changed their behaviour during and after the EDP and thus embarked on a process of upward causation of institutional change. In a stylized way, the case studies can be classified in terms on institution-sensitivity as shown in .

Table 1. Institution-sensitivity in the case studies.

As for the hypotheses formulated, the case studies yield a complex picture. The focus on institutional consistency in high-coordination economies such as Lower Austria and South Tyrol (H1) is supported by the case studies. However, among the four economies studied, only Lower Austria showed some efforts at downward causation, thus refuting H2. The lack of explicit institutional analysis arguably explains the missing focus on upward downward causation in low-coordination economies. While in low-coordination economies downward causation may be most needed, institutional change in Slovenia and Croatia was induced during the EDP through upward causation, thus confirming H3. These results reflect the limitations to the EDP posed by the organizational thinness found in low-coordination economies (Trippl et al., Citation2018, pp. 7–8). However, the Slovenian and Croatian cases show that particular conditions such as a sense of urgency, combined with key people’s or intermediary organizations’ efforts to convince companies and to build trust can help overcome institutional obstacles to the smart specialization approach. While the Croatian case is probably the one most fraught with challenges and thus more characteristic of a low-coordination economy than Slovenia, the case study shows that even under difficult circumstances, the EDP may be useful in changing behaviour or routines. Insofar, institutional leapfrogging may be achieved even under difficult conditions, at least through upward causation. Yet, much will depend on maintaining the trust built, ensuring the credibility of the process, and learning from the problems encountered to render the (limited) institutional leapfrogging achieved sustainable.

Policy implications

The case studies demonstrated the possibilities and limits of institutional policymaking during the EDP. One of the cross-cutting insights is that RIS3 typically focus on ‘hard’ data as evidence base for EDPs and strategy implementation. There seems to be a lack of institutional analysis which limits the EDP’s important function as an institutional discovery process and its opportunities to include policies aiming at downward causation in RIS3. Even so, qualitative methods such as focus groups or interviews or evolutionarily building on long-standing cooperative schemes can generate tacit institutional knowledge. Translating this knowledge into action by addressing institutional context in RIS3 could be a critical step in reinforcing the effectiveness of RIS3 and their implementation. Explicit institutional analysis can reduce the risk that opportunities for institution-sensitive policymaking be wasted.Footnote1

The necessity of the EDP and RIS3 to fulfil the ESIF ex-ante conditionality to prevent the loss of ESIF funding is an important lever in establishing new institutional routines, notably for convincing private-sector companies to participate in collaborative strategy design. The role of EU policies thus acting as institution-circumventing rules may be particularly relevant in economies with higher levels of distrust between firms and government, i.e. low-coordination economies.

The role of intermediary agents such as technology parks or chambers of commerce acting as relational brokers can be important in overcoming institutional legacies of weak public-private cooperation. Building social capital through intermediary organizations is likely to be a prerequisite for institution-sensitive participatory policymaking. Fulfilling this role requires high degrees of effectiveness and reputation of these intermediary agents and calls for strengthening these organizations’ capacities in the first place.

Regions or countries that do not enjoy the thick social capital built by strong intermediate organizations over a long time and primarily low-coordination economies will probably have to leap-frog by using the EDP to build social capital. Slovenia provides an indication that institutional leapfrogging could eventually work. The possibility of institutional leapfrogging provides an answer to the paradox of smart specialization, following the debate on the ‘regional innovation paradox’ (Oughton, Landabaso, & Morgan, Citation2002). The two high-coordination economies that seem to have found the roll-out of the smart specialization approach fairly easy (Lower Austria and South Tyrol) are the ones that probably did not have an urgent need for the approach because of their tradition of participatory strategic policymaking and their institutional and organizational thickness (Amin & Thrift, Citation1994; Trippl et al., Citation2018, p. 7; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017). The two other, low-coordination economies that did not have comparable institutional preconditions had a much more urgent need for smart specialization but found it much harder to implement. Still, the pressure and credibility lent to the process by the ESIF conditionality left agents with no choice but to embark on the process. Pressure and credibility created an opportunity for institutional leapfrogging through upward causation of institutional change by building trust among agents and anchoring new routines of cooperation.

Given the problems in identifying context-specific specializations that have surfaced during the beginning of implementation of the smart specialization approach (Kroll, Citation2015, pp. 2082–2083), we may conclude that the EDP is beneficial for regional economies not because of its result but because of its institutional by-products. These institutional by-products are similar to the positive governance-related by-products of the EDP found by Kroll (Citation2015, p. 2095) and Trippl et al. (Citation2018, p. 17). While Kroll (Citation2015, p. 2095) hypothesized that governance-related by-products may be more important than RIS3 implementation, an equivalent argument applies to the wider institutional context. Institutional by-products of an EDP include not only new public-private governance approaches but also agents’ deepened understanding of an economy’s institutional context, higher institution-sensitivity of regional policies, and behavioural changes. This insight confirms the claim that ‘getting the process itself right is at least as important as the final outcome of the strategy process’ (Kleibrink et al., Citation2017, p. vi).

Still, the outcome of policies defined in RIS3 is not unimportant either. When it comes to policies implemented under RIS3, the typology of high-coordination and low-coordination economies can serve to discuss possible configurations. Analyzing the policies actually pursued, primarily in low-coordination economies, and their success of failure will be highly interesting in a few years from now. At present, we can conclude that the procedural by-products of the smart specialization approach are important for low-coordination economies, but their actual policy impact cannot yet be judged. For the time being, it seems fair to state that the true value of smart specialization may lie in its potential to provide a process of institutional discovery and change.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to Alexander Degelsegger-Márquez, Carlo Gianelle, Johannes Glückler, Aleš Gnamuš, Åge Mariussen, Michaela Trippl and several anonymous reviewers for valuable discussions or comments. Of course, all remaining errors and omissions are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Maximilian Benner http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1386-808X

Notes

1. Precisely how to perform institutional analysis is a complicated matter that merits further research. While explorative stakeholder interviews and focus groups are the methods of choice, much depends on how to frame them to institutional questions. In doing so, regional scientists could learn from cultural anthropology in applying methods such as participant observation that can reveal institutional patterns unconsciously followed by stakeholders.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York, NY: Crown Business.

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. J. (1994). Living in the global. In A. Amin & N. J. Thrift (Eds.), Globalization, institutions, and regional development in Europe (pp. 1–22). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Asheim, B., Grillitsch, M., & Trippl, M. (2017). Smart specialization as an innovation-driven strategy for economic diversification: Examples from Scandinavian regions. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, R. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 74–99). London: Elsevier.

- Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning. (2016). Policy framework for smart specialisation in Austria.

- Autonomous Province of Bolzano-Alto Adige. (2014). Smart Specialisation Strategy für die Autonome Provinz Bozen-Südtirol.

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2014). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38, 340–363. doi: 10.1177/0309132513507823

- Benner, M. (2014). From smart specialisation to smart experimentation: Building a new theoretical framework for regional policy of the European Union. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 58, 33–49. doi: 10.1515/zfw.2014.0003

- Benner, M. (2017a). From clusters to smart specialization: Tourism in institution-sensitive regional development policies. Economies, 5, 26. doi: 10.3390/economies5030026

- Benner, M. (2017b). Smart specialisation and cluster emergence: Building blocks for evolutionary regional policies. In R. Hassink & D. Fornahl (Eds.), The life cycle of clusters: A policy perspective (pp. 151–172). Camberley: Edward Elgar.

- Capello, R., & Kroll, H. (2016). From theory to practice in smart specialization strategy: Emerging limits and possible future trajectories. European Planning Studies, 24, 1393–1406. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1156058

- European Commission. (2018). Supporting an innovation agenda for the Western Balkans. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Foray, D. (2017). The economic fundamentals of smart specialization strategies. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, R. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 38–52). London: Elsevier.

- Foray, D., David, P., & Hall, B. (2009). Smart specialization—The concept. Knowledge Economists Policy Brief No. 9.

- Foray, D., Goddard, J., Goenaga Beldarrain, X., Landabaso, M., McCann, P., Morgan, K., … Ortega-Argilés, R. (2012). Guide to research and innovation strategies for smart specialisation (RIS 3). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Glückler, J., & Bathelt, H. (2017). Institutional context and innovation. In H. Bathelt, P. Cohendet, S. Henn, & L. Simon (Eds.), The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation (pp. 121–137). Cheltenham, Northampton: Elgar.

- Glückler, J., & Lenz, R. (2016). How institutions moderate the effectiveness of regional policy: A framework and research agenda. Investigaciones Regionales – Journal of Regional Research, 36, 255–277.

- Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy. (2015). Slovenia’s smart specialisation strategy: S4.

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties: The lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm: On the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). London, New York: Routledge.

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). An introduction to varieties of capitalism. In D. A. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 1–68). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P. A., & Thelen, K. (2008). Institutional change in varieties of capitalism. Socio-Economic Review, 7, 7–34. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwn020

- Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development as self-discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72, 603–633. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00124-X

- Karo, E., Kattel, R., & Cepilovs, A. (2017). Can smart specialization and entrepreneurial discovery be organized by the government? Lessons from Central and Eastern Europe. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, R. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 270–293). London: Elsevier.

- Kleibrink, A., Larédo, P., & Philipp, S. (2017). Promoting innovation in transition countries: A trajectory for smart specialisation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Kroll, H. (2015). Efforts to implement smart specialization in practice—Leading unlike horses to the water. European Planning Studies, 23, 2079–2098. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2014.1003036

- Lehmann, T., & Benner, M. (2015). Cluster policy in the light of institutional context—A comparative study of transition countries. Administrative Sciences, 5, 188–212. doi: 10.3390/admsci5040188

- McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European Union cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49, 1291–1302. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds. (2016). Croatian smart specialisation strategy 2016–2020.

- Office of the Provincial Government. (2014). Economic strategy lower Austria 2020.

- Oughton, C., Landabaso, M., & Morgan, K. (2002). The regional innovation paradox: Innovation policy and industrial policy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 27, 97–110. doi: 10.1023/A:1013104805703

- Putnam, R. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6, 65–78. doi: 10.1353/jod.1995.0002

- Radosevic, S. (2017a). Assessing EU smart specialization policy in a comparative perspective. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, R. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 2–37). London: Elsevier.

- Radosevic, S. (2017b). Advancing theory and practice of smart specialization: Key messages. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, R. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 346–356). London: Elsevier.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47, 1034–1047. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Di Cataldi, M. (2015). Quality of government and innovative performance in the regions of Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 15, 673–706. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu023

- Sotarauta, M. (2018). Smart specialization and place leadership: Dreaming about shared visions, falling into policy traps? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5, 190–203. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2018.1480902

- Sotarauta, M., & Beer, A. (2017). Governance, agency and place leadership: Lessons from a cross-national analysis. Regional Studies, 51, 210–223. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1119265

- Storper, M. (1997). The regional world: Territorial development in a global economy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Trippl, M., Zukauskaite, E., & Healy, A. (2018). Shaping smart specialisation: the role of place-specific factors in advanced, intermediate and less-developed European regions. Papers in Economic Geography and Innovation Studies, 2018/01.

- Zukauskaite, E., Trippl, M., & Plechero, M. (2017). Institutional thickness revisited. Economic Geography, 93, 325–345. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2017.1331703