ABSTRACT

The Barca Report of 2009 firmly placed endogenous potentials on the European Union policy agenda. Now, as the current EU programming period 2014–2020 draws to a close, this article examines how such potentials are being shaped and applied at the local and regional levels. We reflect upon lessons learned from this approach, thereby contributing to the debate on the next European Union’s cohesion programming period from 2020 onwards. The analysis deals with the valorization of place-based development potentials in case study regions, highlighting challenges in the current development of such regions. Examples are given of the utilization of endogenous potentials, and we consider lessons learned from this locally-led, place-based development approach for the wider framework of European cohesion policy. The focus is on (old) industrial regions, characterized by small- and medium-sized towns outside major agglomerations. The authors conclude that it is insufficient to merely consider the direct economic effects of endogenous development potentials. Instead, a more comprehensive perspective is required, one that pays greater attention to other functions of endogenous approaches, specifically their catalyst, identity and symbolic functions.

1. Introduction

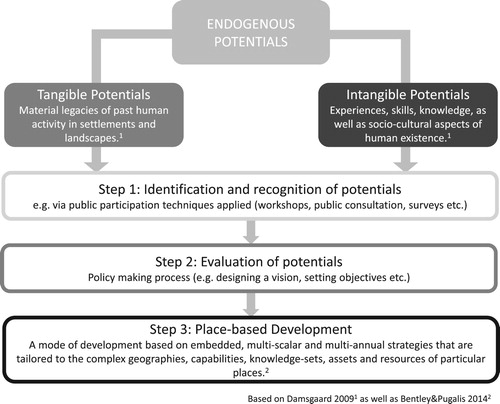

The Barca Report to the European Union (Barca, Citation2009) firmly placed the utilization of endogenous potentials on the EU agenda. Implemented through various policies related to territorial development (e.g. the EU’s Territorial Agenda), this utilization still serves as the underlying logic of the current cohesion policy (Mendez, Citation2013). Endogenous territorial potentials can be divided into tangible assets, such as natural and human resources, and intangible assets, such as organization, culture, social issues and governance (Damsgaard, Lindquvist, Roto, & Sterling, Citation2009). Against the backdrop of the ongoing financial and economic crisis, which began in 2008, a strong dependency on foreign direct investments has proven a risky development strategy for many regions. Therefore, it is unsurprising that many actors involved in regional development have shown a growing interest in reviewing their territorial potentials.

The article focuses on the situation of non-agglomeration, (old) industrial regions in Europe, often situated in the periphery outside the main political and academic hubs. Towns and regions of this type are often characterized as ‘lagging behind’ larger metropolitan regions that have managed to transform towards knowledge-based services, smart governance of resources and updated industries. Many such ‘lagging’ regions are undergoing a process of decline and shrinkage (ESPON, Citation2006), specifically suffering from demographic changes such as outmigration, the loss of younger residents, social erosion, a lack of skilled workforce, as well as economic decline in terms of job losses and industrial restructuring. In consequence, many afflicted areas have become ‘chronic patients of regional policy, constantly in need of care but not getting well’ (Wirth et al., Citation2016, p. 63), a problem which in recent years has created new political challenges (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). Such structural weaknesses tend to persist in a negative regional cumulative causation cycle (Myrdal, Citation1957) due to a lack of economic innovation and growth impulses (Morgan, Citation2013).

Accordingly, the paper investigates the role played by endogenous development potentials in underperforming regions, as such potentials are at the core of the current European Union’s cohesion policy 2014–2020 (e.g. Harfst, Wirth, & Simić, Citation2019; Marques & Morgan, Citation2018). The article discusses the following questions: (1) Which mechanisms underlay the use of endogenous potentials towards a place-based development approach; (2) Which valorizations can be particularly observed in (old) industrial regions characterized by small- and medium-sized towns; and (3) Is there evidence that the European Union’s regional policy (positively) influences the valorization of endogenous potentials at local/regional level?

In the following section, we give an overview of academic research on endogenous potentials, analyzing these with special reference to small and medium-sized towns. Building on these findings, we then address the valorization of such potentials in two case studies, highlighting current regional challenges and providing examples of the identification and utilization of endogenous potentials (Section 3). Subsequently, examples are discussed with regard to the valorization of endogenous potentials, applied policy instruments and outcomes. In our conclusion, we reflect on the current significance of endogenous potentials in regional development and provide some recommendations for the European Union’s upcoming programming period for 2020 + .

2. Endogenous potentials and the development of small- and medium-sized towns

Before using the rather fuzzy expression ‘endogenous potential’ in the context of regional development, it is useful to briefly consider previous definitions and applications of the term. In this section we thus briefly discuss academic concepts linked to endogenous potentials before analyzing their role in European cohesion policy. In addition, we then discuss the state of development in our focus regions, namely small and medium-sized towns.

2.1. Endogenous potentials revisited

Two broad perspectives on endogenous potentials can be identified within academic discourse (Martin & Sunley, Citation1998; Stough, Stimson, & Nijkamp, Citation2011). The first appears in the field of economic geography, where endogenous potentials are applied to the analysis of unbalanced growth and development patterns at different spatial levels (Dunford & Smith, Citation2000; Petrakos, Rodríguez-Pose, & Rovolis, Citation2005). The second perspective appears in the field of applied regional sciences and regional development, which forms the background to this article. In this understanding, endogenous potentials such as institutions, capacities of actors, cultures and economic links within the regional or local context explain the specifics of diverging regional development and growth patterns. This understanding can be said to represent the broader shift in regional development theories towards more place-centred strategies in the context of the long-evolving debate on a ‘new regionalism’ paradigm in economic geography (cf. Bentley & Pugalis, Citation2014; Macleod & Jones, Citation2007).

Clearly, the fact that endogenous potentials are discussed under different names and from different research viewpoints gives the whole approach a certain ‘fuzziness’ regarding terminology. Tóth (Citation2014) traces the term ‘territorial capital’ back to policy-related documents issued at the turn of the new millennium; Camagni and Capello (Citation2013) then conceptualized this term from a rather quantitative perspective, with some authors subsequently adopting the terminology (e.g. Fratesi & Perucca, Citation2018; Jona, Citation2015). Other authors prefer the somewhat broader notion of ‘placed-based’ or ‘territorial potentials’, indicating (more correctly, in our view) that these regional assets may not initially be recognized and realized as useful, and have in fact to be pro-actively turned into a capital. This terminology has been adopted by authors such as Barca and Damsgaard as well as the European Union (e.g. ESPON, Citation2013a; Servillo, Atkinson, & Russo, Citation2012). Methodologically, while all approaches share the same basic understanding of what such place-based potentials or capitals are, they differ in regard to the applied qualitative or quantitative methods, these largely depending on the research focus (Lacquement & Chevalier, Citation2016; Tóth, Citation2017).

Here we follow Damsgaard et al. (Citation2009) in distinguishing between tangible and intangible potentials (ESPON, Citation2013a) (see ). Tangible potentials refer to the concrete, material legacies of human activity in settlements and landscapes. In (old) industrial regions addressed here, these might include mine dumps, old factory buildings, unused transport infrastructure and other features of post-industrial land- and townscapes. In contrast, intangible potentials refer to individual experiences, skills, knowledge and other competences, as well as cultural and social aspects of human existence present in the regions. These non-material potentials serve to anchor local people to their industrial heritage (identity) and cultural values, as well as maintaining traditions that shape the lives of the region’s inhabitants. Intangible potentials also include actor relations such as governance networks and capacities. Obviously, it is generally harder to operationalize immaterial factors for place-based development. Only a few real-world projects outside the tourist sector have attempted to exploit such potentials (Harfst & Simić, Citation2017), whereas there are many instances of old industrial sites being converted to new purposes (e.g. Overmann & Mieg, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Endogenous potentials and place-based development (own graphic based on Bentley & Pugalis, Citation2014; Damsgaard et al., Citation2009).

Whether and how these potentials are valorized and turned into place-based development strategies largely depends on the preferences, perceptions and capacities of local and regional actors as well as on the frameworks of European and national policies that can contribute to the construction of spatial constellations and challenges (Harfst et al., Citation2019). In general, the challenge in utilizing endogenous potentials is, first, to discover or enhance the specific (often unique) and meaningful potentials in cities and regions; and, second, to place them in the context of local or regional development. It should also be noted that the utilization of placed-based potentials is obviously more important in regions with low capabilities and opportunities to valorize external growth incentives.

2.2. Endogenous potentials and their role in European regional development policies

Alongside the academic discussion on endogenous potentials, the topic has also had significant ramifications in European regional development policies over the past few decades. Policies at regional, national and European level have targeted innovation and technology transfer. Research and policy-making in this area has aimed to analyze and strengthen growing regions (Kinossian, Citation2017; Servillo et al., Citation2012), with a wide body of academic literature confirming this interest (e.g. Lazzeroni, Bellini, Cortesi, & Loffredo, Citation2013; Moulaert & Sekia, Citation2003). Reflecting a new orientation in regional development policies at European level (European Commission, Citation2010), the focus has turned to smart specialization and regional innovation systems, so that growth and innovation potentials are being identified and exploited at the regional level (Asheim & Grillitsch, Citation2015; Foray, David, & Hall, Citation2011). However, most previous reference studies have only investigated successful (urban) regions (Martin, Citation2015; for a fundamental criticism see Hadjimichalis & Hudson, Citation2014). In this context, Tödtling and Trippl (Citation2004, p. 2) rightly point out that such ‘one size fits all’ solutions are often broadly applied to different regions; meaning that the ‘specific strengths and weaknesses of regions in terms of their industries, knowledge institutions, innovation potential and problems are frequently not taken into account’.

Endogenous potentials are now deeply embedded in EU strategies, in particular in the Territorial Agenda 2020 (European Commission, Citation2011), which builds on the objectives of the Europe 2020 strategy (European Commission, Citation2010) regarding employment, research, climate change, education and poverty reduction. The Territorial Agenda 2020 assumes that these objectives only can be achieved if their ‘territorial dimension’ is taken into account (European Commission, Citation2011, p. 2). This requires local and regional development strategies based on ‘territorial potentials’ (ibid., 2011, p. 3, paragraphs 11 and 28). For cities and regions, it is thus important to break down the general requirements and to determine their potentials more precisely, a step mainly done via the cohesion policy’s Operational Programmes (e.g. Harfst et al., Citation2019).

The approach now shapes multi-level governance settings at the European, national and regional/local levels also via many sub-policies, e.g. INTERREG programmes or the EU Commission’s Smart Specialisation Initiatives, such as the S3 platform, which seem highly relevant especially for those regions considered in this article (e.g. Avdikos & Chardas, Citation2016; Marques & Morgan, Citation2018; McCann, Citation2015).

2.3. Endogenous potentials and the development of small- and medium-sized towns

Around 56% of Europe’s urban population live in small or medium-sized towns, here understood as settlements with a population ranging from 5,000 to 100,000 inhabitants (Commission of the European Communities, Citation2011). Such towns are hugely diverse, reflecting their historic development, differing economic structures and social composition (Knox & Mayer, Citation2013). They generally provide a range of important functions, serving as local hubs for surrounding areas, supplying jobs and services as well as fostering social interaction and regional identities (e.g. Kwiatek-Sołtys, Mainet, Wiedermann, & Édouard, Citation2014; van Leeuwen, Citation2010).

The development of peripheral European regions characterized by small and medium-sized towns has attracted little research interest in past decades (e.g. Atkinson, Citation2017; Luukkonen, Citation2010). At the same time, recent policy documents such as the Territorial Agenda have explicitly highlighted the importance of a polycentric spatial development in Europe, underlining the role of small and medium-sized towns in fulfilling the goal of the Europe 2020 programme and cohesion policies. Some studies have now started to investigate the topic for peripheral regions (ESPON, Citation2013b; Servillo, Atkinson, & Hamdouch, Citation2017), while others have highlighted economic aspects of entrepreneurship and economic development in small and medium-sized towns (Carvalho & Vale, Citation2018; Kinossian, Citation2017; Vonnahme & Lang, Citation2017).

In order to address these gaps in research and policy-making, especially in the context of the EU’s cohesion policy, this article focuses on regions located outside agglomerations and which are suffering from sluggish development, specifically low growth rates, demographic shrinkage and ageing populations. As pointed out by Hoekstra, David, and Donner-Amnell (Citation2017), while such regions often have (or had) a core industrial activity, they are now undergoing major economic transformations, causing them to fall behind agglomerations with their stronger innovative potential (e.g. Cooke, Citation1995; Erickcek & McKinney, Citation2006; Simmie, Citation2003). The various problems afflicting such areas include weak external demand for products and services, a general loss of economic importance, a lack of economic innovation capacity (i.e. strong clusters of small and medium companies and research institutions) as well as a poorly skilled workforce and a small number of start-ups (Andersson & Karlsson, Citation2004), resulting in a so-called ‘regional innovation paradox’ (Healy, Citation2016). (Old) industrial towns, in particular, frequently face an additional barrier to development in the form of environmental problems such as polluted soil, as well as extensive degraded areas and brownfields (Thornton, Franz, Edwards, Pahlen, & Nathanail, Citation2007).

In the following, the authors present two case studies which investigate the use of specific endogenous potentials of (old) industrialized regions in order to generate positive momentum for development after a long process of structural change. Hereby the aim is to identify the opportunities and limits of utilizing endogenous potentials with a special focus on policy-setting rather than characterizing the ‘problem type’ of these regions as such.

3. Case studies

In this section we discuss two case studies from Central Europe drawn from the authors’ previous research work. Both are former mining and heavy industrial hubs, currently undergoing processes of structural transformation. These two were selected from a pool of potential case studies as they encompass a broad spectrum of endogenous development approaches in terms of contents as well as procedures. For the purposes of illustration, we provide insights from interviews with stakeholders, either conducted in 2018 or drawn from existing sources such regional media, data and document analysis, as well as previous work conducted by the authors (Marot, Citation2015; Marot & Cernic Mali, Citation2012; Marot & Harfst, Citation2012). The analysis takes particular account of EU funding instruments under the LEADER initiative and European Regional Development Fund programmes such as INTERREG.Footnote1 Such instruments have become key factors in the development of many regions. The presented research results were developed in the framework of various projects, mostly funded over the past decade by ERDF (INTERREG Central and Alpine Space).

3.1. Case study: the Zasavje region of Slovenia

3.1.1. Introduction to the region

With an area of only 485 km2, Zasavje is the smallest region in Slovenia and also the second smallest in terms of population (56,962 residents) (Statistical Office of The Republic of Slovenia, Citation2019b). Previously the region had a dynamic economy based on coal mining and related industries (e.g. chemicals, glass production, electro-technology, etc.). In recent decades Zasavje has faced many challenges, in particular the closure of its mines (between 1995 and 2012), the political and economic changes following Slovenian independence, and the recent economic crisis of 2008. The most critical problems today are the high unemployment rate (which hit a peak of 18% in 2014), population loss (falling 8% from 2008 to 2018; Statistical Office of The Republic of Slovenia, Citation2019a), environmental damage (soil erosion and pollution, destroyed woodlands, rock slides), as well as general economic restructuring and the need to create an overall vision for future development after the demise of heavy industry (Černič Mali, Klančišar, & Marot, Citation2009).

The region was among the first in Slovenia to benefit from EU assistance via the Phare Programme in 1994. This support helped establish a Regional Development Agency, a key institution that steered regional development for the next 15 years. The institutional framework was set up by the state by means of the Promotion of Balanced Regional Development Act (Citation2011). According to this act, the regional council is a decision-making body which, together with the state authorities, confirms the regional development programme (the main policy document in the region) and supervises the work of the agency. The members of the regional council are a mixed group of representatives from the business sector, the municipal administration, the public sector (health, social care, education) and civil society. Apart from this legally-anchored institutional framework, there exist several other institutions that function as active stakeholders in the utilization of potentials (NGOs, cultural institutions, private companies).

3.1.2. The identification and evaluation of endogenous potentials

To face the challenge of restructuring, various endogenous potentials were evaluated as important, depending on the period of transformation. In the first development phase immediately following the mine closures, most of the state funds secured for activities related to the end of mining were allocated towards restoring degraded post-mining landscapes and improving human resources. The major instrument to valorize endogenous potentials was (and still is) the regional development programme, a 7-year strategic and implementation document which defines the vision, development objectives and measures for implementation. The preparation of the document is obligatory and demanded by the state in order to create a basis for the absorption of European cohesion and national funds. The first programme for 2007–2013 (Regional Development Centre, Citation2007) was drawn up with the help of thematic work groups to take account of human resources, environmental and spatial planning as well as economic factors; however, there was little public participation. In contrast, the preparatory process for the second programme for 2014–2020 (Regional Development Agency Zasavje, Citation2015) was opened up from the outset: The general public as well as all other interested institutions and companies were invited to contribute project ideas and initiatives. An additional novelty of the current programme is that it demands a vertical and horizontal integration of funding and actors, a feature that accords with the territorially-based approach promoted by the EU.

Analysis of these two regional development programmes shows that the first programme does not specify as many endogenous potentials (viewed as strengths) as the second programme. While a similar number of tangible and intangible potentials are mentioned, mining structures and landscapes are identified as regional weaknesses rather than potentials. The greater emphasis on endogenous potentials in the current period can be attributed to the region’s need to align itself with the national smart specialization strategy, which is also a direct influence of EU policy (Governmental Office for the Development and Cohesion Policy, Citation2017). This has encouraged regional stakeholders to reflect on how they could best prosper and identify which sources could be valorized for this purpose. Specifically, companies involved in the 3E sector (i.e electro-technologies, electronics and energy production) along with local skills and knowledge are viewed as globally competitive (and thus good potentials), followed by the endogenous potentials of glass production, new materials, the chemical industry and tourism.

The evaluation of the previous development programmes gives a clear overview of how potentials have been valorized as well as the challenges facing the region. The global crisis was mentioned as a major factor forcing the region to rethink its priorities and identify ways to implement projects targeting endogenous potentials. In addition, various stakeholders have claimed that a change of values was required to successfully shift to a new development path away from heavy industry. To realize this, actions aimed at changing the regional identity were supported by rebranding measures changing the perception of a dirty, industrialized region to a ‘green place’, thereby promoting the region as a tourist destination. In general, improvements to the natural environment and land quality were prosecuted first, as these were demanded by mining law. Subsequently, activities were implemented to exploit the cultural heritage, progressing from traditional museum-based exhibitions to more innovative activities such as cultural festivals and even unique events on the national and macro-regional level, aimed at attracting a wider audience. Less attention has been placed on industrial culture and knowledge; instead, efforts have focused on establishing technologically-advanced activities unrelated to the heavy industrial processes of the past (RRA Zasavje, Citation2018). Further, the region’s previous reliance on the energy sector has gone into decline. Early attempts to foster the production of renewable energy have been unsuccessful due to a lack of scale: As Zasavje is too small for either biomass fields or solar parks, only a few isolated micro-scale generative units have been established in the region (Marot, Citation2012). Today, the most underused endogenous potentials are still the creativity, skills and knowledge of the local workforce. These could be valorized by, for example, fostering entrepreneurship. On the other hand, significant progress has been made in restoring the environment and post-mining landscapes, while some urban areas have been upgraded.

3.1.3. Valorization of endogenous potentials and place-based development

The valorization of Zasavje’s potentials is supported by three main funding channels: The EU Cohesion Policy, national incentives which target either mining areas or regions lagging behind, and local initiatives. In comparison to other Slovenian regions, Zasavje is only moderately active in the INTERREG funding scheme: In 2018 the region co-operated in five INTERREG-funded projects. More positively, the projects in which Zasavje is involved do target endogenous potentials, as for example the latest cross-border project ‘Inspiration’ aims to exploit the cultural value of industrial heritage.

Although several funding incentives have been established to utilize endogenous potentials, various studies as well as the interviews conducted with the main decision-makers have revealed the insufficient know-how and human capacity in Zasavje to absorb all these funds, exacerbated by the low entrepreneurial drive to create new companies (Marot, Citation2012; Marot & Harfst, Citation2012). Specifically, young unemployed people seem reluctant to found their own companies (Marot, Citation2015). As a result, Zasavje region ‘exports’ the majority of its workforce to other regions of Slovenia, as in 2017 52% of the working population (approx. 23,000 people) commuted to other areas – the highest percentage of all Slovenian regions (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, Citation2018).

Regarding the opinions of local and regional decision-makers, interviews conducted with the three mayors (Gabrič, Citation2018; Jerič, Citation2017; Švagan, Citation2018) and the director of the regional development agency (Špitalar, Citation2016) reveal a shift in their perception of where responsibility lies for regional development and prosperity. Unlike 10 years previously, the decision-makers now understand that state support only provides limited benefits to local communities. In contrast, development initiatives originating at the local level and business ideas co-created in a multi-actor local environment in a bottom-up manner can boost the regional economy over the long term. Today all municipalities seek close cooperation with local entrepreneurs and investors.

Over the last ten years there has also been a sea change in stakeholders’ perception of the industrial past and the related development path. A study conducted in 2004 (Marot, Citation2005) showed that the focus of local people regarding jobs and future opportunities was still highly invested in the mining past. Yet today the mayors of the two municipalities -where mining activities ceased first- have been able to shift strategic objectives from mine-related economic activities to other alternative economic futures.

3.2. Case study: Oelsnitz region in Germany’s Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge)

3.2.1. Introduction to the study area

The town of Oelsnitz is situated in eastern Germany, 25 kilometres west of the city of Chemnitz. With about 11,000 inhabitants (2017), the town is functionally connected to the larger Chemnitz conurbation, a thriving economic area home to medium-sized companies and a large variety of industries. The biggest local economic player in the conurbation is the Volkswagen Company, employing a workforce of about 10,000 in its Zwickau car plant (Volkswagen Sachsen, Citation2019). The town of Oelsnitz looks back on a long tradition of coal mining, the legacy of which is being utilized as an endogenous potential for regional development and as a component of place-making.

Until the 1970s, the Zwickau-Lugau-Oelsnitz district was the coal-mining hub of Saxony. From the nineteenth century, the coal industry also provided the impetus for the rapid industrial development of the cities of Chemnitz and Zwickau, making this zone a Central European hub of textile production, manufacturing and the car industry (Kowalke, Citation2000). The end of coal mining in the 1970s was a decisive turning point, leading to an intensive process of regional transformation. In the first phase of transformation, under the central planning system of the German Democratic Republic, the economic thrust was shifted towards re-industrialization: In Oelsnitz alone, 4,800 jobs were newly created in 18 industrial operations, largely in the fields of electrical engineering and construction (Stemmler & Vogel, Citation1997). In the second phase, following German unification, there was a drastic change of direction when jobs were lost across all industrial branches. The socio-economic policy now aimed to establish a new economic basis in fields such as metal processing and electrical engineering by promoting small and medium-sized enterprises, thereby creating new jobs. At the same time, and despite political action at all levels, the population in the wider region declined from 200,000 to about 154,000 in the period 1990–2017 as a result of outmigration and low birth rates.

3.2.2. The identification and evaluation of endogenous potentials

In 2003 nine former coal-mining municipalities from the region submitted a ‘Charter of Demands’ to the Saxon Ministry of the Interior, which is responsible for spatial planning and development in Saxony. Two years later the municipalities decided to collaborate closer in the utilization of their coal-mining legacies, adopting a common Regional Development Concept (RDC), encompassing all former coal-mining sites. Four fields of joint action were defined as follows: (1) brownfield development; (2) tourism; (3) open spaces; and (4) demographic change and infrastructure.

The mining heritage has become a decisive factor in the realization of these general development aims. Retrospectively, we can identify four groups of endogenous potentials. As these are most visible in Oelsnitz, the following detailed description focuses on this town:

The first potential is the post-mining landscape, which includes spoil tips, areas of surface subsidence as well as underground mine water. These are challenging to manage in view of the various hazards they present such as unstable underground, landslides and rising mine water. As a result of the above-mentioned RDC, the Saxon government has been involved in measures since 2007 to rehabilitate former mining areas in the Operational Programme of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (Sächsisches Oberbergamt, Citation2016). Among other utilizations of endogenous potentials, a state-of-the-art visitor tower was erected on the highest spoil tip in the town. Attempts to use biomass from tips as well as the burning of coal gob for energy production have proved unsuccessful.

A second development path has been the reuse of brownfields left by the coal industry. In fact, the GDR authorities already redeveloped several collieries for new purposes. After 1990 new industrial or commercial areas emerged on the former mining sites (IRFootnote2). The most extensive reutilization project has been the town council’s decision to locate the Saxon Horticultural Exhibition of 2015 on Oelsnitz’s old coal railway terminal (IR). More than 400,000 people visited the exhibition during its 6-month duration, and today the area is used as a municipal park (Sächsisches Oberbergamt, Citation2016).

A third approach is related to heritage protection and development. One example of this is the transformation of the Miners’ Cultural Centre, erected in 1956, into a leisure and concert venue. Oelsnitz’s flagship project to exploit its industrial heritage is the Saxon Museum of Mining, housed in a former mining building. The museum, which opened in 1986, commemorates the history of hard coal mining in Saxony (Stemmler & Vogel, Citation1997) and today is a heritage site of regional importance (IR). The museum is also an educational centre for diverse users, offering various educational tours for schools (Bergbaumuseum Oelsnitz, Citation2018).

The museum staff can also be viewed as a primary factor in the maintenance of miners’ traditions, the fourth group of endogenous potentials. For example, the staff members undertake voluntary work to organize various events such as mining parades and groups wearing traditional work clothes. Further, about 20 voluntary tour guides have been trained since 2015, initially to assist at the Horticultural Exhibition, and later extending their activities to mining history, industrial culture and the post-mining landscape (IR).

3.2.3. Valorization of endogenous potentials and place-based development

Our analysis reveals the strategic factors behind the valorization of the named potentials. One pathway has been the municipal collaboration with regional and state authorities, resulting in the allocation of considerable state and EU funding for rehabilitation and to prepare for investments. Cooperation with academic institutions has also pinpointed solutions for risk reduction in dealing with the physical legacy of mining.

Another factor in the valorization of potentials has been the previously mentioned strategic regional cooperation. This non-statutory, inter-communal coalition created a regional development concept, and has been recognized by the Saxon government as the coordinative unit for ERDF support in the former mining district. Since the end of the 1990s, Oelsnitz and neighbouring communities have also been involved in European development projects in the framework of the INTERREG programme, namely REVI, READY, ReSource, SHIFT-X, VODAMIN (FLOEZ Association, Citation2018). This EU cooperation has not only led to an intensive exchange of experiences with other mining towns in Germany and elsewhere, but also to the funding of small projects and follow-up activities. Last but not least, the town council’s promotion of various festivals, in particular, the Horticultural Exhibition in 2015, has been key to ensuring the involvement of the local population in the process (IR).

All these initiatives and activities can be described as a mixture of urban development, risk management, heritage preservation and the maintenance of traditions. One particular force in local policy-making was the mayor of Oelsnitz from 1990 to 2015. He was esteemed as a charismatic leader, standing for a pro-active handling of local affairs, harmonizing the political parties in the town, establishing strategic alliances with state authorities and launching high-profile projects and events (IR). By initiating the first regional mining conference in 1990, he helped encourage an understanding of the (physical and social) mining legacy as not merely a burden on urban development but also a driver for urban renewal.

Furthermore, the mayor could inspire a network of actors, in particular a group of elderly mining engineers. This group had good connections into politics, science and academia, providing important network connections for the wider region and its challenges. These actors did secure funding and academic expertise. Another group lobbied for the continued existence of the Mining Museum, strongly fostered the maintenance of mining traditions (intangible potential) and supported several activities of heritage protection and the preservation of local traditions (IR).

Despite this apparent ‘success story’ (IR), the process has not been without conflicts and setbacks. Some locals say that municipal policy in Oelsnitz neglected for too long the preservation and exploitation of the local tradition of mining (IR). Despite some investment, the town centre can be described as rather unattractive (IR). The suggestion of the local government to use mine water for health purposes has been described as naive, in particular after an initial chemical analysis showed no health-giving properties (IR). Furthermore, regional cooperation initiatives are clearly focused on the acquisition and distribution of public funds rather than on creating a common development strategy; hence, there is little involvement of local initiatives outside the ‘inner circle’.

Notwithstanding such uncertainties and a changing political emphasis, reliability has become a trademark of the town, with the next highlight already in preparation: In 2020 the Saxon State Exhibition – an irregular exhibition examining various topics of Saxon history – will open at seven different locations across Saxony under the title ‘Industry, Culture & Man’. One of these locations will be the Mining Museum in Oelsnitz.

4. Discussion

The case studies presented above confirm the general assumption that (old) industrial regions in Central Europe often face the combined challenges of poor economic development, negative demographic trends and loss of functions, especially when situated outside agglomeration areas. These challenges persist even if many core industries are still active or have been replaced with other branches, as in the German case discussed above. The Slovenian case highlights the general difficulty of establishing dynamic and innovative growth clusters, even when there are innovative companies in the region.

The two case studies also provide some answers to the initial guiding questions of this article, namely the valorization of endogenous potentials, as well as the influence of European regional policy in these approaches. The analysis highlights the utilization of both types of potentials by means of European funds across both regions. As a first result, we are unable to pinpoint one single model that can be successfully employed to valorize endogenous potentials. Rather, the two regions have made use of highly disparate governance systems to identify and develop their potentials (albeit drawing from similar funding programmes). The Slovenian case is deeply embedded in a strategic top-down system, spanning a multi-level governance setting that absorbs EU and national funding in order to shape regional/local strategies and implementations. In contrast, the approach in the German case study was far more incremental. Initially there was no coherent strategy at regional level; instead, a common strategy was developed from the bottom up in a step-by-step process by means of a non-statutory inter-communal cooperation initiative, which focused on practical solutions through several core projects. The region has been transformed significantly through the initiative of one municipality, creating a regional bandwagon effect which eventually impacted the district level.

The selected cases both show how the approach to use potentials has shifted over time, closely reflecting the perceptions and ideas of major decision-makers as well as the changing framework conditions on EU level. In Slovenia, we can particularly identify a change in the mode of governance. At first the region and local communities relied heavily on national interventions in their early strategic programmes; it was only later that they began to apply for EU funds. Today their approach is far more shaped and integrated at the local level: While national support is still important, ideas and development concepts are now generated locally, with additional regional actors. In the German case, the strong influence of a charismatic leader along with a small ‘inner circle’ led to a focus on tangible potentials.

Considering the types of potentials used, in both regions we find material and immaterial factors addressed over time. Interestingly, a common evolution can be traced in the two case studies: In a first stage, utilization often focused on landscape elements, the upgrading of urban spaces and environmental remediation (including the risk management of industrial remains and brownfields). Later approaches viewed the industrial remains more as a strategic potential and a starting point for industrial diversification and entrepreneurship.

The Slovenian case also makes direct and sustained reference to European initiatives such as the S3 Smart Specialisation Platform, identifying core clusters and broadening the actor base in order to streamline the utilization of endogenous potentials according to a quadruple helix model. In practice, however, this strategic orientation has not been realized in the form of concrete interventions. In the German case study, personal networks and relationships were the primary drivers at the beginning of the renewal process with technical and engineering projects dominating the activities over a longer period.

Similarities can be identified in the two regions’ utilization of their cultural heritage. The types of valorization can be divided into two groups, distinguished by the form of heritage or by the approach. By ‘approach’ we mean the traditional, museum-type of representation in the form of exhibitions (more advanced options envisage interaction with the visitors) as well as more modern elements rooted in creative industries, focussing on intangible potentials connected to the creation of new products based on past traditions and production processes, the organization of festivals around new topics, or new media. These initiatives, which are shaped by local knowledge and creativeness, do not primarily aim at job creation but rather the preservation of local culture and identity (see ).

Table 1. Types of valorization.

Ongoing EU funding opportunities to exploit endogenous potentials have obviously changed the perception of local resources from burdens to strategic development potentials in both cases. The focus has evolved from crisis intervention to a strategic approach that utilizes various (post-) industrial potentials. In the Slovenian case, we can see that regional stakeholders are coordinated within an actor’s network-based innovation system, as advocated by the European Union. The process became over time a wider network of stakeholders, more receptive to joint development of projects and better at applying for diverse funding sources. Clearly, the EU’s funding instruments have directly influenced the understanding and shaping of regional development.

In the German case, this direct link to EU funding was little explored in the 1990s, when the region’s primary aim was to gain national funding. However, since around 2000, EU funding has also risen in importance in this case study through participation in the INTERREG programme; in 2007 it became fundamental through the framework of EU Operational Programmes. The regional actor’s network was also poorly institutionalized in the initial development phase, a situation that has slowly changed since 2000.

5. Conclusion

In this article we confirm the general observation that the reality of development in non-agglomeration regions is more complex and difficult than ‘good practice’ examples often suggest. This can be attributed to a unique mixture of place-specific regional development factors. In the investigated case studies, the legacy of former industries has played a decisive role in determining the development conditions and providing diverse potentials for place making such as the post-mining landscape, the built heritage, brownfields, local customs and knowledge, etc.

While the focus in this article has been on (old) industrial regions with small and medium-sized towns, we can draw three general conclusions for other areas facing structural problems: Firstly, from the great variety of endogenous potentials, regions must first identify and prioritize the potentials to valorize. Secondly, local actors are primarily responsible for choosing ways of utilizing potentials and exploring synergies with other existing regional activities. And thirdly, the political framework conditions both on local, as well as on European level play an important role in either promoting or hampering the use of endogenous potentials.

The investigation highlights the overall importance of endogenous potentials at local and regional level by means of the European Union’s 2014–2020 regional policy agenda. We have shed light on the multi-level governance arrangements built around the identification and utilization of such potentials to show how this policy agenda filters through lower policy levels. The case studies show the importance of such aspects for regional development, especially in (old) industrialized regions. Here the European regional policy agenda has clearly had an impact by providing funding instruments, triggering local and regional action within these policies, enabling investments and capacity building.

Our discussion has also (at least in part) revealed an evolution in the way potentials are identified and valorized over time, shifting in focus from project-based interventions and tangible remains such as buildings and landscapes towards more strategic embedding and intangible elements such as skills, product innovation and networks. These shifts correspond to the European Union’s innovation agenda. However, we have also shown the difficulty in applying complex concepts of regional development such as smart specialization to smaller regions due to their limited human and governance capacities.

In this respect, it must be questioned whether the laborious and time-consuming development of such potentials is worthwhile, either from the perspective of the affected regions or from the EU. The ‘hard’ aims of the European programme agenda, i.e. economic growth, job creation and social cohesion, are scarcely met by the utilization of endogenous potentials. Yet instead of negatively assessing this fact, perhaps it would be better to ask: Are we posing the right questions when our aim is rather to boost the development of structurally weak regions in general?

Our discussion has shown that the regional influence of endogenous potentials is much wider-ranging that solely their direct economic impact. It is important to consider their indirect effects. In this regard, factors such as inherited knowledge, identity and tradition can serve to enable endogenous development.

Here we make a strong argument for extending previous concepts of endogenous development, which have mainly focused on material aspects of growth and job creation. Based on our findings, endogenous potentials should rather be interpreted more comprehensively to extend the range of likely impacts. This will help certain regions to establish new networks and attract funding, which are just those pre-conditions required for economic growth and higher employment. With the help of relevant stakeholders such as former industrial workers, knowledge can be created and disseminated via corresponding networks. These ideas can spark the interest of politicians and entrepreneurs, who in turn will trigger new development processes in what we call a ‘catalyst function’. In particular, the impact on ‘identity’ seems to be important: The utilization of endogenous potentials highlights the uniqueness of a region (unique selling propositions) to outsiders, as well improving its self-image, which is often negatively impacted by structural change. In addition, the use of such potentials can also have a ‘symbolic function’ by signalling the efficiency and willingness of regional stakeholders to act, attracting outside attention and improving internal self-esteem and trust in regional networks.

As discussed in a previous paper (Harfst & Wirth, Citation2014), these three wider impacts of endogenous potentials, namely their catalyst, identity and symbolic functions, should be introduced into the European Union’s policy agendas and aims. This will entail a revision of basic target criteria for development to take account of such ‘soft’ categories, which are difficult to measure. The strict focus on growth and jobs in the recent programming period of EU-funded measures is too narrow to capture the full picture of endogenous development. An important aspect in this regard is the improvement of local/regional capacity to act. This could mean to support regions lagging behind by establishing creative units guiding an integrated process of renewal together with relevant regional actors and external knowledge or to provide (as in past cohesion policies) separate funds for such regions. Such solutions are required in the next funding period if the EU aims to provide effective assistance at the regional level, especially in the case of (old-) industrial regions discussed here.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 LEADER supports rural development projects initiated at the local level aimed at revitalizing rural areas and creating jobs, while INTERREG aims to stimulate cooperation between regions in different member states.

2 IR = Interview Result.

References

- Andersson, M., & Karlsson, C. (2004). Regional innovation systems in small & medium-sized regions. A critical review & assessment. Cesis Elektronic Working Paper Series 10. Stockholm. Retrieved from http://www.kth.se/dokument/itm/cesis/CESISWP10.pdf

- Asheim, B., & Grillitsch, M. (2015). Smart specialisation: Sources for new path development in a peripheral manufacturing region. Papers in Innovation Studies 2015/11, Lund University, CIRCLE – Center for Innovation, Research and Competences in the Learning Economy. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/lucirc/2015_011.html

- Atkinson, R. (2017). Policies for small and medium-sized towns: European, national and local approaches. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 108(4), 472–487. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12253

- Avdikos, V., & Chardas, A. (2016). European Union cohesion policy post 2014: More (Place-based and conditional) growth – less redistribution and cohesion. Territory, Politics, Governance, 4, 97–117. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2014.992460

- Barca, F. (2009). An agenda for a reformed cohesion policy. A place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations. Retrieved from http://www.ecostat.unical.it/Dorio/Corsi/Corsi202017/Politiche20Sviluppo20Locale/Materiale20poleco/report_barca_v0306.pdf

- Bentley, G., & Pugalis, L. (2014). Shifting paradigms: People-centred models, active regional development, space-blind policies and place-based approaches. Local Economy, 29, 283–294. doi: 10.1177/0269094214541355

- Bergbaumuseum Oelsnitz. (2018). Bergbaumuseum Oelsnitz/Erzgebirge [Mining museum Oelsnitz/Ore Mountains]. Official Homepage. Retrieved from https://www.bergbaumuseum-oelsnitz.de

- Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2013). Regional competitiveness and territorial capital: A conceptual approach and empirical evidence from the European Union. Regional Studies, 47(9), 1383–1402. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.681640

- Carvalho, L., & Vale, M. (2018). Biotech by bricolage? Agency, institutional relatedness and new path development in peripheral regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, the Economy and Society, 11(2), 275–295. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsy009

- Commission of the European Communities. (2011). Cities of tomorrow. challenges, visions, ways forward. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

- Cooke, P. (Ed.). (1995). The rise of the rustbelt. London: Routledge.

- Černič Mali, B., Klančišar, K., & Marot, N. (2009). Regional profile of Zasavje region. Ljubljana: Urban Planning Institute of the Republic of Slovenia.

- Damsgaard, O., Lindquvist, M., Roto, J., & Sterling, J. (2009). Territorial potentials in the European Union (Nordregio Working Paper 2009: 6). Stockholm: Nordregio.

- Dunford, M., & Smith, A. (2000). Catching up or falling behind? Economic performance and regional trajectories in the “New Europe”. Economic Geography, 76, 169–195. doi: 10.2307/144552

- Erickcek, G., & McKinney, H. (2006). “Small cities blues”: Looking for growth factors in small and medium-sized cities. Economic Development Quarterly, 20(3), 232–258. doi: 10.1177/0891242406290377

- ESPON. (2006). The Role of Small and Medium-Sized Towns (SMESTO). Final Report. Retrieved from https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/fr-1.4.1_revised-full.pdf

- ESPON. (2013a). Detecting Territorial Potentials and Challenges (DeTeC). Retrieved from https://www.espon.eu/programme/projects/espon-2013/scientific-platform/detec-detecting-territorial-potentials-and

- ESPON. (2013b). TOWN – Small and Medium-Sized Town. Retrieved from https://www.espon.eu/programme/projects/espon-2013/applied-research/town-E280%93-small-and-medium-sized-town

- European Commission. (2010). EUROPE 2020. A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. (2011). Territorial agenda of the European Union 2020. Towards an inclusive, smart and sustainable Europe of diverse regions. Agreed at the informal ministerial meeting of ministers responsible for spatial planning and territorial development on 19th May 2011, Gödöllő, Hungary. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2011/territorial-agenda-of-the-european-union-2020

- FLOEZ Association. (2018). Future of Lugau-Oelsnitz-Zwickau. Zusammenarbeit in der ehemaligen Steinkohlenbergbauregion [Collaboration within a former coal mining region]. Retrieved from http://floez-sachsen.de/Projekte

- Foray, D., David, P., & Hall, B. (2011). Smart specialization. From academic idea to political instrument. The surprising career of a concept and the difficulties involved in its implementation. Working paper. Retrived from http://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/170252

- Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2018). Territorial capital and the resilience of European regions. Annals of Regional Science, 60(2), 241–264. doi: 10.1007/s00168-017-0828-3

- Gabrič, J. (2018). Moj cilj je, da v prihodnje postanemo vodilni na področju trajnostnega razvoja mesta, z visoko kakovostjo življenja in z nizko brezposelnostjo. (Interview) Srečno Trbovlje, 25, 6–8.

- Governmental Office for the Development and Cohesion Policy. (2017). Slovenia’s smart specialisation strategy. Retrieved from http://www.svrk.gov.si/fileadmin/svrk.gov.si/pageuploads/Dokumenti_za_objavo_na_vstopni_strani/S4_dokument_V_2017EN.pdf

- Hadjimichalis, C., & Hudson, R. (2014). Contemporary crisis across Europe and the crisis of regional development theories. Regional Studies, 48, 208–218. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.834044

- Harfst, J., & Simić, D. (2017). Industrial culture as an emerging topic in regional development? Proceedings of the 3rd Geobalcanica Conference 2017 (pp. 147–153). Retrieved from http://geobalcanica.org/wp-content/uploads/GBP/2017/GBP2017.20.pdf

- Harfst, J., & Wirth, P. (2014). Zur Bedeutung endogener Potenziale in klein- und mittelstädtisch geprägten Regionen – Überlegungen vor dem Hintergrund der Territorialen Agenda 2020. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 72, 463–475. doi: 10.1007/s13147-014-0312-9

- Harfst, J., Wirth, P., & Simić, D. (2019). Utilising endogenous potentials via regional policy-led development initiatives in (post-) industrial regions of Central Europe. In M. Finka, M. Jaššo, & M. Husar (Eds.), The role of public sector in local economic and territorial development (pp. 43–58). Cham: Springer.

- Healy, A. (2016). Smart specialization in a centralized state: Strengthening the regional contribution in North East Romania. European Planning Studies, 24(8), 1527–1543. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1184233

- Hoekstra, M., David, B., Donner-Amnell, J., & 14 other authors. (2017). Economic performance and place-based characteristics of industrial regions in Europe. Technical Report. Retrieved from: www.researchgate.net/publication/325195233_Economic_performance_and_place-based_characteristics_of_industrial_regions_in_Europe

- Jerič, M. (2017, July 21st). Z županovanjem zaključujem [I am finishing my job as a mayor]. Retrieved from: https://savus.si/miran-jeric-z-zupanovanjem-zakljucujem/

- Jona, G. (2015). Determinants of Hungarian sub-regions’ territorial capital (2015). European Spatial Research and Policy, 22(1), 101–119. doi: 10.1515/esrp-2015-0019

- Kinossian, N. (2017). Planning strategies and practices in non-core regions: A critical response. European Planning Studies, 26(2), 365–375. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1361606

- Knox, P., & Mayer, H. (2013). Small town sustainability: Economic, social, and environmental innovation (2nd ed.). Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Kowalke, H. (2000). Sachsen [Saxony]. Gotha: Klett.

- Kwiatek-Sołtys, A., Mainet, H., Wiedermann, K., & Édouard, J. (Eds.). (2014). Small and medium towns’ attractiveness at the beginning of the 21st century. Clermond-Ferrand: Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal.

- Lacquement, G., & Chevalier, P. (2016). Territorial capital and development of local territories, theoretical and methodological issues raised when transposing a concept of territorial economy into geographic analysis. Annales de Geographie, 711(5), 490–518. doi: 10.3917/ag.711.0490

- Lazzeroni, M., Bellini, N., Cortesi, G., & Loffredo, A. (2013). The territorial approach to cultural economy: New opportunities for the development of small towns. European Planning Studies, 21, 452–472. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.722920

- Luukkonen, J. (2010). Territorial cohesion policy in the light of peripherality. Town Planning Review, 81(4), 445–466. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2010.12

- Macleod, G., & Jones, M. (2007). Territorial, scalar, networked, connected: In what sense a ‘regional world’? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1177–1191. doi: 10.1080/00343400701646182

- Marot, N. (2005). Regionalna identiteta mladih v Zasavju. Geografski Vestnik, 77(1), 37–48.

- Marot, N. (2012). Zasavje (Slovenia)–A region reinventing itself. In P. Wirth, W. Fischer, & B. Černič Mali (Eds.), Post-mining regions in central europe-problems, potentials, possibilities (pp. 104–117). Munchen: Oekom.

- Marot, N. (2015). Youth: The motor of redevelopment in mid-sized post-industrial towns. Economic and Business Review for Central and South-Eastern Europe, 17(2), 223.

- Marot, N., & Cernic Mali, B. (2012). Using potentials of post-mining regions–a good practice overview of Central Europe. In P. Wirth, W. Fischer, & B. Černič Mali (Eds.), Post-mining regions in central europe-problems, potentials, possibilities (pp. 130–147). Munchen: Oekom.

- Marot, N., & Harfst, J. (2012). Post-mining potentials and redevelopment of former mining regions in central europe–case studies from Germany and Slovenia. Acta Geographica Slovenica, 52(1), 99–119. doi: 10.3986/AGS52104

- Marques, P., & Morgan, K. (2018). The heroic assumptions of smart specialisation: A sympathetic critique of regional innovation policy. In A. Isaksen, R. Martin, & M. Trippl (Eds.), New avenues for regional innovation systems – Theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 275–293). Cham: Springer.

- Martin, R. (2015). Rebalancing the spatial economy: The challenge for regional theory. Territory, Politics and Governance, 3(3), 235–272. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2015.1064825

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (1998). Slow convergence? The new endogenous growth theory and regional development. Economic Geography, 74, 201–227. doi: 10.2307/144374

- McCann, P. (2015). The regional and urban policy of the European Union: Cohesion, results-orientation and smart specialisation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mendez, C. (2013). The post-2013 reform of EU cohesion policy and the place-based narrative. Journal of European Public Policy, 20, 639–659. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2012.736733

- Morgan, K. (2013). Path dependence and the state: The politics of novelty in old industrialised regions. In P. Cooke (Ed.), Re-framing regional development: Evolution, innovation and transition (pp. 318–340). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Moulaert, F., & Sekia, F. (2003). Territorial innovation models: A critical survey. Regional Studies, 37, 289–302. doi: 10.1080/0034340032000065442

- Myrdal, G. (1957). Economic theory and underdeveloped regions. London: Duckworth.

- Overmann, H., & Mieg, H. (Eds.). (2014). Industrial heritage sites in transformation: Clash of discourses (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Petrakos, G., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Rovolis, A. (2005). Growth, integration, and regional disparities in the European Union. Environment & Planning A, 37, 1837–1855. doi: 10.1068/a37348

- Promotion of Balanced Regional Development Act. (2011). Official gazzette of the Republic of Slovenia, 20/11.

- Regional Development Agency. (2015). RRP Zasavje: RRP zasavske regije 2014–2020 [Regional development programme of Zasavje region 2014–2020]. Zagorje ob Savi: Regional Development Centre.

- Regional Development Centre. (2007). Regional development programme of the Zasavje region for the period 2007–2013. Zagorje ob Savi: Regional Development Centre.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- RRA Zasavje. (2018). On-line information about the organization and activities of the Regional Council of Zasavje and Development Council of Zasavje. Retrieved from: https://www.rra-zasavje.si/si/regionalni-razvoj/

- Sächsisches Oberbergamt (Ed.). (2016). Der Bergbau in Sachsen. Bericht für das Jahr 2015 [Mining in Saxony. Report about the year 2015]. Retrieved from: http://www.oba.sachsen.de/download/2016_11_09_JB2015_Druckfassung.pdf

- Servillo, L., Atkinson, R., & Hamdouch, A. (2017). Small and medium-sized towns in Europe: Conceptual, methodological and policy issues. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 108, 365–379. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12252

- Servillo, L., Atkinson, R., & Russo, A. (2012). Territorial attractiveness in EU urban and spatial policy: A critical review and future research agenda. European Urban and Regional Studies, 19(4), 349–365. doi: 10.1177/0969776411430289

- Simmie, J. (2003). Innovation and urban regions as national and international nodes for the transfer and sharing of knowledge. Regional Studies, 37(6–7), 607–620. doi: 10.1080/0034340032000108714

- Špitalar, T. (2016, May 2nd). Interview with the director of the Regional Development Agency Zasavje. Retrieved from: http://etv.elektroprom.si/template/pogovor_meseca/tadej_spitalar/

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. (2018). Data on the commuters. Retrieved from: https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatDb/pxweb/sl/10_Dem_soc/10_Dem_soc__07_trg_dela__05_akt_preb_po_regis_virih__09_07727_del_mig_kazal/0772755S.px/

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. (2019a). Data about the regions’ population. Retrieved from: https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatDb/pxweb/sl/10_Dem_soc/10_Dem_soc__05_prebivalstvo__10_stevilo_preb__10_05C20_prebivalstvo_stat_regije/?tablelist=true

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. (2019b). Data about the regions’ area and population. Retrieved from: https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatDb/pxweb/en/50_Arhiv/50_Arhiv__02_upravna_razdelitev__02148_terit_enote/0214819S.px/

- Stemmler, G., & Vogel, R. (1997). Oelsnitz im Erzgebirge 1940–1990. Gesicht einer Stadt. [Oelsnitz in the Ore Mountains 1940–1090. Face of a town]. Hohenstein-Ernstthal: Oehme.

- Stough, R., Stimson, R., & Nijkamp, P. (2011). An endogenous perspective on regional development and growth. In K. Kourtit, P. Nijkamp, & R. Stough (Eds.), Drivers of innovation, entrepreneurship and regional dynamics (pp. 3–20). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Švagan, M. (2018, November 3rd). Matjaž Švagan kandidat za župana Zagorja ob Savi [Matjaž Švagan, the candidate for the mayor of Zagorje]. Retrieved from: https://savus.si/matjaz-svagan-kandidat-za-zupana-zagorja-ob-savi/

- Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2004). One size fits all? Towards a differentiated policy approach with respect to regional innovation systems. (SRE Discussion papers 2004/1). Retrived from http://epub.wu.ac.at/944/

- Thornton, G., Franz, M., Edwards, D., Pahlen, G., & Nathanail, P. (2007). The challenge of sustainability: Incentives for brownfield regeneration in Europe. Environmental Science & Policy, 10(2), 116–134. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2006.08.008

- Tóth, B. (2014). Territorial capital: Theory, empirics and critical remarks. European Planning Studies, 23(7), 1327–1344. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2014.928675

- Tóth, B. (2017). Territorial capital – a fuzzy policy-driven concept: Context, issues, and perspectives. Europa XXI, 33, 5–19. doi: 10.7163/Eu21.2017.33.1

- van Leeuwen, E. (2010). Urban-rural interactions: Towns as focus points in rural development. Heidelberg: Verlag.

- Volkswagen Sachsen. (2019). Zahlen und Fakten [Facts and figures]. Retrieved from: https://www.volkswagen-sachsen.de/de/unternehmen/zahlen-und-fakten.html

- Vonnahme, L., & Lang, T. (2017). Rethinking territorial innovation: World market leaders outside of agglomerations (Working paper series SFB 1199). Leipzig: Universität Leipzig. Retrieved from www.researchgate.net/publication/321678712_Rethinking_Territorial_Innovation_World_Market_Leaders_outside_of_Agglomerations

- Wirth, P., Elis, V., Müller, B., & Yamamoto, K. (2016). Peripheralisation of small towns in Germany and Japan – dealing with economic decline and population loss. Journal of Rural Studies, 47, 62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.07.021