ABSTRACT

Research on social innovation has gained momentum over the last decade, spurred notably by the growing interest in social issues related to policy making, public management and entrepreneurship in response to the wicked problems societies in Europe and worldwide face. Its popularity among academics and policy makers also marks a turning point in how innovations are thought of and what their role in economic development is. However, for social innovations to unfold their full potential for the beneficiaries and societies at large a better understanding of underlying mechanisms, processes and impacts is necessary. Focusing on ‘the economics of social innovation’, this special issue addresses a widely neglected topic in regional development. The contributions cover distinct but complementary and related aspects concerning the existing gap between the hitherto unexploited potential of social innovation in relation to the complex and interrelated socio-economic challenges regions across Europe and globally face. This editorial provides a brief introduction in the Special Issue’s general theme followed by an overview of the lines of argumentation and main results of the contributions. It concludes with an outlook on future research.

Introduction: economics of social innovation

Regions across Europe are confronted with many complex and interrelated socio-economic challenges – including, amongst others, distributional inequality, climate change, digitization, demographic change, gentrification, long-term and youth unemployment – that have clearly been exacerbated by the economic crisis. While several regions are still recovering from the aftermath of the financial and economic crises, periods of ongoing growth have clearly come to a halt for many regions in Europe (Leick & Lang, Citation2017). Economic growth is projected to fall from 2.3% in 2018 to 1.4% in 2019 with a modest forecasted recovery for 2020, with growth reaching 1.8% (IMF, Citation2019). Welfare services struggle to cope with budgetary constraints and growing segments of the population experience increasing difficulty in accessing support. ‘Yet, people in Europe […] are dissatisfied with the status quo and, as in regions that exhibit greater inequality, demand changes’ (Bussolo et al., Citation2019, p. 1). While the key role of traditional for-profit innovation in boosting regional economic activity and social development is generally accepted, their impact on successfully addressing the outlined challenges appear insufficient. Consequently, new solutions leading to improved capabilities, new forms of collaboration and power distribution, and better use of societal resources are required. In this context, emerging social innovations in Europe and around the world are perceived as a way forward to sustainably address the problems at hand. In recent years it has become increasingly apparent that innovations transcend the technology, science, and economic sphere; they emerge everywhere in society as mirrored in the many social innovation activities in Europe and worldwide (cf. Howaldt et al., Citation2016; Pelka & Terstriep, Citation2016; Terstriep, Citation2016). Social actors and policymakers alike build their hopes on the ‘transformative power’ ascribed to social innovation. In this context, the Bureau of European Policy Advisors (BEPA) points out that ‘[a]t a time of major budgetary constraints, social innovation is an effective way of responding to social challenges, by mobilising people's creativity to develop solutions and make better use of scarce resources’ (BEPA, Citation2010, p. 7). Mirrored in the Europe 2020 strategy – the European Union’s ten-year agenda for growth and jobs is reported to posit ‘social innovation as another way to produce value, with less focus on financial profit and more on real demands or needs’ (BEPA, Citation2014, p. 8) – significant funding for research on social innovation has been provided by the European Commission, mainly through the 7th Framework Programme and Horizon 2020. In fact, the former provided the funding for the research that amongst others informs this Special Issue via the SIMPACT,Footnote1 TRANSITFootnote2 and SI-DriveFootnote3 project. In addition, social innovation has become part of the social investment package, and is to be embedded in policy making and connected to social priority, for example, within the European Social Fund or the Programme for Employment and Social Innovation (EaSI) (for an overview see Von Jacobi et al., Citation2017).

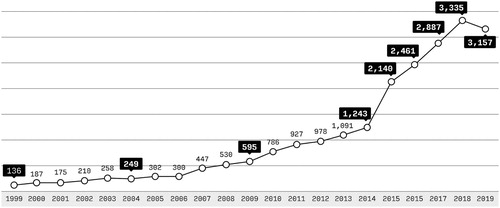

The growing interest in social innovation among policymakers and scholars has fuelled a significant increase in the number of scientific publications in the past decades (see ) which led to conceptual ambiguity and a diversity of definitions and research settings (Agostini et al., Citation2017; Ayob et al., Citation2016; Pelka & Terstriep, Citation2016; van der Have & Rubalcaba, Citation2016).

Social innovation

Social innovations are hardly new, but despite the increasing popularity of the underlying ideas among academics and policymakers the discourses on social innovation have neither led to a common definition, nor a set of standard innovation measures or streamlined policy agendas across Europe (Nicholls & Ziegler, Citation2019). Rather the term ‘social innovation’ is used to describe a broad range of individual, organizational and inter-organizational activity and practices within and across public, private and not-for-profit sector, and civil society (Cajaiba-Santana, Citation2014; Christmann, Citation2019; Domanski et al., Citation2019; Nicholls et al., Citation2015). In this regard van der Have and Rubalcaba (Citation2016) posit that the ‘scientific discourse on SI has lately had an emphasis on conceptual definitions, reflecting the lack of integration of the literature and ambiguity surrounding the scope and meaning of SI’. The authors distinguish two major research strands, i.e. the sociologically oriented conceptualizations of social innovation (cf. Cajaiba-Santana, Citation2014; Howaldt et al., Citation2015; Moulaert et al., Citation2013) and the more economic oriented conceptualizations. From a business studies perspective the latter address, inter alia, entrepreneurship (Dees, Citation2001; Dees & Anderson, Citation2006; Nicholls, Citation2006; Volkmann et al., Citation2012), social enterprise (Defourny & Nyssens, Citation2010; Doherty et al., Citation2014; Rinkinen et al., Citation2015) and/or business models (Kleverbeck et al., Citation2017; Komatsu et al., Citation2016; Yunus et al., Citation2010). Based on a bibliometric analysis on the origins of social innovation from the late 1980s to the present, Ayob et al. (Citation2016) identify two contested social innovation research streams for the first decade of the millennium. The first stream is oriented towards outcomes and value creation (‘utilitarian approach’, Ayob et al., Citation2016, p. 644). For example, Pol and Ville (Citation2009, p. 882) define as follows:

Desirable social innovation is one that in fact (‘in fact’ meaning ‘there is convincing evidence’) improves the macro-quality of life or extends life expectancy.

Social innovation is a complex process of introducing new products, processes or programs that profoundly change the basic routines, resource and authority flows, or beliefs of the social system in which the innovation occurs. Such successful social innovations have durability and broad impact.

Social innovations are innovations that are social in both their ends and their means. Specifically, we define social innovations as new ideas (products, services and models) that simultaneously meet social needs (more effectively than alternatives) and create new social relationships or collaborations. They are innovations that are not only good for society but also enhance society’s capacity to act. (BEPA, Citation2010, p. 9)

Novel combinations of ideas and distinct forms of collaboration that transcend established institutional contexts with the effect of empowering and (re)engaging vulnerable groups either in the process of social innovation or as a result of it. (Terstriep, Citation2016, p. 1)

While the diversity of conceptualizations creates ambiguity in the use of the term, it also allows for a transdisciplinary and multi-perspective view of the phenomenon which corresponds to the multi-faceted nature of social innovation (van der Have & Rubalcaba, Citation2016). Although confusing for policymakers and practitioners at times, and source of much discussion among scholars, such fluidity of meaning can also proof advantageous when it comes to the implementation of social innovation policies. This is particularly true when the variety of framework conditions in the European regions are taken into account, as are the differences in the policy areas concerned. Or in the words of Nicholls and Ziegler (Citation2019, p. 3), ‘[i]n this way, “fuzzy” social innovation can provide “clumsy solutions” to “wicked” problems’. In that sense, this special issue contains contributions that explore social innovations from different perspectives, taking into account its spatial dimension.

Accounting for the nature of social innovation as interactive, generative and contextualized phenomenon, the many practices at the micro-level of individual initiatives can add up to patterns and regularities at the macro-level facilitating institutional change. That is, social innovations addressing the institutional level aim at reconfiguring existing market structures and behavioural patterns and incremental change processes rather than radical change (Nicholls et al., Citation2015; Rehfeld & Terstriep, Citation2015). Accordingly, it can be assumed that social innovation will realize its potential contribution to inclusive growth only to the extent it can unfold its social and economic impact for the target groups and the society at large. In view of the European vision of ‘Open Innovation, Open Science, Open to the World’, applying an open approach to social innovation means making better use of the many, rather small, and locally embedded social innovation activities across Europe.

As highlighted by (Edmiston, Citation2016, p. 2),

[s]ocial innovation is often conceived as a unifying policy concept around which diverse stakeholders can coalesce and organise. The emphasis placed on ‘new’ and ‘novel’ approaches to social problems is presented as a departure from established modes of thinking and action that transcend existing political and socio-economic divisions.

It follows, that several key issues need to be addressed in order to tackle social innovation challenges within the European economic and social sphere and its policy environment. Gaining a better understanding of the components, objectives, and principles of social innovation, underlying processes and contexts as well as the apparent contradiction between the local embeddedness of social innovation and the global socio-economic challenges they address is at the core of this Special Issue.

Contents of the special issue

The special issue presents papers that focus on the gap between the untapped potential of social innovation on the one hand and global socio-economic challenges on the other hand. The common starting point is the assumption that social innovation will realize its potential to inclusive growth to the extent it can unfold its social and economic impact for the target groups and the society at large. Hence, it is important to understand that economic underpinning is not about making social innovation activities fit for market but to balance hybrid objectives (social, political and economic objectives) in a fruitful way. Moreover, in view of the European vision of ‘Open Innovation, Open Science, Open to the World’, applying an open approach to social innovation means making better use of the many, rather small, and locally embedded social innovation activities across Europe. Insofar, the contributions follow BEPA’s (Citation2014, p. 20) statement,

… that today, ecosystems for social innovation are seen as the way to create an innovation-friendly environment where social innovations can grow and to address not only the apparent cause but also the underlying problems. The shift from social innovation as a charitable solution to a problem that has an immediate but unsustainable impact (e.g. give food to the hungry) to the transformative ambition to create long-lasting changes to solve societal problems (e.g. homelessness, food disorders) that are engrained in behaviours and institutional and cultural context (laws, policies, social norms) has also been a reason to look for a ‘friendly milieu’ to organise interactions and respond to the needs of social innovations at every stage of their development. Thus, the term ‘ecosystem’ has spread within the social innovation community as a response to the different needs to structure, experiment, nurture, network, support, scale up and transfer social innovations at the different stages of their development.

Alessandro Deserti and Francesca Rizzo start their paper ‘Context-Dependency and Sustainability of Social Innovation: In Search of New Business Models’ with the observation that measures have been taken to support the flourishing of social innovations, but they have thus far been made on ideal models of development, misaligned with what occurs in reality. This has led to the creation of supporting infrastructures that fail to respond to the real needs of social innovators. Desert and Rizzo provide a picture of ‘real’ SI development process through a case-based discussion that roots in the design thinking approach. The paper presents areas of improvement and reflection, on which to develop an evidence-based model of SI development. Moreover, it connects SIs with local conditions that determine their development, suggesting that their growth and diffusion are primarily based on the adaptation to the context rather than on the scaling up mechanisms that characterize for-profits. The article concludes that this leads to the necessity for social innovators to find a difficult balance among contradictory needs, and to develop peculiar typologies of business models to make their innovations sustainable. Rehfeld, Terstriep and Kleverbeck’s ‘Favourable social innovation ecosystem(s)? – an explorative approach’ reflects on common features and differences between social innovation and other forms of innovation and the resulting requirements for a Social Innovation Ecosystem (SIES). Drawing on data from the two European research projects SIMPACT and SI-DRIVE, the article reflects on SIES from the perspective of Regional Innovation Systems (RIS) as analytical frame, strategic and management concept. It is argued that due to multiplicity of social innovation activities and their local embeddedness no best solution for SIES exists. They conclude that establishing a SIES necessitates (1) a mode of governance that integrates actors from civil society, the social, economic and academic field, (2) social innovation hubs, labs and transfer centres as intermediaries that accelerate social innovation activities and (3) the integration of different modes of innovation in transformational innovation strategies. The paper ‘Social Innovation Regime: an integrated approach to measure social innovation’ by Unceta, Luna, Castro and Wintjes contributes to advance methodologies of SI measurement and impact discourse. The argumentation builds upon the interrelation between socioeconomic contexts of SI (meso–macro levels) and intra/inter-organizational dynamics (micro level), where SIs are emerged. The authors illustrate ways in which the social economy and social organizations are connected to a broader SI Ecosystem where the socioeconomic contexts surrounding national welfare regimes are viewed as response to policy and market failures that have an impact on regional vulnerability rates. The authors argue that there is an interrelation between the strength of welfare regimes and social innovation ecosystems, at a time where social policies and welfare states all over the world are weakened or in crisis, opening the door to social innovation. The paper describes this connection through the notion of ‘social innovation regime’. This concept can be seen as a framework to explore the socio-structural factors through which a country or region presents a set of vulnerabilities which can transform into unattended social problems. Rabadjieva and Butzin consider the diffusion of social innovations. The paper ‘Social Innovations in Different Fields of Practice Compared’ takes a practice theories’ perspective. The authors suggest that social innovations diffuse through travelling elements of material, competence and meaning rather than solely through social interaction. This explains why similar social innovations, for example, urban gardening initiatives, emerge at a global scale without interaction between actors of different initiatives. The authors argue that practice fields of social innovations promote the diffusion. Practice fields are understood as bundles of similar social innovation initiatives, for example, car-sharing, urban gardening, repair cafés, etc. and facilitate the travelling of elements. Studying social innovation with a practice theories’ approach shows to be advantageous in that the focus is on activity and doing in contrast to different actors and their roles, the consideration of technology as an integral part of a practice and not as something opposed to social innovation, and the pronunciation of meaning giving credit to societal values and symbolic attributes related to social innovation.

The second group of contributions is directed towards the interconnection between local embeddedness and global dynamics. ‘Understanding the determinants of social innovation in Europe: an econometric approach’ by Akgüç aims at understanding the various determinants of social innovation incidence at the macroeconomic level across countries in Europe. Using a multivariate regression framework, the paper analyses the role of various characteristics from the ecosystem in which social innovations occur. Educational attainment, ease of doing business index, corruption index, risk preferences, cultural and social norms examples for factors that are quantified. As part of robustness checks, the paper uses three different measures of social innovation and includes country fixed effects to account for heterogeneities across countries. Avelino, Dumitru, Cipolla, Kunze and Wittmayer conceptualize the mechanisms of empowerment from a social psychology perspective. The paper ‘Translocal empowerment in transformative social innovation networks’ explores how people are empowered through both local and transnational linkages, i.e. translocal networks. Empowerment is conceptualized as the process through which actors gain the capacity to mobilize resources to achieve a goal, building on different power theories in relation to social change, combined with self-determination theory and intrinsic motivation research. Based on that conceptualization an empirical analysis of translocal networks that work with social innovation both at the global and local level is provided. A total of five networks are analysed: FEBEA, DESIS, the Global Ecovillage Network, Impact Hub and Slow Food. The embedded cases-study approach allows an exploration of how people are empowered through the transnational networking while also zooming in on the dynamics in local initiatives. The authors conclude by synthesizing conceptual and empirical insights into a characterization of the mechanisms of trans local empowerment.

The last four papers focus on the interplay between social, economic and political innovation on a local or regional level in different policy fields. ‘Applying the concept of social innovation to population-based healthcare’ by Merkel presents an integrated regional approach instead of focusing on single individuals and marks a new way of how healthcare is organized and provided. Up to date these models are rather an exception than the norm. Still, there are some successful examples. The paper focuses on population-based integrated care programmes in Germany and draws its conclusions on a case study within the German healthcare system. The author discusses the potential benefits but also limitations of population-based healthcare and explain why these approaches have not been able to achieve the impact that many stakeholders expected. Eckhardt, Kaletka and Pelka’s paper ‘Monitoring inclusive urban development alongside a human rights approach on participation opportunities’ discusses the question how monitoring and reporting efforts contribute to developing inclusive communities. The authors show that in recent years, social monitoring and reporting systems have taken up a human rights-based perspective focusing on the actual life-situation of people affected. The paper presents new monitoring and reporting approaches about life-situations and participation opportunities of people with activity limitations and disabilities in Germany alongside new standards from legislative renovations. These new modalities are analysed as innovations themselves, based on a generic context-understanding guide of social innovation. Komatsu Cipriani, Kaletka and Pelka aim at overcoming the mismatch between complex societal problems and not suitable responding structures. The paper ‘Transition through design: enabling innovation via empowered ecosystems’ discusses in how far design methods and approaches can help capacitate cities and communities and structure social innovations around larger transition visions. As social innovations are highly context-dependent, the distinctive characteristics of the local context become important to the success or failure of such initiatives. The authors explore this topic through the study of two cases in which top-down visions, negotiated at the niche-level, gave way to the structuration of an empowered ecosystem of actors, serving as a platform for iterative, social change. The cases are analysed through an ‘onion model’ in which four contexts are explored: roles, functions, structures and norms. The paper ‘Green social innovation – towards a typology’ by Schartinger, Rehfeld, Weber and Romberg addresses the questions, what particular challenges social innovations in the area of the green economy face. Based on 300 social innovation initiatives and expert workshops they elaborate a typology of social innovation initiatives that provides insights in the special challenges of social innovations in the green economy face. In order to contribute to an improved understanding of the processes of social innovation and transcend the limits of the single social innovation activity, the paper studies types of social innovations, dynamic patterns of their development and challenges specific to green social innovations.

Outlook on future research questions

The papers in this issue present different ways to study the economic underpinning of social innovation. At first sight, we see a kaleidoscope of different theoretical bases and methodological approaches, primarily case studies at micro and meso level. These are complemented by macroeconomic approaches, for example the papers of Unceo et. al and Akgüç in this issue, which are promising to understand the complexity of social innovation is a fast-growing research field, or the search and evaluation of indicators. Systemically linking these approaches could prove to be a fruitful next step towards a multi-methodological interdisciplinary.

A certain amount of heterogeneity is characteristic for a young research field like social innovation. Nevertheless, a common ground is increasingly emerging. All papers in this issue start with the assumption that there is a gap between highly engaged social innovation initiatives and their professional management. This gap should be bridged by business models that balance economic and social value propositions. Moreover, it is evident that a fitting environment such as ecosystem, innovation system, or innovation regime is needed to facilitate and strengthen social innovation initiatives. It also has become clear that for social innovation to realize its potential contribution to inclusive growth necessitates appropriate dissemination strategies. It could prove helpful to conceptualize and compare different ways of dissemination and diffusion. First ideas in this regard are outlined by Schartinger et al. (Citation2019): are market-driven dissemination by scaling, political supported dissemination through incentives or legal framing, or bottom-up dissemination combined with global networks as highlighted by Avelino et al. (Citation2019). From a theoretical perspective, more attention should be paid to organizational studies to advance understanding the underlying process of dissemination. Social innovators are highly engaged, but what happens, when in the course of scaling the activities become embedded in a formal, maybe political, maybe economic, environment? Discussing scaling needs a clear understanding of the societal aims. For example, social innovation in the different fields of the welfare regime necessitate clarifying the relationship between social innovation initiatives and the welfare system: Do they strive to compensate deficits in the welfare system? Are social innovations fields of experimentations for further privatization? Do social innovations provide a pool of ideas to rebuild the welfare system in a sustainable way? These questions are not trivial, in particular as social innovations are often small, selective, and exist in niches whereas the welfare systems aim at equally addressing all the whole society. What is the consequence when engaged social innovators decide who gets a chance to participate in societal life and who remains outside? Can we talk about social innovation when prominent figures of the ‘new digital economy’ like Bill gates avoid paying taxes but invest money in foundations because they claim to cope with societal problems in a better way than public authorities?

Finally, the debate on the economic underpinning of social innovation tackles the question of the future of division of labour between state, economy, and civil society. So far, the fuzzy character of social innovation enables a broad range of political positions to accept and promote the concept. Liberals can study social innovation as a mean of more privatization of the social infrastructure, conservative positions can use it to strengthen the idea of self-organization and a more left approach see social innovation as a tool to strengthen civil society by new modes of association or to regain public engagement in social infrastructure. Understanding these different ways to cope with social innovations needs a stronger awareness of the normative implications of social innovation. On the one hand, the requires future research on how social innovation activities become embedded in the political context. On the other hand, it has to be clarified what the normative base of social innovation research is. So far, the cases studied (also in this special issue) cover foremost socially innovative activities that are driven and promoted by actors who aim at ‘doing good’ or ‘making the world better’. In strategic terms it is promising to focus on activities like this, to study successful business models or promising modes of dissemination. The non-linearity of social innovation processes as well as accompanying conflicts, trade-offs and not intended (negative) impacts need to be considered. Coping with these situation needs to explicate the own normative background and the criteria to base decisions. Distinguishing social innovation as a strategic normative approach and social change as an analytical concept offers a way forward. Ongoing social change, only to name the renaissance of cultural nationalism in all world regions, is much broader than social innovation and it can be assumed that aspects accompanied by renationalization is opposite to all social innovation activities that had been studied so far. As long as the gap between social innovation research and social change studies remains, social innovation certainly is an interesting strategic topic to support engaged actors especially from civil society, but social innovations run danger not to be given the same priority as economic innovations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 SIMPACT – Boosting the Impact of Social Innovation (www.simpact-project.eu)through Economic Underpinnings received funding from the EU’s 7th Framework Programme under GA No. 613411.

2 Transit – Transformative Social Innovation (www.transitsocialinnovation.eu) received funding from the EU’s 7th Framework Programme under GA No. 613619.

3 SI-Drive – Social Innovation Driving Force (www.si-drive.eu) received funding from the EU’s 7th Framework Programme under GA No. 612870.

References

- Agostini, M., Vieira, L., Tondolo, R., & Tondolo, V. (2017). An overview on social innovation research: Guiding future studies. Brazilian Business Review, 14(4), 385–402. https://doi.org/10.15728/bbr.2017.14.4.2

- Avelino, F., Dumitru, A., Cipolla, C., Kunze, I. & Wittmayer, J. (2019). Translocal empowerment in transformative social innovation networks. European Planning Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1578339

- Ayob, N., Teasdale, S., & Fagan, K. (2016). How social innovation ‘came to be’: Tracing the evolution of a contested concept. Journal of Social Policy, 45(4), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1017/s004727941600009x

- BEPA. (2010). Empowering people, driving change. Social innovation in the European Union. Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union.

- BEPA. (2014). Social innovation: A decade of changes. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Bussolo, M., Dávalos, M., Peragine, V., & Sundaram, R. (2019). Toward a new social contract. Taking on distributional tensions in Europe and Central Asia. Washington, DC: The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1353-5

- Cajaiba-Santana, G. (2014). Social innovation: Moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 82, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.05.008

- Christmann, G. (2019). Introduction: Struggling with innovations. Social innovations and conflicts in urban development and planning. European Planning Studies, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1639396

- Dees, G. (2001). The meaning of social entrepreneurship. ARNOVA. https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/Article_Dees_MeaningofSocialEntrepreneurship_2001.pdf

- Dees, G., & Anderson, B. (2006). Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship. In R. Mosher-Williams (Series Ed.), Research on social entrepreneurship: Understanding and contributing to an emerging field: Vol. ARNOVA occasional paper series 1(3) (pp. 39–66). ARNOVA.

- Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2010). Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 32–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420670903442053

- Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12028

- Domanski, D., Howaldt, J., & Kaletka, C. (2019). A comprehensive concept of social innovation and its implications for the local context – on the growing importance of social innovation ecosystems and infrastructures. European Planning Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1639397

- Edmiston, D. (2016). The (A)Politics of Social Innovation Policy in Europe: Implications for Socio-structural Change and Power Relations. CRESSI Working Papers, 32/2106, 1-9.

- Howaldt, J., Kopp, R., & Schwarz, M. (2015). Social innovations as drivers of social change – exploring Tarde’s contribution to social innovation theory building. In A. Nicholls, J. Simon, & M. Gabriel (Eds.), New Frontiers in social innovation research (pp. 29–51). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Howaldt, J., Schröder, A., Kaletka, C., Rehfeld, D., & Terstriep, J. (2016). Mapping the world of social innovation: A global comparative analysis across sectors and world regions. sfs/TU Dortmund.

- IMF. (2019). Regional economic outlook. Europe: Facing spillovers from trade and manufacturing . (World Economic and Financial Surveys, Issue Fall 2019). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2019/October/English/text.ashx?la=en

- Kleverbeck, M., Terstriep, J., Deserti, A., & Rizzo, F. (2017). Social entrepreneurship: The challenge of hybridity. In A. David & I. Hamburg (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial skills in Europe (pp. 47–76). Leverkusen: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

- Komatsu, T., Deserti, A., Rizzo, F., Celi, M., & Alijani, S. (2016). Social innovation business models: Coping with antagonistic objectives and assets. In S. Alijani & C. Karyotis (Eds.), Finance and economy for society: Integrating sustainability: Vol. 11. Critical studies on corporate responsibility, governance and sustainability (pp. 315–347). Bingley: Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/s2043-905920160000011013

- Leick, B., & Lang, T. (2017). Re-thinking non-core regions: Planning strategies and practices beyond growth. European Planning Studies, 26(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1363398

- Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., & Hamdouch, A. (Eds.). (2013). The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social Learning and transdisciplinary research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Nicholls, A. (Ed.). (2006). Social entrepreneurship. New models of sustainable social change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nicholls, A., Simon, J., & Gabriel, M. (2015). Introduction: Dimensions of social innovation. In A. Nicholls, J. Simon, & M. Gabriel (Eds.), New frontiers in social innovation research (pp. 1–26). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nicholls, A., & Ziegler, R. (2019). The extended social grid model. In A. Nicholls & R. Ziegler (Eds.), Creating economic space for social innovation (pp. 3–31). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pelka, B., & Terstriep, J. (2016). Mapping social innovation maps: The state of research practice across Europe. European Public & Social Innovation Review, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.31637/epsir.16-1.1

- Phills, J., Deiglmeier, K., & Miller, D. (2008). Rediscovering social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 6(4), 34–43.

- Pol, E., & Ville, S. (2009). Social innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(6), 878–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2009.02.011

- Rehfeld, D., & Terstriep, J. (2015). Middle-range theorising: Bridging micro- and meso-level of social innovation (SIMPACT Working paper: Vol. 2015(1)). Gesenkirchen: Institute for Work and Technology.

- Rinkinen, S., Oikarinen, T., & Melkas, H. (2015). Social enterprises in regional innovation systems: A review of Finnish regional strategies. European Planning Studies, 24(4), 723–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1108394

- Schartinger, D., Rehfeld, D., Weber, M., & Rhomberg, W. (2019). Green social innovation - towards a typology. European Planning Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1677564

- Terstriep, J. (Ed.). (2016). Boosting SI's social and economic impact. Gesenkirchen: Institute for Work and Technology.

- van der Have, R., & Rubalcaba, L. (2016). Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Research Policy, 45(9), 1923–1935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.06.010

- Volkmann, C., Tokarski, K., & Ernst, K. (2012). Background, characteristics and context of social entrepreneurship. In C. Volkmann & K. Tokarski (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship and social business (pp. 3–30). Berlin: Springer Gabler.

- Von Jacobi, N., Edmiston, D., & Ziegler, R. (2017). Tackling marginalisation through social innovation? Examining the EU social innovation policy agenda from a capabilities perspective. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2016.1256277

- Westley, F., & Antadze, N. (2010). Making a difference: Strategies for scaling social innovation for greater impact. The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 15(2), 1–19.

- Yunus, M., Moingeon, B., & Lehmann-Ortega, L. (2010). Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen experience. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 308–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.12.005