ABSTRACT

Citizen dialogues and other participatory practices are basically the norm in contemporary spatial planning. Nonetheless, what happens to citizen input after it has been collected – how it is handled and utilized by planners in the continuation of the planning process – has been described as a ‘black box’, where most stakeholders lack insight. The aim of this explorative study is to open this black box and examine how citizen input is handled by local planning professionals. This practice lacks a common language and form among the studied municipalities, but the analysis reveals that it takes the form of a ‘sorting process’ in which input is categorized, evaluated and structured in preparation for its integration into final plans. The paper outlines the basic logics and considerations that guide this sorting process, and distinguishes between two modes, which have been termed ‘inclusive’ and ‘selective’ sorting. These modes determine how input is categorized and assessed. The analysis indicates that multiple micro-decisions are made throughout the sorting process, and that these decisions influence the input that reaches formal decision-making bodies, and in what form. The results reveal the power exercised by municipal planning actors and how they affect the destiny of the received citizen input.

Introduction

In conventional post-war planning theory, the ideal planner was understood as an objective, rational expert, expected to produce a spatial plan of the highest quality, in the interests of the public. This functionalist conception was challenged in the 1960s (Huxley and Yiftachel Citation2000), and with the ‘communicative turn’ in planning theory (Healy Citation1997, 28) citizens have been increasingly perceived as carriers of experiences important to the planning process.

Within a participatory and collaborative planning tradition, access to various kinds of knowledge – grounded in different values, experiences and expertise – is formulated as vital for successful planning (Smedby and Neij Citation2013, 148). According to this view, new ideas and solutions emerge when the different perspectives meet (Healy Citation2002), which renders the public system more flexible, adaptive and intelligent (Connick and Innes Citation2003). To achieve this, planning is formulated as a process in which politicians, planners, citizens and experts are all actively involved (Healy Citation1997; Fung Citation2006), exemplified by the argument put forward by Smedby and Neij (Citation2013, 149) that the role of the planner has been transformed to that of a ‘facilitator’.

However, as participation has become the norm, the participatory ideal and practices have been scrutinized (e.g. Flyvbjerg Citation2004; Sager Citation2009; Inch Citation2015). Institutionalized participatory practices have been criticized for lacking transparency (Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005) and failing to allow citizens substantial influence (Amnå Citation2006; Monno and Khakee Citation2012; Tahvilzadeh Citation2015). Moreover, the interests of disadvantaged groups have been hard to accommodate within participatory planning (White Citation1996; Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009), while more powerful actors, especially business interests, have often been given disproportionate influence (Swyngedouw Citation2005; Inch Citation2015). This has led some scholars to question the entire concept of public participation (see Parvin Citation2018) and to point out that if participatory planning is to be legitimate, citizens must have a real potential to influence the outcome (White Citation1996; Monno and Khakee Citation2012). This article continues the critical empirical investigation of participatory planning processes by illuminating how citizen input is handled by planners (cf. Healy Citation1997; Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005).

Aim and research questions

This article has its origins in a broader study in which we have followed local authorities’ initiatives to involve citizens in planning processes (see below). The initiatives included a variety of participatory methods and stressed the importance of ‘taking good care’ of the opinions received. Gradually, however, we realized that the planners involved had a hard time explaining how the input was handled once gathered. Vagueness in this aspect of the participatory process has been observed before. Bickerstaff and Walker (Citation2005) argue that the way in which planning agencies handle citizen input is diffuse to most stakeholders, and Healy (Citation1997) has described this aspect of the participatory planning process as ‘an impenetrable “black box” of “taken-for-granted” knowledge’ (275). The aim of this article is to open this black box and examine how citizen input is handled by planners. We seek in this way to increase knowledge of the processes that determine citizens’ potential to influence planning outcomes (cf. Fung Citation2006; Monno and Khakee Citation2012), and to clarify how the diverse input received is transformed by the planners into a format that can be utilized (cf. Demszky and Nassehi Citation2012). The study increases our understanding of how power is exercised by planners (cf. White Citation1996; Flyvbjerg Citation2004; Tahvilzadeh Citation2015), and takes a first step towards unravelling the processes that lead to some interests being accommodated while others are rejected (cf. Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009; Monno and Khakee Citation2012; Nguyen Long, Foster, and Arnold Citation2019).

More precisely, we focus on how planners sort among the input that citizens bring to the planning process. In other words, we are interested in how citizen input is categorized, evaluated and structured, as it is prepared for integration into formal decision-making and final plans. Three explorative questions guided the study:

(1). How is the sorting of citizen input perceived and described by our interviewees?

(2). How is the sorting process performed, and what are its characteristic features?

(3). By what logics is citizens’ input sorted, and which considerations appear to be important to the sorting process?

Background

The ideal of public participation permeates the contemporary policy discourse in western societies and affects policy-making processes within all branches of public administration (Cornwall Citation2008), including planning (Healy Citation2002, 108). The motivation for involving citizens stems from a mix of ideologies (Cornwall Citation2008; Tahvilzadeh Citation2015), ranging from human rights movements pushing for power sharing and equality, to neoliberal management ideals seeking to create active and accountable citizens. Even if the motives differ, most actors seem to agree that participation is desirable. Within academia, participatory practices have been promoted (e.g. Healy Citation1997; Forester Citation1999) as well as critically investigated (e.g. Monno and Khakee Citation2012; Inch Citation2015), and political theorists have scrutinized how these deliberative models relate to – and perhaps conflict with – representative democracy (e.g. Amnå Citation2006; Vestbro Citation2012; Parvin Citation2018).

In spatial planning, attention to public involvement has increased since Arnstein’s (Citation1969) seminal work, through participatory (Smith Citation1973) and collaborative (Healy Citation1997) planning theory, to become a widely acknowledged imperative among theorists and professionals (Healy Citation2002, 108; Tahvilzadeh Citation2015, 240). Participation in planning is enforced by legislation in several countries (one of them being Sweden), and is commonly framed as a way of improving democracy through deliberative logics (Forester Citation1999; Amnå Citation2006). Public participation is often presented as characteristic of modern planning, in contrast to historical approaches, which had a more top-down nature. This has been contested by scholars who argue that some form of public participation has always been a part of planning practices (Thorpe Citation2017). Rather, what might be characteristic of contemporary planning is that citizen participation has become institutionalized (Monno and Khakee Citation2012, 86). Today, participation is routine, implemented through structured methods as part of the authorities’ organizational logic. This can be interpreted as a step towards democratizing planning, improving government efficacy and empowering local communities (Fung Citation2006; Smedby and Neij Citation2013). However, such institutionalization within the context of new public management might also prove to be problematic, as the theoretical values of participatory planning differ vastly from the neoliberal interest for public participation (Sager Citation2009). When participatory practices become institutionalized, there is a risk that they become tokenistic, serving to legitimize the authority, while failing to allow substantial influence (Amnå Citation2006; Monno and Khakee Citation2012). Moreover, the participatory turn in the neoliberal paradigm risks ‘depoliticizing’ planning, as inherently ideological issues become perceived as administrative matters (White Citation1996; Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2012).

Typically, participatory practices do not reach the point at which power is shared with citizens (Tahvilzadeh Citation2015, 244; cf. Arnstein Citation1969). Rather, the decisive power stays with professionals, politicians or other more powerful actors (Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005; Vestbro Citation2012). Power is indeed an important theoretical instrument to understand participatory planning practices (Flyvbjerg Citation2004).Footnote1 Not only are there differences in power positions between citizens, planners and politicians, but market logics also infuses many planning projects, giving corporate actors considerable power to influence the processes (Swyngedouw Citation2005; Andersen and Pløger Citation2007; Inch Citation2015). Concerning power, the issue of who participates is crucial (Fung Citation2006; Cornwall Citation2008), and research shows that groups of disadvantaged citizens are often absent (White Citation1996; Parvin Citation2018) or actively excluded (Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009; Monno and Khakee Citation2012, 93).

Another important matter concerns how participative interactions are structured (White Citation1996, 12; Fung Citation2006). Many scholars have explored this input side of participatory planning, and they have emphasized the importance of sound methods (e.g. Healy Citation1997; Forester Citation1999), and of new and innovative forms of participation (Nyseth, Ringholm, and Agger Citation2019). Public participation in planning can take place in several formats. These include dialogue meetings, opinion surveys, panels, consultations, various forms of diary or report kept by users or citizens, art interventions, open labs and mental mapping (Nyseth, Ringholm, and Agger Citation2019, 8; Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005; Olausson and Syssner Citation2018). The minimum format for citizen involvement takes the form of mandatory consultations prescribed by legislation (Monno and Khakee Citation2012). Even if dialogue meetings can be fruitful for obtaining public opinions, the desire to reach ‘consensus’ that is a characteristic of contemporary policy-making (Mouffe Citation2002) can limit expressions of conflicting opinions, conceal power imbalances and maintain the status quo (White Citation1996; Bond Citation2011; Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2012). Thus, it is important that the organizer of dialogues is able to evoke and handle conflicting interests (Forester Citation1999). Basic digital tools such as e-mail and online questionnaires have been used for a considerable period, but in recent years more advanced digital tools – such as interactive maps and smart watches – have been introduced in the participatory processes (Nyseth, Ringholm, and Agger Citation2019; Wilson, Tewdwr-Jones, and Comber Citation2019). Such tools can simplify participation and facilitate more detailed input (Wilson, Tewdwr-Jones, and Comber Citation2019), but are associated with difficulties concerning accessibility and a loss of dialogue and communality (Hofmann, Münster, and Noennig Citation2020, 5).

An important part of assessing participatory processes concerns the output side: how does public input affect the final plans and projecting process (Fung Citation2006; Faehnle and Tyrväinen Citation2013; Nyseth, Ringholm, and Agger Citation2019). If there is no potential to influence the outcome, participatory practices risk to become a waste of time and money, manipulation or tokenistic manoeuvres (Tahvilzadeh Citation2015; Cornwall Citation2008). Regardless of the good intentions of planners who try to create meaningful participation, substantial influence on outcome is often scarce (e.g. Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2132; Monno and Khakee Citation2012). Further, if citizens do not feel that their contribution matters, this can create distrust and reduce the willingness to participate (Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005). When and why citizens are able to influence outcome depends on several interlinked circumstances. Part of the explanation might lie in the structure of the participatory activities (Fung Citation2006; Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009) and the ‘quality of the communicative and collaborative dynamics’ (Healy Citation2002, 112). Intra-organizational capacity for change might be another factor (Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005), while issues of power also play a significant role (White Citation1996; Flyvbjerg Citation2004; Bond Citation2011). For instance, Eriksson (Citation2015, 185) highlights how government officials can use their power position to both enable and hamper influence, while Nguyen Long, Foster, and Arnold (Citation2019) show that when public opinion is powerful enough, citizens can indeed influence the planning outcome in fundamental ways.

One crucial aspect of participatory planning processes that have largely escaped inquiry concerns how planners handle the input from citizens (Healy Citation1997, 275; Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005; Åström and Brorström Citation2011). Demszky and Nassehi (Citation2012) have shown that experiential knowledge expressed by citizens typically cannot be utilized in the political sphere in its original form. Rather, it needs to be systematized and abstracted by officials – a process that Demszky and Nassehi describe as a form of ‘translation from practices to texts and a reduction of the inconvenient complexity of experience based knowledges’ (Demszky and Nassehi (Citation2012), 176; cf. Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2132). This translation can be understood as a form of preparation, where the disparate inputs from the dialogues are transformed into a coherent and accessible format (Demszky and Nassehi Citation2012).

Material and methods

This study has been conducted within the framework of Coast4Us – an Interreg-funded international planning initiative that involves local partners in four countries around the Baltic Sea. Departing from an ‘holistic and inclusive approach’, one ambition of Coast4Us was to develop methods that improve participation in coastal area planning. The task of Linköping University, where the authors are based, in Coast4Us has been to examine the participatory processes among the Swedish municipal partners.

The planning context

In Sweden, municipalities carry the responsibility for all planning within their territory (Law Citation2010:900), and every municipality must adopt a revised Comprehensive Plan (Översiktsplan, in Swedish) during each term of office. The Comprehensive Plan is not legally binding but is indicative, and points out the main direction for the planning in the municipality. A Detail Plan (Detaljplan, in Swedish), in contrast, is legally binding, and regulates how the physical environment is to be changed or preserved within a limited area. The planning processes investigated involved the development of both Comprehensive Plans and Detailed Plans.

Six municipal planning authorities were included in the study. The municipalities consisted of five smaller towns (between 5000 and 28,000 inhabitants) and one mid-sized city (approximately 150,000 inhabitants) where the planned area was in a remote part of the municipality. Thus – while not distinctly rural – the planning context can be characterized as non-urban, and, in contrast to the situation in many urban planning projects (see e.g. Andersen and Pløger Citation2007), investor/business interests in the planning processes were low. Sometimes local community groups were engaged, but all planning processes investigated were initiated and run by the municipal authorities. The intended developments described by the plans included new pedestrian and bicycle paths, public buildings such as preschools and schools, parks and recreational areas and residential areas. To summarize, the planning processes under study typically concerned comparatively small-scale planning of public spaces in a small-town context where the municipal authority was the dominant planning actor.

The contemporary Swedish planning framework promotes that citizens and other stakeholders should have a say in the planning process – an ideal that has evoked a variety of partnerships and involvement practices (Syssner Citation2006; Normann and Vasström Citation2012, 941; Åström and Brorström Citation2011). Consequently, planners in all the municipalities had experience of working with collaborative planning, and they mainly used traditional (face-to-face) methods, such as drop-in workshops, citizen dialogues, exhibitions and public consultation meetings. Sometimes these methods were complemented with digital forms, such as the opportunity to submit input via e-mail or web-based questionnaires. Thus, the citizen input handled came from a variety of sources: oral or scribbled comments from physical meetings, answers to questionnaires, written responses to formal consultations and spontaneous input by telephone or e-mail. Some input was digital, but no advanced digital tools were used (cf. Nyseth, Ringholm, and Agger Citation2019; Wilson, Tewdwr-Jones, and Comber Citation2019).

Empirical material

The aim of the study was to examine how planners handle citizen input and some form of sorting process occurred at all the planning authorities. To investigate these processes, we used empirical material that primarily consisted of interviews with municipal officials. The interviews were semi-structured and followed certain topics, but with opportunity for the interviewees to elaborate on their perspectives. Six interviews, each of duration about 60 min, were conducted with individuals. One interview was conducted with a group of two participants, and one with a group of four participants. These interviews were of duration about 120 min. Twelve individuals from the six municipal planning authorities were thus interviewed, in eight interview sessions. Officials from the three Swedish Coast4Us municipal partners were included, all situated in the county of Östergötland, in south-eastern Sweden. Officials from an additional three municipal planning authorities in the same county were included, to obtain a broader material. The criterion for selection as interviewee was employment as an official engaged in the municipal planning processes. Six interviewees were planners by occupation, three had been employed as development officers and three as managers. In the text, interviewees hired as planners or developers (and not as managers) are referred to as ‘planners’.

To gain insight into how the procedure of sorting occurs, observations were made at three meetings in which municipal actors met to discuss the input provided by citizens in citizen dialogues. As the focus in these post-dialogue meetings was to judge how to respond to the citizen input, we have called them ‘sorting meetings’. Thus, ‘sorting meeting’ is a term coined by us, following the analysis, rather than one used in practice. The empirical material, in which all individuals have been anonymized, is summarized below ().

Table 1. Empirical material, overview.

Analytical process

We began the investigation by observing a municipal post-dialogue meeting. This initial observation enabled us to outline five broad themes that appeared to be significant to the sorting process: degree of formality; structure; time; conflict/consensus; and professional/political assessment. These themes were used as a starting point in the following interviews and observations, while we were careful to remain open to new aspects arising. When the entire material had been gathered, a qualitative analysis was conducted, taking its departure in research questions one and two. We searched for recurring patterns in the material, refined the five initial themes and added two new themes that concerned the logics and considerations of sorting, allowing us to formulate and answer the third research question. Since our ambition was to conceptualize a rather unexplored phenomenon, we emphasized the common denominators of the sorting processes in the six planning authorities. We do, however, highlight some significant differences. Before finalizing the analysis, we validated it by presenting preliminary results to some of the interviewees and other planners at two workshops. The workshops largely confirmed our analysis, and resulted in only minor adjustments.

Results and analysis

The role of the planner has been transformed in the collaborative era (Smedby and Neij Citation2013), but planners continue to occupy a key position in the planning process (Monno and Khakee Citation2012). More voices are heard, and a variety of knowledges are considered, but when the participatory activities have been completed, the planners are usually left with voluminous input that they must handle based on professional judgment. This practice often requires trade-offs between incommensurable choices (Sager Citation2009; Åström and Brorström Citation2011). In the words of Bickerstaff and Walker (Citation2005, 2132), the process ‘require[s] the planners to sort through and prioritise an “argumentative jumble” of inputs based on diverse systems of knowledge, value and meaning’ (emphasis added). We illuminate this sorting process below, and begin by depicting how the sorting of citizen input is perceived and described (research question one), and exploring how this practice can be understood as a process of translation. This is followed by an elaboration of research questions two and three, concerning the structure and characteristic features of the sorting process, and the logics and considerations that affect the sorting.

Different understandings of the concept of ‘sorting’

What we refer to as ‘sorting’ citizen input was termed differently and inconsistently by the interviewees. Sorting was, indeed, a common term used, as were ‘weighing’ and ‘sifting’. ‘Grouping’ and ‘categorizing’ were other occurring terms. In a broad sense, these words describe similar processes that involve the handling of input from participatory activities. Even so, the processes took quite different forms in the planning authorities. When speaking of sorting (or weighing, sifting, etc.), some interviewees referred to a structured practice that involved several officials, while others referred to something that a single planner conducted intuitively. Seemingly, this aspect of the participatory planning has not been institutionalized by a common language or procedures shared across organizational borders. Nonetheless, most participants acknowledged that some kind of sorting process takes place, and recognized that this practice contains dimensions of ‘subjective judgement’ (Interviews 1, 2, 7, 6, 8; cf. Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2132). However, one interviewee maintained that the officials did not sort citizen input in any way, arguing that it was important to present unprocessed input to the politicians on which they could base their decisions. This interviewee stated that the planners merely ‘structured the input, highlighting what’s relevant’ (Interview 5). This statement suggests that a sorting process, as we define it, takes place also in this municipality, while not being recognized as such.

Different sorting at different stages

The interviewees emphasized that sorting takes different forms at different stages of the planning process. Thus, we must consider the aspect of temporality when seeking to understand sorting practices. In short, the earlier the involvement, the greater was the perceived need for sorting. The purpose of early-stage citizen dialogues was typically to obtain a broad variety of perspectives that could be incorporated into Comprehensive Plans. Here, the participating citizens are typically asked to provide whatever visions they have, which results in an extensive need to sort the broad and dissimilar views that are received. In contrast, from the (mandatory) consultations that take place during the late part of the planning process – when a proposal for a Detailed Plan is in place – the sorting process was perceived as more limited. Here, fewer individuals leave comments, and the scope of the comments is narrower, since they are constrained by the content of the planning proposal. Hence, there is less input to sort and the input ‘sorts itself’, to some extent, in relation to the plan. While sorting takes place also at this stage, the input from consultations can to a greater extent be documented ‘as they are’, and left for the politicians to base their decisions on. In latter stage consultations, legislation is also perceived as regulating the sorting process to a greater extent, by determining which kinds of input can be considered.Footnote2

However, the amount of sorting perceived to be necessary after early-stage dialogues also differed, and the sorting process could be preceded if planners organized dialogues by predetermined themes. This way planners could, to a certain extent, control the content and amount of input that the dialogue gave. For instance, if each participant is asked to give three examples of something they experience as positive and one example of something negative (as was the case in the dialogue process described in Interview 4), the numbers of ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ answers will be predetermined, as will also the categories ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. When planners control input this way, it reduces the need for sorting. The administrative power of the planners (cf. Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005) is thus exercised through the preparations before, and practices during, the dialogues, rather than solely through the subsequent sorting process.

Sorting as an ongoing process of translation

Several interviewees described ‘workshops’ as a common method of arranging participation. These contained elements of dialogue, and aspects of co-production, such as citizens making additions to maps to visualize their opinions. Such input must be interpreted by the planners. Demszky and Nassehi (Citation2012) have pointed out that officials handling of citizen input can be seen as a process of ‘translation’, where disparate input expressed in everyday language is transformed into an ordered format that is functional within the planning authority. As one of the interviewees put it: ‘The planners convert citizens’ comments into something more creative and cohesive’ (Interview 6). Such translation occurs in many ways, for instance when sketches on maps are transformed into written text, or when comments scribbled on Post-it notes are formatted to be integrated into dialogue reports. Other vital aspects of translation occur when the input is categorized, structured and evaluated such that it can be incorporated into final plans. Thus, the sorting processes we investigate involves a significant element of translation.

In advance, we had envisioned the sorting of input as something that takes place at a specific moment after a citizen dialogue. However, our results show that sorting – and the translation it involves – is an ongoing process. The sorting begins during the citizen dialogues, when verbal comments are summarized, and does not take place solely at a single sorting meeting, when a written report of the input already exists. Moreover, a planning process typically contains several occasions on which planners interact with citizens, making recurring sorting necessary.

Characteristics of the sorting process

Three dimensions stand out as significant in understanding the sorting process: (a) degree of formality, (b) amount of conflict and (c) professional and political assessment. These dimensions are described as dichotomies (formalized – non-formal, conflict – consensus, professional – political), but should not be interpreted as counterpoints. The categories indeed contradict in some cases, while in others they overlap. For instance, a specific sorting process can contain aspects of both conflict and consensus.

Degree of formality

The sorting processes differed in the degree of formality between the municipal planning authorities. Some planners could readily give a consistent account of the process and described a well-established procedure. We have termed such sorting processes ‘formalized’, as they are characterized by regularity, predictability and structure. Formalized processes typically followed a systematic sequence with a clear division of responsibilities between actors. Carl, a planner in one of the municipalities (Interview 7), describes its sorting process as consisting of three distinctive ‘steps’. In step one, he alone makes a rough assessment of which parts of the input are relevant to the specific planning process. Such ‘rough sorting’ occurs in some form in all investigated authorities. In step two, the feasibility of the remaining suggestions is evaluated, while in step three vested interests are weighed against the public interest and legislation. Interviewees from other municipalities described similar practices (e.g. Interview 3), in which an early ‘rough sorting’ conducted by a single planner is followed by latter steps, usually conducted collectively through sorting meetings.

Other planners described the sorting process as less systematic, lacking a predetermined structure. In such ‘non-formal’ sorting processes, the responsible planner plays a more significant role in managing and determining the process. Sorting meetings occur also in non-formal sorting processes, but are organized spontaneously, and only if the planner perceives a need. The division of labour is also more fluid, where ‘colleagues from the corridors’ might be called in to give advice (Interview 1). Thus, the non-formal sorting process relies more on the internalized professional judgement of the planner in charge (cf. Monno and Khakee Citation2012). Such sorting processes imply a more intuitive approach and do not follow a single structure.

A non-formal sorting process is not necessarily negative. However, if sorting processes are performed without due consideration, there is a risk that unconscious biases affect them. Further, such sorting processes may lack transparency. In our material, some of the planning authorities used non-formal sorting process simply because they had not considered formalizing them. Rather, sorting was understood as something done by the planners ‘as it always has been done’ (Interviews 1, 2). However, in at least one case (Interview 5), a conscious decision seemed to have been made to apply non-formal sorting processes. Here, it was stressed that the sorting of input is a task for politicians, and that there should be no formalized structure for sorting before the formal political decision-making.

The above division into formalized and non-formal sorting processes is ideal-typical, and even highly formalized sorting processes contain aspects of informality. For example, the ‘rough sorting’ typically made in the first step of formalized processes requires professional judgments that are not codified (cf. Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2132). Generally, the sorting process described by the interviewees tended to be non-formal rather than highly formalized.

Amount of conflict

An important aspect of leading participatory processes is to evoke and handle competing perspectives and interests (Forester Citation1999) and ‘conflict’ can be a vital and constructive aspect of participatory practices (White Citation1996; Bond Citation2011). Nonetheless, even if the citizen input in some cases conflicted internally, the sorting processes described by the interviewees were considerably consensus-oriented.

Obviously, conflicts are not likely to arise within planning authorities in which the responsibility for the sorting process essentially rests on a single planner. However, in processes in which several individuals are involved, conflicts over how to sort the input are more likely to arise. Even so, during the three sorting meetings we observed, the participating officials seemed eager to reach consensus. The planner responsible for the meeting was usually quite dominant during the meeting and presented their assessment as a starting point. The other participants rarely contradicted this. Certain input was occasionally discussed from different perspectives, but this never evoked outright controversy. Nonetheless, it is possible that this broad expression of consensus sometimes reflected conformability and/or exercise of power, rather than genuine consensus (cf. Bond Citation2011; Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2012). Instead of communicating verbally, some actors nodded in agreement, snorted or expressed muffled laughter when certain citizen input was presented (Observation 2). If these actors were influential actors, they guided the others on the proper way to understand the issue. Moreover, at one of the observed meetings (Observation 1), when the participants could not agree on how to respond to a certain input, consensus was achieved by agreeing that the issues should be forwarded to an expert department, relieving the meeting of the pressure to reach a final verdict.

Professional and political assessment

The sorting processes investigated included a combination of professional and political assessments. The interviewees described the sorting processes as being managed by officials rather than by politicians, while formal political decisions were perceived as taking place after – or as the conclusion of – the sorting process, when the finalized planning proposals are approved by the municipal board. In general, professional assessment was perceived to be more important at earlier stages of the sorting process. Nonetheless, politicians influenced the assessment in several ways. The interviewees were typically trying to create a final planning proposal that would be accepted by the political decision-makers. Hence, they tried to adapt the sorting to the assumed preferences of the political leadership (Interviews 4, 5). This is an indirect political influence on the sorting process. Politicians were, however, also involved more directly. If the planners were uncertain whether their proposals would be accepted, they sometimes consulted politicians during the sorting process. Moreover, sometimes politicians participated in the formalized sorting meetings (Observation 3). Below, we show that the sorting process contains a considerable number of micro-decisions – in the shape of valuations and judgements – made before the formal political decision-making, which affect whether citizen input is integrated into planning proposals and, if so, how.

The logics and considerations of sorting – what goes in which pile?

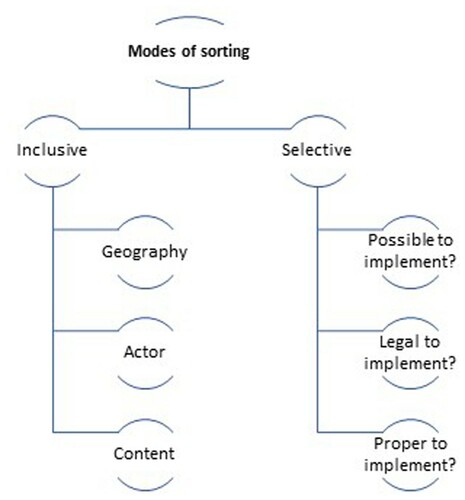

When spoken and written citizen input is translated into official texts, the exact formulations are altered – simplified or elaborated – and the result differs from the original wording. Some aspects of the input will inevitably be lost in this translation, either by deliberate alteration or as a result of misinterpretation or failure to comprehend the input (Demszky and Nassehi Citation2012; Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005). However, the aspect of translation we focus on here is the active judgements planners make when handling the input. The sorting processes always involved making judgements on how to categorize and assess the input, commonly manifested by organizing it into different ‘piles’. Sorting is carried out in relation to several considerations at the same time, and thus certain input can belong to several piles. We describe below the logics and considerations that guide this practice, and show that the sorting process can be divided into two distinct modes: inclusive sorting and selective sorting. Both modes involve making value judgements, but the implications of these judgements are more significant in the selective mode since the selection that occurs in this mode requires some input to be rejected.

Inclusive sorting

The characteristic feature of what we term ‘inclusive sorting’ is that no input is deselected. In this mode, all input is kept ‘on the table’, and the sorting consists of organizing and systematizing it. Thus, inclusive sorting is a form of thematical categorization of input, following several logics. For instance, input might be sorted ‘geographically’, either according to the geographical area that the input concerned (e.g. the camping site or the town square) or according to the geographical area from which the input was received (e.g. where the individual who expressed the opinion lived) (Interviews 2, 3, 4, 5, 7; Observation 2). A second logic used during inclusive sorting was to categorize input according to the type of ‘actor’ who had expressed it. For instance, young and elderly people may be sorted into different piles or permanent residents could be separated from summer residents (Interviews 3, 4). Inclusive sorting was often also structured by ‘content’, where similar input was grouped according to topic (Interviews 3, 4). For instance, input concerning ‘traffic’, ‘safety’, ‘green areas’ or ‘sustainability’ could be placed into separate piles. Sometimes such categorizations are straightforward. Sometimes, however, content-based sorting required considerable interpretation, especially if abstract themes are used. This revealed the more subtle aspects of translation in the sorting process. For instance, determining whether a comment on streetlights concerns traffic or safety – or both – is a matter of interpretation.

Inclusive sorting can differentiate between the interests of different actors, determine which geographical areas need attention and identify which issues are most important to the public. Inclusive sorting enables planners to analyse the input while taking different perspectives and themes into consideration. Thus, the planners translate – i.e. systematize and restructure – the input (cf. Demszky and Nassehi Citation2012). The aspects of the input that are highlighted in the final documentation will depend on the final structure of the sorted input. Even if all input is ‘still there’, the presentation will determine how it is perceived (cf. Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2132). For instance, if the input is categorized according to who gave it, summer residents or permanent residents, any differences of age or gender might be concealed. The ways of categorizing input are basically infinite, which means that it is vital for planners to consider carefully the logics that guide the inclusive mode of sorting.

Selective sorting

The realities of planning typically mean that all interests cannot be met simultaneously, and planners must make trade-offs (Åström and Brorström Citation2011, 13). Oliviera e Costa and Tunström (Citation2018, 7) concluded from a study on citizen involvement in 12 Swedish municipalities that ‘the planners are responsive to the viewpoints (of the public), but they reserve the right to determine which opinions can be accommodated in the elaboration of the plan’ (our translation). The second mode of sorting concerns this issue, and we have defined ‘selective sorting’ as sorting during which input is assessed as being suitable to be adopted into, or rejected from, the planning proposal. The final selective sorting is made by politicians during the formal decision-making on the planning proposal. Our point, however, is that many micro-decisions are made at earlier stages, through selective sorting during the planning process, when officials prepare plans and formulate decision proposals.

A first, basic form of selective sorting occurs during the ‘rough sorting’ at an early stage of the sorting process. Here, planners assess whether the input concerns the current planning process. For instance, markers located on a map outside the geographical area that the plan concerns can be deselected. It was also commonly stated that input ‘that is not a planning issue’ was deselected (Interviews 1, 3, 5, 8; Observations 1, 2). Examples given were replacing a defective waste bin and repairing streetlights. Such issues – deemed to be ‘maintenance’ – were typically forwarded to another division (e.g. the Streets and Parks Department). After assessing whether input concerns the current planning process, three broad considerations guided the selective mode of sorting: assessments of whether a proposal made by certain input is (1) possible, (2) legal and (3) proper to implement.

A recurring issue in the interviews and observations alike concerned estimations of what was considered ‘possible’ or ‘realistic’. A citizen suggestion might be deemed beneficial, but still not ‘possible to implement’, based on an economical, technical or practical judgement. Such considerations affect both short-term measures – such as to build at a specific site – and long-term measures – such as to subsequently manage and maintain the building (Interview 5; Observations 1, 3). It might be deemed possible to turn a disused building into a youth centre but not possible to staff and run a youth centre. Assessments of what is possible are sometimes based on physical realities, such as whether it is technically possible to erect a building given a specific land structure. However, what is deemed to be possible in economical and practical terms is also a matter of judgement, and this depends on how much money and effort the municipality is willing to invest (cf. Faehnle and Tyrväinen Citation2013, 36; Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2136).

The second consideration made during selective sorting concerned what is ‘legal to implement’. Many national laws and regulations govern how a spatial area may be planned, and the interviewees stressed that they assessed whether citizen input violated, for example, regulations concerning shoreline or nature protection, or whether it conflicted with national infrastructure projects (Interviews 5, 7, 8; Observation 3). They pointed out that this aspect of sorting is also heavily influenced by the Swedish County Administrative Board (SCAB; Länsstyrelsen in Swedish); the state agency that reviews the final planning proposal. The planners tried to deselect input that conflicted with national legislation and often consulted the SCAB before the formal review (Interviews 3, 5, 7; Observation 3). Sorting according to legal considerations is affected also by property law, which differs between privately and publicly owned areas (Interview 7). It might initially appear that it is straightforward to sort input according to whether it is legal to implement the proposals. However, it is not always apparent how the law should be interpreted, and planners sometimes need to consider a web of different regulations and determine which have precedence. Thus, this mode of sorting also involves assessments that are based on professional expertise and discretion.

The third consideration of selective sorting concerns ‘properness’. A suggestion might be both possible and legal to implement, but still deemed not ‘proper to implement’. Here, planners consider the input based on their professional knowledge and existing political intentions. To a great extent, this assessment concerns weighing ‘vested interests’ – as expressed by individuals or specific groups of citizens – against the general ‘public interest’ (Interviews 7, 8). The Planning and Building Act (Law Citation2010:900) and its preparatory work (2009/10: 170, 160) state that there should be ‘a reasonable balance’ between the benefits and negative consequences when weighing vested interests against the public interest. This formulation is open for interpretation, and several planners stated that it is a difficult and complex task to predict all the potential negative and positive consequences of implementing a certain citizen suggestion (Interviews 5, 7). Further, even if the citizen dialogues were understood as a way to determine the public interest, our interviewees pointed out that it was a problem that some groups of citizens are hard to reach, and if not all groups are represented, the dialogues risk becoming expressions of vested interests (Interviews 2, 3, 5, 6, 8; cf. White Citation1996; Swyngedouw Citation2005; Parvin Citation2018). Moreover, the way in which political ideologies and market interests override both the planners’ knowledge and the public interest has been criticized (Vestbro Citation2012; Sager Citation2009; Inch Citation2015). Conclusively, planners must be critically aware of what voices are heard and what interests are given precedence when considering what is proper to implement.

Summarizing the logics and considerations of sorting

shows the logics and considerations that guide the sorting process.

This model is descriptive in the sense that it summarizes our findings, rather than visualizing all possible alternatives. For example, while geographic, actor-oriented and content-oriented logics were significant in our study, other logics of inclusive sorting are possible. We have also depicted the considerations of the selective sorting separately. Such ideal types are useful when constructing theoretical typologies of real-life events. However, these considerations often merge in practice. For instance, the weighing of vested interest against the public interest – categorized here as a consideration of what is proper to implement – is also subject to legal provisions, and thus what is proper blends with what is legal to implement. It is important to note that some interviewees stated that the ‘strength’ of public opinion affected the sorting process (Interviews 5, 7, 8). If many citizens expressed the same opinion strongly, it was more likely to have an influence than a few scattered comments (cf. Nguyen Long, Foster, and Arnold Citation2019).

Summary

We have examined how proposals and opinions from citizens are handled as a form of input when considering how spatial plans are to be formulated. This handling takes the form of a ‘sorting process’ that can be understood in terms of translation (cf. Demszky and Nassehi Citation2012). This sorting, however, lacks a common language among the planning authorities. Rather than taking place at a specific instance, the practice of sorting is continuous, and changes its nature during the planning process. The processes are consensus-oriented, differ in the degree of formality, and comprise a mixture of professional and political assessments.

The basic logics and considerations that guide the sorting process have been outlined and divided into two separate modes – inclusive and selective sorting – that determine how input is categorized and assessed. The sorting process includes multiple micro-decisions that affect which input reaches the formal decision-making bodies, and in what form. These micro-decisions are made individually or collectively by planners on the basis of their professional expertise and discretion and are affected by politicians. Thus, the analysis illuminates the power exercised by municipal planning actors, and how their sorting affects the destiny of input received from citizens.

Discussion

In the following, we situate the results of our study in the broader field of participatory planning research and contrast our contribution with topics that need further investigation. We finish the paper by describing the policy implications of the study.

The idea for this article arose from curiosity about how citizen input is managed, judged and put to use within planning agencies, which has been described as the ‘black box’ of participatory planning (Healy Citation1997; Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005). We have opened the lid on this black box and shown that a process of sorting takes place. Through the study, we have begun to develop concepts and typologies that help us understand this process, and the analysis concerns the configuration of the sorting process, rather than the specific content of what input is adopted and rejected. Concerning the latter, the results indicate that citizen proposals that clearly conflict with legislation, political visions or what is regarded as ‘the public interest’, are most likely to be rejected. Likewise, citizen suggestions that are deemed to be ‘unrealistic’ in terms of cost or technical possibilities are likely to be rejected (cf. Eriksson Citation2015). However, in many cases it is a matter of perspective and judgement to determine what is legal, possible and proper to implement (Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2132). Further investigation of these judgements is needed to shed light on how specific issues and interests are accommodated in planning processes (cf. White Citation1996; Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009; Monno and Khakee Citation2012, 93). The framework of the sorting process elaborated in the article facilitates such further investigation by specifying what logics and considerations planning actors refer to when arguing that specific input should be adopted or rejected.

Favourable organizational conditions are vital to enable citizen influence (Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009; Faehnle and Tyrväinen Citation2013). Our study concerns rather small-scale planning processes within a small-town context with limited business interests. A common criticism within (urban) planning is that market interests surpass citizen voices (Swyngedouw Citation2005; Inch Citation2015), and thus one might expect that citizen influence should be higher in our context. However, other actors than the citizens control the planning processes analysed here, and if planners’ judgements or politicians’ visions differ from citizens interests, it is not obvious that citizen influence will be excessive (cf. Bickerstaff and Walker Citation2005, 2136; Vestbro Citation2012; Tahvilzadeh Citation2015). Moreover, in contexts where business interests are low, municipal resources might also be low (cf. Normann and Vasström Citation2012), which – as indicated by the study–can hamper citizen influence (cf. Eriksson Citation2015).

To be able to conceptualize the sorting process, we have emphasized similarities between the municipal planning authorities. Nonetheless, differences also emerged, which were often related to municipality size and the number of individuals involved in the planning process. In addition, several interviewees used phrases such as ‘We usually do it like this’ when explaining their sorting practices, which suggests that organizational routines and culture also affect the sorting process (cf. Normann and Vasström Citation2012). Thus, another vital topic for further research concerns how differences in the sorting process depend on context – for instance, the size and structure of the municipal administration, political majority, geography, demography etcetera. In our context, municipal officials were the leading actors in the sorting process, but in other contexts other actors – such as private contractors or other market actors – might hold this position. It is vital to investigate the structure and outcome of sorting processes in planning contexts in which other agencies dominate, such as large-scale urban settings (cf. Andersen and Pløger Citation2007; Monno and Khakee Citation2012).

The structure and outcome of the sorting process depend also on the methods for participation that are used, as this will affect the format of the input. For instance, the analysis shows that sketches on (physical) maps, oral arguments and comments scribbled on Post-it notes during workshops need more extensive translation than input formulated in text by the citizens themselves. In this respect, while not denigrating physical dialogues, new digital tools, such as interactive maps, might facilitate the sorting process by enabling more thorough and cohesive input from citizens (cf. Nyseth, Ringholm, and Agger Citation2019; Wilson, Tewdwr-Jones, and Comber Citation2019; Hofmann, Münster, and Noennig Citation2020). On the other hand, digital tools might also enable the leading planning actor to regulate the input by setting initial parameters for what it is possible to express. Such practices can reduce the need for the subsequent sorting of input, but risk depriving citizens of the possibility to control and freely formulate their input.

Policy implications

For participatory planning practices to be legitimate – and thus, for deliberative initiatives to complement representative democracy in a meaningful way – input from citizens must be seriously considered and must be able to affect the outcomes (Åström and Brorström Citation2011; Tahvilzadeh Citation2015, 245). Favourable conditions for such prospects include not only a genuine interest from planners and politicians (Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009; Monno and Khakee Citation2012, 93), but also the availability of resources and competence to accommodate citizen input (Faehnle and Tyrväinen Citation2013). Here, we show that the ability to adequately handle and sort citizen input is a vital aspect of participatory planning. The sorting processes we have investigated tended to be non-formal and intuitive, rather than formalized and measured. Hence, it is possible that reforming sorting processes to give them greater structure could improve the rigour of participatory practices, increasing transparency and equitable treatment. However, there is a risk that an over-formalized sorting procedure becomes too rigid and time-consuming. Rather than implementing a strict formalization, we suggest that the sorting of citizen input must be conducted with careful consideration. It is important that planners remain critically reflexive concerning their practice, and are not allured by propositions that represent only certain groups of citizens or powerful actors (cf. Dekker and Van Kempen Citation2009; Monno and Khakee Citation2012, 91p). Thus, it is important to increase awareness among planners and developers, and among municipal managers, that the sorting process is a crucial part of the participatory planning process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This article has mainly empirical ambitions – thus, it is not based on any single, specific theoretical framework. Rather, we use prior research to understand the practices we have investigated. However, we recognize the importance of understanding power relations when analysing participatory processes. In this, we rely on a Foucauldian, relational, perspective, while still recognizing other – more concrete – aspects of power (see Flyvbjerg Citation2004, 293).

2 Unlike the citizen dialogues, the consultation on the planning proposal can result in formal appeals, in which divergent opinions must be taken under legal consideration (Law Citation2010:900).

References

- Allmendinger, P., and G. Haughton. 2012. “Post-political Spatial Planning in England: A Crisis of Consensus?” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 (1): 89–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00468.x

- Amnå, E. 2006. “Playing with Fire? Swedish Mobilization for Participatory Democracy.” Journal of European Public Policy 13 (4): 587–606. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760600693952

- Andersen, J., and J. Pløger. 2007. “The Dualism of Urban Governance in Denmark.” European Planning Studies 15 (10): 1349–1367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310701550827

- Arnstein, S. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Åström, J., and S. Brorström. 2011. Medborgardialog i Centrala Älvstaden. Gothenburg: Mistra Urban Futures.

- Bickerstaff, K., and G. Walker. 2005. “Shared Visions, Unholy Alliances: Power, Governance and Deliberative Processes in Local Transport Planning.” Urban Studies 42 (12): 2123–2144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500332098

- Bond, S. 2011. “Negotiating a ‘Democratic Ethos’: Moving Beyond the Agonistic – Communicative Divide.” Planning Theory 10 (2): 161–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095210383081

- Connick, S., and J. Innes. 2003. “Outcomes of Collaborative Water Policy Making: Applying Complexity Thinking to Evaluation.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 46 (2): 177–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0964056032000070987

- Cornwall, A. 2008. “Unpacking ‘Participation’: Models, Meanings and Practices.” Community Development Journal 43 (3): 269–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn010

- Dekker, K., and R. Van Kempen. 2009. “Participation, Social Cohesion and the Challenges in the Governance Process: An Analysis of a Post-World War II Neighbourhood in the Netherlands.” European Planning Studies 17 (1): 109–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310802514011

- Demszky, A., and A. Nassehi. 2012. “Perpetual Loss and Gain: Translation, Estrangement and Cyclical Recurrence of Experience Based Knowledges in Public Action.” Policy and Society 31 (2): 169–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2012.04.006

- Eriksson, E. 2015. “Sanktionerat motstånd. Brukarinflytande som fenomen och praktik”. Diss., Lund University: School of Social Work.

- Faehnle, M., and L. Tyrväinen. 2013. “A Framework for Evaluating and Designing Collaborative Planning.” Land Use Policy 34: 332–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.04.006

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2004. “Phronetic Planning Research: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections.” Planning Theory & Practice 5 (3): 283–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935042000250195

- Forester, J. 1999. The Deliberative Practitioner. Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes. London: The MIT Press.

- Fung, A. 2006. “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance.” Public Administration Review 66 (1): 66–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

- Healy, P. 1997. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. London: Macmillan.

- Healy, P. 2002. “Collaborative Planning in Perspective.” Planning Theory 2 (2): 101–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952030022002

- Hofmann, M., S. Münster, and J. Noennig. 2020. “A Theoretical Framework for the Evaluation of Massive Digital Participation Systems in Urban Planning.” Journal of Geovisualization and Spatial Analysis 4 (3): 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s41651-019-0040-3

- Huxley, M., and O. Yiftachel. 2000. “New Paradigm or Old Myopia? Unsettling the Communicative Turn in Planning Theory.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 19 (4): 333–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X0001900402

- Inch, A. 2015. “Ordinary Citizens and the Political Cultures of Planning: In Search of the Subject of a new Democratic Ethos.” Planning Theory 14 (4): 404–424. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214536172

- Law 2010:900. Planning and Building Act.

- Monno, V., and A. Khakee. 2012. “Tokenism or Political Activism? Some Reflections on Participatory Planning.” International Planning Studies 17 (1): 85–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2011.638181

- Mouffe, C. 2002. Politics and Passion: The Stakes of Democracy. London: Centre of the Study of Democracy.

- Nguyen Long, L., M. Foster, and G. Arnold. 2019. “The Impact of Stakeholder Engagement on Local Policy Decision Making.” Policy Science 52 (4): 549–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-019-09357-z

- Normann, R., and M. Vasström. 2012. “Municipalities as Governance Network Actors in Rural Communities.” European Planning Studies 20 (6): 941–960. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.673565

- Nyseth, T., T. Ringholm, and A. Agger. 2019. “Innovative Forms of Citizen Participation at the Fringe of the Formal Planning System.” Urban Planning 4 (1): 7–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i1.1680

- Olausson, A., and J. Syssner. 2018. Mot en ny lokal utvecklingspolitik? Om svenska kommuners arbete för en stärkt lokal attraktionskraft. Linköping: Linköping University.

- Oliviera e Costa, S., and M. Tunström. 2018. Stege, trappa eller kub – hur analysera dialoger i stadsplanering? Nordregio policy brief #03, Jul 2018. Stockholm: Nordregio.

- Parvin, P. 2018. “Democracy Without Participation: A New Politics for a Disengaged Era.” Res Publica 24 (1): 31–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-017-9382-1

- Sager, T. 2009. “Planners’ Role: Torn Between Dialogical Ideals and Neo-Liberal Realities.” European Planning Studies 17 (1): 65–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310802513948

- Smedby, N., and L. Neij. 2013. “Experiences in Urban Governance for Sustainability: The Constructive Dialogue in Swedish Municipalities.” Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 148–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.044

- Smith, R. 1973. “A Theoretical Basis for Participatory Planning.” Policy Sciences 4 (3): 275–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01435125

- Swyngedouw, E. 2005. “Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-Beyond-the-State.” Urban Studies 42 (11): 1991–2006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279869

- Syssner, J. 2006. What Kind of Regionalism? Regionalism and Region Building in Northern European Peripheries. Frankfurt: Peter Lang Publishing Group.

- Tahvilzadeh, N. 2015. “Understanding Participatory Governance Arrangements in Urban Politics: Idealist and Cynical Perspectives on the Politics of Citizen Dialogues in Göteborg, Sweden.” Urban Research & Practice 8 (2): 238–254.

- Thorpe, A. 2017. “Rethinking Participation, Rethinking Planning.” Planning Theory & Practice 18 (4): 566–582. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1371788

- Vestbro, D. 2012. “Citizen Participation or Representative Democracy? The Case of Stockholm, Sweden.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 29 (1): 5–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43030956

- White, S. 1996. “Depoliticising Development: The Uses and Abuses of Participation.” Development in Practice 6 (1): 6–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0961452961000157564

- Wilson, A., M. Tewdwr-Jones, and R. Comber. 2019. “Urban Planning, Public Participation and Digital Technology: App Development as a Method of Generating Citizen Involvement in Local Planning Processes.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 46 (2): 286–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808317712515