?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The benefits of related variety on regional employment growth have become a prevailing view. However, these remain potential benefits unless channels (e.g. labour flows, inter-firm cooperation) and regional capabilities are in place to convert them into actual growth. This paper focuses on the labour mobility channel and proposes a way to measure the realized part of related variety. It demonstrates that in Sweden, core regions make ten times more use of their related variety potential via labour mobility than small, peripheral regions. Moreover, even in core and large regions only a handful of potential ties are realized. Most firms in small regions must rely on other channels to convert related variety potential into growth. Furthermore, while local labour flows between related industries are associated with higher employment growth, no evidence is found that, on average, other channels bring growth benefits in small regions. Thus, the paper argues that the role of market-mediated knowledge flow channels like labour mobility is underestimated compared to pure spillovers via unintended interactions. Consequently, it is important to go beyond assuming that the benefits of related variety are ‘in the air’ or in local ‘buzz’ and focus on specific channels at work.

Introduction

A key idea in evolutionary economic geography is that (knowledge) variety at local level provides gains that are central to the feedback mechanisms and path dependencies defining regional economic development patterns (Frenken and Boschma Citation2007). Since Frenken, Van Oort, and Verburg (Citation2007) seminal article, not any local knowledge diversity, but regional presence of industries with related knowledge profiles – related variety – is considered the best mix to trigger these positive feedback mechanisms, by facilitating knowledge spillovers and local learning. Consequently, growth benefits of related variety in regions have become a prevailing view in academic literature and an accepted policy assumption.

At the same time, empirical evidence is still inconclusive (Content and Frenken Citation2016). Not all industries (Bishop and Gripaios Citation2010; Hartog, Boschma, and Sotarauta Citation2012) and regional types benefit equally from related variety (Firgo and Mayerhofer Citation2018; Kuusk and Martynovich Citation2021; van Oort, de Geus, and Dogaru Citation2015). Some recent studies are even more critical arguing that over-relatedness hinders growth (Innocenti and Lazzeretti Citation2019) and that related variety can sometimes have negative externalities (Fitjar and Timmermans Citation2019). Hence, one can only support the call for a more context-sensitive re-theorisation of related variety (Gong and Hassink Citation2020).

This paper focuses on how regional context shapes the growth benefits of related variety. More specifically, it investigates how and to what extent different regions realize their related variety potential. The channels through which this potential is converted into growth remain underexplored in most empirical studies. However, knowledge flows and learning do not emerge automatically. They require interaction between persons from related industries (Feldman Citation2003), especially in case of uncodified or tacit knowledge that is embedded in persons. These interactions are channels for three types of knowledge flows: transaction-based flows (e.g. inter-firm collaborations), market-mediated spillovers (e.g. labour mobility) and pure spillovers (e.g. professional and social networks, chance encounters, information ‘buzz’) (Johansson Citation2005). While the presence of these channels does not guarantee the emergence of spillovers and learning nor their subsequent conversion into innovation and growth, their lack precludes it.

Studies usually focus on pure spillovers, assuming that growth benefits are simply ‘in the air’ (Marshall Citation1948) or in the ‘buzz’ (Storper and Venables Citation2004). The role of market-mediated spillovers (like labour flows) is often underestimated (Breschi and Lissoni Citation2001; McCann and Simonen Citation2005). Labour mobility between firms is, however, crucial in diffusing the latest knowledge and skills within and between regions (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2014; Duranton and Puga Citation2004; Gertler Citation2003). Furthermore, related labour flows also contribute to regional growth via matching mechanism. Since most job switches are local, related industries provide opportunities for high-quality skill matches beyond employees’ previous industry (Duranton and Puga Citation2004). This facilitates reallocation of labour during economic restructuring and crises (Eriksson and Hane-Weijman Citation2017) and increases productivity (Combes and Gobillon Citation2015). Thus, this study explores the role of labour flows as a realization channel of related variety potential in different regional contexts.

To measure realization of related variety potential, relatedness ties between colocated industries are divided into those realized through labour flows and those not. Based on this division, a realized related variety indicator is constructed to capture potential benefits created by related labour flows. Related variety based on the rest of the ties, in turn, represents potential benefits via other knowledge flow channels.

The study poses four research questions. The first one looks at realization of related variety. Since the rate of intra-regional job switches is higher in thick labour markets of large, dynamic regions compared to thin labour markets in peripheral ones (Hedin and Tegsjö Citation2006), realization of related variety is expected to be greater in the former.

RQ1: How does the realisation of related variety potential through labour mobility channel vary by regional type?

RQ2: How does realised (via labour flows) related variety’s contribution to regional employment growth vary by regional type?

RQ3: How does growth contribution of related variety realised via labour flows compare to the average effect of other channels?

RQ4: How does the contribution of inter-regional labour flows as a source of new related variety vary by regional type?

Related variety, labour mobility and regional employment growth

Longstanding debate on whether specialized or diversified industrial structures support regional growth was reinvigorated ten years ago by Frenken, Van Oort, and Verburg (Citation2007). They initiated a new stream of thought essentially combining insights from these two extremes by suggesting that not any diversity, but colocation of related industries – related variety – is beneficial to economic development. They defined related industries as those with a similar knowledge base. This cognitive similarity makes knowledge spillovers – beneficial exchange of ideas among individuals – and discovery of inter-industry complementarities easier (Nooteboom Citation2000). These local knowledge flows and complementarities lead to higher innovation and employment growth.

Related variety quickly became a popular concept and its growth benefits are widely accepted. Although most studies indicate that related variety supports employment growth, the empirical results are inconclusive (Content and Frenken Citation2016). One early explanation for such mixed results was that potential for knowledge spillovers varies by sectors (Bishop and Gripaios Citation2010; Hartog, Boschma, and Sotarauta Citation2012; Innocenti and Lazzeretti Citation2019). In recent work another explanation has emerged which shows that relevance of related variety differs by type and development capabilities of regions (Firgo and Mayerhofer Citation2018; Kuusk and Martynovich Citation2021; van Oort, de Geus, and Dogaru Citation2015). Other scholars have taken a more critical stand demonstrating potential negative effects of related variety (Fitjar and Timmermans Citation2019). This suggests that growth benefits should not be taken for granted. Besides cognitive proximity of actors, their interaction through various channels such as inter-firm collaborations, labour mobility, professional networks and social contacts is necessary to convert potential benefits of related variety into growth (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2014). Furthermore, this growth impact may vary by context (Gong and Hassink Citation2020).

Consequently, two issues emerge. First, regional related variety aims to capture the benefits to local actors (e.g. firms) from the colocation of actors from related industries. However, these benefits only arise when local knowledge is newly combined (learning) or local resources are redeployed (matching) by firms – i.e. when through various channels related variety changes at firm level. At regional level related variety represents firms’ and individuals’ potential opportunities to learn from local actors and to redeploy resources. These potential opportunities can contribute to regional development by acting as a source of new knowledge (including search environment for new ideas) to support innovation and as a source of better labour reallocation opportunities (compared to moving to an unrelated industry), leading to higher firm productivity and lower regional employment drops in economic downturn. Second, realization of this potential by firms likely varies by context. For example, as elaborated below, innovative regions likely gain more via learning and matching might matter more during crises. Thus, we should measure related variety both at regional level and its change at firm level to better understand its growth impact.

Labour-flow channel

Labour mobility is one channel how related variety ‘works’. The benefits of a job switch can materialize through various mechanisms. Most relevant here are learning and matching (Duranton and Puga Citation2004). When it comes to the former, labour flow between firms is a crucial channel to diffuse the latest knowledge and skills within a region (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2014; Brown and Rigby Citation2012; Castillo et al. Citation2019; Duranton and Puga Citation2004; Gertler Citation2003). It is thereby a key facilitator of localized learning and hence also regional development (Feldman Citation2003; Malmberg and Power Citation2005).

Both plant and regional level empirical studies find positive impact of related labour flows. At plant level, inflow of workers with experience from related industries has a positive impact on plant performance (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2008; Eriksson Citation2011; Eriksson and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017; Östbring, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2017), innovation propensity (Herstad, Sandven, and Ebersberger Citation2015) and new plant survival (Cappelli, Boschma, and Weterings Citation2019). At regional level, Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren (Citation2014) show that a high level of intra-regional labour flows between related industries has a positive impact on productivity and employment growth in Swedish regions. The case of Silicon Valley with its culture of frequent job changes as a source of knowledge diffusion is another good example of the benefits of related labour flows (Almeida and Kogut Citation1999; Saxenian Citation1994). Only one study points to a negative impact on smaller industries facing labour outflow to a dominating related industry (Fitjar and Timmermans Citation2019).

The impact of inter-regional related labour flows is not as clear cut. Some studies find that they increase productivity in some regions (Eriksson and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017; Timmermans and Boschma Citation2014), while others argue that their impact on plant performance is limited (Eriksson Citation2011). The reason might be that inter-regional job switches are often forced moves due to a lack of local employment opportunities, whereas intra-regional moves are more likely to be career related (Eriksson and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017).

That the benefits of related labour flows are driven by inter-industry complementarities and learning is the standard account of how related variety is converted into improved regional performance. The second explanation – its contribution via labour pooling to higher quality skill matches at regional level because most job switches tend to be local (Duranton and Puga Citation2004) – has received less attention.

Better opportunities for skill matching promote broader regional structural change. While labour reallocation’s role in structural adjustment process is well known (Pasinetti Citation1983), this line of reasoning has until recently been overlooked in the related variety literature (although it was pointed out already by Frenken, Van Oort, and Verburg [Citation2007]). Labour flows to related sectors allow for the lowering of adjustment costs of incremental change in a region’s industry structure and shifts between development paths when workers move from declining and/or lower productivity activities to growing and/or more productive industries (Aghion, David, and Foray Citation2006; Eriksson, Henning, and Otto Citation2016; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018). In other words, these moves provide potential for reuse and recombination of existing regional human capital in times of crisis and regional renewal (Eriksson and Hane-Weijman Citation2017; Eriksson, Henning, and Otto Citation2016; Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018; Jaax Citation2016). Recent work on the Dutch economy shows that related variety does provide labour reallocation opportunities, since industry-specific shocks do not coincide with relatedness (Diodato and Weterings Citation2014; Morkutė, Koster, and Van Dijk Citation2017). Thus, related variety might provide the portfolio effect protecting regions against adverse external shocks, although this benefit was initially attributed to unrelated variety (Frenken, Van Oort, and Verburg Citation2007). Better matching lowers also the likelihood that a person becomes unemployed or leaves the region in the near future (Combes and Gobillon Citation2015; Neffke, Otto, and Hidalgo Citation2018). Hence, by facilitating structural adjustment, related variety contributes both to lower unemployment levels and slower employment decline.

There are thus two mechanisms (learning and matching) whereby labour mobility converts related variety into growth. However, the rate of this conversion varies between regions. First, core and large regions tend to have higher intra-regional labour flows because the greater size and diversity of the labour market increases both the likelihood and quality of job matching (Duranton and Puga Citation2004; Moretti Citation2011). This means that large regions are more likely to ‘make use’ of the related variety potential through job switches between related industries. In smaller regions, moves into unrelated industries are often the only option.

Second, evolutionary economic geography defines regional trajectories largely by region’s internal intangible assets such as knowledge and institutions (McCann and Van Oort Citation2019), both of which vary by regions. First, due to larger home markets allowing for greater internal and external scale effects, more favourable transaction cost structures and advanced factors of production, regions at the top of a regional hierarchy can host emerging and innovation-intensive industries where knowledge spillovers play an important role (Boschma and Lambooy Citation1999; Krugman Citation1991; Lundquist and Olander Citation2001; Lundquist, Olander, and Henning Citation2008). Second, core regions have better general capabilities (including institutions) to innovate, adopt innovations made by others and develop these further. In these knowledge-intensive settings, firms engage in cutting-edge product and service innovation. Thus, learning both through labour mobility and other channels (like complex multi-partner knowledge cooperation and network or unintended interaction) is more likely to occur. Yet again, core regions are better equipped to take advantage of related variety than smaller, peripheral regions.

To sum up, labour mobility is an important channel converting related variety to growth either via learning through the circulation of knowledge, or matching labour supply and demand at regional level. These often go hand-in-hand. Furthermore, we can expect related variety to play a greater role in the development of core and large regions.

Data and empirical approach

Data

This study uses Statistics Sweden’s employee and plant level annual data from the Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA), for the years 1991–2010. For each individual registered in Sweden the database covers variables about the person (e.g. age, education, place of residence) and his/her main employment (e.g. industry, plant location, wage). Due to a focus on labour market developments, the analysis includes only the working age population (16–64-year-olds).

Statistics Sweden used two industry classifications during this period – SNI92 (for 1991–2001) and SNI02 (for 2002–2010).Footnote1 These were merged at the 5-digit level to ensure consistency over time. As SNI02 introduced only minor changes, an unambiguous conversion was possible. The merged classification was aggregated into 505 4-digit industries used in the analysis.

The main spatial units are 90 local labour markets (LAs; as classified in 2000). Their boundaries are defined by intensity of commuting flows between municipalities. This means that most interactions between workers seeking jobs and employers seeking labour occur within LAs (SCB Citation2010). Hence, LAs are appropriate as spatial units for linking the supply and demand in labour markets to study regional labour market performance. They are also considered the most suitable unit for agglomeration analysis (Frenken, Van Oort, and Verburg Citation2007; Mameli, Faggian, and McCann Citation2008).

The LAs were grouped into four regional types reflecting their development capabilities following the classification by the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth: core regions (Stockholm, Göteborg, Malmö), large (20 LAs), medium (23) and small (44) regions (NUTEK Citation2004). Average population of these regions is respectively 1.5 million, 160, 50 and 17 thousand inhabitants. All non-core LAs with universities belong to large regions, whereas some small regions represent expansive, low population density LAs in North-Sweden. Most of the high-tech industries are concentrated in core regions, while in several small regions main employer is public sector.

Measuring inter-industry relatedness

While the first studies on related variety used relatedness based on hierarchical industry classification, later more sophisticated approaches to capture inter-industry relatedness have been developed (Hidalgo et al. Citation2007; Neffke and Henning Citation2013). As the study focuses on labour flows, it uses skill relatedness indicator that measures relatedness in terms of similarities of workers’ skill requirements. Skill relatedness is calculated based on cross-industry labour flows working under the assumption that industries with similar skill needs typically have larger mutual labour flows (Neffke and Henning Citation2013). Neffke, Otto, and Weyh (Citation2017) show that it is a robust measure of inter-industry relatedness.

For each pair of 4-digit industries i and j (i ≠ j) an expected industry flow was estimated based on industry size, growth and wage using a zero-inflated negative binomial model.Footnote2 Skill relatedness was calculated as the ratio of observed to expected labour flow:

where

– observed labour flow between industries i and j;

– expected labour flow between the same industries. Two industries were considered related when observed labour flows exceed predicted flows, i.e. if

> 1 (at 5% significance level). Because the study covers 20 years, skill relatedness was calculated for five sub-periods (1991–1994, 1995–1998, 1999–2002, 2003–2006, 2007–2010) to allow changing over time.

Measuring regional related variety

Regional related variety was estimated using the regional skill relatedness (RSR) indicator proposed by Fitjar and Timmermans (Citation2017). They found that it captures industrial structure of many Norwegian manufacturing regions better than an entropy-based indicator.

where

– number of incoming and outgoing related ties for each industry i present in region r;

–share of industry i in regional employment;

– number of industries present in region r. RSR was calculated for 90 LAs in all five sub-periods.

The advantage of using RSR instead of the more common entropy-based related variety indicator is its straightforward interpretation as a (weighted) average number of local related ties per industry. In network theory this represents an average degree. Moreover, the focus on labour flows between industry-pairs makes a network measure more suitable than a system-wide entropy indicator. Also, many skill relatedness linkages are between 2-digit industry classification groups (Henning Citation2019; Kuusk and Martynovich Citation2021) and RSR allows this.

To measure how much of this colocation-based related variety potential (RSR) is realized via labour flows, a modified version of the RSR indicator is proposed. This only takes into account those related ties that have workers changing jobs between the concerned local industry-pair. Moreover, since spillovers are linked to one firm at a time and do not instantaneously spread to the whole industry (Cooper Citation2001), only plants with actual labour flow are likely to initially gain from labour mobility. Therefore, in calculating realized related variety each related tie is weighted based on employment share of local industry i plants that experienced this (incoming or outgoing) tie. It indirectly measures the changes in plant level related variety and can be interpreted as a (weighted) average number of local related industries that plants exchange labour with:

where

and

– equal 1 if there is labour flow from/to industry i to/from local related industry j, otherwise they equal 0;

and

– employment in industry i's plants with a labour flow to/from industry j in region r;

– employment in industry i in region r;

– share of industry i in regional employment;

– number of industries present in region r.

This indicator provides a general formula that can be applied to study related variety realized via various channels (e.g. inter-firm cooperation, social ties) and their combinations, and to compare it to colocation-based related variety potential. Similarly, connections between region’s all or unrelated industries can be estimated. The principle of comparing potential and realized relatedness ties is also applicable to other entities besides regions (e.g. clusters, industries, firms). This possibility of comparing potential and realized related variety is the indicator’s advantage compared to earlier measures aimed at capturing labour market externalities from related flows. These have relied, for example, on the number of people moving to related industries (Eriksson Citation2011), average share of related flows in intra-regional labour mobility and average skill-relatedness level of intra-regional flows (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2014).

The new colocation-based measure (RSR) is strongly correlated with the entropy-based related variety indicator (Appendix A1). The correlation coefficient (0.9) is comparable to the one found in Norway (0.8) (Fitjar and Timmermans Citation2017). Realized RSR has a correlation coefficient slightly over 0.6 with both related variety indicators. This suggests that regions realize the potential of their colocated related industries in different degrees.

This method of calculating realized related variety has its limitations. First, identification of related industries is based on the same labour flows as the following analysis of realized related variety. However, using two other relatedness measures did not alter the main results (Appendix A7). Second, RSR treats both incoming and outgoing relatedness ties equally. However, incoming ties likely have a stronger impact on plant performance because job switchers now apply their skills there. On the other hand, recruitment might lead to knowledge flows between two firms via social ties to former co-workers (Agarwal, Audretsch, and Sarkar Citation2007; Breschi and Lissoni Citation2009; Corredoira and Rosenkopf Citation2010; Dahl and Pedersen Citation2004; Lengyel and Eriksson Citation2016). Former employers might also benefit from the spread of information about their products (Rusten and Overå Citation2014). Thus, including both tie types was considered a suitable strategy to allow comparison with colocation-based RSR.

To assess the role of inter-regional labour flows (RQ4) a new realized related variety indicator () was calculated, taking into account both intra- and inter-regional labour inflows. To compare the contribution of labour-flow-ties with the rest of the ties (RQ3) another related variety indicator was calculated to capture growth potential from these other ties:

Assessing the relationship between related variety and regional employment growth

The relationship between various related variety indicators and regional employment growth was estimated through a fixed-effects model. A fixed-effects model estimates how change in region’s related variety is associated with change in its employment growth. It allows controlling for unobservable differences between LAs that might bias the results as shown by Firgo and Mayerhofer (Citation2018). The concern is relevant in the Swedish case since labour markets vary considerably in size, physical geography, economic activities etc. Hausman test suggested also using fixed effects.

where

– annual employment growth (defined as ln(EMPrt+3/EMPrt)/3) in region r during each sub-period

;

– related variety indicator for region r;

– matrix of regional type dummies (large, medium, small; reference: core);

– matrix of control variables (including constant). Term

controls for time-invariant unobservable regional characteristics (regional fixed effects),

represents region-invariant time effects and

represents the error term.

Regression includes control variables often used in growth models in related variety literature (Firgo and Mayerhofer Citation2018; Frenken, Van Oort, and Verburg Citation2007; Kublina and Fritsch Citation2018; van Oort, de Geus, and Dogaru Citation2015):Footnote3

Specialization: captures employment effects of intra-industry agglomeration externalities (i.e. localization economies) arising from regional specialization. Degree of regional specialization is measured by the Theil index (sum of location quotients of the SNI 2-digit industries weighted by their share in regional employment). This follows the approach taken by van Oort, de Geus, and Dogaru (Citation2015) and Firgo and Mayerhofer (Citation2018).

Population density: controls for general effects from the spatial agglomeration of economic activity (i.e. urbanization economies) as higher density enhances growth by enabling better interaction (Puga Citation2002).

Wage: median regional wage level controls for general economic convergence because regions with lower levels of economic development (and hence also lower wage levels) are expected to have higher employment growth.

Manufacturing: employment share in manufacturing captures the effects of regional specialization in manufacturing on growth. Bishop and Gripaios (Citation2010) suggest that spillovers might differ between services and manufacturing due to tradability level.

Human capital: captures human capital effects on regional employment development. It is measured as a share of workers with higher education (amongst workers older than 25 years).

Competition: controls for regional level competition between firms. It is measured as the inverse of number of employees per plant, but should be interpreted with care because it might also reflect mere scale factors (Bishop and Gripaios Citation2010).

Labour flow: controls for general level of labour flow in region as these are likely to vary depending on growth perspective of regional economy (Andersson and Tegsjö Citation2006). It is measured as a percentage of intra-regional skilled job switches to skilled employment.

To assess regional differences in the contribution of related variety, regressions include interaction terms between regional type and various RSR-indicators. All explanatory variables are in logarithm form (except those representing shares and RSR) and calculated for the first year of sub-periods to minimize potential endogeneity problems.

Background: employment growth and labour flows in Swedish regions

Before turning to the empirical results, some notes on the Swedish economy from 1991–2010 are presented. During these 20 years, employment in Sweden grew 9%, but the rate varied considerably over time and space (Appendix A2). While Sweden experienced one large crisis in both decades – in the beginning of the 1990s related to the banking crisis and in the end of the period a slowdown linked to the financial crisis of 2008 – the growth performance was much weaker in the first. This is partly related to the fact that the 1990s were a transformational period for the Swedish economy, as it started a shift towards more knowledge-intensive production. Consequently, manufacturing employment declined substantially in both large and small regions (Eriksson and Hane-Weijman Citation2017). This period was also characterized by a strong divergence process between regions and industries (Henning, Lundquist, and Olander Citation2016), as core regions succeeded in transforming their economies and thus marching ahead in terms of employment growth, while many smaller regions struggled to find their place in the new economy. The 2000s, on the other hand, displayed a more equal growth pattern amongst regions (Henning, Lundquist, and Olander Citation2016). Despite improved growth performance in non-core regions, many still ended up with negative overall employment growth.

This large-scale structural change in the Swedish economy and poor overall employment performance outside core regions influences how related variety impacts regional growth. For many regions the development story is not about (knowledge-spillover-based) innovation-induced employment growth. However, it is also unlikely that the results of this study are only related to labour mobility effects associated with employment decline. Both expanding and declining regions and sectors experienced a high level of job creation and destruction during this period (Eriksson and Hane-Weijman Citation2017). Hence, related variety’s impact on growth likely works through both mechanisms: it promotes innovation via learning and facilitates structural change via labour matching.

Looking at labour flows of skilled workersFootnote4 in Sweden, three regional differences that might lead to variation in realizing related variety growth potential stand out. First, smaller regions experience a much lower ratio of labour inflows to employment on average (Appendix A3). Throughout the whole period, the ratio has been around 50% higher in core regions compared to all other regional levels. This is not surprising given the general trend of people moving to core regions. The difference between core and all other regions was largest from the second half of the 1990s until the early 2000s. This can be explained by divergence in growth performance between core regions and the rest of the country during that period (Henning, Lundquist, and Olander Citation2016). In general terms, higher flow rate indicates that labour mobility might be a more important channel for related variety in core and large regions.

Second, while in core regions over 80% of labour (in)flows are intra-regional, in small regions only about half are (Appendix A4). The higher share of intra-regional job moves in larger regions, including those involving switching industry, is in line with previous findings (Eriksson, Lindgren, and Malmberg Citation2008; Hedin and Tegsjö Citation2006; Power and Lundmark Citation2004). This means that for small regions inter-regional flows are an important source to tap into related knowledge outside the region.

Third, distinguishing between within-industry, related and unrelated labour flows, the share of unrelated flows in total labour flows is almost 10 percentage points higher in small regions than in core regions. Related and within-industry flows both have corresponding lower shares. As was suggested, this indicates, that in smaller regions thinner labour markets allow poorer skill matching and chances to learn through diffusion or (re)combination of related knowledge are lower.

To sum up, small regions are in a disadvantaged position compared to core regions concerning intra-regional skilled labour flows as a working channel for related variety. They partly compensate for this through a higher share of inter-regional labour inflows as a source of new related knowledge.

Main findings

Labour flows as a channel and source of related variety

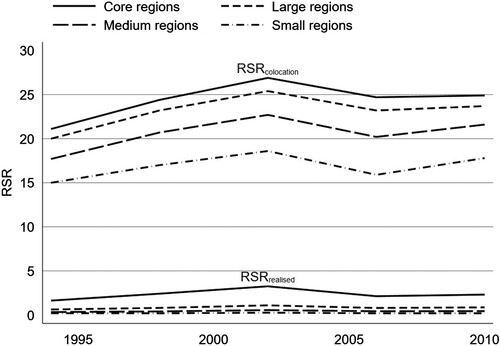

The colocation-based measure of related variety () shows a clear hierarchical pattern amongst the four regional levels – core regions have the highest and small regions the lowest variety (). Average related variety is about 40% lower in small regions, but it also varies considerably between them. Over 20 years, related variety has increased in all regional levels and out of 90 LAs only five small ones have experienced a slight decrease. The growth has been fastest in core and large regions, although similar to broader economic trends there has been some convergence after the 2000s. Overall, this suggests that potential growth benefits from related variety are higher in core and large regions.

Realization of related variety through local labour flows () follows the same hierarchical pattern, but the gap between core regions and the rest is much wider – realized related variety is 10 times higher in core regions compared to small ones (; Appendix A5). In core regions, an average firm exchanges labour with 2–3 local related industries during a 4-year period. In small regions, not all firms hire someone from a local related industry. Those that do, represent less than 20% of employment in small regions. This confirms our expectation that core regions have a much higher potential to benefit from related labour flows than the rest of the country. The trends for specific regions, however, vary significantly and realized related variety decreased in one-third of LAs during this period.

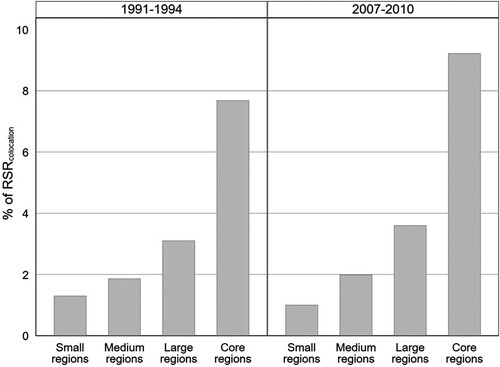

As expected, larger regions realize more of their related variety potential through local labour flows. Still, it is striking that only a handful of potential ties are realized (). For example, during the last sub-period (2007–2010), 9% of related variety is ‘covered’ by job switches in core regions, while small regions see only 1% of potential realized (Appendix A5). The latter is also the only regional level that has not managed to increase this share between 1991 and 2010. All others have seen a rise of 7–40%. This means that most firms and industries in small regions must rely on channels other than labour mobility to convert potential benefits of related variety into growth. The conclusion remains the same when realized related variety was calculated using classification-based and occupation-based relatedness as a robustness check (Appendix A7).

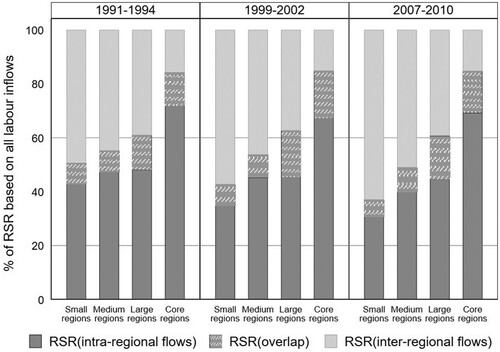

This disadvantage of small regions is partly compensated for by higher inter-regional labour flows that also contribute to regional skill diversity (Appendix A4). Small regions more than double their realized related variety when inter-regional flows are taken into account, whereas core regions gain about 20% (; Appendix A6). This difference partly reflects that in core regions half of related skill diversity accessed non-locally overlaps with the local skill diversity, while in small regions most related skills acquired via inter-regional inflows are new (10% overlap). Thus, confirming our expectation, inter-regional labour inflows are an important source of new related skills for small regions. Moreover, this importance has increased over the years.

Figure 3. Contributions by intra- and inter-regional labour inflows to realized related variety based on all labour inflows.

Note: Inter-regional RSR represents related variety gained beyond realized RSR based on intra-regional labour inflows. RSR(overlap) represents the part of inter-regional RSR that overlaps with intra-regional realized RSR.

Relationship between related variety and employment growth

We first confirm that regression results are in line with the related variety hypothesis – it is positively associated with employment growth (; Appendix 8). While in the simplest model (Model 1A) related variety is not statistically significant, once regional types are introduced in full specification (Model 1B), the relationship becomes significant. It is positive in core and large regions where increasing the average number of ties per industry by one is associated with a 0.25 percentage point increase in annual growth. In medium and small regions no statistically significant relationship is detected. This is in line with findings that related variety matters in Austrian urban regions (Firgo and Mayerhofer Citation2018) and supports employment growth in large, complex cities in New Zealand (Davies and Maré Citation2019), but contradicts van Oort, de Geus, and Dogaru (Citation2015) findings that related variety is not beneficial in capital regions and large cities in Europe. This contradiction could stem from more aggregate spatial level used in the latter, whereas the Austrian study used spatial units similar to this paper and the New Zealand study used urban areas.

Table 1. Regression results.

Models 2A and 2B test the relationship between related variety realized via labour flows and employment growth. Model 2A shows that realized related variety () has a positive and much stronger relationship to growth than colocation-based related variety. Again, the relationship varies by regional type, but this time the pattern is switched – the contribution is highest in small regions (Model 2B). In core regions, each additional related industry tie per firm is associated with a 1.6 percentage point increase in employment growth, while in small regions the increase is six times larger.Footnote5 The estimates are comparable to Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren (Citation2014), who used alternative measures to capture related labour flows.Footnote6

Growth contribution of related variety via other channels () also varies by regions (Models 3A and 3B). As expected, it is positive for core and large regions, but the size of the effect is a magnitude lower than for labour flow ties. This agrees with previous findings that actual labour flows have a larger impact than simply assuming that knowledge spillovers might occur without any direct evidence of linkages between firms (Breschi and Lissoni Citation2009; Broersma, Edzes, and Van Dijk Citation2016; Eriksson, Lindgren, and Malmberg Citation2008). No significant relationship is detected in medium-sized and small regions. This hints at that other channels are either also quite rare, bring no/low gains or that the impact varies substantially by context. Confirming our expectation, this suggests that growth benefits of related variety are not simply ‘in the air’ or in local ‘buzz’ (Fitjar and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017).

To check for robustness, the analysis was redone for three alternative specifications (see Appendix A10). In Alternative 1, there is no overlap for labour flows used to calculate RSR indicators and skill relatedness matrix. The two other alternatives are based only on the private sector, with one of them applying extra restrictions on job moves to further minimize the risk of including spurious flows (see Neffke, Otto, and Weyh Citation2017). The results remain largely similar in all specifications. Nonetheless, two changes should be mentioned. First, in Alternative 1 the association of realized related variety with growth is no longer stronger in small regions compared to the larger regions. Second, in Alternatives 2 and 3 the impact of other related ties is not statistically significant, but the coefficients are in line with other specifications. The main conclusions of the paper, however, remain unaffected by these differences. Lastly, restricting the analysis to incoming labour flows/ties or replacing regional type with population size (as a measure for regional development capabilities) in the regressions did not alter the identified patterns.

Discussion

The main outcome of the analysis is that the channels through which related variety facilitates growth indeed differ at various regional hierarchy levels. In the Swedish case, core regions ‘make use’ of their related variety potential via labour flows 10 times more than small regions. This confirms our expectations. Furthermore, this difference has widened over the 20-year period. However, even in core regions, only a handful of ties are realized through local labour flows.

At the same time, small regions benefit relatively more from recruitment beyond their borders. In these regions, plant level new pairings of related industry-knowledge more than doubled through inter-regional labour inflows, while in core regions the increase was only 20%. This indicates that small, peripheral regions gain access to knowledge from relatively more industries related to their industry mix via inter-regional labour flows than core and large regions. First, this confirms our expectation that inter-regional mobility plays an important role in broadening access to relevant skills in smaller regions. This is consistent with the finding that skilled labour inflow is important for creating local employment opportunities in Denmark’s peripheral regions (Naveed, Javakhishvili-Larsen, and Schmidt Citation2017). Second, although evolutionary economic geography emphasizes the role of local assets, inter-regional labour flows, as a source of new knowledge, can play an important role in some regions (Eriksson and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017).

Related labour flows have a stronger association with growth in smaller regions. As argued, this effect is a mix of two mechanisms – knowledge diffusion and spillovers (learning), and the ease of regional path adjustment via labour absorption by related industries (matching) – with opposite relationships to regional type. The current research design does not allow for distinguishing between their growth contributions. Stronger association in small regions suggests that matching effect dominates. However, it is also plausible that contrary to our hypothesis average knowledge spillovers of job switches in core regions are lower because many of them are not linked to knowledge-intensive industries, or that the reason and context of labour moves vary by regional hierarchy levels (Eriksson and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017; Henning Citation2019). This would agree with the findings that in Denmark related labour flows had a positive impact on plant performance only outside Copenhagen (Timmermans and Boschma Citation2014). Disentangling the effects would require a closer analysis of the exact mechanisms at work within firms and broader processes at regional level. Furthermore, given the pro-cyclical nature of the labour flows (Andersson and Tegsjö Citation2006), both the contribution of each mechanism and the general importance of labour flow channel are expected to vary by business cycle phase.

Related variety realized through labour flows has a positive association with employment growth of a magnitude larger than average combined effect of other channels. This, however, does not mean that ties realized through other channels have a lower effect compared to labour moves. On the contrary, one can expect multi-partner innovation projects to have a much larger impact on firm growth than recruitment of a new employee. Furthermore, people are more likely to move between the firms that are already cooperating or linked through other kinds of relationships (e.g. input-output links) (Hjertvikrem and Fitjar Citation2020). Recruitment itself can also lead to such ties with ex-employers (Cantner and Graf Citation2006). Thus, part of the observed effect might reflect the benefits of these other relationships and not only the recruitment itself. However, even then recruitment is expected to have an additional effect, since it might bring new knowledge due to person’s altered social and organizational embeddedness (Hjertvikrem and Fitjar Citation2020).

The finding that core and large regions benefit from related variety more and beyond labour moves, while on average small regions gain only from the latter, is in line with the research suggesting that knowledge spillovers between related industries are more important for technology-intensive environments (Cortinovis and van Oort Citation2015; Hartog, Boschma, and Sotarauta Citation2012). It is in these settings that cutting-edge product and service innovation occurs, and more complex channels like multi-partner research cooperation and knowledge networks, but also those stemming from chance encounters, can flourish. Eriksson and Hansen (Citation2013), for example, suggest that Swedish peripheral regions might be too small for diversity-based development dynamics to emerge. The economic activities in small regions are likely to require organizational proximity (Boschma Citation2005) and intentional interaction for knowledge spillovers and diffusion to occur. Hence, the key channel in this case is labour flows. On the other hand, given higher social capital and trust levels in small tight-knit communities, in some cases the lack of organizational proximity might be compensated for through social or professional networks (Maskell and Malmberg Citation1999) or via locally organized webs of input-output relationships. Thus, these are also plausible channels in small regions, but in employed data this average combined effect is not strong enough to be picked up.

From a methodological viewpoint, this study agrees with the conclusions by Firgo and Mayerhofer (Citation2018) that analysed spatial units need to be chosen carefully because the relationship between related diversity and growth varies considerably by regional type. Therefore, using fine-grained spatial units with consistent regional character (e.g. labour market regions) is preferred to the use of broad geographical areas (e.g. NUTS2) which often consist of both urban and smaller non-urban regions hosting different kinds of economic activities. The use of consistent spatial units is essential to capture the potential heterogeneity of impacts by regional type (Firgo and Mayerhofer Citation2018). As argued earlier, it is the difference in spatial units that can serve as one explanation for why the results of this study contradict the conclusions reached by van Oort, de Geus, and Dogaru (Citation2015). The second methodological observation is that only looking at colocation-based related variety without analyzing the realized channels runs the risk of not detecting the benefits of related variety in some regional types (e.g. small, peripheral regions in this case).

Conclusions

This study explores labour mobility’s role as a realization channel and source of local related knowledge diversity. Confirming our expectations, it demonstrates that core and large regions are better placed than small, peripheral regions to benefit from related variety. Core regions realize ten times more of their related variety potential via local labour flows than small regions. For small regions, inter-regional labour flows are a relatively more important source of related knowledge flows. Still, this is not sufficient to reach the level of core regions’ related knowledge flows. From the evolutionary viewpoint, this suggests that via labour mobility channel related variety of local industry mix is more likely to trigger positive feedback mechanisms in large regions and tends to uphold the existing regional hierarchy patterns.

In line with previous research, this study also finds that related labour flows have a positive association with employment growth. The wider implication is that regional related knowledge diversity brings growth benefits as suggested by evolutionary economic geography. The association is stronger in smaller regions, but their poor overall economic performance during the study period might influence the generalisability of this result. Namely, during hard times small regions are expected to gain relatively more via easier labour reallocation (Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018). Core regions benefit also from related variety realized via other channels, but the association is a magnitude weaker. It is unclear whether small, peripheral regions on average benefit beyond labour mobility channel.

At a more general level the results raise three issues. First, the findings underline the importance of going beyond simply assuming that the benefits of related variety are ‘in the air’ and paying more attention to specific channels and mechanisms at work. They resonate with the research that questions the importance of local ‘buzz’ and pure knowledge spillovers, and instead emphasize the role of market-mediated knowledge flows (Breschi and Lissoni Citation2009; Fitjar and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017; Power and Lundmark Citation2004). The results also support the suggestions that labour-based spillovers via learning rather work at firm level and not at regional one (Broersma, Edzes, and Van Dijk Citation2016).

Second, it is important to acknowledge the two different mechanisms at work. While the initial theory focused on knowledge spillovers and learning, labour reallocation in structural adjustment processes might be of equal importance. Some recent work on regional resilience and structural change emphasizes the benefits of related variety (Diodato and Weterings Citation2014; Eriksson and Hane-Weijman Citation2017; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018), but the dual role of labour flows is not explicitly addressed in the general conceptualization of related variety.

Third, since only a handful of local related ties are realized, knowledge diffusion patterns are not determined, and most potential local related knowledge combinations are not explored. Consequently, although related variety’s role in structural adjustment processes tends to keep regions in a gradual path adjustment trajectory, its contribution via local learning leaves plenty of room for chance.

The results highlight two policy implications. First, the findings demonstrate once again that related variety per se might not be beneficial in all regional settings (Firgo and Mayerhofer Citation2018; Hartog, Boschma, and Sotarauta Citation2012; van Oort, de Geus, and Dogaru Citation2015). It is likely that the gains from related variety in small, peripheral regions largely depend on and vary according to the specific regional context. Therefore, policies aimed at benefitting from related variety are likely to succeed only if they are grounded on local preconditions and accompanied by measures facilitating the channels underlying the gains from knowledge diffusion and combination (Kublina and Fritsch Citation2018). The measures could include, for example, increasing the awareness of recruiters and public employment services about the benefits of hiring or re-training people from related sectors (Cappelli, Boschma, and Weterings Citation2019), supporting inter-firm cooperation and entrepreneurship (Kublina and Fritsch Citation2018). Second, the study highlights the importance of inter-regional labour flows for smaller, peripheral regions. Therefore, in these cases it is important to consider policies promoting inter-regional mobility (Naveed, Javakhishvili-Larsen, and Schmidt Citation2017).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (52 KB)Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for constructive comments by Karl-Johan Lundquist, Markus Grillitsch, Martin Henning and the reviewers. The database used in the article was supported with funding of Länsförsäkringar Alliance Research Foundation through the project Regional Growth against All Odds (ReGrow).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 SNI and NACE are identical up to the 4-digit level. SNI92 and SNI02 correspond to NACE Revision 1 and 1.1.

2 For a detailed description, please consult the methodological appendix to Neffke and Henning (Citation2013).

3 Appendix A9 presents correlation between variables.

4 As defined in skill relatedness calculation.

5 Note that change by one tie is outside the range of observed changes.

6 In an average LA, a 10% increase in related labour flow variable is associated with 0.5 and 0.4 percentage point increase in growth, respectively (Model 2A).

References

- Agarwal, R., D. Audretsch, and M. Sarkar. 2007. “The Process of Creative Construction: Knowledge Spillovers, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1 (3–4): 263–286. doi:10.1002/sej.36.

- Aghion, P., P. David, and D. Foray. 2006. Linking Policy Research and Practice in ‘STIG Systems’: Many Obstacles, but Some Ways Forward SIEPR Discussion Paper No. 06-09. Stanford: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

- Almeida, P., and B. Kogut. 1999. “Localization of Knowledge and the Mobility of Engineers in Regional Networks.” Management Science 45 (7): 905–917. doi:10.1287/mnsc.45.7.905.

- Andersson, J., and B. Tegsjö. 2006. En rörlig arbetsmarknad – dynamiken bland jobb, individer och företag Fokus på näringsliv och arbetsmarknad våren 2006. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden (SCB).

- Bishop, P., and P. Gripaios. 2010. “Spatial Externalities, Relatedness and Sector Employment Growth in Great Britain.” Regional Studies 44 (4): 443–454. doi:10.1080/00343400802508810.

- Boschma, R. 2005. “Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1080/0034340052000320887.

- Boschma, R., R. Eriksson, and U. Lindgren. 2008. “How does Labour Mobility Affect the Performance of Plants? The Importance of Relatedness and Geographical Proximity.” Journal of Economic Geography 9 (2): 169–190. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn041.

- Boschma, R., R. Eriksson, and U. Lindgren. 2014. “Labour Market Externalities and Regional Growth in Sweden: The Importance of Labour Mobility between Skill-Related Industries.” Regional Studies 48 (10): 1669–1690. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.867429.

- Boschma, R., and J. Lambooy. 1999. “Evolutionary Economics and Economic Geography.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 9 (4): 411–429. doi:10.1007/s001910050089.

- Breschi, S., and F. Lissoni. 2001. “Localised Knowledge Spillovers vs. Innovative Milieux: Knowledge ‘Tacitness’ Reconsidered.” Papers in Regional Science 80 (3): 255–273. doi:10.1007/PL00013627.

- Breschi, S., and F. Lissoni. 2009. “Mobility of Skilled Workers and Co-invention Networks: An Anatomy of Localized Knowledge Flows.” Journal of Economic Geography 9 (4): 439–468. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp008.

- Broersma, L., A. Edzes, and J. Van Dijk. 2016. “Human Capital Externalities: Effects for Low-educated Workers and Low-Skilled Jobs.” Regional Studies 50 (10): 1675–1687. doi:10.1080/00343404.2015.1053446.

- Brown, M., and D. Rigby. 2012. “Marshallian Localization Economies: Where do They Come From and to Whom do They Flow?” In Beyond Territory: Dynamic Geographies of Innovation and Knowledge Creation, edited by H. Bathelt, M. Feldman, and D. Kogler, 21–45. London: Routledge.

- Cantner, U., and H. Graf. 2006. “The Network of Innovators in Jena: An Application of Social Network Analysis.” Research Policy 35 (4): 463–480. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2006.01.002.

- Cappelli, R., R. Boschma, and A. Weterings. 2019. “Labour Mobility, Skill-Relatedness and New Plant Survival Across Different Development Stages of an Industry.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 51 (4): 869–890. doi:10.1177/0308518X18812466.

- Castillo, V., L. Figal Garone, A. Maffioli, S. Rojo, and R. Stucchi. 2019. “Knowledge Spillovers Through Labour Mobility: An Employer–Employee Analysis.” The Journal of Development Studies 56 (3): 469–488.

- Chadwick, A., J. Glasson, and H. Smith. 2008. “Employment Growth in Knowledge-Intensive Business Services in Great Britain During the 1990s – Variations at the Regional and Sub-Regional Level.” Local Economy 23 (1): 6–18. doi:10.1080/02690940801917384.

- Combes, P.-P., and L. Gobillon. 2015. “The Empirics of Agglomeration Economies.” In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, Vol. 5, edited by G. Duranton, J. Henderson, and W. Strange, 247–348. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Content, J., and K. Frenken. 2016. “Related Variety and Economic Development: A Literature Review.” European Planning Studies 24 (12): 2097–2112. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1246517.

- Cooper, D. 2001. “Innovation and Reciprocal Externalities: Information Transmission via Job Mobility.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 45 (4): 403–425. doi:10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00154-8.

- Corredoira, R., and L. Rosenkopf. 2010. “Should Auld Acquaintance be Forgot? the Reverse Transfer of Knowledge Through Mobility Ties.” Strategic Management Journal 31 (2): 159–181.

- Cortinovis, N., and F. van Oort. 2015. “Variety, Economic Growth and Knowledge Intensity of European Regions: A Spatial Panel Analysis.” The Annals of Regional Science 55 (1): 7–32. doi:10.1007/s00168-015-0680-2.

- Dahl, M., and C. Pedersen. 2004. “Knowledge Flows Through Informal Contacts in Industrial Clusters: Myth or Reality?” Research Policy 33 (10): 1673–1686. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.10.004.

- Davies, B., and D. Maré. 2019. “Relatedness, Complexity and Local Growth.” IZA Discussion Paper, DP No. 12223.

- Diodato, D., and A. Weterings. 2014. “The Resilience of Regional Labour Markets to Economic Shocks: Exploring the Role of Interactions among Firms and Workers.” Journal of Economic Geography 15 (4): 723–742. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu030.

- Duranton, G., and D. Puga. 2004. “Micro-foundations of Urban Agglomeration Economies.” In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, Vol. 4, edited by J. Henderson, and J. Thisse, 2063–2117. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Eriksson, R. 2011. “Localized Spillovers and Knowledge Flows – How does Proximity Influence the Performance of Plants.” Economic Geography 87 (2): 127–152. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01112.x.

- Eriksson, R., and E. Hane-Weijman. 2017. “How do Regional Economies Respond to Crises? The Geography of Job Creation and Destruction in Sweden (1990–2010).” European Urban and Regional Studies 24 (1): 87–103. doi:10.1177/0969776415604016.

- Eriksson, R., and H. Hansen. 2013. “Industries, Skills, and Human Capital: How does Regional Size Affect Uneven Development?” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (3): 593–613. doi:10.1068/a45186.

- Eriksson, R., M. Henning, and A. Otto. 2016. “Industrial and Geographical Mobility of Workers During Industry Decline: The Swedish and German Shipbuilding Industries 1970–2000.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 75: 87–98. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.06.020.

- Eriksson, R., U. Lindgren, and G. Malmberg. 2008. “Agglomeration Mobility: Effects of Localisation, Urbanisation, and Scale on job Changes.” Environment and Planning A 40 (10): 2419–2434. doi:10.1068/a39312.

- Eriksson, R., and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2017. “Job-related Mobility and Plant Performance in Sweden.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 83: 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.04.019.

- Feldman, M. 2003. “Location and Innovation: The New Economic Geography of Innovation, Spillovers, and Agglomeration.” In The Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography, edited by G. Clark, M. Gertler, and M. Feldman, 373–394. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Firgo, M., and P. Mayerhofer. 2018. “(Un)Related Variety and Employment Growth at the sub-Regional Level.” Papers in Regional Science 97 (3): 519–547. doi:10.1111/pirs.12276.

- Fitjar, R., and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2017. “Nothing is in the Air.” Growth and Change 48 (1): 22–39. doi:10.1111/grow.12161.

- Fitjar, R., and B. Timmermans. 2017. “Regional Skill Relatedness: Towards a new Measure of Regional Related Diversification.” European Planning Studies 25 (3): 516–538. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1244515.

- Fitjar, R., and B. Timmermans. 2019. “Relatedness and the Resource Curse: Is There a Liability of Relatedness?” Economic Geography 95 (3): 231–255. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1544460.

- Frenken, K., and R. Boschma. 2007. “A Theoretical Framework for Evolutionary Economic Geography: Industrial Dynamics and Urban Growth as a Branching Process.” Journal of Economic Geography 7 (5): 635–649. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm018.

- Frenken, K., F. Van Oort, and T. Verburg. 2007. “Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Economic Growth.” Regional Studies 41 (5): 685–697. doi:10.1080/00343400601120296.

- Gertler, M. 2003. “Tacit Knowledge and the Economic Geography of Context, or The Undefinable Tacitness of Being (There).” Journal of Economic Geography 3 (1): 75–99. doi:10.1093/jeg/3.1.75.

- Gong, H., and R. Hassink. 2020. “Context Sensitivity and Economic-Geographic (Re)theorising.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 13 (3): 475–490. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsaa021.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and M. Trippl. 2018. “Unrelated Knowledge Combinations: The Unexplored Potential for Regional Industrial Path Development.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (2): 257–274. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy012.

- Hane-Weijman, E., R. Eriksson, and M. Henning. 2018. “Returning to Work: Regional Determinants of Re-employment After Major Redundancies.” Regional Studies 52 (6): 768–780. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1395006.

- Hartog, M., R. Boschma, and M. Sotarauta. 2012. “The Impact of Related Variety on Regional Employment Growth in Finland 1993–2006: High-Tech Versus Medium/Low-Tech.” Industry and Innovation 19 (6): 459–476. doi:10.1080/13662716.2012.718874.

- Hedin, G., and B. Tegsjö. 2006. Lokala arbetsmarknader – egenskaper, struktur och utveckling. Örebro: SCB.

- Henning, M. 2019. “Regional Labour Flows between Manufacturing and Business Services: Reciprocal Integration and Uneven Geography.” European Urban and Regional Studies 27 (3): 290–302. doi:10.1177/0969776419834065.

- Henning, M., K.-J. Lundquist, and L.-O. Olander. 2016. “Regional Analysis and the Process of Economic Development: Changes in Growth, Employment and Income.” In Structural Analysis and the Process of Economic Development, edited by J. Ljungberg, 149–173. New York: Routledge.

- Herstad, S., T. Sandven, and B. Ebersberger. 2015. “Recruitment, Knowledge Integration and Modes of Innovation.” Research Policy 44 (1): 138–153. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.06.007.

- Hidalgo, C., B. Klinger, A.-L. Barabási, and R. Hausmann. 2007. “The Product Space Conditions the Development of Nations.” Science 317 (5837): 482–487. doi:10.1126/science.1144581.

- Hjertvikrem, N., and R. Fitjar. 2020. “One or all Channels for Knowledge Exchange in Clusters? Collaboration, Monitoring and Recruitment Networks in the Subsea Industry in Rogaland, Norway.” Industry and Innovation 28 (2): 182–200.

- Innocenti, N., and L. Lazzeretti. 2019. “Growth in Regions, Knowledge Bases and Relatedness: Some Insights from the Italian Case.” European Planning Studies 27 (10): 2034–2048. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1588862.

- Jaax, A. 2016. “Skill Relatedness and Economic Restructuring: The Case of Bremerhaven.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 3 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1116958.

- Johansson, B. 2005. “Parsing the Menagerie of Agglomeration and Network Externalities.” In Industrial Clusters and Inter-Firm Networks, edited by C. Karlsson, B. Johansson, and R. Stough, 107–147. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Krugman, P. 1991. Geography and Trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kublina, S., and M. Fritsch. 2018. “Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Growth: the Role of Absorptive Capacity and Entrepreneurship.” Regional Studies 52 (10): 1360–1371. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1388914.

- Kuusk, K., and M. Martynovich. 2021. “Dynamic Nature of Relatedness, or What Kind of Related Variety for Long-Term Regional Growth.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 112 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1111/tesg.12427.

- Lengyel, B., and R. Eriksson. 2016. “Co-worker Networks, Labour Mobility and Productivity Growth in Regions.” Journal of Economic Geography 17 (3): 635–660.

- Lundquist, K.-J., and L.-O. Olander. 2001. Den glömda strukturcykeln. Ny syn på industrins regionala tillväxt och omvandling Rapporter och Notiser 161. Lund: Institutionen för kulturgeografi och ekonomisk geografi, Lunds universitet.

- Lundquist, K.-J., L.-O. Olander, and M. Henning. 2008. “Decomposing the Technology Shift: Evidence from the Swedish Manufacturing Sector.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 99 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2008.00450.x.

- Malmberg, A., and D. Power. 2005. “(How) do (Firms in) Clusters Create Knowledge?” Industry and Innovation 12 (4): 409–431. doi:10.1080/13662710500381583.

- Mameli, F., A. Faggian, and P. McCann. 2008. “Employment Growth in Italian Local Labour Systems: Issues of Model Specification and Sectoral Aggregation.” Spatial Economic Analysis 3 (3): 343–360. doi:10.1080/17421770802353030.

- Marshall, A. 1948. Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan.

- Maskell, P., and A. Malmberg. 1999. “Localised Learning and Industrial Competitiveness.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 23 (2): 167–185. doi:10.1093/cje/23.2.167.

- McCann, P., and J. Simonen. 2005. “Innovation, Knowledge Spillovers and Local Labour Markets.” Papers in Regional Science 84 (3): 465–485. doi:10.1111/j.1435-5957.2005.00036.x.

- McCann, P., and F. Van Oort. 2019. “Theories of Agglomeration and Regional Economic Growth: A Historical Review.” In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories, edited by R. Capello, and P. Nijkamp, 6–23. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Moretti, E. 2011. “Local Labor Markets.” In Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 4B, edited by C. David, and A. Orley, 1237–1313. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Morkutė, G., S. Koster, and J. Van Dijk. 2017. “Employment Growth and Inter-industry Job Reallocation: Spatial Patterns and Relatedness.” Regional Studies 51 (6): 958–971. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1153800.

- Naveed, A., N. Javakhishvili-Larsen, and T. Schmidt. 2017. “Labour Mobility and Local Employment: Building a Local Employment Base from Labour Mobility?” Regional Studies 51 (11): 1622–1634. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1223284.

- Neffke, F., and M. Henning. 2013. “Skill Relatedness and Firm Diversification.” Strategic Management Journal 34 (3): 297–316. doi:10.1002/smj.2014.

- Neffke, F., A. Otto, and C. Hidalgo. 2018. “The Mobility of Displaced Workers: How the Local Industry mix Affects job Search.” Journal of Urban Economics 108: 124–140. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2018.09.006.

- Neffke, F., A. Otto, and A. Weyh. 2017. “Inter-industry Labor Flows.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 142: 275–292. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2017.07.003.

- Nooteboom, B. 2000. Learning and Innovation in Organizations and Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- NUTEK. 2004. Analyser för regionalt utvecklingsarbete - En handbok med praktiska tips och metodexempel. Stockholm: Verket för näringslivsutveckling (NUTEK).

- Östbring, L., R. Eriksson, and U. Lindgren. 2017. “Labour Mobility and Organisational Proximity: Routines as Supporting Mechanisms for Variety, Skill Integration and Productivity.” Industry and Innovation 24 (8): 775–794. doi:10.1080/13662716.2017.1295362.

- Pasinetti, L. 1983. Structural Change and Economic Growth: A Theoretical Essay on the Dynamics of the Wealth of Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Power, D., and M. Lundmark. 2004. “Working Through Knowledge Pools: Labour Market Dynamics, the Transference of Knowledge and Ideas, and Industrial Clusters.” Urban Studies 41 (5–6): 1025–1044. doi:10.1080/00420980410001675850.

- Puga, D. 2002. “European Regional Policies in Light of Recent Location Theories.” Journal of Economic Geography 2 (4): 373–406. doi:10.1093/jeg/2.4.373.

- Rusten, G., and R. Overå. 2014. “Local and Global Geographies of Innovation: Structures, Processes, and Geographical Contexts from a Firm Perspective.” Growth and Change 45 (3): 403–411. doi:10.1111/grow.12051.

- Saxenian, A. 1994. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- SCB. 2010. Lokala arbetsmarknader — egenskaper, utveckling och funktion. Örebro: SCB.

- Storper, M., and A. Venables. 2004. “Buzz: Face-to-Face Contact and the Urban Economy.” Journal of Economic Geography 4 (4): 351–370. doi:10.1093/jnlecg/lbh027.

- Timmermans, B., and R. Boschma. 2014. “The Effect of Intra- and Inter-Regional Labour Mobility on Plant Performance in Denmark: The Significance of Related Labour Inflows.” Journal of Economic Geography 14 (2): 289–311. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbs059.

- van Oort, F., S. de Geus, and T. Dogaru. 2015. “Related Variety and Regional Economic Growth in a Cross-Section of European Urban Regions.” European Planning Studies 23 (6): 1110–1127. doi:10.1080/09654313.2014.905003.