ABSTRACT

In the literature on regional industrial path development, the path-as-process perspective conceptualizes the emergence, evolution, transformation, and decline of regional industries in the long term. However, critical questions about the role of agency in path development and transformation remain open, partly due to a frequent empirical focus on isolated episodes. This article argues that path development should be seen as a long-term sequence that includes episodes of path development interrupted by occasional episodes of transformation. These transformative episodes are driven by agency within a changing or stable structural context. Such a discontinuity-development model focuses attention on how and why agency patterns change and on which practices agents employ during critical junctures. An empirical vignette on the long-term development of tourism in Eilat, Israel, illustrates how the model can be applied and elucidates methodological challenges for further empirical research.

JEL:

The literature on regional industrial path development (e.g. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Blažek et al. Citation2020; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018; Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013) examines how regional industries emerge, evolve, decline, and transform. Yet, understanding the long-term evolution of regional economies requires a historical perspective (Henning Citation2019) that covers not just isolated episodes of path development and transformation but their sequence (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b). Martin’s (Citation2010) path-as-process model offers such a long-term perspective but remains vague in analysing changing ‘patterns of agency’ (Sotarauta et al. Citation2021, 93) between path development episodes. In particular, how different patterns of agency such as change agency (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020), reproductive agency (Bækkelund Citation2021; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Nielsen Citation2021a), or maintenance agency (Henderson Citation2020; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020) tip the balance towards certain forms of path development remains a critical question.

Hence, this article aims at shedding light on (i) how paths can be conceptualized in a long-term perspective that connects radical discontinuity with gradual development, (ii) how agency affects the shifts between these episodes. The article argues that for a more precise understanding of long-term regional evolution, we should look at sequences of path development interrupted and linked by occasional path transformation. Such a sequence does not follow a deterministic logic but can unfold in various ways (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Strambach and Halkier Citation2013). Specifically, a focus on changing agency patterns during critical junctures of transformation (Bækkelund Citation2021; Beer, Barnes, and Horne Citation2021) can significantly improve our understanding of long-term path development (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b).

Empirically, such a discontinuity-development model offers a framework for refining the analysis of long-term path development and agency patterns at critical junctures and thus responds to the methodological challenges for analysing agency Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta (Citation2021b) identify. To do so, this article takes inspiration from an empirical strategy of ‘temporal bracketing’ (Langley Citation1999, 703) which has proven useful for an evolutionary perspective (Stephens and Sandberg Citation2020).

The article starts by reviewing the path development literature and the path-as-process perspective before proposing a simple path discontinuity-development model. In a brief empirical vignette, the article interprets approximately six decades of history of the tourism sector in Eilat, Israel, as a sequence of path development and transformation and thus illustrates features of the model and highlights methodological challenges. The article closes with an outlook on further research.

Regional industrial path development and transformation

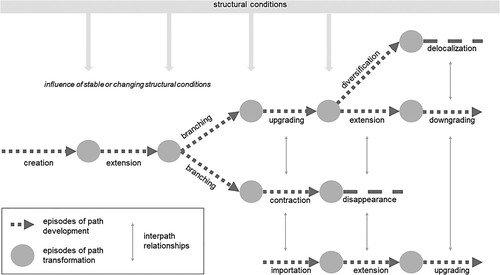

The path development literature builds on the fundamental assumption that path dependence is an evolutionary process (Garud and Karnøe Citation2001; Martin Citation2010; Martin and Sunley Citation2006) and produced a typology of path extension, branching, diversification, creation, importation, and upgrading (Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018; Isaksen, Tödtling, and Trippl Citation2018; Isaksen et al. Citation2019; Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013) as well as path contraction, downgrading, delocalization, and eventual disappearance (Blažek et al. Citation2020). Recently, major changes of paths have been conceptualized as path transformation (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019) and the relationships between different paths have been discussed (Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019).

However, empirical studies tend to regard path development as isolated episodes or at most as a sequence of few episodes (e.g. Bækkelund Citation2021; Dawley Citation2014; Isaksen et al. Citation2019; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019; Sotarauta et al. Citation2021). There are partial exceptions though. Some studies address longer sequences covering up to roughly five decades (e.g. Binz and Gong Citation2021; Isaksen Citation2015) and consider up to three specifically designated episodes of path development (e.g. Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020), though some remain vague in defining specific forms of path development (e.g. Binz and Gong Citation2021). Those studies that refer to only one episode show that even a single episode of path development can span two decades or more (e.g. Miörner and Trippl Citation2017; Rekers and Stihl Citation2021) which suggests that a historical perspective going beyond isolated episodes needs to span longer periods (Henning Citation2019).

A focus on isolated episodes risks neglecting the nexus between path development and transformation and makes it difficult to analyse and compare changing patterns of agency in and between these different episodes. Save a few studies that focus on transformation (e.g. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019), such a focus on isolated episodes privileges ‘“on-path” evolution’ (Martin Citation2010, 9) over processes of radical change that transform paths from one form into another although Martin (Citation2012) stresses the relevance of both types of evolution, radical discontinuity and gradual development.Footnote1

Empirically, looking at isolated episodes limits the possibilities for inter-temporal replication of findings that enables analysing simultaneous and bidirectional structure-agency dynamics through temporal bracketing (Langley Citation1999). Hence, there is a need for a more long-term perspective suitable for conceptualizing shifts between forms of path development (Blažek et al. Citation2020) and the ‘dependence between successive paths’ (Martin and Sunley Citation2006, 427) which remains underexplored (MacKinnon et al. Citation2019).

Conceptualizations that view the development of regional industries as a life cycle such as cluster life cycle models (Bergman Citation2008; Harris Citation2021; Menzel and Fornahl Citation2010) allow for the possibility of different episodes to follow each other but face criticism due to a certain determinism and neglect of context and agency (Martin and Sunley Citation2011; Stephens and Sandberg Citation2020; Trippl et al. Citation2015). The idea of an adaptive cluster life cycle that allows for different trajectories proposed by Martin and Sunley (Citation2011) further widens the concept. Though life cycle models and the path development literature are complementary (Benner Citation2020; Harris Citation2021), the comparability of forms of path development with life cycle stages is limited because path development does not presume any inherent cyclicality. Hence, in an adaptive conceptualization, path development may be better captured as a sequence with a potentially unlimited number of successive episodes linked by occasional transformation which can include various stages and dynamic processes of agency (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Boschma et al. Citation2017; Dawley Citation2014; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Miörner and Trippl Citation2017, Citation2019; Simmie Citation2012).

Path-as-process and the interplay of agency and structural conditions

Path development can be understood as a long-term sequence with successive episodes (Garud and Karnøe Citation2001; Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Simmie Citation2012). Martin’s (Citation2010) path-as-process model offers a long-term perspective on path development with different stages following each other. Instead of seeing path dependence as ‘canonical’ (p.4), this model defines path development as a process with different outcomes that can lead either to stasis and constrain the conditions for growth or to dynamic adaptation that enables further growth in a new round of path preformation, creation, and development (Martin Citation2010). In this sense, the model offers a non-deterministic long-term perspective of understanding sequences of path development.

The path-as-process model offers a simplified account of what happens at the end of a path development episode by either generating some form of renewal or decline (Martin Citation2010). In reality, the succession of different path development episodes is much more complex. As Blažek et al. (Citation2020, 1467) put it, ‘the evolutionary trajectory of a particular industry in a particular region might consist of multiple and swinging shifts.’ Given the possibility of path plasticity (Strambach and Halkier Citation2013), these shifts do not occur suddenly but are the outcome of gradual processes of path transformation (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019).

Path transformation is not a specific form of path development (Miörner and Trippl Citation2019). Rather, processes of path transformation occur every time a path transforms itself from one form into another. In a long-term perspective, these path transformations will occur occasionally and repeatedly, and what precisely goes on within these episodes is likely to be a contingent (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2003), agency-driven set of mechanisms (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Boschma et al. Citation2017; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019; Steen Citation2016).

The idea of path development as a process provides a larger frame for a focus on path transformation (Miörner and Trippl Citation2019). As Garud, Kumaraswamy, and Karnøe (Citation2010) argue, in contrast to the ontology behind canonical path dependence, a path-as-process perspective follows a contextualized ‘“insider’s” ontology’ (p.761), implying that it is less exogenous events or chance that lead to transformation but agents engaging in what Garud and Karnøe (Citation2001) call ‘mindful deviation’.Footnote2 Hence, path development and transformation are the results of the complex interplay between structure and agency (Archer Citation1982; Giddens Citation1984). Agency can be defined as ‘intentional, purposive and meaningful actions, and the intended and unintended consequences of such actions’ (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020, 707) and understood within the framework of Emirbayer and Mische’s (Citation1998) intertemporal activities of interpreting the past, imagining the future, and acting upon the conditions of the present (Grillitsch, Asheim, and Nielsen Citation2021a; Rekers and Stihl Citation2021; Steen Citation2016). Structure and agency are linked through practices (Giddens Citation1984; Sewell Citation1992; Stephens and Sandberg Citation2020) such as those conceptualized by Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) under the different forms of institutional work.

Following Garud and Karnøe’s (Citation2001) call for an agency-focused process perspective, Martin and Sunley (Citation2006) criticize the neglect of agency in the concept of path dependence. Still, the critical role of agency in transformation is not in the focus of Martin’s (Citation2010) path-as-process model which lacks an explanation for what precisely leads to the bifurcation towards either renewal or decline and notably for agency-driven processes of transformation (see also Dawley Citation2014). Hence, a long-term perspective that sees path development and transformation as subsequent and repeated episodes of evolution has to address the role of agency in relation to the socio-economic structure (Sewell Citation1992) in which agency takes place (Garud and Karnøe Citation2001).

Some contributions address the role of agency in the path-as-process perspective (e.g. Dawley Citation2014; Garud, Kumaraswamy, and Karnøe Citation2010; Simmie Citation2012). Bækkelund (Citation2021) argues that agency changes during path development and notably during critical junctures and conceptualizes the role of different forms of agency in Martin’s (Citation2010) model by placing specific forms of agency at a given stage. Still, it remains largely open how and why forms of agency evolve, succeed or compete with each other, and how they become dominant in a new mix of agency patterns that generates a new episode of path development.

As part of the methodological challenges to analysing agency they identify, Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta (Citation2021b) define a ‘main phase’ (309) in path development as an episode between critical junctures and stress that these critical junctures open possibilities for alternative development trajectories, while agency plays a role in shaping which one prevails. However, the challenge remains ‘to bring forth convincing explanations for why one path rather than another emerged’ (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b, 310).

Agency can take various forms that can combine (Bækkelund Citation2021; Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b). Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) argue that three interlocking types of agency (innovative entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship, place-based leadership) form a ‘trinity of change agency’. Following Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) and Henderson (Citation2020), Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen (Citation2020) add ‘structural maintenance’ agency that refers to ‘resisting novel activities and adapting to change incrementally’ (p.179). While this definition emphasizes the negative consequences of non-transformative agency (see also Baumgartinger-Seiringer Citation2021; Boschma et al. Citation2017), the related but apparently more positive term of reproductive agency can be understood to emphasize how agents contribute to stabilizing and entrenching development processes (Bækkelund Citation2021; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Nielsen Citation2021a). While their outcomes might differ, both maintenance and reproductive agency can be summarized as stability agency.

Lawrence and Suddaby’s (Citation2006) institutional work approach offers an umbrella over constructive and destructive forms of agency (Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2016; Kivimaa and Kern Citation2016) by defining a number of practices agents employ to interact in different ways with the structures surrounding them. These practices include, inter alia, constructive practices of advocacy, educating, or network creation, destructive ones of undermining assumptions, and stability-oriented ones of enabling or mythologizing (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006). Different constructive, destructive, and stability-oriented practices can exist, coexist, and compete in path development and transformation and create friction and contestation (Baumgartinger-Seiringer Citation2021; Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2021a; Boschma et al. Citation2017; Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020; Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2016; Kivimaa and Kern Citation2016; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019).

Agency in path development and transformation occurs in a context that includes structural conditions such as institutions or human and natural assets (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2021a; Chen Citation2021; Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Trippl et al. Citation2020). Changes in structural conditions enable new possibilities for agency, thus pre-defining critical junctures (Bækkelund Citation2021) and opening up ‘opportunity spaces’ (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020). Hence, the mix of agency at any given point in path development is the result of different, competing, and contested practices that aim at either constructive or destructive change or stability in a context of changing or stable structural conditions.Footnote3

A path discontinuity-development model

Combining the path-as-process perspective with repeated transformation due to changing patterns of agency and resulting in variegated forms of path development yields a model that builds on previous path-as-process conceptualizations (Bækkelund Citation2021; Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Martin Citation2010), puts a particular focus on the relationship between discontinuous ‘dramatic’ evolution on the one hand and gradual ‘developmental’ evolution on the other hand (Martin Citation2012, 184), and attempts to explain this relationship through agency patterns in their structural context with agents’ practices linking structure and agency. Such a model refines the analytical sequence between development episodes and critical junctures (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b) and draws on conceptualizations of path transformation (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019).

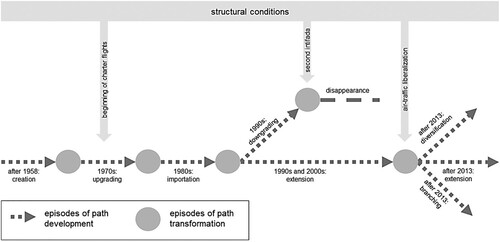

illustrates a stylized, hypothetical example of a path that includes episodes of positive and negative path development with occasional transformation.Footnote4 Hence, demonstrates the logic behind the discontinuity-development model. Apart from those forms of path development that lead to the emergence of a regional path (path creation and importation) or to its demise (path disappearance and delocalization), a discontinuity-development model understands all other forms of path development as temporary episodes that begin and end in transformation. Hence, the model follows the call for identifying development episodes and critical junctures between them to analyse the role of agency in them (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b). Parallel paths are subject to interpath relationships that can be competitive, supportive, or neutral (Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020; see also Benner Citation2021; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019).

Figure 1. A stylized example of the path discontinuity-development model. Source: author’s elaboration.

The path is affected by either changing or stable structural conditions (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2021a) that define the opportunity space for agency (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020), notably at critical junctures (Bækkelund Citation2021). At the same time, changing agency patterns during path transformation contributes to changes in structural conditions (Garud and Karnøe Citation2001), including by creating, modifying, reorienting, recombining, or destroying assets (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Chen Citation2021; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019; Trippl et al. Citation2020). This is why structural conditions and notably assets are ‘both the outcome of previous rounds of regional economic development and the platform for future ones’ (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b, 178).

In contrast to life cycle models (e.g. Bergman Citation2008; Harris Citation2021; Menzel and Fornahl Citation2010), a discontinuity-development model does not imply any pre-defined regularity in the sequence of episodes. Instead, the model assumes, first, that episodes of path development will at some point be succeeded by transformation and, second, that path development and transformation will often follow the stages of initiation by pioneers, acceleration by further agency, and consolidation through a critical mass (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Bergman Citation2008; Menzel and Fornahl Citation2010; Simmie Citation2012). Given the ontology of a path-as-process model that places agency in the centre of evolution (Garud, Kumaraswamy, and Karnøe Citation2010), the model regards changing agency patterns as the fundamental mechanism behind the succession of path development and transformation episodes, drawing on Bækkelund (Citation2021) who addresses the role of different forms of agency in the phases of the path-as-process model and acknowledges gradual shifts between them. What happens during path transformation is different forms of agency evolving, emerging, and possibly competing in contested processes and subject to power relations (Baumgartinger-Seiringer Citation2021; Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2021a; Boschma et al. Citation2017; Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020; Miörner Citation2020; Miörner and Trippl Citation2017, Citation2019). Structural conditions can either be stable or change, thus providing opportunity spaces for different agency patterns. Agency and structure are linked through concrete practices. These practices include those enumerated by Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) for institutional workFootnote5 which are understood here in a more generic sense that goes beyond the strictly institutional level and encompasses change agency forms such as innovative entrepreneurship or place-based leadership in addition to institutional entrepreneurship as well as maintenance and reproductive agency.Footnote6 For the remainder of this article, these agency patterns are simplified as constructive and destructive agency and stability agency.Footnote7

proposes a heuristic for how practices of institutional work can be used in different agency patterns under either changing or stable structural conditions and how they can contribute to path development or transformation, thus providing a lens for what happens within the episodes in the model.

Table 1. Agency patterns and practices in the path discontinuity-development model.

As illustrates, many practices of constructive change agency can facilitate transformation under changing structural conditions while some of them can increase pressures for transformation under stable structural conditions. Practices of destructive change agency can facilitate transformation (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Kivimaa and Kern Citation2016) but can also reinforce forms of gradual path development that will often be negative (Blažek et al. Citation2020). As for stability agency, some practices can contribute to gradual development despite changing structural conditions while others will be more apt under stable structural conditions.

While the model offers a heuristic for empirical research on the long-term sequence of path development and transformation, several caveats are necessary. First, due to the ‘duality of structure’ (Giddens Citation1984), whether structural conditions change or remain stable is not exogenous but can, at least in part, be a result of the agency patterns described in . The interplay of structure and agency is related to the temporality under analysis (Archer Citation1982; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Nielsen Citation2021a) which has to be considered in a long-term perspective. Second, the heuristic propositions made in do not imply any determinism but have to be seen in a contingent and contextual way (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2003). Despite its simplifications, the model can help focus empirical attention on the long-term nature of path development with its sequence of gradual change and radical transformation and on the concrete practices driving changes in agency patterns between episodes, as the empirical vignette in the next section illustrates.

Empirical vignette: tourism in Eilat, Israel

The empirical vignette sketches the path tourism in Eilat, Israel’s Red Sea resort, witnessed over more than six decades. The most recent episode analysed is the path transformation and resulting incipient path development after the aviation agreement signed in 2013 that liberalized air traffic between Israel and the European Union (Benner Citation2022; Reich Citation2015) until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020.

This vignette is meant as a paradigmatic single-case study (Flyvberg Citation2006) that draws on empirical material gathered during a preceding research effort (Benner Citation2022) and recoded and reinterpreted here in view of path development through the lens of the discontinuity-development model. The case study builds on 20 semi-structured interviews with tourism stakeholders and experts (Helfferich Citation2019) from Israel performed either on the phone or in internet calls between February and November 2020, in some instances supplemented by written clarifications.Footnote8 Interviewees included representatives of tourism businesses, non-profit tourism serviceproviders, and intermediary or destination management organizations, as well as experts familiar with tourism development in Israel. Interviewee selection was in part based on other interviewees’ recommendations, thus pursuing ‘snowball sampling’ (Goodman Citation1961), but where necessary to find further interviewees and to find entry points for snowballing also drew on Israeli media coverage (e.g. podcast or television reports on recent developments in tourism in Eilat and the Negev). Interviews loosely followed a short interview guideline that included largely open questions to direct and structure the interview course when needed (Helfferich Citation2019). As the interview series progressed, the guideline was modified and extended where appropriate, and in its final version (see Annex 1) included, inter alia, questions related to recent tendencies in tourism in the region and challenges to it, the effect of the aviation agreement and the new airport, the development of new tourism models, patterns of cooperation between tourism agents, and interviewees’ outlook on tourism development in Eilat and the Negev. The total interview time was more than 13 h and 45 min. Since all interviewees consented to being recorded, all interviews were taped and transcribed.Footnote9 Coding was based on a deductive coding structure (Mayring and Fenzl Citation2019) that drew on insights from the literature on Eilat’s tourism history (see Annex 2). Coding was carried out with qualitative data analysis software (Kuckartz and Rädiker Citation2019).

Since the interviews allow primarily for analysing more recent developments, to redraw the sector’s long-term history the empirical vignette relies primarily on available literature on the development of Eilat and its tourism sector. While the number of studies about Eilat is limited, those that are available still provide a consistent picture that allows for checking the plausibility and robustness of the insights gained from the interviews, and they complete the picture of the sector’s long-term history throughout the decades at least to a sufficient degree to illustrate the application of the model. Together, information from both the interviews and available literature on the history of Eilat’s tourism sector allow for an approximate analysis of a six-decade sequence. The identification of practices relies on the interview data and focuses on the recent episode since 2013.

The vignette is meant only to illustrate the logic of the model as an inspiration for further, comprehensive empirical research and to elucidate methodological challenges related to the model’s application. By describing separate episodes of path development, the vignette draws inspiration from the idea of temporal bracketing which views episodes as analytical abstractions replicating each other in a single-case research design over time (Langley Citation1999).

Eilat’s tourism historyFootnote10

Eilat is a young city with about 50,000 inhabitants that came into existence only after 1949 on the site of an outpost taken by the Israeli army at the end of the 1948–1949 war after the founding of the State of Israel (Azaryahu Citation2005; Ergas and Felsenstein Citation2012; Gradus Citation2001; Kliot Citation1997; Mansfeld Citation2001; Stylidis, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2015, Citation2017). In the early 1950s, Eilat became a port city, driven in part by geopolitical developments such as the Sinai war of 1956 and the subsequent lifting of the blockade by Egypt (Azaryahu Citation2005; Gradus Citation2001; Kliot Citation1997; Zerubavel Citation2019). Later, the city became an oil pipeline terminus and came to rely on mines in the region (Gradus Citation2001).

1958 to late 1960s: path creation of liminal domestic tourism

Eilat’s location on the Gulf of Aqaba offers a variety of advantages for tourism such as a year-long warm climate, proximity to the Negev desert and its natural and archeological sites, and the coral reefs off the shore (Azaryahu Citation2005; Cohen-Hattab and Shoval Citation2004; Gradus Citation2001; Kliot Citation1997; Mansfeld Citation2001; Schmidt and Altshuler Citation2021; Shaari Citation1973; Stylidis, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2015; Zerubavel Citation2019). Eilat’s era as a domestic tourist destination started in 1958 when the new road through the Negev made it accessible from the densely populated centre of the country (Azaryahu Citation2005; Zerubavel Citation2019) but tourism development remained limited into the 1960s (Mansfeld Citation2001). Soon after its foundation and up until the 1960s, Eilat became engrained in Israeli popular imagination as a site for relaxation with a natural beauty and a liminal character and came to represent ‘a substitute to travel abroad’ (Azaryahu Citation2005, 121) and a liminal place attractive to international non-conformist hippie youths (Azaryahu Citation2005; Belhassen Citation2012; Kaplan Citation2020; Zerubavel Citation2019).

1970s: path upgrading towards international tourism

Eilat’s status in Israeli imagination as ‘the beach at the end of the world’ (Azaryahu Citation2005) was lost to a certain degree after the 1967 war to Sinai (Azaryahu Citation2005; Hazbun Citation2008; Noy and Cohen Citation2005; Shaari Citation1973; Zerubavel Citation2019). Notably during the 1970s, Israel’s tourism policy redirected its attention from the Mediterranean coastal resorts towards making Eilat ‘a major winter-sun destination for European tourists’ (Hazbun Citation2008, 94) and promoting international investment there, as well as towards tourism in the Dead Sea area and the Sea of Galilee (Cohen-Hattab and Shoval Citation2004; Givton Citation1973; Hazbun Citation2008; Mansfeld Citation2001; Shaari Citation1973). Eilat’s growth into a sun, sand, and sea destination for European tourists was underpinned by the setup of charter flights that started in 1975 (Azaryahu Citation2005; Hazbun Citation2008; Mansfeld Citation2001; Zerubavel Citation2019).

The policy focus on promoting Eilat as a sun, sand, and sea destination for European tourists was driven by objectives of diversifying the country’s export base and generating foreign exchange revenues, seizing Eilat’s climatic advantages as one of few winter destinations close to European markets, and softening the local economic impact of the closure of regional mines (Achituv Citation1973; Blizovsky Citation1973; Givton Citation1973; Gradus Citation2001; Mansfeld Citation2001; Shaari Citation1973). The government promoted tourism development in the city through infrastructure investments, allocation of state-owned land to national and international investors, and financial incentives (Blizovsky Citation1973; Federmann Citation1973; Krakover Citation2004; Mansfeld Citation2001; Shaari Citation1973).

1980s: path importation of large-scale mass tourism

On the domestic market, Eilat’s transformation into a mass tourism destination largely replaced the 1960s’ to 1970s’ beach camping of nonconformist youth which reflected the changing preferences and rising purchasing power of Israeli tourists (Azaryahu Citation2005; Belhassen Citation2012; Cohen-Hattab and Shoval Citation2004), although the city kept a certain romantic image up to the 1980s (Kaplan Citation2020). Mansfeld (Citation2001) describes how this policy led to an expansion of supply, notably through the emergence of the national Isrotel chain backed by a British investor with experience in the Spanish hotel market which since the early 1980s built a series of large-scale hotels on the marina that became the core of Eilat’s tourism zone (Isrotel Citationn.d.).

After 1982 when Israel’s pull-out from Sinai was completed, Eilat again turned into the country’s liminal ‘frontier town’ (Azaryahu Citation2005, 119), although neighbouring Taba was disputed for several more years and handed over to Egypt after international arbitration in 1989 (Hazbun Citation2008; Kemp and Ben-Eliezer Citation2000). In 1985, the Israeli government granted Eilat a special status as a free zone that brought with it exemption from value-added tax (Gradus Citation2001) and customs which further reinforced Eilat’s liminal image (Azaryahu Citation2005). Legislation passed in 1988 provided for financial incentives for young people discharged from military service when working in hotels for a limited time which led to an influx of workers to Eilat (Belhassen Citation2012; Belhassen and Shani Citation2012; Mansfeld Citation2001; Stylidis, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2015).

1990s and 2000s: path downgrading of international tourism and extension of domestic tourism

During the 1990s, the Fordist model of standardized sun, sand, and sea tourism (Hazbun Citation2008) in Eilat was further entrenched by large-scale tourism development and investment as the city’s hotel room capacity doubled (Mansfeld Citation2001; Zerubavel Citation2019; see also Krakover Citation2004). Mansfeld (Citation2001, 172) considers the massive expansion in Eilat’s hotel capacity during the 1990s ‘an uncontrolled development process’ that resulted in low unemployment at the time but also in disadvantageous long-term effects such as massive dependence on tourism and particularly on low-skilled and low-paid jobs, social problems, inward and outward migration, environmental damage, a certain degree of antagonism, and a reputation of a lower quality of life (Azaryahu Citation2005; Belhassen Citation2012; Belhassen and Shani Citation2012; Kaplan Citation2020; Kliot Citation1997; Mansfeld Citation2001; Schmidt and Altshuler Citation2021; Stylidis, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2015, Citation2017). The consequences of uncontrolled development included a loss of attractiveness to international tourists due to dissatisfaction with service quality, the limited choice of attractions, and the perception ‘that Eilat looks more like a building site than a tourist destination’ (Mansfeld Citation2001, 176), a problem an interviewee mentioned even about present-day Eilat. Further, environmental degradation caused the exit of German tour operators during the 1990s (Mansfeld Citation2001).

In the wake of the 1994 peace agreement between Israel and Jordan, ambitious plans for regional cross-border tourism cooperation between Eilat and neighbouring Aqaba including a joint airport, theme parks, or a casino emerged but did not materialize (Gradus Citation2001; Hazbun Citation2008; Kliot Citation1997; Mansfeld Citation2001). Eilat’s 1990s boom in large-scale sun, sand, and sea tourism lasted until the breakdown of international tourism to Israel caused by the second ‘intifada’ in 2000 (Cohen-Hattab and Shoval Citation2004; Hazbun Citation2008; Israeli and Reichel Citation2003; Zerubavel Citation2019).

While Eilat’s tourism sector generally relied both on domestic and international tourism during the 1980s and 1990s (Ergas and Felsenstein Citation2012; Krakover Citation2004; Mansfeld Citation2001), in the early 2000s Eilat turned into a primarily domestic destination with domestic tourists accounting for about 85 percent of total visitors in 2010 (Ergas and Felsenstein Citation2012; see also Belhassen and Shani Citation2012; Stylidis, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2015, Citation2017). When international tourism broke down and international hotel chains left Eilat, Israel’s tourism policy turned away from supporting international package and charter tourism to Eilat. Among Israelis, Eilat kept its position as a holiday ‘counter-place’ (Zerubavel Citation2019, 113) far away from daily life in the densely populated centre of the country (Azaryahu Citation2005; Belhassen Citation2012; Belhassen and Shani Citation2012; Kaplan Citation2020; Stylidis, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2015).

After 2013: path diversification and branching towards niche tourism and extension of domestic mass tourism

The period after 2010 is marked by the impact of the aviation agreement between the EU and Israel liberalizing air traffic that was signed in 2013 and implemented until 2018 (European Commission Citation2021; Reich Citation2015) and the recovery of international tourism to Israel after the 2014 Gaza war. The liberalization lowered airfares not only for incoming European tourists but also for outgoing Israeli tourists. To promote international tourism to Eilat, the government started subsidizing flights to Eilat’s airports, an incentive that was initially co-funded by the local hotel association, and began widening its focus in international tourism marketing from Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to include Eilat and the Negev. However, while the subsidization policy did attract a number of European airlines, the impact on Eilat’s tourism sector is generally regarded by interviewees as disappointing because a significant part of arriving tourists are believed to move on to other destinations in Israel or neighbouring countries or to resort to low-price apartments or other accommodation options.

Eilat’s small inner-city airport used mainly for domestic flights due to its limited capacity and inadequacy for international aviation and the civilian part of the Ovda airbase used mainly for international flights were replaced by the new Ramon airport located north of Eilat designed to accommodate larger aircraft and to increase the capacity for arrivals by air (Ergas and Felsenstein Citation2012; Gradus Citation2001; Stylidis, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2015, Citation2017). Both the subsidization of flights and the opening of the Ramon airport can be understood as vesting practices by policymakers.

To increase Eilat’s appeal to international tourists, tourism policymakers over time initiated a wide range of festivals and hosted sports events as an expression of enabling practices. Special-interest niches targeted include bird-watching tourism driven by an international research centre located in the region and Eilat’s favourable location along the routes of migrating birds. Interviewees mentioned embedding Eilat into a wider regional tourism product that includes the Sinai, Aqaba and Petra, and the Negev, although regional tours have been offered before (Gradus Citation2001; Hazbun Citation2008; Mansfeld Citation2001; Shaari Citation1973; Zerubavel Citation2019). The recent market entry of a national hostel chain and tour operator to Eilat that offers tours to the wider region seems to have given an impetus to this path. In contrast to the package tour, charter flight model dominant from the 1970s to the 1990s, this path targets young, international independent tourists and backpackers likely to use low-cost carriers and accommodation and to combine a beach vacation with small-scale, community-based tours (see also Noy and Cohen Citation2005). According to one interviewee, ‘the concept was again to create a hub for independent travellers in the city centre of Eilat, to have a lot of activities, a lot of day tours, multi-day tours, packages that will depart from [the hostel]’ (interview #17, 2020), echoing a practice of theorizing that centres on active travellers who benefit a wider range of tourism businesses in Eilat and the region. Consequently, network construction is a major practice behind the constructive change agency in this model:

The [hostel/tour operator] did the tour in the kibbutzim and they had a tour that started in the Red Canyon and then kibbutz Neot Smadar, Kibbutz Yotvata, and Kibbutz Ketura. (…) It’s good for everybody. (interview #8, 2020)

It was very difficult to find [a] hostel or such a building which is not in the Northern beach because they didn’t want to be there with all these big hotels. (interview #1, 2020)

The network construction practice behind this form of constructive agency stands in stark contrast to the deterring of cooperation involved in the integrated large-scale mass tourism model. According to one interviewee, in this model cooperation ‘wouldn’t happen so because when the hotel is sending someone out of the hotel, it’s going to lose the beer money, the lounge money, and the foods money’ (interview #13, 2020).

Still, the largely domestic sun, sand, and sea mass tourism path prevails. While the COVID-19 pandemic was not in the scope of the present study, an interviewee mentioned that limited possibilities for international travel in 2020 strengthened domestic tourism to Eilat (see also Schmidt and Altshuler Citation2021). Further, interviewees indicated that despite some signs of downgrading, domestic demand for Eilat has not suffered much from the increased international competition in the wake of the aviation agreement because, first, lower airfares enabled Israelis to travel more, second, domestic tourism offers advantages hard to find abroad such as the availability of kosher food, and third, visits to Eilat remain in part linked to trade union vacation offers, corporate incentives, or conferences. The latter two reasons offer cases of embedding of the mass tourism model into wider social practices that account in part for its path extension.

Discussion

While a precise historical account of events contributing to the long-term development of Eilat’s tourism sector is beyond the scope of this article, represents this sequence as a stylized long-term path. Because of difficulties in precisely distinguishing and delimiting patterns of agency, path development forms, and path transformation stages empirically due to the idealized nature of these analytical categories (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021b; Blažek et al. Citation2020; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020; Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020; Miörner and Trippl Citation2019), necessarily involves stylization and interpretation that depends on judgments about the degree of path development processes and agency patterns and limits the influence of structural conditions to major changes for the sake of simplicity.

Under the changing structural conditions of air-traffic liberalization and airport relocation, constructive change agency is particularly visible through practices of enabling, identity construction, network construction, theorizing, and vesting for path diversification and branching towards niche tourism. As for the path extension of domestic sun, sand, and sea tourism, the deterring of cooperation inherent to the integrated, large-scale mass tourism model as well as the embedding of the model in wider social practices represent practices associated with stability agency. Hence, the propositions about the role of agency patterns and practices included in are generally confirmed, although the examples show that borders between agency patterns and between changing or stable structural conditions are fluid and the heuristic categorization in primarily serves as an approximation. Further, not all practices are easily distinguishable and some of them overlap.

While it seems too early to evaluate interpath relationships between the paths evolving since 2013, a plausible presumption is that the branching path towards special-interest tourism and the diversifying path towards a small-scale collaborative regional tourism model support each other, but how they relate to the extending path of large-scale domestic tourism over time remains to be seen.

Methodologically, the path development episodes described suggest how temporal bracketing (Langley Citation1999) might be useful in more comprehensive future long-term path development case studies. In particular, the method’s focus on agency makes it suited for evolutionary empirical research on the role of agency in critical junctures (Langley Citation1999; Stephens and Sandberg Citation2020). Due to its methodological limitations, the Eilat case as presented here can be seen primarily as an illustration of the discontinuity-development model and highlights the difficulty in pursuing a long-term analytical perspective towards regional evolution. Reconstructing changing patterns of agency during past episodes in more detail than could be done in this article is fraught with challenges (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b) and requires adding methodological competences in economic history to the toolbox of evolutionary economic geography (Henning Citation2019). For example, two studies drawn on (Azaryahu Citation2005; Zerubavel Citation2019) offer excellent examples for reconstructing historical processes by drawing on long-term media discourses (see also Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b), and Henn and Laureys (Citation2010) provide an instructive example of a historical cluster case study by drawing on archival materials. However, qualitatively redrawing the long-term history of regional industrials paths risks rationalizing events ex-post and selectively interpreting them (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b; Henning Citation2019; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020; Steen Citation2016). This is another reason why understanding changing patterns of agency and related practices in path development and transformation is important. In particular, if we can sharpen our understanding of which changes in agency patterns and which practices are likely to induce path transformation, our methods in observing path development as it happens (Steen Citation2016) could significantly improve. Further, combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a long-term perspective appears promising (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021b).

Outlook

This article sought to demonstrate the merit of understanding path development and transformation as a long-term sequence of discontinuity and development. By showing that shifts in agency do not occur automatically at any stage but are related to the dynamics of the agent scene and to the precise practices employed under particular structural conditions, the article contributes a more nuanced perspective to pre-existing path-as-process conceptualizations (e.g. Bækkelund Citation2021; Martin Citation2010).

However, more in-depth empirical work is necessary to refine the changing patterns of agency and related practices illustrated in to distinguish in more detail how and under which conditions path transformation leads to a specific subsequent form of path development and not to others, and how they drive the various stages of transformation. In particular, why changes of agency patterns occur and how their occurrence varies merits further research that could benefit from combining agency approaches with other explanations. While much needs to be done to fully understand the role of agency in regional evolution, the discontinuity-development model provides a framework for embedding specific patterns of agency and practices more closely into conceptualizations of regional industrial path development and can help refine empirical research designs.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (145.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Empirical research reported in this paper began while the author was employed at Heidelberg University. The author is grateful to Michaela Trippl and Simon Baumgartinger-Seiringer for valuable discussions and suggestions. Research for this paper was presented at the online Modul University research colloquium in March 2021 and at the online International Conference on Cluster Research ‘Rethinking Clusters’ in September 2021. The author is grateful for suggestions and comments given by participants and in particular to Robert Hassink for drawing his attention to the importance of interpath relationships. Last but not least, the author is grateful for constructive comments given by anonymous reviewers, and to the editor, Philip Cooke. Of course, all remaining errors and omissions are the author’s alone, as are the opinions expressed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for drawing my attention to the points mentioned in this paragraph.

2 I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for drawing my attention to these ontological differences.

3 I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for drawing my attention to the points mentioned in this paragraph.

4 The example of a path given in does not imply any determinism. The path is the result of evolutionary dynamics as they unfold that can be analyzed and redrawn only later.

5 For examples of path development studies that similarly draw on institutional work practices, see Fuenfschilling and Truffer (Citation2016) and Binz and Gong (Citation2021).

6 For the original definitions of each practice of institutional work, see Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006), and for a further detailed discussion, see Fuenfschilling and Truffer (Citation2016). For , Lawrence and Suddaby’s (Citation2006) enumeration of institutional work practices has been slightly adapted.

7 I am grateful to anonymous reviewers for drawing my attention to various points mentioned in this paragraph.

8 This sample is part of a slightly larger sample that covers a wider region and that was analyzed with a different research question in Benner (Citation2022).

9 Where interviewees are quoted directly, the readability has been enhanced through minor language corrections.

10 This sub-section in part draws on Benner (Citation2022) and Benner et al. (Citation2017).

References

- Achituv, G. 1973. “The European Potential.” In The Second Million: Israel Tourist Industry Past-Present-future, edited by C. H. Klein, 67–74. Jerusalem: Amir.

- Archer, M. 1982. “Morphogenesis Versus Structuration: On Combining Structure and Action.” The British Journal of Sociology 33: 455–483. doi:10.2307/589357

- Azaryahu, M. 2005. “The Beach at the End of the World: Eilat in Israeli Popular Culture.” Social & Cultural Geography 6: 117–133. doi:10.1080/1464936052000335008

- Bækkelund, N. 2021. “Change Agency and Reproductive Agency in the Course of Industrial Path Evolution.” Regional Studies 55: 757–768. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291

- Bathelt, H., and J. Glückler. 2003. “Toward a Relational Economic Geography.” Journal of Economic Geography 3: 117–144. doi:10.1093/jeg/3.2.117

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S. 2021. “The Role of Powerful Incumbent Firms: Shaping Regional Industrial Path Development through Change and Maintenance Agency.” Papers in Economic Geography and Innovation Studies 2021/07. Wien: PEGIS.

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., L. Fuenfschilling, J. Miörner, and M. Trippl. 2021a. “Reconsidering Regional Structural Conditions for Industrial Renewal.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1984419.

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., J. Miörner, and M. Trippl. 2021b. “Towards a Stage Model of Regional Industrial Path Transformation.” Industry and Innovation 28: 160–181. doi:10.1080/13662716.2020.1789452

- Beer, A., T. Barnes, and S. Horne. 2021. “Place-based Industrial Strategy and Economic Trajectory: Advancing Agency-Based Approaches.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1947485.

- Belhassen, Y. 2012. “Eilat Syndrome: Deviant Behavior among Temporary Hotel Workers.” Tourism Analysis 17: 673–677. doi:10.3727/108354212X13485873914083

- Belhassen, Y., and A. Shani. 2012. “Hotel Workers’ Substance use and Abuse.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 31: 1292–1302. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.03.011

- Benner, M. 2020. “The Decline of Tourist Destinations: An Evolutionary Perspective on Overtourism.” Sustainability 12 (9): 1–14, 3653. doi:10.3390/su12093653

- Benner, M. 2021. “Retheorizing Industrial-Institutional Coevolution: A Multidimensional Perspective.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1949441.

- Benner, M. 2022. “A Tale of Sky and Desert: Translation and Imaginaries in Transnational Windows of Institutional Opportunity.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 128: 181–191. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.12.019

- Benner, M., M. Dollinger, E. Gliesner, and R. Pelz. 2017. “Upgrading a Tourism Cluster: The Case of Eilat.” MPRA Paper No. 81183. Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

- Bergman, E. 2008. “Cluster Life Cycles: An Emerging Synthesis.” In Handbook of Research on Cluster Theory, edited by C. Karlsson, 114–132. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Binz, C., and H. Gong. 2021. “Legitimation Dynamics in Industrial Path Development: New-to-the-World Versus New-to-the-region Industries.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1861238.

- Blažek, J., V. Květoň, S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, and M. Trippl. 2020. “The Dark Side of Regional Industrial Path Development: Towards a Typology of Trajectories of Decline.” European Planning Studies 28: 1455–1473. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1685466

- Blizovsky, Y. 1973. “The Role of Tourism in the Economy.” In The Second Million: Israel Tourist Industry Past-present-Future, edited by C. H. Klein, 107–129. Amir.

- Boschma, R., L. Coenen, K. Frenken, and B. Truffer. 2017. “Towards a Theory of Regional Diversification: Combining Insights from Evolutionary Economic Geography and Transition Studies.” Regional Studies 51: 31–45. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Chen, Y. 2021. “Rethinking Asset Modification in Regional Industrial Path Development: Toward a Conceptual Framework.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1941839.

- Cohen-Hattab, K., and N. Shoval. 2004. “The Decline of Israel’s Mediterranean Resorts: Life Cycle Change Versus National Tourism Master Planning.” Tourism Geographies 6: 59–78. doi:10.1080/14616680320001722337

- Dawley, S. 2014. “Creating New Paths? Offshore Wind, Policy Activism, and Peripheral Region Development.” Economic Geography 90: 91–112. doi:10.1111/ecge.12028

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103: 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294

- Ergas, Y., and D. Felsenstein. 2012. “Airport Relocation and Expansion and the Estimation of Derived Tourist Demand: The Case of Eilat, Israel.” Journal of Air Transport Management 24: 54–61. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2012.06.005

- European Commission. 2021. International aviation: Israel. Accessed February 15, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/air/international_aviation/country_index/israel_en.

- Federmann, S. 1973. “The Hotel Sector.” In The Second Million: Israel Tourist Industry Past-present-future, edited by C. H. Klein, 194–203. Jerusalem: Amir.

- Flyvberg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12: 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363

- Frangenheim, A., M. Trippl, and C. Chlebna. 2020. “Beyond the Single Path View: Interpath Dynamics in Regional Contexts.” Economic Geography 96: 31–51. doi:10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Fuenfschilling, L., and B. Truffer. 2016. “The Interplay of Institutions, Actors and Technologies in Socio-Technical Systems — an Analysis of Transformations in the Australian Urban Water Sector.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 103: 298–312. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.023

- Garud, R., and P. Karnøe. 2001. “Path Creation as a Process of Mindful Deviation.” In Path Dependence and Creation, edited by R. Garud, and P. Karnøe, 1–38. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Garud, R., A. Kumaraswamy, and P. Karnøe. 2010. “Path Dependence or Path Creation?” Journal of Management Studies 47: 760–774. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00914.x

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge, Malden: Policy Press.

- Givton, H. 1973. “The Second Million.” In The Second Million: Israel Tourist Industry Past-present-future, edited by C. H. Klein, 266–283. Jerusalem: Amir.

- Goodman, L. 1961. “Snowball Sampling.” The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 32: 148–170. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177705148

- Gradus, Y. 2001. “Is Eilat-Aqaba a bi-national City? Can Economic Opportunities Overcome the Barriers of Politics and Psychology.” GeoJournal 54: 85–99. doi:10.1023/A:1021196800473

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and H. Nielsen. 2021a. “Temporality of Agency in Regional Development.” European Urban and Regional Studies, doi:10.1177/096977642110288.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and M. Trippl. 2018. “Unrelated Knowledge Combinations: The Unexplored Potential for Regional Industrial Path Development.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11: 257–274. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy012

- Grillitsch, M., J. Rekers, and M. Sotarauta. 2021b. “Investigating Agency: Methodological and Empirical Challenges.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership. Cheltenham, edited by M. Sotarauta, and A. Beer, 302–323. Northampton: Elgar.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44: 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870

- Harris, J. 2021. “Rethinking Cluster Evolution: Actors, Institutional Configurations, and New Path Development.” Progress in Human Geography 45: 436–454. doi:10.1177/0309132520926587

- Hassink, R., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of New Regional Industrial Path Development.” Regional Studies 53: 1636–1645. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hazbun, W. 2008. Beaches, Ruins, Resorts: The Politics of Tourism in the Arab World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Helfferich, C. 2019. “Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews.” In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, edited by N. Baur, and J. Blasius, 669–686, 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Henderson, D. 2020. “Institutional Work in the Maintenance of Regional Innovation Policy Instruments: Evidence from Wales.” Regional Studies 54: 429–439. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1634251

- Henn, S., and E. Laureys. 2010. “Bridging Ruptures: The Re-emergence of the Antwerp Diamond District After World War II and the Role of Strategic Action.” In Emerging Clusters: Theoretical, Empirical and Political Perspectives on the Initial Stage of Cluster Evolution. Cheltenham, edited by D. Fornahl, S. Henn, and M. P. Menzel, 74–95. Northampton: Elgar.

- Henning, M. 2019. “Time Should Tell (More): Evolutionary Economic Geography and the Challenge of History.” Regional Studies 53: 602–613. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1515481

- Isaksen, A. 2015. “Industrial Development in Thin Regions: Trapped in Path Extension?” Journal of Economic Geography 15: 585–600. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu026

- Isaksen, A., S. Jakobsen, R. Njøs, and R. Normann. 2019. “Regional Industrial Restructuring Resulting from Individual and System Agency.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32: 48–65. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Isaksen, A., F. Tödtling, and M. Trippl. 2018. “Innovation Policies for Regional Structural Change: Combining Actor-Based and System-Based Strategies.” In New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems: Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons, edited by A. Isaksen, R. Martin, and M. Trippl, 221–238. Cham: Springer.

- Israeli, A., and A. Reichel. 2003. “Hospitality Crisis Management Practices: The Israeli Case.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 22: 353–372. doi:10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00070-7

- Isrotel. n.d. About Isrotel. Accessed May 18, 2021. https://www.isrotel.com/about-isrotel-footer/about-isrotel/about-isrotel

- Jolly, S., M. Grillitsch, and T. Hansen. 2020. “Agency and Actors in Regional Industrial Path Development. A Framework and Longitudinal Analysis.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111: 176–188. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013

- Kaplan, D. 2020. “Porn Tourism and Urban Renewal: The Case of Eilat.” Porn Studies 7: 459–473. doi:10.1080/23268743.2020.1764860

- Kemp, A., and U. Ben-Eliezer. 2000. “Dramatizing Sovereignty: The Construction of Territorial Dispute in the Israeli-Egyptian Border at Taba.” Political Geography 19: 315–344. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(99)00078-5

- Kivimaa, P., and F. Kern. 2016. “Creative Destruction or Mere Niche Support? Innovation Policy Mixes for Sustainability Transitions.” Research Policy 45: 205–217. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2015.09.008

- Kliot, N. 1997. “The Grand Design for Peace: Planning Transborder Cooperation in the Red Sea.” Political Geography 16: 581–603. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(96)00061-3

- Krakover, S. 2004. “Tourism Development – Centres Versus Peripheries: The Israeli Experience During the 1990s.” International Journal of Tourism Research 6: 97–111. doi:10.1002/jtr.473

- Kuckartz, U., and S. Rädiker. 2019. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MaxQDA: Text, Audio, and Video. Cham: Springer.

- Langley, A. 1999. “Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data.” Academy of Management Review 24: 691–710. doi:10.5465/amr.1999.2553248

- Lawrence, T., and R. Suddaby. 2006. “Institutions and Institutional Work.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organization Studies, edited by S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, and W. R. Nord, 2nd ed., 215–254. London: SAGE.

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95: 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Mansfeld, Y. 2001. “Acquired Tourism Deficiency Syndrome: Planning and Developing Tourism in Israel.” In Mediterranean Tourism: Facets of Socioeconomic Development and Cultural Change, edited by Y. Apostolopoulos, P. Loukissas, and L. Leontidou, 159–178. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Martin, R. 2010. “Roepke Lecture in Economic Geography-Rethinking Regional Path Dependence: Beyond Lock-in to Evolution.” Economic Geography 86: 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R. 2012. “(Re)Placing Path Dependence: A Response to the Debate.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36: 179–192. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01091.x

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of Economic Geography 6: 395–437. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2011. “Conceptualizing Cluster Evolution: Beyond the Life Cycle Model?” Regional Studies 45: 1299–1318. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.622263

- Mayring, P., and T. Fenzl. 2019. “Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse.” In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, edited by N. Baur, and J. Blasius, 2nd ed., 633–648. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Menzel, M., and D. Fornahl. 2010. “Cluster Life Cycles – Dimensions and Rationales of Cluster Evolution.” Industrial and Corporate Change 19: 205–238. doi:10.1093/icc/dtp036

- Miörner, J. 2020. “Contextualizing Agency in new Path Development: How System Selectivity Shapes Regional Reconfiguration Capacity.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1854713.

- Miörner, J., and M. Trippl. 2017. “Paving the Way for New Regional Industrial Paths: Actors and Modes of Change in Scania’s Games Industry.” European Planning Studies 25: 481–497. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1212815

- Miörner, J., and M. Trippl. 2019. “Embracing the Future: Path Transformation and System Reconfiguration for Self-Driving Cars in West Sweden.” European Planning Studies 27: 2144–2162. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1652570

- Noy, C., and E. Cohen. 2005. “Introduction: Backpacking as a Rite of Passage in Israel.” In Israeli Backpackers: From Tourism to Rite of Passage, edited by C. Noy, and E. Cohen, 1–43. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Reich, A. 2015. “The European Neighbourhood Policy and Israel: Achievements and Disappointments.” Journal of World Trade 49: 619–642.

- Rekers, J., and L. Stihl. 2021. “One Crisis, one Region, Two Municipalities: The Geography of Institutions and Change Agency in Regional Development Paths.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 124: 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.012

- Schmidt, J., and A. Altshuler. 2021. “The Israeli Travel and Tourism Industry Faces COVID-19: Developing Guidelines for Facilitating and Maintaining a Nuanced Response and Recovery to the Pandemic.” Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, doi:10.1108/WHATT-01-2021-0016.

- Sewell, W., Jr. 1992. “A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation.” American Journal of Sociology 98: 1–29. doi:10.1086/229967

- Shaari, Y. 1973. “Regional Development.” In The Second Million: Israel Tourist Industry Past-Present-Future, edited by C. H. Klein, 130–145. Jerusalem: Amir.

- Simmie, J. 2012. “Path Dependence and New Technological Path Creation in the Danish Wind Power Industry.” European Planning Studies 20: 753–772. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.667924

- Sotarauta, M., N. Suvinen, S. Jolly, and T. Hansen. 2021. “The Many Roles of Change Agency in the Game of Green Path Development in the North.” European Urban and Regional Studies 28: 92–110. doi:10.1177/0969776420944995

- Steen, M. 2016. “Reconsidering Path Creation in Economic Geography: Aspects of Agency, Temporality and Methods.” European Planning Studies 24: 1605–1622. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Stephens, A., and J. Sandberg. 2020. “How the Practice of Clustering Shapes Cluster Emergence.” Regional Studies 54: 596–609. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1667967

- Strambach, S., and H. Halkier. 2013. “Reconceptualizing Change: Path Dependency, Path Plasticity and Knowledge Combination.” Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 57: 1–14. doi:10.1515/zfw.2013.0001

- Stylidis, D., Y. Belhassen, and A. Shani. 2015. “Three Tales of a City: Stakeholders’ Images of Eilat as a Tourist Destination.” Journal of Travel Research 54: 702–716. doi:10.1177/0047287514532373

- Stylidis, D., Y. Belhassen, and A. Shani. 2017. “Destination Image, On-site Experience and Behavioural Intentions: Path Analytic Validation of a Marketing Model on Domestic Tourists.” Current Issues in Tourism 20: 1653–1670. doi:10.1080/13683500.2015.1051011

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2013. “Transformation of Regional Innovation Systems: From Old Legacies to New Development Paths.” In Re-framing Regional Development: Evolution, Innovation, and Transition, edited by P. Cooke, 297–317. London: Routledge.

- Trippl, M., S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, A. Frangenheim, A. Isaksen, and J. Rypestøl. 2020. “Unravelling Green Regional Industrial Path Development: Regional Preconditions, Asset Modification and Agency.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111: 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.016

- Trippl, M., M. Grillitsch, A. Isaksen, and T. Sinozic. 2015. “Perspectives on Cluster Evolution: Critical Review and Future Research Issues.” European Planning Studies 23: 2028–2044. doi:10.1080/09654313.2014.999450

- Zerubavel, Y. 2019. Desert in the Promised Land. Stanford: Stanford University Press.