ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to the discussion on the role of universities in regional path development, emphasizing the different agency types adapted. Accordingly, literature on ‘new path development’ is combined with the three agency types of innovative entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship and place-based leadership. This paper applies a long-term qualitative empirical approach with three case studies – Aalborg (Denmark), Kaiserslautern (Germany) and Twente (Netherlands). Results reveal that different types of agency are closely interwoven and complement each other in their effects on regional (industrial) path development. Additionally, the agency types are strongly influenced by (a) highly motivated individuals/frontrunners, (b) support and openness from the university leadership and (c) regional structures that facilitate university-region collaboration and joint governance.

1. Introduction

Policymakers and researchers from different fields have paid increasing attention to questions of when, how and under which circumstances new regional economic activities emerge (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2022; Tödtling, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2018). There is a consensus that regional (industrial) path development is place-specific and requires attention to the evolution of the institutional environment (Glückler, Suddaby, and Lenz Citation2018) and to the role of agency (Uyarra et al. Citation2017). However, while companies and their contribution to regional development have received more attention in the past, other actors have been neglected (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019). Essletzbichler (Citation2012) points out that ‘little to no attention has yet been paid to the role of agency, and the different types of agents that may drive regional diversification’. This particularly applies to universities, who are seen as important knowledge providers and development stimulators (Goddard and Puukka Citation2008; Smith Citation2007).

The role of universities for regional development in the broadest sense led to numerous scientific contributions (i) on the role of universities as provider of human capital and scientific knowledge, (ii) initiator of entrepreneurial activities via spin-offs and R&D, (iii) network actor in regional innovation systems (RIS) as well as in university-industry-government interactions, just to mention the most prominent ones. However, and in line with other authors, we identify a lack of understanding how these roles and developments have been driven on the micro level and investigate the research question ‘Which agency roles are taken on by universities and how do these affect on regional (industrial) path development processes?’ by the example of three European case studies. Besides scrutinizing the different agency roles of respective university individuals and organizational units (e.g. special research institutes), we investigate and analyse their development over time and contrast these with the wider regional (industrial) context.

Within Section 2, we develop a framework for the analysis of universities as agents in path development, situating the conceptual backdrop of this work at the interface of regional (industrial) path development and strategic agency. In Section 3, we outline the data and research methods and introduce the case universities. In Section 4, we sketch out the university storylines according to three agency types. Finally, we discuss which path development processes were stimulated by universities and put forward concluding remarks (Section 5).

2. Theoretical foundations – universities as strategic actors in regional (industrial) path development?

2.1. New regional (industrial) path development

While some scholars focus on ‘path creation’ as an umbrella term to refer to the rise of new industries in regions (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Martin and Sunley Citation2006) others prefer the generic term of ‘new path development’ and differentiate between different typologies of development (Grillitsch and Asheim Citation2018; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Isaksen, Martin, and Trippl Citation2018; Uyarra et al. Citation2017). This paper follows this later understanding of ‘new path development’ as an umbrella term for various forms of new economic activities in regions (). More recently, the differences between regions and their functioning as well as their preposition towards path development have been brought to the fore (Asheim, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018).

Table 1. Different typologies of path development.

MacKinnon et al. (Citation2019) identify five key dimensions of path creation: (1) regional and extra-regional assets (e.g. natural, infrastructural, industrial, labour skills, costs and knowledge); (2) actors (economic, social, institutional); (3) mechanisms of path creation (e.g. strategic coupling by knowledgeable actors, operating within multi-scalar institutional environments); (4) market construction (connections between regional assets and wider economic processes) and (5) institutional environments (set of rules and norms that inform the behaviour and strategies of actors). In doing so, this framework is in line with further studies (Boschma Citation2017; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Steen Citation2016), emphasizing the importance of multiple actors in creating, recreating and altering regional industrial development. Boschma (Citation2017) adds to this that only little attention is drawn on processes of institutional work enacted by institutional entrepreneurs (Battilana, Leca, and Boxenbaum Citation2009). They argue for considering the transition literature, as there is more focus on experimentation and the role of other actors including public agencies and the government that may enable niche formation and institutional change (Boschma Citation2017; Steen Citation2016). In doing so the strengths of EEG in revealing which place-specific contexts and regional capabilities are more conducive to new regional (industrial) development can be complemented by the transition literature focus on agency and institutional work. This would enable us to understand the dynamics of change and the multi-level environment (niche, regime, landscape) agents are interacting with (Geels et al. Citation2016). Of particular interest to this paper is the strand of research on strategic agency of knowledgeable actors, such as institutional entrepreneurs in universities, who mindfully deviate from established ways of doing things and break with existing social rules, technological paradigms and trajectories.

2.2. Strategic agency

In the late 1980s, the window of locational opportunity (WLO) approach made an early attempt to link human agency to new industry formation (Scott and Storper Citation1987), whereby the focus is on how new industries create a conducive milieu, instead of the other way round. A key impulse to the development of a micro-perspective on regional diversification was given by Klepper (Citation2007) who investigated the crucial role of spin-off entrepreneurs in new industry formation that make regions diversify. Seminal work by Garud and Karnoe (Citation2001) emphasized collective agency of knowledgeable actors – who ‘mindfully deviate’ from existing paths – as contradictory to the ‘canonical path dependency’ perspective (Simmie Citation2012). Recent literature stresses that a deeper understanding of ‘agency’ is considered the missing link in the understanding of regional growth (Asheim, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2016; Boschma Citation2017; Rodriguez-Pose Citation2013; Uyarra et al. Citation2017). The call for an integration of agency – embedded in a multi-actor approach – has been voiced in pursuance of the inclusion of a wider array of actors and multi-scalar institutional contexts that mediate the emergence and development of growth paths (Dawley Citation2014; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Nieth and Benneworth Citation2018). An important analytical distinction has been made between agency as the underlying capacity to act and the actors who exercise agency in distinct temporal and spatial contexts (Abdelnour, Hasselbladh, and Kallinikos Citation2017). Especially events and occurrences that start a new path of development may include a significant element of strategic purpose and deliberate action (Martin and Sunley Citation2006). Agency is best studied in its full complexity by situating it in long evolving development processes and structural changes of places (Sotarauta and Suvinen Citation2018). Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) differentiate between three types of agencies which exert influence on regional path development.

‘Innovative entrepreneurship’: concerns breaking with existing paths and working towards established new ones. In the Schumpeterian sense innovative entrepreneurship can tap knowledge and resources from extra-regional sources (Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018), is supported by structures for innovation and entrepreneurship (Mason and Brown Citation2014) and is influenced by the institutional environment, supporting or hindering it (Fritsch and Wyrwich Citation2014; Morgan Citation2017).

Institutional entrepreneurship: Institutions are carriers of social practices and routines (David Citation1994) and, by definition, relatively immune to change. Institutional entrepreneurs have an interest in particular arrangements; they mobilize resources to create new institutions or transform existing ones, initiate divergent change and actively participate in the implementation of these changes (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020). Often, they are constrained by the very same institutions they aim to change, embedded agency (DiMaggio Citation1988).

Place leadership: Sotarauta and Pulkkinen (Citation2011) point out that to make a difference, institutional entrepreneurs need a well-developed leadership capacity to influence across institutional and organizational divides. Place leadership aims to combine individual ambitions and goals into collective regional objectives. These shared visions and objectives are given increasing importance to collective agency of multiple actors (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Steen Citation2016). As such, place leadership is intrinsically concerned with (a) launching and guiding interactive development work that crosses various organizational boundaries and professional cultures and (b) guaranteeing the versatile engagement of various stakeholder groups and helping them to both contribute to and take advantage of development processes and their fruits (Gibney, Copeland, and Murie Citation2009).

2.3. Universities as strategic agents in regional path development

Since the last three decades, the interest in building ties between universities and the rest of the (regional) economy and investigating their potential to contribute to regional innovation and value creation increased (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation2000, Citation2017; Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2010). The literature on regional innovation systems (Cooke Citation2004), the cluster policy approach (Porter Citation2003) and more recent concepts on smart specialization (European Commission Citation2012) see universities as boundary-spanning institutional ‘nodes’ (Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer Citation2018; Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2010) which engage in territorial-embedded, innovation-related and institutionally supported networks (Asheim and Coenen Citation2006). As Arbo and Benneworth (Citation2007, 18) put it, ‘more and more aspects of the academic enterprise are thus perceived as being significant to the regeneration and transformation of the regions’. At the same time, several authors highlight that the impact a university can make depends on regional configurations (Cooke Citation2004) and the articulation of regional policies. These aspects lead directly to the ‘Triple Helix’ approach where universities are seen as catalysts of interactions and negotiations with government and industry (Etzkowitz et al. Citation2000; Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation1997).

As highlighted above, the strategic activities of non-firm actors towards path development have so far received insufficient attention in the past, although public agencies, like universities, can play a major role in developing new industries in regions (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019). While first answers can be found in studies by Asheim and Coenen (Citation2006), Benneworth (Citation2018) and Vallance (Citation2016), we want to go further by analysing the strategic agency roles that were taken on by universities in new path development processes.

Policymakers tend to overestimate the extent to which universities can be considered monolithic, rational actors pursuing a clear strategy with a single voice (Flanagan, Uyarra, and Laranja Citation2011). Rather they are multi-dimensional and complex organizations comprising multiple groups of experts that respond to their international communities of scientific practice (Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2010). Furthermore, universities have organizational structures that are not only decentralized and ‘loosely coupled’ (Weick Citation1976), but additionally, diverse disciplines have different approaches to creating, transmitting and transferring knowledge. Thus the university as a whole – as well as the different ‘academic tribes’ (Becher and Trowler Citation2001) within the university – can be seen as agents facing a ‘mission stretch’ or ‘mission overload’ (Brown Citation2016; Pinheiro, Benneworth, and Jones Citation2012; Scott Citation2007) when attempting to answer to the emerging expectations. Having said this, it is of foremost interest to investigate which agency roles are taken on by whom in the university and how they affect path development processes.

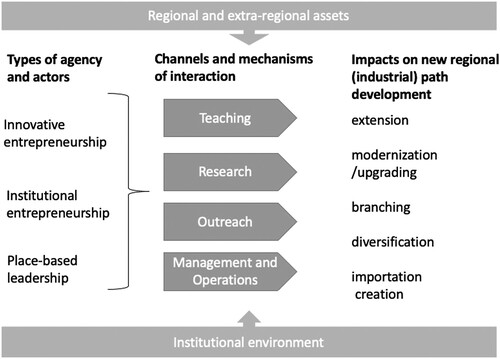

In the following, we apply the trinity of change model to universities (). We understand ‘universities as innovative entrepreneurs’ when the concept of the entrepreneurial university can be applied. This means the university promotes R&D projects, spinoffs, start-ups, etc. while creating new organizational structures such as TTOs and incubators. Second, ‘universities as institutional entrepreneurs’ refer to university members that influence the culture and norms of cooperation between the university and the region. The role of universities as institutional entrepreneurs is therefore initiated internally, for example, through the impulse of change at strategic levels or through the adaptation of new approaches towards regional cooperation in the frame of teaching, research, or outreach. This includes the establishment of a strategic regional perspective from within the university. Finally, ‘universities take on place leadership roles’, when acting as bridging institutions involved in the regional strategy process and visioning (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019) that open new path processes. In the following, we will apply this conceptual framework (see ) to three case study regions and universities that have undergone a regional reorientation – including the development of new paths – applying a processual perspective after Grillitsch and Soatrauta (Citation2020).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework: adaptation of the trinity of change agency framework (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020) to universities, taking into account the dimensions of path creation of MacKinnon et al. (Citation2019) (own illustration).

3. Methodology and cases

In line with our research question and the aim of this paper, we adopt an exploratory case study approach. Going beyond the literature-based conceptual analysis, our comparative qualitative case studies investigate a limited number of universities, shedding light on the roles these universities have taken in their regions’ path development processes. The criteria for selecting the universities were: (1) being rather young universities, (2) having a similar focus (in our cases all technical) and (3) being located in middle-sized cities in Western Europe (). Additionally, all three regions have faced challenges in dealing with the downturn of their traditional sectors, leading them to need to develop new paths. All three succeeded in ‘turning their fate around’ and have identified and strengthened new industries that shape the regions today. A final criteria for case selection was that the respective universities have been active agents in recognizing and developing new pathways. We agree with Steen (Citation2016) that qualitative methods are needed to provide new insights into the complexity of ongoing path creation processes.

Table 2. Characteristics of the three case study areas as well as an overview of the interviews conducted in each case study region.

Within each case study, extensive desk research has been conducted to gain context and historical knowledge on the case studies as well as to identify university members, who became active in the three types of change agency mentioned. The identified persons have been approached for 1–1.5-hour interviews (see ), sharing interview guidelines in advance. We asked each interview partner for further suitable interview partners. In addition to this snowball sampling approach, we interviewed regional collaboration partners that were mentioned as well as further persons due to their function (e.g. mayor of the city) to include their perspectives. We have followed this procedure until saturation. The recorded interviews were transcribed, and Atlas.ti software was used to support the coding and analysis process. We applied the presented definitions on agency, as well as types and dimensions of path development (see ) as underlying elements of the analysis. After an initial case-by-case analysis, we contrasted and integrated the results across the three case studies.

4 Empirical findings

4.1. Innovative entrepreneurship

4.1.1 Aalborg

Aalborg University was created to stimulate the economic growth of the region, with the first degrees focusing on industries present in the region. Nevertheless, the creation of new regional economies cannot be seen as the ‘official goal’ of the university. Accordingly, while the university has been involved in activities that are related to creating start-ups/spinouts and the commercialization of research activities, these activities are not the principal drivers of the university.

A restructuring process initiated in 2017 made the internal support unit of the university, AAU Innovation & Research Support, independent from faculties and departments. It now provides ‘more strategic, more objective driven’ support service for staff and students within themes such as tech-transfer, commercialization and entrepreneurship. Another important role of AAU Innovation is the support of cluster initiatives in which the AAU has taken a significant role as a knowledge provider. Thus this internal change within AAU has the potential to exponentiate activities/acts of innovative entrepreneurship.

4.1.2 Kaiserslautern

The political expectation to spur economic development of the Westpfalz region was part of the founding history of the TUK. These expectations focused on the provision of skilled school teachers to the region as well as the offer of numerous high-quality workplaces at the university. It was initially (in the 1980s) due to individual institutional entrepreneurs that the TUK developed an innovative entrepreneurship role: the university’s focus on natural science and technology and the establishment/attraction of numerous applied institutes led to the foundation of numerous spinoffs since the 1980s. Especially in the field of ICT, these spinoffs led to the establishment of a new industrial branch. A further example is the modernization and digitalization of the textile industry, where only a few companies (e.g. Spinnerei Lampertsmühle Gmbh) were left after the crisis: different innovations led to a modernization, digitalization and upgrading of this branch.

The institutional environment (the federal state and city of KL) favoured the cooperation between the regional industry and applied research at the university via R&D funding (‘There has always been money for SMEs to engage in research with the university’), industrial areas and supporting infrastructure (e.g. BIC – Business and Innovation Center) from the 1990s onwards. This type of agency – focused on R&D projects, spinoff foundations and patents – is, however, only applicable for selected technical and natural science institutes at the TUK.

4.1.3 Twente

Reactivating the economic development of the region and breaking away from a situation of economic decline and uncertainty is one of the founding reasons for the UT. This drive towards economic development can be seen today and has been one of the UT objectives – closely linked to entrepreneurship and producing start-ups. Due to its performance in creating spinoffs, the UT was ranked ‘most enterprising university’ in the Dutch ranking in 2013, 2015 and 2017. The most recent numbers show that to date the entrepreneurial and start-up support of the UT has resulted in more than 1000 start-ups with approximately 50 student enterprises being initiated yearly. Being a technological university, it can be seen that the combination of knowledge and resources to the ‘outside’, is mainly through commercial knowledge transfer, tech-transfer, patents, and the creation of new companies – habitually directly linked to the ultimate goal of creating economic value.

The UT has thus played a major role in revitalizing the textile industry. Companies from areas such ‘smart textiles’ and ‘wearable technology’ have given the region a new future advancing and developing knowledge and products in cooperation with the UT. The high-tech sector in Twente has received substantial support from regional governance bodies and the university and new companies have emerged which are now internationally known and are often initiated, advanced, or heavily supported by the UT and/or UT students. The university is thus seen as a vital agent for innovative entrepreneurship in the region. The establishment of Novel-T – a joint foundation between the university, the municipality, the polytechnic, and the province – can be seen as a clear effort in creating a cooperative structure that pushes for (high-technology) entrepreneurship and (technology) transfer activities in the region.

4.2. Institutional entrepreneurship

4.2.1 Aalborg

The rather strong place-based leadership role of AAU is assisted by individual and collective acts of institutional entrepreneurship. These acts of institutional entrepreneurship, based on individuals and groups of individuals that initiate changes processes, are very much depended on the ‘room for experimentation’ that is given to the institutional entrepreneurs by university leadership and/or within the university structure. Needless to say, these ‘rooms for experimentation’ change over time according to the respective priorities of leadership and the skills of institutional entrepreneurs to bypass potential restrictions/limitations.

We perceived a rather open approach towards acts of institutional entrepreneurship under one of the former AAU rectors and his leadership team. He was known for ‘decentralizing the power in the system’ to give individuals the room to manoeuvre – even ‘building up incentives in the systems’ for individuals and their experimental activities. University staff and external partners reported a policy of ‘no wrong doors’ – giving institutional entrepreneurs the opportunity to test, initiate and implement change processes. This openness not only allowed other institutional entrepreneurs to become active and interact with the region and potential local partners, but it also initiated an institutional change within AAU with regard to regional cooperation.

It’s under this leadership approach that a ‘network centre’ for tech/knowledge transfer and third-stream activities was created in 1996-99. This ‘centre’ was initiated by a few people and lead by a ‘visionary director’ within the Faculty of Science and Engineering. This same centre, today named AAU Innovation & Research Support, has now taken on activities such as finding student projects in the realm of the problem-based learning approach, creating a matchmaking system (see Nieth and Benneworth Citation2020a), and housing the university incubator. Thus it was created due to acts of individuals who had a vision for their university to find new ways of supporting researchers and students in their external engagement activities. It initiated a process that over the years changed institutional practices and understanding and can be seen as a historically important act of institutional entrepreneurship.

The approach of the current university leadership was described as being more focused and less open to the diverse regional engagement activities. Due to a missing incentive system for third-stream activities, many of the regional engagement activities are based solely on those individual/collective institutional entrepreneurs who decide to enact regional activities despite not receiving direct support for it. These acts of agency then might initiate institutional changes, although they might be in contrast to the priorities set by AAU’s leadership.

4.2.2 Kaiserslautern

From the 1970s onwards, regional engagement activities were pioneered by a particular individual who invented a new type of teaching method called ‘Modellierungsseminare’ (Mathematical modelling seminar), collecting the topics and research questions from local and regional businesses. This resulted in new contacts with the regional economy and raised awareness in the region for the support the university can provide: ‘after 10 years we, the university, went to the region, the regional actors/entrepreneurs began to visit us’. It was this professor who initiated the foundation of the Science Alliance, a network to connect the university to the regional economy and city. Another example showing continuous collaboration with the region is the different clusters. The various (applied) institutes became partners in the metal and commercial vehicle cluster, where they influenced the practice of R&D collaboration as well as joint marketing.

One example of a synergy between institutional entrepreneurship and innovative entrepreneurship is the textile industry. Due to the innovation of new software the whole industry experienced modernization and upgrading, resulting in the settlement of foreign sewing companies. This led to a more offensive strategy of the regional textile industry and first attempts to establish a textile cluster. Additionally, other university employees in leading positions (foremost in the field of urban and spatial planning, informatics) acted as frontrunners for regional engagement. They initiated regional research projects and collaborations, participated in diverse boards and steering committees and provided consultancy for decision-makers.

Two opposing positions towards regional collaboration can be detected within the university: one position which supports the ivory tower and basic research with an international agenda (‘silicon woods’) and the other where collaboration and openness towards the region are prioritized. It was the TUK Hochschulkuratorium (the universities board of trustees, HK) that took up these challenges. Although the HK has no direct operational impact, they bring regional topics and demands to the table and shape the practice of regional collaboration. The head of the HK initiated a cultural and normative change by bringing together the mayor of KL, representatives from the regional economy as well as the university in an informal but successful way. The HK acts like a bridging organization and raises awareness, e.g. for the shortage of skilled workers and diminishing student numbers.

4.3 Twente

Institutional entrepreneurship influencing the role of the university in the region has mainly been initiated top-down and resulted in foremost normative changes as well as organizational transformations. The first significant wave of institutional change was induced by the former rector Van de Kroneberg, who gave an entrepreneurial mindset to the university. This self-image influenced the normative and cultural understanding of science, including a change in research and teaching contents, regional collaborations as well as commercialization of scientific findings. A second type of organizational change induced by the top management is the foundation of the DesignLab. The purpose of the DesignLab is to bridge academic disciplines and engage with society. The experiences so far show that ‘universities are not the best engine for collaboration that you can imagine. Because the main structure in which researchers are rewarded is very much on an individual basis and not on a collective basis. Here is a lot of competition’.

In 2015, the Strategic Business Development Unit was set up with the premise that ‘everything we do needs to feed back into our core competences’. Core aims are to professionalize R&D cooperation with the region but even more, worldwide; to make all departments become aware of the importance of industry cooperation, projects, and the optimization of these processes. Recent developments make it apparent that the induced institutional and organizational changes, resource allocation and commitment from top management, favour commercialization-based international activities over regional engagement/development activities (Nieth and Benneworth Citation2020b).

4.4. Place leadership

4.4.1 Aalborg

AAU was ‘created’ as a regional university with a focus on regional priorities, supported by ‘influential individuals’ from policy and industry, taking a rather strong place-based leadership role from its beginning. In that sense, AAU actively engaged with and mobilized other actors (companies, clusters, policy, etc.) for stimulating change and development in the region. Still today, diverse regional stakeholders refer to AAU as ‘our university’, showing strong reciprocal commitment and a robust relationship.

The continuous commitment of the university to the region and its stakeholders can be seen through the problem-based learning and teaching approach applied. This approach sees very close cooperation between AAU (researchers and students) and the regional partners (mainly industry, but also social and governmental partners), described as the ‘most important bridge from us (AAU) to the region’. These close interactions allow partners on both sides to benefit from the exchange of knowledge and experiences, reaching beyond short-term relationships and individual interests.

The place-based leadership role can be seen in the formal and informal interaction of AAU with the Growth Forum (GF), a stakeholder coalition defining regional priorities and strategies, also distributing funds within the region. A strong commitment towards a joint development of regional strongholds was perceived by the interview partners, with AAU taking a role in coordinating these complex multi-actor processes. The AAU often connects the region to the international stage, for instance in internationally known/distinguished clusters (see, for instance, Lindqvist, Smed Olsen, and Baltzopoulos Citation2012, Stoerring and Dalum Citation2007). Two examples of internationally known clusters in which AAU has taken a very active role are House of Energy (sustainable energy technologies) and Brains Business (digital technologies, formerly known as BrainsBusiness). Within these different initiatives/processes the university was often described as a knowledge provider – defining which international trends are relevant in North Jutland, drawing the attention of other actors to those strategic themes and potentially designing new ways of implementation.

The rather strong place-based leadership role of AAU appears to be less visible today as it became overshadowed by new priorities such as global competition, international university rankings, internationalization, lobbying, etc. This change has been described to be particularly visible under the current leadership, which has encouraged a selective form of regional engagement only when/where clear benefits for AAU can be seen. In contrast, the former AAU leadership was known for looking beyond individual and institutional interests, thus acting l in the interest of joint regional change/development.

4.4.2 Kaiserslautern

After the economic crisis in the 1970s, the TUK became the motor for innovation, jobs, and the regional image. With regard to their place leadership role and their participation in strategic regional development processes, the Westpalz region is characterized by numerous failed attempts to elaborate a regional (economic) development strategy. In 2010, the economic actors made a new attempt founding the ‘Zukunftsregion Westpfalz’ as an association to combine the various regional (economic) interests. In this association, the university was to provide information and consultancy. Via the teaching and research portfolio of the TUK, links to the regional industry are provided as well as the support to start an own business. Additionally, the university incentivizes topics like ‘digitalization’ or ‘sustainability’ in the region.

In the context of place leadership, two organizations have to be pointed out: The above-mentioned HK as well as the ZIRP – Zukunftsinitiative Rheinland Pfalz (Future Initiative Rhineland Palatine). The ZIRP was founded in 1992 with the aim to broach and discuss current topics, as well as bring together actors from different sectors (including the university). Nevertheless, the experience with the university has been perceived as being reluctant to implement changes. Furthermore, they have difficulties working interdisciplinary: ‘The exchange between the different sectors which is initiated through the activities of the ZIRP is not yet self-evident nor institutionalized’. It is mainly the motivation and engagement of the beforehand mentioned frontrunners, their bridging activities, and informal networks that influence the local and regional opinion leaders and decision-makers.

4.5 Twente

The place leadership role of the UT is closely linked to its innovative entrepreneurship role in that the UT is seen as a leading actor in boosting regional economic development based on entrepreneurship, company creation and tech-transfer. As the industrial structure of the Twente region is rather scattered and SME-based, the university is seen as a leading stakeholder that can ‘set the regional agenda’ – together with the governmental institutions – and define strategic key areas in the absence of leading multinationals or a united voice of the industry.

As the UT takes such a central role in the region, it is also represented in the Twente Board – an economic board that connects regional stakeholders and is involved in the definition and implementation of regional priorities. The UT is described as a facilitator, connector or even persuader between the diverse partners of the board ‘really (helping to| form a common agenda with all the parts)’. Thereby clearly taking place leadership attributes of mobilizing and coordinated activities for path development. Being an international knowledge institution, the UT is seen and sees itself as ‘having a voice’ as it has a broad horizon. This role has been described as being more focused today, with the UT positioning itself as a clear partner in the project portfolio and the regional agenda, going beyond individual interests. Overall, one has to point out that this leadership role has been facilitated lately with a regional focus on (high) technology – which is clearly in line with the university’s prioritization of entrepreneurial and high-tech teaching, research and activities.

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Impacts on different types of regional (industrial) path development

To answer our research question ‘Which agency roles are taken on by universities and how do these affect (industrial) path development processes?’, we now turn our focus to the different types of path development which have been stimulated by the respective universities. We identify four types of path development in our case studies: path extension, path modernization/upgrading, path importation and path creation ().

In all three case studies, the societal/political expectation was that the respective (technical) universities would support ‘path extension’ as well as ‘path modernization/upgrading’ of the existing industries. Indeed, we saw that the universities contributed to these types of path developments through activities such as study programs based on regional industries (AAU), innovative products/process developments in the frame of R&D projects (TUK, UT) as well as industry/problem-based teaching approaches (AAU, TUK). Thus the universities did support the existing industrial bases – as can also be seen in the case of the communication technologies in Aalborg, the metal and commercial vehicle industry in Kaiserslautern and the (advanced) manufacturing industry in Twente.

‘Path modernization/upgrading’ was the prevalent development in all three case study regions. In the case of the TUK and UT, a strong example is the declining textile industry which was revived by product, software and process innovations at the respective universities. These innovations often turned into spinoff companies (e.g. Human Solutions GmbH, TUK; Xsens, Sheltersuit, UT). The development of the textile industry is an example for a synergy between institutional entrepreneurship and innovative entrepreneurship. Due to individual innovations (mostly within start-ups) the whole industry experienced modernization and upgrading, resulting in the settlement of foreign companies (e.g. Xi’an Typical Europe GmbH, Sun Star Europe GmbH). This then led to a more offensive strategy of the whole regional textile industry and (attempts to establish) a textile cluster.

Furthermore, university-internal organizational innovations (such as Technology Transfer Office and Business and Incubation Center at TUK, AAU Innovation and Research Support, Design Lab and Strategic Business and Development Unit at UT) led to institutionalization and professionalization of university-region collaboration which further supported these path trajectories. With regards to university-external organizational innovations, the TUK, as well as AAU, play a strong role as knowledge providers and coordinators of the respective clusters (metal and commercial vehicle cluster in Kaiserslautern, energy technology and communication/digital technology cluster in Aalborg). In the case of the TUK, several applied institutes were the initiators of the software cluster. On the local and regional political level, the universities influence regional strategy making via place-based leadership, through the initiation of/ and active participation in pertinent networks and strategic boards (e.g. UT in the Twente Board, AAU in the Growth Forum, TUK in the ZIRP and Science Alliance), influencing regional strategy and decision making and bringing in new topics such as digitalization or also sustainability.

‘Path importation’ appears in all three case studies and is the result of former path modernization, extension and creation developments. The critical mass of new spinoff firms, renowned product or process innovations as well as network and cluster activities led to the settlement of foreign firms (e.g. John Deere, several sewing companies in Kaiserslautern) and even the establishment of new industries. Furthermore, the strategic coupling of regional and extra-regional assets by the universities through international partnerships and efforts invested in the inflow of skilled work forces as well as international students supported path importation.

The universities became renowned for their ‘path creation’ efforts, that is activities which led to the emergence and growth of entirely new industries. The TUK as well as the UT provided the seedbed for numerous spinoffs in the field of ICT, which developed into internationally renowned companies and state important regional working opportunities for university graduates. All three agency types supported these processes of path creation. Innovative entrepreneurship activities in the form of new value-added products, pilot projects as well as tapping of extra-regional knowledge sources together with institutional changes and organizational changes provided the basis for new (industrial) path creation. Networks and coalitions between various regional actors (e.g. Science Alliance and Diemersteiner Kreis in Kaiserslautern and Novel T in Twente) and other place-based leadership activities (participation in strategic decision-making bodies, e.g. AAU in the Growth Forum, UT in Twente Board) have been especially important to legitimize these new path trajectories and to seek support and resources (e.g. business locations for spinoffs). As the universities were active in these strategic regional boards/arrangements, they were able to recognize and introduce internationally relevant themes and industries to regional partners (which were not aware of these new ‘trends’) and, thus, encourage the creation (sometimes also ‘importation’) of new paths/industries.

5.2 Dimensions of strategic agency

We identify that the different types of agency have a synergetic effect on path development: place-based leadership activities establish the collaborative and strategic framework on the regional (political) level, based on which more concrete actions – induced by innovative or institutional entrepreneurship – are legitimized and supported. To comprehensively understand the role of universities on regional path developments, it is thus necessary to enlighten who took on the agentic role within the university, how the strategic coupling of regional and extra-regional assets took place as well as how the institutional environment influenced these developments (MacKinnon et al. Citation2019).

5.2.1 Actors

Within the case studies, strategic agency was induced bottom-up at the TUK by academic frontrunners (a handful since the 1970s), at the UT it was exerted mainly top-down by the rectorate or university management via the institutionalization of new organizational units (e.g. the foundation of the Design Lab as well as Strategic Business Unit) as well as by the national government. At the AAU, it is an interplay of top-down and bottom-up: the former leadership style of ‘everything goes’ provided a window of opportunity for institutional change processes towards regional cooperation by individuals. The missing incentive system for third stream activities led to regional engagement activities being mainly based on individuals/collective acts of institutional entrepreneurship. So-called ‘frontrunners’ or ‘institutional entrepreneurs’ (Battilana, Leca, and Boxenbaum Citation2009; DiMaggio Citation1988) take agency and precipitate organizational and institutional change within the HEI. They have an interest in particular institutional arrangements and mobilize resources, competencies and power to create new institutions or transform existing ones (Battilana Citation2006; Feldman, Francis, and Bercovitz Citation2005; Feldman Citation2014; Sotarauta and Pulkkinen Citation2011). Apart from their position, their personal multi-scalar networks and their relational proximity to public and private stakeholders facilitate the necessary regional support. Besides these engaged individuals, the leadership of the university management is important to institutionalize and professionalize various agentic activities as well as to legitimize the universities influence on regional path developments.

5.2.2 Regional and extra-regional assets

In all three regions, the universities mobilized a high percentage of students from the region, who became important labour forces for the regional economy after graduation. Furthermore, universities react to the fact that regional assets are not in themselves a sufficient basis for regional development (Coe and Yeung Citation2015) but must be coupled with extra-regional assets such as industrial and human assets (e.g. technology, skills) (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016). Universities are particularly suitable to do so, as they are regionally embedded but at the same time active within a multi-scalar international environment. Their research foci and excellence attract international companies, project partners as well as skilled labour forces, which were of special importance for de-locking of regional paths.

5.2.3 Mechanisms

Mechanisms play a crucial role in the transition from the ‘preformation’ phase to path creation proper and subsequent path development (Martin Citation2000) by fostering self-reinforcing growth. Based on excellent research and R&D cooperation, path extension and modernization have been induced in existing industries and new regional paths have been established via numerous spinoff companies. These developments have been supported by the university (TTOs, funding, space) as well as the community and region (e.g. funding programs, settlement opportunities). The active engagement and boundary spanning role (Radinger-Peer and Pflitsch Citation2017) in the above-mentioned networks and strategic boards, the generation of a critical mass as well as of agglomeration effects (e.g. clusters) (Martin Citation2010) supported the legitimation of the described path developments. Once a path has gained momentum and critical mass, its further reproduction is dependent upon periodic recoupling between regional assets and mechanisms (MacKinnon et al. Citation2019) as well as developing supportive linkages with the broader institutional environment (Smith and Raven Citation2012).

5.2.4 Institutional environment

The institutional environment is multi-scalar and reflects the interplay of local, regional and national rules and norms (Gertler Citation2010). The legitimation of new path trajectories involves the development of broader socio-political narratives (Smith and Raven Citation2012) and the therewith regulative and financial support of political decision-makers. Place leadership activities as well as lobbying (Elzen, van Mierlo, and Leeuwis Citation2012) are often focused on the introduction of policies and funding instruments that shield the emerging path from competition from incumbent technologies and industries (Bergek, Jakobsson, and Sanden Citation2008). As a result, innovation can be aligned with established rules, actors and practices, serving to anchor regional paths with key technological, network and organizational aspects of the institutional environment (Murphy Citation2015). What becomes evident at TUK as well as at UT is the support of the institutional environment for the entrepreneurial role of the university (e.g. by providing funding for R&D, the founding of NOVEL T) (Brown Citation2016; Fritsch and Wyrwich Citation2014; Morgan Citation2017).

5.3 University agency roles in regional paths development

The current research paper enlightened the question on which agency roles universities take on in regional path development and how they influence the development process. By applying the trinity of change agency framework (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020) on universities – as one example for a public actor – the investigated multi-national case studies show similarities but also noticeable differences. Although all three universities have been founded with the expectations to spur the economic development of their region, they fulfilled this mission in different ways and via different types of agency. However, our investigations have revealed that these different types of agencies are closely interwoven and the therewith effects on regional path development complement each other. Innovative entrepreneurship led to new industrial path creations, mainly in the field of ICT. Via institutional entrepreneurship organizational change within the universities was spurred and resulted in the institutionalization of university-region cooperation. Their effect in addition to individual role models released cultural and normative changes within the university towards regional engagement. Place leadership takes shape through the brokering, bridging and boundary spanning function of place leaders at formal and informal levels. All three types are strongly influenced by (a) highly motivated individuals/frontrunners, (b) support and openness from the university leadership and (c) regional structures that ‘allow’ for university-region collaboration/joint governance.

As universities are only one type of non-firm actor, we are aware that our contribution sheds light on one particular part of a larger whole. While this research has allowed us to focus upon this one actor – exploring universities in depth – we see the potential for conducting additional, similar studies on other public or private agents/stakeholders involved in these types of path development processes. An interesting example we found in this regard is the recent study by Grillitsch, Asheim, and Nielson (Citation2019), focusing on reactive and proactive agency in one case study region in Western Norway.

Comparing three in-depth case studies not only allows to gain a better understanding of contextual and institutional factors, it also enables us to contribute to theory-building as patterns and conclusions across cases can be drawn (Bryman Citation2012, 73). Therefore the replicability – or generalizability – of the findings can be considered – at least for universities in similar settings.

In terms of policy recommendations, our case studies show that all three universities – once created with a clear regional mission –are either undergoing a very severe mission stretch or are facing tensions that mitigate their regional role (Brown Citation2016). Thus policy makers cannot assume universities to ‘simply be regional’ or ‘take on regional agency roles’ without considering the complexities of the (international) higher education sector and diverse sets of expectations towards the regional contribution of universities (see also Fonseca and Nieth Citation2021).

Funding details

This research was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (grant number T761-G27). The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under MSCA-ITN Grant agreement No. 722295.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. Furthermore, we would like to thank Markus Grillitsch and Markkus Sotarauta for their valuable feedback on early versions of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdelnour, S., H. Hasselbladh, and J. Kallinikos. 2017. “Agency and Institutions in Organization Studies.” Organization Studies 38 (12): 1775–1792. doi:10.1177/0170840617708007

- Arbo, P., and P. Benneworth. 2007. Understanding the Regional Contribution of Higher Education Institutions: A Liter-Ature Review. Education Working Paper No. 9. Paris: OECD.

- Asheim, B., and L. Coenen. 2006. “Contextualising Regional Innovation Systems in a Globalising Learning Economy: On Knowledge Bases and Institutional Frameworks.” Journal of Technology Transfer 31: 163–173. doi:10.1007/s10961-005-5028-0

- Asheim, B., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2016. “Regional Innovation Systems: Past–Present–Future.” In Handbook on the Geographies of Innovation, edited by R. Shearmur, C. Carrincazaeaux, and D. Doloreux, 45–62. Celtenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Asheim, B., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. Advanced Introduction to Regional Innovation Systems. Elgar Advanced Introductions. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Battilana, J. 2006. “Agency and Institutions: The Enabling Role of Individuals’ Social Position.” Organization 13 (5): 653–676. doi:10.1177/1350508406067008

- Battilana, J., B. Leca, and E. Boxenbaum. 2009. “How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship.” The Academy of Management Annals 3 (1): 65–107. doi:10.5465/19416520903053598

- Becher, T., and P. Trowler. 2001. Academic Tribes and Territories: Intellectual Enquiry and the Culture of Disciplines. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Benneworth, P., ed. 2018. Universities and Regional Economic Development - Engaging with the Periphery. London: Routledge.

- Bergek, A., S. Jakobsson, and B. Sanden. 2008. “Legitimation’ and ‘Development of Positive Externalities’: Two Key Processes in the Formation Phase of Technological Innovation Systems.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 20: 575–592. doi:10.1080/09537320802292768

- Binz, C., B. Truffer, and L. Coenen. 2016. “Path Creation as a Process of Resource Alignment: Industry Formation for on-Site Water Recycling in Beijing.” Economic Geography 92: 172–200. doi:10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Boschma, R. 2017. “Relatedness as Driver of Regional Diversification: A Research Agenda.” Regional Studies 51 (3): 351–364. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Brown, R. 2016. “Mission Impossible? Entrepreneurial Universities and Peripheral Regional Innovation Systems.” Industry and Innovation. doi:10.1080/13662716.2016.1145575.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coe, N., and H. Yeung. 2015. Global Production Networks: Theorising Economic Development in an Interconnected World. Oxford University Press.

- Cooke, P. 2004. “Evolution of Regional Innovation Systems – Emergence, Theory, Challenge for Action.” In Regional Innovation Systems: The Role of Governances in a Globalized World, edited by P. Cooke, M. Heidenreich, and H. Braczyk, 1–18. Abingdon, UK and New York, NY: Routledge.

- David, P. 1994. “Why are Institutions the ‘Carriers of History’?: Path Dependence and the Evolution of Conventions, Organizations and Institutions.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 5 (2): 205–220. doi:10.1016/0954-349X(94)90002-7

- Dawley, S. 2014. “Creating New Paths? Offshore Wind, Policy Activism, and Peripheral Region Development.” Economic Geography 90 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1111/ecge.12028

- DiMaggio, P. 1988. “Interest and Agency in Institutional Theory.” In Institutional Patterns and Organizations, edited by L. Zucker, 3–22. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

- Elzen, B., B. van Mierlo, and C. Leeuwis. 2012. “Anchoring of Innovations: Assessing Dutch Efforts to Harvest Energy from Glasshouses.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transition 5: 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2012.10.006

- Essletzbichler, J. 2012. “Renewable Energy Technology and Path Creation: A Multi-Scalar Approach to Energy Transition in the UK.” European Planning Studies 20: 791–816. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.667926

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 1997. Universities and the Global Knowledge Economy. A Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations. London: Pinter.

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 2000. “The Dynamicsof Innovation: From Nationa Systems and ‘Mode 2’ to a Tripel Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations.” Research Policy 29 (2): 109–123. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 2017. “Introduction: Universities in the GLobal Knowledge Economy.” In Universities and the Global Knowledge Economy: A Triple Helix of Uniersity-Industry-Government Relations, edited by H. Etzkowitz, and L. Leydesdorff, 1–8. London: Pinter.

- Etzkowitz, H., A. Webster, C. Gebhardt, and B. Terra. 2000. “The Future of the University and the University of the Future: Evolution of Ivory Tower to Entrepreneurial Paradigm.” Research Policy 29: 313–330. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00069-4

- European Commission. 2012. Guide for Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization (RIS3). Brussels, Belgium: European Comission.

- Feldman, M. 2014. “The Character of Innovative Places: Entrepreneurial Strategy, Economic Development, and Prosperity.” Small Business Economics 43 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9574-4

- Feldman, M., J. Francis, and J. Bercovitz. 2005. “Creating a Cluster While Building a Firm: Entrepreneurs and the Formation of Industrial Clusters.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 129–141. doi:10.1080/0034340052000320888

- Flanagan, K., E. Uyarra, and M. Laranja. 2011. “Reconceptualising the ‘Policy Mix’ for Innovation.” Research Policy 40 (5): 702–713. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.02.005

- Fonseca, L., and L. Nieth. 2021. “The Role of Universities in Regional Development Strategies: A Comparison Across Actors and Policy Stages.” European Urban and Regional Studies 8 (3): 298–315. doi:10.1177/0969776421999743

- Fritsch, M., and M. Wyrwich. 2014. “The Long Persistence of Regional Levels of Entrepreneurship: Germany, 1925–2005.” Regional Studies 48 (6): 955–973. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.816414

- Garud, R., and P. Karnoe. 2001. Path Dependence and Creation. New York: Psychology Press.

- Geels, F., F. Kern, G. Fuchs, N. Hinderer, G. Kungl, J. Mylan, M. Neukirch, and S. Wassermann. 2016. “The Enactment of Socio-Technical Transition Pathways: A Reformulated Typology and a Comparative Multi-Level Analysis of the German and UK low-Carbon Electricity Transitions (1990–2014).” Research Policy 45: 896–913. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2016.01.015

- Gertler, M. 2010. “Rules of the Game: The Place of Institutions in Regional Economic Change.” Regional Studies 44:1–15. doi:10.1080/00343400903389979

- Gibney, J., S. Copeland, and A. Murie. 2009. “Toward a ‘New’ Strategic Leadership of Place for the Knowledge-Based Economy.” Leadership 5: 5–23. doi:10.1177/1742715008098307

- Glückler, J., R. Suddaby, and R. Lenz, eds. 2018. Knowledge and Institutions. Vol. 13. Heidelberg: Knowledge and Space.

- Goddard, J., and J. Puukka. 2008. “The Engagement of Higher Education Institutions in Regional Development: An Overview of the Opportunities and Challenges.” Higher Education Management and Policy 20 (2): 11–42. https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-v20-art9-en

- Grillitsch, M., and B. Asheim. 2018. “Place-based Innovation Policy for Industrial Diversification in Regions.” European Planning Studies. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2018.1484892.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and H. Nielson. 2019. Does Long-Term Proactive Agency Matter for Regional Development? Papers in Innovation Studies, Centre for Innovation, Research and Competence in the Learning Economy (CIRCLE). Lund University.

- Grillitsch, M. and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography, 44 (4): 704–723. doi: 10.1177/0309132519853870.

- Hassink, R., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of new Regional Industrial Path Development.” Regional Studies 53, 1636–1645. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Isaksen, A., R. Martin, and M. Trippl. 2018. New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems - Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons. Cham: Springer.

- Klepper, S. 2007. “Disagreements, Spinoffs, and the Evolution of Detroit as the Capital of the U.S. Automobile Industry.” Management Science 53: 616–631. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0683

- Lindqvist, M., L. Smed Olsen, and A. Baltzopoulos. 2012. “Strategies for Interaction and the Role of Higher Education Institutions in Regional Development in the Nordic Countries.” Nordregio Report, 2. Stockholm.

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95: 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Martin, R. 2000. “Institutional Approaches in Economic Geography.” In A Companion to Economic Geography, edited by T. Barns, and E. Sheppard, 77–94. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Martin, R. 2010. “Rethinking Path Dependence: Beyond Lock-in to Evolution.” Economic Geography 86: 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (4): 395–437. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Mason, C., and R. Brown. 2014. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship. Final Report to OECD. Paris: OECD.

- Morgan, K. 2017. “Nurturing Novelty: Regional Innovation Policy in the Age of Smart Specialisation.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (4): 569–583. doi:10.1177/0263774X16645106

- Murphy, J. 2015. “Human Geography and Socio-Technical Transition Studies: Promising Intersections.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 17: 73–91. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2015.03.002

- Nieth, L., and P. Benneworth. 2018. “Universities and neo-Endogenous Peripheral Development. Towards a Systematic Classification.” In Universities and Regional Economic Development – Engaging with the Periphery, edited by P. Benneworth, 13–25. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Nieth, L., and P. Benneworth. 2020a. “Challenges of Knowledge Combination in Strategic Regional Innovation Processes - the Creative Science Park in Aveiro.” European Planning Studies 28 (10): 1922–1940. DOI: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1699908

- Nieth, L., and P. Benneworth. 2020b. “Regional Policy Implications of the Entrepreneurial University: Lessons from the ECIU.” In Examining the Role of Entrepreneurial Universities in Regional Development, edited by A. D. Daniel, A. Teixeira, and M. Torres Preto, 242–259. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-7998-0174-0.ch013.

- Pflitsch, G., and V. Radinger-Peer. 2018. “Developing Boundary-Spanning Capacity for Regional Sustainability Transition - A Comparative Case Study of the Universities of Augsburg (Germany) and Linz (Austria).” Sustainability 10:918. doi:10.3390/su10040918

- Pinheiro, R., P. Benneworth, and G. Jones. 2012. Universities and Regional Development. A Critical Assessment of Tensions and Contradictions. New York: Routledge.

- Porter, M. 2003. “The Performance of Regions.” Regional Studies 37 (6/7): 549–578. doi:10.1080/0034340032000108688

- Radinger-Peer, V., and G. Pflitsch. 2017. “The Role of Higher Education Institutions in Regional Transition Paths Towards Sustainability – the Case of Linz (Austria).” Review of Regional Research 37: 161–187. doi:10.1007/s10037-017-0116-9

- Rodriguez-Pose, A. 2013. “Do Institutions Matter for Regional Development?” Regional Studies 47 (7): 1034–1047. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Scott, W. 2007. “Back to the Future? The Evolution of Higher Education Systems.” In Looking Back to Look Forward. Analyses of Higher Education After the Turn of the Millennium, edited by B. M. Kehm, 13–28. Kassel: University of Kassel.

- Scott, A., and M. Storper. 1987. “High Technology Industry and Regional Development. A Theoretical Critique and Reconstruction.” International Social Science Journal 112: 215–232.

- Simmie, J. 2012. “Path Dependence and New Path Creation in Renew- Able Energy Technologies.” European Planning Studie 20: 729–731. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.667922

- Smith, H. 2007. “Universities, Innovation, and Territorial Development: A Review of the Evidence.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25 (1): 98–114. doi:10.1068/c0561

- Smith, A., and R. Raven. 2012. “What Is Protective Space? Reconsidering Niches in Transitions to Sustainability.” Research Policy 41: 1025–1036. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012

- Sotarauta, M., and R. Pulkkinen. 2011. “Institutional Entrepreneurship for Knowledge Regions.” Environment and Planning C 29 (1): 96–112. doi:10.1068/c1066r

- Sotarauta, M., and N. Suvinen. 2018. “Institutional Agency and Path Creation.” In New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems – Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons, edited by A. Isaksen, R. Martin, and M. Trippl, 85–106. Cham: Springer.

- Steen, M. 2016. “Reconsidering Path Creation in Economic Geography: Aspects of Agency, Temporality and Methods.” European Planning Studies 24 (9): 1605–1622. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Stoerring, D., and B. Dalum. 2007. Cluster Emergence: A Comparative Study of Two Cases in North Jutland, Denmark. In Creative Regions: Technology, Culture and Knowledge Entrepreneurship. Routledge, P. Cooke & D. Schwartz, 127–147. London: Routledge.

- Tödtling, F., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2018. “Innovation Policies for Regional Structural Change: Combining Actors-Based and System-Based Strategies.” In New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems - Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons, edited by A. Isaksen, R. Martin, and M. Trippl, 221–238. Cham: Springer.

- Trippl, M., M. Grillitsch, and A. Isaksen. 2018. “Exogenous Sources of Regional Industrial Change: Attraction and Absorption of Non-Local Knowledge for New Path Development.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (5): 687–705. doi:10.1177/0309132517700982

- Uyarra, E., and K. Flanagan. 2010. “From Regional Systems of Innovation to Regions as Innovation Policy Spaces.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 28: 681–695. doi:10.1068/c0961

- Uyarra, E., K. Flanagan, E. Magro, J. Wilson, and M. Sotarauta. 2017. “Understanding Regional Innovation Policy Dynamics: Actors, Agency and Learning.” Politics and Space C 35 (4): 559–568. doi: 10.1177/2399654417705914.

- Vallance, P. 2016. “Universities, Public Research and Evolutionary Economic Geography.” Economic Geography 92 (4): 355–377. doi:10.1080/00130095.2016.1146076

- Weick, K. 1976. “Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems.” Administrative Science Quarterly 21: 1–19. doi:10.2307/2391875