ABSTRACT

The paper focuses on the changes to the industrial structure of small Moravian towns as these towns are part of the settlement structure that connects urban and rural systems. Small towns (of up to 15,000 inhabitants) are the most industrialized part of the Czech settlement system. They were the subject of capitalist industrialization in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as socialist industrialization in the second half of the twentieth century. Therefore, the research question asks how the small-town sector coped with the transition to a post-productive society and how small towns were differentiated during this process. Population censuses were the main tool used to gather data for comparison. Today, small towns have preserved, in particular, less innovatively demanding industries, which have been pushed out of large and medium-sized cities. At the same time, they are undergoing a process of post-productive transformation which is associated with a massive transfer of job opportunities to services, but they can also become starting points for cultural tourism in rural areas. However, their future development will be very differentiated depending on their location concerning regional centres, on the quality of human and social capital and also on their historical pathways.

1. Introduction

In the Moravian settlement system, small towns play an important role, especially concerning the surrounding rural settlements, ensuring jobs and services, social contacts and micro-regional identity. In the productive economy, the industry was the main source of jobs, especially in rural areas, and the Czech countryside is more industrialized than those of other European Union countries. Thus, industrial jobs in small towns were and still are extremely important, not only for the economy of the country but also for its rural development.

Of course, small towns, which are defined in this paper as towns with under 15,000 inhabitants, are different. Some of them were multifunctional at the end of the centrally planned economy, offering all kinds of urban activities, such as jobs, services and social life, while others were predominantly industrial. In extreme cases, towns that developed as a seat of a big factory can also be found. Another characteristic of the differentiation could be the character of the hinterland. Suburbanized industrial towns co-operate with big cities, while peripheral towns ensure complex urban services for their hinterland. Small towns in mining areas are coping with the post-mining situation, whereas small towns in intermediate regions are looking for a more specialist development.

At present, relatively important changes are impacting the small town sector (Steinführer, Vaishar, and Zapletalová Citation2016). The transition from an productive to a post-productive society is probably the most important one. The period is characteristic of extinction of mining and heavy industry, a decrease in the number, proportion and concentration of industrial jobs, and a notable increase in services and high-tech industries. Therefore, the research question in this paper asks how the small-town sector coped with the transition to a post-productive society and how small towns were differentiated during this process .

It should be noted that according to EUROSTAT, Czechia is the most industrialized EU country in terms of the share of employees. In 2019, 37% of employees were employed in this sector (followed by Slovakia with 36%). The EU average is 25%. Much of this industry is concentrated in small towns - after the industry was displaced from big cities. Therefore, the following article should be considered as an extreme case in a certain way.

2. Research review

As long as small towns were studied as part of urban system, not much attention was paid to them (Steinführer, Vaishar, and Zapletalová Citation2016). However, the situation is changing if looking at Europe's small towns as part of a rural area, especially in peripheral and sparsely populated territories (Jaszczak et al. Citation2021). In this case, small towns play a key role in rural sustainability and the cohesion at regional and local level.

The Czech situation was evaluated by Sýkora and Mulíček (Citation2014). They noted a dense network of small and medium-sized cities in Czechia, which contributes to territorial cohesion but at the same time hinders the creation of large poles of development. Small towns play an important role at the central (regional) level as well as at the local level as centres of functional regions and local action groups of the EU LEADER programme.

Eight years later, J. Bański (Citation2021) published a handbook that focused specifically on the theorethical, methodological and empirical aspects of small towns and their position in settlement systems. Korcelli-Olejniczak (Citation2021) believes that the small town sector will in future be affected by economic restructuring and the growing importance of quality of life. It will be differentiated on the basis of the relationship to higher centres on the one hand and natural attractions on the other, according to the use of local endogenous factors (social capital and levels of government) and the role of the public sector in supporting economic and social activities.

2.1. The role of industry in the small town sector

During the industrial revolution, towns were the places where industrial production was concentrated due to different localization factors. In the Czech context, two periods of industrialization have occurred. The first period was connected to the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century, which was based on the rules of a capitalist economy with free competition (Kemp Citation2013). Austria and Hungary lagged behind in their industrial development in comparison to western Europe (Poor and Basl Citation2018). However, the Czech lands became the most industrialized part of the monarchy. The main export sectors were the sugar industry, engineering and textiles (Rudolph Citation1976). After the First World War, these export industries were expanded to include the production of weaponsFootnote1 (Šťastná and Pavlík Citation2021). An important impetus for the industrialization of the formerly backward East Moravia was the activities of the shoe company Baťa in Zlín, which established branches in other cities, and became the overall industrial driver of the region .

Figure 2. Many of the contemporary industrial plants have their historical forerunners: the historic ironworks in Josef Valley (now a museum in Adamov).

The second period is connected with so-called socialist industrialization, which was based on the rules of a central-planned economy. The Czech industry shifted to heavy industry. At this time, big industrial plants with thousands of employees were also situated in small towns. The problem of restructuring single-industry towns remained a post-socialist heritage (Rubtsov and Litvinenko Citation2020). Industrialization was considered economically, and especially ideologically, a criterion of progress (Gomulka Citation1983).

The period after 1990 could be considered a period of industrial restructuring and deindustrialization and was connected with wild privatization that had very weak legislation (Kopačka Citation1994). The industrial structure changed again with a focus on the automotive industry, including components and accessories (Pavlínek Citation2008). However, this restructuring was largely achieved through the entry of direct foreign investments, while the Czech capital contributed only marginally (Rugraff Citation2010). Foreign investments were focused on labour-intensive sectors, where they used low prices and the experience of Czech industrial workers (Kippenberg Citation2005). The period after 1990 can be considered the beginning of another industrial revolution (4.0), connected with automation, computerization and digitization.

The deindustrialization of European countries is associated with rapid growth in the labour productivity, which has resulted in a global reduction in the share of jobs in the manufacturing sector. At the same time, there is a massive relocation of manufacturing industries to developing countries with significantly lower labour costs and weaker environmental legislation. However, it turns out that the trend for developed countries to get rid of an industry can be risky, and therefore, there is talk of re-industrialization (Peneder and Streicher Citation2018). This is largely because small towns will never be able to compete with large cities in tertiary functions (Pipan Citation2018).

The industrial character of small towns is often associated with a certain negative environmental image. This aspect was studied by Bole, Kozina, and Tiran (Citation2020) using Slovenia as an example. They concluded that there is little difference in the quality of life between industrial and non-industrial small towns. It seems that industry in small towns is not only a relic of the past but can also be a promising sector in the future. Wiedermann (Citation2015) even believes that after the transfer of major services to medium and large cities, the future of many small towns lies in industrial specialization.

2.2. Industry in the productive and post-productive society

Developed states are in the phase of transition from a productive (industrial, material, Fordist) to a post-productive (post-industrial, post-material, post-Fordist) society (Graham and Healey, Citation1999). The first is connected with production, the second more with consumption. A post-productive society is linked to the knowledge economy. The result is a reduction in the weight of manufacturing industries in employment and in the creation of national income. The problem is that the skills structure of the rural population, including small towns, is adapted to the lower value-added industries.

In the productive society, the secondary sector (industry) and the primary sector (agriculture, forestry and fisheries) are the leading branches impacting not only the localization of individual companies but also pre-conditioning migration movements and other processes. Heavy industry, including mining, iron and steel production and heavy chemistry, was the leading branch. Such industries were often situated in the areas of coal or oil mining, which transformed the whole settlement structure. Small towns in these areas often played the role of sub-centres or more often as residential areas within industrial agglomerations. These cities were looking for a new future that would change their economic focus (Krzysztofik, Kantor-Pietraga, and Kłosowski Citation2019).

Some new impulses have emerged, along with suburbanization. This is reflected not only in population growth on the outskirts of cities but also in the construction of industrial parks and businesses in small satellite towns (Kwiatek-Sołtys et al. Citation2014). The industry is often placed in these cities for better transport accessibility.

One of the variants of post-productive transformation is the development of the function of cultural tourism, using architectonical heritage or a spa function (Boleloucka and Wright Citation2020; Kwiatek-Sołtys and Bajger-Kowalska Citation2019). The process is sometimes called the touristification of small towns, which could be defined as places of memory, in direct contrast to large cities, which could be defined as places of change (Klusáková Citation2017).

Within the post-productive society, the situation has changed. The industry is no longer a sign of progress but a mark of regressive development. The centre of gravity is shifting to services. However, small towns have been oriented on rural workforces with a typical education structure and skills, oriented for productive activities. That is why the re-orientation of small towns for the post-productive society is theoretically slower than in big cities that are almost de-industrialized (except some high-tech branches). The decline of traditionally industrially oriented small towns was investigated by Lazzeroni (Citation2020) who uses the concept of resilience to analyse the future of towns with former industrial specialization.

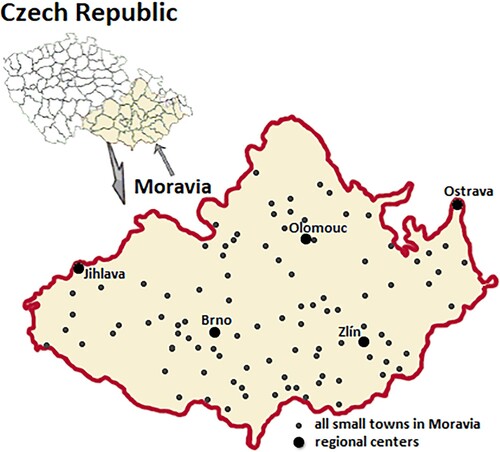

2.3. Small towns and their role in the Moravian settlement system

In the case of Moravia, small towns were defined as municipalities with an urban status and a population between 4,000 and 15,000 inhabitants in 2011. This lower limit excludes many municipalities in the Moravian lowlands that have 2,000–4,000 residents, but their character is rather rural, even though some of them have the administrative status of a town. The upper limit has been chosen because there is a natural gap in the size category of 15,000–20,000 inhabitants. District towns start at just over the limit of 20,000 inhabitants and due to their function in the settlement system, they can hardly be considered as small towns in Moravia.

It is possible to say that Moravia is a region of small towns. They mostly originated in the medieval ages as market places, later becoming centres of manors when the administrative function shifted from castles to towns. Being centres of manors, they started to develop industrial functions relatively early. As a result, Moravian small towns became industrial points and job centres for their rural hinterlands after the industrial revolution began in the second half of the nineteenth century.

In the period of a centrally planned socialist economy, which highlighted industry for both economic and ideological reasons, this industrial role of small towns mostly continued. Moreover, many new industrial factories were built, often using the pre-war tradition but sometimes creating a new one.

The dense network of small towns in Moravia is a very important factor in its rural development. From the majority of places within the Moravian territory, the closest small town can be reached by public transport within 30 min. This fact has predestined the very frequent commuting of rural people to industrial factories. As a result, the way of life for the rural population has started to be more and more urbanized and less dependent on the primary sector (agriculture, forestry and fisheries).

Has this role of small industrial towns continued into the period of transition to the post-productive economy? The first problem could be connected with the increasing mobility of the population. For rural people, medium towns are far more accessible. It seems that the micro-regional structure is overcome, especially in well accessible and passable regions. The second problem relates to the decreasing role of productive sectors, including industry within the post-productive transition. Large and medium-sized cities excluded industry, especially heavy industry, preferring more high-tech production. However, small towns are not able to follow this example because high-tech industries are usually connected with universities, research institutes and a highly qualified workforce. How are small towns coping with this new situation?

From 2012 to 2014, a consortium of companies led by the Catholic University of Louvain developed the ESPON project, which focuses on the role of small and medium-sized cities in the European territorial structure. The project aimed to answer questions about the role of small towns in the European territorial system as a provider of jobs and services of general interest, about obstacles and limits to their successful development and possible methods of management and cooperation of the small town sector (Servillo et al. Citation2014). The study notes the overall expected fact that the development of small (and medium-sized) cities depends on the demographic structure, the quality of the environment (which is the impetus for tourism development) and the sectoral structure of the economy, where a diversified SME structure is an advantage. From our experience, it is not very appropriate to place small and medium-sized towns in the same category, because medium-sized towns are more part of urban space, while small towns can be considered more of rural areas. The question, of course, is to define the boundaries between them, which can be specific in each state individually.

Industrial activities (and especially older plants and/or branch plants) are declining in small towns due to global competition, delocalization, concentration toward main urban areas. This constitutes a major potential threat for many mall towns. Czechia is one of the most industrialized countries in Europe. The question is what specifics the Czech small town sector has in the European context. In the period of real socialism, two circumstances played an important role. The first was the priority of social cohesion, which led the planning authorities to distribute industry evenly, including small towns where there were conditions for this, especially the workforce. The second circumstance was the implementation of the so-called centre settlement system, where housing construction and also services for rural service were located in small towns (usually centres of local importance). This led to a fairly even development of the system of small towns as centres of rural areas and to a satisfactory development of the Czech countryside, which as a whole does not suffer from depopulation. This can show the results of small town sector planning, of course, provided we avoid directive methods.

3. Methods of comparison

Small towns were defined not according to the total population of the administrative unit, but according to the population of the core seat (without associated small villages). The definition of a small town in this paper corresponds to a total of 58 items. Only 12 of them, after cleaning up the associated settlements, exceed the limit of 8,000 inhabitants in 2021. It could therefore be stated that a typical small Moravian town has between 4,000 and 8,000 inhabitants.

The structure of the research follows a historical pathway that compares the industrial role of small towns in the period of so-called socialist industrialization (around 1960), with the point of change, otherwise known as the transitional period, which is characterized by the year 1991, and the time after the transformation (2011).

Population censuses were the main tool used to gather data for comparison. The statistics were completed with an analysis of individual structures, such as the leading factory or factories, the branch of the industry and the size of enterprises. Such an analysis is aimed at observation of the industrial structures that are most resistant to various changes, with possible conclusions as to how industrial development impacts the development of individual towns and their rural hinterlands. There are databases from 1987 (the end of the socialist period) and 2001 (the period shortly after the transformation of property relations).

Industrial employment in small towns was assessed in relation to their current size (population in 2020) and location in relation to regional centres (Brno, Ostrava, Olomouc, Zlín and Jihava) measured by accessibility by road. This characteristic applies to the industrial employment of the inhabitants of small towns, regardless of whether they are employed in their city or whether they are leaving for work.

Accurate data on the number of employees of industrial enterprises located in individual cities are not publicly available and, in addition, relate to the registered headquarters of enterprises, not to establishments. Therefore, we will proceed on the basis of information on the estimated size of industrial companies. We assume that there are significant differences between cities located in one large industrial enterprise and cities that have a diversified structure of medium and small enterprises. We will relate this typology to the development of industrial employment over time.

Based on the findings, a certain typology of small towns was performed according to the size and structure of the companies. Based on the historical-geographical approach, it was observed how this typology developed in the next two monitored periods. Industrial employment, size (population) and distance from regional centres were put into context.

It is obvious that with the continuing transformation into a post-productive society, the number of workers employed in industry will decrease in general. It is therefore a question of what function could replace the industrial role of small towns. It is quite clear that this function will have to be sought in the services sector. We have chosen as a perspective the function of cultural tourism, which corresponds to the trends of labour transfer, the quality of cultural heritage of small towns and their function as centres of age.

4. Results

4.1. Industry in small towns during the socialist production (1960)

The period around 1960 can be considered the peak of industrial employment. This corresponds with the focus of the Czech economy within the CMEA, historical development and also ideological ideas about the importance of the working class. In contrast, the proportion of the population employed in agriculture had already begun to decline due to collectivization and the introduction of technology. The service sector was significantly underestimated at that time. Individual commercial service establishments were integrated into municipal or cooperative enterprises.

Industrial towns can be divided into several types according to the size and structure of companies (see ). Almost half of the small Moravian towns had at least one company with more than a thousand employees. It could be an extremely large company, whose number of employees was sometimes greater than the population of its own city, which determined the life of the whole city. In terms of industrial orientation, small towns could be divided into unilaterally oriented towns or diversified towns, and in extreme cases, they could even be factory cities. An example of a unilaterally oriented small town would be Adamov, where the leading company employed many workers greater than that of the town’s population. Almost all of the important activities took place in the factory, and the city had the character of a factory settlement rather than a small town. Another example would be Chropyně, with the leading company being Technoplast, a plastics production company with 2,541 employees, or Zubří, with the company Gumárny, a rubber industry company with 1,301 employees. At other times, they were two large companies in different industries, which could be supplemented by smaller companies. Most often, however, it was a combination of a large company and a number of small and medium-sized enterprises.

Table 1. Types of small Moravian towns according to the size and structure of companies.

The other half of the cities did not have any company with more than 1000 employees. Most of them relied on one to two medium-sized enterprises, complemented by a number of SMEs. Optimal cases in terms of future development were cities with a diversified structure of medium-sized enterprises in various sectors. Only a minimal number of cities had no company with 200 or more employees.

At that time, more than half of the cities in our group had more than 50% of the economically active population employed in the industry. Adamov, in the hinterland of Brno, represented an extreme value (82.9% of those employed in industry). Another 12 small towns had 60–80% employed in industry, among them Kuřim (70.5%), Zubří (69.8%) and Napajedla (67.5%). These are mostly small towns that are part of larger agglomerations where the role of a service centre is provided by another, usually larger city.

Eleven small towns recorded less than 40% of industrial employment. The extreme was represented by the most important Moravian spa town, Luhačovice (26.3%) and small towns that could be described as rural, such as Vracov (27.1%), Pohořelice (28.5%) and Hustopeče (29.9%). In some cases, it is possible to see a certain division of labour within the districts between the industrial centre and the service centre. Examples are Břeclav and Mikulov, Žďár nad Sázavou and Nové Město na Moravě, Blansko and Boskovice, and Holešov and Bystřice pod Hostýnem.

4.2. Industry in small towns in the transition period (1991)

Between 1960 and 1991, industrial employment was already declining. In most small towns, it fell by 10%. Only 20 small towns had more than 50% employment in the industry. The most numerous categories were small settlements with industrial employment in the range of 40–50%. Adamov (73.8%) still maintained its primacy ahead of Zubří (69.8%) and Chropyně (61.3%). However, industrial employment increased slightly in 11 small towns. In this way, the regime apparently wanted to prevent the objective process of reducing the representation of the working class in the structure of employment, which it began to realize in the late 1980s. On the other hand, industrial employment in Luhačovice fell below 20%. The towns of Pohořelice (23.6%), Rýmařov (30.1%), Vizovice (30.2%) and Telč (31.9%) also showed very low employment in the industry; however, still higher than in 1960 .

Figure 3. Moravian Electric Works in Brumov-Bylnice belongs to factories that disappeared from small towns after the end of socialism.

In 1987, there were 35 industrial enterprises with more than 1,000 employees in the small towns of our set. In some cases, the number of workers exceeded the population of these small towns. The largest company was LET Kunovice, an aircraft production company with 5,433 employees, followed by Adamovské strojírny Adamov, an arms industry company and producer of printing machines, with 5,006 employees. The next in line was the Machine Tools Factory Kuřim with 4,572 employees, then, Uničov Engineering Works with 4,564 employees and Moravian electrical works Mohelnice with 3,519 employees. Among these companies, the operations of the engineering, metalworking and metallurgical industries prevailed, often connected to arms production, with a total of 19 companies. Another four companies belonged to the electrical engineering industry and three to the clothing industry. However, other diverse industries were also represented in the form of textiles, building materials, ceramics, wood processing, chemicals, rubber and footwear.

In some cases, there is one large company with more than a thousand employees in a city, supplemented by several smaller companies with one or a few hundred employees. Such towns are for example Kuřim, Hustopeče, Dubňany, Strážnice, Uničov, Mohelnice, Kunovice, Brumov-Bylnice and Rýmařov. Sometimes, it is a pair of large companies supplemented by several small ones, in towns Boskovice (Minerva companies, sewing machine production and Karst, clothing production), Kyjov (OBAS, ceramics production and screwdrivers, metalworking industry), Napajedla (Fatra, chemical industry and Bohemian–Moravian Kolben Daněk Prague, engineering industry), Slavičín (Vlárské strojírny machinery and Svit Gottwaldov, shoemaking industry), Frýdlant nad Ostravicí (Ostroj Opava engineering and Norma, metal processing) .

Figure 4. Food-processing company Hamé belongs to new firms in small towns – here is the branch in Bzenec.

Other small towns had a diversified industrial structure. In this case, the industry was often represented by the location of branches of large companies situated in other places. Other sectors also come into play, such as the food, woodworking and paper industries. An example of this would be Zábřeh, where the companies Perla Ústí nad Orlicí, a textile industry company with 833 employees, Nová huť Klementa Gottwalda Ostrava, a metallurgy company with 775 employees, Hedva Moravská Třebová, another textile industry company with 621 employees, Moravské elektrotechnické závody Postřelmov with 435 employees, Czechoslovak Automobile Repair Shop Olomouc with 332 employees, Industrial Milk Nutrition Hradec Králové with 231 employees, North-Moravian Electric Works, substation Zábřeh with 220 employees, and Kovona Lysá nad Labem, a metalworking industry company with 159 employees were located, among others. Similarly, there were diversified industrial structures in other small Moravian towns, including Letovice, Ivančice, Holešov, Uherský Brod, Velké Meziříčí, Moravská Třebová and others. Within the planned economy, industrial diversification was more important in terms of the structure of the workforce, most often for a balanced structure of male and female job opportunities.

In any case, at the end of the socialist period, industry in small towns in Moravia was an extremely important sector, both in terms of economy and employment, even though job losses in this sector were already beginning to show.

4.3. Role of the transformed industry in small towns (2011)

Twenty years later, the situation looked significantly different. If we wanted to use the typology of cities according to the size and structure of companies, the first two categories would disappear. Only seven cities have a company with more than a thousand employees. An exception is Frenštát pod Radhoštěm, which has two factoriesof the same multinational company SIEMENS. The most common types of industrial cities are those that have one to two medium-sized enterprises, possibly supplemented by small companies. Five cities with a diversified medium-sized enterprise structure remained. However, the number of cities that have no company with 200 or more employees has increased significantly (to 15). Their industrial structure consists of small businesses.

In the meantime, the transformation of ownership relations in the Czech industry had taken place. Several companies disappeared and many medium-sized and small enterprises were established on the ruins of the original structure. The sectoral structure and export directions also changed. Foreign capital entered many companies. Vaishar and Zapletalová (Citation2021) state that employment in the industry was inversely proportional to the size category of municipalities in the 2011 census. It was highest in rural settlements, followed by small towns.

It is noteworthy that the vast majority of those employed in industry have been between 30 and 50%. Zubří (53.1%) and Mohelnice (50.2%) have slightly over 50% of those employed in the industry. Only Náměšť nad Oslavou (25.3%) and Luhačovice (28.5%) have a level of employment in the industry below 30%. Despite a significant decline in industrial employment, in five small Moravian towns during the transformation to a market economy, industrial employment increased. These towns were Pohořelice, Rýmařov, Telč, Vizovice and Vracov.

Despite a significant decrease in the number of large enterprises and the number of employees in the survivors, in 2001 there were still 11 enterprises with more than 1,000 employees in Moravian small towns. The largest of them were Siemens Mohelnice, with 2,241 employees, UNEX (formerly Uničovské strojírny) Uničov, with 2,227 employees, Česká zbrojovka Uherský Brod, with 2,051 employees, Tyco Electronic, a new company with US capital, built on a greenfield in Kuřim, with 1,812 employees, and ADAST Adamov, with 1,453 employees. Another 19 companies in small Moravian towns employed between 500 and 1,000 employees.

The position of some small towns changed dramatically. Cities where a large industrial enterprise disappeared often lost their industrial character. Other small towns became industrial centres, often with a diversified structure. Examples of small towns that became the headquarters of a diversified structure of medium-sized enterprises would be Velké Meziříčí, Boskovice and Hustopeče. The industrial structure of other small towns is based on a pair of larger companies, sometimes supplemented with smaller companies. Examples include Dačice (TRW DAS and Centropen), Nové Město na Moravě (Medin and Sporten), Veselí nad Moravou (ironworks and Penta Shoe) and Frenštát pod Radhoštěm (two Siemens factories).

After the year 2000, industrial zones and industrial parks began to develop. The diversified structure of small businesses required entrepreneurs to have facilities and land with at least a basic infrastructure. As a rule, local entrepreneurs did not have the capital, and foreign entrepreneurs hardly had the motivation to start small and medium-sized enterprises in small towns. That is why the municipalities were initially involved, offering industrial zones to new entrepreneurs, either in abandoned production areas or elsewhere, for example in the abandoned barracks of the Czechoslovak and Soviet armies. Sometimes, the municipalities invested in production zones in greenfield sites on the outskirts of their cities. The structure of small businesses quickly emerged in these areas and was very variable. Business owners and their places of operation changed, and businesses were established and disappeared. However, this is a sign of higher resilience through rapid changes in industrial structure in response to changing conditions.

Later, important developers began to build so-called industrial parks, many of which were situated in small towns with a convenient location for transport. The largest industrial park (280 ha) among our set of towns is situated at the former airport of Holešov. CT Park Modřice (47 ha), south of Brno, is better known. Other parks are in locations such as Bučovice, Bystřice nad Pernštejnem, Šlapanice, Hulín, Kunovice, Lipník nad Bečvou, Litovel, Staré Město, Šternberk, Uničov and Zábřeh .

The number of active industrial companies at the end of 2020 was used to estimate the current situation. Most of them are small companies, but there may also be medium and large companies among them. The proportion of industrial companies in the total number of enterprises ranges from 13.5% in Tišnov to 25% in Bzenec. In most cases, however, the proportion of these companies is just below 20%, which probably corresponds to supply and demand.

The number of active industrial companies per thousand inhabitants in individual small towns fluctuates around 20. The smallest numbers of companies (14–15 per thousand inhabitants) are recorded by the largest of small towns in Central Moravia, such as Mohelnice, Zábřeh and Uničov, where higher numbers of companies and services can be expected. These include the formerly expressly industrial Adamov. Conversely, the most industrial companies per thousand inhabitants are found in Eastern Moravia: Napajedla (38), Hluk (32), Staré Město (32), Valašské Klobouky, Bzenec and Vizovice (30). In these cases, it is possible to speculate about the relative lack of business in other sectors but also about the remnants of the business atmosphere from the Baťa period. These cities also include Modřice, south of Brno, which has 32 industrial companies per thousand inhabitants.

Industrial employment in small towns was linked to the size of the town and to their location in relation to regional settlement centres. Suburban centres were characterized by reachability of regional centres within 25 min, intermediate accessibility by 26–35 min, peripheral 36–45 min and extremely peripheral over 45 min. The results can be found in the .

Table 2. Numbers of cities by level of industrial employment (2011), by population of cities (2011) and by distance from regional centres Source: Population census 2011. Praha: Czech Statistical Office. Distances according to mapy.cz. Own elaboration.

Although the numbers of small towns in our file do not allow the use of statistical methods, the data still show some facts. It turns out that smaller small towns and rather peripheral and extremely peripheral small towns have higher industrial employment. This corresponds to the assumption that in the process of transition to a post-productive society, industrial employment is becoming more of a rural phenomenon. Suburban small towns can to some extent copy employment in their centres. Small towns around Brno have low industrial employment in favour of services. Small towns in the background of other regional centres tend to be industrial satellites of regional centres.

4.4. An alternative role for small Moravian towns: cultural tourism

The analysis so far has shown that industry remains an important part of the economy and life of small towns in Moravia. The question is what alternative activity could be developed in these cities in addition to the standard functions of serving the population of the city itself and the villages in its hinterland. This paper argues that this function could be tourism, especially in its cultural form.

Almost all of the towns in our set were developed from the centres of medieval estates. This means that they usually have some aspect of cultural heritage in the form of a castle or chateau with a garden, a major church or town hall, or other historic buildings. Of course, this depends on their eventual destruction by war, disasters or insensitive reconstruction. Many small towns in Moravia also dispose of Jewish heritage. Most cities of this size also have museums, whether local history or more specialized.

Telč, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, enjoys the highest level of protection. The other four towns are urban conservation areas: Lipník nad Bečvou, Mikulov, Moravská Třebová and Příbor. Urban monument zones can be found in 27 small Moravian towns. So, half of the towns in our set have historical parts (usually at the core) that are protected by the state. In other towns, individual buildings are usually protected.

Some small Moravian towns also have monuments of Jewish cultural heritage. The Jews came to these towns in several waves after their expulsion from the royal cities. Since they were not allowed to own land, it made no sense for them to take refuge in the countryside. In small towns, they engaged in trade, partly in crafts. The nobles, who usually owned small towns, tolerated them because the Jews became a source of financial loans for them (with limited ability to enforce their return). Jewish monuments are located in at least 20 small Moravian towns. It is usually a synagogue (now serving other purposes) and a cemetery. A well-preserved Jewish ghetto can be found, for example, in Boskovice .

The most sought-after attractions of cultural tourism in small Moravian towns include Mikulov Chateau (126,000 visitors in 2019), Slavkov u Brna Chateau (102,000 visitors), technical monuments and the Permonium amusement park in Oslavany (40,000 visitors), Kunovice Aviation Museum (39,000 visitors), castle Šternberk (34,000 visitors), chateau Letovice (25,000 visitors), chateau Vizovice (23,000 visitors) and the open-air museum in Strážnice (22,000 visitors).

Other elements of cultural tourism can be cultural and memorial events, and in South Moravia, there are also events connected with wine culture and folklore traditions. The most important folklore festival takes place in Strážnice. Among the events of cultural significance, the anniversary of the Battle of Austerlitz (Slavkov) can be included. There are also technical monuments and open-air museums.

The current importance of tourism can be estimated from the share of employees in the field of catering and accommodation. The national share of workers in these sectors was 3.1% in 2011. Of the entire set of small Moravian towns, only 16 had more than 3% of economically active people employed in catering and accommodation services, and thus, reached average or above-average values compared to the national average. Luhačovice (9.6%) had the highest share of these people, followed by Mikulov (6.1%) and Slavičín (4.3%). The current situation can be estimated from the number of overnight stays in the last pre-COVID-19 year (2019). The most overnight stays were reported by Luhačovice (598,000), followed by Mikulov (200,000), Nové Město na Moravě (64,000), Strážnice (50,000), Hustopeče (49,000), Frenštát pod Radhoštěm (42,000), Telč (33,000) and Boskovice (32,000). On the other hand, 14 cities had less than 10,000 overnight stays, and in another 14 cities, the statistics did not record any overnight stays.

It is obvious that the tourist function is developed only in a few small towns in Moravia. Mura and Kajzar (Citation2019) state that so far there is no statistically significant relationship between the number of cultural tourism attractions and the number of visitors to individual monuments. This would mean that there is no multiplier effect. They attribute this to underdeveloped tourist infrastructure. However, the interest of tourists in learning about the historical and cultural values of their own country and foreign countries is growing, which creates conditions for the development of cultural tourism in most of the small Moravian towns (Rudan Citation2010). Efforts should be focused on place marketing, branding, heritage and creativity (Besana, Esposito, and Vannini Citation2020). Sometimes, a concept of ‘cittaslow’Footnote2 can be used, which would distinguish them from big cities with their hustle and bustle (Zawadska Citation2017). On the other hand, in Czech conditions, we consider small towns as centres of local importance to be necessary for the sustainable development of the surrounding countryside. They should therefore, if possible, be living centres of their hinterlands. The cittaslow concept is more suitable for small towns, which for various reasons have lost their central importance.

Of course, cultural tourism cannot replace job losses in industry. That sector must be services in general. However, cultural tourism may be the sector that triggers further service activities in general and improves the image of the small town. Through cultural tourists, the inhabitants of small towns come into contact with the world, while retaining their own identity (Beal et al. Citation2019). This can have implications for their quality of life.

5. Discussion

It has already been stated that the optimal places for locating less innovative branches of industry, which are not tied to universities or scientific and technical institutions, are small towns that have the workforce of the Moravian countryside, i.e. medium-skilled and experienced workers with appropriate levels of motivation. The problem may be in this job goal. At present, the Czech industry lacks about 300,000 skilled workers. Businesses seek to address this situation by importing labour from abroad, often through agency workers (Morén-Alegret and Wladyka Citation2020). However, they should really be qualified workers, able to accept domestic work and general culture. The Czech authorities are very careful when granting a long-term residence permit or granting citizenship to foreigners. That is why the citizens of the EU, such as the Slovaks, Poles and Romanians, come into consideration. Thus, a lack of skilled labour force may be a significant problem for the sustainability of the industrial structure of small Moravian towns, possibly in combination with social destabilization caused by a larger number of agency workers. The lack of a qualified workforce may also be the reason why industrial employment and industrial business in individual small towns in Moravia are rather converging. If the availability of manpower is an important motive for location, companies look for locations where there is still little industry and leave cities where there is no more free labour for the sector. Dozens of thousands of refugees from Ukraine are currently heading to Moravia, including small towns, who could potentially be a solution. Some of them will certainly stay in Czechia. However, it should be borne in mind that the vast majority are women with small children or the elderly, whose importance for the labour market is less than would correspond to their number.

As for the alternative development opportunity in the field of cultural tourism, it turns out that the existing potential is very little used in comparison with small towns im Mediterranean countries or in Western Europe. There is a lack of relevant infrastructure, experience, cooperation and promotion. A possible impetus could be the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused a turn towards domestic tourism. Even if we admit that some, especially cultural tourists, undertake optional trips with accommodation in larger cities and that second housing is certainly involved in accommodation, the occupancy of which is not included in the statistics, the potential of tourism in the vast majority of small Moravian towns is insufficiently used. In addition, health tourism, sports tourism, wine tourism and trips to the surrounding countryside seem to contribute to overall turnover, while the potential of cultural tourism remains almost untapped. It can be assumed that the role of culture will grow in the near future. This will undoubtedly be reflected in small towns (Lysgård Citation2019).

The findings of Czapiewski, Bański, and Górczyńska (Citation2016), according to which peripheral small towns proved more resilient to change than suburbanized small towns around the metropolis, did not fully manifest themselves. Small towns in the vicinity of Brno, Olomouc and other Moravian centres often not only preserved, but also expanded their industrial function and, in connection with it, a service role in the division of functions within the metropolis. Peripheral small towns are, of course, irreplaceable as centres of their hinterlands, while their industrial development is struggling with poorer accessibility (Vaishar and Zapletalová Citation2009). The last demographic development shows that the population increase is directly proportional to the distance from the regional metropolis and inverse to the size of small towns (Vaishar, Šťastná, and Stonawská Citation2015). Smaller small towns are closer to the rural environment, where the proportion of the population has been growing over the last 25 years. Industrial small towns are also proving to be growing faster than service-oriented small towns.

When evaluating the prospects of small towns, it is necessary to take into account what we mean by development. It does not always have to be about growth (population, houses, job opportunities, etc.). We will keep in mind rather qualitative development, in which small towns (regardless of a possible slight decrease in the number of inhabitants) would continue to fulfil their functions and ensure a high quality of life for their inhabitants. The term smart shrinkage is used for this development (Peters et al., Citation2018) in the European cotext. EU cohesion policy focuses on urban regions and assumes that these regions are responsible for developing their rural background (Rauhut and Humer Citation2020). However, large cities could hardly be responsible for the rural development in their vicinity if they could not rely on a dense network of small towns.

6. Conclusions

This paper shows that the small town sector in Moravia responded to the post-productive transition quite successfully by changing the structure of an industry in favour of diversification and shifting the weight of the sector to small and medium-sized enterprises with an expected significant reduction in the number of industrial workers. However, industrial employment in Moravian small towns is still high. This is mainly because it is based on a high ground of the Czech industry acquired historically as an industrial base of Austria-Hungary and later CMEA. This characteristic has considerable inertia, influenced, among other things, by the specific qualification structure of the rural population.

Contrary to expectations, there was no high differentiation, but the small towns that were studied levelled to a similar standard. It seems that an alternative activity using the existing heritage for cultural tourism has either not yet been seriously considered or the conditions are not suitable for it.

It can be concluded that small towns in the range of 4,000–15,000 inhabitants in historic Moravia continue to be and will remain industrial centres shortly, although at a lower level than in the second half of the last century. This is the only sector in which they can compete with both large cities and villages. The main factor in maintaining this role will be the human factor, namely its ability to accept and develop the 4.0 economy, which means strengthening contacts with research and development institutions. However, these are located in large cities. It is necessary to realize that the Industrial Revolution 4.0 does not consist of the availability of technologies, but of the preparation of human capital to use these technologies. To some extent, it is a question of formal education, not only the proportions of the educated population but also the fight against declining levels of education, often for populist reasons. Equally important is maintaining a level of motivation that can be based on the industrial tradition of small towns and the family traditions of workers. In this respect, there has been significant damage in the last 30 years, when industrial occupations were considered less valuable. Continuing to focus on quality and a cheap labour force could be fatal, as it can lead to reduced quality and higher labour costs.

Of course, current developments can be re-examined when the results of the 2021 census become available. It is also a question of the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences will be felt. Theoretically, the post-COVID-19 situation could be characterized by the accelerated development of the 4.0 industry, for which conditions are hampered in small towns and less closely linked to innovative approaches (Poor and Basl Citation2018). At the same time, it is a question for further research whether small and medium-sized cities can play a similar stabilizing role in the settlement system as small and medium-sized enterprises do in the economic structure of cities and regions. However, the flexible structure of smaller businesses in small towns could be an advantage. The concept of borrowed size should be applied, where small towns would have access to the research infrastructure of regional metropolises (Phelps, Fallon, and Williams Citation2001). This would not necessarily be a problem with the density of the urban network in Moravia.

Acknowledgement

This paper is one of the results of the HORIZON 2020 project Social and Innovative Platform On Cultural Tourism and its Potential Towards Deepening EuropeanisationFootnote3, ID 870644, funding scheme Research and Innovation action, call H2020-SC6-TRANSFORMATIONS-2019.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The arms industry appeared in small Moravian towns before the Second World War. Because all large Czech armories would be in imminent danger of attacks by German bombers taking off from Austria and landing in Silesia (or vice versa) in the event of a conflict, each armoury was obliged to build one or two subsidiaries on both sides of the Moravian–Slovak border, where they would be more protected from air raids and where the Czechoslovak army was to withdraw during the retreat.

2 Cittaslow's goals include improving the quality of life in towns by slowing down its overall pace, especially in a city's use of spaces and the flow of life and traffic through them

References

- Bański, J. ed 2021. The Routledge Handbook of Small Towns. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Beal, L., H. Séraphin, G. Modica, M. Pilato, and M. Platania. 2019. “Analysing the Mediating Effect of Heritage Between Locals and Visitors: An Exploratory Study Using Mission Patrimoine as a Case Study.” Sustainability 11, doi:10.3390/su11113015.

- Besana, A., A. Esposito, and M. C. Vannini. 2020. “Small Towns, Cultural Heritage, … Good and Evil Queens.” In Cultural and Tourism Innovation in the Digital Era, edited by V. Katsoni, and T. Spyriadis, 89–99. Cham: Springer.

- Bole, D., J. Kozina, and J. Tiran. 2020. “The Socioeconomic Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Industrial Towns: Slovenian Perspectives.” Moravian Geographical Reports 28 (1): 16–28. doi:10.2478/mgr-2020-0002.

- Boleloucka, E., and A. Wright. 2020. “Spa Destinations in the Czech Republic: An Empirical Evaluation.” International Journal of Spa and Wellness 3 (2-3): 117–144. doi:10.1080/24721735.2021.1880741.

- Czapiewski, K., J. Bański, and M. Górczyńska. 2016. “The Impact of Location on the Role of Small Towns in Regional Development: Mazovia, Poland.” European Countryside 8 (4): 413–426. doi:10.1515/euco-2016-0028.

- Gomulka, S. 1983. “Industrialization and the Rate of Growth: Eastern Europe 1955–75.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 5 (3): 388–396. doi:10.1080/01603477.1983.11489378.

- Graham, S., and P. Healey. 1999. “Relational Concepts of Space and Place: Issues for Planning Theory and Practice.” European Planning Studies 7: 623–646. doi:10.1080/09654319908720542.

- Jaszczak, A., G. Vaznoniene, K. Kristianova, and V. Atkociuniene. 2021. “Social and Spatial Relation Between Small Towns and Villages in Peripheral Regions: Evidence from Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia.” European Countryside 13 (2): 242–266. doi:10.2478/euco-2021-0017.

- Kemp, T. 2013. Industrialization in Nineteenth-Century Europe. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Kippenberg, E. 2005. “Sectoral Linkages of Foreign Direct Investment Firms to the Czech Economy.” Research in International Business and Finance 19 (2): 251–265. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2004.12.004.

- Klusáková, L. 2017. Small Towns in Europe in the 20th and 21st Centuries (ed.). Praha: Karolinum.

- Kopačka, L. 1994. “Industry in the Transition of Czech Society and Economy.” GeoJournal 32: 207–214. doi:10.1007/BF01122110.

- Korcelli-Olejniczak, E. 2021. “Small Towns in Settement Systems. A Return to the Foreground?” In The Routledge Handbook of Small Towns, edited by J. Bański. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Krzysztofik, R., I. Kantor-Pietraga, and F. Kłosowski. 2019. “Between Industrialism and Postindustrialism—the Case of Small Towns in a Large Urban Region: The Katowice Conurbation, Poland.” Urban Science 3 (3): 68. doi:10.3390/urbansci3030068.

- Kwiatek-Sołtys, A., and T. Bajger-Kowalska. 2019. “The Role of Cultural Heritage Sites in the Creation of Tourism Potential of Small Towns in Poland.” European Spatial Research and Policy 26 (2): 237–255. doi:10.18778/1231-1952.26.2.11

- Kwiatek-Sołtys, A., K. Wiedermann, H. Mainet, and J. C. Edouard. 2014. “The Role of Industry in Satellite Towns of Polish and French Metropolitan Areas – Case Study of Myślenice and Issoire.” Prace Komisji Geografii Przemysłu Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego 25: 194–211.

- Lazzeroni, M. 2020. “Industrial Decline and Resilience in Small Towns: Evidence from Three European Case Studies.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 111: 182–195. doi:10.1111/tesg.12368.

- Lysgård, H. K. 2019. “The Assemblage of Culture-led Policies in Small Towns and Rural Communities.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 101: 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.019.

- Morén-Alegret, R., and D. Wladyka. 2020. International Immigration, Integration and Sustainability in Small Towns and Villages: Socio-Territorial Challenges in Rural and Semi-Rural Europe. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Mura, L., and P. Kajzar. 2019. “Small Businesses in Cultural Tourism in a Central European Country.” Journal of Tourism and Services 10 (19): 40–54. doi:10.29036/jots.v10i19.110.

- Pavlínek, P. 2008. A Successful Transformation? Restructuring of the Czech Automobile Industry. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag.

- Peneder, M., and G. Streicher. 2018. “De-industrialization and Comparative Advantage in the Global Value Chain.” Economic Systems Research 30 (1): 85–104. doi:10.1080/09535314.2017.1320274.

- Peters, D. J., S. Hamideh, K. Elman Zarecor, and M. Ghandour. 2018. “Using Entrepreneurial Social Infrastructure to Understand Smart Shrinkage in Small Towns.” Journal of Rural Studies 64: 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.10.001.

- Phelps, N. A., R. J. Fallon, and C. L. Williams. 2001. “Small Firms, Borrowed Size and the Urban-Rural Shift.” Regional Studies 35 (7): 613–624. doi:10.1080/00343400120075885.

- Pipan, T. 2018. “Neo-industrialization Models and Industrial Culture of Small Towns.” GeoScape 12 (1): 10–16. doi:10.2478/geosc-2018-0002.

- Poor, P., and J. Basl. 2018. “Czech Republic and Processes of Industry 4.0 Implementation.” In Proceedings of the 29th DAAAM International Symposium, edited by B. Katalinic, 0454–0459. Vienna: DAAAM International.

- Rauhut, D., and A. Humer. 2020. “EU Cohesion Policy and Spatial Economic Growth: Trajectories in Economic Thought.” European Planning Studies 28 (11): 2116–2133. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1709416.

- Rubtsov, G., and A. Litvinenko. 2020. “Development of Single-Industry Towns as a Factor of Economic and Regional Growth.” E3S Web of Conferences 208: 08005. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202020808005.

- Rudan, E. 2010. “The Development of Cultural Tourism in Small Historical Towns.” In Tourism & Hospitality Management Conference Proceedings, edited by J. Perić, 577–586. Rjeka: University of Rjeka.

- Rudolph, R. 1976. Banking and Industrialization in Austria-Hungary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rugraff, E. 2010. “Foreign Direct Investment (fdi) and Supplier-Oriented Upgrading in the Czech Motor Vehicle Industry.” Regional Studies 44 (5): 627–638. doi:10.1080/00343400903095253.

- Servillo, R., R. Atkinson, I. Smith, A. Russo, L. Sýkora, C. Demazière, and A. Hamdouch. 2014. TOWN. Small and Medium Sized Towns in Their Functional Territorial Context [Final Report]. Luxembourg/Louvain-la-Neuve: ESPON/Katolieke Universiteit Louvain.

- Steinführer, A., A. Vaishar, and J. Zapletalová. 2016. “The Small Town in Rural Areas as an Underresearched Type of Settlement. Editors’ Introduction to the Special Issue.” European Countryside 8 (4): 322–332. doi:10.1515/euco-2016-0023.

- Sýkora, L., and O. Mulíček. 2014. TOWN. Small and Medium Sized Towns in Their Functional Territorial Context [Case Study Report Czech Republic]. Luxembourg/Louvain-la-Neuve: ESPON/Katolieke Universiteit Louvain.

- Šťastná, S., and A. Pavlík. 2021. “Evolutionary Trajectories of Manufacturing Firms in the Rural Zlín Region of Czechia.” AUC GEOGRAPHICA 56 (2): 144–156. doi:10.14712/23361980.2021.8.

- Vaishar, A., M. Šťastná, and K. Stonawská. 2015. “Small Towns - Engines of Rural Development in the South-Moravian Region (Czechia): An Analysis of the Demographic Development.” Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 63 (4): 1395–1405. doi:10.11118/actaun201563041395.

- Vaishar, A., and J. Zapletalová. 2009. “Small Towns as Centres of Rural Micro-Regions.” European Countryside 1 (2): 70–81. doi:10.2478/v10091-009-0006-4.

- Vaishar, A., and J. Zapletalová. 2021. “Small Towns in Rural Space. The Case of Czechia.” In Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Small Towns, edited by J. Bański, 254–267. London: Routledge.

- Wiedermann, K. 2015. “The Role of Industry in the Labour Market of Small Towns.” Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis Studia Geographica 8: 67–79.

- Zawadska, A. K. 2017. “Making Small Towns Visible in Europe: The Case of Cittaslow Network – the Strategy Based on Sustainable Development.” Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences (special issue): 90–106. doi:10.24193/tras.SI2017.6.