ABSTRACT

Central governments are increasingly preoccupied with problems of regional development, ranging from political discontent to sustainability transitions. New development funds are unfolded with different rationalities about what spatially just redistribution is. This paper aims to uncover in what ways issues are problematized in regional development policies, in which normative principle of redistributive justice the policy problem is primarily grounded, and how this affects regional development investments. This study critically examines an empirical case of policy for regional development in the Netherlands: the Region Deals (Regio Deals). The findings show that even though Dutch central government discursively problematized people who are left behind in the progress of the country, this priority was not maintained for places that are left behind. The Dutch case exemplifies that government rationalities about ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ regional development are a crucial factor to which regions benefit most from redistribution. Yet these rationalities are underexposed and inconsistently articulated in policy documents and political discourse.

Introduction

Problems of regional development are high on the agenda in Europe. Both in academic circles and in political arenas there are concerns over the rise of discontent in disadvantaged regions, which poses a threat to political stability in liberal democracies throughout Europe (Gordon Citation2018; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018; Florida Citation2021; McKay, Jennings, and Stoker Citation2021). At the same time regions are forced to take action on climate adaptation and sustainability transitions (EU Citation2020; OECD CFE Citation2020), not in the least in rural and old-industrial areas. Many national governments are revising regional redistribution and are puzzling with designing the ‘right’ policy for regional development. New development funds are unfolded with different redevelopment strategies, such as the ‘levelling up’ approach in the UK (Tomaney and Pike Citation2020; Martin et al. Citation2021) or the ‘Region Deals’ in the Netherlands (Den Hoed Citation2021; ROB Citation2022). This paper takes a critical look at what government perceives as just and unjust regional development, and how this affects the allocation of regional investments.

The literature on the geography of discontent points out that current regional divides exist from a combination of unequal distribution of economic disadvantages such as low incomes and high unemployment levels, sociodemographic differences such as ageing and accessibility of public services, and cultural resentments such as clashing lifestyle preferences (see Cramer Citation2016; Essletzbichler, Disslbacher, and Moser Citation2018; Wuthnow Citation2018; Dijkstra, Poelman, and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2020; Maxwell Citation2020; Florida Citation2021; Harteveld et al. Citation2021; Mitsch, Lee, and Ralph Morrow Citation2021; Van Leeuwen, Halleck Vega, and Hogenboom Citation2021). But what about the role of central government? Not only can political neglect of places (re)produce regional inequality, it can also prompt people to feel their region is overlooked and ignored by government (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018). Studies about the US and the Netherlands show that feelings that one’s region is not receiving a fair share of government investments is a substantial source of regional resentment, and that these feelings are most prominent in rural and peripheral areas (Cramer Citation2016; De Lange, van der Brug, and Harteveld Citation2022).

This paper is seeking what issues are problematized in regional development policies, in which normative principle of redistributive justice the policy is grounded, and how this affects regional development investments. In doing so, I draw upon a normative theory of spatial justice, which makes explicit the relation between territorial inequality and policy decisions (e.g. Jones et al. Citation2019; Papadopoulos Citation2019; Woods Citation2019; Madanipour, Shucksmith, and Brooks Citation2021; Petrakos et al. Citation2021; Shucksmith, Brooks, and Madanipour Citation2021; Weck, Madanipour, and Schmitt Citation2021). That what central government proposes as ‘wrong’ in regional development and envisions as the ‘right’ plan to fix it has important implications for which regions benefit from the investments, and for people’s perception of whether their region receives a fair share.

This study selected an empirical case of a relatively novel policy approach to sustainable redevelopment at the regional scale in the Netherlands. In 2018 the national government of the Netherlands introduced a new regional policy programme titled the ‘Region Deals’ (Regio Deals). A critical policy analysis is conducted following the ‘What’s the Problem Represented to be?’ (WPR) approach (Bacchi Citation2009). The WPR approach is a Foucauldian method that specifically interrogates the ways in which policies constitute ‘problems’ to be ‘solved’, which enables to uncover government rationale about what is just and what is not. In regards to the Region Deal (RD) policy this paper questions: (1) what is proposed as the problem (2) what are the underlying normative premises and (3) which regions (do not) benefit from the investments?

The paper begins by discussing the theory of spatial justice and explicating four principles of (re)distributive justice. The next section elaborates on the details of the policy analysis and the data collection of this research. Subsequently, the paper explains the Dutch history of regional development policies. This is followed by the findings section and a conclusion.

Theory

Spatial justice

Spatial justice originated from geographical engagement with social justice. Social justice is about fairness and morality, our beliefs about what is right. In the late twentieth century, geographers first started to criticize the notion of social justice for having a blind spot for territorial features and spatial conditions (Smith Citation2000; Shucksmith, Brooks, and Madanipour Citation2021). Geography created a new spatial consciousness in seeking justice (Soja Citation2010). Critical geographers illuminated that injustices between areas are the product of human action and political decision-making (see Pirie Citation1983; Lefebvre Citation1996; Harvey Citation2009). Geographies are produced by political actors who make imaginative and administrative borders, scales and territories (Foucault Citation2007).

(Un)just geographies were – and still are – predominantly addressed in relation to global inequality (e.g. Wallerstein Citation1974; Friedmann and Wayne Citation1977) and later to urban inequality (e.g. Lefebvre Citation1996; Wacquant Citation2008; Harvey Citation2009; Fainstein Citation2015; Moroni Citation2020). In the last years, several scholars started to include rural and regional inequalities in investigating spatial justice (e.g. Carolan Citation2019; Jones et al. Citation2019; Woods Citation2019; Van Vulpen and Bock Citation2020; Shucksmith, Brooks, and Madanipour Citation2021; Weck, Madanipour, and Schmitt Citation2021). Even though policies for place-based development were examined, there is little attention to the effects of different orientations towards a just distribution of central government investments across regions.

Principles of (re)distributive justice

Following the triparte understanding of philosopher Fraser (Citation2009), justice revolves around three interrelated axes of (re)distribution, recognition and representation (see Van Vulpen and Bock Citation2020). In this paper, we focus specifically on redistribution, more specifically (re)distributive principles in regional development arrangements. Distribution traditionally covers how benefits are distributed across people/places and the redistribution by means of public resources: who gets what and where?

This section elaborates on normative, or political, perspectives on justice grounded in classic philosophical theories on (re)distribution. We can speak of, in Rawlsian terms, reasonable pluralism comprising a ‘family’ of normative principles of justice (Peter Citation2007). Inspired by the work of Buitelaar and colleagues (Buitelaar, Weterings, and Ponds Citation2017; Needham, Buitelaar, and Hartmann Citation2018; Buitelaar Citation2020; Evenhuis, Weterings, and Thissen Citation2020), which brings forward a comprehensible set of normative perspectives of justice, I highlight four principles of (re)distributive justice here. See for an overview.

Table 1. Conceptions of (re)distributive justice.

The school of utilitarianism argues that a just society is governed through establishing maximum wellbeing to the greatest number of people. The principle of utility comes from well-known philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill (Warnock Citation2003). Utilitarianism intends to grow the pie as a whole, and in that case justifies a skewed distribution of the pieces of pie. Disadvantages for a minority are accepted if it is in the best interest of the majority. From an utilitarian perspective state interventions should contribute to maximizing wellbeing. Taking this orientation in a regional context, regimes with a pro-growth agenda typically bet on their ‘strong horses’ or ‘national champions’ to compete internationally (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002; Crouch and Le Galès Citation2012).

In the case of egalitarianism, equality is seen as the highest form of social justice. Egalitarian justice advocates a society with an even distribution of material goods and wellbeing (Nielsen Citation1979). Marxism is built on the principle the more equal, the more just. Spatial evenness is considered to be just, whether it is within a city, region, nation, or on a global scale. In this school of thought, communities, or geographies, are mostly criticized for uneven distribution of income and capital (Harvey Citation2009). From an egalitarian viewpoint, government should always aim to reduce relative deprivation. Regional policy, thus, typically problematizes regional inequality (e.g. Molema Citation2012).

Sufficientarianism on the other hand focuses on absolute deprivation rather than relative deprivation. Accordingly, a just society is designed to guarantee everyone a minimum standard of living (Frankfurt Citation1987). Inequality is not problematized, only if an absolute norm of sufficiency is violated. Not everyone should have the same but each should have enough (Ibid.). From that perspective, it is deemed important that sufficient resources, facilities and services are provided to people, no matter where they live. This can be done by introducing minimum standards for employability, affordable housing, internet speed or accessibility to public services. German spatial planning law, for instance, stipulates comparable living conditions across all areas. The sufficientarian principle revolves around bringing regions up to standard.

Prioritarianism considers that redistribution should benefit the least well-off in society. Accordingly, a just society is arranged to improve the situation of those in most need. Prioritarianism builds on John Rawls’ ‘difference principle’, which claims that an unequal distribution of goods, services and resources is just if the situation of the worst off is improved (Rawls Citation2009). In contrast to sufficientarianism and egalitarianism, it is not weighed whether people are living below or above a certain minimum standard, and there is no intention to close a gap of inequality. Accordingly government should support the ‘left behind’, typically with investments in regional minorities or rural poverty.

Method and data

In recent years, studies in territorial development and spatial planning predominantly focused on improving regional governance procedures, performance and effectiveness. In terms of governance theory (see Schmidt Citation2013), I argue that the scope in contemporary regional studies is mainly limited to the throughput (procedures) and output (performance) of policies, without critically examining the input (politics). Therefore it is necessary to take a step back and review regional development plans from a governmentality perspective that accentuates rationalities of government in creating (un)just geographies (Huxley Citation2007; Soja Citation2010).

In 2009 Bacchi (Citation2009) introduced the ‘What’s the Problem Represented to be?’ (WPR) approach in social sciences. Bacchi (Citation2012) argued that we are governed not through policy but through its problematizations. WPR is an analytical tool that is used to uncover the role of government rationale by studying problematizations in social policy and the implications for those governed (Bacchi and Goodwin Citation2016), with paying close attention to the discursive practices. It is about making politics visible (Bacchi Citation2012).

The WPR approach rejects the conventional idea that government reacts to predetermined or ‘existing’ problems, and proposes that government actively creates policy ‘problems’ (Bacchi Citation2009). Government here is understood through a Foucauldian lens: a critical mode of thinking that focuses on government rationalities, referred to as governmentality (Foucault Citation1991). Despite Foucault’s own critical stance towards geography, emphasizing that space is constituted as an object of government (Foucault Citation2007), several geographers viewed him as a groundbreaking spatial thinker and have reassessed Foucault’s work and further developed his insights (Philo Citation1992; Crampton and Elden Citation2007; Frank Citation2009; Soja Citation2010). The emphasis on government rationale, as well as the aim to put in question the underlying normative premises in social justice, makes the WPR approach fit very well to the purpose of this research. To put it simply, if one uncovers the ‘problem’ in policymaking one can uncover government’s rationale on justice in uneven development and territorial inequality. See Appendix 1 for the seven steps in the WPR framework aimed at identifying and critically scrutinizing problematizations. These steps have been followed to find the problem representation and underlying principle(s) of distributive justice.

The collected textual data consist of a total of 453 policy documents and newspaper articles, see Appendix 2. The 206 policy documents were retrieved from official government websites. The newspaper articles consist of Dutch local, regional and national newspapers. A total of 247 articles are retrieved from LexisNexis, using three search phrases due to different types of spelling: ‘regio deals’, ‘regiodeals’ and ‘regio-deals’. All the data were collected over the period June 2017 till September 2021. Using the software of Atlas.ti, the data were coded.

The data were approached by the standards of a directive content analysis (see Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005), which uses a deductive category application. Codes were assigned to three initial coding categories: WPR (what’s the problem represented to be?), the four principles distributive justice, and the issues named in the RDs. A total of 56 codes were applied to 1337 quotations, see Appendix 3. In doing so, I also considered who claimed what (opposition parties, ministries, coalition partners and cabinet), see Appendix 4. Since there is a lot of emphasis on rhetoric in this study, the quotations were difficult to quantify. It was not possible to simply count the number of arguments for the four orientations towards redistribution and weigh them against each other. The quotations have therefore been thoroughly qualitatively studied in order to be interpreted in the context of the research questions.

The RD fund for regional development is calculated across municipalities by taking each allocated budget and divide it with the amount of participating municipalities. Subsequently, the distribution is accounted for population size and the contribution by central government weighed per inhabitant of a municipality. Both the municipal division and population size are taken from 2020. The RD with three Caribbean Islands Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, Saba (former colonies and nowadays considerably autonomous areas within the Kingdom of the Netherlands) is excluded from the geographic analysis since this paper focuses on within-country dynamics.

Regional development policies in the Netherlands

The Dutch consensual governance system (Van der Meer et al. Citation2019) is characterized by central supervision and local operationalization (Groenleer and Hendriks Citation2018). Likewise, the Dutch spatial planning system is consensus-oriented and structured on the guidelines of decentralization and deliberation (Hajer and Zonneveld Citation2000). The first regional development policies designed by Dutch national government were introduced after World War II. From the 1950s to the early 1980s, an egalitarian oriented Dutch welfare state introduced strong top-down planning policies to tackle uneven regional development. Problematizing the overdeveloped ‘urban west’ of the Netherlands and the underdeveloped ‘rural rest’, economic policies aimed to rebalance regional inequality through industrial development (Molema Citation2012). A so-called spread policy (spreidingsbeleid) was introduced to disperse employment and population across the Netherlands, with investment grants for manufacturing industries and with relocation of state institutions.

In the 1980s, after the economic recession induced by the oil crisis, a neoliberal wave entered European politics that stimulated measures of austerity, deregulation, privatization and market competition (see Peck Citation2010). In spatial planning, this led to ‘urban neoliberalization’ (Van Loon, Oosterlynck, and Aalbers Citation2019), in which neoliberal regimes with a pro-growth agenda pursued national economic success through reinforcing a few successful cities (Florida Citation1996; Brenner and Theodore Citation2002; Glaeser Citation2011; Crouch and Le Galès Citation2012). Likewise, urban neoliberalization in the Netherlands led national government to move away from investing in underdeveloped regions, towards facilitating clusters in urban cores combined with stimulating top sectors (Van der Wouden Citation2016, Citation2021). Provincial levels were held responsible for their ‘own’ regional economies. Central government principally invested in place-based projects to maximize national economy (see Davoudi, Galland, and Stead Citation2020; Ros Citation2009), and supplied new infrastructure for the national champions in reaching a global-city status (Fainstein Citation2001; Van Loon, Oosterlynck, and Aalbers Citation2019).

In the last decade, public sector reforms triggered a rise in regional governance arrangements in the Netherlands (Groenleer and Hendriks Citation2018; Klok et al. Citation2018). Since 2010 the Netherlands was governed by coalitions with the liberals as largest party, all headed by prime minister Mark Rutte. These cabinets are generally considered a continuation of a neoliberal government path from the 80s (see Aalbers Citation2013; Van Loon, Oosterlynck, and Aalbers Citation2019; Ward, Van Loon, and Wijburg Citation2019; Oudenampsen Citation2021), pursuing more civic self-reliance. A combination of increased decentralization (see Klok et al. Citation2018), multi-level partnerships (see Van den Berg Citation2011) and public–private partnerships in networked governance (see Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2014), tied the laces of Dutch governance even more closely to the regional scale. Yet, simultaneous austerity measures such as structural cutbacks in municipal budgets caused an imbalance between tasks, organization, authorities and funding, pressuring many municipalities into financial hardship (see Van der Meulen Citation2021; ROB Citation2021b).

Until the third government of Rutte (2017-2021), spatial development policies proceeded with an entrenched focus on the city as engines of economic growth – with the exception of a new policy for areas with population decline implemented in 2011. In 2015 a network comprising the 40 largest cities, together with national government and local stakeholders formulated targets on urban issues such as climate adaptation, inner-city construction and urban accessibility. These were the so-called City Deals. Cabinet Rutte-III announced an increased focus on issues and governance at the regional scale (Schaap et al. Citation2017).

Findings

The findings of the paper are brought back to four themes that help to answer the research questions. First, the problem representation in the RD policy is laid out. Then, the paper shows how the policy is discursively justified and designed. The last section of the findings presents which regions did (not) benefit from the actual distribution of the budget for regional development.

‘Fixing’ inadequate regional governance for more prosperity

At the installation of the third cabinet of Rutte in 2017, a new fund for regional development was announced. As part of the coalition’s ambition to ‘invest for all’, Cabinet Rutte-III announced that €900 million (later topped up to €950 million) was budgeted for regional ‘bottlenecks’ (knelpunten). This budget for 2018–2022 came to be known as the Region Envelope (Regio Envelop). The way of distributing the budget across regions was put in the hands of The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (ANFQ). Even though it is difficult to pinpoint one specific problem definition in the RD policy (see also Bacchi and Goodwin Citation2016, 20), I found that central government mostly problematized a lack of prosperity in the country caused by inadequate regional governance. See Appendix 5 for a network overview of the codes with the number of quotations.

In February 2018 the policy design for regional development was first introduced as ‘the Region Deals’, and was laid out as a new bottom-up approach to boost and accelerate prosperity. The choice for making the Ministry of ANFQ responsible for the RD policy, suggested that the Region Envelope was engaging with rural development. Yet, the Ministry of ANFQ announced to target all sorts of regional ‘challenges’ (opgaven), from urban to rural. In the official letters to parliament and general meetings with members of parliament between 2018 and 2021, the country was repeatedly presented by the Ministry of ANFQ as a set of distinct regions with each region having its own unique opportunities and challenges. It was argued that regional disparities in the Netherlands needed to be fully utilized to bring more progress to the whole country, and that these growth potentials were best recognized by the decentral governments at the ground: strength comes from the region.

To fully utilize regional disparities government claimed that there was a need for new and efficient governance at the regional level, implying that the regional governance was inadequate. Much emphasis was laid on the aim to stimulate national growth through regional resilience. Examples of this problem representation are shown below in the quotations from the first paragraphs in the first official letters to parliament laying out the RD policy.

If central government, regional governments and companies, knowledge institutions and social organisations in the regions work together, we can do more for society and government policy becomes more effective. Because in regions, societal challenges come together more often and opportunities arise. If we strengthen regions, we can strengthen society. And a country with a strong society can mean more in the world. (The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality Citation2018a, 1)

Throughout the Netherlands we are committed to a strong society and we are working on our economy and future, for all our regions. The government would like to tackle challenges jointly in partnership with the regions. Together with regional governments, the business community, knowledge institutions and social organisations, we strengthen the regions and thus society. (The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality Citation2018b, 1)

Central government’s desire to ‘strengthen’ the country as a whole through enforcing the region, is in line with the utilitarian principle of maximizing collective wellbeing for the largest public (see Warnock Citation2003). From this perspective locked, untapped potentials at a regional scale were proposed to hinder the country from progress and more wellbeing. Knowledge and engagement of regional stakeholders at the ground willing to improve their region were seen as potential sources for collective growth.

The policy problem of the country not being strong enough was proposed here as coming from inadequate regional resilience to changes in society, which is to be ‘fixed’ with a new way of regional governance. This corresponds with the idea that good governance is a prerequisite for (economic) growth and development (Nanda Citation2006). ‘Good’ regional governance was perceived as networked entities that stretch beyond single political-administrative borders. Challenge-led partnerships in the form of regional ‘coalitions of the willing’ were considered more effective to adapt to the current changes and challenges in society. Partnerships between decentral governments, private organizations and knowledge institutes in the region were idealized, so-called triple-helix collaborations. The RDs were practiced in what can be called an institutional void, a political setting in which ‘there are no generally accepted rules and norms according to which policy making and politics is to be conducted’ (Hajer Citation2003, 175). ‘Region’ was purposefully left borderless and unspecified to prompt new and unfixed regional coalitions at an intermunicipal level. This is no official political-administrative level in the Netherlands (Klok et al. Citation2018), and it has been criticized for stepping out of boundaries of local democracy (see ROB Citation2021a).

A financial booster for new regional coalitions was meant to stimulate regional resilience. Under the name ‘broad prosperity’ (brede welvaart), central government implemented a specific concept of sustainable wellbeing for designing and assessing the RDs. Broad prosperity is understood well beyond economic performance. It covers a broad range of topics in regard to quality of life, such as subjective wellbeing, material wealth, health, work and leisure, housing, solidarity, safety and consequences of climate change (Horlings and Smits Citation2019). Similar to the Sustainable Development Goals (OECD CFE Citation2020), the concept of broad prosperity is grounded in the idea by Stiglitz and colleagues and the CES recommendations to use alternative measurements to GDP to indicate economic performance, social progress and sustainable development (Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi Citation2009; UNECE et al. Citation2014). With that, wellbeing within the Netherlands was considered principally place-based, more precisely regionalized. Corresponding with ideas of endogenous growth, civic self-reliance and subsidiarity, national government aimed to utilize quality of life by branching it into regions. Central government made decentralized authorities responsible for regional prosperity by discursive appeals (see also Davoudi, Galland, and Stead Citation2020). For instance, a slogan ‘strength from the region’ (kracht van de regio) used for an official RD website and Twitter account emphasized the unique and distinctive regional characteristics and the initiatives coming from a region.

Claiming to enforce prosperity for all, including those who are left behind

This section describes how the policy for regional development was discursively justified. Claims about a just distribution of the RDs were mostly found in the communication between the ministry and parliament, such as the official letters of the ministry to parliament and the official general meetings with members of parliament. General meetings were held with a commission consisting of fixed members of parliament from both coalition and opposition parties who had the task to monitor the government activities of the Ministry of ANFQ, including the RDs.

The redistributive policy intervention of the RDs were implemented to improve broad prosperity for all, with a dual focus. On the one hand it aimed to strengthen by seizing opportunities for growth, on the other hand it aimed to strengthen weaknesses by helping a hand where needed. For instance, in official letter to parliament, the Ministry of ANFQ wrote (2018a, 2–3):

The government is particularly interested in initiatives that exceed the effect or capacity of the region. For example, by giving impulses to regions where there are opportunities or by offering a helping hand to regions that cannot cope with their problems without help. The core of the approach is its bottom-up character: the cabinet seeks to connect with the challenges and opportunities associated with the DNA of the region.

When asked by the social-democratic opposition party to clarify why the government does not only prioritize specific regions that are left behind in order to decrease regional inequality, for instance with the retraction of public services, the Minister of ANFQ (The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality Citation2020, 16) emphasized a dual focus:

Of course we look at where you can give an extra impulse. […] but you also look very specifically at the need in such an area. That is also the philosophy behind the deals. So yes, we pay attention to places where things are less easy, but it is not an exclusive consideration to drop it [a government investment] there.

Besides an utilitarian orientation pursuing to boost national growth, one can also see a prioritarian tendency in central government’s discourse around the RDs. Typically, one sentence from the 2017 coalition agreement was quoted in several official letters to parliament to justify the selected RDs in the tender procedure.

Our goal is to make a strong country even better for all, especially for those who now have the feeling that the government is no longer here for them.

The last part of the sentence is crucial here, which problematized people who feel unheard in society. It was actually at the start of the third government Rutte, the cabinet coalition articulated to also improve the situation of groups at the bottom. The reason for that was Rutte-III considered their potential discontent, rooted among others in their unwelcoming stance towards newcomers, a threat to the stability of the country (VVD et al. Citation2017, 1). At a later stage of the RD policy, from September 2019 onwards, this quote was frequently referred to in the letters of the ministry.

In the RD policy there is an important distinction between injustice between regions and injustice within regions. The former is a matter for national government, while the latter is considered a matter for decentral government. What is (un)just intraregional wellbeing is thus left open to regional coalitions and their problem representation, making a wide range of problematizations of regional injustices in the RDs (see also Evenhuis, Weterings, and Thissen Citation2020). Regional issues varied from population decline to sustainable agriculture, and from employment to undermining criminality, see Appendix 3. With that, citizens have become more dependent of subnational governmentality, and how it perceives justice in relation to regional development. Unfortunately, the collected proposals were not extensive and detailed enough to rigorously grasp the underlying principles of justice per region in this paper. These documents were rather short and brought forward a variety of issues in the respective region since the policy demands to target multiple issues in broad prosperity.

The evidence presented above shows that in the discursive justification of the RD policy there was a mixture of two principles of redistributive justice: utilitarian and prioritarian. The RDs were initiated to boost regional wellbeing across the country, and the Netherlands as a whole was to benefit from it. Yet, central government also claimed that the groups that feel unheard should also benefit from the regional investments.

Selecting through coalition negotiations and tendering

In this section, I highlight the design, the policy tools for the distribution of the Region Envelope fund of €950, – million. Simply put, it comprised three rounds. Six projects preselected in the coalition agreement (round 1) were followed by two rounds of tendering in 2018 and 2020.

The preselection of six place-bound projects was the result of coalition negotiations, which in the consensus-seeking Netherlands has a tradition of consulting representatives of civil society and decentral governments among others, who may lobby for their ‘problems’. There was not much explanation provided for why these six projects were prioritized. When asked for clarification by MPs, the Minister of ANFQ argued that she simply followed the coalition agreement, and that in some cases old promises by political parties were fulfilled (2020). The preselected projects varied greatly, supporting: the economically thriving region Brainport Eindhoven, nuclear waste management in Petten, a space technology campus in Noordwijk, urban inequality in Rotterdam, financial compensation for the province of Zeeland, and the quality of life in Caribbean Netherlands.

The tendering design was open to all regions, any local or regional coalition could apply. Decentral governments were called to establish new partnerships with regional stakeholders and propose new plans to stimulate development trajectories in their region. Since regional coalitions were left unbound to borders, significant deals for tackling urban issues in large cities were also allowed – not exactly what one expects from a region deal. The proposals deemed most viable and effective were selected. The budget was monitored geographically by classifying the Netherlands into four districts (North, East, South, West). From a somewhat egalitarian idea, the aim was to balance the investments between these four areas, but no formal rules were accounted for geographic distribution. Based on the collected data, this study cannot say to which extent proposals from lagging regions were (dis)favoured behind the closed curtains of the ministry.

In the tendering procedures, proposals were required to meet several preconditions for an assessment framework (The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality Citation2018b). In general, coalitions were asked to:

formulate a new challenge that covers more than one issue and that matches regional goals of central government

co-fund 50% of the deal

form a new coalition of the willing with explicit goals (efficiency)

form public-private partnerships (triple-helix)

aim for long-term effects

not compensate budget shortages

In cooperation with ‘deal makers’, public servants of the Ministry of ANFQ, selected applicants were ‘matched’ to policymakers of ministries, so-called thematic experts, and work out a covenant.

To guide ‘good’ regional governance from the bottom-up and to fixate opportunities and challenges of broad prosperity at a regional scale, a new regional monitor for broad prosperity was provided by central government (CBS Citation2020). Rather than using this monitor to determine which regions are in most need, or which regional inequalities in broad prosperity are most urgent, central government shared the monitor with subnational governments in order for them to determine what challenges and opportunities are important in their region.

The choice for a tender procedure shows that central government advocated competiveness between regions as the right instrument to trigger new regional coalitions. A neoliberal pro-market ideology here viewed competition as a fair tool that serves to empower regional resilience through endogenous development processes (Jessop Citation2018). More importantly, it was a technique by central government to reshape regional governance through examination, which can be considered a form of hierarchic control that is qualifying and classifying desired norms (Foucault Citation2010, 256–269). After all, it was central government who selected which regions received investments and who imposed deal makers to help formulate the region deals. The design of the RD policy (preselection, tender, assessment framework, deal makers) did not indicate a preference for specific disadvantaged regions, for tackling regional inequality, or for guaranteeing specific minimum standards. Moreover, the preconditioned 50% co-funding, by reason of substantiating commitment, made it more difficult to apply for regions with smaller budgets or in financial hardship.

Big winners and small winners

Which regions actually financially benefited from the regional development fund? In total 32 regional coalitions were funded. Six were preselected in the coalition agreement, and 26 RDs were selected through tendering. See Appendix 6A and 6B for an overview of the funding per round. The bar chart in Appendix 6B shows that some places received much higher investments than others. The Brainport region around Eindhoven and the city of Rotterdam were both attributed €130 million, Petten received €117 million. These lucky few can be considered the big winners of the redistribution. In the competitive calls, each region could apply for funding between €5 to €40 million, with a total budget of about €200 million per round. This was far less than what the big winners received. More than half of the total budget of the Region Envelope was spent to the six preselected projects.

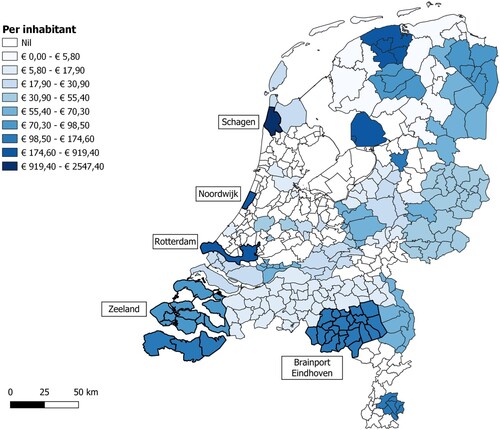

shows the Region Envelope (2018-2022) distributed across municipalities per inhabitant, using the Jenks natural breaks classification method. The distribution of the RD fund is calculated by taking each region deal divided by participating municipalities weighed for population size. The map in demonstrates that the municipalities of Schagen (Petten) and Noordwijk received relatively large shares of funding per capita. Unlike the other RDs, the preselected funding for nuclear waste management in Petten (€117 million) and a space technology campus in Noordwijk (€40 million) was not required to come up with 50% co-funding.

Figure 1. Region Envelope (2018–2022) distributed across municipalities. Source: own work. Note: Municipalities part of preselected projects are outlined and labelled.

To see how the regional development fund was distributed across the urban-rural continuum combined with the centre-periphery continuum, I made a bar chart in Appendix 6C. Even though the big winners were not located in the periphery, the sum of smaller investments in more peripheral areas also led to a relatively high share of investments there. For instance in North-Eastern Fryslân, the Noordoostpolder, Zeeuws-Vlaanderen and Parkstad Limburg.

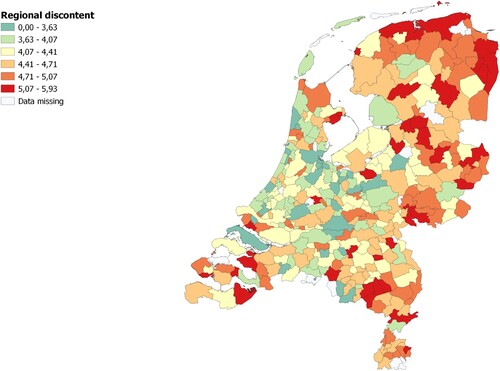

Finally, to examine whether the RDs reached the regions in which people feel neglected, left behind, or unseen by their government, I looked at the distribution of the budget geographically. More specifically, I visually considered how the Region Envelope is distributed across municipalities in relation to feelings of regional discontent. Therefore I make use of unique geocoded survey data from the SCoRE project, conducted online in May 2017 and completed by 8133 respondents. shows the average score of regional discontent per municipality based on three survey-items on a Likert scale. A higher score represents more regional discontent. Subsequently, the map used Jenks natural breaks classification method to highlight the relative disparities between areas. Regions with a greater extent of regional resentment are generally located in the rural periphery of the Netherlands (De Lange, van der Brug, and Harteveld Citation2022). The plot in Appendix 7 excluding two outliers (Schagen and Noordwijk), shows that on average municipalities with a higher share of regional discontent received more funding per inhabitant.

Conclusion and discussion

This article critically examined new policy for regional development from a spatial justice perspective. 453 policy documents and newspaper articles were collected for a qualitative case study of a novel policy approach in the Netherlands, the so-called Region Deals. With that, this study aimed to uncover what the policy problem was represented to be, which normative principle of justice was underlying the distribution of the regional development fund, and which regions benefitted from the fund. In the official policy practice the rationalities of distributive justice were inconsistently articulated by national government in the RD policy. Based on evidence from policy aims, tools and allocation, this article concludes that the RD policy was grounded in a mixture of utilitarian and prioritarian principles of justice.

The RDs were implemented by problematizing a lack of progress in the country that was proposed to be fixed with adequate regional governance. The Dutch RD policy broke with decades of conventional policymaking for urban economic development (see also Spaans Citation2006; Van Loon, Oosterlynck, and Aalbers Citation2019; Ward, Van Loon, and Wijburg Citation2019), by looking at sustainable development challenges at the regional scale. Urban and rural disparities, actors at the ground, and local knowledge, were viewed as untapped endogenous sources to be utilized in order to create more wellbeing across the country. New and unfixed regional coalitions with public-private partnerships between decentral governments and local organizations were stimulated by means of a preconditioned one-off financial booster.

Based on the discursive evidence presented in this paper, I conclude that the RD policy problem was represented from a mixture of theoretical orientations to distributive justice: both utilitarian and prioritarian. An efficiency-driven central government claimed on the one hand to strive for maximum regional wellbeing across the whole country, and on the other to also specifically invest in people who are left behind in the progress of the country and feel unheard. Any improvement within a region was considered as ‘right’.

Even though the third government of Rutte discursively problematized people who are left behind, this paper also concludes that the RD policy tools were not designed to specifically invest in places that are left behind. Using pro-market and deregulation techniques to stimulate regional competiveness in an institutional void (see Hajer Citation2003), at an intermunicipal level all regions could apply for investments in tender procedures. Rather than rebalancing unevenness between the regions, ensuring a sufficient standard of wellbeing, or prioritizing left-behind regions, central government’s assessment framework for selecting the RDs focused to boost prosperity within all regions. Given the structural imbalance between tasks, authority and funding that pushes municipalities into financial hardship (see Van der Meulen Citation2021; ROB Citation2021b), one can question whether there was a level playing field with the co-funding regulations. The opening up to the region with the Region Deals can be considered as a shift from ‘urban neoliberalism’ that stimulated successful cities to a new form of regional neoliberalism that enforces sustainable growth within regions (c.f. Brenner and Theodore Citation2002; Aalbers Citation2013; Ward, Van Loon, and Wijburg Citation2019).

While feelings that one’s area is being overlooked by government are a substantial source of discontent in peripheral Netherlands (De Lange, van der Brug, and Harteveld Citation2022; Huijsmans Citation2022), the RD policy investments included these so-called places that don’t matter (see Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018) but not specifically prioritized them. Whether the RDs actually had an effect on regional discontent requires further research. On the one hand, one can expect that the regional development fund might have tempered regional discontent in the funded peripheral areas. With many investments, although smaller, given to rural and peripheral areas, the RDs also recognized regions with more regional discontent. On the other hand, one can expect an opposite effect for possibly sending a misgiving message to people in peripheral places by giving the largest investments closer to the centre and by including deals for urban development only. Moreover, big winners of the region deals were also preselected in the coalition agreement without participating in a form of competition like other regions had to, which could seem unfair to the small winners and those who received no funding. Future research would have to indicate what a ‘right’ distribution of government investments across regions actually would be according to those who feel their region is ignored by national government.

This study also has its limits. For instance, knowing that policymakers have an important role in government shifts (Oudenampsen and Mellink Citation2021), this study does not uncover to what extent the administrative elites in charge of selecting the RDs determined what a spatially just redistribution was, and whether they had an underlying preference for supporting left-behind regions or not. Nor did I look into the practice of political lobbying by local politicians and local stakeholders who urged for investments in ‘their’ region. Finally, from a comparative view, it would be valuable to examine other new regional development plans that are set out by national governments, such as UK’s Shared Prosperity Fund of £2.6 billion, and compare whether they can be sorted into different principles of justice.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (746.6 KB)Data availability

Data of SCoRE is available at: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-znu-4wt8.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aalbers, M. 2013. “Debate on Neoliberalism in and After the Neoliberal Crisis: Debates and Developments.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37(3): 1053–1057. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12061.

- Bacchi, C. 2009. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education.

- Bacchi, C. 2012. “Why Study Problematizations? Making Politics Visible.” Open Journal of Political Science 02(01): 1–8. doi:10.4236/ojps.2012.21001.

- Bacchi, C., and S. Goodwin. 2016. Poststructural Policy Analysis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-52546-8.

- Brenner, N., and N. Theodore. 2002. “Cities and the Geographies of “Actually Existing Neoliberalism.”.” Antipode 34: 349–379. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00246.

- Buitelaar, E. 2020. Maximaal, gelijk, voldoende, vrij: Vier perspectieven op rechtvaardigheid. Haarlem: Trancityxvaliz.

- Buitelaar, E., A. Weterings, and R. Ponds. 2017. Cities, Economic Inequality and Justice: Reflections and Alternative Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Carolan, M. 2019. “The Rural Problem: Justice in the Countryside.” Rural Sociology 0: 1–35. doi:10.1111/ruso.12278.

- CBS. 2020. “Regionale Monitor Brede Welvaart 2020.” Den Haag: CBS Accessed March 22, 2021. https://dashboards.cbs.nl/rmbw/regionalemonitorbredewelvaart/.

- Cramer, K. 2016. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Crampton, J. W., and S. Elden, eds. 2007. Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Crouch, C., and P. Le Galès. 2012. “Cities as National Champions?” Journal of European Public Policy 19(3): 405–419. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.640795.

- Davoudi, S., D. Galland, and D. Stead. 2020. “Reinventing Planning and Planners: Ideological Decontestations and Rhetorical Appeals.” Planning Theory 19(1): 17–37. doi:10.1177/1473095219869386.

- De Lange, S., W. van der Brug, and E. Harteveld. 2022. “Regional Resentment in the Netherlands: A Rural or Peripheral Phenomenon?” Regional Studies, 1–13. doi:10.1080/00343404.2022.2084527.

- Den Hoed, W. 2021. “The Wellbeing Agenda: A New Stimulus for Regional Policy?” European Policies Resolution Centre. https://eprc-strath.eu/public/dam/jcr:17ff085b-1c50-4ccc-980a-9dbddfd848aa/Sustainable%20Regional%20Policy%20Blog_June21.pdf.

- Dijkstra, L., H. Poelman, and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2020. “The Geography of EU Discontent.” Regional Studies 54(6): 737–753. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603.

- Essletzbichler, J., F. Disslbacher, and M. Moser. 2018. “The Victims of Neoliberal Globalisation and the Rise of the Populist Vote: A Comparative Analysis of Three Recent Electoral Decisions.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1): 73–94. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx025.

- EU. 2020. “Territorial Agenda 2030: A Future for All Places.” Germany: Informal Meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development and/or Territorial Cohesion. https://www.territorialagenda.eu/files/agenda_theme/agenda_data/Territorial%20Agenda% 20documents/TerritorialAgenda2030_201201.pdf.

- Evenhuis, E., A. Weterings, and M. Thissen. 2020. “Bevorderen van brede welvaart in de regio: keuzes voor beleid.” 61.

- Fainstein, S. 2001. “Inequality in Global City-Regions.” DisP - The Planning Review 37(144): 20–25. doi:10.1080/02513625.2001.10556764.

- Fainstein, S. 2015. “Spatial Justice and Planning.” In Readings in Planning Theory, edited by S. S. Fainstein and J. DeFilippis, 258–272. Chichester: John Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781119084679.ch13.

- Florida, R. 1996. “Regional Creative Destruction: Production Organization, Globalization, and the Economic Transformation of the Midwest.” Economic Geography 72(3): 314. doi:10.2307/144403.

- Florida, R. 2021. “Discontent and Its Geographies.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. 14(3): 619–624. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsab014.

- Foucault, M. 1991. “Governmentality.” In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, edited by G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller, 87–104. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- Foucault, M. 2007. “Questions on Geography.” In Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography, edited by J. W. Crampton and S. Elden, 173–182. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Foucault, M. 2010. Discipline, Toezicht en Straf: De geboorte van de gevangenis. Groningen: Historische Uitgeverij.

- Frank, M. 2009. “Imaginative Geography as a Travelling Concept: Foucault, Said and the Spatial Turn.” European Journal of English Studies 13(1): 61–77. doi:10.1080/13825570802708188.

- Frankfurt, H. 1987. “Equality as a Moral Ideal.” Ethics 98(1): 21–43. doi:10.1086/292913

- Fraser, N. 2009. Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Friedmann, H., and J. Wayne. 1977. “Dependency Theory: A Critique.” Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 2(4): 399. doi:10.2307/3340297.

- Glaeser, E. 2011. Triumph of the City: How our Greatest Invention Makes us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier. New York: Penguin.

- Gordon, I. 2018. “In What Sense Left Behind by Globalisation? Looking for a Less Reductionist Geography of the Populist Surge in Europe.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1): 95–113. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx028.

- Groenleer, M., and F. Hendriks. 2018. “Subnational Mobilization and the Reconfiguration of Central-Local Relations in the Shadow of Europe: The Case of the Dutch Decentralized Unitary State.” Regional & Federal Studies, 1–23. doi:10.1080/13597566.2018.1502179.

- Hajer, M. 2003. “Policy Without Polity? Policy Analysis and the Institutional Void.” Policy Sciences 36(2): 175–195. doi:10.1023/A:1024834510939

- Hajer, M., and W. Zonneveld. 2000. “Spatial Planning in the Network Society-Rethinking the Principles of Planning in the Netherlands.” European Planning Studies 8(3): 337–355. doi:10.1080/713666411.

- Harteveld, E., W. Van Der Brug, S. De Lange, and T. Van Der Meer. 2021. “Multiple Roots of the Populist Radical Right: Support for the Dutch PVV in Cities and the Countryside.” European Journal of Political Research, doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12452.

- Harvey, D. 2009. Social Justice and the City. Revised ed.. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Horlings, E., and J. Smits. 2019. Conceptueel kader voor een regionale monitor brede welvaart. Den Haag: CBS.

- Hsieh, H., and S. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15(9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Huijsmans, T. 2022. “Place Resentment in ‘the Places That Don’t Matter’: Explaining the Geographic Divide in Populist and Anti-Immigration Attitudes.” Acta Politica, doi:10.1057/s41269-022-00244-9.

- Huxley, M. 2007. “Geographies of Governmentality.” In Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography, edited by J. W. Crampton and S. Elden, 187–204. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Jessop, B. 2018. “Neoliberalization, Uneven Development, and Brexit: Further Reflections on the Organic Crisis of the British State and Society.” European Planning Studies 26(9): 1728–1746. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1501469.

- Jones, R., S. Moisio, M. Weckroth, M. Woods, J. Luukkonen, F. Meyer, et al. 2019. “Re-conceptualising Territorial Cohesion Through the Prism of Spatial Justice: Critical Perspectives on Academic and Policy Discourses.” In Regional and Local Development in Times of Polarisation, edited by T. Lang and F. Görmar, 97–119. Singapore: Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-1190-1_5.

- Klijn, A., and F. Koppenjan. 2014. “Complexity in Governance Network Theory.” Complexity, Governance & Networks 1(1): 61–70. doi:10.7564/14-CGN8.

- Klok, P., B. Denters, M. Boogers, and M. Sanders. 2018. “Intermunicipal Cooperation in the Netherlands: The Costs and the Effectiveness of Polycentric Regional Governance.” Public Administration Review 78(4): 527–536. doi:10.1111/puar.12931.

- Lefebvre, H. 1996. “The Right to the City.” In Writings on Cities, edited by E. Kofman and E. Lebas, 63–184. London: Blackwell.

- Madanipour, A., M. Shucksmith, and E. Brooks. 2021. “The Concept of Spatial Justice and the European Union’s Territorial Cohesion.” European Planning Studies, 1–18. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1928040.

- Martin, R., B. Gardiner, A. Pike, P. Sunley, and P. Tyler. 2021. Levelling Up Left Behind Places: The Scale and Nature of the Economic and Policy Challenge. Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Levelling-Up-Left-Behind-Places-The-Scale-and-Nature-of-the-Economic-and/Martin-Gardiner-Pike-Sunley-Tyler/p/book/9781032244303.

- Maxwell, R. 2020. “Geographic Divides and Cosmopolitanism: Evidence from Switzerland.” Comparative Political Studies 53(13): 2061–2090. doi:10.1177/0010414020912289.

- McKay, L., W. Jennings, and G. Stoker. 2021. “Political Trust in the ‘Places That Don’t Matter’.” Frontiers in Political Science 3: 642236. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.642236.

- Mitsch, F., N. Lee, and E. Ralph Morrow. 2021. “Faith No More? The Divergence of Political Trust Between Urban and Rural Europe.” Political Geography 89: 102426. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102426.

- Molema, M. 2012. “The Urban West and the Rural Rest: Framing in Dutch Regional Planning in the 1950s.” Landscape Research 37(4): 437–450. doi:10.1080/01426397.2012.687444.

- Moroni, S. 2020. “The Just City. Three Background Issues: Institutional Justice and Spatial Justice, Social Justice and Distributive Justice, Concept of Justice and Conceptions of Justice.” Planning Theory 19(3): 251–267. doi:10.1177/1473095219877670.

- Nanda, V. 2006. “The ‘Good Governance’ Concept Revisited.” The American Academy of Political and Social Science 603(1): 269–283. doi:10.1177/0002716205282847.

- Needham, B., E. Buitelaar, and T. Hartmann. 2018. “Law and Justice in Spatial Planning.” In Planning, Law and Economics RTPI Library Series, edited by B. Needham, E. Buitelaar, and T. Hartmann, 125–137. Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315111278-7.

- Nielsen, K. 1979. “Radical Egalitarian Justice: Justice as Equality.” Social Theory and Practice 5(2): 209–226. doi:10.5840/soctheorpract1979523.

- OECD CFE, C. for E., SMEs, Regions and Cities. 2020. “A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals.” OECD. https://www.oecd.org/regional/a-territorial-approach-to-the-sustainable-development-goals-e86fa715-en.htm.

- Oudenampsen, M. 2021. “The Riddle of the Missing Feathers: Rise and Decline of the Dutch Third Way.” European Politics and Society 22(1): 38–52. doi:10.1080/23745118.2020.1739198.

- Oudenampsen, M., and B. Mellink. 2021. “Bureaucrats First: The Leading Role of Policymakers in the Dutch Neoliberal Turn of the 1980s. TSEG – Low Ctries.” The Journal of Economic History 18(1): 19–52. doi:10.18352/tseg.1197.

- Papadopoulos, A. 2019. “Editorial: Spatial Justice in Europe. Territoriality, Mobility and Peripherality.” Euros XXI 37: 5–21. doi:10.7163/Eu21.2019.37.1.

- Peck, J. 2010. Constructions of Neoliberal Reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peter, F. 2007. “Rawls’ Idea of Public Reason and Democratic Legitimacy.” Political Ethics-Revised 3(1): 129–143. doi:10.3366/per.2007.3.1.129

- Petrakos, G., L. Topaloglou, A. Anagnostou, and V. Cupcea. 2021. “Geographies of (in)justice and the (in)Effectiveness of Place-based Policies in Greece.” European Planning Studies, 1–18. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1928050.

- Philo, C. 1992. “Foucault’s Geography.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 10(2): 137–161. doi:10.1068/d100137

- Pirie, G. 1983. “On Spatial Justice.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 15(4): 465–473. doi:10.1068/a150465.

- Rawls, J. 2009. A Theory of Justice. Revised ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ROB. 2021a. Droomland of Niemandsland? Den Haag: Raad voor het Openbaar Bestuur.

- ROB. 2021b. Rust-Reinheid-Regelmaat: Evenwicht in de bestuurlijk-financiële verhoudingen. The Hague: Raad voor Openbaar Bestuur (Council for Public Administration).

- ROB. 2022. Brede welvaart, grote opgaven!. Den Haag: Raad voor het Openbaar Bestuur.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. “The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to Do About It).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1): 189–209. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx024.

- Ros, A. 2009. “De Historie van het Fonds Economische Structuurversterking.” Tijdschrift voor Openbare Financiën 41: 2–14.

- Schaap, L., M. Groenleer, A. Van den Berg, and C. Broekman. 2017. Coalitieakkoord 2017: vertrouwen in (de toekomst van) de regio? in. Tilburg: Tilburg University. p. 6.

- Schmidt, V. 2013. “Democracy and Legitimacy in the European Union Revisited: Input, Output and ‘Throughput’.” Political Studies 61: 2–22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x.

- Shucksmith, M., E. Brooks, and A. Madanipour. 2021. “LEADER and Spatial Justice.” Rural sociology 61(2): 322–343. doi:10.1111/soru.12334.

- Smith, D. 2000. “Social Justice Revisited.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 32: 1149–1162. doi:10.1068/a3258.

- Soja, E. 2010. Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Spaans, M. 2006. “Recent Changes in the Dutch Planning System: Towards a New Governance Model?” The Town planning review 77(2): 127–146. doi:10.3828/tpr.77.2.2.

- Stiglitz, J., A. Sen, and J. Fitoussi. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

- The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality. 2018a. “Letter of the Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality” (Parliamentary paper 29697, No. 37). in (The Hague). https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-29697-37.html.

- The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality. 2018b. “Letter of the Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality” (Parliamentary paper 29697, No. 48). in (The Hague). https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-29697-48.html.

- The Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality. 2020. “Letter of the Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality” (Parliamentary paper 29697, No. 85). in (The Hague). https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-29697-48.html.

- Tomaney, J., and A. Pike. 2020. “Levelling Up?” Political Research Quarterly 91(1): 43–48. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12834.

- UNECE, Eurostat, and OECD. 2014. “Conference of European Statisticians Recommendations on Measuring Sustainable Development.” New York, Genéve: United Nations.

- Van den Berg, C. 2011. “Transforming for Europe: The Reshaping of National Bureaucracies in a System of Multi-level Governance.”

- Van der Meer, F., C. van den Berg, C. van Dijck, G. Dijkstra, and T. Steen. 2019. “Consensus Democracy and Bureaucracy in the Low Countries.” Politics of the Low Countries 1(1): 27–43. doi:10.5553/PLC/258999292019001001003.

- Van der Meulen, L. 2021. “Gemeenten in nood: Een mensenrechtenperspectief op de toegankelijkheid van maatschappelijke ondersteuning in Nederlandse krimpgemeenten.” Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor de Mensenrechten 46: 151–169.

- Van der Wouden, R. 2016. “The Spatial Transformation of the Netherlands 1988-2015.” Proceedings of the 17th International Planning History Society Conference 17(6): 13–23. Delft, 2016. doi:10.7480/iphs.2016.6.

- Van der Wouden, R. 2021. “In Control of Urban Sprawl? Examining the Effectiveness of National Spatial Planning in the Randstad, 1958–2018.” In The Randstad: A Polycentric Metropolis Regions and Cities, edited by W. Zonneveld and V. Nadin, 281–294. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203383346.

- Van Leeuwen, E., S. Halleck Vega, and V. Hogenboom. 2021. “Does Population Decline Lead to a ‘Populist Voting Mark-up’? A Case Study of the Netherlands.” Regional Science Policy Practice 13(2): 279–301. doi:10.1111/rsp3.12361.

- Van Loon, J., S. Oosterlynck, and M. Aalbers. 2019. “Governing Urban Development in the Low Countries: From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism and Financialization.” European Urban and Regional Studies 26(4): 400–418. doi:10.1177/0969776418798673.

- Van Vulpen, B., and B. Bock. 2020. “Rethinking the Regional Bounds of Justice: A Scoping Review of Spatial Justice in EU Regions.” Romanian Journal of Regional Science 14: 5–34.

- VVD, CDA, D66, and ChristenUnie. 2017. “Vertrouwen in de toekomst (coalition agreement 2017-2021)”. in (The Hague).

- Wacquant, L. 2008. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Wallerstein, I. 1974. The Modern-World System (Vol. 1–3). New York: Academic Press.

- Ward, C., J. Van Loon, and G. Wijburg. 2019. “Neoliberal Europeanisation, Variegated Financialisation: Common but Divergent Economic Trajectories in the Netherlands, United Kingdom and Germany.” Tijdschrift Voor Econmische En Sociale Geografie 110(2): 123–137. doi:10.1111/tesg.12342.

- Warnock, M., ed. 2003. Utilitarianism and on Liberty: Including Mill’s ‘Essay on Bentham’ and Selections from the Writings of Jeremy Bentham and John Austin. Second ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Weck, S., A. Madanipour, and P. Schmitt. 2021. “Place-based Development and Spatial Justice.” European Planning Studies, 1–16. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1928038.

- Woods, M. 2019. “Rural Spatial Justice (pre-print copy).” Gam Grazer Architecture Magazine Graz Architecture Magazine 15: 44–55.

- Wuthnow, R. 2018. The Left Behind: Decline and Rage in Rural America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.