ABSTRACT

Responsible research and innovation (RRI) has recently emerged as a policy framework to align technological innovation with broader social values. It helps regions focus on their strengths and boost their innovation, growth, and prosperity through partnerships between business, public entities, and knowledge institutions. However, the study of RRI dynamics including whether and how attitudes, drivers, and behaviours at the individual, organizational, and network levels affect the impact of RRI, is in its infancy. Based on a survey of societal actors from three regional innovation ecosystems in Norway, Austria, and Spain, we examine the role of RRI in responsible regional planning. Our study advances our knowledge about regional innovation policies by providing evidence of how different stakeholders and policymakers engage in RRI when designing responsible regional planning. We identify the extent to which they incorporate RRI activities into their work practices, the extent to which their organizations and network support their practices and outcomes, and the effects they have observed. Our study also considers the factors that promote or impede RRI activities. The results are particularly relevant for policy makers interested in strengthening regional innovation policies and boosting regional growth via RRI.

Introduction

Responsible research and innovation (RRI) has recently emerged as a policy framework for aligning technological innovation with broader social values and supporting research and innovation on a regional level (European Commission Citation2018a). This framework prompts a broad set of societal actors, including researchers, policy makers, and business organizations, to work together to improve the alignment of their activities, processes, and outcomes with the values, needs, and expectations of society, leading to responsible, smart, sustainable, and inclusive regional growth (Fitjar, Benneworth, and Asheim Citation2019; Foray, McCann, and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015). However, as some authors have pointed out, the term RRI is not currently well defined (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017). In addition, the theory of RRI has yet to be developed in depth in the sense that it lacks clarity about the factors that might make it efficient and effective (Gianni Citation2020; Stahl et al. Citation2014).

Indeed, the implementation and integration of RRI at the regional level faces various challenges. For instance, the RRI dimensions do not fully reflect the responsibilities of the actors involved in a regional planning process (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017). Second, the outcomes of the process are hard to measure due to the lack of context-based indicators (Cozzoni et al. Citation2021; Monsonís-Payá, García-Melón, and Lozano Citation2017). Finally, comprehensive process models to integrate RRI into regional planning are still underdeveloped (Van de Poel et al. Citation2017).

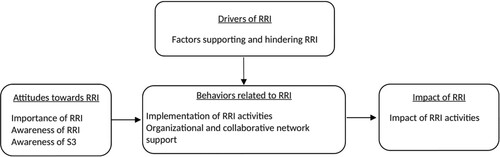

While a single study cannot answer all of these challenges, our study deals with one of these challenges: process modelling. Our goal is to identify empirically the influence of attitudes about RRI on RRI behaviours and practices, and the effects of RRI behaviours and practices on the impact of RRI. Thus, our model considers the factors that regional policymakers noted promote or impede the success of RRI work in various organizations and regions. Our model also reveals the potential links between attitudes towards RRI, and behaviors related to it, was well as its impact.

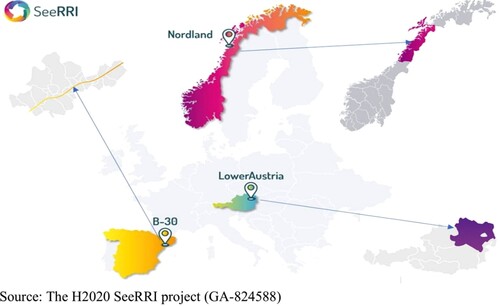

Our study responds to this challenge in several ways. First, building upon the theoretical foundations of the basic concepts of RRI and its supposed contribution to responsible regional planning, we try to address gaps in the literature and enrich it. Next, we use pilots in the three diverse regions—the Nordland region in Norway, the Mechatronic cluster of Lower Austria, and the B30 Area in Spain—to exemplify how RRI initiatives could be used across Europe. We then propose an empirical model for analyzing the preconditions that affect the impact of RRI, meaning the attitudes, drivers, and behaviours related to RRI at the individual, organizational, and network levels. Our pilots were conducted under the auspices of the European project SeeRRI- H2020-SwafS. We use survey data collected from this group of quadruple-helix stakeholders engaged in the process in the three regional innovation ecosystems via workshops and open labs.

This study makes both theoretical and practical contributions. Theoretically, we extend our knowledge about RRI and explain the rationale behind it, the multi-level governance nature of the implementation process, and its potential to improve regional planning processes. We thus contribute to the stream of literature rooted in Ajzen's theory of reasoned action that examines the influence of attitudes on RRI behaviours. Practically, we demonstrate the benefits of RRI for policy makers interested in strengthening regional innovation policies and boosting regional growth via stakeholder engagement in RRI and Smart Specialization (S3) activities. Specifically, we identify the extent to which these stakeholders incorporate RRI activities into their work practices, the extent to which their organizations and networks support their practices and outcomes, and the effects they have observed. Finally, we discuss how and why the RRI framework might change policymaking from top-down to bottom-up by involving a range of societal actors in partnerships between businesses, public entities, and knowledge institutions. This approach should help regions focus on their strengths and boost their regional innovation, growth, and prosperity, without compromising the values, needs, and expectations of society.

The paper is structured as follows. We first present the theoretical background on RRI and its implementation via responsible regional planning in different regional innovation ecosystems. We then discuss the RRI process for responsible regional planning developed within the SeeRRI- H2020-SwafS project and piloted in three regional innovation ecosystems in Austria, Norway, and Spain. Next, we present the research model developed in line with the theory, followed by an account of the methods, procedure, sample, and measures used. Finally, we detail the findings, their implications, and the challenges for future studies.

Theory and background

Origin and theoretical foundations of RRI and S3

Science has an indirect and unforeseeable impact on society. It also has the power to improve humanity's well-being (Gianni Citation2020). There is a growing body of literature and evidence about the advantages of integrating broader perspectives into science, including the possibility of solving problems by adding new information (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). The increasing complexity of issues subject to scientific enquiry requires innovative, experimental, and broader methodologies more focused on bottom-up approaches (Pansera and Owen Citation2018). Research as a bottom-up process to boost innovation has both scientific and democratic relevance, because it has the potential to increase equality and solidarity when knowledge is created via democratic processes (Gianni Citation2020).

The term ‘responsible research’ was first used in 2002 in the 6th Framework Programme (European Commission Citation2002). However, it was not until 2011 that the concept gained wider currency in Europe, being introduced by science policy makers and funding agencies within the European Union's (EU) innovation strategy as a cross-cutting concern of the European Framework Programme Horizon 2020 (H2020). The ambitious goals of RRI were to innovate Europe out of the recent economic crisis (ERAB Citation2012), strengthen public confidence in science, and incentivize cooperation between science and society by highlighting the responsibility of researchers and innovators to society (Fitjar, Benneworth, and Asheim Citation2019; Zwart, Landeweerd, and Van Rooij Citation2014). Since then, the concept has also been discussed and developed in academic publications and European level projects as a broader innovation policy (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017; Klaassen et al. Citation2018; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013; Ulnicane Citation2016) and a means of integrating the social sciences and humanities perspective with that of the hard sciences and engineering (Felt Citation2014).

The most widely cited definition of RRI describes it as a transparent and interactive innovation process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to aligning technological innovation with broader social values (Von Schomberg Citation2011). RRI as an approach to policy originates from the concept of anticipatory governance (Guston and Sarewitz Citation2002) applied to the creation of possible future scenarios and viable alternatives for minimizing future threats in decision-making (Quay Citation2010). The inclusion of various actors and the public is meant to increase the likelihood that R&I may benefit society and prevent any negative consequences caused by government action or inaction (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017).

Alongside the growing interest in RRI, another policy-oriented idea, the Smart Specialization Strategy (S3), has gained currency. This concept is based on partnerships between businesses, public entities, and knowledge institutions aimed at boosting regional innovation, growth, and prosperity by enabling regions to focus on their strengths (European Commission Citation2013). As innovation processes, both RRI and S3 share some similarities, arguing for a broad stakeholder involvement in the development of innovations and innovation policy. Both approaches emphasize the need for R&I to be oriented towards solving major societal challenges across Europe and beyond (Fitjar, Benneworth, and Asheim Citation2019). Nevertheless, despite the apparent similarities, the two concepts differ substantially in their design and implementation, which complement each other. In fact, S3, as opposed to RRI, integrates the local dimension of innovation processes by considering how the regional context and regional capabilities (Balland and Boschma Citation2021) affect the development of innovation and the perception of what is responsible and socially desirable.

S3 has a strong focus on local triple-helix models driven by companies, whereas RRI has a strong focus on civil society's engagement. S3 is a place-based policy that promotes the role of regions. It emphasizes an R&I policy that creates competitive advantages based on regional strengths and potential (Glaser Citation2012). The theoretical framework for the S3 was largely developed by the Knowledge for Growth expert group (Foray, David, and Hall Citation2009) and integrated into the regional policy context by McCann and Ortega-Argilés (Citation2016). The instruments Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization (RIS3) were introduced in 2011 by the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, the EU's regional development policy organization. From 2014–2020, regions have been required to develop S3 strategies as a condition for access to European Structural and Investment Funds, making S3 a key part of the EU's cohesion policy.

Nevertheless, despite their differences, both RRI and S3, taken together or separately, provide an innovation policy framework that assists policymakers in designing and implementing innovative strategies that promote inclusive and sustainable regional economic development (Fitjar, Benneworth, and Asheim Citation2019). However, since our research was carried out under the auspices of a European project, SeeRRI-H2020-SwafS, involved the concept of governance, and envisaged a well-informed deliberative dialogue driven by quadruple-helix societal stakeholders and partners, we concentrated on the impact of RRI as our explanatory variable. However, S3 is still quite relevant. Therefore, attitudes toward S3 is one of our explanatory factors.

The multi-level governance nature of RIS3

Multi-level governance is defined as the participation of many different types of actors, both public and private, in the development and implementation of policies through both formal and informal means. It is a network-like approach to decision making that engages a multiplicity of politically independent but otherwise interdependent actors at different levels of territorial aggregation in processes of negotiation, deliberation, and implementation, without assigning exclusive competence regarding policies or creating a stable hierarchy of political authority to any of these levels (Beeri, Citation2019; Stephenson Citation2013).

There are several complexities involved in implementing RIS3 that are related to its multi-level governance nature. First, different government levels have different perspectives on RIS3 related issues, making collaboration more difficult. Second, RIS3 policies are inclusive, interactive, bottom-up discovery processes in which participants from different environments (policy, business, academia, etc.) discover and provide information about potential new activities, identifying opportunities that emerge through this interaction. In contrast, policymakers assess outcomes and find ways to facilitate the realization of this potential. The learning and negotiation process that entails decision-making at different levels and among different actors is dynamic, which makes it difficult to know beforehand exactly what results will come out of the process. This uncertainty poses problems for policy makers as they are often under pressure to explain clearly what the expected outcomes of policies will be (Cozzoni et al. Citation2021; Paredes-Frigolett Citation2016). Third, RIS3 strategies and their multi-level governance arrangements must be enacted differently in different contexts due to their dependence on the context. They must find solutions specifically tailored for the local conditions, which may be difficult to detect. Finally, a significant factor in RIS3 processes is the mutual recognition of each other by the different governments. This reciprocity depends on the role that various levels of government play. In many countries national governments oversee the design and implementation of S3, while sub-regional governments have not been recognized as relevant actors in the process (Estensoro and Larrea Citation2016).

From theory to practice: integrating RRI and S3 across Europe

Integrating RIS3 into regional planning

Regions and their innovation systems vary greatly in the degree to which knowledge is generated, made available, and shared (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). According to Isaksen and Trippl (Citation2017), regional innovation systems (RISs) consist of two subsystems: 1) industries and firms that can be combined into clusters and networks, and 2) knowledge and support organizations for research, education, and the diffusion of knowledge (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2005). The number and variety of firms, industries, knowledge organizations, and support agencies located in the region constitute an aspect of RISs called the degree of organizational thickness.

Based on this aspect of RISs, Isaksen and Trippl (Citation2016) identified three typologies of RISs. These RIS types often lead to different paths of industrial development (Asheim, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Isaksen et al. Citation2018) and the circulation of local knowledge. Thick, diversified ecosystems are well suited to path creation, meaning the creation of new industries. They circulate more local knowledge due to the availability of a wide variety of knowledge assets. Thick, specialized ecosystems are better suited to path extension, meaning the incremental improvement of existing industries, but can also promote diversification into related industries. Thin ecosystems are best suited to path extension. In terms of local knowledge circulation, both thick specialized and thin RISs have less to offer, forcing actors to source knowledge from outside the region. Understanding these complex configurations of innovation and knowledge sourcing and the ways they vary across industries and regions is very important for scholars and policymakers, particularly when designing new innovation policies and improving their implementation (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2017). This consideration is also crucial for the success of policy implementation for R&I systems at the regional level incorporating the RRI framework.

In an effort to enrich the theory and make it more useful for policy makers, the European Commission highlights six thematic keys of RRI (European Commission Citation2013; Gianni Citation2020; MoRRI Citation2018), together with four process dimensions (Owen and Pansera Citation2019; Owen et al. Citation2013; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). The thematic keys are public engagement, gender equality, science education, open access, ethics, and governance of RRI. Public engagement is about ‘choosing together’, co-creating the future by bringing together the widest possible diversity of actors to tackle major societal challenges. Gender equality is about promoting gender balanced teams and decision-making, and improving the quality and social relevance of outcomes. The aim of science education is to increase the number of researchers by promoting scientific vocations and improving education to provide the public with the knowledge and skills they need to participate in R&I debates. Open access provides free online access to the results of publicly funded research to support the active and passive participation of a broad range of actors in the development of scientific processes. Ethics focuses on research integrity and the ethical acceptability of scientific and technological developments. Finally, governance refers to the responsibility of policymakers to anticipate and assess potential implications and societal expectations about R&I and develop harmonious governance models for RRI that also integrate all of the other dimensions. Success in this regard helps create smart, sustainable, inclusive policies that align better with the values, needs, and expectations of society.

The RRI process dimensions are anticipation, reflexivity, inclusive deliberation, and responsiveness. Their main goal is to function as the basis for robust and legitimate decision-making. Anticipation entails articulating and reflecting on potential outcomes and searching for alternative scenarios and options. Reflexivity involves reflecting on the underlying purposes and motivations to align R&I with social values. Inclusive deliberation refers to the engagement of a diverse range of stakeholders in setting the R&I agenda to boost inter-disciplinarity in the co-creation of knowledge. Responsiveness is about the alignment with changing societal values. An additional dimension, openness (Owen and Pansera Citation2019), implies open and free access to data and results to facilitate informed debate and inclusive deliberation.

The Council of Europe Conferences of Ministers responsible for Spatial/Regional Planning (CEMAT) actively promotes sustainable regional development policies via sustainable regional planning, asserting that, ‘Regional/spatial planning should be democratic, comprehensive, functional and oriented towards the longer term’ (Dejeant-Pons Citation2010, 13).

The implementation of RRI on the territorial level and, as a result, the integration of RRI into regional planning, faces several challenges. First, in accordance with the complexity inherent in multi-level governance (Beeri and Zaidan, Citation2021), the RRI dimensions do not necessarily reflect the responsibility of the actors involved in the regional planning process (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017). Second, the outcomes of the process are hard to measure due to the lack of context-based indicators (Cozzoni et al. Citation2021; Monsonís-Payá, García-Melón, and Lozano Citation2017). Finally, since the dynamics of RRI are still not fully understood, a process model to integrate RRI into regional planning is still lacking (Van de Poel et al. Citation2017). To fill these gaps, in the next sections we will discuss the RRI process for responsible regional planning developed within the SeeRRI H2020-SwafS project and implemented in three regional innovation ecosystems in Austria, Norway, and Spain. Then, we will present data collected from the stakeholders engaged in these processes.

RIS3 and regional planning in lower Austria, Norway, and Spain

The SeeRRI project brings together 12 project partners representing a variety of stakeholders: government, business, academic and civil society organizations, including regional authorities, economic clusters, and a confederation of enterprises in three territories in Europe to build a framework for responsible regional development in those territories as an approach for building self-sustaining R&I ecosystems (Alvarez Pereira Citation2020). The Lower Austrian partners in the SeeRRI project are the Business Agency of Lower Austria, the Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT), and the Business Agency of Lower Austria (Ecoplus). The Nordland partners are the Nordland Research Institute (NRI), the Nordland County Council (NFK), and the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprises (NHO). The B30 partners are the Government of Catalonia (GENCAT) and the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). Additional partners unconnected to the territories are WEDO, Research and Innovation Management, the Innaxis Foundation and Research Institute, the University of Haifa, and the University of Bologna. Other partners include the Official Chamber of Commerce, Industry & Services of Badajoz in Spain (CAMARA), the Haifa Municipality's Strategic Planning & Research Division in Israel, the European Business and Innovation Centre of Burgos in Spain (CEEI), INTERSECTION Centre for Science and Innovation in Belgrade (Serbia), the University of Vaasa and the Regional Council of Ostrobothnia in Finland, the University of Cagliari's Departments of Social Sciences and Institutions & Civil and Environmental Engineering and Architecture in Italy, and the NGO Montenegrin Science Promotion Foundation (PRONA) in Podgorica. The rationale for including a set of quadruple-helix organizations from outside Europe is testing the framework of RRI principles and regional development policies built from the three territories in SeeRRI outside Europe, leveraging the SeeRRI results not only within Europe, but also on a wider stage.

The group of quadruple-helix regional stakeholders from the three innovation ecosystems worked together from November 2019 and September 2021. These three territories were selected because of their active engagement with smart specialization strategy and RRI activities. maps the three SeeRRI territories.

The selection and engagement of the stakeholders follows the regional RRI planning process integrating RRI into smart specialization, RIS3, to impact regional innovation and growth in an inclusive and sustainable way. First, the project partners identified and selected the territorial stakeholders in the three regional ecosystems (Panciroli, Santangelo, and Tondelli Citation2020; Tondelli, Santangelo, and Panciroli Citation2019). The mapping identified the key organizations doing research and innovation and the relevant actors (Mitchell, Agle, and Wood Citation1997) capable of influencing regional innovation policy. Once identified, the stakeholders were invited to take part in a series of foresight workshops and open labs. The workshops engaged the stakeholders in a policy co-creation process leading to the integration of RRI practices and activities into regional development policies.

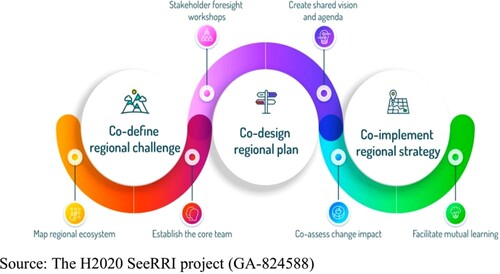

The territorial partners first developed a thematic focus related to the specific challenges of the regional innovation ecosystem. Then, during each workshop the stakeholders created a variety of scenarios anticipating the future implementation of such innovation policies, analyzing the consequences, and developing a shared agenda for implementation that responded to societal needs. During the co-creation process, they were encouraged to learn from each other, sharing information and best practices and brainstorming to move from the scenarios to the concrete innovation strategies in their regions, in line with the RIS3 policy framework. The SeeRRI stakeholders’ workshops applied the four RRI process dimensions as follows: anticipation by engaging in foresight; reflexivity by detailing future scenarios, learning, and sharing; responsiveness by developing strategies that responded to societal needs and met the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2015); and inclusiveness by engaging quadruple-helix stakeholders in the planning process. Openness was not formally included because the process was allowed to be open or closed when needed.Footnote1 The implementation of the SeeRRI approach followed the same approach, objectives, and methods. However, every region was free to formulate its own thematic focus, shared vision, and agenda for the transfer to strategy. This last step involved the evaluation of changes at the organizational level, impacts at the territorial level, the integration of change into an overall strategy (i.e. innovation policy), and the evaluation of trans-regional/trans-national learning. This model can also be implemented in other territories and innovation ecosystems. illustrates the RRI process for responsible regional planning developed within the SeeRRI H2020-SwafS-project.

The regional innovation ecosystem of lower Austria

Lower Austria is the largest province in Austria and is an important business location and focus of economic growth. It has a GDP of around 57 million euro, a population of around 1,600,000 people and is a leading economic performer among the regions of Europe. It hosts 18 academic institutions, 102,000 industries and business companies, and more than 100,000 civil society organizations. It is a vibrant area from many points of view. The clusters have a significant role in the regional economy, involving the quadruple-helix of stakeholders in sustainability, resource efficiency, technology, quality, and safety (Panciroli, Santangelo, and Tondelli Citation2020; Tondelli, Santangelo, and Panciroli Citation2019).

RIS3 is promoted through technopoles and clusters of the Business Agency of Lower Austria. During the foresight workshops, the project partners from Lower Austria identified their thematic focus as being the plastics industry and its contribution to achieving climate goals. Being a technologically advanced region, populated by many different firms and a heterogeneous industrial structure, Lower Austria boasts an organizationally thick and diversified innovation system where the critical mass of knowledge and supporting organizations facilitate innovation and experimentation in a wide range of economic and technological fields.

The regional innovation ecosystem of Nordland

Nordland is a county in the northern region of Norway. It is the second largest area of Norway's 11 regions with a GDP of nearly 11 million euro and a population of around 240,000 inhabitants distributed in 44 municipalities. The economy of Nordland is strongly globalized and it boasts a long tradition of cooperation with regions, knowledge institutions, and businesses throughout Europe. The region includes 10 academic institutions, 29,541 industries and business companies, and 7,613 civil society organizations. It has innovation clusters in several industries including tourism and seafood, and has implemented S3 since 2014 (Tondelli, Santangelo, and Panciroli Citation2019).

Norland's coastal communities face difficult long-term challenges such as depopulation, an aging society, climate change, and environmental pollution. The thematic focus identified during the workshops was on coastal management. The goal was devising a governance approach that found the right balance between creating incentives for industry and protecting the environment. Having strong firms in a limited number of industries and several knowledge and support organizations that are well adapted to the region's narrow industrial base, Nordland boasts an organizationally thick and specialized regional innovation system.

The regional innovation ecosystem of the B30 area

B30 is a strategic location composed of 23 municipalities in the Catalonia region in Spain. It has a GDP of 38 million euro and a population of around 1 million inhabitants. The area is vital and productive, with several quadruple-helix stakeholders: 12 academic institutions, 30,173 industrial and business companies, and many civil society organizations. They are involved in six cluster organizations committed to sustainability, innovation, and efficiency (Panciroli, Santangelo, and Tondelli Citation2020). There are also a considerable number of research and knowledge transfer centres, a fact that provides a competitive advantage and creates considerable added value for the S3 strategy. These characteristics make this axis a unique territory, one that functions as a real research and innovation ecosystem. The area is covered by Catalonia's Smart Specialization Strategy and equipped with R&I infrastructures. The thematic challenge identified was to change the current production and consumption model to one based on the green and circular economy aimed at zero waste generation.

As an advanced metropolitan area with a heterogeneous industrial structure and boasting innovation in a wide range of economic and technological fields, the B30 area represents an organizationally thick and diversified regional innovation system.

Research model and propositions

Our research model is based on a series of propositions. We first propose that attitudes towards RRI may be related to behaviours associated with it, meaning the degree to which individual stakeholders will implement RRI activities and the degree of support provided by the organizations and the network. We also posit that the degree of implementation of RRI activities and the support provided by the organizations and the network relate to the impact of RRI activities.

These propositions are based on the theory of reasoned action and the theory of network effectiveness. The former, also called the theory of planned behaviour, emphasizes that the strength of attitudes towards a behaviour, alongside intensions and subjective norms, serves as an immediate antecedent of behaviours and helps account for the considerable variance in actual behaviours (Ajzen Citation2011; Ajzen and Fishbein Citation1980). It is one of the leading theories explaining behaviour. According to this theory, people's beliefs that a certain behaviour will lead to a favourable or unfavourable outcome helps determine the intensity (e.g. the time and effort) with which they engage in that behaviour (Sheeran Citation2002). The stakeholders’ volitional actions are predicted by their behavioural intentions. These intentions are a function of beliefs or information that the behaviour will lead to a specific outcome (Ajzen and Fishbein Citation1980). One aspect of the theory's framework focuses on organizational behaviours: 1) attitudes toward engaging in a specific behaviour, and 2) subjective norms regarding engaging in the behaviour.

The theory of network effectiveness is defined as the ability of the network to achieve its stated goals, which could not be normally achieved by individual organizational participants (Huang & Provan, 2007; Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). Other definitions are less relevant to our model as they deal with citizens’ views, innovative solutions and the viability of the network itself.

Research on network effectiveness in the field of public administration has focused on the management and leadership skills and behaviours or actions that can enhance such effectiveness (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). For example, Kickert, Klijn and Koppenjan (Citation1997) classified managerial activities in terms of their purpose. They defined network management activities as involving the promotion of ideas designed to affect the perceptions of the network's members, and activities aimed at the interactions between the members. According to McGuire and Silvia (Citation2009), network leadership behaviours help network actors develop effective solutions to a common problem.

Based on Sørensen and Torfing's (Citation2011) framework connecting network leadership behaviours to effectiveness and on the studies presented above, we maintain that a similar relationship is likely to be found in local governance networks.

Thus, based on this theory, we contend that the attitudes of the stakeholders, measured as their awareness of RRI and S3, the importance they attribute to RRI, and the extent to which they feel they are supported by their organizations and collaborative networks, will affect the implementation of RRI activities in their organizations. In addition, we maintain that the degree of implementation of RRI activities increases the impact of RRI activities in terms of their scientific, economic, democratic, and social benefits (European Commission Citation2018b; Gurzawska, Mäkinen, and Brey Citation2017).

Taken as a whole, our research model, presented in , is based on the propositions described earlier in this chapter.

Method

Measures

We collected data on measures capturing attitudes, behaviour, and impacts related to RRI, along with the drivers promoting and impeding RRI. Our approach builds on the MoRRI metrics (MoRRI Citation2018) and considers the six thematic elements of RRI: public engagement, open access, gender equality, ethics, science education and governance of RRI. We also added the rate of recycling municipal waste, which accords with the UN's Sustainable Development Goal 11. The rationale for its inclusion is that environmental sustainability has been included as a key area for stakeholder dialogue in the RRI agenda and the social desirability of research and innovation. Consequently, the SeeRRI workshops involving municipal authorities included a discussion of municipal waste recycling activities in each of the three chosen territories.

To capture insights into the respondents’ attitudes towards RRI (awareness of RRI and views on RRI), first we asked the territorial stakeholders in the R&I ecosystems to quantify their familiarity with the concept of RIS3 on a 7-point Likert scale. We then asked them to quantify their level of agreement with a series of statements related to the thematic elements of RRI.

To gather data on the behaviours related to RRI (degree of implementation of RRI activities), we asked the stakeholders to quantify their degree of implementation of RRI activities. We tested the internal consistency of the Likert-scored items that made up the attitudes and behaviours scales. The Cronbach's α coefficients were 0.73 and 0.51, respectively. The modest alpha coefficient of the behaviour scale probably reflects the fact that the items were chosen to represent the conceptual breadth within each construct in line with the MoRRI indicators, rather than to maximize internal consistency.

We used the results of a multiple-choice questionnaire to assess the impact of the implementation of the RRI activities. We asked the respondents to indicate if, in relation to their organization and/or work practice, they observed or expected any of the impacts listed because of the implementation of RRI activities. The scale included two items for each impact (scientific, economic, democratic, social benefits). We used a similar method to identify the factors that promoted and impeded the implementation of RRI. activities. To gain insights into the organizations’ and networks’ support, we asked the respondents to quantify their level of agreement with a series of statements describing specific factors supporting RRI. The questionnaire is included in the Appendix.

Procedure

To follow up on the propositions that formed the basis of the research model, we used survey data collected within the context of the SeeRRI project. The data were collected between February 2019 and November 2020 via an online questionnaire sent via email to the territorial stakeholders invited to the foresight workshops organized within the scope of the project. One concern with using this approach might be that the stakeholders were involved in the project, so this procedure might suffer from common source bias. While this concern is relevant, systematic knowledge on governance must rely on its stakeholders (Glaser Citation2012). Given the multi-level governance needed for responsible regional planning, the quadruple-helix stakeholders’ views were very relevant for evaluating the impact of RRI. In addition, although the stakeholders were involved, they were not bound by the need to appear successful to external partners. Rather, they were realistic, professional, and at times, skeptical and critical.

Sample

A total of 66 senior stakeholders completed the survey. Of the respondents, 32% were stakeholders from Lower Austria, 33% from Nordland, and the remaining 35% from the B30 area. The response rate was 63% and was very similar across the regions. Of the stakeholders, 26% worked for a university or research organization, 21% for a company, 27% for a public body, 6% for a non-profit organization, 14% were self-employed, and 6% worked for other organizations. With regard to their work experience 45% had 0–5 years of work experience in the current organization, 21% 6–10 years, 20% 11–20 years, and 14% more than 20 years. Most of the stakeholders held a managerial position (65%), 20% were consultants/employees, while 15% had a research position. With regard to education 55% held a master's degree, 21% a doctorate, 15% a bachelor's degree, and 8% had completed high school and had some college education. Finally, 41% of the respondents were female, 54% male, and 5% preferred not to say. Most of the respondents (88%) were involved in activities within the SeeRRI project on average less than 15 h per month.

Statistical procedures

We used the IBM SPSS 28.0 software package to analyze the data. After checking for internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha and variance inflation factors (VIF), which quantify the severity of multicollinearity, we utilized descriptive statistics. Then, we calculated the inter-correlations among the variables using Pearson's correlations. Last, in order to test the mediation effects in a single step we created a mediation model that included our independent, mediating, and dependent variables. We used Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS model #4 and Hayes (Citation2015) for mediation. In addition, PROCESS can generate a bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effects, which has become a widely recommended method for inferences about these effects in mediation analysis (Hayes, Citation2015).

Findings

Stakeholders’ attitudes towards RRI

Awareness of RRI

In general, most of the respondents (68%) stated that they had previously encountered the concept of RRI. However, they were only moderately familiar with the concept of smart specialization (mean 3.58).

Views on RRI

The dimensions related to RRI that the stakeholders indicated were most relevant in their organizations and work practices were sustainability (62%) and public engagement (48%), followed respectively by ethics and science education (both 32%), open access (27%), and gender equality (21%).

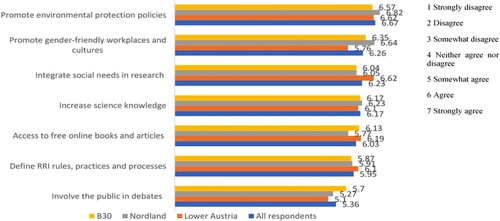

When asked about the importance of RRI actions, most agreed that the promotion of environmental policies was the most important (6.57), followed by the promotion of gender-friendly workplaces and cultures (6.35); and the increase in science knowledge (6.17). illustrates the agreement on the importance of the RRI actions and their mean scores.

Stakeholders’ behaviours related with RRI

Degree of implementation of RRI activities

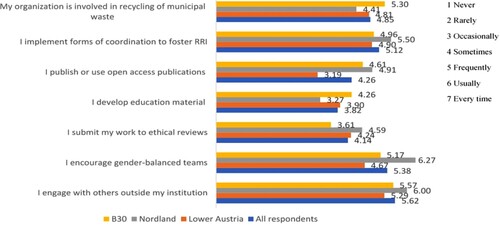

The stakeholders were asked to quantify the frequency with which they implemented activities related to public engagement, gender equality, ethics, science education, open access, governance of RRI, and sustainability in their organization on a scale of 1 (never) to 7 (always). On average they stated that they usually engaged the public (5.62); and frequently promoted gender-balanced teams in their work environment (5.38); put in place forms of coordination designed to foster RRI (5.12) and carried out activities related to the recycling of municipal waste products (4.85). Finally, they only sometimes submitted their work to ethical reviews (4.14), developed education materials (3.82), and published or used open access publications (4.26). presents the degree of implementation of RRI activities and their mean scores.

Factors promoting and impeding RRI

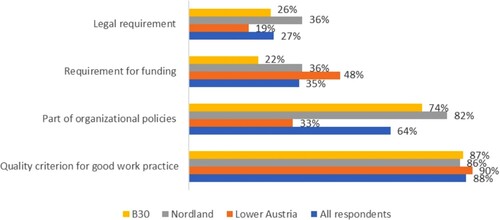

Most of the respondents identified the implementation of RRI activities as a criterion for good work practice (88%), while for 64% implementing such activities is part of their organizational policies. About a third of respondents implement RRI activities as a funding prerequisite (35%) or a legal requirement (27%). illustrates the drivers of the implementation of RRI activities in percentages.

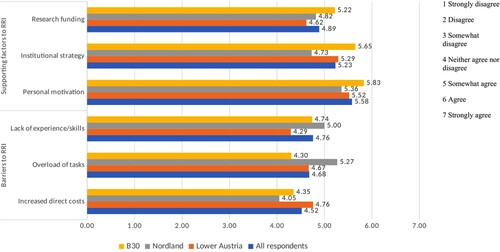

According to the stakeholders, the leading factor supporting RRI was personal motivation (5.58), followed by institutional strategy (5.23), and research funding (4.89). The main barrier was lack of experience or skills (4.76), being overloaded by tasks (4.68), and increased direct costs (4.52). depicts the factors supporting and impeding the implementation of RRI activities by mean scores.

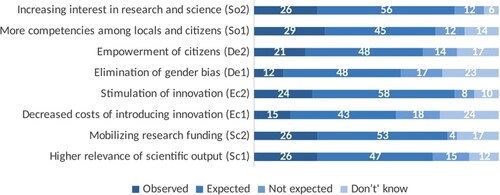

Scientific, economic, democratic, and social impacts of RRI

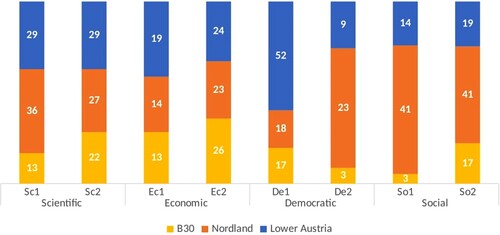

The stakeholders were asked if they observed or expected any scientific (Sc1, Sc2), economic (Ec1, Ec2), democratic (De1, De2), or social (So1, So2) impacts from the implementation of RRI activities. Between 43% and 58% of the respondents expected benefits from the implementation of RRI activities. Most felt it would stimulate innovation (58%), increase interest in research (56%), and mobilize funding (53%). Between 12% and 29% stated that they had already observed benefits, particularly with regard to improved competencies among locals and citizens (29%), increased interest in research, more funding, and more relevant scientific outputs (all at 26%), followed by the stimulation of innovation (24%), and empowerment of citizens (21%). Those skeptical about the impact of RRI felt that reducing the costs of introducing innovation (18%), and eliminating gender bias (17%) were the least likely outcomes. illustrates the impact of RRI by percentages and depicts the observed impact of RRI by territory in percentages.

Testing the research model

In we present the correlations for the research variables. The ranges of the variance inflation factor (VIF), which quantifies the severity of multicollinearity, were very low (.631–1.584). Therefore, we conclude that there is no concern about multicollinearity in this data.

Table 1. Pearson's correlations for the individual-level control and research variables.

In accordance with our expectations, the greater the importance the stakeholders attributed to RRI, the more they implemented RRI activities in their organizations (r = .274, p < .05). In addition, the more they felt supported by their organization and collaborative network, the more likely they were to implement RRI activities (r = .316, p < .05). The degree of implementation of RRI activities was not significantly related to the extent of awareness of RRI and S3. As expected, behaviours, meaning the implementation of RRI activities, were not only related to attitudes, but also were significantly related to the impact of RRI activities. The more stakeholders reported they implemented RRI activities, the more likely they felt that such activities had a strong impact (r = .373, p < .01). These direct relationships support our research model.

Going a step further to test the full model, we used Hayes’ (Citation2015) PROCESS (model #4) to check the indirect, mediating effect of behaviours on the relationship between attitudes and impacts. Our results in confirmed the model. The findings are consistent with the proposal that the more stakeholders agreed about the importance of RRI, the more they reported that their organization and collaborative network supported them and that they implemented RRI activities. Doing so also increased the impact of the RRI activities. The results showed evidence of two significant indirect mediating effects: 1) through support from the organizations and collaborative networks (lower limit confidence interval [LLCI] = .025; upper limit confidence interval [ULCI] = .199) and 2) through the implementation of RRI activities (lower limit confidence interval [LLCI] = .002; upper limit confidence interval [ULCI] = .108). According to the model, the strongest path dynamic would be that views on RRI, meaning awareness of it, does not necessarily have a direct effect on the impact of RRI activities. Rather, these views are related to the behaviours of the stakeholders and their organizations and networks – the implementation of RRI activities and support for doing so, respectively - that increase the impact of RRI activities.

Table 2. Mediation analysis (PROCESS model #4) of indirect effects of organization and collaborative network support and of implementation of RRI activities on the relationship between importance of RRI and the impact of RRI activities.

Discussion

Lessons learned

The RRI process for responsible regional planning implemented within the SeeRRI project integrated the RRI approach to policy into regional planning. Its goal was to fill the gaps in the literature about the implementation of RRI by involving the regional stakeholders. The objective of the process model was to build responsible R&I ecosystems through RRI by integrating RRI into RIS3 to achieve sustainability. This objective involved three steps for each territory: the co-definition of a regional challenge, the co-design of a regional plan via the involvement of the regional stakeholders in a series of foresight workshops, and the co-implementation of a regional strategy.

According to the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen Citation2011; Sheeran Citation2002) that informed our research model, the strength of the stakeholders’ attitudes towards RRI influences the degree of implementation of RRI activities in their organizations, and accounts for variance in this implementation. Following Ajzen (Citation2011) and Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation1980) we proposed that this theory would explain, at least to some extent, the favourable outcomes of RRI activities. Indeed, we found that the greater the importance the stakeholders attributed to RRI, the more they implemented RRI activities in their organizations. Furthermore, the more they felt supported by their organizations and collaborative networks, the more likely they were to implement these activities. Finally, a greater implementation of RRI activities was related to their having a stronger impact.

The mediated effect, as proposed, showed that the more the stakeholders agreed about the importance of RRI, the more they implemented RRI activities and reported about organizational and collaborative network support, which in turn, in their view, increased the impact of the RRI activities. This finding supports our proposition, based on the work of networking and multi-level governance theoreticians (e.g. Provan & Kenis, Citation2008; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011), that in order to achieve RRI's stated goals, there is usually a need for collaboration between the network organizations and their leaders.

The stakeholders’ belief that the implementation of RRI activities, such as engaging with others outside their institution, encouraging gender-balanced teams, submitting their work for ethical reviews, developing educational material, publishing or using open access material, implementing forms of coordination to foster RRI, or being involved in the recycling of municipal waste, will lead to favourable outcomes in terms of economic, social, democratic, and scientific benefits helps determine the time and effort they will devote to engaging in such RRI activities. Thus, to engage stakeholders and stimulate the implementation of RRI activities it is crucial to provide incentives (European Commission Citation2018b). Such incentives can be external, such as burnishing reputations, or internal, primarily involving the engagement of the employees responsible for R&I, whose practices should be aligned with the RRI framework. Gurzawska, Mäkinen, and Brey (Citation2017) argued that RRI implementation has a strong positive effect on employees’ functioning, and, as a result, on companies’ performance as well. Internal stakeholder incentives that emphasize the relationship between employee engagement and companies’ financial performance are related to employees’ well-being and their sense that their organization cares about user needs and society's welfare. Research has established that such feelings motivate employees and affect their actions and behaviour (Grant Citation2007). As a result, they can also influence their attitudes towards the implementation of RRI activities in their organization.

We observed that the key factors playing a role in the implementation of RRI-inspired activities were the perception of RRI as an indicator of good work practices and personal motivation, along with the integration of RRI principles in organizational policies. On the other hand, lack of experience or skills and the perception that the implementation of RRI might cause an overload of tasks or increased direct costs impeded the implementation of RRI activities. The stakeholders had high expectations about the benefits of implementing RRI activities, especially for stimulating innovation, increasing interest in research, and mobilizing funding.

Considering these results, we conclude that more can and should be done to increase awareness of the RRI approach, and highlight its benefits to stakeholders. We note that while the RRI concept is well known among science policy makers and various funding agencies and academics within the EU, many companies are still not familiar with the concept itself and the scientific and governance discourse place around it (Van de Poel et al. Citation2017). This does not mean that they are failing to implement activities in line with RRI. In fact, the implementation of activities that align with the basic concepts of RRI among companies is widespread. However, they use different terms such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), sustainable or open innovation, participatory design, stakeholder dialogues, scenario development, the circular economy, and risk assessments (Martinuzzi et al. Citation2018). The difference between RRI and responsible practices in the business sector lies in the increased focus on social value, responsible science, and the technological development of RRI. These aspects are generally missing from crucial processes in the business sector, such as product development, commercialization, or economic returns (Lubberink et al. Citation2017).

The findings on the territorial level underscore that territorial policymakers face several challenges in trying to collaborate to align RRI with the values, needs, and expectations of society, in line with the RIS3 scope. The consideration of different stakeholders’ views in each territory is very important to implement RRI for responsible regional planning effectively. For example, the plastics industry in Lower Austria helps create an economy that protects the climate, the environment, and resources through its research, development, and products. The RRI approach chosen by the territorial stakeholders supports embedding this sectoral innovation into a broader context. In Nordland, industrial activities on the coast and in the sea can endanger tourism and the traditional way of life. The energy sector in the form of offshore wind farms and oil extraction competes for space with the traditional fishing industry. In addition, oil spills are a looming threat for all involved in food production and harvesting from the sea. Indeed, the traditional ownership structures in the local industries are being replaced by fewer, larger, and more international owners with little sense of belonging to the local community. Actors at different levels of government addressed this policy problem in a collaborative and non-hierarchical way to co-design a regional plan for action. In the B30 area, local actors from different organizations were able to help develop a shared agenda with the goal of zero waste generation.

Therefore, the approach to the implementation of RRI for responsible regional planning applied in the SeeRRI project influenced the policy processes of the organizations involved. For example, it helped the regional governments and industries understand where they stood in terms of RRI. It also served to align the regional stakeholders’ visions and determine how to have more sustainable practices in the future, share good practices, and carry out more research on responsible strategies. Moreover, it showed the feasibility of applying the SeeRRI process to other regions and policy areas.

How can we leverage the SeeRRI approach to influence territorial stakeholders’ attitudes and behaviours towards RRI?

Innovation creates value for individuals, organizations, and societies. Its ultimate goal is about creating a smart future, where technologies and knowledge advance globally and people are more educated. Leaders can motivate and engage people in contributing to the co-creation of a smart future. Governments promote the public's participation in co-creating safe countries in which accountability, transparency, the rule of law, and social justice are universally applied (Lee and Trimi Citation2018).

Governance through the formation of networks composed of public and private actors might help solve wicked problems and promote democratic participation in public policymaking (Sørensen and Torfing Citation2011). The findings of our mediated model point out that shared responsibilities that provide support at the organizational and collaborative network levels are key to the increased impact of RRI activities. We demonstrated that greater awareness of the importance of RRI or the extensive use of RRI activities on their own are insufficient. They are less fruitful than a path that combines these elements with organizational and collaborative network support. Thus, we believe that, above and beyond the adaptation of RRI strategies to a specific area and network, a productive RRI decision-making dynamic in a multi-level governance context should combine bottom-up with mezzo-level practices that create a supportive environment for stakeholders.

More awareness of RRI concepts and the integration of RRI concepts with the right incentives (Gurzawska, Mäkinen, and Brey Citation2017) could have a positive effect on territorial stakeholders’ attitudes towards RRI, as well as the degree of implementation of RRI activities in different organizations, in both the private and public sectors. In fact, in the public sector, multi-actor collaboration has been described as facilitating the ‘co-creation of new and promising ideas and forging joint ownership of these ideas so that they may be implemented in practice and produce outcomes that are deemed valuable and desirable by the key stakeholders’ (Sørensen and Torfing Citation2011, 851).

The RRI process presented here is a bottom-up approach to policymaking. It has the potential to change policymaking from top-down to bottom-up, involve various societal actors, and incentivize partnerships between businesses, public entities, and knowledge institutions. The goal is to enable regions to focus on their strengths and to boost regional innovation, growth, and prosperity without neglecting the values, needs, and expectations of society. In fact, organizational policies on socially responsible research and innovation practices cannot be implemented in a top-down manner, for example, through standardized legal requirements.. However, for organizations to fully align with the concept of RRI, they need to relate it to their own missions, cultures, and worldviews. As a participatory and sustainable process, regional planning should seek to integrate the influences coming from various European territories such as individual and institutional decision-makers, market pressures, features of the administrative systems, and various socio-economic and environmental conditions (Dejeant-Pons Citation2010). Besides the organizational implications of RRI and RIS3, the success of innovation policies such as S3 depends on several interrelated factors including the level of entrepreneurship in the region, the embeddedness of the region in interregional knowledge networks, the size of the R&D market and the amount of human capital (Varga et al. Citation2018).

The territories observed here were more inclined to innovate and had a high degree of organizational thickness due to the large number and variety of firms, industries, knowledge organizations, and support agencies located in them. However, they differed in their established networks of research and innovation actors, which affected the process of translating the SeeRRI approach to integrate RRI into regional planning. As illustrates, the same approach, objectives, and methods were followed in each territory. Nevertheless, every region formulated its own thematic focus, shared vision, and agenda for addressing its major challenges.

In a broad sense, the dynamics that our findings revealed provide a certain balm, although not a complete one, for the challenges inherent in the integration of RRI into regional planning that we discussed above. We pointed to the blurred responsibilities of stakeholders in multi-level governance (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017) and the lack of an understandable process model that integrates RRI into regional planning (Van de Poel et al. Citation2017). We found that in the case of integrating RRI into regional planning, shared responsibility is not only about indicating the strict lines of the division of power and authority between stakeholders. Rather, it is also about wisely blurring the lines and having common, shared responsibilities. These shared responsibilities were reflected in our process model as organizational and collaborative network support that mediated the relationship between awareness about RRI and the impact of RRI activities.

Implications for policymakers

The implications of our findings for policymakers lie in the construction of multi-level governance for the implementation of research and innovation strategies for smart specialization and in the challenge of engaging local actors in an RRI process for responsible regional planning. Governance networks are the proper response to the need for mobilizing the knowledge, resources, and energies of responsible and empowered citizens and stakeholders (Sørensen & Torfing, 2009) and promoting innovation and knowledge sharing.

To implement multi-level governance effectively for S3, it is necessary to confront the complexity of doing so by implementing ad-hoc methodological approaches to solve specific territorial challenges. Doing so requires involving the relevant stakeholders who can influence policy in a process of learning and negotiation. The participants cooperate to co-define the regional challenge, co-design a regional plan to address the challenges, and finally co-implement a regional strategy tailored to addressing the specific policy problem (Cozzoni et al. Citation2021; Paredes-Frigolett Citation2016).

The process of defining RIS3 involves developing policies that yield the expected results. It requires a strong network of trained actors such as local partners from quadruple-helix organizations who can promote the involvement of local stakeholders in responsible regional planning processes in a more visible and coordinated way.

To address the context specificity of the various policy problems, it is crucial to develop and share the knowledge of the various actors involved in the multi-level governance of RIS3 and responsible regional planning strategies. We can accomplish this goal by involving knowledge institutions such as universities or research organizations in the RRI process for responsible regional planning to help territorial stakeholders develop the most appropriate methodologies to deal with the complexity of the specific territory. Mapping the regional innovation ecosystems and assessing the changes and effects of implementing RRI strategies are steps in this direction.

Finally, to build reciprocity in the responsible regional planning and multi-level governance of RIS3, it is crucial to define clear roles and create trust among the various actors at the outset of the S3 discovery process. In doing so, we can promote mutual learning through dialogue and the support of each other's strategies. The design and implementation of RRI strategies for responsible regional planning and RIS3 will have greater impact on the innovation ecosystem when there is mutual recognition of the other stakeholders participating in the process including all those with the power to influence it.

Our study responds to this challenge in several ways. First, we try to address the gaps in the literature about responsible regional planning and enrich it. Second, we present an empirical model for identifying and analyzing the factors that affect the impact of RRI, meaning the attitudes, drivers, and behaviours related to RRI at the individual, organizational, and network levels. We hope that this combination of theoretical and practical contributions will help promote the use of RRI in regional planning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The industrial sensitivity of the deliberations by one group required a degree of confidentiality that precluded total openness.

References

- Ajzen, I. 2011. “The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections.” Psychology & Health 26 (9): 1113–1127. doi:10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 1980. Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior: Attitudes, Intentions, and Perceived Behavioral Control. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Alvarez Pereira, C. 2020. Thesaurus and Conceptual Framework of Self-sustaining R&I Ecosystems. SeeRRI Consortium (D4.1), Publication date: 16 June 2020. Available online: https://seerri.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/SeeRRI_D4.1.pdf. Accessed on January 2021

- Asheim, B., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. Advanced Introduction to Regional Innovation Systems. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Balland, P., and R. Boschma. 2021. “Complementary Interregional Linkages and Smart Specialisation: An Empirical Study on European Regions.” Regional Studies, 1–12. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1861240

- Beeri, I. (2019). Governance Relations in Small Nations: Competition vs. Cooperation and the Triple Role of Big Cities. Lex Localis-Journal of Local Self-Government 17(2).

- Beeri, I., and Zaidan, A. (2021). Merging, disaggregating and clustering local authorities: do structural reforms affect perceptions about local governance and democracy?. Territory, Politics, Governance, 1–26.

- Burget, M., E. Bardone, and M. Pedaste. 2017. “Definitions and Conceptual Dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Literature Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9782-1

- Cozzoni, E., C. Passavanti, C. Ponsiglione, S. Primario, and P. Rippa. 2021. “Interorganizational Collaboration in Innovation Networks: An Agent Based Model for Responsible Research and Innovation in Additive Manufacturing.” Sustainability 13 (13): 7460. doi:10.3390/su13137460

- Dejeant-Pons, M. 2010. Council of Europe Conference of Ministers Responsible for Spatial/Regional Planning (CEMAT).: 1970-2010. Basic texts (Vol. 3). Council of Europe. Available online https://rm.coe.int/16804895e. Accessed in January 2021

- ERAB. 2012. The new renaissance: Will it happen? Innovating Europe out of the crisis. Third and final report of the European research area board. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online http://aei.pitt.edu/46046/1/3rd-erab-final-report_en.pdf. Accessed in January 2021

- Estensoro, M., and M. Larrea. 2016. “Overcoming Policy Making Problems in Smart Specialisation Strategies: Engaging sub-Regional Governments.” European Planning Studies 24 (7): 1319–1335. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1174670

- European Commission. 2002. The 6 Framework Programme in Brief. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2013. National/Regional Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3) Cohesion Policy 2014-2020. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission. Available online https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/informat/2014/smart_specialisation_en.pdf. Accessed on January 2021

- European Commission. 2018a. Horizon 2020 Work Program 2018-2020, Science with and for Society. Available online http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2018-2020/main/h2020-wp1820-swfs_en.pdf. Accessed on June 2019

- European Commission. 2018b. Monitoring the Evolution and Benefits of Responsible Research and Innovation. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/s/oI9k. Accessed in January 2021

- Felt, U. 2014. “Within, Across and Beyond: Reconsidering the Role of Social Sciences and Humanities in Europe.” Science as Culture 23 (3): 384–396. doi:10.1080/09505431.2014.926146

- Fitjar, R., P. Benneworth, and B. Asheim. 2019. “Towards Regional Responsible Research and Innovation? Integrating RRI and RIS3 in European Innovation Policy.” Science and Public Policy 46 (5): 772–783. doi:10.1093/scipol/scz029

- Foray, D., P. David, and B. Hall. 2009. Smart Specialisation – The concept. Knowledge Economists Policy Brief No. 9 June. European Commission Directorate-General for Research.

- Foray, D., P. McCann, and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2015. “Smart Specialization and European Regional Development Policy.” Oxford Handbook of Local Competitiveness, 458–480.

- Gianni, R. 2020. “Scientific and Democratic Relevance of RRI.” In Assessment of Responsible Innovation: Methods and Practices, edited by E. Yaghmaei, and I. V. D. Poel. London: Routledge.

- Glaser, J. 2012. ‘How Does Governance Change Research Content? On the Possibility of a Sociological Middle-Range Theory Linking Science Policy Studies to the Sociology of Scientific Knowledge’, The Technical University Technology Studies Working Paper series, TUTS-WP-1-2012, Berlin: Technical University of Berlin <https://www.ts.tu-berlin.de/fileadmin/fg226/TUTS/TUTS-WP-1-2012.pdf> accessed Sep. 2022

- Grant, A. 2007. “Relational job Design and the Motivation to Make a Prosocial Difference.” Academy of Management Review 32 (2): 393–417. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.24351328

- Gurzawska, A., M. Mäkinen, and P. Brey. 2017. “Implementation of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) Practices in Industry: Providing the Right Incentives.” Sustainability 9 (10): 1759. doi:10.3390/su9101759

- Guston, D., and D. Sarewitz. 2002. “Real-time Technology Assessment.” Technology in Society 24 (1-2): 93–109. doi:10.1016/S0160-791X(01)00047-1

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS (version 2.13). Computer software]. Retrieved from: www.processmacro.org.

- Isaksen, A., S. Jakobsen, R. Njøs, and R. Normann. 2018. “Regional Industrial Restructuring Resulting from Individual and System Agency.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32 (1): 48–65. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Kickert, W. J., Klijn, E. H., and Koppenjan, J. F. M. (Eds.). (1997). Managing complex networks: Strategies for the public sector. Sage.

- Isaksen, A., and M. Trippl. 2016. “Path Development in Different Regional Innovation Systems: A Conceptual Analysis.” In Innovation Drivers and Regional Innovation Strategies, edited by M. D. Parrilli, R. D. Fitjar, and A. Rodriguez-Pose, 66–84. London: Routledge.

- Isaksen, A., and M. Trippl. 2017. “Innovation in Space: The Mosaic of Regional Innovation Patterns.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (1): 122–140. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grw035

- Klaassen, P., M. Rijnen, S. Vermeulen, and F. Kupper. 2018. “Technocracy Versus Experimental Learning in RRI.” Responsible Research and Innovation: From Concepts to Practices, 77–98. doi:10.4324/9781315457291-5

- Lee, S., and S. Trimi. 2018. “Innovation for Creating a Smart Future.” Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 3 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2016.11.001

- Lubberink, R., V. Blok, J. Van Ophem, and O. Omta. 2017. “Lessons for Responsible Innovation in the Business Context: A Systematic Literature Review of Responsible, Social and Sustainable Innovation Practices.” Sustainability 9 (5): 721. doi:10.3390/su9050721

- Martinuzzi, A., V. Blok, A. Brem, B. Stahl, and N. Schönherr. 2018. “Responsible Research and Innovation in Industry—Challenges, Insights and Perspectives.” Sustainability 10: 702. doi:10.3390/su10030702

- McCann, P., and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2016. “The Early Experience of Smart Specialization Implementation in EU Cohesion Policy.” European Planning Studies 24. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1166177

- McGuire, M., and Silvia, C. (2009). Does leadership in networks matter? Examining the effect of leadership behaviors on managers' perceptions of network effectiveness. Public Performance & Management Review 33 (1): 34-62.

- Mitchell, R., B. Agle, and D. Wood. 1997. “Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of who and What Really Counts.” Academy of Management Review 22 (4): 853–886. doi:10.2307/259247

- Monsonís-Payá, I., M. García-Melón, and J. Lozano. 2017. “Indicators for Responsible Research and Innovation: A Methodological Proposal for Context-Based Weighting.” Sustainability 9 (12): 2168. doi:10.3390/su9122168

- MoRRI. 2018. The Evolution of Responsible Research and Innovation in Europe: The MoRRI Indicators Report (D4.3). MoRRI consortium. Publication date: 01 February 2018. Available online. https://morri.netlify.com/reports/2018-02-21-the-evolution-of-responsible-research-and-innovation-in-europe-the-morri-indicators-report-d4-3. Accessed in September 2019

- Owen, R., and M. Pansera. 2019. “Responsible Innovation and Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Handbook on Science and Public Policy, edited by D. Simon, S. Kuhlmann, J. Stamm, and W. Canzler, 35–48. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Owen, R., J. Stilgoe, P. Macnaghten, M. Gorman, E. Fisher, and D. Guston. 2013. “A Framework for Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, 27–50. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Panciroli, A., A. Santangelo, and S. Tondelli. 2020. “Mapping RRI Dimensions and Sustainability Into Regional Development Policies and Urban Planning Instruments.” Sustainability 12 (14): 5675. doi:10.3390/su12145675

- Pansera, M., and R. Owen. 2018. Innovation and Development: The Politics at the Bottom of the Pyramid. London: ISTE/ Wiley.

- Paredes-Frigolett, H. 2016. “Modeling the Effect of Responsible Research and Innovation in Quadruple Helix Innovation Systems.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 110: 126–133. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.001

- Provan, K. G., and Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of public administration research and theory 18 (2): 229–252.

- Quay, R. 2010. “Anticipatory Governance: A Tool for Climate Change Adaptation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (4): 496–511. doi:10.1080/01944363.2010.508428

- Sheeran, P. 2002. “Intention—Behavior Relations: A Conceptual and Empirical Review.” European Review of Social Psychology 12 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1080/14792772143000003

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2011. “Enhancing Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector.” Administration & Society 43 (8): 842–868. doi:10.1177/0095399711418768

- Stahl, B., N. McBride, K. Wakunuma, and C. Flick. 2014. “The Empathic Care Robot: A Prototype of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 84: 74–85. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2013.08.001

- Stephenson, P. 2013. “Twenty Years of Multi-Level Governance: ‘where Does it Come from? What is it? Where is it Going?’.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (6): 817–837. doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.781818

- Stilgoe, J., R. Owen, and P. Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2005. “One Size Fits All? Towards a Differentiated Regional Innovation Policy Approach.” Research Policy 34 (8): 1203–1219. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

- Tondelli, S., A. Santangelo, and A. Panciroli. 2019. RRI within Regional Development Policies: The Case of Catalonia, Lower Austria and Nordland, SeeRRI Consortium (D2.3), Publication date: 31 October 2019. Available online: https://seerri.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2020/07/SeeRRI_D2.3.pdf. Accessed in January 2021

- Ulnicane, I. 2016. “Research and Innovation as Sources of Renewed Growth? EU Policy Responses to the Crisis.” Journal of European Integration 38 (3): 327–341. doi:10.1080/07036337.2016.1140155

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Division for Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Van de Poel, I., L. Asveld, S. Flipse, P. Klaassen, V. Scholten, and E. Yaghmaei. 2017. “Company Strategies for Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI): A Conceptual Model.” Sustainability 9: 2045. doi:10.3390/su9112045

- Varga, A., T. Sebestyén, N. Szabó, and L. Szerb. 2018. “Estimating the Economic Impacts of Knowledge Network and Entrepreneurship Development in Smart Specialization Policy.” Regional Studies 54 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1527026

- Von Schomberg, R. 2011. Towards Responsible Research and Innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields. Available online http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/mep-rapport-2011_en.pdf. Accessed in January 2021

- Zwart, H., L. Landeweerd, and A. Van Rooij. 2014. “Adapt or Perish? Assessing the Recent Shift in the European Research Funding Arena from ‘ELSA’to ‘RRI’.” Life Sciences, Society and Policy 10 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1186/s40504-014-0011-x