ABSTRACT

The appraisal stage is crucial to the later success of transport infrastructure megaprojects. Stakeholders must be engaged early to protect their interests. This article analyses power dynamics and rationalized knowledge in long-term timelines and trajectories using critical discourse analysis. It examines a case where powerful stakeholders directly influenced decision-making. The Norwegian Public Road Authority planners helped local and regional community stakeholders collaborate over 13 years. This collaboration successfully advocated for a fixed-link concept alternative in the national transport plan. The findings suggest considering changes to the planning framework and local execution.

1. Introduction

The later phases of large infrastructure projects are based heavily on the groundwork laid down during the appraisal stage when different concepts are launched and initially investigated. Projects within such planning regimes are promoted at various levels by different stakeholders. In Norway, the overall goal for those advocating a specific concept is to reach the official investment queue of the National Transport Plan, which is crucial for the final parliamentary decision-to-build and budget allocation. Stakeholder empowerment in the early phases is key to ensuring their interests from a longer perspective. Entrance to the early initiatives means that the stakeholders’ preferred project ideas or concepts can be included in later concept study phases, and hence be among the alternatives considered for shortlisting towards the final submission to parliament. Different parts of the transport planning sector will inherently affect other policy areas in society, and path dependency appears along with institutional and geographical scales and levels (Pemberton Citation2000). Hence, there is a need to address the links between early initiatives and policymaking along paths and timelines on the one hand and executive decision-making about transport investments on the other. These links may involve the concepts of power and knowledge.

Transport planning lies in the intersection between multiple stakeholders and/or actors,Footnote1 arenas, networks, and discourses, and within and between different institutions. Knowledge production between stakeholder engagement and plan-making is ideally a deliberative procedure, but it also creates tension at the formal stages of the planning process. When the role of power and power relations in planning is not fully considered, there is a danger of overlooking the absence of conflict as an element worth discussing. See for example Lukes (Citation2005, 7) take on Bachrach and Baratz (Citation1970) second face of power – the non-decision power dimension. Consensus emerges in the absence of conflict and could be seen as the deliberative traits that most planning processes seek to live up to today. Consensus-based planning can be one-sided and uncritical, and questions about who benefits from specific outcomes might not be asked (Innes and Booher Citation2016). Such planning may restrict planners from speaking with ‘fearless speech,’ as described by Foucault, which may keep planners from using a critical ethos that opposes political influence (Grange Citation2017; Grange and Winkler Citation2023). Ideally, planning could comprise a collaboration between experts such as engineers and economists, and other stakeholders such as politicians and community members (Vigar Citation2017).

The importance of a thorough approach to understanding the use of power is well covered in the classic planning literature, addressing the actions of different types of stakeholders (Flyvbjerg Citation1993, Citation1998; Forester Citation1989), as well as more contemporary contributions (see e.g. Gunder, Madanipour, and Watson Citation2018; Grange and Winkler Citation2023).

The same applies to classical theories on path dependence in public policies in general (North Citation1990; Pierson Citation2000, Citation2004). A few studies address path dependency in transport planning (Dooms, Verbeke, and Haezendonck Citation2013; Low and Astle Citation2009; Upham, Kivimaa, and Virkamäki Citation2013; Wright and Dia Citation2019), as well as knowledge development (Næss et al. Citation2013; Pettersson Citation2013; Vigar Citation2017). However, the present article fills a research gap by linking the concepts of power, knowledge, and path dependency in the early phases of a transport planning process. The impact of these theoretical concepts on early decision-making in infrastructure investments is poorly covered in the existing body of literature.

To address this gap, this study uses a case from Norway: the appraisal process for the E39 Romsdalsfjord fixed link project, which is investigated through the following empirical research questions:

RQ1:How did stakeholder participation in active and operational planning influence the E39 project toward a certain planning outcome?

RQ2: How do power, knowledge, and path dependency affect planning and decision-making in transport infrastructure projects?

Besides the empirical conclusions on stakeholder participation, the article also contributes to the theoretical discussions within the field, with its focus on the early phases of transport infrastructure planning and how concepts of power, knowledge, and path dependency play an interlinked role in this phase. The paper also consider how planning is performed on different governmental levels, with standardized planning processes.

The paper is structured as follow: The next section of this article, the theoretical concepts of power, knowledge, and path dependence are presented, as well as an analytical framework. This is followed by a methodological section that describes the CDA research design and the material obtained. Using the CDA tradition, the overall case context is then presented in a combined finding and discussion section. The concluding section summarizes the main findings and conclusions.

2. Theoretical approaches and analytical framework

2.1. Power through stakeholder engagement

Forester (Citation1989) places power and the exercise of power in a planning context, warns against disregarding how force is used during planning, and advocates for a greater focus on forces that planners should not ignore. This is thoroughly demonstrated in an in-depth study of an urban development project in Aalborg, Denmark, by Bent Flyvbjerg (Flyvbjerg). By addressing stakeholders’ and actors’ use of power (and knowledge), he uses planning as a metaphor and explanation for modern politics, administration, planning, and modernism. According to Flyvbjerg, the development planning proposal for the Aalborg project initially appeared both rational and democratic, but the project evolved and changed. Flyvbjerg (Citation1998) shows that powerful stakeholders rationalized certain preferred outcomes. This scenario may be familiar to planners, legislators, and other stakeholders in general, but the Aalborg project's lessons can help explain power and reasoning in planning.

The interaction of people, actors, and systems creates a conventional conception of power as the ability to affect others. Such power may transform and become structural over time. Lukes (Citation2005) describes power as ‘faces’: something visible; something unspoken and agenda-based; and something that can turn into something ideological and structural. First, in Dahl’s (Citation1957) view of power, A has power over B to make B do something they would not otherwise. Dahl’s claim is that A can push B away from what B represents. The second level of power, agenda power, addresses what is ‘on the table’. Person A, the powerholder, restricts the public's ability to analyse political and institutional practices by ensuring they only discuss harmless topics, thus limiting Person B's ability to actively take a stand that could harm A. If A succeeds, B will not be able to raise issues that could affect A's objectives, interests, and preferences. A non-decision event occurs, as pointed out by Bachrach and Baratz (Citation1970). Even when agenda power is included in the one-dimensional study of power, this is still about power in an open battle. If conflict is absent, consensus is likely (Lukes Citation2005).

Lukes also adds a third dimension, structural power, which can be interpreted differently and takes many forms. This power dimension is more dispersed and more difficult to access than the other two. Without considering collective dynamics and social arrangements, the authority to set political agendas and exclude problems cannot be properly analysed (Lukes Citation2005).

The first dimension of power consists of two parties directly exercising power. The second dimension is an open and visible form of power that consists of withholding something from the discussion. The third dimension, institutionalized power, is hidden in structures and processes, limiting actors’ ability to exercise power directly (Østerud Citation2002). According to Østerud (Citation2002), tacit power refers to the unacknowledged power inherent in social practices and collective forces. This is in line with Foucault’s view of power as something present in all social interactions, at all times and places (Lynch Citation2014) According to Flyvbjerg (Citation1998), Foucault believed such variations were normal and part of power's inherent flexibility and that reproducing knowledge or perceptions of a topic or unique issue through collective structures (forces) and social systems allows influence and control of desires, needs, and excitement. A can force B to do what B does not want, but A can also influence, shape, or determine B's wants (Lukes Citation2005, 27). This power might be termed the ‘power of enthusiasm’ or the ‘power of influence.’

Some academics distinguish the third dimension from the fourth – the latter describes an empowered actor's discursive authority to construct and reproduce reality, knowledge, and meaning within governing practices (Haugaard Citation2012). Transport planning affects different policy sectors, and governance could be addressed at both institutional and regional scales. Lack of common planning on all levels, may affect overall objectives (Pemberton Citation2000; Russo and Rindone Citation2021)

2.2. Power through knowledge utilization

Flyvbjerg links power with knowledge. In his abovementioned seminal study, (The Aalborg Project), he references Francis Bacon (1561–1626) and his famous ‘knowledge is power’ statement. The commutative principle of mathematics (ab = ba) indicates that if knowledge provides power, then power provides knowledge, in the sense that the powerholder implicitly possesses the authority to define knowledge in, or about, a field or area. Transport planning stakeholders may have technical, financial, or early planning expertise. Sector politicians and private business players such as consultants and project advocates also know their fields well. One may anticipate that dealing with uncomfortable knowledge, which planners may or may not consider while performing, is more difficult (Flyvbjerg Citation2013). Some examples include weak input numbers in a cost-benefit analysis, technical concerns with one or more concepts, ethical tensions related to climate change or budget spending, and centre – periphery issues. This is due to stakeholder interests conflicting (Booth and Richardson Citation2001). At the intersection of knowledge and action in planning, ethics matter (Campbell Citation2012; Winkler and Duminy Citation2014).

Tennøy et al. (Citation2016) found that expert knowledge drives planner behaviour, but planners may dismiss it if it contradicts their objectives or ideals. Some planners may self-censor when balancing their expertise and political ambitions. This creates embodied/local, technical/codified, practice-centred, and political ‘knowledge’ that guides policy (Vigar Citation2017). According to Vigar (Citation2017), policies and initiatives based solely on instinct, ideology, and political factors should be avoided.

In a study on planners and (political) transaction costs, Sager (Citation2006) uses critical communicative planning theories to show that planners can avoid disregard of knowledge, for any reason, by focusing on better arguments. For this reason, stakeholder pressure must be avoided, and all parties involved in planning must work towards a common goal. By avoiding manipulative tactics and other deliberate communication perversions, planning should illuminate political transaction costs (Sager Citation2006).

According to Welde et al. (Citation2014), political tactical manoeuvres, cognitively biased forecasting, strategic splits in time, and an inadequate knowledge basis underpin decision-making in Norwegian transport megaprojects.

2.3. Path dependency

Path dependency is associated with most institutions (Arthur Citation1994; Low and Astle Citation2009; Torfing Citation2001), while power is also involved in planning decision-making (Flyvbjerg Citation1998; Forester Citation1989). One question is whether power-fuelled path dependency in transport governance can be corrected (Pierson Citation2000; Williamson Citation1993). Most megaprojects, including transport, are risky due to long planning horizons and complex interfaces. In multi-actor processes, public and private interests may not have deep domain experience (Flyvbjerg Citation2017). Learning processes and timelines take time. In the early stages, path-dependent processes can cause overfocus on certain projects. The process is ‘caught’ around a project, causing a ‘lock-in’ that makes it hard to analyse other options and avoid commitment escalation. While most lock-in research has focused on implementation, Cantarelli, Oglethorpe, and van Wee (Citation2022) examine decision-makers’ initial perceptions of lock-in risk and show that risk attitudes and levels of risk aversion vary. Other scholars have noted the lack of awareness in the early phases, since, due to not having any ‘skin in the game’, planners and forecasters do not have to take responsibility for potential failures as a result of their decision-making.

Transparency builds trust and legitimacy (Weston and Weston Citation2013), and most transport planning processes encourage early dialogue (Tornberg and Odhage Citation2018). This may ensure participation from powerless outsiders (Healey Citation1992). Dooms, Verbeke, and Haezendonck (Citation2013) use path dependence and stakeholder-based analysis to suggest that stakeholder inclusion can drive governance change in strategic planning, while Vigar (Citation2017) suggests that a more communicative, transdisciplinary approach to transport planning will broaden the understanding of actors and their behaviour. The latter argument is also emphasized by Cascetta et al. (Citation2015), that proposes a standardized step-by-step – planning model that take into consideration the dynamics between Stakeholder Engagement, rational decision-making, and quantitative methods.

2.4. Analytical framework

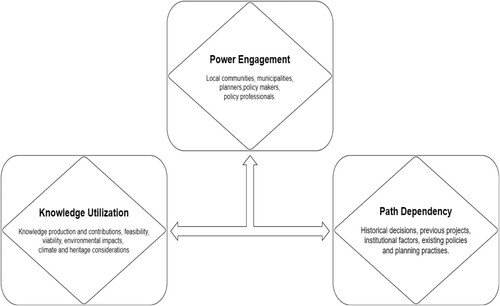

To analyse this paper`s case effectively, this study uses a comprehensive analytical framework that considers the following dimensions: power engagement, knowledge utilization, and path dependency ().

As shown in above, the three theoretical concepts are mutually in relation to each other, and should thus be analysed in context, which this paper will tentatively show should be implemented as natural elements to consider in a planning process. Power engagement represents the various stakeholders involved in the transport planning process, such as local communities, municipalities, planners, public road authorities, and policymakers (see ). This dimension recognizes that there are power dynamics among stakeholders. By examining their ability to influence decision-making through political skills, experiences, and lobbying, one can explore how different stakeholders use their influence to shape the planning process. Influence tactics (e.g. rational persuasion, legitimation, and pressure) and different bases of power (expert power, legitimate power) can be combined (Ninan, Mahalingam, and Clegg Citation2019). External forces in TIPs may thus gain support for their preferred concepts and secure a place in the National Transport Plan, an important step on the route to the final decision to build and the ability to receive funding from parliament.

Knowledge utilization (see ) as a concept describes what happens when actual and objective knowledge evolves into additional domains – e.g. political, organizational, socioeconomic, and attitudinal – and how utilization of such knowledge may be seen as both conceptual (what we think about knowledge) and instrumental (how we use knowledge)(Diehr and Gueldenberg Citation2017). This starting point can be used to analyse the role of knowledge production and subsequent dissemination in transit infrastructure investment planning processes. The decision-making process is shaped by several factors, including technical feasibility, economic viability, environmental consequences, climate considerations, and heritage conservation. Various stakeholders have a role in this process by contributing their knowledge, which is then incorporated into concept studies and subsequent planning phases.

Path dependency explores the concept of path dependency in the context of transport planning and investigates how historical decisions, previous infrastructure projects, and institutional factors influence the direction of current planning efforts (see ). It also analyses the role of existing policies, regulations, and planning practices in shaping the options considered in the appraisal and concept study phases.

3. Research design and material

3.1. Single case study design

This article is based on a single case study. As research on the planning processes in large and long-lasting investment projects is within a site-specific and contextual scope, it makes sense to use a case study design for such research (Yin Citation2009). Several scholars have argued that a well-outlined case, described in detail and with reasonable and understandable findings, is suitable for generalizations and conclusions (Flyvbjerg Citation2006; George and Bennett Citation2005; Yin Citation2009). Flyvbjerg (Citation2006) argues that illuminating critical issues in a critical case, due to an ‘information-oriented selection’, enables logical deductions to evolve into new knowledge. The case in this research project is large in regard to both cost and complexity, and the material analyses an ongoing process over 13 years. The implementation (the actual building) has not yet begun, pending a final decision and funding in the Norwegian parliament.

Using critical discourse analysis, this paper explores the texts, discourses, and structures that comprise the case’s research objects, represented first and foremost by two major documents, followed by an investigation of minutes, correspondence, and debates in traditional and new media. We use these documents to study how different possible fixed link concepts have been launched, analysed, and weighed against each other in the initial battle to become the preferred option, which will be subject to further processing until the final decisions on financing and construction.

The material used in this article covers the period 2006–2019. In addition to the two documents mentioned above, we have read and analysed political documents from decision-making processes, using qualitative tools to extract keywords and strings related to the case. A search of official databases was also conducted. Newspaper and debate articles, political documents, and minutes of meetings, as well as monitoring activity on various Facebook groups and pages that can shed light on the case, were read thoroughly ().

Table 1. Empirical material.

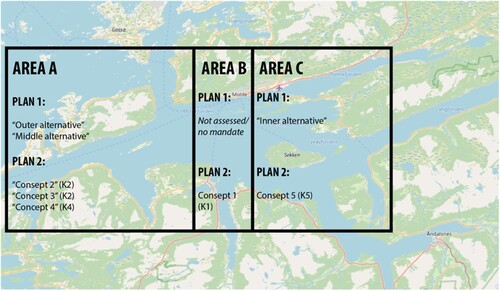

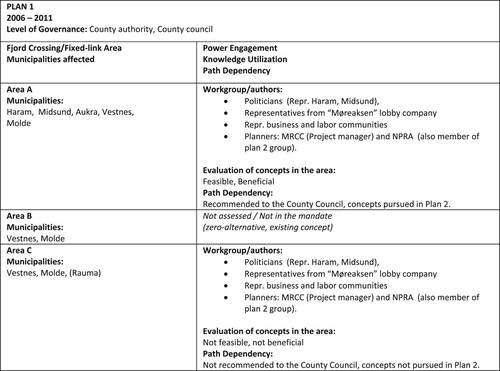

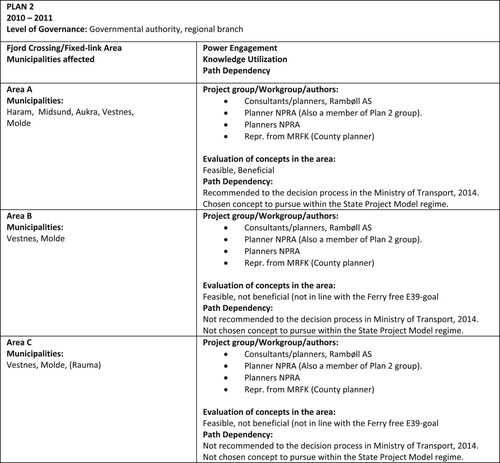

The first in-depth plan reading and analysis was based on Møre and Romsdal County Municipality’s (Citation2011) transport plan and concept appraisal document, which includes a concept recommendation for a desired Romsdalsfjord fixed link crossing. This document represents a regional concept assessment document and will be referred to in this article as Plan 1. The second document is part of the state/governmental process that all megaprojects must go through within the governmental planning regime. This document is the formal document upon which the final decision of which concept to select is based. It represents a governmental concept assessment document and will be referred to in this article as Plan 2 (NPRA Citation2011).

Both concept appraisal documents (Plan 1 and Plan 2) target a wider geographical area. This article only examines issues regarding those parts of the plans that address the E39 Romsdalsfjord fixed link crossing.

3.2. Critical discourse analysis

This article examines how an empowered actor at the start of the planning process set the stage for the official superior planning that would inform the final decision-making process. Documents and processes are analysed using critical discourse analysis. The concept of discourse appears frequently in discussions, debates, and everyday speech, implying an arena in which different meanings and visions appear in different contexts. The aim of discourse is to understand the world or a part of it. Jørgensen and Phillips (Citation2002) define discourse as the emergence and communication of diverse views or opinions. Norman Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis (CDA) examines textual material and its contextualization within a larger framework. Fairclough (Citation2003) defines critical discourse analysis as transdisciplinary, including theoretical and methodological aspects. Textual analysis alone examines discourses microscopically. By examining how texts express different political ideologies through practices and discourses, one can zoom out to a macro perspective. Fairclough and Fairclough (Citation2012) define social life as a social reality that emerges from social events, practices, and structures – from micro to macro. Fairclough (Citation2003) proposes two concurrent methods for CDA: linguistic analysis of texts and social science analysis. This article combines such text analysis with power analysis, theories on knowledge development, and path dependency.

Writing occurs in a social context, requiring a broader examination than individual words and sentences (Fairclough Citation2003). Language, particularly about specific social domains or practices, adds to Fairclough’s discourse conceptualization. A distinct political language has developed (Fairclough and Fairclough Citation2012). Another view is that discourse builds societal structures based on specific perspectives.

This study combines three dimensions: text analysis, discourse analysis, and macrosocial factors such as ideology and politics. Fairclough and other scholars have stressed that theese three dimensions are not hierarchically ordered by importance. The dialectic correlation between these dimensions is intriguing, and researchers can use the three dimensions depending on their goals (Fairclough Citation2003; Skrede Citation2017). Critical discourse analysis (CDA) allows the study of how power dynamics and relationships among stakeholders and between stakeholders and society affect knowledge generation over time.

4. Introduction to the Norwegian context

Norway is a diverse country in northern Europe, and its fjords, mountains, and pristine wilderness may affect transportation infrastructure. It is challenging to create an efficient transportation system that connects communities across the country's rugged terrain while maintaining sustainability goals.

The Norwegian transport landscape has changed significantly in recent years. As of 2022, the country has 100,000 kilometres of public roads, which are vital for mobility and connectivity. Norway's 1,200 tunnels, spanning 1,500 kilometres, are also notable. The Norwegian Public Roads Administration (NPRA) manages these complex roads and tunnels and 18,000 bridges nationwide. Infrastructure statistics demonstrate the nation's commitment to efficient transport and set the stage for studying road safety, vehicle technologies, and their effects on public health and the environment.

The evaluation of most infrastructure projects typically revolves around their economic advantages (Venables Citation2007; Vickerman Citation2007; Vigren and Ljungberg Citation2018). Consequently, initial assessments often advocate for the enhancement and enlargement of the regions impacted by such projects. Nevertheless, comprehensive evaluations of alternative solutions typically encompass the rationality from the body of literature within transportation engineering and economics, with its assumptions that some sort of rational decision-making should be made based on the results from statistical analysis and mathematical models (Cascetta et al. Citation2015). Such simulations as part of planning processes, that explicitly considers public engagement, contributes to overcome barriers that could stop the planned implementation (Russo and Rindone Citation2023). Examination of both established and potentially novel technical feasibility and land use impact in concept studies also encompass various aspects such as climatic, environmental, and heritage conservation considerations and knowledge. Such approach is in line with both national and international goals stated in e.g. Agenda 2030 (UN Citation2024), to which in SDG target 9.1 refer to robust, dependable, sustainable, and resilient infrastructure, both regionally and across borders, to ensure economic growth and enhance human welfare. Previous studies conducted by several scholars indicate that there may be additional factors beyond fundamental technical and economic perspectives that influence early forecasts and estimates (Flyvbjerg and Bester Citation2021; Sager Citation2016; Welde et al. Citation2014; Welde and Tveter Citation2022). Even though the cost-effectiveness of the Norwegian cross-sector appraisal regime has been deemed unfeasible, certain projects have the potential to align with political priorities and address societal needs (Volden and Samset Citation2017).

The importance of regional planning cannot be overstated when it comes to the development and implementation of transport infrastructure megaprojects. According to Kadyraliev et al. (Citation2022), the presence of transport infrastructure plays a crucial role in fostering economic growth at a national level. There is a broad consensus among Norwegians, spanning political and ideological spectrums, in favour of allocating substantial resources towards the enhancement of rural transport infrastructure. The projects for such enhancement have the potential to significantly impact urban areas and their surrounding regions through the development of transport infrastructure such as highways, railways, airports, and seaports.

The allocation of funds towards transport infrastructure megaprojects in Norway has substantially risen since the implementation of the National Transport Plan in 2002. The shift in financial allocation towards transport infrastructure investments commenced during the 1960s and 1970s, albeit experiencing a decline in the early 1980s because of neoliberal policies aimed at reducing public expenditure, which were implemented as counteractive measures (Boge Citation2012). Since the emergence of Norway as a prominent oil-producing nation, effective governance in the 1990s and beyond, coupled with astute revenue management, has facilitated the expansion of resource allocation towards transport, particularly in rural areas.

4.1. The case study context

Empirical data is used to show how empowered stakeholders generate knowledge that helps identify a preferred solution in budgeting and megaproject construction. A thorough assessment is required before making such decisions. The Norwegian government's Utredningsinstruksen [Instructions for Official Studies] underpins the statement. This directive requires the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development to thoroughly research and consider all public investments before making decisions. shows the State Project Model, which ensures comprehensive evaluation and quality assurance of all process stages (Statens Prosjektmodell [State Project Model], Citation2019). This model applies to all state-funded projects worth over 1 billion NOK. This article analyses empirical data to determine how a fixed link concept achieved the QA1 milestone.

The feasibility study Plan 2 in this study's empirical material is shown in . This feasibility study is named Konseptvalgutredning (KVU), or ‘Concept Selection Study’ in English. After a concept is chosen, quality assurance (QA1) continues with an external evaluation. After quality assurance, the selected concept enters conceptual pre-project development. There is only one concept under consideration for development. The chosen concept meets the National Transport Plan criteria. Projects seeking funding and parliamentary approval must be included in this plan. After developing the selected concept to a certain level of detail, an impartial assessment agency performs quality assurance (QA2). The QA2 results that support the presented facts indicate readiness for final decision-making and construction. Project goals are assumed to be met.

4.2. The E39 Romsdalsfjord fixed link crossing case

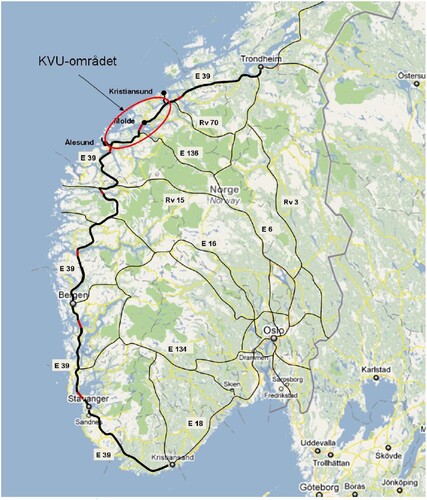

The Norwegian E39 Romsdalsfjord fixed link procedure is examined in this case study (). The National Ferry-Free E39 Fixed Link Initiative (NPRA Citation2012) aims to create a fast, uninterrupted roadway connection between Kristiansand and Trondheim without ferry crossings. The Romsdalsfjord crossing subproject has sparked public debate in affected areas.

In 2014, the government decided which of the relevant fixed link concepts for crossing Romsdalsfjord should be assessed in detail to implement the road project through the Norwegian planning regime for major road projects. The E39 Ålesund-Molde subproject, with the associated fjord crossing of Romsdalsfjord, was first mentioned in the National Transport Plan in 2019 (Nasjonal transportplan [National Transport Plan], Citation2021).

Two conflicting views about the selected concept emerged: 1) the concept was chosen after a thorough examination under democratic rules (and was therefore legitimate), and 2) the concept was chosen without any real competition, since the other possible alternatives were ‘written off’ before they were submitted to the decision-maker.

As of today, the chosen concept has reached the final rounds. The second quality assurance (QA2 in ) has been executed and has gained initial funding. The project now aims for the ‘last mile’ budgeting approval and final decision-to-build.

One central element in both documents, as well as in the discourses that have arisen in the period investigated in this paper, is a heavy emphasis on argumentation related to the effects of the plan and its result – that is, a fixed link connection that will benefit both drive-through traffic and local development in the form of wider economic benefits.

The government evaluated fixed link concepts for crossing Romsdalsfjord in 2014. The goal was to complete the road project within Norway's major road project planning regime. The 2019 National Transport Plan initially included the E39 Ålesund-Molde subproject and Romsdalsfjord crossing.

Different views on the process that led to the chosen concept have emerged over the years after 2014. Nevertheless, the proposal was legitimized by a presumptive democratic evaluation.

shows that the second quality assurance (QA2) process has begun and secured its initial funding. The project seeks to garner budgetary approval for the ‘last mile’, or final phase: Decision to build.

This study examines plan impact and outcome documents and discourses. By utilizing the suggested analytical framework, we have used the E39 Romsdalsfjord fixed link project to help us understand how power dynamics, knowledge acquisition, and path dependency affect transportation planning ().

5. Findings and discussion

In the following sections, we explore planning practices, stakeholder engagement, knowledge utilization, and path dependency in the context of the E39 Romsdalsfjord project (see process overview in and below). We uncover the complexities faced by decision-makers, the influence of historical decisions on current practices, and the interplay between knowledge, discourse, and stakeholder agency in shaping the planning process.

5.1. Stakeholder engagement is empowering discourse and practice

The importance of recognizing and understanding power dynamics is highlighted through the empirical material examined in this section. As Flyvbjerg’s (Citation1998) findings in the Aalborg Project indicate (see Section 2.1), one can argue that the findings of this study indicate that the initially provided planning mandate was to highlight democratic-oriented rational arguments. Nevertheless, it is unclear how much the process and text are based on rational evaluations and whether they can withstand critical scrutiny. Decisions may not always be as rational or democratic as they initially seem. The findings indicate that power should not be disregarded during the planning process and that the institutional bodies that establish and organize planning processes should pay attention to the forces at play.

Notably, the county council appointed biased individuals to the work task force to evaluate all the fjord crossing options. The company, Møreaksen AS, was given the authority to guide the process due to its seat in the workgroup. In addition, the study's findings show that individuals held dual roles in the form of involvement in the abovementioned company, and municipal cooperative bodies were also represented in the group. The group's leader had a specific dual role here (see and below).

The allocation of work task forces in Plan 1 gives stakeholders authority. If stakeholders have specific goals, they may rationalize processes and texts to achieve them. Rationality involves justifying personal goals, and hence rational behaviour refers to when a person’s actions achieve their goal (Etzioni Citation2010; Østerud Citation2002). People rationalize to understand and justify their actions in various contexts.

The findings of this study indicate that the company Møreaksen AS is actively engaged in the planning process. Notably, the company's involvement extends beyond mere participation, as it also contributes both strategically and operatively to the planning. The company was represented in the work group and, at the same time, acted as a financial contributor to geological surveys in Area A (see Section 5.3 for further findings and discussions on this company`s role). Furthermore, it is also worth highlighting that representatives from the Møre and Romsdal County Municipality (MRFK) and the Norwegian Public Roads Administration (NPRA) were concurrently present in both phases of the planning process, denoted as Plan 1 and Plan 2. This organizational structure of task forces prompts inquiries concerning the extent of the engagement and influence exercised by various actors and stakeholders in shaping the textual and discursive representations of knowledge, a theme underscored by Flyvbjerg (Citation1998). The next section will elaborate on the knowledge development in the empirical material.

5.2. Knowledge utilization is enabled through expertise

Excerpts from Plan 2 show the extensive use of assumptions. The modality regarding the Veøya alternative (Concept 5c) is both epistemic (e.g. ‘will be’, ‘can’, ‘cannot’) and deontic (e.g. ‘is’, ‘ought’, ‘should’, ‘must’) (Fairclough Citation2003). The assumptions regarding feasibility within the plans are first and foremost attached to ship traffic fairways, floating bridges, and heritage conservation issues.

Analysis of the plans and the correspondence between the planning organization and the Norwegian coastal authorities shows that the latter initiated a discussion on whether alternative fairways could be made. These reflections were briefly taken into the text in Plan 2:

A floating bridge will impede maritime traffic in the fjord. Consequently, the maritime traffic currently traversing to and from Åndalsnes will need to establish a new navigational route on the northern side of Sekken. Preliminary assessments, conducted in consultation with the Norwegian Coastal Administration (Kystverket), suggest the feasibility of such an alteration. Notably, there has been no prior construction of floating bridges of comparable length nearby, which introduces an additional element of uncertainty about feasibility. (NPRA Citation2011, 52, author’s translation)

The Veøya alternative's potential inclusion or exclusion in the planning process, involving heritage preservation and construction/land use, seems inadequately addressed in Plan 2. Neither did the subsequent quality assurance process address this issue at all. Despite the possibility of planning and building alternative 5C outside heritage boundary regulations, planners and quality assurances assumed the heritage authorities would strongly object, and therefore this alternative would fall. This study does not find any evidence that such a discussion was held previously with national heritage authorities, and even if they did so, the outfall of this issue would be uncertain. Occasionally, the interests of society at large might trump the interests of nature, the environment, and heritage.

The knowledge incorporation and assumptions in the planning process could be seen as a practical strategy used by the actors and stakeholders to promote their ideas. The framework's knowledge utilization conceptualization shows how stakeholders value technical feasibility, environmental impacts, and economic viability.

Moreover, another discourse was emphasized, namely a heritage-value discourse:

c) A variant with bridges via Veøya to Nesjestranda has also been considered. This will, however, cause encroachment on Veøya, an island with especially important protected historical-cultural monuments and a land conservation area. Such a solution will be of little relevance with better options available. In addition, it gives a slight increase in travel time compared to variant b. (NPRA Citation2011, 52)

Plan 2 E39 Ålesund-Bergsøya concludes with the following information:

If technological developments indicate that the costs and uncertainty of long floating bridges will be significantly lower than today, there will be room to make a new assessment of Concept K5, the Sekken concept. (NPRA Citation2011, 89)

5.3. Path dependency timelines

The theoretical framework's concept of path dependency gained tangible expression in the planning process. The empirical analysis in this study has shed light on how historical decisions and institutional contexts provided the foundation for the discourse and practices in the case study, manifesting themselves through the set-up of plans and the overlapping processes they represented. The empirical material shows that continuity was emphasized by the decision-makers in the county council. When the politicians at the county level saw the results of the NPRA planners’ work coming back for a political endorsement (such endorsement is part of the institutional governance practice that is carried out in decision-making in such large projects), continuity from Plan 1 to Plan 2 was addressed.

The consultation response given by Møre and Romsdal County Municipality regarding Plan 2 E39 Ålesund – Bergsøya was as follows:

In advance of Plan 2, MRFK has prepared its plan (… .) [Plan 1]. We see that the plan [Plan 2] is building on this document [Plan 1] and would like to point out that it is very positive that the county municipality’s role as a regional development actor has been taken into consideration. (Møre og Romsdal County Municipality Citation2012, 2)

The planning process itself (Plan 1) and the technical and physical assessment work went hand in hand with extensive geological excavation work (reflected in Chapter 3 and Section 5.5 of Plan 1). Given the scope, these assessments were performed simultaneously, or almost simultaneously, with the concept evaluations, but not for all concepts – only for the winning concept, Møreaksen. Based on political decisions in the county council early in the process, the municipality budgeted up to 5 million NOK for the geological surveys for the fjord crossings south and north of Romsdalsfjord, but in the case of Romsdalsfjord, the surveys were funded by Møreaksen AS and the Norwegian Public Roads Administration. In other words, one of the stakeholders was given the assignment to execute the technical planning initiatives and was in the driving seat during the overall planning process. At the same time, the County Municipality decided to contribute 1.5 million NOK directly to Møreaksen AS in the form of a share issue/transaction.Footnote4 The first question above thus incorporates the main essence of the public critique and discourses regarding the company Møreaksen AS, both a stakeholder and a player steering the process from within. The leader of ROR (see footnote 1 above) was identical to the mayor of the Midsund municipality (which would benefit from Møreaksen AS’s preferred concept being chosen), who also simultaneously held formal positions in Møreaksen AS (Møre og Romsdal County Municipality, Citation2011, 7).

The gradual shift in allocation of resources to transport infrastructure projects in rural areas set the stage for the project's emphasis on megaprojects. The interplay between historical decisions and present practices echoes the methodological framework's emphasis on the structural underpinnings of planning processes. Institutional factors not only influenced the discourse but also dictated the options considered and the trajectory of planning.

By using epistemic modality in combination with existential and value character assumptions, one can rationalize actions by controlling the knowledge production in the planning. The planners take for granted that regionalization (regionforstørring in Norwegian, meaning ‘region enlargement’) is something that can be achieved to a greater degree by making the fjord crossings ferry-free. Thus, one excludes a debate that could also potentially have addressed technological developments related to ferries, for example, through the development of environmentally friendly, fast, and perhaps even autonomous ferries. The planners may have faced a dilemma here between a politically important mandate (a ferry free fjord crossing) and the instructions derived from the state project model (to always consider the zero-alternative, improving the existing concept).

The knowledge production in Plan 1 is also central even when the discussion is extended into Lukes (Citation2005) third dimension: structural power, in which a silent and diffuse structural form of power manifests itself by making others wish for the same thing as oneself. Through the nominalisations identified in the texts, ‘regional expansion’ is a concept influenced by theories of growth and regional development (Engebretsen and Gjerdåker Citation2010). Explanations arise within political ideologies and dogmas for what kind of society one wants to live in and what societal tasks can and should be solved nationally and regionally. The same applies to the question of institutionalized power (Lukes Citation2005; Østerud Citation2002). Political and administrative processes, and the formal and informal rules of how things are done, often propagate from a macro level down to the micro level. In the production of text (a social event in CDA) about economics, technical, and environmental or heritage conservation practices in various alternative solutions, knowledge production appears on a macro level in the way in which one conveys potential and opportunities. Regardless of the financial, technical, or environmental resources one may have available, the use of force in combination with language can be seen as a social structure in itself (Fairclough Citation2003). Potential and opportunities can be defined through text production and stakeholder actions.

This article has identified discourses related to diverse topics such as technical feasibility, nature, the environment, and cultural heritage. In addition to these discourses, there is an overarching discussion about the extent to which transport investments contribute to the development of both society as a whole and the relevant regional communities. These individual discourses are also identified interdiscursively, in that they occur across plans and processes as well as forming part of the public debate and conversation. In both Plans 1 and 2, it is possible to identify different discourses that can also be identified in other similar plans, reports, and minutes. These discourses are well anchored in the overall goals and mandates for the Ferry-Free E39 project, and so it is also natural that precisely these discourses are emphasized in the documents. The professional identity created in the social events and social practices of which they are a part can influence the way the planners write (Fairclough Citation2003; Skrede Citation2017). Thus, one can argue that Plan 1 and Plan 2 documents are characterized by a bureaucratized planning language within the context in which they operate.

One of the alternative concepts fell out early in the formulation of Plan 1. It did not ‘work’ in Plan 2 either, or the concept was not pursued any further.

6. Conclusion

Regional planning procedures follow universal planning and participation principles and refer to the commonly assumed and widely interpreted objectives of the Norwegian planning system for large-scale projects. The Ferry-Free E39 project and other large-scale state infrastructure projects typically start with a formal concept evaluation, such as Plan 2. This study has examined power engagement, knowledge use, and path dependence in early transport infrastructure planning. By focusing on Norway's E39 Romsdalsfjord fixed link project, the study has examined how stakeholder actions affect project outcomes. Using theoretical perspectives and critical discourse analysis, the dynamic relationship between power, knowledge, and path dependency has been identified.

Ethics play a significant role at the intersection of knowledge and action in planning, as identified by Campbell (Citation2012) and Winkler and Duminy (Citation2014). The present study`s empirical material indicates that the casting of the work group members in Plan 1 empowered stakeholders advocating for the concepts in Area A. A broader group composition could have led to a broader discussion of Area C alternatives. Unfortunately, those advocating for the Area C alternatives had no representatives in the working group. The evidence in the findings confirms that the knowledge developed in Plan 1 was transferred to Plan 2. A trading of expert knowledge took place, influencing the planner behaviour in Plan 2 (Møre og Romsdal County Municipality Citation2012, 2; Tennøy et al. Citation2016). Planners may dismiss expert knowledge if it conflicts with their objectives or ideals. Continuity was maintained by the fact that the two planning organizations were represented in their respective planning groups. Such continuity may lead to self-censorship when planners are faced with new knowledge obtained from more thorough deliberation or when politicians are tasked with balancing expert knowledge with the political ambitions that lie inherently in their mandate (Vigar Citation2017). As Sager (Citation2006) points out, policies and initiatives should not rely solely on instinct, ideology, and political factors. Hence, planners should not disregard the knowledge acquired through the planning process.

The analysis found evidence of how the regional plan (Plan 1) affected the national plan (Plan 2) with respect to operational execution and knowledge generation as the groundwork for decision-making. The implications of the article's findings extend and contributes to both planning theory and the planning practice in Norwegian as well as in other geographical contexts and planning organizational bodies. While the recognition of the importance of public involvement in knowledge-based transport planning is already well established and integrated into the planning system, there is a clear necessity for a bottom-up planning approach. The case study's findings contribute to further research on stakeholders’ involvement in transportation infrastructure megaproject planning and whether actors’ or stakeholders’ contributions and efforts exclude alternative solutions during planning. In reference to the 2nd research question, this paper's case study shows that ‘Power engagement’, ‘Knowledge utilization’, and ‘Path dependency’ are inter-connected almost regardless of how a planning process is initially set up and carried out. A lack of a ‘universal’ approach to planning at the regional level, as pointed out by Russo and Rindone (Citation2021), shows that a less random and more holistic approach to transport planning could be beneficial. Preferably supported by recognized methods for quantitative transport system modelling (Cascetta et al. Citation2015). Especially when it comes to very costly infrastructure projects. Future research may investigate whether policymakers could benefit from adopting such comprehensive approach to the design of major infrastructure initiatives. Such an approach may involve authorizing a more distant planning organization to oversee regional and local projects while ensuring that citizen participation remains a crucial component.

The case evidence in this article supports the underlying assumption that stakeholder involvement in active and operational planning influenced the project in a specific direction in the form of a final decision to build a concept in Area A. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether this will occur.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Although it is possible to distinguish between the concepts of actors and stakeholders, this article does not make use of such distinction.

3 The same distance between the same geographical start/stop was measured to approx. 5000 meter in Plan 1

4 From meeting minutes: decision made to participate in share issue, Municipal County Council 13.06.07 (T-48/07), final budgeting adopted in case (T-87/07 A).

References

- Arthur, W. 1994. Increasing Returns and Path-Dependency in the Economy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Bachrach, P., and M. Baratz. 1970. Power and poverty: Theory and practice.

- Boge, Knut (2012). “Stamvegpolitikk i Norge, Sverige og Danmark etter andre verdenskrig.” In Stormbringer, Geir Atle, and Hole, Berit (Eds.), *Årbok for Norsk vegmuseum 2012* (pp. 135–171). Oslo/Lillehammer: Statens Vegvesen Norsk Vegmuseum.

- Booth, C., and T. Richardson. 2001. “Placing the Public in Integrated Transport Planning.” Transport Policy 8 (2): 141–149. doi:10.1016/s0967-070x(01)00004-x.

- Campbell, H. 2012. “Planning to Change the World.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 32 (2): 135–146. doi:10.1177/0739456x11436347.

- Cantarelli, C., D. Oglethorpe, and B. van Wee. 2022. “Perceived Risk of Lock-in in the Front-end Phase of Major Transportation Projects.” Transportation 49 (2): 703–733. doi:10.1007/s11116-021-10191-7.

- Cascetta, E., A. Cartenì, F. Pagliara, and M. Montanino. 2015. “A new Look at Planning and Designing Transportation Systems: A Decision-Making Model Based on Cognitive Rationality, Stakeholder Engagement and Quantitative Methods.” Transport Policy 38: 27–39. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.11.005.

- Dahl, R. 1957. “The Concept of Power.” Behavioral Science 2 (3): 201–215. doi:10.1002/bs.3830020303.

- Diehr, G., and S. Gueldenberg. 2017. “Knowledge Utilisation: An Empirical Review on Processes and Factors of Knowledge Utilisation.” Global Business and Economics Review 19 (4): 401–419. doi:10.1504/GBER.2017.085024.

- Dooms, M., A. Verbeke, and E. Haezendonck. 2013. “Stakeholder Management and Path Dependence in Large-Scale Transport Infrastructure Development: The Port of Antwerp Case (1960–2010).” Journal of Transport Geography 27: 14–25. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.06.002.

- Engebretsen, Ø., and A. Gjerdåker. 2010. Regionforstørring: Lokale Virkninger av Transportinvesteringer. Oslo: Transportøkonomisk institutt.

- Etzioni, A. 2010. Moral Dimension: Toward a new Economics. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Fairclough, N. 2001. “Critical Discourse Analysis as a Method in Social Scientific Research.” Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis 5 (11): 121–138.

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge.

- Fairclough, N., and I. Fairclough. 2012. Political Discourse Analysis: A Method for Advanced Students. London: Routledge.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 1993. Power has Rationality That Rationality Does not Know. Aalborg: Department of Development and Planning, Aalborg University.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 1998. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2013. “How Planners Deal with Uncomfortable Knowledge: The Dubious Ethics of the American Planning Association.” Cities 32: 157–163. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2012.10.016.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2017. “Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management, edited by Bent Flyvbjerg. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B., and D. Bester. 2021. “The Cost-Benefit Fallacy: Why Cost-Benefit Analysis Is Broken and How to Fix It.” Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 12: 395–419. doi:10.1017/bca.2021.9.

- Forester, J. 1989. Planning in the Face of Power. Berkely: University of California Press.

- Fylkeskommune, M. o. R. 2011. Temaplan samferdsel: Ferjefri E39 i Møre og Romsdal.

- George, A., and A. Bennett. 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Grange, K. 2017. “Planners – A Silenced Profession? The Politicisation of Planning and the Need for Fearless Speech.” Planning Theory 16 (3): 275–295. doi:10.1177/1473095215626465.

- Grange, K., and T. Winkler. 2023. “Introduction to the Handbook on Planning and Power.” Handbook on Planning and Power, 1–10. doi:10.4337/9781839109768.00006.

- Gunder, M., A. Madanipour, and V. Watson, eds. 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory. London: Routledge.

- Hansson, L. 2008. Spela med tiden-kommunalpolitiska strategier för att nå inflytande i trafikfrågor.

- Haugaard, M. 2012. “Rethinking the Four Dimensions of Power: Domination and Empowerment.” Journal of Political Power 5 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1080/2158379X.2012.660810.

- Healey, P. 1992. “Planning Through Debate: The Communicative Turn in Planning Theory.” Town Planning Review 63 (2): 143. doi:10.3828/tpr.63.2.422x602303814821.

- Innes, J., and D. Booher. 2016. “Collaborative Rationality as a Strategy for Working with Wicked Problems.” Landscape and Urban Planning 154: 8–10. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.03.016.

- Jørgensen, M., and L. Phillips. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781849208871.

- Kadyraliev, A., G. Supaeva, B. Bakas, T. Dzholdosheva, N. Dzholdoshev, S. Balova, Y. Tyurina, and K. Krinichansky. 2022. “Investments in Transport Infrastructure as a Factor of Stimulation of Economic Development.” Transportation Research Procedia 63: 1359–1369. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2022.06.146.

- Low, N., and R. Astle. 2009. “Path Dependence in Urban Transport: An Institutional Analysis of Urban Passenger Transport in Melbourne, Australia, 1956–2006, Transport Policy, 1956–2006.” Transport Policy 16 (2): 47–58. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2009.02.010.

- Lukes, S. 2005. Power: A Radical View. 2nd ed. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan (In Association with the British Sociological Association).

- Lynch, R. 2014. “Fouvaults’s Theory of Power.” In Michel Foucault. Key Concepts, edited by D. Taylor. Durham: Acumen.

- Miller, D. 1993. “Political Time: The Problem of Timing and Chance.” Time & Society 2 (2): 179–197. doi:10.1177/0961463X93002002003.

- Møre og Romsdal County Municipality. 2012. Hearing: KVU E39 Skei-Valsøya (Attachment to T-14/12). Molde: Møre og Romsdal County Municipality.

- Næss, P., L. Hansson, T. Richardson, and A. Tennøy. 2013. “Knowledge-based Land use and Transport Planning? Consistency and gap Between “State-of-the-Art” Knowledge and Knowledge Claims in Planning Documents in Three Scandinavian City Regions.” Planning Theory & Practice 14 (4): 470–491. doi:10.1080/14649357.2013.845682.

- Nasjonal transportplan [National Transport Plan]. 2021. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/transport-og-kommunikasjon/nasjonal-transportplan/id2475111/.

- Ninan, J., A. Mahalingam, and S. Clegg. 2019. “External Stakeholder Management Strategies and Resources in Megaprojects: An Organizational Power Perspective.” Project Management Journal 50 (6): 625–640. doi:10.1177/8756972819847045.

- North, D. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- NPRA. 2010. Prosjektplan Konseptvalgutredning E39 Ålesund - Bergsøya [Project plan].

- NPRA. 2011. Konseptvalgevaluering E39 Ålesund - Bergsøya [Concept Evaluation Report]. Retrieved from https://kudos.dfo.no/dokument/11033/kvalitetssikring-av-konseptvalg-ks1-e39-skei-valsoya.

- NPRA. 2012. Ferjefri E39 - Hovedrapport. Retrieved from https://www.vegvesen.no/globalassets/vegprosjekter/utbygging/ferjefrie39/vedlegg/ferjefrie39-rapport-20desember2012.pdf.

- Østerud, Ø. 2002. Statsvitenskap. Innføring i politisk analyse. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Pemberton, S. 2000. “Institutional Governance, Scale and Transport Policy – Lessons from Tyne and Wear.” Journal of Transport Geography 8 (4): 295–308. doi:10.1016/S0966-6923(00)00019-3.

- Pettersson, F. 2013. “From Words to Action: Concepts, Framings of Problems and Knowledge Production Practices in Regional Transport Infrastructure Planning in Sweden.” Transport Policy 29: 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2013.03.001.

- Pierson, P. 2000. “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review 94 (2): 251–267. doi:10.2307/2586011.

- Pierson, P. 2004. Politics in Time: History, Institutions and Social Analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Russo, F., and C. Rindone. 2021. “Regional Transport Plans: From Direction Role Denied to Common Rules Identified.” Sustainability 13 (16): 9052. doi:10.3390/su13169052.

- Russo, F., and C. Rindone. 2023. “Logical Framework Approach in Transportation Planning: The Passenger Services in the Messina Strait.” Transportation Research Procedia 69: 855–862. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2023.02.245.

- Sager, T. 2006. “The Logic of Critical Communicative Planning: Transaction Cost Alteration.” Planning Theory 5 (3): 223–254. doi:10.1177/1473095206068629.

- Sager, T. 2016. “Why Don’t Cost-Benefit Results Count for More? The Case of Norwegian Road Investment Priorities.” Urban, Planning and Transport Research 4 (1): 101–121. doi:10.1080/21650020.2016.1192957.

- Skrede, J. 2017. Kritisk diskursanalyse. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Statens Prosjektmodell [State Project Model]. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/okonomi-og-budsjett/statlig-okonomistyring/ekstern-kvalitetssikring2/hva-er-ks-ordningen/id2523897/.

- Tennøy, A., L. Hansson, E. Lissandrello, and P. Næss. 2016. “How Planners’ use and non-use of Expert Knowledge Affect the Goal Achievement Potential of Plans: Experiences from Strategic Land-Use and Transport Planning Processes in Three Scandinavian Cities. Progress in Planning 109: 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2015.05.002.

- Terramar and Oslo Economics. 2012. Kvalitetssikring av konseptvalg (KS1). E39 Skei - Valøya. Oslo: Terramar AS and Oslo Economics AS.

- Torfing, J. 2001. “Path-Dependent Danish Welfare Reforms: The Contribution of the New Institutionalisms to Understanding Evolutionary Change.” Scandinavian Political Studies 24 (4): 277–309. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.00057.

- Tornberg, P., and J. Odhage. 2018. “Making Transport Planning more Collaborative? The Case of Strategic Choice of Measures in Swedish Transport Planning.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 118: 416–429. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2018.09.020.

- United Nations. 2024. SDG Goal 9. Retrieved from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal9#targets_and_indicators.

- Upham, P., P. Kivimaa, and V. Virkamäki. 2013. “Path Dependence and Technological Expectations in Transport Policy: The Case of Finland and the UK.” Journal of Transport Geography 32: 12–22. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.08.004.

- Venables, A. 2007. “Evaluating Urban Transport Improvements: Cost–Benefit Analysis in the Presence of Agglomeration and Income Taxation.” Journal of Transport Economics and Policy (JTEP) 41 (2): 173–188.

- Vickerman, R. 2007. “Cost – Benefit Analysis and Large-Scale Infrastructure Projects: State of the Art and Challenges.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 34 (4): 598–610. doi:10.1068/b32112.

- Vigar, G. 2017. “The Four Knowledges of Transport Planning: Enacting a More Communicative, Trans-Disciplinary Policy and Decision-Making.” Transport Policy 58: 39–45. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.04.013.

- Vigren, A., and A. Ljungberg. 2018. “Public Transport Authorities’ use of Cost-Benefit Analysis in Practice.” Research in Transportation Economics 69: 560–567. doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2018.06.001.

- Volden, G., and K. Samset. 2017. A Close-up on Public Investment Cases. Lessons from Ex-Post Evaluations of 20 Major Norwegian Projects. Trondheim: Ex ante Academic Publisher.

- Welde, M., K. Samset, B. Andersen, and K. Austeng. 2014. Lav Prising -Store Valg. En studie av underestimering av kostnader i prosjekters tidligfase. Concept rapport NR. 39. Trondheim: Ex Ante forlag.

- Welde, M., and E. Tveter. 2022. “The Wider Local Impacts of new Roads: A Case Study of 10 Projects.” Transport Policy 115: 164–180. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.11.012.

- Weston, J., and M. Weston. 2013. “Inclusion and Transparency in Planning Decision-Making: Planning Officer Reports to the Planning Committee.” Planning Practice and Research 28 (2): 186–203. doi:10.1080/02697459.2012.704736.

- Williamson, O. 1993. “Contested Exchange Versus the Governance of Contractual Relations.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7 (1): 103–108. doi:10.1257/jep.7.1.103.

- Winkler, T., and J. Duminy. 2014. “Planning to Change the World? Questioning the Normative Ethics of Planning Theories.” Planning Theory 15 (2): 111–129. doi:10.1177/1473095214551113.

- Wright, K., and H. Dia. 2019. “Path Dependence: A Framework for Understanding Active Transport Implementation.” Journal of Transport & Health 14: 100749. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2019.100749.

- Yin, R. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Vol. 5). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.