ABSTRACT

While the construction of migration as a security threat in Europe has been thoroughly examined, how different groups of migrants become targets of security concerns has not received similar attention. In its fight against irregular immigration, the European Union uses visa liberalisation agreements with neighbouring states as an incentive for cooperation on migration control. At a first glance, this strategy appears somewhat contradictory, as visa liberalisation potentially increases the share of visa overstayers among irregular migrants. Through analysis of the annual “Risk Analysis” reports between 2015 and 2020 published by EU’s border and migration management agency, FRONTEX, this article shows that visa overstay is routinely left out of the agency’s security concerns of irregular migration, thus rendering risk assessments asymmetrically occupied with irregular migration by means of “illegal entry”. Although visa overstayers are not conceptualised as threats to security in discourse on par with other categories of irregular migrants, we find that they are increasingly subjected to a rationale of surveillance and risk.

Introduction

In the last decade, migration has become one of the most contested issues in European politics. Following the “migration crisis” of 2015, when Europe saw an unprecedented amount of people seeking refuge at its shores and physical borders, the pressure on the European Union to restrict access to Schengen territory grew drastically. Researchers have convincingly shown that the physical border practices of the EU have grown increasingly more repressive and the possibilities for migrants to access asylum processes has been reduced considerably in the past years (Frelick et al. Citation2016). As part of efforts to limit migration, externalisation of border control has been established an important policy tool of the EU (Lavenex Citation2006, Adepoju et al. Citation2010, Casas-Cortes et al. Citation2016). In part, the externalisation of border management happens through agreements with third countries to remove EU border checks away from the European borders. To incentivise such cooperation on border control, visa liberalisation or facilitation is often part of the agreement.Footnote1 Visa liberalisation or facilitation is the practice of removing obstacles that exist in acquiring a visa. This can be achieved by lowering the cost of visa applications, or removing demands, and thus enabling entry through visa-free travel or simplified visa processes. As Laube (Citation2019, p. 3) has shown, “taking over border responsibilities” has become an important bargaining tool in EU-third country relations, where, in exchange for visa liberalisation for their citizens, third countries can agree to reduce the transit possibilities for migrants en route to the EU.

However, the European Commission (EC) recognises that rather than having entered the EU irregularly, a majority of “illegal immigrants” in the Schengen area are more likely visa overstayers (European Commission Citation2020b).Footnote2 Given that many who become irregular migrants arrived at the Schengen territory with a visa in hand, the use of visa liberalisation agreements, as a part of an externalisation tool, to reduce immigration appears inconsistent. In the context of a Europe growing increasingly hostile to migrants, in particular those considered to be on European territory “illegally”, how can this use of practices, which might, in fact, generate more irregular migrants on the Schengen territory, be understood?

This article investigates the securitisation of migration as a constitutive part in the policies that are deployed in relation to migrants. While the securitisation of migrants and asylum seekers in the context of the EU has been thoroughly examined in previous research (Huysmans Citation2000, Neal Citation2009, Van Munster Citation2009, Léonard Citation2010, Lazaridis and Wadia Citation2015, Alkopher and Blanc Citation2017, Krotký and Kaniok Citation2020), differences in the securitising processes of different groups of migrants are often left out of the discussion or only implicitly mentioned. In part, we argue that this is because of a general bias within securitisation theory that makes it asymmetrically focused on the securitised objects and the actors or tools implicit in it, rather than the non-securitised ones. Drawing on securitisation theory to compare FRONTEX’s treatment of different migrant groups, this article argues that irregular migration by means of visa overstaying has largely, and routinely, been left out of the securitised discussion on migration. We find that migration through visa overstaying, that is, an irregular stay after a regular border passage, has not been conceptualised as a security problem to the same extent as migration through irregular border crossings. By not being subjected to the same kind of securitisation process, visa overstay has not been the target of restrictive policies at the same level as irregular border crossings. This, in turn, leaves room for the seemingly contradictory use of visa liberalisation agreements as a means to combat irregular migration. However, our findings point to a potential shift towards more securitised practices also towards visa-travellers, as seen in the development of more sophisticated monitoring technologies. This development might be further accelerated if there is a discursive shift where visa overstay becomes part of the broader narrative of border security.

The article is structured as follows. First, the concept of “irregular migration” in the context of Schengen is presented, along with an overview of the institutional framework of European visa-regimes. Then follows a presentation of the theoretical framework of securitisation theory that underpins the analysis. This section explains why both discourse and material securitisation practices need to be taken into account. In the third section, the case study of visa overstays and irregular migration in the context of FRONTEX is introduced, along with the methodical considerations of the analysis. Finally, a three-step analysis is carried out, followed by a discussion on how the case of FRONTEX can help us understand the apparent paradox in EU policies towards irregular migration.

Irregular migration and visa liberalisation agreements

Visa regimes are important policy tools for border control, as they enable screening in advance of potential border-crossers (Gülzau et al. Citation2016, p. 164). Visa requirements allow states to restrict access based on the risk assessment of potential terrorists and criminals as well as migrants (Czaika and Trauner Citation2017, p. 110). Thus, a visa regime is in itself a securitising tool, since visas are required specifically for travellers from countries whose populations are deemed potential threats (Balzacq Citation2008, p. 90). Globally, access to the Schengen Area is strikingly asymmetrically distributed, mirroring a global, long-term trend where access to free movement through travel has expanded for citizens of OECD countries, while citizens of non-OECD countries have not had the same expansion of privileges (Mau et al. Citation2015, Czaika and Trauner Citation2017).

Consequently, visa liberalisation and facilitation have become important instruments in the EU’s bilateral agreements (i.e. Mobility Partnerships) with neighbouring countries. Within the realm of these partnerships, visa liberalisation or facilitation agreements are used as incentives for cooperation on, for example, externalisation of border control (Laube Citation2019) and readmission agreements (Czaika and Trauner Citation2017, p. 113, El Qadim Citation2018). This process includes the labelling of the country in question as “safe” as to be able to follow through on readmission for nationals and third-country nationals alike. As Delcour (Citation2018, pp. 411–413) argues, there is a tension between the EU’s ambition to promote democratic values, and its own security preferences, with the latter often prevailing.

The Schengen agreement and the subsequent implementation of the common framework of the Schengen area have contributed to the securitisation of migration, not least because free internal movement was conditioned on the protection from external threats. As early as 2000, Huysmans argued that the spill-over from the internal market into a security cooperation placed migration in an institutional framework alongside other security concerns such as terrorism and transnational criminal activity, in effect criminalising both migrants and asylum-seekers (Huysmans Citation2000, pp. 756–757). Other scholars have shown that securitising discourses have routinely been used by policy makers and media as well as activists (Ceyhan and Tsoukala Citation2002, p. 24). In the context of the Schengen agreement, an irregular migrant is someone who has entered illegally, entered legally and then overstayed the visa-conditional period, or had their asylum claim rejected (European Commission Citation2020a). Important for the analysis at hand, both visa overstay and irregular border crossing without a successful asylum claim are considered irregular migration under the EU’s definition.

Owing to the nature of their situation, the total number of irregular migrants within the Schengen area at any given time is uncertain – in the words of Kelly (Citation1977), the task of measuring the irregular migrant population can be described as “counting the uncountable”. While this article is concerned with the securitisation of visa-overstaying specifically, this category is not often treated as a separate category statistically speaking. Rather, visa-overstayers are often grouped together with other non-EU nationals who are found irregularly present on the territory of an EU member state in the statistics. Substantial variation exists between the EU countries regarding how such these statistical categories are composed, and there are no comprehensive statistics on visa overstay numbers at the EU level at present.Footnote3 It has, however, been estimated that the share of irregular migrants present in the EU who first arrived as visa holders is substantial (see e.g. Jansen et al. Citation2014, Scheel Citation2018, European Commission Citation2020b). The lack of exact data on irregular migrants by means of visa overstaying in Europe speaks to the central hypothesis of this article, namely, that if visa overstayers were considered to be a greater threat to security, they would probably already be monitored more closely. More ambitious efforts to monitor overstay could be considered a securitising practice as well as a reaction to the perceived security threat that it poses. The use of visa liberalisation and visa facilitation processes presents an opportunity for more visa holders, and consequently, a potential for more visa overstayers. The lack of comprehensive reports on visa overstay and the use of visa liberalisation agreements indicates that there is ground for the argument that visa overstaying has been securitised to a lesser extent than irregular border crossings.

Externalisation of European border control

In recent decades, border walls and fences have become focal points in the development of hard borders as a strategy of border control. This development can be seen in various places around the world at an increasing rate (Simmons Citation2019). Border walls have two interlinked functions: they serve as physical structures that, often violently, stop people from crossing a border; and, as very visible symbolic markers of power, which serve simultaneously to deter border crossers and signal political decisiveness to domestic constituents. However, parallel to this development, border control is increasingly exercised away from territorial borders through internal and everyday bordering within domestic territory (Yuval-Davis et al. Citation2019) and through different forms of externalisation of border control. This development is seen in many places around the world (e.g. Walker Citation2018), not least in the European Union’s management of its external borders.

The externalisation of migration control occurs through a multitude of different practices at both the national and supra-state level, such as the diffusion of European border norms through international organisations, and within the transnational field of professionals (Fine Citation2018); or through bilateral and multilateral agreements with third countries (Laube Citation2019). Visa liberalisation agreements with European neighbour countries have become an important tool in the European externalisation of borders, with the purpose of exercising border control away from the European territory (Andersson Citation2016, p. 1056). Visa requirements can also be understood as an externalisation tool, since the de facto sites of border control then become the sites of visa issuance. Since the 2015 “migration crisis”, the EU has further accelerated its engagement with neighbouring countries within the realm of border control and migration as to limit the ability of migrants to reach the Schengen territory, for example through agreements with countries, such as Turkey, Morocco and Libya (FRONTEX Citation2020b, pp. 6–8).

The consequences of the European externalisation processes have been criticised for producing circumstances that contribute to a more perilous situation for migrants. Anderson (Citation2016, pp. 1060–1064) argues that the reduction of legal pathways to Europe, combined with harder border control, reinforces the discourse of exceptionalism and emergency regarding migration, which increases the need for more security measures at the border. The externalisation of European border control and the securitisation of migration are thereby mutually constitutive.

Securitisation as the framework for analysis

Buzan et al. (Citation1998, p. 23), part of the so-called Copenhagen School of Securitisation, defined securitisation as “the move that takes politics beyond the established rules of the game and frames the issue either as a special kind of politics or as above politics”. In other words, securitisation was conceptualised as a speech act that aimed to add an element of exceptionalism to a particular issue (Buzan et al. Citation1998, p. 21). Since then, securitisation theory has refocused beyond the securitisation through discourse. This article adheres to the tradition of defining security and insecurity as created not only by discursive elements but also by practices. In this “practice-based” approach, security is also performed by routine activities and specific ways of behaving – typically by bureaucrats or security professionals – within a particular field (Bigo Citation2002). Analyses, using this approach, focus on the use of instruments or tools, such as law (Basaran Citation2010); technology (Balzacq Citation2008); or the production of specific knowledge (Andrijasevic and Walters Citation2010) in securitisation processes. Balzacq (Citation2008, p. 78), for example, views the European information exchange systems, such as the Visa Information System (VIS), as securitising tools, which themselves become part of the securitisation process since they, by their very existence, designate their subjects as risky.

In the European context, a theoretical onset that includes various modalities of the bureaucracy of the EU is even closer to the realities of state of play. As argued by Neal (Citation2009, p. 351), the focus on bureaucratic processes of the EU is particularly important since “within the EU, [m]uch of what is being done in the name of security is quiet, technical and unspectacular … and just as much again does not declare itself to be in the name of security at all”. In reality, however, the actions of the bureaucratic actors are dependent on the legitimisation or authorisation on the politicians or high-level officials of the central EU institutions or member states (Van Munster Citation2009, p. 6). Evidently, the multi-level sui generis system of the European Union makes for a confusing case in identifying the (single) securitising actor and the (single) enabling audience, as originally formulated by the Copenhagen School. As a framework for analysis of the EU as a securitisation actor, Sperling and Webber (Citation2019) introduce the concept of “collective securitisation”. Their conceptualisation of securitisation adds “recursive interaction” between the EU (or, the EU institutions with judicial and executive autonomy) and its member states as a collective process of securitisation.

Similarly to Sperling and Webber, we conceptualise the processes that lead to securitisation as a collective process as well as a mix between “politics of exceptionalism” and “politics of routine”. In contrast to much previous research, however, the aim of this article is not to track a specific move of securitisation. Rather, the aim is to evaluate the variations in securitisation of different categories of “irregular migrants” in EU migration management. By conceptualising actors, instruments and tools as expressing and co-constructing securitisation, it enables this study to compare the different levels of securitisation. The understanding is that the actors of the EU diffuse securitised discourse between each other internally and that their internal dynamics, positions and relations of power or their precedence in their respective policy areas influence these processes. It assumes that the construction of a security threat is formed by the accumulation of several different actors’ and instruments’ securitising (or non-securitising) moves, discursive patterns or inherent security logics.

FRONTEX: key actor in the securitisation of migration

FRONTEX’s prevalent role in the securitisation of migration and asylum in Europe has been recognised by previous research. Léonard (Citation2010) argues that FRONTEX is a product of the securitising of migration in the EU. As such, it was not through FRONTEX that migration first became securitised, but FRONTEX’s practices contribute to the perpetuation of this securitisation and the institutionalisation of migration as a security threat (Léonard Citation2010). As the EU’s border and coast guard agency, its main tasks include monitoring “migratory flows”, and carrying our risk- and vulnerability assessments related to the management of borders. As such it is in a position to seriously influence the policies, discourses and operative direction of EU border control.

The rapid expansion of the agency’s mandate and budget (which rose from around 6 million euro in 2005 to over 333 million in 2019) (FRONTEX Citation2020a) in the past few years makes it, furthermore, particularly interesting in relation to the process of securitising of migration and its role in shaping EU policy in the post-“migration crisis” period. Within the scope of this expansion, the agency saw a transformation of its role as not merely an agency aimed at increased cooperation between member states in the realm of border control, but a common European coast and border guard in its own right.

As others have argued, visa-issuing practices in the EU are ultimately in the hands of member state and their officials, which do lead to variations in the outcome of bordering practices at the national level (Infantino Citation2016). It is, however, reasonable to assume that FRONTEX, given its risk assessment mandate and growing resources, would increasingly incorporate other types of bordering in their understanding of the management of European border control. Given FRONTEX’s central role in the management of European borders, it is a likely arena for securitising discourse on visa overstaying: if such discourse is not present in the context of FRONTEX, it is likely that it is even less securitised in other parts of EU discourse. If FRONTEX would include visa overstay in its assessment of risks, it is a signal that overstay is becoming part of the overall securitisation of migration in the EU.

To analyse the (potential) differences in the construction visa overstays and irregular border-crossers as security problems for the EU, we analyse FRONTEX’s annual Risk Analysis reports between 2015 and 2020. These reports function as FRONTEX’s “knowledge production”, and thus serve to inform the policy makers and the public alike using a language of knowledge and professionalism. Their wide scope serves the comparative aspect of the analysis, as all types of irregular migration are to be covered in the assessment of risks.

Method and structure of the analysis

To capture securitisation as both speech acts and practice, the analysis is divided into three parts. The first two of these focus on discourse in FRONTEX’s risk analyses between 2015and 2020, while the third part focuses on the practices and tools used by FRONTEX.

The analysis of securitisation in discourse within the scope of this article is two-fold. Firstly, the relative frequency of mentions of the categories “visa overstayer” and “illegal border crosser” the FRONTEX reports will be examined. This content analysis provides an initial understanding of what group(s) and means of migration are considered the most important threats. Since the central purpose of the analysed reports is to identify the “risks” in relation to migration and border control, a high number of mentions is here understood as a sign that there is significant attention being put on this particular group of migrants by FRONTEX.

The number of mentions of different migrant categories is not sufficient evidence that there is differentiated securitisation within the FRONTEX agency in itself. Thus, the second part of the analysis focuses on the explicit and non-explicit discursive representations of these two “types” of migrants. By identifying the referent object of the “threats” that these different types of migration pose; what meanings are attached to the lack of management of them; the nature of the solution to these problems, as well as the visual representation of migrants and migration in the reports, the analysis aims to deconstruct the material to identify differences in securitisation between them.

In the third part of the analysis, the securitising practices, instruments or tools in FRONTEX’s repertoire are analysed. First, drawing on Léonard’s (Citation2010, p. 327) definition of securitising practices as “activities that, in themselves, convey the idea that asylum-seekers and migrants are a security threat to the EU”, we identify such instruments or tools that (1) are usually deployed to control migration and border passage; or that (2) are “exceptional” in that it has not previously not been used within the realm of migration or border control in the EU. Second, the analysis identifies which group(s) of migrants that are the (primary) subject of this securitising practice, instrument or tool. The primary subject(s) of a practice are those that are most directly affected by them, or the ones that are understood as the reason for its implementation – for instance, the primary subject of the visa-regime, are those that are in need of a visa to travel to a particular country. The securitising practice or tool sends a message about the nature of the problem and thus also the nature of the threatening subject(s) that it subjects.

Content analysis: prevalence of different categories of irregular migrant

The groups of irregular migrants that this analysis is concerned with – the visa overstayer and the irregular migrant by means of irregular entry – are not often referred to explicitly. Rather, the FRONTEX reports are concerned with “[detected] illegal border crossings” or “[detected] illegal stay”, without further distinction. “Illegal border crossings” thus include both those individuals that are, in fact, not irregular border crossers (i.e. asylum seekers) and those who have no legal ground for entry. Moreover, the term “illegal stay” is routinely linked to asylum seekers whose claim for protection has been rejected, rather than to visa overstayers, which indicates that visa overstaying is not FRONTEX’s main focus here. The analysis of frequency of the references to the different groups in the reports, however, serves as an appropriate starting point for the analysis as it provides an overview of the main subjects identified as “risks” by the FRONTEX agency.

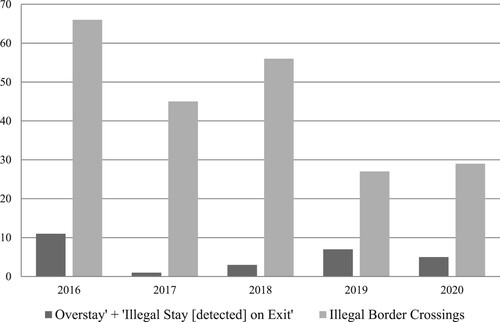

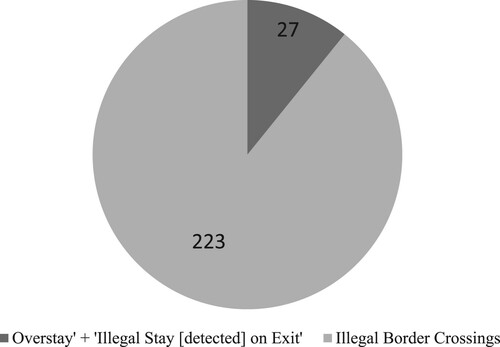

Overall, the number of references to these different means of irregular migration differs greatly, which provides us with the first argument in support of our hypothesis. Throughout all five reports, the word “overstay” is mentioned only eight (8) times. Indeed, even when including the alternative phrase “illegal stay on exit”, i.e. referring to the overstayers that are detected on exit from Schengen, the number of mentions of overstayers constitutes only around a tenth of the number of mentions of “illegal border crossings” (IBCs) (see ).

Figure 1. Total mentions of “overstay” and “illegal border crossings” in FRONTEX’s Risk Analysis reports 2015–2020.

Looking at the number of mentions of the different groups more in detail, we find some differences between reports. In particular, the year 2016 appears to have a relative high mention of both overstayers and IBCs in comparison to the subsequent years. This might, in part, be due to the scope of the report: it included between 5 and 20 additional pages compared to the following years. However, the somewhat declining number of mentions of IBCs might be due to a lessened sense of urgency in regard to irregular arrival across maritime- and land borders after the 2015–2016 crisis.

Although illustrates a stark difference between visa overstaying and irregular border crossing in terms of issue saliency, the frequency of references is poor ground for analysis in and of itself. Rather, the reader should consider this an initial observation, which in the following part is analysed more closely.

Migrants as “threats” in FRONTEX’s risk assessment discourse

Throughout the annual reports, references to “irregular migrants by means of illegal entry” are prevalent and identified as the main part of “risks” to be managed. Indeed, the risk reports describe in rigorous detail every route along which IBCs occur, even when the activity has declined on it. The words “migratory pressure” or simply “pressure” are frequently used to describe unwanted movements of peopleFootnote4 along these routes, which place the EU in the role of the one being pressured. Contributing further to the framing of irregular immigration as a threat to European security, the tracking of irregular border crossings is called “surveillance” – something often associated with military or intelligence operations. The most flagrant description of the situation’s exceptionalism is given in the report published in 2016, when the report compared the situation at the border to that during World War II (FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 14). This construction of the situation at the external border as something out of the ordinary is, however, repeated in every report. While irregular cross-border movements are portrayed as exceptional, there is a simultaneous underlying assumption that the threats of “migratory pressure” are constant. An example of this is found in the most recent report where the director of FRONTEX is quoted saying: “Events at the Greek border highlight the fact that we must remain vigilant” (Citation2020b, p. 7). This is an example of the duality of exceptionalism and constancy that have been noted in previous works on the securitisation of migration (Huysmans Citation2000, e.g. Andersson Citation2016).

The so-called illegal (irregular) border crossers are rarely constituted as a group in its own right in the risk analysis reports. More often, irregular migrants are grouped together with asylum seekers, as their means of arrival rather than their legal right to access Schengen territory are in focus. An asylum seeker, whose claim for protection has not been rejected, is not to be considered an irregular migrant by the EU common standard, but FRONTEX routinely uses the word “illegal border-crossing” for asylum seekers that do not arrive in Schengen at a border crossing point. Asylum seekers are thus systematically included in the definition of “migrants by means of illegal entry”.

This assemblage of different migrants makes for a great securitising subject, since it contains both the “threat” that the “illegal migrants” constitute (to, for instance, internal security) and the “threat” that asylum seekers constitute (to, for instance, welfare systems), as well as the “threats” originating from the group itself on the routes in or to Europe, on the external border or in camps. Many of the threats that the “potential migrants” constitute are presented as a consequence of the sheer numbers – as “migratory pressure” on member states (FRONTEX Citation2019, p. 6), riots at borders (FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 45), or as puppets in a geopolitical game: the 2020 report states that “[a]mong the challenges foreseen by Frontex [along the external border] are […] migrants organising themselves or being used to challenge border regimes” (FRONTEX Citation2020b, p. 7 our emphasis). This does not, then, refer to irregular migrants specifically, but rather to migrants by means of irregular entry in general and constitutes these as a possible threat of violence. However, the presence of the “illegal” or “illegitimate” migrant in this “mixed flow” of the “asylum-seeker-cum-illegal-migrant” group is considered a particularly threatening element:

Distinguish[ing] legitimate asylum seekers who arrive at the external border with no papers from individuals posing a security threat and economic migrants attempting to abuse the system by claiming a false nationality [is a particularly challenging task]. (FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 5)

FRONTEX’s discourse also takes on a strong element of criminalisation of the act of migration. Using the word illegal in relation to irregular border crossings does in itself designate the activities by these groups as criminal activities. The strategies by which these border crossings occur are, additionally, constantly referred to as modus operandi, again alluding to criminal activities (FRONTEX Citation2018, p. 8). Furthermore, in relation to the smuggler, or facilitator, the migrant by “illegal border crossing” is constructed both as its victim and its partner in crime. On the one hand, the migrant is to be saved from the smuggler:

Smugglers are becoming more and more aggressive and ruthless to increase their profit, forcing migrants to board already overcrowded boats. […] Such behaviour led to lives being lost in the Aegean Sea, including that of a three year old boy near Bodrum, Turkey. (FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 18)

In contrast, migration through visa overstaying is only rarely mentioned in the risk reports. There are risks identified in relation to “regular entry”, but these are mainly focused on the smuggling of people, drugs or weapons, rather than people overstaying their visas. Irregular migration by means of visa overstay is not explicitly framed as a threat. The “risk of overstaying” is mainly seen as a practical problem that increases the burden on border officials (FRONTEX Citation2019, p. 9), or that might interfere with the convenience of “bona fide travellers” (FRONTEX Citation2018, p. 9).

If staying illegally in the Schengen area is explicitly mentioned in FRONTEX’s reports, it is not because of visa overstay, but in relation to asylum seekers whose claims for asylum has been rejected. Very few visa overstayers are detected on the Schengen territory, and these are almost exclusively detected on exit. The number of “[detected] illegal stays on exit” is included in every report, but these numbers are not connected to risk-laden words. The fact that the overstayers are “detected” when leaving the Schengen territory is noted: “in most cases, following a detection on exit, the person continues to travel and is recorded in SiS” (FRONTEX Citation2016, 27), but there is no sense of urgency in dealing with this phenomena. As was shown in the frequency analysis above, the reported visa overstayers are comparatively few, and together with the matter-of-fact tone discussing it in the report, the significance of visa overstay seems to be of marginal interest in FRONTEX’s evaluation of risk.

The visual aspects of the reports give further weight to the analysis that visa overstayers are not portrayed as great risks in FRONTEX risk reports. When situations involving migration are portrayed, these are exclusively pictures from FRONTEX “hotspots” on the borders, of overcrowding of migrants or from rescue operations, often of the well-known images of migrants in small boats in the middle of the sea (see e.g. FRONTEX Citation2016, pp. 7, 12–13, 47, Citation2017, pp. 1, 15, 33).Footnote8 There are very few pictures from air borders, and those that exist portray technology rather than humans (FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 23, Citation2018, p. 23). Furthermore, in many pictures the reader meets uniformed FRONTEX officials’ mid-operation with hi-tech gadgets and vehicles, or in camouflage clothing conducting surveillance at the vast borders (e.g. FRONTEX Citation2017, pp. 44–45, Citation2018, p. 6, Citation2019, p. 6, Citation2020b, p. 15,26). Many of the pictures have a militaristic rationale to them, involving action and invoking associations of protection against security threats. This imagery reflects a development towards the militarisation of border control that has been observed globally (Jones and Johnson Citation2016), as well as in the EU (Schwell Citation2010), which also serves to symbolically represent the EU as being “in control” of its borders. In the context of FRONTEX’s risk analyses, the images of militarised policing of border control reinforce the idea that irregular migration across the border is particularly risky, and leaves visa overstays out of the visual representation of migration.

Similarly, the visual representation of data of IBCs, referred to as “migrant flows”, almost resembles maps of military offensives or similar threatening movements, usually represented by fat arrows hovering around the borders, as threatening to penetrate them with force (e.g. FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 16, Citation2017, p. 18, Citation2019, p. 16, Citation2020b, p. 22). The result of FRONTEX’s mapping of irregular migration, as recently investigated in detail by van Houtum and Bueno Lacy (Citation2020, p. 213), is that “the viewer is ultimately exposed to a visual composition in which a threatening invasion of migrants is taking over a defenceless EU”. While the visual elements of these representations of migrant flows have become the “predominant template” (van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2020, p. 198), their appearances are still striking in contrast to other maps in the FRONTEX reports showing, for instance, number of “illegal stayers”, which are presented in a much more neutral and non-threatening fashion.

Visa overstayers: a new category of “risk”?

Although the visa overstayers are not routinely being constructed as security threats in the FRONTEX Risk Analyses, particularly not at a level on par with other irregular migrants, or asylum seekers, a slight shift can be detected in the most recent reports (FRONTEX Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020b), as the “regular passage flow” is raised as an issue that need to be monitored. In the 2020 report, there is a reference to the high numbers of “legal travellers”, and although this is not expressed as a negative development, it is noted that these travellers need to be managed to “filter out those who might pose a risk” (FRONTEX Citation2020b, p. 17). Here, visa liberalisations seem for the first time to be identified as “risks” in some particular ways. Firstly, the visa liberalisations are connected to an increase in asylum-claims (FRONTEX Citation2020b, p. 30).Footnote9 These are, however, not constructed as a major issue, as any country in question for a visa liberalisation agreement must be designated as “safe”. Asylum applicants arriving from these countries will, therefore, have a high number of their asylum claims rejected. Secondly, the 2020 report makes an explicit connection between visa liberalisation agreements and the risk for overstaying:

Although most visa-free nationals enter legally, some overstay their permission to stay and then become irregular, a phenomenon that appeared to be particularly common among nationals from Ukraine, Russia, Moldova, Serbia and North Macedonia. (FRONTEX Citation2020b, p. 30)

FRONTEX’s securitising practises

The activities and practises of FRONTEX with the aim of “curbing” irregular entry has been recognised as securitising practises by previous research (Léonard Citation2010). For instance, FRONTEX-supported encampment sites in Greece can be considered such a securitising practice, and the use of state-of-the-art technologies in the surveillance of the borders another one (e.g. Bigo Citation2014). In their risk assessments, FRONTEX refers to the cooperation with third parties like the Libyan coast guard or the Moroccan authorities as some of the most important practices by which the agency’s goals can be met (e.g. FRONTEX Citation2019, p. 38).

The use of such practices signals that these migrants constitute such a threat that extra-ordinary measures need to be taken to stop them. With the new regulation, concerning the mandate of FRONTEX ratified by the European Council in December 2019, additional practices with the same underlying rationale can be added to the list. Notably, the agency is to establish a uniformed European Border and Coast Guard with a standing corps of 10 000 (FRONTEX Citation2020b, p. 5). This rather remarkable development of FRONTEX’s capacity clearly emphasises that EU leaders – divided an almost all other matters in regard to common migration and asylum reforms – are prioritising the “security” of the external borders. The new regulations further extend FRONTEX’s mandate to conduct operations in third countries outside of the EU and Schengen area, to pre-emptively reduce migration, further increasing the scope of its operational capacities and a practice that is, indeed, out of the ordinary. In sum, the developments of FRONTEX’s capacity and mandate to control and regulate the external border focuses on reducing irregular border crossings, accentuates the highly securitised state of this category of migrants.

As we argued in the introduction, a visa-regime can act as a securitising tool in itself. However, using the definition of a securitising practice we set out in the methodology section, the “practice of demanding visas” cannot immediately be identified as a securitising practice, since it cannot be considered out of the ordinary in the realm of migration management. Other practices in the realm of visa regimes, on the other hand, could. For instance, the (fairly) recent use of biometric data in travel documents, and the demand of biometric passports for visa free travellers to the Schengen area, can be considered securitisation practices. These practices restrict the visa-free access to holders of such passports, but, more importantly, also collect a great amount of personal and biometric data. The collection of such data is part of a digitalisation of border control that raise questions about privacy (Lehtonen and Aalto Citation2017) and contribute to the construction of border crossers as potential threats (Amoore Citation2006, Topak et al. Citation2015, Longo Citation2018).

Recent developments

As already discussed, the lack of knowledge about who overstays their visa is in itself an indication of the absence of securitisation of visa overstaying. It may, furthermore, be one of the most crucial reasons for the fact that visa overstay is a “hidden” phenomenon that does not cause a lot of debate. However, there are several new measures underway in regard to the control of “regular” travellers to Schengen that interestingly represent a very radical shift in the management of “legal” mobility – that is the adapted resolution regarding the yet to be implemented EU Entry/Exit system (EES) and the decision regarding the, also forthcoming, European Travel Information and Authorization System (European Commission Citation2019). The EES is supposed to collect all data on both entry and exit of all non-EU nationals who are visa-exempt or holders of a short-term visa, with the explicit aim to “facilitate border crossing of bona fide travellers and to identify over-stayers” (European Commission Citation2019, p. 2, emphasis added). This is a new surveillance tactic that might radically change the risks of overstaying (for the individual traveller) and, in turn, might act as a securitisation instrument that subjects visa overstay to the same security logic as other types of irregular migration.

Furthermore, and equally interesting for our argument, the European Travel Information and Authorization System (ETIAS) targets visa-exempt non-EU nationals specifically, and aims to “ensure that possible security and irregular migration concerns are identified” (European Commission Citation2019, p. 3) before the individuals can conduct short-term stay in Schengen. This represents a de facto securitisation of visa-exempt travellers, and one that is applied universally, since they will need an approval from the ETIAS before travelling to the Schengen area. In essence, the forthcoming introduction of the system might represent a re-securitisation of the de-securitisation that visa liberalisation constitutes. The introduction of these new information systems will furthermore make FRONTEX and national border guard authorities, alongside EUROPOL, the actors with the widest access to personal information in the Schengen area, a swift development that has taken place only over the course of a few years. This development effectively constitutes a securitising practice, but it also opens up a new space for securitised discourse – as monitoring of visa travellers becomes more thorough, they can be further divided into “safe” and “risky” subjects, meaning they are more likely to become the subject of securitising discourse.

However, there is still an important point to be made in regard to the objects and subjects of the securitisation practices of FRONTEX. The forthcoming information systems are presented as both securing the EU and its citizens from threats, but it is also described as a way to ensure smooth travel for other, “regular” travellers. Thus, the referent object of, perhaps not the security threat, but the “disturbance” of thorough checks at the border, is the bona fide traveller that is expected to benefit from these developments as well. On the contrary, the practices subjecting “irregular migrants by means of illegal entry” are not presented as a way to ensure safe asylum for those in need. Indeed, the “solutions” to the problems of “illegal border crossings” serve to prevent the refugee from seeking asylum as much as it prevents the irregular migrant from reaching Europe. This is not particularly shocking considering that the question of asylum has been highly politicised in almost all member states of the union, but nevertheless of monumental importance if European policies in regard to migration and mobility and the power structures that underlies them are to be understood.

Conclusion

We began this article noting the apparent paradox that visa liberalisation is used by the EU as incentives for third countries in agreements aiming to reduce the number of migrants arriving to the EU, although visa overstayers constitute a large share of irregular migrants. We hypothesised that this seemingly contradictory policy might be a result of visa overstaying being left out of the general securitisation of migration in the EU. Overall, the present analysis of FRONTEX’s risk assessments shows that visa overstayers have not been securitised to the same extent as other irregular migrants. Our analysis showed that visa overstay has systematically been left out of the securitising discussion regarding irregular migrants in the risk assessments of FRONTEX, which has had a clear focus on the “irregular migrants by means of irregular entry” over other groups of irregular migrants. This asymmetric securitisation of different groups of migrants as threats to security can be seen as a constitutive factor in the use of visa liberalisation agreements as incentives for cooperation on border and migration management.

Although we find that visa overstaying is not seen as a risk on par with irregular border crossings, potential risks associated with “regular” travellers and visa holders, who might overstay, were included in the more recent years of risk assessment analyses. Paired with the recent EU policies underway, aimed at “filtering” and “screening” regular entry arrivals more thoroughly, these findings challenge the observed asymmetry in the (near) future. The collection of increasingly detailed information on people that enjoy visa-free travel to the EU can be seen as a securitising move. The effects of these new policies might, by producing more information about overstaying in the EU, serve to include visa overstayers in the general construction of migrants as “risky” subjects. Increased capacity and resources to identify “high-risk” individuals might, however, target those who are construed as threats asymmetrically, e.g. people of particular nationalities, with limited economic means, or with specific travel patterns. In that way, the “smart border”-package risks exacerbating the disparities that already exist in the international system with regard to mobility. Further scholarly attention should be afforded might these developments of EU border policies to assess their impact on the securitisation of different groups of migrants.

While migrants are often treated as part of a uniform category in the securitisation literature, this article has shown that different groups of migrants are asymmetrically securitised by EU border policies and the discourses deployed in relation to them. This asymmetrical securitisation is, furthermore, contextually dependent and subject to temporal and spatial variation. Future studies of securitisation of migration should incorporate a multi-facetted discussion on the variation that exists in relation to the heterogeneous category of “migrants” as well as the regimes that are designed to govern them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Frida Hansen

Frida Hansen, BSc, is a graduate of political science at Uppsala University.

Johanna Pettersson

Johanna Pettersson, PhD, is a researcher at the Department of Government, Uppsala University. Her research focuses on questions of sovereignty and the politics of borders.

Notes

1 For a recent example, see for instance the Mobility Partnership signed between EU and Belarus in January 2020 (European Commission Citation2020c), or the agreement with Ukraine signed in 2017 (Council of the European Union Citation2017).

2 We understand migrants as being irregularised and/or illegalised by the practices and policies that they become subjected to, not as categories of belonging/personhood (cf. Scheel Citation2018). For the purpose of this article, we use the term “irregular” migrant as designated to categories of migrants in the FRONTEX reports. We use the term “illegal migrant” only in direct reference to FRONTEX terminology.

3 For a thorough discussion and overview of available databases on irregular migration and irregular migrants at the EU level, see Vespe et al. (Citation2017).

4 For example in phrases such as “In 2018, the number of detections of illegal border-crossings reached its lowest level in five years, but migratory pressure remained relatively high at the EU’s external borders” (FRONTEX Citation2019, p. 6).

5 “[The terrorist attacks in Paris] was a dreadful reminder that border management also has an important security component” (FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 5).

6 For instance, the only “Migrant Testimony” included in the 2016 Risk Analysis Report is by an unnamed migrant and reads: “Some of my friends went to Europe and when they came back, they had money and bought cars for their family. One day I thought, ‘I am the same as these people, I should do the same’” (FRONTEX Citation2016, p. 20).

7 This corresponds to the criminalisation of immigration law that Stumpf (Citation2006) labelled “crimmigration” and which has been discussed in relation to both EU legislation and practice (van der Woude and van Berlo Citation2015, van der Woude and van der Leun Citation2017, Fekete Citation2018).

8 Following the adoption of the GDPR regulations in 2018, migrants are no longer depicted in the reports except for with blurred faces or in other unidentifiable positions.

9 For example “slightly more than a quarter of all asylum applications were submitted by nationals from visa exempt countries” (FRONTEX Citation2020b, p. 30).

References

- Adepoju, A., van Noorloos, F., and Zoomers, A., 2010. Europe’s migration agreements with migrant-sending countries in the global south: a critical review. International migration, 48 (3), 42–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00529.x.

- Alkopher, T.D. and Blanc, E., 2017. Schengen area shaken: the impact of immigration-related threat perceptions on the European security community. Journal of international relations and development, 20 (3), 511–542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-016-0005-9.

- Amoore, L., 2006. Biometric borders: governing mobilities in the war on terror. Political geography, 25 (3), 336–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.02.001.

- Andersson, R., 2016. Europe’s failed “fight” against irregular migration: ethnographic notes on a counterproductive industry. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 42 (7), 1055–1075. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1139446.

- Andrijasevic, R. and Walters, W., 2010. The international organization for migration and the international government of borders. Environment and planning D: society and space, 28 (6), 977–999. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d1509.

- Balzacq, T., 2008. The policy tools of securitization: information exchange, EU foreign and interior policies. Journal of common market studies, 46 (1), 75–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00768.x.

- Basaran, T., 2010. Security, law and borders: at the limits of liberties [online]. Routledge.

- Bigo, D., 2002. Security and immigration: toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives, 27 (Suppl. 1), 63–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/03043754020270s105.

- Bigo, D., 2014. The (in)securitization practices of the three universes of EU border control: military/navy – border guards/police – database analysts. Security dialogue, 45 (3), 209–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614530459.

- Buzan, B., et al., 1998. Security: a new framework for analysis. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Casas-Cortes, M., Cobarrubias, S., and Pickles, J., 2016. “Good neighbours make good fences”: seahorse operations, border externalization and extra-territoriality. European urban and regional studies, 23 (3), 231–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776414541136.

- Ceyhan, A. and Tsoukala, A., 2002. The securitization of migration in western societies: ambivalent discourses and policies. Alternatives, 27 (Suppl. 1), 21–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/03043754020270s103.

- Council of the European Union. 2017. Visas: council adopts regulation on visa liberalisation for Ukrainian citizens. Available from: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/05/11/visa-liberalisation-ukraine/ [Accessed 23 December 2020].

- Czaika, M. and Trauner, F., 2017. EU visa policy: decision-making dynamics and effects on migratory processes. In: A. Ripoll Servent and F. Trauner, eds. The Routledge handbook of justice and home affairs research. London: Routledge, 110–123.

- Delcour, L., 2018. The EU’s visa liberalisation policy: what kind of transformative power in neighbouring regions? In: The Routledge handbook of the politics of migration in Europe [Handbooks Online]. Routledge, 410–419.

- El Qadim, N., 2018. The symbolic meaning of international mobility: EU-Morocco negotiations on visa facilitation. Migration studies, 6 (2), 279–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnx048.

- European Commission. 2019. EU information systems. Security and Borders. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-security/20190205_security-union-eu-information-systems_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2020a. Definition of irregular migrant. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/irregular-migration-return-policy_en [Accessed 10 May 2020].

- European Commission. 2020b. Irregular migration and return policy. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/irregular-migration-return-policy_en [Accessed 10 May 2020].

- European Commission. 2020c. Visa facilitation and readmission: the European Union and Belarus sign agreements. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/news_corner/news/visa-facilitation-and-readmission-european-union-and-belarus-sign-agreements_en [Accessed 23 December 2020].

- Fekete, L., 2018. Migrants, borders and the criminalisation of solidarity in the EU. Race and class, 59 (4), 65–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396818756793.

- Fine, S., 2018. Liaisons, labelling and laws: international organization for migration bordercratic interventions in Turkey. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 44 (10), 1743–1755. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1354073.

- Frelick, B., Kysel, I.M., and Podkul, J., 2016. The impact of externalization of migration controls on the rights of asylum seekers and other migrants. Journal on migration and human security, 4 (4), 190–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241600400402.

- FRONTEX, 2016. Risk analysis for 2016. Warsaw: FRONTEX. doi:https://doi.org/10.2819/416783.

- FRONTEX, 2017. Risk analysis for 2017. Warsaw: FRONTEX. doi:https://doi.org/10.2819/250349.

- FRONTEX, 2018. Risk analysis for 2018. Warsaw: European Border and Coast Guard Agency. doi:https://doi.org/10.2819/460626.

- FRONTEX, 2019. Risk analysis for 2019. Warsaw: FRONTEX. doi:https://doi.org/10.2819/86682.

- FRONTEX, 2020a. Key facts [online] Available from: https://frontex.europa.eu/about-frontex/faq/key-facts/ [Accessed 2021 2 July 2021].

- FRONTEX, 2020b. Risk analysis for 2020. Warsaw: FRONTEX. doi:https://doi.org/10.2819/450005.

- Gülzau, F., Mau, S., and Zaun, N., 2016. Regional mobility spaces? Visa waiver policies and regional integration. International migration, 54 (6), 164–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12286.

- Huysmans, J., 2000. The European Union and the securitization of migration. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 38 (5), 751–777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00263.

- Infantino, F., 2016. State-bound visa policies and Europeanized practices. Comparing EU visa policy implementation in Morocco. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 31 (2), 171–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1174603.

- Jansen, Y., Celikates, R., and De Bloois, J., 2014. The irregularization of migration in contemporary Europe: detention, deportation, drowning. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Jones, R. and Johnson, C., 2016. Border militarisation and the re-articulation of sovereignty. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41 (2), 187–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12115.

- Kelly, C.B., 1977. Counting the uncountable: estimates of undocumented aliens in the United States. Population and development review, 3 (4), 473. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1971686.

- Krotký, J. and Kaniok, P., 2020. Who says what: members of the European parliament and irregular migration in the parliamentary debates. European security, 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1842362.

- Laube, L., 2019. The relational dimension of externalizing border control: selective visa policies in migration and border diplomacy. Comparative migration studies, 7, 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0130-x.

- Lavenex, S., 2006. Shifting up and out: the foreign policy of European immigration control. West European politics, 29 (2), 329–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380500512684.

- Lazaridis, G. and Wadia, K., 2015. The securitisation of migration in the EU: debates since 9/11. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lehtonen, P. and Aalto, P., 2017. Smart and secure borders through automated border control systems in the EU? The views of political stakeholders in the member states. European security, 26 (2), 207–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2016.1276057.

- Léonard, S., 2010. EU border security and migration into the European Union: FRONTEX and securitisation through practices. European security, 19 (2), 231–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2010.526937.

- Longo, M., 2018. The politics of borders: sovereignty, security, and the citizen after 9/11. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mau, S., et al., 2015. The global mobility divide: how visa policies have evolved over time. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 41 (8), 1192–1213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1005007.

- Neal, A.W., 2009. Securitization and risk at the EU border: the origins of FRONTEX. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 47 (2), 333–356.

- Scheel, S., 2018. Real fake? appropriating mobility via Schengen visa in the context of biometric border controls. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 44 (16), 2747–2763. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1401513.

- Schwell, A., 2010. The iron curtain revisited: the “Austrian way” of policing the internal Schengen border. European security, 19 (2), 317–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2010.531706.

- Simmons, B.A., 2019. Border rules. International studies review, 21 (2), 256–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viz013.

- Sperling, J. and Webber, M., 2019. The European Union: security governance and collective securitisation. West European politics, 42 (2), 228–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1510193.

- Stumpf, J.P., 2006. The crimmigration crisis: immigrants, crime, and sovereign power. American University law review, 56 (367), 1689–1699.

- Topak, Ö.E., et al., 2015. From smart borders to perimeter security: the expansion of digital surveillance at the Canadian borders. Geopolitics, 20 (4), 880–899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2015.1085024.

- van der Woude, M.A.H. and van Berlo, P., 2015. Crimmigration at the internal borders of Europe? Examining the Schengen governance package. Utrecht law review, 11 (1), 61–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.18352/ulr.312.

- van der Woude, M. and van der Leun, J., 2017. Crimmigration checks in the internal border areas of the EU: finding the discretion that matters. European journal of criminology, 14 (1), 27–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370816640139.

- van Houtum, H. and Bueno Lacy, R., 2020. The migration map trap. On the invasion arrows in the cartography of migration. Mobilities, 15 (2), 196–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1676031.

- Van Munster, R., 2009. Securitizing immigration: the politics of risk in the EU [online]. Palgrave Macmilllan UK.

- Vespe, M., Natale, F., and Pappalardo, L., 2017. Datasets on irregular migration and irregular migrants in the European Union. Migration policy practice, VII (2), 26–33. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/ [Accessed 26 February 2021].

- Walker, M., 2018. The other U.S. border? Techno-cultural-rationalities and fortification in southern Mexico. Environment and planning A, 50 (5), 948–968. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18763816.

- Yuval-Davis, N., Wemyss, G., and Cassidy, K., 2019. Bordering. Cambridge, UK: Polity.