ABSTRACT

International organisations (IOs) have increasingly resorted to private military and security companies (PMSCs) as providers of armed protection, training, intelligence, and logistics. In this article, we argue that IOs, seeking to reconcile conflicting international norms and member states’ growing unwillingness to provide the manpower required for effective crisis management, have decoupled their official policy on and actual use of PMSCs, thereby engaging in organised hypocrisy. Due to its stricter interpretation of norms like the state monopoly of violence, the United Nations (UN) has showcased a more glaring gap between talk and action than the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which display a more pragmatic, but not entirely consistent, approach to the use of PMSCs. By examining the decoupling between UN, EU, and NATO official contractor support doctrines and operational records, this article advances the debate on both security privatisation and organised hypocrisy.

1. Introduction

International organisations (IOs) conducting crisis management operations ranging from state-building to border monitoring have increasingly resorted to private military and security companies (PMSCs). Usually defined as commercial providers of services traditionally performed by state armed forces and law enforcement personnel, including “armed guarding and protection of persons and objects … maintenance and operation of weapons systems; prisoner detention; and advice to or training of local forces and security personnel” (ICRC Citation2009, Krahmann Citation2016, Tkach and Phillips Citation2020), PMSCs have been extensively used by the European Union (EU), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the United Nations (UN) alike. In 2012 already, the UN had 52 commercial security contracts and employed over 5000 private guards (Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions Citation2012). PMSCs have also been employed in around half of the EU Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions (see ), while NATO directly or indirectly outsourced over 90% of its logistics (Berghuizen Citation2018).

Table 1. Gaps between talk and action on the use of PMSCs.

This tendency to privatise security and support not only carries relevant policy implications, but is also puzzling because it is often inconsistent with IOs’ internal policy and doctrine. For instance, the UN and the EU have resorted to contractors on a systematic basis even if their official policy restricts the use of PMSCs to “exceptional circumstances” (UNDSS Citation2012a, Citation2012b) or stresses the use of armed contractors “should be limited” (Council of the European Union Citation2014, p. 31), while NATO extensively outsourced its logistics in Afghanistan despite its commitment to minimising contractors’ presence in combat-intensive environments (NATO Citation2007, Citation2012).

We explain the mismatch between IOs’ official policy and the actual use of PMSCs as a form of organised hypocrisy. Although rarely used to explain the use of PMSCs by IOs, the argument that complex organisations tend to decouple talk and action to reconcile inconsistent norms and interests is hardly surprising. Our comparative analysis, however, adds to the existing debate by identifying different degrees of hypocrisy associated with the use of PMSCs. By doing so, we shed light on the reasons underlying the decoupling between rhetoric and action in IOs’ contractor support policies, thereby contributing to the study of both organised hypocrisy and security privatisation.

Existing private security scholarship has extensively examined the resort to PMSCs by states (Avant Citation2005, Dunigan Citation2012, Leander Citation2013). The use of PMSCs by international organisations (IOs), by contrast, has been investigated more sparsely. Most research concentrates on the privatisation of UN peacekeeping (Østensen Citation2011, Spearin Citation2011, Bures and Cusumano Citation2021, Tkach and Phillips Citation2020). Fewer studies examine contractor support to NATO (Krahmann Citation2016, Cusumano Citation2017) and EU missions (Krahmann and Friesendorf Citation2011, Giumelli and Cusumano Citation2014). Moreover, all the research on IOs’ use of PMSCs consists of single case studies focusing solely on one organisation, thereby lacking a comparative dimension. By providing a simultaneous, cross-case comparison of contractor support to UN, EU, and NATO crisis management operations, our article seeks to fill this gap.

PMSCs have been increasingly used by IOs’ member states like the US to support and sometimes even replace the personnel dispatched to stabilisation, state-building, border control, and peacekeeping missions (Dunigan Citation2012, Giumelli and Cusumano Citation2014). In this article, however, we exclusively focus on the direct outsourcing of security and support by IOs’ agencies. Over the last decades, IOs have simultaneously experienced increasing pressure to intervene in conflict and unrest scenarios and a growing inability to obtain the personnel required for effective crisis management from their member states. In response to these pressures and constraints, IOs have purposively relied on PMSCs as sources of otherwise unavailable manpower. Nevertheless, as noted by institutionalist IR scholars, IOs’ behaviour is not only driven by logics of expected consequences, but also restricted by specific logics of appropriateness (March and Olsen Citation1989, Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004). To preserve their legitimacy, IOs need to comply with prevailing societal norms. The tension between the need to fill manpower gaps through PMSCs and the normative restrictions surrounding their use, we argue, is conducive to organised hypocrisy. Consequently, IOs are likely to decouple their talk and action, displaying a mismatch between the increasing use of contractors for crisis management operations and official policies restricting the use of PMSCs.

IOs’ attachment to and interpretation of prevailing norms, however, is not identical. Due to the role played by mercenaries in decolonisation conflicts, the UN has developed a stricter interpretation of the anti-mercenary norm and the obligation to uphold a monopoly of violence (Bures and Meyer Citation2019, Bures and Cusumano Citation2021). By contrast, the EU and NATO have developed a more pragmatic approach towards private providers of security and military support and have been increasingly permeated by neoliberal norms that encourage commercial actors’ involvement in many tasks previously performed by state authorities, including military operations. As a result, the extent to which these IOs have engaged in organised hypocrisy on the use of PMSCS differs. While the UN displays a complete decoupling between talk and action, the EU and NATO showcase smaller but nevertheless significant gaps between doctrinal prescriptions on contractor support and the use of PMSCs in crisis management operations.

The UN, NATO, and the EU differ in many important aspects, including the number of member states, the size of their bureaucracy, their budget, and their mandate. However, these IOs are comparable in one important respect: they have all conducted various demanding peacekeeping, stability, and crisis management operations in conflict and post-conflict environments ranging from Bosnia to Afghanistan, Mali, and Libya. These multilateral operations have comprised member states’ soldiers, police officers, development and diplomatic personnel, as well as increasing numbers of contractors. A structured, focused comparison (George and Bennett Citation2005) of these three cases, therefore, provides crucial insights into the increasing use of PMSCs. To simultaneously examine IOs’ talk and action, we combine different sources and methods, including a qualitative content analysis of unclassified official documents, mining of available quantitative data, semi-structured interviews with IO and national officials conducted between 2014 and today, as well as media reports and academic literature. As large providers of crisis management, the UN, NATO, and the EU are cases of intrinsic importance in the study of security privatisation. Moreover, all these IOs have increasingly privatised security and support in the previous decade and are set to become increasingly dependent on PMSCs for future crisis management operations. Furthermore, the UN, NATO, and the EU have all served as vehicles for the diffusion of several norms, ranging from democracy to the responsibility to protect (R2P) (Tallberg Citation2020). Hence, the organised hypocrisy surrounding the use of PMSCs carries timely theoretical and policy implications for the study of European security, affecting both IOs’ effectiveness as providers of crisis management and their credibility as norm entrepreneurs.

This article is divided as follows. The next section outlines our theoretical framework, introducing the concept of organised hypocrisy. Sections three to five present our three case studies, focusing on the UN, the EU, and NATO, respectively. The analysis and ensuing conclusions discuss our results, examine their theoretical ad policy implications, and sketch some future research avenues.

2. Theoretical framework: hypocrisy in international organisations

Like all other organisations, IOs need to draw resources from their external environment to survive and thrive. Rationalist approaches to organisational behaviour like Resource Dependence Theory have identified the effort to ensure access to scarce material resources as a vital consideration for complex organisations, including IOs like the EU and NATO (Petrov et al. Citation2019).

Sociological institutionalism, by contrast, stresses that organisations’ survival hinges primarily on a critical immaterial resource: legitimacy. To preserve their legitimacy, organisations must conform to societal logics of appropriateness and abide by prevailing norms, even of those norms are sometimes inconsistent with one another (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977, Di Maggio and Powell Citation1983, March and Olsen Citation1989). Constructivist studies of IOs have built on sociological institutionalist premises, extensively examining both how norms shape IOs’ behaviour and how IOs contribute to international norms’ diffusion (Barnett and Coleman Citation2005, Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004, Tallberg et al. Citation2020).

Drawing on both rationalist and institutionalist approaches, we explain the decoupling of IOs’ talk and action on PMSCs as an attempt to balance the need for material and symbolic resources, simultaneously upholding logics of consequences and logics of appropriateness. IOs have been increasingly tasked with conducting crisis management operations. Haunted by the failure to act upon genocide in Bosnia and Rwanda, the UN has engaged in increasingly complex peacekeeping operations, engaging in demobilisation and disarmament, capacity-building, and civilian protection (Williams and Bellamy Citation2021). Facing the decision of “going out of area or out of business” after the Cold War, NATO has expanded its focus from Europe’s territorial defence to stabilisation missions in the Balkans and Afghanistan (Auerswald and Saideman Citation2014). Tasked with the expectation to act as a “normative power”, the EU has launched many civilian and military missions within the framework of its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) (Ejdus Citation2017).

However, member states’ willingness to provide these IOs with the manpower required to accomplish such tasks has lagged behind. Even when supportive of IOs’ missions, member states are often reluctant to deploy boots on the ground for crisis management operations. Military manpower cuts, political parties’ growing opposition to unpopular missions, parliamentary constraints over the deployment of troops abroad, and the political costs attached to public casualty aversion have all restrained governments’ willingness to provide IOs with the personnel required for effective crisis management. Consequently, UN peacekeeping operations have been primarily delegated to militaries from the global South (Williams and Bellamy Citation2021). EU missions often have remained “severely understaffed” years after their launch (Ejdus Citation2017, p. 472), while member states’ contribution to NATO operations has not only been insufficient in number, but also limited by national caveats, tights rules of engagement, and widespread casualty aversion (Auerswald and Saideman Citation2014, Rynning Citation2013).

The existing literature has identified member states’ unwillingness to provide the personnel needed for effective crisis management as one of the main causes of IOs’ capabilities-expectations gap (Hill Citation1993). The proliferation of PMSCs has increasingly enabled IOs to bridge this gap by tapping into the market for logistics and armed security. Although not devoid of risks, the use of PMSCs provides IOs with the possibility to partly bypass member states’ unwillingness to provide the manpower required for effective crisis management. By helping circumvent the constraints attached to force generation processes, contractor support helps bridge the gap between capabilities and expectations that often plagues IOs’ missions. Hence, IOs resort to PMSCs as a source of otherwise unavailable manpower can be seen as following a logic of consequences.

The use of PMSCs as a force multiplier, however, is enabled or inhibited by different logics of appropriateness. While increasingly encouraged by the spread of neoliberalism and the subsequent belief in the effectiveness and efficiency of commercial actors, the privatisation of security and military support is inhibited by two distinct but connected norms: the expectation that public actors should uphold a monopoly of violence and the prohibition to use mercenaries or commercial providers of coercion at large (Bures and Meyer Citation2019, Bures and Cusumano Citation2021). While most of today’s PMSCs only provide support and defensive security services, various scholars have argued that their activities do not entirely fall outside the scope of these norms (Percy Citation2007, Panke and Petersohn Citation2012, Leander Citation2013). In conflict and unrest scenarios, moreover, even the commercial provision of services that are not tightly associated with the state monopoly of violence, like logistics, is arguably incompatible with other established norms, such as civilian protection and employers’ duty of care towards their workers. Adherence to these norms should also restrict the deployment of civilian contractors in harm’s way (De Nevers Citation2009, De Guttry et al. Citation2018). Consistent with all these norms, IOs have all established policies tightly restricting the use of PMSCs to specific support tasks, exceptional contingencies, and benign, non-combat environments (NATO Citation2007, UN Citation2012).

Collective actors facing contradictory demands tend to decouple talk and action, rhetorically espousing publicly accepted norms even if these norms are frequently inconsistent with organisations’ actual behaviour. As noted by Nils Brunsson (Citation1989, p. 28), this decoupling is “a fundamental type of behaviour in the political organisation: to talk in a way that satisfies one demand, to decide in a way that satisfies another, and to supply products in a way that satisfies a third”. Consequently, what organisations “say” frequently diverges from what they actually “do”. First described as organised hypocrisy by Brunsson (Citation1989, Citation2007), gaps between rhetoric and action are widespread in political organisations with multiple principals like IOs, including the UN (Lipson Citation2007) and the EU (Hansen and Marsh Citation2015, Cusumano Citation2019).

The tension between the resort to the market to reduce manpower gaps and the need to abide by the abovementioned international norms – we argue – should prompt IOs to engage in organised hypocrisy. To simultaneously obtain otherwise unavailable manpower and signal adherence to expected logics of appropriateness, IOs should increasingly rely on PMSCs as force multipliers, while rhetorically paying lip service to the anti-mercenary, state monopoly of violence and civilian protection norms. Consequently, a gap is likely to emerge between talk and action: crisis management missions will systematically resort to PMSCs as a force multiplier even if IOs’ official policy and doctrine tightly restrict contractors’ use. The extent to which rhetoric and behaviour are decoupled, however, depends on how IOs interpret these norms. Organisations that see themselves as the custodians of states’ sovereignty and self-determination, like the UN, are likely to develop a stricter interpretation of the state monopoly of violence, and should, therefore, display a stronger reluctance to acknowledge their systematic use of PMSCs. By contrast, IOs like NATO and the EU – where the state monopoly of violence is interpreted more narrowly and co-exist with competing norms that encourage commercial actors’ involvement in a wide range of public policies – should showcase a narrower gap between talk and action, more openly acknowledging the use of PMSCS in their official doctrines.

3. Hypocrisy in international organisations

As summarised by , our findings confirm that the UN, NATO, and the EU alike have engaged in some degree of organised hypocrisy, but the gaps between each IO’s talk and action on PMSCs differ significantly.

The remainder of this section examines the use of PMSCs in UN, EU, and NATO crisis management operations in detail.

3.1. The UN and PMSCs

3.1.1. Talk: UN contractor support doctrine

The UN was a prominent anti-mercenary norm entrepreneur throughout the second half of the twentieth century. The General Assembly, in particular, passed more than 100 resolutions labelling mercenaries as “criminals” (UN General Assembly Citation1976), while the Security Council repeatedly condemned states that permit their recruitment (241/1967, 405/1977). Similar statements can be found in numerous reports by the two UN bodies specifically mandated to discuss commercial providers of violence: the UN Special Rapporteur on the use of mercenaries, appointed in 1987, and the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries, which replaced the Rapporteur in 2005. The UN Rapporteur Enrique Ballesteros (Citation1998) identified PMSCs as a “new operational model of mercenarism” threatening peace and state sovereignty. Even if it conceded that “PMSCs are not mercenaries” (A/HRC/15/25/2010, Add.6), the Working Group has continued to stigmatise them as problematic actors that “do not defend common interests and the common good, but rather the private interests of those who hire and pay them” (A/HRC/42/36). Specifically, the Working Group has criticised PMSCs for the use of former child soldiers, abuses against prisoners and migrants, corruption of government officials and even the “promotion of social and political instability” (A/HRC/42/36). The Working Group also stressed that using PMSCs poses “vast and complex challenges” to the UN and may be both “detrimental to the human rights of local populations and harmful to the credibility of the Organization”. Consequently, it recommended that “security functions should remain the primary responsibility of Member States”.

The Secretary General officially acknowledged the UN’s use of private armed guards for the first time in 2011, justifying contractor support as the outcome of the increasing demand for UN action in insecure areas and the lack of protection for UN personnel by host countries or other Member States (UN Secretary General Citation2012, para. 8). Shortly thereafter, the UN Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS) published some guidelines on the use of private security services (UN Department of Safety and Security Citation2012a, p. 1). Both the Secretary General and the UNDSS, however, referred to PMSCs as a last resort. The UNDSS Security Manual explicitly mentions that “[a]rmed security services from a private security company may not be contracted, except on an exceptional basis” (UN Department of Safety and Security Citation2012b, p. 93). Private security providers should only be used “when there is no possible provision of adequate and appropriate armed security from the host Government, alternate member State(s), or internal United Nations system resources” (UN Department of Safety and Security Citation2012a, p. 2). The exceptional nature of private security contracts is iterated seven different times in the Security Manual and the Guidelines attached thereto.

The Working Group has called for reforming UN contractor support policy and forcefully criticised the ambiguity of the “last resort” criterion identified by the UN Guidelines, frequently stretched to cover situations where PMSCS are not necessarily the only solution available, but merely “the most politically expedient option” (A/69/150/2014). As of 2021, however, the Working Group’s talk continues to stand in stark contrast with the practices developed by other parts of the UN system.

3.1.2. Action: UN use of private military and security companies

Although the UN used specialised logistical services already in the 1990s (Bures Citation2005, Østensen Citation2011), widespread outsourcing of security and support started only in the early 2000s. Since then, however, the use of PMSCs has become systematic in most UN agencies, funds, programmes, departments, country teams, and local duty stations. UN agencies have privatised a wide range of activities, including armed and unarmed protection, risk assessment, training, logistical support, base construction, transportation, convoy security, demining, intelligence, and security sector reform. The use of PMSCs has been documented in all types of UN field missions, including humanitarian, political, as well as peacekeeping missions (Bures and Meyer Citation2019, Pingeot Citation2012, Tkach and Phillips Citation2020, Bures and Cusumano Citation2021).

Data on PMSCs’ use have been published only twice by the UN thus far. In December 2012, the annexes of a report by the Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions provided the first concrete information regarding armed contractors. Specifically, the report indicated that 42 PMSCs were under contract with UN missions and operations as of October 2012, employing over 5,000 armed guards, for a total budget of $30,931,122 (Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions Citation2012). Armed PMSCs were primarily used in complex (post-)conflict settings in Africa (15 countries) and the Middle East (3 countries).

The second document with specific data on UN’s PMSCs contracting is the August 2014 report of the UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries (Citation2014). This document specifically listed only 12 peacekeeping missions and one facility of the Department of Field support, claiming that, of the total of 4412 security guards contracted by these 13 entities, only 574 were armed. It also stated that from the $14,015,520 total estimated budget for PMSCs in 2013/2014, approximately $42,125,297 was allocated for “armed services” in just two missions/countries, namely MINUSTAH/Haiti ($5,125,200) and UNAMA/Afghanistan ($8,890,320). The report also contains two case studies on the use of PMSCs in Afghanistan and Somalia. In Afghanistan, the report confirmed that IDG Security (Afghanistan) Limited provided both armed and unarmed Gurkha guards “for internal duties in the UNAMA compound” (UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries Citation2014, para. 52). In addition, various UN agencies and programmes had their own separate security contracts for their respective areas of the same compound. In the case of Somalia, the Working Group observed that “the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) contracted a local company providing several services, including armed escorts, threat and risk assessments, communications, logistics and dispatch services” (UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries Citation2014, para. 60). The report also noted that “several local security providers in Somalia were clan-based militias that operate behind a corporate facade in order to conceal the involvement of individual warlords” (UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries Citation2014, para. 61).

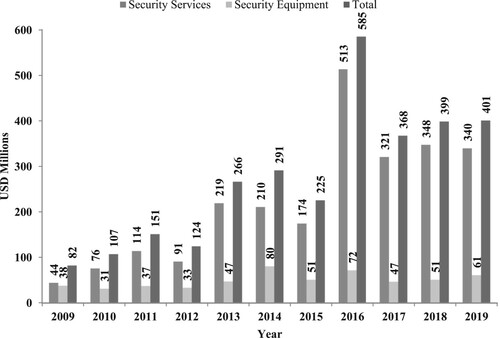

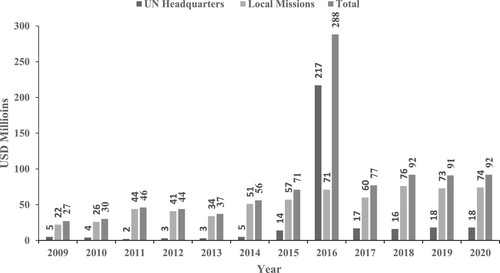

Although available data on PMSCs are of dubious quality due to discrepancies within the reported figures and an apparent lack of understanding of the PMSCs business (Bures and Meyer Citation2019), they clearly illustrate the UN’s growing reliance on contractors. shows an overall 489% increase in the UN’s total expenditures on security services and security equipment contracting. Equally remarkable is the 341% increase in expenditures on security procurement by UN Headquarters and local missions between 2009 and 2020 captured in .

Figure 1. Annual statistical report on UN Procurement for security services and equipment (2009–2019).

Source: Elaboration of annual statistical report on United Nations Procurement from 2009–2020, accessible at https://www.ungm.org/Public/ASR.

Figure 2. UN headquarters and local missions’ procurement of security services and equipment (2007–2020).

Notes: The abrupt increase occurred of 2016 is arguably due to a temporary change in the terminology. In all other years, the data report expenditures for “security and safety services and equipment”; in 2016, on the other hand, the UN only published expenditures for an unspecified category named “security”. Source: Elaboration from UN Procurement Division website, https://www.un.org/Depts/ptd/procurement-by-commodity-table-detail/2019.

3.2. The EU and PMSCs

3.2.1. Talk: EU contractor support doctrine

Academic literature (Krahmann and Friesendorf Citation2011, Giumelli and Cusumano Citation2014, Krahmann Citation2018) and EU official documents have advanced two main justifications for the increasing private security procurement: cost efficiency and capabilities’ gaps (Council of the European Union Citation2014, p. 42, European Parliament Citation2017, para. H). In addition, the European Parliament also noted that PMSCs are often used “for reasons of political convenience to avoid limitations on the use of troops, notably to overcome a possible lack of public support for the engagement of armed forces” (European Parliament Citation2017, para. H). The EU indirectly endorsed the use of well-regulated PMSCs by supporting the 2008 Montreux Document on Private Military and Security Companies and the ensuing International Code of Conduct for Private Providers (ICoC). Nevertheless, both the Parliament and the Council also warned that contractor support “is not the ultimate solution and will not resolve all of the capability gaps”, stressing that national military capabilities should be “the foremost option” (Council of the European Union Citation2014, p. 42).

The three hitherto published versions of the EU Concept for Logistic Support for EU-led Military Operations perfectly illustrate EU policy on the use of PMSCs. In the first version published in 2008 (COSDP 555), guidance on contractors in crisis management operations took up only one page, merely outlining the different forms of support available. In the second version published in 2011 (CSDP/PSDC 177), basic information was added on outsourcing procedures for CSDP missions, the need for coordination, and the risks of contracting failure. In the third version published in 2018 (CSDP/PSDC 531, p. 35), contracting with PMSCs was explicitly mentioned as requiring “special consideration”. In 2014, the EU drafted an additional EU Concept for Contractor Support to EU-led Military Operations (CSDP/PSDC 220), which provides additional guidance to troop-contributing countries, headquarters, and companies offering services in support of EU-led military operations. According to this Concept, the use of PMSCs is “possible, but should be limited”, and “any use of force [… ] must not go beyond self-defence, the defence of third persons and the defence of designated property, without use of deadly force” (CSDP/PSDC 220, p. 31). When it comes to the selection procedures, the Concept stipulates the following mandatory requirements for armed PMSCs:

They should have been providing armed security services for at least five years;

They should have a valid license to provide armed security in their Home State;

They should have a valid license to provide armed security services and import, carry and use firearms and ammunition in the Territorial [i.e. Host] State (CSDP/PSDC 220, p. 24)

A more recent European Parliament resolution further warned that “no local PSC should be employed or subcontracted in conflict regions” and that the EU should favour companies “genuinely based in Europe” and subjected to EU law (European Parliament Citation2017, para. 14). However, this resolution only concerns military CSDP missions and it is not binding, so its “impact in the theatre remains unclear” (Krahmann Citation2018, p. 13).

3.2.2. Action: EU’s use of private military and security companies

As acknowledged by academic studies (Krahmann and Friesendorf Citation2011, Tzifakis Citation2012, Giumelli and Cusumano Citation2014, Krahmann Citation2018) and internal documents (Council of the European Union Citation2014, European Parliament Citation2017), the EU’s use of PMSCs is now a widespread practice. While PMSCs have primarily been used to support CSDP missions, they have also guarded EU buildings located in the EU Member states (see below). Moreover, PMSCs are increasingly involved in implementing EU migration policies, including surveillance and security in asylum seekers’ hotspots (Davitti Citation2019). In the future, according to a 2017 European Parliament resolution, PMSCs could also “play a more important role in the fight against piracy and in improving maritime security” as well as cyber defence and surveillance (European Parliament Citation2017, para. R). While the Parliament also stressed that PMSCs “directly contributes to the EU’s reputation” and, therefore, demanded that the Commission and the Council produce an overview of “where, when and for what reason PMSCs have been employed in support of EU missions” (European Parliament Citation2017, para. 7), no such document has been drafted so far, making the collection of systematic information on EU contractor support difficult. The following overview based on open sources is, therefore, only indicative and most likely incomplete.

PMSCs have played the most significant role in CSDP missions. While the services provided vary considerably, the EU has relied on PMSCs in 8 (out of 11) military and 9 (out 26) civilian operations it has launched since 2003. As indicated in , base and personnel support were the most frequently contracted services in military missions, while security (static, mobile and personal protection for buildings, convoys and personnel) was in highest demand in civilian missions. As they – unlike military missions – lack the capabilities to provide force protection for their own personnel, civilian CSDP missions “regularly contract PMSCs for security guarding and protective services, even where these missions are deployed alongside military operations” (Krahmann Citation2018, p. 2). Contractors from Hart and G4S, for instance, were used to protect the police trainers deployed for operation EUPOL Afghanistan, hampered by both a shortage of EU police personnel and restrictions on where these personnel could be deployed. Notably, only three EU countries participating in the mission authorised the dispatch of their personnel to the Taliban-ridden Helmand region (House of Lords Citation2011, p. 29). The political constraints associated with military force activation processes also prompted the outsourcing of static and mobile security for the EUBAM Libya mission. In this case, EU officials turned to PMSCs as Italy withdrew their initial offer to dispatch a military police unit after their request to lead the mission was denied (Interview with EUBAM Libya official).

Table 2. CSDP operations and PMSCs contracting.

Other services outsourced include consultancy and training, advice and intelligence, transportation, and construction. Four civilian missions (EUPOL COPPS in the Palestinian Territories, EUPOL Afghanistan, EULEX Kosovo and EUMM Georgia) have contracted out all the aforementioned services. Among military missions, EUFOR/Operation Althea in Bosnia and Herzegovina contracted all services except for transportation. In all other EU-led military operations, “[c]ontractor support […] mainly focusses on logistic support functions; but, in general, it can provide an essential part of the support to the military” (Council of the European Union Citation2014, p. 9).

International and local PMSCs are also used to protect EU embassies, Special Representatives, and election monitors worldwide (Giumelli and Cusumano Citation2014, p. 39, Krahmann Citation2018, pp. 11–12). Since its creation in 2010, the European External Action Service (EEAS) has emerged as a significant employer of PMSCs worldwide, “spending hundreds of millions of euros a year on protection of foreign buildings and staff” (Rettman Citation2019). This covers “fully integrated security services” for EU posts in fragile states as well as “day-to-day security guards for the rest of its 136 foreign delegations” that do not qualify for “fully integrated” treatment (Rettman Citation2012). The former contracts include, for example, a €55-million contract with Page Protective Services in Afghanistan (2013) and two contracts with Argus Security Projects in Yemen and Saudi Arabia totalling €28 million (2014) (Krahmann Citation2018, p. 12).

3.3. NATO and PMSCs

3.3.1. Talk: NATO contractor support doctrine

While NATO has relied on contractors after the end of the Cold War, its contracting policies long remained unsystematic for two main reasons. First, most of the services outsourced consisted of low-profile support tasks to in benign environments like Germany and Italy. Second, PMSCs have usually been contracted by individual member states. During operations IFOR and KFOR in Bosnia and Kosovo, for instance, half of US forces consisted of contractors (Dunigan Citation2012). In response to its growing involvement in operations out of areas, however, NATO itself started to directly engage with commercial providers of military support. Consequently, both the Allied Command and the Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA) have signed contracts for security and support services (Evans Citation2012, Krahmann Citation2016). Moreover, NATO as an organisation has also endorsed a well-regulated use of PMSCs by communicating its support for the Montreux Document and the ensuing ICoC.

As contractor support was primarily left to individual member states, NATO doctrine long remained silent on the use of PMSCs. However, since the “prudent use of contracting” is increasingly seen as essential, NATO (Citation2007, p. 100) has stepped up its efforts “to ensure enhancement of the contract process, reduction of competition between nations and realisation of economies scale”. To that end, the latest versions of the NATO Logistics Handbook, published in 2012 and 2007, both dedicate an entire chapter to “contractor support to operations”. The term “contractor” covers all the activities traditionally provided by PMSCs, including weapons and communication systems maintenance, strategic transport, air-to-air refuelling, as well as security and ancillary medical services (NATO Citation2012, p. 161). Both handbooks stress that “contracted support solutions for operations have now become routine within NATO” (NATO Citation2012, p. 12). In addition, each document acknowledges that contractor support may be considered when there is a need for “local labour and operational continuity” or when “military manpower strength […] is not available in sufficient numbers” or “limited by a political decision” (NATO Citation2007, p. 101; NATO Citation2012, p. 157).

The handbooks, however, also draw limitations to the use of contractors, stressing the risks attached to their use. Most notably, the 2012 Handbook warns that “contractor support is not applicable to combat functions”, but limited to technical and support services. Both Handbooks also stress that contractors enjoy civilian status and should not be deployed in hostile environments, stressing that “operations that entail a higher risk of combat … are less suitable for outsourcing than lower-risk operations such as peacekeeping” (NATO Citation2012, p. 162). For the same reason, in the early stage of an operation, most tasks should be “performed by military units for reasons of high risk, efficiency, operational effectiveness and security”. Only when the environment becomes benign, selected support functions can be gradually transferred to contractors (NATO Citation2007, p. 105). As further explained by the NPSA instructions, military commanders are also expected to “order the removal of all, or some civilians” should the situation deteriorate (NATO Citation2021, p. 18).

Moreover, as contractors are non-combatants, NATO forces should “take such steps as are reasonable to ensure their safety” (NATO 2020, p. 20) and “provide security for them” (NATO Citation2012, p. 162), weighting “the benefits of using contractors … against the resources required to ensure their health and safety” (NATO Citation2007, p. 105). While acknowledging the utility of contracting, the Handbooks also stress that their use increases the risk of intelligence leaks and enemy interference. Accordingly, using host country nationals “demands management by security vetting and monitoring of these personnel” (NATO Citation2007, p. 105).

3.3.2. Action: NATO’s use of private military and security companies

Member states’ defence budget cuts and changing strategic posture – shifting from territorial defence to expeditionary power projection – have turned contractors into an important component of NATO’s military force structures. Consequently, NATO resort to contractors has grown enormously over time. Most notably, private companies transport over 90% of NATO’s logistical supplies. Contractors operating in European bases have provided crucial capabilities for bombing missions against Libya and Serbia, including air-to-air refuelling (Berguizen Citation2018).

Unlike the EU and the UN, NATO has conducted few crisis management operations requiring boots on the ground outside member states’ territory. However, one of these missions – the International Stability Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan – required the deployment of up to 130,000 soldiers over 12 years, which arguably made it the largest multinational crisis management operation ever conducted (Auerswald and Saideman Citation2014). Consequently, evidence will be mainly drawn from the ISAF mission. Nevertheless, contractors have consistently provided both logistics and security for NATO operations IFOR and KFOR in the Balkans. In Kosovo, NATO relied for the first time on a “contracted Medical Treatment Facility” providing services, including surgery interventions to alliance soldiers (NATO Citation2018).

Over 95% of NATO’s logistics in Afghanistan was outsourced to commercial actors (Van Duren Citation2010). Initially mandated with securing Kabul only, ISAF became an increasingly large mission after 2003, when it gradually expanded throughout Afghanistan. The complexity of the terrain, the persistence of the Taliban insurgency, and the unreliability of host country support stretched NATO military manpower thin. Alliance members, however, failed to increase the number of boots on the ground accordingly. As argued by Rynning (Citation2013), ISAF force activation processes were “an exercise in frustrated diplomacy that saw NATO commit too few forces to meet the minimum force requirements drawn up by its own military authorities”. Even when member states mobilised their military personnel, caveats and tight rules of engagement often prevented their deployment in the most dangerous areas of Afghanistan (House of Lords Citation2011, Auerswald and Saidemann Citation2014). As repeatedly stressed by ISAF commander-general McChrystal, insufficient manpower caused the Taliban to gain the upper hand, putting NATO forces at risk of defeat (Cusumano Citation2017, p. 108). As a result, contractors were increasingly used as force multipliers to bridge the gap between ISAF operational needs and NATO countries’ unwillingness to deploy additional forces to Afghanistan (Krahmann Citation2016, Cusumano Citation2017).

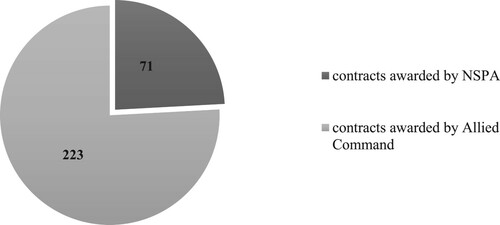

While most PMSCs were directly hired by member states, NATO directly signed construction and engineering contracts for common ISAF facilities and infrastructure, such as Kabul and Kandahar’s airports, and relied on contractors for strategic airlift, satellite communications, demining, and real-life support for troops (Krahmann Citation2016). Deploying, fielding, and supplying NATO forces in a landlocked, mountainous country far from member states’ territory severely challenged Allied militaries’ logistical capabilities, prompting an especially extensive use of contractors (Davids et al. Citation2013). By the summer of 2010, the Basic Ordering Agreement signed by NATO JFC HQ Brunssum “represented half of all fuel support to ISAF, providing more than three million litres of fuel daily to TCNs [Troop Contributing Nations] in Afghanistan” (Evans Citation2012, p. 18). NATO contractors mainly provided this fuel through truck convoys travelling from the Indian Ocean through impervious, Taliban-ridden regions, where they were frequently attacked (interviews with NATO military officers). While no systematic figures on NATO spending on contractors are publicly available, a report by the International Board of Auditors shows that, NATO’s Allied Command and NPSA awarded support contracts for almost 300 million dollars in 2012 only ().

Figure 3. Contracts awarded by NATO in Afghanistan in 2012 (USD millions).

Source: Elaboration from NATO International Board of Auditors (2015).

While the Allied Command and NSPA directly outsourced few security services, NATO’s indirect reliance on PMSCs was extensive. As member states’ soldiers were too few to protect their logistical supply lines, the prime contractors tasked with providing NATO forces with equipment, food, and fuel like Supreme had to hire armed private security guards as subcontractors to defend their convoys travelling from Pakistan to Kabul (Interview with NATO officer 3). Owing to this large demand for security, around 90 PMSCs were active in Afghanistan (Krahmann Citation2016).

4. Analysis: organised hypocrisy and security privatisation

Even if the UN, the EU, and NATO differ significantly in mandate, structure and the type of crisis management operations they engage in, their resort to PMSCs displays important similarities. Not only have the UN the EU, and privatised security and support services: each organisation’s resort to PMSCs has exceeded and diverged from its official policy and doctrine. The nature and size of each IOs’ gap between talk and action on PMSCs, however, varies significantly.

The UN approach to security privatisation has been fraught with glaring organised hypocrisy. Two distinct gaps between talk and action can be found. First, the Rapporteur and Working Group on Mercenaries appear to have preached in the desert for over a decade, rhetorically denouncing the threat posed by PMSCs, while UN resort to armed contractors increased steadily. A second, significant inconsistency can be found when examining official UN policy on security outsourcing announced by the Secretary General in 2011 and the Security Manual formulated by the UNDSS in 2012. In both cases, the use of PMSCs is referred to as a solution to be pursued only in “exceptional circumstances”. As demonstrated by academic scholarship and denounced by the Working Group, UN agencies’ outsourcing practices frequently depart from this principle. Far from serving as a last resort, PMSCs have often been used as a “default option” (Tkach and Phillips Citation2020, p. 115). Therefore, the talk, and actions on PMSCs formulated by UN bodies and agencies are clearly decoupled.

Several, less pronounced gaps can be found between EU talk and action surrounding the use of PMSCs. First, the extensive security outsourcing in both EU military and civilian missions is inconsistent with the 2014 EU Concept for Contractor Support to EU-led Military Operations claim that the use of armed private security providers should be limited and European security personnel should be preferred. As indicated in , PMSCs’ services have been used in almost every second CSDP mission conducted by the EU thus far. Security has been most frequently outsourced by civilian missions, which lack independent force projection capabilities. Second, contrary to the European Parliament calls, not all PMSCs hired by the EU were genuinely based in Europe. Publicly available data on EU contracting (European External Action Service 2020) suggest that almost all contracts procured by the EEAS have been with locally registered companies or local branches of global PMSCs (e.g. G4S, Securitas, Argus), sometimes registered under different local names. In CSDP missions, contracting local PMSCs has been less common, but many contracts have been awarded to UK-registered companies, which no longer count as EU-based. Third, not all PMSCs complied with EU regulations. In 2015, for example, 38 Members of the European Parliament signed a letter to the president of the European Commission demanding that all EU institutions end contractual relations with a PMSC that “engaged in providing support for activities that constitute war crimes” (Nielsen Citation2020). Fourth, according to the 2014 EU Concept for Contractor Support to EU-led Military Operation, EU-hired PMSCs should have a valid licence to provide private security services in their home state, as defined by the Montreux Document (Council of the European Union Citation2014, p. 24). However, this requirement was not fulfilled in all CSDP missions. Security for operation EUBAM Libya, for instance, was repeatedly contracted out to PMSCs that had no authorisation to operate on Libyan territory by Tripoli’s National Transitional Council (Interview with EUBAM Libya official).

Some gaps between NATO’s talk and action on PMSCs have also emerged over the last decades. A first, small inconsistency can be found in Kosovo, where the outsourcing of medical support went far beyond the ancillary services described in NATO’s documents. Moreover, the 2007 and 2012 Logistics Handbooks warn against contracting operations that entail a high risk of combat and threaten contractors’ safety. Notwithstanding the large numbers of casualties that these activities entailed, the transportation of fuel and supplies amid the insurgents-ridden Southern Afghanistan was systematically outsourced. Relatedly, NATO handbooks stress that in the early stage of an operation, most tasks should be performed by military units and only transferred to contractors once an area becomes stable. Nevertheless, when operation ISAF was expanded beyond Kabul, NATO’s engagement in counterinsurgency operations throughout Afghanistan increased rather than reduced reliance on PMSCs, contradicting the commitment to remove civilians from combat-intensive areas of operations. Despite the high risks faced by contractors, NATO (2012, p. 162; 2007, p. 105) arguably departed from its commitment to “provide security for them” and “ensure their health and safety”, forcing fuel and supplies providers to use local PMSCs as subcontractors. In turn, NATO’s indirect and unregulated reliance on warlords and militia seems at odds with the commitment to vet and monitor local contractors.

In each of the IOs examined above, gaps between talk and action on the use of PMSCs emerged from the friction between logics of consequences and logics of appropriateness. Reconciling the need for manpower that member states were unwilling to provide with the imperative to pay lip service to societal logics of appropriateness prompted a decoupling between each organisation’s talk and action. The size and nature of these gaps, however, depend on how these IOs have interpreted norms like the state monopoly of violence and the mercenary taboo. On the one hand, as the custodian of developing countries’ self-determination, the UN has developed an especially broad interpretation of the state monopoly of violence and a strong suspicion of commercial providers of security, which continued to be loosely associated mercenaries and seen as a threat to states’ sovereignty and human rights. As bodies like the Working Group on Mercenaries continue to see PMSCs as inherently problematic actors, UN doctrine referred to the use of armed contractors as an anomaly and a last resort, in an attempt to minimise the reputational risk attached to an officially sanctioned use of PMSCs’ services. Consequently, the UN has ultimately been hypocritical about its very use of PMSCs.

The EU and NATO, on the other hand, showcase a more pragmatic approach to private security providers. Influenced by the belief that commercial actors can be effective providers of crisis management brought about by the rise of neoliberalism, these IOs have developed a narrower interpretation of the anti-mercenary and state monopoly of violence norms, seen as only prohibiting the commercial provision of combat. Consequently, EU and NATO doctrine have been more straightforward in officially acknowledging the use of PMSCs in crisis management, seen as an entirely legitimate practice. However, some smaller gaps between talk and action have emerged in the way PMSCs were used in the context of specific operations, which departs from the EU and NATO’s own doctrinal red tapes. Most notably, civilian CSDP missions depart from the EU’s pledge to limit the use of armed PMSCs and NATO’s commitment to ensure the safety of its civilian contractors and minimise their deployment in harm’s way (Vierucci and Korotkikh Citation2018). These inconsistencies have primarily occurred in hostile theatres like Afghanistan and Libya, where demanding operational requirements clashed against tight political constraints over the deployment of member states’ personnel, prompting the EU and NATO officials to employ contractors to a larger extent than their official policy allows.

5. Implications

In complex, political organisations with multiple principals and identities like IOs, hypocrisy is not a conscious decision but an inevitable and perhaps even necessary outcome of the attempt to simultaneously manage contradictory expectations. Consequently, our argument does not entail any normative judgement against the EU, NATO, or the UN. Although gaps between talk and action may be inevitable for collective actors simultaneously subjected to several demands and constraints, organised hypocrisy also entails drawbacks, hindering organisational coherence and possibly tarnishing its reputation once unveiled (Lipson Citation2007). Evidence from the EU, NATO, and the UN alike forcefully shows that ambiguity on the use of contractors has problematic implications, potentially affecting both the effectiveness of crisis management operations and the broader credibility of the IOs examined.

Media and academics have questioned official documents’ claim that the PMSCs’ supporting EU missions were efficient, effective, and readily deployable. A series of articles by the EU observer documented repeated renewal of several contracts despite “serious shortcomings” in past performance, including security incidents, overpricing and false reporting (Rettman Citation2012, Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2019). These findings resonate with Krahmann and Friesendorf’s study of EU security privatisation, which warns against risks like lack of coordination and monitoring as well as “wastefulness and corruption” (Citation2011, p. 29). The use of private security contractors in Libya was particularly problematic. In 2012, the decision to hire G4S guards “broke the EU's own tender rules and annoyed the Libyans, who said it violated their sovereignty” and did not authorise their deployment (Rettman Citation2012). GardaWorld – the PMSC tasked with protecting EUBAM Libya personnel – saw its weapons confiscated at Tripoli’s airport and eventually stolen, causing EU staff to remain virtually unprotected and unable to travel outside the mission compound for over two months. Both G4S and GardaWorld were later investigated by the EU Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) (Interview with an EUBAM Libya official).

NATO also offers several compelling illustrations of the problems attached to the large-scale use of PMSCs. The resort to unvetted local private security companies, often little more than militias with a flimsy corporate façade reportedly involved in “all sorts of criminal activities” (US House of Representatives Citation2010), was frequently detrimental to the local population’s safety (Krahmann Citation2016). Furthermore, extensive resort to PMSCs had problematic consequences for capacity-building. As contractors often enjoyed higher salaries than military personnel, the possibility to work for PMSCs affected retention rates within local security forces, leading many recruits to desert after receiving basic training (House of Representatives Citation2010, Dunigan Citation2012). In Afghanistan in particular, NATO’s reliance on unaccountable PMSCs run by local strongmen fuelled patronage politics and the fragmentation of power between tribes, thereby undermining the authority of Kabul’s central government (US House of Representatives Citation2010, Krahmann Citation2016, Cusumano Citation2017).

Last, studies on the privatisation of UN peacekeeping concur in noting that while PMSCs have provided otherwise unavailable manpower, their effectiveness is merely “illusory”, and the privatisation of peacekeeping support may entail dysfunctional outcomes. Most notably, the possibility that PMSCs working for the UN engage in human rights abuses’ risks tarnishing the UN’s image as a humanitarian organisation (Tkach and Phillips Citation2020, pp. 3–7; Ostensen Citation2011). Bures and Meyer (Citation2019) and Bures and Cusumano (Citation2021) also observe that the resort to PMSCs in conflict and unrest situations may be seen as at cross-purpose with some of the norms identified as a cornerstone of the same rule-based international order that the UN itself is expected to safeguard such as the state monopoly of violence. The UN’s failure to uphold the norms it preaches may. therefore, damage both its ability to serve as a norm entrepreneur and its ontological security.

6. Conclusions

From a theoretical standpoint, our study adds to scholarship on organised hypocrisy by illustrating the pervasiveness of decoupling as a mechanism for IOs to reconcile incompatible demands, and also showing that the extent to which these translate into gaps between rhetoric and action depends on how different IOs interpret relevant norms. Moreover, our work contributes to private security scholarship by highlighting the interplay of logics of consequences and logics of appropriateness in shaping contractor support doctrines and practices. IOs and states alike have used PMSCs to obtain otherwise unavailable manpower by circumventing existing political constraints over the deployment of military and law enforcement personnel abroad. While normative considerations play a prominent role in restricting the use of PMSCs at the doctrinal level, the decoupling between talk and action allows organisations to rhetorically uphold norms like the state monopoly of violence and the duty of care towards civilians deployed in harm’s way without giving up the use of contractors as force multipliers. The fact that IOs may rhetorically pay lip service to norms they do not fully adhere to in practice also has important implications for the debate on the robustness and compliance pull of international norms. Future research should, therefore, continue to comparatively analyse gaps between talk and action across IOs, states, and non-state actors.

By examining the privatisation of security and military support by the EU, the UN, and NATO, our article has offered the first comparative analysis of the use of PMSCs by IOs, showing the existence of different degrees of organised hypocrisy surrounding contractor support to international crisis management. However, additional research is needed to advance our findings. Future research may examine other IOs that have maintained a critical approach towards PMSCs like the African Union and prove a more fine-grained analysis of different IOs’ contracting practices by zooming into the case of specific peace and stability operations.

Authors’ interviews cited in the article

Army Lieutenant Colonel Deployed to Mission ISAF, October 2010.

Army Major deployed to Mission ISAF, June 2014.

Army Major deployed to Mission ISAF, March 2014.

EU Official deployed to Mission EUBAM Libya, October 2015.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions, 2012. Reports on the department of safety and security and on the use of private security. UN General Assembly, No. A/67/624.

- Auerswald, D. and Saideman, S., 2014. NATO in Afghanistan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Avant, D., 2005. The market for force. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ballesteros, E., 1998. Report on the question of the use of mercenaries as a means of violating human rights and impeding the exercise of the rights of peoples to self-determination. Geneva: Commission on Human Rights, 54th Session. Available from: https://documents-dds- [Accessed 27 January 1998].

- Barnett, M. and Coleman, L., 2005. Designing police: interpol and the study of change in international organizations. International studies quarterly, 49 (4), 593–620.

- Barnett, M. and Finnemore, M., 2004. Rules for the world: international organizations in global politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Berghuizen, J., 2018. Outsourcing logistics: one step too far? NATO joint air power competence centre conference. Available from: https://www.japcc.org/outsourcing-logistics-one-step-too-far/.

- Brunsson, N., 1989. The organization of hypocrisy: talk, decisions, and actions in organisations. New York: Wiley.

- Brunsson, N., 2007. The consequences of decision-making. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bures, O., 2005. Private military companies: a second-best peacekeeping option? International peacekeeping, 12 (4), 533–546, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13533310500201951.

- Bures, O. and Cusumano, E., 2021. The anti-mercenary norm and united nations’ use of private military and security companies: from norm entrepreneurship to organized hypocrisy. International peacekeeping, 28 (4), 579–605, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2020.1869542.

- Bures, O. and Meyer, J., 2019. The anti-mercenary norm and united nations’ use of private military and security companies. Global governance: a review of multilateralism and international organizations, 25 (1), 77–99.

- Council of the European Union, 2014. EU concept for contractor support to EU-led military operations. No. CSDP/PSDC 220.

- Cusumano, E., 2017. Resilience for hire? NATO contractor support in Afghanistan examined. In: E. Cusumano and M. Corbe, eds. A civil-military response to hybrid threats. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Cusumano, E., 2019. Migrant rescue as organized hypocrisy: EU maritime missions offshore Libya between humanitarianism and border control. Cooperation and conflict, 54 (1), 3–24.

- Davids, C., Beeres, R., and van Fenema, P. C., 2013. Operational defense sourcing: organizing military logistics in Afghanistan. International journal of physical distribution and logistics management, 43 (2), 116–133.

- Davitti, D., 2019. The rise of private military and security companies in European Union migration policies: implications under the UNGPs. Business and human rights journal, 4 (1), 33–53.

- De Guttry, A., et al., eds., 2018. The duty of care of international organizations towards their civilian personnel. Berlin: Springer.

- De Nevers, R., 2009. Private security companies and the laws of war. Security dialogue, 40 (2), 169–190.

- DiMaggio, P. J. and Powell, W., 1983. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American sociological review, 48, 147–160.

- Dunigan, M., 2012. Victory for hire. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Ejdus, F., 2017. “Here is your mission, now own it!” The rhetoric and practice of local ownership in EU interventions. European security, 26 (4), 461–484.

- Evans, M., 2012. The silent revolution within NATO logistics: a study in Afghanistan fuel and future application. Monterey: Naval Postgraduate School.

- European Parliament, 2017. Private security companies: European Parliament resolution of 4 July 2017 on private security companies (2016/2238(INI)).

- George, A. and Bennett, A., 2005. Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Giumelli, F. and Cusumano, E., 2014. Normative power under contract? Commercial support to European crisis management operations. International peacekeeping, 21 (1), 37–55.

- Hansen, S. and Marsh, N., 2015. Normative power and organized hypocrisy: European Union member states' arms export to Libya. European security, 24 (2), 264–286.

- Hill, C., 1993. The capability-expectations gap, or conceptualizing Europe’s international role. Journal of Common Market Studies, 31 (3), 305–328.

- Krahmann, E., 2016. NATO contracting in Afghanistan: the problem of principal-agent networks. International affairs, 92 (6), 1401–1426.

- Krahmann, E., 2018. European Union and private military and security companies (PMSCs): consequences for “effectiveness, visibility and impact”. Presented at the 12th Pan-European conference on international relations EISA, Prague.

- Krahmann, E. and Friesendorf, C. 2011. The role of private security companies (PSCs) in CSDP missions and operations. European Parliament, No. PE 433.829.

- ICRC—International Committee of the Red Cross and Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA), Swiss Government, 2009. The Montreux Document on pertinent international legal obligations and good practices for states related to operations of private military and security companies during armed conflict. Geneva: ICRC.

- Leander, A., ed., 2013. Commercialising security in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Lipson, M., 2007. Peacekeeping: organized hypocrisy? European journal of international relations, 13 (1), 5–34.

- March, J.G. and Olsen, J.P., 1989. Rediscovering institutions. New York: Free Press.

- Meyer, J.W. and Rowan, B., 1977. Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. American journal of sociology, 83 (2), 340–363.

- NATO, 2007. Logistics handbook. Brussels: NATO Headquarters

- NATO, 2012. Logistics handbook. Brussels: NATO Headquarters.

- NATO, 2018. KFOR explores new frontiers in operational medical support. Available from: https://jfcnaples.nato.int/kfor/media-center/archive/news/2018/kfor-explores-new-frontiers-in-operational-medical-support

- NATO Support and Procurement Agency (NPSA), 2021. Instructions for NATO support and procurement agency contractors supporting operations and missions.

- Nielsen, N., 2020. G4S: the EU’s preferred security contractor. EUobserver, 6 Mar.

- Østensen, Å.G., 2011. UN use of private military and security companies: practices and policies. Geneva: DCAF, No. SSR PAPER 3.

- Panke, D. and Petersohn, U., 2012. Why international norms disappear sometimes. European journal of international relations, 18 (4), 719–742.

- Percy, S., 2007. Mercenaries: the history of a norm in international relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Petrov, P., et al., 2019. All hands on deck: levels of dependence between the EU and other international organizations in peacebuilding. Journal of European integration, 41 (8), 1027–1043.

- Pingeot, L., 2012. Dangerous partnership – private military & security companies and the UN. Berlin: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

- Rettman, A., 2012. Ashton to spend €15mn on private security firms. EUobserver, 9 Mar.

- Rettman, A., 2013a. MEPs voice worry on security deals at EU embassies. EUobserver, 15 Jul.

- Rettman, A., 2013b. British firm to guard EU diplomats in Beirut. EUobserver, 12 Aug.

- Rettman, A., 2019. Former EU top diplomat becomes security lobbyist. EUobserver, 28 Oct.

- Rynning, Sten, 2013. ISAF and NATO: campaign innovation and organisational adaptation. In: T. Farrell, F. Osinga, and J.A. Russell, eds. Military adaptation in Afghanistan. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 83–107.

- Spearin, C., 2011. UN peacekeeping and the international private military and security industry. International peacekeeping, 18 (2), 196–209.

- Tallberg, J., et al., 2020. Why international organizations commit to liberal norms. International studies quarterly, 64 (3), 626–640.

- Tkach, B. and Phillips, J., 2020. UN organizational and financial incentives to employ private military and security companies in peacekeeping operations. International peacekeeping, 27 (1), 102–123.

- Tzifakis, N., 2012. Contracting out to private military and security companies. Brussels: Centre for European Studies.

- UN Department of Safety and Security, 2012a. Guidelines on the use of armed security services from private security companies.

- UN Department of Safety and Security, 2012b. United Nations security policy manual, Chapter IV.

- UN General Assembly, 1976. Importance of the universal realisation of the right of peoples to self-determination and of the speedy granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples for the effective guarantee and observance of human rights. 31/34.

- UN Secretary General, 2012. Use of private security. UN General Assembly, No. A /67/539.

- UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries, 2014. Use of mercenaries as a means of violating human rights and impeding the exercise of the right of peoples to self-determination. UN General Assembly, No. A/69/338.

- UK House of Lords, 2011. The EU Afghan police mission. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201011/ldselect/ldeucom/87/8706.htm.

- US House of Representatives, 2010. Warlord, Inc.: extortion and corruption along the US supply chain in Afghanistan, report by the majority staff. Washington, DC: Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

- Van Duren, E.C.G.J., 2010. Money is ammunition; don’t put it in the wrong hands. A view on COIN contracting from regional command south. Militaire spectator, 179, 564–578.

- Vierucci, L. and Korotkikh, P., 2018. Implementation of the duty of care by NATO. In: A. De Guttry, et al., eds. The duty of care of international organizations towards their civilian personnel. Berlin: Springer, 243–265.

- Williams, P.D. and Bellamy, A.J., 2021. Understanding peacekeeping. 3rd ed. New York: Polity.