ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the extent to which the European Union is strategically engaging against terrorism. It builds on traditional scholarship on strategic thinking and elaborates an analytical framework to empirically assess strategic policy formulation at the supranational level in the case of terrorism. The framework revolves around three analytical categories: i) threat assessment; ii) objectives setting; and iii) policy measures. Through qualitative content analysis of text data, we show that, while objectives are clearly presented in the documents, the threat that the strategy is supposed to counter is unspecified. In addition to that, the formulation of concrete policy measures remains largely vague. Overall, the article adds to the growing academic debate on EU security governance and offers fresh empirical insights on strategic thinking in counterterrorism policy.

Introduction

In a highly dramatic way, recent events in Afghanistan have raised new debates and concerns about counterterrorism worldwide. In Europe, after the series of attacks by transnational terrorist organisations between 2015 and 2017, the question of responses to terrorism and “Jihadist” violence suddenly regained the central stage in late 2020. On 2 November, a young assailant shot at the crowd in the city centre of Vienna, killing four persons. On 29 October, three people were killed in Nice and a police officer was attacked in Avignon. One of the victims in Nice, a 70 years old lady, was beheaded. The same fate befell Samuel Paty, a high school professor in northern Paris. Mr Paty was killed by an 18-years-old teenager born in Chechnya few days after he had shown in class the (in-)famous cartoons of Mohammad originally published by the French satirical journal Charlie Hebdo in 2015. In the following days, the French authorities opted for a hard response, ordering massive police controls on Mosques and Muslim non-profit organisations, announcing the dissolution of different Islamic organisations considered as “extremist”, and expulsing more than 200 people owning double citizenship. Both President Emmanuel Macron and his Austrian counterpart, Prime Minister Kurz, mentioned the need to rethink European internal space of free movement as designed by the Schengen Agreements, opening a new debate on the status of counterterrorism (CT) in Europe.

In the following weeks, European Institutions showed a renewed activism. On 13 November 2020, the European Union (EU) home affairs ministers released a Joint statement to reinforce surveillance of religious worship places and online interactions.Footnote1 Shorty after, on 9 December 2020, the EU has published a document titled A Counter-Terrorism Agenda for the EU: Anticipate, Prevent, Protect, Respond, the first official agenda to be released after the 2005 Counterterrorism Strategy. The new agenda confirms the attempt by the EU to build internal and international credibility as a “security provider”, in line with long-term efforts dedicated to develop a EU strategic vision. Indeed, the fight against terrorism seems to subscribe to the declared intention by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to make geopolitics the leitmotiv of the EU, currently involved in the development of the so-called Strategic Compass for security and defence expected for Spring 2022. The announcement arrived as a response to mounting challenges facing the EU in recent years, summarised by Emmanuel Macron’s remark on the EU finding itself at “the edge of a precipice” surrounded by a “hostile world” (Economist 2019). Yet, despite its clear policy relevance and the efforts made in this direction (Bossong and Rhinard Citation2018), the specialised literature on counterterrorism still lacks a systematic account of the novel propositions and strategic formula elaborated by the EU in relation to this policy field and in light of this new security scenario. It is therefore pressing, we believe, for the literature on European security to go beyond the evaluation of institutional changes and provide empirically-based and threat-specific accounts of how security issues are interpreted and related responses evaluated. There are, indeed, a number of relevant questions that we find overlooked: How strategic is the EU counterterrorism strategy? What are the strategic elements that characterise the EU counterterrorism policy? Are there elements the EU is neglecting?

This paper aims to fill this gap by addressing these questions and by therefore exploring the extent to which the EU is currently strategically engaging against terrorism. To do so, we build on the renewed debate in International Relations (IR) and security studies on whether the EU can be considered a strategic actor (Winn Citation2019, Cottey Citation2020) and, if so, what are the key features of the EU strategic thinking (Léonard and Kaunert Citation2017, Nitoiu and Sus Citation2019, Panke Citation2019). The ability of the EU to think and act geo-strategically has been investigated in light of different, though overlapping, concepts such as EU security culture (Meyer Citation2006), EU international actorness (Kaunert Citation2010, Brattberg and Rhinard Citation2012, Čmakalová and Rolenc Citation2012, Ferreira- Pereira et. al Citation2016) and EU grand security strategy (Economides and Sperling Citation2018, Szewczyk Citation2021). Yet, empirically, there is still a lot to be shown, specifically in relation to the threat of terrorism. Indeed, in light of its cross-border and transnational nature, terrorism allows to investigate strategic thinking in its internal and external projection, a combination that is largely underestimated. In order to explore whether and to what extent we can talk about a strategic EU in the field of counterterrorism, we draw from traditional scholarship on strategic thinking. Largely and mostly used to address foreign policy issues or military affairs of state actors as well as warfare strategies of non-state actors, analyses of strategic thinking overall tend to ignore transnational or supranational actors such as the EU.

We believe that investigating the strategic features of European counterterrorism appears even more relevant in light of the crucial historical stage in which EU institutions are demanded to act, divided as they are between the expectations on their external projection and the dynamics of international fragmentation in both political and security terms. Hence, through content analysis of EU policy documents on counterterrorism, this article analyses the empirical salience and relevance of different strategic dimensions, namely: i) threat assessment; ii) objectives setting and iii) policy measures. The paper finds that, while objectives are clearly presented in the documents, the threat that the strategy is supposed to counter remains unspecified. It also shows that the formulation of concrete policy measures remains largely vague resulting in a set of different instruments – information sharing, border control, reliance on security expertise – rather than an ultimate CT strategy.

The article is structured as follows. The next section reviews the main research agenda concerning strategic thinking. The third section details the analytical framework and the methods. The fourth section presents the main findings. Finally, section five concludes and discusses potential policy implications.

Strategic thinking from Sparta to Brussels

Historical approaches to strategic studies rely on the idea that the core nature of strategy and strategic thinking has remained essentially unchanged throughout history (Kelly Citation1982), regardless of technological innovations which might have influenced their practical implementation (for an overview, see Platias and Koliopoulos Citation2010). As a consequence, contemporary scholars interested in studying strategy design and formulation still largely rely on lessons learned from the most eminent historical thinkers such as Thucydides, Sun Tzu or Carl von ClausewitzFootnote2 (see Heuser Citation2010). Understood in ancient Greece as the art and set of skills of the General (strategós), Thucydides emphasises fear as the explanatory factor for war, and therefore, for the need of strategy. Used for the first time in its modern interpretation by the French officer Paul Gideon Joly de Maizeroy in 1777, strategy was defined as “the science of the General […] to formulate plans, strategy combines times, places, means and different interests” (de Maizeroy 1777, p. 2, quoted in Coutau-Bégarie Citation2002, p. 57). As Rousseau (Citation2012, p. 75) points out, “strategy provides a theory of success” and as such, it entails considerations over means and capabilities to ensure security, survival and preservation of national interests. This essentially means that strategy is a process of coordination among the whole set of available policy options and instruments. In fact, as Beaufre (Citation1965, p. 22) clarifies, “[strategy] is the art which enables a man, no matter what the techniques employed, to master the problems set by any clash of wills and as a result to employ the techniques available with maximum efficiency”.

Going beyond strategic studies, we find a number of research traditions interested in understanding how actors respond strategically to relevant challenges. Among these, the literature on public policy and public administration has recently offered some useful reflections on strategy, understood as the process that links capabilities and aspirations. More precisely, strategy can be defined as “a concrete approach to aligning the aspirations and the capabilities of public organizations or other entities in order to achieve goals” (Bryson and George Citation2020, p. 3). In doing strategy, actors make “sure that aspirations can actually be achieved” by taking into account existing resources and constraints (Bryson and George Citation2020, p. 2). Therefore, strategising implies that policy-makers evaluate the costs and benefits of different options and adopt certain behaviours on the basis of the instruments they can access or create and the goals they expect to reach. Yet, strategic thinking does not operate in a vacuum. Strategy implies a relational opposition to a rival who would probably do everything in his or her power to nullify it (Tsakiris Citation2006). In other words, echoing Thomas Schelling, it seems safe to argue that the interpretation of strategy goes beyond a mere calculation of costs and benefits, or ends and means. By stressing the relational dimension of strategy, Schelling (Citation1960, p. 3) defines it as “the best course of action for each player” with respect to “what the other players do”. While we agree on the importance of thinking about the practice of strategy in its broader understanding as “the set of arguments and organising principles, embodied in documents and decisions, that explains the myriad of foreign policy choices and helps guide future paths” (Szewczyk Citation2021, p. 15), we also argue that a better understanding of strategy starts with an empirical grasp into the options and strategic evaluation an actor is considering with respect to a specific policy area. Overall, the conceptual framework we propose relies on a conception of strategy as a process of evaluation of policy goals identified to respond to a specific security challenge on the basis of an existing set of aspirations and capabilities.

Hence, when considering the current threat that transnational terrorism represents to European states, the EU not only could but also should be regarded as a strategic actor or, at least, investigated as such (Engelbrekt and Hellenberg Citation2010, Biscop and Coelmont Citation2013). Yet, in spite of the numerous recent institutional accounts (Bureš Citation2015, Monar Citation2015, Ferreira-Pereira et al. Citation2016), little has been researched about how the EU is currently strategically responding to it. Therefore, by adapting a traditional conceptualisation of strategy, this paper represents an original contribution to the current debate in EU security scholarship, specifically in the field of counterterrorism. Moreover, this study offers insightful elements also from a policy perspective. Investigating the EU strategic vision seems indeed crucial to better analyse the process of both policy formulation and implementation.

Analysing the EU strategic thinking: the methodological approach

In analysing strategic thinking in counterterrorism, we conceive of strategy as an evaluation based on the existing set of aspirations and capabilities to respond to a specific threat and achieve clearly articulated policy goals. From an operational point of view, first, we need to assess how the threat that the strategy expects to counter is conceived of and what kind of features are highlighted. Second, strategy also implies the setting of a certain goal to achieve. Operationally, this means examining the aims that actors intend to achieve given the existing capabilities and possible need to develop new ones. Third, strategy elucidates the concrete efforts needed to achieve goals. In this respect, at the operational level, we need to assess the policy measures and practical tools that are put in place. On these premises, our conceptual framework elaborates on the state of the art in strategic thinking scholarship and focuses on the above defined three operational dimensions: i) threat assessment; ii) objectives setting; and iii) policy measures.

As for the methodological approach, we depart from the idea stressed by Doyle (Citation2007) that strategies can be implicit or explicit. Whereas implicit strategies require an analysis of actor's interaction with its political and security background, explicit strategies – contained, for example, in documents published by governments and political actors – represent an actor’s official and public announcement about the way it expects to achieve goals and respond to inputs and challenges deriving from its environment. In this paper, we focus on the explicit dimension of strategy. Indeed, we argue, essential features of security strategies can be empirically captured through the analysis of key documents such as policy debates, white papers and public security documents. In this sense, we emphasise, strategy is also about communication. In this article, we have therefore investigated EU strategic thinking through computer-assisted qualitative content analysis of text data using NVivo. IR scholars have increasingly relied upon content analysis as a research method to systematically explore the content of communication (Pashakhanlou Citation2017) and, in line with this tradition, the empirical material for this research has been drawn from selected policy documents (N = 11) covering a period from 2015 to 2020. This time frame has been characterised by an unprecedented wave of mass-killing transnational attacks that has led to a renewed internal pressure on EU counterterrorism policy that we find particularly relevant to analyse.

We have systematically interpreted the documents and translated all the relevant meanings in the material into categories of a coding frame. The coding frame has been deductively generated in a concept-driven way and it is structured around the three above-mentioned operational dimensions (). The units of coding were defined in relative terms as those parts of the material that could be interpreted in a meaningful way with respect to the coding frame. In particular, they consisted of sentences or paragraphs (Schreier Citation2012).

Table 1. Coding scheme.

The first category, “threat assessment”, specifically considers the way the EU is interpreting the terrorism threat. In this respect, the analysis distinguishes between the “form and cause” – which concern the threat per se – and the “target” of the attacks. The category of the “objectives setting” refers to the aims the actor wants to achieve on the basis of existing resources and “constraints”. The third identified dimension, “policy measures”, specifically relates to the practical “means” and “responsible actor” ().

Analysis: talking the talk while walking the walk?

After the 2005 Counterterrorism Strategy, the 2020 Counter-Terrorism Agenda for the EU is the second official EU document describing the EU strategy against terrorism. The text is structured along four points which mirror the four main pillars of the strategy: i) anticipate; ii) prevent; iii) protect; and iv) respond. Differently from the 2005 strategy, there is an additional fifth (cross-)pillar which relates to the strengthening of international collaboration. As mentioned, we decided to analyse the latest 2020 Agenda together with a variety of documents published between 2015 and 2020 in order to better account for the process of strategy formulation (see Appendix).

What emerges from a preliminary analysis of the ensemble of text data is that EU strategic thinking against terrorism appears partially predictable but enlightening from different perspectives. details the results of an explorative phase of analysis. Not surprisingly, the threat (i.e. terrorism) is definitely the most recurrent concept.Footnote3

Table 2. Most frequent relevant words across documents.

Overall, this explorative search does not display any specific unexpected words. However, we do find a first primary insight on the EU approach to counter-terrorism, extensively focused on police and judicial cooperation. Interestingly, “Europol” is the most mentioned word (N = 761) followed by a relatively high number of references to “informing” (N = 629), both pointing to the question of information sharing both within institutions and between law enforcement organisations. As we shall see, this theme recurs throughout the analysis in different ways. In the remainder of this section, we present what the qualitative analysis of the texts reveals with regard to the EU strategic thinking.

Threat assessment

Text data show the absence of specific characterisations of the terrorism threat. As an overall evaluation, it seems fair to argue that the strategy does not develop or communicate a clear image of the threat, which is instead generally referred to as “terrorism”.

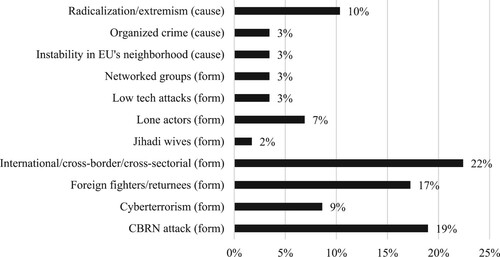

There are, nonetheless, some relevant findings worth exploring. When analysing the category referring to “form and cause” (), two interesting features emerge. Whereas the description of the “form” reveals particular attention dedicated to the spatiality of terrorism, the “cause” mostly pertains to the processes of radicalisation.

The spatiality of terrorism seems particularly relevant in relation to foreign fighters and terrorist networks. Both aspects confirm and insist on the transnationality and cross-border nature of the threat – which present the highest saliency in the data (22%) – and display an interesting geographical sensitivity. In particular, these aspects point to the relation between the external and the internal dimension of European security. The reference to the foreign fighters (17%), and specifically to “returnees”, speaks to the long-standing debate about European citizens or residents who left Europe to fight along the lines of armed groups in the Middle-East:

in reality the number of returnees has declined significantly in the last two years, and some argue that it is probable that most of the remaining foreign fighters have been killed in the conflict zone or imprisoned there. Nonetheless, the issue of returnees raises many challenges: First, they are perceived as a security threat. During their stay in conflict zones, they acquire combat experience, which prompts fears that they may perpetuate the terrorist threat to the EU through radicalising, fundraising and facilitation activitiesFootnote4

whereas developments and instability in the Middle East, North Africa, and Caucasian regions have enabled Daesh and other terrorist groups to gain a foothold in countries bordering the EU such as those of the Western Balkans, and the nexus between internal and external security has become more prominent.Footnote5

Yet, document analysis confirms that the terrorism threat against Europe is mostly addressed as a micro-level security challenge as opposed to a symmetrical state-related threat. In particular, the micro-nature of the threat is also explored in relation to terrorism conceived of as a networked threat (3%). Networks, the documents insist, are the channels that connect terrorist organisations operating along the MENA region and Europe, where indeed there are “home grown terrorists operating in networks”.Footnote6

As already mentioned, an overly discussed element that functions as trait d’union among these forms of threat is radicalisation, defined as a process “leading to terrorism and violent extremism”.Footnote7 Despite the fact that the documents do not specify in concrete terms how radicalisation leads to violent extremisms, the two concepts are seen as strictly related:

Terrorism in Europe feeds on extremist ideologies. EU action against terrorism therefore needs to address the root causes of extremism through preventive measures. Throughout the EU, the link between radicalisation and extremist violence is becoming ever clearer.Footnote8

In discussing radicalisation and its connection to the above-mentioned issue of foreign fighters, an interesting generational dimension emerges. In fact, part of the preventive discourse emphasises the youth as potential source of danger – de facto criminalising youth. In particular, the EU warns about the return to Europe of those children taken or born in countries exposed to major terrorist events:

child returnees pose specific problems as they can be both victims and potential perpetrators at the same time.Footnote9

some of these children (aged above 9 years) have undergone military training in conflict zones, prompting questions about the impacts this might have upon their return on EU soil, the “threat” this might pose, and the possible social/criminal response.Footnote10

Overall, the attention dedicated to individuals or groups of individuals – being foreign fighters or radicalised people – confirm a general understanding of terrorism as a micro-level security threat. This stands out as a process of individualisation of counterterrorism, where individuals are considered the main threat to national security.

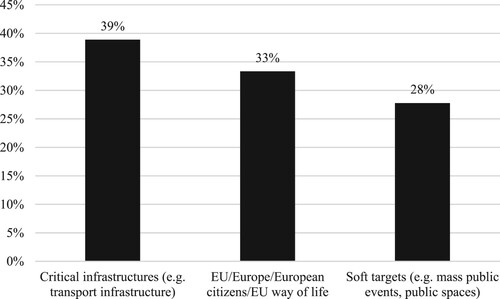

Nonetheless, when looking at the way the documents address the description of potential targets of the threat, counterterrorism efforts remain mostly focused on the characteristics and resources of the referent actor, namely, Europe (understood as both the EU and its member states). As displays, the strategic vision of the EU insists on the collective nature of key sensitive areas – the so-called soft targets – defined as public spaces and mass public events where terrorists are more likely to attack and cause victims.

However, we do find some connections between the target and the characteristics of the threat. Indeed, public spaces are chosen in order to maximise lethality – despite the fact that many attacks are implemented with “low tech” instruments such as vehicles and white weapons:

Besides more complex “high intensity” attacks combining explosives and firearms, Europe has also been hit by a growing number of “low tech” attacks against public spaces carried out with everyday items such as a vehicle for ramming or a knife for stabbing. The targets are often chosen with the intent to causing mass casualties.Footnote11

Objectives setting

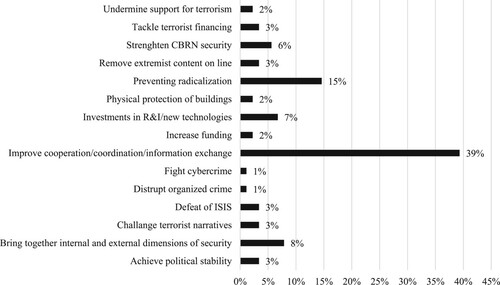

Analytically, the process of objectives setting includes references concerning the aims associated to a certain policy option and those related to potential constraints and limits to its implementation. As shows, much of the objective-setting effort is based on what Europe can do better and, specifically, on the attempt to increase coordination among different actors.

Not surprisingly, the crucial objective discussed across documents is the need to increase cooperation and coordination, which implies intense cross-national and multi-actor information exchange (39%). A stronger cooperation would first pass through a more effective and harmonised implementation of legal instruments adopted by Member States. In this sense, the EU seems engaged in emphasising how the threat of terrorism could represent the needed pressure on European actors to force them to act coherently. This is all in line with a typical neo-functionalist, problem-driven approach to further integration in the security policy field.Footnote12 Accordingly, another relevant aim concerns the connection between the internal and the external dimensions of security (8%), which is crucial to the creation of a cross border space of intervention.

With respect to the broader aim concerning the prevention of radicalisation (15%), much of the discussion revolves around the need to develop indicators able to signal processes of radicalisation. Here, the EU confirms a typical preventative approach focused on targeting radicalisation, which is seen as a pre-condition to terrorist violence.

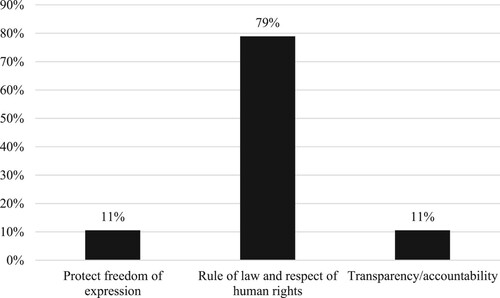

As far as the constraints are concerned, we consider both expected material and potential political costs. In this regard, it is interesting to notice that much of the constraints are in fact related to the internal characteristics of European countries as examples of liberal, rule of law-based, political orders ().

Documents are indeed outspoken in terms of limits and standards of procedure imposed by existing legislations specifically safeguarding fundamental rights:

All measures taken to counter terrorism must comply with international law, including human rights law (including the Convention on the Rights of the Child, where appropriate), refugee law, and international humanitarian law.Footnote13

Policy measures

In order to evaluate the third aspect of strategic thinking, namely, policy measures, we focus on two categories: means and responsible actors. Our analysis reveals that in the case of the EU approach to CT, key policy measures can be distinguished into: i) practical means and networks/experts groups; and ii) agencies as responsible actors. Coherently with what has been discussed above in relation to coordination, these categories suggest that, in its response to terrorism, the EU focuses mostly on the development of policy instruments for information and knowledge exchange. Yet, there is consistently less accuracy across the documents in describing and communicating measures and practical solutions. Specifically, as for the first category, we find it interesting that the EU is discussing means on two levels. On the one hand, documents present a series of practical initiatives and tools that are expected to be employed in the fight against terrorism. On the other hand, a large part of the discussion is dedicated to the creation of and support to networks and expert groups that are understood as a means to increase the engagement of different expertise and, therefore, as a specific tool at EU disposal in its fight against terrorism. presents the different means that are presented across the documents.

Table 3. Presented CT means (2015–2020).

In particular, the relevance of the Passenger Name Record (PNR) and the Prüm framework as information exchange tools is highlighted. The PNR is the system containing the ensemble of information provided by passengers and collected by airlines and then stored by Passenger Information Units (PIUs). The PNR is defined as

fully compatible with the Charter of Fundamental Rights while providing a strong and effective tool at EU level […]. PNR data has proven necessary to identify high risk travellers in the context of combatting terrorism, drugs trafficking, trafficking in human beings, child sexual exploitation and other serious crimes.Footnote14

the system is falling short of its potential because at this stage only a limited number of Member States have implemented their legal obligations and integrated the network with their own systems. This impedes the overall effectiveness of the Prüm framework in catching and prosecuting criminals.Footnote16

There is another interesting aspect emerging from the analysis of the measures that we believe is worth exploring further: the attention to border management. While we could not detect any reference to any specific CT means as the ones shown in , border management is still often mentioned as an important means to fight terrorism. This finding appears interesting considering that irregular border crossing or migration are never mentioned in the threat assessment. We find then that, by discussing and justifying control over borders as a mean to respond to the transnationality of the terrorist threat, specifically in relation to the question of foreign fighters, the documents do stress the relationship between terrorism and migration. To put it more clearly, the attention to border management to fight transnational movements of foreign fighters reinforces a general security-oriented discussion about mobility and therefore migration. Such an emphasis on the dangers of transnationality when discussing terrorism clearly impacts another category of actors, namely, the migrants (see Baker-Beall Citation2019 and Ragazzi and Walmsley Citation2020).

With regard to the networks and experts groups, the documents highlight the need to create and institutionalise them to strengthen the cross-national and multidisciplinary dialogue among actors engaged at different levels in the fight against terrorism. This would also increase the potential of information-sharing practices. presents an overview of the networks and expert groups discussed in the documents. These networks and expert groups gather together practitioners from national and supranational security agencies as well as scholars and civil society actors. In this sense, the circulation of information and expertise in the form of shared knowledge across professional domains is considered to be crucial to counterterrorism action.

Table 4 . Networks/Expert Groups.

In describing networks and expert groups, the documents make direct references to local actors, specifically in the cases of the EU Crime Prevention Network (established in 2001 and that focuses on crime prevention knowledge and practices among EU Member StatesFootnote18), the Policy Dialogues on Security and the radicalisation awareness network (RAN).Footnote19 However, whereas great emphasis is put on the need for cooperative work, the exchange of knowledge and distribution of power and responsibilities among relevant actors remain essentially a blind spot. Overall, we find a prevalence of references to EU actors that seems to reinforce the attempt to develop a stronger EU counterterrorism capacity also through a more ambitious taking on responsibilities. Even in this case, however, it is worth considering that the operative role attributed to EU actors remains limited and rather confined to a supporting role. The documents, in fact, rarely mention or elaborate on internal and external operative actions to be undertaken directly by EU agencies.

In relation to the second category of responsible actors, we find that, other than important references to Member States’ apparatuses, much of the responsibility is put on agencies. Specifically, the analysis clearly shows an agentification of policy solutions where responsible actors – the agencies – are described as policy measures per se:

Given the increasing nexus between different types of security threats, policy and action on the ground must be fully coordinated among all relevant EU agencies […]. These agencies provide a specialised layer of support and expertise for Member States and the EU. They function as information hubs, help implement EU law and play a crucial role in supporting operational cooperation, such as joint cross-border actions. It is time to deepen cooperation between these agencies.Footnote20

EU agencies play a crucial role in supporting operational cooperation. They contribute to the assessment of common security threats, they help to define common priorities for operational action, and they facilitate cross-border cooperation and prosecution. Member States should make full use of the support of the agencies to tackle crime.Footnote21

Table 5. Agentification and specialisation of CT policy measures.

There is a clear attempt to emphasise a larger role and responsibility of the EU in the general European response to terrorism by legitimising the creation and work accomplished within specialised security agencies such as EUROPOL, EUROJUST, EASS and FRONTEX. It is also worth considering that the emphasis across the macro-categories of policy instruments is put on knowledge, not necessarily understood as intelligence-sharing but also as an attempt to develop a cross-national practice of learning and a common state of the art on terrorism affairs.

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this study was to offer fresh empirical insights on the most recent development in the EU security landscape. More specifically, by providing an innovative analysis of the EU strategic thinking in counterterrorism affairs, this paper contributes to the existing debate on the EU security strategy (Economides and Sperling Citation2018, Nitoiu and Sus Citation2019, Szewczyk Citation2021) and counterterrorism approach (Bures Citation2011, Christou and Croft Citation2011, Bossong Citation2012, Monar Citation2015, Argomaniz et al. Citation2017). More specifically, while many have investigated institutional changes (Monar Citation2007, Kaunert and Della Giovanna Citation2010, Argomaniz Citation2011), focusing on the role of agencies for internal (Kaunert Citation2010, Bureš Citation2016) or external security actorness (Wagnsson et al. Citation2009, Kaunert and Léonard Citation2011, Brattberg and Rhinard Citation2012, Ferreira-Pereira et al Citation2016), there is a lack of empirical studies concerning the EU strategic thinking. Hence, this paper sought to contribute to the existing research in a two-fold way. First, by defining strategy as the process of evaluation grounded on existing aspirations and capabilities and initiated to respond to a threat, we provide a framework to empirically evaluate strategic thinking by relying on three categories: (i) threat assessment; (ii) objectives setting and (iii) policy measures. Second, through content analysis, we assess quantitative relevance and qualitative meaning of the three categories in the EU counterterrorism policy formulation between Citation2015 and Citation2020. Beyond the contribution it makes to the literature on counterterrorism, we believe that this framework offers the crucial advantage to see strategy in practice and how it is performed with respect to specific security threats. This issue-specific approach can help better understand broader perceived inconsistencies of European security.

The empirical analysis of the three dimensions of strategic thinking has revealed some mixed results. On the one hand, the documents emphasise the need of a more operative role of EU institutions and agencies in the design of a EU strategic vision. On the other hand, while objectives are clearly presented, the “enemy” that the strategy is supposed to counter remain largely unspecified. In other words, there is no clear consideration of the potential relational aspect of the strategy. Echoing Shelling (Citation1960), what the other could do to nullify the EU strategic options does not appear to be taken into serious consideration. In addition to that, policy measures remain largely vague. In sum, while efforts have been made in clarifying priorities and critical issues to be addressed, the EU seems to be reluctant in developing a clear practical transnational strategy.

Different from other foreign and security issues (Cottey Citation2020), we find that the problem does not necessarily lie on the lack of agreed assessment of the security environment. We found that, although rarely addressed in detail, there was a general convergence on the causes and targets of terrorism across documents and years with much of the emphasis that has been put on processes of radicalisation and the potential risk associated with the youth. We also found that the description of terrorism as a potential source of destabilisation of European democratic equilibria is accompanied by a continuous discussion regarding the democratic constraints for the implementation of counterterrorism measures. Here, we find it interesting to elaborate on the normative content of the strategic discussion that is clear and effective. Indeed, the EU appeared interested in highlighting the concrete relevance of funding principles of human rights and lawful use of force – which represent those unnegotiable values to uphold while developing counterterrorism responses. Safeguarding the rule of law is crucial to EU counterterrorism policy formulation, while this has not always been the case as research on the United States and the Global War on Terror has shown (see, e.g. Mashaw Citation2009).

The main problem our analysis underlines concerns the elaboration of concrete policy measures that remain vague and disperse. Specifically, in order to increase cooperation, coordination and information sharing, the EU has created diverse specialised agencies and promoted the proliferation of several networks and expert groups. However, these initiatives fuelled precisely those information exchange problems they were meant to address. In this respect, the EU counterterrorism strategy appears as an opaque and fragmented set activities which result in a dispersion of efforts. A clear definition of what it really means to counter terrorism for the EU could help reduce such dispersion and shape policy coherence across the Union.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

2 Recently, Duyvesteyn and Worrall (Citation2017) have called for a renewal of the debate within strategic studies.

3 By summing up the results for “terrorism” and “terrorist” categories, the number of references to the terrorism threat equals 1059.

4 European Parliamentary Research Service – The return of foreign fighters to EU soil, 2018, p. 5.

5 European Parliament - Draft report on findings and recommendations of the Special Committee on Terrorism, 2018, p. 4.

6 Council of the European Union – Council Conclusions on EU External Action on Counter-terrorism, 2017, p. 2.

7 Directive (EU) 2017/541 of the European Parliament and of the Council on combating terrorism, 2017, p. 11.

8 European Commission – The European Agenda on Security, 2015, p. 14.

9 European Parliament – Draft report on findings and recommendations of the Special Committee on Terrorism, 2018, p. 4.

10 European Parliamentary Research Service – The return of foreign fighters to EU soil, 2018, p. 5.

11 European Commission – Action Plan to support the protection of public spaces, 2017, p. 2.

12 For a recent study on the Communitarisation of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice see Trauner, F., and Ripoll Servent (Citation2016)

13 Council of the European Union - Outline of the counter-terrorism strategy for Syria and Iraq, with particular focus on foreign fighters, 2015, p. 2.

14 European Commission – The European Agenda on Security, 2015 p. 7.

15 European Commission – The European Agenda on Security, 2015 p. 6.

16 European Commission – The European Agenda on Security, 2015 p. 6.

17 An exception here is the discussion on chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) material as the action plan presented by the European Commission is quite detailed. The relevance in the fight again terrorism remains, however, limited.

18 See https://eucpn.org/

19 See https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/about-ran_en

20 European Commission – The European Agenda on Security, 2015, p. 4.

21 European Commission – The European Agenda on Security, 2015, pp. 8–9.

22 Council of the European Union – Outline of the counter-terrorism strategy for Syria and Iraq, with particular focus on foreign fighters, 2015, p. 3.

References

- Argomaniz, J., 2011. The EU and counter-terrorism: politics, polity and policies after 9/11. Routledge.

- Argomaniz, J., Bures, O., and Kaunert, C., 2017. EU counter-terrorism and intelligence: a critical assessment. Routledge.

- Baker-Beall, C., 2019. The threat of the “returning foreign fighter”: the securitization of EU migration and border control policy. Security dialogue, 50 (5), 437–453.

- Beaufre, A., 1965. An introduction to strategy: with particular reference to problems of defense, politics, economics, and diplomacy in the nuclear age. Frederick A. Praeger.

- Biscop, S., and Coelmont, J., 2013. Europe, strategy and armed forces: the making of a distinctive power. Routledge.

- Bossong, R., 2012. Peer reviews in the fight against terrorism: a hidden dimension of European security governance. Cooperation and conflict, 47 (4), 519–538.

- Bossong, R., and Rhinard, M., 2018. Terrorism and transnational crime in Europe: a role for strategy? In: S. Economides and J Sperling, eds. EU security strategies: extending the EU System of security governance. London: Routledge.

- Brattberg, E., and Rhinard, M., 2012. The EU as a global counter-terrorism actor in the making. European security, 21 (4), 557–577.

- Bryson, J., and George, B., 2020. Strategic management in public administration. In: B. G. Peters and I. Thynne, eds. The Oxford encyclopedia of public administration. Oxford University Press.

- Bures, O., 2011. EU counterterrorism policy: a paper tiger? Farnham: Ashgate.

- Bures, O., 2015. ‘Ten years of EU’s fight against terrorist financing: a Critical assessment’. Intelligence and national security, 30 (2–3), 207–233.

- Bureş, O., 2016. Intelligence sharing and the fight against terrorism in the Eu: lessons learned from Europol. European View, 15 (1), 57–66. doi:10.1007/s12290-016-0393-7.

- Coutau-Bégarie, H., 2002. Traité de stratégie (Economica). Ecole de guerre.

- Chappell, L., Petrov, P., and Mawdsley, J., 2016. The EU, strategy and security policy: regional and strategic challenges. Routledge.

- Christou, G., and Croft, S.2011. European‘security’ governance.1st edition. London: Routledge.

- Čmakalová, K., and Rolenc, J.M., 2012. Actorness and legitimacy of the European Union. Cooperation and conflict, 47 (2), 260–270.

- Council of the European Union. 2015. Outline of the counter-terrorism strategy for Syria and Iraq, with particular focus on foreign fighters. Available from: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5369-2015-INIT/en/pdf.

- Council of the European Union. 2020. Council conclusions on EU external action on counter-terrorism. Available from: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/44446/st08868-en20.pdf.

- Cottey, A., 2020. A strategic Europe. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 58, 276–291.

- D’Amato, S., 2019. Cultures of counterterrorism: French and Italian responses to terrorism after 9/11. Routledge.

- Directive (EU). 2017/ 853. Of the European Parliament and of the Council – of 17 May 2017 – Amending Council Directive 91/ 477/ EEC on Control of the Acquisition and Possession of Weapons. 18. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2017/853/oj.

- Directive (EU). 2017. Of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on Combating Terrorism and Replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA and Amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA, 16. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri = CELEX%3A32017L0541.

- Doyle, R.B., 2007. The U.S. National Security strategy: policy, process, problems. Public Administration review, 67 (4), 624–629.

- Duyvesteyn, I., and Worrall, J.E., 2017. Global strategic studies: a manifesto. Journal of strategic studies, 40 (3), 347–357.

- Economides, S., and Sperling, J., 2018. EU security strategies: extending the EU system of security governance. London: Routledge.

- Engelbrekt, K., and Hallenberg, J., 2010. European Union and strategy: an emerging actor. Routledge.

- European Union. 2016. Shared vision, common action: a stronger Europe. A global strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy. Brussels: EU. Available from: https://europa.eu/ globalstrategy/sites/globalstrategy/files/regions/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf.

- European Commission. 2017. Action plan to support the protection of public spaces. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-security/20171018_action_plan_to_improve_the_protection_of_public_spaces_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2020. A counter-terrorism agenda for the EU: anticipate, prevent, protect, respond. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:52020DC0795&from = EN.

- Ferreira-Pereira, L.C., and Martins, B.O., 2016. The European Union’s fight against terrorism: the CFSP and beyond. Brussels: Routledge.

- Heuser, B., 2010. The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kaunert, C., 2010. Europol and EU counterterrorism: international security actorness in the external dimension. Studies in conflict & terrorism, 33 (7), 652–671.

- Kaunert, C., and Della Giovanna, M., 2010. Post 9/11 EU counter-terrorist financing cooperation: differentiating supranational policy entrepreneurship by the Commission and the Council Secretariat. European security, 19 (2), 275–295.

- Kaunert, C., and Léonard, S., 2011. EU counterterrorism and the European neighbourhood policy: an appraisal of the southern dimension. Terrorism and political violence, 23 (2), 286–309.

- Léonard, S., and Kaunert, C., 2017. Searching for a strategy for the European Union’s area of freedom, security and justice. London: Routledge.

- Kelly, T., 1982. Thucydides and Spartan strategy in the Archidamian War. The American historical review, 87 (1), 25–54.

- Mashaw, J.L., 2009. Due processes of governance: terror, the rule of law, and the limits of institutional design. Governance, 22 (3), 353–368.

- Meyer, C., 2006. The quest for a European strategic culture: changing norms on security and defence in the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Monar, J., 2007. Common threat and common response? The European Union’s counter-terrorism strategy and its problems. Government and opposition, 42 (3), 292–313.

- Monar, J., 2015. The EU as an international counter-terrorism actor: progress and constraints. Intelligence and national security, 30 (2–3), 333–356.

- Nitoiu, C., and Sus, M., 2019. Introduction: the rise of geopolitics in the EU’s approach in its Eastern neighbourhood. Geopolitics, 24 (1), 1–19.

- Pänke, J., 2019. Liberal empire, geopolitics and EU strategy: norms and interests in European foreign policy making. Geopolitics, 24 (1), 100–123.

- Pashakhanlou, A.H., 2017. Fully integrated content analysis in international relations. International relations, 31 (4), 447–465.

- Platias, A.G., and Koliopoulos, K., 2010. Thucydides on strategy: grand strategies in the Pelopennesian War and their relevance today. Columbia University Press.

- Ragazzi, A., Walmsley, A., et al., 2020. J. The European Union and “foreign terrorist fighters” disciplining irreformable radicals? In: D. Bigo, ed. The Routledge handbook of critical European studies. 381–399. London: Routledge.

- Regulation (EU). 2016/794. of The European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) and replacing and repealing Council Decisions 2009/371/JHA, 2009/934/JHA, 2009/935/JHA, 2009/936/JHA and 2009/968/JHA. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:32016R0794&from = EN.

- Rousseau, R., 2012. Strategic perspectives: Clausewitz, Sun-tzu and Thucydides. Khazar Journal of humanities and social sciences, 15 (2), 74–84.

- Schelling, T.C., 1960. The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Schreier, M., 2012. Qualitative content analysis in practice. London: SAGE.

- Szewczyk, W.B., 2021. Europe’s grand strategy: navigating a new world order. Routledge.

- Trauner, F., and Ripoll Servent, A., 2016. The communitarization of the area of freedom, security and justice: why institutional change does not translate into policy change. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 54, 1417–1432.

- Tsakiris, T.G., 2006. Thucydides and strategy: formations of grand strategy in the history of the Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 B.C.). Comparative strategy, 25 (3), 173–208.

- Wagnsson, C., Sperling, J., and Hallenberg, J., 2009. European security governance: the European Union in a Westphalian World. 1 edition. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Winn, N., 2019. Between soft power, neo-Westphalianism and transnationalism: the European Union, (trans)national interests and the politics of strategy. International politics, 56 (3), 272–287.

Appendix

Table A1 . List of documents.