ABSTRACT

Sanctions have become the “go to” mechanism for addressing foreign and security challenges in the international arena. The European Union’s willingness to impose autonomous (or unilateral) restrictive measures on third countries, and in particular on Russia, has come to the fore at a time when the uptake of new sanctions through the United Nations (UN) framework has stalled. This trend appears to reflect a growing ability to forge consensus among the EU's Member States and use its economic power to support its foreign policy goals. This article considers the extent to which the EU has succeeded in forging a leadership role in sanctions for itself among non-EU states. It examines the alignment or adoption by non-Member States with its sanctions regimes and finds that the EU has a demonstrable claim to regional, if not yet global, leadership.

Introduction

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022 brought into sharp focus the reaction of the European Union (EU) and its Member States to an armed conflict on its doorstep. Immediate attention pointed to sanctions as the most practical, rapid and meaningful response possible by the EU. EU sanctions on Russia and its ally Belarus were imposed with remarkable speed via the EU's system of governance, adding to existing sanctions regimes in place on both countries since 2014.

The speed with which the EU was able to turn words into actions may have been a surprise to those accustomed to the common view that the EU's foreign policy lacks assertiveness. But the use of sanctions (or “restrictive measures” as they are officially termed in the EU) does not come as a surprise to those following the recent trajectory of EU foreign policy, particularly since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. This is partly due to the institutional capacity tied with political will to use sanctions, but also because sanctions have over the past few decades become a “go to” tool in international relations.

In the 1990s, sanctions on third countries were primarily imposed through a multilateral framework via a resolution of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). The uptake of UN sanctions has largely stalled in the past decade, since UNSC permanent members have been unable to reach decisions on a series of pressing global security challenges (on, for example, Syria, Venezuela, chemical weapons, cyber security and human rights) (Moret Citation2021). They have also subjected one another to their own autonomous sanctions and countersanctions since 2014 (Moret et al. Citation2017, Parry Citation2021) which largely prevents the UNSC from playing a central decision-making role on sanctions in the near future at least. More generally, there has been a marked increase in the use of autonomous (or “unilateral”) sanctions by the EU, the US and others. An estimated quarter of the world's population live in countries subject to some form of sanctions by other states (United Nations Citation2018) though sanctions can be highly varied in their content, scope and effects on the population at large.

The extent to which unilateral sanctions imposed by the US have been followed by other states has been documented by studies (e.g. Taylor Citation2010, Moret and Pothier Citation2018) which find evidence that the US stands out as the originator of unilateral sanctions that are more likely to influence others to adopt. However, the instances where the EU has imposed its own unilateral sanctions, and whether other non-EU states follow its lead, is much less documented (see Cardwell Citation2015, Citation2016, Szép and Van Elsuwege Citation2020). The purpose of this article is to assess the extent to which the EU has succeeded in establishing itself as a leader in sanctions beyond its borders by examining when and how non-EU states have adopted the same sanctions. The article looks at the practice and process of inviting selected third countries in the EU neighbourhood to align with EU sanctions and the extent to which other states appear to follow EU practice in an explicit or implied manner.

We argue that the evidence demonstrates the EU has been largely successful in providing leadership in imposing sanctions that other, non-EU states have followed. Although the instances of alignment vary across the wide range of non-EU states invited to align, the EU has a legitimate claim to be a regional “leader”. Beyond Europe, there is some initial evidence that the EU might be able to claim that it is showing signs of global leadership too.

These concepts and terms are defined further in the following sections alongside a description of shifting international and EU sanctions practice and the legal-political processes surrounding their use (Parts 1 and 2). Part 3 then proceeds to examine the impact of the EU in influencing states within the EU's neighbourhood.

Part 1: The EU and “leadership”

Studies that analyse the dramatic rise of sanctions use outside the UN framework highlight the leadership role played by the United StatesFootnote1 in setting the global agenda across a range of country- and thematic-based sanctions regimes (e.g. Harrell Citation2018, Moret Citation2021). One study estimates the US employed some five times more sanctions than the UN and double that of the EU in the period between 1990 and 2015 (Attia and Grauvogel Citation2019). In this vein, the EU, along with others including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea and now post-Brexit UK,Footnote2 is generally understood to follow the US's lead to varying degrees (Moret and Pothier Citation2018). Nevertheless, notable divergence has occurred in relation to the sanctions policies employed under different US administrations and in relation to different targets, including those in Latin America (Keatinge et al. Citation2017) and in relation to former President Trump's highly critiqued “Maximum Pressure” campaign (Foreign Affairs Citation2019).

The EU has also seen its own willingness and ability to expand its use of restrictive measures increase via a decision-making process that has become institutionalised within the EU's legal order (Cardwell Citation2015). Though the focus of this article is not on the effectiveness of sanctions as a foreign policy tool, it is axiomatic that additional states adopting similar sanctions would increase their overall impact.

Recent literature has examined some of the ways in which the EU's Treaty-based mission to engage in a leadership role in international relations and promote its values have been successful (Aggestam and Johansson Citation2017, Aggestam and Hedling Citation2020). However, the notion of leadership, and, as a counterpart, the notion of followership (Cooper et al. Citation1991, Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien Citation2012, Uhl-Bien et al. Citation2014) remains largely absent from the sanctions literature. We analyse the extent to which the EUFootnote3 has both developed and obtained support for such policies from non-EU countries through the practice of sanctions alignment and adoption.

In this article, we define leadership as the process through which third countries align with, or adopt, sanctions measures originating in the EU. We distinguish alignment from adoption: alignment refers to the process by which selected third countries are invited to publicly state that they are following restrictive measures. Adoption does not entail a specific public statement that the third country is following the EU's lead (though this is possible), but, instead, where there is sufficient similarity and consequential timing. While the former is quantified over the period under examination in this article via the EU Declarations listing those countries having aligned, the latter poses a methodological challenge to establish the precise extent of the EU's leadership. As a means of surmounting this challenge, we look at a selection of European countries and patterns in sanctions adoption, as well as evidence of where other countries or groups appear to have followed the EU's lead.

Since our research question centres on leadership, our conceptual framework requires consideration of existing scholarly approaches to leadership. We identify four principal approaches in the literature (including in Young Citation1991, Grint Citation2005, Parker and Karlsson Citation2014, Helwig Citation2015, Aggestam and Johansson Citation2017). First, leadership as based on the personalities of individual leaders, linked to knowledge, skill, power and resources (Aggestam and Johansson Citation2017; see also Helwig Citation2015). Second, leadership as based on a given position (which releases the resources necessary to lead), which can be divided into formal and informal leadership (Nye Citation2008). Third, leadership as a process, marked by the study of behaviours and practices utilised by an actor “to influence others to adhere to collective goals, decisions and desired outcomes” (Avery Citation2004, quoted in Aggestam and Johansson Citation2017, p.1026). Fourth and finally, leadership as based on results and outcomes (Grint Citation2005).

Although all four approaches could reveal the ways in which the EU engages with third states and groups in ensuring the maximum impact of its sanctions, we recognise the interconnectivity and context-specific nature of the enquiry (see also Byman and Pollack Citation2001, Aggestam and Hedling Citation2020). However, the fourth approach, leadership-based results and outcomes, is the one adopted in this article. The premise of this approach is that leadership can be found via evidence where the adoption of a set of norms or practices by one actor is visible in the actions of another actor.

As such, we look for evidence that EU sanctions measures and regimes are followed by third countries via both alignment and adoption. Like Aggestam and Johansson (Citation2017) and Parker and Karlsson (Citation2014), our understanding of leadership as a process is made up of four parts: (1) a leader (in this case, the EU as a polity); (2) followers (non-EU European countries); (3) the activity of leadership (influencing and guiding third countries to adopt a similar sanctions approach to the EU); and (4) the leader's objectives in the outcome of sanctions emanating from the non-Member State.

We recognise that different types of leadership are in play in EU sanctions alignment, and that other models would be able to better take into account the motivations of both the EU (and its Member States) and the partner in adopting particular positions, and how these differ depending on the target in question, and what the effect of taking the course of action might be (on the partner, and the target). Our choice of a leadership framework based primarily on outcomes is that we are looking for evidence of where such results are, in least in part, quantifiable.

The reasons why third states may adopt or align with the EU's sanctions over a longer period of time are also likely to be complex, varied and beyond the scope of this study. We equally recognise the limitations of an approach focusing on leadership, when followership (e.g. third state motivations in EU sanctions alignments) is as important as understanding the phenomenon (e.g. actions taken by the EU to encourage alignment) (see, for example, Uhl-Bien Citation2014 for such a focus).

Here, we draw on Grint’s (Citation2005) assertion that “leadership involves the social construction of the context that both legitimates a particular form of action and constitutes the world in the process”. In our, this relates to the regular adoption or alignment of sanctions by third countries and what this tells us about the extent to which the EU can create a context where sanctions are viewed by third parties as appropriate measures. Furthermore, since sanctions are a tried and tested means for the EU to express, in concrete terms, the development of its own foreign and security policy, the social construction of a global order where the EU is an actor beyond its borders takes shape. The following section outlines the way in which EU sanctions are employed, and the process of alignment and adoption by third countries.

Part 2: The policy and practice of EU restrictive measures

In many ways, sanctions provide the answer to the conundrum that has plagued the EU since express EU competence in foreign and security policy was granted in the Treaty on European Union (Treaty of Maastricht) in 1992. Namely, how can the EU gain a political voice that matches its growing economic weight? Sanctions have provided an opportunity to go beyond rhetoric and attempt to showcase the EU's foreign policy in action (Portela Citation2010). The EU’s Global Strategy (2016) was an attempt to forge a renewed, strategic voice for EU foreign policy in the twenty-first century. It noted that:

Restrictive measures, coupled with diplomacy, are key tools to bring about peaceful change. They can play a pivotal role in deterrence, conflict prevention and resolution. Smart sanctions, in compliance with international and EU law, will be carefully calibrated and monitored to support the legitimate economy and avoid harming local societies. (Council of the EU Citation2016, p.32)

The second category is autonomous (or unilateral) sanctions, which supplement (or build on) existing UNSC sanctions. There are ten such regimes in force (as of 2021), including targets in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Guinea-Bissau, Libya, North Korea (the Democratic Peoples’ Republic of Korea (DPRK)), South Sudan, Sudan and terrorism (in connection with groups that include ISIL/Daesh and Al-Qaida).

The final group is fully autonomous sanctions imposed by the EU outside the UN framework. Representing the largest category for the EU, this group of 25 includes country-based restrictive measures on targets in Russia, China, Syria and Venezuela, as well as those imposed against thematic (or horizontal) targets linked to terrorism,Footnote5 and more recently those addressing the illicit use of chemical weapons, cyber-attacks and human rights abuses.Footnote6

Sanctions have become the response through which the EU seeks to influence or pressure targets in a third state, including through coercing a change of behaviour, constraining access to vital resources, signalling disapproval of particular activities or stigmatising a particular target (Giumelli Citation2010). The target in a third state may be the current or previous government (whether officially recognised or de facto) and those connected to it, such as in industry. They can also be used to exert influence between major powers (Taylor Citation2010) or put off would-be detractors from committing future misdemeanours. Restrictive measures might cover economic activity, travel bans or asset freezing on individuals or corporate actors. The imposition of sanctions on Russia since its annexation of Crimea in 2014 has, in particular, highlighted both the willingness and consensus of the EU to use the tools at its disposal, while also putting diverging interests of different Member States under a spotlight (Moret et al.Citation2016, Sjursen and Rosén Citation2017, Portela et al. Citation2020).

The EU's autonomous sanctions tend to differ in focus from those imposed through UNSC resolutions. The UN has typically focused its sanctions on the promotion of international peace and security (especially combatting violent conflict), whereas the EU has also focused on matters such as the promotion of democracy and human rights (Charron and Portela Citation2016) as a means of reflecting its treaty-based values (Cardwell Citation2016). Over time, the EU has started to use broad sectoral autonomous sanctions targeted against finance and energy sectors with more frequency (marking a move away from more strictly targeted measures), as was the cases with Iran, Libya and Syria (Charron and Portela Citation2016, Boogaerts Citation2018, Jones and Portela Citation2020). These types of sanctions have been associated with negative unintended humanitarian concerns, as they tend to affect a broader swathe of the population (Moret Citation2015). The EU's sanctions also continue to attract critical comments as to their effectiveness, especially as long-term restrictive measures can start to lose their effects on the intended targets (see, for example, Fabre Citation2018, Eckes Citation2020, Druláková and Zemanová Citation2020).

The EU's institutional configuration and legal complexity in foreign policy, where Member States retain a key role via the Council (Szép Citation2020), can result in the haphazard imposition of sanctions. The initial failure to agree additional sanctions on Belarus in 2020 due to the opposition of one Member State, Cyprus, illustrates this point (though additional rounds of measures were later agreed in 2021). On the other side of the coin, the EU has demonstrated an ability to arrive at decisions on sanctions at an unprecedented speed, such as those imposed against Iran and Syria since 2012 (Moret Citation2015). The same applies to the EU’s ability to maintain unity on even the most divisive of sanctions, such as those on Russia since 2014. Since it is to be expected that retaliatory sanctions will be put in place by some targeted states (see Kalinichenko Citation2017 on Russia, or Parry Citation2021 on China), doing so to a large, economically-significant state risks significant costs, including to export markets.

Imposing autonomous sanctions outside the UNSC framework remains controversial for international lawyers (Marossi and Bassett Citation2015, Beaucillon Citation2021) though as Ridi and Fikfak (Citation2022) have noted, they are more embedded in international law than often assumed. In a similar vein, the UN Human Rights Council, Resolution 27/21 of 3 October 2014: stated that “unilateral coercive measures and legislation are contrary to international law”. All nine EU members sitting in the Council (plus EU membership candidates Montenegro and North Macedonia) voted against the resolution, along with the US and Japan. Nevertheless, the resolution called on all states “to stop adopting, maintaining or implementing unilateral coercive measures not in accordance with international law” (Resolution 27/21, article 1). The EU's letter to the Committee prior to the resolution stated:

“[t]he introduction and implementation of European Union restrictive measures must always be in accordance with international law. They must respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, in particular due process and the right to an effective remedy. The measures imposed must always be proportionate to their objective. This is in line with the EU's Guidelines on implementation and evaluation of restrictive measures (sanctions) in the framework of the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy.” (European Union Permanent Delegation to the UN in Geneva Citation2014)

In this respect, the way in which the EU has sought to develop and deploy sanctions underlines its view, as expressed in the Global Strategy, that sanctions are a “key tool” in foreign policy and one where it is forging a distinctive path as a non-state actor. This distinctiveness can also be located in the ways in which the EU has sought to exhibit leadership, to which discussion now turns.

Part 3: Locating and assessing EU leadership in sanctions

Given that the process of imposing autonomous sanctions already requires the consensus of 27 Member States, the extent to which the EU has employed the policy instrument is a mark of success in coordinated decision-making. The focus of this part of the article is how to identify where non-EU states have imposed substantially similar sanctions. This part first examines alignment, i.e. the group of states in the EU neighbourhood that are specifically invited to adopt the same sanctions on a particular target as the EU. The discussion then turns to the adoption of sanctions by other, non-EU states that do not fall into the above categories (including Switzerland and the UK) and, finally, where evidence might be found geographically further afield for EU sanctions leadership.

Exploring alignment with EU sanctions in the neighbourhood

Since 2007, the EU has established a consistent practice of inviting selected European neighbouring states to align with foreign policy Declarations. Declarations which relate to sanctions regimes account for between one-quarter and one-third of the total number of Declarations issued by the EU since 2007 (for analysis, see Cardwell Citation2016). This group of countries comprises non-EU European Economic Area (EEA) states (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway); those in the enlargement/pre-enlargement process (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia [before its EU accession in 2013], North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey) as well as others covered by the EU's Eastern Partnership (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine).Footnote7

The terms “align” and “alignment” are not defined in international or EU law but are used by the Council to denote the countries that have accepted the invitation on a case-by-case basis. It is therefore the “official” benchmark used here to signify public willingness of a third country to adopt similar measures to the EU's sanctions against a target. The countries that decide to align are publicised by the Council, either by listing a CFSP Declaration or via a press release. Declarations do not in themselves have a legal effect on either the EU Member States or the third countries.

Declarations on sanctions confirm that the third state has adapted its national law and foreign policy to incorporate the EU's measures, though the EU is neither in a position to check or enforce whether actual legislative or policy changes have taken place. They are also not in a position to verify the extent to which the third state has effectively enforced the sanctions in question.

The origins of this practice of alignment lie in the EU enlargement process. The thirteen states (all in Central and Eastern Europe, with Cyprus and Malta) that joined in 2004, 2007 and 2013 were invited to align in preparation for their eventual participation in EU foreign policy. The practice was then extended to other potential future members, and those with a desire for closer integration with the EU were invited to align, alongside those with whom the EU already has strong relations, namely Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. The practice became more consistent and regularised in the mid-2000s and invitations to align with CFSP Declarations and sanctions were offered to Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia in mid-2007. Extending the invitation to other neighbourhood partners in the Mediterranean, including Morocco and Jordan, was raised in the Council in 2007, but has not materialised (Council of the EU Citation2007). The positions of Switzerland and post-Brexit UK are considered separately below as they are not part of the alignment process.

Fourteen states are currently offered the opportunity to align via this procedure. They have no formal role in the EU's decision-making process and whether a state opts to align is a domestic political decision. There is no legal obligation for them to do so, though since EU restrictive measures form part of EU law (the “acquis”), the countries in the enlargement process should align as part of their general obligation to bring their legal systems into line with that of the EU (Hellquist Citation2016, Citation2019; Szép and Van Elsuwege Citation2020). In the past, this was an unproblematic and uncontroversial aspect of the enlargement process (Baun and Marek Citation2010) since the number of sanctions regimes was lower and politically less contentious as most sanctions applied to smaller, far away states with a low impact on bilateral economic relations. However, the imposition of sanctions on Russia since 2014 has proved more divisive among candidate states (see further below).

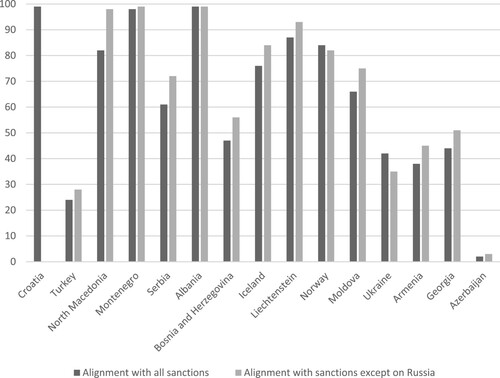

The alignment process enables quantitative evaluation. shows the respective rates of alignment by invited states on all sanctions imposed by the EU between January 2007 and December 2020, excluding those concerning Russia (to enable a comparison that is not skewed by the more anomalous results of Russian sanctions alignment). Only aligned states mentioned in the EU's announcement are included.

In total, 302 Declarations were issued during the period under examination relating to one of the 32 sanctions regimes in force. shows that most states aligned with between 60% and 90% of Declarations during the period. The rates of alignment with sanctions vary considerably across the third states. Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania and Liechtenstein aligned themselves with 90–99%; Iceland and Norway with over 80%; Serbia and Moldova with over 70% and Turkey, Armenia, Georgia and Bosnia and Herzegovina aligned at a rate of between 40% and 50%. Azerbaijan aligned itself with approximately 5% of sanctions, which occurred only during a short period of several months in 2007 and on sporadic occasions until 2012.

The countries having aligned most frequently with all sanctions are Croatia (from 2007 until its accession in 2013), Albania and Montenegro. Occasions, where these three were not listed as aligning states, are rare. Croatia missed only one of 119 opportunities to align. Albania failed to align on only three occasions out of a total of 300, the last time being in 2011; and Montenegro five times, the last time in 2014. In all of these instances, the partner state had aligned with all the other sanctions Declarations relating to the target country, and little can be learned from these sporadic instances. The 2020 Commission enlargement reports for Albania and Montenegro commended their continued 100% alignment during more recent years (European Commission Citation2020a, Citation2020b). At the same time, new domestic legislation in Albania provided an updated legal basis for EU and UN sanctions, thus facilitating the process (European Commission Citation2020a) and boosting Albania's bid for a non-permanent UNSC seat in 2022–2023.Footnote8

The picture for other states in the enlargement process is mixed. North Macedonia from 2007 to 2014 had an almost 100% alignment record but did not align between 2014 and 2020 with the restrictive measures on Russia or Transnistria. However, it did align with sanctions on Turkey. The ongoing nature of measures on Russia and the lack of alignment with adjustments to the sanctions regime has led to a drop in North Macedonia's overall alignment rate. The Commission’s 2020 report notes that the country was “moderately prepared” in its adoption of the EU acquis in foreign, security and defence but that improved alignment with sanctions should be a specific goal of the government (European Commission Citation2020d).

It is more challenging to identify patterns in Serbia's alignment. Overall, it has aligned with approximately 50% of the total number of CFSP decisions on sanctions, and like North Macedonia, had a very high rate until 2014. However, unlike North Macedonia, the drop in its alignment cannot only be explained by reticence to align with sanctions on Russia. Serbia has not aligned with sanctions on Belarus, Libya, Nicaragua or Venezuela, and its alignment with other sanctions regimes, such as the DRC, is patchy. In the context of enlargement, the 2020 report on Serbia suggests that the 60% alignment rate of the previous year represented unsatisfactory progress in integration with the CFSP and thus “Serbia needs, as a matter of priority, to make additional efforts regarding its alignment with the EU CFSP” (European Commission Citation2020c).

Turkey has aligned with 40% of sanctions in total since 2007, with the majority taking place before 2013. Turkish accession negotiations began in 2005 but have not progressed substantially. Its rate of alignment varied over this period but was never as high as other accession countries; as also noted in the annual enlargement reports (e.g. European Commission Citation2012). But, given the long timespan of Turkey's accession bid, it remains formally at a very early stage of the process. With this in mind, Turkey should not necessarily be seen in the same context as the other enlargement states which have a more realistic prospect of membership in the short- to medium-terms.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is officially a “potential candidate” for EU membership and invited to align with Declarations.Footnote9 Its overall rate of alignment of around 50% masks three very distinct phases. From 2007 to 2011, it aligned with almost all sanctions, except those on Libya. From mid-2011 until 2014 there were stretches of several months where there was either no alignment at all or almost full alignment. Since 2014, the rate of alignment bears close resemblance to that of Serbia. Bosnia and Herzegovina has not aligned with sanctions on Russia or Belarus, though it did align with those on Iran, Libya and countries in Africa. While the motivations for this mixed record are outside the scope of this study, Bosnia and Herzegovina appear to offer an example of some of the limits of EU leadership in sanctions practice over some of its close neighbours.

The Commission's enlargement report on Bosnia and Herzegovina points to the weak governance structures in place despite a broad commitment to EU foreign policy goals (as contained in the Global Strategy 2016). As well as the divergent positions of the three members of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the report points to the lack of Foreign Ministry personnel ‘in charge of performing the functions of “political director” and of “European correspondent” and the negative impact of the “Regulations and practices based on ethnic quotas, applied in the process of appointment of diplomatic and consular network … on the implementation of the overall country's foreign policy objectives” (European Commission Citation2020e).

Iceland's rate of alignment was approximately 50% between 2007 and 2009, with two consecutive stretches of alignment followed by non-alignment. Iceland submitted an EU membership application in July 2009 and started accession negotiations in 2010. The foreign, security and defence chapter of the acquis was closed in 2012, signalling that Iceland's compatibility with CFSP was complete and, by consequence, that 100% alignment was thus no longer a formal requirement. However, Iceland notified the Commission that it no longer wished to be considered a candidate country in March 2015, though it did not formally withdraw its application. Nevertheless, it has aligned with all EU sanctions except for those on Russia since 2014. This, as Thorhallsson and Gunnarsson (Citation2017) explained, was a deliberate policy choice: Iceland adopted measures similar to those of the EU on Russia (despite opposition from the domestic fishing industry) but without formally aligning itself with the EU or the US. As such, it can be seen to have demonstrated “token autonomy” as a result of balancing “domestic material interests represented by the powerful fisheries lobby, and the foreign policy preferences of its powerful protectors and allies” (Thorhallsson and Gunnarsson Citation2017, p.318).

Norway's alignment rate has traditionally been high, and its alignment includes the sanctions regimes on Russia, but not Venezuela, Turkey or targets on the terrorism list. Like Iceland, Norway's close cooperation with the EU has come under domestic scrutiny as the number of instances of EU sanctions has increased, thus posing questions of “constraints and influence” of the EU on Norwegian foreign policy (Hillion Citation2019, p.32).

Between 2007 and 2014, Liechtenstein aligned with every sanctions Declaration. Since then, its alignment closely mirrors that of fellow EEA-EFTA member Iceland: it did not align with EU sanctions on Russia 2014–2020, nor the chemical weapons list. It has aligned with only some sanctions Declarations relating to Libya and Turkey. However, it has imposed its own unilateral sanctions in these cases (including on Russia) and updated them soon after the EU adjusted its own. Therefore, this is an example of where there is express alignment but also de facto adoption of EU sanctions too on certain issues or targets.

Amongst the remaining countries of the Eastern Partnership, Moldova and Ukraine show similar levels of alignment. They differ on sanctions on Russia, where (unsurprisingly) Ukraine aligns but Moldova does not. Armenia and Georgia have similar rates of alignment to each other but rarely on the same measures. Armenia does not align with sanctions on Russia, Belarus or Syria but has consistently aligned on Libya and Myanmar. Its rate of alignment has dropped since 2019, however, it has aligned with sanctions on Turkey. Georgia's rate is perhaps surprising, given the importance it has attached to its Association Agreement with the EU. However, it has aligned with approximately the same frequency throughout the period, and most consistently on Syria, the terrorism list and former sanctions on Côte d’Ivoire and Zimbabwe.

Azerbaijan aligned with some Declarations during a short period of several months in 2007, following the invitation by the EU to do so. Azerbaijan aligned most consistently on Myanmar/Burma but has only aligned sporadically since 2007 for the restrictive measures on individuals suspected of terrorism. The last occasion of alignment was in 2012. Azerbaijan can thus be understood to be outside the scope of the “aligning” neighbourhood countries and the only partner state with which the EU has not established a leadership role.

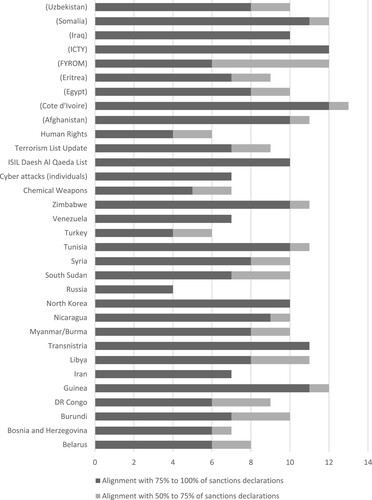

shows the variation in alignment according to the sanctions themselves, all of which have been in force for all or part of the period between 2007 and 2020. Although states that align on a particular target country tend to do so consistently, the patterns can be sporadic over the time under examination. shows the more general patterns of alignment, which accounts for general trends. This includes where alignment has been partial, or where there may be some alignment but the state has not publicly committed itself to doing so when invited by the Council via the Declaration. The failure to publicly align via a Declaration issued soon after the invitation does not necessarily indicate that a state is not imposing sanctions. Rather, this may be due to domestic factors, including a change of government. Therefore, overall trends are more indicative of the potential for the EU's leadership rather than individual instances.

Figure 2. Number of invited states aligning with EU sanctions 2007–2020 (those in brackets no longer in force).

shows that in no instance has the EU failed to attract the alignment by at least four additional states, with an average of some seven additional states aligning. In reality, this means that EU-led sanctions would be applied by the EU Member States (27 or 28, pre-accession of Croatia (i.e. until 2013), or pre-Brexit (i.e. until 2020)) plus others, totalling around 35 countries on average (or, around 20% of the 193 members of the UN).

These results suggest that the EU has been particularly effective in gaining the alignment of the invited countries with measures taken against countries in Africa (including Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea-Bissau), Syria and Myanmar, and, more recently, Venezuela. It has been less successful in gaining alignment with the measures taken against Russia following its annexation of Crimea in 2014, where the states did not include Serbia, Moldova and the three states in the Southern Caucasus (among others), even if some supported UN General Assembly resolutions “recalling Ukraine's territorial integrity”. With fewer aligning themselves with restrictive measures against Russia, the overall level of alignment has dropped since 2014. The same rationale applies for some states nervous about contradicting Russian policies, which have differed sharply from those of the EU, such as those toward Libya. As Hellquist (Citation2016, p.1001) explains “alignment instrumentalizes neighbours for the EU's purpose of increasing international posture. By aligning, third countries agree to enter a state of antagonism with a large share of the world's countries”.

The adoption of EU sanctions by third countries rests on a political evaluation of both adopting the sanctions as a (national) foreign policy measure, and the consequences of aligning itself publicly with the EU. For states in various stages of the enlargement process, a decision not to align might figure in future evaluations of the state's readiness to join the EU, particularly if it was at a late stage. This signals that the EU may only be capable of exerting sanctions leadership at certain times over neighbouring states. However, this is largely untested, since the only state to successfully join the EU since this practice began, Croatia, had close to 100% alignment with EU sanctions in the years proceeding its accession. As the discussion above demonstrates, a candidate state that has failed to align consistently with sanctions on a particular issue might expect this to be a matter of contention in the enlargement process. Whilst it is tempting to suggest that the alignment is exclusively motivated by a shared desire to advance the enlargement process, analysis by Marošková and Spurná (Citation2021) paints a more complex picture in contrasting Montenegro and Albania's foreign policy synergy with the EU. They suggest that Montenegro's high alignment was explicitly linked to the fulfilment of its social role as a candidate country. A significant pro-Russia section of society and the political system suggests a lack of normative resonance with the EU's sanctions. Their analysis does not show there is any specific incentive relating to sanctions as the main motivating factor. Conversely, their analysis finds that Albania's political identity clearly suited sanctions alignment with the EU, as the sanctions resonate with its foreign policy and an animosity towards Russia. Hence, full alignment with the EU on sanctions and foreign policy might be the product of more complex reasoning than merely accepting a particular role.

Overall, if sanctions related to Russia are removed from the equation, then the general level of alignment with EU autonomous sanctions is higher. In this respect, the practice of alignment can be understood as a success and as evidence of EU leadership among most members of the selected group. The exceptions are Azerbaijan, with a very low level of alignment, and Turkey, where the overall rate has dropped significantly over time. It also suggests that leadership success rates may decline when more politically – or economically – contentious countries, such as Russia, are the target of the sanctions.

Looking across the data from each of the aligning states, the position within the enlargement process is only partly helpful as an explanatory factor. Recalling that leadership, in the theoretical frame adopted here, rests on results and outcomes, the EU can be conceptualised as a successful leader of sanctions in the immediate neighbourhood.

Beyond alignment: leadership and other European states

Firm evidence is more difficult to obtain in terms of other non-EU, European states who fall outside the group of “invitees” covered in the previous section. Nevertheless, these states do impose their own unilateral sanctions, and therefore a comparison of the synergy with the EU's sanctions regimes is possible in terms of understanding whether the EU demonstrates leadership here too, although it is not possible to use the same methods as above. This section provides an analysis of the two largest states in Western Europe that do not fall within the alignment practices above. Switzerland has been the key historical example, which has been joined more recently by the UK, following its departure from the EU on 31 January 2020.

Switzerland tends to adopt a similar set of targeted sanctions to the EU in many cases. As set out by the Federal Law on the Implementation of International Sanctions of 22 March 2002 (or the Swiss Embargo Act [EmbA]), Switzerland is only permitted to impose autonomous measures employed by the UN, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) or other major trading partners, such as the EU. The act grants autonomy to the Federal Council to make decisions on the extent to which Switzerland might adhere to any third-party regime, be it in full, partially, or not at all (Embassy of Switzerland in the United Kingdom, Citation2017). Like other non-EU countries in Europe, Switzerland is not involved in the decision-making process linked to new or existing EU restrictive measures, but nevertheless makes use of diplomatic channels regarding implementation and enforcement. Historically, it has tended to adopt approximately half of the EU's autonomous sanctions, including those against Syria, Myanmar, Belarus, Libya and Venezuela (Embassy of Switzerland in the United Kingdom, written evidence, Select Committee on the European Union, External Affairs Sub-Committee, ‘Brexit: Sanctions Policy’ Citation2017). It opted to only adopt a small number of supplementary autonomous EU sanctions against Iran (avoiding measures against the Iranian Central Bank and oil sector) that supplemented UN sanctions in light of Switzerland's role a “protecting power” of US consular and diplomatic interests in Iran. The same also occurred with regard to the EU's sanctions on Russia from 2014 onwards, reportedly due to sensitivities linked to Switzerland's role as Chair of the OSCE, which afforded the country a mediator function in the early stages of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2014 (Embassy of Switzerland Citation2017).Footnote10

As stated by a Swiss government source

the Federal Council takes into consideration all relevant legal, foreign policy and foreign economic policy considerations. As a European nation, Switzerland shares the basic values of the European Union and mostly concurs with its political and legal analysis as well as with its objectives in particular contexts. (Embassy of Switzerland Citation2017, p.1)

EU sanctions were applied by the UK during its EU membership and until the end of the Brexit transition period (31 December 2020). The UK passed the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018, which is the post-Brexit domestic legal basis for sanctions. The Political Declaration agreed between the EU and the UK pre-Brexit notes that, “[w]hile pursuing independent sanctions policies driven by their respective foreign policies, the Parties recognise sanctions as a multilateral foreign policy tool and the benefits of close consultation and cooperation” (UK Government Citation2019).

Formal alignment of the UK with EU sanctions is thus not a possibility on the current terms. The extent to which the substance of the UK's future sanctions regime will mirror that of the EU has been questioned, (Cardwell Citation2017, Szép and Van Elsuwege Citation2020). The UK's ability to exert a leadership role in European sanctions policy after its departure from the bloc is similarly questioned (Moret and Pothier Citation2018), suggesting that the most likely scenario will be a form of informal cooperation along the Swiss model (as a “follower”, or “tracker”, adopting similar measures on a voluntary basis without a formalised say over their design). The key difference with Switzerland is that the UK will also be able to enact its own autonomous measures without needing to work in conjunction with major trade partners (as is also more recently the case in Canada). The Foreign Secretary has said that the UK-only sanctions regime will work with allies, including the US, Canada, Australia and the EU (Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) (UK) Citation2020).

To date, the UK's sanctions have been imposed in close coordination with these partners, including in relation to Belarus,Footnote11 where it imposed (in close succession to one another) similar sectoral measures to those adopted by the EU, US and Canada, as well as Switzerland. It has gone further than the EU in enacting a new thematic corruption sanctions regime (UK 2021 Global Anti-Corruption Sanctions Regulation), similar to those adopted in Canada and the US. The Brexit “trade-off” is that the UK may be able to act quickly and without the risk of institutional blockage in the EU in case it wishes to impose sanctions – but with the risk of a lower level of effectiveness. Given that there is little evidence to suggest that the UK has opposed EU efforts to sanction a country or experienced a divergence in foreign policy values, it seems the most likely scenario is that UK and EU sanctions will be similar in form and content. The UK is unlikely to admit that it has “followed” EU sanctions, due to the need to reinforce the image of post-Brexit “Global Britain” but it now lacks the opportunity for institutional cooperation to claim that it is a leader if it imposes sanctions before the EU.

The extent to which EU leadership in sanctions beyond the European neighbourhood is visible presents numerous methodological challenges. First, the priority for the EU in imposing or amending sanctions is to seek agreement between the Member States. Therefore, until this stage is reached, there cannot be meaningful dialogue with other states or organisations that might be inclined to follow the EU's lead and adopt similar measures (see Hillion Citation2019). Further research is also required to better understand the (already close) interaction between the sanctions practices of the EU and other regional organisations such as the Africa Union and League of Arab States. Furthermore, there is a case for suggesting that the alignment opportunities afforded to European, non-EU members could be extended to other states: for example, neighbouring states in the Middle East and North Africa, or further afield. Whether any other states would opt to do so to the extent visible for the current alignment invitees is an open question and many lack appropriate legislation or capacity to adopt similar measures.

However, there is some evidence that autonomous EU sanctions may be coordinated with other governments and regional organisations through a range of formal and informal channels.Footnote12 In the case of the EU's sanctions on Syria, they were first employed at the request of the Arab League, for example (Moret Citation2015), in a nod to the significant weight of Syria-EU shared trade prior to the onset of fighting, as well as the EU's already established and active role as a sanctioning power operating in the European neighbourhood (Portela Citation2017).

The second major challenge is the secrecy involved in the negotiations, especially when coordination relies on informal challenges. Requiring greater transparency would potentially undermine, for instance, the need to ensure that sanctions targeting individuals do not come after such individuals have made arrangements to protect their assets. Nevertheless, the ability of the EU to agree and impose a wide range of sanctions has laid the groundwork for the social construction of an international space where it is itself a major actor.

Conclusion: evaluating EU sanctions leadership

There is little doubt that the ability and willingness of the EU to impose sanctions on third countries has become central to its desire to translate the aspirations of the Treaty for an EU foreign policy into reality. Although the potential contours of a military angle in the EU's response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 were brought to the fore in an unprecedented manner, sanctions nevertheless remained the main foreign policy tool at the EU's disposal.

In the EU context, sanctions provide the opportunity to forge a link between the EU's economic strength and its foreign policy. The evidence from the European neighbourhood shows that, despite varying levels of formal alignment across most invited countries, EU sanctions can be accurately described as European sanctions given their widespread application by non-EU member states on the regimes in force. In this respect, the EU begun to effectively fulfil its Treaty-based mission to export its foreign policy norms to third countries. As a result, all EU sanctions regimes count not only the 27 Member States of the EU, but on average 6–10 further states who have explicitly aligned themselves.

To recall the conceptual framework set out earlier, we argue that a focus on leadership in terms of outcomes and results demonstrates that the EU has largely succeeded in this goal. We find that those relationships marked by more formalised structures (e.g. accession countries) tend to show higher levels of alignment (thus clearer examples of leadership and followership) as part of an institutionalised process (Hellquist Citation2016, p.998).

Alignment is embedded in the enlargement process, which is itself based on strong conditionality: accession states that do not engage with EU policies can expect a negative assessment in their annual reports, especially if it reveals problems relating to specific Treaty-based values. There is, however, little evidence of this occurring, given the generally high levels of alignment. The exception is Turkey, whose accession process has never progressed beyond the early stages and has now stalled. Its lack of alignment strongly suggests both a divergence in foreign policy interests between the EU and Turkey and a lack of contemporary influence enjoyed by the EU.

Beyond the enlargement process, leadership in sanctions does not necessarily imply that others are following the “example” or “model” of the EU as a values-led actor. Rather, the high-level alignment by states with no enlargement aspirations, including Iceland, Norway and (though not part of the alignment process) Switzerland, is demonstrative of a sharing of values and willingness to put such values into practice. Thus, “leadership” here equates to the ability of others to be associated with the EU as an actor rather than seeking to be “led”. In spite of the rising popularity of sanctions (Moret Citation2021), questions of alignment do not follow any clear justifiable process linked mainly to economic interests. Indeed, adoption of sanctions can sometimes run counter to economic interests of states, including members of the EU. For the UK, there is a lack of evidence of divergence from EU sanctions already in place due to the short period under examination since Brexit.

The difficulty in establishing more precisely the extent of leadership is beyond the quantifiable level of alignment by the states mentioned in a sanctions Declaration. For Switzerland and the UK, even if they apply sanctions regimes that mirror those of the EU within a similar timeframe, it is unlikely that either will publicly admit to “following” the EU; rather the nature of close cooperation will be instead highlighted. Whilst cooperation may take place behind closed doors between the EU and others (including non-Member States), the institutional difficulties and necessary secrecy make it difficult to establish with certainty the level of influence of the EU – or indeed the reverse.

Nevertheless, the evidence points to the existence of EU leadership in the sanctions regimes in force – at least at the European level. The example of cooperation with the Arab League, which is not endowed with the ability to coordinate its members and impose sanctions in the same way as the EU, shows the possibility for leadership beyond the immediate regional context. Further research on individual sanctions regimes could reveal the extent to which the EU is able to cooperate with – and even exert influence over – other states around the world that might be willing to impose sanctions. The related challenge would be to ascertain, in cases where the US and EU (or others such as the UK and Canada) adopt similar sanctions, who is the “leader”. We find, therefore, that the evidence points to regional leadership in sanctions, but the extent to which the EU has established itself as a global leader in sanctions is likely to depend on its capacity to leverage influence beyond its geographical sphere. Its leadership abilities may also be dampened in cases where the target shares particularly close economic or political ties with EU allies. The demonstrable success that the EU has experienced in putting together sanctions regimes and providing leadership suggest that sanctions will remain a hallmark of EU foreign policy in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors presented earlier drafts of this article at the following conferences and thank the organisers for their kind support in the review process: “Breaking Bad: Ethical Leadership Conference” (EWIS, Brussels, Belgium 30 June 2021); “Assessing the EU's Actorness in the Eastern Neighbourhood” (EURINT, Iasi, Romania 2–3 July 2021), and NORTIA: Jean Monnet Network Research Day (7–8 December 2020). Special thanks also to Arantza Gomez Arana, Clara Portela, Jan Lepau, Erna Burai, Jamie Gaskarth, Mateja Peter, Ryan Beasley, Biao Zhang, Gustave Meibauer, Juliet Karbo, Adrian Gallagher, Calle Hakensson, Julia Grauvogel and Andi Hoxhaj for taking the time to provide detailed comments on earlier drafts. The authors retain full responsibility for any errors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This is not only in terms of coverage of new targets, but also through imposing them, in general, earlier than other allies. Some exceptions exist, however, such as some of the EU's sanctions against Russian targets, which preceded those of the US (Moret et al. Citation2016) and recent sanctions against Belarus, whereby the US applied measures later than the EU and other allies (European Sanctions Citation2021).

2 The UK has now started to develop its own sanctions regime since leaving the EU in 2020. However, for the purposes of this article, which includes data until the end of 2020 (when the UK was still in the transition period) all mentions of ‘the EU’ include the UK, other otherwise specified.

3 See also Breslin (Citation2017) on the importance of leadership and followership in a post unipolar world.

4 A complete list, including legal acts and guidance documents, is provided at: https://www.sanctionsmap.eu/#/main

5 Decision 2021/142/CFSP of 5 February 2021.

6 Decision 2020/1544/CFSP of 15 October 2020; Decision 2020/796/CFSP of 24 November 2020 and Decision 2020/1999/CFSP of 22 March 2021 respectively.

7 The EU also maintains autonomous sanctions regimes on some of these countries for a variety of objectives, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine. For example, on 6 November 2020, the Council adopted Decision 2020/1657/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in view of Turkey's unauthorised drilling activities in the Eastern Mediterranean. North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Albania, Iceland, and Armenia aligned themselves with the decision, and the extension of the measures until December 2021. We note that Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine submitted EU membership applications in March 2022 – the data used in this article is until 2020.

8 The authors are grateful to Andi Hoxhaj for insights on this point.

9 Kosovo is also listed as a “potential candidate” but its statehood is not recognised by five EU Member States (Slovakia, Romania, Greece, Cyprus and Spain) and not therefore invited to align.

10 Although outside the scope of analysis in this article, it should be noted that Switzerland has imposed sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

11 The Republic of Belarus (Sanctions) (EU Exit) (Amendment) Regulations 2021 SI 2021/922.

12 Including the African Union, the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

References

- Aggestam, L., and Johansson, M., 2017. The leadership paradox in EU foreign policy. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 55 (6), 1203–1220.

- Aggestam, L., and Hedling, E., 2020. Leaderisation in foreign policy: performing the role of EU high representative. European security, 29 (3), 301–319.

- Attia, H., and Grauvogel, J. 2019. Easier in than out: The protracted process of ending sanctions, GIGA Focus, Number 5, https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en/system/files/publications/gf_global_1905_en.pdf.

- Avery, G.C., 2004. Understanding leadership. London: Sage.

- Baun, M.J., and Marek, D., 2010. Czech foreign policy and EU integration: European and domestic sources. Perspectives on European politics and society, 11 (1), 2–21.

- Beaucillon, C. ed. 2021. The research handbook on unilateral and extraterritorial sanctions. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Boogaerts, A., 2018. An effective sanctioning actor? Merging effectiveness and EU actorness criteria to explain evolutions in (in)effective coercion towards Iran. European security, 27 (2), 138–157.

- Breslin, S., 2017. Leadership and followership in post-unipolar world: towards selective global leadership and a new functionalism? Chinese political science review, 2, 494–511.

- Byman, D.L., and Pollack, K.M., 2001. Let US Now praise great Men: bringing the statesman back In. International security, 25 (4)(Spring), 107–146.

- Cardwell, P.J., 2015. The legalisation of European Union foreign policy and the use of sanctions. Cambridge yearbook of European legal studies, 17 (1), 287–310.

- Cardwell, P.J., 2016. Values in the European Union's foreign policy: an analysis and assessment of CFSP declarations. European foreign affairs review, 21 (4), 601–621.

- Cardwell, P.J., 2017. The United Kingdom and the common foreign and security policy of the EU: from Pre-brexit ‘awkward partner’ to post-brexit ‘future partnership’? Croatian yearbook of European law and policy, 13 (1), 1–26.

- Charron, A., and Portela, C., 2016. The relationship between United Nations sanctions and regional sanctions regimes. In: T.J. Biersteker, S.E. Eckert, and M. Tourinho, eds. Targeted sanctions: The impacts and effectiveness of united nations action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 101–118.

- Cooper, A., Higgott, R., and Nossal, K., 1991. Bound to follow? Leadership and followership in the Gulf conflict. Political science quarterly, 106 (3), 391–410.

- Council of the EU. 2007. Conclusion of the 2809th Council Meeting 10657/07, Jun 18.

- Council of the EU. 2016. Shared Vision, Common Action - A Stronger Europe; a Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy. Available from: http://www.eeas.europa.eu/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf.

- Druláková, R., and Zemanová, Š, 2020. Why the implementation of multilateral sanctions does (not) work: lessons learned from the Czech Republic. European security, 29 (4), 524–544.

- Eckes, C. 2020. EU Human Rights Sanctions Regime: Ambitions, Reality and Risks (December 8). Amsterdam Law School Research Paper No. 2020-64.

- Embassy of Switzerland in the United Kingdom, written evidence, Select Committee on the European Union, External Affairs Sub-Committee, ‘Brexit: Sanctions Policy’. 19 September 2017. http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/eu-external-affairssubcommittee/brexit-sanctions-policy/written/70458.pdf.

- Eriksson, M., 2016. Targeting peace: understanding UN and EU targeted sanctions. Abingdon: Routledge.

- European Commission. 2012. ‘Turkey 2012 Progress Report’. SWD(2012) 336 final: http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/key_documents/2012/package/tr_rapport_2012_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2020a. Albania 2020 Report, SWD, 354 final: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/default/files/albania_report_2020.pdf.

- European Commission. 2020b. Montenegro 2020 Report, SWD, 353 final: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/default/files/montenegro_report_2020.pdf.

- European Commission. 2020c. North Macedonia 2020 Report, SWD, 351 final: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/default/files/north_macedonia_report_2020.pdf.

- European Commission. 2020d. Serbia 2020 Report, SWD, 352 final: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/default/files/serbia_report_2020.pdf.

- European Commission. 2020e. Bosnia and Herzegovina 2020 Report, SWD, 350 final: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/default/files/bosnia_and_herzegovina_report_2020.pdf.

- European Sanctions. 2021. Sanctions Profiler: Belarus, https://www.europeansanctions.com/region/belarus/.

- European Union Permanent Delegation to the UN in Geneva. 2014. Letter to the Advisory Committee of the Human Rights Council, Apr 8.

- Fabre, C., 2018. Economic statecraft: human rights, sanctions, and conditionality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Fairhurst, G.T., and Uhl-Bien, M., 2012. Organizational discourse analysis (ODA): examining leadership as a relational process. The leadership quarterly, 23 (6), 1043–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.10.005.

- Foreign Affairs, 2019. A harmful U.S. sanctions strategy? Foreign affairs asks the experts. Foreign Affairs (11 June). https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ask-the-experts/2019-06-11/harmful-us-sanctions-strategy.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) (UK). 2020. UK announces first sanctions under new global human rights regime, (6 July). https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-announces-first-sanctions-under-new-global-human-rights-regime.

- Giumelli, F., 2010. New analytical categories for assessing EU sanctions. The international spectator, 45 (3), 131–144.

- Giumelli, F., Hoffmann, F., and Książczaková, A., 2020. The when, what, where and why of European Union sanctions. European Security, early view, DOI: 10.1080/09662839.2020.1797685.

- Grint, K., 2005. Problems, problems, problems: The social construction of ‘leadership.’. Human relations, 58 (11), 1467–1494.

- Harrell, P., 2018. Is the U.S. using sanctions too aggressively? The steps Washington can take to guard against overuse foreign affairs (11 September). https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2018-09-11/us-using-sanctions-too-aggressively.

- Hellquist, E., 2016. Either with us or against us? Third-country alignment with EU sanctions against Russia/Ukraine. Cambridge review of international affairs, 29 (3), 997–1021.

- Hellquist, E., 2019. Ostracism and the EU’s contradictory approach to sanctions at home and abroad. Contemporary politics, 25 (4), 393–418.

- Helwig, N., 2015. The high representative of the Union: the Quest for leadership in EU foreign policy. In: D. Spence, and J. Bátora, eds. The European external action service. The European Union in international affairs. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 87–104.

- Hillion, C., 2019. Norway and the changing common foreign and security policy of the European Union. Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) report, 1/19.

- Jones, L., and Portela, C., 2020. La evaluación del éxito de las sanciones internacionales. Revista CIDOB d'Afers internacionals, 125, 39–60. DOI: 10.24241/rcai.2020.125.2.39.

- Kalinichenko, P., 2017. Post-crimean twister: Russia, the EU and the law of sanctions. Russian law journal, 5, 9–28.

- Keatinge, T., et al., 2017. Transatlantic (Mis)alignment: Challenges to US-EU Sanctions Design and Implementation, Occasional Paper, RUSI, July, https://static.rusi.org/20170707_transatlantic_misalignment_keatinge.dall_.tabrizi.lain_final.pdf.

- Marošková, T., and Spurná, K., 2021. Why did they comply? External incentive model, role-playing and socialization in the alignment of sanctions against Russia in Albania and Montenegro. Journal of European integration, 43 (8), 1005–1023. DOI: 10.1080/07036337.2021.1906238.

- Marossi, A.Z., and Bassett, M.R. eds. 2015. Economic sanctions under international Law. The Hague: Asser Press.

- Moret, E.S., 2015. Humanitarian impacts of economic sanctions on Iran and Syria. European security, 24 (1), 120–140.

- Moret, E., et al., 2016. The New Deterrent? International Sanctions against Russia over the Ukraine Crisis: Impacts, Costs and Further Action, Graduate Institute. Oct 12.

- Moret, E., Giumelli, F., and Bastiat-Jarosz, D., 2017. Sanctions on russia: Impacts and economic costs on the United States. Programme for the study of international governance, Graduate Institute of International and Development studies, Geneva, 20 March, https://www.graduateinstitute.ch/library/publications-institute/sanctions-russia-impacts-and-economic-costs-united-states.

- Moret, E., and Pothier, F., 2018. Sanctions after Brexit. Survival, 60 (2), 179–200.

- Moret, E., 2021. Unilateral and extraterritorial sanctions in crisis: implications of their rising use and misuse in contemporary world politics. In: C. Beaucillon, ed. The research handbook on unilateral and extraterritorial sanctions. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 19–36.

- Nye, J., 2008. The powers to lead. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Parker, C.F., and Karlsson, C., 2014. Leadership and international cooperation. In: P. ‘t Hart, and R. Rhodes, eds. Oxford handbook of political leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 580–594.

- Parry, M. 2021. Chinese counter-sanctions on EU targets, European Parliamentary Research Service, https://epthinktank.eu/2021/05/19/chinese-counter-sanctions-on-eu-targets/.

- Portela, C., 2010. European Union sanctions and foreign policy: when and why do they work? Abingdon: Routledge.

- Portela, C., 2017. The European neighbourhood policy and the politics of sanctions. In: T Demmelhuber, A Marchetti, and T Schumacher, eds. routledge handbook on the European neighbourhood policy. Abingdon: Routledge, 270–278.

- Portela, C., et al., 2020. Consensus against all odds: explaining the persistence of EU sanctions on russia. Journal of European integration, 43 (6), 683–699.

- Ridi, Niccolò, and Fikfak, Veronika, 2022. Sanctioning to change state behaviour (March 22, 2022). iCourts working paper series, no. 282. Forthcoming in international journal of dispute settlement.

- Sjursen, H., and Rosén, G., 2017. Arguing sanctions. On the EU's response to the Crisis in Ukraine. JCMS: Journal of Common Market studies, 55 (1), 20–36.

- Szép, V., 2020. New intergovernmentalism meets EU sanctions policy. Journal of European integration, 42 (6), 855–871.

- Szép, V., and Van Elsuwege, P., 2020. EU sanctions policy and the alignment of third countries: relevant experiences for the UK? In: J.S. Vara, and R.A. Wessel, eds. The routledge handbook on the international dimension of Brexit. Abingdon: Routledge, 226–240.

- Taylor, B., 2010. Sanctions as grand strategy. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Thorhallsson, B., and Gunnarsson, P., 2017. Iceland’s alignment with the EU–US sanctions on russia: autonomy versus dependence. Global affairs, 3 (3), 307–318.

- UK Government. 2019. Political Declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/new-withdrawal-agreement-and-political-declaration.

- Uhl-Bien, M., et al., 2014. Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The leadership quarterly, 25 (1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007.

- United Nations. 2018. Sanctions unilatérales: un expert de l’ONU dénonce un outil fruste qui pénalise les populations. UN News. Nov 1. Available from: https://news.un.org/fr/story/2018/11/1028152.

- Young, O.R., 1991. Political leadership and regime formation: on the development of institutions in international society. International organization, 45 (3), 281–308.