ABSTRACT

The study of why and when governments are caught out by strategic surprise has been a major occupation of intelligence studies, international relations, public administration and crisis management studies. Still little is known, however, about the structural vulnerabilities to such surprises in international organisations such as the European Union (EU). EU institutions themselves have not undertaken rigorous investigations or public inquiries of recent strategic surprises, instead relying on internal review processes. In order to understand the most common underlying problems causing surprise in the EU context, this paper adapts and tests insights from the strategic surprise literature. It elaborates a theoretical framework with five hypotheses about why the leadership of EU institutions has been prone to being caught by surprises in foreign affairs: limitations in collection capacity, institutional fragmentation of policymaking, organisational culture, member state politicisation, and cognitive biases arising from collective ideas and norms. These hypotheses are tested using a post-mortem approach investigating two significant strategic surprises: the start and spread of the Arab uprisings of 2010/11 and Ukraine–Russia crisis of 2013/14.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) and its member states have experienced a series of significant surprises in their foreign affairs after a period of stability and confidence in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Major cognitive disruptions include the Russo-Georgian Five-Day War (2008), the Arab uprisings (2010–2012), the European migration crisis (2015), the rise of ISIS (2012–2015) and Russia’s annexation and occupation of parts of Ukraine (2013–2014). More recently, the EU’s High Representative (HR/VP) Josep Borrell said that “Brussels” was “quite reluctant to believe” American warnings about Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. We know that such surprises, crises and alleged policy failures often spark public criticisms of intelligence analysts, diplomats, policy planners and decision-maker for their failure to anticipate the crises or to heed warnings (Posner Citation2005, Boin et al. Citation2008). A central concern of the strategic surprise literature in intelligence studies (Betts Citation1982, Jervis Citation2010, Dahl Citation2013) as well as public inquiries (Farson and Phythian Citation2011, Jervis Citation2022) is to establish whether such surprises could have been avoided and what lessons might be learned to reduce the incidence and scale of future surprise. The strategic surprise literature has so far centred overwhelmingly on landmark cases involving the United States and small number of other mostly Anglo-saxon countries. Few works have looked at countries outside this core group and even fewer at international organisations such as NATO (Betts Citation1981) or the EU (Arcos and Palacios Citation2018). This raises doubts about the applicability of key theoretical insights to the EU foreign policy system with its distinct multilevel features, its wide-ranging foreign policy agenda, and lack of explicit legal competences for foreign and military intelligence production. The rich literature on EU foreign policy cannot fill the gap either because it has not systematically engaged yet with the specific challenges of anticipation or the communication and receptivity to foreign intelligence within the EU. It concentrates on the design policies, the speed and coherence of decision-making, organisational fragmentation, individuals’ leadership qualities, or technical challenges of data collection, analysis and sharing. As a result, it is unclear which, if any, of those critiques of EU foreign policy are relevant to the specific challenge of mitigating strategic surprise and which other obstacles need to be tackled to improve “situational awareness and strategic foresight” as expressed in the 2022 Strategic Compass (Council of the European Union Citation2022, p. 33).

Against this background the objective of this paper is to identify the underlying causes of strategic surprise in EU foreign and security policy. In doing so, our work is similar to research on other polities with the aspiration not just to explain outcomes, but to identify factors that are amenable to change so that the potential for future surprise could be reduced (Ben-Zvi Citation1976, Parker and Stern Citation2005). We distinguish five main challenges involved in estimative and warning intelligence for anticipatory foreign policy, highlight the most cited reasons for performance problems and hypothesise how they may apply to the EU. Our primary focus is on the most supranational elements of the EU foreign policy system (Commission, HR/VP, External Action Service), but we also consider the more intergovernmental parts as key consumers of intelligence (Foreign Affairs Council, European Council). We define (foreign) intelligence as privileged and usually sensitive knowledge produced in the service of decision-making on foreign and security matters. Such intelligence draws on and often combines a wide range of sources: some open such as think-tank reports and social media postings, others more secret and specialised such as human informants or intercepted emails. We do not confine ourselves to secret intelligence on state security, and our focus on all-source intelligence means that we include not just those products written by intelligence agencies, but also analysis by country desk officers in Brussels or cables by diplomats based in EU delegations or missions. We will put the framework into action through two crucial but in key respects very different cases of EU strategic surprise: the start and initial spread of the Arab uprisings in December 2010/January 2011 from Tunisia and the Ukraine-Russia crisis of 2013/14. The article concludes by discussing the implications of our findings for scholars studying strategic surprise as they concern multi-national bodies as well as to students interested in the performance and evolution of EU intelligence and foreign policymaking.

The EU’s warning-response problem

Strategic surprises can be defined as largely or completely unexpected events that erode, contradict or question pre-existing assumptions, analytical judgements, and expectations of government elites and generally demand a policy response (Ikani, Guttmann, Meyer Citation2020, p. 201). The study of strategic surprise has been primarily advanced within intelligence studies with attacks by state or, increasingly non-state actors as the main object of study. The drive behind much of the literature is to identify whether and to what extent such surprises might have been avoidable through better performance of organisations, groups and individuals and which, if any lessons, could be learned for better performance in the future. While the primary focus is on the performance of intelligence agencies, substantial attention has also been devoted to the interplay between and within organisations and the relations between so-called producers and consumers of intelligence. This rich body of literature has developed theories mainly through landmark case studies of surprise attacks by state, and more recently, non-state actors (e.g. Wohlstetter Citation1962, Betts Citation1982, Parker and Stern Citation2005, Dahl Citation2013). Most of this literature centres on the United States, other members of the “Five Eyes” alliance for the sharing of intelligence such as Canada, or the rather unique case of Israel (e.g. Bar-Joseph Citation2013). Few attempts have been made to investigate to what extent and under what conditions such theoretical insights “travel” to other states and, particularly, international organisations such as the OSCE and NATO (Betts Citation1981, Edwards Citation1996). This matters particularly since international as well as multi-national intelligence cooperation has increased over the past two decades due to evolving transnational security threats such as jihadist terrorism heightening the need for wider intelligence sharing. The Counter-Terrorism Group, the NATO Special Committee or Europol’s Counter-Terrorism Task Force are a few examples of initiatives that emerged and grew in this period – despite such efforts being often hampered by states’ resistance to pooling of sensitive intelligence products (Aldrich Citation2011, p. 17).

Only a handful of works examine strategic surprises in EU foreign affairs despite a growth in attention to the evolution of EU intelligence structures and cooperation practices (Lledo-Ferrer and Dietrich Citation2020, Van Puyvelde Citation2020). This is problematic as the EU is a profoundly different actor. It does not have a single top decision-maker and consumer of intelligence like the US or the French President, but rather multiple senior decision-makers in the Council and the European Council, the European Commission, as well as the HR/VP as the head of the EEAS and key bridge-builder between EU institutions and member states. Decision-making rules and institutional competences vary across policy and issues areas as laid down in Treaties. In matters of the Common Foreign Security Policy (CFSP) decision-making is based on unanimity among member states and therefore highly vulnerable to variable receptivity to and divergent understandings of emerging threats and opportunities. The key challenge for EU intelligence is not just to provide high-quality tailored analysis for senior EU decision-makers such as the HR/VP, but to prevent decision-making processes from becoming paralysed by advancing a shared understanding among member states.

As there is currently no explicit legal basis in the EU Treaties to create foreign or domestic intelligence agencies with their own budgets, run networks of spies (HUMINT) or intercept phone calls (SIGINT), the EU has gradually created alternative structures and processes for strategic intelligence production with the current legal basis being a reference in the 2010 Council decision on establishing the EEAS. The Single Intelligence Analysis Capacity (SIAC) is a functional arrangement for the production of “all-source intelligence”. It builds on contributions by the EU’s civilian intelligence analysis hub INTCEN and staffed by around 70 EU officials and seconded national analysts. INTCEN can draw on finished civilian intelligence products, mostly at lower levels of classification, provided voluntarily by Member State services and bodies, as well as the analysis of open sources (OSINT) and EU-internal sources. Military intelligence is provided by the Intelligence Directorate in the EU Military Staff (EUMS INT). Relevant EU internal sources include reporting by diplomats and operational commanders in the field, country desk officers or Commission staff working on technical issues such as energy or transport. The EU can also access image intelligence from commercial satellites (through SatCen), intelligence about cybersecurity threats (CERT-EU) and earth observation data (Copernicus).

However, little is known about how the system operates to effectively warn and thus mitigate surprise among the relevant and diverse decision-makers. Arcos and Palacios (Citation2018), the latter the former Head of Analysis at INTCEN, have studied the role and (lack of) measurable impact of a single assessment that accurately anticipated key aspects of the Arab Uprisings three years later. They cite the narrow distribution of the report and the lack of established processes in the EU institutions for what to do with early warnings as factors lowering the receptivity to the report, with its title – Worst case scenarios for the Narrower Middle East – implying low probability (Arcos and Palacios Citation2018). Other former practitioners such as the former director William Shapcott (Citation2011) have written about the challenge of ensuring a uniformed understanding of warnings in a multi-national and multi-lingual setting, whilst another former EU INTCEN director, Gerhard Conrad (Citation2021) highlighted problems in the way intelligence functions within the EEAS are organised and staffed. EU institutions have hardly ever instigated in-depth and genuinely independent post-mortems or inquiries into strategic surprises, but relied on rather limited internal review exercises (e.g. about the withdrawal from Afghanistan), mission reports and technical evaluations of conflict prevention programmes by consultancies and think-tanks. These lack the rigour, resources, and, crucially, the independent perspective of inquiries seen in the US or the UK.

Other relevant contributions to understanding the causes of surprise can be found in the literature focused on EU foreign policy and its handling of foreign affairs crises (Echagüe et al. Citation2011 Hammargård and Olsson Citation2019,), which do not draw on the literature of strategic surprise or on how to avoid common problems of post-mortems (Jervis Citation2010). Whitman and Wolff (Citation2010, p. 96) diagnosed the case of the 2008 Georgia-Russian 5-day war as a “repetition of a well-known EU pattern of no or insufficient action until a crisis has fully escalated, rather than the pursuit of a well-conceived, strategic and properly resourced proactive foreign policy”. Similarly, in the case of the Arab uprisings, the EU has been accused of watching from the side-lines as they erupted and failing to shape outcomes in key countries such as Egypt (Bremberg Citation2016).

However, beyond widespread criticism of the EU as being too reactive, there is less agreement on the main causes and remedies. Many authors attribute the problems in responding to the start and rapid spread of the Arab uprisings and the Ukraine 2014 crises to flaws in policy design and implementation such as the way the EU Neighbourhood Policy was created and conducted (Bremberg Citation2016, Ikanis Citation2021), to the EU’s inadvertent causal contribution to them such as overly cozy relations to autocratic regimes in the southern Mediterranean protests (Hollis Citation2012) or to flawed democracy promotion prior to the Arab uprisings (Teti Citation2012). The EU’s surprise at the events in Ukraine 2013/2014 is often attributed to structurally flawed policies that prioritised trade and commercial objectives and underestimated the geostrategic importance of the region to Russia (MacFarlane and Menon Citation2014, Sakwa Citation2015).

Less frequently one can find investigations of whether the EU is adequately equipped to respond to such crises in the first place, or how features of specific European institutions such as the EEAS served as a baseline for the EU’s (inadequate) response to these crises (Natorski Citation2015, Bremberg Citation2016). In some of these studies, the EU’s senior leadership, including the High Representative Ashton, is criticised during both the run-up and throughout the crises (Howorth Citation2011, Koops and Tercovich Citation2020).

A final angle on the topic comes often from the grey literature on early warning, early response, conflict prevention and crisis management. It has been mostly NGOs and think-tanks who have argued the EU needed to improve the quality of warning as a precondition for early action (Beswick Citation2012). Most of these reports draw predominantly on the writing about the warning response-gap in preventing deadly conflict rather than surprise attacks, and concentrate much of their analysis on “gaps” and fragmentation in information gathering, analysis and decision-making. A prominent line of critique is the forecasting methodology used (Mucha Citation2017) as well as underutilisation of large data (Bengtsson et al. Citation2017).

In sum, the extant understanding of the underlying reasons for why the EU may be surprised in foreign affairs has largely ignored the insights from the strategic surprise literature in intelligence studies and beyond. It is often based on single case studies and has little to say about the distinct underlying but potentially reformable vulnerabilities of the EU in anticipating and mitigating surprises. Much of literature is skewed towards a critique of policies and senior leadership or more technocratic approaches to information gathering, sharing or analysis borrowed from conflict prevention. It is against this background that we propose a post-mortem perspective to test theoretical propositions about the underlying causes of strategic surprise and to identify lessons that – if internalised – should improve the EU’s capacity to better anticipate and react to future threats (Ikani, Guttmann, Meyer Citation2020).

Theorising the avoidable causes of strategic surprises in the EU

The first generation of strategic surprise literature has concentrated on surprises caused by state attacks against other states with some exceptions such as the Iranian revolution, but since 9/11 more authors have examined also plots of terrorist groups (Dahl Citation2013) and “diffuse surprises” such as revolutions and civil wars caused by societal movements (Barnea Citation2020). These latter phenomena have also interested scholars in peace and genocide studies committed to the prevention of violent conflict and mass atrocities (George and Holl Citation1997). Even though intelligence and peace studies communities differ in who is supposed to act against what type of threat and why, these fields do overlap in their interest in warning-response dynamics and share insights about the importance of open-sources to understand societal dynamics (Woocher Citation2011) or the role of bureaucratic and political disincentives in hindering receptivity and response to warnings (Call and Campbell Citation2018). Furthermore, a rich literature in public administration, business studies and crisis management analyses the underlying reasons for why organisations in different domains and sectors miss warnings of impending disasters (Bazerman and Watkins Citation2008).

Despite this common research agenda scholars within and across these fields disagree about the relative weight of factors that explain avoidable surprises in specific cases, sectors and policy domains, most notably about the relative importance of safeguards against the politicisation of analysis, what kind of evidence should be collected and through what means, the optimal relationship between consumers and producers of intelligence, and, more generally, the degree of optimism regarding whether organisations can learn lessons that reduce the frequency or scope of future surprises at all. Our approach follows the so-called reformist school of strategic surprise which acknowledges the existence of obstacles and dilemmas to organisational reform, but is more optimistic about the potential for post-mortems to yield lessons on how to improve warning, receptivity and preventive action (Dahl Citation2013, p. 11–12).

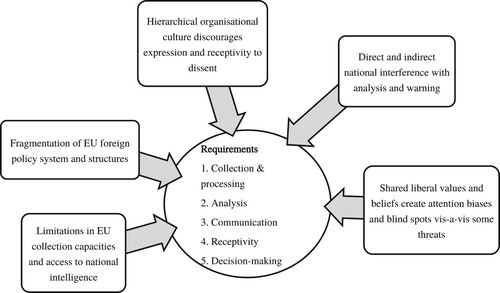

synthesises the generic challenges associated with warning intelligence and preventive action, the most important reasons for why avoidable rather than inevitable surprises happen, and how these might manifest themselves in the specific case of the European Union as a regional organisation with an unusually high degree of actorness in foreign affairs. The process leading from early identification of a threat to a preparatory or preventive action can be broken down into the following distinct yet often interconnected tasks:

setting of intelligence requirements, tasks and priorities appropriate to threats and opportunities;

collection, filtering and processing of relevant and reliable evidence or information from open and secret sources;

state of the art-analysis of such evidence for situational awareness, estimative intelligence or strategic foresight;

timely and persuasive communication of warning intelligence to ensure any knowledge, relevance and action claims are noticed, understood and accepted

sufficient receptivity to and prudent prioritisation of knowledge claims by organisations and practitioners given competing resource demands

timely and prudent decision-making about whether, when and how to act in relation to a potential threat, risk or opportunity

Failures in the performance of one task will affect the performance of others; for instance, any fair criticism of a lack of receptivity, prioritisation or timely response depends on an appreciation of how credible, confident and precise estimative intelligence has been. Conversely, criticism of the lack of timely, clear and confident warnings needs to be grounded in an appreciation of how senior consumers previously reacted negatively or positively to warnings, and the nature of any bureaucratic or political disincentives. A parsimonious theory of avoidable causes of surprise ought to capture those reasons that affect the performance across various tasks to maximise explanatory power and identify root-causes of performance problems. It should avoid over-determining causes that lead to a laundry-list approach. The factors elaborated below are synthesised from the different bodies of literature discussed in the previous section as well as the authors’ previous empirical research (Meyer, De Franco, Otto Citation2020).

Limitations in the EU’s own collection capacities coupled with limited or inconsistent access to member states intelligence.

Collection capabilities are crucial to intelligence services, as the capacity to obtain high-quality information determines whether they are able to provide accurate and actionable warning (Betts Citation1978). Much of the literature on EU intelligence starts from the limiting consequences of the “national security exclusion” in Article 4(2) TEU for the ability of the EU to collect its own intelligence from secret sources such as human informants and intercepted communications (Fägersten Citation2014, Seyfried Citation2017). The lack of explicit provisions in the EU Treaties creates legal limitations on collection, let alone covert actions, mirroring the legal constraints on EU operational spending in the domain of military and defence. As a result, the EU institutions, and particularly its civil and military intelligence hubs EU INTCEN and EUMS-INT have been heavily dependent on “finished” rather than raw intelligence provided voluntarily, but, as it is argued, often belatedly and inconsistently by member states reluctant to contribute to a machine, which cannot give them much back or might expose their methods (Daun Citation2005).

The EU’s foreign policy system is too fragmented to “connect the dots” necessary for accurate and timely foresight.

One of the avoidable reasons which leads to organisations failing to anticipate an emerging threat is an inability to share and jointly analyse threat indications or signals within as well as across departments. A failure to “connect the dots” among agencies and ministries has been identified in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Citation9/Citation11 Commission Citation2004). Organisational silos that hinder information sharing have also hindered banks in correctly identifying the level of risks on their balance sheets prior to the 2008 financial crisis (Tett Citation2011). Previously, scholars identified such issues of “siloisation” in EU foreign policymaking specifically (Becker et al. Citation2016, Bürgin Citation2018). It is to be expected that the EU foreign policy system is particularly affected by the duality between the supranational, the intergovernmental and the hybrid parts of the system. The largest body at the centre of the EU, the European Commission, is subdivided into Directorates-General (DGs) with considerable relevance for the conduct and implementation of the EU’s “external action”, such as Trade, Development and Enlargement/Neighbourhood (DG NEAR). Each DG has its own policy-lens and way of doing things. Each is led by Commissioners and General-Directors with their own views, agendas and personalities. The European External Action Service (EEAS) is not a foreign ministry but rather a hybrid diplomatic service supporting specifically the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP, including CSDP) where decision-making in the Council of Ministers, the intergovernmental part of the system, relies on consensus-building among member state representatives. Despite the best efforts of the triple-hatted HR/VP the expectation is that the system will struggle with emerging threats that cut across the three pillars and policy portfolios of the system.

| 3. | Prevailing hierarchical organisational cultures discourage the expression of and receptivity to inconvenient intelligence claims. | ||||

The literature on warning and surprise, starting with Grabo (Citation2010), has repeatedly emphasised that warners will at least initially be in a minority and exposed to a degree of psychological stress from the dominant views held by the larger group or the leadership of the organisation. The strategic surprise literature has long argued that intelligence community cultures may stifle the articulation of and receptivity to warnings (Hart and Simon Citation2006, Maras Citation2017). Similar points have been made in work on disasters and emergencies in other domains (Weick and Sutcliffe Citation2007). Organisational cultures refer to “the set of assumptions, values, and beliefs that members of an organization share, abide by, and utilise in their day-to-day work activities” and impact how decisions are made, the way individuals act in the organisation and what kind of behaviour is rewarded (Maras Citation2017, p. 189). Organisational cultures that are highly hierarchical emphasise conformity to an identity articulated at the top, and encourage blame-shifting, rather than openness to mistakes and valuing of staff professionalism (Gerstein and Schein Citation2011). The institution at the core of most EU affairs, the European Commission, has been shaped by the French administrative model with its emphasis on strong hierarchical steering and line-management from the top, with powerful Directors of DG’s and Commissioners served by hand-picked political cabinets. It has a strong esprit de corps. The new and much smaller EEAS is a service that has taken over elements of the Commission’s culture, including the drive to build a similarly strong collective spirit (Juncos and Pomorska Citation2014). Even though personalities and leadership styles may vary between Commissioners and the most senior officials in Commission and EEAS, the importance of hierarchical structure and the efforts to sustain or build a strong sense of identity creates organisational cultures in both organisations that militates against the communication of and receptivity to warnings.

| 4. | Member states’ inclination to interfere with, politicise and undermine warning-response processes. | ||||

The politicisation of intelligence and its negative impact on analytical objectivity has been well-documented as a key problem for warning-response dynamics in the US-focused intelligence literature (Rovner Citation2011, Marrin Citation2013). It is inevitable that a body like the EU will depend on the direct and indirect support of member states to conduct its foreign policy. The EU, like any other international organisation depends on member state support for its funding, competences and overall legitimacy. Member states differ in the salience and content of their geographic and policy interests, their role conceptions, worldviews and strategic cultures (Biehl et al. Citation2013), as well as their size, powers and operational capacities. This diversity can be hypothesised to create asymmetric receptivity within the more intergovernmental part of the system to the knowledge, relevance and particularly action claims of any warnings. This is particularly true for highly salient and controversial issues such as Russia or relations with the MENA region, less so on others such as jihadist counter-terrorism (Arcos and Palacios Citation2020). The key question is whether these asymmetries and divergences translate into structural problems, if member states are allowed to interfere directly or indirectly in the process of collecting, analysing and communicating intelligence assessments in the supranational and hybrid parts of the system. The EU could be particularly prone to such a politicisation of analysis, as the separation between intelligence production and policymaking is weak (Conrad Citation2021), inadvertently creating conflicts of interest at the heart of the intelligence-policy interface.

| 5. | Prevailing cosmopolitan and liberal values create attention biases and blind spots against seeing threats from actors who do not share these values. | ||||

Studies on the political psychology of intelligence (Heuer Citation1999) and strategic surprise (Bar–Joseph and Kruglanski Citation2003) have highlighted the role that cognitive and motivational biases play in the misperception of threats. Intelligence producers and consumers are prone to being unconsciously influenced by their pre-existing worldviews, operational codes or belief systems when paying attention to certain threats or interpreting evidence to reach analytical judgements about the future. Bodies that place a premium on cultivating a strong esprit de corps such as the European Commission may inadvertently create biases through how their employees are recruited and socialised. It may have a workforce that is very similar in education levels, socio-economic background, beliefs in meritocracy and a shared commitment to the European project, its values and the informal norms that enable mutual beneficial cooperation across national boundaries. This might lead to mirror-imaging by impeding the ability to interpret the worldviews, motivations and reasoning of foreign actors who do not share these commitments and values.

Research design

The key purpose of post-incident investigations after negative surprises, whether adverse outcomes for patients, plane crashes, industrial disasters or surprise attacks, is to identify suitable lessons for governments, organisations or practitioners to learn that, if internalised, are likely to reduce the incidence and scale of future surprises through improved performance (Ikani, Guttmann, Meyer Citation2020). As surprises and errors are to some extent inevitable, postmortems need to take great care to correctly ascertain the immediate and proximate causes of the surprising events, whether they were or should have been anticipated by officials or experts, whether preventative or mitigating action was feasible without creating disproportionate risks and costs, and whether one can identify root-causes of performance problems applicable beyond the single case. As postmortems investigations typically enjoy greater independence, freedom and legitimacy compared to internal reviews they are better able to advance more ambitious and long-term recommendations that can potentially address these deeper-root causes.

In the case of the EU we distinguish between problems that can reasonably be addressed with one electoral cycle of European Parliament and Commission, and those that either require a more sustained engagement over more cycles, or most difficult, constitutional changes to the EU’s Treaties such as a shift to qualified majority voting in foreign policy matters or merging the EEAS with the EU Commission. Some types of root-causes are notoriously difficult to address because they are linked to resource prioritisation problems, are deeply hardwired into how institutions work, legal competences or politically controversial as they create displacement risks, policy trade-offs or ethical dilemmas. The risk of doing more harm than good could also arise from a flawed attribution of poor outcomes to second or third order causes (Boin et al. Citation2008) or an over-generalisation from a highly unusual case (Walshe Citation2019).

For this study we selected two cases in which actors were similarly surprised in terms of the recognised gap between the event and previous beliefs; the range of surprising substantive threat characteristics as well as the spread of the surprise among relevant officials (Guttmann, Ikani, Meyer, Michaels Citation2022, p. 13–17). For our first case study we focus on the start of the Arab uprisings in Tunisia, as well as its early spread to Egypt in January 2011 as a key surprising aspect. In December of 2010, the self-immolation of Mohamad Bouazizi in protest against the dire socio-economic conditions of the country triggered protests and eventually a revolutionary moment in Tunisia. The protest against the authoritarian regime of Ben Ali gathered force and, surprisingly, spread to Egypt in January of 2011, where similar protests emerged against the Egyptian ruler Mubarak. Soon after, the movement spread across the MENA region, amongst others to Libya, Yemen, Sudan, Bahrein and Syria. The Ukraine crisis of 2013/14 started when in November 2013, Ukrainian president Yanukovych decided to forego signing an Association Agreement with the EU under great Russian pressure, after which protests on the “Euromaidan” escalated and led to conflict. The most surprising aspect was the Russian covert operation that led to the annexation of the Crimea in 2014 in blatant violation of international law.

Both case studies were followed by substantial internal and external criticism on the EU for failing to anticipate or prepare for such events. In the case of the Arab uprisings, the EU was criticised for not living up to its values in supporting the democratic and social aspirations of the people in the MENA regions and instead initially even siding with the authoritarian regimes in the region (Juppé Citation2011, Börzel Citation2015). Conversely, after the Ukraine crises, critics lambasted the EU for being too naïve, paying insufficient attention to power politics and realism (Sakwa Citation2014, Krastev and Leonard Citation2015).

Yet, the cases are also very different in how they unfolded. The Arab uprisings were a case of a slower-burning, bottom-up, or “diffuse” surprises where conventional techniques of intelligence services to unearth “secrets” were of limited or no help, but where country expertise, up-to-date open data and good analysis were required for accurate anticipation. In contrast, even if the Russia–Ukraine crisis of 2013–2014 displayed some elements of diffuse surprise with the Euromaidan protests, it is better described as a “concentrated surprise” resulting from Russia successfully deceiving the EU and other Western actors’ about its true intentions and actions on the ground as it deployed special forces to engineer a coup and then staged a referendum to legitimise its formal annexation of Crimea. These case differences allow us to test our hypotheses more rigorously regarding the underlying causes of EU strategic surprise and identify prime candidates for broader lessons to be learnt.

Our empirical approach started from desk research of the most authoritative expert sources such as Brussels-based think-tanks, NGOs and quality news media during the time period, to draw up highly nuanced timelines of knowledge claims made by the most authoritative public sources and how they were received, accepted or rejected by political institutions and decision-makers. The in-depth and nuanced understanding of how knowledge claims emerged over time, contradicted, or reinforced each other in public was complemented by 55 semi-structured interviews with officials working on these cases at the time in Brussels and in the field to deepen our understanding of what happened behind the scenes. These interviewees worked at the European Commission DG NEAR (4), the European Council (1), the EEAS (22), INTCEN (3), the European Union Military Staff Intelligence Directorate (2), at EU delegations of Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, Algeria, Ukraine and Russia (19), and finally in EU member states relevant to these cases (4). We tested some of our arguments with current and former officials working at the EEAS and INTCEN as well as the British and German intelligence services during three practitioner workshops held in Brussels in 2019, in London in 2020, as well as in an online workshop in 2021. We sought to mitigate distortions in memory and reasoning arising from hindsight bias by seeking out systematically divergent interview sources in terms of their (national) policy preferences and worldviews as well as their positions in the hierarchy and geographical location at the time. We were conscious of variable and evolving levels of uncertainty about different aspects of these phenomena and tried to systemically look for alternative accounts and what was likely to happen next. We were also conscious of the need to systemically consider the constraints and contexts within which EU actors operated and which could be expected to help or hinder performance. For instance, the degree of discontinuity from previous patterns, the nature of deception and secrecy by adversaries, or to benchmark the EU against the performance of other much better-resourced actors such as the United States. Secondly, we consider situational factors affecting particularly receptivity and decision-making such as the stability of institutions or agenda competition from other crises. This empirical strategy enabled us to assess for each of the hypotheses whether they played a role in the case study in question, and if so, to what extent this contributed to causing strategic surprise for the European Union.

Testing underlying causes of EU strategic surprise

Constrained collection capacity and limited access to raw and assessed intelligence

Contrary to the emphasis placed in the literature on the EU limitations regarding intelligence collection, we found little evidence that these were a major problem for the accuracy or impact of early warning in the two cases. This is not entirely surprising as both cases represented major discontinuities from previous patterns and were therefore analytically and cognitively very difficult. Other actors with more sophisticated and extensive collection capacities such as the US or the UK were no more foresighted than the EU in these cases. In fact and as mentioned above, the EU’s INTCEN was able to produce a remarkably accurate paper anticipating the possibility of a transnational wave of uprisings in the Middle East (Arcos and Palacios Citation2018). We have also heard interview evidence of well-informed late warnings from EU delegations on the ground. For instance, in late 2010 officers in Tunis were sending increasingly worried messages that the Ben Ali regime would not last, after having expressed some concern in prior years (Interviews 29, 30, 46). Similarly, in the case of Crimea, INTCEN had produced a prescient analysis in late 2013 which assessed it likely that Yanukovych could make a U-Turn on signing the Association Agreement and that in this scenario substantial protests and instability would follow (Higgins Citation2014). It was able to produce these reports based on solid expert judgements, member services classified intelligence contributions and open sources. So, in these cases, the EU was not held back by information compared to better-resourced actors, but by difficulties in generating and testing worst-case hypotheses.

This is not to exclude that the EU’s limitations in collection capacity may not be serious liabilities in analytically less difficult cases. For instance, the US has learned from the 2014 Crimea surprise to substantially improve its collection capacities in relation to Russian military plans and hybrid warfare. These capacities enabled it to accurately warn in public and private four months prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and to provide tactical warning intelligence to Ukraine authorities that helped them thwart the Russian attack on Kyiv. More broadly, our interviews at INTCEN largely confirmed the problem of an unstable flow of intelligence and an insufficient quality of evidence provided by member states. Being dependent on what member states choose to provide means EU officials lack what they called “slow intelligence” and are therefore less able to pick up weak signals that indicate changes in long-term trends and thus benefit strategic warning.

Fragmented structures for foreign and warning intelligence

Our cases largely confirmed the thesis that the EU suffers from fragmented organisational structures in sharing and jointly analysing relevant intelligence from a range of sources. Instead, there is a cacophony of knowledge claims. As mentioned, the EU consists of a wide range of institutional actors which together contribute to the foreign and security policy machinery, operating at different levels and with differently formed institutional logics. While some institutions, such as the EEAS, are staffed in part by member state diplomats and thus form an informal link between domestic institutions and the supranational level, others are characterised by a “Community-minded” supranational logic of action (Henökl Citation2015, p. 689, 694). Some parts of the European Commission, such as DG NEAR, focus on a very specific area of EU foreign policy, but are for various reasons not part of the EEAS. The result is an overlap in competences and geographic focus areas. In the EU system, intelligence originates from many different quarters, comes in different formats, perspectives and conclusions without a single authoritative body available to aggregate, compare and analyse and communicate it to the senior leadership. This does result in information overload and can be confusing to senior officials. It also creates the temptation to cherry-pick the information that best fits their policy preferences and ignore less convenient claims. For the Ukraine case, for example, DG TRADE had been working on the trade-related and legal aspects of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. While some officials within DG NEAR and particularly the EEAS did start to worry in 2013 about a hostile reaction of Russia to the Association Agreement being signed, Russian economic coercion and propaganda against EaP states in summer/autumn 2013 did not trigger a joined-up EU reassessment of Russia’s strategy in Ukraine.

Moreover, institutional fragmentation complicates communication among analysts and diplomats themselves, who face technical and administrative-cultural barriers to information sharing. INTCEN reports are generally classified – even when they consist of open-source information – due to the sensitivity of subject matters and political assessments. This meant in practice that they could not be read at the EU Delegations in the MENA countries in the timeframe under scrutiny, as they had neither secure technical means of communication nor secure reading rooms. As one interviewee commented, it was “as if [INTCEN and the EEAS] were two services doing analysis and then they were not working as well together as could be the case” (Interview 30). Interviewed INTCEN officers criticise that their confidential reports end up in the “basement” of the Berlaymont building, because Commission officials need to read their reports in a confidential reading room. The higher the classification of the report, the slower the delivery. “If we want to reach a high level, there are so, so many people and lines in between”, argued the interviewees, who compared their situation to that of the UK, where they thought officials could “send something to their prime minister” in seconds (Interviews 36, 37, 38). Something they say is impossible if you want to reach the HR/VP. The shortcomings of the EU’s infrastructure for the secure sharing of confidential information are widely recognised, yet more secure IT systems will not solve the deeper problem that interpretations and frames of reference differ across institutions, even if they are on the same subject matter. This is particularly the case in communication between policy communities and intelligence communities (Hart and Simon Citation2006, p. 47). We have seen the same underlying issues at play elsewhere, for instance, hampering the EU’s wider efforts in conflict and crisis management policies in Afghanistan and Mali (Bøås Citation2020).

Inhibiting organisational culture within the EEAS

A largely overlooked problem in the literature on EU intelligence and foreign policy are the problematic norms and incentives inherent in the administrative cultures of EU institutions and here in particular the Commission and the EEAS. Our research revealed that particularly lower-ranked officials felt that their reports and warnings on different aspects of these cases were either ignored, or often received a negative reaction from their superiors. This was the case for both officials in Brussels and for officials sending warnings back from EU delegations, and could be observed in both cases. Multiple EU Delegation officials working in the Tunis, Cairo and Algiers delegations complained about the very limited receptivity in “Brussels” to their warnings. Another interviewee called December 2010 warnings from the Delegation in Tunis on the combustibility of the Ben Ali regime “routine reporting of the Delegation”. They argued they frequently reported “it can’t go on like this, there would be a problem. But [in Brussels] they were not listening” (Interview 31). INTCEN officials complained that there is an “exaggerated professional optimism” at play within the higher echelons of the EEAS and the Commission, where people do not want to hear about “bad news, what might derail”. Tunisia had been considered a comparatively stable country in the region, and the general expectation was that any disruption would not start there. Some officials believed or experienced that loud and clear warnings could be or were disadvantageous to their careers. “If you want to succeed in regional directorates at EEAS, you better do not antagonise your superiors, that is not in the best interest of the system” (EEAS official, Brussels workshop, November 2019). EEAS officials seconded by member states were particularly alive to such concerns as their careers and their continued posting to Brussels is highly dependent on approval by superiors in the capitals.

We also came across reports about inappropriate requests made to officials to change their reporting to make it less troublesome and inconvenient to the hierarchy. One interviewee for example reports strong pressure to alter their report warning that the Ben Ali situation in Tunisia indeed constituted a “time bomb”. As a result, they had to “sandwich” negative forecasts and warnings into positive messages (Interview 31). We heard at practitioner workshops participants saying there was less and less space for dissent within the EEAS with reporting having to fit increasingly with “what the higher level wants to read”.

In the case study on the Ukraine crisis, a delegation official at the time said he had been asked by a superior in Brussels, unsuccessfully, to withdraw a particularly outspoken report so that they could claim to have never received or read it (Interview 27). While we could not verify any of these specific interview claims through further interviews or access to documents, the frequency of such testimony suggests that organisational culture is at work here.

The EEAS has been described as an “interstitial organization”, recombining of “physical, informational, financial, legal and legitimacy resources” from different organisations belonging to various organisational fields and combing personnel coming from the European Commission, particularly DG Relex, the Council of the EU and the Member States (Bátora Citation2013, p. 599). Juncos and Pomorska (Citation2021) describe how the dominant procedural norms within the EEAS products itself appear to be geared towards consensus-building. This is particularly the case when it comes to the production of estimates regarding how countries or regions may develop. INTCEN products are also subject to such mechanisms if they are in fact noticed and if no consensus emerges are prone to being silently discarded without top-level intervention on its behalf. The consensus-orientation and strongly collaborative processes may work well for policy coordination or planning of structural prevention, but are likely to stifle and weed-out the atypical and minority views needed for early warning. This is particularly the case as neither the EEAS nor relevant DGs were systematically trying to promote such minority views through red-teaming or analytical dissent channels. The mixing of responsibilities for assessment and warning with the responsibility for policy also creates vulnerabilities for member state induced politicisation discussed next.

Member state politicisation of analysis and receptivity

Politicisation of the EU’s warning response dynamics by member states can take different forms. Indirectly, all warning producers need to consider issues like salience and divergence when they communicate warnings in a way that resonates with diverse audiences and brings about sufficient convergence in threat perceptions given the unanimity requirements in decision-making (Brante Citation2009). The diversity of member states historical experience and country links could be an asset for surprise-sensitive forecasting, as it provides the EU with deep country expertise, local connections and alternative hypotheses “for free”. However, we found that such a diversity in expertise frequently turns into liability when analysis is being politicised as officials experience, fear or expect hostility and pushback from member states, or when senior officials resist highlighting threats and risks relating to specific countries. This was for example the case when an EU Delegation warning on the explosive situation in Tunisia was hotly contested in the PSC in January 2011 (Ikani, Nikki Citation2021). As one official commented about the Arab uprisings: “If you give a negative assessment of Tunisia or Algeria, you will end up in the PSC, the day after you will end up with antagonised member states that have to face the wrath of their clientele in the countries concerned” (EEAS official, workshop Brussels, November 2019). Several interviewees confirmed that similarly, the production of EU country watchlists for early warning purposes was affected by intra-EU bargaining over who should be included (Interview 33, 36, 37, 38). This has occasionally led to countries being deleted from draft watchlists after interventions by member states. Furthermore, building a consensus among member states to act on certain countries prior to a crisis is known to be difficult. This negatively impacts the motivation of potential warners, who might feel the EU is unlikely to act in any case. For instance, before the Russian invasion of Crimea interviewees thought that any attempt of even soft sanctions to deter Russia would be doomed to fail. Even afterwards, the EU struggled for weeks and months to agree on sectoral sanctions. Sometimes, the expected pushback by member states results in self-censoring, as officials are unwilling to invest time into reporting that would touch upon open nerves, and not get a follow-up anyway. An INTCEN official indeed claimed: “We pick our battles now” (Interview 36).

A consequence of the mixing of intelligence with member state advocacy is that warnings are constantly scrutinised as to whether they come with “national flags” and if so, they tend to be discounted by the receiver. Kuus (Citation2013, p.178) coined the “pens down-syndrome” whereby officials switch-off when they hear other officials of some nationalities publicly speak about specific countries or threats as they believe they know what comes next. This also applies to uses of historical paradigms in arguments. In the case of Crimea, for example, Germans were using the analogy of 1914 to warn of sleep-walking into an escalation, whereas Poles saw the parallels to the 1930s with an authoritarian leader who is using the pretext of protecting his national minority to make territorial claims on neighbours (Interview 26). Kuus observed that officials from some Eastern European countries were seen as Russophobe or paranoid about Russia, rather than being particularly knowledgeable about their Eastern neighbours because of historical experience, necessity, or language. This played out already in 2008 when the warnings on Georgia by the Swedish EU Special Representative Peter Semneby were at least partially discounted because of his nationality and association with the Swedish Foreign Minister and known “Russia hawk” Carl Bildt (Meyer, De Franco, Otto Citation2020, p. 234). We found such attributed source biases also among EU member states ministers in relation to warnings and advocacy from Swedish and Polish Foreign Ministers in the Ukraine crisis case study.

Blind spots created by dominant worldviews and policy templates

The accusation that the EU is blind to geopolitical and security risks because of its overly optimistic liberal worldview is not new (Kagan Citation2003), but has been forcefully articulated again in the aftermath of the Russian annexation of Crimea (Mearsheimer Citation2014). The reality is more nuanced: EU foreign policy is not simply run by the Commission or the High Representative, but also shaped by member states, some of which think in geopolitical terms and are sensitive to different kinds of security threats. There does, however, appear to be a compartmentalisation of this thinking when member states are in Brussels and are reluctant to reason geopolitically. Former Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski told us in an interview he was convinced that “colleagues who as national leaders think geopolitically”, “refuse to believe that the EU is in competition with Russia for example” when in an EU-context. “[They] think of the EU as a legal union as a trade organisation, not as a geopolitical subject” (Interview 26).Footnote1

While this may not apply universally across issue or country cases, in the case of Ukraine we did observe a bystander effect by those countries like France, Germany and other parts of the EU system. They had the capacity to analyse geopolitical risks and threats, but did not attempt to bring their analysis to the attention of the EU’s institutions and instead largely deferred to the European Commission. The Commission was the lead institution for the European Neighbourhood Policy, backed by a small group of Northern and Eastern member states with strong interests in getting the Association Agreement with Ukraine signed in 2013. The EEAS in its formative stage of development and under a cautious and inexperienced leadership lacked internal conviction and influence to correct this oversight. As result, both the processes of knowledge production in Brussels and reporting by EU Delegations in Kyiv and Moscow were wholly geared towards the narrow and technical requirements of the Association process. It was underpinned by a historically formed worldview centred on shared benefits of trade-liberalisation and the adherence to fundamental international law, including the 1994 Budapest memorandum guaranteeing Ukrainian independence and sovereignty. Shared beliefs were that the Association process and DCFTA were just about economics and might even be beneficial to Russia, and in the worst case, any Russian reaction would be limited and manageable. One interviewee complained “the EU leadership totally ignores the strategic and geopolitical element […]. signing a memorandum of agreement, signing an Association Agreement [..] It is what we do” (Interview 41). Another EEAS official recalled:

we failed in not having a fairer assessment of what all this meant to Russia. We didn’t want to admit it, and I remember at the time as well many were saying and very high placed people were saying, “Oh, but we have no geostrategic agenda on this when we’re pursuing the Association Agreement” […] I was baffled hearing these kinds of comments.

The problem for early warning and early action is not just that the dominant worldviews make it more difficult to accommodate alternative perspectives, but that these views are integral to the policy templates themselves, which in turn have significant consequences on the ground. In other words, the warnings would undermine the EU’s own approach and policy direction: to warn about public protests that might topple regimes in the MENA region would be politically inconvenient not just because of the potential consequences to some EU member states, but also because it implies that the EU’s policies might not only have failed on their stated objectives, but may have contributed to deepening inequalities in these countries. Similarly and without condoning it, the EU-association process of Ukraine has inadvertently increased the probability of a more aggressive reaction by Russia. States’ intelligence services suffer from similar blind spots as they struggle to correctly anticipate and warn about threats at least partially caused by the government’s own decisions, efforts and policies, for instance, the over-optimistic assessments of the US-trained Iraqi army against so-called Islamic State in 2014 or the Afghan army against the Taliban 2021.

Conclusion

This paper made the case for drawing on, adapting and testing insights from the strategic surprise literature in the study of EU conflict prevention, early action and surprise in foreign affairs. Starting from a synthesis of key insights from this literature we developed a theoretical framework for understanding the most common underlying causes that make surprise and its negative implications for policy more likely in an EU context. The framework goes beyond the literature’s emphasis on better relaying and sharing intelligence, better forecasting methods, the rejigging of institutional remits, or the critique of policy and leadership. We used a post-mortem approach in two cases to test five reasons that may make the EU particularly vulnerable to such surprises. The findings were elaborated above and are summarised in .

Table 1. Results from hypotheses testing in two cases.

The findings do confirm the relevance of some critiques of EU foreign policy, particularly concerning fragmentation between functionally interdependent yet legally separate foreign policy areas and institutions. They also confirm the role that wide-spread perceptions of mutual benefits and a lack of geopolitical thinking played in the case of Crimea, but our analysis highlighted how such blind spots were exacerbated by a bystander effect empowering supranational actors and being hardwired into dominant policy-templates. Our findings also point to largely overlooked factors in the study EU foreign policy, particularly the stifling role played by a hierarchical organisational culture and by member states’ politicisation of the analytical process. While the multi-national EU is somewhat less vulnerable to the politicisation of intelligence compared to states given its inherent diversity, attempts to sustain or build a strong esprit de corps in supranational bodies can reduce the analytical benefits of cognitive diversity for warning intelligence. A second problem is often blurred responsibilities between intelligence production and policymaking. Furthermore, too often member states’ diverse historical experiences were not used as an asset for better analysis, but dismissed as prejudice or interest masquerading as knowledge. Contrary to expectations, we did not find much evidence in these two cases that constrained collection capacities and national intelligence sharing were a major problem for the EU despite the extensive attention devoted to these factors in the small EU intelligence literature.

Academic studies based on a postmortem approach fill an important gap as long as the EU itself eschews initiating independent, rigorous and in-depth reviews of critical cases of surprise. Post-incident inquiries that are genuinely independent, but officially supported by EU institutions would benefit from greater access to documents and witnesses, more visibility and resources compared to academic endeavours. Future post-mortems on new cases in foreign affairs and potentially other areas of EU public policy are needed to test whether the underlying problems identified here apply in other cases or indeed to other types of risks and hazards. Our framework could also be useful in the nascent field investigating strategic surprise in international organisations such as NATO, UN, or African Union.

We lack the space to elaborate in more detail on how the identified root-causes could be addressed. Some lesson-learning has happened already, for instance, with the creation of the fusion cell within INTCEN to address hybrid threats. Further actions to consider might include improved training on handling assumptions and biases, targeted recruitment of specialist staff and conscious use of nationality for analytical challenge, cultural and procedural change to encourage the constructive expression of analytical dissent coupled with improved career protection and a code of conduct for managers, better separating knowledge from policy functions, breaking down institutional barriers to “all-source intelligence”, and finally, improving the legal basis for an EU intelligence function in the Treaties.

Ethics statement

The interviews were conducted as part of 3 separate research projects, although mainly from the third (LRS-18/19).

Each project was separately cleared by the King’s College Research Ethics Committee. The reference numbers for these permissions are:

• REP/14/15-89

• REP(WSG)/09/10-13

• LRS-18/19-10370

This implied the interviewees received an author information sheet as well as a consent form to sign. However, given the sensitive nature of the interviews, interviewees were also given the option of consenting without signing the form, an opportunity which most interviewees made use of.

Radek Sikorski, interviewee 26, has read the passages we are citing and has e-mailed his permission to the author(s).

Ethics_statement.docx

Download MS Word (13.1 KB)Appendix_-_interviews.docx

Download MS Word (17.2 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the interviewees and workshop participants, the Advisory Board members of the INTEL project, Dr Tom Casier as well as participants of a joint KCL-LSE seminar for comment on an early version of a paper, and the editors and referees of European Security. The authors alone are responsible for the content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nikki Ikani

Nikki Ikani is an Assistant Professor in Intelligence and Security at the Leiden Institute of Security and Global Affairs. She is also a Visiting Research Fellow at the War Studies Department at King’s College London. Her research at the intersection of intelligence studies, public policy studies and EU foreign policy has been published in Geopolitics, the Journal of European Integration, Intelligence and National Security and in the edited volume Crisis and Politicisation: the Framing and Re-framing of Europe’s Permanent Crisis (Routledge, 2021).

She is the author of Crisis and Change in European Union Foreign Policy (Manchester University Press, 2021) and editor of Estimative Intelligence in European Foreign Policymaking: Learning Lessons from an Era of Surprise (Edinburgh University Press, 2022).

Christoph O. Meyer

Christoph Meyer is a Professor of European and International Politics at King’s College London and Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. He has worked extensively on European foreign and security policy and is the author of The Question for European Strategic Culture (Palgrave, 2006), the co-editor of Forecasting, Warning and Responding to Transnational Risks (Palgrave, 2011), and the lead author of Warning about War: Conflict, Persuasion and Foreign Policy (Cambridge University Press, 2020) – winner of the ISA and ISA-ICOMM Best Book Awards for 2021.

He was PI of FORESIGHT project funded by the European Research Council and Co-PI with Michael Goodman on the ESRC-funded project on intelligence and learning in European foreign policy (INTEL) which informs this article, and is lead editor of Estimative Intelligence in European Foreign Policymaking: Learning Lessons from an Era of Surprise (Edinburgh University Press, 2022).

Notes

1 Author(s) received e-mail permission to cite Sikorski by name.

References

- 9/11 Commission. 2004. The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. Washington, DC: USA Government Printing Office. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-911REPORT/pdf/GPO-911REPORT.pd

- Aldrich, R.J., 2011. International intelligence cooperation in practice. In: H Born, I Leigh, and A Wills, eds. International intelligence cooperation and accountability. London: Routledge, 18–42.

- Arcos, R., and Palacios, J.-M., 2018. The impact of intelligence on decision-making: the EU and the Arab Spring. Intelligence and national security, 33, 737–754.

- Arcos, R., and Palacios, J.-M., 2020. EU INTCEN: a transnational European culture of intelligence analysis? Intelligence and national security, 35 (1), 72–94.

- Bar-Joseph, U., 2013. Forecasting a Hurricane: Israeli and American estimations of the Khomeini Revolution. Journal of strategic studies, 36 (5), 718–742.

- Bar–Joseph, U., and Kruglanski, A.W., 2003. Intelligence failure and need for cognitive closure: On the psychology of the Yom Kippur surprise. Political psychology, 24 (1), 75–99.

- Barnea, A., 2020. Strategic intelligence: a concentrated and diffused intelligence model. Intelligence and national security, 35 (5), 701–716.

- Bátora, J., 2013. The ‘Mitrailleuse Effect’: The EEAS as an interstitial organization and the dynamics of innovation in diplomacy. JCMS: journal of common market studies, 51 (4), 598–613.

- Bazerman, M.H., and Watkins, M.D., 2008. Predictable surprises: the disasters you should have seen coming, and how to prevent them. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

- Becker, S., Bauer, M.W., Connolly, S., et al., 2016. The commission: boxed in and constrained, but still an engine of integration. West European politics, 39 (5), 1011–1031.

- Bengtsson, L., Borg, S., and Rhinard, M., 2017. European security and early warning systems: from risks to threats in the European Union’s health security sector. European security, doi:10.1080/09662839.2017.1394845.1-21.

- Ben-Zvi, A., 1976. Hindsight and foresight: a conceptual framework for the analysis of surprise attacks. World politics, 28 (3), 381–395.

- Beswick, T. 2012. Improving institutional capacity for early warning. Available from: https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/20120100_beswick_institutional.pdf.

- Betts, R.K., 1978. Analysis, war, and decision: why intelligence failures are inevitable. World politics, 31 (01), 61–89.

- Betts, R.K., 1981. Surprise attack: NATO’s political vulnerability. International security, 5 (4), 117–149.

- Betts, R.K., 1982. Surprise attack: lessons for defense planning. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Biehl, H., Giegerich, B., and Jonas, A., 2013. Strategic cultures in Europe: security and defence policies across the continent. Berlin: Springer.

- Bøås, M., 2020. EU migration management in the Sahel: unintended consequences on the ground in Niger? Third world quarterly, 42 (1), 52–67.

- Boin, A., McConnell, A., and Hart, P.T., 2008. Governing after crisis: the politics of investigation, accountability and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Börzel, T., 2015. The noble west and the dirty rest? Western democracy promoters and illiberal regional powers. Democratization, 22 (3), 519–535.

- Brante, J., 2009. Strategic warning in an EU context: achieving common threat assessments. European security and defence forum, 1–16. London: Chatham House. Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/International%20Security/1109esdf_brante.pdf

- Bremberg, N., 2016. Making sense of the EU’s response to the Arab uprisings: foreign policy practice at times of crisis. European security, 25 (4), 423–441.

- Bürgin, A., 2018. Intra- and inter-institutional leadership of the European Commission President: an assessment of Juncker’s organizational reforms. JCMS: journal of common market studies, 56 (4), 837–853.

- Call, C.T., and Campbell S, P., 2018. Is prevention the answer? Daedalus, 147 (1), 64–77.

- Conrad, G., 2021. Situational awareness for EU decision-making: the next decade. European foreign affairs review, 26 (1), 55–70.

- Council of the European Union, 2022. A strategic compass for security and defence. Brussels: Council of the European Union. 64.

- Dahl, E.J., 2013. Intelligence and surprise attack: failure and success from Pearl Harbor to 9/11 and beyond. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Daun, A., 2005. Intelligence-Strukturen Für Die Multilaterale Kooperation Europäischer Staaten. Integration, 28 (2), 136–149.

- Echagüe, A., Michou, H., and Mikail, B., 2011. Europe and the Arab uprisings: EU vision versus member state action. Mediterranean politics, 16 (2), 329–335.

- Edwards, G., 1996. Early warning and preventive diplomacy: The role of the OSCE High Commissioner on national minorities. The RUSI journal, 141 (5), 42–46.

- Fägersten, B., 2014. European intelligence cooperation. In: I Duyvesteyn, B.D. Jong and J.V. Reijn, eds The future of intelligence: challenges in the 21st century. London: Routledge, 94–112.

- Farson, S., and Phythian, M., 2011. Commissions of inquiry and national security: comparative approaches. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- George, A.L., and Holl, J.E., 1997. The warning-response problem and missed opportunities in preventive diplomacy. New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York.

- Gerstein, M.S., and Schein, E.H., 2011. Dark secrets: face-work, organizational culture and disaster prevention. In: De Franco C and CO Meyer, eds. Forecasting, warning, and responding to transnational risks: Is prevention possible? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 148–168.

- Grabo, C., 2010. Handbook of warning intelligence: assessing the threat to national security. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

- Guttmann, A., Ikani, I., Meyer, C.O., and Michaels, E. 2022. Introduction: Estimative Intelligence and Anticipatory Foreign Policy. In; Meyer et al., eds. Estimative intelligence in European foreign policymaking. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1–26.

- Hammargård, K., and Olsson, E.-K., 2019. Explaining the European commission’s strategies in times of crisis. Cambridge review of international affairs, 32 (2), 159–177.

- Hart, D., and Simon, S., 2006. Thinking straight and talking straight: problems of intelligence analysis. Survival, 48 (1), 35–60.

- Henökl, T.E., 2015. How do EU foreign policy-makers decide? Institutional orientations within the European external action service. West European politics, 38 (3), 679–708.

- Heuer, R.J., 1999. Psychology of intelligence analysis. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Intelligence.

- Higgins, A. 2014. Ukraine upheaval highlights E.U.’s past miscalculations and future dangers. New York Times, 20 March 2014.

- Hollis, R., 2012. No friend of democratization: Europe’s role in the genesis of the ‘Arab Spring’. International affairs, 88 (1), 81–94.

- Howorth, J., 2011. The ‘new faces’ of Lisbon: assessing the performance of Catherine Ashton and Herman van Rompuy on the global stage. European foreign affairs review, 16 (3), 303–323.

- Ikani, N., 2021. Foreign policy change after the Arab uprisings. In Crisis and change in European Union foreign policy, 46–74. Manchester, Manchester University Press.

- Ikani, N., Guttmann, A., and Meyer, C.O., 2020. An analytical framework for postmortems of European foreign policy: should decision-makers have been surprised? Intelligence and National Security, 35 (2), 197–215.

- Jervis, R., 2010. Why intelligence fails: lessons from the Iranian revolution and the Iraq war. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Jervis, R., 2022. Why postmortems fail. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 119 (3), 1–6.

- Juncos, A.E., and Pomorska, K., 2014. Manufacturing Esprit de Corps: The case of the European external action service. Journal of common market studies, 52 (2), 302–319.

- Juncos, A.E., and Pomorska, K., 2021. Contesting procedural norms: the impact of politicisation on European foreign policy cooperation. European security, 30 (3), 367–384.

- Juppé, A. 2011. Closing speech by Alain Juppé, Ministre d’Etat, Minister of Foreign Affairs, to the Arab World Institute.

- Kagan, R., 2003. Of paradise and power: America and Europe in the new world order. New York: Knopf.

- Koops, J.A., and Tercovich, G., 2020. Shaping the European external action service and its post-Lisbon crisis management structures: an assessment of the EU high representatives’ political leadership. European security, 29 (3), 275–300.

- Krastev, I., and Leonard, M., 2015. Europe’s shattered dream of order: how Putin is disrupting the Atlantic alliance. Foreign affairs, 94 (3), 48–58.

- Kuus, M., 2013. Geopolitics and expertise: knowledge and authority in European diplomacy. Oxford: John Wiley.

- Lledo-Ferrer, Y., and Dietrich, J.-H., 2020. Building a European intelligence community. International journal of intelligence and counterintelligence, 33 (3), 440–451.

- MacFarlane, N., and Menon, A., 2014. The EU and Ukraine. Survival, 56 (3), 95–101.

- Maras, M.-H., 2017. Overcoming the intelligence-sharing paradox: improving information sharing through change in organizational culture. Comparative strategy, 36 (3), 187–197.

- Marrin, S., 2013. Rethinking analytic politicization, intelligence and national security. Intelligence and national security, 28 (1), 32–54.

- Mearsheimer, J.J., 2014. Why the Ukraine crisis is the West’s fault: the liberal delusions that provoked Putin. Foreign affairs, 93 (5), 77–89.

- Meyer, C. O., De Franco, C., and Otto, F., 2020. Warning about war: Conflict, Persuasion and Foreign Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mucha, W., 2017. The fairy tales of early warning research. Journal of contemporary central and Eastern Europe, 25 (2), 219–235.

- Natorski, M., 2015. Epistemic (un)certainty in times of crisis: the role of coherence as a social convention in the European Neighbourhood Policy after the Arab Spring. European journal of international relations. doi:10.1177/1354066115599043.

- Parker, C.F., and Stern, E.K., 2005. Bolt from the Blue or avoidable failure? Revisiting September 11 and the origins of strategic surprise. Foreign policy analysis, 1 (3), 301–331.

- Posner, R.A., 2005. Preventing surprise attacks: intelligence reform in the wake of 9/11. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Rovner, J., 2011. Fixing the facts: national security and the politics of intelligence. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Sakwa, R., 2014. Frontline Ukraine: crisis in the Borderlands. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Sakwa, R., 2015. The death of Europe? Continental fates after Ukraine. International affairs, 91 (3), 553–579.

- Seyfried, P.P. 2017. A European Intelligence Service? Potentials and limits of intelligence cooperation at EU level. Security Policy Working Paper no 20. Berlin: Federal Academy for Security, 1–5.

- Shapcott, W., 2011. Do they listen? Communicating warnings: a practitioners perspective. In: De Franco C and CO Meyer, eds. Forecasting, warning, and responding to transnational risks: is prevention possible? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 117–126.

- Teti, A., 2012. The EU’s first response to the ‘Arab Spring’: a critical discourse analysis of the partnership for democracy and shared prosperity. Mediterranean politics, 17 (3), 266–284.

- Tett, G., 2011. Silos and silences: the role of fragmentation in the recent financial crisis. In: Franco Cd and CO Meyer, eds. Forecasting, warning and responding to transnational risks: is prevention possible? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 208–216.

- Van Puyvelde, D., 2020. European intelligence agendas and the way forward. International journal of intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 33 (3), 506–513.

- Walshe, K., 2019. Public inquiry methods, processes and outputs: an epistemological critique. The political quarterly, 90 (2), 210–215.

- Weick, K.E., and Sutcliffe, K.M., 2007. Managing the unexpected: resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Whitman, R.G., and Wolff, S., 2010. The EU as a conflict manager? The case of Georgia and its implications. International affairs, 86 (1), 87–107.

- Wohlstetter, R., 1962. Pearl Harbor: warning and decision. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Woocher, L. 2011. Conflict assessment and intelligence analysis: commonality, convergence, and complementarity. Reportno. Special Report 275. Washington, DC: US Institute for Peace. Available at: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Conflict_Assessment.pdf