ABSTRACT

This article explores collective and individual perspectives on preschool mathematics within a professional development programme. All seven teachers at one Swedish preschool participated in a one-year research-based professional development programme. At the beginning and then again at the end of the programme, the teachers collectively wrote down their goals for mathematics teaching at the preschool. In the article, these goals will be compared to three teachers’ individual writings during the year. This comparison indicates that the professional development of these teachers may have been collective, but not joint, as the collectively written goals seem to imply slightly different things for the individual teachers. Thus, what may look like collective goals for the teaching of mathematics at one preschool may in fact imply quite large differences in the mathematics teaching of individual teachers. If collective professional development programmes are to have an impact, differences between teachers need to be made visible and, as a next step, be the basis for the development of professional language as well as evaluation and planning of preschool mathematics and further professional development.

Introduction

The basis for this article is a one-year research-based professional development programme in which all seven teachers from one Swedish preschool participated. The initiative for the professional development programme came from the preschool and, based on this initiative, the researcher acted as organiser and facilitator. In the article, the goals for mathematics teaching at this preschool, written collectively by the teachers at the start and end of the professional development programme, will be compared to three teachers’ individual writings during the year. The aim is to add knowledge to research on the professional development of early childhood mathematics teachers as well as to the research on professional development programmes. This will be achieved by addressing the following questions:

What changes can be found in the collectively written goals for mathematics education at the preschool?

What variation is there in the individual writings of three of the participating teachers?

Are there any connections and/or disconnections between these collective and individual writings?

Since individual differences are not unexpected in professional development programmes, the focus in the study is not a search for cause and effect. Neither is it a search for good, bad or un/wanted writings – collective or individual – from the teachers. Instead, the focus on change and variation in the two first questions are to be understood as the foundation for the third question focusing on connections and/or disconnections between collective and individual.

Research on the professional development of mathematics teachers can be sorted into studies focused on knowledge and/or beliefs, on the method used in the professional development programme or on the effectiveness of the professional development programme (Liljedal Citation2014). This article will address all these directions and especially their (eventual) mutual relationship. Furthermore, research on professional development generally focuses on change of some kind as the core of professional development is teachers developing their teaching for the benefit of students’ learning (Avalos Citation2011; Sowder Citation2007). Different approaches have been used in research on teacher change, for example, studies where teacher change is described as development through predefined stages (Sowder Citation2007), studies within beliefs research (including studies on attitudes, feelings and emotions), where fundamental questions concern whether beliefs are changeable or static, and how best to change beliefs if they are changeable (Phillip Citation2007), and studies focused on the knowledge possessed by or needed for teachers (Hill et al. Citation2007). All these orientations are based on an implied liaison between the stages, beliefs and/or knowledge and teachers’ teaching, however, there is no consensus regarding the features of this liaison (Avalos Citation2011; Hill et al. Citation2007; Liljedal Citation2014; Phillip Citation2007; Sowder Citation2007).

In this article, the change focused on in question one will not be based on predefined stages or external evaluation of beliefs or knowledge but instead on changes expressed in collective writings of the participating teachers. Thus, the changes focused on are those expressed by the teachers themselves why they may apply a variety of beliefs, knowledge, feelings and attitudes. These changes will in the article be compared to variation in three teachers’ individual writings with focus on connections and/or disconnections between these collective and individual writings. Finally, these connections and/or disconnections will be discussed in relation to the design of the professional development programme.

Professional development

According to Cochran-Smith and Lytle (Citation1999, 250), there are three ‘prominent conceptions of teacher learning’: knowledge for practice, knowledge in practice and knowledge of practice. Knowledge for practice is the acquisition of knowledge already known by others in, for example, teacher education. Knowledge in practice is teaching as a trade learned through teaching. Knowledge of practice is teachers’ using their own classroom to investigate learning, knowledge and theories. This last approach has become increasingly prominent in recent years, probably as a reaction towards studies showing that the two other approaches have had a limited impact (Avalos Citation2011; Sowder Citation2007). Two research overviews on professional development of teachers show that diverse forms of professional development programmes have effect but that prolonged interventions are more effective than shorter ones. Also, collaborations, combinations of tools as well as reflections on experiences are of positive value (Avalos Citation2011; Sowder Citation2007). The ‘power of teacher co-learning’ (Avalos Citation2011, 17) are emphasised since there is a greater chance of impact on classroom practice if groups of teachers work together over time.

In line with this, a knowledge of practice approach has been used in the professional development programme in this study. The approach involves reflection in and on practice as well as on external sources which imply that professional development is not something that is done to teachers but, instead, teachers are active learners shaping their professional growth through reflective participation (Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002). A challenge with such an approach is that teachers sometimes reinterpret new guidelines and their own teaching in ways that enable them to avoid changes (Morgan Citation2009). By reinterpreting their own teaching in line with the new guidelines, teachers do not experience any conflict between the teaching they are performing, or have performed, and new guidelines in the professional development programme. Based on such reinterpretations there may be a broad consensus among teachers while, at the same time, there are large differences in their mathematics teaching.

Swedish preschool

Preschool in Sweden is part of the formal education system and situated within a social pedagogy tradition where ‘care, socialisation and learning together form a coherent whole’ (National Agency for Education Citation2010). Preschool is offered to children between the ages of one and five and as part of the formal education system it has a curriculum. The social pedagogy tradition implies that preschool activities should involve a conscious use of play and that different ways of learning should be balanced and together form a whole.

The preschool should promote play, creativity and enjoyment of learning, as well as focus on and strengthen the child’s interest in learning and capturing new experiences, knowledge and skills. […] A sense of exploration, curiosity and desire to learn should form the foundations for the preschool activities. (National Agency for Education Citation2010, 9)

The preschool should strive to ensure that children develop their ability to use mathematics to investigate, reflect on and test different solutions to problems raised by themselves and others, as well as develop their understanding of space, shapes, location and direction, and the basic properties of sets, quantity, order and number concepts, and of measurement, time and change. Furthermore, the preschool should strive to ensure that children develop their ability to distinguish, express, examine and use mathematical concepts and their interrelationships as well as develop their mathematical skill in putting forward and following reasoning. These are not goals that children are expected to attain, but they provide a focus for teaching and learning. Based on the content in the curriculum, each preschool chooses the approaches most appropriate for its own setting. Thus, the curriculum does not express how to teach but a balance between different ways of learning are to be offered in the preschool (National Agency for Education Citation2010). Based on this freedom of approaches, differences in individual teachers’ perceptions of teaching mathematics may be of extra importance in the Swedish context, especially since the teachers work in teams and share teaching responsibilities.

Preschool teachers and child-minders are the two main types of pedagogue working in Swedish preschools. Child-minders must complete an upper secondary school education, while to become a preschool teacher, one must complete a three-and-a-half-year university course in preschool teacher education.

Theoretical framing

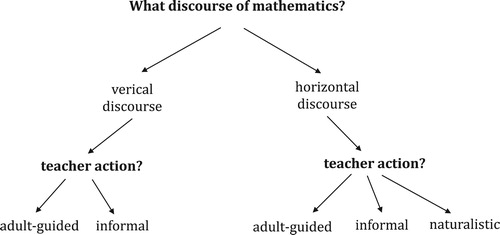

Studies show that it is possible for young children to possess mathematical competencies and that mathematical competencies possessed in the early preschool years have positive effects on later school performance (Cross, Woods, and Schweingruber Citation2009; Duncan et al. Citation2007). Based on this, there is a growing consensus in the research community that early mathematics plays an important role. However, there are differences of opinion when it comes to how preschool mathematics should be designed and what constitutes appropriate content (Palmér & Björklund, Citation2016). In this article, the notions vertical and horizontal discourses from Bernstein (Citation2000) and the notions naturalistic, informal and adult-guided learning experiences from Charlesworth and Leali (Citation2012) will be used to characterise collective and individual perspectives on preschool mathematics. The different notions will not be connected but used parallel as they have different emphases. Vertical and horizontal discourses focus on the discourse of mathematics, while naturalistic, informal and adult-guided learning experiences focus on the action – or non-action – of the teacher ().

A vertical discourse is characterised by its coherence of content, hierarchically interconnected procedures, specialised language, systematically organised activities and a focus on general knowledge, while a horizontal discourse is characterised by its location within communities, high relevance in the situation, everyday language, segmentally organised and maximised encounters with persons, and habits (Bernstein, Citation2000). Connected to preschool mathematics, vertical and horizontal discourses can be understood as two extremes. At one extreme mathematics is taught in hierarchically and systematically organised ‘lessons’ (vertical discourse), at the other extreme mathematics is considered to be part of everyday activities with no need to make it further explicit to the children (horizontal discourse). Of course, between these extremes, there is an endless variety of designs of preschool mathematics.

In line with , naturalistic, informal and adult-guided learning experiences will be used to characterise the action – or non-action – of the teachers within vertical or horizontal discourses. According to Charlesworth and Leali (Citation2012), naturalistic learning experiences are those initiated and controlled by the child without interference of any teacher. Examples of naturalistic learning experiences include building with blocks and setting a table for a doll’s tea party. If a teacher starts to interact with the child during such a naturalistic learning experience in a way that knowledge may be reinforced, applied or expanded, then the naturalistic learning experience turns into an informal learning experience. Thus, building with blocks or setting a table for a doll’s party can turn into informal learning experiences if, for example, a teacher asks how many blocks a child needs to build a high tower or challenges a child to give the smallest spoon to the smallest doll. Finally, adult-guided learning experiences are those that are pre-planned by the teacher and involve some direct instruction. Such adult-guided learning experiences may look different where Björklund (Citation2014) found how preschool teachers approached ‘the same’ mathematical learning object in different ways; by giving individual children traditional tasks, by hiding the learning objects within everyday problem-solving tasks or by using narrative contexts such as a story, a play or a game.

When used in parallel in the forthcoming analysis, naturalistic learning experiences (initiated and controlled by the child) can be understood as located within a horizontal discourse (mathematics being part of everyday activities with no need to make it further explicit to the children). If a teacher starts to interact with the child/children, turning the situation into an informal learning experience, the situation can still be regarded as initiated and located within a horizontal discourse (mathematics being part of everyday activities) but it is moving towards a vertical discourse (the teacher may, for example, introduce specialised language and/or focus on general knowledge). How big this move becomes of course depends on the teacher’s actions. Finally, adult-guided learning experiences as situations that are pre-planned by the teacher involving some direct instruction may be regarded as initiated within a vertical discourse but can be framed more or less towards a horizontal discourse. Thus, naturalistic learning experiences are always located within a horizontal discourse, while informal and adult-guided learning experiences may be located within a horizontal or a vertical discourse.

The study

The preschool is located in a medium-sized Swedish town, and at the time of the study 35 children aged 1–5 were enrolled. All seven teachers at this preschool were involved in the one-year professional development programme where the researcher acted as organiser and facilitator. The teachers and the researcher met for two hours after work each month from August 2014 to June 2015. Between these meetings, the teachers had both collective and individual tasks to perform and literature to read. Each cycle between meetings also included individual texts to be written. At each meeting, the completed tasks were evaluated and discussed, and the researcher showed videos and held short lectures and introduced the tasks for the next cycle. An overview of the professional development programme is provided in Appendix. All requirements for information, approval, confidentiality and appliance advocated by the Swedish Research Council (Citation2011) were followed.

The teachers were all female, three of them were educated as preschool teachers, one as a child-minder, and one as a primary teacher, and the other two had no teacher education. Three of the teachers had been working at the preschool for over 20 years, 3 had been there between 8 and 15 years, and 1 had been working there for 2 years. In the article, these seven teachers’ collective writings in the beginning and at the end of the professional development programme will be focused on. While these teachers are similar to each other in many respects, they are also unique, and three of the teachers will be followed as individual cases. These cases were selected because none of them had a preschool teacher education, none of them had taken any previous courses in mathematics education, all three of them attended all meetings during the year, and together they illustrate the differences found in the study as whole. These teachers are referred to in the article as Aida, Kalie and Gaby. Aida is 41 years old, educated as a child-minder and has worked at the preschool for over 20 years. Kalie is 45 years old, educated in pedagogy and history at the university level and has worked at the preschool for 9 years. Gaby is 54 years old and has no formal teacher education but has previously worked in advertising. She has worked at the preschool for two years.

According to Atkinson (Citation1998), narratives is the best way to research individuals’ unique experiences and perspectives on events. Similarly, Cortazzi (Citation2001) writes that narratives make it possible to distinguish others’ perspectives on particular themes or processes and to develop an understanding of the meaning individuals give to themselves and to their contexts.

[…] narratives refer to the self-authored, written or oral stories, which allow teachers to present their teaching or learning experiences from their perspectives and to weave descriptions of their thinking, feelings, attitudes, and other personal attributes relevant to these experiences into their stories. (Chapman Citation2008, 18)

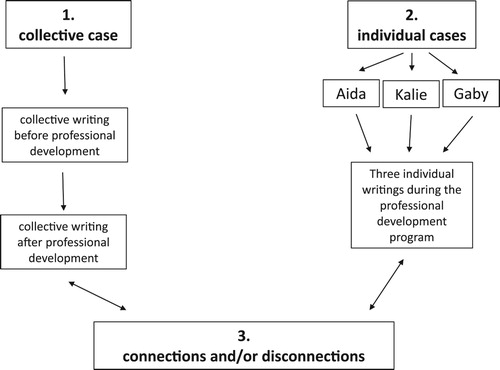

In this article, the narratives to be analysed are the collective writings of the seven teachers at the start and end of the professional development programme together with individual writings of Aida, Kalie and Gaby. To begin with, the collective writings are analysed to answer the first research question (what changes can be found in the collectively written goals for mathematics education at the preschool?). The changes focused on in that analysis are those expressed by the teachers in their narratives, for example, where the teachers write before … but now we want to work more … are considered as implications of change. Based on the teachers’ writings these expressed changes can be about actions, beliefs, attitudes, views and feelings. Second, the individual writings are analysed to answer the second research question (what variation is there in the individual writings of three of the participating teachers?). Both the collective and the individual writings are analysed based on vertical and horizontal discourses from Bernstein (Citation2000) and the notions naturalistic, informal and adult-guided learning experiences from Charlesworth and Leali (Citation2012) as presented in the previous section. Finally, to answer the third research question (are there any connections and/or disconnections between these collective and individual writings?) the individual writings are compared to each other and to the collective writings. provides a schematic overview of the steps and the empirical material used in the analysis.

The aim is to get to know these collective and individual cases well, not primarily to understand how they differ from other cases but to understand these cases as such (Stake Citation1995). Despite this, context similarity and recognition of patterns are two possible way to generalise (Larsson Citation2009). Context similarity implies focusing on the similarities of the researched context and other contexts, while generalisation by recognition of patterns implies focusing on the similarities of the researched patterns and other patterns. A precondition for these kinds of generalisation is knowledge of the ‘other context’, why ‘thick description’ becomes central when presenting the results. To be able to understand the changes expressed, both the individual and the collective, these expressions need to be presented with thick descriptions.

Results

As presented above, first the collectively written goals for the mathematics teaching at the start and end of the professional development programme will be focused on. After that, the individual teachers will be presented based on three writings during the year. Finally, the connections and/or disconnections between collective and individual writings will be focused on.

What changes can be found in the collectively written goals for mathematics education at the preschool?

The first task for the teachers, before they met the researcher in person, was to collectively write down their goals for mathematics teaching at the preschool. The teachers wrote that ‘[m]athematics is a natural and repeated element in the everyday activities at the preschool’. Furthermore, they wrote that they wanted to ‘base [their] mathematics teaching on children’s interest and on everyday activities’. The argument for this approach was that it would make mathematics ‘meaningful’ for the children. Through a ‘conscious way of working’, the teachers wanted to ‘expand children’s experiences of mathematics’ and ‘make each other and the children aware’ of the concepts they were using. They wrote about the importance of developing children’s mathematical vocabulary and letting the children ‘look, listen, do and feel mathematics’.

These writings are based in a horizontal discourse where mathematics is considered to be part of everyday activities (‘[m]athematics is a natural and repeated element in the everyday activities at the preschool’ – ‘base […] mathematics teaching on children’s interest and on everyday activities’). The way the teachers wrote about their own actions can be understood as them using these naturalistic learning experiences, as initiated and controlled by the children, to interact with the children, turning the situations into informal learning experiences (‘expand children’s experiences of mathematics’ – ‘developing children’s mathematical vocabulary’ – ‘look, listen, do and feel mathematics’).

In the end of the professional development programme, the teachers still expressed a desire to work consciously with mathematics, but now they wrote that they wanted to work ‘more consciously [of mathematics] as a natural element in the everyday activities’ (italics added by the author). They emphasised that ‘[m]athematics is a natural and repeated element in the everyday activities in preschool’ and that, in their preschool, they are to ‘expand children’s experiences of mathematics’. Also similar is that they wrote about encouraging children to ‘look, listen, do and feel mathematics’. Just as they wrote ‘more conscious’ they also expressed that they had to use ‘more concepts’ and ‘ask more problem-solving questions’. This use of more indicates change. They still want to work consciously with concepts and problem-solving but not in the same way as they did before becoming involved in the professional development programme. The writings are based in a horizontal discourse where mathematics is considered to be part of everyday activities, but the teachers’ reference to the idea of more can be understood as them thinking of informal learning experiences being increased in both amount and importance.

New writings at the end of the professional development programme were about problem solving and an intention to ‘give children time to think by themselves’ and ‘encourage children’s own initiatives, autonomy and influence’ and also a desire to be ‘more active as participants in children’s own play’. These writings indicate a movement towards an even more horizontal discourse with naturalistic learning experiences initiated and controlled by the children. Thus, at the same time as the teachers were expressing that they wanted to work ‘more conscious’ with mathematics and to use ‘more concepts’, they wanted to base these in an even more horizontal discourse.

To summarise, the collective writings indicate a movement from a horizontal discourse towards an even more horizontal discourse where children have influence and autonomy but are met in informal learning experiences by even more conscious teachers using more concepts and asking more problem-solving questions.

What variation is there in the individual writings of three of the participating teachers?

The cases of Aida, Kalie and Gaby

This part will be based on three individual writings carried out during the professional development programme. Each writing will be evaluated based on similarities and differences between the three teachers.

Write about two ‘situations of mathematics’ where you are involved

Before the second meeting, the teachers were to write about two ‘situations of mathematics’ from their preschool where they were involved.

Aida: Aida gave one example from circle time, writing that every day they count how many children there are in the circle. Her other example was from eating breakfast, where one child one day started to compare the sizes of a big spoon and a small spoon.

Kalie: Kalie gave one example from circle time, where she gave children instructions about where to put a fruit, for example, on, under or behind a chair. Her second example was a meal situation where two children were discussing where everyone should sit, for example, ‘you can sit next to or between’.

Gaby: Gaby gave only one example which was from circle time. She had used spiders of different sizes and the children were given instructions based on the notions of big, small, smaller, etc.

Similarities and differences: All three teachers wrote about circle time, and those examples can be understood as adult-guided within a vertical discourse. Aida’s and Kalie’s second examples can be viewed as naturalistic situations within a horizontal discourse. In their descriptions of these situations they did not write anything about their own involvement, but only about what the children were doing and saying. Thus, these situations are not described as turning into informal learning experiences.

Plan and carry out an activity involving construction

Before the third meeting, the teachers were to read two texts, one about mathematics in construction play and one about concepts. The text about construction play included both child- and adult-initiated activities where interaction between teachers and children was very evident. The individual task was to plan and carry out an activity involving construction. Preferably, the activity was to involve some concepts they identified as ones they used less often or never.

Aida: Aida gave the children the task of building a hut in a big room at the preschool. The hut was to be big enough for all of the children to fit inside. The children were to figure out what material to use and how big the hut needed to be. She included all children present at the time in the activity. She wrote, ‘I want to unleash children’s creativity’ and involve ‘concepts such as big, bigger, biggest and many, more, most’. She evaluated the activity as ‘very fun’ with ‘many good solutions from children on how to make the hut bigger so that everyone could fit inside’. She described how the children continued to play with the hut, which was left in the room for the whole day.

Kalie: Kalie cut out one circle, one triangle and one square, each in a different colour. The figures were of different sizes. Then she sat down with two children in a separate room. She asked the two children questions about the figures, for example, about their shape, colour and size. After that, she gave the children instructions of how to put beads on the figures, for example, ‘put the bead on the triangle’. She evaluated the activity as the children acting as she expected them to perform and that she maybe should have started differently, with colour instead of shape since colour is easier. She also evaluated the knowledge expressed by the children, where the child who managed to answer the question ‘succeeded’.

Gaby: Gaby’s individual activity involved having four children build a house for the toy spiders that she wrote about in the previous task. She had cut pieces of Styrofoam in different sizes beforehand, and wrote that she had ‘her own idea of what the house might look like’. She wanted to explore how the children would handle length and size when building and she deliberately cut more pieces of Styrofoam than would be needed to build a house. Before the children began to build the house, she had them count the spiders and asked them ‘how many rooms’ the house must have. As there were seven spiders, the children started to build a house with seven rooms. She wrote that they talked about the shapes of the leftover pieces when the house was finished. She evaluated the activity by writing that she ‘was impressed with how quickly they built the house and ‘how similar it was to my initial conception’. Furthermore, she wrote that ‘[y]ou could see how eager they all were as they worked and how proud they were of their building’.

Similarities and differences: The three activities were adult guided (logical considering the task they were given) but quite different. If comparing to the diverseness of adult guides activities presented by Björklund (Citation2014), Aida and Gaby frame their activities within a narrative frame while Kalie uses direct instruction. In Aida’s and Gaby’s activities mathematics is used as a tool in construction play. They framed their activities within a play or a game (playing with the spiders) while Kalie’s activity took the form of a more traditional task. Kalie’s activity can be considered to be within a vertical discourse, Aida’s activity within a horizontal discourse and Gaby’s activity somewhere in the middle. There is a big difference regarding children’s initiatives, autonomy and influence in the three activities. Children’s experiences, interests, needs and views can be the basis for adult-guided activities, which was apparent in the articles read before the task. The building and construction aspect is very visible in both Aida’s and Gaby’s activities but absent in Kalie’s. The instruction to involve concepts was interpreted by Kalie and Gaby mainly as talking about concepts. Aida wrote about which concepts she thought were included in the activity but she did not write about how they were included – whether only by experiencing them or by experiencing and talking about them. Aida emphasised children’s creativity in her writing, which is in line with the national curriculum, and she wrote about play. However, play was not connected to the implementation of the task; rather, it occurred after the task was finished.

Plan and carry out an optional activity

The next time the teachers were to plan and carry out an activity of their own was as preparation for the eighth meeting which was at the end of the professional development programme. This time they were to plan an optional activity. Before the same meeting, the teachers were also to read two texts about problem-solving, and prior to the seventh meeting, they had read examples of problem-solving activities carried out at other preschools.

Aida: Aida framed ‘the task by giving it to the children during a whole-day trip in a forest nearby’. At snack time, the children were going to eat some fruit. But she told them that the teachers had forgotten to bring all the fruit. All they had was four pears to be shared by 16 children and two adults. The question put to the children was, ‘What should we do now?’ Aida wrote that she wanted children to solve ‘the problem’ together and she described how the whole group of children got involved, how they cut and counted. Finally, all pieces were the same size and they ended up with three small pieces of pear each. Aida evaluated the activity by writing that the children were ‘engaged’ and gave ‘many suggestions’ about how to solve the problem. She also wrote that both she and the children talked a lot about ‘whole and half’, which was ‘one aim’ of the activity.

Kalie: Kalie had printed pictures of cats, two mummies and 12 kittens, before the activity began. The activity was conducted with two children in a separate room. She told the children that the ‘kittens have run away’ and asked the children if they could ‘return each kitten to their mum’ putting all the pictures on the floor. Kalie did not write anything about which mathematical concepts she or the children were using, and no mathematical goal was expressed. In her evaluation, she wrote that the activity was a problem-solving task and that the children did not sort the kittens as she had expected.

Gaby: Gaby’s activity was about packing a suitcase with the goal for the children to count to five, to compare sizes and to explore space. The activity was done with four children in a separate room. Gaby framed the activity as a story where five animals were going on a trip and had to be packed into a suitcase. She had brought one quite small suitcase and a lot of cuddly animals of different sizes. When packing, the teacher chose one animal and then the children were to choose one each. After this, they were to pack the suitcase and see if the animals fit. If they did not fit, the children were asked, ‘What should we do if they do not fit?’ In her evaluation, she wrote that size and different solutions were made visible to the children through the activity.

Similarities and differences: Both Gaby and Aida expressed the mathematical goal with their activities, which were adult guided in a horizontal discourse. If comparing to the diverseness of adult guides activities presented by Björklund (Citation2014), Aida hides the learning objects within an everyday problem-solving task, Gaby uses a narrative frame while Kalie uses direct instruction. Gaby framed her activity as a story and Aida as a problem that needed to be solved in reality. This can be understood as them trying to base the activities in children’s experiences as emphasised in the national curriculum. Gaby guided the children more than Aida, but the activity was still within a horizontal discourse. In both Aida’s and Gaby’s activities the children were given autonomy as they were given open questions. In Kalie’s activity, too, the children were given autonomy, but Kalie did not express any goal with the activity. She wrote that they did not sort the kittens as she had expected but she did not write what she had expected.

Are there any connections and/or disconnections between these collective and individual writings?

The collective writings indicated a movement from a horizontal discourse towards an even more horizontal discourse where children have influence and autonomy but are met by more conscious teachers using more concepts and asking more problem-solving questions. However, the majority of the three teachers’ individual activities are adult guided. This may partly be explained by the activities being part of the professional development programme but still, the instructions gave room for children’s experiences, interests, autonomy and views, as well as play and creativity as emphasised in the national curriculum (National Agency for Education Citation2010). In their adult-guided activities, Aida and Kalie frame the activities as narratives or everyday problem-solving tasks while Gaby uses direct instruction. Thus, Aida and Kalie frame their adult-guided activities within a horizontal discourse in line with the collective writings while Gaby mainly frames her activities within a vertical discourse.

In the collective writing, the teachers write about being ‘more active in participating in children’s own play’ and about ‘play is a good opportunity to introduce and inspire mathematics’. In the individual writings, a conscious use of play, as well as children’s experiences, interests, autonomy and views, is however almost invisible. Through all the tasks, Aida is the one who involved several or all of the children and who promoted autonomy, influence and problem-solving. She often expressed mathematical goals for the activities in line with the collective ‘more conscious and more concepts’. Gaby’s activities were quite similar to Aida’s but closer to a vertical discourse, and she often chose to work with few children. Kalie seldom emphasised the mathematics in the activities, which were most often adult guided within a vertical discourse with only one or two children present. When she was to work with problem-solving, the mathematics got lost.

Thus, some of the notions used by the teachers in the collective writings seem to imply slightly different things for the individual teachers in their individual activities. When planning the optional activity all three teachers refer to problem-solving, but the activities they describe are quite different. The collective writings about more problem-solving questions seem to imply different things for the three teachers. Similar, the collective writings about more conscious teachers and using more concepts seem to imply different things for the three teachers. Thus, there seem to be ambiguities in the professional language used by the teachers where notions imply different things when implementing them in activities.

To summarise, the three teachers seem to have worked quite differently with mathematics during the professional development programme even though they have continuously reflected on literature and experiences and worked together to write the collective goals for their work with mathematics.

Conclusions and implications

What is quite unique for this study is that the collective changes focused on are those expressed by the teachers in their narratives and not changes attributed to them by the researcher. Also, the empirical material makes it possible to provide thick descriptions and by that to understand how the individual teachers implement the collective writings in their activities. As been shown, there are disconnections between the collective and the individual writings. Thus, the results indicate that the professional development may have been collective but not joint. Based on the writing of the teachers’ the collective goals for mathematics at the preschool have changed, but when carrying out activities these goals seem to imply slightly different things for the three teachers. In research on collective professional development, differences in school culture is one usual explanation for such differences (Avalos Citation2011). That explanation is however not applicable in this study since all teachers are from the same preschool.

Individual differences are not unexpected in professional development programmes, and maybe the differences found in this study can be connected to how these three teachers usually teach in preschool. Even though they work at the same preschool they may work very different, even before the professional development programme. As mentioned, one challenge with a knowledge of teaching approach is the reflective participation which makes it possible for teachers to reinterpret new guidelines and their own teaching in a way that enables them to avoid actual change (Morgan Citation2009). Based on such reinterpretations there can be broad consensus among teachers while at the same time there are large differences in their mathematics teaching which seems to be the case in the study presented here.

One reason for choosing a knowledge of practice approach in the professional development programme was research showing that if groups of teachers work together over time to develop their educational practice, then there is a greater chance of having an impact on classroom practice (Avalos Citation2011; Sowder Citation2007). Furthermore, professional development programmes should be based on solid research findings (Tsamir et al. Citation2011), which was another reason for choosing a knowledge of practice approach. Both the collective and the individual writings indicate that the professional development programme has had an impact on classroom practice, but not a joint impact. The approach makes it possible for the participants to have influence and autonomy – maybe too much autonomy. When these three teachers, for example, are to use more problem-solving questions and more concepts, they will probably use quite different kinds of questions in different kinds of activities. Differences in interpretations of teaching approaches (for example, more problem-solving questions, more conscious teachers and using more concepts) may result in difficulties when it comes to balancing the teaching approaches (National Agency for Education Citation2010) at the preschool. Vague descriptions of what and how in curriculums ascribe teachers a central role in curriculum enactment (Skott Citation2004). Without a joint professional language, such an enactment resulting in the requested balance between teaching approaches emphasised in the curriculum becomes difficult to achieve.

Differences between teachers are however probably not unique to this professional development programme – quite the opposite and highlighting differences does not imply that all teachers must express and/or act exactly the same for a professional development programme to be considered as successful. However, professional development programmes ought to make differences visible to the participants. If differences are not made visible they cannot be discussed, and participating teachers will believe that they share the same understandings and the same teaching practices when in fact they do not. If collective professional development programmes and collective writing are to have an impact on practice, differences need to be made visible and, as a next step, be the basis for both evaluation and planning of further professional development. In the knowledge of practice approach, continuous reflection on literature and experiences are emphasised. One way to develop the approach could be to reflect on joint experiences instead of individual experiences, for example, by using co-teaching or video-recorded situations. Reflections on joint experiences could make differences in interpretation of words and practice visible and develop the professional language. In this study, discussions could have been raised based on differences in the teachers’ individual writings, but such discussions become ethically tricky in that they could make the teachers uncomfortable.

To summarise, the findings and implications presented in this article offer insights for both educators and teachers involved in similar professional development programmes. Furthermore, it adds knowledge to research on the professional development of early childhood mathematics teachers. What may look like collective goals for the teaching of mathematics at one preschool may in fact imply several different things for individual teachers. The empirical material presented in the article makes connections and/or disconnections between individual and collective changes visible, thus both teachers and educators can gain insight from the collective and individual cases based on context similarity and recognition of patterns. Finally, educators can gain insight from the article about how to further develop professional development programmes with a knowledge of practice approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Atkinson, R. 1998. The Life Story Interview. Qualitative Research Methods Series. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Avalos, B. 2011. “Teacher Professional Development in Teaching and Teacher Education Over Ten Years.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (1): 10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Björklund, C. 2014. “Powerful Teaching in Preschool – a Study of Goal-Oriented Activities for Conceptual Learning.” International Journal of Early Years Education 22 (4): 380–394. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2014.988603

- Chapman, O. 2008. “Narratives in Mathematics Teacher Education.” In The International Handbook of Mathematics Teacher Education: Tools and Processes in Mathematics Teacher Education, edited by D. Tirosh and T. Wood, 15–38. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Charlesworth, R., and S. A. Leali. 2012. “Using Problem Solving to Assess Young Children’s Mathematics Knowledge.” Early Childhood Education Journal 39: 373–382. doi: 10.1007/s10643-011-0480-y

- Clarke, D., and H. Hollingsworth. 2002. “Elaborating a Model of Teacher Professional Growth.” Teaching and Teacher Education 18 (8): 947–967. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. L. Lytle. 1999. “Chapter 8: Relationships of Knowledge and Practice: Teacher Learning in Communities.” Review of Research in Education 24 (1): 249–305. doi: 10.3102/0091732X024001249

- Cortazzi, M. 2001. “Narrative Analysis in Ethnography.” In Handbook of Ethnography, edited by P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J. Lofland, and L. Lofland, 384–394. London: SAGE Publications.

- Cross, C. T., T. A. Woods, and H. Schweingruber. 2009. Mathematics Learning in Early Childhood: Paths Toward Excellence and Equity. Washington, DC: National Research Council of the National Academics.

- Duncan, G. J., C. J. Dowsett, A. Claessens, K. Magnuson, A. C. Huston, P. Klebanov, L. S. Pagani, et al. 2007. “School Readiness and Later Achievement.” Developmental Psychology 43: 1428–1446. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428

- Hill, H. C., L. Sleep, J. M. Lewis, and D. Ball. 2007. “Assessing Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge: What Knowledge Matters and What Evidence Counts?” In Second Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning, edited by F. K. Lester, 257–315. Charlotte, NC: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics & Information Age Publishing.

- Liljedal, P. 2014. “Approaching Professional Learning: What Teachers Want.” The Mathematics Enthusiast 11 (1): 109–122.

- Larsson, S. 2009. “A Pluralist View of Generalization in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 32 (1): 25–38.

- Morgan, C. 2009. “Making Sense of Curriculum Innovation and Mathematics Teacher Identity.” In Innovation and Change in Professional Education 5. Elaborating Professionalism. Studies in Practice and Theory, edited by C. Canes, 107–122. London: Springer.

- National Agency for Education. 2010. Curriculum for the Preschool Lpfö98. [Revised 2010]. Stockholm: National Agency for Education.

- Palmér, H., and C. Björklund. 2016. “‘Different Perspectives on Possible – Desirable – Plausible Mathematics Learning in Preschool.” Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education 21 (4): 177–191.

- Phillip, A. R. 2007. “Mathematics Teachers’ Beliefs and Affect.” In Second Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning, edited by F. K. Lester, 257–315. Charlotte, NC: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics & Information Age Publishing.

- Skott, J. 2004. “The Forced Autonomy of Mathematics Teachers.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 55 (1–3): 227–257. doi: 10.1023/B:EDUC.0000017670.35680.88

- Stake, R. E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London: SAGE Publications.

- Sowder, J. T. 2007. “The Mathematical Education and Development of Teachers.” In Second Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning, edited by F. K. Lester, 157–224. Charlotte, NC: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics & Information Age Publishing.

- Swedish Research Council. 2011. God Forskningssed [Good Custom in Research]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Tsamir, P., D. Tirosh, and E. Levenson. 2011. “Windows to Early Childhood Mathematics Teacher Education.” Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education 14: 89–92. doi: 10.1007/s10857-011-9174-z

Appendix

In the table, the professional development programme is briefly described. At each meeting, the conducted homework was evaluated and discussed. Based on different themes, the researcher showed videos and held short lectures. Finally, the homework for the next meeting was introduced. Before meeting 1 the participants were to collectively write down the goals for mathematics teaching at the preschool based on the question what experience of mathematics should children get at our preschool and how? Italicised text in the table indicates material used in the article.