Abstract

Governments are obligated to safeguard social inclusion for disabled people through user-led personal assistance (PA) under Article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). This scoping review was carried out to map and explore current knowledge on how governments internationally have managed PA schemes in response to the UNCRPD. The review examined 99 documents, and categorised the literature into the following themes; legislation, funding, model of service provision, governance and regulation, and the COVID-19 pandemic response. We include recommendations to co-design legislation and quality improvement policies to ensure that PA schemes are underpinned by a social model of disability mindset. Further research needs to be undertaken to guarantee that policymakers include the voice of PA users in the management of PA schemes.

This article looked at 99 documents to find out how governments are managing personal assistance (PA). It found out that governments can often decide to spend less money on a PA scheme rather than protect our rights.

To overcome this problem the documents recommended that legislation for PA schemes must be designed with disabled people. Governments must redirect their money from institutional services to community-based services. Eligibility criteria to control access and the costs of PA should be removed.

This paper suggests that we need to have the voice of the PA user to direct the design and delivery of PA schemes.

Points of interest

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1877114

Introduction

This article explores how governments have managed personal assistance (PA) schemes following the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). This research is informed by the social model of disability, in which the implicit assumption is that the environment, economic, and cultural barriers result in a disability, not a persons impairment (Barnes Citation2007). The purpose of a PA scheme is to support a person to have choice and control over their lives and overcome such barriers (Dejong and Lifchez Citation1983).

Due to the context-specific variation between countries, different models of PA schemes have emerged and can be broadly categorised into two categories. First, a provider-led model, where the provider has the most choice and control over the service. The second category is a user-led model and aligns with the independent living philosophy. It is delivered with an individualised budget or direct payment and can be categorised into three sub-categories. Category one, a person manages the service and undertakes all administration duties and responsibilities. Category two, is when an agency manages the administration of the service, but PA users have control over scheduling decisions. Category three, a co-op model, in which the agency is run by people who also use the service (Askheim Citation2005). In the 1970s in America, the independent living movement emerged, and since then, it has transcended internationally advocating for disabled peoples’ rights to live independently (Dejong Citation1979). The work of this movement is supported by Article 19 of the UNCRPD which emphasises a person’s right to PA to facilitate their independent living and inclusion in society (United Nations Citation2006).

The main question of this review is; how have governments managed PA schemes in response to the UNCRPD? The results were categorised into five themes, legislation, funding, the model of service provision, governance and regulation, and the COVID-19 pandemic response. The remainder of the article will discuss the methodological approach taken to scope the literature and address the research question. The findings are then presented in the results section, which is followed by a discussion of results and implications for policy, practice, and research.

Methods

This paper uses a scoping review methodology to explore how governments have responded to the UNCRPD to provide a means to synthesise a range of literature on the topic of PA schemes, to evaluate the need for further research and reviews, and subsequently disseminate research findings (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). Scoping reviews are not exhaustive, nor do they evaluate the quality of the research. Instead, they provide broad coverage of the topic to map the landscape of existing research and do not exclude literature based on study types (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010; Peters et al. Citation2017). This study design was chosen as it is flexible enough to map heterogenic literature within broad research areas to identify critical factors relating to the topic (Peters et al. Citation2015; Tricco et al. Citation2018; Munn et al. Citation2018). This study follows a methodological framework devised specifically for scoping reviews (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005; Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010).

Stage 1: identification of the research question

This study requires flexibility as there are inconsistencies in how PA is defined and understood in different countries. To scope the relevant literature, the authors have developed the following working definition of PA; a social service, not bound to a particular setting such as the home, place of work or education, that has the option of an individual budget to facilitate a person to undertake activities of daily living. The main question of this review is; how have governments managed PA schemes in response to the UNCRPD?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

The search strategy aimed to discover academic and grey literature, along with expert opinion. Firstly, a draft search of two databases was undertaken (Tricco et al. Citation2018; Peters et al. Citation2017). A pilot search of CINAHL and MEDLINE was conducted on 26 March 2019 using the terms, ‘personal assistance’ AND ‘government’ OR ‘Quality AND (outcomes OR indicators)’. This pilot search revealed limited literature on the topic. Thus, a broader search strategy was designed to locate all relevant literature and avoid missing relevant studies (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). A broad search string of ‘(personal assistan* OR PAS) AND (disability or disabilities or disabled or impairment or impaired or special or special needs or special education) OR (intellectual disability or learning disability or developmental disability or learning disabilities) OR (physical disability or disabled or mobility impairment)’. The search for academic literature was performed using the following databases: SCOPUS, CINAHL, and MEDLINE. The grey literature search included the databases; BASE, WorldWideScience, and Google using the search string ’personal assistan* service’ AND disability’. This search also included the websites of international organisations; European Network on Independent Living (ENIL), the Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED), and the Independent Living Institute (ILI). The searches were initially performed in April 2019 and again in July 2020, to include literature published since the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the reference lists of the documents selected for inclusion were screened for additional relevant documents.

Stage 3: study selection

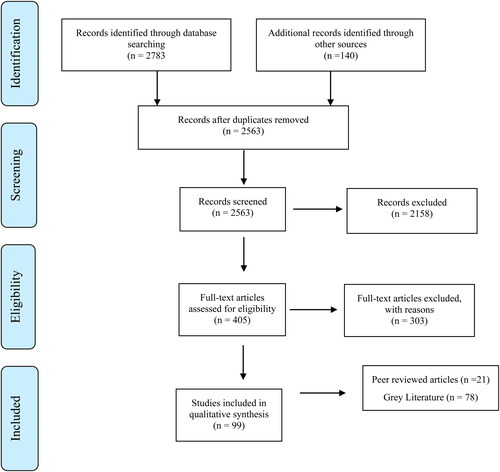

As expected, the broad search strategy generated a large number of references (2923) which inevitably included irrelevant studies. Firstly the duplicates were removed, and the remaining 2563 references were grouped in Endnote by relevance and subject matter and screened for suitability by reading their title and abstract (King, Hooper, and Wood Citation2011). Following this, the references were selected based on the following inclusion criteria; literature relating to people aged between 18 and 65, in English, and published after the UNCRPD was adopted by the United Nations and open for signatures in 2007 (Department of Economic and Social Affairs n.d.). Any literature that did not examine the scheme from the viewpoint of the social model of disability were excluded. Also excluded were services that were limited to educational, workplace, or home settings. No documents were excluded based on its country of origin or type of sources. Any text or opinion-based evidence included was the opinion of an expert in the area of PA.

After the 2563 articles were screened using the inclusion criteria, 405 documents were included. The full text was retrieved and screened for each document. After this full text screen, 99 studies were included, and their analysis was reviewed independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. Please see the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram for an overview of this process (see ).

Stage 4: charting the data

The literature was charted in a uniform approach to obtain key issues and themes (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). The data extracted included specific details about the finding’s significant to the review question. To ensure the results were reported consistently, the following headings were used to chart the literature; author/s, year of publication, country of origin, and legislation, funding, the model of service provision, governance and regulation, and COVID-19 response. These headings were created after an initial familiarisation with the 99 studies and reviewed in light of the updated search in July 2020. The final versions of the charting forms are included in Appendices I and II.

Stage 5: collating, summarising, and reporting the results

The results are presented in this article with a numerical summary and narrative description of the included studies. Descriptive thematic analysis was undertaken to identify potential factors related to government management of PA (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010). The literature was collated, and a table was developed to provide a summary of how governments are delivering PA schemes in each country (see ). The results are reported, in the next section, according to the themes identified during the analysis of the literature. Finally, the discussion section considers the implications of these results for policy, practice, and research (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien 2010).

Table 1. The factors highlighted in the ENIL surveys and ANED country reports that influence the government’s management of PA.

Results

The literature found through the scoping review includes; academic papers (n = 21) and grey literature (n = 78) which spans 40 countries. A table detailing the characteristics and the main findings of each study are included in Appendices I and II. The academic literature focused on various countries, 12 papers focused on Scandinavia, three papers examined PA schemes in America, one paper explored the schemes in Switzerland, Germany, the UK, and Sweden, finally, there was a paper apiece for the UK, Bulgaria, and Korea. The grey literature included 26 country surveys which were administered by ENIL and completed by experts on PA schemes. Also included are ANED reports which evaluate the compliance of 35 countries to Article 19 of the UNCRPD. The literature was analysed thematically to answer the review questions and was categorised under the following themes; legislation, funding, the model of service provision, governance and regulation, and COVID-19 pandemic response (see Appendices I and II).

Legislation

The topic of legislation to ensure a right to PA, and to remove inequalities created by the regional variation is particularly evident in the literature (ENIL Citation2015, 1; Christensen, Guldvik, and Larsson Citation2014; Brennan et al. Citation2018; Mladenov Citation2020, Citation2017). The legislation framework can be either part of an existing social services act or an independent statutory piece of legislation (Askheim Citation2008). A legal framework for PA schemes existed in 18 countries, 19 countries do not have a legal framework, and the reports for three countries had no data on this topic (see ).

It was identified from the literature that strong laws and policies are not enough to protect a person’s right to live independently (Brennan et al. Citation2016, Citation2018). The literature provided two cases where the legislation did not protect PA users right to live independently. Firstly, in Iceland, Norway, and Sweden the governments developed cost-containment strategies by placing strict limitations on the eligibility criteria, this resulted in limited or reduced services for PA users (Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016; Rauch, Olin, and Dunér Citation2018; von Granitz et al. Citation2017; Brennan et al. Citation2017). Secondly, in Sweden, court rulings and recent changes to the PA scheme have forced people to apply to their local authority, leaving them vulnerable and dependent on the local level interpretation of policies and laws (Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016; von Granitz et al. Citation2017; Brennan et al. Citation2017; Rauch, Olin, and Dunér Citation2018). This is particularly problematic as some local authorities are resistant to implement the legislation or to make the changes needed within the system as ‘bureaucrats are afraid to lose power’ (Brennan et al. Citation2018, 25; Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016). Therefore, to protect people from local level variation and ‘postcode lottery’ there have been calls for a universal right to independent living where supports, such as PA, would be delivered through a central national service rather than local governments (Graby and Homayoun Citation2019).

Government funding

The cost controlling and cost-cutting efforts by governments is a recurring theme in the literature and is seen as a significant barrier to a user-led service (Mladenov Citation2020). Denmark, Italy, Hungary, Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK have recently decreased spending on PA (Bengtsson Citation2019; Brennan et al. Citation2018; ENIL Citation2015; Gyulavári, Gazsi, and Matolcsi Citation2019). The Swedish government introduced cost controlling strategies which have increased the number of people losing state-funded PA. These strategies have resulted in an increase in rejected applications as it is harder to get access to PA for first-time applicants with access to the scheme being limited to those with the most need (Brennan et al. Citation2016; Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016; Rauch, Olin, and Dunér Citation2018). In the UK, the Independent Living Fund (ILF), a source of cash payments for PA, has closed, resulting in a reduction in the number of hours and overnight support for PA users (ENIL Citation2015). In addition to the ILF funding cuts, local authorities in England are facing bankruptcy. As a result, they have not increased the funding for direct payments to offset inflation for 12 years; consequently, personal assistants have not received a pay increase (Graby and Homayoun Citation2019).

Variations exist in the amount a government spends on social services, and political ideologies were highlighted as the reasons for these variations. For example, Sweden is considered a social democratic state and spent seven times more on social services than the UK a liberal regime (Tschanz Citation2018). Political ideologies can also influence the availability of direct payments for citizens, as exemplified in the UK where the labour-led local authorities were hesitant to develop direct payments, whilst the conservative local authorities were strong supporters (Leece Citation2007). Overall, direct payments are available in 10 of the 40 countries surveyed, in seven countries they are available on a limited basis, they do not exist in 14 countries, and there was no reference to direct payments in nine countries (see ).

Another consideration in the literature is the need for governments to provide financial resources to support de-institutionalisation and community services, this was implied in all reports and was most prominent in 14 country reports (Leyseele Citation2019; Kukova Citation2019; Mavrou and Liasidou Citation2019; Gyulavári, Gazsi, and Matolcsi Citation2019; Griffo and Tarantino Citation2019; Podzina Citation2019; Ruškus and Gudavičius Citation2019; Koprivica Citation2019; Totoliciu and Johari Citation2019; Beker Citation2019; Ondrušová, Repková, and Kešelová Citation2019; Zaviršek Citation2019; Angel Verdugo and Jenaro Citation2019; Crowther Citation2019). Positive redirection of funding to community services in Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Greece, and Latvia was supported by EU funds (Kukova Citation2019; Žiljak Citation2019; Pall and Leppik Citation2019; Strati Citation2019; Podzina Citation2019).

Insufficient funding for PA schemes results in inadequate and poor quality PA schemes. In some cases, support is reduced to personal care only and at times, not even enough support for essential care (Leyseele Citation2019; Mladenov Citation2017; Askheim Citation2008). The quality of the service is reduced as service providers must increase the efficiencies of their organisations to reduce costs (Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016). Additionally, when applicants are no longer eligible for supports they must rely on informal care, other limited health and social care services or transition to residential services (Rauch, Olin, and Dunér Citation2018; Askheim Citation2008; Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016; Mladenov Citation2017; ENIL Citation2015). This results in a person being denied their right to live independently and a loss of their agency (Rauch, Olin, and Dunér Citation2018; Graby and Homayoun Citation2019).

The model of service provision

Governments have taken different strategies to design and deliver PA schemes resulting in considerable variation in the models of service provision, ranging from provider-led to user-led models. The review of the literature identified three sub-themes related to the model of service provision.

The first theme is the use of eligibility criteria and needs assessments to control access to a PA scheme, a persons’ eligibility is assessed with the following criteria; age, type of disability, the severity of the disability, and means-tested (see ). The eligibility criteria can vary between regions, and this is a barrier to movement between regions and results in the unequal distribution of PA support (von Granitz et al. Citation2017; Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016; Grossman Citation2018). Needs assessments have been described as government control mechanisms which control the actions of PA users by requiring them to comply with specific requirements in order to access a PA scheme such as attending education or work (Grossman Citation2018; Mladenov Citation2017; Christensen, Guldvik, and Larsson Citation2014). This implicit governing of people is facilitated by a lack of transparency in the needs assessment process, resulting in the disempowerment of a person, and maintenance of the status quo (Mladenov Citation2017). Therefore, it is essential for PA schemes to be transparent and for PA users to have the option to appeal a rejected application (Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016; Mladenov Citation2020). Governments take a resource-led rather than a needs-led approach to needs assessments (Mladenov Citation2017) and place a limit on the amount of hours or budget a person can receive (see ). In Sweden, the needs assessment process has become more tightly controlled by government officials to reduce costs and increase efficiencies (Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016). The implication of needs assessments is that they can increase waiting lists, particularly when the needs assessments are resource-led rather than a needs-led (Leyseele Citation2019; Pall and Leppik Citation2019) and they can induce competition between users which can exclude people with sensory, intellectual, or psycho-social impairments (Mladenov Citation2017).

Table 2. Cost ceilings of PA schemes.

Secondly, governments tend to decentralise control of the PA scheme to local authorities to allow for the flexibility to deliver PA that is suitable for their regions and citizens (Clevnert and Johansson Citation2007; Claypool and O’Malley Citation2008; Leece Citation2007; Stout, Hagglund, and Clark Citation2008; Grossman Citation2018; Brennan et al. Citation2017, Citation2018; Askheim, Bengtsson, and Richter Bjelke Citation2014; Andersen, Hugemark, and Bjelke Citation2014). This flexibility creates variation between regions and prevents people from easily moving between regions. This can disadvantage some disabled people as local authorities have ultimate control over access to the service, and not all local authorities provide PA schemes (Grossman Citation2018; Brennan et al. Citation2017; von Granitz et al. Citation2017; Flieger and Naue Citation2019; Leyseele Citation2019; Pall and Leppik Citation2019; Griffo and Tarantino Citation2019). Therefore, in the UK there are calls for a new independent living service that would be a ‘nationally funded body’ independent from the local authorities, with the aim of disabled people controlling the assessment process and administration of support services. This national body would work in tangent with local disabled people’s organisation (Graby and Homayoun Citation2019).

Finally, the literature focused on how governments provide PA users with a choice of service providers. It can be seen in the ENIL (Citation2015) surveys that, a choice of service providers exist in 10 countries, there was no choice given to PA users in three countries, and there was no data on this topic within the remaining reports (see ). A choice of service providers is often dependent upon individual local authorities (Griffo and Tarantino Citation2019; Tveit Sandvin and Bliksvaer Citation2019). In Switzerland and Bulgaria, it is conditional on the PA user acting as an employer (ENIL Citation2015). Another finding from the literature is that service providers tend to market their services in different ways to attract different types of PA users (Andersen, Hugemark, and Bjelke Citation2014). This is an interesting observation from the literature as can be seen in Norway and Sweden that people do move when they have the option. The current trend in these countries is to move from local authority service providers towards, private companies and co-ops (Westberg Citation2010; Askheim Citation2008; Askheim et al. Citation2013). Overall in order for a PA scheme to facilitate choice and control, it must be user-led and grounded in the social model of disability. This means that, the user has a right to the support, they have choice over their personal assistant and the times they work, the schemes facilitates movement between regions and the needs assessment and the appeals procedure is transparent (Mladenov Citation2020).

Governance and regulation

The governance and regulation of services is central to government management of public services. The grey literature shows that some governments use regulators to inspect and license public and private service providers (Andersen, Hugemark, and Bjelke Citation2014; ENIL Citation2015; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Citation2008; Westberg Citation2010). Co-ops also require regulation, as is the case in France, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden (ENIL Citation2015). In Sweden and America, regulation of service providers is centralised and undertaken by national bodies, the Health and Social Care Inspectorate (IVO) and the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) respectfully (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Citation2008; Brennan et al. Citation2016). In Norway and Austria, regulation is decentralised, and local authorities regulate the service providers (Westberg Citation2010; Flieger and Naue Citation2019; Andersen, Hugemark, and Bjelke Citation2014). In Austria and Bulgaria, the Ombudsman acts as a regulator, whereas in Belgium, the service providers are regulated by an external regulator, the Flemish Agency for Persons with Disabilities (VAPH) (Leyseele Citation2019; Kukova Citation2019; Flieger and Naue Citation2019). As can be seen, there are various ways to regulate a service provider, and there are diverse requirements for a license or permit (Ruzicic Novkovic Citation2013; Andersen, Hugemark, and Bjelke Citation2014; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Citation2008). A list of other governance and regulatory mechanisms was drawn from the grey literature; independent inspectors, government inspectors, accreditation from a regulatory body, quality management systems, regulations, standards, guidelines, a quality committee within the organisation, complaint mechanisms, and a complaints procedure to the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Academic Network of Disability Experts 2019).

Managing the quality of the service was another focus of the literature. In Sweden, quality management courses are provided, and all staff have a duty to monitor the quality of the service and report any severe failings that may affect PA users (Westberg Citation2010). Quality is assured in co-op’s as users are supervising their service, and because the users are members of the co-op, they have direct influence over the decisions made (Westberg Citation2010). The CMS in America requires that all states have a quality management strategy, a quality assurance and a quality improvement plan. The plans must include system performance measures, outcome measures and PA user satisfaction measures (Claypool and O’Malley Citation2008; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Citation2008). The National Quality Forum highlighted many challenges when measuring the quality of community services such as PA. They included; the lack of standardised measures, the lack of, or limited access to timely data, the added administrative burden of data collection, the tension between standardised measures for unique and individual services, the lack of a systematic approach to the collection of data (National Quality Forum Citation2016). The literature detailed how organisations themselves measure satisfaction with the services (Westberg Citation2010; Claypool and O’Malley Citation2008). Fundamentally, the quality of the services can only be determined by the PA user (Westberg Citation2010). Therefore user-led services were perceived to be able to offer the highest form of satisfaction and quality monitoring because if the user is unsatisfied, they have the autonomy to change the provider (Westberg Citation2010).

Government management of PA during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic

The literature was searched in July 2020 to explore how governments managed PA schemes during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the severe lockdown period of the pandemic where people were asked to stay at home and only leave for essential reasons, PA users support was either reduced or cancelled by the government or service providers (Elder-Woodward Citation2020). In Glasgow, Scotland, 1883 people lost their service, in Spain and Belgium the service was cancelled in some regions (Alice Citation2020; Elder-Woodward Citation2020; ENIL Citation2020b). Another reason for a reduction in support was that either personal assistants became sick or needed to quarantine. There were also reports of personal assistants not being able to travel to a PA users house as they were unable to travel during this lockdown period as they were not designated as a key worker, and therefore their work was not deemed essential travel (ENIL Citation2020c). The implication of this is that PA users faced significant mental and physical challenges (Elder-Woodward Citation2020) and they became more dependent on family members (Alice Citation2020; Parrock Citation2020; Elder-Woodward Citation2020) particularly as personal assistants are irreplaceable at short notice (Ossie Citation2020).

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for personal assistants was another topic in the literature. As personal assistants were not designated as key workers they were not entitled to PPE. In some cases, the disabled person needed to source the PPE for their staff (Parrock Citation2020; Ossie Citation2020; ENIL Citation2020c). This was evident in Spain where there was no specific reference to PA in the governments’ communications, and as a result, there was no PPE made available for either disabled people or their assistants, resulting in disabled people acquiring their own and for their assistants (ENIL Citation2020b).

The pandemic increased the financial challenges faced by service providers who were already in a weak financial position due to previous funding cuts (ENIL Citation2020a). Financial support was put forward at the European level, from the European Social Fund and the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived, to support disabled people during the pandemic (Parrock Citation2020). In the UK, a positive was noted as direct payment recipients were given more freedom to spend their direct payment ‘more creatively’ (Ossie Citation2020).

The literature also made recommendations for governments on the management of PA schemes during the pandemic. The recommendations suggested that personal assistants should be treated the same as other health care professionals, given adequate PPE, designated as ‘key workers’, provided with hygiene supplies and regularly tested to minimise the spread of the virus. Additionally, a disabled person should have adequate information and access to their personal assistant even if they are in quarantine. Fundamentally the PA service should be protected during the pandemic (European Disability Forum Citation2020; CERMI Citation2020).

Discussion and recommendations for policy, practice, and research

This section will discuss the findings of this scoping review with particular emphasis on implications and recommendations for policy, practice, and research for each of the themes identified.

Legislation

The majority of the countries included in the literature reviewed did not have the appropriate legislation required; this finding is supported by the CRPD comment no. 5 finding that acknowledged that there is an ‘Inadequacy of legal frameworks’ (United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Citation2017, 3). Moreover, the examples presented in the literature illustrated how legislation alone is not enough to ensure full participation for people. This was evident in Sweden, where the law regulating Support and Service to Persons with Certain Functional Disabilities (LSS Act) has been weakened due to changes in the eligibility criteria and court rulings. The Act now supports activities of a caring nature rather than fulfilling the policy intention of full participation in the community (von Granitz et al. Citation2017). Two recommendations were presented in the literature to prevent any weakening of PA legislation. Firstly, changes are needed to local level mindsets and delivery systems to prevent misinterpretation of the intent of the legislation (Brennan et al. Citation2018; Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016). Secondly, as the courts have an essential role to play in how the law is enacted in practice, any vagueness in the law leaves it open to different interpretations by different courts (Gynnerstedt and Bengtsson Citation2016).

Political decision-makers will have to work with disabled people’s organisations to carefully design the legislation to protect against reinterpretations during court rulings and changes to eligibility criteria (Mladenov Citation2017; Rauch, Olin, and Dunér Citation2018; ENIL Citation2015; Mladenov Citation2009). Moreover, the UNCRPD Article 4(3) calls for a co-production process to capture the lived experience of people when creating legislation (Löve et al. Citation2017). Therefore, governments must co-design legislation with accurate wording to ensure that the purpose of the PA schemes, as a tool to facilitate independent living, does not become misinterpreted in the courts or at the local level. Further research is required to carefully design a co-design process that ensures that the voice of disabled people is central to the legislation making process.

Government funding

In addition to the inadequacy of legal frameworks highlighted in the previous section, the CRPD also recognised the ‘Inadequacy of…budget allocations’ (United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Citation2017, 3). The literature reviewed in this paper has discussed how both the neo-liberal strategies and medical model thinking have limited the level of funding going to PA schemes which correlates with previous research (Katzman, Kinsella, and Polzer Citation2020; Mladenov Citation2015). Medical model thinking is negatively impacting funding for PA schemes as this mindset influences governments to fund institutional care. The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) recommends governments to embrace social model thinking and redirect funding from institutional care to community services (Hashemi et al. Citation2008). However, from experiences in Sweden, the costs increased beyond expectation as people who did not previously use either residential or nursing home services began to use PA (Brennan et al. Citation2016). Therefore, a change in mindset from medical to social model thinking, from institutional services to community service may not be adequate to provide enough funding. In order for governments to spend more on social services, it requires a change in political ideology, for example, from a liberal regime to social democratic as is seen in the UK and Sweden, respectively. This means that there would need to be a significant reform in tax policy to support these services (Mendelsohn, Myhill, and Morris Citation2012).

Overall without sufficient funding, direct payments will not make the desired positive change (Slasberg and Beresford Citation2016b; Lakhani, McDonald, and Zeeman Citation2018). Direct payments can increase satisfaction, but, they cannot facilitate independent living if the service is underfunded (Slasberg and Beresford Citation2016b; Spall, McDonald, and Zetlin Citation2005). Essentially unless the schemes are appropriately funded, they will not have the capabilities to support someone to live independently.

The model of service provision

The way a PA scheme is designed and delivered has a considerable impact on the capabilities of PA users to surmount the disabling environmental, economic, and societal barriers they face every day. As such the UNCRPD mandates’ self-management of service delivery’ but it does not stipulate the exact specifications that governments must follow when managing a PA scheme (United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Citation2017, 5). In recognising the need for flexible service delivery, governments decentralise control to local authorities, who have the flexibility to deliver a spectrum of models. However, this creates variation between regions and therefore presents barriers to people who want to move between local authorities (Grossman Citation2018). The literature in this review has referred to the need for further research to explore the use of guidelines to assist local authorities to implement national guidelines and legislation in a manner that facilitates mobilisation (von Granitz et al. Citation2017).

Additionally, the way governments control access to the schemes needs to be evaluated (Slasberg and Beresford Citation2016a; Symonds et al. Citation2018). It has been recommended that governments must simplify the procedure to assess needs (Mladenov Citation2017) and to ensure that an appeals process is in place (Mladenov Citation2020). Moreover, others have argued that the needs assessment should be removed as they are not aligned to the independent living philosophy (Slasberg and Beresford Citation2017) and governments are using them in a resource-led rather than a needs-led approach (Mladenov Citation2017).

Finally, as the relationship between PA user and the personal assistant has a significant impact on a person’s satisfaction and participation (Gibson et al. Citation2009; Katzman, Kinsella, and Polzer Citation2020). PA users must select their personal assistant, as it can have a positive influence on their satisfaction (Mladenov Citation2020). Therefore, this article recommends further research to explore the idea of using profiles to match a PA user to a compatible personal assistant (Andersen, Hugemark, and Bjelke Citation2014; Guldvik Citation2003).

Governance and regulation

During the review of the literature, it was noticeable that the prominent strategy by governments to govern the quality of PA and ensure accountability of funding was to use regulation and licensing. This is unsurprising as it is the standard approach taken across social services (Goodship et al. Citation2004). The majority of the literature within this theme originates from America and Sweden, perhaps indicating that these governments are ahead of others regarding the regulation of PA schemes.

However, notably, the literature review did not identify any government mechanisms for monitoring the quality of a PA service. There are two possible explanations for this; firstly, PA users are not advocating for quality monitoring as they believe that the quality of the service is best monitored by the PA users themselves, particularly if their service provider is a co-op (Westberg Citation2010). Secondly, there is a general lack of research on quality monitoring of social services in the broader context (Melão, Maria Guia, and Amorim Citation2017). Research that does exist is predominately related to services for older persons or intellectually disabled persons (Kelsall, Regi Alexander, and Devapriam Citation2015; Kajonius and Kazemi Citation2016). Therefore, further research is required to co-design quality monitoring mechanisms for PA schemes that align with the social model of disability.

Also absent in the literature reviewed was evidence of government strategies to develop and implement quality improvement policies for PA schemes. In particular, there was no evidence of governments routinely capturing the voice of the PA user to direct the quality improvement of the scheme. Fundamentally, the lived experiences of PA users must guide the management of PA schemes. Therefore, this paper calls for further research to develop strategies to capture the perspective of PA users in a way that can support the development of quality improvement policies.

Government management of PA during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic

At the time of writing the paper, COVID-19 pandemic precautionary measures are six months in place and continuing. It is therefore too early to understand the full implications of the pandemic and its resulting impact on policy and practice. So far the crisis did shine a light on the fragilities of many PA schemes. Many people experienced reduced or cancelled services, as the crisis further compounded the financial strain placed on PA users and service providers from previous austerity measures which left many people vulnerable. In addition, the lack of recognition for the importance of PA left workers without the title ‘key worker’ which hinder their ability to work and to source adequate PPE. Governments must appreciate how valuable PA schemes are and in particular, just how dependent people are on such schemes. An example of a persons’ dependency was shared by one man who shared his experience of life during the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic. He explained that in order to remain continent, when his personal assistant was absent, he would sit in his wheelchair, ‘naked from the waist downwards, whilst sitting on my testicles, for most of the day since lockdown’ (Elder-Woodward Citation2020). Experiences such as this are frightening and highlight the importance of PA and why governments need to build resilient and flexible PA schemes (Ossie Citation2020). Further research will need to be carried out at a later date to capture the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic fully and to evaluate how governments managed PA schemes during this time of crisis.

Limitations

The review explored a significant body of both academic and grey literature to capture how governments are managing PA schemes. However, the quality of this review was affected by inconsistencies in the included grey literature, the ANED country reports and the ENIL PA surveys. These inconsistencies are due to a context-specific understanding of PA and definitions. A limitation to the review was the language restriction as only English language literature was included. Articles in other languages could have been informative to this review. Due to resource constraints, the review was unable to review the complete set of country reports from the CRPD.

Conclusion

Governments have struggled to balance governance and cost-cutting policies while protecting human rights. Even with the adoption of the UNCRPD, this paper demonstrates that governments have tilted towards the cost-cutting agenda rather than a human rights approach. This review did not find any literature evidence of a country that is currently providing a user-led model of PA that is compliant with Article 19 of the UNCRPD. Governments have obligations under the UNCRPD to safeguard social inclusion for all, this necessitates a user-led PA scheme that is well-funded, and governments are failing to do this. Policymakers would learn from this review as it has compiled the challenges that governments face, and this paper has made recommendations for future research. A significant challenge is that due to resource constraints, governments are either limiting access to the service or providing the service for basic care only. These policies are in opposition to Article 19 of the UNCRPD. Governments can implement policies that could be cost-neutral and would bring them closer to compliance with Article 19, such as; direct payments, facilitating a person to schedule their service, removing any restrictions on personal assistant tasks, developing policies based on the social model, reducing the bureaucracy placed on the PA user, and developing a transparent needs assessment process. Legislation should be co-designed to ensure accurate wording to avoid misinterpretation at a local level. This is important as the decisions that policymakers make today will have a significant impact on the achievement of an inclusive society for all. If the lived experience of PA users does not guide governments, they will stay focused on short term cost-cutting, which will inevitably continue to be a barrier to full participation for its citizens.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Funding

References

- Academic Network of Disability Experts. 2019. The Disability Online Tool of the Commission: Quality of Social Services. https://www.disability-europe.net/dotcom.

- Alice. 2020. “Lockdown.” European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Lockdown.pdf.

- Andersen, J., A. Hugemark , and B. R. Bjelke. 2014. “The Market of Personal Assistance in Scandinavia: Hybridization and Provider Efforts to Achieve Legitimacy and Customers.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 16 (sup1): 34–47. doi:10.1080/15017419.2014.880368.

- Angel Verdugo, M., and C. Jenaro. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Spain: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=spain.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Arroyo Méndez, J. 2015. Spain ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/17.-PA-table_Spain.pdf

- Askheim, O. P. 2005. “Personal Assistance – Direct Payments or Alternative Public Service. Does It Matter for the Promotion of User Control?” Disability and Society 20 (3): 247–260. doi:10.1080/09687590500060562.

- Askheim, O. P. 2008. “Personal Assistance in Sweden and Norway: From Difference to Convergence?” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 10 (3): 179–190. doi:10.1080/15017410802145300.

- Askheim, O. P., J. Andersen, I. Guldvik, and V. Johansen. 2013. “Personal Assistance: What Happens to the Arrangement When the Number of Users Increases and New User Groups Are Included?” Disability & Society 28 (3): 353–366. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.710013.

- Askheim, O. P., H. Bengtsson, and B. Richter Bjelke. 2014. “Personal Assistance in a Scandinavian Context: Similarities, Differences and Developmental Traits.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 16 (sup1): 3–18. doi:10.1080/15017419.2014.895413.

- Barnes, C. 2007. “Disability Activism and the Price of Success: A British Experience.” Intersticios: Revista sociológica de pensamiento crítico 1 (2): 15–29.

- Beker, K. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Serbia: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=serbia.

- Bengtsson, S. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Denmark: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=denmark.

- Bezzina, L. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community (Malta): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=malta

- Bolling, J. 2013. Germany ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/PA-GERMANY.pdf

- Bott, S., and D. Jolly. 2015. United Kingdom ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/20.-PA-table_UK.pdf

- Bozec, S. 2015. France ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/7.-PA-table_France.pdf

- Brandvik, T. L. 2015. Norway ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/14.-PA-table_Norway.pdf

- Bronitskaya, E. 2015. Belarus ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/1.-PA-table_Belarus.pdf

- Brennan, C., J. Rice, R. Traustadóttir, and P. Anderberg. 2017. “How Can States Ensure Access to Personal Assistance When Service Delivery is Decentralized? A Multi-Level Analysis of Iceland, Norway and Sweden.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 19 (4): 334–346. doi:10.1080/15017419.2016.1261737.

- Brennan, C., R. Traustadóttir, P. Anderberg, and J. Rice. 2016. “Are Cutbacks to Personal Assistance Violating Sweden’s Obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities?” Laws 5 (2): 23. doi:10.3390/laws50200.

- Brennan, C., R. Traustadóttir, J. Rice, and P. Anderberg. 2018. “Being Number One is the Biggest Obstacle.” Nordisk Välfärdsforskning 3 (01): 18–32. doi:10.18261/issn.2464-4161-2018-01-03.

- Campos Pinto, P., and Y. Kuznetsova. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community (Portugal): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=portugal

- Caunītis, G. 2015. Latvia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/11.-PA-table_Latvia.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2008. Medicaid Program; Self-Directed Personal Assistance Services Program State Plan Option (Cash and Counseling). Final Rule. United States: Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration.

- CERMI. 2020. “People with Disabilities and their Families and the Coronavirus Health Crisis: Compendium of Recommendations for the Short-Term Management of the Pandemic.” European Disabilty Forum. Accessed 20 July 2020. www.edf-feph.org/cermi-people-disabilities-and-their-families-and-coronavirus-health-crisis-compendium.

- Christensen, K., I. Guldvik, and M. Larsson. 2014. “Active Social Citizenship: The Case of Disabled Peoples’ Rights to Personal Assistance.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 16 (sup1): 19–33. doi:10.1080/15017419.2013.820665.

- Claypool, H., and M. O’Malley. 2008. Consumer Direction of Personal Assistance Services in Medicaid – A Review of Four State Programs. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/7756.pdf.

- Clevnert, U., and L. Johansson. 2007. “Personal Assistance in Sweden.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 19 (3): 65–80. doi:10.1300/J031v19n03_05.

- Corinne, L. 2015. Belgium/Wallonia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2.-PA-table_Belgium-Wallonia.pdf

- Crowther, N. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. United Kingdom: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=united-kingdom.

- Dahl, M., and J. Bolling. 2015. Sweden ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/18.-PA-table_Sweden.pdf

- Dejong, G. 1979. “Independent Living: From Social Movement to Analytic Paradigm.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 60: 435–446.

- Dejong, G., and R. Lifchez. 1983. “Physical Disability and Public Policy.” Scientific American 248 (6): 40–49. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0683-40.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. n.d. 10th Anniversary of the Adoption of Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/the-10th-anniversary-of-the-adoption-of-convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd-crpd-10.html.

- Duračinská, M. 2013. Slovakia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/PA-SLOVAKIA.pdf

- Elder-Woodward, J. 2020. Personal Experiences of Managing an Option 1 Support Package. Accessed 20 July 2020. https://www.iriss.org.uk/news/features/2020/07/08/personal-experiences-managing-option-1-support-package.

- ENIL. 2013. Personal Assistance Services in Europe. Dublin, Ireland: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/European-Survey-on-Personal-Assistance-Final.pdf.

- ENIL. 2015. Personal Assistance Services in Europe 2015. Brussels: European Network on Independent Living. https://www.enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Personal-Assistance-Service-in-Europe-Report-2015.pdf.

- ENIL. 2020a. COVID-19 Pandemic and Independent Living in Scotland. https://enil.eu/news/covid-19-pandemic-and-independent-living-in-scotland/.

- ENIL. 2020b. “Living Independently during COVID-19 Pandemic – Spain.” European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/news/living-independently-during-covid-19-pandemic-spain/.

- ENIL. 2020c. “Persons with Disabilities Stripped of Support and Protective Equipment during COVID 19 Crisis.” European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/news/persons-with-disabilities-stripped-of-support-and-protective-equipment-during-covid-19-crisis/.

- European Disability Forum. 2020. “Open Letter to Leaders at the EU and in EU Countries: COVID-19 – Disability Inclusive Response." European Disability Forum. edf-feph.org/newsroom/news/open-letter-leaders-eu-and-eu-countries-covid-19-disability-inclusive-response.

- Flieger, P., and U. Naue. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Austria: The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=austria.

- Gibson, B. E., D. Brooks, D. DeMatteo, and A. King. 2009. “Consumer-Directed Personal Assistance and ‘Care’: Perspectives of Workers and Ventilator Users.” Disability & Society 24 (3): 317–330. doi:10.1080/09687590902789487.

- Goodship, J., K. Jacks, M. Gummerson, J. Lathlean, and S. Cope. 2004. “Modernising Regulation or Regulating Modernisation? The Public, Private and Voluntary Interface in Adult Social Care.” Public Policy and Administration 19 (2): 13–27. doi:10.1177/095207670401900204.

- Graby, S., and R. Homayoun. 2019. “The Crisis of Local Authority Funding and Its Implications for Independent Living for Disabled People in the United Kingdom.” Disability & Society 34 (2): 320–325. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1547297.

- Griffo, G., and C. Tarantino. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Italy: The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=italy.

- Grossman, B. R. 2018. “Disability and Corporeal (Im)Mobility: How Interstate Variation in Medicaid Impacts the Cross-State Plans and Pursuits of Personal Care Attendant Service Users.” Disability and Rehabilitation 41 (25): 3079–3089. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1483436.

- Guldvik, I. 2003. “Personal Assistants: Ideals of Social Care-Work and Consequences for the Norwegian Personal Assistance Scheme.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 5 (2): 122–139. doi:10.1080/15017410309512618.

- Gynnerstedt, K., and H. Bengtsson. 2016. “Personal Assistance in Sweden: Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments.” Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work 23 (1–2): 18–28. doi:10.11157/anzswj-vol23iss1-2id166.

- Gyulavári, T., A. Gazsi, and R. Matolcsi. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Hungary: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=hungary.

- Haraldsdóttir, F. 2013. Iceland ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/PA-ICELAND-12-03-13.pdf

- Hashemi, L., A. D. Henry, M. L. Ellison, S. M. Banks, R. E. Glazier, and J. Himmelstein. 2008. “The Relationship of Personal Assistance Service Utilization to Other Medicaid Payments Among Working-Age Adults with Disabilities.” Home Health Care Services Quarterly 27 (4): 280–298. doi:10.1080/01621420802581451.

- Hornich, P. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. (Liechtenstein): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=liechtenstein

- Jeseničnik, N. 2015. Slovenia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/16.-PA-table_Slovenia.pdf

- Katsigianni, A. 2015. Greece ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/9.-PA-table_Greece-Aglaia.pdf

- Katsui, H., K. Valkama, and T. Kröger. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community (Finland): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=finland

- Kajonius, P. J., and A. Kazemi. 2016. “Structure and Process Quality as Predictors of Satisfaction with Elderly Care.” Health & Social Care in the Community 24 (6): 699–707. doi:10.1111/hsc.12230.

- Katzman, E. R., E. A. Kinsella, and J. Polzer. 2020. “Everything is Down to the Minute’: Clock Time, Crip Time and the Relational Work of Self-Managing Attendant Services.” Disability & Society 35 (4): 517–525. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1649126.

- Kelsall, A., D. Regi Alexander, and J. Devapriam. 2015. “Regulation of Intellectual Disability Services.” Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities 9 (3): 101–107. doi:10.1108/AMHID-01-2015-0005.

- King, R., B. Hooper, and W. Wood. 2011. “Using Bibliographic Software to Appraise and Code Data in Educational Systematic Review Research.” Medical Teacher 33 (9): 719–723. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.558138.

- Koprivica, N. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Montenegro: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=montenegro.

- Król, A. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community (Poland): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=poland

- Kukova, S. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Bulgaria: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=bulgaria.

- Langvad, S. 2015. Denmark ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living.” https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/5.-PA-table_Denmark.pdf

- Lakhani, A., D. McDonald, and H. Zeeman. 2018. “Perspectives of Self-Direction: A Systematic Review of Key Areas Contributing to Service Users’ Engagement and Choice-Making in Self-Directed Disability Services and Supports.” Health & Social Care in the Community 26 (3): 295–313. doi:10.1111/hsc.12386.

- Leece, J. 2007. “Direct Payments and User-Controlled Support: The Challenges for Social Care Commissioning.” Practice 19 (3): 185–198. doi:10.1080/09503150701574283.

- Leyseele, E. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Belgium: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=belgium.

- Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K. K. O’Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science: IS 5 (1): 69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Limbach-Reich, A. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. (Luxembourg): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=luxembourg

- Löve, L., R. Traustadóttir, G. Quinn, and J. Rice. 2017. “The Inclusion of the Lived Experience of Disability in Policymaking.” Laws 6 (4): 33. doi:10.3390/laws6040033.

- Mavrou, K., and A. Liasidou. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Cyprus: The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=cyprus.

- Melão, N. F., S. Maria Guia, and M. Amorim. 2017. “Quality Management and Excellence in the Third Sector: Examining European Quality in Social Services (EQUASS) in Non-Profit Social Services.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 28 (7–8): 840–857. doi:10.1080/14783363.2015.1132160.

- Mendelsohn, S., W. N. Myhill, and M. Morris. 2012. “Tax Subsidization of Personal Assistance Services.” Disability and health journal 5 (2): 75–86. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2011.12.003.

- Michaelides, C. 2015. Cyprus ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/4.-PA-table_Cyprus.pdf

- Mladenov, T. 2009. “Institutional Woes of Participation: Bulgarian Disabled People’s Organisations and Policy-Making.” Disability & Society 24 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1080/09687590802535386.

- Mladenov, T. 2015. “Neoliberalism, Postsocialism, Disability.” Disability & Society 30 (3): 445–459. doi:10.1080/09687599.2015.1021758.

- Mladenov, T. 2017. “Governing Through Personal Assistance: A Bulgarian Case.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 19 (2): 91–103. doi:10.1080/15017419.2016.1178168.

- Mladenov, T. 2020. “What is Good Personal Assistance Made of? Results of a European Survey.” Disability & Society 35 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1621740.

- Munn, Z., M. D. J. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing Between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1): 143. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- National Quality Forum. 2016. Quality in Home and Community-Based Services to Support Community Living: Addressing Gaps in Performance Measurement. https://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=83433.

- Naughton, M. 2013. Ireland ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living.” https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/PA-IRELAND_2013.pdf

- Ondrušová, D., K. Repková, and D. Kešelová. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Slovakia: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=slovakia.

- Ossie, S. 2020. “What Should I Do If All my PAs Suddenly Had to Self- Isolate?” In Support for the Care Sector with Covid-19. Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE).

- Panayotova, K. 2015. Bulgaria ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/3.-PA-table_Bulgaria.pdf

- Pall, K., and L. Leppik. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Estonia: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=estonia.

- Parrock, J. 2020. “European Disabled Groups Worry About Threat to Independent Living Amid COVID-19.” Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/14/european-disabled-groups-worry-about-threat-to-independent-living-amid-covid-19.

- Petridisi, S. 2015. Georgia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/8.-PA-table_Georgia.pdf

- Peters, M. D., C. M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. B. Soares. 2015. “Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Peters, M., C. Godfrey, P. McInerney, C. Baldini Soares, H. Khalil, and D. Parker. 2017. Scoping Reviews. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/.

- Podzina, D. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Latvia: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=latvia.

- Rauch, D., E. Olin, and A. Dunér. 2018. “A Refamilialized System? An Analysis of Recent Developments of Personal Assistance in Sweden.” Social Inclusion 6 (2): 56–65. doi:10.17645/si.v6i2.1358.

- Rice, J., and R. Traustadóttir. 2019. Living Independently and being included in the community. (Iceland): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=iceland

- Ruškus, J., and A. Gudavičius. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Lithuania: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=lithuania.

- Ruzicic Novkovic, M. 2013. Serbia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/PA-SERBIA.pdf.

- Slasberg, C., and P. Beresford. 2016a. “The Eligibility Question – The Real Source of Depersonalisation?” Disability & Society 31 (7): 969–973. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1215122.

- Shavreski, Z. 2015. Macedonia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/12.-PA-table_Macedonia.pdf

- Siilsalu, M. 2015. Estonia ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/6.-PA-table_Estonia.pdf

- Šiška, J. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community (Czech): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=czech-republic

- Slasberg, C., and P. Beresford. 2016b. “The False Narrative about Personal Budgets in England: Smoke and Mirrors?” Disability & Society 31 (8): 1132–1137. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1235309.

- Slasberg, C., and P. Beresford. 2017. “The Need to Bring an End to the Era of Eligibility Policies for a Person-Centred, Financially Sustainable Future.” Disability & Society 32 (8): 1263–1268. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1332560.

- Smits, J. 2015. Netherlands ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/13.-PA-table_Netherlands-Holland.pdf

- Spall, P., C. McDonald, and D. Zetlin. 2005. “Fixing the System? The Experience of Service Users of the Quasi-Market in Disability Services in Australia.” Health & Social Care in the Community 13 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00529.x.

- Stout, B. J., K. J. Hagglund, and M. J. Clark. 2008. “The Challenge of Financing and Delivering Personal Assistant Services.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 19 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1177/1044207308315281.

- Strati, E. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Greece: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=greece.

- Symonds, J., V. Williams, C. Miles, M. Steel, and S. Porter. 2018. “The Social Care Practitioner as Assessor: ‘People, Relationships and Professional Judgement’.” The British Journal of Social Work 48 (7): 1910–1928. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx154.

- Totoliciu, L., and A. Johari. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Romania: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=romania.

- Tomassoni, M. 2015. San-Marino ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living.” https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/15.-PA-table_San-Marino.pdf

- Tricco, A. C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–473. doi:10.7326/M18-0850.

- Tschanz, C. 2018. “Theorising Disability Care (Non-)Personalisation in European Countries: Comparing Personal Assistance Schemes in Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.” Social Inclusion 6 (2): 22–33. doi:10.17645/si.v6i2.1318.

- Tveit Sandvin, J., and T. Bliksvaer. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Norway: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=norway.

- United Nations. 2006. “Convention on the Rights of Perons with Disabilities.” Accessed 09 April 2019. http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2017. General Comment No. 5 – Article 19: Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. CRPD/C/18/1.

- Van Damme, C. 2015. Belgium/Flanders ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2.-PA-table_Belgium-Flanders.pdf

- von Granitz, H., I. Reine, K. Sonnander, and U. Winblad. 2017. “Do Personal Assistance Activities Promote Participation for Persons with Disabilities in Sweden?” Disability and Rehabilitation 39 (24): 2512–2521. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1236405.

- Voudouri, M., and E. Gasparini. 2015. Italy ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/10.-PA-table_Italy.pdf

- Wehrli, P. 2015. Switzerland ENIL Personal Assistance Survey: European Network on Independent Living. https://enil.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/19.-PA-table_Switzerland.pdf

- Westberg, K. 2010. Personal Assistance in Sweden: Independent Living Institute. https://www.independentliving.org/files/Personal_Assistance_in_Sweden_KW_2010.pdf.

- Yalcin, B. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community (Turkey): The Academic Network of European Disability experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=turkey

- Zaviršek, D. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Slovenia: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=slovenia.

- Žiljak, T. 2019. Living Independently and Being Included in the Community. Croatia: The Academic Network of European Disability Experts (ANED). https://www.disability-europe.net/theme/independent-living?country=croatia.