ABSTRACT

For legislators to be held accountable for their stances voters need to sanction unpopular positions. However, because of strong party discipline it is difficult to identify the effects of individual MPs’ stances rather than the stance of their party, because MPs almost always have the same stance as their party. Researchers must therefore study issues which cut across parties or where parties allowed representatives to follow their conscience. Same-sex marriage is one such issue. We use data from the 2017 marriage law survey and subsequent 2019 federal election results to test whether MPs whose referendum positions were out-of-step with their district faced electoral sanction. We find that a standard deviation increase in congruence at the level of the polling place catchment area yields a statistically and substantively insignificant change in vote share of −0.1 percentage points. The results question the degree to which electors control their representatives beyond voting for a party label.

Introduction

One of the most notable results in the 2019 Australian election occurred in the division of Warringah, where former prime minister Tony Abbott lost to independent candidate Zali Stegall. The swing against Abbott (−12.6%) was the sixth largest swing among incumbents; much commentary attributed Abbott’s fall in popularity to his stance on social issues including same-sex marriage. Stegall, by contrast, was ‘a supporter of same-sex marriage who carries a rainbow umbrella when campaigning in the wet’, supported by individuals for whom Abbott’s abstention on the 2017 same-sex marriage vote was a ‘defining moment’ (Packham and Barrett Citation2019). More broadly, Abbott’s ‘opposition to gay marriage and support for coal-fired power put him at odds with economically conservative but socially liberal voters’ (Maley Citation2019).

It is difficult to say how political science might judge media claims that Abbott was punished by voters who disagreed with him on specific issues. There is, both in Australia and comparatively, a literature on the ‘personal vote’ that identifies candidate attributes which are hard to change (gender, incumbency) or which are generally advantageous (greater campaign effort). A related literature on dyadic representation – the association between local opinion and legislators’ actions – does include examinations of whether legislators are punished for being ‘out-of-step’ with their constituents, but this literature is almost entirely US-focused. Given the much more candidate-centred nature of electoral contests in the US compared to most other established democracies, these results may not travel well.

This paper leverages the 2017 Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey to investigate whether MPs in the House of Representatives experience electoral consequences for specific issue stances. The Postal Survey revealed that a majority of voters in a majority (133/150) of Australian divisions supported same-sex marriage. Following the survey, a clear majority (136/150) of MPs voted to legislate accordingly. Although both votes were lop-sided, there is enough variation – particularly within the Liberal and National parties – to assess whether MPs who adopted unpopular positions (either supporting same-sex marriage in areas which opposed it or the reverse) were penalised in the subsequent (2019) federal election.

In the next section, we describe the comparative research upon which this study builds, and provide greater context surrounding the 2019 election. We find no identifiable relationship between voters’ support for same-sex marriage at the individual level, the stance taken by their incumbent MP (measured as whether they voted for, against, or abstained from the legislative same-sex marriage), and their subsequent vote choice at the 2019 federal election. Aggregate-level analysis further shows that incumbents whose vote in the parliament did not agree with the preference of their local area were not punished at the ballot box. There is also no statistically or substantively significant relationship between pre-referendum views and 2016 vote shares, and so there is evidence of negligible selection on views on same-sex marriage. Our results suggest that while voters have little control over their representatives between elections, they also show little willingness to punish them for unpopular issue stances come election time. Methodologically, our results provide a current ‘best practice’ framework for triangulating individual and aggregate-level data to measure the effects of representative congruence on electoral outcomes.

Literature and theory

Three literatures shape our study of legislator accountability in Australia: international research into dyadic representation, more specific research on the electoral accountability that can underpin dyadic representation, and research on candidate effects and the personal vote.

Dyadic representation describes the degree to which legislators’ actions correspond to the policy preferences of their constituents (Hanretty, Lauderdale, and Vivyan Citation2017; Hill and Hurley Citation1999; Miller and Stokes Citation1963). It applies best to single-member district systems, since here there is a one-to-one correspondence between (some summary measure of) district opinion and the actions of a particular legislator (cf. Golder and Stramski Citation2010). Converse and Pierce (Citation1986, 491) calls this the ‘basic bond’: the situation where an electorate holds generally homogeneous preferences that the representative both shares and displays in their legislative behaviour. While much research on dyadic representation models US legislators’ roll-call behaviour as a factor of constituency opinion, non-US research is complicated by (usually) less intra-party variation in how legislators vote.

The earliest literature on dyadic representation predates some classic theoretical accounts of representation (Pitkin Citation1967) and the ‘new wave’ of accounts emerging in the 2000s (Mansbridge Citation2003; Rehfeld Citation2006; Saward Citation2010; Wolkenstein and Wratil Citation2021). Briefly, dyadic representation, insofar as it concerns policy preferences of constituents and legislators, is a type of substantive representation; the degree to which dyadic representation can be secured can depend alternately on sanctioning out-of-step legislators or the selection of faithful ‘gyroscopic’ legislators who, acting by their own lights, secure a higher degree of dyadic representation than bad types. Although sanctioning and selecting both play a role, most normative theorists assign greater weight to selection. The match between empirical studies of representation and normative theories of representation can be approximate, particularly where theories give a central role to politicians’ intrinsic motivation, or where sanctions are anticipated and thus never deployed (Wolkenstein and Wratil Citation2021). The twin mechanisms of sanctioning and selection can operate at different levels (individual candidate or party); our focus here is on that part of dyadic representation which is within parties, with attention paid to both sanctioning and selection.

Many studies have thus focused on ‘conscience issues’, where party leadership allow legislators to vote according to conscience rather than on party lines. For instance, Hanretty, Lauderdale, and Vivyan (Citation2017) demonstrate a within-party relationship between constituency opinion on same-sex marriage and a 2013 vote of conscience on the introduction of same-sex marriage in Great Britain, while Carson, Ratcliff, and Dufresne (Citation2018) similarly find relationships between division-level public opinion on same-sex marriage and votes of conscience on the Marriage Amendments Bill 2012, and between public opinion and subsequent public statements of support for same-sex marriage by 2016. Neither of these formative papers, however, explores possible mechanisms to explain the dyadic relationship.

The most obvious mechanism underpinning dyadic representation is voters’ ability to sanction incumbents who are ‘out-of-step’ with electorate opinion on a given issue. American voters appear more likely to vote for incumbents with whom they agree on crime (Canes-Wrone, Minozzi, and Reveley Citation2011), trade (Jacobson Citation1996), and health-care (Nyhan et al. Citation2012), net of other factors. Similarly, being out-of-step materially damages re-election prospects: voting for Obamacare (which was generally unpopular at the time) cost Congressional incumbents eight percentage points at the next election (Nyhan et al. Citation2012, 859). However, effects appear much smaller in state legislatures: Rogers (Citation2017, 559) finds that a standard deviation increase in congruence improves the vote shares of state legislative incumbents by just 0.7 percentage points.

Outside of America, it remains unclear whether individual legislators are held accountable for their issue stances at all, or whether their re-election prospects are dominated by their party label. Hanretty, Mellon, and English (Citation2021) suggest that the penalties faced by incumbents with unpopular positions are limited. These small effects were found in jurisdictions without compulsory voting, and in which voters, compared to non-voters, are on average more politically engaged. We might expect these small effects to be even smaller in a system where voting is compulsory.

A third stream of research focuses on changes in a candidate’s vote share (from one election to another) attributable to the attributes or actions of that candidate. While individual candidates seem self-evidently important to election outcomes, for most of the post-war period in Australia a ‘personal vote [was] … generally thought to be negligible’ (Bean Citation1990, 253); around 2.5 percentage points at most, if a candidate is particularly well-liked among voters. Subsequent papers have investigated which candidate attributes and actions are most effective, with unclear findings: Studlar and McAllister (Citation1994) and Bowler, Farrell, and McAllister (Citation1996) find additional constituency service might decrease incumbent vote share; by contrast, being an active party member before entering parliament seems to increase vote share, although ‘these party aspects appear to be less important now than they were in the late 1990s and early 2000s’ (McAllister Citation2015, 343, emphasis added). In Australia, individual candidates generally appear to have only marginal control over their vote share, with most attributable to party ‘brands’ (Charnock Citation2007). To the extent that voters can hold their representatives accountable electorally, most extant evidence suggests that the most effective mechanisms operate via party nomination of candidates.

Context

Moving towards same-sex marriage

Before 2004, marriage was not defined in Australian legislation: the Marriage Act of 1961 contained no definition, leaving the matter to the common law. The Marriage Amendment Act 2004 defined marriage as ‘the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life’, expressly to constrain any common law interpretation that might follow international trends towards allowing same-sex marriage. Between 2004 and 2017, ‘23 bills dealing with marriage equality or the recognition of overseas same-sex marriages [were] introduced into the federal Parliament’ (McKeown Citation2018). Before the 2016 election, the Coalition Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull – a public supporter of marriage reform – responded to increasing public pressure by promising a plebiscite on the issue of introducing marriage for same-sex couples. Legislation to enable a plebiscite was rejected by the parliament, with a majority of members preferring to proceed straight to legislative debate. As a compromise, the government directed the Australian Bureau of Statistics to conduct a voluntary postal survey to measure electors’ views for or against changing the law to allow same-sex couples to marry.

The postal ballot

On 12 September 2017, postal ballots began to be mailed to adult electors across Australia. Electors were encouraged to return their responses by 27 October, and responses received after 7 November were not counted. Electors were asked ‘Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?’. Labor and the Greens campaigned for a ‘yes’ vote, the Nationals campaigned for a ‘no’ vote, while the Liberals let members campaign for either side. A total of 79.5% of electors participated in the ballot, of whom 61.6% voted ‘yes’. Electorates which were older, had a higher proportion of married or widowed people, had more Christian, Protestant or Muslim residents, and had a greater proportion of foreign-born residents were more likely to vote ‘no’ (Gravelle and Carson Citation2019). The ‘yes’ vote was significantly higher in affluent areas and areas with a higher proportion of lesbian couples (McAllister and Snagovsky Citation2018, 417). The ‘yes’ vote was also higher in areas where the incumbent MP supported same-sex marriage (compared to MPs with no clear stance), but there was no opposite effect in areas where MPs opposed same-sex marriage (McAllister and Snagovsky Citation2018, 418). There were mixed findings regarding the division-level association between the (Liberal plus National) Coalition vote and the ballot outcome: Wilson, Shalley, and Perales (Citation2020, 8) found a significant negative association which was not found by Gravelle and Carson (Citation2019).

Following the publication of the result of the survey on 15 November 2017, a bill was introduced in the Senate amending the Marriage Act and passed 43 votes to 12. It was subsequently passed by the House. Both major parties allowed their members to vote according to their conscience; Labor was nonetheless unanimously supportive in the House, but divided in the Senate with two Senators voting no and eight abstaining.

The Coalition was divided in both houses, with Tony Abbott and future Prime Minister Scott Morrison among notable abstainers. The Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act 2017 was enacted on 9 December 2017.

In August 2018, Liberal parliamentarians withdrew support for Malcolm Turnbull’s leadership (for a range of ostensible issues, including but not exclusive to the postal survey) and replaced him with Morrison. Morrison led the Coalition to a federal election in May 2019, increasing the government’s majority by one seat following a campaign centred on tax offsets for retirees, housing affordability, health, and the environment (Cameron and McAllister Citation2019, 7).

These three events – the postal survey, the subsequent parliamentary votes, and the subsequent election – comprise a rare test case of individual accountability. First, the postal survey reveals district preferences on a salient issue. Second, conscience votes on the subsequent legislation mean we can test individual accountability, rather than party accountability – something which, given high levels of party discipline, is not normally possible. Third, the election following within 18 months allows us to move beyond establishing some degree of dyadic representation, per Carson, Ratcliff, and Dufresne (Citation2018), and ask whether that representation affects electoral outcomes.

Individual-level analysis

We begin by examining individual level data from the 2019 Australian Election Study (AES) (McAllister et al. Citation2019). We estimate the probability of voting for an incumbent conditional on their position on same-sex marriage, the respondent’s position on same-sex marriage, and the interaction between the two. We restrict this analysis to respondents in divisions held by 59 incumbent members of the House of Representatives who:

were in office at the time of the same-sex marriage vote;

who contested the same division in the 2019 election that they had previously contested in the 2016 election;Footnote1 and

who represent any party in the Liberal-National Coalition.

The final restriction is necessary because only the Coalition parties experienced the intraparty disagreement necessary to identify the effects of MPs’ individual stances. If Labor MPs generally did better in areas that voted for same-sex marriage, it might be that voters rewarded individual Labor MPs for voting for same-sex marriage or that the party generally did better in the kinds of areas which support same-sex marriage. After restricting our analysis in this way, we are left with information from 670 AES respondents who were from a known electoral division, who were represented by one of these incumbents, and who were eligible to vote.

The primary dependent variable in the analysis is whether or not the respondent gave their first preference vote to the Coalition incumbent (whether Liberal or National; y = 1) or gave it to any other party, or spoiled their ballot (y = 0). Just under one-half of respondents (49%) voted for their Coalition incumbent. We additionally model the respondent’s two-party preferred vote (i.e. their top preference after removing preferences for independent or minor party candidates). The proportion of respondents who indicated directing preferences to the Coalition over Labor was 53%. Whether we use the primary or two-party preferred vote does not significantly affect our results, and we present findings from both analyses.

The key independent variables are the incumbent’s position on same-sex marriage, the respondent’s position on same-sex marriage, and the interaction between the two. The interaction term comprises our key measure of congruence, and methodologically we need to include the constituent variables of the interaction term (Brambor, Clark, and Golder Citation2006). We operationalise the incumbent’s stance as a trichotomous variable. MPs who voted for same-sex marriage in the vote of the 15th November 2017 are given a value of one. MPs who voted against same-sex marriage are given a value of minus one. MPs who abstained are given a value of zero. Respondent positions on same-sex marriage are taken from a question asking respondents ‘Do you personally favour or oppose same sex couples being given the same rights to marry as couples consisting of a man and a woman?’. ‘Strongly favour’ or ‘favour’ responses (71% of our sample) are coded as 1; ‘strongly oppose’ or ‘oppose’ responses as −1. The interaction term therefore has a value of one when the respondent and the incumbent both favour SSM (1 * 1 = 1) or when the respondent and the incumbent both oppose SSM (−1 * −1 = 1), and a zero in all other cases.

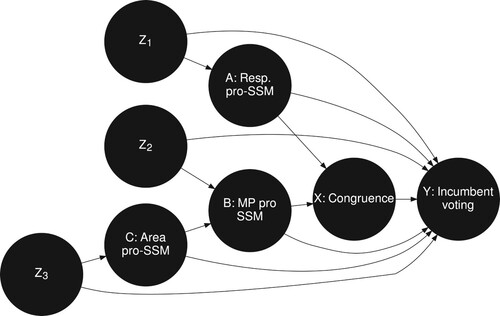

We control for variables with a potential ‘back-door path’ effect on the relationship (Morgan and Winship Citation2015) between congruence and respondent vote choice. We identify three key back-door paths in the directed acyclic graph (DAG) in . ‘Congruence’ is shown as the outcome of two causes: the respondent’s own position on same-sex marriage, and the incumbent’s position on same-sex marriage. To estimate the effect of congruence, we need to control for these antecedents. If we failed to control for these antecedents, we would open up a back-door path (X ← A → Y or X ← B → Y).

Figure 1. Directed acyclic graph of factors affecting incumbent voting. z1 and z2 represent observed and unobserved causes of respondent and incumbent position on same-sex marriage; z3 observed and unobserved causes of area attitudes.

Consider the role of education: individuals with university degrees are much more likely to support same-sex marriage (Abou-Chadi and Finnigan Citation2019; Armenia and Troia Citation2017; Clements Citation2014; Perales, Bouma, and Campbell Citation2019), and are also less likely to vote for Coalition candidates (Cameron and McAllister Citation2019, 19). Since education probably also affects legislators’ views on same-sex marriage, and since better-educated legislators might win more votes, we also add education to the variables included in z2 (full list below).

A final back-door path operates through area characteristics. If a legislator decides to support same-sex marriage upon learning that most of her constituents support it, the causal arrow runs from ‘C: Area pro-SSM’ to ‘B: Pro-SSM MP’. Further, antecedents of area-level support might have an effect both on the area and on the incumbents’ prospects, separate from individual characteristics. This is central to the concept of ‘neighbourhood effects’: that living among a particular community might affect your personal preferences. Charnock (Citation1996, 59) citing (Aitkin Citation1988) nominates ‘country-mindedness’ – which might be operationalised at the aggregate level by the percentage employed in primary industries – as one example where geographic proximity to a community potentially affects the votes of those not directly engaged in that work. For these reasons, we include in z3 variables which past research has shown to affect aggregate-level support for same-sex marriage and the Coalition vote.

Under z1 (respondent characteristics) we include:

the respondent’s highest level of educational qualifications (degree level or below-degree level) (Cameron and McAllister Citation2019, 19; Perales, Bouma, and Campbell Citation2019).

the respondent’s gender. This variable is included because men more commonly disapprove of homosexuality (and by implication, more likely to disapprove of SSM) (Van den Akker, Van der Ploeg, and Scheepers Citation2013), and because men are much more likely to vote for Coalition candidates (Cameron and McAllister Citation2019, 17).

the respondent’s age, and the square of age: older voters are more likely to disapprove of same-sex marriage (Armenia and Troia Citation2017) 192 and to vote for Coalition candidates (Cameron and McAllister Citation2019, 18)

the respondent’s religion, recoded into three ordinal values: ‘support’ if the respondent either stated no religion, or stated a religion which was officially supportive of SSM; ‘mixed’ if the respondent stated a religion which had an ambivalent position on SSM, or ‘oppose’ if the respondent stated a religion opposed to SSM.Footnote2 More religious individuals were generally more likely to oppose SSM, though the effects varied according to religious affiliation (Perales, Bouma, and Campbell Citation2019). More religious individuals have also been more likely to vote for Coalition candidates in recent elections (Donovan Citation2014).

Under z2 (MP characteristics) we include:

MP age, which may structure their views on same-sex marriage in the same way that respondents’ ages do, and because voters may have preferences regarding candidate age (Sevi Citation2021);

MP tenure, and specifically whether the MP was elected in 2016 or before. MPs in their first re-election attempt often enjoy an incumbency bonus not enjoyed by longer-serving incumbents (Gelman and King Citation1990; Horiuchi and Leigh Citation2009; Mackerras Citation2012).

MP gender, which may structure MP views on SSM in the same way that respondent gender does, and because of the advantage enjoyed by female candidates in Australian elections (Schwarz and Coppock Citation2020; Schwindt-Bayer, Malecki, and Crisp Citation2010).

MP party.

MP level of education, both because MP education can structure MP views on SSM, and because voters may prefer candidates with higher qualifications.

Finally, under z3 (area characteristics), we include the union of the controls included in three papers on the same-sex marriage vote (Gravelle and Carson Citation2019; McAllister and Snagovsky Citation2018; Wilson, Shalley, and Perales Citation2020) and past work looking at the aggregate correlates of the Coalition vote (Robinson Citation2015). These controls are:

the percentage of the workforce engaged in agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and public administration;

the percentage of the population which belongs to a religion which opposed SSM, which supported SSM or is not religious;

the percentage of the population with a university degree;

median total personal income in dollars per week;

the area-level support for same-sex marriage, minus 50 percentage points, such that positive values indicate support and negative values opposition; and

the incumbent’s vote share in the previous (2016) election.

All of these area-level controls are measured at the Census SA2 level, with the exception of lagged vote share, which is measured at the level of the electoral division. Including area-level support for SSM is vital to avoid confusing contextual effects (‘living in a pro-SSM area’) with individual effects (‘being pro-SSM and in step with one’s representative’). We do not include controls, such as the number of candidates in the division, which arise after the SSM legislative vote because of potential post-treatment effects: incumbents who are in-step with their area might scare-off potential challengers, for instance. Alternately, incumbents who are publicly out-of-step might attract challengers, as possibly occurred in Warringah.

Summary statistics for all of the controls we use in our regression are given in Supplementary Information Table S1. A small number of missing values were filled using multiple imputation via the Amelia package (Honaker, King, and Blackwell Citation2011). We multiply impute five data-sets; the results of the regression models shown below are the result of combining the results of models estimated on each imputed data-set using Rubin’s rules (Meng and Rubin Citation1992).

Model specification

We estimate a Bayesian hierarchical logistic regression with weakly informative priors. Respondents are nested within electoral divisions, and so their observed votes reflect unobserved division-level characteristics. The Bayesian model allows us to talk directly about the probability that the effects of congruence are positive (or negative), rather than talking about the probability that the effects of congruence are exactly zero (i.e. the null hypothesis). We include a detailed description of our prior specification in the Appendix for researchers familiar with Bayesian statistics.

We estimate our models using the brms package (Bürkner Citation2017) for R. We run three separate Monte Carlo chains for 2000 iterations, discarding the first 1000 iterations as warmups. Model convergence was successful, per the R2 statistic. We estimate the models with and without controls for first-preference votes and two-party preferred votes. Although the results from models without controls cannot be interpreted as causal estimates, we report them to show that the effect sizes of congruence are similar whether or not one includes controls, and that therefore it is unlikely that our covariates have ‘artificially’ reduced a real effect. We report only the main effects in the table; full regression tables can be found in Supplementary Information Table S2.

The first row of coefficients shows that respondent support for SSM is negatively associated with voting for Coalition incumbents across all specifications, but only distinct from zero in models which lack controls (columns (1) and (3)). The effects of incumbent support for SSM are inconsistent and not distinct from zero. Finally, the effects of congruence are not distinct from zero, and change sign between models with and without controls ().

To calculate the substantive magnitude of changes in congruence, we simulate the effect of a two unit increase in congruence: this would occur if either the respondent (or incumbent) switched from opposing to supporting SSM in order to match the incumbent (or respondent).Footnote3 Averaging first across respondents who disagreed with their incumbent (i.e. had a value of −1), and then across posterior draws, we find that the average marginal effect of an increase in congruence upon the probability of voting for the Coalition incumbent is 1.2 percentage points, but the 95% credible interval surrounding this point estimate is large, running from −10.3 percentage points to 12.1 percentage points.

Table 1. Logistic regression models of incumbent voting. Models shown for first-preference and two-party preferred vote, with and without controls.

Given that the model including covariates explains a high proportion of the variance in the data and correctly predicts a large percentage of responses, there is little room to increase the precision of our estimates by adding extra control variables. In the Supplementary Information, we show by simulation that a sample of 670 respondents lacks sufficient statistical power to detect reliably an effect size of 5 percentage points. Therefore, we accept this as uninformative regarding the effects of congruence and move to estimates of aggregate-level data.

Aggregate analysis

Australian electoral data is reported at a relatively granular level, and the number of polling stations in our aggregate analysis is four times larger than the number of respondents in our individual analysis. Additionally, it is easier to detect significant differences in continuous outcomes like vote share than it is for categorical outcomes like vote choice. The primary disadvantage of analysing aggregate electoral returns is that it prevents us from drawing inferences about individuals. The secondary disadvantage of analysing aggregate data is ensuring our estimates of support for same-sex marriage are as granular as our figures for vote share requires considerable effort.

Constructing the data

We start by describing the polling places used in the election. The 2019 election comprised 8875 polling places. After restricting our analysis to static, election-day polling places only (see Supplementary Information for discussion), we are left with 7169 polling places, which we link to the smallest available aggregate-level data from the Australian Census of Population and Housing (i.e. Statistical Area Level 1, or SA1).

We next estimate a beta regression (Ferrari and Cribari-Neto Citation2004) of division-level support on a series of demographic variables derived from the SA1 data. Using that model, we generate new out-of-sample predictions using demographic data at the catchment area level. To bring these predictions in line with the known divisional level totals, we compare a population-weighted mean of out-of-sample predictions to the known total, adding a constant to each figure where the weighted mean undershoots the known total, and subtracting a constant where the weighted mean was in excess of the true figure. Further details of the procedure are given in the Supplementary Information.

The dependent variable here is the incumbent’s share of the first-preference vote between 2016 and 2019, in percentage points, for each polling place among election day voters. Information on first-preference vote shares is supplied by the AEC directly. The average share of the first-preference vote was 46% (standard deviation: 11 percentage points).

The key independent variables are the incumbent’s position on same-sex marriage, and area support for same-sex marriage. Incumbent’s position is the same measure as in the individual-level analysis. We measure area support for same-sex marriage as a net ‘yes’ vote, wherein the percentage of ‘no’ votes is subtracted from the percentage of ‘yes’ votes, such that any positive number represents a ‘win’ for the ‘yes’ campaign at the polling place level (and vice versa). Our measure of congruence is again the interaction between these two variables. Thus, if 60% of a division voted ‘yes’, and the incumbent supported SSM, the value is 60–40 = 20%; if the incumbent opposed SSM, the value is −20%. Because most Coalition MPs supported same-sex marriage, and because most divisions supported same-sex marriage, the mean value of this variable is positive (10.1 percentage points). The value of this variable is equal to or less than zero in just over one-third of polling place catchment areas.

Our control variables here mirror the earlier area-level covariates: percentage of the workforce engaged in agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and public administration; the percentage of the population which is Muslim or secular; the percentage of the population with a university degree; median total personal income in dollars per week; and the incumbent’s vote share in the previous (2016) election. Summary statistics for all variables used in the aggregate level analysis are provided in Supplementary Information Table S3.

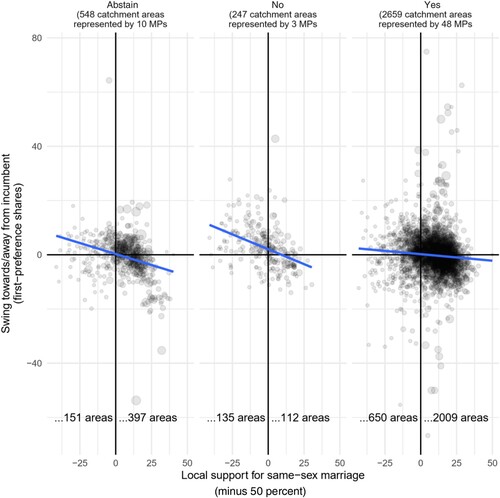

The polling place catchment area level data is shown graphically in . For Coalition incumbents who supported same-sex marriage in parliament, there is a flat relationship between local support for same-sex marriage and changes in vote share. There is a slight negative relationship between local support for same-sex marriage and vote share for MPs who opposed or abstained on the issue.

Model specification

We model the incumbents’ primary vote share using a hierarchical linear regression, with polling place catchment areas nested within electoral divisions. We use weakly informative priors except for the lagged vote share variable, where our prior – a normal distribution with a mean of 0.5 and a standard deviation of 0.5 – reflects our assumption that there is a strong positive correlation between current and lagged vote share. We include a random intercept for each division. We also model the residual variance in the model as a function of the log of the number of ordinary votes cast in each polling place to account for heteroskedasticity in vote share (i.e. polling places which serve fewer voters are more variable).

The results of two models – one with, and one without the additional control variables – are shown in . Incumbent support for SSM (measured on a −1, 0, +1 scale indicating opposition, abstention, or support) is not clearly related to vote share where all other variables are zero. Local support for SSM is however, negatively related to incumbent vote share, and can be distinguished from zero. When other variables are at zero, a 10 percentage point increase in support for SSM would reduce incumbent vote share by roughly one percentage point (i.e. −0.096 * 10).

Table 2. Multilevel linear regression models of incumbent voting. Models shown for first-preference and two-party preferred vote, with and without controls.

Although the effects of local support for SSM are clearly distinguishable from zero, the same is not true for the effects of congruence. For areas where net support for SSM is zero, a standard deviation (13.1 point) increase in congruence would yield a change in vote share of −0.1 percentage points (95% CI: −0.47 to 0.25 percentage points). While political science does not have a consistent definition of what a ‘substantively meaningful’ electoral effect is, we can rule out substantively meaningful positive effects of congruence.Footnote4

Selecting, not sanctioning?

One possible explanation of our failure to find statistically or substantively significant positive associations between congruence and vote share is that voters already took incumbents’ positions on same-sex marriage into account when they voted in the (2016) previous election. At that time, many MPs had already made public statements on the issue and legislative debate loomed large. Voters who cared about the issue therefore had some incentive to prospectively select candidates who shared their position on same-sex marriage. If voters selected candidates, they might have treated the issue of same-sex marriage as a dead letter by the time of the 2019 election.

To test this possibility, we reconstruct levels of support for same-sex marriage at the level of the 2016 polling place catchment area. Since they are interpolations of the 2017 postal survey, these estimates are not measures of support for SSM in 2016, but merely proxies: we must rely on the assumption that support for SSM in 2017 will be closely related to support for SSM in 2016. As before, we estimate a model of 2017 support for SSM at the divisional level, generate out-of-sample predictions to lower-level Census units, adjust these to match known 2017 totals, and aggregate up to the catchment areas.

We use this in a model of 2016 incumbent vote share. We use as our measure of incumbent position on same-sex marriage the 2016 positions reported in the online appendix to Carson, Ratcliff, and Dufresne (Citation2018). We interact 2016 incumbent position with our proxy for 2016 area support for SSM to give a measure of congruence. We must also deal with an additional complication: whereas in 2019 the only variation in positions on SSM was variation within coalition parties, in 2016 there was also variation within Labor. As a result, we interact all of our area-level control variables with a dummy variable which records whether or not the incumbent was a Labor incumbent. We do not interact MP characteristics with the Labor incumbent dummy, because the rationale for including those control variables was not party-specific: if age makes MPs more likely to oppose same-sex marriage, it doesn’t make Labor MPs more or less likely than Coalition MPs.

The results of models with and without area- and incumbent-level controls are shown in . (The full regression table is in Supplementary Information Table S6; descriptive statistics are in Table S5). We include interactions with party even in our most basic model. In the model without area- and incumbent-level controls, the effects of congruence are positive and different from zero, but this finding ceases to be significantly different from zero when incumbent and area-level controls are introduced. Taking the effects from the model which includes controls, we can see that the magnitude of congruence effects in 2016 (−0.007) was similar to the magnitude of congruence effects in 2019 (−0.008). The width of the credible interval is slightly narrower (0.047 units compared to 0.055 units). We have therefore slightly greater confidence that congruence had no substantively significant positive effects on incumbent first preference share in 2016. On this basis we conclude that voters neither sanctioned out-of-step incumbents in 2016 nor selected against out-of-step incumbents in 2016.

Table 3. Multilevel linear regression models of incumbent vote share. Models shown without and with controls.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have tested whether voters or areas that were more supportive of same-sex marriage sanctioned incumbents who were less supportive of SSM, and vice versa. The individual level evidence is uninformative and consistent with large effects either way. We argue that this is due to the difficulties of detecting interaction effects in logistic regressions with moderate sample sizes. For this reason, we turn to aggregate level evidence, and interpolate the results of the 2017 postal survey using a wealth of Census data. We find that there was no substantively significant association between incumbents being out-of-step with an area and lower vote shares in that area. We repeat this exercise for the 2016 election, and find effects that are also substantively insignificant.

This finding is important for democratic accountability in Australia but also beyond. If voters do not sanction incumbents who hold different issue positions, then the match between what a division thinks on an issue and how its representative act on that issue is guaranteed only by the bonds of party (ALP and Coalition incumbents vote differently on SSM as they do on many other issues, and divisions with different opinions on SSM voted for ALP or Coalition candidates at very different rates) and by MPs’ intrinsic motivation. Party is a hugely important structuring force in modern representative democracy, but representatives from the same party often represent areas with very different opinions. Labor holds both the division that was most opposed to SSM (Blaxland) and two of the three divisions that were most supportive (Sydney and the former division of Melbourne Ports). If we ask, ‘what ensures representatives from the same party representing these different areas follow their area’s views on issues’, then the conclusion of this paper is ‘neither electoral sanctioning nor selection’. We do not claim that same-sex marriage had no impact on this election. Same-sex marriage was a live issue, but not one that translated into candidate vote shares.

Our study is also important for other countries which use single member districts to elect legislators. The alternative vote in Australia is supposed to generate stronger incentives to cultivate a personal vote than either single member plurality with party endorsement (of the kind used in Canada and the United Kingdom) or a two-round majority system (of the kind used in France). It’s reasonable to think that if there are no substantively significant sanctioning effects on a high-profile issue under the alternative vote, then substantively significant sanctioning effects are also unlikely under single member plurality or a two-round system.

Our study has certain limitations. We are limited in our ability to draw causal claims about individuals, and must instead draw inferences about associations at the level of areas. We have, as far as is possible, tried to control for potential confounders and therefore make possible a causal interpretation, but this interpretation depends on the unverifiable claim that there are no omitted variables. We also lack information on the position on same-sex marriage of the nearest competitor candidate, which previous research has found affects the magnitude of electoral sanctioning (Hollibaugh, Rothenberg, and Rulison Citation2013).

A related question pertains to whether there is something unique about same-sex marriage as a policy issue. It is certainly not as salient a question as economic management, the environment, or health or education (Baker Citation2022), but such central issues of government rarely get delegated to voters directly. Of the three most recent extra-legislative decision-making processes in Australia – this plebiscite, the republic referendum in 1999 and the Voice referendum in 2023 – same-sex marriage is arguably the most salient (having emerged on the national agenda around 2004) but also the least institutionally significant (not requiring Constitutional amendment to enact). Each issue divided the conservative parties more than those on the left and required legislators to state their positions in the parliament. Where public stances on the republic and Voice referendums pre-empted any certainty about their electorates’ positions, Members had to show their hands on same-sex marriage after their electors had already shown theirs. We might expect then that if ever voters were to punish disagreement with their views (on an unusually salient issue), it would be now. The question is not necessarily whether this null result is generalisable as whether it is suggestive of even less sanctioning behaviour on adjacent policy issues.

If there is no meaningful electoral sanctioning for issue positions which are out-of-step, how are we to proceed? We know that MPs from the same party do respond to local opinion (Carson, Ratcliff, and Dufresne Citation2018), and so our findings must cause us to search for other mechanisms which can explain this pattern of representation, including but not limited to MP adaptation to local preferences and non-electoral selection mechanisms such as the initial selection of candidates by local parties.

article-2023- Supplementary Information - JS.pdf

Download PDF (897.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chris Hanretty

Chris Hanretty is a Professor of Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London. He carries out research on public opinion and representation, and on courts and how judges behave.

Jill Sheppard

Jill Sheppard is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the Australian National University, where she studies electoral behaviour, public opinion, survey research methods, and Australian politics.

Notes

1 There is no suggestion that those who retired (Julie Bishop, Steven Ciobo, Luke Hartsuyker, Michael Keenan, Craig Laundy, Kelly O’Dwyer, Christopher Pyne and Ann Sudmalis) did so because they were out-of-step with their constituents – indeed, the retirees had significantly higher levels of congruence than those who continued (66% compared to 58%).

2 We take as our principal source for each religion’s position on same-sex marriage the descriptions given in Perales, Bouma, and Campbell (Citation2019, 114–115). Religions which opposed SSM include the Roman Catholic church, the Uniting Church, the Orthodox church, Presbyterian churches, Eastern Catholic, Islam and Sikhism. Religions which supported SSM include Buddhism and Hinduism. Religions with a mixed view include the Church of England, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Judaism and other non-specified religions.

3 Note that we do not also simulate the effects of the change of position (for example, the tendency of respondents who support SSM to vote for Coalition candidates at lower rates).

4 Fortunato and Monroe (Citation2020) argue that changes in vote share of less than 2 percentage points – the fourth quantile of margins of victory in US House elections – should be considered negligible. The fourth quantile of margins of victory in the 2019 election to the Australian House of Representatives was 1.58 percentage points. The posterior probability of a standard deviation change in congruence having an effect this large is (approximately) zero. It is therefore very unlikely that there are meaningfully large positive effects of congruence in our case.

References

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Ryan Finnigan. 2019. “Rights for Same-Sex Couples and Public Attitudes Toward Gays and Lesbians in Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 52 (6): 868–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018797947.

- Aitkin, Don. 1988. “‘Countrymindedness’: The Spread of an Idea.” In Australian Cultural History, edited by S. L. Goldberg and F. B. Smith, 50–57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Armenia, Amy, and Bailey Troia. 2017. “Evolving Opinions: Evidence on Marriage Equality Attitudes from Panel Data.” Social Science Quarterly 98 (1): 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12312.

- Baker, Emily. 2022. “Australians’ Most Important Election Issues, According to Vote Compass.” ABC News, April 21. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-04-22/vote-compass-federal-election-issues-data-climate-change-economy/101002116.

- Bean, Clive. 1990. “The Personal Vote in Australian Federal Elections.” Political Studies 38 (2): 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1990.tb01491.x.

- Bowler, Shaun, David M. Farrell, and Ian McAllister. 1996. “Constituency Campaigning in Parliamentary Systems with Preferential Voting: Is There a Paradox?” Electoral Studies 15 (4): 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(96)00036-4.

- Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder. 2006. “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14 (1): 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpi014.

- Bürkner, Paul-Christian. 2017. “brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan.” Journal of Statistical Software 80 (1): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01.

- Cameron, Sarah, and Ian McAllister. 2019. “The 2019 Australian Federal Election: Results from the Australian Election Study.” Australian National University. https://australianelectionstudy.org/wp-content/uploads/The-2019-AustralianFederal-Election-Results-from-the-Australian-Election-Study.pdf.

- Canes-Wrone, Brandice, William Minozzi, and Jessica Bonney Reveley. 2011. “Issue Accountability and the Mass Public.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 36 (1): 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-9162.2010.00002.x.

- Carson, Andrea, Shaun Ratcliff, and Yannick Dufresne. 2018. “Public Opinion and Policy Responsiveness: The Case of Same-Sex Marriage in Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 53 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2017.1381944.

- Charnock, David. 1996. “National Uniformity, and State and Local Effects on Australian Voting: A Multilevel Approach.” Australian Journal of Political Science 31 (1): 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361149651274.

- Charnock, David. 2007. “Plus ça Change … ? Institutional, Political and Social Influences on Local Spatial Variations in Australian Federal Voting.” Australian Journal of Political Science 42 (4): 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361140701595783.

- Clements, Ben. 2014. “Partisan Attachments and Attitudes Towards Same-Sex Marriage in Britain.” Parliamentary Affairs 67 (1): 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gst003.

- Converse, Philip E., and Roy Pierce. 1986. Political Representation in France. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Donovan, Todd. 2014. “The Irrelevance and (New) Relevance of Religion in Australian Elections.” Australian Journal of Political Science 49 (4): 626–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2014.963505.

- Ferrari, Silvia, and Francisco Cribari-Neto. 2004. “Beta Regression for Modelling Rates and Proportions.” Journal of Applied Statistics 31 (7): 799–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266476042000214501.

- Fortunato, David, and Nathan W. Monroe. 2020. “Agenda Control and Electoral Success in the US House.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (4): 1583–1592. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000418.

- Gelman, Andrew, and Gary King. 1990. “Estimating Incumbency Advantage Without Bias.” American Journal of Political Science 34 (4): 1142–1164. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111475.

- Golder, Matt, and Jacek Stramski. 2010. “Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00420.x.

- Gravelle, Timothy B., and Andrea Carson. 2019. “Explaining the Australian Marriage Equality Vote: An Aggregate-Level Analysis.” Politics 39 (2): 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395718815786.

- Hanretty, Chris, Benjamin Lauderdale, and Nick Vivyan. 2017. “Dyadic Representation in a Westminster System.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 42 (2): 235–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12148.

- Hanretty, Chris, Jonathan Mellon, and Patrick English. 2021. “Members of Parliament Are Minimally Accountable for Their Issue Stances (and They Know It).” American Political Science Review 115 (4): 1275–1291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000514.

- Hill, Kim Quaile, and Patricia A. Hurley. 1999. “Dyadic Representation Reappraised.” American Journal of Political Science 43 (1): 109–137. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991787.

- Hollibaugh, Gary E., Lawrence S. Rothenberg, and Kristin K. Rulison. 2013. “Does It Really Hurt to Be Out of Step?” Political Research Quarterly 66 (4): 856–867. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912913481407.

- Honaker, James, Gary King, and Matthew Blackwell. 2011. “Amelia II: A Program for Missing Data.” Journal of Statistical Software 45 (7): 1–47. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v45/i07/.

- Horiuchi, Yusaku, and Andrew Leigh. 2009. “Estimating Incumbency Advantage: Evidence from Multiple Natural Experiments.” Unpublished Paper.

- Jacobson, Gary. 1996. “The 1994 House Elections in Perspective.” Political Science Quarterly 111 (2): 203–223. https://doi.org/10.2307/2152319.

- Mackerras, Malcolm. 2012. “The Results and the Pendulum.” In Julia 2010: The Caretaker Election, edited by Marian Simms and John Wanna, 315. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Maley, Jacqueline. 2019. “‘We’ve Got a Dilemma’: Meet the ‘Liberal’ Backers of Zali Steggall Out to Retire Tony Abbot.” Sydney Morning Herald, May 2. https://www.smh.com.au/federal-election-2019/we-vegot-a-dilemma-meet-the-liberal-backers-of-zali-steggall-out-to-retire-tony-abbott-20190501-p51j37.html.

- Mansbridge, Jane. 2003. “Rethinking Representation.” American Political Science Review 97 (4): 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000856.

- McAllister, Ian. 2015. “The Personalization of Politics in Australia.” Party Politics 21 (3): 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813487111.

- McAllister, Ian, Clive Bean, Rachel Gibson, Toni Makkai, Jill Sheppard, and Sarah Cameron. 2019. “Australian Election Study 2019 [Data File].” https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10 .26193/KMAMMW.

- McAllister, Ian, and Feodor Snagovsky. 2018. “Explaining Voting in the 2017 Australian Same-Sex Marriage Plebiscite.” Australian Journal of Political Science 53 (4): 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2018.1504877.

- McKeown, Deirdre. 2018. “Chronology of Same-Sex Marriage Bills Introduced into the Federal Parliament: A Quick Guide.” Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1718/Quick_Guides/SSMarriageBills.

- Meng, Xiao-Li, and Donald Rubin. 1992. “Performing Likelihood Ratio Tests with Multiply-Imputed Data Sets.” Biometrika 79 (1): 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/79.1.103.

- Miller, Warren E., and Donald E. Stokes. 1963. “Constituency Influence in Congress.” American Political Science Review 57 (1): 45–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952717.

- Morgan, Stephen L., and Christopher Winship. 2015. Counterfactuals and Causal Inference. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nyhan, Brendan, Eric McGhee, John Sides, Seth Masket, and Steven Greene. 2012. “One Vote Out of Step? The Effects of Salient Roll Call Votes in the 2010 Election.” American Politics Research 40 (5): 844–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X11433768.

- Packham, Colin, and Jonathan Barrett. 2019. “‘Time’s Up Tony’: Australian Conservatives Targeted in May Election.” Reuters, April 11. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-election-moderates/timesup-tony-australian-conservatives-targeted-in-may-election-idUSKCN1RM310.

- Perales, Francisco, Gary Bouma, and Alice Campbell. 2019. “Religion, Support of Equal Rights for Same-Sex Couples and the Australian National Vote on Marriage Equality.” Sociology of Religion 80 (1): 107–129. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sry018.

- Pitkin, Hanna F. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rehfeld, A. 2006. “Towards a General Theory of Political Representation.” The Journal of Politics 68 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00365.x.

- Robinson, Geoff. 2015. “Regional Place-Based Identities and Party Strategies at the 2013 Federal Election.” In Abbott’s Gambit: The 2013 Australian Federal Election, edited by Carol Johnson, John Wanna, and Hsu-Ann Lee, 249–274. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Rogers, Steven. 2017. “Electoral Accountability for State Legislative Roll-Calls and Ideological Representation.” American Political Science Review 111 (3): 555–571. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000156.

- Saward, Michael. 2010. The Representative Claim. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schwarz, Susanne, and Alexander Coppock. 2020. “What Have We Learned About Gender from Candidate Choice Experiments? A Meta-Analysis of 42 Factorial Survey Experiments.” https://alexandercoppock.com/projectpages_SC_gender.html.

- Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A., Michael Malecki, and Brian F. Crisp. 2010. “Candidate Gender and Electoral Success in Single Transferable Vote Systems.” British Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 693–709. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712340999010X.

- Sevi, Semra. 2021. “Do Young Voters Vote for Young Leaders?” Electoral Studies 69:102200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102200.

- Studlar, Donley T., and Ian McAllister. 1994. “The Electoral Connection in Australia: Candidate Roles, Campaign Activity, and the Popular Vote.” Political Behavior 16 (3): 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01498957.

- Van den Akker, Hanneke, Rozemarijn Van der Ploeg, and Peer Scheepers. 2013. “Disapproval of Homosexuality: Comparative Research on Individual and National Determinants of Disapproval of Homosexuality in 20 European Countries.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 25 (1): 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edr058.

- Wilson, Tom, Fiona Shalley, and Francisco Perales. 2020. “The Geography of Australia’s Marriage Law Postal Survey Outcome.” Area 52 (1): 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12558.

- Wolkenstein, Fabio, and Christopher Wratil. 2021. “Multidimensional Representation.” American Journal of Political Science 65 (4): 862–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12563.