Abstract

For decades, geography has claimed to be the school subject with a unique and powerful contribution to Environmental Education and, subsequently, Education for Sustainable Development. Empirical evidence seems to support this agenda showcasing that geographical knowledge, defined as human-environment interaction, can better equip students with the knowledge required in relation to ESD-topics and thus help to work towards a more sustainable future than any other school subject. However, despite the efforts of the last three decades, there is a clear gap between the claim and the reality of geography’s role in ESD. Therefore, using the case of Germany, this article discusses three dimensions of this gap to assist geography in making the meaningful contribution to young people’s lives that it has promised for decades.

1. Introduction

The 2022 regional meeting of geography teachers working in the state of Schleswig-Holstein took place under the heading “Geography–The Subject of the Future”. A panel of academics, geography teachers, former high-school students, and activists debated geography’s contribution to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Following the habitual pattern, stakeholders stressed the unique contribution our school subject makes to ESD and reinforced McKeown and Hopkins (Citation2007, p. 18) claim that “[…] geography could claim ESD [as its own]”. Some panelists viewed Fridays for Future as clear proof of geography’s value and core position in ESD. However, surprisingly for the attendees and panelists, the participating Fridays for Future activist pointed out that, after being exposed to a boring geography lesson consisting of watching a documentary about the dying planet, Greta Thunberg felt left alone with only morals and values but without any answers as to why there was so little action in the face of the global catastrophe. If at all, in the activist’s reading, geography was one of the leading causes why Thunberg saw herself forced to start her weekly protests.

These diverging positions only offer some glimpses at geography’s complex disciplinarity (Disziplinarität, cf. Reh, Citation2018). In recent years, teachers, curriculum designers, and geography educators, among others, have strongly embraced ESD (Haubrich, Reinfried, & Schleicher, Citation2007: IGU-CGE, Citation2016) as school geography’s disciplinary core. Nonetheless, when comparing claim and reality, the promise of the self-proclaimed flagship subject of ESD to best educate for a more sustainable future requires some critical examination. It is the ambition of this article to make a new contribution to such an exercise by looking into the links between ESD and geographical knowledge using Germany as its case study. Against the backdrop of geography’s disciplinarity, this contribution explores definitions of geographical knowledge in curricula and educational standards. Subsequently, this article turns its attention to the role of physical geography and its importance for geographical knowledge before reflecting on the role of ethics and morals for geography in service of ESD.

2. Geographical knowledge and ESD

Over the last decade, geography educators attempted to move matters of knowledge to the forefront of the debate. At the heart of the debate lies a theory imported from the sociology of education revolving around the three Futures heuristic and the concept of powerful knowledge (Young & Muller, Citation2010). Mostly within the framework of GeoCapabilities, primarily conceptual work (e.g. Uhlenwinkel, Béneker, Bladh, Tani, & Lambert, Citation2017; Morgan, Hordern, & Hoadley, Citation2019) coined the term powerful disciplinary knowledge (PDK, cf. Lambert, Citation2017). Going beyond the introduction of theoretical ideas from the sociology of education into the context of geography education, Maude (Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2020, Citation2022) contributed significantly to operationalizing PDK within geography. Boehm, Solem, and Zadrozny (Citation2018) established powerful geography as an alternative conceptualization of geographical knowledge within the North-American context. However, as Deng (Citation2022) found, the GeoCapabilities approach faces several challenges, given that it attempted to connect to fundamentally exclusive perspectives, namely Sen and Nussbaum’s concept of capabilities to Young and Muller (Citation2010) ideas of powerful knowledge. These contradictions became particularly apparent when explored within cross-curricular objectives and grand challenges, such as (E)SD.

Concurrently, over the last several decades, equally intensive scholarship looked into geography’s contribution to ESD. Informed by such scholarship and following a global agreement among geography educators, both the Lucerne Declaration on Geographical Education for Sustainable Development (Haubrich et al., Citation2007) and the 2016 International Charter on Geographical Education (IGU-CGE, Citation2016) reinforced geography’s significant contribution to ESD.

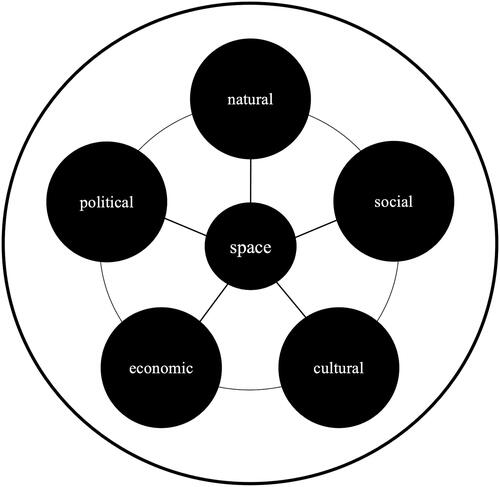

Rather than working with a pre-defined geographical knowledge claiming universal validity, studies looking into geography’s contribution to ESD first and foremost reconstructed, often in an international comparative perspective, specific understandings of geographical knowledge while juxtaposing them with (E)SD. For example, Bagoly-Simó (Citation2013, Citation2014) comparative studies of Bavarian (Germany), Mexican, and Romanian curricula showed that geography’s contribution to ESD rested on a mix of geographical key concepts, ESD-topics addressing humanity’s current and future grand challenges, and cross-curricular objectives, such as Environmental Education (EE) and ESD. Thereby, the very definition of geographical knowledge proved to be heterogeneous. In Mexico, geographical knowledge gravitates around the concept of space, explored through ecological, economic, social, cultural, and political perspectives. Additional key concepts are place, environment, region, landscape, and territory. In contrast, Romanian school geography derived the coordinates of its subject-specific knowledge from academic geography’s epistemology.

The results also showed that stakeholders developing geography curricula seem to proactively increase the school subject’s conceptual (Bagoly-Simó, Citation2014) and thematic (Bagoly-Simó, Citation2013) contribution to ESD by surpassing the requirements of EE and ESD outlined in the cross-curricular objectives valid for all subjects. Consequently, curriculum authors (re)defined geographical knowledge based on its potential to contribute to EE/ESD as normatively defined in the cross-curricular objectives. While aiming at increasing geography’s potential contribution to a more sustainable future, concurrently, a strong contribution to strengthening the subject’s position in a continuously questioned canon of school subjects was also at stake. Moving (E)SD to the forefront profoundly impacted geographical knowledge in Germany.

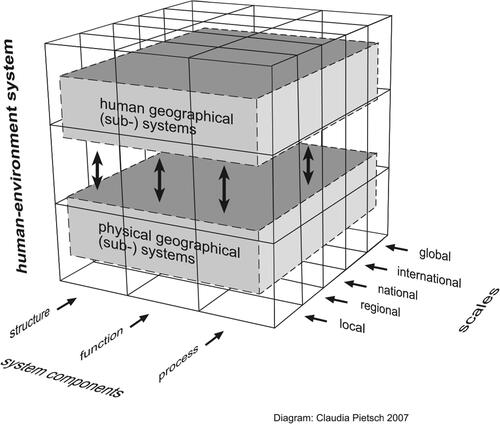

The German federal educational system has a multitude of geography curricula for primary and secondary education across its 16 federal states (Länder). Despite this diversity, the Educational Standards in Geography for the Intermediate School Certificate (DGfG 3Citation2014), first published in German in 2006, brought about a convergent trend across the states given their rapid implementation during the curricular revisions at the federal state level (cf. Schöps, Citation2017). The Standards (DGfG 32014, p. 10) defined geographical knowledge as “[…] the Earth as human-environment or human-Earth system from a spatial perspective” aiming at equipping students with the “[a]bility to understand spaces at different scales as physical and human geographical systems and to analyse the interrelations between man and environment” (DGfG 32014, p. 9). Unlocking geographical knowledge rests on three sets of basic concepts (), namely the human-environment system (encompassing the human geographical and the physical geographical (sub-)system), scales (from the local to the global), and system components (structure, function, and process).

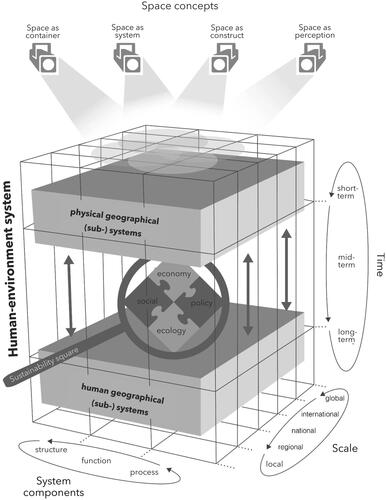

Given the systemic approach underlying the conceptualization of geographical knowledge, school geography in the German federal states that implemented the Standards, created favorable preconditions to foster SD based on the study of human-environment systems within the overall framework of ESD. Fögele (Citation2016) proposed to expand the conceptualization of geographical knowledge by adding three further basic concepts, namely sustainability (ecology, economy, social, policy), time (short-, mid-, and long-term), and space (as container, as system, as perception, and as construct). Thereby, sustainability links the two (sub-)systems constituting the human-environment system, while the four space concepts shed light on the system as reflectors on a stage ().

Figure 2. Geography’s basic concepts (Fögele, Citation2016, p. 73, amended).

While increasing the variety of basic concepts could enrich geographical knowledge, Fögele’s (Citation2016) expanded basic concepts contribute to an overall impoverishment of geographical knowledge in two ways. On the one hand, the expanded model cements the normatively set understanding of geographical knowledge based on a systemic approach. Also, the addition of sustainability (conceptualized in a highly unusual way, namely divided into ecology, economy, social, and policy) further impoverishes geographical knowledge as it excludes any alternative perspective than sustainability to explore the human-environment system. On the other hand, instead of questioning whether exploring human-environment interrelations solely as human-environment systems is a timely way to grasp geographical knowledge, Fögele (Citation2016) adds Wardenga’s (Citation2002) four space concepts to the original model. However, the concepts represent the four phases in a model describing the historical development of spatial thinking in German academic geography. Consequently, space as container, in terms of a descriptive tradition rooted in a Hettnerian approach, along with space as system, as already represented in the model published in the Standards (), stand for two outdated stages of spatial thought in considerable parts of academic geography. Spaces as perception and as constructed are characteristic of more recent scholarship originating mainly from human geography. However, representing the four concepts as reflectors shedding light on the human-environment cube merely visualizes the Popperian argument of critical rationalism (Scheinwerfertheorie, cf. Popper, Citation1992), namely the system remains the only object of observation whereas everything apart from the system in the spotlight remains in the dark. Moreover, the reflector representing space as system can in itself be regarded as the human-environment system already introduced as the central part of the cube, thus leading to a tautology.

In sum, Fögele’s (Citation2016) reconceptualized model of geographical knowledge moves ESD to the core of the original model featured in the Standards (DGfG 32014). In its entirety, the revision, while unmistakably aiming for geography’s more substantial contribution to ESD, presents a self-contradictory, impoverished, and outdated conceptualization of humans and their environment. In contrast, the Mexican curriculum incorporates SD into the core of geographical knowledge () and enables a more contemporary perspective on humans and the environment. As opposed to Fögele’s (Citation2016) representation, the Mexican model both allows and encourages additional perspectives than SD beyond a systemic perspective. Also, additional key concepts, such as place, environment, region, landscape, and territory, further enrich the geographical knowledge offered in lower secondary education and open the possibility to explore perceived and constructed spaces outside a pre-defined systemic framework. In a similar vein, key concepts habitually used in other countries (e.g. Brooks, Citation2018) originate from geographical scholarship and, based on the diversity of approaches they represent, allow a broader conceptualization of geographical knowledge, ultimately creating a much more favorable framework to explore ESD.

Figure 3. Key concepts in Mexico (SEP, Citation2011, p. 16, amended).

One of the key arguments that both international (Haubrich et al., Citation2007; IGU-CGE, Citation2016) and national normative documents (e.g. DGfG, 32014) stress is that geography’s unique contribution to educating young generations lies in its concurrent consideration of societies and the environment, often conceptualized in terms of human-environment interactions or human-environment systems. More concretely, geography combines elements of science (i.e. physical geography) with those of social science (i.e. human geography), making it the ideal candidate to foster ESD (e.g. McKeown & Hopkins, Citation2007). Therefore, the following section takes a closer look at physical geography.

3. (The missing) physical geography

Geographical knowledge conceptualized as a human-environment system tends to either follow geography’s traditional epistemological physical-human divide or address its sub-disciplines within an integrative perspective (Castree, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2014c). The German (re)conceptualization of geographical knowledge (DGfG 32014; Fögele, Citation2016) remains highly dedicated to the human-environment discourse, defining the school subject as uniquely bridging science and social science. Physical geography and elements of earth sciences are expected to contribute to the science dimension.

While textbooks continue to play a crucial role in German geography classrooms, and even more so during and in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic (Bagoly-Simó, Hartmann, & Reinke, Citation2020), during lesson planning, teachers heavily rely on other educational media. Teachers’ professional journals, the second-most important source of inspiration for lesson planning, publish ideas, fragments of lesson plans, and conceptual work on various topics relevant to geography as a school subject. In a comparative study of Germany and Britain, Bagoly-Simó and Uhlenwinkel (Citation2016) analyzed justifications for teaching physical geography from 1979 to 2013. Two traditional physical-geographical topics were investigated: volcanoes (geomorphology) and weather/climate. The authors primarily focused on the reasoning authors gave concerning the importance of the proposed topic to teaching and learning geography. Looking at the German subsample, the results showed an overall shift in the arguments about why physical geography was relevant to geography. Some differences applied to the two topics.

Concerning volcanoes, during the first decades, authors argued the importance of the topic being its contribution to cognitive reasoning and, thus, to subject-matter understanding. Six years after the publication of the German National Standards (DGfG 32014), beginning with 2012, the journals progressively embraced the thought that volcanoes were solely one of many content elements that served the purpose of skill acquisition.

In the case of the topic weather/climate, immediately in the aftermath of the 1992 Earth Summit, Bagoly-Simó and Uhlenwinkel (Citation2016) identified an experimental and aimless phase where authors’ reasoning pointed towards students, their interests, climate change, the global emergency, and political constraints alike. Beginning with 2011, authors argued that weather/climate became increasingly important as a means to sensitize young individuals in light of the global catastrophe; however, the articles failed to equip students with the necessary geographical knowledge.

Based on their results, Bagoly-Simó and Uhlenwinkel (Citation2016) second Dufour’s (Citation2015) claim that a critical physical geography is socially expected to participate in the development of a joint epistemic framework that not only allows but also demands physical geography to (re)define its role within the human-environment rhetoric dominating academic geography. It seems equally important to reflect on physical geography’s contribution to geographical knowledge. In this respect, Bagoly-Simó and Uhlenwinkel (Citation2016) findings strongly question geography’s suitability to foster ESD using an approach of human-environment systems. Both the German Standards (DGfG, 32014) and Fögele’s (Citation2016) extended model of basic concepts rest on a physical-geographical input to the physical (sub-)system ( and ). However, physical geography seems to have shrunken to a means to an end, namely contributing to skills development in gathering information/methods (DGfG, 32014) or sensitization towards the objectives of ESD.

Of course, catering to the goals of ESD is hardly surprising since the German discourse linked physical geography to EE early on. Härle (Citation1980), while diagnosing the geo-ecological deficit of school geography, envisioned a physical-geographical input to the school subject serving the purposes of moral education promoting green values. His anti-rational and anti-political arguments won against Jannsen’s (Citation1982) proposal to view physical geography’s contribution to civics education in offering rational and scientific answers to politically relevant questions through critical thinking. Haubrich (Citation1994) incorporated Härle’s (Citation1980) views into his call for more earth sciences in geography, using Gaia meditation as a means for its promotion. This proposal ultimately found its way into IGU-CGE’s first International Charter (Haubrich, Citation1992). Criticism from both the epistemological (Schultz, Citation1996, Citation1997, Citation1999) and the methodological (Lethmate, Citation2000a, Citation2000b, Citation2001) perspective argued for rational reasoning; however, Haubrich’s (Citation1994) normative stance resisted any criticism. Finally, the turn towards competencies-based education reshaped physical geography in schools by defining it through pedagogy instead of its object. Consequently, physical geography’s value ultimately shrank to student activities using experiments (e.g. Wilhelmi, Citation2014).

Overall, both the trajectory and the current state of physical geography as an input to geography as a school subject best suited to foster ESD point towards an urgent need for reconceptualization. In its current form, it is doubtful whether physical geography can deliver the science-based input to a human-environment system that qualifies geography to be the best subject to foster ESD.

Naturally, competencies-based education, in general, and geography in Germany, in particular, often fall short of knowledge replacing it with generic skills or morals and ethics (Uhlenwinkel, Citation2017). However, reconfigurations of physical geography look back on a longer tradition of debates rooted in morals (cf. Härle, Citation1980; Haubrich, Citation1994). Therefore, a closer inspection of the role of ethics and morals in geography curricula is a reasonable next step.

4. Morals and ethics

Ethics and morals, an important facet of EE (e.g. Öhman, Citation2004), play an equally important role in ESD (e.g. Östman, Citation2010) and other adjectival educations. Scholarship in geography education explored morals and ethics (Ballantyne, Citation1999; Rolston, Citation2002; Al-Naki, Citation2004; Haubrich, Citation2009; Applis, Citation2015, Citation2016; Applis & Fögele, Citation2016) within various contexts, covering, among others, content, educational aims, initial teacher education, and geography’s contribution to EE and ESD. This is hardly surprising, given the postulation of the initial International Charter on Geographical Education (Haubrich, Citation1992, p. 1.9), namely, “Geographical Education contributes to [Environmental and Development Education] by ensuring that individuals become aware of the impact of their own behavior and that of their societies, have access to accurate information and skills to enable them to make environmentally sound decisions, and to develop an environmental ethic to guide their actions”. Despite the Lucerne Declaration (Haubrich et al., Citation2007) and the revised International Charter (IGU-CGE, Citation2016) entailing fewer ethical and moral facets, scholarship—mainly in Germany—repeatedly addressed their importance, particularly concerning ESD. As these German perspectives prioritize behavior based on competencies that often are void of knowledge, as opposed to international trends (e.g. do Céu Roldão, Citation2013), it seems necessary to look into the role that morals and ethics play in German geography curricula with particular regards to ESD.

In a historical study of the geography curricula for lower secondary education in Berlin following the reunification, Bagoly-Simó (Citation2022) explored how geographical knowledge changed during the implementation of a competencies-based education resting on standards and operating within the moderate-constructivist framework. Exploring change over three decades, as expressed in three curricula (implemented in 1992, 2006, and 2015), the study distilled two main trends leading to an overall alignment of geography’s educational objectives with those of ESD, of which the first trend constitutes a prerequisite of the second development.

On the one hand, geographical knowledge underwent a metamorphosis targeting an ambition to best serve the purposes of ESD. Despite the calls for more integration from the academic discipline (Castree, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2014c), school geography in Berlin maintains geography’s traditional epistemological physical-human divide. However, embracing the concept of SD resulted in instituting yet another division of the world into ecologic, economic, and social dimensions (Bagoly-Simó, Citation2022). Fögele (Citation2016, see Section 2) adopted a similar approach when extending the model of basic concepts by adding the four elements of sustainability, namely ecologic, economic, social, and political. Both conceptualizations are compatible with geography’s physical-human divide. This fact made the alignment of a systemic perspective of geographical knowledge (cf. and ) with the concept of SD easy. Still, adding yet another pre-defined division of the world to the already existing epistemological divide did little to navigate the challenges posited by the outdated concept of space prescribing a primarily systemic perspective on the geographical space, which is fully compatible with the concepts of sustainability and the normative goals of an ESD, but can hardly be reconciled with contemporary approaches to space (e.g. space as perception, space as construct, Wardenga, Citation2002).

On the other hand, along with the alignment of geographical knowledge offering the best prerequisites for the optimal contribution to ESD, the curricular documents also incrementally increased the importance of morals and values at the expense of knowledge-based evaluation and decision-making. Two factors facilitated this shift. First, transitioning to a competencies-based education required the formulation of areas of competencies. Starting with 2006, lower secondary geography in Berlin aimed to achieve spatial awareness and develop spatial responsibility to secure a livelihood for future generations (Bagoly-Simó, Citation2022). The geography curriculum currently in place follows the main aim of supporting students in acquiring competencies to act geographically in terms of SD (Bagoly-Simó, Citation2022). In doing so, it seems to voluntarily give up the multi-perspectivity required not least by the Beutelsbach Consensus (Schiele & Schneider, Citation1987) since the end of World War Two and replace it with only one perspective, namely that of SD. This development is a contradictio in adjecto given ESD’s requirement for multi-perspectivity and participation, showcasing that the alterations of the geography curricula are yet to reach their goal, namely the alignment of geography with ESD.

Second, competencies-based education also led to a distinction between knowledge-based evaluation and decision-making and “judgment competence” (Applis, Citation2016), the latter resting on values and morals. As repeatedly shown (Dantas Barbosa, Citation2006; Bagoly-Simó, Citation2022), the curricula progressively replaced what, in the language of competencies-based education, may be considered a rational judgment (based on sets of criteria and following facts and knowledge) with value judgment or judgment competence where ESD moves to the forefront at the expense of knowledge. In doing so, the two waves of curricular reform in Berlin shifted the objectives of geography from a subject serving knowledge-based evaluation and decision-making to one that prioritizes values and morals at the cost of and with diminished attention to knowledge. While ESD relies heavily on morals and ethics, it still claims to require knowledge from many fields to work towards a more sustainable future (de Haan, Citation2008).

5. Navigating self-imposed dead ends

Expert knowledge from all fields clearly diagnoses the necessity for change to secure a (more sustainable) future for present and future generations. Both the power and responsibility of all forms of education in the quest to achieve a more sustainable livelihood remain uncontested. Therefore, school subjects—the structural units where learning and teaching take place—carry the responsibility for revising their contribution to this global challenge. A range of strands, including normative documents (Haubrich et al., Citation2007), conceptual contributions (e.g. McKeown & Hopkins, Citation2007), and empirical studies (Bagoly-Simó, Citation2013; Bagoly-Simó & Hartmann, Citation2021) argue that geography can make a unique contribution to achieving a (more sustainable) future by fostering ESD. However, as the German case study shows, reaching the overtly ambitious claims of universal validity in regional and national settings may prove challenging.

Knowledge conceptualizations, such as the three Futures and PDK, rooted in the sociology of education (Young & Muller, Citation2010; see also Maude, Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2020, Citation2022; Lambert, Citation2017; Boehm et al., Citation2018), have fostered lively scholarly activity and debate. Yet their relevance and validity is questioned by some. As Deng (Citation2022) argues, PDK and the capabilities approach underlying GeoCapabilities (cf. Uhlenwinkel et al., Citation2017) seem to rest on fundamentally unreconcilable theoretical foundations. Therefore, this article turns to Reh’s (Citation2018) concept of disciplinarity (Fachlichkeit) as a fresh lens to address matters of geographical knowledge.

As in the case of any other school subject, geography’s disciplinarity emerges from constructive processes in the classroom (Caruso & Reh, Citation2021), based on the need to pass on knowledge and practices of interaction. In Reh’s (Citation2018) reading, a school subject’s disciplinarity (Fachlichkeit) refers to a specific way of both organizing knowledge and operating with it—a genuine practice of knowledge that distinguishes the school subject in this case from others by its particular ways of sorting, organizing, standardizing, and connecting (elements of) knowledge. Driven by the need/requirement/desire to pass on knowledge, school subjects develop their signature practices to generate, conserve, and transmit knowledge. Such practices inevitably create consensus and dissensus, stress similarities and differences, and develop a unique terminology that ultimately facilitates communication and exchange. In Reh’s (Citation2018) reading, academic disciplines and school subjects sharing a common denomination may rest on different concepts and content emerging from heterogeneous organizing practices carried out in separate institutions. Unlike academic disciplines, the disciplinarity of a school subject always incorporates its main function of transmitting or mediating knowledge through practices of interaction. Therefore, in historical terms, Reh (Citation2018) argues traditional school subjects emerged parallel to the academic disciplines and developed their own epistemology under different framework conditions than academic disciplines did. Therefore, Reh (Citation2018) rejects the idea of school subjects being derived from a pre-existing order of knowledge and practices. Moreover, within the German context, school geography precedes the establishment of the academic discipline at German universities.

The three exemplary mismatches between the global claim regarding geography’s contribution to ESD and the German attempt to meet them originate in the subject’s particular disciplinarity. The following three guiding questions aim to open up the discussion on geographical knowledge and ESD in light of the school subject’s disciplinarity.

(1) What is the role of key/basic concepts in defining geographical knowledge prescribed in curricula and taught in classrooms? Traditionally, geographical concepts in the form of key or basic concepts define the core of geographical knowledge. Along with the Anglophone tradition (cf. Brooks, Citation2018), Mexican, French, German and Austrian curricula rely on key or basic concepts to define geographical knowledge (cf. Bagoly-Simó, Citation2014). Historically, Anglophone curricula relied on a selection of key concepts originating from academic geography’s scholarship (e.g. Clifford, Holloway, Rice, & Valentine, Citation2009) that proved relevant for school education considering educational objectives, societal expectations, and political frameworks. However, other countries followed a different path. As the German case study shows, author collectives selected the key or basic concepts constituting the geographical knowledge in geography curricula. Such decisions redefine the core of geographical knowledge by evaluating academic progress in geography (expert knowledge) in light of the school subject’s educational objectives, epistemological tradition, and teachers’ personal geographies. In some cases, such processes may lead to a disciplinarity resting on outdated or even tautological knowledge (cf. DGfG, 32014; Fögele, Citation2016) that may be more sensitive to other factors, such as societal challenges or involved stakeholders’ personal beliefs than expert knowledge. It requires further examination whether the renegotiated disciplinarity leads to a geographical knowledge that offers students the best available knowledge scholarship that academic geography has to offer. Given the urgency to contribute to ESD and the need to process rapidly emerging findings about our changing world, geographical knowledge conceptualized in the way of the German Standards (DGfG, 32014) and its redefinition (Fögele, Citation2016) limits the school subject’s contribution to a more sustainable future.

(2) What is the place of Physical geography in geographical knowledge? Exploring this question links back to Dufour’s (Citation2015) call for a critical physical geography that renegotiates its role within an integrative geography (Castree, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2014c). While such debates from academic geography are undoubtedly important for the school subject, given its own epistemology, geographical knowledge in schools always follows partly normatively set aims. A range of documents claim, and concurrently, prescribe the exploration of human-environment interaction as the core of geographical knowledge. Nevertheless, particularly some competencies-based curricula tend to reduce physical geography, initially expected to deliver the science component to the human-environment rhetoric, to a means to develop generic skills, such as collecting, analyzing, and representing data (Bagoly-Simó & Uhlenwinkel, Citation2016). However, under such circumstances, physical geography will not deliver its expected contribution as the science component of geographical knowledge. Therefore, a renegotiation of the potentials and limitations of physical geography’s contribution to knowledge seems past due.

Such an endeavor appears even more urgent in light of geography’s claimed contribution to ESD. On the one hand, particularly in light of ESD’s innate normativity, Haubrich’s (Citation1994) Gaia meditation incorporating Härle’s (Citation1980) call for a more green mindset, materializes in discourses that emphasize morals and values (Ballantyne, Citation1999; Rolston, Citation2002; Al-Naki, Citation2004; Haubrich, Citation2009; Applis, Citation2015, Citation2016; Applis & Fögele, Citation2016). On the other hand, Jannsen’s (Citation1982) call for a rational and critical physical geography that presents evidence for individuals to use them in democratic processes as part of robust citizenship (Bagoly-Simó & Uhlenwinkel, Citation2016). It opens up ways to equip students with the required knowledge to take action within democratic processes and include debates within the field of ESD-related ethics and morals.

(3) What kind of geographical knowledge best supports ESD? Geography curricula around the globe choose different ways to define geographical knowledge (Bagoly-Simó, Citation2021). Still, geography’s claim to make the most adequate contribution to ESD requires further work in at least four areas.

First, along with the human-environment interaction or system, academic scholarship in geography offers alternative models to contribute to a more sustainable future. Therefore, careful consideration of deep, expert knowledge is required to uncover such alternatives to the established human-environment rhetoric. Concerning this aspect, a more substantial involvement of academic geography in a future reconfiguration of geography’s disciplinarity seems desirable.

Second, if school geography was to maintain the traditional physical-human divide, the systemic approach requires revision. The German Standards (DGfG, 32014) that inspired a range of curricula across the world (e.g. Belgium, Mongolia) entail a systemic perspective in need of an update. Naturally, other conceptualizations of interactions between societies and environments could be possible routes to explore, should this artificial division across the traditional physical-human divide remain relevant for the school subject. For example, the Austrian curriculum offers an interesting alternative focusing on humans as (economic) agents in space. Regardless of the route taken, the inclusion of contemporary human-geographical perspectives, such as space as perception and space as construct (Wardenga, Citation2002) in the German tradition, seem necessary.

Third, geography’s key or basic concepts need to carry the potential to equip students with the geographical knowledge required to work on solutions for a (more sustainable) future. While the Mexican model () incorporates different possibilities to think about SD, sustainability in the German curricula offers basic concepts () that rather impoverishes the geographical knowledge students’ encounter in school geography. Alternatively, stakeholders developing geography curricula and, thus, initiating shifts in the subject’s disciplinarity might reflect on SD as a combination of key concepts, ESD-topics, and (cross-curricular) objectives.

Fourth, returning to Jannsen’s (Citation1982) proposal, geography needs a critical and rational physical geography delivering evidence for individuals participating in democratic processes with the aim of constructing and maintaining a robust citizenship. Consequently, along these lines, taking a closer look at the value of knowledge originating from human geography—which, for the most part, remained uncontested over time—seems reasonable. ESD heavily relies on values and morals. However, negotiation and participation are at their core (de Haan, Citation2008). Therefore, normatively imprinted values and morals as part of the geographical knowledge or citizenship education counteracts ESD’s main objectives. Consequently, increasing the normativity by redesigning the curriculum’s geographical knowledge hinders emancipation and transformation in terms of ESD.

Re(definitions) of geographical knowledge in light of cross-curricular objectives—often reflecting grand societal challenges—require the rich theoretical framework disciplinarity offers. This article only focused on three selected aspects of school geography in a particular setting (Germany). In doing so, it constitutes a first attempt to contribute to the debate on geographical knowledge by bringing it back into subject education.

6. Concluding thoughts

While discussing the role of geographical and environmental education in the 1990s, John Lidstone remembered students leaving classrooms defeated and feeling helpless when confronted with the world’s grand challenges. Three decades later, the situation has hardly changed. Greta Thunberg’s anger carries the same message as Severn Cullis-Suzuki’s carefully crafted and well-argued speech during the 1992 Earth Summit.

Much like humanity, geography survived in most countries around the globe. Similar to the 1990s (cf. Haubrich, Citation1992), geography educators continue to stress geography’s unique contribution to ESD and, clearly, to a more sustainable future. While many countries incorporated geography into social studies or other new subjects and other countries drastically reduced the weekly hours dedicated to geography as an independent school subject, its failure to live up to its repeatedly declared contribution first to EE and subsequently to ESD also has internal reasons. There is no better time than the present to critically re-evaluate geography’s contribution and work on a doable and honest agenda to contribute to the current grand challenges that humanity faces.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Al-Naki, K. (2004). How do we communicate environmental ethics? Reflections on Environmental Education from a Kuwaiti perspective. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 13(2), 128–142.

- Applis, S. (2015). Analysis of possibilities of discussing questions of global justice in geography classes. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 24(3), 273–285.

- Applis, S. (2016). Research on the challenges of introducing the dilemma discussion for the support of judgment competence in the geography classroom. Research in Geographic Education, 18(1), 25–40.

- Applis, S., & Fögele, J. (2016). Development of geography teachers capacity to evaluate—Analysis on coping with complexity and controversiality. Research in Geographic Education, 18(1), 10–24.

- Bagoly-Simó, P. (2013). Tracing sustainability: An international comparison of ESD implementation into lower secondary education. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 7(1), 95–112.

- Bagoly-Simó, P. (2014). Tracing sustainability: Concepts of sustainable development and Education for Sustainable Development in lower secondary geography curricula of international selection. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 23(2), 126–141.

- Bagoly-Simó, P. (2021). What does that have to do with geology? The Anthropocene in school geographies around the world. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(3), 944–957.

- Bagoly-Simó, P. (2022, accepted). Geographisches Fachwissen unter dem Zeichen der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung im postsozialistischen Berlin [Geographical Knowledge under Education for Sustainable Development in Post-Socialist Berlin].

- Bagoly-Simó, P. (accepted) El conocimiento geográfico en los tiempos de la educación basada en competencias. Retos de las perspectivas teóricas provenientes de la sociología de la educación y de la didáctica de la geografía [Geographical knowledge in competencies-based education. Tales of theoretical input from the sociology of education and geography education]. Didáctica Geográfica.

- Bagoly-Simó, P., & Hartmann, J. (2021). Are we sustainable yet? Results of a longitudinal curriculum study by means of topic-based indicators. Zeitschrift für Geographiedidaktik | Journal of Geography Education (ZGD) 49(3), 130–148.

- Bagoly-Simó, P., & Uhlenwinkel, A. (2016). Why physical geography? An analysis of justifications in teacher magazines in Germany. Nordidactica. Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 2016(1), 23–27.

- Bagoly-Simó, P., Hartmann, J., & Reinke, V. (2020). School geography under COVID-19: Geographical knowledge in the German formal education. Tijdschrift poor economische en Sociale geografie. Journal of Economic and Social Geography, 113(3), 224–238.

- Ballantyne, R. (1999). Teaching environmental concepts, attitudes and behaviour through geography education: Findings of an international survey. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 8(1), 40–58.

- Boehm, R., Solem, M., & Zadrozny, J. (2018). The rise of powerful geography. The Social Studies, 109(2), 125–135.

- Brooks, C. (2018). Understanding conceptual development in school geography. In M. Jones & D. Lambert (Eds.), Debates in geography education (pp. 103–114). London & New York, NY: Routledge.

- Caruso, M., & Reh, S. (2021). Unterricht. In G. Kluchert, K.-P. Horn, C. Groppe & M. Caruso (Eds.), Historische Bildungsforschung. Konzepte—Methoden—Forschungsfelder (Historical Educational Research. Concepts–Methods–Research Fields) (pp. 255–266). Stuttgart: Klinkhardt.

- Castree, N. (2014a). The Anthropocene and geography I: The back story. Geography Compass, 8(7), 436–449.

- Castree, N. (2014b). Geography and the anthropocene II: Current contributions. Geography Compass, 8(7), 450–463.

- Castree, N. (2014c). The anthropocene and geography III: Future directions. Geography Compass, 8(7), 464–476.

- Clifford, N. J., Holloway, S. L., Rice, S. P., & Valentine, G. (Eds.) (2009). Key concepts in geography. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage.

- Dantas Barbosa, A. F. (2006). O conhecimento tácito substantivo histórico sobre o encontro entre povos e culturas na época dos descobrimentos: um estudo com alunos dos 7o e 10o anos de escolaridade [Historical substantive tacit knowledge about the encounter between peoples and cultures at the time of the discoveries: A study with seventh- and tenth-grade students]. Universidade do Minho.

- de Haan, G. (2008). Gestaltungskompetenz als Kompetenzkonzept für Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung [Gestaltungskompetenz as concept of competencies for the education for sustainable development]. In I. Bormann & G. de Haan (Eds.), Kompetenzen der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Operationalisierung, Messung, Rahmenbedingungen, Befunde [Comptencies of Education for Sustainable Development. Operationalization, Measurement, Frameworks, Findings] (pp. 23–43). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Deng, Z. (2022). Powerful knowledge, educational potential and knowledge-rich curriculum: Pushing the boundaries. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(5), 599–617.

- DGfG (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geographie). (32014). Educational standards in geography for the Intermediate School Certificate with sample assignments. Berlin: DGfG.

- do Céu Roldão, M. (2013). Kompetenzen: Unterstützung von Unterrichtsplanung und Leistungsbewertung [Competencies: Supporting lesson planning and assessment]. In M. Rolfes & A. Uhlenwinkel (Eds.), Metzler Handbuch 2.0 Geographieunterricht. Ein Leitfaden für Praxis und Ausbildung (pp. 96–104). Braunschweig: Westermann.

- Dufour, S. (2015). Sur la proposition d’une géographie physique critique [On the position of a critical physical geography]. L’information géographique, 79, 8–16.

- Fögele, J. (2016). Entwicklung basiskonzeptionellen Verständnisses in geographischen Lehrerfortbildungen: Rekonstruktive Typenbildung | Relationale Prozessanalyse | Responsive Evaluation. Geographiedidaktische Forschungen, vol. 61. Münster: Monsenstein und Vannerdat.

- Härle, J. (1980). Das geoökologische Defizit der Schulgeographie [The geo-ecological deficit of school geography]. Geographische Rundschau, 32, 481–487.

- Haubrich, H. (1992). International Charter on Geographical Education. Nuremberg: HGD.

- Haubrich, H. (1994). Globale Aspekte der geographischen Erziehung [Geography education’s global aspects]. In M. Flath & G. Fuchs (Eds.), Die Erde bewahren—Fremdartigkeit verstehen und respektieren (pp. 52–63). Weingarten: Klett.

- Haubrich, H. (2009). Global leadership and global responsibility for geographical education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 18(2), 79–81.

- Haubrich, H., Reinfried, S., & Schleicher, Y. (2007). Lucerne declaration on geographical education for sustainable development. In S. Reinfried, Y. Schleicher & A. Rempfler (Eds.), Geographical Views on Education for Sustainable Development (pp. 243–250). Weingarten: HGD.

- IGU-CGE. (2016). 2016 International Charter on geographical education. IGU-CGE.

- Jannsen, G. (1982). Die Rettung der physischen Erdkunde durch die politische Bildung [The rescuing of physical geography through civics]. Helsinki: GHM.

- Lambert, D. (2017). Powerful disciplinary knowledge and curriculum futures. In N. Pyyry, L. Tainio, K. Juuti, R. Vasquez & M. Paananen (Eds.), Changing subjects, changing pedagogies: Diversities in school and education (pp. 14–31). Helsinki: Finnish Research Association for Subject Didactics.

- Lethmate, J. (2000a). Das geoökologische Defizit der Geographiedidaktik [The geo-ecological deficit of geography education]. Geographische Rundschau, 52, 34–40.

- Lethmate, J. (2000b). Ökologie gehört zur Erdkunde—aber welche? Kritik geographiedidaktischer Ökologien [Ecology belongs to Geography—but which one? Critcism of the ecologies of geography education]. Die Erde, 131, 61–79.

- Lethmate, J. (2001). Ökologie und Erdkunde: Geographiedidaktische Selbstillusionierungen [Ecology and Geography: Self-illusions of geography education]. Geographie und Schule, 23, 37–43.

- Maude, A. (2016). What might powerful geographical knowledge look like? Geography, 101(2), 70–76.

- Maude, A. (2018). Geography and powerful knowledge: A contribution to the debate. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 27(2), 179–190.

- Maude, A. (2020). The role of geography’s concepts and powerful knowledge in a future 3 curriculum. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 29(3), 232–243.

- Maude, A. (2022). Using geography’s conceptual ways of thinking to teach about sustainable development. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 1–16.

- McKeown, R., & Hopkins, C. (2007). Moving beyond the EE and ESD disciplinary debate in formal education. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 1(1), 17–26.

- Morgan, J., Hordern, J., & Hoadley, U. (2019). On the politics and ambition of the ‘turn’: Unpacking the relations between Future 1 and Future 3. The Curriculum Journal, 30(2), 105–124.

- Öhman, J. (2004). Moral perspectives in selective traditions of environmental education : Conditions for environmental moral meaning-making and students’ constitution as democratic citizens. In P. Wickenberg, H. Axelsson, L. Fritzén, G. Helldén & J. Öhman (Eds.), Learning to change our world? Swedish research on education & sustainable development (pp. 33–57 Stockholm: Studentlitteratur.

- Östman, L. (2010). Education for sustainable development and normativity: A transactional analysis of moral meaning‐making and companion meanings in classroom communication. Environmental Education Research, 16(1), 75–93.

- Popper, K. (1992). Ausgangspunkte. Meine intellektuelle Entwicklung [Starting points. My intellectual development]. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe.

- Reh, S. (2018). Fachlichkeit, Thematisierungszwang, Interaktionsrituale. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 64(1), 61–70.

- Rolston, H. (2002). Enforcing environmental ethics: civic law and natural value. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 11(1), 76–79.

- Schiele, S., & Schneider, H. (Eds.) (1987). Konsens und Dissens in der politischen Bildung [Consensus and Dissensus in Civics Education]. Stuttgart: Metzler.

- Schöps, A. (2017). The paper implementation of the German educational standards in geography for the intermediate school certificate in the German federal states. Review of International Geographical Education Online RIGEO, 7(1), 94–117.

- Schultz, H.-D. (1996). Didaktische Petitessen zum Mensch-Umwelt-Problem im Kontext des geographischen Selbstverständnisses. Ein Plädoyer für geographische Bescheidenheit [Didactical Petitesse concerning the human-environment problem of the geographical self-perception]. Zeitschrift für den Erdkundeunterricht, 48, 42–47.

- Schultz, H.-D. (1997). Mit oder gegen die Natur? Die Natur ist, was sie ist, und sonst gar nichts [With or against the nature? The nature is what it is and nothing more]. Zeitschrift für den Erdkundeunterricht, 49, 296–302.

- Schultz, H.-D. (1999). „Inwertsetzung“, „Bewahrung “oder „erdgerechtes Verhalten“? Zur Leitbilddiskussion in der Geographiedidaktik [“Enhancement”, “Protection”, or “Earth-worthy behavior”? On the margins on the debate of geography education’s mission statement]. In W.-D. Schmidt-Wulffen & W. Schramke (Eds.), Zukunftsfähiger Erdkundeunterricht. Trittsteine für Unterricht und Ausbildung (pp. 181–191). Stuttgart: Klett.

- SEP (Secretaría de Educación Pública. (2011). Programas de studio 2011/Guía para el Maestro Secundaria/Geografía de México y del Mundo [Curriculum 2011/Teachers’ guide/Secondary education/Geography of Mexico and the world]. México D.F.: SEP.

- Uhlenwinkel, A. (2017). Enabling educators to teach and understand capabilities: The example of “Young People on the Global Stage”: Their education and influence. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 26(1), 3–16.

- Uhlenwinkel, A., Béneker, T., Bladh, G., Tani, S., & Lambert, D. (2017). GeoCapabilities and curriculum leadership: Balancing the priorities of aim-based and knowledge-led curriculum thinking in schools. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 26(4), 327–341.

- Wardenga, U. (2002). Alte und neue Raumkonzepte für den Geographieunterricht [Old and new space concepts for geography lessons]. Geographie Heute, 200, 8–11.

- Wilhelmi, V. (2014). Physische Geographie im Unterricht—handlungs—und prozessorientiert [Physical geography in the classroom–oriented towards action and process]. Praxis Geographie, 44, 4–7.

- Young, M., & Muller, J. (2010). Three educational scenarios for the future: Lessons from the sociology of knowledge. European Journal of Education, 45(1), 11–27.