Abstract

Phenomenon: China is a relatively homogenous nation where the majority of people are Han Chinese. In recent years, a large number of international students have begun to study medicine in China. Due to the privacy and intimacy associated with obstetrical and gynecological diseases, Chinese women’s acceptance toward international students’ involvement in their care has not been reported thus far. This survey aims (1) to determine Chinese women’s attitudes toward both Chinese and international medical student involvements in obstetrical and gynecological outpatient departments and (2) to investigate possible reasons, if any, for their rejection of the medical students. Approach: We conducted a cross-sectional survey study using a locally-developed questionnaire. The survey was conducted in the obstetrical and gynecological outpatient department of a tertiary hospital in a Chinese harbor city. We surveyed 600 patients for their attitudes towards the involvement of four groups of medical student in clinical practice: Chinese female, International female, Chinese male, and International male. Among the returned questionnaires, 501 satisfied the criteria for analysis. Findings: Patient’s acceptance rates of the four groups of students (Chinese female, International female, Chinese male, and International male) were 59.7%, 55.9%, 32.1%, and 25.9%, respectively. Analysis revealed that language barriers and lack of friendliness were the two main reasons leading to patients’ low acceptance rates of international students. Insights: Obstetrical and gynecological patients are more likely to accept female students over male students, regardless of their nationality, however International male students receive the least acceptance. For international students, improving their Chinese language skills and using more friendly expressions may facilitate their practice in China.

Introduction

Patient contact is crucial for medical students’ development of clinical skills. Due to the privacy and intimacy of physical examinations carried out in obstetrical and gynecological (Ob/Gyn) departments, the difficulties that medical students encounter while dealing with this aspect of their duties have been reported all over the world.Citation1–4 Although China has 56 ethnic groups, the majority of population comprises Hans. In this respect, China is a relatively homogeneous nation, and it has always been deeply influenced by Confucian culture. Starting from the Han period, about 2000 years ago, Confucians in China began to teach ancient Chinese women to follow their father before marriage, the husband after marriage, and her sons in widowhood. This traditional culture later placed more emphasis on the virtue of chastity. A famous Confucian in the Song dynasty (circa 1000 years ago) stated that: “To starve to death is a small matter, but to lose one’s chastity is a great matter.” Another Prominent Song Confucian scholar, Zhu Xi, believed that “Men and women need to be kept strictly separate, and women should remain indoors and not deal with the matters of men in the outside world.” This traditional culture might be one of the reasons for Chinese patients’ rather low acceptance toward medical student involvement in Ob/Gyn clinics. A survey conducted in Singapore, where social environment, culture, and demographic composition are quite similar to China’s, revealed that, compared to their Malay and Indian counterparts, female patients of Chinese ethnicity generally showed the lowest “comfort” scores when interviewed and examined by medical students.Citation5 However, this kind of data has never been reported in China.

China is now one of the world’s fastest growing destinations for international medical students. At last count, Chinese medical schools were authorized by the government to accept more than 6000 international medical students annually from 150 countries.Citation6 By the end of 2016, the number of international students enrolled at Dalian Medical University alone had reached more than 1300;Citation7 this is one of the highest numbers for medical schools all over China.Citation8 The majority of these students come from African (South Africa, Ghana, Tanzania, Mauritius, etc.) and South Asian (India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, etc.) countries. The appearance, customs, and languages of these students are very different from those of Chinese nationals.

As mentioned before, China is a relatively ethnically homogenous nation that has long been influenced by Confucian teachings. Before the year 2000, there were very few international students completing their internships at Chinese university hospitals. In light of this, we clinical teachers assumed that international medical students may have a higher likelihood of being rejected by Chinese female patients, especially in Ob/Gyn settings. However, a recent survey comparing the attitudes of patients and doctors towards medical student involvement in Ob/Gyn departments indicated that providers may underestimate patient acceptance, therefore unnecessarily limiting student exposure to clinical learning opportunities.Citation9 This conclusion seems supportive of patients’ acceptance of medical students. Yet there also is negative evidence; another Chinese medical school has reported that their international students’ average scores in Ob/Gyn examinations were significantly lower than those of Chinese students.Citation10 This report suggests that international medical students’ low scores in Ob/Gyn exams may be due, at least in part, to limited practice opportunities. For these reasons, the actual status of international internships in China urgently needed investigation.

To explore this matter, we conducted a survey in our Ob/Gyn department. Our aim was to (1) assess the preliminary attitudes of Chinese patients toward native and international student involvement in their care; (2) identify reasons that support acceptance or lead to refusal; and (3) determine the patient characteristics that contribute to increased acceptance of medical student involvement.

Method

Setting

Fifth-year medical students (“interns”) at Dalian Medical University, both native and international, must complete clinical rotations in Internal Medicine, Surgery, Ob/Gyn, and Pediatrics. In Ob/Gyn, the rotation lasts six weeks, of which two weeks are spent in the outpatient department. There are three Chinese and two international students on each rotation. In the outpatient department, students are expected to learn medical history taking, genital and pelvic examinations, and obstetrical examinations (including Leopold Maneuvers). All hands-on practice of these skills occurs under the guidance of a qualified doctor after the patient’s permission has been obtained. It is important to develop these skills in the outpatient department. Although patients seen on the inpatient rotation are more likely to accept students’ participation in their care, most of the cases are surgical. Clinical learning in this setting does not cover the whole disease spectrum, and the practice is of insufficient breadth. Upon completion of training, students are expected to have mastered the diagnosis and treatment of Ob/Gyn diseases commonly encountered in the outpatient setting. At rotation’s end, the Ob/Gyn exam comprises two parts: written and practical. The former, written exam mainly tests the knowledge about Ob/Gyn subject matter. The latter, practice exam is performed on mannequins to evaluate students’ mastery of basic Ob/Gyn clinical skills.

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of Ob/Gyn patients in our outpatient department. Copies of the questionnaire were distributed to patients in person after obtaining their written consent. For those patients who could not read, we performed face-to-face interviews in order to record their answers. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Record No. YJ-KY-FB-2016-01).

Study population

Patients were recruited through simple random sampling based on registration numbers. Every day for 20 consecutive workdays, two medical student research assistants distributed 30 copies of the questionnaire to patients after their doctor’s visit. One research assistant was Chinese, and the other was international. Using Bartlett et al.’s formula for categorical data,Citation11 the sample size was estimated to be 623 based on a population size of 10,000 (on average, there were 8000-9000 visits to this outpatient department every month), a p-value 0.01 at t = 2.58, and a margin of error at 0.05. This sample size was in accordance with the sample sizes used in previous similar studies conducted elsewhere.Citation2,Citation12,Citation13 In total, 600 copies of the questionnaire were distributed. Five hundred and forty-three copies were collected. Within these 543 copies, 42 were excluded due to non-response to some key items. Consequently, 501 copies were deemed eligible for analysis, and the final response rate was 84%.

Questionnaire design and study variables

A questionnaire was developed based on literature reviewCitation1–5 and modified according to specific conditions in China. The first part consisted of patients’ background information, namely age, occupation, education level, whether they had a child, marital status, overseas experience, medical background, chief complaints during that particular visit, and previous awareness of students’ presence (i.e., awareness that the hospital is a teaching center). Next, respondents were asked about their attitudes toward students and the possible reasons for their acceptance or refusal of student involvement in the whole clinic process, including history taking and intimate/pelvic examination. As there were different acceptance rates for male and female medical students in previous studies,Citation1,Citation14–18 this part was designed to ask patients about their attitudes toward involving four specific groups of medical students in consultations and pelvic or obstetrical examinations: Chinese female (CF), International female (IF), Chinese male (CM), and International male (IM). They were asked to rate their acceptance level on a 5-point ordinal scale (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = disagree, and 5 = strongly disagree). The third part of the survey listed several possible reasons for why patients accepted or refused a medical student. The questionnaire was tested in a small-scale population setting (50 patients). The translated questionnaire can be found in the supplemental materials.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square was used to compare differences in acceptance rates between native and international students according to gender. Specifically, we examined the acceptance rate of international male students as compared to Chinese male students, but not Chinese or international female students. Stratified by the sociodemographic characteristics, we used the Chi-square to explore possible factors that could affect patients’ acceptance of student involvement. Multiple ordinal regression analysis then was used to investigate and distinguish the factors that could contribute toward increasing acceptance. Generally, a p-value <0.05 is considered as being significant, but for stratified Chi-square tests, a p-value <0.1 was accepted for the subsequent multiple-factor tests. Analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 13, SPSS Inc., Chicago).

Results

Demographic characteristics

summarizes the sociodemographic information of the 501 participants. The median age was 31.5 years. Most participants were married with a college degree and had professional careers. Half of them had children and had friends or relatives with medical background. Only 15% of them had been abroad. Nearly 80% of their visits to the hospital were for gynecologic problems. About half of participants knew that Chinese medical students may be present in the hospital before their visits, but only 30% of them knew that foreign students may be present.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of questionnaire respondents (N = 501).

Patients’ attitudes

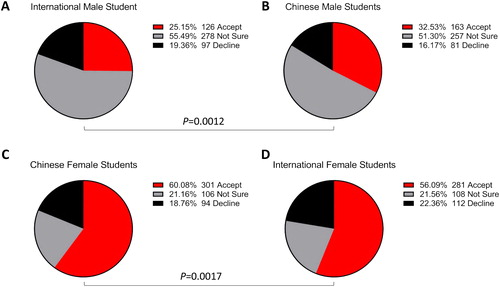

shows patients’ attitudes toward different medical student involvement in the Ob/Gyn outpatient department. To facilitate analysis, we integrated choices such as “I accept” and “I reluctantly accept” into one item as “accept.” Similarly, the two choices “I usually don’t accept” and “definitely refuse” were integrated as “refuse,” while the choice “not sure” was unchanged. For Chinese female students, patients’ acceptance rate was 60%, slightly higher than that of international female students (56%), and this difference was significant [X2(4) = 315.298, p = .000]. Among the four student types, international male students had the highest likelihood of being rejected; their acceptance rate was 25%. Chinese males had a higher acceptance rate at 33% [X2(4) = 403.423, p = .000].

Possible reasons for patients’ acceptance and refusal

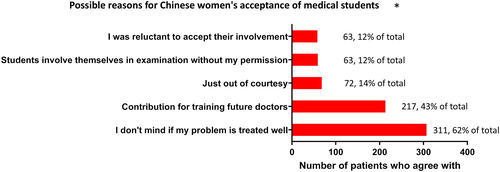

shows reasons for Chinese women’s acceptance of medical students. Three hundred and eleven participants (62%) agreed with the statement I don’t mind student involvement as long as my problem is treated well. Nearly 43% (N = 217) felt that allowing medical students’ involvement is a contribution toward molding future doctors. The other reasons that followed included accepting student involvement out of courtesy (N = 72, 14%), students usually involved themselves in my treatment without permission (N = 63, 12%) and I feel awkward rejecting my doctor if he/she asks for my permission (N = 62, 12%).

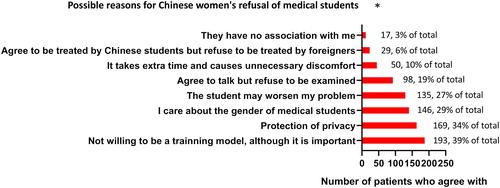

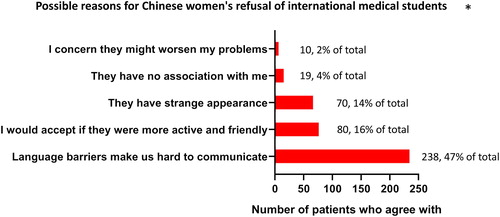

Among the reasons for Chinese women’s refusal of medical students (), the most common response was not willing to be a training model (N = 193, 39%). Thirty-four percent of respondents (N = 169) stated that they would refuse, as they were concerned about their privacy. Among the reasons for refusing international students specifically (), language barrier was the prime one (N = 238, 47%). It also seemed that behaving in a friendlier manner toward patients helped to improve their acceptance rate (N = 80, 16%).

Factors promoting acceptance

shows that patients who were aware of students’ presence in the hospital before their visits were more likely to accept medical student involvement, regardless of the student’s gender or nationality [X2(2) = 9.817–23.907, p < .01 for all four groups of students]. Women who had children and women older than 50 were more likely to accept Chinese male students’ involvement [X2(4) = 9.171–16.314, p < .05 for all three groups of students], but this inclination did not extend to international male students. With a liberal p value of 0.1, occupation, education level, chief complaints, and overseas experience all seemed to have some association with patients’ acceptance.

Table 2. Factors affecting patients’ acceptance of medical students’ involvement.

Ordinal regressions

We considered that there might have been interactions and confounding relations among the factors significantly (p < 0.1) associated with acceptance in the above-mentioned univariate analyses. We therefore tested these factors using ordinal regression. We defined the attitude of the patients as a dependent variable (1 =refuse, 2 =uncertain, 3 = accept) and used predictive factors in the univariate analysis (shown in ) as independent variables. For Chinese female students, the independent variables were “Chief complaint” and “Previous awareness of Chinese students.” For Chinese male students, these were “Age,” “Education level,” “Whether one had a child,” “Overseas experience,” “Chief complaint,” and “Previous awareness of Chinese students.” For International male students, these were “Occupation,” “Chief complaint,” and “Previous awareness of international students.” The multivariate analysis showed that, except for International female students, patients’ previous awareness of students’ presence in the hospital was the only independent factor that could affect patients’ acceptance toward medical students ().

Table 3. Multivariate ordinal regression analysis of factors affecting patients’ acceptance of medical student involvement.

Discussion

In this study, we found that female Chinese patients’ acceptance rates of four types of medical student in their OB/GYN care (Chinese female, International female, Chinese male, and International male) was 60%, 56%, 33%, and 25%, respectively. Furthermore, using multiple ordinal regression, we determined that patients who were aware of medical students’ presence in the hospital tended to be more accepting of student involvement regardless of the student’s nationality and/or gender. Another finding was that language barriers were the primary reason for most patients’ rejection of foreign students, and 16% of women thought that their attitude could have changed if the international students had adopted a friendlier manner.

Patient acceptance rates reported in this study agreed with our expectations—chiefly, that female students would have a higher likelihood of being accepted than male ones. Chinese female students were more likely to receive acceptance from patients than their international counterparts, however the absolute difference was marginal (four percentage points). For males, Chinese students had a mere six percentage point advantage over their foreign counterparts (32% vs. 26%).

Comparing these results with previous studies from western countries,Citation1,Citation12,Citation13,Citation15,Citation19–22 Chinese women’s acceptance toward student involvement was lowest and varied largely depending on student gender. This tendency could be partly attributed to traditional Confucian cultural norms that have long influenced Chinese society. Evidence supporting this suggestion is the predominance of female Ob/Gyn doctors in China; an official documentary in 2013 showed that 74.2% of Ob/Gyn doctors in China were female. Intriguingly, even in some Muslim countries, such as the United Arab Emirates (the UAE),Citation2 Syria,Citation23 and Pakistan,Citation4 where cultural or religious norms may be considered even more conservative than China’s, patients’ acceptance rates (87%, 68%, and 83%, respectively) were all somewhat higher than those of Chinese women.

Although our survey was conducted in the medical field, these results are consistent with a recent survey about Chinese’s attitudes towards foreign migration outside medical care. When foreign migrants have high professional skills, they are more supported even than internal Chinese migrants. However, if foreign migrants are low-skilled, Chinese people show more opposition to foreigners than internal migrants.Citation24 International medical students, whose professional skills are still developing, are usually taken as low-skilled people and may receive less acceptance.

Another possible reason for these results is that, in the previously mentioned studies, there were some variations in the definitions of the term “involvement” with regard to medical students. As involvement or participation includes “observation,” “medical history taking,” and “physical examination,” different understandings and definitions of this word will produce different results. Thurman,Citation20 Ching,Citation15 and HartzCitation1 defined consent toward student training involving either observation, medical history taking, or examination and obtained acceptance rates for each activity as 76%, 81%, and 78%, respectively. However, investigations of patients’ attitudes toward intimate examinations produced different results. In Britain, O’Flynn et al. were the first to report that 40% of patients accepted both male and female students.Citation25 In the United States, Mavis et al. found that only 31% of patients received pelvic exams from students of both genders.Citation3 Another survey in the UAE showed that 79% of women accepted intimate examinations from female students, but for male students, the acceptance rate was only 4%.Citation26 A recent study in Kuwait found that, although 72.3% of patients allowed students to take a medical history, only 31% of patients accepted a pelvic examination even from female students.Citation27

Our experience in China showed that patients seldom refused students who were taking their medical history. The activities they were most concerned about, however, were intimate examinations, especially when male students were present. Therefore, in this preliminary study, we defined the term “involvement” as providing consent for medical history taking and pelvic or obstetrical examinations. However, as our response rate was not perfect (84%), the patient acceptance rates may not be fully indicative of their real acceptance rates. It is possible that the 16% of people who did not respond would have been more likely to reject students, so the real acceptance rate may be even lower. Additionally, our data were consistent with data from a survey in Singapore, which showed that 65% of Asian patients (67% of whom were Chinese) would accept physical examinations performed by medical students; however, that study was conducted in several different departments in a general hospital.Citation5

As mentioned previously, patients who were aware of medical students’ presence tended to have more accepting attitudes toward students regardless of their nationality and/or gender. This was also consistent with the results of other studies indicating that both previous encounters with and awareness of medical students are factors that can contribute toward increasing patients’ acceptance rates.Citation2–5,Citation27,Citation28 The factors that contributed toward increased acceptance or refusal rates for students in our survey were also similar to those identified in previous research studies.Citation1,Citation2,Citation25,Citation29

We also found that the language barrier was many patients’ primary reason for refusing foreign students, and 16% of women thought that international students should be friendlier if they wanted to get practice opportunities. One report suggests that interactive theater can be used to increase preceptors’ comfort with discussing medical student involvement with patients, however normal communication in doctors’ and patients’ native language is a prerequisite of this activity.Citation30 Thus, medical university administrators should consider improving their international students’ Chinese and provide them with training in interpersonal skills.

The main strength of our study is that it might be the first attempt to investigate patients’ attitudes toward Chinese and international medical students in the Ob/Gyn department. As the number of international students seeking medical education in China continues to increase, these findings may prove to be extremely useful for physicians, administrators, and potential international medical students planning to study in China. In addition, we found an independent factor (patients’ awareness of students’ presence) that could affect patients’ acceptance rates. With regard to international students, the study identified two major reasons for their high rejection rates. Finally, as migration is a globally relevant issue, this investigation opens the door for doctors all over the world to examining more widely how native status affects immigrants’ training and integration into the medical profession.

As a preliminary study in this field, this study also has several limitations. First, because little was known thus far about the acceptance rates of Chinese patients, we cannot calculate the effective sample size for every step of the comparison, and this might impair the statistical power of the findings. Second, this survey was conducted at a single tertiary-level teaching hospital in Dalian, a large port city in Northeast China. Thus, these results may not be completely generalizable to the whole country.

Conclusions

The order of Chinese women’s acceptance rates with regard to different medical students (from highest to lowest) was as follows: Chinese females, International females, Chinese males, and International males. Enhancing ways to provide patients with information regarding the presence of medical students in university hospitals in China could be considered as a way to improve Ob/Gyn patients’ acceptance of medical students’ involvement in their care. This information can be integrated into an introduction for patients seeking care in large teaching hospitals. Furthermore, international students may be able to obtain more opportunities in their internships if they work on improving their Chinese language and interpersonal skills. The medical schools in China that enroll international students could place more emphasis on Chinese language courses relative to biomedical courses. This study could help to identify poor Ob/Gyn clinical skill acquisition among male students (especially international male students) and could thus be valuable for young men who wish to study medicine in China in the future.

Additional information

Funding

Reference

- Hartz MB, Beal JR. Patients' attitudes and comfort levels regarding medical students' involvement in obstetrics-gynecology outpatient clinics. Acad Med. 2000;75(10):1010–1014. doi:10.1097/00001888-200010000-00018.

- Rizk DE, Al-Shebah A, El-Zubeir MA, et al. Women's perceptions of and experiences with medical student involvement in outpatient obstetric and gynecologic care in the United Arab Emirates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):1091–1100.

- Mavis B, Vasilenko P, Schnuth R, et al. Medical students' involvement in outpatient clinical encounters: a survey of patients and their obstetricians-gynecologists. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):290–296. doi:10.1097/00001888-200603000-00023.

- Saeed F, Kassi M, Ayub S, et al. Factors influencing medical student participation in an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57(10):495–498.

- Koh GC, Wong TY, Cheong SK, et al. Acceptability of medical students by patients from private and public family practices and specialist outpatient clinics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39(7):555–510.

- Ministry of Education PsRoC. The MBBS Program for international students in 2013-2014. 2013. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A20/moe_850/201303/t20130312_149249.html. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- University DM. About DMU, 2010. http://home.dlmedu.edu.cn/IEC/en/1.aspx?id=123. Accessed June 9, 2014

- China MoEotPsRo. List of institutions and scale of enrollment for undergraduate clinical medicine programs taught in English for international students, 2010/2011, 2010. http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_2804/201008/96956.html.

- Coppola LM, Reed KL, Herbert WN. Comparison of patient attitudes and provider perceptions regarding medical student involvement in obstetric/gynecologic care. Teach Learn Med. 2014; 26(3):239–243. doi:10.1080/10401334.2014.910125.

- Luo HJ, Li Q, Xu JP. Gynemetrics result analysis of domestic and overseas medical undergraduates. Res Med Educ. 2010;9(11):1489–1492. (In Chinese)

- James E, Bartlett I. Organizational research: determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inform Technol Learn Perform J. 2001;19(1):43–50.

- Grasby D, Quinlivan JA. Attitudes of patients towards the involvement of medical students in their intrapartum obstetric care. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41(1):91–96. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828x.2001.tb01302.x.

- Carmody D, Tregonning A, Nathan E, et al. Patient perceptions of medical students' involvement in their obstetrics and gynaecology health care. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51(6):553–558.

- Magrane D, Gannon J, Miller CT. Obstetric patients who select and those who refuse medical students' participation in their care. Acad Med. 1994;69(12):1004–1006. doi:10.1097/00001888-199412000-00023.

- Ching SL, Gates EA, Robertson PA. Factors influencing obstetric and gynecologic patients' decisions toward medical student involvement in the outpatient setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(6):1429–1432. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.106133.

- Chang JC, Odrobina MR, McIntyre-Seltman K. The effect of student gender on the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship experience. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(1):87–92. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1357.

- Akkad A, Bonas S, Stark P. Gender differences in final year medical students' experience of teaching of intimate examinations: a questionnaire study. BJOG. 2008;115(5):625–632. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01671.x.

- Craig LB, Smith C, Crow SM, et al. Obstetrics and gynecology clerkship for males and females: similar curriculum, different outcomes?. Med Educ Online. 2013;18(1):21506. doi:10.3402/meo.v18i0.21506.

- Shann S, Wilson JD. Patients' attitudes to the presence of medical students in a genitourinary medicine clinic: a cross sectional survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(1):52–54. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.016758.

- Thurman AR, Litts PL, O'Rourke K, et al. Patient acceptance of medical student participation in an outpatient obstetric/gynecologic clinic. J Reprod Med. 2006;51(2):109–114.

- Woolner A, Cruickshank M. What do pregnant women think of student training? Clin Teach. 2015;12(5):325–330. doi:10.1111/tct.12312.

- Yang J, Black K. Medical students in gynaecology clinics. Clin Teach. 2014;11(4):254–258. doi:10.1111/tct.12122.

- Sayed-Hassan RM, Bashour HN, Koudsi AY. Patient attitudes towards medical students at Damascus University teaching hospitals. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):13. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-13.

- Vaughn JL, Rickborn LR, Davis JA. Patients' attitudes toward medical student participation across specialties: a systematic review. Teach Learn Med. 2015; 27(3):245–253. doi:10.1080/10401334.2015.1044750.

- O'Flynn N, Wass V, Rymer J. Women's attitudes to the sex of medical students in a gynaecology clinic: cross sectional survey commentary: patients as partners in medical education. BMJ. 2002;325(7366):683–684. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7366.683.

- McLean M, Al Ahbabi S, Al Ameri M, et al. Muslim women and medical students in the clinical encounter. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):306–315. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03599.x.

- Marwan Y, Al-Saddique M, Hassan A, et al. Are medical students accepted by patients in teaching hospitals? Med Educ Online. 2012;17(1):17172. doi:10.3402/meo.v17i0.17172.

- Singer DA, Quek K. Attitudes toward internal and foreign migration: evidence from a survey experiment in China (October 17, 2017). MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2017-28. 2017. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3055221

- Monnickendam SM, Vinker S, Zalewski S, et al. Patients' attitudes towards the presence of medical students in family practice consultations. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3(12):903–906.

- Tang TS, Skye EP, Steiger JA. Increasing patient acceptance of medical student participation: using interactive theatre for faculty development. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(3):195–200. doi:10.1080/10401330903014145.