ABSTRACT

To successfully respond to the increasing needs and demands of clients, social workers must be equipped with a broad range of knowledge and skills. Due to limitations with traditional in-person methods, the field is considering virtual simulations to enhance students’ knowledge and competency-based skills. Virtual simulations are a method of using a computer/software/the Internet to teach knowledge and competency-based skills. In this article, we examine the different types of virtual simulations, categories of educational topics and competency-based skills that these virtual simulations address, and evidence of their usefulness. Initial findings suggest that these online learning modalities may not only be effective at teaching knowledge and competency-based skills, but that they may bridge a gap that exists in traditional teaching methods.

Traditionally, the field of social work has relied on in-person practical and classroom-based learning (e.g., case studies, observations, peer role play) of social work students. Given the recent global pandemic and government-led actions to contain the spread of the virus by limiting person-to-person contact, the education of students who wish to become social workers is increasingly moving online. Of particular concern to stakeholders in the field of social work (e.g., research community, practitioners and professionals, health and social service providers) is whether students can adequately learn competency-based skills using virtual simulations as in-person learning opportunities have been significantly restricted. This question becomes all the more critical when we consider that between 2017 and 2026 the number of individuals entering the profession in Canada is expected to grow by an additional 28,000 (Statistics Canada, Citation2020).

In 2016, the labor market for social workers in Canada alone was 71,700 (Statistics Canada, Citation2020). Forty-three accredited Canadian Social Work programs (Canadian Association for Social Work Education, Citation2020) exist, each one training thousands of the country’s future social workers. This means that, in the coming years, tens of thousands of Canadians must acquire knowledge and skills to perform as competent social workers. In these changing times it is evident that more of these learners will turn to online learning. While competency-based training also benefits practicing social workers (e.g., professional development, continuing education), this article focuses on the clinical training of students, either Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) or Master of Social Work (MSW) students.

Competency-based training in the field of social work is a structured approach to training to achieve specific outcomes based on Standards of Practice as established by the Canadian Association of Social Work. Social workers perform a range of duties, such as interviewing individual clients to assess risk for domestic violence, referring families to agencies that provide financial assistance, and advocating for children in the welfare system. These duties require a variety of skills, such as assessment, empathy, active listening, and coordination (managing multiple assignments). Given that social workers strive to enhance the well-being of individuals and to meet the complex requirements of those who are vulnerable or oppressed, it is essential for those in the profession to receive sufficient competency-based training.

Traditionally, students have been taught competency-based skills using methods, such as case studies, observations, or role playing with peers. With case studies, students read over a detailed hypothetical scenario of a client, family, or event and are asked to identify challenges as well as solutions to manage the case. Case studies allow students to use critical thinking skills to apply what they have learned to various scenarios. While useful, case studies are limited in that they do not allow students to practice their skills with clients. With observations, students watch a hypothetical scenario of a client, family, or event—either via video or with actors—and discuss, either in small groups or in a large class setting, what was done well versus what mistakes were made. Observations are also limited in that they do not allow students to directly practice any skills. With role playing, social workers interact with a peer or another social work student posing as a client. The goal here is to practice a certain skillset, such as assessing a client for risk, or working with a client to develop a treatment plan in a safe environment where mistakes can be made. Often, the role playing is done in front of peers and directed by an instructor so the entire group can learn from the activity. Out of the traditional trainings, role playing most closely parallels what social workers will be expected to do on the job and allows for direct skills practice. However, students often state they do not like practicing while being watched by peers or instructors as it increases their anxiety (Mackey & Sheingold, Citation1990). Indeed, fear of negative evaluation affects anxiety when students are being rated by others (M. M. Carter et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, role plays are time-intensive and imperfect because students often know one another and find it difficult to remain focused and in character throughout. They also lack standardization, which is concerning, as ideally all students receive the same caliber of training.

To address some of the concerns with peer role plays, many have turned to simulated or standardized clients (I. Carter et al., Citation2011). As summarized by Phillips et al. (Citation2018), this methodology uses “lay persons or actors who present with certain symptoms and are evaluated and treated by novice practitioners” (p. 621). By using standardized/simulated clients, instructors are able to maintain a higher level of control over the situations they want their students to practice and are more realistic as compared to practicing with peers. However, with this methodology the fear of negative evaluation still exists (as this is done with at least one other person [the actor], and usually with peers and an instructor observing to provide feedback); it is time- and cost- intensive; and true standardization across all students is difficult to reliably achieve with human actors.

As a result of these limitations, the field has begun to consider “virtual simulations” for competency-based training. While many definitions for this nuanced training methodology exist, we have created a definition that fully encompasses the range of simulations available for use. Thus, when we use the term “virtual simulation” we are referring to a method of using a computer/software/the Internet to teach knowledge and competency-based skills. Virtual simulations have numerous advantages to traditional competency-based training methods; namely, that they give students practice opportunities that are as close to real life as possible. While creating virtual simulations is initially a time- (and potentially costly) investment, once developed they become extremely time- and cost-effective. Furthermore, virtual simulations can be standardized, which allows for increased consistency of training for social workers. Virtual simulations increase opportunities for online/distance learning as they are easily shared through online platforms. Given that many students must balance the needs of schoolwork with paid work and family duties (among other responsibilities), having the flexibility to complete trainings remotely can increase the reach for potential social work students and also promote diversity in the workforce (Goldingay & Boddy, Citation2017).

Knowledge synthesis objective and research questions

The overall purpose of our knowledge synthesis was to provide an overview of the state of the research on virtual simulations in social work. Specifically, we aimed to answer three broad questions: (a) What are the different types of virtual simulations that exist in social work? (b) What are the different kinds of knowledge or skills these virtual simulations aim to teach? and (c) What research has been conducted to evaluate their effectiveness? To address this objective and to answer our research questions, we conducted a scoping review, which is a knowledge synthesis methodology that is appropriate when researchers wish to provide an overview of available research without answering well-defined research questions (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

Methods

Identifying relevant studies

To locate relevant literature for this scoping review, we conducted a structured search in Embase, Medline, PsycInfo, PsycARTICLES, CINAHL, ERIC, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, Family Studies abstracts, Social Work Abstracts, SOCindex, and Sociological Abstracts (Social Services Abstracts included). Our search (completed by one individual) included all articles up until 2019 (last conducted on July 24, 2019) using the search terms “simulation,” “standardized patients,” “standardized clients,” “mental health,” or “social work.” An example of the search (for SOCindex) is as follows: ((“simulat*” OR “osce” OR “standardized patient*” OR “standardized client*”) AND (“social work*” OR “mental health”)). This search yielded 4,282 articles. After removing duplicates, 2,351 records remained.

Study selection

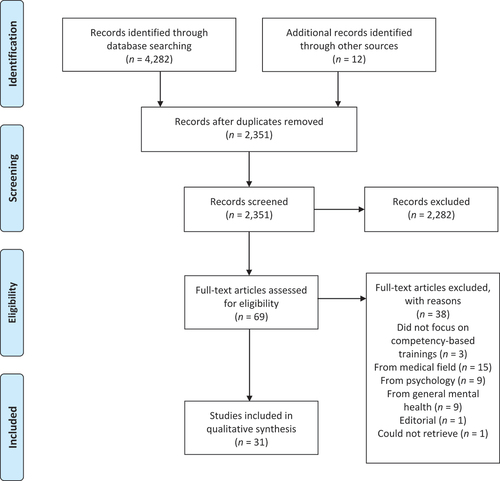

To be included, articles had to discuss a virtual simulation that focused on competency-based skills in social work. Because the purpose of a scoping review is to be “as comprehensive as possible” (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005, p. 23) we decided to be broadly inclusive when selecting studies. Specifically, we did not make restrictions based on age, gender, race, ethnicity, year, methodology, or article type (e.g., review vs. empirical article). After screening the abstracts, 2,282 were excluded because they did not fit the study’s inclusion criteria. This resulted in a total of 69 full-text articles that were assessed for eligibility. The first author read the full articles to decide whether they should be included in the review. Articles were excluded if they did not focus on competency-based virtual simulations (k=3), did not focus on social work (k=33), if the article was an editorial (k=1), or if the full text was not available (k=1). Thus, a total of 31 articles focusing on virtual simulations in social work were reviewed. See for an overview of articles identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and included.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher et al., Citation2009) provides an overview of articles we identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and included. This process resulted in a total of 31 articles that focused on virtual simulations in social work that focused on teaching competency-based skills. In the text, we discuss our three research questions based on the findings presented in these articles.

Charting the data

Our approach to data charting took a broader view; for example, by including detailed information on the technology used to create the virtual simulation so we could group the types of simulations into categories. The first author entered all information into a data charting form using Microsoft Excel. We recorded information on author, year of publication, detailed information on the virtual simulation (technology used to create it, purpose of simulation, etc.), methodology, measure of effectiveness, and results.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

After charting the information from the studies we were able to provide a narrative account of the findings by discussing the (a) types of virtual simulations that exist within the field of social work (based on detailed information on the virtual simulation), (b) categories of competency-based skills and educational topics addressed through these virtual simulations (also based on detailed information on the virtual simulation), and (c) evidence of their effectiveness (based on each study’s methodology, measure of effectiveness, and results).

Results

Research question 1: What types of virtual simulations exist within the field of social work?

Of the 31 papers reviewed, most discussed virtual worlds (k=10; two of which were reviews), followed by computer-assisted instructional/interactive videodisk programs (k=9; four of which were reviews), interacting with virtual humans (k=6; one of which was a review), virtual learning environments (k=5; one of which was a review), video diaries (k=1), and family simulations (k=1). Please note that some papers discussed more than one type (detailed in ). Here, we review the range of simulations in order from most basic to most advanced. Ordering was subjectively rated by authors, and thus we acknowledge the subjective nature of this methodology. The goal is not to place more merit on one versus the other, but to try and organize the type of virtual simulations by time and cost intensiveness of creation and implementation to help guide the pedagogy-based decision-making process of selecting potential simulations for one’s own use. Based on the available time and resources of a particular instructor or department, one methodology may be preferred to another.

Table 1. Overall summary of virtual simulation training articles in social work

Computer-assisted instructional (CAI)/interactive videodisk (IVD) programs

Computer-assisted instructional programs deliver text-based information about a concept, such as goal-focused interviewing to the user who is then asked to answer questions about it (Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993, Citation1994; Seabury & Maple, Citation1993). IVD programs are similar, but slightly more advanced. IVDs combine computer programs with video images and sound to deliver educational content to the user; thus, the user is given general information about a concept (e.g., crisis counseling) in the form of audiovisual information and then asked questions about it (Reinoehl & Shapiro, Citation1986; Seabury, Citation1995; Seabury & Maple, Citation1993; Thurston, Citation1993; Wodarski et al., Citation1996; Wodarski & Kelly, Citation1988).

Example

One of the first IVDs was the Crisis Counseling program (Seabury & Maple, Citation1993). First, a user completes a self-directed tutorial that covers the concepts of crisis theory. Next, the user watches a series of audiovisual clips of a fictitious client; after each clip, the program gives the user a series of response options and asks what the user would like to do during the interview. Based on what the user selects, the storyline changes (similar to a “choose your own adventure”). There are typically four response options. Two options are “appropriate” and move the interview along the successful route, one option will sidetrack the interview, and another option is deemed “inappropriate” and will lead to unfavorable outcomes. A user can complete the interview as many times as they want to identify “good” versus “bad” responses. After the “interview,” the user takes a quiz to test their knowledge of the concepts taught in the IVD program. The user receives an overall score as well as feedback to explain why certain questions were wrong. CAI/IVDs pioneered the beginning of the movement to use technology to build competency-based skills. The technology used for the CAI/IVDs was extremely innovative for its time, and we consider this methodology to be what pioneered the movement of virtual simulations in social work, as they introduced users to the concept of learning information via computers and practicing skills in an interactive way. However, the technology is now over 20 years old. Because so much progress has been made since then (more recent technology discussed below), the CAI/IVDs discussed here are not being used today.

Video diaries

Another technique for teaching skills is a video diary. Students watch a series of video diary entries of a fictitious client played by a professional actor who tells their story. After watching the video diaries, the students complete their assignments to reflect on and solidify their understanding of what was seen.

Example

Evelyn’s Story (Goldingay et al., Citation2018; https://video.deakin.edu.au/media/t/0_ccl6vw8c) is about Evelyn, a woman who has a husband who is violent and abusive. Students watch Evelyn tell her story and then practice the skills of being her social worker. After that they complete various assignments, such as critically appraising theoretical approaches to understand and deal with violence and abuse. Given the time and resources needed to create this kind of training (e.g., hiring a professional actor), not many video diaries exist. In fact, Evelyn’s Story was the only video diary found to be evaluated in the social work literature.

Virtual learning environments (VLEs)

VLEs refer to the use of online platforms (e.g., WebCT, Blackboard) to deliver information to students via lectures, videos, text, e-bulletin boards, or e-mail communication. VLEs range in terms of the technology as well as content. For example, Galambos and Neal (Citation1999) described the very first efforts to introduce VLEs into social work education. Specifically, the authors discuss techniques based on andragogical theories of adult education that can be used to integrate computer simulations and Internet research into undergraduate education curriculums for social work students. They argue that students initially must be briefed on what is an online simulation and how it works; following that, students must actually engage in the simulation activity; and third, students should be debriefed on the “so what” aspect of it to stimulate critical thinking. Initially, these “simulations” were any teaching technique that replicated real-life decision making and allowed students to interact with one another using an online format. Since then, VLEs have increased in their sophistication (see Shorkey & Uebel, Citation2014 for a detailed history of the development of instructional technology).

Example

Some online courses include bulletin boards, e-mails, online testing, and the tracking of students’ progress (Peters, Citation1999). Others include the videotaped role play of clients that are posted online. In this scenario, students can watch the videos and comment on aspects of them in an online bulletin board where they discuss assessment and interview skills with classmates (Shibusawa et al., Citation2006). The most advanced VLE in social work allows students to complete asynchronous components (e.g., watching videos and completing written simulation activities on their own time) as well as synchronous components (e.g., learning hands-on skills with their instructors in “real time”). As an example of a synchronous component, students get to practice various skills (e.g., motivational interviewing, empathic reflection) by interacting virtually with an actor who simulates a client; immediately following the interaction the instructor provides feedback (Phillips et al., Citation2018). Other VLEs are designed to teach very context-specific learning objectives; for example, Wastell et al. (Citation2011) designed “BRIGIT,” a series of e-cases intended to simulate the electronic systems used in children’s statutory services in the United Kingdom.

VLEs allow colleges and universities to reach more students and to teach a greater diversity of social work students who might face barriers to traditional settings that require an in-person meeting. While the use of VLEs is growing, only a handful of schools are pioneering this movement (e.g., University of California, Berkeley; University of Chicago; University of Wisconsin–Madison; University of Texas at Arlington). As a growing number of programs begin to rely on some form of instructional web-based technology, it is imperative for more research to be conducted on how to make this an integral part of competency-based learning in social work (Shorkey & Uebel, Citation2014).

Family simulations

Given the rise in the number of multigenerational families (when at least two generations live in the same household), a unique type of simulation was created to help social workers better understand the dynamics of these families so they can better serve their unique needs. As described by Otters and Hollander (Citation2018), three simulations have been created to illustrate various examples of multigenerational households (Smith family, European American/White; Johnson family, African American/Black; Gomez family, Mexican American/Hispanic or Latino). For each family, information is given on who is in the household, how old is each member, when they joined the family, and some basic background information on the family members. The user can select an individual family member to find out about them, and then can “fast forward” to see how each family member affects the others over the course of time. While this can be used as a teaching tool in a variety of ways, Otters and Hollander (Citation2018) described a situation where the instructor walks the students through the simulation. The instructor asks questions about the family, discusses concerns about the family, as well as strengths and how to build on those. The learning experience ends with some closing remarks about multigenerational families. While only one family simulation (which happened to focus on multigenerational families) was identified, this work shows how technology can be quickly adapted to address novel and emergent training needs of social workers.

Interacting with virtual humans

One of the most advanced kinds of virtual simulations used in social work has students directly interacting with realistic, computer-generated humans to learn competency-based skills (O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Putney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Reeves et al., Citation2015; Washburn et al., Citation2016).

Example

One simulation, called Rosie 2, follows social worker Andrew and health visitor Beth through a home visit where child neglect is a concern (Reeves et al., Citation2015). In the simulation, students are led through 13 scenes across various environments (e.g., office, home, school) where they can interact with characters and the environment while logging areas for concern. Throughout the simulation, discussion points are raised, and key decision points emerge where participants can alter the outcome based on what they indicate the characters should do in the given situation. The goal of this simulation training is to familiarize students with the process of home visits and to allow them to explore practice options in a safe and risk-free environment.

The most advanced examples in the field of social work allow students to interact with virtual humans using built-in speech-to-text technology (O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Putney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Washburn et al., Citation2016). Washburn and colleagues created six different virtual patients so students can practice their assessment skills for a variety of symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression) by speaking directly to a virtual human through a microphone. Currently, this technology does not provide immediate feedback to help students learn from their mistakes. However, to address this gap, authors devised a methodology where students are supervised during the simulation and given feedback from a mental healthcare professional. Others (O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Putney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b) use a platform known as SIMmersion (Citation2018) that combines video, voice recognition, and user control to allow students to practice assessment skills with virtual clients. Furthermore, this technology also provides students with real-time feedback. While extremely impressive, this technology is still being “perfected” and takes a large amount of time and resources to create. Once created, however, distribution to students is relatively easy.

Virtual worlds

The most complex and increasingly popular methodology for teaching competency-based skills is a virtual world. With virtual worlds, students create their own avatar (a computerized character) where they perform as themselves. In this virtual environment, avatars interact with the environment or with other avatars—often students in the same class—to learn necessary skills (Chamley et al., Citation2011; Driver & Ferguson, Citation2019; Lee, Citation2014; Levine & Adams, Citation2013; Martin, Citation2017; Reinsmith-Jones et al., Citation2015; Tandy et al., Citation2017; Vernon et al., Citation2009; Wilson et al., Citation2013). Most often, the software used is Second Life, developed by Linden Lab Research, Inc. (see Vernon et al., Citation2009 for a review of Second Life).

Example

Wilson et al. (Citation2013) created a virtual world using Second Life to help MSW students learn engagement and assessment skills specific to home visiting (e.g., gaining entry to a home, observation of the physical environment, how to deal with distractions/interruptions). The use of the simulation was preceded with lectures on home visits so students could understand the basics of best practices, and then the simulation was used as a supplemental training activity. For the actual simulation, students took control of a social worker avatar tasked with entering her client’s apartment. Once inside the apartment, a number of environmental hazards become apparent and some disruptions occur (e.g., having an unexpected person in the house who is distracting to the visit). This simulation allows students to be introduced to the concept of a home visit (as well as the dangers inherently associated with it) in a risk-free environment.

Other virtual worlds allow students to explore entire cities. For example, Chamley et al.’s (Citation2011) “Central City” (created in Second Life) was developed to teach social work students how to work with children, young people, and families in palliative care. Students create their own avatars (to reflect themselves) and then visit various locations (e.g., hospital, children’s hospice, school environments). The goal is for students to use problem-based learning triggers throughout the experience to help manage the case.

Perhaps the most technologically advanced virtual world is described by Driver and Ferguson (Citation2019), which uses a 360-degree camera to create a fully immersive experience for social work students. In this example, students wear a virtual reality headset and are able to explore various details of a 3-D environment by walking around the room and moving their heads to see various details in the space just like they would in real life. The goal is to help students experience what it feels like to “really be somewhere,” which can be extremely valuable if the actual environment is otherwise difficult to access in real life. The authors used Canvas, which enables them to package the environment into a 3-D experience with headsets; it also allows students who do not have access to the headset to have a similar 2-D experience through their desktop or browser. The goal of Driver and Ferguson’s (Citation2019) study was to have first-year social work students walk around a client’s home environment and consider how to use certain objects in the home to build a relationship with their clients (e.g., using a refrigerator magnet as an opportunity to engage).

Virtual worlds provide the closest parallel to real-world experiences that social workers will face in the field. While not completely realistic, they offer opportunities for students to gain knowledge and practice skills in a safe, risk-free environment. Fortunately, these platforms are available for purchase and sharing; however, they range greatly in terms of cost. For example, simulations in Second Life are free to create, whereas the cost for obtaining the equipment needed for a virtual reality simulation (e.g., hardware, software) can cost thousands of dollars. In addition to access, there are also the costs associated with development, which vary greatly by simulation. Furthermore, the cost for students to use the simulations will vary depending on a range of factors (e.g., whether it is embedded into a course and therefore included in tuition).

Research question 2: What are the different kinds of knowledge or skills these virtual simulations aim to teach?

The virtual simulations reviewed in this article aim to teach a variety of competency-based skills or to provide education on various topics relevant to social work. Here, we group the trainings into four major categories: interactive case studies (k=4), assessment/interview skills (k=12), providing care in unique situations (k=5), and specific educational topics and skills (k=6). Some papers included more than one virtual simulation, so it is possible for one paper to be placed in multiple categories. Furthermore, reviews that discuss the use of virtual simulations generally or the history of virtual simulations (e.g., Reinoehl & Shapiro, Citation1986; Shorkey & Uebel, Citation2014; Vernon et al., Citation2009; Washburn & Zhou, Citation2018; Wodarski et al., Citation1996; Wodarski & Kelly, Citation1988) are not included here.

Interactive case studies

Many of the virtual simulation trainings involve interactive case studies with the aim of teaching competency-based skills associated with home visits (Goldingay et al., Citation2018; Reeves et al., Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2013) and service planning (Peters, Citation1999). For example, Evelyn’s Story involves an interactive case study with a woman who is experiencing violence in an interpersonal relationship (Goldingay et al., Citation2018). Students are asked to engage with various concepts (e.g., critically appraise theoretical approaches to understanding violence and abuse), acquire knowledge (e.g., learn what is involved during home visits), and practice skills (e.g., self-manage emotional reactions to overwhelming situations, critical thinking, assessment). Rosie 2 also asks students to learn skills associated with a home visit; however, this simulation training covers visiting a family where neglect is a significant concern (Reeves et al., Citation2015). The focus of Rosie 2 was to help students practice skills (e.g., interacting with a variety of family members) and experience real emotional responses that are likely to occur during actual home visits. Another simulation focused specifically on service planning (e.g., identify strengths and barriers) based on fictitious case histories (Peters, Citation1999). Case studies are often used in social work education, as they are extremely useful for applying knowledge and skills to new situations. However, traditional case studies only allow students to read information and then apply knowledge and skills by writing a report. Virtual simulations improve on the learning experience by allowing students to directly interact with clients in the form of avatars or videos.

Assessment/interview skills

Other virtual simulation trainings focus specifically on teaching students how to conduct assessments and interviews (Levine & Adams, Citation2013; Martin, Citation2017; O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993; Phillips et al., Citation2018; Putney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Seabury, Citation1995; Seabury & Maple, Citation1993; Shibusawa et al., Citation2006; Tandy et al., Citation2017; Washburn et al., Citation2016). For example, Washburn et al.’s (Citation2016) virtual simulation aims to teach students how to develop brief assessment skills for anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder. To do this, students interact in a therapist’s office with six different virtual patients, all of various ages, genders, and ethnicities. Similarly, another training focuses on teaching intake assessment skills for depression and anxiety by having students interact with avatars (Martin, Citation2017) and others focus on screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for substance use (O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Putney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b). One training allows students to interact with a trained actor virtually (e.g., through audio and video connection) to practice skills associated with motivational interviewing, problem-solving therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy (Phillips et al., Citation2018). Tandy et al.’s (Citation2017) simulation focuses on teaching interview skills through the use of a chatbot, defined as “a prototype standardized client avatar that runs automatically based on programming” (p. 66). Other trainings focus on assessment and interview skills for couples therapy (Shibusawa et al., Citation2006) by using videotaped role plays and online discussion boards to discuss the interactions. Some focus on interviewing clients in active crises (Seabury, Citation1995) or for developing skills for specialized types such as goal-focused interviews (Seabury & Maple, Citation1993). In addition to being more realistic compared to role playing with other students in class (a traditional technique), these trainings allow students to complete the interview multiple times over to learn from their mistakes.

Providing care in unique settings

Some virtual training simulations focus on teaching students how to provide care to clients in unique situations (that may not be covered in traditional general educational curriculums and are considered to require specific skills). For example, teaching students how to counsel clients who are living in multigenerational households (Otters & Hollander, Citation2018), providing care for children in palliative care (Chamley et al., Citation2011), doing group treatment for adolescents in residential placement (Seabury & Maple, Citation1993), serving families and children in rural locations (Thurston, Citation1993), or providing care in a home environment or a “place of safety” where individuals are taken after an arrest to be assessed by social workers (Driver & Ferguson, Citation2019, p. 1). These trainings expand the skillset of social work students to allow them to deliver care to clients in unique situations. It is difficult to provide real-life learning opportunities to students for events that are not as common, so having the option of virtual simulation trainings addresses this by creating opportunities for practice.

Specific educational topics and skills (misc.)

Other trainings focus on helping students better understand, for example, oppression and discrimination (Reinsmith-Jones et al., Citation2015), labeling and stigmatization (Lee, Citation2014), or asking students to uncover patterns of institutional racism and sexism (Seabury, Citation1995). Yet other trainings focus on developing general skills associated with being a social worker, like critical thinking and group decision making (Galambos & Neal, Citation1999; Reinsmith-Jones et al., Citation2015). Some are incredibly specific, such as teaching students how to navigate the electronic system that is used in the United Kingdom for children’s statutory services (Wastell et al., Citation2011).

Research question 3: What research has been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of these virtual simulations?

While virtual simulations will theoretically benefit students by providing more opportunities to develop competency-based skills, we must first examine the empirical evidence as seen in the literature to determine if this methodology (in its current state) is effective.

As the studies reviewed in this article use different approaches, we organized this section by similar methodologies; specifically, we summarized results of studies that used (a) qualitative methods (k=10; nine of which reported simulations were effective), (b) posttest designs (k=9; eight of which reported simulations were effective), (c) within-subjects designs (k=7; five of which reported simulations were effective), and (d) between-subjects designs (k=5; two of which reported simulations were effective). Because some studies used multiple methodologies (detailed in ), one study may be mentioned in multiple sections.

Qualitative studies

Ten studies used some form of qualitative methods to assess the effectiveness of their virtual simulations (Driver & Ferguson, Citation2019; Goldingay et al., Citation2018; Lee, Citation2014; Martin, Citation2017; Reinsmith-Jones et al., Citation2015; Shibusawa et al., Citation2006; Tandy et al., Citation2017; Washburn et al., Citation2016; Wastell et al., Citation2011; Wilson et al., Citation2013). Specifically, Driver and Ferguson (Citation2019) asked students to informally reflect on their experience after using a virtual simulation; Goldingay et al. (Citation2018) asked students to type out their reactions to the simulations in an open-ended response; Lee (Citation2014) asked students to post their reactions to the virtual simulation in an online forum; Martin (Citation2017) asked students to write open-ended text comments about the simulation; Reinsmith-Jones et al. (Citation2015) asked students to journal about their experiences with the virtual simulations; Shibusawa et al. (Citation2006) conducted focus groups to assess how useful the students found the simulation to be; Tandy et al. (Citation2017) asked students to complete informal reflective papers and participate in quasifocus groups to describe their experiences; Washburn et al. (Citation2016) asked students to answer a series of open-ended questions to assess what could be done to improve the simulation; Wastell et al. (Citation2011) interviewed students about their experience with the virtual simulation; and Wilson et al. (Citation2013) conducted quasifocus groups with students to better understand their experience.

Results from the qualitative methods were overwhelmingly positive. Students indicated the virtual simulation trainings were interesting, useful, engaging, and facilitated understanding of threshold concepts (Driver & Ferguson, Citation2019); promoted critical thinking, ethical behavior, and reflectivity (Goldingay et al., Citation2018); felt the simulation was a fun and unique way to interact, was entertaining, interesting, exciting, and eye-opening (Lee, Citation2014); that simulations generated real emotions, helped with empathetic understanding of events, critical thinking, and reflection on their own discrimination (Reinsmith-Jones et al., Citation2015); that simulations facilitated learning by allowing them to practice at their own pace, and were positive and enthusiastic about the experience (Shibusawa et al., Citation2006); that they enjoyed the experience, found it engaging and fun, and felt as if they were really there (Tandy et al., Citation2017); felt the simulation helped reduce anxiety about doing assessments (Washburn et al., Citation2016); found the simulation convincing and engaging (Wastell et al., Citation2011); and that they felt the simulation was realistic and helped them practice skills in a realistic setting (Wilson et al., Citation2013).

However, there were some areas for improvement identified in the qualitative research as well. For example, students reported they wanted more time to practice and more support before doing the simulation (Wilson et al., Citation2013). In addition, some students experienced technical difficulties, felt it was hard to keep track of everything happening at once, were uncomfortable at times (Lee, Citation2014), found the simulation to be confusing and did not know how to work it (Martin, Citation2017). Some students thought the voice recognition software could be improved (Washburn et al., Citation2016), and there was also some criticism that the simulation did not offer closed captioning for students with hearing difficulties (Shibusawa et al., Citation2006).

Posttest design

Nine studies used posttest designs to assess students’ reactions to the virtual simulation after using it (Goldingay et al., Citation2018; Martin, Citation2017; Otters & Hollander, Citation2018; Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993; Reinsmith-Jones et al., Citation2015; Seabury, Citation1995; Seabury & Maple, Citation1993; Shibusawa et al., Citation2006; Washburn et al., Citation2016). Goldingay et al. (Citation2018) asked students to indicate how much they agreed with various statements (e.g., “Evelyn’s Story [the virtual simulation] helped me engage with key definitions”; Goldingay et al., Citation2018); Martin (Citation2017) asked students to answer nine survey statements based on their experience (e.g., how much they liked the virtual clinic, whether it allowed students to apply knowledge and skills); Otters and Hollander (Citation2018) asked students to answer how strongly they agreed with five survey questions (e.g., “learning about family life with an older adult in the home was very helpful to me as a social worker”); Patterson and Yaffe (Citation1993) asked students to indicate how easy the simulation was to use and how much they liked it overall; Reinsmith-Jones et al. (Citation2015) asked students to respond to six questions about their experience (e.g., whether the simulations were good exercises to teach them about various topics); Seabury and Maple (Citation1993) and Seabury (Citation1995) asked students if the simulation increased their interest in and knowledge of subject matter; Shibusawa et al. (Citation2006) asked students to complete a 20-item survey about the ease of use of the simulation, whether it helped them improve their communication with classmates, and effectiveness for learning; Washburn et al. (Citation2016) asked students to complete a feedback form about usability.

Overall, results were very positive as far as the user experience. Students reported that virtual simulations helped them engage with key definitions (Goldingay et al., Citation2018); found the simulation to be helpful to them as social workers (Otters & Hollander, Citation2018); that they liked this form of learning (Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993); felt the simulations were good exercises to teach them about discrimination, group processes and decision making, strengths perspective, oppression, social work values and skills (Reinsmith-Jones et al., Citation2015); increased their interest in and knowledge of the subject matter (Seabury, Citation1995; Seabury & Maple, Citation1993); felt the simulation helped improve their understanding of assessment skills, general interview skills, and specific interview skills for couples, and that the design facilitated communication with their classmates regarding role plays (Shibusawa et al., Citation2006); felt the simulation helped them to work with actual clients, that it had a positive effect on their clinical skills, that it was easy to use, that they had confidence in the simulation, and intended to use it frequently (Washburn et al., Citation2016).

However, there were some negative responses from the surveys as well. For example, students in Martin’s (Citation2017) study reported that they did not feel like they were communicating with a real person, were not able to be expressive, did not like using the simulation, and did not find it to be a useful experience. Students in Patterson and Yaffe’s (Citation1993) study also reported that the virtual simulation was more difficult to use as compared to traditional trainings. In a similar vein, students in Washburn et al.’s (Citation2016) study reported needing technical assistance and students in Shibusawa et al.’s (Citation2006) study were dissatisfied with their ability to access the simulation from home (e.g., reported technical difficulties).

Pre–post design

Seven studies used a pre–post (within-subjects) design to assess change from before using the simulation to afterward (Levine & Adams, Citation2013; O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993; Peters, Citation1999; Putney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Washburn et al., Citation2016). Given the variability across studies that used pre–post designs, this section further groups studies together based on shared elements.

Two studies assessed change by asking students to complete tasks that were coded for skills before and after using the simulation. To assess students’ changes in diagnostic accuracy, Patterson and Yaffe (Citation1993) had students complete diagnostic case studies before and after completing the virtual simulation. Results showed an improvement in diagnostic accuracy from pretest to posttest. To assess changes in students’ ability to create service plans, Peters (Citation1999) had students create service plans (which were evaluated and coded based for skills such as identification of strengths and barriers, development of goals and objectives) before and after completing a web-based course. Students improved in their service planning from pretest to posttest.

One study (Washburn et al., Citation2016) assessed students’ diagnostic accuracy and basic clinical assessment skills by asking students to complete a diagnostic rating form (coding for skills such as the ability to get a specific client history or provide a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual diagnosis) and a basic clinical assessment survey (nine items tapping into interviewing skills) before and after completing the virtual simulation. Results showed an improvement in diagnostic accuracy and basic clinical assessment from pretest to posttest.

Two studies assessed changes in students’ self-reported skills by asking them to fill out a pretest questionnaire at the beginning of an online course that included the use of a virtual simulation. Later on, students were asked to fill out the same questionnaire at posttest(s). Levine and Adams (Citation2013) asked students to complete a questionnaire assessing self-efficacy to perform specific case management intake, assessment, and related tasks (e.g., developing a plan for providing case management, responding empathetically to a consumer) after the first module of a course focused on case management. Students then completed the online course, which also included an 8-week synchronous role play in a virtual world. At the end of the 8 weeks, students completed the same questionnaire. Results suggest students felt more confident in case management from pretest to posttest. Similarly, O’Brien et al. (Citation2019) asked students to complete the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) Attitudes, Self-Perception of Skills, and Knowledge (SAK) assessment at the beginning of an online course. Students then completed the virtual simulation and were asked to complete the SAK assessment immediately afterward, and then again 30 days later. While students showed no change in overall SBIRT confidence, importance, or attitudes (e.g., subscales of the measure), students did show improvement with regard to specific items (e.g., I am confident in my ability to screen patients or clients for alcohol/drug problems; I am confident in my ability to refer patients or clients with alcohol/drug problems) immediately following the virtual simulation as well as 30 days later.

Finally, two studies asked students to complete a virtual simulation (which was coded for competence in various skills) at the beginning of the course. Students then completed the course, during which they were allowed to practice the simulation as frequently as they wanted. At the end of the course, students completed another virtual simulation (which was coded for the same skills as pretest). Specifically, Citation2019a (2019a) asked students to complete a SIMmersion virtual simulation (which was scored for skills in creating a motivating conversation, using motivational interviewing principles, and using tools effectively). After students finished an online class to teach competence in screening and brief intervention (which included unlimited use of the simulation), they completed another virtual simulation that was again coded for the previously mentioned skills. Results showed that students improved on developing a motivating conversation, using motivational interviewing principles, and using tools effectively (Putney et al., Citation2019a). In a similar study, Putney et al. (Citation2019b) asked students in two separate courses (Alcohol, Drugs, and Social Work Practice; Motivational Interviewing) to complete a SIMmersion virtual simulation that was scored for skills in screening, brief intervention, and patient management (Alcohol, Drugs, and Social Work Practice course) or motivational interviewing mechanisms, change planning, and patient engagement (Motivational Interviewing course). Students then completed the course, which also included unlimited use of the virtual simulation. At the end of the course, students completed another simulation, which was coded for the previously mentioned skills. Students in the Alcohol, Drugs, and Social Work Practice course showed an improvement in skills for screening, brief intervention, but not patient management; students in the Motivational Interviewing course showed an improvement in skills motivational interviewing mechanisms, change planning, and patient engagement.

Thus, overall results from studies using pre–post designs were promising, as students felt more confident in case management (Levine & Adams, Citation2013); improved their skills in service planning (Peters, Citation1999); improved skills in creating a motivating conversation, using motivational interviewing principles, and using tools effectively (Putney et al., Citation2019a); improved skills in screening, brief intervention, motivational interviewing mechanisms, change planning, and patient engagement (Putney et al., Citation2019b); and improved diagnostic accuracy and basic clinical assessment (Washburn et al., Citation2016).

However, it should be noted that some studies did not show any differences from pretest to posttest (e.g., O’Brien et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, studies that examined change in skills that was embedded in a larger course (e.g., Levine & Adams, Citation2013; O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Putney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b) cannot concretely conclude changes were due to the virtual simulation alone. Thus, future research is needed to determine what improvements were due to the virtual simulation, the course, or a combination of the two.

Between-subjects design

Five studies used a between-subjects design to compare students who used the virtual simulation to a comparison group (Lee, Citation2014; O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993; Peters, Citation1999; Phillips et al., Citation2018) and one study compared a group of social workers to lay people (Reeves et al., Citation2015). Given the variability across studies that used between-subjects designs, this section further groups studies together based on shared elements.

Four studies compared students in a web-based course to a traditional course (Lee, Citation2014; O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Peters, Citation1999; Phillips et al., Citation2018). Phillips et al. (Citation2018) used a longitudinal quasiexperimental design to compare skills of traditional MSW students (who completed two internships over four semesters) to students who completed an online hybrid model (who completed an online course for one semester followed by one internship lasting three semesters). To do this, field instructors rated students’ skills in various areas (professionalism, ethics, thinking and judgment, cultural competency, social justice, evidence-based practice, person in environment, policy, current trends, and practice skills) at the end of each semester. Students who completed the online hybrid model improved their skills just as much as those in the traditional course; further, those in the online hybrid model outperformed those in the traditional course in a few key areas (e.g., social justice, evidence-based practice, policy).

Lee (Citation2014) compared students who participated in a virtual simulation (cocktail party where students were given labels) to students who completed the same cocktail party in person (students had labels taped to their backs). Students completed a survey to assess self-perceived learning, and the extent to which they felt the exercise enhanced relationships with colleagues, family members, and neighbors, as well as their comfort working with diverse population groups. It was found that students who completed the virtual simulation reported greater learning about diversity concepts, issues, and experiences; showed more self-awareness about perceptions related to issues of diversity; and felt better able to understand and resolve issues related to family and classmates as compared to in-person simulation.

O’Brien et al. (Citation2019, also discussed above) compared students who completed an online course coupled with a virtual simulation to students who only completed the online course by having them both complete a SBIRT SAK assessment. However, there were no significant differences between those in the traditional online class as compared to the class with the added virtual simulation.

Peters (Citation1999, also discussed above) compared students in a web-based course to those in an online class by having them create service plans, which were then evaluated and coded based on things such as identification of strengths and barriers, and development of goals and objectives. However, students did not improve their service planning skills more than the traditional training group.

One study (Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993, also discussed above) compared students who completed a virtual simulation (a computer-assisted instructional program) to those who completed a traditional instructional method (training manual) by having them both complete diagnostic case studies to assess their diagnostic accuracy. However, students did not improve their diagnostic accuracy more than those in the traditional training group.

Finally, Reeves et al. (Citation2015) examined health workers’ abilities to identify signs of neglect during a home visit and to maintain neutral facial expressions when observing signs of child neglect (using Noldus FaceReader software). Unfortunately, for purposes of this review, the authors’ aim was not to examine whether the simulation was more effective as compared to a comparison group. Rather, their study focused on comparing social workers’ abilities to maintain neutral expressions as compared to lay people (and found social workers were indeed more able to do so).

Thus, results from the between-subjects studies are mixed, as some studies showed students in the virtual simulation groups outperformed those in traditional courses (Lee, Citation2014; Phillips et al., Citation2018) whereas others found no differences (O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Patterson & Yaffe, Citation1993; Peters, Citation1999).

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This review sought to summarize the research on (a) types of virtual simulations, (b) categories of educational topics and competency-based skills of the simulations, and (c) evidence of effectiveness. With regard to types, the most commonly discussed simulation was that of a virtual world, where students are able to use an avatar to interact with a virtual environment and everyone within it. This type of virtual simulation is particularly appealing because a platform (i.e., Second Life) exists that makes it completely free to both create and use. While CAI/IVDs were frequently mentioned in the literature, the technology used in their creation is outdated and thus not particularly relevant for the current era. Virtual simulations that allow students to interact with virtual humans provide an opportunity for a very realistic skills-based practice that offers opportunity for immediate feedback. However, it should be noted that creation of these simulations often requires partnering with organizations who have expertise in virtual human development. Virtual learning environments are a popular methodology that allows a large number of students to learn from afar, which is of increasing importance today. Other simulations also exist (e.g., video diaries, family simulations) but were less common.

While there was a wide variety of educational topics and competency-based skills the virtual simulations addressed, one skillset that was by far the most common was assessment/interview skills. This may be due, in part, to the rising use of professional actors (simulated or standardized clients) to teach skills. While the use of professional actors allows students to practice skills in a realistic way, it is time- and cost-intensive and lacks true standardization in training. Using a virtual simulation addresses these issues and is a very promising methodology for such a foundational social work skill. However, while virtual simulations allow for a sense of realism, there is room for improvement in the technology.

In terms of effectiveness, there is overwhelming evidence that virtual simulations are generally well-liked by students and hold promise in terms of self-perceptions of utility (e.g., students often report an increase in their own knowledge and skills). However, the research examining changes in objectively measured skills (e.g., completing assessments that are coded for skills such as using motivational interviewing principles or patient management) that can be confidently said to be due to the virtual simulation is still in its infancy. Furthermore, there was such variability in terms of what each simulation consisted of (platform, type of simulation, topic covered, etc.), that we cannot yet know if one kind of simulation might be preferred over another. Thus, more research is needed to continue evaluating the efficacy of these simulations.

Limitations and future directions

While the research suggests the use of virtual simulations in social work is promising (e.g., students report the simulations are helpful, increase their knowledge in the subject matter, and improve key competency-based skills; Otters & Hollander, Citation2018; Seabury, Citation1995; Seabury & Maple, Citation1993; Washburn et al., Citation2016), much more research is needed to determine the effectiveness of this new methodology.

First, we need to move beyond research studies that only examine user acceptability; we must begin to assess whether the competency-based skills we are aiming to teach are actually changing. This can be done in a myriad of ways (e.g., self-reported skill improvement), but most conclusive statements will come from assessing changes in objectively measured skills (e.g., observationally coded assessment skills; diagnostic accuracy during interviews).

Second, the field needs to move toward randomized research designs, as this is the only methodology that allows us to conclude causality. Randomly assigning conditions (e.g., virtual simulation vs. treatment-as-usual) and including pre- and posttests with empirically validated assessment tools is essential for moving this area of research forward. At a minimum, researchers should use quasiexperimental designs that include a comparison group. Ideally, researchers can also begin to include long-term follow-ups to determine whether skill acquisition is maintained over time (the ultimate goal).

Addressing the learning curve through collaborations

There are practical constraints that make conducting research in this area difficult. First, there is an inherent learning curve to both creating and using virtual simulations. To create virtual simulations, researchers must first have access to specific software, which is not always freely available. However, even if researchers have access to the software there is the matter of learning to use it.

While daunting, research suggests it is possible to design certain kinds of virtual simulations in a relatively short amount of time. For example, Round et al. (Citation2009) offered a one-day workshop to teach groups of individuals in the medical and healthcare field to create a virtual simulation using OpenLabyrinth. With this software, participants interact with a virtual patient and make key decisions along the way, which either lead to a successful completion of the simulation or to feedback that steers participants toward making the correct decisions. The workshop included an introduction to what virtual patients are, what they do, a demonstration of a virtual patient, then a 4-hour practical session to show participants how to create the virtual patient. While 4 hours was not enough for the majority of participants to create a virtual patient, nine groups (out of 20) did finish within the 4-hour time frame. These nine groups had a shared subject area, which likely facilitated their progress. One year after the workshop, 29% of participants had completed a virtual patient and 35% were in the process of making one. Thus, it is possible to create virtual patients in a relatively short amount of time, with authors estimating a total of 20 hours of work from start to finish.

While promising, results from Round et al.’s (Citation2009) study were specific to one type of software and to topics within the medical field. Thus, it may be more efficient for researchers to collaborate with others who have relevant interests, both in terms of platforms and topic areas. For example, there is a substantial amount of relevant research being conducted in the field of psychology (e.g., Albright et al., Citation2016; Tanana et al., Citation2019) that would be relevant to social work.

Albright et al. (Citation2016) conducted rigorous evaluations of virtual simulations (e.g., randomized control designs) to teach military families how to identify signs of postdeployment stress and speak with their loved ones about getting professional help. To do this, authors use Kognito, a popular simulation training tool in psychology and the medical field that allows participants to follow a fictitious scenario (e.g., talking with a loved one) by watching the story of a virtual human (realistic, computer-generated human beings). Participants watch the scenario unfold and are led to key decision points where they are asked to answer what they would do in the particular situation. Typically, a series of response options will appear on the screen similar to a multiple-choice test and the participant selects which one is the best decision. Based on the appropriateness of the participant’s choice, the story will either continue on the “correct” path with favorable outcomes or will diverge to the “incorrect” path with negative repercussions. If participants make inappropriate choices, they are often given feedback to help them learn from their mistakes. Typically, participants can redo the simulation as many times as they want to learn what would happen to the storyline based on various decisions.

This methodology and subject matter are particularly relevant to social work; through collaboration, researchers in the field of social work could gain access to these kinds of trainings and expedite the process of testing them within their own area. Furthermore, collaborations could help connect instructors who want to begin using virtual simulations in their classrooms with instructors who already doing so. However, even with help getting access to and learning these new methodologies, there is still the issue of cost. Costs vary depending on the type of simulation. For example, some simulations are free to create (e.g., Second Life) whereas others require paid partnerships with organizations (e.g., SIMmersion) or expensive equipment (e.g., thousands of dollars for virtual reality hardware and software). Additionally, there is the issue of cost to users. For example, simulations made as part of a grant-funded project or teaching collaboration might be accessible to students for free. In other situations, individuals may have to pay a license fee (e.g., $40/license for SIMmersion use). Given the variability across simulations, there is not a clear answer for how much simulations cost to create, or how much they cost to access. Either way, implementing this methodology will come at some sort of price.

Limitations of scoping review

The aim of this scoping review was to summarize virtual simulations that taught social work students knowledge and competency-based skills. Thus, we excluded articles that used simulations from different disciplines. However, this narrowed our scope of simulations that are available and might lend themselves to similar skillsets. For example, simulations in psychology exist that aim to teach assessment skills. While beyond the scope of this article, a summary of all virtual simulations that might be relevant would be beneficial for training the next generation of social workers.

In addition, only one author completed the data extraction protocol. Because we were limited to one coder, we were not able to provide information on reliability. Also, only one author participated in the selection of studies, which introduces potential bias. Furthermore, there was a wide variety in terms of how the simulations were created, what they attempted to teach, how researchers measured outcomes, and designs used to assess effectiveness. Thus, we were not able to provide concrete recommendations on which kinds of simulations should be used to teach competency-based skills. However, we believe this review is an important contribution to the literature, as it can help the field of social work to make decisions on what simulations they might consider using to train students, as well as to guide future research.

Conclusions

This article reviewed virtual simulation trainings that aim to teach knowledge and competency-based skills in the field of social work, their efficacy with respect to competency-based learning, and the state of the literature on this topic. This methodology improves on traditional trainings (e.g., case studies) by allowing for a more immersive and realistic experience. Importantly, the most advanced virtual simulation trainings allow individuals to repeatedly practice skills at their own pace while also receiving immediate feedback (Guise et al., Citation2012; O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Putney et al., Citation2019b), which are both necessary components of behavior change. Initial research suggests this area of training is promising, as students respond favorably to virtual simulations, and there is preliminary evidence to suggest they are effective in promoting skill acquisition as well. However, much more research needs to be conducted in this area, specifically research that rigorously evaluates changes in competency-based skills. Future research can be facilitated by collaborating with experts in relevant fields (e.g., psychology) to help those in social work gain access to and learn more about this methodology. While this area of research is still emerging, we hope this article will call to attention the potential promise of virtual simulation trainings and encourage future collaborations for both implementing and researching virtual simulations in the field of social work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Baker

Dr. Elizabeth Baker is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Calgary. Dr. Angelique Jenney is an Assistant Professor at the University of Calgary.

References

- *Denotes one of the 31 articles included in the literature review

- *Chamley, C., Coad, J., & Clay, C. (2011). engaging children and young people with palliative and complex care needs: OP32. Acta Paediatrica, 100, 110–111.

- *Driver, P., & Ferguson, V. (2019). Digitising experience: The creation and application of immersive simulations in social work training. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning [E-journal], 6(1–2), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1921/jpts.v16i1.1227

- *Galambos, C., & Neal, C. E. (1999). Macro practice and policy in cyberspace: Teaching with computer simulation and the internet at the baccalaureate level. Computers in Human Services, 15(2–3), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1300/J407v15n02_09

- *Goldingay, S., Epstein, S., & Taylor, D. (2018). Simulating social work practice online with digital storytelling: Challenges and opportunities. Social Work Education, 37(6), 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1481203

- *Lee, E. K. O. (2014). Use of avatars and a virtual community to increase cultural competence. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 32(1–2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2013.860364

- *Levine, J., & Adams, R. H. (2013). Introducing case management to students in a virtual world: An exploratory study. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 33(4–5), 552–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2013.835766

- *Martin, J. (2017). Virtual worlds and social work education. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1238953

- *O’Brien, K. H. M., Putney, J. M., Collin, C. R. R., Halmo, R. S., & Cadet, T. J. (2019). Optimizing screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) training for nurses and social workers: Testing the added effect of online patient simulation. Substance Abuse, 40(4), 484–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1576087

- *Otters, R. V., & Hollander, J. F. (2018). The times they are a’changing: Multigenerational family simulations. Marriage & Family Review, 54(2), 183–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2017.1403993

- *Patterson, D. A., & Yaffe, J. (1993). Using computer-assisted Instruction to teach Axis-H of the DSM-III-R to social work students. Research on Social Work Practice, 3(3), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973159300300307

- *Patterson, D. A., & Yaffe, J. (1994). Hypermedia computer-based education in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 30(2), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.1994.10672235

- *Peters, B. B. (1999). Use of the internet to deliver continuing education in social work practice skills: An evaluative study. The University of Texas at Arlington.

- *Phillips, E. S., Wood, G. J., Yoo, J., Ward, K. J., Hsiao, S. C., Singh, M. I., & Morris, B. (2018). A virtual field practicum: Building core competencies prior to agency placement. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(4), 620–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1486651

- *Putney, J. M., Collin, C. R., Halmo, R., Cadet, T., & O’Brien, K. (2019a). Assessing competence in screening and brief intervention using online patient simulation and critical self-reflection. Journal of Social Work Education, 47(3) , 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1671276

- *Putney, J. M., Levine, A. A., Collin, C.-R., O’Brien, K. H., Mountain-Ray, S., & Cadet, T. (2019b). Teaching note—Implementation of online client simulation to train and assess screening and brief intervention skills. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(1), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1508394

- *Reeves, J., Drew, I., Shemmings, D., & Ferguson, H. (2015). Rosie 2: A child protection simulation: Perspectives on neglect and the “unconscious at work.” Child Abuse Review, 24(5), 346–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2362

- *Reinoehl, R., & Shapiro, C. H. (1986). Interactive videodiscs: A linkage tool for social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 22(3), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.1986.10671751

- *Reinsmith-Jones, K., Kibbe, S., Crayton, T., & Campbell, E. (2015). Use of second life in social work education: Virtual world experiences and their effect on students. Journal of Social Work Education, 51(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2015.977167

- *Round, J., Conradi, E., & Poulton, T. (2009). Training staff to create simple interactive virtual patients: The impact on a medical and healthcare institution. Medical Teacher, 31(8), 764-–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903127677

- *Seabury, B. (1995). Interactive video disc programs in social work education: “Crisis counseling” and “organizational assessment.” Computers in Human Services, 11(3–4), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1300/J407v11n03_06

- *Seabury, B. A., & Maple, J. F. F. (1993). Using computers to teach practice skills. Social Work, 38(4), 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/38.4.430

- *Shibusawa, T., VanEsselstyn, D., & Oppenheim, S. (2006). Third space: A web-based learning environment for teaching advanced clinical practice skills. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 24(4), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1300/J017v24n04_02

- *Shorkey, C. T., & Uebel, M. (2014). History and development of instructional technology and media in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(2), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.885248

- *Tandy, C., Vernon, R., & Lynch, D. (2017). Teaching note—Teaching student interviewing competencies through second life. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(1), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1198292

- *Thurston, L. P. (1993). Interactive technology to teach rural social workers about special needs children and their families. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED358987

- *Washburn, M., Bordnick, P., & Rizzo, A. S. (2016). A pilot feasibility study of virtual patient simulation to enhance social work students’ brief mental health assessment skills. Social Work in Health Care, 55(9), 675–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2016.1210715

- *Washburn, M., & Zhou, S. (2018). Teaching note—Technology-enhanced clinical simulations: Tools for practicing clinical skills in online social work programs. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(3), 554–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1404519

- *Wastell, D., Peckover, S., White, S., Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., & Pithouse, A. (2011). Social work in the laboratory: Using microworlds for practice research. British Journal of Social Work, 41(4), 744–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr014

- *Wilson, A. B., Brown, S., Wood, Z. B., & Farkas, K. J. (2013). Teaching direct practice skills using web-based simulations: Home visiting in the virtual world. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 33(4–5), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2013.833578

- *Wodarski, J. S., Bricout, J. C., & Smokowski, P. R. (1996). Making interactive videodisc computer simulation accessible and practice relevant. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 13(1–2), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v13n01_03

- *Wodarski, J. S., & Kelly, T. B. (1988). Simulation technology in social work education. Arete, 12(2), 12–20.

- Albright, G., Adam, C., Serri, D., Bleeker, S., & Goldman, R. (2016). Harnessing the power of conversations with virtual humans to change health behaviors. mHealth, 2, 44. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2016.11.02

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Canada, S. 2020. Social worker in Canada. Version updated January. Statistics Canada. https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/marketreport/outlook-occupation/23025/ca#

- Canadian Association for Social Work Education. (2020). Directory of CASWE- ACFTS Accredited Programs. Version updated February. CASWE-ACFTS. https://caswe-acfts.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Accreditation-Directory-02-2020.pdf

- Carter, I., Bornais, J., & Bilodeau, D. (2011). 15. Considering the use of standardized clients in professional social work education. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 4, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.22329/celt.v4i0.3279

- Carter, M. M., Sbrocco, T., Riley, S., & Mitchell, F. E. (2012). Comparing fear of positive evaluation to fear of negative evaluation in predicting anxiety from a social challenge. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 3(5), 782–793. https://doi.org/10.5127/jep.022211

- Goldingay, S., & Boddy, J. (2017). Preparing social work graduates for digital practice: Ethical pedagogies for effective learning. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1257036

- Guise, V., Chambers, M., & Välimäki, M. (2012). What can virtual patient simulation offer mental health nursing education? Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(5), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01797.x

- Mackey, R. A., & Sheingold, A. (1990). Thinking empathically: The video laboratory as an integrative resource. Clinical Social Work Journal, 18(4), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00754841

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- SIMmersion. (2018). PeopleSim simulations train people for important conversations. Simmersion. https://www.simmersion.com/

- Tanana, M. J., Soma, C. S., Srikumar, V., Atkins, D. C., & Imel, Z. E. (2019). Development and evaluation of clientBot: patient-like conversational agent to train basic counseling skills. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(7), e12529. https://doi.org/10.2196/12529

- Vernon, R., Lewis, L., & Lynch, D. (2009). virtual worlds and social work education: Potentials for “Second Life.” Advances in Social Work, 10(2), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.18060/236