ABSTRACT

Collective action refers to any action that individuals undertake as group members to pursue group goals such as social change. In this chapter, we further extend the Social Identity Model of Collective Action (SIMCA) by including not just (politicised) identity but also moral motivations into its core, effectively integrating who “we” are with what “we” (will not) stand for. Conceptually, we utilise self-categorisation theory’s notion of normative fit to elaborate this special relationship between the moral and identity motivations for collective action. Empirically, we review two research projects (the experimental and survey-based Value-Identity Fit Project and the longitudinal Politicisation Project) that both suggest that the SIMCA needs to be extended to include, both conceptually and empirically, a broader range of (violated) moral beliefs and a focus on identity content. We discuss key implications of expanding the core of the SIMCA for the social psychology of collective action and social change, and suggest new directions for future theorising and research in this field.

The socio-psychological phenomenon of collective action, commonly defined as any action that individuals undertake as group members to pursue group goals such as social change (Van Zomeren, Citation2016a), has become an international and systematic focus of social-psychological research. Over the last 10 years or so, many articles have been published that report studies on collective action, often focused on its narrower meaning of social protest, conducted in a wide range of countries around the world (see Van Zomeren & Louis, Citation2017). The broad popularity of the topic may very well be inspired by recent international events and developments, ranging from the “Arab Spring” protests to the emergence of movements like Occupy Wall Street. Indeed, given that many seem to believe that undertaking collective action increases chances of social change, studying what moves and motivates people to engage in such action is both academically and societally relevant, as such an expression of human agency may change the social structure in which individuals are embedded.

The social-psychological literature has gone through an integrative phase that has helped to create a blueprint of which core motivations are likely to be relevant to disadvantaged group members’ engagement in collective action (e.g., Klandermans, Citation1997; Mummendey, Kessler, Klink, & Mielke, Citation1999; Simon et al., Citation1998; Van Zomeren, Postmes, & Spears, Citation2008). This has resulted in a number of integrative and testable models of core motivations for collective action (Becker & Tausch, Citation2015; Becker, Tausch, & Wagner, Citation2011; Drury & Reicher, Citation2005, Citation2009; Subašić, Reynolds, & Turner, Citation2008; Tausch et al., Citation2011; Thomas, Mavor, & McGarty, Citation2012; Van Zomeren, Citation2013, Citation2016a). Our point of departure is one such integrative model, namely the Social Identity Model of Collective Action (or SIMCA for short; Van Zomeren, Postmes, & Spears, Citation2012). Grounded in a meta-analysis of the social-psychological literature (Van Zomeren et al., Citation2008), this model proposed that group identification (i.e., individuals’ psychological ties with the relevant group), group efficacy beliefs (i.e., individuals’ beliefs that the group is able to achieve group goals through unified effort), and perceived or felt group-based injustice (i.e., individuals’ perceptions of unfairness or experience of anger about the group’s disadvantage) are unique and positive predictors of individuals’ willingness to and engagement in collective action. In this view, group identification, and in particular its politicised version (e.g., identification with a social movement), is a particularly important variable because it predicts collective action directly, but also predicts the other two motivations for collective action. This explains the centrality of the social identity concept in the model’s name and reflects a group identity-based, rather than individual instrumentality-based, “logic of collective action” (Olson, Citation1967).

However, there are good reasons to believe that (politicised) group identity is often intertwined with moral motivations for collective action – the motivation to protect one’s moral beliefs by fighting for what one stands for, or will certainly not stand for. Consider, for example, how individuals may engage in collective action when the announcement of a travel ban for Muslims violates their moral beliefs about social equality. Such an example resonates with a more recent suggestion to extend the SIMCA by including moral conviction – that is, individuals’ feelings that their stance on a particular issue reflects their core beliefs about right and wrong (e.g., Skitka, Citation2010). In this extended form of the SIMCA, moral conviction reflects a fourth, more distal predictor of collective action that reflects an individual difference variable that fuels the other three more context-dependent motivations, including (politicised) group identification (Van Zomeren et al., Citation2012).

In the current chapter, we move beyond this work by further extending the SIMCA. We specifically propose that the core of the SIMCA may be best thought of as consisting of both moral and identity motivations for collective action, thus integrating who “we” are with what “we” (will not) stand for. Conceptually, we connect these broader notions of moral beliefs and identity content through self-categorisation theory’s notion of normative fit (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, Citation1987; see also Livingstone, Citation2014; Reynolds et al., Citation2012; Subašić et al., Citation2008; Subašić & Reynolds, Citation2009), which we outline in more detail in the next section. Empirically, we illustrate the importance of such a broader view on collective action by reviewing two recent research projects that incorporate broader aspects of moral beliefs and (politicised) group identity into the social psychology of collective action. Together, these projects demonstrate that the SIMCA may currently be missing important variables and insights because of the overly restrictive operationalisation of moral motivation as moral conviction (Van Zomeren et al., Citation2012; Van Zomeren, Postmes, Spears, & Bettache, Citation2011), and of group identity as group identification (as is common in the field; see Turner-Zwinkels, van Zomeren, & Postmes, Citation2015). Consistent with the broader notion of normative fit, we suggest that the SIMCA should therefore be extended with a broader array of moral beliefs (e.g., values, rights, moral convictions), and with the notion of identity content (particularly when it comes to politicised group identities). As such, the current chapter moves beyond previous conceptual and empirical work (e.g., Becker & Tausch, Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2012; van Zomeren et al., Citation2013).

Against this backdrop, the roadmap for the chapter is as follows: The first section proposes how the SIMCA can be extended by incorporating a broader set of moral beliefs and identity content through the conceptual notion of normative fit. The second section reviews two recent research projects (the Value-Identity Fit Project: Kutlaca, van Zomeren, & Epstude, Citation2016; Citation2017; Mazzoni, Van Zomeren, & Cicognani, Citation2015; and the Politicisation Project: Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2015; Turner-Zwinkels, Van Zomeren, & Postmes, Citation2017) that generally support this line of thought. The third and final section identifies implications of extending the SIMCA, as proposed in this chapter, for the social psychology of collective action.

Extending the SIMCA further

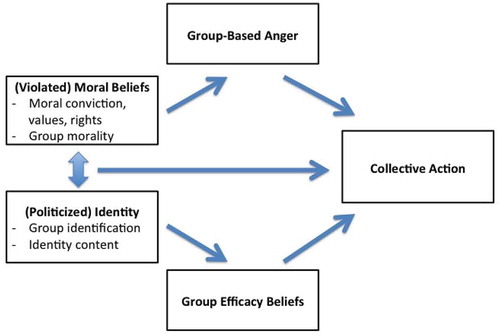

To date, the moral and identity motivations for collective action have been considered as separate variables from different literatures, rather than as the twin core of the SIMCA, thereby separating what “we” stand for from who “we” are. In this first section, we propose that the essence of the model is not just about group identity, but also about moral beliefs that individuals perceive to be violated, and that the notion of normative fit explains why the two are closely connected in the context of collective action. visualises what the SIMCA would look like when extended further along these lines.

Figure 1. Extending the SIMCA further through a broader set of (violated) moral beliefs and (politicised) identity content.

From (politicised) group identification to identity content

Group identification lies at the heart of the SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., Citation2008, Citation2012), as it predicts collective action directly and indirectly (i.e., through the other two predictors). This is because group identification relates to individuals’ ability and motivation to perceive, feel and act as psychological group members, rather than isolated individuals (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Indeed, identification with a group implies that individuals perceive themselves in group terms (e.g., “we” and “us”, rather than “I” and “me”), particularly in contrast to others in their social world (e.g., “them”). As such, higher identifiers with the group are more likely to think, feel and act for the group. In the context of collective action, identification with a politicised group (e.g., a social movement or activist group) is particularly important because, unlike broader and vaguer group identities, a politicised identity includes clear normative and action-oriented meaning (Klandermans, Citation2014; Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001; Stürmer & Simon, Citation2004). For example, Becker and Wagner (Citation2009) showed that identification with women means very different things depending on the content assigned to the category (e.g., traditional women or feminists). Nevertheless, collective action researchers focus almost exclusively on group identification (Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2015).

This is of course not to downplay the importance of group identification. Obviously, in order to act on a social identity it helps to identify to at least some extent. Indeed, a key reason why the SIMCA assigns such a central role to social identity is that it also facilitates individuals’ group-based emotional experience of injustice (i.e., group-based anger) and their beliefs in the group’s efficacy to achieve group goals, both of which uniquely predict collective action. Group-based anger is based in the group-based perception of injustice, but its emotional experience adds unique motivational power to do something about the injustice (e.g., Van Zomeren, Spears, Fischer, & Leach, Citation2004). In a similar vein, group efficacy motivates collective action because it reflects individuals’ beliefs that their group is able to achieve its goals through collective action (Bandura, Citation1997; Hornsey et al., Citation2006; Mummendey et al., Citation1999). Group efficacy beliefs focus on the group as the agent of social change, and those who hold them subscribe to the idea that, through joint effort and as a group, they can achieve relevant goals (e.g., “yes we can!”; Van Zomeren, Leach, & Spears, Citation2010; see also Cohen-Chen & Van Zomeren, Citation2018). By considering social identity (rather than personal identity) as the psychological basis for collective action, and by measuring group identification to this end, the central place of social identity in the model is not surprising.

Furthermore, this approach has fared rather well empirically. The SIMCA, with (politicised) group identification at its core, has received a fair amount of support from studies with participants from different countries and cultures, and in relation to collective action against or for very different issues. For instance, major parts of the SIMCA received support in the context of Blacks’ and Whites’ motivation to protest in South Africa (Cakal, Hewstone, Schwär, & Heath, Citation2011); among Lebanese religious groups (Tabri & Conway, Citation2011); among Spanish students, citizens and protesters (Sabucedo, Dono, Alzate, & Seoane, Citation2018); among activists and non-activists in the “Ferguson” context in the US that later turned into the Black Lives Matter movement (Wermser, van Zomeren, Pliskin, & Halperin, Citation2018); among different “third groups” in the context of intergroup conflict (Klavina & Van Zomeren, Citation2018); and as applied to voting intentions in three different national elections (Van Zomeren, Saguy, Mazzoni, & Cicognani, Citationin press). As such, the SIMCA seems to be in a fair position to claim a certain level of generalisability (i.e., external validity).

Nevertheless, identity content remains neglected in research on collective action, notwithstanding the lip service paid to its presumed importance. In fact, Van Zomeren et al. (Citation2008, p. 522) reflected on their meta-analysis by, perhaps somewhat ironically, suggesting that: “Ultimately, it may not necessarily be social identity or identification per se that prepares people for collective action, but rather the content of social identity.” Similarly, Simon and Klandermans’ (Citation2001) insightful analysis of what politicised identities are and how they develop basically entails an analysis of changing identity content. The empirical research that followed, however, simply operationalised politicised identity – evinced when “they engage as self-conscious group members in a power struggle on behalf of their group knowing that it is the more inclusive societal context in which this struggle has to be fought out” (Simon & Klandermans, p. 319) – by asking individuals about their identification with the relevant group. Thus, identity content is too often assumed but not assessed, and interpreted but not actually tested. As such, we know to what extent participants identify as social movement members, but not what this means to them and how this fits within the broader social psychology of collective action.

This practise severely limits our understanding of (politicised) identity in the context of collective action. Conceptually, we concur with Reynolds and colleagues (Citation2012, p. 257, emphasis added), who wrote that: “… strength of identification with a particular group indicates the psychological importance (ongoing cognitive and emotional significance) of the group to the individual. Salience relates to whether a particular group membership is psychologically operative or self-defining at the time of interest […]. Neither salience nor identification, though, provides information about the content (e.g., stereotype) of being a group member.” As such, a focus on (politicised) identity content may offer new insights into what it means to be part of “us”. In fact, we suggest that this is particularly relevant when considering what “we” stand for in terms of moral beliefs.

From moral convictions to moral beliefs (and their violation)

We propose that who “we” are and what “we” stand for are closely connected in the context of collective action. As such, in addition to focusing on identity content we suggest that the SIMCA should focus on moral beliefs more broadly (including but not restricted to moral conviction). Indeed, moral beliefs may refer to the normative part of individuals’ politicised identity (i.e., its normative content), which also seems to fit nicely with the importance of perceived injustice and felt anger in predicting collective action. Indeed, the SIMCA’s emphasis on individuals’ perceptions and experiences of group-based injustice originally did not include a differentiation between what people consider merely unfair and what they consider immoral (e.g., protests against student tuition fees, or against abortion). Van Zomeren et al. (Citation2012) argued that this differentiation is not trivial because individuals who moralise the issue at hand are likely to be motivated to protect and defend these moral beliefs (Skitka, Citation2010). Including this moral dimension further implied that even members of advantaged groups may engage in collective action as long as this is grounded in moral beliefs that resonate with their (politicised) identity (Van Zomeren et al., Citation2011). This culminated in the operationalisation of moral beliefs as moral conviction in the extended SIMCA – that is, individuals’ strong and subjectively absolutist belief about what is right and wrong, which is experienced as a non-negotiable, self-evident fact about the world (Skitka, Citation2010).

In line with these ideas, the extended SIMCA received support across different collective action contexts (see Van Zomeren, Citation2013), suggesting that moral convictions (e.g., about group-based discrimination) have a particularly strong link with politicised identities (e.g., identification with a social movement), which are assumed to be clearly normative and action-oriented in their content. Furthermore, this work assumed (but did not test) that individuals often respond to perceived violations of their convictions, which triggers a strong need to protect them (Skitka, Citation2010), for instance through collective action.

However, the notion of moral conviction offers just one rather strong and issue-specific operationalisation of moral beliefs (e.g., about abortion, capital punishment, racial discrimination). Taking a broader view, we suggest that the same process of value protection should be at play for different operationalisations of moral beliefs. For example, whereas moral convictions are issue-specific, other forms of moral beliefs may reflect values that transcend specific issues and situations (e.g., Schwartz, Citation1992; Schwartz & Bardi, Citation2001). We therefore suggest that our line of thought applies to a broader set of moral beliefs than just moral conviction, and that it argues for a broader view on what “we” stand and will not stand for, particularly when connecting this to who “we” are in terms of politicised identity.

Finally, our line of thought extends into the realm of moralised evaluations of the group and its members (i.e., as trustworthy, sincere and reliable). Indeed, when individuals engage in collective action to protect what they stand for and who they are, then in-group members may be more likely to be perceived as similar in terms of being people with moral character who can be expected to show commitment to both the group and its cause (and have the moral high ground). This fits nicely with insights from the literature on perceived group morality (e.g., Ellemers, Pagliaro, Barreto, & Leach, Citation2008; Leach, Ellemers, & Barreto, Citation2007), and with the importance of perceived emotional and instrumental social support from in-group members in the context of collective action (e.g., Citation2012; Van Zomeren et al., Citation2004). Put differently, knowing who you are and what you (will certainly not) stand for may imply having strong expectations of fellow in-group members: You need to expect them to be reliable, trustworthy, sincere, and, above all else, moral.

Integrating moral beliefs with (politicised) identity

Conceptually, the normative fit principle helps us to extend the SIMCA by pointing to a broader array of moral beliefs, and to the importance of identity content. The notion of normative fit derives from self-categorisation theory (Turner et al., Citation1987) and is defined as the extent to which the perceived behaviour or attributes of a collection of individuals conform to the perceiver’s knowledge-based expectations (Oakes, Haslam, & Turner, Citation1994). As such, social “category specifications account for context-specific behaviours (i.e., normative fit)” (Hogg & Terry, Citation2000, p. 125), which makes it easier for individuals to self-categorise and identify with the relevant group.

In our view, this rather abstract link between “category specifications” and “context-specific behaviour” translates, in the context of collective action at least, into (violated) moral beliefs that require collective action to achieve social change. As people self-categorise on the basis of such a normatively fitting category, the category is imbued with self-relevance and thus speaks to identity and the motivation to act in line with this identity (e.g., Van Zomeren et al., Citation2012). To illustrate, if one perceives racial discrimination as a violation of one’s moral beliefs (e.g., one’s moral convictions, values, or rights), then after witnessing an instance of police brutality against Blacks one may self-categorise as part of a normatively fitting group that will not stand for racial discrimination (e.g., Black Lives Matter). It follows that it is difficult to understand the normative fit principle without reference to (violated) moral beliefs and identity (content). It also follows that there is no a priori reason why moral beliefs need to be restricted to moral conviction, and why social identity needs to be restricted to group identification.

Furthermore, the dynamic and context-dependent nature of self-categorisation processes (Turner et al., Citation1987; see also Goldenberg, Halperin, Van Zomeren, & Gross, Citation2016; Van Zomeren et al., Citation2012) fits well with why we propose that perceived violations of individuals’ moral beliefs (and thus their identity) are important contextual triggers for collective action. That is, although values and moral convictions no doubt have motivational power in and of themselves (e.g., Schwartz & Bardi, Citation2001; Skitka & Bauman, Citation2008), the perceived violation of values or convictions motivates people to protect that value or conviction (see also Tetlock, Citation2002; Tetlock, Kirstel, Elson, Green, & Lerner, Citation2000). As such, the perception of value violation (e.g., the announcement of a travel ban for certain groups) creates or makes salient social categories on the spot – that is, either one is with or against “them”. McGarty, Bliuc, Thomas, and Bongiorno (Citation2009) have termed the identities that follow from this opinion-based groups, but our focus on violated moral beliefs and identity content suggest that there is something more than mere opinion to such identities – these are moralised as well as politicised identities, and people are motivated to act on such identities in order to protect who they are, as this resonates with what they stand for and will certainly not stand for.

In sum, our view is that the normative fit principle integrates the moral and identity motivations for collective action in a way that extends the SIMCA. Below, we review two recent research projects that, taken together, support this line of thought. First, the Value-Identity Fit Project aimed to examine whether and how (perceived violations of) moral beliefs (operationalised as values and rights) normatively fit with different group identities on which to act collectively. Whereas this project focused on group identification rather than on identity content, the Politicisation Project aimed to zoom in on (politicised) identity content in the context of collective action. Both projects included the development of new measures of violated moral beliefs and identity content, which enabled us to move beyond the focus in the field on moral conviction and group identification. Below we discuss each project in detail in turn, after which we discuss the key implications for extending the SIMCA and the social psychology of collective action more generally.

The value-identity fit project

The Value-Identity Fit Project aimed to increase our understanding of the psychological processes through which individuals’ values and rights, as different operationalisations of moral beliefs, fit with specific group identities that can provide a basis for collective action. Prior research has mostly examined the strength of value endorsement as a predictor of political behaviour (Schwartz, Caprara, & Vecchione, Citation2010; Skitka & Mullen, Citation2002; Tetlock et al., Citation2000). However, people often fail to act upon their values and sometimes even act in ways that transgress their most important principles, as demonstrated by research on moral licensing (Merritt, Effron, & Monin, Citation2010), human rights protection (Cohrs, Maes, Moschner, & Kielmann, Citation2007; Staerklé & Clémence, Citation2004), and discrimination (Dovidio & Gaertner, Citation1998). One of the reasons for this inconsistency may be that values operate as abstract principles, whereas behaviours are more concrete and situation-specific (Maio, Citation2010; Maio, Hahn, Frost, & Cheung, Citation2009).

This is important because value protection models (e.g., Skitka, Citation2002; Skitka & Mullen, Citation2002; Tetlock, Citation2002; Tetlock et al., Citation2000) suggest that perceived violations of values (e.g., discriminating against people on the basis of race or gender) motivate individuals to protect them, and thus bridge any potential gap between more abstract values and behavioural manifestations of protecting these values. Put differently, knowing what you stand for may not have the same motivational urgency as knowing what you certainly will not stand for, given a contextual trigger that violates your moral beliefs (e.g., a travel ban, a situation of police brutality). Therefore, the first goal of the Value-Identity Fit Project was to test whether people are more likely to identify with normatively fitting groups and engage in collective action when they perceive the disadvantaged situation more as a violation of a specific value (e.g., social justice). As such, within this project we used the term value-identity fit as a more specific form of the normative fit principle, referring to both values and perceived rights.

We examined value-identity fit in three subprojects. First, Mazzoni et al. (Citation2015) investigated whether the perceived violation of a specific human right predicted identification with the Italian Water Movement (i.e., politicised identification). Second, we tested in a context in which movements were absent (i.e., the context of gas-extraction-induced earthquakes in Groningen, the Netherlands) whether such a perceived violation helped to define otherwise unpoliticised identities in a way that motivated collective action (Kutlaca et al., Citation2017). Finally, we moved beyond the motivational meaning of value-identity fit by examining whether the communication (or framing) of value violations and relevant group identities by social movements can create value-identity fit or misfit, and as a consequence has motivating or demotivating effects on individuals (Kutlaca et al., Citation2016). We studied this in the context of a student movement protesting against the introduction of a study loan system for students in the Netherlands.

Subproject 1: the Italian water movement

The first subproject tested the idea that individuals’ perceived value violation reflects the “active ingredient” of the moral motivation to engage in collective action (i.e., value protection). In line with the notion of normative fit, our hypothesis for the first subproject was thus that perceived value violations motivate collective action through politicised identification. We conducted two survey studies (one with activists and one with a broader sample of Italian citizens) in the context of The Italian Water Movement campaigning against liberalisation of national water resources in Italy (“Water is not for sale”; for more details, see Mazzoni et al., Citation2015). According to the United Nations, access to safe and clean water is considered to be a basic human right (CESCR, Citation2002), and the recent trend towards privatisation of water resources in developed countries can be seen as a violation of this right. This context enabled a test of whether the perceived violation of this right to water motivates individuals to identify with the movement and engage in actions to protect public water resources.

We developed and used a new measure of perceived right violation. This construct was operationalised and measured as a multiplicative index of two components: a) the perceived importance people attach to the right to water (e.g., “Even in a period of economic crisis, how necessary is it that everyone will have access to a minimum quantity of water for personal and domestic use?”), and b) the perceived threat of violation (e.g., “Without substantial law changes, how probable is it that we will face the following violations of the right to water?”, with one sample item being: “Someone will have no access to a minimum quantity of water for personal and domestic uses.”) The findings from multivariate regression analyses showed that, across the two studies with Italian activists (Study 1, N = 151) and general public (Study 2, N = 132), individuals’ perceptions of the violation of the right to water positively predicted their identification with the movement; furthermore, stronger identification predicted individuals’ participation in future intentions to engage in collective action through identification with the Water Movement. These findings support the notion of a normative fit between, in this case, a perceived violation of rights and an existing politicised identity.

Visual overviews of the findings of Studies 1 and 2 can be found in and (for the associated correlation matrices and other descriptive statistics, see Mazzoni et al., Citation2015). shows that, among Italian activists, perceived right violation predicted movement identification, which in turn predicted self-reported intentions of future activism. Importantly, in Study 2 we included moral conviction about the issue in question (i.e., the privatisation of water services), which enabled a comparison between perceived right violation and moral conviction. shows that, among a broader sample of Italian citizens, and in line with Study 1, individuals’ perceived right violation positively predicted their movement identification, and that this effect held when controlling for moral conviction (which had an independent effect). Movement identification again predicted self-reported activism intentions. Together, these findings suggest that both moral conviction and perceived right violation are relevant and distinct operationalisations of moral beliefs that normatively fit the relevant politicised identity in this context.

Figure 2. Perceived right violation predicts movement identification. Reprinted with permission from Mazzoni et al., (Citation2015, Study 1) in Political Psychology 36, 315-330, © 2015 John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 3. Perceived right violation predicts movement identification. Reprinted from Mazzoni et al., (Citation2015, Study 2) in Political Psychology, 36, 315-330, © 2015 John Wiley & Sons.

Subproject 2: the Groningen earthquake context

The second subproject of the Value-Identity Fit Project made use of a context in which no clear action-oriented social movement was present. This allowed us to test the same hypothesis as in the previous subproject, but in a context where a politicised identity was unavailable in social reality and could only be constructed, as it were, on the spot. We tested whether perceived right violations can create a normative fit with otherwise unpoliticised group identities and through identification with this group motivate collective action.

This context concerned gas-extraction-induced (and thus “human-caused”) earthquakes in the northern province of Groningen in the Netherlands (Kutlaca et al., Citation2017). For the past 60 years, gas extraction has been an important source of income for the Netherlands, but it is also the main cause of mild earth tremors, which was acknowledged nationally only after a more powerful earthquake took place in 2012 (Dost & Kraaijpoel, Citation2013; Van der Voort & Vanclay, Citation2015). We surveyed, door-to-door, inhabitants of the province of Groningen just before an important political decision about the future of gas extraction was made in 2014. Hence, engaging in collective action at that moment could have had an impact on policy-makers. However, those actions need to be organised bottom-up, since there was no single strong movement representing the interests of those hit by these earthquakes through top-down mobilisation.Footnote1

According to available geological maps of the province based on the intensity of these shallow earthquakes (Dost & Kraaijpoel, Citation2013), we selected 9 towns and villages situated in the most, the moderate and the least objectively affected areas. This enabled us to test whether this difference in objective exposure to actual earthquakes also shaped individuals’ views of the situation and their motivations to act collectively.

Participants (N = 351) were asked about the extent to which the gas-extraction-induced earthquakes violated their basic human right to safe existence, which fitted with the local discourse in this context on this issue (more specifically as the perceived violation of physical safety, health and financial stability; e.g., “I see the earthquakes as a violation of my safety and/or the safety of my family”). Importantly, we differentiated between the right violation reflecting participants’ personal experiences (including those of their family) of the earthquakes, and the right violation reflecting a concern for other inhabitants of the broader province of Groningen (which reflected a consideration of the rights of the broader group). We suspected that perceived right violations based in individual or group identities potentially reflect different pathways to collection action: through bottom-up projection of individual values (i.e., to protect the rights of “me and mine”) vs. top-down conformity to group values and norms (i.e., to protect the rights of the broader group or social category).

Multiple regression analyses indicated that, across the board, identification with the disadvantaged group (i.e., inhabitants of the earthquake region) was positively predicted by perceived right violations fitting “me and mine” (B = .19, SE = .09, t(257) = 2.08, p = .039), and fitting the broader group (B = .48, SE = .12, t(257) = 3.92, p < .001), across the three different areas. But, as shows in the most affected areas, only individuals’ perceived right violations fitting “me and mine” motivated collective action intentions (B = .47, SE = .22, t(238) = 2.12, p = .035); whereas in the least affected areas, individuals’ perceived right violations fitting the broader group motivated collective action intentions (B = .49, SE = .18, t(238) = 2.74, p = .007). These findings support the idea that, in the most affected areas, a bottom-up projection of perceived right violations motivated collective action intentions. By contrast, a top-down conformity to perceived right violations seemed to facilitate such intentions in the least affected areas. Thus, in both areas we observed manifestations of value-identity fit, even in a context where politicised identities were not available.

Figure 4. The impact of personal/family and collective right violations on collective action intentions in the most and the least affected areas. Reprinted from Kutlaca et al. (Citation2017) with permission from Environment and Behavior, © 2017 SAGE Publications Inc.

Subproject 3: the Dutch student movement context

The final subproject of the Value-Identity Fit Project tested whether perceived value violations can be used as effective mobilisation tools (Kutlaca et al., Citation2016). This might be the case, according to our line of thought, as long as the perceived value violation normatively fits with the relevant (politicised) identity (Mazzoni et al., Citation2015), and thus communicates that who we are resonates with what we stand for. Furthermore, if perceived value violations can be used as a powerful tool to create shared identities even in the absence of social movements (Kutlaca et al., Citation2017), the notion of value-identity fit may also be important when communicating or framing mobilisation campaigns (e.g., Snow, Rochford, Worden, & Benford, Citation1986). This is an important practical question to address because in order to gather the support of many people, movements need to successfully communicate who they are and what they (will certainly not) stand for.

When it comes to communication, value-identity fit therefore has to apply to the particular audience that the movement aims to mobilise. However, members of the same group (e.g., women) may endorse completely opposing values and norms (e.g., traditional vs. progressive gender roles). We therefore focused on two different audiences within the same group so that we could study both value-identity fit and misfit. We reasoned that communicating a value-identity fitting message should appeal to, or resonate with, those in the group who already share the movement’s ideological background (Gamson, Citation1992; Klandermans, Citation1997). However, communicating the very same message to those in the group with a different ideological background (Guy, Citation2011; Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, Citation1994) would actually be more likely to be a misfit, which might backfire or at least fail to motivate individuals to engage in collective action.

Our research was set in the context of a large student protest against budget cuts for higher education in the Netherlands in 2011/2012, just before the government was supposed to impose fines on ‘lazy’ students. These budget cuts were perceived by some as an instrumental form of collective disadvantage, and by others as a violation of the right to free education. In a pilot study (N = 98), we first identified two student groups (social science vs. economics students) whom we suspected to be more vs. less supportive of the protests because of their different ideological backgrounds (e.g., social science students are more left wing, on average, than economics students). In the experiment (N = 181), we verified that these two groups had different ideological backgrounds and we randomly assigned participants to one of the four conditions in which we manipulated whether or not the budget cuts were framed as a violation of the right to free education, and whether these values were important to students or to all Dutch people (e.g., “Modern Dutch society is based on the principles of freedom and equality” vs. “Most students value the principles of freedom and equality”). Hence, with a simple reformulation we embedded the right violation in different identities (disadvantaged group identity vs. national identity). To be able to assess the mobilising effects of value violation over and above the collective disadvantage, we also included a condition in which we mentioned the effects of the cuts for students (without mentioning the right to free education), and a control condition in which the participants only filled out the dependent variables. We then measured participants’ intentions to participate in collective action (e.g., signing a petition, participating in a demonstration), their politicised identification (e.g., “I identify with the students who oppose these measures”,), national identification (e.g., “I identify with Dutch society”), and their perceptions of injustice (e.g., ”How fair are the austerity measures placed upon students?”) and group efficacy beliefs (e.g., “I think that students, as group, can stop budget cuts”) as different motivations for collective action.

We tested for both direct effects of value-identity communication (i.e., mean-level changes in politicised identification and motivation to act as a consequence of the specific message), and indirect effects or changes in the processes predicting politicised identification and action (i.e., changes in the relative predictive weight of specific motivations). We hypothesised that communicating values and politicised identities to those who share the movement’s ideological background is like “preaching to the choir” – these individuals already perceive their values as being violated, and reminding them of this may not add much motivation to act in terms of direct, mean-level changes. However, we anticipated indirect effects of value-identity communication for this audience, as previous research suggested, for example, that for those mobilised by value-based movements, perceived injustice is the most important predictor of motivation for collective action (Van Stekelenburg, Klandermans, & van Dijk, Citation2009). Therefore, we expected injustice perceptions (as opposed to more instrumental efficacy concerns) to be more predictive of politicised identification and action intentions for this particular audience.

This should be quite different, however, for those who do not belong to the movement’s “choir”, because communicating values to those who do not share them (i.e., value-identity misfit) is more likely to backfire. In line with the notion of normative fit, values need to be embedded in the group identities that this particular audience cares about. Because those who do not share the ideological background of the movement are also less likely to identify with it, trying to fit the movement’s values to the disadvantaged group’s identity might be ineffective. A potentially more successful way to attract this audience is by embedding values in a superordinate identity, such as national identity (see Reynolds et al., Citation2012). Indeed, research on recategorisation (e.g., Turner et al., Citation1987; see also Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, Citation1993), dual identification (Simon & Ruhs, Citation2008) and politicisation (Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001) suggests that aligning the disadvantaged group’s values and identities to a superordinate national identity may increase the movement’s mobilisation potential.

The findings bore out our predictions. In terms of direct effects, among social science students, communicating value violation irrespective of the identity emphasised in the mobilisation call increased neither politicised identification nor collective action intentions. In terms of indirect effects, we found clear support for the value-identity fit notion: shows that, among social science students, communicating value violation (in contrast to control conditions) increased the importance of perceived injustice as a predictor of politicised identification – a motivational signature of higher identifiers with the group (Van Zomeren et al., Citation2008).

Figure 5. The impact of perceived injustice (or affective motivation) on politicised identification among social science students when the value violation has been communicated as important to all Dutch people (Value-National Condition) or has not been communicated at all (Context-Only Condition). Reprinted from Kutlaca et al. (Citation2016) with permission from Social Psychology 2016; Vol. 47(1):15–28. © 2015 Hogrefe Publishing.

For the economics students, we found a hint of value-identity misfit at the direct level: Communicating value violation and disadvantaged group identity actually decreased their perceptions of injustice, compared to other conditions (Mvalue-studentid = 3.53, SD = 1.10 vs. Mvalue-nationalid = 4.14, SD = 0.87 vs. Mcontext = 4.37, SD = 1.06 vs. Mcontrol = 4.38, SD = 1.20, F(3, 79) = 2.67, p = .053, η2p = .09). However, for economics students we found a positive effect of fitting the value violation to national identity (Simon & Ruhs, Citation2008): National identification became a significant positive predictor of politicised identification when the communication emphasised the violation of the right to education as being important to all Dutch people (β = 0.51, t(73) = 2.26, p = .027). The opposite was true when the communication emphasised the disadvantaged group identity (β = − 0.37, t(73) = − 1.57, p = .12), which offers an important pointer to the potential of value-identity fit as a tool for movement mobilisation.

Three lessons from the value-identity fit project

The findings of the three subprojects of the Value-Identity Fit Project have three important implications for the role of the moral motivation for collective action in the extended SIMCA. First, findings are in line with the idea that the normative fit principle does not need to be restricted to moral convictions, as suggested in the SIMCA. Instead, it seems that the special relationship between moral and identity motivations applies to broader moral beliefs such as values and rights. Second, these findings confirm that the perceived violation of moral beliefs is an active ingredient in the moral motivation to engage in collective action (i.e., value protection; Van Zomeren, Citation2013). Indeed, the perceived violation of moral beliefs instigates the motivation to protect these beliefs, and thus transform the more abstract value and rights into a more concrete, situation-specific behavioural manifestation. Third and finally, the findings suggest various motivational consequences of value-identity fit and misfit, ranging from how perceived right violations positively predict politicised identification (Mazzoni et al., Citation2015), to how perceived right violations positively predict identification with more abstract groups and directly motivate action in the absence of social movement organisations (Kutlaca et al., Citation2017), and to how communication of violated values and identities increases politicised identification among ideologically different subgroups (Kutlaca et al., Citation2016).

However, across all the studies we reviewed in this project, we operationalized (politicised) identity as group identification (i.e., identity strength). Because the normative fit principle explicitly embodies identity content, we now turn to the Politicisation Project, in which we developed a new measure of identity content in order to better quantify and understand the meaning individuals ascribe to their (politicised) identities in the context of collective action.

The Politicisation Project

This project aimed to gain a greater understanding of the content of the relevant (politicised) identity that sits at the heart of the extended SIMCA. As such, we wanted to gather deeper empirical insights into the meaning that individuals ascribe to politicised identities and its normative fit with moral beliefs. To this end, we focused on the building blocks of individuals’ beliefs about the meanings of political groups, that is, on their identity contents (i.e., defined as the semantic space associatively related with an identity, comprising one’s self- and group-definitions; Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2015, Citation2017).

A focus on identity content is important as the process of politicisation is often argued to reflect a qualitative transformation of identity, through which sympathisers come to see themselves as activists (Cross, Citation1971; Duncan, Citation2012; Klandermans, Citation2014; Livingstone, Citation2014; Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001; Subašić et al., Citation2008). However, to our knowledge no quantitative research to date has tracked and tested this process, possibly because group identification alone, as a quantitative measure of change in the strength of one’s identity, cannot capture these qualitative changes (Livingstone, Citation2014). For instance, if someone identifies strongly as a woman, this will not tell us whether this means a traditional or modern view on womanhood (Becker & Wagner, Citation2009). We thus need to know about identity content to interpret what it means to be part of “us”, and we therefore need a conceptualisation as well as a measure of identity content.

There are already pointers in the literature to suggest that identity content is important in predicting collective action. For example, politicised identification (i.e., identifying with a social movement) is a stronger predictor of collective action than identification with the broader disadvantaged group (e.g., Stürmer & Simon, Citation2004). We believe that this is precisely because of different identity content (i.e., different group meanings and definitions), which differentially embodies who they are and what they (will not) stand for. For instance, a feminist identity already encompasses ideological and political content geared towards wanting to achieve social change via collective action (e.g., Duncan, Citation2012; Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001). As such, identification with feminists would include endorsing this content and action readiness, whereas such content should be much weaker (and thus endorsed much less) in the case of the broader identity.

Indeed, the key reason why politicised identity is so important in predicting collective action is that its content normatively fits with, and perhaps already prepares for, collective action: Knowing who we are and what we stand for also implies knowing what to do, particularly when our moral beliefs are under siege. However, no research to date has empirically explored the qualitative characteristics that define and differentiate politicised identities, thus revealing what makes them such strong motivators of collective action. Conceptualising and measuring identity content, we believe, will help to shed light on such unanswered questions.

Below, we review two research projects that both used longitudinal data in the time frame of the 2012 US presidential elections – a type of political context in which individuals can become active party members during the campaign, and thus become politicised. This fits with our interest in exploring changes in identity content within individuals over time, a focus that strongly aligns with theoretical representations of politicisation as a process of qualitative transformation (Cross, Citation1971; Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001).

Each subproject focused on distinct aspects of identity content. The first subproject (Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2015) examined how politicised identity content becomes integrated with one’s personal identity when an individual comes to see him- or herself as an activist. By contrast, and connecting directly with the notion of normative fit, the second subproject (Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2017) explored more specifically whether moral content might be more important than non-moral content in defining politicised identities. Together these two lines of work aim to show how changes in identity content reflect psychological changes in how non-activists become activists (i.e., the politicisation process), and how moral identity content differentiates politicised from unpoliticised identities, suggesting that who we are and what we stand for are closely linked in the context of collective action.

Subproject 1: when the political becomes personal

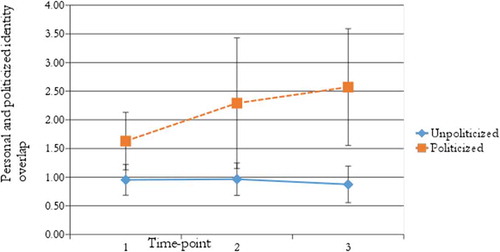

In this subproject (see Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2015, for details), we investigated U.S. citizens’ politicisation (i.e., switching from not self-defining to self-defining as a party activist, defined as group of people who aim to promote the party the participant supported to win them votes). To do so, we collected longitudinal survey data from a community sample of US citizens on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Specifically, we tracked whether and how the fit between personal and politicised identities developed over the course of the elections by measuring the identity content (for both identities) two months before (T1), immediately before (T2), and two months after the elections (T3).

In order to track the process of politicisation, our analysis focused on a subsample of politicising party activists, and explored how their identity contents differed from non-activist passive party supporters. Specifically, from a total sample of 760 individuals we selected a subsample of 115. Eighty-seven participants were passive party supporters, that is, unpoliticised individuals who voted in the elections but consistently self-labelled as a non-activist across the election period (i.e., T1-T3). The other 28 participants were politicising party activists who self-labelled as a non-activist at the start of the elections (T1), but later politicised to self-label as a party activist by the end of the elections (T2 or T3). Therefore, while all participants were politically active in the sense that they voted in these elections, only a unique, smaller subgroup politicised to become party activists during the election.

To effectively measure the (change in) qualitative fit between personal and politicised identities, we used an associative recall task (ART). This task allows individuals to freely list up to 20 different words (e.g., “determined”) or concepts (e.g., “good in moments of crisis”) that they associated with their personal identity (i.e., the unique me) and politicised identity (i.e., party activists for the party they supported). Our key dependent variable was a count of the absolute amount of overlap (i.e., words/concepts that were repeated) between the personal and politicised identity.Footnote2 This overlap can be considered as a form of normative fit between the content of politicised and personal identity, through which the political quite literally becomes personal, or more technically through which category specifications (e.g., loud) come to account for context-specific behaviours (e.g., chanting during a demonstration). Importantly, self-reported frequency of engagement in collective action promoting one’s party preference (e.g., by campaigning) was also measured. Our integration hypothesis was that the content of individuals’ personal and politicised identities would become more overlapping as individuals came to see themselves as party activists over time, and that such identity integration, in turn, would predict political activism as an indicator of collective action.

Importantly, by making use of individual’s freely, self-generated associations about their political and personal identity (e.g., “learning new things”, “integrity”, “someone who promotes liberty”, “concerned about others education”), the ART content data enriches our understanding of the group identity at the heart of the SIMCA in at least two ways. First, it allows us to tap into the perceived meaning of activist identities for each individual, without directing respondents towards any content preconceived by the researchers to be important. Second, it allows us to move away from the almost tautological link between identification as an activist and engaging in activism, which forms the basis of the identity–action link in the SIMCA.

Against this backdrop, our findings supported the integration hypothesis. shows that a repeated measures analysis of variance showed a significant time (T1 v. T2 v. T3) by group (passive party supporters v. politicising party activists) interaction effect (F(2, 202) = 3.48, p > .05), in addition to a main effect of group (F(1, 101) = 23.76, p > .001). For passive party supporters, there was no discernible development in the relation of their personal and politicised identities over time. For politicising party activists, however, we observed substantial changes: In line with the integration hypothesis, their personal and politicised identity content became more strongly overlapping over time. Follow-up statistical tests confirmed that small differences in overlap between politicising party activists and passive party supporters at T1 (t(111) = 2.41, p < .02) and T2 (just before the election; t (26.03) = 2.26, p < .04), became larger at T3 (two months after the election; t(24.21) = 3.17, p < .005).

Figure 6. Mean absolute amount of personal and politicised identity content overlap for politicised and non-politicised participants, over time. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the 95% confidence interval around the estimate. Reprinted with permission from Turner-Zwinkels et al. (Citation2015), Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41, 433-445, © 2015 Sage Publications Inc.

Moreover, further analyses showed that identity content overlap predicted both seeing the self (i.e., self-labelling) as a party activist, and intentions to undertake collective action. First, a logistic regression predicting self-labelling as a passive party supporter (0) or a politicising party activist (1) showed that this was positively and substantively predicted by greater overlap between personal and politicised identity content at T1 (B = 0.40, SE = 0.18, Exp = 1.49, p < .05). Second, a multiple regression predicting increase in frequency of self-reported action engagement at T2 (while controlling for T1 levels) showed that participants with greater overlap between personal and politicised identities at T2 also reported that they engaged in more collective action (β = .26, p < .01). These findings are of particular importance as they offer the first evidence on identity content and collective action.

Indeed, these results provide initial empirical support for the idea that politicisation is a process of qualitative change in the self-concept, and thus about identity content. Our results specifically suggest that as individuals became politicised, the fit between their personal and politicised identity content increased. This emphasises the importance of achieving such an increase in the fit between political and personal identities, so that political goals that were initially irrelevant to the unpoliticised became personal, and were taken on as self-relevant and put into action over time. In this way, our results suggest that politicisation is a psychological process of qualitative change, through which the political quite literally becomes personal.

Subproject 2: politicised identities are moralised identities

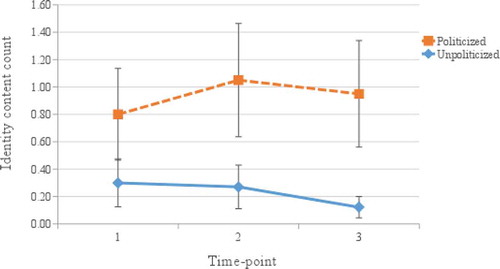

The second subproject of the Politicisation Project aimed to investigate which type of content differentiates politicised from unpoliticised identities (for details, see Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2017). Specifically, we compared the actual content of politicised and unpoliticised identities in order to address the question of whether politicised identities are more likely to be moralised identities (because of their presumed ideological meaning). Thus, our moral content hypothesis stated that activists’ politicised identities would contain more moral content than those of non-activists. By contrast, we did not expect any differences for non-moral dimensions of content (e.g., competence and warmth; Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, Citation2007). Furthermore, according to our moral overlap hypothesis, stronger moral overlap between the content of the personal and politicised identities would predict seeing oneself as a party activist and engaging in collective action.

We used the same longitudinal survey data collected in the US 2012 Presidential elections as in the first line of research, but selected a different subsample. Specifically, we selected 69 participants who consistently supported the Democratic Party across the three time points, and voted for them. Of these, 49 unpoliticised participants consistently self-labelled as non-activist, passive Democratic Party supporters, and the other 20 politicised participants consistently self-labelled as Democratic Party activists. This enabled a more precise comparison between the identity contents of stable politicised and unpoliticised identities.

All participants completed the associative-recall task for their personal and politicised identities. This content was coded for moral (e.g., trustworthy, sincere, reliable), competence (e.g., smart, intelligent) and warmth (e.g., kind, caring) content, using a coding scheme derived from expert definitions (e.g., Fiske et al., Citation2007). This meant that in addition to the absolute overlap count variable used in the previous subproject, we also derived three key, content-specific dependent variables counting the total number of moral words: (1) moral content counted within personal identity (e.g., I am trustworthy), (2) moral content counted within the politicised identity (e.g., Democratic activists are trustworthy), and (3) moral content counted overlapping across personal and politicised identities (i.e., if both identities were characterised as trustworthy). The latter measure of content overlap nicely feeds into the notion of normative fit, in this case between the moral content of personal and politicised identities.

We coded for moral content at both the individual and the group level of identity because such content concerns expectations about whom to trust and rely on in the context of collective action. Indeed, expecting others to share your values and convictions may enhance the predictability of your group members (a key basis of trust; Luhmann, Citation1979), implying that you can rely on them in times of need. This, in essence, is how group morality is defined in some approaches (Ellemers et al., Citation2008; Leach et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, when individuals share a moral conviction with an activist community that also takes action to protect the valued issue, then the group is likely to be seen as being more sincere and moral because they act in line with their belief (i.e., they have the moral high ground). The coding scheme we used was based on expert definitions used in the literature (and as such aligns with theoretical understandings of moral beliefs; e.g., Fiske et al., Citation2007). But more importantly, we applied this coding scheme to ART data spontaneously listed by participants without specific prompts to elicit moral beliefs. Thus, our dependent variables capture naturally emerging representations and/or presentations of group morality, as present in individuals’ identity content.

Our findings supported the moral content hypothesis. Firstly, as can be seen in , a 3 (time: T1 v. T2 v. T3) × 2 (group: politicised v. unpoliticised) repeated measures ANOVA showed that party activists recalled more moral content within their politicised identities than did passive party supporters, before, during and after the elections (F(1,67) = 34.73, p < .001; there was no main or interaction effect involving time, Fs(2, 67) < 1.66, ps > .20). Follow-up planned contrasts confirmed that party activists consistently recalled more moral content within their politicised identities across all three measurement points (ts(67) >2.67, ps < .02). Furthermore, repeated measures ANOVAs showed that party activists not only recalled more moral content within the politicised identity than did non-activists, but also more moral content within their personal identity (F(1, 67) = 14.04,p < .001) and greater moral overlap between the two identities (F(1, 67) = 27.31,p < .001). By contrast, no substantial group differences existed for competence content recalled within the politicised identity (Fs (1, 67) < 2.49, ps > .08). Although some unexpected differences emerged for warmth (which was also recalled more often by politicised participants; Fs (1, 67) < 4.59, ps > .03), group differences were smaller and less consistent than those for moral content (for details see Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2017). Thus, moral content appeared to play a special role in defining politicised identities for activists, which is in line with the broader notion of normative fit that connects who we are with what we stand for.

Figure 7. Mean absolute amount of moral content recalled within the politicised identity for politicised and non-politicised participants. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the 95% confidence interval around the estimate.

Secondly, moral content overlapping personal and politicised identities predicted seeing the self as an activist (i.e., politicised identity). Specifically, we ran logistic regressions predicting self-labelling as a party activist (1) or not (0) on the basis of total identity content overlap between personal and politicised identities, moral overlap, warmth overlap and competence overlap at T1 and T2. First, replicating findings from the first subproject, overall count of total identity content overlap entered the model as a strong positive predictor of self-labelling as a party activist (T1: B = 0.36, SE = 0.17, Exp = 1.44, p < .05; T2: B = 0.31, SE = 0.16, Exp = 1.36, p < .08). Then, in the second step, the specific measure of moral content overlap entered the model as a strong positive predictor (T1: B = 2.02, SE = 0.97, Exp = 7.50, p < .05; T1: B = 1.62, SE = 0.90, Exp = 5.05, p < .08), rendering the total identity content overlap effect small and non-substantive (Bs < 0.12, ps > .58). Furthermore, measures of warmth and competence overlap were not substantively related to self-labelling as an activist (Bs < 1.11, SEs > 0.81, ps > .16). Importantly, these results were obtained with identity content predictors measured not only at T1, but also at T2.Footnote3 Thus, our moral overlap hypothesis (that moral content bridging the personal and politicised identities would predict seeing the self as an activist) was supported. In this way, moral traits not only seemed to define individuals’ politicised identity, but also had a unique function in predicting whether they saw themselves as a party activist (i.e., when personal and politicised identities match on moral, but not any other type of traits).

Unexpectedly, however, moral identity content did not predict engagement in self-reported action. We ran a multiple regression predicting frequency of engagement in collective action on behalf of Democrats using the same predictors as above (i.e., total content overlap, moral content overlap, warmth overlap and competence overlap). Results showed that although moral content overlap was, comparatively, the strongest positive predictor of self-reported action engagement (for morality: β = .12, t(62) = 1.25, p > .21; for warmth: β = -.13, t(62) = 1.22, p > .23; for competence: β = .05, t(62) = 0.60, p > .54), although its relation was relatively small and statistically non-significant. So, we did not find clear evidence that moral content was positively related to action engagement. We interpret this unexpected finding below.

Three lessons from the Politicisation Project

The second research project we reviewed emphasises the importance of understanding identity content against the backdrop of moral beliefs in the context of collective action. The findings showed that, for those with politicised identities, moral content defines and distinguishes politicised from unpoliticised identities in ways that non-moral content does not. This fits with the notion of normative fit and the idea that politicised identities may have a moral basis that defines who we are and what we stand for. As such, the first lesson of this project is that although stronger identification with the relevant group can, across the board, be expected to predict collective action, this ultimately relies on the meaning of that identity as ascribed by the individual (Van Zomeren et al., Citation2008).

The second lesson is that such identity content can be measured, as indicated by the new measure we developed. This measure is not difficult to administer and hence there seems to be little reason to restrict research on social identity and collective action to measures of (politicised) identification. Indeed, our work suggests that it is through changes in identity content that we can better understand the psychological process of politicisation (see Livingstone, Citation2014). Furthermore, the identity content measure avoids methodological disadvantages that limit analyses with group identification. For example, unlike identification measures, our identity content measure does not share method variance with other important collective action measures. Indeed, the common practise of predicting collective action (e.g., “I am willing to take action”) from identification with a politicised group (e.g., “I see myself as an activist”) has been criticised for being circular and descriptive rather than explanatory (Van Zomeren, Citation2013, Citation2015). As such, we believe that our identity content measure uniquely reflects the core of what a politicised identity means without suffering from the shared method bias present in other measures.

The third lesson from this project is that our new measure, which relies on individuals’ self-generated identity content, once again revealed a special relationship between politicised identity and moral beliefs. Specifically, we found that politicised identities, as compared to unpoliticised identities, are more likely to contain moral content, which suggests that the morality and identity variables may be more closely connected than previously thought. Indeed, by studying general, self- and group-definitional moral content (e.g., honest, sincere, trustworthy), our results confirm that politicised identities are, in a way, moralised identities.

However, we did not find a strong link between perceived group morality, as detected in identity content, and collective action. We interpret this in terms of politicised identity consisting of both a normative and action-oriented basis that motivates action engagement (Klandermans, Citation2014; Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001). We believe that our identity content measure tapped into the normative but not the action-oriented basis. Given the clear pattern of findings in the first project that linked violated moral beliefs with collective action, we think that two factors may best explain why this was not the case in the second project. First, the operationalisation of moral beliefs in terms of group morality may be a weaker reflection of the action-oriented basis of politicised identity than, for example, moral convictions, values, or rights. Indeed, the morality of one’s group may not be as clearly linked to action as the morality of one’s views. Second, it is possible that the perceived violation of moral beliefs is what is lacking in the group morality operationalisation of moral beliefs, and that some contrast with an outgroup is needed for such beliefs to become more strongly linked to action (Turner-Zwinkels, Citation2018). Future research is needed to test the validity of these explanations.

General discussion

Our proposal is that integrative social-psychological models of collective action like the SIMCA should include, both conceptually and empirically, a broader set of (violated) moral beliefs as well as the notion of (politicised) identity content. Both additions seem particularly important for a deeper understanding of politicised identity, which is typically one of the strongest predictors of collective action (e.g., Simon et al., Citation1998; Van Zomeren et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, we suggest that the notion of normative fit, from which our conceptual integration of the moral and identity motivations for collective action is derived, is very useful for a broader view on collective action, although such implications may not be immediately visible in the form of clear changes to models like the SIMCA. Indeed, the notion that who we are is greatly influenced by what we (will not) stand for suggests a need for social psychologists to have a much better understanding of such contextual meaning and fit. Below we discuss key implications of our proposal for extending the SIMCA, and for the broader social psychology of collective action more generally.

Integrating who we are with what we stand for in the extended SIMCA

Together, the Value-Identity Fit and Politicisation projects suggest that a broader range of (violated) moral beliefs (e.g., moral conviction, values, rights) and (politicised) identity content are fundamentally intertwined through the notion of normative fit: knowledge-based expectations that individuals have of, for instance, activist groups or social movements, which have a distinctive moral flavour (Oakes et al., Citation1994). Individuals take these expectations on board when they self-categorise as a member of that group and identify with that group. Indeed, across different contexts and countries (ranging from the Italian Water Movement to the Groningen Earthquake context and the US 2012 elections), we observed normative fit (and misfit) in terms of perceived violations of moral beliefs and (politicised) identity content, which moves us beyond the more restricted operationalisations of moral beliefs and social identity that have been used in the extended SIMCA (van Zomeren et al., Citation2012).

The key difference with the identity-based “logic of collective action” (cf. Olson, Citation1967) as expressed in the extended SIMCA is that moral beliefs and social identity seem, in the context of individuals’ motivation for collective action at least, more closely connected than previously considered. For example, in the studies we reviewed individuals seemed more likely to see themselves as part of a social movement or activist group if they shared the group’s moral beliefs (i.e., a value-identity fit), and especially if they perceived those beliefs to be violated. For example, this was the case in the Italian Water Movement context, where a new measure of perceived right violation (in terms of public access to water) predicted politicised identification across different samples (Mazzoni et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, in the context of the Groningen earthquakes (Kutlaca et al., Citation2017), in which no clear political movement was present, we found that perceived right violation (in terms of safety) predicted identification with the relevant group: For those living in the most affected areas, the perceived violation of “me and my” rights seemed to predict identification most strongly, whereas for those living in the least affected areas, the perceived violation of the rights of the broader group (those living in the general region) was most predictive. Across these contexts and studies, identification with the relevant group predicted individuals’ willingness to participate in collective action, as an important implication of such value-identity fit.

Furthermore, the notion of value-identity fit, and normative fit more broadly, seemed important in terms of communication processes that aim to motivate and mobilise individuals for collective action. In the Dutch student movement context (Kutlaca et al., Citation2016), we found that communicating value violation and a student identity affirmed but did not increase the motivation to act of those who already had relevant moral beliefs (i.e., “preaching to the choir”). Intriguingly, we also found that the communicating value violation and a superordinate group identity (i.e., national identity) did not only resonate well with those who already had relevant moral beliefs, but also with those who did not. As such, the findings suggest the importance of a normative fit between violated moral beliefs and social identity in the context of collective action, this time in term of communication intended to motivate and mobilise individuals.

In the 2012 US presidential election context (Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2015, Citation2017), we observed even clearer traces of normative fit in terms of how this may be expressed in identity content. Our findings showed that seeing oneself as a party activist implied, over time, a stronger overlap between self-generated personal and political identity content. Moreover, in terms of actual content we found that politicised identities were moralised identities because seeing the self as an activist was predicted by overlap in moral identity content (i.e., seeing both the self and the group as being honest, sincere and trustworthy). Although this particular operationalisation of moral beliefs (as perceptions of group morality) did not predict engagement in collective action (counter to what we found for other moral beliefs), it is possible that other operationalisations of moral beliefs (moral convictions, values, rights) could also be detected in the identity content of those who politicise or are politicised. Future research should focus on such content, which we would expect to converge with our findings with respect to moral convictions, values, and rights. Nevertheless, our findings are in line with a view of politicisation as a process in which the personal and the political become integrated in the self-concept, which entails a qualitative shift (Klandermans, Citation2014; Livingstone, Citation2014; Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001) that our newly developed measure can uniquely tap into.

Against this backdrop, how do these insights extend the SIMCA, both conceptually and empirically? Conceptually, the main change we propose is that the SIMCA should allow for a close connection between the moral and identity motivations for collective action. Empirically, the main changes we propose are that we should (1) broaden the operationalisations of moral beliefs, and similarly (2) include identity content as an important operationalisation of social identity.

We want to emphasise the importance of conceptualising and measuring the perceived violation of moral beliefs, as this seems to be the “active ingredient” in stimulating individuals’ motivation for collective action (see Skitka & Bauman, Citation2008). Indeed, the perceived violation of moral beliefs can increase identification with an already existing movement over and above one’s moral convictions (Mazzoni et al., Citation2015), but can also politicise groups in contexts where such organised movements do not yet exist (Kutlaca et al., Citation2017). Thus, a key reason why the perceived violation of moral beliefs may be such an “active ingredient” in the context of collective action is that it makes salient the relevant moral belief and the normatively fitting identity (Subašić et al., Citation2008), thus making clear who “we” are and what “we” (certainly will not) stand for.

Our line of thought further implies that moral convictions are just one way of operationalising moral beliefs. Although such issue-based convictions may arguably be one of the strongest instantiations of moral beliefs (e.g., Skitka, Citation2010; Van Zomeren, Citation2013), the value-protection processes that we assume should be similar for different operationalisations of moral beliefs, such as values that transcend specific issues and situations (e.g., Schwartz, Citation1992; Schwartz & Bardi, Citation2001), or rights that people feel entitled to across issues and situations (Kutlaca et al., Citation2017; Mazzoni et al., Citation2015). We therefore believe that our line of thought applies to a wider set of moral beliefs than moral conviction alone, and that it argues for a broader view on what “we” stand and will not stand for.