On July 29, 2022, the United States Supreme Court ruled on the Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta case in favor of the state of Oklahoma. In doing so, the Court formally limited criminal jurisdiction on Indigenous lands and thus further eroded Indigenous sovereignty and autonomy. The Court concluded that Indigenous courts do not have the authority to criminally charge non-Indigenous people, even if that person has committed a crime against an Indigenous person, on Indigenous lands. Instead, states possess concurrent jurisdiction with the federal government over crimes committed by all non-Indigenous people.Footnote1

This decision comes just shy of the two-year anniversary of the ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020) in which the Supreme Court concluded that nearly 43 percent of what is commonly known as the state of Oklahoma is in fact still Indigenous territory, and thus affirmed tribal jurisdiction over the eastern part of the state.Footnote2 In the McGirt case, mapping boundaries of Cherokee, Muscogee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole territories over time proved essential in the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold Indigenous sovereignty (). The McGirt decision represented a landmark victory for Indigenous struggles for sovereignty over their lands as it is one of the few moments in United States history where the US had been held legally responsible for adhering to and fulfilling its treaty obligations.Footnote3 The case of Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta directly challenged McGirt, with the state of Oklahoma arguing that Indigenous tribal courts should not have authority over non-Indigenous people, even if those people are occupying Indigenous lands.

While Castro-Huerta did not overturn McGirt completely, the case does symbolically represent a looming threat. And what’s more, in the weeks leading up to Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, the Supreme Court has shown that they are willing to reassess any and all previously established US legal precedent: the Court has limited the agency of all those residing in the US over their own bodies by overturning Roe v. Wade (1973) in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022)Footnote4 and has lifted previously established regulatory policies for environmental management in West Virginia v. EPA (2022).Footnote5 At their core, these legal decisions actively expand the jurisdiction of federal and state governments to erode sovereignty over bodies and land. And further, the Supreme Court’s shifting approach from largely upholding precedent to reconsidering it, directly mounts pressure against Indigenous sovereignty: Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta explicitly narrows the scope of Indigenous governance over their own lands and directly challenges their autonomy as sovereign nations. These recent Supreme Court rulings are forewarnings that without returning lands to Indigenous peoples, their sovereignty and freedom over themselves and their lands are always up for negotiation.

As the McGirt and Castro-Huerta cases reveal, returning land in purely symbolic terms is grossly insufficient; land-back frameworks must address the spatial, legal, and political realities to not only define the physical boundaries of returned ownership but must also provide systems to dynamically uphold and support what geographer Sara Safransky calls “alternative forms of sovereignty, political subjectivity, and personhood.”Footnote6 To this end, I borrow from Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s logic that moving toward a more just future requires that justice be embodied, spatialized, and “part of the process of making a place.”Footnote7 Making place thus demands redrawing the United States landscape as literal ground for Indigenous sovereignty by mapping boundaries of dispossession in order to propose new boundaries for the return of lands to Indigenous peoples. In this way, drawing is a foundational tool to visualize the United States’ liability in the spatial power dynamics enacted against Indigenous peoples and to offer strategies towards an anticolonial, antiracist future. And thus, visualizing the past and present conditions as means toward imagining new future engagement with land unsettles what Robert Nichols calls “recursive dispossession,” a process in which historic dispossessions generate property, which in turn reinforces and generates further dispossession. These processes have continually constructed enduring cycles of social, cultural, political, economic, and environmental injustices that are experienced in uneven ways and therefore must be overturned.Footnote8

As a non-Indigenous, first-generation American citizen, I am not immune from these cycles, and indeed, have largely benefitted from them. Further, my position as a faculty member in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at the University of California, Berkeley—whose longstanding and ongoing legacies of harm rest literally and figuratively on the Chochenyo Ohlone Nation’s ancestral and contemporary homelands—begets even more opportunity and security for me. Given these layers of privilege, my responsibilities to the histories of Indigenous land dispossession are trifold. First, I recognize and call out that violence was an intrinsic and intentional component in the creation of the United States as one of the world’s most powerful nation-states. Second, I actively work to expose how US legal policies and social attitudes have continued to work in tandem to make possible my role at the university. And third, I use the privileges afforded to me as both an uninvited guest on these lands and as a member of the University of California community to aid in the rematriation of lands to Indigenous peoples. I neither seek to position myself as speaking for or on behalf of Indigenous peoples nor propose that my engagement with these histories is enough alone to right the wrongs of the past. Instead, I explore the potentials of reconceiving the tools of architecture and landscape architecture—drawing and mapping—as methods for spatializing calls for land-based reparations in the hopes of demonstrating the very real ways that the design disciplines can contribute actionably to creating just futures that consider the intersections between history, place-making, and racial structures.

Despite cartography’s role in legitimizing and propagating colonization, in this essay I utilize the drawing and mapping of space as a counter-colonial method to envision the landscape as more than an object of exclusionary ownership.Footnote9 I will start by outlining how the United States has enacted violence strategically to take land from Indigenous peoples and formalized the relationship between land and property to allow its settlers to benefit socially and economically. Following this brief description of how definitions of land as property upheld ambitions for power, I will show how visualizing the specificities of place can support expanded engagements with land and thus support the rematriation of dispossessed lands in real, physical, and material ways for the benefits of Indigenous peoples in the United States. I argue that if land rematriation is to be more than symbolic, the specificities of historic, cultural, and geographic contexts must be centered. To that end, in the final section of the essay, I will present two different sets of rematriation strategies for the A:shiwi (also known as Zuni) and Tongva peoples to (a) demonstrate that histories of land dispossessions were not a uniform process but varied according to political, economic, and geographic conditions; and (b) show how those differences inform which types of new spatial logics are necessary and effective in rematriating lands back to Indigenous peoples, communities, and nations.

The Colonial Present, Violence as Strategy

In the United States, land is at the center of all scales of political and economic power, from the nation-state itself all the way down to the individual and is thus both a symbolic representation of power as well as the mechanism to wield it. Indeed, it is desire for more and more power that has incentivized the strategic and systematic expansion of the nation’s landholdings. These acquisitions of land, subsequent settlement by European descendants on them, expulsion of all other peoples from them, enslavement of people to work them, and extraction of natural resources from them have all been tactics in the accumulation and preservation of power. And it is these relations with land that have been the primary logic for organizing all social, political, and environmental configurations within the United States since its founding.

The process described above is known as settler colonialism and has been defined by Potawatomi philosopher and environmental justice scholar Kyle Whyte as a set of complex social processes in which at least one society seeks to move permanently onto the terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial places lived in by one or more other societies who already derive economic vitality, cultural flourishing, and political self-determination from the relationships they have established with the plants, animals, physical entities, and ecosystems of those places.Footnote10

Settler colonialism has also been described as ‘structural’ in that it is predicated on not just the access and governance over land but also on defining what can and cannot happen there, and by whom.Footnote11 Thus, settler colonialism structures nearly all aspects of settler life and seeks to eclipse and erase all other ways of living on and knowing the land. Political scientist Rita Dhamoon argues that settler colonialism must also be described as “a structure” that shapes the social, cultural, financial, political, and ecological environments in “temporal and ongoing, dynamic and continuous” ways, qualifying why settler colonialism is not an event from the past but a present condition.Footnote12

In the context of the United States, violence has been and continues to be foundational in sustaining this land-based power and is an enduring strategic agenda of the settler state—settler violence, enacted through both physical harm and psychological trauma, has worked in tandem to facilitate territorial expansion and resource extraction across the North American continent, past and present. And even as far back as the founding of the United States, land has been the core currency of its power. Te-Moak tribe, Western Shoshone American historian Ned Blackhawk has saliently asserted “violence and American nationhood, in short, progress hand in hand”: by linking nation-building and violent action against Indigenous people, Blackhawk posits that acts of harm against people and the environment were not anecdotal to but instead intrinsic and intentional to the very creation of the United States.Footnote13 I extend this idea further to propose that the making of the United States was indeed the same process as brutal acts of taking land from those societies that predated European invasion through physical, environmental, and social violence ().

Figure 2. Danika Cooper, [Taking] Indigenous Lands, [Making] United States, 2020. Many histories of the United States present its formation, or its “making,” as the successful and neutral accumulation of land and territory. Alternative readings of US history, however, reveal that it was in fact the result of violent and brutal acts of “taking” of Indigenous land and territory.

![Figure 2. Danika Cooper, [Taking] Indigenous Lands, [Making] United States, 2020. Many histories of the United States present its formation, or its “making,” as the successful and neutral accumulation of land and territory. Alternative readings of US history, however, reveal that it was in fact the result of violent and brutal acts of “taking” of Indigenous land and territory.](/cms/asset/9be75787-bb96-4fd6-86ee-92c66f863d71/rjae_a_2165805_f0002_c.jpg)

Violence against Indigenous peoples has endured as a “continually unfolding process”Footnote14 whose spatial forces have been repeatedly enacted across US spatial history through (broken) treaty agreements, federal and state land policies, economic agendas that depend on the enslaved labor populations, the development of settlements and reservations that encroach on sacred and significant sites, and discriminatory redlining practices and their present-day analogs in urban centers.Footnote15 These politico-legal documents and spatial configurations have been instrumental in formalizing, normalizing, and mapping what Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman calls the “violent fantasies of American masculinities, frontiers, and borders” onto the contemporary landscape.Footnote16 In this way, the United States continues to make and remake itself through a clear and vast assemblage of state-sanctioned violent land grabs, which are insidious and sometimes even invisible through neutralized narratives that position nation building as the result of progress, and all of which remain core forces in the continuation and ongoing legacy of the settler colonial project.Footnote17

As indicated above, the legacies of colonialism linger, haunting the present and threatening the future; they are a “seething presence” in the words of sociologist Avery Gordon.Footnote18 Within Gordon’s analytic of “haunting,” societies “become haunted by terrible deeds that are systematically occurring and are simultaneously denied by every public organ of governance and communication.”Footnote19 Building from and extending Gordon’s framework, Unangax̂ scholar Eve Tuck and C. Ree show haunting as not only a way that colonialism is enacted in the present but also how it is an antidote to its persistence. For Tuck and Ree, haunting is “the relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation.”Footnote20 In this way, confronting settler colonialism requires making visible what it seeks to normalize and by confronting and overturning how it continues to actively structure society’s present social, political, and spatial lives ().

Dispossession as Process, Erasure as Land Policy

The bond between settler colonialism and the built environment has been cemented by the commodification of land into property. The Euro-American conception of private property was an idea that was largely unpracticed in most Indigenous cultures in the United States prior to colonial contact. Under colonial rule, property regimes led to the continued enactment of brutal racial politics and violent displacements by creating power structures which depended on who had access to, ownership of, and resources for the development of land.Footnote21 The overlapping and concurrent processes of reconceiving land as property as power by allowing those who had access to property ownership to benefit economically and socially while others (Indigenous, Black, and Brown people) were altogether left out of such systems creates what Brenna Bhandar terms the “racial regime of property.”Footnote22 Drawing the boundaries of property has historically been, and remains today, a key component in discursively overwriting all other definitions of land and in exploiting the landscape as a material expression of power. In this way, mapping space has been complicit in the making of the colonial worldFootnote23—a world that Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Porou scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith calls “the imperial imagination,” and which empowered the United States at its conception to “imagine the possibility that new worlds, new wealth and new possessions existed that could be discovered and controlled.”Footnote24 By extension, contemporary maps and other drawings of the landscape that show property rights or support the management of property thus continue to be tools of the settler stateFootnote25 and are often “instruments of acute suffering” as stated by law historian Barbara Young Welke.Footnote26 This “acute suffering” is a direct consequence of the intersections between settler colonial ambitions for power, the social and political constructions of racial hierarchies, and mapping as a form of world-making through the myth that land is property.

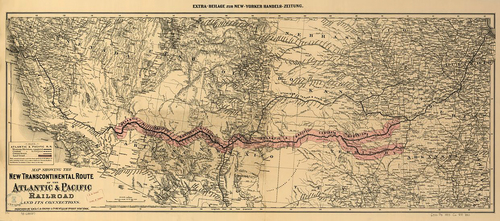

In the western parts of the United States, the “land as property” paradigm has manifested itself on the ground at multiple scales, not only shifting relationships between Indigenous peoples and their lands but also creating entirely new relations between settlers and their surrounding landscapes. During the first half of the nineteenth century, as the United States expanded its territorial control—in particular, through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853—new lands were brought under the jurisdiction of the US government. As the United States’ landholdings grew, and with the need to move across the vast new western territories, the construction of transcontinental railroads reformulated settlers’ perception of these lands not as inaccessible and valueless but as places of immense potential. As rail moved people, building materials, and consumer goods across the continent, the Western territories were reformulated as sites for development with mass migrations of settlers arriving ready to transform, cultivate, and harness the landscape for financial profit.Footnote27

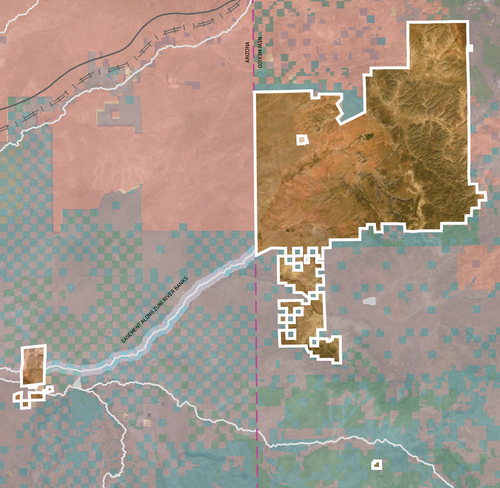

When Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act in 1862, it authorized the construction of a transcontinental railroad by granting millions of acres of Indigenously occupied land to railroad companies and states. These lands were surveyed and mapped by the US General Land Office, known today as the Bureau of Land Management.Footnote28 Between twenty- to fifty-mile-long strips of land on either side of the tracks were allocated as alternating parcels of property reserved for rail infrastructure and private ownership of settlers, creating the checkerboard pattern still seen today across the Western United States ( and ). The new rectilinear pattern emplaced onto the landscape signified, both conceptually and materially, an erasure of the patterns that had been previously established both by natural processes and by the Indigenous peoples who inhabited those landscapes. Huge tracts of Indigenous lands were taken by the federal government to rail companies and were used as collateral to obtain loans for construction costs, reinforcing how Indigenous land could be commodified for the benefit of non-Indigenous people.Footnote29 During this time, land grant maps became popular tools to advertise railroad lands for sale to settlers, giving railroad companies even more control over vast tracts of land in the western United States and further eroding the rights of Indigenous peoples to their lands.

Figure 4. G. W. & C. B. Colton & Co, Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company, and Chicago & Pacific Railroad, Map showing the new transcontinental route of the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad and its connections. New York, 1883. https://www.loc.gov/item/98688587/.

Figure 5. (Top) Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company, Map showing the location of the road and the land grant of the Atlantic and Pacific R.R. in Arizona … in New Mexico [N.P, 1883]. https://www.loc.gov/item/98688586/. (Bottom) Zoom-in of Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company, Map showing the location of the road and the land grant of the Atlantic and Pacific R.R. in Arizona … in New Mexico [N.P, 1883]. https://www.loc.gov/item/98688586/.

![Figure 5. (Top) Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company, Map showing the location of the road and the land grant of the Atlantic and Pacific R.R. in Arizona … in New Mexico [N.P, 1883]. https://www.loc.gov/item/98688586/. (Bottom) Zoom-in of Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company, Map showing the location of the road and the land grant of the Atlantic and Pacific R.R. in Arizona … in New Mexico [N.P, 1883]. https://www.loc.gov/item/98688586/.](/cms/asset/306dd4a0-041f-447c-8c13-ac6bdf3016bb/rjae_a_2165805_f0005_c.jpg)

The Pacific Railroad Act worked in direct coordination with the Indian Removal Act (1830) and with federal land laws like the Homestead Act (1862) and the Desert Land Act (1877) to legalize removing Indigenous peoples from lands that were deemed desirable, containing them on highly surveilled reservations, and consequently either giving away remaining lands to white settlers or retaining them for governmental use. These federal laws legislated social relations with land as well as created new kinds of legal structures for land ownership. Prior to 1871, approximately 45,000 miles of track had been laid, and by 1900 an addition 170,000 miles were added to the nation’s growing rail system.Footnote30 By the turn of the twentieth century, five different transcontinental railroads connected the eastern states with the Pacific Coast. These new major infrastructural systems created new and accessible avenues for settlement in the West by producing an expanded territory for settlement, resource extraction, and agriculture, all of which were encouraged by federal land policies that promised economic profit and social advancement for those who ventured West.

Federal land laws, like the Homestead and Desert Land Acts, paved a path for the federal government to not only take lands away from Indigenous people but to set up entirely new relations between the United States government and Indigenous nations. Fundamentally different from treaties that had previously structured US-Indigenous relations, these laws made no attempt to acquire consent from Indigenous nations. As a result, these land laws worked swiftly and violently to clear the western lands of Indigenous peoples for the economic and social benefit of the nation and its white settlers. Those Indigenous nations who were lucky enough to be “recognized” by the federal government and therefore qualified for reservation lands were often given lands that were not their own homelands (and therefore were unfamiliar landscapes that were disconnected not only from traditional means of sustenance but also from their sacred sites) and were almost always far smaller tracts of land than they had stewarded before colonization. Those who were not recognized federally were left landless and therefore without any access to land or cultural sovereignty.

In 1877, the General Allotment Act (also known as the Dawes Act) worked to speed up the dispossession of Indigenous land further and erode what remained of Indigenous autonomy on reservations. The legislation incentivized individual Indigenous people to give up portions of their communal reservation lands in exchange for a parcel for private use and ownership. This policy not only strategically and intentionally worked to destroy the strong connections to collective engagement with land inherent in many Indigenous cultures, but it also reinforced and emphasized the importance of private property in the United States. Many who agreed to give up their reservation lands found it difficult to live on small allotments and often were left destitute and eventually lost their lands.Footnote31 Within three years of the Dawes Act, nearly a quarter million acres of Indigenous land was sold to non-Indigenous peoples, and by 1920, 100,000 Indigenous people were landless.Footnote32 After allotment, some of the remaining portions of reservations were sold to white settlers while others were converted to national parks, forests, and grasslands, resulting in yet another instance of the dissolution of Indigenous stewardship over land.Footnote33 The overlapping of land and social policy shows that the conversion of land to property not only manifested physically in the landscape, but also shaped relationships between people and their environments. These policies ensured that settlers who came to the western parts of the United States were supported with cheap land and infrastructure to build new and successful lives, while ensuring that Indigenous people were denied such opportunities. Today, the legacies of these brutal and intentional policies that worked to systematically erode Indigenous sovereignty and access to land remain present. Recent research argues that the dispossession of land and forced migrations of Indigenous peoples by European and American settlers has resulted in the loss of “nearly 99% of the land they historically occupied” and further, that the contemporary consequences of dispossession and dislocation from historic homelands are that Indigenous peoples are suffering from increased risks associated with climate change hazards, poverty, and diminished economic opportunities.Footnote34

Survival as Process, Drawing as Survival

Despite their frequent conflation in the United States, ‘land’ and ‘property’ are not the same. Outside of Western contexts, land exists beyond property to represent the spiritual, life-giving, and cosmological parts of many Indigenous cultures and societies: the word ‘land’ itself can be used to mean landscape, place, territory, or home.Footnote35 As such, land is not only the basis of economic and financial freedom but also carries spiritual and cultural import since land is “the living entity that enables Indigenous life.”Footnote36 Thus, access to and sovereignty over land is an essential component of all Indigenous place-making—and though each tribe, nation, and community has its own relationship to land and landscape, “the most important distinguishing feature of Indigenous peoples is their shared respect for the land—Mother Earth.”Footnote37 Goeman argues that ‘land beyond property’ requires seeing land as “a meaning-making process rather a claimed object,” and through this lens one can imagine land as a “repository for people’s experiences, aspirations, identities, memories, and visions for alternative futures.”Footnote38 ‘Land beyond property,’ in Goeman’s conception, is also a “storied site of struggle and resistance.”Footnote39 Indeed, it is already the ground of “livingness” in Black feminist scholar Katherine McKittrick’s conception because it “slows and interrupts White settlement.”Footnote40 Indigenous peoples, despite how much trauma has been inflicted on them and their lands, and despite how hard colonial forces have tried to entirely genocide them, have survived, and have repeatedly resisted the ‘land as property’ paradigm by maintaining their connections to land, even when their engagements with it have been severely and brutally restricted, as demonstrated in the previous sections of this essay.Footnote41

It is in this conception of land as storied and as the site of resistance, that I am interested in thinking through how alternative conceptions of land can be a literal ground for future anticolonial and just engagements with land. As Tuck has repeatedly reminded us, “decolonization is not a metaphor.”Footnote42 Instead, decolonization is an active and intentional project, one that, in Blackhawk’s words, “requires reevaluation of many enduring historical assumptions.”Footnote43

Given how significant maps have been in the creation of a ‘land as property’ paradigm, and how powerfully they have been wielded as a mode for territorial conquest, an antiracist, anticolonial reevaluation of “enduring historical assumptions” requires rethinking and remapping lands under new conceptual and ideological frameworks: Yellowknives Dene scholar Glen Coulthard has argued that decolonization thus is not only about land in a material sense but also “deeply informed by what the land as a system of reciprocal relations and obligations can teach us about living our lives in relation to one another and the natural world in non-dominating and nonexploitative terms.”Footnote44 Calls for social and environmental justice thus must concentrate their efforts on the transfer of land holdings back to Indigenous peoples; the boundaries of such transfers can be visualized through normative and novel cartographic techniques.Footnote45

Upon first glance, it may appear counterintuitive to suggest that rematriation efforts include cartography as a primary decolonial method given that I have elaborated above how the map has reified historical and contemporary US society and has been actively instrumentalized to enact Indigenous genocide and land dispossession. The tension that exists when employing a normative method of activism to imagine a radical outcome is exposed by Black feminist theorist Audre Lorde when she stresses, “[t]he master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”Footnote46 Dakota historian Waziyatawin, in writing about the specifics of land, asserts that more than anything, decolonization requires a fundamentally different engagement with land beyond and outside of the structures of colonialism rather than from within it.Footnote47 And while I absolutely agree with Lorde and Waziyatawin in most decolonial, antiracist scenarios, I argue that the rematriation of lands to Indigenous peoples will necessarily intersect with political, geographic, and economic systems already in place, normalized, and universally accepted.Footnote48 Because of the established norms that a rematriation strategy must challenge, and because of the inherent complexity required to “reevaluate historical assumptions,” I follow Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s assertion that one can “use the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house”Footnote49 and assert that mapping lands must be part of the suite of tools employed towards a reparative future.

Cartography can be used to advance calls for rematriation in two ways. First, I argue that normative mapping is an effective device in unequivocally demonstrating how lands have been stolen from Indigenous peoples for the benefit of settlers. Within legal and political contexts, the transfers of land must be justified by historical evidence and these kinds of cartographic representations prove essential demonstrations of those histories.Footnote50 As a result, I have made a series of maps that use conventional cartographic techniques to contextualize historical and contemporary contexts of both the A:shiwi and Tongva territories. These kinds of maps help to validate that the dispossession of millions of acres of land from Indigenous peoples was not accidental or unintentional but rather was deliberate and calculated. I also present a second type of mapping that acknowledges non-Western and noncolonial engagements with land in order to shift the focus of land relations away from ownership and commodification and to highlight alternative and layered engagements with land. Alternative methods of mapping land and landscape—in other words, those that do not adhere to traditional mapping conventions—are employed as means to reveal the myriad ways that land exists beyond the ‘land as property’ paradigm. These drawings overlay multiple viewpoints, perspectives, geographic scales, and time periods to create more complex readings of land.

Together, these two approaches to mapping work in tandem to advance an expansive approach to drawing that can be used as a tool for reparative justice. I advocate for a reparative strategy that returns agency over land to Indigenous peoples so that they may themselves determine how land is imagined, managed, and regulated. As Goeman has said,

“Autonomy over the land, however, is not just a matter of reestablishing another nation-state with autonomy over resources and economic development or writing a ‘true’ version of the reservation; rather, the struggle for autonomy is about self-determining how communities are made and function in the present and into the future.”Footnote51

Autonomy over land requires not only the legal return of physical land but also the political sovereignty to decide what should happen with those lands in order to unambiguously protect Indigenous peoples against those who claim that rematriation is outside the political and legal frameworks of the United States and thereby challenge the legality of returning land. In these ways, mapping can actively reverse historical injustices by advocating legal transfers of land and thus establishes a reassertion of Indigenous agency over their lands and their spiritual, cultural, and economic modes of living.

Through the distribution of land back to Indigenous peoples, I advocate for a radical remaking of land relations not based on control over territory but based on Mohawk activist and lawyer Patricia Monture-Angus’s request for the “right to be responsible” for land.Footnote52 Prioritizing land as a place that requires active responsibility, in turn, transforms the way that all people live in relationship to the environment and landscapes they inhabit. Responsibility extends the definition of land far from mere property rights and land tenure to include spiritual and cultural engagements with land. The United Nations Commission on Human Rights in their landmark Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) formalized this definition of spiritual and cultural responsibility by asserting:

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources, and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard.Footnote53

Through this statement the United Nations acknowledges and recognizes other ways of inhabiting landscape, where the spiritual relationships and cultural rights to lands are respected. But in order to ensure that this respect is maintained, and that access to their lands are an incontrovertible right, Indigenous peoples must have complete control over their sacred, significant, and historic sites.

In this context, maps are made to resist the persistence of colonialism by drawing sovereignty as a place-based endeavor. I return to Gordon’s proposition that haunting is not only a confrontation of persistent injustices from the past but is also a confrontation that “requires (or produces) a fundamental change in the way we know and make knowledge.”Footnote54 In the case of rematriation of Indigenous lands, I argue that fundamental changes in our knowledge systems must extend to creating new relations with land that address the long legacies of dispossession. Mapping is a mechanism to redraw land with profoundly different values, positions, and meanings in society. Goeman’s concept of ‘(re)mapping’ thus becomes useful as an analytic framework for “understanding the processes that have defined our current spatialities to sustain vibrant Native futures.”Footnote55 In other words, mapping lands intentionally for their rematriation acknowledges that land is not a universally accepted term, and that including land as the basis of the spatial power dynamics which shape social, political, and cultural relationships can be, in Goeman’s words, a path toward “the ‘imaginative’ creation of new possibilities.”Footnote56

(Re)Mapping Land as Visions for Reparative Futures

This research engages with two distinct Indigenous communities—A:shiwi and Tongva—both of whom steward parts of the United States arid lands but whose relationships to land are different in the ways that each define land for themselves and the ways that the federal government has imposed land relations on them. As geographer Bobby M. Wilson has articulated, understanding race in the United States depends on situating it within both a specific historical context and a geographic one; he writes, “a critical geography of race-connected practices requires sensitivity to the way in which regional regimes of accumulation transform racial practices.”Footnote57 Thinking through questions of reparative justice, especially justice that includes land-based reparations, therefore necessitates not only larger narratives and analytic frameworks that theorize and counter historical assumptions of the ‘land as property’ paradigm but also those that are geographically, politically, and culturally specific. In rematriating lands to Indigenous communities and nations in the United States, this means examining each individual community’s unique relationship to historical events and narratives as well as the particularities of their past and present relations with land and landscape. Thinking through the complexities of land-based reparations thus builds from the definition of Indigeneity as “belonging to a place” rather than “belonging in a place”:Footnote58 this distinction helps to situate questions of reparations within temporally contingent contexts, in that it acknowledges that relationships to land are in constant flux, with many Indigenous peoples no longer geographically connected to the lands that were once a part of their everyday lives.Footnote59

For some it may appear that rematriation is too radical an act or perhaps even impossible. However, systems of private property are relatively new conceptions introduced into North America by European colonists in the sixteenth century. Prior to colonization, other forms of land occupation and management had been in practice for centuries. Moreover, borders that shape nations and delineate ownership are inherently malleable abstractions made discernable only through legal and political infrastructure, and as such can and do change relatively quickly when there is political will. And, perhaps most importantly, the return of Indigenous lands is already happening in numerous parts of the United States, proving that rematriation is indeed possible and must continue to guide future relations with land in the United States.Footnote60

In the following sections, I argue that to continue building momentum for the deliberate and effective return of land to Indigenous peoples, the specificities of place and culture must be addressed. I suggest that the legal, social, and geographic strategies necessary to give land back must be hyper-specific to each Indigenous nation and each geographical region because while there are certainly shared experiences among Indigenous communities, the particularities of how spatial and racial policies have manifested on the ground have not been consistent nor even. I show how in order to meet the goals of land-based reparations for all Indigenous peoples, strategies must be distinctive for each specific community and nation. Mapping can be an operative tool in that process and I show how strategies that give land back to two Indigenous communities, the A:shiwi and Tongva peoples, will necessarily differ in light of their different sociopolitical, cultural, and geographic contexts.

The Zuni nation is federally recognized and was given approximately 700 square miles of reservation lands in 1877. Their reservation lands are noncontiguous and occupy parts of western New Mexico and eastern Arizona, though their ancestral and contemporary homelands extend much beyond the boundaries of their reservation. Large tracts of lands surrounding their reservation are managed by the United States Forestry Service and Bureau of Land Management as well as private. Strategies for giving land back to the A:shiwi people thus require confronting the role that the federal government and private entities play in acquiring large tracts of land for the purpose of supporting conservation and the agricultural industry. The Tongva nation, on the other hand, is not recognized by the federal government and therefore has never been allotted any reservation lands. Their homelands are primarily occupied by private ownership and are obscured by suburban sprawl, strip malls, and institutional buildings in what is today known as the Los Angeles metropolitan region. Strategies for giving land to the Tongva nation thus require thinking about the specific legal and spatial parameters of zoning, real estate speculation, and private development in an urban context.

For each nation, I start by briefly describing the histories of land dispossession and how those events have shaped their contemporary relationships with land. I then show how moving toward rematriation can be aided by mapping both the lands lost and proposed lands for return. I suggest strategies knowing that any material transfer of land back to Indigenous peoples requires deep involvement with members of each of these two Indigenous communities as well as political will and capital at all levels of government. I identify my role in the move toward rematriation as a visual communicator and academic scholar to propose methods by which mapping and drawing might be employed for the purpose of giving land back and so that the burden of advocating for new relations with land does not solely rest on Indigenous peoples to repeatedly bring attention to the enduring injustices enacted against them.

Grabbing Land, Changing Boundaries: Zuni Territory

The territory that A:shiwi people (also known as Zuni) have occupied, tended, and lived with from time immemorial has been under threat since the first Europeans ‘discovered’ the territory in the sixteenth century. Throughout A:shiwi encounters with colonizing forces (Spanish, Mexican, and subsequently American), there have been moments of successful resistance to their cultural and territorial takeover, but there have also been many moments of violence and dispossession. Precolonial A:shiwi communities were involved in hunting, fishing, basket weaving, agriculture, etc.Footnote61 The lands they stewarded and traversed were vast, spanning multiple kinds of ecological and environmental conditions—high desert, rocky outcrops, pine forests, and grasslands. As Jim Enote, an A:shiwi farmer and former head of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center in New Mexico, has noted, the A:shiwi have been carving their stories and experiences into the rocks of their landscape for thousands of years with “names and images connected with places conveying a symbiotic relationship between the people and the land”.Footnote62

Zuni lands were once fabled to be the “Seven Cities of Cibola,” a landscape of unbridled wealth, and as a result attracted Spanish colonizers to travel north from Mexico in the mid-sixteenth century in the hopes of conquering the territory for Spain and discovering endless riches of gold.Footnote63 In 1680, the A:shiwi aligned with other Indigenous communities in the region to carry out a revolt where they successfully resisted the Spanish by taking refuge atop the sacred mesa of Dowa Yalanne.Footnote64 But over the following century, Spanish colonizers ruthlessly attempted to conquer the A:shiwi peoples and their lands.

Up until the nineteenth century, the A:shiwi were relatively successful in resisting encroachment on their lands not only from Spanish and Mexican settlers but also from other Indigenous communities like the Apache, Navajo, Hopi, and Acoma. When the United States signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, it acquired approximately 525,000 square miles from the Republic of Mexico, lands that included Zuni territory.Footnote65 As US settlers moved through and developed a growing US territory, the A:shiwi people cooperated with the United States Military to fend off threats from Apache and Navajo nations. But by the end of the nineteenth century, the United States government abandoned its alliance with A:shiwi, and federal officials in the newly established territories of Arizona and New Mexico largely ignored A:shiwi rights to land and water.Footnote66 During this time, federal land laws like the Homestead Act (1862) and the Desert Land Act (1877) made A:shiwi homelands susceptible to vicious land grabs by Mormon pioneers who settled the Little Colorado River basin and its tributaries, large cattle companies who financed the expansion of grazing onto the western territories, and the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company which constructed rail infrastructure through Zuni territory.

With mounting pressures to settle, farm, and mine on Zuni lands, US President Rutherford B. Hayes delineated lands for a Zuni reservation under an executive order in 1877. He wrote:

It is hereby ordered that the following-described tract of country in the Territory of New Mexico, beginning at the one hundred and thirty-sixth milestone on the western boundary line of the Territory of New Mexico, and running thence north 61°45’, 31 miles and eight-tenths of a mile to the crest of the mountain a short-distance above Nutria Springs… hereby is, withdrawn from sale and set apart as a reservation for the use and occupancy of the Zuni Pueblo Indians.Footnote67

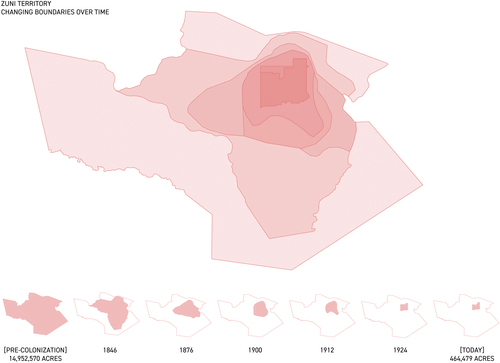

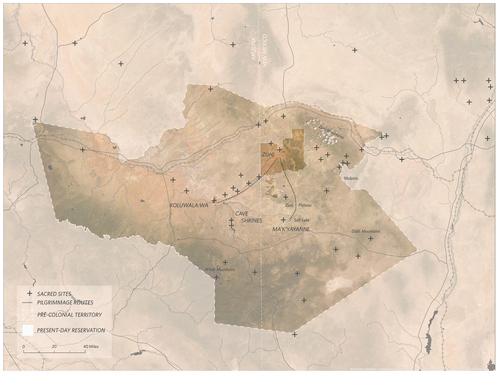

The Zuni Reservation, however, has never been a fixed boundary—instead, it has expanded and contracted several times since its creation. Two years after President Hayes’ executive order for the Zuni Reservation, Frank Hamilton Cushing, an ethnologist who had previously travelled with the John Wesley Powell Geographic Expedition exploring the western territories, surveyed the lands set aside for A:shiwi and determined that the delineated reservation was too small and successfully convinced President Hayes to enlarge the reservation.Footnote68 Six years later, as pressure mounted from army officers stationed in the nearby Fort Wingate to acquire the title to Nutria Spring and Village, a sacred site for the A:shiwi peoples, the reservation was once again enlarged to include it. Despite the expansion of reservation lands, as more and more settlers moved into the region during the first part of the twentieth century, Zuni grazing lands were reduced and in 1909, thousands of acres were taken from the Zuni Reservation and given to the United States National Forest Service. Three years later, in 1912, the order was reversed, and lands were given back to the reservation by President William Taft. In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson added yet another 80,000 acres to the reservation. Seventeen years later in 1934, the entire reservation was fenced, and the Zuni herds were restricted to grazing exclusively on the reservation lands, causing extreme erosion of the soils on the reservation. A:shiwi unsuccessfully resisted the change, appealing to the federal government for permission to use traditional grazing areas that existed beyond the fenced zone; the consequence was the forced reduction in livestock due to a smaller overall grazing area and resulted in increased poverty for many A:shiwi families who relied on livestock as their main income. In 1935, the reservation was increased with an additional irregular piece of the Cibola National Forest that had been unintentionally left out of the 1917 expansion under President Wilson. In 1949, an additional sixty thousand acres, called the Zuni North and South Purchase Areas, were added to the Zuni Reservation, and over the following three decades, other small additions were added to the reservation, including the Zuni Salt Lake in 1978. Mapping the Zuni Reservation over time thus demonstrates unequivocally that geopolitical borders can, and continue to be, amended and adjusted ().

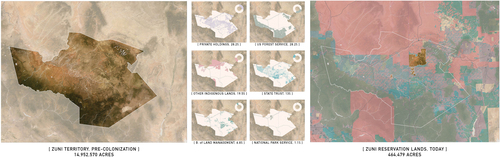

Today, the nearly fifteen million acres within the homeland territory of A:shiwi people have largely been carved up and distributed for the benefit of non-A:shiwi people (). Despite its expansions and contractions over time, the contemporary Zuni Reservation still only accounts for approximately three percent of the territory that A:shiwi people stewarded prior to colonization (). The largest proportion of A:shiwi’s historic territorial lands are currently privately owned (approximately 28.2 percent) or are managed by the United States Forest Service (approximately 28.2 percent). The United States Forest Service was founded in 1905 and its mission is to “sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.”Footnote69 In addition to the U.S. Forest Service, parts of the Zuni territory are currently managed by other federal conservation agencies, like the Bureau of Land Management (6.8 percent) and National Park Service (1.1 percent). Environmental sociologist Dorceta E. Taylor has argued that the genocide of Indigenous peoples and dispossession of their lands has been part of the development of the conservation movement from its very inception.Footnote70 In light of Taylor’s historical analysis, an agenda for land rematriation must not be thwarted by a romanticization of the conservation movement. Instead, anticolonial futures should not only involve learning from the robust, longstanding, and diverse environmental protection strategies that Indigenous peoples have been practicing since time immemorial but should also put Indigenous peoples at the forefront of defining how lands are managed, stewarded, and protected.Footnote71

Figure 7. Danika Cooper and Jaclyn Tobia, Mapping Land Ownership in Zuni Territory, Then and Now, 2022.

Table 1: Land Ownership in Zuni Territory

Strategies for Reestablishing A:shiwi Sovereignty

Returning lands to the A:shiwi people will necessarily require multiple strategies that are political and spatial, and will likely occur at multiple geographic and temporal scales. Currently, the Zuni Reservation is discontinuous, with lands in both Arizona and New Mexico. This geographical disconnection means that the A:shiwi must travel on nonreservation lands to move between their territories. A first strategy for rematriation might be to reconnect these territories by expanding reservation lands to create one contiguous territory. The Zuni River, a tributary of the Little Colorado River and a sacred waterbody to the A:shiwi people, is not only a geographical link between the two territories but is also the site of a A:shiwi pilgrimage made every four years.Footnote72 With both its geographically strategic position as well as its cultural and religious significance, the river is an obvious connector and might enable safe, continuous passage between the Arizonan and New Mexican reservation sites by building easements along its banks (). Easements through federal and state lands might also be a way to begin building access for the A:shiwi to visit other sites that are either sacred or culturally significant but which are beyond the boundaries of the reservation (). Creating easements is a strategy regularly employed by federal and state governments to address desires for conservation, to acquire lands for mineral extraction, and to create public access to natural features, and thus is a spatial strategy that can be employed with relative legal ease for the purpose of returning lands to A:shiwi people.

Figure 9. Danika Cooper, A:shiwi Sacred Sites (2022) after Ronald Stauber and Troy Lucio, Map 18: “Traditional Zuni Religious Use Areas,” in Ferguson and Hart, A Zuni Atlas (1990).

Longer-term efforts might require more radical reimaginings of the territory as historic Zuni lands overlap with contemporary private ownership and inevitably necessitate more fundamental discussions about the role that property should play in a global collective future. Further complicating questions about ownership of land is that nearly 20 percent of the lands within the historic Zuni territory are now other reservation lands and thus require a more nuanced approach to thinking through the return of which lands and to whom. In our current ‘land as property’ paradigm, the legal and economic foundation of property does not account nor allow for collective stewardship, but the overlapping and concurrent occupation of territories by different Indigenous groups suggests that perhaps the future of land occupation and management requires a wholly new approach wherein exclusive ownership of land is made obsolete.

Property as City Making, City Making as Erasure: Tongva Territory

The Tongva people, the original inhabitants of the lands that today make up the Los Angeles metropolitan region, have continued to suffer the violent denial of their sovereignty and loss of their land throughout centuries of direct and indirect encounters with colonial forces. But despite the numerous attempts over time and space to eliminate them, the Tongva people have not only survived but are engaged, active, and present participants in the ongoing creation of Los Angeles. An anticolonial future for Los Angeles thus requires explicitly illuminating the ways that Indigenous peoples have continued to shape the city in addition to devising and implementing rematriation strategies, both of which are critical steps in decolonizing city-making generally, and in Los Angeles specifically.

Current readings of Los Angeles’s urban conditions are dominated by seemingly infinite sprawl of low-density development, congested highways, and the empty, concrete Los Angeles ‘River.’ While these features are iconic of Los Angeles’s urbanity, they are also artifacts of the colonial processes that form the city; urban growth and economic development are responsible for the literal paving-over of the longer histories of human and non-human occupation in the region. In the context of Los Angeles, property as the singular definition of land structures almost all of the decisions about how the city is built, working to uphold a system where land is commodified for the purpose of economic growth and political power.Footnote73 In Los Angeles, property entitlements are emblematic of how larger global entanglements of land, capital, and racialized politics are continuously cemented in place.

Under colonial agendas, successfully acquiring lands that could be converted into private property and subsequently used to economically sustain the city of Los Angeles required the permanent removal, subjugation, and even enslavement of Indigenous populations.Footnote74 Spanish colonists who represented not only the Spanish monarchy but also the Catholic Church colonized the western parts of North America as early as the seventeenth century and eventually established a network of missions throughout the state of California. Between 1769 and 1823, twenty-one missions were established in California, and as a result the Catholic Church became one of the largest nongovernmental landholders in the state. The mission system was responsible for enacting horrific trauma upon many of the Indigenous communities that included dispossession of their lands, forced assimilation practices to convert them to Catholicism, and enslavement at the mission sites to cultivate agricultural production and graze cattle, whose profits were returned to the Catholic Church.Footnote75 While some Indigenous nations and tribes were eventually ‘compensated’ for the dispossession of their ancestral homes through federally sanctioned and regulated reservation lands (like the A:shiwi as established in a previous section), others were offered nothing. The Tongva were among those not included in the United States reservation system, and today there is not a single piece of land in the Los Angeles metropolitan area that belongs to any Indigenous nation despite extensive documentation of their presence long before European settlers arrived.Footnote76 And while the origins and subsequent long-term consequences of the federal reservation system are undeniably problematic, it is nonetheless one of the few mechanisms by which Indigenous nations have been able to assert their identity and sovereignty outside of the bounds of the United States’ social and economic systems. As a result, the fact that the Tongva have no control over any landbase poses a direct and continual threat to their economic, cultural, spiritual, and spatial sovereignty.

Los Angeles historian Mike Davis asserts, “It was an immensely convenient and profitable fiction to say that the first people of Los Angeles no longer existed. We are talking about a conspiracy through the twentieth century to avoid any question of reparation.”Footnote77 Normative histories of Los Angeles reinforce the myth that the Tongva people are extinct, but incorporating Tongva people into Los Angeles’s urban histories exposes that the Tongva people are, of course, very much a present contemporary society, building upon rich traditions and contributing to all aspects of Los Angeles life in meaningful ways. And through their continued resistance to erasure, they have influenced each successive era of human history in the Los Angeles metropolitan region. Tongva-Acjachemen artist L. Frank Manriquez described this fight for survival in the following way: “To have survived and to still call yourself [I]ndigenous to a place, belonging to a place, and this is that place…that’s pretty strong. That takes something very special.”Footnote78

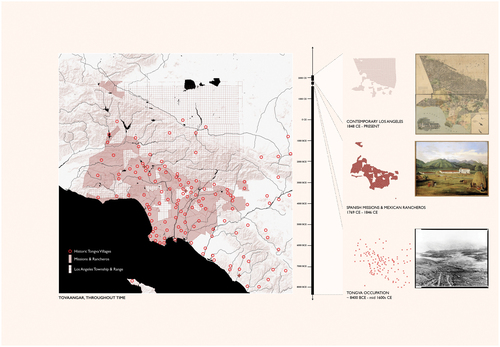

Narrating a more critical history of Los Angeles, one that challenges the colonial foundations that have produced contemporary urbanization, is a first step in revealing and acknowledging the repressed, erased, and dispossessed memories of the Tongva people. A more critical recounting of Los Angeles’s entanglements with colonial processes is also a reminder that the way in which the city has developed is not an inevitability but rather the result of deliberate design and policy choices. Challenging extinction narratives and featuring Indigenous voices in the building of cities like Los Angeles ensures that the Tongva legacies are mapped, preserved, revealed, and respected in the physical landscape of Los Angeles. Mapping significant sites throughout Los Angeles County over time—and with an active acknowledgment of Tongva history and memory—moves a future of Los Angeles toward one that rejects the deeply-embedded colonial systems that have led to continual repression of Tongva presence in the landscape ().

In Los Angeles today there are physical markers referencing Tongva people and histories in both explicit and implicit ways. In the neighborhood of Boyle Heights, in the eastern part of the city, there is a large mural that pays tribute to the life of Toypurina, a Tongva woman who led a revolt in 1785 against Spanish colonial rule and the Catholic Church’s brutal treatment of Indigenous people ().Footnote79 Today, Toypurina remains a recognizable symbol of resistance and an “icon of California Indian women’s resistance to colonial oppression,”Footnote80 as is evidenced by the multiple tributes to her throughout the city. These memorials all bring much needed attention to her life and courage, as well as broader histories of Indigenous resistance.Footnote81 However, these murals do little to address the larger, more structural impacts of colonialism that have had devastating and long-term consequences for the Tongva community, such as lack of economic, spatial, and political sovereignty. Further, these murals, which function as memorials, give rise to fundamental questions about what it means to showcase historical and contemporary presence of Tongva peoples within Los Angeles without federal recognition, and what it means for memorials to be placed in contested territories that have been developed for the economic and political benefit of non-Tongva people.

Figure 12. Raul González, Ricardo Estrada, and Joséph “Nuke” Montalvo, Conoce Tus Raices, Toypurina Mural, 60 ft. x 20 ft., Ramona Gardens, East Los Angeles, California, 2009. Photograph by Jaclyn Tobia, January 2023.

A decolonized urban Los Angeles thus requires moving beyond memorials to include not only federal recognition (the state of California did officially recognize Tongva in 1994)Footnote82 but also the rematriation of lands to the Tongva. In advocating for the federal recognition of Tongva, I do not mean to imply that Indigenous peoples cannot flourish culturally without it but instead to draw attention to how the denial of federal recognition works as a legal loophole to deny Tongva any land-based reparations as the U.S. will not return lands to a community not recognized as sovereign. To that end, recognition must be established alongside the transfer of federally and state-held lands to Tongva peoples.

Strategies for Drawing Tongva Back into Los Angeles

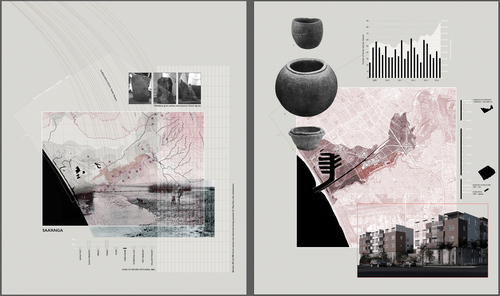

Given the density of urban development and the privatization of land in Los Angeles, returning lands to Tongva peoples will require multiple types of strategies. Tongva-Acjachemen scholar Charles Sepulveda has argued that providing opportunities for reestablishing relationships to land is a priority for Tongva. He writes, “Even if this connection is severed, the power of the land itself remains and the living relationships can be renewed.”Footnote83 In a highly developed context like Los Angeles where much of the landscape is already built upon, rematriation will likely require a piecemeal approach wherein smaller plots of land (likely at the scale of an urban parcel) are accumulated and given back to Tongva peoples over time, rather than a more comprehensive strategy for giving large swathes of land back. One attempt might involve giving over lands that are currently zoned as preserves. These lands are already protected from development pressures and thus their futures can be wholly determined by the Tongva people to address their needs and desires. A second approach should involve all sacred and culturally significant sites. Despite the fact that these places are scattered throughout the Los Angeles region, they must be returned to the Tongva, regardless of who currently owns or occupies them. The Kuruvungna Village Spring, for example, is currently part of University High School campus in Santa Monica, an affluent city within the Los Angeles metropolitan region. In 1994, Tongva activist Angie Behrns successfully fought to prevent the spring from being destroyed as part of the school’s plan for an underground parking lot. In response, she established the Gabrielino Tongva Spring Foundation, which for nearly thirty years has been “dedicated to preserving the heritage site and educating the public about the history as well as preserving the natural and cultural resources of the area.”Footnote84 And while the foundation has been successful in curbing further development of the site, the foundation’s agency over the land is relatively precarious as the school has legal tenancy over the land. Thus, the transfer of these lands back to Tongva, along with all other historically significant and sacred sites, is imperative in ensuring that Tongva people have complete sovereignty over how they renew their relationship with their lands. Yet another approach to rematriation is to create an inventory of underutilized, government-owned, and/or foreclosed lands that can be easily transferred to the Tongva community, who can decide whether to keep those lands, sell them, rent them, or develop them. For instance, if a parking lot is transferred that has very little value to the Tongva, it may be sold or rented as income to benefit the community, or redeveloped to meet a need or desire of the Tongva community. Regardless of which strategy is employed (and there are likely many others not explicated here), the underlying theme for all approaches to rematriation in the context of Los Angeles must be to first ensure that the Tongva peoples’ status is that of a sovereign nation and second, to secure agency and control over lands within the Los Angeles metropolitan region. Building from the Tongva theory of Kuuyam, efforts to unsettle the dichotomy between Indigenous and settler must instead understand non-Indigenous peoples as “potential guests of the tribal people, and more importantly—of the land itself,” and consequently reorient our understanding of land from commodity toward land as “sacred and as having life beyond human interests.”Footnote85

Drawing Land Beyond Property, Spatializing Reparations

A case for reparations, especially land-based reparations, requires imagination. I use the term ‘imagination’ not to imply a symbolic or purely conceptual engagement with reparations but instead to posit that land-based reparations require reenvisioning a wholly new United States by confronting assumptions that have become normalized or universally accepted as true and unalterable. In this way, then, the US can be a place not governed by the commodification of land as a resource for economic growth but as a place that sees ‘land as more than property.’ Reformulating relations with land activates fundamentally new political, economic, and cultural frameworks for engaging with not only land to include collective stewardship and resilient environmental practices but also provides a first step to addressing enduring injustices that the ‘land as property’ paradigm has inflicted on Indigenous peoples.Footnote86

To imagine a new future for the United States necessitates an expanded canon of stories, histories, and memories that include those of dispossession and genocide, intentional practices of racial injustice and enslavement, and successful acts of resistance to such systems.Footnote87 Bringing these stories into the fold of the cultural imaginary not only permits but demands actionable steps to repair the harm inflicted on Indigenous communities that these histories have produced. Accordingly, all non-Indigenous residents living on and benefitting from land dispossessed from Indigenous nations are responsible for incorporating and adopting Indigenous stories and memories into the plans and designs of our futures. Archaeologist Jan Assmann writes:

Not the past as such, as it is investigated and reconstructed by archaeologists and historians, counts for the cultural memory, but only the past as it is remembered… Cultural memory reaches back into the past only so far as the past can be reclaimed as ‘ours.’ This is why we refer to this form of historical consciousness as “memory” and not just as knowledge about the past.Footnote88

Assmann’s assessment of memory here is especially important in envisioning an anticolonial, antiracist future in the United States largely because when stories of injustice are erased or are left out of the collective memory, they are not acknowledged and therefore cannot be repaired. Reimagining the collective memory as anticolonial must necessarily address Indigenous land dispossession and must make meaningful advances toward returning lands. Mapping the landscape as grounds for a new collective memory can be a way of not only speculating on a future but also of holding the United States accountable by identifying and spatially delineating the literal transfer of land holdings back to Indigenous peoples. In this way, mapping these lands and visualizing the landscape are key components in ensuring that decolonization is not a metaphor but a series of legal, political, social, and cultural actions in which reparations materialize in the landscape.

Acknowledgements

This essay was not written in isolation. It is the result of collaboration with many others. In particular, I owe my gratitude for the conversations about reparations that I have had with Anna Livia Brand, Jim Enote, Zannah Mæ Matson, Francesco Marullo, and Richard Misrach. Our discussions have been invaluable in developing these ideas at every stage of the thinking, writing, and editing. I especially express my appreciation to Jaclyn Tobia and Madeline Forbes who served as diligent, insightful, and exceptional collaborators on data collection, conceptual development, and production of the drawings and mappings, and without whom this essay would not exist.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Danika Cooper

Danika Cooper is an assistant professor of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, where the core of her research centers on the geopolitics of scarcity, alternative water ontologies, and designs for resiliency in the global aridlands. Aridlands have largely been underexplored in landscape architecture—her work offers multiple ways of knowing, being, and engaging with desert landscapes to better inform current environmental and landscape architecture discourse and practice. This is especially important as populations in these regions increase and as the climate becomes drier and hotter. Through her scholarship, Cooper traces the ways that nineteenth-century, Euro-Western environmental theories and ideologies continue to influence cultural perceptions, policy frameworks, and management practices within U.S. desert landscapes today.

Notes

1 Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 597 U.S. (2022).

2 McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. (2020).

3 Danika Cooper, “Legacies of Violence: Citizenship and Sovereignty on Contested Lands,” in Landscape Citizenships, ed. Tim Waterman, Jane Wolff, and Ed Wall (New York: Routledge, 2021), 226.

4 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U.S. (2022).

5 West Virginia v. EPA, 597 U.S. (2022).

6 Sara Safransky, “Land Justice as a Historical Diagnostic: Thinking with Detroit,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108:2 (March 4, 2018): 501, https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1385380.

7 Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Fatal Couplings of Power and Difference: Notes on Racism and Geography,” The Professional Geographer 54:1 (February 1, 2002): 16, https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00310.

8 Robert Nichols, Theft Is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2019), 117.

9 There is extensive research on counter-mapping. Here, I have listed only a few key sources. Joel Wainwright and Joe Bryan, “Cartography, Territory, Property: Postcolonial Reflections on Indigenous Counter-Mapping in Nicaragua and Belize,” Cultural Geographies, April 1, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474008101515; Martin Brückner, “Colonial Counter-Mappings and the Cartographic Reformation in Eighteenth-Century America,” XVII-XVIII. Revue de La Société d’études Anglo-Américaines Des XVIIe et XVIIIe Siècles 78 (December 31, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4000/1718.7160; Dallas Hunt and Shaun A. Stevenson, “Decolonizing Geographies of Power: Indigenous Digital Counter-Mapping Practices on Turtle Island,” Settler Colonial Studies 7:3 (July 3, 2017): 372–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2016.1186311; Penelope Anthias, “Ambivalent Cartographies: Exploring the Legacies of Indigenous Land Titling through Participatory Mapping,” Critique of Anthropology 39:2 (June 2019): 222–42, https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X19842920.//ic0//u8221{}{//i{}SettlerColonialStudies} 7, no. 3 (July 3, 2017

10 Kyle Whyte, “Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice,” Environment and Society 9 (2018): 134–35.

11 Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8:4 (December 1, 2006): 388, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

12 Rita Dhamoon, “A Feminist Approach to Decolonizing Anti-Racism: Rethinking Transnationalism, Intersectionality, and Settler Colonialism,” Rethinking Transnationalism 4 (2015): 32.

13 Ned Blackhawk, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008) 9.

14 Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2018), 24.

15 Many in legal studies, geography, and planning have written extensively on this topic. A few of note are as follows: Lindsay G. Robertson, Conquest by Law: How the Discovery of America Dispossessed Indigenous Peoples of Their Lands (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/berkeley-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3051950; Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2014); Neil Brenner, Jamie Peck, and Nik Theodore, Afterlives of Neoliberalism (London: AA Publications, 2011); Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, reprint ed. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015).

16 Mishuana Goeman, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 157.

17 Kevin Bruyneel, Settler Memory: The Disavowal of Indigeneity and the Politics of Race in the United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021); Cooper, “Legacies of Violence”; Blackhawk, Violence over the Land.

18 Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Univ of Minnesota Press, 2008), 8.

19 Gordon, Ghostly Matters, 64.

20 Eve Tuck and C. Ree, “A Glossary of Haunting,” in Handbook of Autoethnography, ed. Stacey Holman Jones, Tony E. Adams, and Carolyn Ellis (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2013), 642.

21 Cheryl I. Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review 106:8 (1993): 1716, https://doi.org/10.2307/1341787.

22 Bhandar, Colonial Lives.

23 Danika Cooper, “Drawing Deserts, Making Worlds,” in Deserts Are Not Empty, ed. Samia Henni (New York: Columbia University Press, forthcoming 2022).

24 Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed. (London: Zed Books, 2012), 23.

25 Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2019); Denis Wood, Rethinking the Power of Maps, illustrated ed. (New York: The Guilford Press, 2010); Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women And The Cartographies of Struggle, 2006; J. B. Harley, “Maps, Knowledge, and Power,” in The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments, ed. Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988); D. W. Meinig and John Brinckerhoff Jackson, eds., The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979).

26 Barbara Young Welke, Recasting American Liberty: Gender, Race, Law, and the Railroad Revolution, 1865–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), quoted in Blackhawk, Violence over the Land, 8.

27 See Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America, reprint ed. (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2012).

28 “History of Railroads and Maps: Railroad Maps, 1828–1900,” Library of Congress, accessed July 28, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/collections/railroad-maps-1828-to-1900/articles-and-essays/history-of-railroads-and-maps/.

29 White, Railroaded.

30 “Rise of Industrial America, 1876 to 1900: Railroads in the Late 19th Century,” Library of Congress, accessed July 28, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/rise-of-industrial-america-1876-1900/railroads-in-late-19th-century/.

31 Dorceta E. Taylor, The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection, reprint ed. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2016), 123.

32 Taylor, Rise of the American Conservation Movement, 124.

33 Taylor, Rise of the American Conservation Movement, 123.

34 Justin Farrell et al., “Effects of Land Dispossession and Forced Migration on Indigenous Peoples in North America,” Science 374:6567 (October 29, 2021): eabe4943, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe4943; Lizzie Wade, “Native Tribes Have Lost 99% of Their Land in the United States,” October 28, 2021, https://www.science.org/content/article/native-tribes-have-lost-99-their-land-united-states.

35 Mishuana Goeman, “Land as Life: Unsettling the Logics of Containment,” in Native Studies Keywords, eds. Stephanie Nohelani Teves, Andrea Smith, and Michelle Raheja (University of Arizona Press, 2015), 71.

36 Goeman, “Land as Life,” 59.

37 Julian Burger quoted in Teves, Smith, and Raheja, 61.

38 Sara Safransky, “Land Justice as a Historical Diagnostic: Thinking with Detroit,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108:2 (March 4, 2018): 503–4, https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1385380.

39 Goeman, “Land as Life,” 71–89.

40 Katherine McKittrick quoted in King, The Black Shoals, 77.

41 Nick Estes, “The Red Nation: All Relatives Forever,” The Red Nation, accessed December 14, 2021, http://therednation.org/; Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance, illustrated ed. (London; New York: Verso, 2019); Stefan Kipfer, “Pushing the Limits of Urban Research: Urbanization, Pipelines and Counter-Colonial Politics,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36:3 (June 2018): 474–93, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818758328; South Atlantic Quarterly (2020) 119.2: 243–268, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8177747; Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance, 3rd ed. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017); Kyle Powys Whyte, “The Dakota Access Pipeline, Environmental Injustice, and US Settler Colonialism,” in The Nature of Hope, eds. Char Miller and Jeff Crane (University Press of Colorado, 2019), 320–37, https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607328483.c015.2021, http://therednation.org/; Nick Estes, {\\i{}Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance}, Illustrated edition (London\\uc0\\u8239{}; New York: Verso, 2019.

42 Tuck and Ree, “A Glossary of Haunting”; Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1:1 (September 8, 2012): 1–40.

43 Blackhawk, Violence over the Land, 3.

44 Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 13.

45 Simpson, As We Have Always Done; Mark Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor”; J. Angelo Corlett, Race, Racism, and Reparations (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003).

46 Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House (London, UK: Penguin, 2018).

47 Waziyatawin, “Colonialism on the Ground,” January 2, 2014, https://intercontinentalcry.org/colonialism-ground/.

48 There are many examples of using the technique of mapping to advocate for alternatives to a colonial imaginary. Listed here are just a few: Michael Hermann and Margaret Pearce, “‘They Would Not Take Me There:’ People, Places, and Stories from Champlain’s Travels in Canada 1603–16,” Cartographic Perspective 41-46:66 (2010); Patricio Dávila, ed., Diagrams of Power: Visualizing, Mapping and Performing Resistance (Eindhoven: Onomatopee, 2019); Sarem Nejad et al., “‘This is an Indigenous City; Why Don’t We See It?’ Indigenous Urbanism and Spatial Production in Winnipeg,” Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien 63:3 (2019): 413–24, https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12520; Vincent Brown, “Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760–1761: A Cartographic Narrative,” 2013, http://revolt.axismaps.com/; Claudio Saunt, “Invasion of America,” 2014, invasionofamerica.ehistory.org; Victor Temprano and Native Land Digital, “Native Land Digital,” Native-Land.ca, 2015, https://native-land.ca/. Accessed on July 1, 2022

49 David Remnick, “How Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Helped Remake the Literary Canon,” The New Yorker, February 19, 2022.