ABSTRACT

The study investigated the relationships among quality dimensions, three types of interactions (i.e. learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner interaction), perceived learning and learning satisfaction with flipped courses in the context of the flipped classroom based on the information system (IS) success model. In this study, the quality dimensions in the original IS success model were replaced by flipped learning platform quality, instructional video content quality, and teaching quality (i.e. instructor monitoring and instructor facilitation). The data from 70 participants were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling. The results indicate that all the quality dimensions have the influences on both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning through the mediation of learner-content interaction or learner-instructor interaction. Moreover, learner-learner interaction significantly influences perceived learning, but not learning satisfaction with flipped courses. Finally, a positive and direct link between perceived learning and learning satisfaction with flipped courses was found.

1. Introduction

The proliferation of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has transformed teaching and learning in higher education. While learning technologies and online learning environments can be used to deliver lecture content, the flipped classroom instructional model, which allows instructors to reverse in-class and at-home learning activities (Broman & Johnels, Citation2019), may potentially be used to facilitate learning satisfaction and effectiveness. However, substantial challenges that may impact negatively on student learning must be overcome to successfully adopt and implement this model. For example, traditional classroom educators transitioning to a flipped classroom approach have reported setbacks in terms of developing and implementing related strategies (Gopalan et al., Citation2018; Wang, Citation2017), which may result in significant variability in how this approach is implemented (Shi et al., Citation2020). Moreover, students who are accustomed to playing a passive role in traditional in-class lectures must take a more active role in the learning process under the flipped classroom approach (Sander et al., Citation2000).

Because of the extensive heterogeneity in designing and implementing flipped courses, the flipped classroom approach may not work well in all cases (Låg & Sæle, Citation2019). Learning satisfaction and perceived learning are widely considered to be both desired learning outcomes of instruction and indicators of how well the flipped classroom approach has been adopted. Relative to traditional teaching approaches, meta-analytic results have shown that the flipped classroom instructional model has either no effect on student satisfaction and perceived learning outcomes (e.g. van Alten et al., Citation2019) or a small positive effect on student satisfaction with courses (e.g. Låg & Sæle, Citation2019; Strelan et al., Citation2020a) and on learning performance in terms of class pass rates (e.g. Låg & Sæle, Citation2019). The need to examine the determinants and contributing factors of learning satisfaction and perceived learning in students in flipped classroom settings has been highlighted in multiple studies (e.g. Strelan et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Thus, further research to elicit a better understanding of the antecedents of learning satisfaction and perceived learning in the flipped classroom approach is imperative, as clarifying the crucial determinants of learning satisfaction and perceived learning outcomes in the context of flipped courses will be critical to helping educators efficiently implement the flipped classroom approach to maximize the educational benefits of students.

The widely used information system (IS) success model of DeLone and McLean (Citation1992, Citation2003) has been updated to predict and explain users’ satisfaction and behaviors related to technology, both of which positively influence the performance of a particular IS, and thus allow the IS success model to function as a measure of IS success (Al-Kofahia et al., Citation2020). The IS success model has been used in previous studies to explore the antecedents of learning satisfaction and perceived learning in the context of e-learning (e.g. Hsieh & Cho, Citation2011; Isaac et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2014; Y.-U. Wang et al., Citation2019). Its prior widespread use in studies of e-learning supports the IS success model as an appropriate theoretical foundation for investigating learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped classroom settings. However, the IS success model has only rarely been used to examine learning phenomenon in flipped classroom settings, even though the application and implementation of the flipped classroom has been supported mainly with online videos delivered in an online learning environment (Zhai et al., Citation2017). Moreover, e-learning research based on the IS success model has generally focused on either learning satisfaction (e.g. Isaac et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2018) or perceived learning (e.g. Wang et al., Citation2014; Y.-U. Wang et al., Citation2019). Hence, Y. Wang et al. (Citation2019) called for further investigating the flipped classroom model from the perspectives of learning outcomes and learner satisfaction.

In the IS success model, DeLone and McLean (Citation1992, Citation2003) identified system quality, information quality, and service quality as three IS-related quality dimensions that may impact user satisfaction. Corresponding to the original dimensions of IS-related quality in the IS success model, in this study, flipped learning platform quality, instructional video content quality, and teaching quality (i.e. instructor monitoring and instructor facilitation) were proposed as being closely related both to learning satisfaction with flipped courses and to perceived learning in flipped courses. In flipped classroom settings, students are required to preview and study instructional video lectures and other related course materials on the flipped learning platform prior to attending class. Problems with the qualities of flipped learning platform and instructional video content have been commonly reported in flipped courses (Akçayır & Akçayır, Citation2018), and may negatively affect the flipped learning experience. Furthermore, instructors play an important role in shaping the flipped learning experience of students (Cho et al., Citation2021). Given the student-centered nature of the flipped classroom, instructors are expected to monitor and facilitate student learning and thus instructor monitoring and facilitation may be seen as critical elements of teaching quality in the flipped learning context. Although teaching quality may impact student learning quality, the influence of teaching quality on flipped learning has rarely been examined explicitly.

While there is a significant body of research evidence supporting the impact of interaction on learning (e.g. Bervell et al., Citation2020; Eom & Ashill, Citation2016, Citation2018; Lin et al., Citation2017), interaction has been identified as a key component of student learning (Moore, Citation1993; Wagner, Citation1997). Students learn better when they are able to interact effectively with the learning content, instructors, and other peers, regardless of learning environment (e.g. traditional classrooms, online learning settings). Thus, differences in levels of interaction within the flipped classroom may affect student learning. Because little attention has been paid to whether interaction affects the success of flipped classroom instructional model implementation, it is necessary to explore the relationship between interaction and student learning in the context of flipped classrooms. Therefore, this study was designed to examine the mediating role of three types of interactions (i.e. learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner interaction) in the relationship between quality dimensions and, respectively, learning satisfaction with and perceived learning in flipped courses.

After reviewing the literature related to flipped classrooms, the IS success model, and interaction, this study was developed to investigate learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in the context of the flipped classroom by considering how each interaction type (i.e. learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner interaction) mediate the related quality dimensions of flipped learning platform quality, instructional video content quality, and teaching quality. The two research questions of this study were to determine the following:

How did the quality dimensions influence learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped course settings through interaction?

How did perceived learning relate to learning satisfaction with flipped courses?

2. Theoretical foundations and hypothesis development

2.1. Flipped classroom instructional model

The flipped classroom instructional model, an alternative teaching strategy to the traditional teaching model, is a form of blended-learning instructional model that combines online and face-to-face course instruction (Milman, Citation2012). The flipped classroom instructional model reverses in-class teaching with at-home learning activities, with students learning new instructional content on their own time by watching lecture videos that instructors either pre-record or select from online sources and then engaging in instructor-facilitated, student-centered learning activities such as collaborative learning activities and problem-solving learning activities in class to cultivate higher levels of cognitive learning. Thus, the flipped classroom instructional model replaces the passive, didactic format of teaching with a student-centered learning atmosphere in the classroom (McCarthy, Citation2016). In flipped classroom learning, students have opportunities to take responsibility for their learning by interacting with instructors and peers and by self-directed learning to acquire and construct knowledge, while instructors are transformed from being didactic teachers to being facilitators who support pre- and in-class learning activities with more progress monitoring, scaffolding, guidance and personalized interaction scaffolding (McCarthy, Citation2016; Moffett, Citation2015).

Factors that potentially facilitate or hinder student learning in flipped classroom settings have been previously identified, including the instructional and technical quality of video production (Akçayır & Akçayır, Citation2018; McCarthy, Citation2016; Milman, Citation2012), video viewing conditions (Akçayır & Akçayır, Citation2018; Milman, Citation2012), and how and what students learn from the videos (Milman, Citation2012). Variations in these and other factors may have contributed to the contradictory findings reported in flipped classroom research. For example, although some studies have found students in flipped classrooms to perform better (e.g. Låg & Sæle, Citation2019; Strelan et al., Citation2020a) and have higher levels of satisfaction with courses (e.g. Låg & Sæle, Citation2019; Strelan et al., Citation2020a) than their peers in traditional classroom settings, other studies have found that students in flipped classrooms may not be more satisfied with the learning environment or achieve better perceived learning outcomes (e.g. van Alten et al., Citation2019) than their traditional classroom peers.

2.2. Interaction

Interaction refers to the occurrence of reciprocal events in which a student and his/her environment mutually impact one another during an attempt to change that student's behaviors to attain learning goals (Wagner, Citation1994). Interactions in various learning situations are considered crucial to constructing a meaningful learning experience (Bernard et al., Citation2009). Following Moore (Citation1989), interaction types may be classified as learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner, independent of whether interaction occurs synchronously or asynchronously.

Learner-content interaction refers to the cognition interaction between a student with learning materials with the goals of acquiring knowledge, deepening understanding, and changing perspectives or cognitive structures (Yılmaz & Karataş, Citation2017). Examples include watching videos, reading informational texts, completing assignments, and working on projects. In this study, learner-content interaction in the flipped classroom context focused on watching video lectures. The initiation and continuance of learner-content interaction depend on the autonomy and self-direction of students (Elyakim et al., Citation2019). However, in the literature on flipped classroom research (e.g. Akçayır & Akçayır, Citation2018; Mason et al., Citation2013; Merlin-Knoblich & Camp, Citation2018; Milman, Citation2012), students in flipped classrooms have frequently highlighted being able to flexibly and repeatedly watch sections of videos that were unclear to them as a benefit of using video lectures.

Learner-instructor interaction has been defined as interaction between a learner and an instructor that is initiated by the student or instructor at any time prior to, during, or following teaching (Hirumi, Citation2002). During the learning process, students need direction and feedback from instructors to ensure whether their understanding is correct, whether they employ proper learning strategies, and whether they learn how to apply learned knowledge in practice (Elyakim et al., Citation2019). Learner-instructor interaction allows instructors to gradually understand the individual learning needs and levels of students and then to customize their teaching and communication approaches to meet the unique learning needs of students (Hsieh & Cho, Citation2011). Importantly, this learner-instructor interaction also allows students to obtain better guidance, support, encouragement, and motivation from their instructor (Yılmaz & Karataş, Citation2017).

Rooted in social constructivism and cognitive conflict theory, learner-learner interaction refers to the exchanging and sharing of knowledge, ideas, and feedback among students. Interactions with peers in the classroom allow students to deepen their understandings of theoretical knowledge and of how to better apply theoretical knowledge in practice (McDuff, Citation2012). Although learner-learner interaction is desirable both for knowledge co-construction and motivational support, it is inadequately developed in traditional course settings (Bernard et al., Citation2009).

In a systematic review of the literature on the flipped classroom approach conducted by Akçayır and Akçayır (Citation2018), increased opportunities for learner-learner and learner-instructor interaction were identified as a positive feature of flipped classrooms. Different from the learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction that occur in learning conducted entirely online, flipped classroom includes face-to-face interaction among students and between students and instructors (Bernard et al., Citation2009). The more time that is available for in-class learning activities in the flipped instructional model offers opportunities for more frequent learner-instructor and learner-learner interactions.

2.3. IS success model

DeLone and McLean’s (Citation2003) IS success model was used as the theoretical foundation in this study to investigate the factors that contribute to the success of the flipped classroom instructional model. In the IS success model, quality dimensions including information quality, service quality, and system quality may impact IS use and user satisfaction and lead to certain net benefits. This model has been used widely in studies across different disciplines to investigate the success of adopting different types of information systems (e.g. Rouibah et al., Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2018; Y.-S. Wang et al., Citation2019) and usage behaviors with regard to e-learning system and tools (e.g. Hsieh & Cho, Citation2011; Isaac et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2014; Y.-U. Wang et al., Citation2019). Although Salem and Salem (Citation2015) suggested that the IS success model may be adapted to understand a new e-learning context, this model has not previously been adapted to explore the success of flipped classroom adoption.

Revisions to the constructs of the DeLone and McLean’s (Citation2003) IS success model were necessary to fit the flipped classroom context. In the flipped classroom literature, Cho et al. (Citation2021) found associations between the learning experience in flipped classrooms and, respectively, the quality of preview learning materials, interaction, and teaching behaviors. Therefore, in this study, the three quality dimensions of system quality, information quality and service quality in the IS success model were converted into the following three new constructs: flipped learning platform quality, instructional video content quality, and teaching quality (i.e. instructor monitoring and instructor facilitation). In addition, although not originally included in the IS success model, three types of interactions (i.e. learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner interaction) were added to the model as mediators. Furthermore, reflecting the goal in this study of identifying factors affecting the success of the adapted flipped classroom instruction model, the outcome variables were substituted with learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning.

2.4. The influence of perceived learning on learning satisfaction with flipped courses

Perceived learning has been defined as the extent to which students believe and feel that they have learned from a learning experience (Lin, Citation2016), while learning satisfaction with flipped courses may reflect the subjective evaluation of students of the positive and negative aspects of using the flipped classroom instruction model. Previous studies have shown that perceived learning is an antecedent factor of student satisfaction (e.g. Eagleton, Citation2015; Eom & Ashill, Citation2018; Lohmann et al., Citation2019; Mohamed & Lamia, Citation2018). For example, Mohamed and Lamia (Citation2018) found that students with higher perceived impact on learning were more satisfied with flipped classroom use. Likewise, Eom and Ashill (Citation2018), Lohmann et al. (Citation2019), and Eagleton (Citation2015) demonstrated perceived learning as a likely contributor to learning satisfaction in e-learning. Thus, in this study, it was hypothesized that students with better perceptions regarding how much they had learned from flipped courses would be more satisfied with their experience attending a flipped course, as follows:

H1: Perceived learning positively influences learning satisfaction with flipped courses.

2.5. The influence of interaction on perceived learning and learning satisfaction with flipped courses

Empirical studies of learning satisfaction may be affected by all three types of interactions during the e-learning process. For instance, Bervell et al. (Citation2020) found that online learning satisfaction was significantly predicted by learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction, and learner-learner interaction. However, the results of Lin et al. (Citation2017) showed that learner-instructor and learner-content interactions had significantly positive effects on learning satisfaction, whereas learner-learner interaction did not affect learning satisfaction. Moreover, Kuo et al. (Citation2014) found that learner-content interaction was the only one of the three types of interactions to contribute significantly to learning satisfaction. In addition, Eom and Ashill (Citation2016) found that higher levels of perceived learner-learner and learner-instructor dialogs in online courses were associated with significantly higher levels of learning satisfaction.

Moreover, researchers have studied the influences of the different interaction types on perceived learning in e-learning. For example, Lin et al. (Citation2017) found learner-content interaction to be the only interaction type to affect perceived progress. However, Eom and Ashill (Citation2016, Citation2018) found that higher levels of perceived learner-learner and learner-instructor dialogs in online courses were associated with significantly higher levels of perceived learning outcomes. Likewise, Kang, and Im (Citation2013) found that learner-instructor interaction significantly predicted perceived learning. Recently, Quadir et al. (Citation2019) found that learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction, and learner-learner interaction each contributed significantly to subjective learning outcomes.

Thus, in this study, all three types of interactions were hypothesized to encourage learning satisfaction with flipped courses and to increase perceived learning in flipped courses, as follows:

H2: Learner-content interaction positively influences learning satisfaction with flipped courses.

H3: Learner-instructor interaction positively influences learning satisfaction with flipped courses.

H4: Learner-learner interaction positively influences learning satisfaction with flipped courses.

H5: Learner-content interaction positively influences perceived learning.

H6: Learner-instructor interaction positively influences perceived learning.

H7: Learner-learner interaction positively influences perceived learning.

2.6. The influence of learner-learner and learner-instructor interactions on learner-content interaction

With video lectures designed and uploaded by the instructor, learner-content interaction imparts new knowledge to learners. After students interact intellectually with video lectures, they may have inquiries and misunderstandings that require their searching for answers and corrections from instructors (Bervell et al., Citation2020) or discussion with peers. Additional social interactions may be stimulated as their instructor addresses those asked questions and misconceptions and provides additional explanations and clarifications to all of the other students. Moreover, students must use the knowledge learned from video lectures to participate in in-class learning activities, which require learner-instructor and learner-learner interactions. Thus, learner-content interaction provides learners a starting point for more interactions with instructors and/or peers. In Bates and Ludwig (Citation2020) and Ishak et al. (Citation2020), students reported that previewing lectures ahead of time had them prepared for what would be discussed in the classroom and ready to participate and answer questions in in-class learning activities. Moreover, a study conducted by Bervell et al. (Citation2020) found learner-content interaction to be positively and significantly related to both learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction. Thus, in this study, learner-content interaction was hypothesized to increase learner-instructor and learner-learner interactions in flipped classrooms, as follows:

H8: Learner-content interaction positively influences learner-instructor interaction.

H9: Learner-content interaction positively influences learner-learner interaction.

2.7. The influence of quality dimensions on interaction

2.7.1. The influence of flipped learning platform quality on interaction

In the context of flipped classrooms, the flipped learning platform is a medium for distributing instructional videos and other related course materials produced / selected by instructors. Students are required to use the flipped learning platform to watch those video lectures and read course materials to learn fundamental knowledge on their own before attending the class. Thus, similar to system quality, flipped learning platform quality reflects the perception of students regarding the performance of the flipped learning platform and instructional video used in the flipped course from a technical perspective. A high level of flipped learning platform quality helps students easily access and watch video lectures without technology problems and issues, enabling students to focus on learning. According to Y.-D. Wang (Citation2014), the technical features of an e-learning course influence both the willingness of students to rely on the related learning platform and the faith and confidence of students in their instructor to help them attain learning goals. Hence, higher quality flipped learning platforms may not only make students more willing to engage in learner-content interaction through more-frequent platform use and video-lecture viewing but also find their instructors being trustworthy, being able to stimulate more learner-instructor interaction (Govindarajan, Citation1991). Although a direct relationship between flipped learning platform quality and the three interaction types has not yet been reported in the literature, Eom and Ashill (Citation2016) presumed that learning platform quality may increase learner-instructor and learner-learner dialogues, thus increasing both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped courses. Thus, in this study, flipped learning platform quality was hypothesized to promote learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction in flipped classrooms, which thus enhances both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped courses, as follows:

H10: Flipped learning platform quality positively influences learner-content interaction.

H11: Flipped learning platform quality positively influences learner-instructor interaction.

H12: Flipped learning platform quality positively influences learner-learner interaction.

2.7.2. The influence of instructional video content quality on interaction

Video lectures provided to students before in-class sessions are used in the flipped classroom instructional model as the main medium for disseminating learning content regarding specific subject-matter-related knowledge and skills. Effective instructional design and presentations in these video lectures may create more effective and engaging learning experiences for students. Video lectures may negatively influence learning if students perceive these lectures as being poorly designed or presented in a manner that is boring, unhelpful, or non-engaging (Costley & Lange, Citation2017). Thus, information quality is converted into the instructional video content quality in flipped classrooms, reflecting the quality of instruction design and presentation of the video content selected or produced by the instructors for students to preview. Although no studies have examined the relationship between instructional video content quality and learner-content interaction, researchers have previously examined the relationship between content quality and, respectively, learner-instructor and learner-learner interactions. For example, Eom and Ashill (Citation2018) found that a higher level of course design quality, including the design quality of course materials, is associated with the promotion of learner-instructor and learner-learner dialogues. Thus, providing high quality instructional videos is critical to students learning course content and to applying this learning to in-class learning activities that require discussions and interactions with instructors and peers, which subsequently increase the likelihood of all three types of interactions and increase both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped courses. Accordingly, in this study, instructional video content quality was hypothesized to facilitate learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction, which subsequently improves both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped courses, as follows:

H13: Instructional video content quality positively influences learner-content interaction.

H14: Instructional video content quality positively influences learner-instructor interaction.

H15: Instructional video content quality positively influences learner-learner interaction.

2.7.3. The influence of teaching quality on interaction

Ensuring that students have completed the necessary prerequisite learning prior to coming to class and providing appropriate instructional facilitation were identified as important measures for instructors to implement an effective flipped classroom course (Long et al., Citation2017). When instructors are responsible for monitoring and facilitating student learning in the flipping learning context, teaching quality, including instructor monitoring and facilitation, replaces service quality. Instructor monitoring, which describes how well instructors keep track of student learning, has been identified as an effective teaching practice for student learning (Cotton, Citation1988) and is considered to be an essential aspect of teaching quality (Klieme et al., Citation2009; Kunter et al., Citation2007). The constant supervision of instructors over learning behaviors helps ensure students are actively engaged in learning, which facilitates the smooth flow of classroom activities (Brophy, Citation1999). The flipped classroom enables students to study course content prior to attending in-class courses and thus apply, integrate, and interact knowledge gained from pre-class learning during these courses. However, as instructors cannot know the status of student learning or the progress of individual students before in-class courses, in-class learning activities may not work as expected or facilitate effective learning (Long et al., Citation2017; Mohamed & Lamia, Citation2018).

On the other hand, based on constructivist perspectives that portray learning as a self-directed process (Corte, Citation2004), an instructor's effective facilitation of learning may be considered an important feature of teaching quality. Facilitation refers to the process of encouraging individuals to achieve personal goals by taking actions that align with their own perspectives and opinions (Kar, Citation2020). In the learning context, instructor facilitation is defined as how well instructors support and encourage their students to actively engage in their own learning (Neville, Citation1999). Examples of instructor facilitation include keeping discussions relevant to the current course topic, motivating and encouraging student participation in discussion, asking questions to help students better understand specific issues / topics (Hew, Citation2015), and motivating and guiding students to think on a higher level and to explore by themselves (Long et al., Citation2017). After comparing an active non-flipped classroom to an active flipped classroom, Jensen et al. (Citation2015) found that the active-learning style of instruction generated the most learning gains and instructor facilitation made students more active and engaged. Although the role of the instructor as facilitator is widely recognized as essential in the flipped classroom model, instructor facilitation has received little scholarly attention.

A study by Weinert and Helmke (Citation1995) found supportive control, including the frequent monitoring and facilitation by an instructor, to be associated with active involvement with learning tasks and subject matter. Moreover, Eom and Ashill (Citation2018) found a positive association between level of instructor activities, including facilitation and monitoring, and level of learner-instructor and learner-learner dialogs. Accordingly, in this study, both perceived instructor monitoring and instructor facilitation were posited as having positive effects on the three interaction types, which consequently increases both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped courses, as follows:

H16: Instructor monitoring positively influences learner-content interaction.

H17: Instructor monitoring positively influences learner-instructor interaction.

H18: Instructor monitoring positively influences learner-learner interaction.

H19: Instructor facilitation positively influences learner-content interaction.

H20: Instructor facilitation positively influences learner-instructor interaction.

H21: Instructor facilitation positively influences learner-learner interaction.

2.8. Research model

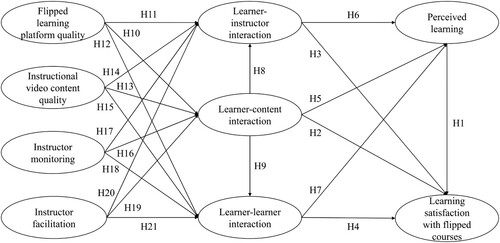

The aim of this study was to identify the factors that influence learning satisfaction with and perceived learning in flipped courses using DeLone and McLean’s (Citation2003) IS success model. The study examined how flipped learning platform quality, instructional video content quality, and teaching quality (i.e. instructor monitoring and instructor facilitation) affected both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning via three types of interactions (i.e. learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction, and learner-learner interaction). In addition, the influence of perceived learning on learning satisfaction learning satisfaction with flipped courses were also investigated. The proposed research model () was developed based on prior research and the hypotheses noted above.

3. Research methods

3.1. Participants and data collection

One hundred fifty-six participants were recruited via social media pages for this study. The study invited participants to complete a web-based questionnaire by following a link to a web-based questionnaire placed on a web page. To encourage participation, each respondent was gifted one lottery ticket after completing the questionnaire. Only the data from the 70 respondents who self-reported as having taken at least one university-level flipped course were included in the analysis. 35.2% of the participants were male and 64.8% were female; 40.8% were 18–20 years old, 49.3% were 21–25 years old, and 9.9% were 26–30 years old; 95.8% were undergraduate or graduate students and the remainder (4.2%) held undergraduate degrees; and the majority of participants who were currently enrolled students were seniors (30.9%), followed by freshmen (13.2%), sophomores (11.8%), juniors (23.5%), and graduate students (20.6%).

3.2. Measures

A substantial portion of the measurement items was referenced from prior research, with adjustments made as needed to the original items based on the research context in this study. With the exception of demographic factors, all of the measurement items were scored using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

3.2.1. Manipulation check and course-related variables

Prior to filling out the questionnaire, two manipulation check items were used to ensure that the participant had taken a flipped course. One manipulation check item that provided a definition of a flipped course requested the respondent to check if they have taken a flipped course, and the other asked how many flipped courses they had completed. Participants who responded negatively to either having taken a flipped course or having completed a flipped course were not allowed to complete the questionnaire. The remaining participants were asked to provide the title of the flipped course that they had taken and which impressed them the most, the name of the flipped learning platform that was used in the course, and the average hours per week they had spent watching video lectures. They were then asked to complete the questionnaire based on their learning experience in the particular flipped course.

3.2.2. Learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning

The scale used to assess learning satisfaction with flipped courses was adopted from a previous empirical study (Zhai et al., Citation2017). Moreover, perceived learning was measured using six items developed based on Wu’s (Citation2020) learning effectiveness scale.

3.2.3. Interaction

With regard to the three interaction types, nine items modified from Shan (Citation2019) were used to assess learner-content interaction, six items developed based on Sun et al.'s (Citation2007) teacher-student interaction scale were used to assess learner-instructor interaction, and five items from Wu’s (Citation2011) learning participation scale were used to assess learner-learner interaction.

3.2.4. Quality dimensions

To assess flipped learning platform quality, seven items were adopted from Yang et al. (Citation2017), Naaj et al. (Citation2012), and Chung (Citation2017). Instructional video content quality was evaluated using a six-item scale adopted from Cho et al.'s (Citation2021) student perception of preview materials scale (one item), Chien’s (Citation2018) e-learning material quality scale (four items), and Y.-S. Wang et al.'s (Citation2014) content quality scale (one item). Instructor facilitation was evaluated using a four-item scale adopted from Cho et al.'s (Citation2021) teacher facilitation scale. Instructor monitoring was evaluated using one item from Cho et al.'s (Citation2021) teacher facilitation scale and three items developed by the researchers involved in this study.

3.3. Data analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS was used to test the measurement validation and the structural model. Following Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988), a two-stage approach to data analysis was adopted in this study, with the first step performed to the measurement model by testing the validity and reliability of the research constructs. Standardized item loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to test the convergent validity and heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations to examine discriminant validity. Moreover, composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach's alpha were used to assess the internal consistency reliability of the research construct. The second step was performed to test the statistical significance of the structural relationships among the research constructs by running a bootstrap procedure with 5,000 bootstrap resamples.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

In terms of the types of flipped learning platforms used in flipped courses, most participants (42.9%) used social media websites (i.e. YouTube, Facebook, and Google Hangouts), 21.4% used open courseware (i.e. Coursera, NTU OpenCourseWare, NCTU OpenCourseWare, NCUE Could Course and NetEase), 17.1% used MOOCS (e.g. TAIWANMOOC and edX), and 15.7% used learning management systems (i.e. Moodle, MyELT, and iLearning). YouTube was by far the most frequently reported platform used by the participants in this study (38.57%). Regarding the average hours per week participants spent watching video lectures on their flipped learning platform, 20% of the participants reported spending an average of less than 30 min per week watching flipped-course video lectures, while 30% spent more than 30 min and less than one hour, 20% spent more than one hour and less than one and a half hour, and 25.7% spent more than one and a half hour. However, 4.3% reported not watching any video lectures for their flipped course.

4.2. Measurement model

After several bootstrapping runs, the HTMT ratios of the correlations were found to exceed the recommended criterion of 0.90 proposed by Henseler et al. (Citation2015). Eliminating the cross-loaded items and items with factor loadings below .6 improved overall discriminant validity. To assess measurement quality, the standardized item loadings, AVE, HTMT ratio of correlations, CR, and Cronbach's alpha were checked for all constructs. As shown in , all of the CR values were between .84 and .96 and all of the Cronbach's alpha values were between .71 and .91, which respectively exceeded the required values of .70 (Hair et al., Citation2012) and thus support the internal consistency of the indicators for each construct. Furthermore, the data also satisfied convergent validity through all factor loadings for each indicator on its corresponding latent construct by exceeding the benchmark of .60 (Afthanorhan et al., Citation2020; see ) as well as the AVE by each construct exceeding the benchmark of .50 (Hair et al., Citation2012; see ). Lastly, as shown in , the HTMT ratio of the correlations were less than 0.90, which satisfied the conditions of discriminant validity.

Table 1. Composite reliability (CR), Cronbach's alpha, and average variance extracted (AVE).

Table 2. Measurement items and loadings.

Table 3. HTMT results.

4.3. Structural model and hypotheses testing

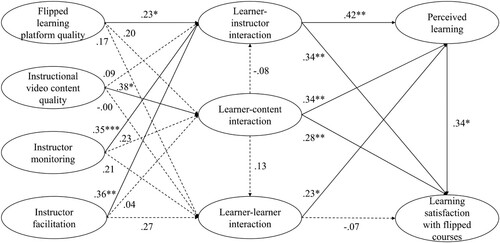

The results of the PLS analysis of the structural model are shown in . The paths from perceived learning to learning satisfaction with flipped courses were positive and significant (β = .34, p = .012), which supports H1. Moreover, both learner-content interaction (β = .28, p = .006) and learner-instructor interaction (β = .34, p = .007) were found to relate positively to learning satisfaction with flipped courses, supporting H2 and H3. Furthermore, perceived learning was found to associate positively with learner-content interaction (β = .34, p = .002), learner-instructor interaction (β = .42, p = .001), and learner-learner interaction (β = .23, p = .034), supporting H5, H6, and H7. Finally, flipped learning platform quality (β = .23, p = .043), instructor monitoring (β = .35, p < .001), and instructor facilitation (β = .36, p = .001) were found to relate positively with learner-instructor interaction, while instructional video content quality was associated with learner-content interaction (β = .38, p = .026), supporting H11, H13, H17, and H20 .

Figure 2. Results of PLS analysis.

Note. Solid lines represent significant predictive paths and dashed lines represent nonsignificant predictive paths. *p< .05, **p< .01, ***p< .001.

Table 4. Summary of structural model.

Furthermore, as all the quality dimensions had no direct effects on learner-leaner interaction, learner-leaner interaction could not mediate the relationships between quality dimensions ad perceived learning, as well as between quality dimensions and learning satisfaction with flipped courses in the research model of the study. Thus, it was excluded from the mediation testing. The mediating effects of learner-content interaction and learner-instructor interaction were examined by 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) with 5000 bootstrap samples. According to Hair et al. (Citation2017) and Kim et al. (Citation2017), evidence of mediation is provided while the confidence interval does not include zero for indirect effects. The results verified that the mediation effects of learner-content interaction for the relationships between instructional video content quality and learning satisfaction with flipped courses (effect = .11, 95% CI = [.017, .254]), as well as between instructional video content quality and perceived learning (effect = .13, 95% CI = [.050, .256]), were significant. Moreover, learner-instructor interaction significantly mediated the positive influences of flipped learning platform quality (effect = .08, 95% CI = [.001, .209]), instructor monitoring (effect = .12, 95% CI = [.024, .258]), and instructor facilitation (effect = .12, 95% CI = [.037, .252]) on learning satisfaction with flipped courses. Additionally, learner-instructor interaction significantly mediated the positive influences of flipped learning platform quality (effect = .10, 95% CI = [.008, .228]), instructor monitoring (effect = .15, 95% CI = [.035, .308]), and instructor facilitation (effect = .15, 95% CI = [.047, .299]) on perceived learning.

In this study, the model explained 53.9% of the variance in learner-content interaction, 64.6% of the variance in learner-instructor interaction, 41.9% of the variance in learner-learner interaction, 68.4% of the variance in perceived learning, and 62.2% of the variance in learning satisfaction with flipped courses.

5. Discussions

This study contributes to the literature by proposing and empirically assessing the success achieved in adopting the flipped classroom instructional model based on the IS success model proposed by DeLone and McLean (Citation2003). In this study, learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning were introduced as measures of success in flipped classroom settings, and new measures of flipped learning platform quality, instructional video content quality, and teaching quality were developed as quality dimensions. Moreover, following the recommendations of Moore (Citation1989), three types of interactions were investigated as mediating variables, considering learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner interactions. The influences of these quality dimensions and interactions were examined in this study to help explain learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped classrooms.

5.1. Perceived learning, learner-content interaction, and learner-instructor interaction directly impact learning satisfaction with flipped courses

In this study, the most crucial factors affecting learning satisfaction with flipped courses were perceived learning, learner-content interaction, and learner-instructor interaction. These three factors were shown to directly affect learning satisfaction with flipped courses, while perceived learning was shown to have the most significant direct impact on learning satisfaction with flipped courses. This finding is similar to the results of Eom and Ashill (Citation2018), Eagleton (Citation2015), Lohmann et al. (Citation2019), and Mohamed and Lamia (Citation2018), who found that enhanced perceived learning leads to better learning satisfaction in the e-learning context. These findings indicate that students with positive perceptions of perceived learning were satisfied with the flipped classroom instructional model used in their courses. Moreover, the findings also confirmed that learner-content interaction and learner-instructor interaction had significantly positive effects on learning satisfaction with flipped courses, which echoed the findings of other studies, including Bervell et al. (Citation2020) and. Lin et al. (Citation2017), which identified both learner-content interaction and learner-instructor interaction as significant predictors of learning satisfaction with flipped courses.

5.2. Learner-learner interaction has no direct impact on learning satisfaction with flipped courses

Although the findings in this study indicate that students with higher levels of interaction with content and instructors tend to be more satisfied with the flipped course, no evidence was found for a significantly direct influence of learner-learner interaction on learning satisfaction with flipped courses, which is inconsistent with the results of previous studies (e.g. Bervell et al., Citation2020; Eom & Ashill, Citation2016). According to Kuo et al. (Citation2014) and Lin et al. (Citation2017), a lack of required collaboration among students may not affect the influence of learner-learner interaction on learning satisfaction with flipped courses. One possible explanation for this is that interactional opportunities such as group discussions or collaborative activities designed within these flipped courses to promote substantive learner-learner interactivity may not be sufficient. Another possible explanation is that the collaborative learning activities employed in flipped courses require additional, detailed guidance from instructors to better address how learners should interact with each other to ensure benefits of collaborative learning and enhance learner satisfaction (Wang & Mu, Citation2017).

5.2. Interaction directly impacts perceived learning

All three types of interactions, including learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction, and learner-learner interaction, were found to directly affect perceived learning, which subsequently influenced learning satisfaction with flipped courses. The effects of learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction, and learner-learner interaction on perceived learning were shown in this study to be significant and positive. Learner-instructor interaction was found to have the greatest impact on perceived learning, followed by learner-content and then by learner-learner interaction. This indicates that learner-instructor interaction has a significantly positive effect on perceived learning, corresponding with the findings of Eom and Ashill (Citation2016, Citation2018), Kang and Im (Citation2013), and Quadir et al. (Citation2019). Moreover, the influence of learner-content interaction on perceived learning were found in this study to be significant and positive, similar to the findings of Lin et al. (Citation2017) and Quadir et al. (Citation2019). This finding is also in line with prior research by Eom and Ashill (Citation2016, Citation2018) and Quadir et al. (Citation2019) into the influence of learner-learner interaction on perceived learning. These findings imply that students who engage in more interactions with their instructor, video lectures, and other peers in the flipped courses are likely to have higher perceptions of how much they had learned.

5.3. Learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction have no direct impact on learner-content interaction

Contrary to Bervell et al. (Citation2020), learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction were not associated with learner-content interaction in this study. No significant impact of learner-content interaction on learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction may be an important issue to address, as it is generally expected that increased engagement in video lectures is important to building fundamental knowledge for interactions with instructors and peers, which will facilitate greater interactions with instructors and peers in flipped classroom settings (Xiao, Citation2017). One possible explanation is that students may have problems making the most effective and efficient use of subject matter knowledge learned from course materials or content in in-class discussions and learning activities that require interactions with instructors and peers. This suggests that steps must be taken by instructors to scaffold students into creating more direct connections between consumed video lecture content and interactions with instructors and peers.

5.4. Learner-instructor interaction is directly impacted by flipped learning platform quality and teaching quality, but not by instructional video content quality

In the current study, learner-instructor interaction was found to be predicted by both flipped learning platform quality and teaching quality (i.e. instructor monitoring and instructor facilitation), but not by instructional video content quality. These outcomes confirm the presumption of Eom and Ashill (Citation2016) that high learning platform quality may increase learner-instructor dialogue in the e-learning context and are also in good agreement with the result of Eom and Ashill (Citation2018) that emphasized the importance of instructor involvement in instructor monitoring on facilitation of learner-instructor dialog. In addition, this study found that flipped learning platform quality and teaching quality have indirect effects on both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning that are mediated by learner-instructor interaction. The findings imply that when students perceive flipped learning platforms as easy to use and watch video lectures uploaded to the flipped learning platform without technical difficulties or problems, their interactions with instructors tend to increase. Moreover, this increased learner-instructor interaction may also be driven by positive student perceptions regarding the trustworthiness of the instructor who provided them with the problem-free flipped learning platform and instructional videos. Hence, these findings suggest that instructors may promote interaction with students through increased monitoring of learning progress and effectiveness; facilitation of course-related interaction; and encouragement of inquiry, discussion, and interaction. Taken together, students who perceive higher levels of flipped learning platform quality and teaching quality will interact more with their instructors, leading to increased learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning. However, the finding regarding no significant relationship between instructional video content quality and learner-instructor interaction is conflicting to that of Eom and Ashill (Citation2018) who demonstrated that high quality in course design and course materials facilitates learner-instructor dialogue.

5.5. Learner-content interaction is directly impacted by instructional video content quality, but not by flipped learning platform quality and teaching quality

Although the relationships between learner-content interaction and the three quality dimensions have not been previously reported in the literature, the findings of this study indicate that learner-content interaction is the only significant predictor of instructional video content quality. Moreover, this study also found that instructional video content quality has an indirect effect on both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning mediated through learner-content interaction. Surprisingly, the study found that there was no relationship between learner-content interaction and, respectively, flipped learning platform quality and teaching quality. Thus, in this study, the instructional video lectures that completely covered the learning goals for each class session, that were clear and understandable, and that were logically ordered and presented were found to be positively associated with increased learner interaction with the video lectures, which in turn were related with increased learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning.

5.6. Learner-learner interaction is not directly impacted by all quality dimensions.

Unexpectedly, none of the three quality dimensions were found to play an important role in promoting learner-learner interaction in the current study. These findings are contradictory to Eom and Ashill’s (Citation2016) view that dialogue among learners in the e-learning context may be promoted by higher quality learning platform, and are divergent from previous research by Eom and Ashill (Citation2018), who found that quality in course design and course materials and instructor involvement in instructor monitoring may be critical to facilitation of learner-learner dialog. Possible reasons for this include infrequent use of online tools for group activities (e.g. discussion boards) on the flipped learning platform, insufficient interactive attributes in designed video lecture content, and less instructor monitoring and facilitation associated with sufficiently promoting learner-learner interaction. These findings highlight a need for further investigation and research to determine the quality dimensions related to promoting learner-learner interaction in flipped classrooms.

5.7. Implications

The following theoretical implications may be drawn from the empirical findings of this study. First, this study contributes to the literature by proposing and empirically assessing the successful implementation of the flipped classroom instructional model. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this was the first empirical research to investigate this relationship in the flipped learning context using an integration of a revised IS success model and interaction. The extended IS success model of DeLone and McLean (Citation2003) used in this study explained 62.2% of the variance in learning satisfaction with flipped courses and 68.4% of the variance in perceived learning, showing a moderate degree of explanatory power (Huang, Citation2021). The empirical findings of this study provide considerable support for the applicability of this research model in the flipped learning context and also confirm the importance of the investigated quality dimensions and three types of interactions as key contributing factors to enhancing learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped classrooms. Second, many researchers consider interaction as a crucial factor affecting student learning (e.g. Bernard et al., Citation2009). The mediating role of interaction in flipped classroom settings was partially confirmed in this study. Evidence was found to fully support the relationship between interaction and perceived learning, but only partially support the relationship between interaction and learning satisfaction. This suggests that the three types of interactions contribute unequally to learning satisfaction with flipped courses, providing further insight into which type of interaction plays a more important role in facilitating learning satisfaction with flipped courses. Moreover, this study adds to the understanding of and insight into the direct impact of different triggering factors on the three types of interactions in the flipped learning context. The triggering factors proposed in the study were found to impact learner-content and learner-instructor interactions only and not to impact learner-learner interaction. Third, the study discovered that each quality dimension plays an important role in learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning. All the quality dimensions indirectly affect learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning via learner-content interaction or learner-instructor interaction, indicating the enhanced roles of quality dimensions in the flipped learning context.

The findings of this study have important, practical implications for using the flipped classroom instructional model in teaching and learning. First, the educational benefits of watching instructional video lectures and interacting with instructors and peers identified in this study are helpful for instructors looking to use interactive activities to increase and improve student interactions with their learning content, instructors, and peers and to ensure that students engage in all three types of interactions. Second, instructors should verify the quality and performance of the flipped learning platform and the technical attributes of viewing the video lectures, as well as strategically provide facilitation and monitor progress to promote more interactivity with students. Moreover, the instructional design of the video lectures, including providing sufficient coverage of the learning goals for each class session, being clear and understandable, and being logically ordered and presented, should be optimized by instructors and course designers to help increase student interactivity with the video lectures.

6. Limitations and suggestions for future study

Knowledge regarding the determinants of learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped classroom settings was extended in this study. However, several limitations and suggestions for further research should be noted. First, a limited sample size was recruited using convenience sampling, which may limit the generalizability of findings. Future studies on this subject should use larger sample sizes and use a probability sampling approach. Second, the use of self-reported data may result in the introduction of recall and other biases. The researchers were unable to verify how accurately participant responses matched their actual flipped learning experience. Future research may consider collecting data immediately after each flipped course or incorporating additional data such as qualitative data or learning logs stored in flipped learning platforms to obtain the most-accurate information possible from participants. Furthermore, objective measures of learning outcomes rather than the subjective measure of learning outcomes such as perceived learning used in this study may be developed and used in future studies. Also, although learning satisfaction was treated as a unidimensional construct in this study, this variable has been operationalized in recent studies (e.g. Karaoğlan Yılmaz, Citation2021) as a multidimensional construct. Future studies may consider using a multidimensional measure capable of capturing a comprehensive picture of learning satisfaction in the flipped learning context. Third, course design, which is known to significantly impact learning experience (e.g. Eom & Ashill, Citation2018), was not examined in the study. Future research should collect information on the characteristics of in-class and out-of-class flipped course activities and investigate the related characteristics. Fourth, the empirical results in this study demonstrated that the investigated quality dimensions had no impact on learner-learner interaction. Future research may extend the inquiry into this issue by examining other quality dimensions that potentially affect learner-learner interaction in flipped classroom settings. Finally, an attempt was made in this study to assess the influences of several internal processing activities (i.e. learning-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction, and learner-learner interaction) on the flipped classroom. However, other motivational factors such as self-efficacy (Sun et al., Citation2018) and internal cognitive processes such as the use of self-regulation learning strategies (Sun et al., Citation2018) may also significantly impact learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped courses. The impact of motivational factors and other internal cognitive processes may be examined in future studies.

7. Conclusions

The factors that impact learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in the context of flipped courses were examined empirically in this study based on the IS success model of DeLone and McLean (Citation2003). This study extends scholarly understanding related to the successful adoption and implementation of flipped classrooms by linking related quality dimensions (i.e. flipped learning platform quality, instructional video content quality, and teaching quality) and three types of interactions (i.e. learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner interaction) to perceived learning and learning satisfaction with flipped courses. Specifically, this study explored the influences of quality dimensions on learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning in flipped courses through three types of interactions. Moreover, the impact of perceived learning in flipped courses on learning satisfaction with flipped courses was also examined. As hypothesized, perceived learning was found to relate positively to learning satisfaction with flipped courses; learner-content interaction was found to mediate the relationship between instructional video content quality and, respectively, learning satisfaction with and perceived learning in flipped courses; learner-instructor interaction was found to mediate the positive influences of flipped learning platform quality and teaching quality on both learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning; and learner-learner interaction was all found to relate positively to perceived learning. Therefore, increasing the learning satisfaction with flipped courses and perceived learning of students enrolled in flipped courses by promoting the three interaction types is critical to promoting the successful adoption and implementation of the flipped classroom instructional model. Learner-content interaction and learner-instructor interaction may be facilitated by ensuring the quality of the flipped learning platform, instructional video content, and teaching during both the design and implementation phases of the flipped classroom instructional model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Guan-Yu Lin

Guan-Yu Lin is a post-doctoral researcher at the National Changhua University of Education, Taiwan and was an assistant professor at the National Chung Cheng University, Taiwan. She received her Ph.D. in Information Science and Learning Technology from University of Missouri-Columbia, USA. Her research interests lie primarily within the broad field of online user behavior, and technology-enhanced learning, and interactive multimedia design. She has published papers in several academic journals, including the Computers and Education, British Journal of Educational Technology, Journal of Educational Computing Research, Online Information Review, among others.

Yi-Shun Wang

Yi-Shun Wang is a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Information Management at the National Changhua University of Education, Taiwan. He received his Ph.D. in MIS from National Chengchi University, Taiwan. His current research interests include IS success models, online consumer behavior, knowledge management, IT/IS adoption strategies, and e-learning. He has published papers in journals such as Academy of Management Learning and Education, Computers & Education, British Journal of Educational Technology, Interactive Learning Environments, Information Systems Journal, Information & Management, International Journal of Information Management, Government Information Quarterly, Internet Research, Journal of Educational Computing Research, Information Technology & People, Online Information Review, Computers in Human Behavior, among others. He is the former Chairman of the Research Discipline of Applied Science Education in the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

Yong Ni Lee

Yong Ni Lee is an IT specialist in the information service industry in Taiwan. She received her bachelor's degree in Information Management from National Changhua University of Education, Taiwan. Her current research interests include e-learning, mobile learning, educational technology adoption, and information systems success. She was a Principal Investigator of the College Student Project in the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan.

References

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., & Aimran, N. (2020). An extensive comparison of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for reliability and validity. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 4, 357–364. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2020.9.003

- Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education, 126, 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.021

- Al-Kofahia, M. K., Hassanb, H., & Mohamad, R. (2020). Information systems success model: A review of literature. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 12(8), 397–419.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Bates, D., & Ludwig, G. (2020). Flipped classroom in a therapeutic modality course: Students’ perspective. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 15(1), Article 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-020-00139-3

- Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkes, M. A., & Bethel, E. C. (2009). A meta- analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Review of Educational Research September, 79(3), 1243–1289. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309333844

- Bervell, B., Umar, I. N., & Kamilin, M. H. (2020). Towards a model for online learning satisfaction (MOLS): Re-considering non-linear relationships among personal innovativeness and modes of online interaction. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 35(3), 236–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2019.1662776

- Broman, K., & Johnels, D. (2019). Flipping the class - University chemistry students’ experiences from a new teaching and learning approach. Chemistry Teacher International, 1(1), Article 20180004. https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2018-0004

- Brophy, J. (1999). Perspectives of classroom management. In H. J. Freiberg, & J. E. Brophy (Eds.), Beyond behaviorism: Changing the classroom management paradigm (pp. 43–56). Alyn & Bacon.

- Chien, L.-Y. (2018). Effects of a flipped classroom for nursing students studying biostatistics: Changes in depth of learning. Journal of Teaching Practice and Pedagogical Innovation, 1(1), 119–153. https://doi.org/10.3966/261654492018030101003

- Cho, M., Park, S. W., & Lee, S. (2021). Student characteristics and learning and teaching factors predicting affective and motivational outcomes in flipped college classrooms. Studies in Higher Education, 46(3), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1643303

- Chung, T. (2017). The effects of SPOC and flipped classroom on college students’ learning achievement, learning attitude and learning satisfaction [Unpublished master’s thesis]. National University of Tainan, Taiwan.

- Corte, E. D. (2004). Mainstreams and perspectives in research on learning (mathematics) from instruction. Applied Psychology, 53(2), 279–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00172.x

- Costley, J., & Lange, C. H. (2017). Video lectures in e-learning: Effects of viewership and media diversity on learning, satisfaction, engagement, interest, and future behavioral intention. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 14(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-08-2016-0025

- Cotton, K. (1988). Monitoring student learning in the classroom (School Improvement Research Series Close-Up #4). https://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/monitoring-student-learning.pdf

- DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 60–95. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.3.1.60

- DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748

- Eagleton, S. (2015). An exploration of the factors that contribute to learning satisfaction of first-year anatomy and physiology students. Advances in Physiology Education, 39(3), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00040.2014

- Elyakim, N., Reychav, I., & McHaney, R. (2019). Perceptions of transactional distance in blended learning using location-based mobile devices. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(1), 131–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633117746169

- Eom, S. B., & Ashill, N. J. (2016). The determinants of students’ perceived learning outcomes and satisfaction in university online education: An update. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 14(2), 185–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12097

- Eom, S. B., & Ashill, N. J. (2018). A system’s view of e-learning success model. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 16(1), 42–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12144

- Gopalan, C., Bracey, G., Klann, M., & Schmidt, C. (2018). Embracing the flipped classroom: The planning and execution of a faculty workshop. Advances in Physiology Education, 42(4), 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00012.2018

- Govindarajan, G. (1991). Enhancing oral communication between teachers and students. Education, 112, 183–186.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hew, K. F. (2015). Student perceptions of peer versus instructor facilitation of asynchronous online discussions: Further findings from three cases. Instructional Science, 43(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9329-2

- Hirumi, A. (2002). A framework for analyzing, designing and sequencing planned e-learning. Interactions. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 3(2), 141–160.

- Hsieh, P. J., & Cho, V. (2011). Comparing e-Learning tools’ success: The case of instructor–student interactive vs. Self-paced tools. Computers & Education, 57(3), 2025–2038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.05.002

- Huang, C.-H. (2021). Using PLS-SEM model to explore the influencing factors of learning satisfaction in blended learning. Education Sciences, 11(5), 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050249

- Isaac, O., Aldholay, A., Abdullah, Z., & Ramayah, T. (2019). Online learning usage within Yemeni higher education: The role of compatibility and task-technology fit as mediating variables in the IS success model. Computers & Education, 136, 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.012

- Ishak, T., Kurniawan, R., Zainuddin, Z., & Keumala, C. M. (2020). The role of pre-class asynchronous online video lectures in flipped-class instruction: Identifying students’ perceived need satisfaction. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.33902/jpr.v4i1.145

- Jensen, J. L., Kummer, T. A., & Godoy, P. D. d. M. (2015). Improvements from a flipped classroom may simply be the fruits of active learning. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-08-0129

- Kang, M., & Im, T. (2013). Factors of learner–instructor interaction which predict perceived learning outcomes in online learning environment. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(3), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12005

- Kar, D. (2020). Community-based fisheries management: A global perspective. Academic Press.

- Karaoğlan Yılmaz, F. G. (2021). An investigation into the role of course satisfaction on students’ engagement and motivation in a mobile-assisted learning management system support flipped classroom. Technology, Pedagogy and Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2021.1940257

- Kim, W. H., Ra, Y.-A., Park, J. G., & Kwon, B. (2017). Role of burnout on job level, job satisfaction, and task performance. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(5), 630–645. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2015-0249

- Klieme, E., Pauli, C., & Reusser, K. (2009). The Pythagoras study: Investigating effects of teaching and learning in Swiss and German mathematics classrooms. In T. Janik & T. Seidel (Eds.), The power of video studies in investigating teaching and learning in the classroom (pp. 137–160). Waxmann.

- Kunter, M., Baumert, J., & Köller, O. (2007). Effective classroom management and the development of subject-related interest. Learning and Instruction, 17(5), 494–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.002

- Kuo, Y.-C., Belland, B. R., Schroder, K. E., & Walker, A. E. (2014). K-12 teachers’ perceptions of and their satisfaction with interaction type in blended learning environments. Distance Education, 35(3), 360–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.955265

- Låg, T., & Sæle, R. G. (2019). Does the flipped classroom improve student learning and satisfaction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. AERA Open, 5(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419870489

- Lee, S. J., Lee, H., & Kim, T. T. (2018). A study on the instructor role in dealing with mixed contents: How it affects learner satisfaction and retention in e-learning. Sustainability, 10(3), Article 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030850

- Lin, C.-H., Zheng, B., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Interactions and learning outcomes in online language courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(3), 730–748. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12457

- Lin, G.-Y. (2016). Effects that Facebook-based online peer assessment with micro-teaching videos can have on attitudes toward peer assessment and perceived learning from peer assessment. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 12(9), 2295–2307. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2016.1280a

- Lohmann, G., Pratt, M. A., Benckendorff, P., Strickland, P., Reynolds, P., & Whitelaw, P. A. (2019). Online business simulations: Authentic teamwork, learning outcomes, and satisfaction. Higher Education, 77(3), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0282-x

- Long, T., Cummins, J., & Waugh, M. (2017). Use of the flipped classroom instructional model in higher education: Instructors’ perspectives. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29(2), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-016-9119-8

- Mason, G. S., Shuman, T. R., & Cook, K. E. (2013). Comparing the effectiveness of an inverted classroom to a traditional classroom in an upper-division engineering course. IEEE Transactions on Education, 56(4), 430–435. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2013.2249066

- McCarthy, J. (2016). Reflections on a flipped classroom in first year higher education. Issues in Educational Research, 26(2), 332–350.

- McDuff, E. (2012). Collaborative learning in an undergraduate theory course: An assessment of goals and outcomes. Teaching Sociology, 40(2), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X12437968

- Merlin-Knoblich, C., & Camp, A. (2018). A case study exploring students’ experiences in a flipped counseling course. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(4), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12118

- Milman, N. (2012). The flipped classroom strategy: What is it and how can it be used? Distance Learning, 9(3), 85–87.

- Moffett, J. (2015). Twelve tips for “flipping” the classroom. Medical Teacher, 37(4), 331–336. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.943710

- Mohamed, H., & Lamia, M. (2018). Implementing flipped classroom that used an intelligent tutoring system into learning process. Computers & Education, 124, 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.011

- Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

- Moore, M. G. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. Theoretical Principles of Distance Education, 1, 22–38.

- Naaj, M. A., Nachouki, M., & Ankit, A. (2012). Evaluating student satisfaction with blended learning in a gender-segregated environment. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 11(1), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.28945/1692