ABSTRACT

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has gradually promoted blended teaching based on Small Private Online Course (SPOC) as a common teaching practice in most higher education institutions. Teachers play a critical role in the successful implementation of blended teaching. Questions regarding the factors that influence teachers’ implementation strategies for SPOC-based blended teaching in higher vocational colleges, positively or negatively, are raised. This research investigated 63 English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers from four higher vocational colleges in China who are implementing SPOC-based blended teaching, encoded the obtained data at three levels, explored factors influencing EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching, and constructed a theoretical model of the factors influencing teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching in which SPOC-based teaching intention is a pre-influencing factor, whereas the school incentive mechanism and curriculum platform satisfaction serve as situational influencing factors. This study can help EFL teachers improve the implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching and further optimise SPOC-based blended teaching policies and measures for stakeholders in practice.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has increasingly integrated online teaching into conventional teaching methods. A blended teaching mode based on Small Private Online Course (hereinafter SPOC) has thus gradually become a common teaching practice in most higher colleges and institutes globally. “The combination of SPOC and traditional teaching mode changes the student experience from ‘learning new information in class and asking questions outside class’ to ‘learning both in the classroom and online’”. This SPOC-based blended teaching model can improve the adjustment ability of teachers and the passing rate and participation of the learners (Fox, Citation2013). One of the key stakeholders in any effective integration of technology in teaching and learning is the teacher (Teo, Citation2011). However, some studies showed that teachers are unwilling to use Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and others do not use it effectively during the implementation of a new teaching mode because they resist change (Dashtestani, Citation2014; Salim et al., Citation2018). Although blended teaching is more effective than single online learning and classroom teaching, it has encountered difficulties in practice (Xu, Citation2016). Win and Wynn (Citation2015) report that 50% of the students were dissatisfied with blended learning implementation in engineering and law subjects, where three-fourths of them would rather have traditional classes. Although blended teaching has offered manyadvantages, most students still prefer traditional offline learning. Consequently, despite the immense importance attached to blended teaching in education, little effort has been made to assess how well teachers are prepared to use it (Rahman, Citation2014). The impact of the school on teachers and the resulting resistance to change in the process of promoting blended teaching reform cannot be underestimated and restricts its implementation.

The Ministry of Education (MOE) (Citation2007) in China has been encouraging English as foreign language (hereinafter EFL) teachers to use advanced technologies effectively in their teaching practice in higher education. However, EFL teachers in China are not using the available resources in language learning as envisioned by the MOE. They either have shown lacklustre responses towards using ICT resources in classrooms (Li & Walsh, Citation2010; Yang & Huang, Citation2008) or have used the resources in ways lacking innovation and creativity (Li, Citation2014); EFL teachers seem reluctant to respond actively to integrating technology into the foreign language classroom (Ma et al., Citation2020). In the SPOC-based blended teaching mode, EFL teachers’ role has changed from that of original knowledge imparter to that of designer, organiser and guide, and their attitude and skills become the key to its successful implementation. Indications of how well teachers are managing all the changes are still not clear even though the educational background has undergone a significant alteration and has influenced their teaching role (Smits & Voogt, Citation2017). Therefore, further research regarding EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching is needed. This research adopts the qualitative research mode of classical grounded theory, explores the factors influencing higher vocational college EFL teachers’ implementation of blended teaching based on SPOC, and constructs a theoretical model of the factors influencing EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching,aiming to provide basic theory and variable selection for the subsequent modelling research on the influencing factors of teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended learning. In theory, this research provides a new perspective for the understanding of factors influencing teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching, and enriches and develops the scope of qualitative research on it; in practice, it assists school administration in identifying specific needs of stakeholders before applying new measures, offers references for carrying out teacher training and policy support, and provides improvement and efforts for providers of blended teaching foreign language courses and designers of the learning platform. It is also expected to contribute to the effectiveness of SPOC-based blended teaching implementation and the quality of education for all universities in China and other countries with similar educational context.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Factors influencing teachers’ acceptance of blended teaching

Teachers’ acceptance of blended teaching is considered the key factor for its success (Apandi & Raman, Citation2020). Only when teachers really recognise its positive effects will they apply it (Zhao & Zhang, Citation2017). Some studies have discussed the factors that influence its acceptance by teachers. The merits of applying technology in blended learning will not be effective if teacher’ acceptance of and capability with ICT remain low (Teo et al., Citation2015; Yahya et al., Citation2012). Hew and Brush (Citation2007) reviewed the general obstacles that information technology and curriculum integration usually face in the United States and other countries, and found 123 obstacles. They further divided these obstacles into six categories—resources, knowledge and skills, institutions, attitudes and beliefs, assessment, and discipline culture. According to Venkatesh et al. (Citation2012), there are several factors that play a vital role in an individual’s intention to use technology. They incorporated three constructs into their Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and found significant roles of hedonic motivation, price value, and habit influencing technology use in UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al.’s later extension of UTAUT), tailored to the context of consumer acceptance and use of technology. Kabakci-Yurdakul et al. (Citation2014) added two variables of self-efficacy and use attitude based on the UTAUT model and developed a tool that can measure pre-service teachers’ acceptance and use of technology. This tool is entitled UTAUT-PST which includes 7 factors measured by 23 items: performance expectation, effort expectation, social impact, promotion condition, behaviour intention, self-efficacy and using attitude. Liu (Citation2018) established the influencing factor model of blended teaching for college teachers based on Diffusion of Innovation Theory. The structural equation results showed that the five factors of school support—feasibility, compatibility, comparative advantage and communication channel—significantly affect the willingness of college teachers to accept blended teaching. Antwi-Boampong (Citation2020) constructed a Faculty Blended Learning Adoption Model. identifying key factors, including pedagogy fitness, faculty technology affinity, student positive disposition to blended learning, and institutional readiness to lead positively to motivate faculty to adopt blended learning. Apandi and Raman (Citation2020) investigated the factors that affected the adoption of blended learning based on UTAUT2 and TPaCK and maintained that further modification of UTAUT2 with additional constructs that fit within the context of teacher and technology needs to be considered.

2.2. Factors influencing teachers’ implementation of blended teaching

The literature review found that a number of researchers studied the factors affecting teachers to conduct blended teaching. Bolliger and Wasilik (Citation2009) developed an online faculty satisfaction survey and administered it to teachers who taught an online course. The results showed that factors related to students, teachers, and institutions influence their satisfaction of teaching in an online environment. Abbas (Citation2016) used the structural equation modelling approach to propose a conceptual model investigating the impacts of three social factors on students’ intention to use e-learning in two different countries, and showed that interpersonal influence, external influence and instructor quality had significant effects on the Egyptian students’ behavioural intention to use e-learning platforms through the mediating variables of perceived ease of use, and usefulness. However, instructor quality was the only predictor which had a significant impact on the UK students’ behavioural intention. Porter and Graham (Citation2016) surveyed 214 faculty members at Brigham Young University-Idaho during the adoption and early implementation stage, and found that the availability of sufficient infrastructure, technological support, pedagogical support, evaluation data and an institution’s purpose for adopting blended learning would most significantly influence faculty adoption. Dintoe (Citation2019) studied factors influencing adoption and diffusion of ICT in universities of developing countries and found school administration and technology as important factors. He suggested that universities in developing countries understand the faculty as early adopters from a bottom up instead of a top-down approach to achieve successful outcomes. Bokolo (Citation2021) employed quantitative methodology to gather data from 188 e-learning directors, managers, and coordinators in institutions, and revealed that coercive, normative and mimetic pressures greatly influenced the blended learning implementation by faculty members. Chan (Citation2019) used questionnaires and focus group interviews to investigate 261 pre-service students and teachers engaging in a teacher education programme based on blended learning. The results showed that there is still some way to go before students fully participate in online learning, and teachers may not fully accept the blended teaching mode but will instead follow their traditional experience and methods. For example, teachers’ consciousness of and preparation for blended teaching are crucial. These include steps such as curriculum design, implementation and evaluation ability, resource acquisition (de los Arcos et al., Citation2016), processing ability (Li et al., Citation2018), and technology and curriculum integration ability (Zhu, Citation2017). Teachers’ previous blended teaching and technological application experience significantly enhances its successful development. Yeop et al. (Citation2019) used a survey questionnaire to investigate 720 teachers in Malaysia and showed that use expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions and teacher efficacy were significant factors affecting behavioural intention and use behaviour. The findings of empirical analysis also revealed that experience factors moderate the relationship between facilitating conditions and use behaviour factors. The overall design of blended teaching from the school management is not systematic and imperfect, the attention is not enough, the implementation is not reflected in the assessment of teachers, and the professional development and training opportunities provided by the school are not sufficient (Zhang & Zhu, Citation2016; Shi, Citation2017). Teachers’ acceptance and recognition of SPOC-based blended teaching determine whether they can really carry it out (Zhao & Zhang, Citation2017).

2.3. Factors influencing EFL teachers’ blended teaching in Chinese higher vocational colleges

Higher vocational colleges are a type of ordinary college in China, with full-time junior college- level higher vocational education as the main content. The educational programme is usually three years (General Office of the Ministry of Education, Citation2020). The newly revised Vocational Education Law of the People’s Republic of China came into force on 1 May, 2022, and confirms that higher vocational education is an education type with the same importance and status as undergraduate college education (Jin & Shi, Citation2022). EFL teachers in higher vocational colleges are responsible for teaching Vocational College English, which is a compulsory public course provided for first-year non-English-majors in higher vocational colleges. However, the academic performance and autonomous learning ability of students in higher vocational colleges are generally lower than those of students from undergraduate universities and colleges due to the different levels of higher education (Wang et al., Citation2021). Besides, higher vocational college students are generally not interested in language learning, and their ability and willingness to speak English need to be improved (Hu, Citation2008). Therefore, EFL teachers need to make more effort to make full use of the advantages of blended learning and fully improve students’ learning efficiency.

Previous researchers have studied the factors influencing EFL teachers’ implementation of blended teaching in the higher vocational colleges, and found that interaction and content enrichment (Jung, Citation2015), and EFL teachers’ insufficient ability to conduct effective teaching and their insufficient understanding of curriculum teaching (Wang & Ma, Citation2020) are the core factors restricting the implementation of blended teaching. Based on the technology acceptance model, Xu et al. (Citation2020) found that excellent teaching resources had a significant impact on perceived usefulness, interactive function of teaching platforms had a significant impact on perceived ease of use, and social environment had a significant impact on EFL teachers’ implementation attitudes through a questionnaire survey of 325 teachers in different vocational colleges during the epidemic period. Jiang (Citation2021) conducted a quantitative study on the influencing factors of the blended teaching of English listening and speaking in higher vocational colleges, and the results show that teaching resources, teachers’ information technology and teacher–student interaction have an important impact on the blended teaching. Li (Citation2021) explored the factors that affect the effective blended teaching behaviour of EFL teachersin higher vocational colleges, including teaching personnel, teaching platform, teaching conditions, and student factors. Bai (Citation2021) conducted research on blended teaching practice in Higher Vocational English for freshmen in higher vocational colleges and used quantitative testing method to study the factors affecting the blended teaching behaviour, the results show that teachers’ internal motivation and the level of teachers’ information technology are important factors affecting blended teaching.

Outcomes of previous research have assisted in identifying the key concepts, constructs, and core themes of how teachers adopt blended learning (Hoffman, Citation2013; Kasse et al., Citation2015). However, multiple studies have been conducted to explore the factors influencing how teachers adopt blended learning. Moreover, they have mostly used quantitative research methods, in which researchers establish a set of evaluation criteria based on existing theories or influencing factors. In such cases, it is easy to deviate from the research scheme design, data analysis and conclusion derivation process because of the researchers’ theoretical preconceptions and subjective interpretations. Grounded theory, as a method of qualitative research, establishes a theory based on empirical data, and researchers generally have no theoretical assumptions before the beginning of the study, hence, the discovery is often innovative (Strauss, Citation1987). Moreover, most previous studies take students in universities as research objects and few of them have conducted research on EFLteachers from higher vocational colleges, is why this study is necessary.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling, research subjects, and data collection

Sixty-three EFL teachers from four higher vocational colleges carrying out SPOC-based blended teaching in China’s Guangdong province were selected using the purposive sampling method. Among the respondents, there were 15 male teachers (23.80%), and 48 female teachers (76.19%). The interviewees were aged between 26 and 55 (see ), which is in line with the current age distribution of teachers in higher vocational colleges. Of the total interviewees, 11.11% had a bachelor’s degree, 76.19% a master’s degree, and 12.69% a doctor’s degree. The professional titles of the interviewees were distributed at all levels, of which the lecturers and associate professors were the majority, and the assistant lecturers and professors accounted for the smaller proportion. The distribution proportion is basically in line with the overall professional title distribution of teachers in the higher vocational colleges. Focus group interviews and one-on-one in-depth interviews were conducted.

Table 1. Open coding categorisation.

According to grounded theory, data analysis and collection must be conducted simultaneously (Glaser, Citation1992; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). The sample selection and data collection are guided by the questions arising from the analysis; that is, the determination of the number of samples is subject to theoretical saturation. In the initial stage of constructing the theoretical model, 48 EFL teachers were interviewed, including 7 focus group interviews with an average interview time of 110 min and 10 in-depth interviews of approximately 30 min each. The researcher conducted two group interviews, with an average interview time of 100 min for each, and three one-on-one in-depth interviews of about 30 min each. The focus group discussion was conducted in a relaxed and free environment in which the interviewees were willing to share their ideas and views.

Based on the purpose of the research and the concerns and views of EFL teachers about SPOC teaching, a semi-structured interview outline with three topics was formulated. This outline was composed of two parts: personal information, including teachers’ age, educational background, personal interests, and subjective questions to understand the motivation for SPOC teaching in the classroom, main factors affecting SPOC-based blended teaching, and experience of SPOC teaching. With the consent of the interviewees, the researcher recorded the interviews. The interview data were transcribed using a recording pen, and 14 pieces of text materials with more than 40,000 words of interview records were obtained. Then, the qualitative research data analysis software NVivo 12 (Chinese version) was used to sort and analyse the text data. After coding the text materials, no new theoretical categories emerged.

3.2. Research reliability and validity

This research was encoded by the researcher and checked by two professors in the education field to ensure its validity. The data’s authenticity, correctness, and reliability were ensured by using mutual evidence and comparing the data among respondents and focus groups. By constantly reflecting on the records, the researcher remained sensitive to the existing theories and theories presented in the original materials, and importance was attached to capturing new insights to build theories. Concurrently, the researcher shared the research process and preliminary conclusions with two colleagues and listened to their opinions. The researcher and one colleague measured the consistency of the text coding and found it to be 86.48% on average, indicating a reasonable degree of coding consistency, which confirms the reliability and validity of this research.

3.3. Research method

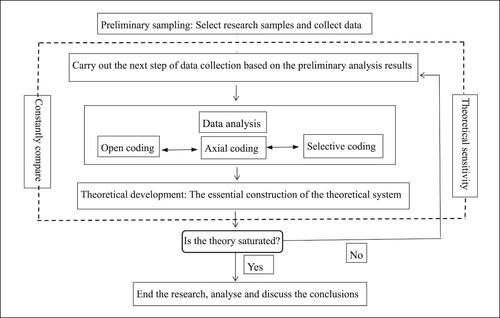

This study adopted the data coding method of grounded theory because the inductive research process of programmed grounded theory is widely used and easy to operate (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1994). The core of programmed grounded theory includes the triple coding analysis process of open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Coding means the continuous comparison between events and concepts to derive categories, form features, and conceptualise data (Mediani, Citation2017). shows the framework of the programmed grounded theory methodology.

Figure. 1. Framework of programmed grounded theory methodology (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1994).

4. Research procedure

4.1. Open coding stage

Focusing on the factors influencing EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching, the researcher sorted the texts without personal presupposition or bias to the degree possible. The primary interview text was encoded and labelled word for word to generate preliminary concepts and discover concept categories. Further, decomposing meaningful sentences allowed the researcher to merge those initial concepts with repetition or overlap in meaning. Because the number of preliminary concepts was high and there was a certain degree of overlap, it was necessary to subclassify the concepts according to their causality, similarity, type, and other relationships. The preliminary concepts with little repetition (fewer than three times) were eliminated during categorisation because of the large sample size. Thereafter, ten preliminary categories comprising more than 120 concepts were formed ().

4.2. Axial coding stage

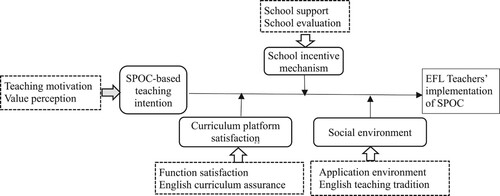

The axial coding stage analyses the relationship between categories as well as between categories and concepts and improves the generic relationship through continuous comparison. After summarising and analysing the 10 preliminary categories in , the researcher conceptualised 5 main categories: SPOC-based teaching intention, school incentive mechanism, curriculum platform satisfaction, social environment, and implementing behaviour. For example, SPOC-based teaching intention includes two preliminary categories, namely SPOC-based teaching motivation and value perception, which both indirectly affect teachers in conducting SPOC-based blended teaching (see ).

Table 2. Main categories formed by the axial coding.

4.3. Selective coding stage

In the final stage, the relationship between the preliminary and main categories formed a relatively clear structure ().

Table 3. Relationships between the categories.

4.4. Model construction

Among the 5 tree nodes on software NVivo, “teachers’ implementation of SPOC” had the largest number of data sources and reference points, which was much higher than that of the other three nodes, followed by “SPOC-based teaching intention”, “curriculum platform satisfaction”, “school incentive mechanism”, and “social-environmental impact”. The number of data sources and reference points of the “teaching motivation” node of the “SPOC-based teaching intention” category was the highest in the corresponding indicators. Therefore, we believe that “teachers’ implementation of SPOC” is the core category, and SPOC-based teaching intention is the main factor affecting EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC.

Based on the analysis, this study constructed the theoretical model of the factors influencing EFL teachers’ implementation of the SPOC, shown in . The theoretical model includes the following three aspects:

EFL teachers’ implementation of the SPOC works as the core category, and the other categories impact it.

SPOC-based teaching intention, the pre-influencing factor, represents teachers’ psychological factors, which directly impact the teaching behaviour of the SPOC.

The school incentive mechanism, curriculum platform satisfaction, and social tradition regulate the impact of SPOC-based teaching intention on the EFL teaching behaviour of the SPOC.

4.5. Theoretical saturation

Taking the theory initially generated in the data as the standard for further sampling, the researcher interviewed 15 EFL teachers to understand theoretical saturation. The data from these interviews were randomly selected and coded. The results agreed with the initial theory’s structural relationship, and no fresh categories were generated. Therefore, the theoretical model established in this research had reached saturation.

5. Discussion

Of the main factors influencing EFL teachers’ SPOC-based blended teaching behaviour, SPOC-based teaching intention directly affects EFL teachers’ implementation of the SPOC, while the other three factors are situational influencing factors that regulate the impact of teaching intention on EFL teachers’ SPOC-based blended teaching.

5.1. Analysis of the pre-influencing factor

SPOC-based teaching intention represents teachers’ psychological factors (Kuang et al., Citation2019; Jing et al., Citation2021), including SPOC-based teaching motivation and value perception. We find that teachers’ motivation influences their blended teaching behaviour, consistent with the results of Hew and Brush (Citation2007) and Ankit et al. (Citation2015). According to behavioural psychology, motivation is the dominant factor determining a person’s behaviour (Zhu & Deng, Citation2015). Teaching motivation impacts EFL teachers’ professional development, teaching interest, and attitude towards SPOCs. Teaching interest can increase EFL teachers’ mood and produce positive teaching behaviour. This can be seen from some representative comments of the teachers, such as “I am very interested in this SPOC, for the teaching can integrate the online learning and offline teaching, which is a creative way of English language teaching, and I hope this teaching mode will continue next semester”. Professional development refers to teachers’ hope to improve their teaching ability and professional knowledge using the SPOC. Professional development-based teaching motivation can raise teachers’ teaching enthusiasm and initiative and generate more investment in English teaching. For example, “I need to study the effect of online and offline blended teaching when applying for the research project on English teaching reform. I hope to have more teaching experience in this regard and provide research data to implement my teaching reform”. Teachers’ good attitude towards SPOC helps teachers maintain an open and inclusive attitude and creates a positive incentive to conduct SPOC teaching. For example, “SPOC is a great teaching method, which is conducive to the fair distribution of educational resources. I like this teaching method very much”.

Value perception refers to teachers’ perception of the expected benefits of SPOC teaching. The theory of rational behaviour holds that value, as the belief generated by human psychology, is the internal driving force for humans to produce a certain will (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1977). When teachers perceive that SPOC teaching generates value for themselves, it helps them become more effective (Wang & Liu, Citation2022). According to the interview data, teachers’ value perception is mainly reflected in social, identity, and knowledge values. The social value perceived by EFL teachers and actual value they generate during interpersonal interactions can help EFL teachers create a good teaching environment, stimulate teaching initiative and enthusiasm, enhance their sense of belonging to and identity with SPOC teaching, and produce positive teaching behaviour. For example, one EFL teacher mentioned: “I prefer to discuss problems with students in English on the learning platform after class, and the feedback can be audio or even video, which is attractive”. Wang (Citation2009) found that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use enhance students’ attitudes. Concerning identity value, one teacher said, “Students have achieved good course results by integrating online and offline classes. I feel a great sense of achievement”. This is the value of recognition perceived by EFL teachers. When teachers feel recognised for using SPOC, it stimulates their interest in teaching and enthusiasm to explore new knowledge. Finally, when teachers’ psychological awareness comes from their knowledge value, they think SPOC teaching is helpful, encouraging them to produce positive ideas and teaching behaviours.

5.2. Analysis of the situational influencing factors

5.2.1. School incentive mechanism

The school incentive mechanism regulates the relationship between SPOC-based teaching intention and teachers’ implementation of the SPOC from two aspects: school support and school evaluation. In line with Ngimwa and Wilson (Citation2012), Osman and Hamzah (Citation2017), Liu (Citation2018), and Antwi-Boampong (Citation2020), school support is an important factor influencing teachers’ behaviour. School support includes technical support, policy support, and a SPOC-based teaching environment. Technical support refers to technical training and the technical services provided by the school’s administration for teachers to conduct blended teaching (Apriska, Citation2020). A teacher’s knowledge of ICT affects their decision to adopt blended learning as a teaching tool (Kihoza et al., Citation2016). For example, one teacher said, “I major in liberal arts, and I am not good with technical issues. Technical services should be provided because I find it too complicated and labour-intensive to provide feedback; sometimes, I am unwilling to do that”. There were also pressing problems with integrating technology with pedagogy and subject teaching (Li, Citation2022). Policy support comes from the school’s management (i.e. the administrative requirements and relevant standards for teachers) (Bokolo, Citation2021; Dintoe, Citation2019). For instance, “We must carry out online and offline teaching modes in Vocational College English course because this is the policy formulated by the school”. The SPOC-based teaching environment includes peers’ attitudes and publicising the teaching effect. The teaching environment includes interactions with peers because learning is a social experience (Lee et al., Citation2017).

Corresponding with Hew and Brush (Citation2007), school evaluation is also a vital influencing factor. In this research, school evaluation includes the evaluation of teaching, students’ performance, and curriculum reform. For teaching evaluation, the in-depth interviews showed that teachers hope SPOC-based blended teaching can be recognised, respected, and even encouraged by the school and that the reward and teaching evaluation should be judged by their performance. Hoffman (Citation2013) agreed that school administrators in higher education seeking to increase teachers’ participation in online education ought to implement reward programmes. To evaluate students’ performance, some teachers also wanted guidelines for “how to assess students to reflect the advantages of blended teaching”. Regarding the evaluation of Vocational College English curriculum reform, one comment was that “we need to promote the English curriculum reform of SPOC-based teaching, which is a trend”.

5.2.2. Curriculum platform satisfaction

Curriculum platform satisfaction regulates the relationship between teachers’ teaching intention and teaching behaviour through function satisfaction and language curriculum assurance.

Function satisfaction refers to the functioning of the teaching platform, like the user interface, which can meet teaching needs. Zhao et al. (Citation2021) found that the curriculum platform was one of the four influencing factors on continuance learning behaviour, and Joo et al. (Citation2018) found that the user interface affects the use intention of online learning through perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. It is worth noting that user interface conditions impact the relationship between pre-influencing factors and the intention to continue blended learning. For example, a teacher said, “The user interface of the English teaching platform is simple and easy to operate, which is easier for me to use”. The language interactive function refers to the mutual communication and interaction between teachers and students around English curriculum teaching in the process of SPOC teaching. Social presence (Smith & Sivo, Citation2012) and interactive satisfaction (Xu et al., Citation2021) were found to be significant determinants of teachers’ intent to continue to use e-learning, which was supported by this research. In the process of communication with students, teachers can solve students’ questions in learning, improve learning effects, and make up for their poor learning consciousness. For example, “By asking questions online, I can answer students’ questions in time and increase students’ enthusiasm”. Zhao et al. (Citation2021) found that during teaching interactions, the stronger the sense of control and mutual assistance, the higher the SPOC-based teaching intention to continue a teaching behaviour, which is consistent with the results of this study. The diversified learning feedback function refers to the feedback judgement by teachers on students’ learning process or results through the learning platform, including after-school homework and in-class quizzes. This function can increase teachers’ teaching freshness and help raise their willingness to teach. In the interviews, the typical answer was “we can use audio or video to evaluate students’ homework. It’s a surprise”.

English curriculum assurance includes English curriculum content, English curriculum design, and English teaching resources. Bhuasiri et al. (Citation2012), Li et al. (Citation2018), and Dang (Citation2019) found that English curriculum content is an important factor for learning performance, which is supported by this research. Some EFL teachers believe that English curriculum content has strong timeliness and is updated rapidly; however, they are also concerned about whether it is suitable for SPOC-based online and offline teaching. For instance, “Students in higher vocational colleges generally have a weak sense of language learning motivation. They pay special attention to practical knowledge and show low interest in theoretical English knowledge learning; therefore, English curriculum content should be practical knowledge oriented”. Regarding English curriculum design, teachers are more concerned about arranging assignments, allotting time, and dividing online and offline teaching content. In the in-depth interviews, some teachers mentioned that if online English learning content is disconnected from classroom teaching content, teachers feel that the teaching logic and efficiency are affected, thereby influencing their teaching behaviour. Concerning English teaching resources, teachers pay attention to the selection and quality of such resources (de los Arcos et al., Citation2016; McLaren & Kenny, Citation2016; Zhu, Citation2017). The selection of English teaching resources rests on course content’s variation, importance, intellectual property, and sensitivity. For example, one teacher mentioned that “if online courses are rich in knowledge, moderate in difficulty, and attractive to higher vocational college students, they are more relaxed and efficient in offline teaching”.

5.2.3. Social environment

Social influence is a widespread social psychological phenomenon, and individuals’ attitudes and behaviours will change to a certain extent under the influence of the outside world (Xu et al., Citation2020). Social environment factors also impact the implementation of blended teaching (Ngimwa & Wilson, Citation2012; Kabakçı-Yurdakul et al., Citation2014; Ma & Lee, Citation2019; Xu et al., Citation2020). In this research, social environment impacts the relationship between teachers’ teaching intention and SPOC teaching behaviour from two aspects: application atmosphere and English teaching tradition, whose classification is different from social factors (interpersonal influence, external influence, and instructor influence) categorised by Abbas (Citation2016). Application atmosphere includes peer attitude, teaching atmosphere, and teaching effect publicity. Peer attitude is an important factor affecting students’ SPOC learning intention, which supports the research results of Xu (Citation2016) and Ma and Lee (Citation2019). Without peer support, teachers may find that the environment is not conducive to the implementation of teaching, so the development of SPOC teaching will have negative psychology. The teaching environment includes social events and interaction with colleagues because learning is a social experience (Lee et al., Citation2017). COVID-19 is a very important factor that triggered the spread of SPOC, for example, “we have to implement SPOC-based teaching mode because of the COVID-19”.

English teaching tradition includes traditional teaching thinking, English teaching behaviour, and English teaching evaluation. Traditions and norms refer to “customs and beliefs inherited in the relevant social context” (Kleijnen et al., Citation2009). Any change that goes against tradition or habits will lead to personal resistance to innovation. In education, teachers are used to the traditional offline classroom environment, which aligns with Chan’s (Citation2019) results. EFL teachers tend to use the traditional “teacher-centred” methods for blended teaching, for example, these methods consider that “the English course is more suitable for face-to-face teaching” and “the course is difficult and can’t be learned through online video, and what kind of teaching method is used should be based on the situation of students”. However, perfection is difficult to obtain if one is teaching facts and skills to students in higher vocational colleges using the conventional learning methods currently practiced (Mustapa & Ibrahim, Citation2015). Compared with the traditional learning environment, English teaching in the SPOC environment needs a combination of online and offline teaching. EFL teachers need to supervise students’ online learning process after class and give timely feedback. These will require EFL teachers to change their previous learning routines and habits, leading to resistance to the SPOC teaching mode: “I prefer the previous classroom English teaching mode, and now I’m not used to online and offline blended learning”.

6. Educational Enlightenment post-COVID-19

6.1. Promoting EFL teachers’ blended teaching from the perspective of stakeholders

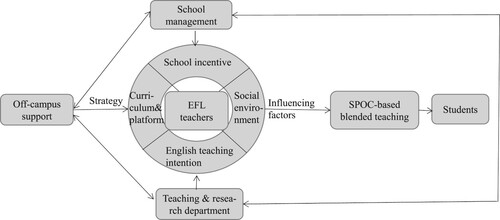

From the research results, the factors affecting EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC teaching post-COVID-19 are complex and diverse. The problems encountered by EFL teachers in the implementation need to be addressed by various stakeholders. The systematic framework of promoting SPOC-based blended teaching based on stakeholders is shown in .

The factors affecting EFL teachers conducting blended teaching include those, in preliminary categories of school incentive mechanism. The practices observed in the previous case study also shows thatschool management plays a vital role in promoting EFL teachers’ implementation of blended teaching (Bai & Han, Citation2019). Additionally, off-campus assistance can also be helpful, due to the limitations of a school’s teacher allocation, curriculum platform construction, and technical strength (Bai & Han, Citation2020). Moreover, SPOC-based teaching intention is the pre-influencing factor and represents teachers’ psychological factors, which directly impact teaching behaviour in the SPOC context. Therefore, the teaching and research department, as an important stakeholder, impacts the teachers’ implementation of SPOC. The school management, off-campus support, and teaching and research department adopt different strategies to help teachers conduct blended teaching. Through blended teaching and building and running blended courses, these factors will ultimately act upon students through English teaching. Stakeholders will adjust according to the situation of each curriculum or even each school. For example, some schools will have more active intervention from management departments, which will have a certain impact on teaching.

6.2. Meet the psychological needs of EFL teachers

According to the analysis, the researcher finds that EFL teachers’ implementation of the SPOC is directly affected by their psychological needs. Therefore, understanding EFL teachers’ motivation and valuing good teaching can fundamentally improve teachers’ enthusiasm for SPOC teaching.

6.2.1. Enhance teachers’ perception of teaching value based on English curriculum design

English curriculum design is a core focus of EFL teachers’ perception of SPOC teaching. When transforming traditional offline courses into SPOC-based blended teaching courses, they must be adopted by both online self-study teaching and offline teaching methods; such factors must be recognised at the time of offline and online teaching, distribution of content, and arrangement of extracurricular assignment and homework. In addition, teaching and research departments must pay attention to EFL teachers’ needs for a suitable teaching environment based on the language teacher characteristics. The best way to create a teaching environment based on SPOCs is to establish English teaching communities and incentivise the development of a SPOC-based teaching sharing platform (Jing et al., Citation2021).

6.2.2. Use technology to create new experiences for EFL teachers to implement SPOCs

With the support of 5G technology, online learning platforms can use artificial intelligence to create new teaching experiences and encourage teachers to continue to use them. For example, in the evaluation stage, English language interaction and speech recognition can be used to evaluate homework and answer questions, thus allowing EFL teachers to provide feedback to students promptly. In addition, computer vision, self-adaptation, and big data can be used to plan learning, push learning content, detect English pronunciation defects, and predict English learning results. This can reduce teaching pressure and assess students’ learning to improve English teaching outcomes and SPOC teaching experiences.

6.3. Adapt to the situational needs of English teaching behaviour

According to the above analysis, the situational influencing factors significantly regulate teaching behaviour. Therefore, depending on the situation and stakeholders, raising SPOC-based teaching intention focuses on improving EFL teachers’ implementation of the SPOC.

6.3.1. Promote EFL teachers’ implementation of the SPOC from the perspective of stakeholders

Some of the preliminary categories from the main category of the school incentive mechanism are closely related to the intervention of school leadership and the school’s administrative and service departments. Leadership plays a vital role in encouraging teachers to conduct blended teaching (Bai & Han, Citation2019), while off-campus assistance from curriculum and learning platform suppliers can also be helpful (Bai & Han, Citation2020). Therefore, the school’s management, administrative, and teaching and research departments, with support from outside, should adopt different strategies to encourage EFL teachers to pursue blended teaching. Furthermore, school management and platform providers should develop intelligent teaching aids to provide intelligent solutions and technical support for teachers to carry out SPOC teaching so that they can adjust and improve the English course content, interactive strategies, and English teaching activities according to the learning characteristics of higher vocational college students; indirectly enhance the English teaching experience; improve their perceived usefulness and teaching satisfaction; and maintain their continuous teaching intention.

6.3.2. Reconstruct teachers’ blended teaching knowledge and ability based on English curriculum design

English curriculum design factors are relatively complex and diverse, and EFL teachers’ blended teaching knowledge and ability should be reconstructed based on them. This can be done by breaking teachers’ habitual thinking and path dependence on the original classroom English teaching experience and ideas. EFL teachers should not promote the offline or online learning environment alone. A balanced relationship between the two should be emphasised based on students’ and teachers’ English curriculum design and understanding. Subsequently, teachers must enrich their English course content knowledge, technological ability, and ability to manage their class and time and become familiar with managing the network environment (Gedik et al., Citation2013). Additionally, the role of technology in blended teaching is regarded as a way for EFL teachers to update and seek knowledge constantly. Each teacher’s subject knowledge is incomplete and should adapt to change (Khan et al., Citation2016).

6.3.3. Strengthen the guidance and encouragement for EFL teachers to conduct blended teaching

It takes time for EFL teachers to change from traditional classroom teaching to using new technology in SPOC-based blended teaching. The “communication channel” is the main part of Rogers’ diffusion of innovations theory (Taherdoost, Citation2018). Under this theory, new technologies, ideas, and innovations can induce public recognition through certain channels. Indeed, one of the interviewed teachers mentioned “the need to be convinced by the blended teaching effect”. This shows that the SPOC-based teaching effects of the case school cannot reach all teachers and must be improved.

Accordingly, there are two ways to strengthen the guidance and encouragement for EFL teachers to implement blended learning successfully. First, encouragement and support from the teaching and research department should be differentiated and strengthened. Attention must be paid to the psychological factors of teachers; otherwise, it is difficult to obtain the desired results irrespective of the investment (Ertmer, Citation1999). Second, from the perspective of teachers’ motivation and recognition, teachers should have a sense of achievement, and their efforts should be recognised and “seen” by the teaching and research department and school management, especially when the results are not particularly remarkable in the early stage of reform. Teachers’ acceptance of blended teaching is considered the key factor for its success (Apandi & Raman, Citation2020). Only when teachers recognise its effect will they apply it (Zhao & Zhang, Citation2017).

7. Conclusion and implications

Based on grounded theory and using NVivo software, this study conducted a triple coding analysis of the factors affecting EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching and constructed a theoretical model. Based on this model, the researcher found that the three main categories of SPOC-based teaching intention, the school incentive mechanism, curriculum platform satisfaction, and social tradition affected teachers’ SPOC teaching behaviour. Among them, SPOC-based teaching intention was the pre-influencing factor, and the other two factors were situational influencing factors.

In comparison to Bai and Han’s (Citation2022) framework of teachers’ blended teaching, Antwi-Boampong’s (Citation2020) blended learning adoption model, and the influencing factors on faculty members’ participation found in previous research (Adekola et al., Citation2017; Garrote & Pettersson, Citation2016), the theoretical model of this study builds on the literature in the following three ways. First, SPOC-based teaching intention (SPOC-based teaching motivation and value perception) was associated with EFL teachers’ psychological motivation, which was the pre-influencing factor of teaching behaviour and directly affected EFL teachers’ SPOC teaching behaviour. Second, the school incentive mechanism (school support and school evaluation) and curriculum platform satisfaction (function satisfaction and English curriculum assurance) were associated with the situational influencing factors, which played a regulatory role in the impact of teachers’ intention to adopt SPOC teaching behaviour. Third, this study discussed the formation mechanism and subfactors of the three main categories, showing that SPOC-based teaching intention was composed of SPOC-based teaching motivation and value perception. Here, teaching motivation was the source of psychological intention, whereas value perception strengthened psychological intention. The school incentive mechanism was composed of two factors: school support was based on the organisational environment of SPOC teaching, and school evaluation was based on the management environment. Curriculum platform satisfaction included function satisfaction and English curriculum assurance, where the former was based on teaching conditions and the latter on teaching content. The social tradition was composed of the application environment and English teaching tradition, where the former was based on external factors and the latter on teachers’ own habits.

This research also offers enlightenment for those seeking to promote teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended learning in the post-COVID-19 era. Different stakeholders help EFL teachers carry blended learning out through certain measures in the Chinese higher vocational educational context. Students can act upon these effects through the construction and operation of SPOC-based blended teaching courses by EFL teachers to affect learning outcomes. However, previous research has mainly focused on the factors themselves, and did not systematically integrate the stakeholders involved; therefore, it was insufficient to explain how different stakeholders provide strategies to improve teachers’ implementation.

From a theoretical aspect, this research provides a new perspective for research on the factors influencing EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching, thereby enriching and developing the scope of qualitative research. The study’s findings can further optimise SPOC-based blended teaching policies and measures to benefit stakeholders in practice and provide theoretical guidance and reference for teachers to implement SPOC-based blended teaching in the post-COVID-19 period. Theoretically, the research model formulates a basic theory and constructs variables for subsequent research to model the factors influencing SPOC-based blended teaching behaviour.

8. Limitations and future research

In terms of limitations, blended teaching differs between higher vocational colleges and other educational institutions. As this research takes EFL teachers in higher vocational colleges as the research objects, the research scope must be expanded in future work to verify the applicability of these results. Furthermore, based on our findings, future researchers could quantitatively explore how the influencing factors interrelate and influence the implementation of SPOC-based blended teaching.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Liping Jiang

Liping Jiang is an associate professor and he is currently teaching in School of Foreign languages & International Business, Guangdong Mechanical & Electrical Polytechnic, Guangzhou city, China. He is a doctor candidate in UCSI University specialize in Education; his research interests include Business English research, Cognitive linguistics, Translation theory and translation. He has been responsible for lots of national-level and provincial-level research projects, including Humanities and social sciences research project of the Ministry of Education of 2021, China foreign language education research fund project in the year of 2013, “13th five year plan” project of philosophy and Social Sciences in Guangdong Province in China, “12th Five Year Plan” project of education and scientific research in Guangdong Province in China, etc, and published more than 50 academic papers, some of them indexed by Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index like the Journal of Shanghai Translation, Foreign Language Research and other journals.

References

- Abbas, T. (2016). Social factors affecting students’ acceptance of e-learning environments in developing and developed countries. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 7(2), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-11-2015-0042

- Adekola, J., Dale, V. H., & Gardiner, K. (2017). Development of an institutional framework to guide transitions into enhanced blended learning in higher education. Research in Learning Technology, 25. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v25.1973/rlt.v25.1973

- Ankit, A., Nachouki, M., & Abou Naaj, M. (2015). Blended learning at ajman University of Science and technology. In P. Ellerani (Ed.), Curriculum design and classroom management (pp. 975–998). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-8246-7.ch054

- Antwi-Boampong, A. (2020). Towards a faculty blended learning adoption model for higher education. Education and Information Technologies, 25(3), 1639–1662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10019-z

- Apandi, A. M., & Raman, A. (2020). Factors affecting successful implementation of blended learning at higher education. International journal of instruction. Technology, and Social Sciences (IJITSS), 1(1), 13–23.

- Apriska, E. (2020). Flipped classroom research trends in mathematics learning in Indonesia. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1613(1), 012030. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1613/1/012030

- Bai, H. (2021). An empirical study on the influencing factors of blended teaching quality of Public English in higher vocational colleges. Vocational Technology, 3, 65–70+75. https://doi.org/10.19552/j.cnki.issn1672-0601.2021.03.013

- Bai, X., & Han, X. (2019). Research on implementation strategies of leaders for blended learning in adult college. e-Education Research, 40(7), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2019.07.013

- Bai, X., & Han, X. (2020). University strategies of blended learning implementation with external support. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 41(3), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.14138/j.1001-4519.2020.03.014009

- Bai, X., & Han, X. (2022). Research on the influencing factors of teachers’ blended learning—qualitative research based on an adult university. Adult Education, 1, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-8794.2022.01.011

- Bhuasiri, W., Xaymoungkhoun, O., Zo, H., Rho, J. J., & Ciganek, A. P. (2012). Critical success factors for e-learning in developing countries: A comparative analysis between ICT experts and faculty. Computers & Education, 58(2), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.010

- Bokolo, A. J. (2021). Institutional factors for faculty members implementation of blended learning in higher education. Education + Training, 63(5), 701–719. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2020-0179

- Bolliger, D. U., & Wasilik, O. (2009). Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and learning in higher education. Distance Education, 30(1), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910902845949

- Chan, E. Y. M. (2019). Blended learning dilemma: Teacher education in the confucian heritage culture. Australian Journal of Teacher Education), 44(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n1.3

- Dang, Q. (2019). Research on SPOC online learning behavior and its influencing factors [Master’s thesis, Hangzhou Normal University]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201902&filename=1019921516.nh

- Dashtestani, R. (2014). Computer literacy of Iranian teachers of English as a foreign language: Challenges and obstacles. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 9(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/18334105.2014.11082022

- de los Arcos, B., Farrow, R., Pitt, R., Weller, M. & McAndrew, P. (2016). Adapting the curriculum: How K-12 teachers perceive the role of open educational resources. Journal of Online Learning Research, 2(1), 23–40. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/151664/

- Dintoe, S. S. (2019). Technology innovation diffusion at the University of Botswana: A comparative literature survey. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 15(1), 255–282.

- Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Addressing first- and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(4), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02299597

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1977). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Journal of Business Venturing, 44(5), 177–189.

- Fox, A. (2013). Viewpoint: From MOOCs to SPOCs. Communications of the ACM, 56(12), 38. https://libproxy.umflint.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/viewpoint-moocs-spocs/docview/2049933781/se-2?accountid=14584 https://doi.org/10.1145/2535918

- Garrote, R., & Pettersson, T. (2016). Lecturers’ attitudes about the use of learning management systems in engineering education: A Swedish case study. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 23(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1256

- Gedik, N., Kiraz, E., & Ozden, M. Y. (2013). Design of a blended learning environment: Considerations and implementation issues. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 29(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6

- General Office of the Ministry of Education. (2020). Temporary measures for the naming of colleges and universities, 2020. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A03/s7050/202008/t20200827_480729.html

- Glaser, B. G. (1992). Emergence vs. Forcing: Basis of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Transaction Publishers.

- Hew, K. F., & Brush, T. (2007). Integrating technology into K-12 teaching and learning: Current knowledge gaps and recommendations for future research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 55(3), 223–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-006-9022-5

- Hoffman, M. S. (2013) An examination of motivating factors on faculty participation in online higher education [Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University].

- Hu, R. (2008). The present situation and countermeasures of English teaching in vocational education. Shandong Foreign Language Teaching, 4, 110–112. https://doi.org/10.16482/j.sdwy37-1026.2008.04.021

- Jiang, D. (2021). An analysis of the influencing factors and coping strategies of English listening and speaking blended teaching in higher vocational colleges. English on Campus, (21), 48–49.

- Jin, X., & Shi, W. (2022). Reshaping the social status of vocational education–an interpretation of the general part of the newly revised vocational education Law of the People's Republic of China. Exploration of Higher Vocational Education, (3), 1–6.

- Jing, Y., Li, X., & Jiang, X. (2021). Analysis of factors that influence behavioral intention to use online learning and enlightenment in the post COVID-19 education. China Educational Technology, 6, 31–38.

- Joo, Y. J., So, H. J., & Kim, N. H. (2018). Examination of relationships among students’ self-determination, technology acceptance, satisfaction, and continuance intention to use K-MOOCs. Computers & Education, 122, 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.003

- Jung, H. J. (2015). Fostering an English teaching environment: Factors influencing English as a foreign language teachers’ adoption of mobile learning. Informatics in Education, 14(2), 219–241. https://doi.org/10.15388/infedu.2015.13

- Kabakçı-Yurdakul, I., Ursavaş, ÖF, & Becit-İşçitürk, G. (2014). An integrated approach for preservice teachers’ acceptance and use of technology: UTAUTPST scale. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 55(55), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2014.55.2

- Kasse, J. P., Musa, M., & Nansubuga, A. K. (2015). Facilitating condition for E-learning adoption—case of Ugandan universities. Journal of Communication and Computer, 12(5), 244–249. https://doi.org/10.17265/1548-7709/2015.05.004

- Khan, M. S. H., Bibi, S., & Hasan, M. (2016). Australian technical teachers’ experience of technology integration in teaching. Sage Open, 6(3), 215824401666360. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016663609

- Kihoza, P. D., Zlotnikova, İ., Bada, J. K. & Kalegele, K. (2016). An assessment of teachers’ abilities to support blended learning implementation in Tanzanian secondary schools. Contemporary Educational Technology, 7(1), 60–84. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/6163

- Kleijnen, M., Lievens, A., de Ruyter, K., & Wetzels, M. (2009). Knowledge creation through mobile social networks and its impact on intentions to use innovative mobile services. Journal of Service Research, 12(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670509333238

- Kuang, S., Zhang, H., Lu, J., & Zhou, G. (2019). Research on the model construction of the influencing factors of SPOC learning intention of college students based on PRATAM. Modern Distance Education, (5), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.13927/j.cnki.yuan.2019.0049.

- Lee, C. S., Osop, H., Goh, D. H.-L., & Kelni, G. (2017). Making sense of comments on YouTube educational videos: A self-directed learning perspective. Online Information Review, 41(5), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-09-2016-0274

- Li, B. (2022). Ready for online? Exploring EFL teachers’ ICT acceptance and ICT literacy during COVID-19 in mainland China. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 60(1), 196–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331211028934

- Li, L. (2014). Understanding language teachers’ practice with educational technology: A case from China. System, 46, 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.07.016

- Li, L., & Walsh, S. (2010). Technology uptake in Chinese EFL classes. Language Teaching Research, 15(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810383347

- Li, M. (2021). A study on teachers’ effective teaching behavior in College English blended teaching in higher vocational colleges. Overseas English, (12), 258–259.

- Li, X., Yan, W., & Li, Y. (2018). Research on the influence of blended teaching mode on teachers’ ability. Technology Wind, 33, 44. https://doi.org/10.19392/j.cnki.1671-7341.201833037

- Liu, M. (2018). Research on the influential factors of college teachers’ acceptance towards blended learning–from the perspective of diffusion of innovations theory. Modern Educational Technology, 2, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-8097.2018.02.008

- Ma, L., & Lee, C. (2019). Investigating the adoption of MOOCs: A technology–user–environment perspective. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35(1), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12314

- Ma, M., Chen, J., Zheng, P., & Wu, Y. (2020). Factors affecting EFL teachers’ affordance transfer of ICT resources in China. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1709210

- McLaren, J. H., & Kenny, L. P. (2016). Motivating change from lecture-tutorial modes to less traditional forms of teaching. Australian Universities’ Review, 16(6), 1893–1919. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1130765

- Mediani, H. S. (2017). An introduction to classical grounded theory. SOJ Nursing & Health Care, 3(3), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.15226/2471-6529/3/3/00135

- Ministry of Education, People’s Republic of China. (2007). College English curriculum requirements. Ministry of Education.

- Mustapa, M. A. S., & Ibrahim, M. (2015). Engaging vocational college students through blended learning: Improving class attendance and participation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 204, 127–135.

- Ngimwa, P., & Wilson, T. (2012). An empirical investigation of the emergent issues around OER adoption in sub-saharan Africa. Learning, Media and Technology, 37(4), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2012.685076

- Osman, N., & Hamzah, M. I. (2017). Student readiness in learning arabic language based on blended learning. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 6(5), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.5p.83

- Porter, W. W., & Graham, C. R. (2016). Institutional drivers and barriers to faculty adoption of blended learning in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(4), 748–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12269

- Rahman, N. A. (2014). Measuring teachers’ readiness in implementing virtual learning environment in primary classroom [Master’s thesis, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak]. https://ir.unimas.my/id/eprint/8704/1/Measuring%20Teachers%20Readiness%20in%20Implementing%20VLE%20(Virtual%20Learning%20Environment)%20In%20Primary%20Classroom%20(24pgs).pdf

- Salim, H., Lee, P. Y., Ghazali, S. S., Ching, S. M., Ali, H., Shamsuddin, N. H., & Dzulkarnain, D. H. A. (2018). Perceptions toward a pilot project on blended learning in Malaysian family medicine postgraduate training: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 206. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1315-y

- Shi, P. (2017). Analysis on influencing factors of blended teaching quality in higher vocational colleges. Course Education Research, (34), 35.

- Smith, J. A., & Sivo, S. A. (2012). Predicting continued use of online teacher professional development and the influence of social presence and sociability. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(6), 871–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01223.x

- Smits, A., & Voogt, J. (2017). Elements of satisfactory online asynchronous teacher behaviour in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33, 2. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2929

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 273–285). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Frontmatter.

- Taherdoost, H. (2018). A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manufacturing, 22, 960–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.03.137

- Teo, T. (2011). Factors influencing teachers’ intention to use technology: Model development and test. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2432–2440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.06.008

- Teo, T., Fan, X., & Du, J. (2015). Technology acceptance among pre-service teachers: Does gender matter? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.v0i0.1672

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410412

- Wang, H. (2009). Research on online consumer stickiness [Master’s thesis]. Shandong University.

- Wang, J., & Liu, W. (2022). Research on influencing factors of online course users’ sticky behavior. Distance Education in China, 3, 61–67+75. https://doi.org/10.13541/j.cnki.chinade.2022.03.006

- Wang, Y., & Ma, X. (2020). Research on blended teaching ability of college English teachers. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 08(12), 308–319. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.812025

- Wang, Y., Yun, F., Gui, Y., & Lu Xiaoli (2021). The development course, problems, challenges and optimization path of vocational and technical universities in China. Research on Vocational Education Development (04), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.19796/j.cnki.2096-6555.2021.04.005

- Win, N. L., & Wynn, S. D. (2015). Introducing blended learning practices in our classrooms. Journal of Institutional Research South East Asia, 13(2), 17–27.

- Xu, D. (2016). Exploring influential factors on implementing blended learning in higher education—a longitudinal case study of fuzhou university. China Educational Technology, 12, 141–145. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9860.2016.12.025

- Xu, Q, Liu, X, Zhang, H. (2021). Construction and empirical analysis of continuous learning behavior model of college students in online learning environment. Journal of Hubei Normal University (Natural Science), (04), 62–68.

- Xu, Y., Zheng, G., & Yu, H. (2020). An empirical study on the influencing factors of vocational: College teachers’ online teaching during the epidemic period. Vocational and Technical Education, (12), 17–22.

- Yahya, M., Nadzar, F., & Rahman, B. A. (2012). Examining user acceptance of E-syariah portal Among syariah users in Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 67, 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.338

- Yang, S. C., & Huang, Y.-F. (2008). A study of high school English teachers’ behavior, concerns and beliefs in integrating information technology into English instruction. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(3), 1085–1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.03.009

- Yeop, M. A., Yaakob, M. F. M., Wong, K. T., Don, Y., & Zain, F. M. (2019). Implementation of ICT policy (blended learning approach): Investigating factors of behavioural intention and use behaviour. International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 767–782. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.12149a

- Zhang, X., & Zhu, Z. (2016). Research on online teachers’ role identity and professional development—a case study of young teachers in China open university. China Youth Study, 5, 74–79+32. https://doi.org/10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2016.05.012

- Zhao, J., & Zhang, L. (2017). An empirical study on college teachers’ acceptance of blended teaching—from the perspective of the integration of DTPB and TTF. Modern Educational Technology, 27(10), 67–73.

- Zhao, L., Feng, J., & Gao, S. (2021). Research on influencing factors of college students’ continuous learning behavior in online education environment. Heilongjiang Higher Education Research, 39(2), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.19903/j.cnki.cn23-1074/g.2021.02.025

- Zhu, S., & Deng, X. (2015). Study on influence factors of older adults’ online health information seeking. Library and Information Service, 5, 60–67+93. https://doi.org/10.13266/j.issn.0252-3116.2015.05.010

- Zhu, T. (2017). Problems and training strategies of higher vocational teachers’ teaching ability in blended learning environment. Journal of Vocational Education, (32), 10–13.