Visual literacy is not a pass-time: it is a vital aspect of human behaviour. Making and understanding visual signs and images are part of human evolution and it co-defines what makes human beings unique. Learning to make and understand images is therefore both a biological and cultural challenge. The great variety in human imagery demonstrates its usefulness, pliability, diversity and complexity. Graphs, drawings, product design, fashion, sculpture, film, monuments, photography, television, schemes, architecture, traffic signs, stage design, tattoos, games, visual art and much more, are all forms of visual imagery that play a role in daily life. How can one learn to make successful images and how can one understand the meaning of images made by others? Much is learned in practice, through interacting with the visual world. But there is much more in visual imagery that eludes what we have learned in daily practice or what the first superficial look tells us.

In history, visual artists have been ‘assigned’ by society to act as specialists in discovering and exploiting the power of visual images, even to such an extent that their products were called ‘art’, to indicate that they have a special status and reflect a deeper understanding of the power of images. There are many things that can and should be learned about images. On the productive side, an image maker has to understand the ways an image can express meaning. The content of an image as it is recognized at first sight is just the first layer of understanding. The way this content is given visible form assigns to the image more emphasis and gives it extra layers of emotional meaning. On the receptive side, the observer has to be able to recognize this content, as well as appreciate deeper meanings. Both the maker and the observer have to share cultural knowledge about the content, stories and symbols used, as well as about the visual conventions and traditions of the style and genre of the work.

We can all make and understand images – it is a generic capacity that works the same way as speaking and understanding what other people say. But in language there is more to it than just words and grammar: the way things are said, the constructions used, and the tone and expressivity of the speaking voice substantially enrich communication. Thanks to these characteristics, language-based art forms like poetry, novels and theatre are created. In the visual domain, human beings have discovered the power of images and developed what we now call the visual arts in the broadest sense. Notions like ‘quality’ and ‘aesthetic experience’ reflect a deeper understanding and an added layer of visual sensitivity.

It is with good reason that visual education is part of our school systems. The visual disciplines as offered at school are not meant to prepare young people to become artists, but to help them to develop, make use of and understand ways of visual thinking, visual image making and visual communication. These are not extras in the curriculum, but essential contributions to personal and social development. The history of the visual art disciplines at schools reflects a growing insight in the role of imagery in human life. Education of visual competency started in the nineteenth century, to give young men a first training in draughtsmanship, in order to become good artisans and to prepare young women to make and restore textile objects. But at the same time, the role of art as a common good, available to all, became an issue. The first art history courses were developed in schools, and soon drawing lessons and handicraft activities became enriched with examples of work made by professional artists. Ever since that moment, in the western educational systems, learning to make visual images has evolved into special school subjects. The original pragmatic goals were gradually extended with educational, psychological, cultural and social goals. This development has not ended yet, as the role of art in society has not come to a halt but is still evolving.

The competency approach of ENViL

As part of this development, a fundamental discussion has started in Europe recently, about the way the goals of visual arts school subjects could be adapted to the latest developments and insights in art education and in education at large. In 2011, an initiative was taken to bring European researchers and art educators together. In 2013, the European Network for Visual Literacy (ENViL) was formed and soon it was decided to take up the challenge and reformulate the goals of visual arts in education. In 2014–2016, an EU-co-funded research project on competencies in the domain of visual literacy was carried out by members of ENViL. The first choice was to concentrate on the concept of ‘competency’ that has become central in more recent educational reforms, especially in Europe. Another inspiration of this project was the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, developed with support of the European Commission that served to define level descriptions of the mastery of (foreign) language. So next to formulating descriptions of the competencies that can be considered typical for art education, three level of mastery were formulated, too. Thus, the Common European Framework of Reference for Visual Literacy (CEFR-VL) was generated, more recently further elaborated and renamed as the Common European Framework of Reference for Visual Competency (CEFR-VC) (Schönau et al., Citation2020; Wagner & Schönau, Citation2016).

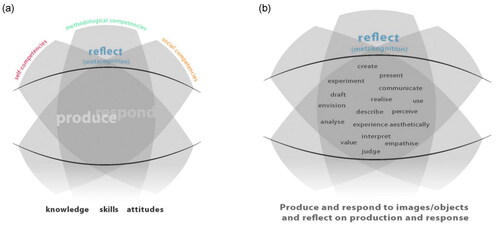

Figure 1. (a,b) The first European Framework of Visual Literacy. Source: http://envil.eu (Description with examples from educational practice in Wagner and Schönau (Citation2016)).

Based on the analysis of curricula in 21 countries (Kirchner & Haanstra, Citation2016), the first framework lists sixteen sub-competencies which can be related to both production and response. Some of these are more specific to the productive, others to the receptive domain and some overlap both. Competencies are activated in specific situations that call for visual communication, design and construction, creative expression or responding to a form of visual culture.

The new name for the framework, CEFR-VC, distances the domain from the concept of ‘being literate’ – an expression primarily indicating reading and writing skills (Schönau et al., Citation2020). Being visually competent means the combined use of knowledge, skills and attitudes manifested in specific situations that require the use of visual imagery. This name of the framework adheres to the original intention of the European Network of Visual Literacy to develop a framework that addresses competencies: the combined use of learnable knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are demonstrated in specific situations (Kárpáti & Schönau, Citation2019).

The original sixteen sub-competencies were related to more generic competencies that better reflect the dynamics of working and learning in this domain and make them more communicable for daily practice in educational contexts. They were grouped under the two major subdomains: producing and responding. Correlations were also clarified in terms of linear and non-linear sequences of sub-competencies: non-linear in producing, linear (with activities following each-other in a certain order) in responding (Schönau et al., Citation2020). A key feature of the revised framework is its interdisciplinary character. The cognitive, affective and psychomotor activities indicate a wide range of use of visual language far beyond the arts and thus indicate the increased role of art education in our (increasingly) Pictorial Age.

The competencies in the domain of producing are:

The competency to generate visual ideas: produce innovative ideas and/or indicate novel connections among social and visual realities or between datasets through images, often without the need of verbalization. Sketching or looking for insightful ways to present infographics, an emerging genre on the borderline of arts and science, are examples.

The competency to do visual research: artistic research, as well as scientific visualizations, such as dynamic representation of models and processes or the representation of networks may serve as examples.

The competency to make visual images: to realize visual ideas.

The competency to present one’s images: to enhance, emphasize, interpret or contextualize creations through sharing them with an audience.

The competency to evaluate one’s images and image-making processes. Self- and peer assessment that contributes to a deeper understanding of actions and results.

These sub-competencies are concrete enough to be explained to school-age children (on different levels of understanding, of course) but also flexible enough to invite specifications or interpretations related to individual projects.

The competencies in the domain or responding are:

The competency to look at images with an open mind: to observe, undisturbed by previous expectations, experiences or prejudices.

The competency to research images: to identify important aspects of form, function, style, utility, etc., that enable identification, interpretation, categorization of visual information, etc.

The competency to evaluate images: to assign spiritual, material, cultural, etc., value to an image and thus further its understanding and valuation.

The competency to report about images: to share ideas about images, assuming the role of impartial observer, colleague, user of an image system, critic, etc.

The overarching competency dimension of metacognition was retained, as it addresses reflection on producing and responding alike. This competency system may answer the increasing need for formulating a curriculum for ‘Visual Literacy in the K12 Classroom of the 21st century: from college preparation to finding one’s own voice’, as the title of Anderson et al. (Citation2021) indicates. This structure makes it possible to develop new rubrics that address certain situations of visual culture more directly and thus serve the purposes of self-reflection, assessment and evidence-based educational innovation.

ENViL and IVLA

When members of the ENViL first met with representatives of the International Visual Literacy Association (IVLA) in Louvain in October 2019, it became apparent that both organizations could learn a lot about one another, as the domain of visual literacy is not only very broad, but also developed and used by many professionals in all kinds of subdomains, from libraries to research laboratories, from publishing houses to art schools, from communication to education. We then decided to work on a Special Issue of the Journal of Visual Literacy concentrating on the educational aspects of visual literacy, we invited the ENViL membership to contribute to the special issue of this journal. ENViL’s project was oriented towards the concept of ‘competency’ in visual art education. Visual literacy is a much broader concept. So in this issue, the domain of visual literacy is addressed from the point of view of art education, focussing on the concept of ‘visual competency’.

In the first two contributions, the national developments in the visual literacy-related school subjects are discussed, with special regard to art education. In the first contribution of Gary Granville, a policy approach is taken, related to the changes in educational programmes for the visual art discipline in Ireland. This article represents an empirical application of the CEFR-VC Framework, that was used to design a national programme for art in Ireland and the development of an important national examination. The Framework was used as a ‘boundary object', that is plastic enough to be adapted to national needs and constraints, yet robust enough to maintain its identity. Optimal ways to develop and assess visual competencies were defined using the CEFR-VC as a catalyst of negotiations about the role of the arts in schooling.

In the second contribution about using the Framework on national educational level, a research-based approach is presented by Tarja Karlsson Häikiö from Sweden. After introducing the need for educational reforms in Sweden and their complexity, specific issues with regard to visual competency are discussed which are typical for the educational context. First, the position of the art teachers raises concerns. Those responsible for learning in this domain, should be given time, tools and appropriate educational space to do their work successfully. The second issue is the role of digital media. Art education has traditionally concentrated on the materials and techniques used by artists. The introduction of digital media, used in a productive or receptive context, is an innovation that is accepted only very gradually by art teachers. A third issue, also typical for education, is the role of assessment and the attention given to product and process, respectively. The gradual stretching of the borders of the visual domain, to include the wider concept of visual culture, is also a challenge to schools. Finally, the reformulation of educational goals in terms of visual competencies is discussed. This contribution underscores the need for clear definitions, when concepts like visual culture, visual literacy and visual competency are used in an educational context.

The next two contributions concentrate on the very first and the very last phase of visual education: generating ideas through sketching and assessing the final result.

In their contribution, Hermans and Schönau propose drawing as ‘active visual inquiry’, a method that activates sub-competencies of the revised Framework. In the productive domain, ‘the competency to generate visual ideas’ and ‘the competency to do visual research’ are basic constituents of drawing activities. This article also shows how the two domains of visual competency interrelate: drawing also involves two sub-competencies of the responsive domain: ‘the competency to perceive images with an open mind’, and ‘the competency to explore images’. The authors want drawing, once a basic method of art education, to regain its prominent position as a cognitive tool and expressive means. They illustrate this claim through examples that show how different genres of drawing – from sketching to graphic art – realize reflection-in-action and result in profound visual learning.

At the end of the educational trajectory, assessment takes a special position. In education, assessment is the most important tool to gather information about results to decide on entering the next class or phase in learning. Educational assessment techniques and instruments are very linguistic and quantifying, two characteristics that have a complicated relationship with the visual and qualitative nature of teaching and assessment in art education. Kárpáti and Paál have done new research on the use of visual rubrics, based on earlier research of the ENViL community (Groenendijk & Haanstra, Citation2016; Groenendijk et al., Citation2020; Haanstra & Groenendijk, Citation2016). First, they applied the use of visual rubrics to the more recent versions of visual competencies as presented by Schönau et al. (Citation2020). Then, they also introduced the same technique for use in art museums, and the assessment of more generic competencies. In combination with textual rubrics, in which the sub-goals or criteria and levels are described, visual rubrics turned out to be very helpful and understandable for students. It also made school students more aware that they can grow, that learning is a process and that absolute levels are not relevant. Judging results in the visual domain by visual criteria or rubrics thus achieves normalization of assessing visual processes and products in an educational context. The success of this approach is a promising demonstration that art educators and students alike can present their results in a way that is relevant and insightful within its own terms, and equally valid as more traditional ways of assessment as used in other school subjects.

The fifth contribution exemplifies the use of CEFR-VC for assessing the visual competency of young adults. Amna Qureshi, Melanie Sarantou and Satu Miettinen employed a participatory arts-based approach to elicit creative work that was assessed through phenomenological analysis and the Framework. Students were invited to make a series of photographs about the linear qualities of an object, then develop personal mandalas. The word mandala means ‘circle’ in Sanskrit, and in Hindu and Buddhist religious art. Its circular geometric designs symbolize the universe. Creation of this complex image, originally used as an aid for meditation, was introduced in psychoanalysis as a self-exploratory tool by Carl Jung (Citation1916–2017). In the experiment of Qureshi and co-authors, mandalas were similarly used for meaning making: the perception, interpretation and expression of feelings and thoughts. After completing the art tasks, future artist-educators reflected on the role of visual literacy in the creative process. The authors discuss sub-competencies of the CEFR-VC that were found relevant for the creative task and propose two new ones: improvization and visual inquiry. Both sub-competencies use visual language for developing new insights, and emphasize the cognitive gains of education through art.

In the final contribution, Litza Juhász discusses a recent book on visual literacy in visual art museum education, edited by Lode Vermeersch et al. (Citation2019), thus completing this overview of current issues in the educational domain of visual literacy.

Visual literacy – or competency, to use a term that involves an active and competent engagement with the visual domain – is approached from a variety of angles in this issue. The common characteristic feature of the articles is sharp focus: precise, research-based description of knowledge, skills and (sub)competencies of the territory where visual art education plays a key role. Whether at school or in a museum, house of culture or any other formal or informal learning environment, visual competencies need to be taught and learnt with precise aims and objectives in mind, to use the limited time and space assigned for this area of study by educational decision makers. Because, as the authors of this issue and other issues of JVL amply prove, visual literacy is not a pass-time: it is a vital aspect of human behaviour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, E., Avgerinou, M., Dimas, S., & Robinson, R. (2021). Visual literacy in the K12 classroom of the 21st century: From college preparation to finding one’s own voice. In M. Avgerinou, & P. Pelonis (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 blended and virtual learning through the i2flex classroom model (pp. 84–107). IGI Global Publisher.

- Groenendijk, T., & Haanstra, F. (2016). Erstellung eines auf dem Kompetenzmodell basierenden Instruments zur Leistungsbeurteilung. In E. Wagner & D. Schönau (Eds.), Common European framework of reference for visual literacy - prototype (pp. 292–299). Waxmann.

- Groenendijk, T., Haanstra, F., & Kárpáti, A. (2020). Self-assessment in art education through visual rubrics. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 39(1), 153–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12233

- Haanstra, F., & Groenendijk, T. (2016). Evaluation der auf dem Kompetenzmodell des CERF-VL basierenden Rubriken durch Lehrende und Schüler/Schülerinnen. In E. Wagner & D. Schönau (Eds.), Common European framework of reference for visual literacy- prototype (pp. 300–318). Waxmann.

- Jung, C. G. (1916–2017). Mandala symbolism. Princeton University Press.

- Kárpáti, A., & Schönau, D. (2019). The common European framework of reference: The bigger picture. International Journal of Education through Art, 15(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.15.1.3_2

- Kirchner, C., & Haanstra, F. (2016). − Expertenbefragung zu Lehrplänen in Europa – Methoden und Ergebnisse. In E. Wagner & D. Schönau (Eds.), Common European framework of reference for visual literacy – prototype (pp.191–202).Waxmann.

- Schönau, D., Kárpáti, A., Kirchner, C., & Letsiou, M. (2020). A new structural model of visual competencies in visual literacy. The revised Common European Framework of Reference for Visual Competency. The Literacy Pre-Literacy and Education Journal, 4(3), 57–72.

- Vermeersch, L., Wagner, E., & Wenrich, R. (Eds.). (2019). Guiding the eye: Visual literacy in art museums. Waxmann.

- Wagner, E. & Schönau, D. (Eds.). (2016). Common European framework of reference for visual literacy – prototype. Waxmann.