ABSTRACT

Street art has flourished around the world, gaining international recognition and commercial success. Consequently, controversies over their misuse have escalated, and artists have begun to pursue legal protection of their intellectual property (IP) rights. But asserting these rights is still quite difficult, creating a state of uncertainty and risk to both artists and interested parties. In this article, we introduce Street-Art-NFT-System (SA-NFT), a dynamic street art ledger that enables artists to assert their IP rights and communicate with other interested parties, while maintaining their anonymity. Additionally, SA-NFT can create a new documentation method that will open new avenues for studying a city's ever-changing urban facades.

Introduction

Consider the following scenarios: (1) A young street artist strolls down a street in search of a location for her new artwork. Looking up, she is astonished to discover one of her well-executed pieces decorating a local bank's commercial advertisement. When the artist sues the bank for copyright infringement, she is dismayed to discover that the court accepts the bank's claim that it was unsuccessful in identifying and contacting the artist to obtain permission for its use; (2) A world-renowned artist is ecstatic to see that her mural “Groundhog for a Day” has generated intense interest on the Internet. Little does she know that her happiness will be short-lived. The following morning a representative from a private auction-house will arrive with a hacksaw and remove the artwork from the street to be auctioned, leaving a scar on the wall that would be visible for years to come; and (3) A location scout wanders the streets of Brooklyn in search of an alley in which to film a new Dwayne Johnson movie. When he finally finds the ideal location, he is delighted to come across a beautiful work of unsanctioned street art on one of the alley's façades. Unfortunately, the production company is unsuccessful in locating the artist and obtaining permission to use the work in the film. Concerned about copyright infringement, the company hires a new artist to paint over the existing work.

These scenarios represent real-life tensions that affect urban landscapes, challenge the ability of artists in asserting their intellectual property (IP) rights, and call into question the willingness of certain street artists to create work in public spaces. This article presents strategies for addressing these situations, while protecting IP rights.

In recent years, the assertion of intellectual property (IP) rights has been constantly moving from the physical into the quasi-digital realm. This is illustrated, for example, in the fields of photography and literature, where images and books are no longer solely produced as physical objects but rather as accumulations of data. This can also be seen in the growing field of online trading and auctioning of physical and digital assets.

Over time, the boundary between the physical and digital worlds has blurred significantly, affecting both worlds. It has influenced how we act, interact, and mobilize; it has affected the legal system, opening it up to new dilemmas and conflicts; and it has incorporated human and social behavior into technological concerns. The merging of the two realms has its challenges. One of which is that the logic that guides the legal or social system and the rationale guiding the technology domain do not always align. This is especially evident when considering concepts like “conflict resolution,” which can either be viewed as a mathematical or as a social term. Another challenge is that the relationship between social and technological factors affects both regulation and implementation. How we regulate technology is influenced by both the technologies themselves and how people use them, the implementation of technologies is then influenced by both technological innovation and regulation.

This conceptual article introduces the use of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) and blockchain technology as means to resolve the above mentioned tensions, navigating the meetings between frontier technologies and street art. The proposed system will facilitate the development of a dynamic street art ledger that will help manage the urban sphere, provide artists with the ability to assert IP rights over their artworks, and pave the way for better communication between interested parties and artists while maintaining the anonymity of the artist. Additionally, the use of a blockchain ledger will create a new documentation method that will open up new avenues to study the ever-changing surfaces of cities and their artworks.

Works of street art are transient and dynamic elements that vary in size, style, and legal status. They are sometimes created with owner or municipality consent. At other times, they are created without consent, in a more “underground” fashion. The term “street art” is used loosely throughout this article, focusing on artworks created directly on building facades, such as murals, aerosol-based works, or stencils (see, for example, ). We purposely do not differentiate between works of street art, street art-inspired murals, and graffiti works that hold artistic merit.Footnote1 There are several reasons for this: (1) The boundary between these styles has increasingly become blurred in recent decades and is frequently context-dependent, meaning that these definitions may vary from city to city; (2) Unsanctioned artworks have been undergoing legalization processes in recent years, whether prompted by municipalities or indirectly through artists’ demands to be protected under copyright and moral rights acts (e.g., Bonadio, Citation2019a; Iljadica, Citation2016). Consequently, even unauthorized artworks may enjoy some degree of statutory protection; and (3) Lastly, as shown in this article, even artists who create sanctioned murals may face the same kinds of challenges while asserting their IP rights as those working illegally.

This article does not aim to provide an in-depth study of the legal implications of IP rights legislation for street art (see, for example, Bonadio, Citation2018a, Citation2019a; Cloon, Citation2016; Crinnion, Citation2017; Kelly, Citation1993; Iljadica, Citation2016; Kaur, Citation2019; Lerman, Citation2013; Rychlicki, Citation2008; Salib, Citation2015). Our goal is to examine, both conceptually and exploratorily, how street art can be protected using new technology. We further investigate how innovative tech platforms might increase the viability of these artworks as well as protect the rights of their creators.

We begin by outlining the context: namely, the commodification of public space and the challenges faced by street artists seeking to defend their IP rights. We then introduce the Street-Art NFT System (SA-NFT), discussing its technical aspects and demonstrating its capacity to enhance an artist's ability to assert those rights. Finally, we illustrate how SA-NFT can support new documentation methods.

Street Art-Related Rights

Street art has become a significant visual genre in urban environments, reflecting and influencing the social, political, cultural, and aesthetic values of a city (e.g., Halsey and Pederick, Citation2010; Mendelson-Shwartz and Mualam, Citation2020; Riggle, Citation2010). Over the years, street art has become increasingly accepted as a legitimate art form, as evidenced by international recognition and commercial success (e.g., Droney, Citation2010; Evans, Citation2015; Young, Citation2014). This is exemplified by the growing number of commissioned street artworks created in public spaces, museum and gallery exhibitions dedicated to street art, street art festivals, and the co-optation of street art as a means of attracting tourism and branding cities (e.g., Ashley, Citation2015, Citation2021; Ferrel, Citation2016; Grodach, Citation2011). The popularity of street art is also indicated by the careers of (in)famous artists like Banksy, Blu, Shepard Fairey, and JR, who have become world-wide superstars and whose works are recognized well beyond the street art community.

Although many works of street art are created as acts of protest against political regimes and existing socioeconomic conditions, they have been popularized and embraced by third parties. In many instances, they have also been commodified, even when the artwork's intended message attacks commercialization (e.g., Austin, Citation2010; McAuliffe, Citation2013). Street artworks now appear in mainstream media, commercial advertisements, TV shows, and movies; they are re-produced as home decor, on apparel, and on souvenirs. Some are even sold to private collectors through auction houses and art experts (e.g., Bonadio, Citation2018a; Kramer, Citation2010).

As the popularity of street art increases, it has been accompanied by a steady rise in conflicts over their misuse (Bonadio, Citation2019a). For example, individuals and corporations have integrated street art into advertising campaigns and products without the artist’s consent. Likewise, unsanctioned artworks have been removed from public facades to be auctioned off in private art sales, practically treating them as private goods (Hansen, Citation2018; Lerman, Citation2013). This raises the question of legal protection over the rights of street artists (Cloon, Citation2016).

In general, artists do not own the (physical) artworks they have created on outdoor facades (Mendelson-Shwartz and Mualam, Citation2021). However, they do possess intangible (intellectual property) rights.Footnote2 Furthermore, even after the artwork itself is covered or taken down, the artists still hold their IP rights. While street artworks were regarded in the past as “negative spaces” that are not regulated by IP law, this perception has changed (Cloon, Citation2016). In recent years, more street artists have begun to take legal action to protect their intellectual property, including their moral rights. Even the artist Banksy—known for maintaining that “Copyright is for losers” (Banksy, Citation2005:3)—has taken legal action over trademark infringements of his works (Bonadio, Citation2019b).

IP rights held by street artists protect the interests and reputation of the artist and comprise a range of benefits. These IP rights are divided into three categories that allow for the protection of different aspects of the artwork: moral rights, copyrights, and trademark. Moral rights allow artists to receive credit for their work. They also give the artist the right to claim or deny authorship of an artwork and the right to prevent intentional alteration, modifications, mutilation, or destruction of her work (e.g., Kelly, Citation1993; Marks, Citation2015). Moral rights seek a balance between an artist’s rights and property rights.Footnote3 For example, under the United States Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), while property owners may not alter or mutilate artworks on their walls without the consent of their artists, they may destroy the artworks after notifying the artist (or making a good faith effort to do so), allowing the artist to remove the mural or document it.

To date, the most prominent case involving moral right infringement is the case of 5Pointz, Queens, New York City, in which a group of street artists were awarded US$6.75 million for the destruction of their works without prior warning and the violation of their moral rights (Kinsella, Citation2020). During the 5Pointz ruling, the New York court extended the concept of “sanctioned artworks” to include works created in locations where property owners only gave their implicit consent, such as in Tolerant Zones, Free Walls or Halls of Fame (Fischer, Citation2015; Marks, Citation2015). Therefore, if works of street art follow VARA requirements, they may be granted moral rights protection (Lerman, Citation2013; Schwender, Citation2016).

In addition to moral rights, copyright laws provide further protection to artists:Footnote4 they secure the economic benefits of artists, enabling them to benefit from any commercial use of their works. These laws also enable artists to demand fair use and to refuse the commercialization of their art (Bonadio Citation2018a; Schwender, Citation2016).

Although the majority of academic literature regarding the IP rights of publicly located works of art focuses on the United States, there are some exceptions. One notable exception is Enrico Bonadio's inspirational handbook of copyright in street art and graffiti (Citation2019a), which provides an excellent overview and comparative analysis of copyright laws worldwide. While not all countries have incorporated moral rights into their laws, many have done so. Furthermore, Bonadio's book demonstrates that in many countries sanctioned street art is protected by copyright laws, which SA-NFT can help secure.

To our knowledge, there has not been a definitive court ruling to-date on whether unauthorized street art should be protected by copyrights. On the one hand, using the doctrine of “unclean hands,” which states that a person should not benefit from their crime, some would argue that granting copyright protection for an unsanctioned artwork would encourage artists to continue violating the law, by painting without permission in public spaces. On the other hand, copyrights, like other IP rights, are designed to protect the intangible qualities of artworks that are independent of their physical manifestations (Lerman, Citation2013). Thus, some argue that similar to IP rights that are separated from physical ownership, the illegality of works of street art should not affect its IP rights (Cloon, Citation2016; Lerman, Citation2013). To demonstrate this, Enrico Bonadio (Citation2018b) asks: “I steal a pen which I then use to draw a wonderful piece of art, why should I be denied copyright protection and tolerate that someone else copies and takes economic advantage of my work?” (Bonadio, Citation2018b:78). It might be argued that denying copyright protection to unsanctioned street art might encourage free-riders to use the work of others for self-gain (Cloon, Citation2016). The latter interpretation of the law is also in line with today's reality, where street artists can achieve international recognition and still be prosecuted for violating property or criminal law. It is also consistent with numerous copyright infringement cases that have been settled out of court,Footnote5 which imply that street artists’ claims of infringement may have legal standing. Furthermore, to our knowledge, in cases that involve copyright infringement of street artworks, courts have not denied copyright protection due to the aspect of illegality. In so doing, they have implicitly acknowledged the copyrightability of unsanctioned street art (Cloon, Citation2016).

Artists’ rights in public spaces may also be protected through trademark laws. These protect recognizable marks, signs, logos, designs, or expressions that can exclusively identify the source of a product or a service.Footnote6 Trademark laws can, therefore, be used to protect an artist’s pseudonym, signature, or artistic style (Crinnion, Citation2017). To stop unauthorized exploitation of their works, artists can claim trademark infringement.

To claim trademark infringement, the artist must first show that the work is distinctive and has developed a secondary meaning; thus people associate the mark with the artist. For example, street art enthusiasts would connect the wheat paste of “Andre the Giant” to Shepard Fairey, the tile mosaic figures of spaceships to the artist Invader, and the stencils of rats holding paint rollers to Banksy. Notably, trademark infringement may be hard to establish when the artist is not well known. That being said, there are street artists who have parallel businesses (e.g., fashion or graphic designers, tattoo artists) in which they may use brands inspired by their artworks. It would be simpler to assert their IP rights through trademark law, as they provide products and services under such brands.

Next, artists will need to prove they have suffered economic loss as a result of the commercial use. Alternatively, they can claim that the use of their artwork has produced a “false designation of origin,” meaning that it generated confusion or misunderstanding as to its creator or its affiliation (Crinnion Citation2017; Kaur, Citation2019). For example, street artists may argue that using their work on a designer handbag would confuse people into believing they partnered with the brand or received their sponsorship. Furthermore, artists can argue that if their art is misused, it might create an illusion that they “sold out,” thereby damaging their “street credibility” and eventually destroying their livelihoods (Cloon, Citation2016; Crinnion, Citation2017)

Lastly, to prove economic loss due to misuse of their art, artists would be asked to prove that the work in question has been “used in commerce.” This requirement may prove difficult for many street artists who create their work freely in public spaces. Both Kaur (Citation2019) and Crinnion (Citation2017) believe that as courts have broadened their interpretation of the term “used in commerce,” it is only a matter of time until they decide to include street art as a practice that affects commercial activity. Despite this optimistic view, it has yet to be adopted by court systems.

This was notably demonstrated in the continuous legal squabble between the UK-based card manufacturer “Full Colour Black Limited” and Banksy’s representatives, “Pest Control.” Throughout the years, Banksy, through his representatives “Pest Control,” has registered some of his known stencil works as trademarks (e.g., flower bomber, Girl with Balloon). During a preliminary proceeding in 2018, the Milan court granted Banksy trademark protection (Bonadio, Citation2019b). However, the judge noted that Banksy only made limited use of his/her registered brands, potentially weakening future lawsuits (Bonadio, Citation2019b). As a result, Banksy opened a pop-up store and began selling merchandise. This did not prevent the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) from invalidating two of Banksy’s trademarks in 2020 and 2022 on the grounds that they were registered in bad faith as they were not created “to create or maintain a share of the market by commercializing goods” (Sharma and Chauhan, Citation2018).

Although this court decision has cast doubt on the efficacy of trademarks as a means of protecting unsanctioned artworks, the fact that the legality of the artwork was not cited as a reason for invalidating its trademark opens a door for future interpretations. In this regard, Crinnion (Citation2017) argued that since artists who create street art provide free artworks that beautify cities, they should be treated as engaging in charitable activities and thus enjoy trademark protection like other charity and non-profit organization. To our knowledge, this argument has not been tried in court yet.

Challenges in Asserting IP Rights in Street Art and Graffiti

Although street artists may hold IP rights over their artworks and can enjoy legal protection, at least to a certain extent, asserting these rights is quite difficult. First, most street art is not listed in any public registry that grants it special recognition, nor is it tied to contractual arrangements. Second, most street artists create their work under a pseudonym, making it difficult to identify them and determine authorship of the work. Third, even if the artists are known, it is not always easy to track them down and contact them. Lastly, unsanctioned artworks are usually created illegally, and thus when artists wish to enjoy the law’s protection, they need to come forward, therefore risking self-incrimination.

When an individual or a company wishes to use a work of street art, and the artist cannot be reached, the artwork may be classified as an “artwork of unknown authorship” (or “orphan work”). This enables the interested party to use it without IP infringement (Bonadio, Citation2018a). But this status could change over time as the artist may decide to reveal her identity, for example after the statute of limitation regarding the illicit creation of the artwork has expired, and reclaim her artwork (Bonadio, Citation2018a). To do so, the artist must prove that she indeed created the piece. This is typically achieved by presenting sketches, past works, or other supporting evidence. This can be quite difficult when artists cannot provide such proof.

If the artist successfully reclaims an artwork, she can prohibit further use or demand royalties. Furthermore, if the artist can prove that there was a simple way to contact her (e.g., website, social media) that was not used by the interested party, she can sue for IP infringement, arguing that her artwork had never been “orphaned” (Bonadio, Citation2019a). This uncertainty could be problematic for both artists and interested parties. It can prevent artists from profiting from their work or from exercising their right to veto its commercialization. Additionally, it could expose the interested party to potential lawsuits, affecting their willingness to use or even commission street art.

This uncertainty does not relate exclusively to unsanctioned street art, but may also apply to murals. Many cities lack any registry system for sanctioned artwork, and as time passes, properly identifying the creator of a sanctioned artwork becomes as difficult as tracking “insurgent” artists. Furthermore, as some courts have expanded the scope of the term “sanctioned” artworks to include street art created in tolerant zones, new owners of property with preexisting artworks may need to contact the artist to assess their expectations and negotiate the art’s future (Fischer, Citation2015; Marks, Citation2015).

To assert their IP rights, street artists typically employ the services of a trusted third-party, such as galleries or art agencies (e.g., Banksy’s Pest Control Office Limited). But this solution is mainly accessible only to high-profile artists. Furthermore, to maintain the artists’ anonymity, the trademark rights need to be registered under the third-party and not the artists themselves (Bonadio, Citation2020). However, not all rights can be transferred to a third party; certain IP rights, such as moral rights, can only belong to the artist. Therefore, to properly protect their IP rights, artists will need to disclose their identity even when employing a third-party representative.

A New Model for Addressing Existing Challenges: SA-NFT-based System

Thus far, a review of the literature suggests that artists, working in the public realm face multiple challenges in asserting their IP rights. Some of these challenges are tied to the nature of the artwork (for example, subversive and anonymous murals, or older murals of uncertain authorship). Some of these challenges result from the artists’ need for anonymity, while other challenges concern the legal system and its protection (or lack thereof) of artists’ IP rights. Additional challenges are associated with the public nature of the artwork itself: specifically, its accessibility, its visibility, and its vulnerability to extensive and uncontrolled use by third parties.

Moreover, any tool that aims to assist street artists in enforcing their IP rights must consider additional threats surrounding the creation of graffiti and street art. The graffiti and street art ecosystem is a distrustful and, to some degree, paranoid environment. Due to financial incentives, personal disputes, or other circumstances, users may be motivated to expose street artists’ identities, claim authorship of others’ work, or sabotage data. Additionally, since many artists operate illegally, artists and their artworks may be targeted by enforcement agencies. Consequently, actors in the street art community tend to guard their identities and data jealously and any registry system must take that fact into account.

In the subsequent sections we inquire as to how technological innovations might help street artists protect and assert their IP rights in the face of these challenges. We introduce the SA-NFT, which provides artists a platform to actively control their artworks’ future, whether they seek to profit from their art or prevent its commercialization.

SA-NFT: Brief Overview and Justification for Employing an NFT Based System

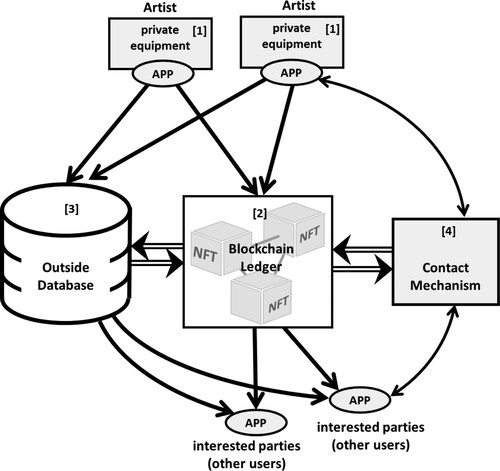

As illustrated in (the following numbers in brackets refer to those in the Figure), artists will upload their artwork and create a secure anonymous public profile using a dedicated application installed on their private mobile devices [1]. The application will register, authenticate, and timestamp the artwork. The artwork’s evidence will be added to the public blockchain ledger [2] and its image will be stored in a separate external database [3], containing bidirectional links. Both ledger and database will be visible to all. Any user will be able to browse the database, or to photograph existing artworks to obtain additional information (similar to the use of “Shazam” in the music industry). Additionally, artists will be able to include a QR code (or any other linking mechanism) with their artworks to assist viewers in locating them within the system. Users will be able to contact artists via a blockchain-secured contact mechanism that links the artist's public profile to an anonymous message box.

A non-fungible token (NFT) is a unit of data (type of record) that functions as a unique digital identifier; it is not replaceable, duplicable, or divisible. Each NFT is associated with a particular digital or physical asset and a particular owner. Thus, NFTs provides SA-NFT a proof of ownership between artist and artwork.

NFTs are stored as blocks in a blockchain infrastructure. A blockchain is a type of a distributed ledger technology (DLT) that allows for the development of a decentralized database network without a centralized authority. Like threaded beads, data is sequentially added to the ledger (as blocks), in a linear and chronological order, chaining itself to previous blocks, using hash functions. Though blockchain technology is perhaps best known as the foundation of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, the technology has been put to diverse use including: land and property registry (Ansah et al., Citation2023; Bennett et al., Citation2019; Chandra and Rangaraju, Citation2017; Eder, Citation2019; Thakur, Citation2020; Yapicioglu and Leshinsky, Citation2020); bill management in the shipping industry (Liu, Citation2000); safeguarding cultural heritage (Gipp et al., Citation2017; Huang and Dai, Citation2019); digital copyright protection (Savelyev, Citation2018; Vishwa and Hussain, Citation2018); and autonomous vehicle security (Davi et al., Citation2019; Ferdous et al., Citation2019; Sharma et al., Citation2018).

By using blockchain technology, SA-NFT can provide a trusted and immutable ledger that is immune to alterations and transparent to all users. Furthermore, blockchain technology enables the maintenance of a system in which the data are distributed, and not owned or controlled by any single entity. In contrast to some blockchain-based currency systems, SA-NTF blockchain lacks a mining process, hence lacks the negative environmental impacts that are associated with mining.

To establish trust between users, the system is transparent and can be viewed, verified, and monitored by all. Blocks in the ledger are linked using a secure hash function, which is an easy-to-verify but it is computationally infeasible to forge a set of bits. This allows users to backtrack the chain and verify that it was not tampered with, from end to start.

SA-NFT uses public key cryptography (Rivest et al., Citation1978; Blumenthal, Citation2007) to underpin the relationship between artists and the blockchain while maintaining anonymity. A private key is a secret used to cryptographically sign a claim. The public key is known to all and is used by the outside world to cryptographically authenticate the signature of a claim. While it is rather easy to authenticate a signature of a claim, it is computationally infeasible to forge a signature without knowing the private key. Today, public key cryptography is widely employed to verify digital identities (e.g., electronic identity cards, web server security, and digital signatures). Using the public key, it is easy to verify that a signature was created by a specific artist, but it is virtually impossible to expose the artist's private key and identity. Using a proof-of-possession (POP) test (Asokan et al., Citation2003), artists can easily and publicly confirm they hold the private key and therefore are the real owner of the NFT (thus are the artists), without revealing its content and disclosing its secret.

To summarize, combining NFT, Blockchain, and public key cryptography can allow artists to anonymously register their artworks, all the while holding indisputable proof of their authorship. As a result, other system users can easily verify that an artwork was indeed registered by its original artist, but they cannot reveal the artist’s identity; only the artist herself can do that, if she so chooses. Additionally, SA-NFT will pave way for interested parties to contact artists without exposing the artist's identity, providing indisputable proof that the artist has or has not granted permission for their artwork’s use, and thereby eliminating future confusion. Lastly, SA-NFT has the ability to produces a dynamic street art ledger that can serve as a documentation tool.

Technical Aspects of the System

In this section we conduct an in-depth examination of the system’s technical aspects, discussing computer science concepts and using some technical jargon in order to flag important technical issues inherent to the system. Following, in the discussion section, we address SA-NFT’s ability to function as a dynamic open-data street art archive, issues of user anonymity and incrimination, and implementation concerns.

Registration of Artwork into the System

SA-NFT is designed to support two types of users: artists who create and then upload their original artworks,Footnote7 and interested parties (other users) who browse existing artworks and may wish to contact artists.

SA-NFT relies on private equipment and public infrastructure. Private equipment, for our purposes, is any individual mobile device owned and trusted by the artist [1] (see ). There may be many private mobile devices, but each of them can only belong to a single artist. Public infrastructure is any element of the system that is outside the domain of the private equipment. This includes: the blockchain ledger [2], an external database [3], and a contact mechanism [4].

Artists will use their private equipment to document artworks and to authenticate their originality (i.e., that it is a new photo taken by the artist at a specific location and within a specific timeframe). Given that certain individuals may have an incentive to falsely register artworks as their own, the system must take precautions to enable users to verify data registered into the system. Thus, although the private equipment (of the artist) is trusted by the system, the artist herself is not. Data generated by private equipment, e.g., a captured photo and its original metadata (location, time, etc.), must be digitally signed and can be independently verified.

Because the metadata generated is essential to the forming of indisputable evidence, we require the private equipment to use secure services such as trusted time (Poisner, Citation2002) and a trusted GPS location (Psiaki and Humphreys, Citation2016) that cannot be forged by an attacker. Furthermore, the digital signature must be solely based on the private equipment's hardware and a unique private key, without any software intervention (Gebotys, Citation2009).Footnote8 Nowadays many commodity products such as computers and mobile phones embed a device-specific private key that is never exposed externally and is available to hardware-based signature mechanisms. Any such signature is accompanied by a manufacturer’s certificate signed by a certificate authority (CA), which serves as the device signature's root-of-trust. As a result, anyone can verify the authenticity of the data and metadata uploaded by the device. As stated later in the discussion section, we recommend the use of a group certificate (Lee et al., Citation2009) to enhance the artist’s anonymity.

Authenticating the data itself does not ensure that the person registering the artwork has indeed created it, i.e., not a bystander or someone with malicious intentions. To ensure this, artists are asked to perform a multi-stage process using a designated application installed on their private equipment. When creating a mural or any other time-consuming artwork,Footnote9 the artist is instructed to first take a photo of the intended wall via the application. As the artwork progresses, the artist is asked to take one or more photos showing the process, and then of the complete artwork. As mentioned above, all photos must include trusted time and location, and a valid hardware-based signature. The demand for multiple-staging photos is intended to distinguish between artists and imposters. First, artists can premeditate their artwork before the creation process. Second, they are likely the only ones who can document the creative process and their presence onsite should discourage or obstruct any attempts of false ownership claims. This suggested method was devised after consulting several street artists.

SA-NFT is intended to serve only new artworks (as opposed to existing works). The system is agnostic to the legality of artworks and can be used to upload both sanctioned and unsanctioned artworks. Although SA-NFT can benefit both artists who create legal or illegal artworks, unsanctioned works are still more susceptible to IP abuse. Thus, in the article we will tend to focus on unsanctioned artworks.

To ensure that only newly-created artworks are uploaded to the system, the artist will be asked to upload her work to the system in a reasonable time frame after its creation. Before uploading the photos to the system, the designated application signs the package of photos with a private key belonging to the artist’s profile. This set of public and private keys is generated by the user’s application, and its purpose is to connect the uploaded package with the virtual identity of the user. As such, there is no need for a certificate because the user is trusted to provide the package. Later, the same private key will be used to sign the artist's communications, proving that the author of both the package and the communications is one and the same.

Due to the limitations inherent in blockchain technology, the ledger can only consist of small data blocks. As a result, the data are uploaded and registered in two linked data structures: the blockchain ledger and an external database. The blockchain ledger contains the artwork’s metadata (timestamp, geo-data, etc.), a hash of the artwork's photos, the artist ID in the system, the artwork’s digital signature, and a link to the external database. The external database consists of images of the artworks. These two data structures are only trusted to collect information, i.e., to serve as public storage. While the blockchain is distributed among the system's users, the external database is not (e.g., stored in the cloud). Any registration in the blockchain is bi-directionally linked to the external database (Gaetani et al., Citation2017).

Due to the nature of street art and IP rights, although artworks may override one another in the public realm (i.e., by being covered over by a new artwork), their artists still keep their IP rights and their evidence is maintained in the ledger. Meaning, that unlike the cryptocurrency usage of blockchains (e.g., Bitcoin), SA-NFT’s blockchain ledger does not contain transactions but rather additive information. Therefore, the system can accept simultaneous additions to the ledger, serializing them according to the artworks’ timestamps. As a result, risks associated with transactional blockchains (e.g., 51 percent attack) are irrelevant for this blockchain ledger.

User Interaction

Users (interested parties) wishing to use SA-NFT to obtain information about existing street art can either browse the external database, access it via QR code (or any similar linking mechanism) placed by the artist on site, or photograph the piece and have the system's AI mechanism search for the artwork in its database. This can be done using the same application used by the artists.

The artworks registered into the system have not yet been validated. Before users contact artists, they will wish to verify the authenticity of a registered artwork. Using the CA signed public key, the user can verify that all of the artwork’s pictures were taken by the same device at the same location within a reasonable time frame. Then, the user should verify that the pictures match the expected creation process of the artwork. Second, using the public key generated by the artist’s application, the user can verify the authenticity of the signature of the package of pictures. Later on, the artist will be asked to provide a proof of possession (POP) for the matching private key, thus verifying authorship.

The connection between users and artists relies on a communication platform with the following properties. The artist must be able to maintain anonymity when communicating through the system. Every message sent through the system must be indisputably recorded but not publicly exposed, so that both parties can provide a digitally signed record of communication. The communication itself will be encrypted and only the artist and the user can decrypt it. Lastly, the system must allow both parties to electronically sign a contract regarding, as requested, the interested party’s use of the artwork.

Discussion

We will focus on three main issues in the discussion section: increasing anonymity and reducing incrimination, the use of SA-NFT as a documentation method, and issues regarding implementation.

Anonymity and Incrimination

A public blockchain ledger is a long lasting and transparent database that is open to all viewers. Thus, through this system, the artist's privacy is more pseudonymous than anonymous. In other words, artists can upload artworks and communicate in the system using a pseudonym (linked by their private key). If the pseudonym were ever to be linked to their true identity, artists would lose their anonymity and all their past artworks uploaded under that pseudonym would be immediately linked to them.

The following proposed mechanisms could aid in maintaining anonymity and preventing artists incrimination: (1) Creating multiple profiles: We suggest artists who work outside of the legal realm to consider registering their artworks using various profiles (artist private-public keys), thus reducing the risk of their works being linked together; (2) Using group certificates for hardware-based signatures: Pictures taken by the artist’s private equipment are signed using a hardware-based signature, containing a certificate that was determined upon their device’s manufacture. This certificate remains the same for any given public key, and therefore may be used to track users. We recommend the use of a group certificate (Lee et al., Citation2009) that allows many private “equipments” (i.e., individual mobile devices) to share the same certificate, reducing the ability to single out specific artists via their signature; and (3) Delaying the publication of an artwork—When artworks are registered in SA-NFT, the data in the system exposes their creation time and location. This may benefit some artists who can quickly announce the creation of their new artwork, but it can also expose artworks to surveillance by authorities and cleaning crews, possibly shortening their lifespan. Having said that, in today's digital age in which instant photo uploads to social networks like Instagram or Twitter are commonplace, and unwanted graffiti are easily reported via city-based apps, we believe that SA-NFT will have little impact on street art surveillance. To slow down this process, SA-NFT should allow artists the ability to delay the publication of their artwork for a specified period after its creation. Upon an artwork’s completion, the artist would have the option to upload an encrypted version of their data to the system. Later, the artist can add a new block to the chain containing the decryption code that opens the data to all, thus publicizing the new artwork. SA-NFT should not limit the time in which the artist can upload the decryption code.

Using SA-NFT as a Documentation Method

We believe that the advantages provided by the system to street artists and writers will serve as an incentive for them to make widespread use of the system. As a result, they will act as active documenters of creative cityscapes. Thus, SA-NFT will de facto serve as a dynamic and authenticated archive of a city's ever-changing surfaces.

With today’s growing connection between the physical and the digital, SA-NFT has the potential to open up new avenues for documentation and digital preservation, enable new tools for managing public spaces and activities, and assist historians, art enthusiasts and researchers in studying art in public spaces. Additionally, SA-NFT would allow users to be more engaged with their urban environment, affecting the way they experience a city (Budge, Citation2020; Yousefi and Dadashpoor, Citation2020). For example, SA-NFT can be integrated into mobile augmented reality applications, allowing users to roam the city and learn about its current and historical street art landscape. Alternatively, it can be used as the basis for an interactive encyclopedia of street artworks that can aid researchers in the study of a city's creative layers.

Street artworks are dynamic elements that are constantly being added to (and removed from) the urban realm. Like other temporary cultural elements, they have captured the attention of scholars, local authorities, and communities. In recent years, the value of street art as cultural heritage has been uncovered in the literature (e.g., Alves, Citation2017; Nomeikaite, Citation2017; MacDowall, Citation2006; Merrill, Citation2015). As a result, there is a growing interest in its conservation and documentation (e.g., Bonadio, Citation2018a; Chatzidakis, Citation2016; Hansen, Citation2018; Honig and MacDowall, Citation2017). More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter global protest movement have brought awareness of street art and graffiti as indicators in urban processes. For example, the Urban Art Mapping Research Project at St. Thomas University in Minnesota has created an open source dynamic database of street art related to the murder of George Floyd, as well as of other anti-racism murals. On their website, the researchers state that one of the purposes of the database is to enable future studies of ongoing movements demanding social justice and equality (see https://georgefloydstreetart.omeka.net/).

Digital documentation has become an important tool for preserving and managing cultural heritage. While recent years have witnessed significant improvements in documentation and data collection capabilities, there are still several challenges that can be addressed by using SA-NFT. Currently, there exist numerous street art archives, ranging in scope, scale, and reliability. These archives are managed by various stakeholders with differing agendas and objectives; some are state-owned, some are institutional or private collections, and others are open-source inventory networks (Back, Citation2019; Graf, Citation2018; MacDowall, Citation2006). The multiplicity of sources may inundate researchers with unreliable and overlapping data. It may also challenge their ability to develop a broader understanding of the urban street scape and require comprehensive manual work to prepare the data for analysis. Furthermore, digital archives are not immune to retrospective alteration, malicious tampering, or attacks, threatening their integrity and originality (Gipp et al., Citation2017). Tampering can target the content of the artwork, or the metadata of the archive. SA-NFT can address these issues by establishing a reliable archive that enables users to identify any change in the data, thus maintaining its integrity.

While many databases do not share the geographical information of street artworks (Graf, Citation2018), with the increasing use of geo-tagging, it has become more common to encounter databases that do share street art locations. This information adds a layer of valuable data about the artwork's context over time and space. Having proper access to the geo-data of street artworks can yield new research opportunities. For example, Honig and MacDowall (Citation2017) demonstrate that by extracting geo-data from social media apps such as Instagram or Twitter it is possible to create time sensitive street art and graffiti maps (Honig and MacDowall, Citation2017). But data sourced from social media represents the perspective of the art’s audience; therefore, the data can reveal when the street artwork was viewed, though not when it was created. Additionally, data extraction of this sort may be biased towards touristic locations where there are more viewers (Boy and Uitermark, Citation2017). Conversely, the blockchain ledger is a more equitable and accurate registry of street artwork because data are supplied by the artists themselves and therefore less subject to biases of location popularity.

One of the major challenges facing street art and graffiti documentation is their temporality. Street art and graffiti are ephemeral elements that constantly change a city's facades. Their placement in the outdoor public realm catalyzes their transformation and disappearance, whether through degradation and decay, or through deliberate interventions such as painting over, buffing, or removal (Hansen, Citation2018). These everlasting changes pose a challenge to their documentation, as Lachlan MacDowall states: “ … their geographic spread and ephemeral character make any comprehensive archiving a near impossibility” (MacDowall, Citation2006:140). While documentation of these artworks is indeed a daunting task, SA-NFT can be a valuable tool in building and maintaining a detailed chronological history of street art. This can open new opportunities for studying cities from a multi-dimensional perspective, incorporating both the spatial and temporal axes. Furthermore, SA-NFT can help to legitimize and reinforce street art as a form of cultural heritage deserving protection, cataloguing, and promotion.

Implementation Issues

SA-NFT relies on an application running on the artist’s private equipment (e.g., mobile phone), but also relies on the artist’s and user’s trust in this application. Such trust is commonly achieved by openness in implementation, allowing inspection to ensure that it delivers on its promise. As such, we foresee the application being developed with an open source, and likely by the open-source community. The open-source community should keep track of bugs and reported security issues and release further updates to solve those. Such a model has proven itself practical in many instances, such as in the case of the Mozilla Foundation that is developing and maintaining FireFox (https://foundation.mozilla.org), the Chromium Project (https://www.chromium.org), and the Linux operating system (https://www.linux.org/).

The main aspect of this system that will need external funding and resources is the database on which the photos are actually stored, whether this is a central database or a distributed one. There are two main stakeholders that may be interested in funding and maintaining it. First, due to the academic interest in creating a reliable and dynamic street art ledger, we see great potential in hosting such a database using university resources. Second, there is an economic potential in legalizing the trade of graffiti and street art IP (as described in the section regarding Street Art Related Rights) and there is a rise in the global trade of NFTs. Therefore, we believe that there are private sector stakeholders that would be interested in funding and promoting such a project for its economic benefits.

Conclusion

The SA-NFT provides a dynamic street art and graffiti ledger through which artists can anonymously register their artworks. SA-NFT enables artists to confirm and assert their IP rights, as well as reduce the risk borne by interested parties when utilizing the artwork. It does not and cannot resolve legal disputes involving ownership, infringement of IP rights, or other points of contention between clashing rights (Mendelson-Shwartz and Mualam, Citation2020). Nor does it, in most cases, eliminate the need for artists to reveal their identity before taking legal action.Footnote10

However, what SA-NFT can do is establish an indisputable link between artists and artworks. As time passes, artists may encounter difficulties in proving ownership of an artwork located in the public realm. This may potentially prevent them from asserting their IP rights. SA-NFT employs public key cryptography that uses a pair of linked keys, one private and one public, to sign and authenticate data.

Crucially, SA-NFT enables artists and interested parties to communicate and enter indisputable electronic contracts, while simultaneously maintaining the artist's anonymity. Furthermore, SA-NFT creates a database that allows users to browse or search existing artworks and contact their artists. This prevents artworks from being classified as “orphaned” or abandoned, a classification that could allow interested parties to use them without obtaining the artist’s permission and without risking IP infringement.

SA-NFT also protects interested parties by showing a clear record of communications with artists and contracts for use of their art. This proves if and under which stipulations they have permitted or denied the use of their artwork. Additionally, by providing proof of contact (or lack thereof), artists hold the ability to sue interested parties for IP infringement during the time in which they kept their anonymity.

As a result, SA-NFT can contribute significantly to limiting risk for both parties and ensure that if/when artists reveal their identity, the legal statues of the artwork will be clear. As a result, the power balances between artists and interested parties are altered. Indeed, if artists choose to sue the interested parties, they will be required to expose their identities, but they will do so with the confidence that their claim is well-founded. In addition, knowing that the artists can sue at any time will make the act of infringement much less worthwhile.

Lastly, SA-NFT can create a new relationships between artists and audience. It can also present a significant opportunity to increase the “digital” footprint of public art by establishing a broadly useful documentation platform. In so doing, SA-NFT would achieve multiple objectives and protect both public and private interests. It also has the potential to become a powerful tool for managing public spaces in a city alongside their embedded street art. The time is ripe for experimentation and a pilot project. It is up to cities, artists, and techies alike to seize this opportunity.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eynat Mendelson-Shwartz

Eynat Mendelson Shwartz is a postdoctoral researcher in the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology. She is an experienced architect and town planner. She is currently conducting a cross-national comparative study of mural policies.

Ofir Shwartz

Ofir Shwartz is a computer architect, security researcher, and technology enthusiastic. He holds a PhD from the Department of Electrical Engineering, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology. His main fields of expertise are high performance CPU architectures, computer and distributed systems security, and trusted execution environments. Nowadays he leads the security architecture in Google Cloud.

Nir Mualam

Nir Mualam is an associate professor in the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology. He is an experienced lawyer and a planner whose current research focuses on urban design, heritage policies and conflicts, planning processes, urban resistance campaigns, and planning institutions.

Notes

1 This term usually excludes gang graffiti, political graffiti slogans, and “simple” graffiti tagging.

2 In cases where the artwork is commissioned, the IP rights may belong to the commissioner and not the artist.

3 For example, in the case of English v. BFC&R East 11th Street LLC the court held that VARA should not be used as a tool to prevent development of property (Smith, Citation2013).

4 In order for a work of street art to enjoy copyright protection, it must be complex enough to be seen as an “artistic work” (Lerman, Citation2013). This suggests that simple artistic expressions, such as graffiti tagging, do not qualify for copyright protection.

5 For example, in 2010 the artist TATS CRU sued “Chrysler” car manufacturers for using his mural in a Fiat commercial, and in 2018 artist REVOK sent a cease and desist letter to H&M for incorporating his work in an advertising campaign. Both cases were settled out of the court system.

6 In contrast to copyright that protects the IP rights that are related to a specific work of art.

7 By original artwork we mean any new artwork created specifically for its designated location.

8 Hardware carrying built-in private keys with hardware assisted functionality have become common and are the new standard in device security solutions (e.g., Samsung Knox uses DUHK, Intel EPID and various Trusted Execution Environment solutions supporting cryptographic attestation [Intel SGX, Intel TDX, AMD SEV] use private keys that are baked into the hardware).

9 Since stencils and wheat pastes take little time to create, the multi-stage process is a bit different. For these media, artists will begin by uploading a photo of the stencil or poster prior to its placing. Only then will they add a photo of the intended wall and then the final artwork, via the application. Due to the nature of their creation, our presented proofing mechanism does not support quickly executed aerosol works, such as graffiti tags. This issue shall be resolved in future works or in the implementation stage.

10 To our knowledge, in most cases, people cannot claim IP right infringement before a court without revealing their identity. In some cases, trademark rights can be protected if they are associated to an anonymous LLC (limited liability company) (Kramer, Citation2019).

References

- A. N. Alves, “Why Can’t Our Wall Paintings Last Forever?,” Street Art and Urban Creativity Scientific Journal 3: 1 (2017) 12–19.

- B. O. Ansah, W. Voss, K. O. Asiama, and I. Y. Wuni, “A Systematic Review of the Institutional Success Factors for Blockchain-Based Land Administration,” Land Use Policy 125:February (2023) 1–13.

- A. J. Ashley, “Beyond the Aesthetic,” Journal of Planning History 14: 1 (2015) 38–61.

- A. J. Ashley, “The Micropolitics of Performance: Pop-Up Art as a Complementary Method for Civic Engagement and Public Participation,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 41: 2 (2021) 173–187.

- J. Austin, “More to See Than a Canvas in a White Cube: For an Art in the Streets,” City 14: 1–2 (2010) 33–47.

- N. Asokan, V. Niemi, and P. Laitinen,"On the Usefulness of Proof-Of-Possession,” 2nd Annual PKI Research Workshop (2003) 122–127.

- M. Back, “Managing Community Murals in an Urban Preservation Framework.” Master’s Thesis, University of Pennsylvania (2019).

- BANKSY, “Wall and piece,” Random House (2005).

- M. Blumenthal, “Encryption: Strengths and Weaknesses of Public-Key Cryptography,” CSRS (2007) 1–8.

- R. M. Bennett, M. Pickering and J. Sargent, “Transformations, Transitions, or Tall Tales? A Global Review of the Uptake and Impact of NoSQL, Blockchain, and Big Data Analytics on the Land Administration Sector,” Land Use Policy 83 (2019) 435–448.

- E. Bonadio, “Street Art, Graffiti and the Moral Right of Integrity: Can Artists Oppose the Destruction and Removal of Their Works?,” Nuart Journal 1: 1 (2018a) 17–22.

- E. Bonadio, “Graffiti, Street Art and Copyright,” Street Art Urban Creativity Journal 4: 1 (2018b) 75–80.

- E. Bonadio, The Cambridge Handbook of Copyright in Street Art and Graffiti, Cambridge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019a).

- E. Bonadio, “Despite Saying Copyright Is for Losers, Banksy Finally Goes to Court,” The Wire (2019b). <https://thewire.in/the-arts/despite-saying-Copyright-is-for-losers-banksy-finally-goes-to-court > Accessed September 5, 2020.

- E. Bonadio, “Banksy Brands Under Threat After Elusive Graffiti Artist Loses Trademark Legal Dispute,” The Conversation (2020). <https://theconversation.com/banksy-brands-under-threat-after-elusive-graffiti-artist-loses-trademark-legal-dispute-146642> Accessed July 20, 2021.

- J. D. Boy and J. Uitermark, “Reassembling the City Through Instagram,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42: 4 (2017) 612–624.

- K. Budge, “Visually Imagining Place: Museum Visitors, Instagram, and the City,” Journal of Urban Technology 27: 2 (2020) 61–79.

- V. Chandra and B. Rangaraju, Blockchain for Property A Roll Out Road Map for India (Delhi, India: India Institute, 2017).

- M. Chatzidakis, “Street Art Conservation in Athens: Critical Conservation in a Time of Crisis,” Studies in Conservation 61: 2 (2016) 17–23.

- S. Cloon, “Incentivizing Graffiti: Extending Copyright Protection to a Prominent Artistic Movement,” Notre Dame L. Rev. Online 92 (2016) 54.

- D. Crinnion, “Get Your Own Street Cred: An Argument for Trademark Protection for Street Art,” BCL Rev. 58 (2017) 257–285.

- L. Davi, D. Hatebur, M. Heisel, and R. Wirtz, “Combining Safety and Security in Autonomous Cars Using Blockchain Technologies,” International Conference on Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security (2019) 223–234.

- D. Droney, “The Business of ‘Getting Ip:’ Street Art and Marketing in Los Angeles,” Visual Anthropology 23: 2 (2010) 98–114.

- G. Eder, “Digital Transformation: Blockchain and Land Titles,” OECD Global Anti-Corruption & Integrity Forum (2019).

- S. A. Evans, “Taking Back the Streets ? How Street Art Ordinances Constitute Government Takings,” Fordham Intell. Prop. Media and Ent. L.J. 25 (2015) 685–746.

- M. S. Ferdous, M. J. M. Chowdhury, K. Biswas, N. Chowdhury, and V. Muthukkumarasamy, “Immutable Autobiography of Smart Cars Leveraging Blockchain Technology,” Knowledge Engineering Review 35:E3 (2019) 1–24.

- J. Ferrell, Graffiti, Street Art and the Dialectics of the City. In Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City (London: Routledge, 2016).

- S. F. Fischer, “Who’s the Vandal? The Recent Controversy over the Destruction of 5Pointz and How Much Protection Does Moral Rights Law Give to Authorized Aerosol Art?,” The John Marshall Review of Intellectual Property Law 14 (2015) 326–356.

- E. Gaetani, L. Aniello, R. Baldoni, F. Lombardi, A. Margheri, and V. Sassone, “Blockchain-Based Database to Ensure Data Integrity in Cloud Computing Environments,” paper presented at Italian Conference on Cybersecurity. Venice, Italy, Jan 17-20, 20170 (2017).

- C. H. Gebotys, Security in Embedded Devices (Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media, 2009) 2–4.

- B. Gipp, N.: Meuschke, J. Beel, and C. Breitinger, “Using the Blockchain of Cryptocurrencies for Timestamping Digital Cultural Heritage,” IEEE Technical Committee on Digital Libraries 13: 1 (2017).

- A. M. Graf, “Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: A Domain and Content Analysis.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania (2018).

- C. Grodach, “Art Spaces in Community and Economic Development: Connections to Neighborhoods, Artists, and the Cultural Economy,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 31: 1 (2011) 74–85.

- M. Halsey and B. Pederick, “The Game of Fame: Mural, Graffiti, Erasure,” City 14: 1–2 (2010) 82–98.

- S. Hansen, “Heritage Protection for Street Art? The Case of Banksy’s Spybooth,” Nuart Journal 1: 1 (2018) 31–35.

- C. D. Honig, and L. MacDowall, “Spatio-Temporal Mapping of Street Art Using Instagram,” First Monday 22: 3 (2017)

- W. Huang, and F. Dai. “Research on Digital Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage Based on Blockchain Technology,” Information Management and Computer Science 2: 2 (2019) 14–18.

- M. Iljadica, Copyright Beyond Law: Regulating Creativity in the Graffiti Subculture (London: Hart Publishing, 2016).

- M. Kaur, “Graffiti: On the Fringes of Art; Protected at the Edges of the Law,” Law School Student Scholarship Student Work 967, (2019).

- K. A. Kelly, “Moral Rights and the First Amendment: Putting Honor Before Free Speech?,” University of Miami Entertainment and Sports Law Review 11 (1993) 211–250.

- E. Kinsella, “A Stunning Legal Decision Just Upheld a $6.75 Million Victory for the Street Artists Whose Works Were Destroyed at the 5Pointz Graffiti Mecca,” Artnet news (2020) <https://news.artnet.com/art-world/5pointz-ruling-upheld-1782396> Accessed September 5, 2020.

- R. Kramer, “Painting with Permission: Legal Graffiti in New York City,” Ethnography 11: 2 (2010) 235–253.

- K. Kramer, “Gain Copyright Protection by Using an Anonymous LLC,” Law 4 Small business (2019) <https://www.l4sb.com/blog/leveraging-an-anonymous-llc-for-trademark-and-copyright-protection/> Accessed September 5, 2020.

- Y. K. Lee, H. Seung-wan, L. Sok-joon, C. Byung-ho, and G. L. Deok, “Anonymous Authentication System Using Group Signature,” paper presented at International Conference on Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems, 1235–1239, Fukuoka, Japan (March 16–19, 2009) 135-1239. IEEE, 2009.

- C. Lerman, “Protecting Artistic Vandalism: Graffiti and Copyright Law,” NYU Journal of Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law 2 (2013) 295–337.

- H. Liu, “Blockchain and Bills of Lading: Legal Issues in Perspective,” In P. Mukherjee, M. Mejia, and J. Xu, ed., Maritime Law in Motion (Cham: Springer, 2000) 413–435.

- L. MacDowall, “In Praise of 70K: Cultural Heritage and Graffiti Style” Continuum 20: 4 (2006) 471–484.

- T. Marks, “The Saga Of 5Pointz : VARA’s Deficiency In Protecting Notable Collections Of Street Art,” Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Law Reviews 35 (2015) 281–318.

- C. McAuliffe, “Legal Walls and Professional Paths: The Mobilities of Graffiti Writers in Sydney,” Urban Studies 50: 3 (2013) 518–537.

- E. Mendelson-Shwartz and N. Mualam, “Taming Murals in the City: A Foray into Mural Policies, Practices, and Regulation,” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27: 1 (2020) 1–22.

- E. Mendelson-Shwartz and N. Mualam, “ Challenges in the Creation of Murals: A Theoretical Framework,” Journal of Urban Affairs 44: 4-5 (2021) 1–25.

- S. Merrill, “Keeping it Real? Subcultural Graffiti, Street Art, Heritage and Authenticity,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21: 4 (2015) 369–389.

- L. Nomeikaite, “Street Art, Heritage and Embodiment,” Street Art and Urban Creativity Scientific Journal 3: 1 (2017) 43–53.

- D. Poisner, Inventor, Trusted System Clock (Patent No. US20040128549A1). Patent Application Publication. (2002) https://patents.google.com/patent/US20040128549

- M. L. Psiaki and T. E. Humphreys, “GNSS Spoofing and Detection,” Proceedings of the IEEE (2016) 104(6), 1258–1270.

- N. A. Riggle, “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68:3 (2010) 243–257.

- R. L. Rivest, A. Shamir, and L. Adleman, “A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems” Communications of the ACM 21:2 (1978) 120–126.

- T. Rychlicki,: “Legal Questions About Illegal Art,” Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice 3: 6 (2008) 393–401.

- P. N. Salib, “The Law of Banksy: Who Owns Street Art?,” The University of Chicago Law Review 82: 4 (2015) 2293–2328.

- A. Savelyev,: “Copyright in the Blockchain Era: Promises and Challenges,” Computer Law and Security Review 34: 3 (2018) 550–561.

- D. D. Schwender, “Does Copyright Law Protect Graffiti and Street Art?” Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art (London: Routledge, 2016).

- P. K.: Sharma, N. Kumar, and J. H.,: Park. “Blockchain-Based Distributed Framework for Automotive Industry in a Smart City,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 15: 7 (2018) 4197–4205.

- C. Y. Smith, “Street Art: An Analysis under US Intellectual Property Law and Intellectual Property's Negative Space Theory,” DePaul J. Art Tech. and Intell. Prop. L 24 (2013) 259–293.

- V. Thakur, M. N. Doja, K. Yogesh, Y. K. Dwivedi, T. Ahmad, and G. Khadanga, “Land Records on Blockchain for Implementation of Land Titling in India,” International Journal of Information Management 52 (2020) 1–9.

- A. Vishwa, and F. K. Hussain, “A Blockchain-Based Approach for Multimedia Privacy Protection and Provenance,” IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (2018) 1941–1945.

- B. Yapicioglu and R. Leshinsky. “Blockchain as a Tool for Land Rights: Ownership of Land in Cyprus,” Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law 12: 2 (2020) 171–182.

- A. Young, Street Art, Public City (London: Routledge, 2014).

- Z. Yousefi and H. Dadashpoor, “How do ICTs Affect Urban Spatial Structure? A Systematic Literature Review,” Journal of Urban Technology 27: 1 (2020) 47–65.