ABSTRACT

In this study, we focused on teachers’ knowledge and awareness of LGBT+ issues in a Catholic secondary school in Ireland. We explored the barriers teachers encounter that prevent them from being openly supportive of LGBT+ students. For this study, 40 teachers completed an online questionnaire, which was followed by a smaller focus group interview comprising 6 teachers. The findings demonstrate a lack of knowledge about LGBT+ issues among teachers, and the majority have not received any training related to this topic. This can be linked with their lack of awareness of policies, supports, and resources available to help LGBT+ students. The findings suggest a lack of self-awareness because some teachers were not supportive of issues that affect LGBT+ students but believed otherwise. It also is clear from the results that there are mixed perceptions of what is acceptable to discuss and support due to the Catholic ethos of the school. These findings reflect several barriers to supporting LGBT+ students and issues.

Introduction

Over the last several years, there have been positive large-scale social changes in Ireland for the LGBT+ community, with the passing of the marriage equality referendum, gender recognition for over-18s, and a change in the legislation of Section 37 of the Employment Equality Act (1998) that protects LGBT+ workers in religious institutions. However, these positive changes have not had a major effect on schools, considering a negative school climate still exists for LGBT+ students across Ireland (Pizmony Levy & To Youth Services, Citation2019). In Ireland, most schools are still managed or owned by religious institutions. According to Ryan (Citation2019), 95% of primary schools and 48% of secondary schools have a Catholic ethos, which suggests that most schools have an ethos that contradicts the sexual identity of some of their LGBT+ staff and pupils (Gowran, Citation2004). In this study, we aimed to gain insight into teachers’ experiences in a Catholic secondary school and whether they felt the ethos of the school had any effect on the inclusivity of their thoughts and actions. Research on the lack of knowledge and training on LGBT+ issues has been carried out internationally (Kitchen & Bellini, Citation2012; Swanson & Gettinger, Citation2016), but there remains a lack of research in Ireland on these issues. Instead, many studies in Ireland have focused on the experiences of students and teachers who are LGBT+.

Literature review

What can schools do to address the negative climate?

According to Dessel et al. (Citation2017), schools continue to be a cause of concern for educators because of the unfavorable climate that exists for LGBT+ students. Notwithstanding this, research has shown that many schools are updating their policies, introducing student support groups such as Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs), and providing LGBT+ related training to staff to combat the heteronormative culture in many schools. Swanson and Gettinger (Citation2016) examined the effect of these three supports and found that schools with an active GSA, anti-bullying policies that address homophobic/transphobic bullying, and staff training all reported a higher number of teachers engaging in supportive behaviors.

These policies and programs are essential to challenge heteronormativity in schools. If LGBT+ issues are not highlighted, then heterosexuality and gender normativity will remain the norm and go unnoticed even by those who may be open to change (Blair & Deckman, Citation2019). According to Chesir-Teran and Hughes (Citation2009), these supports, although important, cannot bring about meaningful whole-school change unless those implementing them, such as classroom teachers, commit to altering their attitudes and behaviors. Recognizing the key role of teachers and the importance of their knowledge and awareness in supporting LGBT+ students and issues cannot be understated.

According to Kosciw et al. (Citation2009), teachers are sources of social support whose roles are essential in alleviating the harmful and damaging effects of a hostile school climate on LGBT+ students. Whereas students can gain social support from their personal relationships with family members and friends, students spend a large amount of their lives in school. Kosciw et al. (Citation2013) surveyed 5,730 LGBT secondary students in the United States and found that the most substantial positive influence on their self-esteem, achievement, and attendance was the role of supportive teachers. Considering teachers’ vital role in providing support, we examined teachers’ knowledge and awareness of LGBT+ issues and explored any barriers they encounter in providing positive social support to these students.

Barriers preventing support for LGBT+ students

Despite teachers recognizing the importance of their supporting roles, Meyer et al. (Citation2015) found that the frequency in which teachers actively take on these supportive roles is significantly lower. This gap illustrates that several barriers still prevent many teachers from intervening on LGBT+ students’ behalf.

Lack of knowledge/training

According to Swanson and Gettinger (Citation2016), one of the main reasons teachers do not engage in LGBT+ issues is their lack of knowledge on the subject. Using a survey method of 98 teachers in Grades 6–12, the researchers found that 55% of educators reported that they were unsure of how or when to intervene on behalf of LGBT+ students who were being victimized. The literature suggests that teachers are unprepared and lack the knowledge to deal with homophobic and transphobic language because they have not received adequate training on LGBT+ issues. Mayock et al. (Citation2007) described the provision of continuing professional development in Ireland for social, personal, and health education and relationships and sexuality education as a one-off and found a virtual absence of training for social, personal, and health education in universities for preservice teachers. Ireland is not alone on this issue, as other countries, such as the United States, Canada, and Australia, have called for better training on LGBT+ issues in schools for teachers (Buston et al., Citation2002; Milton et al., Citation2001; Taylor et al., Citation2016).

Following a survey completed by 206 respondents based in Ireland, Minton et al. (Citation2008) stated that training on issues including homophobic bullying should be included in both preservice and in-service courses as “a matter of concern” (p. 187). Research carried out in Ireland by O’Donoghue and Guerin (Citation2017), through five semi-structured interviews in secondary schools, found that training increased teachers’ comfort in dealing with homophobic and transphobic bullying and that this, in turn, increased students’ comfort in seeking support from those teachers. Despite the positive effect of training, Anagnostopoulos et al. (Citation2009) reported a lack of training on these issues being offered to teachers. These researchers pointed out that if training is not accessible, it remains a barrier for teachers who will continue to feel uncertain about their obligation to receive training. The lack of knowledge and training also can cause teachers to feel anxiety and a sense of apprehension when faced with problems that arise concerning LGBT+ issues.

Apprehension and avoidance

Several researchers found that teachers can be hesitant to disrupt the heteronormative culture of schools out of fear of disapproval from the school community and conservative parents (Gerouki, Citation2010; Taylor et al., Citation2016; Vega et al., Citation2012). As explained by Ahmed (Citation2004), when individuals fear something new, they tend to hold on to what is familiar because it gives a sense of security and comfort. In the same vein, Payne and Smith (Citation2014) suggested that “the familiar” in these cases are educators trying “to maintain a safe and civil learning environment” (p. 415). When issues involving transgender students arise that may disrupt this type of environment, teachers’ reaction can be to make discreet accommodations for these students, such as not dealing with the issue or bending the rules instead of affirming their identities. According to Payne and Smith, these actions can have a negative effect on students and contribute to a hostile school climate. Furthermore, Journell (Citation2017) argued that it is important for teachers not to shy away from controversy in the classroom, because the way “teachers frame controversial identity issues within their classrooms sends messages about the value and legitimacy of certain groups of students and segments of society” (p. 349).

The theme of fear also emerged from the literature regarding individuals being perceived as LGBT+ (O’Higgins-Norman, Citation2009; Zack et al., Citation2010). These emotions were found to be felt by teachers in both Irish and international studies. An interesting finding from Berrill and Martino (Citation2002) identified that male teachers in both Canada and Australia place themselves under “self-surveillance” to avoid being perceived as LGBT+ and, in turn, possibly labeled “a pedophile or deviant” (p. 62). Similarly, results from an online survey of 46 heterosexual university students in the United States carried out by Goldstein and Davis (Citation2010) showed that even though the participants were self-proclaimed allies, half of the respondents would want other people to know that they were heterosexual if they were participating in an LGBT+ event or discussion, out of concern of stigma through association. These feelings of apprehension and anxiety also can be attributed to teachers working in schools managed or owned by religious institutions.

Based on the findings of Payne and Smith (Citation2014), teachers’ fear and anxiety can be a barrier to feeling comfortable discussing LGBT+ issues, particularly those involving transgender youth. Teachers reported that sometimes this apprehension is related to their own feelings about job security, especially those employed by faith-based schools. According to research in Ireland by O’Higgins-Norman (Citation2009), the ownership and control of schools by religious patrons significantly harm the implementation of policies and programs that improve equality. This is troublesome considering that most schools in Ireland, notably primary schools, have a Catholic ethos (Ryan, Citation2019).

Separate research studies carried out in Ireland before 2015 found that lesbian and gay teachers who worked in Catholic schools were afraid they might lose their jobs because of their sexual orientation (Neary, Citation2013; Norman & Galvin, Citation2005). These studies predated legislation passed by the government of Ireland in 2015, which amended Section 37 of the Employment Equality Act (1998). Before this amendment, religious schools had the power to dismiss any staff who acted in a way that contradicted the school’s ethos. However, this recent change does not seem to have altered how LGBT+ teachers feel. Neary et al. (Citation2018) found that teachers still have a “potent sense of fear and wariness about religious ‘ethos’ in schools” (p. 439) and that many respondents reported avoiding teaching posts in religious schools for this reason.

Complementary to this, McNamara and Norman (Citation2010) argued that if most schools have a Catholic ethos and teachers feel they cannot allow their LGBT+ status to be known or perceived as LGBT+, then it is improbable that these teachers will be proactive in supporting students and addressing homophobic bullying. In a separate study in Ireland, O’Higgins-Norman (Citation2010) pointed to another barrier to equality within schools: It is unlikely that a school with a Catholic ethos could provide a relationship and sexuality education course that portrays homosexuality in a positive light. It is hard to argue with this, as the Catholic Church has stated that homosexuality is considered “an intrinsic moral evil; and thus the inclination itself must be seen as an objective disorder” (Ratzinger, Citation1986, p. 1). Research has shown that policies promoting equality for LGBT+ students are implemented poorly or not at all in certain schools (McNamara & Norman, Citation2010). This clearly shows how the religious ethos of a school and the fear it causes teachers can be potential barriers to implementing programs and policies that support LGBT+ students.

Unawareness and heteronormativity

Other barriers that emerged from the literature include a lack of awareness of LGBT+ issues because of the heteronormative culture in schools and the importance of drawing attention to homophobic and transphobic comments. Swanson and Gettinger (Citation2016) noted that some teachers are unaware of how important it is to address incidents when they hear homophobic or transphobic comments. The researchers reported that 83% of teachers in the study were unaware of the needs and issues that LGBT+ students face. In a U.S. study, Kosciw and Diaz (Citation2006) found that “school staff were less likely to intervene regarding homophobic remarks or remarks about gender expression than racist or sexist remarks” (p. xiii). Similarly, after conducting focus group interviews with 26 U.S. high school students, Snapp et al. (Citation2015) found that teachers generally missed opportunities to intervene when homophobic and transphobic comments were made and that students felt like they were the ones who had to speak up in defense of their LGBT+ peers. These instances of teachers avoiding issues are similar to findings in a Canadian study carried out by Meyer (Citation2008), who reported that most teachers felt they could not stop LGBT+ harassment alone and that it was as if their “eyes are covered by institutional and social barriers that tell them not to see gendered harassment and not to intervene” (p. 566). Kosciw et al. (Citation2009) found that many teachers do not intervene during instances of homophobic bullying because they underestimate the consequences of inaction. When students feel like teachers openly ignore this behavior or that the teachers’ responses are ineffective, they are less likely to report incidents (Kosciw et al., Citation2014).

Heteronormativity is the presumption that everyone is heterosexual and that this is the only normal way to exist (Warner, Citation1993). According to DePalma and Atkinson (Citation2009), heteronormative culture can be seen through educators’ passive behavior. Similarly, Vega et al. (Citation2012) maintained that if teachers fail to take action when homophobic remarks are made, teachers send a silent message to students that homophobia is acceptable. Based on the findings of Zack et al. (Citation2010), some teachers only verbally reprimanded students for using the words fag and homo, taking no further action. These researchers argued that perhaps “many teachers fail to realize how bigoted and damaging this language is” (p. 103), and may think it is part of the vernacular of students or deem it to be banter. However, this fits into the heteronormative culture that exists in schools. Unfortunately, in a situation like this, other students may think that when teachers “do nothing to address homophobic rhetoric, they send the message that the speech is acceptable” (Zack et al., Citation2010, p. 103).

In order to counter heteronormative culture, McIntyre (Citation2009) suggested that the first step is to educate teachers on what it is. Likewise, Gerouki (Citation2010) proposed that teachers must receive training in order to reflect on and change their assumptions about sexuality. If they are unaware of the heteronormative culture in schools, they will likely shape students’ experiences through the heteronormative lens. As explained by Vega et al. (Citation2012), if teachers can use their influential position within and outside of the classroom to guide positive language and behavior in students, teachers can help create a more inclusive environment and establish new norms.

Method

Research methods and approach

We conducted this study using an interpretivist rather than positivist approach. Because positivism is mostly associated with quantitative data and statistical analysis, this research primarily dealt with participants’ feelings, perceptions, and underlying opinions, which are difficult to measure scientifically. An approach using interpretivism is best used to explore and interpret a phenomenon when meanings and interpretation take precedence (Cohen et al., Citation2007). We aimed to understand what knowledge and awareness participants had about LGBT+ issues in their school setting rather than empirically proving or disproving any hypothesis. In order to gather quantitative and qualitative data, we used a mixed-methods approach. Due to the sensitive nature of discussing LGBT+ issues, a questionnaire without any triangulation could have been limited by participants being well intentioned, trying to give what they felt was the correct answer rather than their honest one. Open-ended questions in the questionnaire and responses to vignettes of hypothetical situations during the focus group provided rich qualitative data from participants. Interpretivism was the most suitable to analyze these data and provide context to the quantitative data gathered from the closed-ended questions in the questionnaire. We also used these quantitative data to measure the participants’ knowledge of LGBT+ terminology, determine their awareness of supports in the school, and inform the questions in the semi-structured focus group.

This case study took place in a coeducational secondary school with a Catholic ethos in Ireland. When the study occurred, it was a medium size school and had student numbers between 600 and 800. It had between 50 and 70 teaching staff members, including management. As a Catholic school in Ireland, it is partially funded by the state, and the remainder of its funding is controlled by a Catholic Education Authority that has its own Board of Management and trustees to oversee the management of the school. It is not a fee-paying school, which may be different from many other types of Catholic and other religious schools in and outside of the Republic of Ireland.

Quantitative data

All of the teaching staff, support staff, and senior management in the chosen school formed the sample of participants. We developed an online questionnaire consisting of 34 questions based on findings in the literature. The link was distributed via an online platform to 60 people, and 40 participants responded. Responses were gathered instantly, and the answers to open-ended questions were designed to guide focus group interviews in Phase 2.

The quantitative data were gathered, and charts illustrated group patterns for each question, which helped us analyze patterns in the responses. Percentages were calculated automatically, and individual responses were shown in an Excel spreadsheet. The spreadsheet was manually color-coded before printing and enlarging to look for patterns in the data. Filters in Excel were used to focus on different demographics to search for possible correlations between knowledge and awareness of LGBT+ issues and responses to gender, training, and whether they were part of management or held a post of responsibility.

Phase 2: Qualitative data

There were six responses from the questionnaire to participate in the focus group, and all six participants were female. No males volunteered to take part; we noted this as a further discussion point within the research. The focus group took place via Zoom, and all participants were reminded beforehand that their identity would be known to other teachers taking part in the call. All participants were given pseudonyms during the transcription process to protect their identity.

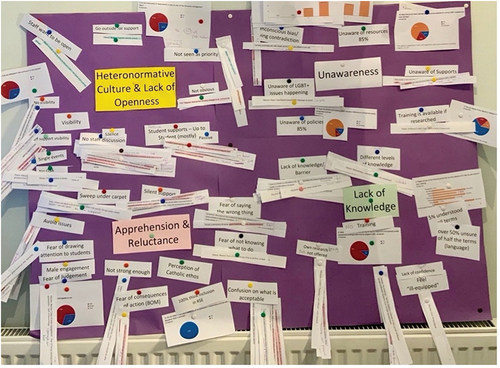

We used the six-phase thematic analysis model outlined by Braun et al. (Citation2016) to analyze the qualitative data from the open-ended questions in the questionnaire and the focus group transcript: familiarization, coding, theme development, revision, naming, and writing up. We carried out coding manually by highlighting words and phrases that were similar, with different-colored highlighters. We then placed the coding phrases beside quotes from participants and grouped similar responses together. Following this stage, we developed themes by organizing the codes into higher level patterns that formed candidate themes (Braun et al., Citation2016). Once the candidate themes were recognized, we reviewed them to ensure that they represented the data appropriately and addressed the research question. Next, we named the four emerging themes and placed them on a board to create a thematic map. Finally, we triangulated the data with the questionnaire results and also placed them on the map to find consistencies and discrepancies (see ).

Findings and discussion

We identified four themes from our thematic analysis of the data from the questionnaire and focus group: lack of knowledge, unawareness, a heteronormative culture or lack of openness in the school, and a feeling of apprehension and avoidance. The key findings leading to these themes are discussed in this section.

Lack of knowledge

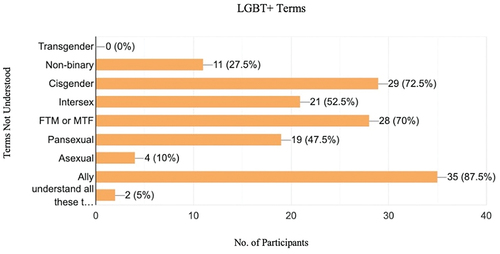

Findings showed that most questionnaire participants know what the letters in the acronym LGBT+ represent but that there is a lack of knowledge in terms of understanding the terms, particularly those that describe other parts of the community represented by the plus sign. summarizes the responses to terms that participants did not understand or were unsure of their meanings. From the questionnaire results, 87.5% of participants indicated that they did not understand the term “ally,” and the term “cisgender” was selected by 72.5%. “Transgender” was not selected by anyone, implying that all participants know and understand this term. However, 70% were unaware of “FTM or MTF,” which is used by transgender individuals who have transitioned from female to male or from male to female, respectively. Combining the quantitative data, 57% of respondents did not understand at least half of the terms. This suggests that although participants have a basic surface knowledge of the acronym LGBT+, they have more limited knowledge about the vocabulary used to describe the broader community, specifically related to gender identity. Similarly, Mason et al. (Citation2017) found in their study of U.S. elementary schools that teachers lack the knowledge and familiarity with the terminology surrounding gender-nonconforming youth. Also, Gibbons and O’Shea (Citation2006) noted that LGBT students want teachers to understand and use the language related to LGBT identities so these students will feel more accepted.

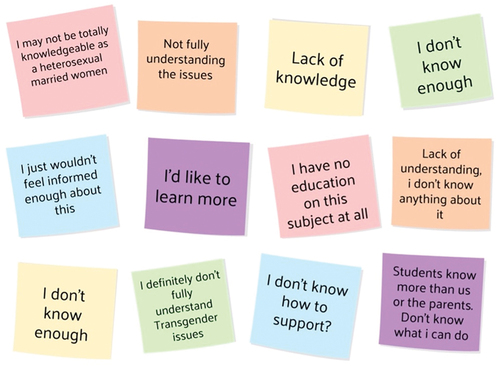

Similar to the findings of Swanson and Gettinger (Citation2016), where lack of knowledge was considered the main barrier to teachers supporting LGBT+ students, almost half of the participants (47.5%) in our study viewed their lack of knowledge as a barrier. Questionnaire participants explained that they didn’t know how to support LGBT+ students or understand some of the issues they face. displays quotes that participants noted in the questionnaire. From the focus group, it was clear that a common barrier for participants was their lack of knowledge of how they could correctly support students or respond to issues such as homophobic/transphobic comments. Joanne noted how she would rely on her instincts and initial reactions:

I just feel ill equipped. I wouldn’t have the confidence to know am I saying—am I dealing with it in the right way. I would know—instinctively, I would have a certain feeling about what I think I should do, but I wouldn’t know if it’s the right thing to do or say, because I haven’t done any training.

Other responses also suggested that teachers rely on their instincts to address LGBT+ issues because they have not received training. The findings also showed that only 10% of staff have attended LGBT+ related training. Noteworthy from the focus group is that both participants who attended training had researched the course they attended by themselves, and courses like this had not been advertised or offered to teachers. This point was raised previously by Anagnostopoulos et al. (Citation2009): that there is an absence of training offered to staff and that teachers continue to feel uncertain about their obligation to receive training.

The focus group drew attention to this and suggested that there should be LGBT+ related training for staff but in a more meaningful way than a one-off workshop. Naomi remarked,

I think Diana’s thing earlier of somebody coming in to facilitate something would be very, very powerful, but not this [pause]. We do an awful lot of ticking-the-box exercises. So, somebody comes in and talks to us about team teaching for 30 minutes. That’s us sorted on team teaching. That’s a lot of rubbish, as we know. We’d need to be doing far more than one little workshop or one little input.

In the same vein, McCormack and Gleeson (Citation2010) concluded that a whole-school approach is necessary to train teachers so they acquire the knowledge to feel comfortable tackling issues that affect LGBT+ students.

Unawareness

The theme of unawareness was illustrated by the lack of familiarity associated with LGBT+ issues, policies, resources, and other supports and the lack of perception of how supportive participants believe they are. In the questionnaire, participants were asked about their awareness of specific references to homophobic/transphobic bullying in the school’s anti-bullying policy, but 87.5% did not know if it was included. The same percentage were unaware of whether the school had materials that could support LGBT+ students and their families. In response to the question about school supports, there was no mention of the three critical supports that Swanson and Gettinger (Citation2016) put forward to improve the school environment for LGBT+ students: GSAs, policies, and training. Fifty percent did not mention any supports or give examples of specific supports, suggesting an unawareness of those available at the school.

Whereas all participants noted in the questionnaire that they had the self-perception of being supportive of LGBT+ individuals and issues, this provides evidence of a lack of self-awareness because 32.5% and 20% were not supportive of issues concerning the fairness of the school’s uniform policy and the hypothetical introduction of gender-neutral toilets, respectively. This suggests that up to 80% of participants are not as supportive as they believe themselves to be. The use of language from some participants when answering open-ended questions, such as “boys wearing skirts” and “finding ‘camp’ very difficult to cope with,” indicates a lack of knowledge in areas of gender identity and stereotyping. These types of comments also were made by participants who believed themselves to be supportive. Smith (Citation2018) would argue that these teachers believe they are tolerant and supportive because it aligns with their narrative of supporting all students, but this is not the case. Overall, the data presented allude to a lack of awareness on the issues relating to LGBT+ students at the school.

Heteronormative culture/lack of openness

As mentioned previously, DePalma and Atkinson (Citation2009) argued that a heteronormative culture can be seen through educators’ passive behavior. This behavior, such as silence on the matter of LGBT+ issues, is represented in the results. Thirty percent of the questionnaire participants felt that there is a lack of staff discussion surrounding LGBT+ issues, and a focus group participant felt that this encourages a sense of ignorance among staff on the topic. This silence is seen as a barrier to supporting LGBT+ students, because there is no discussion on how to support these students specifically. The following are examples of responses (questionnaire participants are numbered, whereas focus group participants have pseudonyms):

I have never heard it mentioned by senior management or in a SPHE [social, personal, and health education] meeting, for example. … LGBT+ is conspicuous by its visual and audible absence in our school.

[Response to any barriers] The fact that LGBT+ has not been on the tables for discussion or inclusion at any point in my 16 years in school.

I think the fact that there isn’t a discussion around any of these issues in our school … that’s only going to encourage the ignorance that many of us may feel. … I think it’s quite tragic that if it has been mentioned, it’s never gone anywhere.

These comments suggest that there is no dialogue among the general staff relating to these issues and, because of this silence, there is a feeling that it should not be discussed. Atkinson (Citation2002) described this as the “tyranny of silence” (p. 125). She concluded that “every absence constitutes a particular kind of presence” (p. 125) and that educators are teaching about homosexuality by not discussing it and not including it in the curriculum. This sends a message that homosexuality is not accepted. Similarly, 70% of questionnaire participants did not feel that LGBT+ lives are represented in the curriculum, which further adds to the silence addressed by Atkinson. Those participants who felt that there were signs of visibility in the school drew attention to posters and a diversity day held the previous year. A questionnaire participant offered thoughts on this form of visibility and felt that recognizing diversity one day a year does not normalize it and that it would need to be embedded into the curriculum and seen more often: “I feel there is no normality around LGBT+ students and inclusion only happens on Diversity Day, etc., instead of all year round” (Participant 34). This sentiment is similar to Grant et al. (Citation2021), who described these one-off days as necessary for inclusion, but when executed alone with no other supports, only “create an illusion of equality” (p. 966).

Finally, there was also a suggestion that management may not model the behavior that LGBT+ issues are important through their lack of open dialogue, not prioritizing continuing professional development in related subjects, and not advertising LGBT+ related training. According to McNamara and Norman (Citation2010), management’s behavior demonstrates how staff and students act, which could be reflected by a 45% response rate of management and those in posts of responsibility who took part in our study about LGBT+ issues.

Whereas these findings suggest a heteronormative culture that lacks open discussion, another view could be that this culture and silence on LGBT+ issues are related to the school’s religious ethos. This view is discussed further in the next section.

Apprehension and avoidance

The findings showed a theme of apprehension and avoidance within the school relating to LGBT+ issues and the school’s ethos. Twenty-five percent of respondents felt that the Catholic ethos of the school was a barrier preventing them from supporting LGBT+ students and issues openly. There was a sense of apprehension that there would be negative consequences from the trustees and Board of Management if staff showed active support for LGBT+ initiatives. The following comments were made:

[Response to any barriers] Yes, religious aspect of school makes me unsure of what is accepted by school and what is not.

I have wondered to what extent I would be able to discuss with students and teachers, issues like same-sex marriage (and also other issues that have a difficult relation with the Church, like abortion) considering that the school is Catholic. And, with students, you can expect them to go home and tell their parents about it, so I have felt like you need to be cautious.

These respondents’ perception of the Catholic ethos is that it disagrees with LGBT+ issues and, therefore, cannot be represented in the school openly. There is apprehension and confusion about what is acceptable to discuss in case there are negative consequences from the trustees and the Board of Management. These concerns were raised by Gowran (Citation2004), who conducted interviews with LGBT+ primary school teachers in Ireland. She concluded that teachers feel uncomfortable actively promoting activities and policies that contradict the school’s ethos. In our study, Participant 9 maintained that students may go home and tell their parents they were discussing topics with which the Catholic Church disagrees. This line of thought shows an apprehension of the consequences of parents’ reactions. It also corresponds to the literature analysis by Vega et al. (Citation2012), who found that teachers can be hesitant to disrupt the heteronormative culture of schools out of fear of disapproval from the school community, including parents.

Whereas 25% of our questionnaire participants were apprehensive or unsure of what is accepted at the school, 12.5% had a more positive perception of what is meant by having a Catholic ethos. One such participant stated,

I believe we should have visible signs of support. Without such, we are not showing support. As a practicing Catholic, I believe to treat others as how I would like to be treated is a motto. The word catholic means universally acceptable—all welcome.

This comment reflects a sense that the Catholic ethos can be interpreted as open and supportive of LGBT+ issues.

In the focus group, Diana pointed out that if staff cannot be themselves or openly support issues, then the Catholic ethos is not strong enough in the school. She stated, “I’d hate to think that there was members of our staff that were suffering in silence, so they couldn’t be themselves, so they couldn’t … behave or do whatever … I don’t like that. That’s not Catholic ethos. That’s no ethos.” From Diana’s observations, there would be more openness and understanding if there were a stronger presence of Catholic ethos within the school. These polar views have led to confusion among some teachers and apprehension among others about what is acceptable to say and how to act in a Catholic school.

However, as 25% of participants felt that the ethos of the school was a barrier to supporting students, and only 12.5% believed the ethos to be inclusive, this leaves 62.5% who did not mention the ethos of the school. One could argue that this silent majority either felt the need to avoid the topic or that there is a heteronormative culture in the school, of which these participants are unaware. Either way, a large majority of participants steered clear of involving themselves in the discussion of religion.

Alongside apprehension about how to deal with situations correctly and without offending anyone, responses from both sets of data revealed a trend of inconsistency in applying uniform policy in the school. When participants were asked if they thought the uniform policy was fair, multiple responses indicated that teachers avoid addressing issues involving LGBT+ students wearing makeup, to avoid broaching the subject. As mentioned in the literature review, Payne and Smith (Citation2014) argued that providing discreet accommodations, such as allowing some LGBT+ students to break a rule, even if well intentioned, does not affirm their identities.

We also found examples of teachers with good intentions in dealing with situations involving homophobic comments, but they tended to avoid having conversations about homophobia and addressed it differently. When asked about how participants would respond to homophobic comments they heard, Marsha explained how she has reacted in the past:

I could be wrong, but in the past, when anyone would have said something to me or to anyone else like, “That’s so gay,” I said, “Well, it’s so happy.” I always be like a sarcastic comment back, you know, but that’s my—always my initial reaction. If I had any problems, to be honest with you, Mariah [a teacher in the school] is my go-to.

Marsha rationalized that she tries to avoid the situation by using sarcasm or passing it to a more experienced staff member. While having good intentions, Marsha was avoiding the conversation about homophobia. According to Vega et al. (Citation2012), avoiding homophobic language can send a message through silence that it is acceptable. This sentiment also aligns with the view of missed learning opportunities addressed by Snapp et al. (Citation2015). These situations could be used as teachable moments to address homophobic and transphobic behavior and affirm the identities of LGBT+ students.

Finally, 50% of males in the sample took part in the questionnaire, and no males volunteered to participate in the focus group. The participants in the focus group suggested that it could be the case that males feel reluctant to get involved in LGBT+ matters because of a fear of the perception of being LGBT+. The following is a quote from Marsha:

A good friend of mine is a vice principal of a primary school, and he’s gay. And for years, people thought he was a pedophile because he was gay, do you know what I mean? It was very difficult for him working as a primary school teacher.

This situation corresponds to findings in Berrill and Martino’s (Citation2002) study, in which Canadian and Australian male teachers felt this way and actively tried to prevent being perceived as LGBT+. It is unclear why males at the school in our study were less responsive than females, but this offers a possible reason.

Conclusion

The overall findings suggest a lack of LGBT+ knowledge among staff, which is attributed to a lack of training. According to Payne and Smith (Citation2011), this is not surprising because if LGBT+ training is not compulsory, it is unlikely that teachers are aware of the need for it. This lack of awareness is highlighted by the majority of staff being unfamiliar with policies, supports, or resources available in the school. It also is evidenced by the insufficient visibility of the topic in the curriculum and the absence of staff discussion. The findings show mixed perceptions of what is acceptable to discuss and support in a Catholic school. This confusion is perceived as a barrier to those who are apprehensive that there could be negative consequences from the school community if they were viewed to be too welcoming or supportive of LGBT+ issues in the school. It is unclear if there would be negative consequences, but it is evident that teachers feel it is a possibility and, therefore, a barrier to supporting LGBT+ students openly. A large majority of our participants did not engage with the idea that the school’s ethos is at fault for the lack of knowledge or awareness of LGBT+ issues in the school, but there are misconceptions about what the school’s ethos means for issues not supported by the teachings of the Catholic Church. One participant mentioned that they were unsure of whether they could discuss the topics of abortion or homosexuality, as they considered this against the teachings of the Catholic Church. The lack of awareness and absence of open dialogue on these issues have contributed to this confusion and, perhaps, prevented teachers from openly collaborating and discussing how to be more supportive of LGBT+ students.

Recommendations

Based on the findings from this research, we offer three recommendations to address the issues and themes that emerged during the study:

A whole-school staff training program that covers terminology and how to support LGBT+ students in faith-based schools should be introduced. This program should address the Catholic ethos of the school and tackle the mixed perceptions that arose during this study of what is acceptable to be discussed.

All staff should be made aware of the school’s policies, and management should update any that do not contain references to LGBT+ issues.

This school does not have a GSA, but launching such a club would help improve the visibility of LGBT+ issues and provide a safe space for students. Its presence also would disrupt the heteronormative culture and open a dialogue to demystify what is acceptable in a Catholic ethos school.

If these recommendations were acted upon, it would provide teachers with improved knowledge and awareness of LGBT+ issues within the school and help tackle the barriers they face in supporting LGBT+ students.

Hopefully, the findings and recommendations gained from this research will raise awareness of this topic and contribute to a more open and supportive environment for LGBT+ individuals in this school and beyond. However, raising awareness does not change behavior alone, and this study should be used as a first step to changing the heteronormative culture that exists in schools.

Further study

The findings of this study provide insight into only one particular Catholic secondary school in Ireland. These findings could benefit other schools, and further study is encouraged in this area. This research also identified other areas for further research that would be worthwhile, such as these two: (1) examining the effectiveness of LGBT+ related training and education programs for preservice and in-service teachers in Ireland and (2) examining the views of parents, students, and the wider school community on the visibility of LGBT+ issues in faith-based schools. A study on the latter could provide clarity to those who assume that there would be negative consequences and reactions from the school community to discussing LGBT+ issues in a Catholic school.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen McShane

Stephen McShane is a lecturer in the Institute of Foundation Studies at Arden University in London, England and, at the time of this study, he was a master’s student at Dublin City University in Dublin, Ireland. He taught mathematics and science for over ten years in secondary schools and has a passion for promoting diversity and inclusion in the classroom and improving awareness of supports needed for minority groups at all levels in education. His research interests include improving teacher training and inclusive practice.

Margaret Farren

Margaret Farren is an associate professor in the School of STEM Education, Innovation, and Global Studies in the Institute of Education at Dublin City University and a codirector of the International Centre for Innovation and Workplace Learning. She teaches in master’s degree programs, supervises master’s and doctoral students who use research approaches that contribute to personal knowledge and knowledge in the field of practice, and is actively involved in European projects. Her research interests include reflective practice, action research, and inquiry-based learning.

References

- Ahmed, S. (2004). The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh University Press.

- Anagnostopoulos, D., Buchanan, N. T., Pereira, C., & Lichty, L. F. (2009). School staff responses to gender-based bullying as moral interpretation: An exploratory study. Educational Policy, 23(4), 519–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904807312469

- Atkinson, E. (2002). Education for diversity in a multisexual society: Negotiating the contradictions of contemporary discourse. Sex Education, 2(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810220144873

- Berrill, D. P., & Martino, W. (2002). Pedophiles and deviants”: Exploring issues of sexuality, masculinity, and normalization in the lives of male teacher candidates. In R. M. Kissen (Ed.), Getting ready for Benjamin: Preparing teachers for sexual diversity in the classroom (pp. 59–69). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Blair, E. E., & Deckman, S. L. (2019). “We cannot imagine”: US preservice teachers’ Othering of trans and gender creative student experiences. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102915. Article 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102915

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 191–205). Routledge.

- Buston, K., Wright, D., Hart, G., & Scott, S. (2002). Implementation of a teacher-delivered sex education programme: Obstacles and facilitating factors. Health Education Research, 17(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/17.1.59

- Chesir-Teran, D., & Hughes, D. (2009). Heterosexism in high school and victimization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 963–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9364-x

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6th ed.). Routledge.

- DePalma, R., & Atkinson, E. (2009). ‘No outsiders’: Moving beyond a discourse of tolerance to challenge heteronormativity in primary schools. British Educational Research Journal, 35(6), 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920802688705

- Dessel, A. B., Kulick, A., Wernick, L. J., & Sullivan, D. (2017). The importance of teacher support: Differential impacts by gender and sexuality. Journal of Adolescence, 56(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.02.002

- Gerouki, M. (2010). The boy who was drawing princesses: Primary teachers’ accounts of children’s non-conforming behaviours. Sex Education, 10(4), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2010.515092

- Gibbons, M., & O’Shea, K. (2006). Understanding the issues: More than a phase: A resource guide for the inclusion of young lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender learners. Pobal.

- Goldstein, S. B., & Davis, D. S. (2010). Heterosexual allies: A descriptive profile. Equity & Excellence in Education, 43(4), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2010.505464

- Gowran, S. (2004). The experiences of gay and lesbian teachers in Irish schools. In J. Deegan, D. Devine, & A. Lodge (Eds.), Primary voices: Equality, diversity and childhood in Irish primary schools (pp. 37–56). Institute of Public Administration.

- Grant, R., Beasy, K., & Coleman, B. (2021). Homonormativity and celebrating diversity: Australian school staff involvement in gay-straight alliances. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(8), 960–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1592249

- Journell, W. (2017). Framing controversial identity issues in schools: The case of HB2, bathroom equity, and transgender students. Equity & Excellence in Education, 50(4), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2017.1393640

- Kitchen, J., & Bellini, C. (2012). Addressing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) issues in teacher education: Teacher candidates’ perceptions. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 58(3), 444–460. https://doi.org/10.11575/ajer.v58i3.55632

- Kosciw, J. G., & Diaz, E. M. (2006). The 2005 national school climate survey: The experiences of LGBT youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/research/2005-national-school-climate-survey

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., & Diaz, E. M. (2009). Who, what, where, when, and why: Demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 976–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9412-1

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Palmer, N. A., & Boesen, M. J. (2014). The 2013 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/research/2013-national-school-climate-survey

- Kosciw, J. G., Palmer, N. A., Kull, R. M., & Greytak, E. A. (2013). The effect of negative school climate on academic outcomes for LGBT youth and the role of in-school supports. Journal of School Violence, 12(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.732546

- Mason, E. C. M., Springer, S. I., & Pugliese, A. (2017). Staff development as a school climate intervention to support transgender and gender nonconforming students: An integrated research partnership model for school counselors and counselor educators. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2017.1380552

- Mayock, P., Kitching, K., & Morgan, M. (2007). RSE in the context of SPHE: An assessment of the challenges to full implementation of the programme in post-primary schools. Crisis Pregnancy Agency; Department of Education and Science.

- McCormack, O., & Gleeson, J. (2010). Attitudes of parents of young men towards the inclusion of sexual orientation and homophobia on the Irish post-primary curriculum. Gender and Education, 22(4), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250903474608

- McIntyre, E. (2009). Teacher discourse on lesbian, gay and bisexual pupils in Scottish schools. Educational Psychology in Practice, 25(4), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360903315115

- McNamara, G., & Norman, J. (2010). Conflicts of ethos: Issues of equity and diversity in faith-based schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(5), 534–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210373743

- Meyer, E. J. (2008). Gendered harassment in secondary schools: Understanding teachers’ (non) interventions. Gender and Education, 20(6), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802213115

- Meyer, E. J., Taylor, C., & Peter, T. (2015). Perspectives on gender and sexual diversity (GSD)-inclusive education: Comparisons between gay/lesbian/bisexual and straight educators. Sex Education, 15(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2014.979341

- Milton, J., Berne, L., Peppard, J., Patton, W., Hunt, L., & Wright, S. (2001). Teaching sexuality education in high schools: What qualities do Australian teachers value? Sex Education, 1(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810120052597

- Minton, S. J., Dahl, T., O’Moore, A. M., & Tuck, D. (2008). An exploratory survey of the experiences of homophobic bullying among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered young people in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 27(2), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323310802021961

- Neary, A. (2013). Lesbian and gay teachers’ experiences of ‘coming out’ in Irish schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(4), 583–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.722281

- Neary, A., Gray, B., & O’Sullivan, M. (2018). Lesbian, gay and bisexual teachers’ negotiations of civil partnership and schools: Ambivalent attachments to religion and secularism. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 39(3), 434–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2016.1276432

- Norman, J., & Galvin, M. (2005). A survey of teachers on homophobic bullying in Irish second-level schools. Dublin City University.

- O’Donoghue, K., & Guerin, S. (2017). Homophobic and transphobic bullying: Barriers and supports to school intervention. Sex Education, 17(2), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2016.1267003

- O’Higgins-Norman, J. (2009). Straight talking: Explorations on homosexuality and homophobia in secondary schools in Ireland. Sex Education, 9(4), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810903265295

- O’Higgins-Norman, J. (with Goldrick, M., & Harrison, K. (2010). Addressing homophobic bullying in second-level schools. The Equality Authority.

- Payne, E. C., & Smith, M. (2011). The reduction of stigma in schools: A new professional development model for empowering educators to support LGBTQ students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(2), 174–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2011.563183

- Payne, E., & Smith, M. (2014). The big freak out: Educator fear in response to the presence of transgender elementary school students. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(3), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.842430

- Pizmony Levy, O., & To Youth Services, B. (2019). The 2019 school climate survey: The experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans young people in Ireland’s schools. BeLonG To Youth Services. http://belongto.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/BeLonG-To-School-Climate-Report-2019.pdf

- Ratzinger, J. (1986). Letter to the bishops of the Catholic Church on the pastoral care of homosexual persons. Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

- Ryan, Ó. (2019, December 23). Enrolments rise in multi-denominational schools, but there’s been a very slight decrease in Catholic schools. The Journal. https://www.thejournal.ie/number-of-pupils-enrolled-in-schools-in-ireland-4946216-Dec2019/

- Smith, M. J. (2018). “I accept all students”: Tolerance discourse and LGBTQ ally work in U.S. public schools. Equity & Excellence in Education, 51(3–4), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2019.1582376

- Snapp, S. D., Burdge, H., Licona, A. C., Moody, R. L., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Students’ perspectives on LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education, 48(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2015.1025614

- Swanson, K., & Gettinger, M. (2016). Teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and supportive behaviors toward LGBT students: Relationship to Gay-Straight Alliances, antibullying policy, and teacher training. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(4), 326–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2016.1185765

- Taylor, C. G., Meyer, E. J., Peter, T., Ristock, J., Short, D., & Campbell, C. (2016). Gaps between beliefs, perceptions, and practices: The Every Teacher Project on LGBTQ-inclusive education in Canadian schools. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(1–2), 112–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2015.1087929

- Vega, S., Crawford, H. G., & Van Pelt, J. -L. (2012). Safe schools for LGBTQI students: How do teachers view their role in promoting safe schools? Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.671095

- Warner, M. (1993). Fear of a queer planet: Queer politics and social theory. University of Minnesota Press.

- Zack, J., Mannheim, A., & Alfano, M. (2010). “I didn’t know what to say?”: Four archetypal responses to homophobic rhetoric in the classroom. The High School Journal, 93(3), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1353/hsj.0.0047