ABSTRACT

The current study draws upon socialization theory to investigate both antecedents and outcomes of support service utilization within a sales employee context. Research indicates high performing, in contrast to low performing, salespeople may be more adept at discerning the ways in which an organization’s support services can be useful to them. The empirical results obtained from sales personnel of a financial services firm suggest that effective socialization/communication is important in securing an employee’s reliance upon organizational support. Further, high-performing salespeople are more proactive and instrumental in relation to utilization of support services, while low-performing salespeople are more passive and conforming in interfacing with support. Implications to both practice and research are discussed.

The effective provision of organizationally provided support services (OPS) is imperative for a high-performing organization (Halsall, Citation2014). OPS, defined as services which are specified, contracted, or mandated by the organization’s management, are meant to facilitate employee performance of a focal role. Such services may be produced and delivered by internal and/or external providers, but either way, it is the organization that is providing the structure for the support service system. For example, sales organizations may provide their salesforce with an internal support staff to set appointments, process purchase orders, and provide service follow-up to customers, thereby allowing the sales employee to focus upon his/her key performance role of selling, as opposed to devoting time to administrative tasks. Although the organization may have a clear vision of intended OPS application and subsequent benefits to the employee, employees often have reasonable freedom in the extent to which they utilize OPS and comply with OPS policies, presenting many organizations with a challenge in the implementation/consumption of OPS.

Importantly, much like a customer co-produces the value of a solution by using a firm’s product/service offering correctly, employees co-produce the value of OPS through their interaction with that OPS. Improper use of the OPS can lead to wasted resources and misplaced efforts within the organization. Yet, an organization can greatly benefit when an employee utilizes OPS, given that such support is intended to bolster employee performance, while at the same time allowing an organization to emphasize what it believes to be priorities for employee role behaviors (Braun & Hadwich, Citation2016). This research focuses upon such challenges within a sales organization context by specifically examining actions that are meant to facilitate a salesperson’s adoption of OPS.

Despite the importance of OPS, there is still a significant gap in the extant literature concerning the factors that drive the effective and efficient provision and consumption of OPS by the intended employees (Braun & Hadwich, Citation2016). This is surprising, given the enormous size and scope of such organizationally provided services. Although putting a specific dollar value on such service provision is difficult, research suggests that the effective management of such service markets and their respective costs is critical for firm success (Braun & Hadwich, Citation2016). Further, returns for firms that effectively manage the employee communications component of service support (e.g., helping employees become aware of the existence and beneficial usage of OPS) tend to outperform firms that do not (Halsall, Citation2014). Past studies by the consulting group Watson Wyatt report that companies with effective OPS communication to employees enjoy a 15.7% higher market value than companies that do not have such communication, while also delivering 29% higher shareholder return (Halsall, Citation2014). Such findings suggest the importance of communication/socialization in creating both service awareness and the effective use of OPS, which may ultimately enhance a firm’s (sales) performance.

Indeed, the importance of employee utilization of organizationally provided support services has become especially apparent in relation to sales employees. In general, salespeople have greater autonomy than most other employees, further exacerbating the concerns mentioned above regarding the potential for mis-utilization of OPS by employees. Additionally, recent research has demonstrated that the performance of salespeople is influenced by their ability to, among other factors, strategically develop and capitalize upon both internal and external support networks (Bolander et al., Citation2015; Plouffe & Barclay, Citation2007; Plouffe et al., Citation2016; Steward et al., Citation2010), suggesting the importance of a salesperson’s access and use of OPS to effectively perform his/her role. Still, understanding how to effectively use networks is distinct from understanding how to effectively use support services, which is a primary rationale for the current research.

Further complicating the issue of service consumption, it appears that not all salespeople are equally adept in determining and utilizing necessary OPS resources. Evidence suggests that high-performing sales employees understand which internal relationships (and, relatedly, forms of OPS) are most likely to help them in better serving their customers (Plouffe & Barclay, Citation2007). Certainly, from an organizational perspective, there is no value in providing support that is not adopted and utilized, or that is indiscriminately consumed by employees, given the costs associated with creating such service offerings. Given findings to suggest that high performers are better able to discern the value of OPS, we need a better understanding of how management might better align low performers with support services such that they are more inclined to utilize these resources.

Finally, an additional motivation for this study is at the heart of the execution of marketing strategy and its interface with the sales function, which has historically been ripe with challenges (Strahle et al., Citation1996). The disconnect no doubt has many components but at its core is a fundamental belief by the sales function that marketing misses the mark on what they need to attract, secure, and reinforce potential and present buyers (Malshe, Citation2010). This gap can also carry over into perceived value of training and other forms of support service (the core of our present research). How then does the firm achieve and promote a better alignment with its support for the sales function? It must be done early in the salesperson’s engagement with the firm prior to the possible exposure to negative (or, minimally, neutral) influences that may affect his/her perception of the value of firm service support. Relatedly, should the firm fail to achieve some level of sales compliance in the use of support services, the firm is unable to fully align its overall strategies (e.g., marketing, IT, finance) with securing new business, an issue that may be especially problematic if such perceptions are developed among high-performing sales employees.

With this as a precursor, in the current study, we investigate an early-stage support-service offering provided by the firm, operationalized as the development of a salesperson’s physical office and information interface services near the beginning of his/her employment with the organization. These services, if utilized by the sales employee, serve as a delivery environment for the provision of client services and are critical in the provision of training and data connectivity for the sales personnel in the firm. We examine how such a service offering may “set the stage” for how the sales employee views future organizationally provided service offerings. This, in turn, serves as an enculturation tool to subsequently influence satisfaction with the service offering and a willingness to continue the use of OPS. To orient our study, we use theories linked with employee socialization to understand the role organizational communication plays in developing employees’ enculturation to the support services provided by the organization, which results in the effective consumption of those services (Büttgen et al., Citation2012; Fonner & Timmerman, Citation2009; Lengnick-Hall et al., Citation2000)

Because of the markedly more independent role of the sales staff relative to other employees in a firm, the orientation/enculturation process(es) that is (are) part of their onboarding can play a substantive role in imprinting the sales staff with a meaningful connection to their supervisors and support role/value performed by their employing organization. Failing deliberate efforts to align the sales staff in the use of firm marketing, training, facilities, data environments, and other services, firms cannot fully benefit from the alignment of their total customer facing strategies. Lastly, many of these orientation efforts and the substance therein convey proper procedures for approaching customers and conveying the firm’s offerings. Failure to communicate and successfully secure compliance with these procedures and policies results in potentially devastating consequences, such as the continued challenges facing Wells Fargo as it addresses the unethical sales practices of many of its investment advisors.

The specific objectives of the current research are as follows: (1) to propose and test a theoretical model, based upon theories of socialization, for the effects of organizational communication on newly-hired sales employees’ consumption of OPS; and (2) to explore the differences between high- and low-performing sales employees’ interaction with such OPS, with (3) an ultimate linkage to an organizationally desired strategic behavior (i.e., an employee’s intention to continue using organizationally provided support services) and attitude (i.e. job satisfaction). This research will deepen the theoretical understanding of the much-neglected phenomenon of the salesperson interface with OPS and will help managers identify effective ways to enhance OPS utilization and employee satisfaction with such service provision.

Literature review

A body of research beginning in the 1990s addresses the means by which organizations can improve the quality of organizationally provided support services (e.g., Finn et al., Citation1996; Gremler et al., Citation1994; Reynoso & Moores, Citation1995), but in spite of more recent advances (e.g., Brandon-Jones & Silvestro, Citation2010; Nazeer et al., Citation2014), there is still a significant gap in the literature, especially in relation to the development and utilization of OPS for and by sales personnel (c.f., Braun & Hadwich, Citation2016; Stan et al., Citation2012). In order for investments in support service quality to pay off, intended users must derive value from the provided support services.

The acceptance and effective consumption of support-services is often limited, however, because potential users are unaware of support availability or do not understand the purpose and capability of given support functions (Auty & Long, Citation1999; Stauss, Citation1995). For example, employees may reject organizational support-services, such as automated customer management systems, because they do not understand the support-service role or have negative perceptions of its fit with their job (Hunter & Perreault, Citation2007; Speier & Venkatesh, Citation2002). Further problems arise with the economics of support-service provision because organizations are under continuous pressure to reduce the costs of internal operations, which often leads to downsizing support-service functions (Mills & Ungson, Citation2001). The tradeoffs between the users’ desired levels of support service and the organization’s costs of support-service delivery are likely to result in solutions that are not intended to completely satisfy all users, but instead aim to provide employees with the minimal level of resources necessary to perform their jobs (Davis, Citation1991; Hays, Citation1996). Often, however, users do not understand these tradeoffs or do not agree with management as to what constitutes an adequate level of support (Auty & Long, Citation1999; Stauss, Citation1995). Without effective communication as to the efficacy of internal support services among sales staff, the firm cedes control of its strategic deployment, service quality control, and ultimately targeted performance objectives to the judgment of sales personnel.

The anecdotal evidence in the literature suggests that management’s communication of support-service provision may be a key factor in enhancing employee understanding and consumption of support-services, which has a direct linkage with socialization theories related to firm employees (Auty & Long, Citation1999; Speier & Venkatesh, Citation2002; Stauss, Citation1995). However, even though the importance of internal communication is highly emphasized (e.g., Albrecht, Citation1990; Berry & Parasuraman, Citation1991; Groenroos, Citation1985), to date, no research addresses the specific aspects of internal communication/socialization mechanisms that impact support-service consumption, especially as it relates to initial or early-stage support-service offerings.

The current literature also is limited in helping businesses to understand the interdependence between a salesperson’s level of job performance and the consumption of support-services. In light of current research, it seems likely that sales employees proactively and selectively access the organization’s support in order to secure desired and necessary resources, and that high and low performers potentially differ in these actions (Plouffe & Barclay, Citation2007; Plouffe et al., Citation2016). For example, the academic and practitioner literature suggest that top sales employees are more successful in securing necessary support services for their customers (McAmis et al., Citation2015), and, in so doing, achieve levels of customer service provision that may bypass formal organizational policies and practices (McAmis et al., Citation2015). In spite of a lengthy focus on sales employee performance, the academic literature has only recently begun to question whether higher, as opposed to lower, performing employees tend to be more active in managing the internal organizational environment (Plouffe et al., Citation2016; Steward et al., Citation2010).

Conceptual model and hypotheses

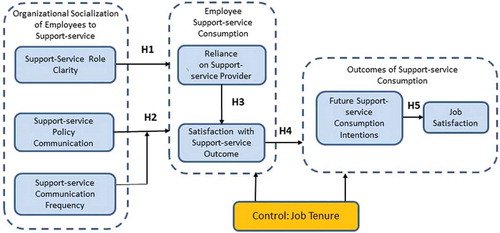

As depicted in , we propose that organizational socialization of sales employees to OPS is a key element in encouraging employees to effectively utilize OPS, which in turn is expected to result in higher levels of intentions to use support services in the future, as well as job satisfaction (see ). Organizational socialization is defined as the process by which organizational newcomers learn about and adapt to the values, norms, and favored behavior patterns in the organization (Schein, Citation1968). Extant research offers an extended view of organizational socialization as it pertains to services, including the means through which new service customers acquire knowledge, abilities, dispositions, and motivations that enable their service co-production roles and expectation of service outcomes (e.g., Büttgen et al., Citation2012; Kelley et al., Citation1990). Socialization to services takes place through organizational communication, which shapes service customers’ knowledge of the firm and its services and the firm’s expectations for the customers’ roles. This is accomplished through formal education programs, customer training, organizational literature, and other forms of communication that endeavor to educate and motivate service customers to adopt and perform the expected service co-production roles and understand and accept the service outcome (e.g., Büttgen et al., Citation2012; Fonner & Timmerman, Citation2009; Lengnick-Hall et al., Citation2000).

Employee support-service consumption

OPS is fundamentally a service created by the organization or developed in coordination with an external group and offered as an internally provided service. Although such service may be offered at a cost to internal customers (i.e., the unit consuming the product/service is charged a fee for the consumption of the service and the individual employee using the service must dedicate the time to master service use), the key is that the consumption of the service is voluntary, just as the purchase of most products or services in a market economy (Ellig, Citation2001). In such instances, given that management must logically see benefit in offering the service to the employees, it is contingent upon management to provide a convincing rationale to promote service consumption.

We propose that sales employees derive value from OPS in two ways: 1) through feelings of satisfaction with the OPS outcomes and, 2) through reliance on the OPS provider to produce the service, rather than self-production, which would direct employees’ time and effort toward nonproductive activities as opposed to value creation through customer interaction (Arndt & Harkins, Citation2013). Sales employees consume OPS for extrinsic or utilitarian goals – to facilitate their job performance and/or to achieve certain objectives in external customer exchanges. For example, a bank may provide its loan officers with a new workstation in order to facilitate their quality of service provision and/or productivity but also to impress customers and encourage them to conduct more business with the bank. Similarly, the design and execution of physical facilities, such as offices, may provide comfortable working conditions for employees but also attract and facilitate customer exchanges (Bitner, Citation1992).

As a first of two critical facets of support-service consumption, we propose that the concept of satisfaction with support-service outcome represents the extent to which sales employees are satisfied with the ability of the OPS outcomes to satisfy their needs in terms of job facilitation. This becomes a critical component to future support-service consumption. A second critical facet of OPS consumption, and a pre-cursor to satisfaction, is reliance on support-service provider for the OPS production. Services are co-produced by the customer and service provider (e.g., Mills & Morris, Citation1986). Customer co-production represents participation in support-service production by expending resources, such as information, time, and effort (cf. Silpakit & Fisk, Citation1985).

Sales employees derive efficiencies in OPS provision when they are able to limit their involvement in the OPS production and delivery, focusing instead on their customer interface roles. Certainly, some level of participation, whether by providing information or feedback or by performing certain tasks, is required for the effective provision of service, and it is often specified in the service script (Mills & Morris, Citation1986; Solomon et al., Citation1985). However, sales employees may be motivated to engage in discretionary, outside-the-script support-service production behaviors either to augment management’s mandated OPS or because they are not confident in the organization’s support-service provider to deliver the needed or desired resources. For example, the information technology literature indicates that users often get involved in developing their own computer applications because they believe they understand their needs better than the central support providers (Huarng, Citation1995). Therefore, OPS that is well-designed and delivered to satisfy the needs of the sales employee should result in limited employee participation in the service co-production. For clarity purposes, we, therefore, choose to include the concept of reliance on support-service provider, which represents the opposite of the concept of participation in service production (i.e., limited employee investment of time and effort in the service production).

The effects of organizational socialization on support-service consumption

Based upon organizational communication and socialization theories (Chao et al., Citation1994; Dubinski et al., Citation1986; Jablin, Citation1987; Katz & Kahn, Citation1966; Penley & Hawkins, Citation1985), as well as the literature on customer socialization to services (Mills & Morris, Citation1986; Solomon et al., Citation1985), we identify and define the specific facets of organizational communication that are relevant for sales employee consumption of OPS. The selection of these communication/socialization elements, as well as their relation to support-service consumption, is discussed in the development of our hypotheses.

Salesperson consumption of OPS is impacted by understanding and acceptance of the provided support. Qualitative studies indicate that effective delivery of service goals may be inhibited by users’ limited knowledge about the nature of the required services and understanding of what services they could or should be receiving from supplier departments (Auty & Long, Citation1999). This understanding and acceptance is achieved through effective socialization of employees to the support-service functions (Büttgen et al., Citation2012; Ellig, Citation2001). As such, we propose that the adoption of a given support-service is determined, at least in part, by the way in which the organization communicates the service (McAmis et al., Citation2015), as well as by the frequency of the communication (Anakwe & Greenhaus, Citation1999).

Communication of employee’s roles in OPS delivery is defined as organizational communication of behavioral expectations for the employee’s role in OPS encounters, or the extent and to which they need to participate in (or refrain from) the OPS production. Role communication is critical to support-service role clarity, which we define as the extent to which the sales employee has developed a clear definition of the role behaviors that they should play in the support-service consumption. Failure to develop such role clarity may result in behavior that interferes with service providers, to the detriment of service productivity and quality, as well as diminished satisfaction with support service outcomes (Kelley et al., Citation1990; Mills & Morris, Citation1986; Solomon et al., Citation1985).

Further, previous research on organizational socialization emphasizes the importance of familiarity in promoting desired work behaviors among employees (Burke et al., Citation2017). When role expectations are more clearly defined by the organization, the employee will be in a better position to understand the mutual benefits of engaging in organizationally desired behaviors, as well as gaining a sense that the organization has a deeper understanding of actions that support the development of both organizational and employee goals and values, which lies at the heart of socialization (Ashforth & Saks, Citation1996).

In the case of sales employee support-services, specifically, it is expected that role clarity highlights management’s expectations for personnel to rely on the organizational support-service providers and limit their own involvement in service co-production to the prescribed behaviors, thereby demonstrating an organizational value of the employee’s time and the value that can be created by the efficient usage of that time. Role clarity is beneficial in that it reflects an understanding of how individuals should adjust themselves to fit and function in relation to support service consumption (Bauer et al., Citation2007) and should link with both a reliance upon the support provider to do his/her work, as well as higher levels of satisfaction with support-service provision. That is, employees with high role clarity will have a more precise understanding of what is required to function effectively with an organization and will experience less stressful and more positive outcomes from the service interaction (Guo et al., Citation2013).

In addition, we believe sufficient evidence exists to predict potentially differential effects between high and low-performing sales personnel. According to Katz and Kahn (Citation1966), individuals are self-senders of roles based on their own needs and cognitions, not simply receivers of roles. High, versus low, performing sales employees are likely to be stronger self-senders of roles in all job-related behaviors, as well as to desire more concrete belief in the actions they should take (Plouffe & Barclay, Citation2007). As such, they are likely to benefit most from the development of role clarity, as well as work to foster a concrete understanding of desired/necessary actions and benefits. For example, according to Staw and Boettger (Citation1990), highly effective employees are likely to take charge, to engage in effortful discretionary behaviors in order to optimize role performance and enhance the probability of success and the likelihood of positive consequences. Therefore, it is expected that while more support-service role clarity will increase employee reliance on, and satisfaction with, support-service provision for all sales employees, this may be more likely for high performers than for low performers.

H1: Support-service role clarity has a positive effect on: a) employee reliance on support-service provision, and b) satisfaction with support-service outcomes. These relationships will be stronger for sales employees with high job performance versus low job performance.

Communication of OPS policies is defined as efforts to describe and explain the objectives and policies of the OPS. For example, in the case of information support systems or training programs, it is necessary to explain to employees a new computer application or a training seminar and how this new program is going to improve their job performance. This communication content is closely related to Greenbaum’s (Citation1974) informative-instructive communication network, which aids in securing all organizational goals of conformity, adaptiveness, and morale, which, also, is at the heart of organizational socialization (Ashforth & Saks, Citation1996). As such it is expected that a better understanding and acceptance of the organization’s policies with regard to the provision of support-services will positively impact both reliance and satisfaction with support-service provision through an enhanced employee understanding of how organizationally desired behaviors positively develop goals and values of the employee as a valuable component of the organizational team.

Sales personnel, with their dual advocacy to the external customer and the organization’s needs, often encounter conflicting situations (Dubinski et al., Citation1986). In these situations, employees need the support of OPS but they often complain that it does not provide them with the needed flexibility (Stauss, Citation1995). High-performing sales employees may be more reluctant to put their customer relationships at risk by relying on OPS providers for resources, even if they perceive the provider and policies are, by-and-large, user-oriented. That is, in the interest of serving their customers in an effective manner, high performers may be prone to behave contrary to organizational policy directives (McAmis et al., Citation2015). In short, high-performing salespeople may question socialization efforts that the salesperson views as being potentially in conflict with individual goals for client development (McAmis et al., Citation2015).

In addition, as Plouffe and Barclay (Citation2007) find, high-performing sales personnel are better than low performing at navigating their internal system to achieve desired outcomes, which may mean “going around” structured processes to accomplish individual goals in a manner necessary to achieve customer satisfaction. Therefore, it is expected that high performers are more tuned into the communication of support-service policies, while also being more critical and prone to modification. High performers have a better understanding of their needs and take a more utilitarian approach to their job conditions than low performers, while low performers are less discriminating OPS consumers and are more likely to simply accept policy, acquiesce and be satisfied with organizational directives. High performers may take more convincing in relation to organizational socialization than would lower-tier performers, especially when they view desired organizational behaviors as being in potential conflict with individual goals (Desmidt & Prinzie, Citation2018).

We propose, however, that these policy communication main effects will be moderated by communication frequency. A communication structure represents the format, ritual, or mannerism which communicators adopt in interaction (Sheth, Citation1976; Williams & Spiro, Citation1985). In terms of structure, it has been suggested that more frequent communication leads to more positive outcomes, such as relationship satisfaction and role/goal behavior adoption (e.g., Fisher et al., Citation1997; Mohr et al., Citation1996; Mohr & Sohi, Citation1995; Ruekert & Walker, Citation1987). As such, frequency of communication, or the repetitiveness of organizational communication to employees regarding support-service programs, is included as a communication variable in our model and is proposed, all else equal, to reinforce policy expectations sent by management to sales personnel for their participation in service co-production. Consistent with role communication, it is expected that more frequent communication about support-services will reinforce a willingness to rely on the support-service provider and conform to the expected roles, although this relationship will, as implied above, be more pronounced for lower-performing sales employees who are more likely to “buy in” to organizational communications (McAmis et al., Citation2015).

H2: Support-service policy communication has a positive effect on: a) reliance upon support-service provision, and b) satisfaction with support-service outcomes. The effect of policy communication on both c) support-service provision, and d) satisfaction with support-service outcomes will be positively moderated by communication frequency. All predicted effects will be weaker for sales employees with high job performance versus low job performance.

Although sales employee involvement in the support-service production would run counter to organizational goals for the employee, it is logical that salespeople who get involved in the process will actually be more satisfied with the outcomes. Employee involvement will promote the creation of service outcomes consistent with their desires, in spite of what may have prompted a higher level of involvement (e.g., poor support-service provider performance). It is likely that salespeople who perceive a high level of support-service performance quality are less likely to participate in the service production. Rather, it is when problems arise in the service performance that sales employees decide to get involved. Research on service participation found that customers who have higher levels of participation in the service production are more likely to be satisfied with the service outcome (Bateson, Citation1985). These customers are more likely to develop realistic expectations and make more realistic attributions, and above all, they can better guide the service production toward desired outcomes (Bateson, Citation1985; Silpakit & Fisk, Citation1985).

We propose that high performers will be more likely to desire involvement in support-service creation, given their ability to more clearly focus on what will be useful for them to achieve desired performance levels (Plouffe et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, low-level performers would be more likely to follow organizational directives and allow support-service providers to follow the path most closely aligned with organizational protocols (McAmis et al., Citation2015). This would potentially weaken the support service delivery process and satisfaction with outcomes of OPS, as employee participation would be low.

H3: Employee reliance on the support-service provider has a negative effect on satisfaction with support-service outcome. This relationship will be stronger for sales employees with high job performance versus low job performance.

The outcomes of support-service consumption

Concerning general job outcomes, such as job satisfaction, the literature provides increasing evidence for the positive relationship between an employee’s satisfaction with support-service outcomes, future support-service consumption intentions and job satisfaction. For example, it is argued that employees’ satisfaction with the firm is influenced by service encounters with internal service providers (Berry & Parasuraman, Citation1991; George, Citation1990; Groenroos, Citation1985). Further, if relationships between the employee and providers of support-service are not effectively managed, service gaps may result that have implications on external service quality (Lewis & Entwistle, Citation1990). Bitner (Citation1995) indicates that organizational support provided to employees enables these employees to keep promises made to external customers. In order for employees to deliver on the promises made, they must have needed skills and abilities and be provided with appropriate service systems and processes (Kingman-Brundage, Citation1989; Shostack, Citation1987). Heskett et al. (Citation1994) suggest that quality of work environment contributes most to employee satisfaction. Employees put high value on their ability to achieve results for customers, which is complemented by satisfaction with support-services. In addition, Sergeant and Frenkel (Citation2000) and Hallowell et al. (Citation1996) find that the quality of support provided by the organization has a significant impact on an employee’s job satisfaction and service capability. Finally, in relation to the provision of OPS, certainly an overarching goal would be to enable employees to more effectively serve customers (Ellig, Citation2001), which would be consistent with effective socialization to organizational goals and values among customer-focused firms (Ashforth & Saks, Citation1996).

Hence, our research proposes a positive relationship between employee satisfaction with support-service outcomes, future support-service consumption intentions, and job satisfaction. Conceptually, job satisfaction is defined as an employee’s overall level of satisfaction, excitement, and sense of worth received from his/her job (Brown & Peterson, Citation1994). Future support-service consumption intentions are, simply, employees’ willingness to share positive word-of-mouth regarding support-services, as well as intentions to use organizationally provided support-services in the future, showing a desire to forge stronger bonds with the service providers (Zeithaml et al., Citation1996).

H4: Employee satisfaction with support-service outcomes has a positive effect on: a) future support-service consumption intentions, and b) job satisfaction.

Similarly, research related to job demands-resources theory (c.f., Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007) suggests that employee perceptions of reliable and beneficial organizational resources will promote both job engagement and employee satisfaction. In this regard, working for an organization that provides suitable support-service options will promote employee satisfaction with the job. This, also, is consistent with research related to socialization, which suggests that employees who have been effectively socialized to an organization are much more likely to engage in positive work-related behaviors, as well as enjoy satisfaction with their work environment and the roles that they play in an organization (Burke et al., Citation2017).

This leads to our final hypothesis:

H5: Employee future support-service consumption intentions has a positive effect on employee job satisfaction.

Research method

Support-service context

In order to gain access to an organization with a large number of sales personnel, as well as monitor support service provision and consumption, we sought the cooperation of a large personal financial investments firm that employs more than 6,000 salespeople (all compensated by full commission). Each salesperson, called an investment representative, works in an independent office located in a residential area with offices spread throughout the US. The firm provides a wide portfolio of financial products and full services to consumers who are interested in high quality, long-term relationships with financial investment reps. The firm is ranked as one of the top organizations for which to work, due in large part to the quality and range of support-services provided, such as market research, information technology support, and office facility support.

The sales deployment strategy of this firm is not unlike others in its and similar industries. Some sales organizations that provide services such as financial services, insurance, and real estate agencies have traditionally sought to reach out to the marketplace with multiple outlets convenient for customer access. Firms either contract, franchise, or own these entities and give considerable attention to optimal locations, layouts, signage, and other details. The challenge in aligning the sales staff with these facilities (prior to location selection and construction) is the extent of sales staff engagement to encourage buy-in (ownership) while not being a distraction from the selling effort. Tens of thousands of these types of locations populate the US and international markets. How best to engage sales staff to assure their satisfaction and use of these facilities while not serving as too great of an early career distraction from the sales staff’s fundamental role in securing customers is important to the success of many firms that deploy their sales staff with this location strategy.

It is within this type of sales deployment setting where we conduct our study, focusing on the firm’s provision of facility support-services. After completion of training and passing certain performance standards, the firm provides salespeople, free of charge, an office and data/training services that are linked via satellite. This office serves as the salesperson’s official business location. The new office opening/data support installation process, which lasts several months, is the first experience that salespeople have with the firm’s facility and data installation support-services – hence, the experience is critical for the organization to develop a positive perception of organizationally provided support-service. The facility/data linkage support function, located within the firm’s headquarters, is responsible for prospecting the market, finding an appropriate new office location, building or remodeling, furnishing, and providing signage for the office, installing satellite systems, and negotiating the lease. Extensive interviews with management, facility support personnel, and salespeople indicated that salespeople’s satisfaction with and acceptance of their new office is an important factor in their career.

The context provided by this firm and its facility/data linkage support of salespeople offers several advantages for our research objectives. First, the context provides large variability in employee’s interaction with the OPS, due to the fact that salespeople work in independent, geographically dispersed offices, served by different service contractors. Second, while limiting the empirical study to one context may reduce the generalizability of the findings, it helps control confounding industry and organizational-specific factors and improves the quality and specificity of the measurement instrument. Third, since the firm is already one of the best in the industry in providing high-quality support, further OPS quality enhancement is less important than effective organizational communication in securing employee satisfaction with the OPS in the early stage of one’s career. Finally, the OPS investigated in this study is a significant job resource as the training and data linkages utilized by the sales staff in this firm are among the leading-edge financial training, analytics, and projection tools available among competitors in the marketplace. Installation of the office is imperative to assure effective access to these resources, many of which are only available through the firm’s satellite linkage system.

Sample and data collection

The firm identified 1524 salespeople for whom a new office had been opened within the previous 3 years. A survey packet was sent to the office of each salesperson, including a survey questionnaire, a cover letter from the researchers, an endorsement letter from the firm’s management and a postage-paid return envelope addressed to the researchers. Altogether, 1057 completed questionnaires were returned, 727 in response to the first mailing (47.7%), and an additional 330 in response to the follow-up mailing, which was sent out 3 weeks later, for a total response rate of 69.4%. Sixty-eight questionnaires were discarded because of missing data, leaving a usable dataset of 989 (65%). The firm provided information concerning the length of employment time and salesperson’s overall job performance, as rated by the firm. This information was matched with the primary data collected by the survey. We used the data obtained from the 167 salespeople who had been in their offices for more than 24 months as a hold-out sample for measurement purification. The final sample used for hypothesis testing contained data only from salespeople who had opened offices within the previous 2 years (subsequent analyses failed to identify any significant differences based on length of time).

The 822 salespeople in the final sample were 83% male, 89% with an age between 26 and 55 years, had an average experience in selling of 7.3 years (51% 3 years or less and 25% 10 years or more), worked for the participating organization for an average of 18 months and had been in their office for an average of 12 months. The sample captured 465 (55%) salespeople with good overall job performance, as reported by the firm. These salespeople had a composite job performance index, as computed by the firm, above the firm’s standard for acceptable performance, with the rest falling below the firm’s standard and therefore being classified as marginal or poor performers. The characteristics and job performance ratings of the final sample matched closely those of the firm’s salesforce.

Measures

The constructs used to test our hypotheses were all measured with multiple-item, seven-point scales (see for a listing of scale items). All measures initially suggested for this study were assessed for content validity by a panel of three salespeople and three sales managers from the focal firm. Five constructs in our model were measured with scales adapted from existing research. For job satisfaction, we used four items from the scale used by Brown and Peterson (Citation1994). Future OPS consumption intentions, representing salespeople’s intention to forge future bonds with the OPS providers, was measured using five items adapted from Zeithaml et al.’s (Citation1996) scales for positive WOM and future usage intentions. For Support-service role clarity we used five items from the Rizzo et al. (Citation1970) scale for role ambiguity, adapted to fit the research context, and for communication frequency, three items were adapted from Mohr et al. (Citation1996).

Table 1. Measurement model

The other constructs utilized in the current research were generated through both previous literature (Hartwick & Barki, Citation1994; Holbrook, Citation1994), as well as interviews of sales employees not taking part in the survey. In relation to these interviews, three salespeople and two sales managers were interviewed both in-person (salespeople) and via telephone (sales managers). The interviews were depth-interviews, with each lasting nearly 1 h. Questions related to their job, their office, the facility support service, and their perceptions of the company and, for salespeople, the sales manager were asked. The focus for each interview was upon not only gaining a better understanding of the context and the appropriateness of our potential model, but also toward understanding how to best word the items we would use to measure our construct for which a suitable measure could not be found in the literature (i.e., communication of support-service policies).

Measures were pretested in a hold-out sample from the same focal company of the primary data collection. The measure for reliance on support-service provider was developed based upon Hartwick and Barki’s (Citation1994) operationalization of service participation along three dimensions: leadership or supervision of service provision, communication with service provider, and hands-on work, or actual execution. Each of the three dimensions was measured with two items referring to the two principal aspects of the OPS investigated: office location and construction. The scale was reversed to capture reliance on service provider, rather than extent of participation in service provision. Satisfaction with support-service outcome was derived from the theoretical work of Holbrook (Citation1994) and intended to measure the service recipient’s assessment of the extent to which the service outcome satisfies job-related needs. The measure, consisting of four items, captures satisfaction with the extent to which the office meets the salesperson and their clients’ needs. Finally, in the absence of a suitable existing measure, we developed a new scale to assess the company’s communication of support-service policies, to assess the communication the salesperson received from the organization’s management about the objectives, rationale, and specifications for the support-service being provided. The control variable job tenure, was measured in number of months in a sales position with the firm and it ranges from one to 24 months.

Data analysis

We employed latent variable structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS to assess both the measurement and structural model. This is considered an appropriate technique for model building because it permits the simultaneous estimation of multiple and interrelated dependence relationships (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) while also accounting for measurement error in the estimation process (Hair et al., Citation1998). To assess the measurement properties, items were subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis which indicated a good fit for all measures. reports factor loadings, average variance extracted and composite reliability for all construct scales along with measurement model fit indices within the recommended ranges, suggesting adequate discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). In addition, the Cronbach alpha reliability indices of the scales, reported in , provide further proof for adequacy of the measurement model Correlation coefficients in represent the correlations among the latent variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, cronbach reliability, and correlations

Further, we tested the full structural model on the entire sample of 822 respondents. We allowed paths for all the hypothesized effects between the listed independent variables and dependent variables and the effects of the control variable, job tenure, on all dependent variables. Based on the fit statistics for the entire SEM model, we allowed two additional direct paths from role clarity and communication of support-service policy to future OPS consumption intentions. The resulting model fit statistics are strong, with CMIN/df = 3.8; CFI =.94; RMSEA = .059 for the all employee model. reports the standardized estimates, t-values, and level of significance for all the hypothesized relationships. In addition, reports the results of a two-group comparison analysis in which the same SEM model was estimated on a group of 289 high performers and a group of 278 low performers. These two groups were created based on a ranking of all subjects on the company reported performance index, where we selected the top and bottom terciles (we eliminated the middle tercile in order to better emphasize differences). As reported, the two-group model fit statistics are also strong, with CMIN/df = 2.2; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .046. Finally, for clarification purposes, the significant path coefficients for the all-employee tested model are depicted in .

Table 3. Structural equations model results

Results

The results, as shown in , indicate support for H1. Support-service role clarity has a strong positive effect on sales employees’ reliance on the support-service provider and on their satisfaction with the OPS outcome (p < .01); these effects are only marginally stronger for high versus low performers (difference not significant). H2 states that the company’s efforts to communicate OPS policies to sales employees will have a positive effect on both their reliance on OPS providers and satisfaction with OPS outcomes, which will be moderated by communication frequency. Interestingly, the results show an overall negative effect of this form of socialization on employees’ reliance on the OPS provider. It seems that the more communication employees receive about OPS policies, and with higher frequency of communication, the less reliance on OPS they display (H2a and H2c not supported). However, a closer look at the effects of the interaction between OPS policy communication and frequency of communication and on the differences between high and low performers provides additional insight. For high performers, a simple slope analysis of the interaction effects shows that OPS policy communication has a strong negative effect on reliance on the OPS provider only when communication frequency is high (p < .01), but no significant effects under low frequency of communication. For low performers, only communication frequency has a negative effect on reliance on OPS provider, but not communication of OPS policy.

As predicted in H2b, communication of OPS policy has a positive effect on satisfaction with OPS outcome, which indeed is stronger for the low performers (p < .01) while marginal for the high performers. Communication frequency has a marginal direct and no interactive effect on satisfaction with OPS outcome (H2d not supported). It is possible that communication frequency is associated with the occurrence of problems in the OPS delivery process that require employees to participate more in the service delivery process to help resolve those problems. If so, it is interesting to see that while low performers apparently adjust behavior simply in response to the firm’s increased communication, high performers’ response is to reduce their reliance on OPS providers and increase their participation, which may be in response to perceived deficiencies in the OPS delivery process and policies. Therefore, it seems that while low performers display a passive, submissive attitude to the company’s socialization efforts, high performers accept those socialization efforts in a more discerning way, displaying a more proactive participation in the OPS delivery process upon recognizing deficiencies in organizationally provided support.

This interpretation seems to gain further support from the test of H3, which shows that employees who participate more in the OPS delivery, i.e., display less reliance on OPS provider, end up more satisfied with the OPS outcomes. However, this effect is strongly significant for the high performance group (p < .01), but not significant for the low performance group (H3 supported). It may be that low performers have a less informed perspective as to how to consume OPS to optimize their performance. Hence, low performers may activate OPS participation without the benefit of being an informed consumer and with the possibility of greater distraction from service coproduction, thus diverting attention from client development and sales. High-performing employees’ participation in OPS provision, on the other hand, may be instrumental in garnering more resources for themselves and therefore higher satisfaction with OPS outcomes. In this case, through higher levels of self-production, high performers succeed in gaining better located, designed, and connected offices from where they conduct their business.

Further, as shown in , H4aFootnote1 receives strong support (p < .01), showing that employee satisfaction with OPS outcomes is an important determinant of future OPS consumption intentions; therefore, showing employees’ intentions to forge stronger bonds with the company’s support service providers, a critical factor in the overall success of the organization’s support service network. Here it is important to note that in addition to the indirect effects of the organizational socialization efforts, the SEM model with the best fit shows significant additional direct effects: OPS role clarity and communication of OPS policies have a direct positive effect on employees’ future consumption intentions. This provides added support for the importance of the company’s socialization efforts in securing the successful consumption of support services by its employees.

While satisfaction with OPS outcome is only a component of the scope of employees’ jobs, it has a significant relationship with employees’ job satisfaction (H4b supported, p < .01). This finding is consistent with the tenet that companies who satisfy their employees as internal customers are more likely, in turn, to find they engage in behaviors that satisfy their external customers. Further, H5 is supported in that employees’ future OPS consumption intentions have a positive effect on job satisfaction (p < .01). It seems that the organization’s effective performance of the support-service function, to the point of employees being moved to endorse such a service and intention to forge stronger bonds with the OPS providers, creates a strong sense of satisfaction for employees. Such success may reinforce the employee’s perception that s/he is working for a reliable organization.

Discussion

The extant literature provides limited direction for management in the development of support-service consumption strategies among organizational personnel. This is especially true as it relates to offering support services early in a sales employee’s tenure (enculturation) with an organization. The current research examines the influence of organizational socialization efforts, in varied forms, as a tool to enculturate sales employees toward a given support-service offering, with the hope of developing a higher level of actual consumption by employees of the provided support services, which would result in a positive job outcome (job satisfaction). In addition, building upon current research into the differential reactions of high- and low-performing sales personnel (c.f., Plouffe et al., Citation2016), the key socialization effects are all investigated relative to the performance level of an individual employee.

In total, we find that the organization’s efforts to socialize employees to OPS through internal communication, a much-neglected factor, appear to be an important precursor to an employee’s support-service consumption, and that significant differences do exist between high- and low-performing sales employees. Given the fact that costly organizational initiatives for providing sales support are often unsuccessful because of employee indifference or rejection of the support (e.g., Speier & Venkatesh, Citation2002), management’s ability to effectively employ and manage communication channels with employees is a very important and cost-efficient factor in enhancing the success of the provided support. Such communication is likely to help employees better value and exploit the resources provided by OPS and reduce service delivery gaps, for example, between expectations and specifications, inherent in any service exchange (e.g., Auty & Long, Citation1999). The current research suggests that socialization through communication plays an important role in this process and should not be overlooked.

It appears high performers, in contrast to low performers, are more pro-active and instrumental in their interactions with providers during the process of OPS delivery, and in their effort to close perceived gaps in the OPS policies established by the organization’s management through self-production. High performers, versus low performers, appear to react positively to organizational communication targeted to increase role clarity, which shows a desire for confidence in management’s ability to create a positive support-service environment where employee time and effort might be minimized in the development of the support service (allowing more selling time). However, these same top performers, versus lower performers, tend to respond to high frequency of communication of OPS policies with increased self-production of OPS, displaying less reliance on OPS providers (a downside from an organizational perspective), which in turn, though, results in higher satisfaction with OPS outcomes. This shows a tendency of high versus low performers to both acquiesce to company policies in a desire to save time and effort for productive job-oriented tasks (selling) and to defy those policies when they see an opportunity to enhance the support-service, and thus garner more resources for their core job tasks.

Perhaps this engagement may also be tied to a long-term focus upon beneficial customer outcomes believed to result from OPS involved activity (most likely borne from past experiences). This is less of an issue with low-performing employees, who display a tendency to simply accept the company OPS policies and comply with the support received, while reacting only in response to potential problems that appear in the support-service delivery process. Lower performers, being less sophisticated in their OPS consumption (certainly less selective), may fail to nuance the firm-provided support service to best fit their sales situations and/or their style. Therefore, the findings suggest something of a double-edged sword for management in that management must be clear in coordinating efforts with high-performing sales employees to help develop roles that will truly keep them selling during the provision of support services, while also suggesting that high-performing employees may be able to better recognize when their own initiative is necessary as an investment in long-term performance. In the case of low-performing salespeople, they appear to be more prone to accept the OPS as provided.

Finally, it is important to note that satisfaction with OPS outcomes plays a critical role in the development of organizationally desired outcomes. Employees satisfied with support-service provision, whether high or low performers, are more likely to share positive feelings about support services and have a higher tendency to develop bonds with support-service suppliers. They tend to display higher levels of future OPS consumption intentions, as well as greater job satisfaction. Therefore, the evidence would suggest it is important to achieve high levels of support-service satisfaction with employees, illustrating the overall importance of properly managing such organizationally provided service options.

Managerial implications

Managers should recognize the importance of internal communication in order to inform employees about support-service availability, capabilities and access policies, and to clarify the rationale for service provision and the benefits that may be derived from consuming the service. An important concern is to ensure that formal messages about support-services transmitted by top management are consistent with often informal communication that employees receive from support-service providers, local managers, and other, veteran employees, who play roles of enculturation/socialization agents. Often, negative perceptions of new, central support-service initiatives result from local branches’ belief that central management and support-service providers do not fully understand local conditions under which frontline personnel operate. It is critical to ensure that support-service providers have a genuine user orientation, which is, in turn successfully conveyed to users (employees). This may be especially important when organizations outsource such functions to outside providers and is certainly critical in relation to high performers.

Managers should direct attention to the fine balance between encouraging proactive involvement in support-service provision and encouraging compliance and reliance on service providers. On the one hand, it is necessary to manage high performer’s involvement through clear communication of OPS policies consistent with what a high performer would envision (which appears evident from their tendency to engage in OPS participation). It is through effective management of this communication function that reliance on support-service providers can be more likely influenced through the development of positive word-of-mouth emanating from performance leaders. At the same time, managers should be aware of the limited effectiveness of repeated communications regarding support-service to high performers, as this tends to be ineffective. Also, the results provide managerial guidance in highlighting the potential of directing action in a more efficient manner through the communication of clear roles in the service provision process.

In relation to low-performing employees, it may be that the reality for management is that they appear to have a receptive audience to OPS adoption and consumption. That said, their receptivity does not appear to be linked with superior performance. What, then, can management do to help them consume OPS such that it may better facilitate improved performance? While the results of this study do not specifically address this issue, there are a few possible suggestions based on the evidence regarding top performers. Rote adoption of sales support services hardly makes for a meaningful connection to an individual salesperson’s style and/or sales context. Effective adoption appears to be tied to suiting the nuance of their personality and approach. Possibly a better deployment of OPS among low-performing salespeople is to use simulations to help them see how these services best fit the demands of their sales context.

Marketing/service strategies more often than not depend on conformance of sales personnel particularly when, as is often the case, these staff are to utilize support services vital to their differential advantage in the provision of a superior value propositions to their customers. Customer expectations about receiving the full array of services of these boundary spanners is formed by the firm’s and/or competitor’s marketing communications. These customer service expectations, and the probability that the anticipated value proposition is met, can only be sated by properly trained and supported boundary spanning staff. High variance among salespeople in their support service utilization creates unevenness in service delivery to the firm’s customers. Without proper management of support service consumption, it is challenging to effectively assess the execution of marketing/service strategies not to mention individual performance anomalies. Increasingly differential advantage in many markets is difficult to come by with execution of many of these sustainable advantages falling upon salespeople who are often called upon to secure and maintain these profitable customer relationships.

Limitations and future research

Future research might seek to replicate this study in other support-service contexts, such as information technology (e.g., implementation of automated service systems), training, or other technical support provided to generalized frontline personnel. While each support context poses the same problems associated with the internal communication of resource provision and employee acceptance of those resources, as investigated here, there may be sufficient differences due to structural (industry and organization specific) factors that warrant investigations across multiple service contexts.

Further, OPS that provides boundary spanners significant differential advantages in servicing customers, such as advanced analytics or expedited logistics, are frequently used to elevate the competitive advantage for the employee, and they serve as important employee retention tools (as these services may not be replicated at similar levels among the competitors). How sales employees differentiate among OPS and assign greater or lesser criticality to their value added as a consumer of these services would be an excellent next step. Possibly a taxonomy of OPS might be created and, with it, alternative models for how best to secure engagement by employees. This may be particularly true for lower-performing sales staff where scenarios/simulations of various manipulations may enlighten our understanding of how best to assist them in their acceptance of these services and their deployment within their sales role.

Further, future research should link the concept of service climate with the communication/socialization mechanism presented here and investigate the implications for other frontline employees, beyond sales, who rely on organizational support to achieve effective exchanges with their customers (e.g., Evans et al., Citation1999; Hartline & Ferrell, Citation1996). These positions tend to be more salary as opposed to commission compensated and therefore are more prone to behavioral controls. The implications of support-services provision and consumption in front line employees’ effort to meet customer satisfaction versus organizational efficiency and productivity demands, which is mainly a return-on-investment problem, should also be investigated.

Finally, a number of methodology-related research opportunities are also evident. The findings of this study may be affected by common-method variance. As is almost always present in survey research, issues of endogeneity may exist. That is, in some cases, it may be possible that the observed effects go in both directions. For example, it was argued that effective communication of support-service goals would influence reliance upon support-service provision. However, it may be possible that employees who rely upon support-service providers then “discover” the desired outcomes, as putting the goals into action may illuminate the organizational objectives. Future studies might seek to employ longitudinal data collections, following the support-service production and delivery process, or simulations techniques that permit the manipulations of the independent constructs in the theoretical framework we advanced.

Notes

1 While not hypothesized, a post hoc two-group analysis shows no significant differences between high and low performers. Therefore, results related to hypotheses 4 and 5 are reported for the entire data set.

References

- Albrecht, K. (1990). Service within. Dow Jones-Irwin.

- Anakwe, U. P., & Greenhaus, J. H. (1999). Effective socialization of employees: Socialization content perspective. Journal of Managerial Issues, 11(3), 315–329.

- Arndt, A. D., & Harkins, J. (2013). A framework for configuring sales support structure. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 28(5), 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858621311330272

- Ashforth, B. K., & Saks, A. M. (1996). Socialization tactics: Longitudinal effects on newcomer adjustment. Academy of Management Journal, 39(1), 149–178. http://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/256634

- Auty, S., & Long, G. (1999). Tribal warfare and gaps affecting internal service quality. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 10(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239910255352

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bateson, J. E. (1985). Self-service consumer: An exploratory study. Journal of Retailing, 61(3), 49–76.

- Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.707

- Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1991). Marketing services. Competing through quality. The Free Press.

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600205

- Bitner, M. J. (1995). Building service relationships: It’s all about promises. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 246–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207039502300403

- Bolander, W., Satornino, C. B., Hughes, D. E., & Ferris, G. R. (2015, November). Social networks within sales organizations: Their development and importance for salesperson performance. Journal of Marketing, 79(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.14.0444

- Brandon-Jones, A., & Silvestro, R. (2010). Measuring internal service quality: Comparing the gap-based and perceptions-only approaches. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 30(12), 1291–1318. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571011094271

- Braun, C., & Hadwich, K. (2016). Complexity of internal services: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3508–3522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.035

- Brown, S. P., & Peterson, R. A. (1994, April). The effect of effort on sales performance and job satisfaction. The Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800206

- Burke, T. J., Dailey, S. L., & Zhu, Y. (2017). Let’s work out: Communication in workplace wellness programs. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 10(2), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-07-2016-0055

- Büttgen, M., Schumann, J. H., & Ates, Z. (2012). Service locus of control and customer coproduction. Journal of Service Research, 15(2), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511435564

- Chao, G. T., O’Leary-Kelley, A. M., Wolf, S., Klein, H. J., & Gardner, P. D. (1994). Organizational socialization: Its content and consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(5), 730–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.5.730

- Davis, T. R. V. (1991). Internal service operations: Strategies for increasing their effectiveness and controlling their costs. Organizational Dynamics, 20(2), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(91)90068-K

- Desmidt, S., & Prinzie, A. (2018). Establishing a mission-based culture: Analyzing the relationship between intra-organizational socialization agents, mission valence, public service motivation, goal clarity and work impact. International Public Management Journal, 22(4), 664–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2018.1428253

- Dubinski, A. J., Howell, R. D., Ingram, T. N., & Bellenger, D. N. (1986, October). Salesforce socialization. Journal of Marketing, 50(4), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298605000405

- Ellig, J. (2001). Internal markets and the theory of the firm. Managerial and Decision Economics, 22(4–5), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.1013

- Evans, K. R., Arnold, T. J., & Grant, J. A. (1999). Combining service and sales at the point of customer contact. Journal of Service Research, 2(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467059921004

- Finn, D. W., Baker, J., Marshall, G. W., & Anderson, R. (1996). Total quality management and internal customers: Measuring internal service quality. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 4(3), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.1996.11501731

- Fisher, R. J., Maltz, E., & Javorski, B. J. (1997, July). Enhancing communication between marketing and engineering: The moderating role of relative functional identification. Journal of Marketing, 61(3), 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100304

- Fonner, K. L., & Timmerman, C. E. (2009, November). Organizational New c(ust)omers: applying organizational newcomer assimilation concepts to customer information seeking and service outcomes. Management Communication Quarterly, 23(2), 244–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318909341411

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981, February). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- George, W. (1990). Internal marketing and organizational behavior: A partnership in developing customer-conscious employees at every level. Journal of Business Research, 20(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(90)90043-D

- Greenbaum, H. H. (1974). The audit of organizational communication. Academy of Management Journal, 17(1), 739–754. http://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/ambpp.1974.17531485

- Gremler, D. D., Bitner, M. J., & Evans, K. R. (1994). The internal service encounter. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5(2), 34–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239410057672

- Groenroos, C. (1985). Internal marketing: Theory and practice. In T. Bloch, G. Upah, & V. Zeithaml (Eds.), Services marketing in a changing environment (pp. 41–47). American Marketing Association.

- Guo, L., Arnould, E. J., Gruen, T. W., & Tang, C. (2013). Socializing to co-produce pathways to consumers’ financial well-being. Journal of Service Research, 16(4), 549–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670513483904

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Jr., Tatham, R. L., & William, C. B. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Hallowell, R., Schlesinger, L. A., & Zornitsky, J. J. (1996). Internal service quality, customer and job satisfaction: Linkages and implications for management. Human Resource Planning, 19(2), 20–31.

- Halsall, A. (2014, November 10). Why internal matters. Digitalist Magazine: SAP. www.digitalistmag.com

- Hartline, M. D., & Ferrell, O. C. (1996, October). The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 52–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251901

- Hartwick, J., & Barki, H. (1994). Explaining the role of user participation in information system use. Management Science, 40(4), 440–465. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.40.4.440

- Hays, R. D. (1996, July–August 15–20). The strategic power of internal service excellence. Business-Horizons.

- Heskett, J. L., Jones, T. O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, E. W., Jr., & Schlesinger, L. A. (1994, March–April). Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 164–174.

- Holbrook, M. B. (1994). The nature of customer value. An axiology of services in the consumption experience. In R. T. Rust & R. L. Oliver (Eds.), Service quality. New directions in theory and practice(pp. 21–71). SAGE Publications.

- Huarng, A. S. (1995). System development effectiveness: An agency theory perspective. Information & Management, 28(5), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-7206(94)00051-J

- Hunter, G. K., & Perreault, W. D. (2007). Making sales technology effective. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.1.016

- Jablin, F. M. (1987). Organizational entry, assimilation and exit. In F. M. Jablin, L. L. Putnam, K. H. Roberts, & L. W. Porter (Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication(pp. 732–818). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1966). The social psychology of organizations. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Kelley, S. W., Donnelly, J. H., Jr., & Skinner, S. J. (1990). Customer participation in service production and delivery. Journal of Retailing, 66(3), 315–335.

- Kingman-Brundage, J. (1989). Blueprinting for the bottom line. In Service excellence: marketing’s impact on performance(pp. 21–33). American Marketing Association.

- Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Claycomb, V., & Inks, L. W. (2000). From recipient to contributor: Examining customer roles and experienced outcomes. European Journal of Marketing, 34(3/4), 359–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560010311902

- Lewis, B. R., & Entwistle, T. W. (1990). Managing the service encounter: A focus on the employee. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 1(3), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239010001136

- Malshe, A. (2010). How is marketers’ credibility construed within the sales-marketing interface? Journal of Business Research, 63(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.01.004

- McAmis, G., Evans, K. R., & Arnold, T. J. (2015). Salesperson directive modification intention: A conceptualization and empirical validation. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 35(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2015.1037308

- Mills, P. K., & Morris, J. M. (1986). Clients as ‘partial’ employees of service organizations: Role development in client participation. Academy of Management Review, 11(4), 726–735. http://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/amr.1986.4283916

- Mills, P. K., & Ungson, G. R. (2001). Internal market structures; substitutes for hierarchies. Journal of Service Research, 3(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050133006

- Mohr, J. J., Fisher, R. J., & Nevin, J. R. (1996, July). Collaborative communication in interfirm relationships: Moderating effects of integration and control. Journal of Marketing, 60(3), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000307

- Mohr, J. J., & Sohi, R. S. (1995). Communication flows in distribution channels: Impact on assessments of communication quality and satisfaction. Journal of Retailing, 71(4), 393–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4359(95)90020-9

- Nazeer, S., Zahid, M. M., & Malik, F. A. (2014). Internal service quality and job performance: Does job satisfaction mediate? Journal of Human Resources, 2(1), 41–65.

- Penley, L. E., & Hawkins, B. (1985). Studying interpersonal communication in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 28(2), 309–326. http://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/256203

- Plouffe, C. R., & Barclay, D. W. (2007). Salesperson navigation: The intraorganizational dimension of the sales role. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(4), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2006.02.002

- Plouffe, C. R., Bolander, W., Cote, J. A., & Hochstein, B. (2016). Does the customer matter most? Exploring strategic frontline employees’ influence of customers, the internal business team, and external business partners. Journal of Marketing, 80(1), 106–123. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.14.0192