ABSTRACT

Fashion retailers, marketers, and app designers must captivate their dominant consumers: Generation-y women. Nevertheless, existing research and design practice is grounded in older apps and older generations: Generation-x. Through 27 semi-structured interviews, we define generation-y’s unique interaction with – and perception of – fashion m-commerce to enhance fashion retailers’ ability to design apps targeted at their dominant consumers. We prove that efficiency and convenience drive app engagement, official marketing social media is more effective than friend’s social media posts, and interactive design features are irrelevant in purchase motivation. We finish by communicating our findings through six design recommendations, subdivided by market sector.

Introduction

Retailers, marketers, and designers attempt to captivate consumers through functional and seductive electronic commerce (e-commerce) platforms. For fashion retail, generation-y women – women born between 1982 and 2000 (US Census Bureau, Citation2015) – are the dominant e-commerce consumers (ONS, Citation2019; Soares et al., Citation2017). E-commerce has, in recent years, become essential, with sales increasing by 98.5% since 2014, generating over £77.4 billion per year (Carroll, Citation2019). This growth is hastening. In COVID-19’s wake, fashion retailers are accelerating their shift to e-commerce and consolidating physical space as costs increase, consumers reduce spending, and retailers enter bankruptcy (Carroll, Citation2020). Consumers were spending less on fashion. Fashion retail’s future, therefore, depends on designing effective e-commerce platforms that captivate its most lucrative customers – generation-y women – with physical retail’s seduction. Nevertheless, research and best practice based on older generation-x adults – or outdated retail practices – guides the app design process.

Generational cohorts – including generations-x and y – offer a better prediction of consumer interaction and motivation than other demographics – such as age or gender (Eastman & Liu, Citation2012; Parment, Citation2013). Twenge et al. (Citation2010, p. 1120) explain this difference as “each generation is influenced by broad forces … that create common value systems distinguishing them from people who grew up at different times.” Understanding a generation’s unique value system allows retailers, marketers, and app designers to target their retail platforms using app design features that appeal to the consumers’ motivations and ways of interacting. We must, therefore, augment the extent knowledge of generation-x’s value systems with generation-y’s.

Marketers and designers direct e-commerce app engagement through their customer’s cognitive motivations, including attitudes toward shopping and motivations to engage with fashion retail (C. Parker, Citation2018; Zhao & Balagué, Citation2015). Nevertheless, the extant literature on applying cognitive motivation to fashion retail apps – grounded in generation-x’s retail marketing – is slow to respond to generation-y’s unique value systems (Zhao & Balagué, Citation2015). The literature’s focus on generation-x – people born between 1965 and 1981 (Winograd & Hais, Citation2014) – is concerning. Generation-x’s attitudes and motivations toward fashion purchases differ from generation-y’s. Generation-y is, compared to generation-x, more service orientated, more assertive to complain about poor service quality (Soares et al., Citation2017), and more loyal to brands that align with their lifestyle ideals (Bento et al., Citation2018). Generation-y consumers prefer acquiring hedonic experiences over physical goods (Brown & Lubelczyk, Citation2018), a factor previous generation-x research overlooks. If the e-commerce designers have outdated knowledge on engaging with dominant consumers, the fashion retailer’s app will be inefficient at enticing contemporary consumers: generation-y women.

Generation-y shows a greater engagement with online communication through social media than generation-x, attaching high importance to always being connected (Bento et al., Citation2018). Social media is also a vital platform for brand engagement, which fashion brands embracing to market to their target consumers (Holt, Citation2016). Through inter-personal marketing events and paid adverts, fashion brands encourage their consumers to share product discoveries via their favorite social network (A. J. Kim & Ko, Citation2010). Consumers sharing product links via social networks is named Electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM) (Wolny & Mueller, Citation2013). EWOM and selling through social media platforms – Social Commerce (s-commerce) – are important for generation-y consumers. They react to the brand’s social media presence with greater vigor than generation-x (Bolton et al., Citation2013). Current research defines generation-Y’s reaction to eWOM in multiple contexts, including general eWOM perceptions (Zhang et al., Citation2017), fast-food restaurants’ eWOM creditability (Shamhuyenhanzva et al., Citation2016), and hotels’ eWOM strategies (Serra Cantallops & Salvi, Citation2014). The literature, however, omits recommendations on how to design effective apps to increase generation-y’s response to eWOM or encourage fashion purchase behavior using Mobile Commerce (m-commerce or app) design features. Only Balakrishnan et al. (Citation2014) considers eWOM, purchase intention, and brand loyalty. However, Balakrishnan et al.’s (Citation2014) work is limited to Malaysian university students and general online purchasing. Rodríguez-Torrico et al. (Citation2019) showed that m-commerce satisfaction and convenience influence trust and purchase behavior. Nevertheless, Rodríguez-Torrico et al. (Citation2019) take a general approach without a specific market focus or generation demographic. It is, therefore, uncertain how Rodríguez-Torrico et al.’s (Citation2019) and other authors’ findings relate to fashion e-Commerce for generation-y women.

App design features create consumer engagement and interaction, with the most desired features being the most powerful to encourage consumer spending. While Ladhari et al. (Citation2019) determined generation-y’s four approaches to online shopping and six shopping profiles, they omit any guidelines on designing for generation-y’s unique profile. Only Magrath and McCormick (Citation2013) consider the branding design elements of m-commerce fashion retail apps. The latter authors, nevertheless, only analyze fashion retail apps’ context. Magrath and McCormick (Citation2013) exclude dominant consumers’ reactions, reflections, emotions, and mixed generations within their analysis. The apps that Magrath and McCormick (Citation2013) studied are also, by now, outdated and irrelevant to contemporary fashion retail. Determining the app features that generation-y women respond to the most will enable app designers to select the tools to engage with the most salient motivations and desires for social intercourse – increasing an apps’ ability to meet its business goal.

Aim and objectives

This paper aims to determine Generation Y’s unique interaction with – and perception of – fashion m-commerce apps. To achieve this aim, we need to understand:

How generation-y women engage with m-commerce in order to allow retailers to design apps that capitalize on their target consumers’ behaviors?

How generation-y women react to Social Media eWOM within m-commerce apps in order to allow retailers to shape in-app social media integration?

What are generation-y women’s most desired app features and their association with purchase intention in order to allow retailers to direct the design of effective m-commerce apps?

In addressing the objectives, we conducted 27 semi-structured interviews to define generation-y’s m-commerce engagement, eWOM reaction, and desired app features. We show that m-commerce’s convenience is the greatest motivator for generation-y retail engagement. Expensive items (e.g. luxury garments) represent a demotivating factor for engagement because of lower levels of trust in the smartphone retail platform. We show that Interpersonal Social Media and eWOM encourage generation-y’s purchase intention for fashion items. We conclude by offering practical recommendations for m-commerce app design, communicating the desired features of fashion retail apps that influence generation-y’s purchase intention.

Literature review

M-commerce engagement

To address objective one – how generation-y women engage with m-commerce – this section reviews m-commerce customer engagement.

Earlier research describes how generation-x consumers fulfill their desire to increase their social status and prestige through buying luxury products (Han et al., Citation2010; O’Cass & Frost, Citation2002). Buying luxury products is only one path the fulfilling consumers’ desires. H.-S. Kim (Citation2006) describes fulfilling generation-x consumer’s needs through functional (utilitarian) and experiential (hedonic) shopping. The consumers’ utilitarian and hedonic shopping motivations further comprise personal and goal-orientated activities. Generation-y’s hedonic and utilitarian motivations are complex and in dispute within the literature. While Lissitsa and Kol (Citation2016) claim that generation-y are more hedonically motivated, C. J. Parker and Wang (Citation2016) find utilitarian motivations more influential. Okonkwo (Citation2016) highlights that generation-x consumers are very aware of high-end brands, have a strong identification with high-end brands, believe luxury brands have a more recognizable style than high-street brands, and feel luxury brands represent strong social symbolism and emotional associations. Ladhari et al. (Citation2019) claim Generation-Y shoppers approach e-commerce relative to trend, pleasure, price, or brand shopping. While Okonkwo (Citation2016) and Ladhari et al.’s (Citation2019) work is interesting, their findings are at odds with the more established utilitarian and hedonic motivation framework previous authors have used to great effect (H.-S. Kim, Citation2006; C. J. Parker & Wang, Citation2016).

Social media eWOM within m-commerce apps

To address objective two – how generation-y women react to Social Media eWOM within m-commerce apps – this section reviews social media within online fashion retail and its relationship to eWOM.

Social media is a formidable marketing channel where 76% of consumers use sites – including Facebook and YouTube – to inform their fashion purchases (King, Citation2017). While King (Citation2017) omits intergenerational differences, such information acquisition influences a brand’s reputation, increases sales, and delivers marketing messages for generation-x (Shaltoni, Citation2017) and generation-y (Annie Jin, Citation2012). Although social media can increase reputation, brand equity decreases consumer equity in both generations-x and y (Keen, Citation2012; A. J. Kim & Ko, Citation2012). Consumers aged 16 to 34 – generation-y consumers – are more likely to engage with retailers through social media than generation-x (Carroll, Citation2017). Zhang et al. (Citation2017) outlined that peer pressure influences generation-y’s adoption of eWOM. However, Zhang et al. (Citation2017) paid a random sample of American volunteers to respond to restaurant-based scenarios, with a questionable generalization of UK fashion. In a similar service-orientated study, Soares et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated how generation y is more likely to complain about poor service via online networks than generation-x. Nevertheless, their generalizability to fashion is, again, questionable.

Marketing through social networks is named Social Media Marketing (SMM), defined as “a two-way communication seeking empathy with young users, and even enforcing the familiar emotions associated with existing luxury brands to a higher age group” (A. J. Kim & Ko, Citation2012, p. 1480). Stelzner (Citation2011) identifies six benefits of SMM:

Formation of qualified leads,

Strengthened search ratings,

Reduced overall marketing expense,

Established beneficial attention of consumers,

A growth in site traffic and the number of subscribers,

Encouraging consumers to purchase from a particular brand.

SMM has added benefits to the fashion industry. SMM inspires both generation-x and y consumers to engage with brands, visit social media sites, establish positive attention, and stimulating purchase behaviors (K. H. Kim et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, K. H. Kim et al. (Citation2012) omits intergenerational differences between generation-x and y, and only focuses on luxury fashion retail.

Fashion brands must encourage positive social media eWOM and stimulate purchase intention. The literature, for six decades, recognizes word-of-mouth as the most effective communication channel through which ideas, innovations, and memes diffuse throughout society (Rogers, Citation1962). It is, therefore, surprising that the e-Commerce community has taken so long to focus on eWOM to market their products. As López et al. (Citation2016, p. 168) state, “although more and more studies are analyzing [eWOM], the topic is still very recent, thus very little is known about how to develop a [eWOM] campaign effectively.”

Effective eWOM implementation is essential. Negative eWOM is more influential than positive eWOM (Bachleda & Berrada-Fathi, Citation2016). Nevertheless, Bachleda and Berrada-Fathi (Citation2016) mix generation-x and y’s opinions into a single sample, making inferences about eWOM’s influence on generation-y elusive. However, if eWOM is more influential than positive eWOM, this is serious as fashion retailers neglect eWOM’s impact on consumer attitudes (Gvili & Levy, Citation2016). Gvili and Levy (Citation2016) prove the link between generation-x’s negative eWOM perceptions and negative perceptions toward the company the eWOM mentions. It is, therefore, imperative that fashion retailers foster positive eWOM communications with generation-y, aligning with their brand image for marketing. Nevertheless, how retailers can foster positive eWOM within the app retail platform is unclear.

App features and purchase intention

To address objective three – what are generation y women’s most desired app features and their association with purchase intention – this section reviews fashion retail app design and how designers apply app features to encourage purchase behaviors.

M-commerce design features are the User Interface elements that deliver information and esthetic appeal to the customer. C. J. Parker and Doyle (Citation2018) recommend that fashion retailers select, and apply, emerging technologies to meet or exceed their customers’ expectations and create multiple atmospheric levels. A universal approach to m-commerce design by market sector is, therefore, is elusive. Employing a consumer-desire centric, rather than market-sector centric, application of technology contradicts traditional notions of exclusivity associated with luxury. Djamasbi et al. (Citation2010) found that generation-y consumers prefer large images, images of celebrities, minimal text, and search features – more so than generation-y (Kuo et al., Citation2004). Nevertheless, Djamasbi et al. (Citation2010) and Kuo et al.’s (Citation2004) work relies upon outdated modes of design that have limited applicability to modern smartphone apps.

Inexpensive to produce smartphone apps allow fast-fashion retailers to deliver the same m-commerce experience as luxury retailers. Fast fashion retailers mimicking luxury fashion retailers may have adverse effects. Díaz et al. (Citation2016) luxury brands’ three principal categories:

Brand marketing communication without a focus on usability, credibility, involvement, or reciprocity.

Retail engagement focus on fostering loyalty.

Limited marketing communication with a lack of commitment to the e-commerce platform.

While Díaz et al. (Citation2016, p. 419) make design recommendations to “improve the presence of all the dimensions,” such strides only seek to homogenize the m-commerce platform. Nevertheless, Díaz et al. (Citation2016) focus on content analysis of published websites instead of focusing on user desires or generation-x and y differences. The concept of a universal design ideal for fashion m-commerce is clear from a cursory glance at the UX design literature (Anderson, Citation2011; Fogg, Citation2003; Preece et al., Citation2019), yet its applicability to user desires is untested. Nevertheless, fast-fashion retailers are unlikely to meet or exceed their customers’ expectations and desires if they mimic luxury fashion retailers by ignoring usability, reducing customer involvement and reciprocity, and limiting marketing communication. Furthermore, much research into design app features mixed generations-x and y – or ignored generation as a potential influence – making a generation-centric design approach elusive (e.g. Shankar et al., Citation2016; Zhao & Balagué, Citation2015).

Materials and methods

Setting and sample

We sampled 27 UK-based – British – women aged 23–34 (M = 25, SD = 1.8). We used purposive sampling to address the study’s objectives, with suitable generalizability to fashion m-commerce consumers (Galletta, Citation2013). We required participants to be born between 1982 and 2000 to be part of generation-y (US Census Bureau, Citation2015). We selected women as our sample to reflect fashion marketing’s focus on women over men (Hernández et al., Citation2011; Sender, Citation2019).

To facilitate interviews, we required participants to live within one hour’s drive of Manchester (UK) and shop via m-commerce fashion apps at least once per month. To limit nationality and social influence, we required participants to be British or have lived in the UK since childhood.

Through interviewing 27 generation-y women, we reached saturation in our data: where we did not obtain additional information, making further coding unnecessary (Guest et al., Citation2006; C. J. Parker, Citation2021). Our sample frame is also greater than comparable studies (Philip et al., Citation2019; Xue et al., Citation2020). Our sample was of mixed ethnicities: Caucasian (n = 17), Asian (n = 3), Asian-mixed (n = 4), and black (n = 1). However, our thematic analysis found no similarities between ethnicity and coding, precluding ethnicity as a discriminative variable within the thematic analysis. Our sample has a high level of education, with the majority holding undergraduate (n = 19) or postgraduate (n = 8) degrees. Our sample comprises young professionals (n = 24) but with some mature students (n = 3).

We sampled participants via posters placed around Manchester’s city center and through paid-for social media adverts on Twitter and Facebook (restricted to the UK’s North West region). The posters and targeted adverts linked the viewer to the study’s website – a Facebook page – that provided further information on the study and invited participants to sign up via an online Google Forms survey. We asked participants to describe their age, gender, location, nationality, ethnicity, and interest in fashion retail within the survey. We then contacted participants via e-mail to confirm their appointment, arrange the interview, or – where necessary – inform them of their unsuitability for the study.

Data collection

In designing the data collection procedure, we focused on the experiences and perceptions of participants relating to fashion m-commerce engagement. The study involved qualitative interviews – in line with comparable studies (Chipangura et al., Citation2013; Yeh & Li, Citation2009). We selected the semi-structured interview approach to allow the researchers to explore the themes required by the research questions while allowing participants to explain their thoughts in any way they choose.

The semi-structured interview guide comprised six themes, selected to address the three research questions, as highlights. Our interview questions focused on perceptions of all fashion platforms, from fast fashion to luxury, depending on the participant’s experience and preference. We conducted a pilot study with three persons to ensure that all questions were clear and appropriate to the objectives – with minor corrections made as necessary.

Table 1. Research constructs as the basis of the questionnaire concerning the Objectives

We conducted our in-depth semi-structured interviews either in person within a semi-public location – including coffee shops and libraries – for a single duration of 30 to 60 minutes – as executed by contemporary qualitative research (Philip et al., Citation2019; Xue et al., Citation2020). After arriving at the semi-public interview location, we gave participants complete information on the research study before signing the ethical clearance. Before going through the semi-structured interview questions, we asked participants to describe the fashion m-commerce apps on their smartphones. Our questions followed participants interacting with some of the Apple App store’s most popular retail apps during the research period. These apps represent the most common fast-fashion (Zara, ASOS, and Pretty Little Thing), high street (JD Sports, Next, and New Look), and luxury retailers (Givenchy, Mulberry, and Burberry).

Data analysis

Our data collection gathered interviews from 27 women. We transcribed interviews verbatim and analyzed the qualitative transcripts using the thematic analysis method (Boyatzis, Citation1998; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). Under thematic analysis, the researchers encoded qualitative information into underlying themes, common to pre-specified groups, in a systematic and accurate form (Boyatzis, Citation1998). First, we encoded the raw data into themes before categorizing this coding to relate to the concepts under investigation: “Coding can be thought about as a way to relate our data to our ideas about these data” (Coffey & Atkinson, Citation1996, p. 27).

To undertake thematic analysis – and increase our coding visibility, collaboration, and rigor – we used NVivo 12 (QSR, Citation2019) to identify themes and patterns across the participant responses (Bazeley & Jackson, Citation2013). NVivo allows researchers to encode qualitative data on a computer instead of the traditional paper and pen methods described in early thematic analysis work. The software offers the researcher the opportunity to transform codes into themes – otherwise known as categories.

To mitigate the potential for misinterpreting the data, the authors – both fluent English speakers – conducted double coding. With our double coding, we required an agreement equal to, or greater than, 80% to verify the resultant coding system. Our first round of coding required a line-by-line reading of transcripts, creating descriptive codes and labels corresponding to the participants’ words and ideas. We then grouped these by overarching concepts instead of words. For this reason, we omit individual emotional expressions in favor of common verbalized opinion, in line with the process of thematic analysis (Bazeley & Jackson, Citation2013). Our second round of coding sought an emergent fit between ideas and theory to generate a codebook related to our research objectives.

To address Objective 1 – to understand how generation-y customers engage with m-commerce – we analyzed the codebook for efficiency and convenience (Larivière et al., Citation2013), m-commerce engagement behaviors (Schadler & McCarthy, Citation2012), and financial risk interactions (Evanschitzky et al., Citation2004).

To address Objective 2 – to understand how generation-y consumers react to Social Media eWOM within m-commerce apps – we analyzed the codebook for online interpersonal interactions, including interest, purchase intention, and social sharing with others (Yang & Kim, Citation2012).

To address Objective 3 – to understand Generation Y’s most desired app features and their association with purchase intention – we analyzed the codebook for app purchase intention simulators (Ha & Lennon, Citation2010), app information content (McCormick & Livett, Citation2012), and how app design features meet the consumers’ shopping motivations (Arnold & Reynolds, Citation2003; Babin et al., Citation1994; H.-S. Kim, Citation2006).

When interrogating our NVivo codebook to answer our research objectives, we considered sub-themes by recurrence, forcefulness, and repetition (Keyton, Citation2010).

Results

M-commerce engagement

This section investigates Objective One: How generation-y women engage with m-commerce.

M-Commerce’s Use

Efficiency and convenience dominate participant’s m-commerce use. Twenty-one participants said that fashion apps help them by “saving time.” However, Participant [6] stated: “ … it is still not enough to get information about the brand”. Sixteen participants, furthermore, said apps help them access the latest discounts. Participant [13] exemplifies the power of discounts through their comment, “ … if the brand provides me special discounts, especially the customization one can affect me the shop through mobile app … .” In comparison, eight participants said that access to the latest discounts is often irrelevant as they compare multiple retailers’ prices online. Participant [6], for example, states, “I use both online and physical stores! First, I check the items online, and then I buy them at stores.” Efficiency, discounts, and timesaving are essential – and seductive – to generation-y women. However, the retailer must remember the hedonic brand aspects to maintain and encourage sales.

M-Commerce Feature Interaction

Utilitarian app features dominated participant’s experience with current m-commerce apps, with 66 references made, as opposed to 27 references to hedonic app features. Of these hedonic app features, information-seeking functions (27 references) and shopping facilitation functions (39 references) divide participants.

While purchasing fashion items is an essential part of the m-commerce app’s utilitarian engagement (14 references), participants achieve self-actuation through information acquisition (26 references) over purchasing fashion items (14 references). Customers seek information in four categories: product information (e.g. size and availability; 17 references), store information (e.g. location and opening times; five references), account details, and seasonal sales information (two references). Participant [3] exemplifies information seeking’s importance by stating: “ … [apps] show pictures of models and give you an idea [of] how to wear those items … ”. Participant [1] also states: “[the app lets] me know what they have available, in what sizes and how I can purchase it.” Our results suggest that the more product images the app can offer generation-y women, the more persuasive the app will be in making a sale.

Device Interaction and Engagement (Financial Risk)

Financial risk influences generation-y women when they select their fashion retail platform. While participants made five references to being comfortable buying expensive items via apps, the participants made 27 references to feeling uncomfortable with in-app purchases. Distrusting on-screen representation (seven references) and preferring larger screens – such as laptops or tablets – (six references) or desiring the in-store experience (five references) were the leading causes for distrust. Participant [3] stated, “I always check online, and then I go to the store to try on. I think the problem to me is to trust how I will look with that item”. Participant [20] also said, “No, I can’t see all the details of the product, and I’m not comfortable enough to buy expensive items on my mobile. I would [buy them] on my iPad though.” While smartphone screens cannot increase, offering generation-y women cross-platform shopping – where they can, for example, search for items of their phone before viewing them on a smart TV – may increase m-commerce sales.

Social media eWOM within m-commerce apps

This section investigates Objective Two: How generation-y women react to Social Media eWOM within m-commerce apps.

Sharing Fashion Item Links (eWOM)

Generation-y women have limited interaction between social media and fashion retail. Fifteen participants said they have never shared a link or picture of the fashion items to their significant others (families or friends) via social media.

Eleven participants, however, said they engage in eWOM: sharing links or images from fashion websites to their social media accounts. The primary motivation for social sharing was to inspire friends (six responses) or gain their friend’s opinion (five responses). Participant [1], for example, said, “[sharing] to get [my friends] opinions on what [the fashion item] looks like, will it look good on me, is it worth the money, etc.” Therefore, social networks are a strong channel of marketing for the retailer based on interpersonal communication – where consumers share garments from fashion retail apps. As interpersonal communication is the most persuasive form of communication (Rogers, Citation2003), designers should integrate social sharing into most fashion m-commerce apps that target generation-y woman.

Purchasing Items Due to eWOM

Only eight participants purchased a fashion item because their friends shared a link or picture via social media. The remaining 18 participants claimed their friend’s eWOM posts did not influence their shopping behaviors, giving reasons including different personalities or style taste to their friends. However, fifteen of those participants claimed to have shopped for fashion items after seeing the items marketed on social media.

While liking the garment and matching it to the generation-y woman’s style inspired nine responses, social media celebrities and bloggers were prominent, inspiring five responses. For example, Participant [12] said, “[I] see a product on someone, and you think ‘that looks good,’ and you just want the same thing. That is basically what fashion bloggers are about, and it works”. Generation-y women are, therefore, as influenced by celebrity culture as previous generations. Such influence suggests eWOM integrated with apps functions more of marketing than direct sales for fashion retailers. Fashion retailers should continue to use celebrity culture within their apps, transitioning to friends’ social media feeds when the generation-y women share the page to their social media feed.

To contextualize interpersonal communication (eWOM), we must consider generation-y women’s reaction to s-commerce. S-commerce was very influential, in contrast to eWOM’s limited impact on our sample. Despite 19 responses claiming s-commerce’s influence on their shopping behavior, 11 participants (18 references) claimed s-commerce does not interest them. Participant [16], for example, stated, “I prefer shopping and browsing on my own,” and participant [19] explained, “my friends don’t share fashion-related links or photos often.” The participants’ lack of interest in s-commerce is because they see social media as providing inspirational ideas instead of shopping recommendations (eight references). For example, Participant [3] said: “I see ideas in social media, but I do not really buy exactly the same item, but I could find something similar (with better prices or better qualities).” Retailers should, therefore, be conservative about s-commerce’s ability to drive sales with generation-y women; s-commerce influences generation-y women more than eWOM.

App features and purchase intention

This section investigates Objective Three: What are generation-y women’s most desired app features and their association with purchase intention.

Desired App Features

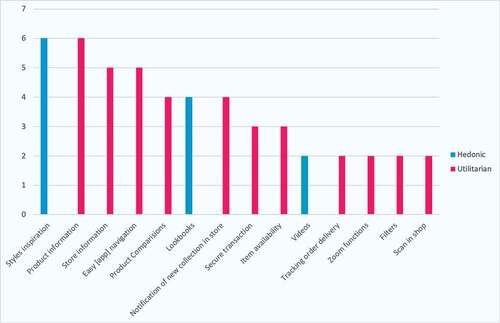

Considering the app features generation-y women most desire, utilitarian features were the most prominent with 56 references, including enhanced product details, comparisons, easy navigation, and store location/ opening times; see . While essential to the customer’s in-app experience, hedonic elements only received 14 references, including style inspiration and video.

Six references supported the retailers offering more’ detailed information about products’ – shown through responses including “images of the clothing and detail descriptions about the product which likes, what is the [garment’s] material?” [5]. Therefore, having “style inspiration” (seven references) is vital to customers while they assess a fashion m-commerce app. For example: “the app should provide how to wear the [the fashion item] (ideas) … ” [3]. While generation-y women may enter the app with ideas of their style, the app must suggest combinations and styles to be persuasive and capitalize upon sales.

Fashion brands’ apps should be easy to browse and navigate (five references). Consider, for instance, participant [6]’s comment: “fashion brands’ apps should be clean and easy to search [for] items because of the smartphones’ screens are limited and small … ”. While straightforward navigation is fundamental to interaction design (Nielsen, Citation1994), the fact that generation-y women still desire straightforward navigation within their apps suggests that few fashion retailers are offering clear enough navigation.

Fashion Purchase Intent

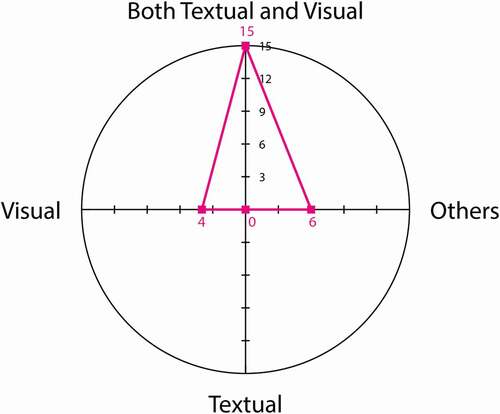

illustrates the participants’ preferred form of information context, highlighting visual and textual information’s combined use importance as the most persuasive form of information delivery (15 references). As participant [13] contextualizes: “[the] text helps me understand what is going on, but too [much] is kind of annoy and makes me do not want to read them … ”. While the text is vital to generation-y women, it only becomes powerful when combined with potent imagery, a combination more influential than the sum of its parts.

Figure 2. Preferences of the forms of fashion retail information context (references made through interviews).

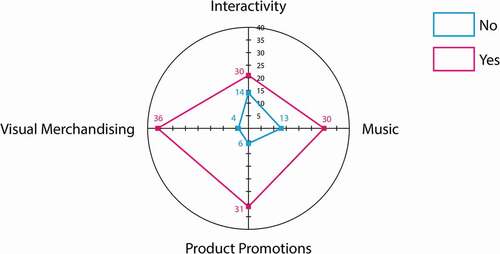

Of the factors that stimulate the intention to purchase, visual merchandising was the factor that most encouraged smartphone shopping, with 36 references; see . Layouts that participants perceived as on-trend and attractive were influential – being “ … easy to use, and the layout is important for the fashion items to be big enough to see on a small phone screen … ” [2]. On-trend and attractive layout’s prominence is interesting as “good graphics” (six references) were important in how they: “ … provide a [clearer] concept of the item, will be more persuasive than otherwise” [5]. Good graphics are, therefore, a hygiene factor – they are essential to maintain sales but do not encourage sales on their own – while a clear layout allows the app’s persuasive content to influence generation-y women without poor usability.

Figure 3. Stimulators of symbolic consumption in fashion retail (references made through interviews).

Participants made 31 references to product promotion as a vital element that may affect whether they bought an item. Seven participants mentioned searching for discounts, with comments such as “ … if the brand provides me special discounts, especially the customization one, can affect me the shop through mobile app … ” [13]. “Online exclusivity” was also crucial to two participants – shown through statements likes “it is important to get special sales and items via apps; you would usually not get it in the store … ” [11]. Smartphone m-commerce apps are, therefore, tools to aid shopping instead of new lucrative channels. If the smartphone apps ommit an economic advantage, then the generation-y woman will find other retail channels.

Participants said, through 28 references, that music or video would encourage them to make a purchase. Of these, 19 participants identified videos as a positive driver to shop via m-commerce apps. Participant [2] stated that “ … video footage makes shopping on mobile devices more interesting and interactive, such as videos of catwalk fashion or models showing the product … ”. Our analysis found that videos make shopping more entertaining: encouraging purchase behaviors.

Music – as a background enhancement within an app – received more divisive support than video. Seven participants stated that music encourages purchase decisions and might extend their time on the app. For example, participant [12] stated, “good music always puts people in a good mood, and videos are good to set a tone to the collection.” Ten participants, however, stated that music decreases their fashion app experience. Participant [2] stated, “music may have a negative effect depending on which genre/type.” Unless the brand has a close connection with a music genre, and therefore their target consumers, music has more potential to divide the customer base – and thus lose purchases – than any other app feature we investigated. Brands also change their target demographic; Vivian Westwood’s evolution from Camden Punk to international luxury exemplifies this concept.

Smartphone app interactivity was the least influential factor, although participants still made 21 references about interactive features increasing their likelihood to make a purchase. Participant [1] exemplifies interactivity’s influence by saying, “it makes it more engaging … therefore, I will browse longer.” Such positivity was limited, with 14 references saying interactivity decreased purchase intention. For example, participant [11] stated: “ … I do not use activities on the apps because I never feel like I have enough time for that. Also, I would rather be in a real shop with my friends and have interactivity with them … ”. While interactivity is essential, our analyses found that despite generation-y women growing up around advanced technology, they still prefer physical interaction.

Discussion and implications

Previous research has elevated m-commerce to a £77.4 billion per year retail platform (Carroll, Citation2019). Nevertheless, literature guiding m-commerce’s transcendence focused on generation-x’s shopping motivations, habits, and preferences (Winograd & Hais, Citation2014) over fashion retail’s contemporary dominant consumers: generation-y women (ONS, Citation2019; Soares et al., Citation2017). This study explores generation-y women’s interaction with – and perception of – fashion m-commerce apps through engagement, social media eWOM, and app features. By addressing this aim – and discussing our results in line with older generation-x based research – we will understand how retailers, marketers, and designers should develop apps for their contemporary dominant consumers.

M-commerce engagement

Our results show that generation-y women see fashion retail apps as utilitarian – information-seeking – tools instead of platforms for hedonic experiences. Of these, convenience’s “timesaving,” and efficiency’s “easy to find items” and “discounts” dominates generation-y women’s adoption of fashion apps. Access to information and discounts is noteworthy as it mirrors the participant’s desire for more information and preference for product promotion within app features. Generation-y women’s focus on utilitarian app engagement contradicts Brown and Lubelczyk (Citation2018) – who describe generation-y’s preference for hedonic experiences. Nevertheless, our findings agree with C. J. Parker and Wenyu (Citation2019), who describes western generation-y consumers’ preference for utilitarian apps. By agreeing with C. J. Parker and Wenyu (Citation2019), we confirm generation-y women’s focus on utilitarian app engagement when it has, previously, been unclear.

With a focus on utility, our findings align with TAM, a model that focuses on efficiency and convenience for user’s technology acceptance, and developed with generation-x subjects (Venkatesh & Davis, Citation1996). Our results also align with earlier research proving efficiency and convenience’s prominence in a fashion m-commerce context for generations-x and z (Larivière et al., Citation2013; Miettinen & Nurminen, Citation2010; C. J. Parker & Wang, Citation2016). Our finding’s replicability implies generation-x, y, and z women want to use apps as tools rather than entertainment portals. Efficiency and convenience are essential features for retailers to focus on increasing their consumer base. Bringing generation-y in line with earlier generation offers an exciting opportunity to strengthen TAM, efficiency, and convenience’s applicability over hedonism outside the generational context it was developed within.

Our results show that generation-y women may be reluctant to buy expensive items through fashion retail apps; relative to their perception of expense. Instead, our female generation-y sample prefers to pay via websites for higher-priced goods, have negative feelings about shopping for higher-priced goods via apps, and desire laptops or computers to make – what they perceive to be – expensive purchases. The negative feelings from these results can also contribute to negative motivators, which Fogg (Citation2009) relates to as “fear” in a general psychology context. These negative factors may reduce the consumer’s motivation to make purchases. This financial risk means that customers may experience distrust and discomfort when shopping for expensive products via apps. The participants’ experiencing distrust and discomfort when shopping corresponds with the concept of “price feeling” – the critical emotion of customers when they look at different prices of a product, proven within generation-x consumers (Evanschitzky et al., Citation2004) but previously untested for generation-y consumers. Therefore, high-end brands may consider using their brands’ image strength to boost customer-based brand equity (e.g. awareness and loyalty) in the app. They may offer customers a payment system they are confident using – such as Apple Pay. Retailers may also promote a free returns service, which would allow customers to examine products before they make a purchase decision, as has spurred ASOS’s growth in the UK (Cullinane et al., Citation2019). Retailers, marketers, and designers might also bias their app experience toward discovering cheaper items, and their website experience toward discovering expensive items.

Social media eWOM within m-commerce apps

Our results show that generation-y women are influenced by s-commerce, although eWOM has a limited impact on their purchase intention outside of style inspiration. EWOM’s limited impact is interesting as A. J. Kim and Ko (Citation2010) showed eWOM has a significant influence on purchase intention when focusing on luxury fashion customers. Our findings are novel, making a comparison to A. J. Kim and Ko (Citation2010) challenging due to their focus on Korean consumers and convenience sampling of generation-x and y customers.

Style inspiration is interesting as generation-y women desired more in-app style inspiration features as part of their style discovery. We, however, revealed that inspiring others was also the primary motivation for those who engaged in the fashion app’s eWOM – social media sharing – functions. Nevertheless, our sample perceived s-commerce and eWOM as integral parts of social media. Enabling customers to share discoveries and create eWOM provides a deeper level of customer experience than pure sales. EWOM satisfies the customer’s desire for self-actualization that fashion provides, as Okonkwo (Citation2016) described. Such eagerness to embrace social media as an extension of fashion retail agrees with Bento et al. (Citation2018), who describes generation-y’s great engagement in online communication – allowing consumers to visualize items as part of the purchase decision-making process. Nevertheless, we are excited to connect communication and inspiring others from the general context to the specific fashion context.

Our results also show that generation-y women embrace fashion information’s visual delivery – through collections, trends, and sales – within social media marketing. Visual delivery’s general standing complements earlier research that proves visualization through photos and video increases purchase intention with fashion retail for generation-y (Ha & Lennon, Citation2010) and generation-x (Biocca et al., Citation2001). These outcomes are important as Shaltoni (Citation2017) showed how older – generation-x – decision-makers in industry perceive eWOM and social media marketing as having limited benefit. Marketers and designers should consider visual merchandising as a tactical approach to drive generation-y women’s purchase intent via social media as we confirm the continuation of earlier research to generation y’s application.

Our results show that generation-y women’s dominant reaction to social media was their interest in products over brands. Interest in products over brand contradicts Holt (Citation2016), who professes s-commerce as central to fashion retail’s future. Interestingly, of our sample’s eWOM activities, 42% of the participants shared links and images of a fashion item to their network (e.g. families or friends). This action relates to role shopping’s motivation (H.-S. Kim, Citation2006), but may express enjoyment in social interaction enjoyment (Knapp, Citation1978). Expressing enjoyment in social interaction aligns with designers needing to consider enjoyment as an integral dimension of technology acceptance across generations-x and y (Groß, Citation2015; Igbaria et al., Citation1995). App designers facilitating customers sharing ideas could treat styles inspired by, or driven by, fashion icons as “idea shopping” motivators. Retailers could continue using, and promoting, fashion icons and influencers to advertise their fashion items instead of relying on aspirational imagery alone. Aspiration imagery may, itself, be insufficient. Our results suggest that retailers should consider creating opportunities for generation-y women to share fashion item images with friends and family through social media. Social media integration may be irrespective of the retailer’s market level.

App features and purchase intention

We show that – with fashion retail app design – visual merchandising and product promotions are the central stimulators that encourage generation-y women to shop. Therefore, fashion retail app’s visuals should remain a vital strategy to engage with the dominant consumers, as Okonkwo (Citation2016) recommends within the physical retail space. However, Okonkwo (Citation2016) focuses on generation-x consumers, so our outcome is new to describing generation-y’s perceptions. Visual merchandising and product promotions’ effect on generation-y women align with Krug’s (Citation2009) ideal standard practice of usability; make content beautiful and direct the customer’s journey through the interface. While this principle appears universal, Krug’s (Citation2009) work derives from earlier – generation-x centered – work on general usability by Nielsen (Citation1994) and Norman (Citation1988) – not related to fashion retail.

Fashion m-commerce’s intrinsic elements for motivating purchase intent are discounts and online exclusives. As Chaffey et al. (Citation2012) describe, discounts and online exclusives have been a vital retail tool for marketing product promotion since generation-x became the dominant consumer group (Chaffey et al., Citation2012). If this is true for generation-y, designers could make discounts and online exclusives discoverable from the app’s home screen to increase the customer’s awareness and purchase behaviors. As m-commerce app engagement is covered, these discounts should apply to fast fashion and high street retailers over luxury brands.

Interactivity was a secondary stimulus in encouraging purchase intent for our sample, despite our female generation-y sample desiring “adventure” shopping activities alongside efficiency-enhancing features. Our results suggest generation-y women may be more stimulated by virtual visual merchandising and product promotions than generation-x women. Interactivity may also have a more mooted effect on generation-y women than product promotions because of customers requiring efficient shopping via m-commerce – as this paper attests through m-commerce engagement. Interactivity also takes time for the user to process, interfering with the user’s shopping motivations (C. J. Parker & Wang, Citation2016). While Norman (Citation2005) and Anderson (Citation2011) have – since generation-x’s dominance – established that interactivity can generate emotional and reflective experiences, their work is has limited context in fashion retail and modern interactivity. Therefore, the marketer and designer must maintain the app’s efficiency and ease of use to increase interactive immersion.

Theoretical implications

Our research contributes to the m-commerce literature by providing new insights into a comprehensive understanding of generation-y women’s engagement with fashion retail apps, reaction to social media eWOM associated with fashion retail apps, and their most desired features m-commerce apps. In doing so, our discussion identifies where generation-y women’s experiences and behaviors align with, and contract, those of older generation-x adults. This marked intergenerational difference shows that retailers must design for generation-y women’s unique characteristics instead of taking general approaches. We show that Generation-y women want fashion retail apps to be shopping tools instead of shopping experiences. Retailers, marketers, and designers must develop fashion retail apps that follow this central mantra and break free from previous – generation-x based – design guidelines and business rules.

Our results suggest generation-y women’s desire for efficient and convenient apps means fashion retailers should offer item comparison functions within apps. Item comparison helps generation-y women access current prices, access current discounts, and gather information. However, access to discounts may harm luxury brands’ “price feel” (Evanschitzky et al., Citation2004). High-end fashion retails should, therefore, limit item comparison’s use in their apps.

Because of the lower levels of trust in the m-commerce platform, consumers have reduced confidence in purchasing through mobile apps. Reduced confidence in purchasing creates a necessary implication for fashion retail apps: the higher the retailers’ market sector, the more they must focus on experiential interaction to communicate the brand’s marketing messages. Through this, fast fashion brands can be successful by offering a catalog shopping app platform. Luxury brands must, however, communicate the emotions of exclusivity they wish to foster in their customers.

While social media is a persuasive communicator of eWOM for purchase intention, social media channels – including Facebook and Twitter – lack powerful enough sales motivators to overcome personal motivations relating to Idea Shopping for preexisting marketed ideas. Retailers should, therefore, apply eWOM and social media marketing to support – not replace – existing marketing channels. EWOM and social media marketing cannot be a fashion brand’s sole marketing channel for generation-y women.

This paper represents the first academic discourse in fashion app design for generation-y women, despite previous research focusing on generation-y’s decision making (Viswanathan & Jain, Citation2013), shopping motivations (C. J. Parker & Wenyu, Citation2019), general app selection in India (Jain & Viswanathan, Citation2015), and in-store technical services (Rese et al., Citation2019). Our guidelines address the knowledge gap for directing retailers and designing in creating apps targeted at generation-y women and answer the “how to” question posed by numerous researchers that identify a need for emotional or duel system designs without specific guidance. Rese et al.’s (Citation2019) work is interesting as they agree with our findings that technology cannot replace personal in-store service, and interfaces must be beautiful. Nevertheless, while Rese et al. (Citation2019) propose emotional value as essential to in-store fashion retail for generation-y, our results show utilitarian function to be more critical in the design phase. Viswanathan and Jain (Citation2013) also omit design guidance for generation-y in their duel-system approach.

Outside of academic discourse, user experience and interaction design courses and literature (e.g. Anderson, Citation2011; Evans, Citation2017; Grant, Citation2018; Mekler & Hornbæk, Citation2019) offer general advice and principles. As our paper shows, generation-y women have different engagement, interaction, and design requirements from previous generations.

Practical implications: Design guidelines

To support retailers, marketers, and app designers in creating m-commerce fashion apps for generation-y women, we offer : m-Commerce Design Guidelines for Generation-Y Women by market level.

Table 2. m-Commerce Design Guidelines for Generation-Y Women by market level

Our design guidelines go beyond Ladhari et al.’s (Citation2019) general consumer approaches to online shopping and Magrath and McCormick’s (Citation2013) narrow focus on branding design. In doing so, our design guidelines will help designers generate apps that connect with generation-y women’s motivations and perceptions with greater efficiency than existing practices and general design recommendations.

Designs must, however, apply our design guidelines with caution – hence our allocation by market level over blanket recommendations. Luxury retailers may hurt their brand image by using their m-commerce platforms for retail as they align themselves with their fast-fashion and high-street counterparts, as C. J. Parker and Doyle (Citation2018) describe. Luxury m-commerce designers should, instead, use their apps to deliver brand experience while maintaining their in-person sales focus. Through this, app designers can enhance their m-commerce platforms’ interaction elements by applying our design guidelines in general. Designers should consider – when applying these guidelines – that our findings relate to general fashion markets, markets that luxury fashion retail often places itself against.

Research limitations and further research

This paper is limited by its focus on generation-y women’s (aged 23–34) perspectives on fashion m-commerce in the UK. By omitting women under 23 and over 35, we could not directly compare generations x, y, and z women on e-commerce engagement, social media eWOM, and App feature preference. A cross-generational study between generation-y women, the established generation-x, and the upcoming generation-z could determine the generalizability of our results beyond generation-y. Furthermore, re-running this study with men will uncover how generalizable generation-y womens’ perceptions of fashion m-commerce through directly comparable data.

Our methodological use of thematic analysis also prohibited us from making claims about language use (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Future research utilizing alternative methods – such as grounded theory, ethnography, or phenomenology – will allow us to triangulate the results, gaining deeper insights into the psychological factors relating to generation-y women’s purchases motivations.

This paper also focuses on websites offering multiple brands. Future research should investigate whether generation-y women prefer m-commerce platforms offering products of only one brand or rather multi-brand m-commerce platforms. A further – tantalizing – opportunity is investigating how these insights apply to virtual reality retail, an upcoming platform that current research suggests will rewrite the design rules (Xue et al., Citation2020). Gender’s role in fashion m-commerce’s use is another avenue to pursue, which may lead to a better understanding of how marketers can engage dominant consumers. Furthermore, most eWOM research focuses on generation-y, social media’s target users. Repeating our study with generation-x women will allow for researchers to better generalize and contextualize our findings.

Our results also focus on Manchester: one of the UK’s largest and most affluent cities. As a prosperous urban region, our results generalize to other British regions, including London, Birmingham, and Edinburgh. Complimentary research into rural – or other European urban – areas building on this paper’s results will expand our understanding of generation-y women’s perceptions toward online retail. Doing so may help deliver a more extensive plethora of cognitive-based platforms instead of a one-size-fits-all approach.

As our sample size (27) exceeds most qualitative interview-based research samples, we are confident in the depth of our insight. Nevertheless, while qualitative research provides exceptional insight into why users perceive fashion m-commerce the way they do, semi-structured interviews cannot develop predictive models that can drive complex advances, such as AI-Driven retail interfaces. Quantitative research is, therefore, needed to model this paper’s outcomes. Quantitative research may model efficiency and convenience’s ability to drive app engagement, clarify why official marketing social media is more effective than friend’s social media posts, and describe why interactive design features are irrelevant in purchase motivation.

References

- Anderson, S. P. (2011). Seductive interaction design. New Riders.

- Annie Jin, S. (2012). The potential of social media for luxury brand management. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 30(7), 687–699. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501211273805

- Arnold, M. J., & Reynolds, K. E. (2003). Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing, 79(2), 77–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(03)00007-1

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209376

- Bachleda, C., & Berrada-Fathi, B. (2016). Is negative eWOM more influential than negative pWOM? Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 26(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-11-2014-0254

- Balakrishnan, B. K. P. D., Dahnil, M. I., & Yi, W. J. (2014). The impact of social media marketing medium toward purchase intention and brand loyalty among generation Y. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 148, 177–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.032

- Bazeley, P., & Jackson, K. (2013). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. Sage Publications Limited.

- Bento, M., Martinez, L. M., & Martinez, L. F. (2018). Brand engagement and search for brands on social media: Comparing generations X and Y in Portugal. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, 234–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.04.003

- Biocca, F., Daugherty, T., Chae, Z. H., & Li, H. (2001). Effect of visual sensory immersion on presence, product knowledge, attitude toward the product and purchase intention. In Proceedings of the experiential e-commerce conference. Michigan State University.

- Bolton, R. N., Parasuraman, A., Hoefnagels, A., Migchels, N., Kabadayi, S., Gruber, T., Komarova Loureiro, Y., Solnet, D., & Solnet, D. (2013). Understanding generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 24(3), 245–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231311326987

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, M., & Lubelczyk, M. (2018). The future of shopping centers. Kearney. https://www.kearney.com/consumer-retail/article/?/a/the-future-of-shopping-centers-article

- Carroll, N. (2017). Online retailing - UK - July 2017. Mintel. http://academic.mintel.com/display/793487/

- Carroll, N. (2019). Online retailing - UK - July 2019. Mintel. https://reports.mintel.com/display/920366

- Carroll, N. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on retail and ecommerce - UK - June 2020. Mintel. https://reports.mintel.com/display/1018559/?fromSearch=%3Ffreetext%3Dfashion%2520retail#

- Chaffey, D., Smith, P. R., & Smith, P. R. (2012). eMarketing eXcellence: Planning and optimizing your digital marketing (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Chipangura, B., van Biljon, J. A., & Botha, A. (2013). Prioritizing students’ mobile centric information access needs: A case of postgraduate students. In 2013 international conference on adaptive science and technology (pp. 1–7). IEEE. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASTech.2013.6707519

- Coffey, A. J., & Atkinson, P. A. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data: Complementary research strategies. Sage.

- Cullinane, S., Browne, M., Karlsson, E., & Wang, Y. (2019). Retail clothing returns: A review of key issues. In P. Wells (Ed.), Contemporary Operations and Logistics (pp. 301–322). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14493-7_16

- Díaz, E., Martín-Consuegra, D., & Estelami, H. (2016). A persuasive-based latent class segmentation analysis of luxury brand websites. Electronic Commerce Research, 16(3), 401–424. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-016-9212-0

- Djamasbi, S., Siegel, M., & Tullis, T. (2010). Generation Y, web design, and eye tracking. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 68(5), 307–323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.12.006

- Eastman, J. K., & Liu, J. (2012). The impact of generational cohorts on status consumption: An exploratory look at generational cohort and demographics on status consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211206348

- Evans, D. C. C. (2017). Bottlenecks: Aligning UX design with user psychology. Apress.

- Evanschitzky, H., Kenning, P., & Vogel, V. (2004). Consumer price knowledge in the German retail market. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 13(6), 390–405. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420410560299

- Fogg, B. J. (2003). Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

- Fogg, B. J. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design. In Proceedings of the 4th international conference on persuasive technology (pp. 40). ACM. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1541948.1541999

- Galletta, A. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond. NYU Press.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). Grounded theory: The discovery of grounded theory. de Gruyter.

- Grant, W. (2018). 101 UX principles: A definitive design guide. Packt Publishing.

- Groß, M. (2015). Exploring the acceptance of technology for mobile shopping: An empirical investigation among Smartphone users. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 25(3), 215–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2014.988280

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Gvili, Y., & Levy, S. (2016). Antecedents of attitudes toward eWOM communication: Differences across channels. Internet Research, 26(5), 1030–1051. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-08-2014-0201

- Ha, Y., & Lennon, S. J. (2010). Online visual merchandising (VMD) cues and consumer pleasure and arousal: Purchasing versus browsing situation. Psychology and Marketing, 27(2), 141–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20324

- Han, Y. J., Nunes, J. C., & Drèze, X. (2010). Signaling status with luxury goods: The role of brand prominence. Journal of Marketing, 74(4), 15–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.4.15

- Hernández, B., Jiménez, J., & José Martín, M. (2011). Age, gender and income: Do they really moderate online shopping behaviour? Online Information Review, 35(1), 113–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521111113614

- Holt, D. (2016). Branding in the age of social media. Harvard Business Review, 94(3), 13. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5534814

- Igbaria, M., Ivari, J., & Maragahh, H. (1995). Why do individuals use computer technology? A Finnish case study. Information & Management, 29(5), 227–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-7206(95)00031-0

- Jain, V., & Viswanathan, V. (2015). Choosing and using mobile apps: A conceptual framework for generation Y. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 14(4), 295–309. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1362/147539215X14503490289305

- Keen, A. (2012). Digital vertigo: How today’s online social revolution is dividing, diminishing and disorienting us ( Kindle). Constable.

- Keyton, J. (2010). Communication research: Asking questions, finding answers (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Kim, A. J., & Ko, E. (2012). Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1480–1486. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.014

- Kim, A. J., & Ko, E. (2010). Impacts of luxury fashion brand’s social media marketing on customer relationship and purchase intention. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 1(3), 164–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2010.10593068

- Kim, H.-S. (2006). Using hedonic and utilitarian shopping motivations to profile inner city consumers. Journal of Shopping Center Research, 13(1), 57–79. http://jrdelisle.com/JSCR/2005Articles/JSCRV13_1A3ShopMotivations.pdf

- Kim, K. H., Ko, E., Xu, B., & Han, Y. (2012). Increasing customer equity of luxury fashion brands through nurturing consumer attitude. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1495–1499. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.016

- King, M. (2017). Digital trends UK - Summer 2017. Mintel. http://academic.mintel.com/display/793337/

- Knapp, M. L. (1978). Social intercourse: From greeting to goodbye. Allyn and Bacon.

- Krug, S. (2009). Rocket surgery made easy: The do-it-yourself guide to finding and fixing usability problems. New Riders.

- Kuo, H.-M., Hwang, S.-L., & Min‐Yang Wang, E. (2004). Evaluation research of information and supporting interface in electronic commerce web sites. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 104(9), 712–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570410567702

- Ladhari, R., Gonthier, J., & Lajante, M. (2019). Generation Y and online fashion shopping: Orientations and profiles. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 48, 113–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.02.003

- Larivière, B., Joosten, H., Malthouse, E. C., van Birgelen, M., Aksoy, P., Kunz, W. H., & Huang, M. (2013). Value fusion: The blending of consumer and firm value in the distinct context of mobile technologies and social media. Journal of Service Management, 24(3), 268–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231311326996

- Lissitsa, S., & Kol, O. (2016). Generation X vs. Generation Y – A decade of online shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31(October), 304–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.015

- López, M., Sicilia, M., & Hidalgo-Alcázar, C. (2016). WOM marketing in social media. In P. De Pelsmacker (Ed.), Advertising in new formats and media: Current research and implications for marketers (pp. 149–168). Advertising in New Formats and Media. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/978-1-78560-313-620151007

- Magrath, V. C., & McCormick, H. (2013). Branding design elements of mobile fashion retail apps. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 17(1), 115–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021311305164

- McCormick, H., & Livett, C. (2012). Analysing the influence of the presentation of fashion garments on young consumers’ online behaviour. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 16(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021211203014

- Mekler, E. D., & Hornbæk, K. (2019). A framework for the experience of meaning in human-computer interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI ’19 (pp. 1–15). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300455

- Miettinen, A. P., & Nurminen, J. K. (2010). Energy efficiency of mobile clients in cloud computing. In Proceedings of the 2nd USENIX conference on Hot topics in cloud computing (pp. 4). USENIX Association. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1863107

- Nielsen, J. (1994). 10 usability heuristics for user interface design. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/

- Norman, D. A. (1988). The psychology of everyday things. Barbara DuPree Knowles.

- Norman, D. A. (2005). Emotional design. Basic Books.

- O’Cass, A., & Frost, H. (2002). Status brands: Examining the effects of non‐product‐related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11(2), 67–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420210423455

- Okonkwo, U. (2016). Luxury fashion branding: Trends, tactics, techniques. Springer.

- ONS. (2019). Internet access – Households and individuals, Great Britain: 2019. Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2019#over-half-of-all-adults-aged-65-years-and-over-are-now-online-shoppers

- Parker, C. (2018). Reimagining m-commerce app design: The development of seductive marketing through UX. In S. Oflazoglu (Ed.), Marketing (pp. 39–56). InTech. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.75749

- Parker, C. J. (2021). Sample size for design research ( Kindle). Water Bird. https://smile.amazon.co.uk/dp/B08TV6VQSG/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=design+sample+size&qid=1611482490&sr=8-1

- Parker, C. J., & Doyle, S. A. (2018). Designing indulgent interaction: Luxury fashion, m-commerce, and Übermensch. In W. Ozuem & Y. Azemi (Eds.), Digital marketing strategies for fashion and luxury brands (pp. 1–21). IGI Global. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2697-1

- Parker, C. J., & Wang, H. (2016). Examining hedonic and utilitarian motivations for m-commerce fashion retail app engagement. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(4), 487–506. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-02-2016-0015

- Parker, C. J., & Wenyu, L. (2019). What influences Chinese fashion retail? Shopping motivations, demographics and spending. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 23(2), 158–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-09-2017-0093

- Parment, A. (2013). Generation Y vs. baby boomers: Shopping behavior, buyer involvement and implications for retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.12.001

- Philip, H. E., Ozanne, L. K., & Ballantine, P. W. (2019). Exploring online peer-to-peer swapping: A social practice theory of online swapping. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 27(4), 413–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2019.1644955

- Preece, J., Rogers, Y., & Sharpe, H. (2019). Interaction design: Beyond human-computer interaction (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- QSR. (2019). NVivo 12 (Mac).

- Rese, A., Schlee, T., & Baier, D. (2019). The need for services and technologies in physical fast fashion stores: Generation Y’s opinion. Journal of Marketing Management, 35(15–16), 1437–1459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1665087

- Rodríguez-Torrico, P., San-Martín, S., & San José-Cabezudo, R. (2019). What drives M-shoppers to continue using mobile devices to buy? Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 27(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2018.1534211

- Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press.

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

- Schadler, T., & McCarthy, J. C. (2012). Mobile is the new face of engagement. Forrester Research. http://blog-sap.com/innovation/files/2012/08/SAP_Mobile_Is_The_New_Face_Of_Engagement.pdf

- Sender, T. (2019). Clothing retailing - UK - October 2019. Mintel. https://reports.mintel.com/display/920182

- Serra Cantallops, A., & Salvi, F. (2014). New consumer behavior: A review of research on eWOM and hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 41–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.08.007

- Shaltoni, A. M. (2017). From websites to social media: Exploring the adoption of internet marketing in emerging industrial markets. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 32(7), 1009–1019. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-06-2016-0122

- Shamhuyenhanzva, R. M., van Tonder, E., Roberts-Lombard, M., & Hemsworth, D. (2016). Factors influencing Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of eWOM credibility: A study of the fast-food industry. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 26(4), 435–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2016.1170065

- Shankar, V., Kleijnen, M., Ramanathan, S., Rizley, R., Holland, S., & Morrissey, S. (2016). Mobile shopper marketing: Key issues, current insights, and future research avenues. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 34(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2016.03.002

- Soares, R. R., Zhang, T. T. (Christina), Proença, J. F., & Kandampully, J. (2017). Why are generation Y consumers the most likely to complain and repurchase? Journal of Service Management, 28(3), 520–540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-08-2015-0256

- Stelzner, M. A. (2011). Social media marketing industry report. Social Media Examiner.

- Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. J., & Lance, C. E. (2010). Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. Journal of Management, 36(5), 1117–1142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352246

- US Census Bureau. (2015). Millennials outnumber baby boomers and are far more diverse, census bureau reports. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2015/cb15-113.html

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (1996). A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: Development and test. Decision Sciences, 27(3), 451–481. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1996.tb01822.x

- Viswanathan, V., & Jain, V. (2013). A dual-system approach to understanding “generation Y” decision making. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(6), 484–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-07-2013-0649

- Winograd, M., & Hais, M. (2014). How Millennials could upend Wall Street and Corporate America. Brookings.

- Wolny, J., & Mueller, C. (2013). Analysis of fashion consumers’ motives to engage in electronic word-of-mouth communication through social media platforms. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(5–6), 562–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.778324

- Xue, L., Parker, C. J., & Hart, C. (2020). How to design fashion retail’s virtual reality platforms. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 48(10), 1057–1076. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-11-2019-0382

- Yang, K., & Kim, H.-Y. (2012). Mobile shopping motivation: An application of multiple discriminant analysis. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 40(10), 778–789. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551211263182

- Yeh, Y. S., & Li, Y. Y.-M. (2009). Building trust in m-commerce: Contributions from quality and satisfaction. Online Information Review, 33(6), 1066–1086. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/14684520911011016

- Zhang, T. (Christina), Abound Omran, B., & Cobanoglu, C. (2017). Generation Y’s positive and negative eWOM: Use of social media and mobile technology. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(2), 732–761. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0611

- Zhao, Z., & Balagué, C. (2015). Designing branded mobile apps: Fundamentals and recommendations. Business Horizons, 58(3), 305–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2015.01.004