Abstract

Despite decades of effort, around 2.8 billion people still rely on solid fuels to meet domestic energy needs. There is robust evidence this causes premature death and chronic disease, as well as wider economic, social, and environmental problems. Behavior change interventions are effective to reduce exposure to harm such as household air pollution, including those using health communications approaches. This article reports the findings of a project that reviewed the effectiveness of behavior change approaches in cleaner cooking interventions in resource-poor settings. The authors synthesized evidence of the use of behavior change techniques, along the cleaner cooking value chain, to bring positive health, economic, and environmental impacts. Forty-eight articles met the inclusion criteria, which documented 55 interventions carried out in 20 countries. The groupings of behavior change techniques most frequently used were shaping knowledge (n = 47), rewards and threats (n = 35), social support (n = 35), and comparisons (n = 16). A scorecard of behavior change effectiveness was developed to analyze a selection of case study interventions. Behavior change techniques have been used effectively as part of multilevel programs. Cooking demonstrations, the right product, and understanding of the barriers and benefits along the value chain have all played a role. Often absent are theories and models of behavior change adapted to the target audience and local context. Robust research methods are needed to track and evaluate behavior change and impact, not just technology disseminated. Behavior change approaches could then play a more prominent role as the “special sauce” in cleaner cooking interventions in resource poor settings.

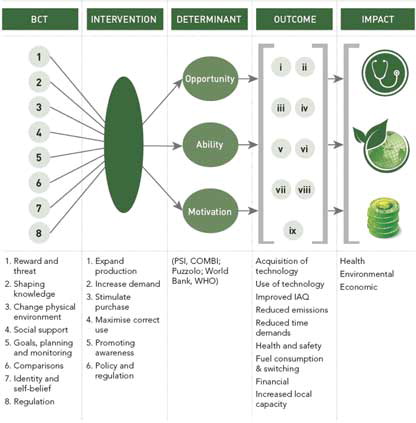

This article reports the findings of a review into the effectiveness of behavior change approaches in cleaner cooking interventions in resource-poor settings (Goodwin et al., Citation2014). The review produced evidence on the use of behavior change techniques (BCTs), a behavior change framework for clean cooking and a set of seven case studies, using a scorecard of effectiveness. The recommendations do not include an attempt to highlight or rank the most effective behavior change models or theories; rather, the review captures the key elements that make behavior change approaches more likely to succeed in ensuring the scale and sustainability of cleaner cooking interventions.

Despite decades of effort, around 2.8 billion people worldwide still rely on solid fuels such as wood, dung, and coal to meet their basic domestic energy needs (Bonjour et al., Citation2013). Typically, solid fuels are burned on open fires or on inefficient stoves, which leads to high levels of household air pollution. This pollution comprises a mix of toxic gases and particles known to cause (a) premature death and chronic disease in children and adults and (b) wider economic, social, and environment issues on a large scale (Lim et al., Citation2013). What people do, that is, their behaviors—for example, which stove and fuel they use; where they burn fires; how they use ventilation; and where children and adults are located—determines the intensity of this impact (Smith et al., Citation2014).

Some of the most significant barriers to the adoption of cleaner cooking practices are the entrenched complex behaviors that characterize stove and fuel use across the world. The field of behavior change provides frameworks and new ways of addressing these barriers (Jackson, Citation2005; Maio et al., Citation2007). Historically, many behavior change interventions have been based on rational cognitive models of behavior. Scientists now understand the primacy of non-cognitive influences, such as emotion, on behavior (Biran et al., Citation2014; Kahneman, Citation2011; Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, Citation2001). There has also been a move toward multilevel intervention models based on evidence from the fields of HIV/AIDS, sanitation, smoking, reproductive health and water (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, Citation2008). One example of a multilevel model is social marketing, which includes the concept of exchange (cost vs. benefit) that underpins the relationship between the consumer and a brand (French, Citation2006). An effective intervention strategy has been the use of change agents (e.g., peer educators, community health workers) to help bring behavior change interventions to scale (Valente & Pumpuang, Citation2007).

There is a growing base of evidence that behavior change interventions are effective, including those using health communications approaches. A 2014 review carried out by Population Services International found evidence that social marketing was an effective strategy for addressing HIV, reproductive health, malaria, child survival, and tuberculosis programs in developing countries (Modi & Firestone, Citation2014). A 2010 meta-analysis of health campaigns, such as seat belt use, oral health, alcohol use reduction, heart disease prevention, smoking, mammography and cervical cancer screening, and sexual behaviors, found small measurable effects on behavior change (Snyder et al., Citation2004). A 2014 review of sanitation social marketing interventions by Evans and colleagues found improvements in behavioral mediators, such as knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, with mixed results in behavior change (Evans et al., Citation2014). The role of regulation in concert with behavior change and policy has been shown to be effective (Hoek & Jones, Citation2011). Within the cleaner cooking sector, previous evidence includes a 2014 review of studies on child health which found that behavior change strategies can reduce household air pollution exposure by 20–98% in laboratory settings and 31–94% in the field (Barnes, Citation2014). There has also been recent work on the determinants, or factors, that determine the barriers and benefits to behavior change in the cleaner cooking sector (Lewis, Citation2012; Puzzolo, Pope, Bruce, & Rehfuess, 2013).

Method

This United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID)—funded desk review was carried out to analyze the use and effectiveness of behavior change approaches in cleaner cooking interventions within resource-poor settings. It is recognized that to achieve truly “clean cooking,” a switch to liquid fuels such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) or ethanol is required for all or most of the cooking in a community. Many factors, including economic and logistical barriers, means that this may not be realistic for large numbers of households now or in the immediate future. There are currently several types of improved solid fuel stoves, which range in their ability to reduce household emissions. The forced draft or semi-gasifier stoves have shown the potential to achieve low emissions whereas the more widely used “rocket” stoves produce more modest changes. In practice, very few intervention stoves or fuels are able to provide the reductions in air pollution necessary to alleviate the health impacts associated with continual exposure to biomass smoke (World Health Organization, Citation2010). Discussions on what constitutes the term clean in relation to stoves and fuels are ongoing and challenging. For the purpose of this article, we used the term cleaner cooking interventions to include any intervention, stove, fuel, ventilation such as a chimney/smoke hood, and/or education program that aims to reduce levels of household air pollution and personal exposures.

The report was commissioned as part of DFID's support for priority research to help deliver clean cooking solutions at scale. The team comprised experts in behavior change, health, economics and clean cooking from a consortium of specialist agencies and universities. The team first carried out a literature review to synthesize the evidence of the use of behavior change techniques (BCTs) for health, economic and environmental outcomes and impact. This was followed by a deeper analysis of effectiveness in terms of behavior change in relation to a selection of seven ‘case study’ projects, chosen to provide an illustrative range of BCTs, geographical location, cleaner cooking technology and scale.Footnote1

Four intervention elements were selected for review—impacts, outcomes, intervention, and BCTs. We had considered covering only those interventions that use and evaluate the impact of one of the more widely used behavior change models or theories. After discussion of an initial review of the literature, we determined that this would potentially exclude useful interventions and so we decided to focus on the building blocks for these theories and models, namely BCTs. The four elements do not always represent distinct and separate levels. A cleaner cooking intervention may contain numerous BCTs and work toward achieving several outcomes and impacts. Other projects—often the smaller, randomized controlled trials—may only use one BCT, and in effect the intervention is the BCT and vice versa.

For the purpose of this review a BCT is defined as the active component within a cleaner cooking intervention that catalyzes a behavior change. BCTs can be identified in activities undertaken at several points along the cleaner cooking value chain, including design, production, finance, distribution and maintenance (Hart & Smith, Citation2013). A long list of BCTs was produced from published lists (Michie et al., Citation2013). These were then clustered into eight BCT groups to enable a manageable reporting mechanism (see Table for full list of BCTs used and their definitions). These groupings were produced in advance of the search and then reviewed, validated and updated throughout the process.

Table 1. Cleaner cooking behavior change technique groupings

The search terms reflected the fuels, stoves and household management practices at the center of cleaner cooking interventions and were based on previous systematic reviews carried out in the cleaner cooking sector (Puzzolo et al., Citation2013). The search included all fuel types including clean fuels such as biogas, ethanol, and LPG. These terms included chullah, LPG, biogas, and cookstove and their variations. The BCT-related terms were informed by terms used in behavior change literature and ranged from the very broad (e.g., intervention, behavior change) to the very specific (e.g., habit, trigger, and norm; Lee & Kotler, Citation2011; Michie et al., Citation2013; U.K. Cabinet Office, 2010). A search of the published, peer-reviewed literature was conducted using major online research databases and the unpublished (gray) literature was also searched as systematically as possible. The search was augmented with personal communication and hand searching of references. The full list of databases and websites searched is shown in Table .

Table 2. Literature sources

This search process produced a long list of unique articles/reports, which was then screened to ensure those included met the following criteria: (a) described cleaner cooking interventions as defined by the team; (b) used one or more BCTs from the list; (c) implemented in low, low-middle, and upper-middle income countries as defined by the World Bank income region classifications (World Bank, 2014); (d) documented in English; (e) published and/or implemented since 2000. Documents describing formative research, or purely conceptual work, were excluded. Multiple steps were taken to ensure the quality of the literature identification and data extraction process.

Case Studies

Seven interventions identified through the literature review, were chosen as case studies to provide an illustrative range of BCTs, geographical location, cleaner cooking technology, funders and scale. The case studies were developed from data collected through the literature review and supplemented when possible with personal communications with project staff. Because of heterogeneity of evidence types from the peer-reviewed and gray literature and the limited resources of the team, assessment of the strength of evidence was only applied to the main sources of evidence for the seven case studies.

To evaluate the case studies, a scorecard of behavior change effectiveness was developed, drawing on existing scorecards and frameworks (Dolan, Citation2010; French, Citation2006; Michie, van Stralen, & West, Citation2011). The scorecardFootnote2 outlines benchmark criteria for an effective behavior change intervention. The criteria were as follows: (a) behavior focus, (b) target population, (c) barriers and benefits, (d) methods, (e) capacity building, (f) behavior change results, (g) outcomes, and (h) impact. Each case study includes scores based on these eight criteria, each containing two to three questions. Each question was worth 1 point for a maximum possible total of 22 points for each intervention, which was then converted to a percentage score for overall behavior change effectiveness. We started the process of testing and validating the scorecard by assessing the case studies, and it evolved during this process.

The information used to generate the scores is based solely on the desk review, supplemented when possible with personal communication with representatives from the implementing organization. No further field research or independent verification was conducted. The score does not imply a rating for the intervention's overall effectiveness, as there are other variables and data not captured or verified by this study. This includes the technical aspects of the technology (especially stoves and fuels) used as well as the scale and sustainability of impact. The scores are summarized in Table 4. For each of the case studies, the team also assessed the strength of evidence for one to two of the primary evidence sources using a previously validated tool (DFID, Citation2014).

Results

The search process yielded a list of 207 unique references. After removing those not meeting the inclusion criteria, 48 articles documenting 55 cleaner cooking interventions remained (see Figure ). These related to all aspects of the cleaner cooking value chain—32 in Asia, 15 in Africa, and 8 in the Americas—covering a total of 20 countries. The final list of articles was then reviewed, each one was tagged and its information extracted.

Results: BCT Level

Table provides a summary of the BCTs identified in the search. The most frequently used BCT is that of shaping knowledge, found in 47 cleaner cooking interventions (85%). An example of this was used by the Improved Cookstove Program led by the Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, which included local demonstrations and seminars, attended by representatives of local government. This was supplemented by subsidized advertisements and short films, which created a high level of demand for cookstoves (World Bank, Citation2010).

Table 3. Impacts and behavior change techniques identified in literature search (N = 55)

The next most frequently found BCT group is rewards and threats, with 35 interventions (64%) applying this technique. For example, in Indonesia, the Domestic Biogas Program (known locally as Biogas Rumah or BIRU), led by the Dutch nongovernmental organizations SNV and HIVOS, offered end users of biogas digesters an investment incentive of approximately 25% (Toba, Citation2013). Social support was a BCT used in 35 interventions (64%). The Indoor Air Pollution Reduction Program, led by Concern, VERC, and Winrock International in northern Bangladesh, established a cadre of promoters and community leaders. This also ensured local capacity to carry on all aspects of the intervention beyond the life of the project (Winrock, Citation2009).

Comparisons-based approaches were used in 16 interventions (29%) to encourage new behaviors. The Tezulutlán Improved Stove Project in the Baja Verapaz region of Guatemala contacted local leaders interested in promoting the intervention stoves. The team visited the homes of these local leaders, built the Tezulutlán stove and monitored its performance. Subsequently, the local leaders were asked to invite friends and family to view the stove and evaluate its performance in comparison to those previously used (Ahmed et al., Citation2005). Also, 15 interventions (27%) used identity/self-belief BCTs, for example the Deepam Scheme to promote LPG connections in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh was implemented through established grassroots women's self-help groups. This served to link the promotion of LPG to support for women's development and financial independence (Rajakutty & Kojima, Citation2002).

Fifteen interventions (27%) also contained regulation as a BCT. In Lao PDR, the government identified the development of regulations and guidelines as key to success for the Cleaner Stove Initiative (Toba, Tuntivate, & Tang, Citation2013). Also, 10 interventions (18%) involved changes in the physical environment as a BCT. India's Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Rasoi Ghar program facilitated cleaner and safe cooking by adapting the traditional concept of the community kitchen, or Sanjha Chulha (World LPG Association, Citation2005). Activating people's goals was the least widely found BCT, only documented in three interventions (5%). One example stems from PATH's research in Uganda to identify its audience's motivations for adopting the new stove. PATH found that fathers were motivated to be seen as more sophisticated and better-off than their neighbors (Mugisha, Citation2014).

Results: Impact and Outcome Levels

Table also provides a summary of the impacts and outcomes coded in the search – the health, economic and environmental benefits. Economic benefits (i.e., those documenting an economic related impact [negative or positive]), were widely reported (n = 15 articles and n = 37 interventions). For example, in the Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research Improved Cookstove Program, 84.5% of user households reported financial benefits due to decreased expenditure on fuel (World Bank, Citation2010).

The next most frequent documented impact was health (and safety related) benefits (n = 24 articles and n = 32 interventions). For example, the Ugandan Energy Saving Stove Project reported a 21% reduction in acute respiratory diseases among stove users. There was limited evidence of documented environmental benefits (n = 12 articles and n = 20 interventions). However, those that were identified showed significant impacts. Household surveys in Mexico showed a decrease in average wood fuel consumption of 67% after the introduction of the Patsari stove (roughly 3.5 tons of wood annually) (Troncoso et al., Citation2007).

Some of the studies identified did not report impacts. In these cases, intermediary outcomes, which could potentially lead to the impacts, were included. The most frequently reported outcome was that of technology (stove and/or fuel) uptake (n = 25 articles and n = 47 interventions). The Mongolia Improved Space Heating Stoves Program exceeded its goal of disseminating 7,000 improved cookstoves and distributed more than 15,000 units (World Bank, Citation2010). Indoor air quality improvement was the next most documented outcome (n = 18 articles and n = 26 interventions). An example of this is the Nepal Healthy Hoods program implemented by Practical Action, which saw post intervention indoor particulate levels fall by 88%, from 13.2 to 1.6 parts per million (Malla et al., Citation2011).

Case Studies

Table provides a list of seven interventions (projects, programs, or studies) selected for development as case studies.Footnote3 These were chosen from the final 55 interventions to reflect a number of important and interrelated factors: geography, scale, implementer, funder, scope, impact, and BCT. Some are national-level programs (e.g., China, Indonesia), others are smaller donor programs (e.g., Kenya, India), and yet others are field experiments (e.g., South Africa, Uganda). The Americas are not represented, as sufficient data was not available for the project selected for inclusion. The choices do not reflect any endorsement of the projects, technologies, or organizations involved. Information was taken from publicly available literature identified during the search plus, where possible, personal communication with project staff. Not all project organizations could be contacted, and therefore some gaps remain in the data reported.

Table 4. Case study interventions

Both GIZ's EnDev program in Kenya and Pertamina Indonesia's LPG conversion program received the highest scores of 86%. Impact Carbon's Uganda project received 82%, the University of Witwatersrand's behaviour change study obtained 80%; Geres Cambodia received 77%; Shell Foundation Room to Breathe in India obtained 73%; and China's NISP received 64%. The behavior change effectiveness scores cover a relatively narrow range—from 64% to 86%. This reflects the fact that organizations with BCT components were specifically chosen so their implementation within the cooking sector could be explored and described. A more random sample from the full literature review results would have provided a much more diverse but perhaps less illustrative results. The scoring allows for comparison across the studies, focusing on a range of elements identified by the authors as key to behavior change interventions.

Although the presence of BCTs was common, their implementation as part an established behavior change model or framework appeared to be rare. The Shell Foundation Room to Breathe project was one of only a few interventions reviewed that used a leading behavior change model. The social marketing approach of the Shell Foundation program included flexible financing and a mix of promotion materials, group activities, and personal communications. The intervention also used early adopters to demonstrate the technology, which is regarded as an effective tactic for changing behavior (Valente & Pumpuang, Citation2007). The inclusion of financial incentives and the engagement of change agents through partnerships with microfinance organizations boosted sales considerably. Although the project did not meet the target of 50,000 units sold, with only 11,000 units purchased, the lessons learned have enabled the Shell Foundation to improve the design of their projects in other countries (Shell Foundation, Citation2013).

Impact Carbon's ‘Strategies for Improved Cookstove Adoption in Rural Uganda’ project included a 6-month feasibility study before commencement of a series of randomized controlled trials. The team considered this useful for the baseline data collection and formative research, as well as to test the key elements of the intervention, such as the available stoves and the marketing messages for local acceptance. The final selection of health, financial and time related messages are strong rational messages, but are often considered to be the minimum information required to provoke behavior change within the target population and are usually not sufficient on their own to change behaviors. The weak results showed that the marketing messages had little impact on stove uptake but they do not explain whether it was due to the communication channels or the messages. Similarly, the success of the financial offers was encouraging but it may have been the promotion during group sessions that made them work effectively. It appears likely that effective interventions require the benefits of flexible financing mechanisms communicated with the relevant emotional messages through the appropriate channels (Beltramo, Levine, & Blalock, Citation2014).

The University of Witwatersrand Northwest Province Behavior Change Trial in South Africa did not include the use, promotion, or sale of any technology. It tested only messages (on ventilation, location of cooking and people) to change people's habits, delivered by health workers. The work aimed to produce a ‘proof of concept’ to understand whether behavior change has the potential to work in contexts of extreme poverty, where solid fuels are burned on inefficient traditional stoves in poorly ventilated kitchens, and where access to cleaner technologies is limited both economically and geographically. To underpin the study's design, it used the Trial of Improved Practices method, which is a formative research technique to pretest the actual practices that a program will promote. This is similar to Bandura's technique of mastery modeling which breaks significant behavior changes into smaller tasks. The combination of measuring behavior change (observed and reported) plus the household air pollution outcome was considered useful. The significant reduction in household air pollution achieved is encouraging but further study with larger sample sizes is required to gain more conclusive results (Barnes, Mathee, & Thomas, Citation2011).

The Geres Cambodia Fuelwood Saving Program was scored as highly effective, in part because it exceeded its sales targets. This project adopted a supply-side approach as it focused on building the stove production and distribution network. This project had other market-based solutions, which included incentives such as low-interest loans and business advice. The focus on strengthening the capacity of the supply chain makes the change more likely to be sustainable (Bryan et al., Citation2009). The project promoted a charcoal stove similar to stoves previously used in the target population. This minimized the degree of adaptation in cooking habits demanded from the user and thus increased the likelihood and ease of adoption. The likely effect of this type of stove has been the subject of much debate (Smith, Citation2014), with some saying that it would not produce a significantly improved human and environmental impact (Smith et al., Citation2014).

Discussion

Analysis of the findings reveal a mixed picture of the use of BCTs in cleaner cooking interventions. The BCTs and the activities in which these have been used were identified, but less clear is their effectiveness to bring about desired outcomes and impacts. While some good quality data are available, often absent are data on the outcomes and impacts of activities using BCTs, particularly those that are directly attributable to the BC component. The lack of evidence for BCT impact means that the authors could only make best guesses on most “active ingredient” in the intervention. It also meant that it was not possible to carry out a robust meta-analysis of the impact or the originally planned cost effectiveness analysis. However, it was possible to describe how the different types of BCTs were used and augment that with an analysis using the benchmark criteria developed for the Scorecard of Behavior Change Effectiveness.

There appears to be limited variation in the types of BCTs used in the 55 interventions reviewed. Shaping knowledge, reward/threat, social support, and comparison appear more often and usually in combination. This suggests that a typical cleaner cooking intervention is one that promotes an economic incentive for the new technology combined with some form of social support. For example, the Shell Foundation developed partnerships with micro finance institutions in India, which it credited with a large part of the success of the India Room to Breathe program (Shell Foundation, Citation2013). Impact Carbon used rent-to-own models in Uganda to entice potential customers. Both EnDev and Geres used micro-credit schemes in Kenya and Cambodia, respectively.

This suggests that the program designers consider these BCTs most effective; however, the evidence for the choice is not always clear. The most common forms of rewards are economic ones, including the subsidies provided by governments, nongovernmental organizations, and other providers of cleaner cooking technologies. Subsidies, and other forms of discounting, can work for and against adoption and sustained use, depending on how these are managed. Subsidies can provide access to better-performing stoves, which are often more expensive, but must be managed to avoid negative effects on markets and the perceived value of the products (Puzzolo et al., Citation2013). Little evidence was found in the 55 cleaner cooking interventions that account for the influence of emotion and other subjective/affective experiences on decision-making and intent.

“How” to deliver these BCTs was reported less consistently, including the channels through which the BCT is communicated, also known as the marketing mix. For example, posters were produced sometimes without testing or understanding how these would be received. This meant that it is difficult to determine whether it was the BCT or its communication that was effective or, in fact, ineffective. There were notable exceptions, with several programs testing and revising their messages and materials based on feedback. This includes Impact Carbon in Uganda, EnDev in Kenya and Shell Foundation in India.

A Behavior Change Framework for Cleaner Cooking

How to interpret a BCT and its relationship to other elements in the cleaner cooking intervention framework was not immediately obvious at the start of the project. An example is passing a law providing for a subsidy or a restriction on a particular fuel, such as on LPG in the Pertamina Indonesia conversion program (Budya, Citation2011). To be effective, the law must be communicated (shaping knowledge), enforced (reward and threat) and sustained (social support). Which ones of these BCTs was effective? Using the evidence gathered through the case studies, the team concluded that a mix of BCTs in an intervention should target all aspects of the cleaner cooking value chain, e.g., GERES Cambodia focusing on the suppliers and Shell Foundation in India focusing on user engagement. In addition, the framework should reflect the multilevel nature of development, which includes individual behavior, group dynamics, environmental factors and social determinants.

The review carried out by Puzzolo and colleagues (Citation2013) and similar research suggests that there are multiple determinants specific to each context. The determinants are the enabling or limiting factors, which can help ensure more successful delivery of programs. The logical place for the determinants in the cleaner cooking behavior change framework is between the intervention and outcomes. Using this finding, the team was able to position determinants in the behavior change framework for cleaner cooking (see Figure ).

Use of Theories of Change and Behavioral Approaches

The limited use of researched and tested theories of change to underpin the design and implementation of interventions is considered a shortcoming for many of the programs reviewed. A program theory of change enables the intervention manager to set out and articulate the concepts and assumptions that underpin the anticipated change process. Most interventions are framed around a belief about how the program will work, but the process through which the outputs will turn into outcomes needs to be considered and articulated, and its theoretical foundations made explicit (Vogel, Citation2012).

Compared with other sectors, there is a relative absence of specific strategies, plans and activities based on behavior theory, models and research. For example, shaping knowledge was the most frequently used BCT found in this study; however, there was often little demonstrated understanding of how people produce, use, and share information. Because interventions did not explicitly use or refer to behavioral models or theories, it is more difficult to determine why these were or were not effective. This makes expansion and learning from others more problematic.

There are some notable exceptions. As previously discussed, some of the case studies did use behavior change models, such as the Shell Foundation Room to Breathe project's use of social marketing. The Shell Foundation paid close attention to the barriers to change and developed the marketing campaign to promote the benefits of the new technology for the family. It also focused on the decision making process for stove acquisition, including the dynamics between the husband and wife (Shell Foundation, Citation2013). Mexico's Patsari program adopted an approach based on Diffusion of Innovation theory, in this case focusing on the dynamics around the intensity of stove use as the innovation to be diffused (Pine et al., Citation2011).

Limitations

The review did not yield the type and extent of information to allow conclusions to be drawn on the most effective BCT necessary for the success of cleaner cooking interventions. However, analysis of common themes from the literature review and case studies in addition to drawing from other sectors identified some strong trends and probable relationships, which can guide practice and further research.

The lack of consistent and credible evidence for cleaner cooking interventions using BCTs restricted our ability to draw conclusions across the sector. We had planned to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis to provide a comparison between the case studies; however, the available data did not allow for this to occur. In some cases, impact and outcome measures were not collected; in others, the cost information was not available. Also, the measures of effectiveness differed across interventions (e.g., for health and economic impacts), which means direct comparison was not possible.

Recommendations and Conclusions

Intervention designers should develop a program-specific theory of change to show how the expected outcomes will be achieved in a population given the local conditions. This may include replicating a similar intervention (or combination of activities) in comparable circumstances. Making the intervention's hypothesis explicit and discussing the strength of evidence that supports it will provide a more solid foundation for the planned path from outputs to outcomes. Managers and researchers in the clean cooking sector are strongly encouraged to consider incorporating strategies, plans and activities based on behavioral theory, models, experience and research. As part of this, they should report the use of behavior change theories, models and techniques. To assist in this process, a useful tool would be a guide on implementing behavior change in clean cooking interventions.

We identified a journey to scale in which programs reached a tipping point after which the new cleaner cooking technology became the norm. An example is Indonesia's transition to LPG, which experienced significant problems and resistance in the early stages. It was able to learn from these problems and adapt the rollout of the program, including reaching out to change agents in beneficiary communities as part of its socialization activities. This, combined with a strong national regulatory framework, appeared to ensure the conversion program reached the tipping point and national adoption.

The review also highlighted that several successful interventions took into account the various relationships and dynamics, including those at the individual, interpersonal, community and national levels. It appears that it is not enough to address personal perceptions and behaviors; interventions must include activities that reflect the relationships in the household as well as social norms and national regulations. For example, Shell Foundation's Room to Breathe project in India shows that social marketing messages must be convincing for the women who are doing the cooking, as well as to both husband and wife who share the decision making and interact with their communities (Shell Foundation, Citation2013). In contrast, the more top-down interventions, such as India's National Biomass Cookstoves Initiative, did not appear to be based on research or activities designed to deal with behavioral challenges, nor engage local communities in the decision making or solutions for their own problems (Lewis & Pattanayak, Citation2012).

Another aspect of achieving scale is the recruitment of change agents and use of cooking demonstrations, which consistently appeared in many of the studies. The way the products are communicated to the community is important, including consultations with leaders, demonstrations and engagement of sales agents, health workers, and other change agents. Several projects recruited members of the target populations who were early adopters of cleaner cooking technologies and then deployed them as change agents in their communities. PATH's project in periurban Uganda, found that peer led promotion, which involved inviting current users of the intervention stove to speak about their perceptions and experiences with the product at the demonstrations, was an effective strategy to increase stove uptake (Shell Foundation, Citation2013).

Drawing on the team's finding that the identity and self-belief BCT was underrepresented, the role of gender is an important practical and moral consideration. This review found evidence that programs with holistic gender sensitive designs were more effective. One example is the Deepam Scheme to promote LPG connections in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh being implemented through women's self-help groups. There is a growing recognition of the advantages associated with actively involving women at every stage of the cleaner cooking value chain (Hart, Citation2013). However, gender empowerment approaches mostly focus on women and have positioned men as either absent actors or perpetrators of harmful practices. Intervention designs should consider how to work better with men on their terms to fulfill their needs and expectations. These two approaches will ensure a holistic gender strategy that provides benefits for all (Goodwin, Citation2013).

The use of brands has significant promise for this sector because brands enable the grouping of behaviors under one strategic relationship umbrella (Evans et al., Citation2008). A stove has to be at least as good functionally (its intrinsic attributes) as the old one, otherwise all other efforts are more likely to fail—and simultaneous use of multiple stoves (stove stacking) will continue. Also the aspirational and emotional appeal (the extrinsic attributes) of the brand must be strong. While this review did not cover the use of brands specifically, few of the programs reported investment in understanding and improving the relationship between the consumer and their brands. One example of the use of a well-recognized, respected brand to sell cleaner cooking technology comes from Unilever (Citation2012). The company is using their popular food flavoring, Royco, to sell a new charcoal stove in Africa using the same name for their cleaner cook stoves. The use of the Royco brand would likely draw on the trust Unilever has built in its brands in African households.

While the technology (especially stoves and fuels) was not an explicit focus for this study, it is worth emphasizing that the product must be appropriate on several levels for the intended users. Although there are many criteria that could be used to assess products, one useful set is the four product quality signals that have received significant attention in the marketing and economics literature: branding, pricing, physical features, and retailer reputation (Dawar & Parker, Citation1994).

Connected to this concept of getting the technology right is the need to ensure the availability of accessible and appealing financing options. New stoves are often a large investment for the targeted households and therefore creative and realistic ways should be developed to enable and facilitate the purchase. Financing options include subsidies, micro loans, trials and rent-to-own programs. An example comes from the Shell Foundation Room to Breathe project, which initially fell short of the sales momentum needed to achieve scale and impact. The project subsequently negotiated partnerships with microfinance institutions in India and sales increased significantly (Shell Foundation, Citation2013).

The available evidence enabled a description and analysis of the behavior change approaches that are more likely to be successful in cleaner cooking interventions. Effective use of various BCTs as part of multilevel programs, the right product, and understanding of the barriers and benefits to change along the value chain have been shown to play a role in effective interventions that address health, economic and environmental impact. However, clearly absent from many program designs are the use of theories and models of behavior change, adapted to the target audience and local context. Underpinning this design should be strong research methods to track and evaluate the effect, not just in terms of technology disseminated but also in behavior change and impact achieved. The sector would benefit from a practical guide to effectively using behavior change approaches for current and new programs. As the evidence base is built further and different methods tested, we expect behavior change approaches to play a more prominent role as the “special sauce” in cleaner cooking interventions in resource poor settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the people who assisted them with the study. This includes Teljya Oka-Pregel for her contribution to development of the case studies; Eoin Martin for his assistance with tagging and data extraction; and David Lloyd for the design of the final report. The authors also wish to thank the external Quality Review Group (QRG) for their guidance and support. The QRG were independent and volunteer experts in behavior change, clean cooking and research:

Brendon Barnes, Professor, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Nigel Bruce, WHO Consultant & Reader in Public Health, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Michael Dibley, Associate Professor of Public Health, University of Sydney, Australia

W. Douglas Evans, Professor of Public Health and Global Health, George Washington University, USA

Kim Longfield, Director of Research & Metrics, Population Services International, USA

Sumi Mehta, Director of Programs, Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, USA

Debbi Stanistreet, Senior Lecturer, Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

This article is based on a report commissioned by the U.K. Department for International Development (DFID), authored by a team of independent consultants. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of DFID or the QRG members. The case studies selected for this article do not reflect any endorsement of the projects, technologies or organizations involved.

Authors’ contributions: NJG, SEO, KJ and JR conceived the study, designed the methods, supervised the literature review, supervised the analyses and drafted the write-up. NJG, SEO, KJ and JR undertook the literature review and performed the coding. ER, EAF and AB drafted sections and commented on the write-up. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

1The full list of 55 interventions is available separately or as part of the full report at http://tulodo.com/2014/09/26/report-behaviour-change-clean-cooking-interventions/.

2The scorecard is available at http://tulodo.com/2014/09/26/report-behaviour-change-clean-cooking-interventions/.

3The full case studies are at http://tulodo.com/2014/09/26/report-behaviour-change-clean-cooking-interventions/.

References

- Ahmed, K., Awe, Y., Barnes, D. F., Croper, M. L. & Kojima, M. (2005). Environmental health and traditional fuel use in Guatemala. Directions in Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Barnes, B. R. (2014). Behavioural change, indoor air pollution and child respiratory health in developing countries: A review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 4607–4618.

- Barnes, B., Mathee, A. & Thomas, E. (2011). The impact of health behaviour change intervention on indoor air pollution indicators in the rural North West Province, South Africa. Journal of Energy in Southern Africa, 22, 35–44.

- Beltramo, T., Levine, D. I. & Blalock, G. (2014). The effect of marketing messages, liquidity constraints, and household bargaining on willingness to pay for a nontraditional cookstove. Working Paper Series No. WPS-035, Center for Effective Global Action, University of California, Berkeley.

- Biran, A., Schmidt, W.-P., Varadharajan, K.-S., Rajaraman, D., Kumar, R., Greenland, K., … Curtis, V. (2014). Effect of a behaviour-change intervention on handwashing with soap in India (SuperAmma): A cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health, 2, e145–e154.

- Bonjour, S., Adair-Rohani, H., Wolf, J., Bruce, N. G., Mehta, S., Prüss-Ustün, A., … Smith, K. R. (2013). Solid fuel use for household cooking: Country and regional estimates for 1980–2010. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 784–790.

- Bryan, S., Vorn, V., Rozis, J.-F., Baskoro, Y. I., Madon, G. & Brutinelet, M. (2009). Dissemination of domestic efficient cookstoves in Cambodia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: GERES.

- Budya, H. & Arofat, M. Y. (2011). Providing cleaner energy access in Indonesia through the megaproject of kerosene conversion to LPG. Energy Policy, 39, 7575–7586.

- Dawar, N. & Parker, P. (1994). Marketing universals: Consumers’ use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality. Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 81–95.

- DFID. (2014). How to note: Assessing the strength of evidence. London, England: Author.

- Dolan, P. (2010). MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy. London, England: U.K. Cabinet Office.

- Evans, W. D., Pattanayak, S. K., Young, S., Buszin, J., Rai, S. & Bihm, J. W. (2014). Social marketing of water and sanitation products: A systematic review of peer-reviewed literature. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 18–25.

- Evans, W. D., Blitstein, J., Hersey, J. C., Renaud, J. & Yaroch, A. L. (2008). Systematic review of public health branding. Journal of Health Communication, 13, 721–741.

- French, J. (2006). Social marketing: National Benchmark Criteria. London, UK: National Social Marketing Centre.

- Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K. & Viswanath, K. (2008). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Goodwin, N. J. (2013). The other half of the sky: The role of men in international development. The Good Men Project. Retrieved from http://goodmenproject.com/ethics-values/the-other-half-of-the-sky-the-role-of-men-in-international-development

- Goodwin, N. J., O'Farrell, S. E., Jagoe, K., Rouse, J., Roma, E., Biran, A. & Finkelstein, E. A. (2014). The use of behaviour change techniques in clean cooking interventions to achieve health, economic and environmental impact: A review of the evidence and scorecard of effectiveness. London, England: HED Consulting.

- Hart, C. & Smith, G. (2013). Scaling adoption of clean cooking solutions through women's empowerment: A resource guide. Washington, DC: Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves.

- Hoek, J. & Jones, S. C. (2011). Regulation, public health and social marketing: A behaviour change trinity. Journal of Social Marketing, 1, 32–44.

- Jackson, T. (2005). Motivating sustainable consumption: A review of evidence on consumer behaviour and behavioural change: A report to the Sustainable Development Research Network. Guildford, Surrey, United Kingdom: Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Lee, N. R. & Kotler, P. (2011). Social marketing: Influencing behaviors for good. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lewis, J. J. & Pattanayak, S. K. (2012). Who adopts improved fuels and cookstoves? A systematic review. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120, 637–645.

- Lim, S. S., Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Danaei, G., Shibuya, K., Adair-Rohani, H., … Ezzati, M. (2013). A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380, 2224–2260.

- Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K. & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267–286.

- Maio, G. R., Verplanken, B., Manstead, A. S. R., Stroebe, W., Abraham, C., Sheeran, P. & Conner, M. (2007). Social psychological factors in lifestyle change and their relevance to policy. Journal of Social Issues and Policy Review, 1, 99–137.

- Malla, M. B., Bruce, N., Bates, E. & Rehfuess, E. (2011). Applying global cost-benefit analysis methods to indoor air pollution mitigation interventions in Nepal, Kenya and Sudan: Insights and challenges. Energy Policy, 39, 7518–7529.

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., … Wood, C. E. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46, 81–95.

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M. & West, R. (2011). The Behaviour Change Wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, article 42.

- Modi, S. & Firestone, R. (2014). Social marketing evidence base: Methodology and findings. Washington, DC: Population Services International.

- Mugisha, E. (2014). Strategies for improved cookstove adoption in urban Uganda. Retrieved from http://www.tractionproject.org/strategies-improved-cookstove-adoption-urban-uganda

- Pine, K., Edwards, R., Masera, O., Schilmann, A., Marron-Mares, A. & Riojas-Rodriguez, H. (2011). Adoption and use of improved biomass stoves in rural Mexico. Energy for Sustainable Development, 15, 176–183.

- Puzzolo, E., Stanistreet, D., Pope, D., Bruce, N. & Rehfuess, E. (2013). Factors influencing the large-scale uptake by households of cleaner and more efficient household energy technologies. London, England: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Rajakutty, S. & Kojima, M. (2002). Promoting clean household fuels among the rural poor: Evaluation of the Deepam Scheme in Andhra Pradesh. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Shell Foundation. (2013). Social marketing in India: Lessons learned from efforts to foster demand for cleaner cookstoves. London, UK: Author.

- Smith, K. R. (2014). Health and solid fuel use: Five new paradigms. Paper presented at the DFID/Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves/WHO Clean Cooking Conference, London, England, May 1.

- Smith, K. R., Bruce, N., Adair-Rohani, H., Balmes, J., Chafe, Z., Dherani, M. … HAP CRA Risk Expert Group. (2014). Millions dead: How do we know and what does it mean? Methods used in the comparative risk assessment of household air pollution. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 185–206.

- Snyder, L. B., Hamilton, M. A., Mitchell, E. W., Kiwanuka-Tondo, J., Fleming-Milici, F. & Proctor, D. (2004). A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives, 9(6 Suppl 1), 71–96.

- Toba, N. (2013). Clean Stove Initiative Forum Proceedings Asia. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Toba, N., Tuntivate, V. & Tang, J. (2013). Lao PDR—Pathways to cleaner household cooking in Lao PDR: An intervention strategy. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Troncoso, K., Castillo, A., Masera, O. & Merino, L. (2007). Social perceptions about a technological innovation for fuelwood cooking: Case study in rural Mexico. Energy Policy, 35, 2799–2810.

- Valente, T. W. & Pumpuang, P. (2007). Identifying opinion leaders to promote behavior change. Health Education & Behavior, 34, 881–896.

- Unilever. (2012). Sustainable living plan: Africa 2012. Durban, South Africa: Author. Retrived from http://www.unilever.co.za/Images/Africa%20USLP_tcm84-327061.pdf

- Vogel, I. (2012). Review of the use of ‘theory of change’ in international development. London, England: DFID.

- Winrock, I. (2009). Commercialization of improved cookstoves for reduced indoor air pollution in urban slums of Northwest Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Winrock International.

- World Bank. (2010). Improved cookstoves and better health in Bangladesh: Lessons from household energy and sanitation programs. Washington, DC: Author.

- World Bank. (2015). Country and lending groups. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups

- World Health Organization. (2010). Guidelines for indoor air quality: Selected pollutants. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

- World LPG Association. (2005). Developing rural markets for LP gas: Key barriers and success factors. Paris, France: Author.