ABSTRACT

The European North has long attracted travelers, the selling point often being the availability of nature and wilderness. Recent developments, however, suggest a greater variety of tourism motivations, including new products such as dogsled tours, aurora borealis watching, snowmobiling, and stays at ice hotels. Many of these firms use names containing the term ‘Arctic' or similar terminology related to imaginations of the Far North. The chosen terminology is considered one example of the process of ‘Arctification'. However, there is a limitation in descriptive knowledge about the overall Arctification of the region’s tourism industry. Hence, this article aims to illustrate the Arctification of the tourism industry by mapping the changing geographies of firm names. Through its results, the study aims to contribute an understanding of how firm naming is part of the tourism production, and how this influences the reimaging and delineation of regions. The study uses a descriptive quantitative approach, extracting data from the Retriever Business database. The results show a clear development of tourism firms increasingly using Arctic terminology in their firm names. Also, the tourism firms’ locations show patterns of spatial differences related to the region’s natural environment, population density, infrastructure, and the firms’ age.

Introduction: the Arctification of northern tourism

The European North above the Arctic Circle has attracted travelers and tourists for more than a hundred years (Jacobsen, Citation2015). The selling point of the North has been the availability of nature and wilderness, accessible and commodified for touristic consumption (Müller, Citation2011; Müller et al., Citation2019; Saarinen, Citation2019). Hence, Pedersen and Viken (Citation1996) argue that the European North has become a global playground, or as Saarinen (Citation2005) expresses it, a touristic wilderness. While Jacobsen (Citation2015) still sees the European North as a destination for anti-tourists, looking for uniqueness and distance from the masses, the recent tourism development suggests a greater variety of tourist motivations and travel modes. Indeed, places such as the North Cape, Norway or the Santa Claus Village in Rovaniemi, Finland, have triggered seasonal mass tourism (Grenier, Citation2007; Herva et al., Citation2020; Müller et al., Citation2020; Rantala et al., Citation2019). At the same time, new products such as dogsledding tours, Aurora Borealis watching, snowshoe walks, and stays at ice hotels have been introduced to the regional tourism supply, often turning it toward ‘softer' and more accessible experiences alongside a more traditional supply focusing on regional demand (Granås, Citation2018; Hjalager et al., Citation2008; Jæger & Viken, Citation2014; Jóhannesson & Lund, Citation2017; Rantala et al., Citation2018). This development is in line with reports of growing tourism in northern areas and the Arctic (Hall & Saarinen, Citation2010; Müller, Citation2015; Varnajot, Citation2020), at least until the COVID-19 pandemic caused a discontinuation of the long-lasting boom. Saarinen and Varnajot (Citation2019) reviewed different perspectives on Arctic tourism in the scientific literature analogous to Wang’s (Citation1999) dimensions of authenticity and acknowledged that there is no consensus on how the Arctic region should be delineated. Although this has greatly contributed to understanding various dimensions of Arctic tourism, the authors do not explain the emergence of Arctic tourism in places previously not considered being located in the Arctic, and the question of what such a change means for the places where it is conducted remains unanswered. ‘Arctification’ has been identified as a contributing factor to tourism growth in the north (Lundmark et al., Citation2020). Müller and Viken (Citation2017) define the Arctification process as being ‘a social process creating new geographical imaginations of the north of Europe as part of the Arctic and consecutively new social, economic and political relations of the area'. (ibid, 288). For example, Müller et al. (Citation2020) acknowledged that this process has led tourism- and hospitality entrepreneurs even in urban areas to use ‘Arctic’ as part of their brands. The Arctification process here refers to the idea of adapting natural and constructed symbols, names and associations that are used to represent the Arctic, many of which are based on historical and/or stereotypical images of the region (cf. Cooper et al., Citation2019; Rantala et al., Citation2019; Viken, Citation2013). Hence, this article aims to illustrate the Arctification of the tourism industry by mapping the changing geographies of firm names. Through this descriptive study, it is possible to assess what type of words, and where these Arctic firm names are used, as this contributes to understanding the role of naming and language in creating and delineate Arctic places and Arctic tourism activities.

Theoretical background

Overall, tourism and globalization have led to a continuous spatial integration within and between places in the form of flows of people, information, knowledge, and capital (Dicken, Citation2007). For example, some researchers suggest that the increased media attention to the Arctic has sparked the phenomenon of ‘last chance tourism', referring to tourists travelling to experience places and things before they change or disappear, often related to climate change (Lemelin et al., Citation2010). This type of increased flow of information has also created a global environment in which ‘even the most remote spaces are exposed to global competition and are forcing firms, localities and regions to react and adjust to the new economic condition' (Pike et al., Citation2006, p. 4). One adaptation to the global competition, especially in tourism, involves various types of marketing and branding strategies. The end goal of marketing and place branding is to shape the identity of a place from within, to emit a favorable image that resonates with the place identity and creates a positive reputation (Boisen et al., Citation2018). For a region, place, or tourism site it is vital to be spatially limited, with clearly defined borders, to produce and market it for tourism purposes (Paasi, Citation1986; Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). However, the identity or imagination of a place in tourism varies between tourism entrepreneurs, who produce the products, and tourists seeking their own identity through their experience with the products (MacCannell, Citation1976; Wang, Citation1999). In the Arctic region, producers of tourism have materialized naming, branding, and marketing through the development of tourism destinations, firms, and products that have emerged over time. Many have themed their products as ‘Arctic', promoting themselves as exotic and out of the ordinary to attract tourists (Grenier, Citation2007; Jacobsen, Citation1997; Lucarelli & Heldt Cassel, Citation2019; Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019; Viken & Granås, Citation2014). The changes in the Arctic region have created a new meaning for it as a place of rich culture, social life, and a variety of flora and fauna, rather than simply a remote, barren wilderness (Müller, Citation2015). The social process, sometimes called the Arctification of the Arctic region, has thus led to new social, economic, and political relations and effects (Müller & Viken, Citation2017). Human geographers often study these socioeconomic forces and/or the material processes that follow, without explicitly highlighting the importance of language and naming (Tuan, Citation1991). In human geography, names can be interpreted as part of research related to imaginaries (Salazar, Citation2012). In tourism geography, however, much more attention has been given to place branding (Heldt Cassel, Citation2008; Hospers, Citation2004; Lucarelli, Citation2018; Syssner, Citation2010). This is a form of socioeconomic thinking, and has its roots in business research in areas like marketing and branding (Anholt, Citation2008). Yet, names themselves often become major symbols and an essential part of place identity (Paasi, Citation2010), as ‘naming is power – the creative power to call something into being' (Tuan, Citation1991, p. 688). In tourism, the process of naming a tourist site or an attraction is considered essential for displaying it (MacCannell, Citation1976), as a tourist site or attraction with high ‘imageability' will appeal to tourists and attract them to visit it (Jacobsen, Citation1997). Hence, naming is crucial in the production of place and place-making, often resulting in a social reproduction whereby areas or institutions are named after the tourism attraction or tourism sites (MacCannell, Citation1976). Still, Light (Citation2014) states that:

Academic geographers have a long history of studying both tourism and place names, but have rarely made linkages between the two. Within critical toponymic studies there is increasing debate about the commodification of place names but to date the role of tourism in this process has been almost completely overlooked. (ibid, p. 141)

Toponymy is the study of place names, and is studied in linguistic research, where words and naming have been acknowledged as important, major contributions to the (re)production and (re)imagining of places (Andersson, Citation2017). Toponyms can be viewed as ‘markers', in the words of MacCannell (Citation1976), and some tourism studies have studied toponyms, including the Hollywood sign and Hollywood boulevard in America (Braudy, Citation2011), indigenous tourism sights in Australia (Clark, Citation2009), street names in Israel (Shoval, Citation2013), and Route 66 in America (Caton & Santos, Citation2007). Among the related toponym studies, Mair (Citation2009) studied the place of Vulcan in West Virginia, whose name was chosen as a reference to the popular TV show Star Trek. Mair’s (Citation2009) research provides a good case example of a successful instance of a place name being changed to attract tourism. The opposite has also been found, with a place name generating expectations among tourists that have not been fulfilled, resulting in various negative impacts such as vandalism (cf. Clark, Citation2009). Another example is the study by Pedersen (Citation2016) in Kaldefjord a few kilometers outside Tromsø, Norway. The study focused on a language change in place names from Sami to Norwegian. In the paper, Pedersen questions whether the process has given the place a new Norwegian identity through a stigmatization of the Sami language. These case studies on toponyms demonstrate the power of names and naming. No previous studies have been found that similarly analyse tourism firm names, although naming has been viewed as important in tourism research (Caton & Santos, Citation2007; Jacobsen, Citation1997; MacCannell, Citation1976; Shoval, Citation2013). The understanding and meaning of naming, symbols and signs are crucial in linguistic studies to understand its impact (Bourdieu, Citation1991). One common theory is that of signified and signifier, introduced by de Saussure among others (Chandler, Citation2017). Similar, in tourism research, MacCannell (Citation1976) idea builds on the idea that tourists’ first interaction with a destination or sight is not with the sight itself, but rather a representation of it. Through images, text or stories the tourist develops various ideas and perceptions of the sight. This idea is part of MacCannell’s sight sacralization framework, where the first step is identifying and differentiating the sight from other sights by defining, delineating and naming it. According to Pretes (Citation1995) the representation of the sight is thus transformed into something that can be packaged, marketed, sold and also reproduced by the tourists. By researching the Arctification of tourism firm names in this study, the aim is to contribute to the understanding of the development of Arctification and the production of space through naming, and the role of tourism in reimaging regions, by acknowledging Tuan’s (Citation1991) argument of the importance of language and names: ‘it rests on the fact that words – names, proper names, taxonomies, descriptions, analyses, and so on – can for a start, draw attention to things: aspects of reality hitherto invisible, because unnoticed, become visible' (ibid, pp. 692–693).

Methods and data

Firstly, this study applies an explorative approach in describing the development of the Arctification process among tourism firms in northern Sweden. Hence, the study’s geographical analysis is set on a regional level, comprising the two northernmost counties in Sweden – Norrbotten and Västerbotten (see ) – which are both defined by the Swedish government as Sweden’s Arctic region (Regeringskansliet, Citation2020). The DMO of Norrbotten county, Swedish Lapland, has also highlighted the Arctic as a brand (cf. Lucarelli & Heldt Cassel, Citation2019) and this study highlights the spatial diffusion of this type of naming and branding within the region and between the counties. As there is a lack of basic descriptive knowledge regarding the overall Arctification in the tourism industry, the study uses a descriptive quantitative approach, laying out the historical path and the current state of Arctic-related names used, to paint a broad picture of the development. By focusing on firms in the tourism industry, the study addresses the Arctification process from a supply-side perspective, hence not taking into account individual tourists, or the demand side. The justification for this is grounded in the assumption that firms are the most important actors in decisions regarding not only offering specific products in the marketplace, but also how firms should be profiled and named, and how they are intended to be perceived among potential customers. Further, firms and their market offers are indirectly a response to market demand, hence partly considering the demand side. This means that, even though specific considerations and choices made by key individuals within different firms would be of interest, this is not the primary focus in this study.

The data used in this study are extracted from the Retriever Business financial database, owned and run by the private firm Retriever Sverige AB (Retriever Business, Citation2020). This database is a collection of public financial and business-related information regarding all limited companies, economic associations, sole traders, and trading partnerships in Sweden. It collects information from private credit institutes and public government authorities such as the Swedish Companies Registration Office (Bolagsverket), the Swedish Tax Agency (Skatteverket), and Statistics Sweden (Statistiska centralbyrån). Hence, the included data comprise public information collected from several different sources but stored and searchable in a single database comprising around 300 different variables for each firm (Retriever Business, Citation2020). The central piece of information for this study is the firm name used for a firm and/or association. The name of the firm is the key indicator used for tracking the Arctification process in the region. While this says nothing regarding the products offered, it is an important indicator of how the firm is profiled and how it is intended to be perceived, offering one insight into the intentions among its owners and founders, and/or key individuals within the firm. One limitation, of course, is that the firm name does not completely reveal the firm’s core operations, but it serves as a proxy for its operating activities and gives an overview of the Arctification process in the region over a long period. The firms included in this study are limited companies, economic associations, sole traders, and trading partnerships, which are the most common forms of economic firms within the Swedish system (Bolagsverket, Citation2020). To describe the development of the Arctification of economic firms, all firms registered from January 1, 1945 to January 1, 2019 (including non-active and deregistered firms) were analyzed. As the standard industrial classification codes (SIC) in Sweden do not include the tourism industry as a separate branch, definitions regarding what is and is not tourism must be created. In this paper we have uses a narrow definition of the tourism industry previously suggested by Lundmark (Citation2006). Firms belonging to the following categories are defined here as the tourism industry (see ):

Table 1. Definition of the tourism industry according to standard industrial codes. Source Retriever Business, Citation2020.

This means that large economic sectors that are an essential part of the tourism industry but are primarily not defined as such are not included. One example is the retail sector, which is the target of a large part of the annual tourism expenditure (Tillväxtverket, Citation2020). To distinguish and determine the scope of the Arctification process in the region, different keywords signifying Arctic-related names and terms in the economic firms must be selected. In this study, the terms chosen to indicate an Arctification of the tourism industry are winter, ice, snow, and other natural features of the region. As this study does not focus on the products offered but rather on the profiling of the economic firms, one needs to base the terms on the main natural resource highlighted in the names. Hence, in line with Grenier (Citation2011), the selected associated terms represent the Arctification. In this study, terms in Swedish and English language are selected (see ):

Table 2. Selected keywords in firm names as indicators of Arctification.

Given the scope and time depth of the data used, the chosen approach provides an extensive picture of more than half a century of development in the northernmost region, and will essentially answer whether or not there is an Arctification process at hand. Before the empirical evidence is presented, a short background of tourism development will illustrate the study’s geographical context.

Tourism in northern Sweden

Tourism in northern Sweden can be dated far back in time, and one may argue that Linnæus’s (Citation2005/1732) Iter Lapponicum is an early travel diary recounting his time in the country’s North. However, a more widespread tourism development took place in the second half of the nineteenth century, when the construction of a railway facilitating the exploitation of northern resources also allowed tourists to access the North (Lundgren, Citation1995; Müller et al., Citation2019). The Swedish Tourist Association, established in 1885, promoted tourism to the northern mountain range in a nationalist spirit and provided a network of cabin and huts, allowing tourists from southern Sweden to explore the exotic North (Hagren, Citation2020). Modernization and the establishment of the welfare state further promoted tourism by including broader sections of society (Bohlin et al., Citation2014). The right to paid vacation was the first step in developing social tourism. In the North particularly, the mountain range offering skiing and hiking was identified as an area of national interest for tourism and recreation (Müller et al., Citation2019). Indeed, tourism developed into an important economic activity in the North; and particularly from the late 1980s onward, when the global neoliberal shift hampered the direct involvement of the state, tourism development was promoted to counterbalance the negative impacts of globalization on the peripheral North, including deindustrialization, selective outmigration, and an ageing population (Bohlin et al., Citation2016; Müller, Citation2013; Müller et al., Citation2019). This development triggered a rejuvenation of tourism. The establishment of the Icehotel in Jukkasjärvi outside Kiruna was soon accompanied by other investments in a variety of tourism products, often focusing on the winter season (Müller, Citation2011). The number of commercial overnights stays in Västerbotten and Norrbotten, Sweden’s two northernmost counties, increased from 3.7 million in 2012 to more than 4.3 million in 2018, a significant increase even in a circumpolar comparison (Varnajot, Citation2020). Much of this increase, however, has taken place in urban centers rather than rural peripheries, although a spillover of an often exclusive and international demand into adjacent rural areas can be detected (Müller et al., Citation2020). Naturally, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected demand. However, the high-end tourism to many of the new tourism attractions promising exclusive experiences close to nature, and often framed around an Arctic topic, has hitherto not been reported to have dwindled dramatically.

Empirical evidence

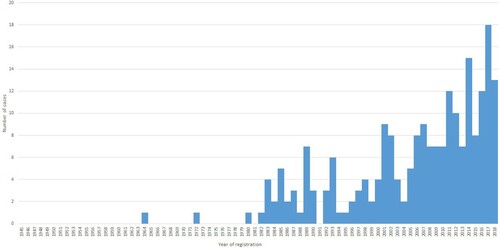

Firstly, the development of a possible Arctification process among economic firms in the tourism industry in the counties of Norrbotten and Västerbotten will be described using official register data from (Retriever Business, Citation2020). Secondly, the places signified by a possible Arctification process will be identified and described, using GIS analysis. Regarding the development of an Arctification process, the Retriever Business database allows a search of firms and economic associations as far back as 1945. This offers an extensive overview of how this has developed over a period of more than half a century. , below, presents the development of firms and economic associations in the tourism sector with Arctic-related names in Norrbotten and Västerbotten. This covers all firms and economic associations active from January 1, 1945 to January 1, 2019, and includes firms that today are non-active and/or deregistered. Hence, this is the gross figure of all firms that have operated during this period. As shown in , the first firm or economic association with an Arctic-related name first appeared in 1964: This was a firm with the term ‘Lappland’ in its company name. Other important terms then make their debuts, such as ‘Is/Ice' in 1982, ‘Snö/Snow' in 1983, ‘Arktis/Arctic' in 1984, ‘Slädhund/Husky' in 1986, both ‘Norrsken/Aurora' and ‘Pol/Polar' in 1987, and finally ‘Vinter/Winter' in 1998.

Figure 2. Registered tourism firms, associations, and organizations with Arctic-related names in the counties of Norrbotten and Västerbotten, Sweden. Time frame January 1, 1945-January 1, 2019. Non-active & deregistered firms included. Source: Retriever Business, Citation2020.

Throughout the period, there was a total of 218 firms and economic associations with Arctic-related names. During the 1960s and 70s there were few tourism firms and/or economic associations in the region with Arctic-related names, and it was not until the 1980s that things started to develop. In the 1980s 26 Arctic tourism firms were added, and the figure for the 1990s is 25. Then, things took off in the early 2000s and 63 Arctic-related firms appeared, increasing to 102 in the 2010s. These are crude numbers, and are not accounting for larger changes in the regions, such as a general increase in international tourism (Varnajot, Citation2020), increase in international entrepreneurs in the region (Carson et al., Citation2018; Carson & Carson, Citation2018), and other types of political change (cf. Väätänen & Zimmerbauer, Citation2020), which is outside the scope of the present explorative, descriptive study. However, they do indicate an increase in the frequency of Arctic naming among the region’s tourism firms, with more and more of them taking this path, among many, in choosing what to communicate to the market.

The numbers of tourism firms (with Arctic and non-Arctic names) are rather evenly distributed between the two counties during the period. In Norrbotten the gross figure for the period regarding all tourism firms and economic associations is 1222 while the same figure for Västerbotten is 1054, giving a ratio of 54% of all firms in Norrbotten and 46% in Västerbotten. The Arctic-related tourism firms constitute approximately 10% of all tourism firms during the period, but their share was slightly higher during the 1980s (26%). However, what is crucial for this study are the absolute numbers since these indicate a growing number of entrepreneurs who deliberately label their firms with names carrying an Arctic connotation. The distribution of Arctic-related tourism firms between the two counties is somewhat skewed. A total of 175, or some 80% of all tourism firms with Arctic names, are located in Norrbotten during the same period, meaning that the remaining 43 (19.7%) are located in Västerbotten. This is somewhat logical, as Norrbotten is the more northern county of the two, and holds features iconic tourism attractions focusing on Arctic-related features. It is further interesting to break down the different terms used in the naming of tourism firms and economic associations, and describe how they differ between the two counties. In the Arctic names are broken down into individual keywords, in both Swedish and English, for the two counties. Most of the Arctic terms used for firm and association names are phrased in English. Some 72.4%, or 158 firms and associations, use English Arctic-related names, compared to 27.6% or 60 firms using Swedish terms. This is of course an indication of the international geographical markets these firms are primarily targeting in their quest. Among the Swedish terms, ‘Lappland' (English Lapland) is the most frequent, followed by Pol (English Pole or Polar). Some 65% of the Swedish Arctic-related terms used are used by firms and economic associations in Norrbotten. However, as for the terms ‘Snö' (Snow), ‘Slädhund' (Husky) and ‘Lappland' (Lapland), there is an overweight for Västerbotten. The term ‘Pol' (Pole or Polar) only occurs in Norrbotten.

Table 3. Tourism firms, associations, and organizations with Arctic-related names in the counties of Norrbotten and Västerbotten, Sweden. Registered from January 1, 1945 to January 1, 2019. Non-active and deregistered firms included. Source: Retriever Business, Citation2020.

Regarding the English terms (158 cases), 86% (136) are in Norrbotten and merely 14% (22) in Västerbotten. All of the English terms have a higher frequency in Norrbotten. The most commonly used term is ‘Lapland' (64), followed by ‘Arctic' (48) and ‘Husky' (13), meaning that ‘Lapland/Lappland' is the most common term in both English and Swedish. In English ‘Arctic' is the second-most common term, but the Swedish term (Arktis) appears far down in the hierarchy, indicating the importance this profiling has on an international market. For English terms, Norrbotten is at the top of all terms accounted for. In the case of the term ‘Arctic', 47 out of 48 firms and economic associations are located in Norrbotten. Hence, measured by name indicators, the Arctification process is found primarily in Norrbotten, and here the profiling is targeting primarily an international (English-speaking) market.

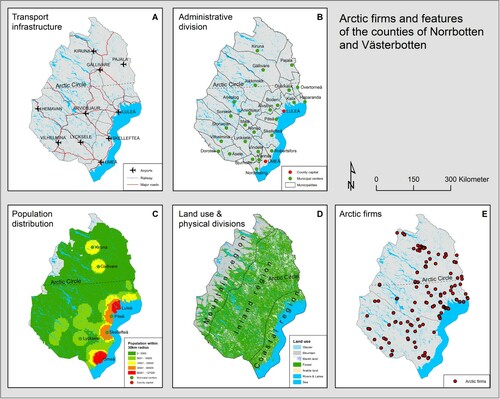

Further, in analyzing places signified by the Arctification process, a basic GIS analysis is used. Here, only firms that are active on January 1, 2019 are included. The total number of Arctic firms in the region at this time is 192. These are plotted and related to basic and relevant features of firms in the tourism industry, to describe these places and their characteristics. Population density as well as land-use and physical geography divisions are also used as input. (A–D) displays central features of the research area and (E) the distribution of the Arctic tourism firms.

Figure 3. Features of the counties of Västerbotten and Norrbotten, including Arctic firm locations. Source: Retriever Business, Citation2020.

All maps in (A–E) display the location of the Arctic Circle, which runs through Norrbotten county, in an east–west direction. (A) shows the distribution of airports in the region. There are currently ten airports with scheduled air services, which naturally differ in size regarding passenger volume and number of daily flights. The airports in Umeå, Luleå, and Kiruna have the highest passenger numbers and are operated and owned by Swedavia, a state-owned airport company. Other airports are owned and operated by companies solely or partly owned by the respective municipalities. The administrative division in the region shows that there are 29 municipalities ((B)) in the region, including the county capitals of Umeå (Västerbotten) and Luleå (Norrbotten). Many of the municipalities are sparsely populated. As displayed in (C), most of the area has a total population volume (within a 30 km radius) below 5000 inhabitants; it is only in the coastal area where the population volume is relatively high. Also, there are two population hot spots (Kiruna and Gällivare) in the inland of Norrbotten, with a moderate population volume. The land-use and physical divisions of the region are displayed in (D), showing that the mountain region, with its Arctic tundra-like vegetation, is aligned along the border to Norway. The inland region, dominated by boreal forest, is the largest type of area. Finally, the coastal region is the smallest in size but the largest in terms of population. Finally, in (D), the Arctic firms are plotted. What, then, are the characteristics of the localities where Arctic tourism firms have appeared? First, the distribution of the aggregated distances between the Arctic tourism firms and some of the features, mentioned in , are analyzed. These distances are shown in box plots in , sorted in descending order.

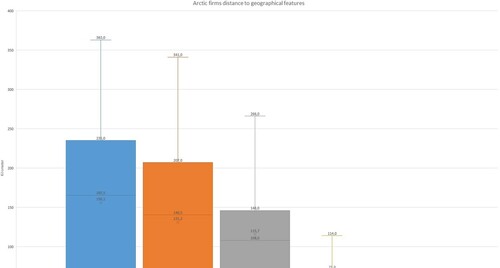

Figure 4. The distribution of aggregated distances between Arctic tourism firms and important features in the county of Västerbotten and Norrbotten.

The spatial proximity to the county capitals of Umeå and/or Luleå seems to be of low importance in explaining the locality of Arctic tourism firms in the region. Of course, some are located in the respective county capital or close by, but most are not. Regarding the distance to the sea, this is of higher importance than the county capital; but still, the median distance is 140.5 km. The Arctic Circle seems to be of greater importance for the spatial location of Arctic tourism firms in the region. However, the median is still over 100 km. What seems to be important, rather, is spatial proximity to an airport. Here the median distance is merely 35.5 km, which means that 50% of the Arctic firms are located no further from an airport than a 30-minute drive. The variation in the data is also rather low, with an interquartile range between 7.3 and 71 km. The extreme case is 114 km from the closest airport. Most important when it comes to location, however, is proximity to a municipal center. This is the case, of course, due to the number of municipal centers; but it also indicates that Arctic tourism firms are not placed in total wilderness, at least not most of them. Rather, proximity to the amenities and services found in central places seems to be important to the firms. Here, the median distance to the municipal centers is only 9.7 km. Finally, the localities and the characteristics of the surroundings of the Arctic tourism firms are analyzed based on the firms’ age, in order to describe what has been of importance in their choice of location over time. In , the Arctic firms are divided based on different age intervals. This mirrors , with most of the firms appearing in recent years: Over 50% of them have started their business in the past ten years. If we look at the population volume of the surrounding firms we see that younger ones have been located in areas closer to population centers, whereas the old firms (over 30 years.) to a greater extent were located in the rural periphery, with low population numbers. This is partly also the case regarding the number of other Arctic tourism firms. The oldest firms have a low number of other firms in the surroundings, while the most recent ones have a higher density. This indicates that while the Arctic label previously has been a signifier for remote places, it is now also increasingly present in urban environments (Müller et al. Citation2020).

Table 4. Arctic firms categorized by age and the characteristics of the locational surroundings.

Regarding the type of region, it is clear that most firms are located in the inland region. This is by far the largest region, and there are significant numbers of Arctic tourism firms surrounding the larger settlements. For example, within a radius of 20 km from the city of Kiruna there are 30 Arctic tourism firms, making up the largest Arctic tourism firm cluster in the entire region. This area also holds one of the most iconic Arctic tourism firms in Sweden, the world-famous Icehotel (see www.icehotel.com), first constructed in 1989.

Discussion

The empirical data on the region demonstrate an increase in tourism firms using various forms of ‘Arctic' terminology in their names. While the reasoning behind the use of these names is not addressed in this study, previous studies have shown that the Arctic region has been viewed as exotic and out of the ordinary (cf. Viken & Granås, Citation2014). The Arctic names can be interpreted as exotic and unique in response to tourists’ image of the region, as being exotic or out of the ordinary is expected to appeal to tourists (Wang, Citation1999). Hence, one could argue for the importance of naming a firm in such a manner to attract tourists, as an attractive ‘marker' or name will appeal to them and encourage them to visit (MacCannell, Citation1976). The empirical data show that the tourism firms with these Arctic names are spatially located both north and south of the geographical borders, for example the Arctic Circle, natural borders, and regional borders (Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). Still, these places contain material and immaterial elements that reflect the image tourists might have of the Arctic, including snow, cold, wilderness, the northern lights, midnight sun, etc. The reasoning behind these findings could be that ‘the image of the North is to a large extent determined by the visitors from the south' (Jacobsen, Citation1997, p. 346). Hence, the tourism entrepreneurs in this study may choose a particular name for their firm to meet the expectations of tourists; or, they might choose a particular name to attract tourism (Mair, Citation2009). This development has not spilled over into the changing of place names in the region, but has been seen in other non-tourism firms, e.g. Polarbröd (Polar Bread), Polarfönster (Polar Windows), Arctic Road and Polarvagnen (Polar Caravan). It is, however, observed in the political arena, for example, the Swedish Arctic strategy (cf. Müller, Citation2021) and in local DMO strategies such as the one of Swedish Lapland (Lucarelli & Heldt Cassel, Citation2019). It is evident from the results that many of these tourism entrepreneurs use English terminology in their firm names, which could be interpreted as an awareness of the global geopolitical discourse around the Arctic region (Lucarelli & Heldt Cassel, Citation2019). Including the discourse on last chance tourism (Lemelin et al., Citation2010), the use of an Arctic name and English terminology would enable tourism entrepreneurs to have their firm names be understood globally, and appeal to these types of tourists seeking an Arctic experience. The names could also be interpreted as an adaptation to the global competition of firms and places (Hospers, Citation2004; Pike et al., Citation2006; Syssner, Citation2010), similar to the use of place branding (Boisen et al., Citation2018). The Arctification of the Arctic region, has led to new social, economic, and political relations and effects (Müller & Viken, Citation2017). Part of it this is the regional brand that will partly shape the regions’ development and symbolic values (Syssner, Citation2010). Similarly, this paper argues that naming particular tourism firms is a vital part of the production of space. Tourism firm names are an important symbolic capital that can influence tourists’ perception of a place, by default influencing the production of space to meet the needs of tourists on a broader societal level.

Conclusion

The results in this study demonstrate that tourism entrepreneurs label their firms as being Arctic, even though some of the firms’ spatial locations are south of most of the existing geographical, political, and natural borders of the Arctic (Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). These findings demonstrate Saarinen and Varnajot’s (Citation2019) idea of the produced and experienced dimensions of delineating a region. The produced dimension refers to the tourism production that is based on sociocultural and natural images of the region, and the experienced dimension specifies the tourists’ subjective experiences (ibid). The findings suggest that the ‘Arctic’ can still be produced and experienced outside the existing borders and indeed, the firm names contribute to reimagine the spatial delimitation of, and attributes associated with the Arctic region. These findings support Cooper et al. (Citation2019) claim, whom state that ‘In tourism studies, there is no sound geographical definition of where the Arctic begins' (p. 78).

Furthermore, the findings show that younger firms tend to be spatially located closer to airports and urban areas compared to their older counterparts, while the Arctic label previously has been a symbol for remote places associated with wilderness and emptiness (Müller & Viken, Citation2017). These findings provide empirical evidence for the argument presented by Müller et al. (Citation2020) that the Arctic and its imagined properties increasingly are to be found in urban environments within the northern region, too. A possible explanation is that tourism entrepreneurs respond to the increasing interest of international tourists for the Arctic. Consequently, they locate their operations close to access points for international charter flights and urban environments, securing access to supportive services and infrastructure (Lundmark & Carson, Citation2020). This also explains the increase of English terminology used in the firm names found in this study. However, as previously stated by others, the Arctification process might not be perceived to be beneficial by all. It can be seen as an orientation towards the expectations and needs of stakeholders outside the region and not necessarily corresponding to local community needs (Cooper et al., Citation2019; Rantala et al., Citation2019). Hence, further studies of the Arctification process and its societal impacts are suggested. Additionally, the study underlines a need to investigate language in tourism to gain a deeper understanding of its role for meaning creation, and eventually its influence on societal structures in a case where global discourses on the Arctic collide with local practices, narratives, and traditions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersson, D. (2017). Ortnamnens funktioner i flerspråkiga områden. In L.-E. Edlund, & E. Strzelecka (Eds.), Mellannorrland i centrum: Språkliga och historiska studier tillägnade professor Eva Nyman (pp. 131–142). Skytteanska Samfundet.

- Anholt, S. (2008). Place branding: Is it marketing, or isn’t it? Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000088

- Bohlin, M., Brandt, D., & Elbe, J. (2014). The development of Swedish tourism public policy 1930-2010. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 18(1), 19–39. https://ojs.ub.gu.se/index.php/sjpa/article/view/2753

- Bohlin, M., Brandt, D., & Elbe, J. (2016). Tourism as a vehicle for regional development in peripheral areas – myth or reality? A longitudinal case study of Swedish regions. European Planning Studies, 24(10), 1788–1805. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1194807

- Boisen, M., Terlouw, K., Groote, P., & Couwenberg, O. (2018). Reframing place promotion, place marketing, and place branding - moving beyond conceptual confusion. Cities, 80(2018), 4–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.021

- Bolagsverket. (2020). Jämför företagsformer. https://bolagsverket.se/ff/foretagsformer/valja-foretagsform.

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Polity Press.

- Braudy, L. (2011). The Hollywood sign: Fantasy and reality of an American icon. Yale University Press.

- Carson, D. A., & Carson, D. B. (2018). International lifestyle immigrants and their contributions to rural tourism innovation: Experiences from Sweden's far north. Journal of Rural Studies, 64, 230–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.004

- Carson, D. A., Carson, D. B., & Eimermann, M. (2018). International winter tourism entrepreneurs in northern Sweden: Understanding migration, lifestyle, and business motivations. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1339503

- Caton, K., & Santos, C. A. (2007). Heritage tourism on route 66: Deconstructing nostalgia. Journal of Travel Research, 45(4), 371–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507299572

- Chandler, D. (2017). Semiotics: The basics. Routledge.

- Clark, I. D. (2009). Naming sites: Names as management tools in indigenous tourism sites – An Australian case study. Tourism Management, 30(1), 109–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.03.012

- Cooper, E. A., Spinei, M., & Varnajot, A. (2019). Countering ‘Arctification’: Dawson citys ‘Sourtoe Cocktail’. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2019-0008

- Dicken, P. (2007). Global shift: Mapping the changing contours of the world economy. Sage.

- Granås, B. (2018). Destinizing Finnmark: Place making through dogsledding. Annals of Tourism Research, 72(2018), 48–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.05.005

- Grenier, A. A. (2007). The diversity of polar tourism: Some challenges facing the industry in Rovaniemi, Finland. Polar Geography, 30(1–2), 55–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10889370701666622

- Grenier, A. A. (2011). Conceptualization of polar tourism: Mapping an experience in the far reaches of the imaginary. In A. A. Grenier, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Polar tourism: A tool for regional development (pp. 61–86). Presses de I’Univeristé du Québec.

- Hagren, K. I. (2020). Nature, modernity, and diversity: Swedish national identity in a touring association’s yearbooks 1886–2013. National Identities, 23(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2020.1803819

- Hall, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2010). Polar tourism: Definitions and dimensions. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(4), 448–467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.521686

- Heldt Cassel, S. (2008). Trying to be attractive: Image building and identity formation in small industrial municipalities in Sweden. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4(2), 102–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000086

- Herva, V. P., Varnajot, A., & Pashkevich, A. (2020). Bad santa: Cultural heritage, mystification of the Arctic, and tourism as an extractive industry. The Polar Journal, 10(2), 375–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2020.1783775

- Hjalager, A.-M., Huijbens, E., Björk, P., Nordin, S., Flagestad, A., & Knútsson, Ö. (2008). Innovation systems in Nordic tourism. Technology Analysis Strategic Management, 12(4), 289–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4765.1202

- Hospers, G.-J. (2004). Place marketing in Europe: The branding of the Oresund region. Intereconomics, 39(5), 271–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03031785

- Jacobsen, J. K. S. (1997). The making of an attraction: The case of North Cape. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 341–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(97)80005-9

- Jacobsen, J. K. S. (2015). The North Cape: In the land of the midnight sun. In N. Herrero, & S. R. Roseman (Eds.), The tourism imaginary and the pilgrimage to the edges of the world (pp. 120–140). Channel View Publications.

- Jæger, K., & Viken, A. (2014). Sled dog racing and tourism development in Finnmark: A symbiotic relationship. In A. Viken, & B. Granås (Eds.), Tourism destination development (pp. 131–150). Ashgate.

- Jóhannesson, G. T., & Lund, K. A. (2017). Aurora Borealis: Choreographies of darkness and light. Annals of Tourism Research, 63(2017), 183–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.02.001

- Lemelin, H., Dawson, J., Stewart, E. J., Maher, P., & Lueck, M. (2010). Last-chance tourism: The boom, doom, and gloom of visiting vanishing destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 477–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500903406367

- Light, D. (2014). Tourism and toponymy: Commodifying and consuming place names. Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 141–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.868031

- Linnæus, C. (2005/1732). Iter lapponicum. Facsimile edition. Kungliga Skytteanska Samfundet.

- Lucarelli, A. (2018). Place branding as urban policy: The (im)political place branding. Cities, 80(2018), 12–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.004

- Lucarelli, A., & Heldt Cassel, S. (2019). The dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding: Conceptualizing regionalization discourses in Sweden. European Planning Studies, 28(7), 1375–1392. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1701293

- Lundgren, J. O. (1995). The tourism space penetration processes in northern Canada and Scandinavia: A comparison. In C. M. Hall, & M. E. Johnston (Eds.), Polar tourism: Tourism in the Arctic and Antarctic regions (pp. 43–61). Wiley.

- Lundmark, L. (2006). Restructuring and employment change in sparsely populated areas: Examples from northern Sweden and Finland. Umeå University.

- Lundmark, L., & Carson, D. A. (2020). Who travels to the North? Challenges and opportunities for tourism. In L. Lundmark, D. B. Carson, & M. Eimermann (Eds.), Dipping into the North: Living, working and traveling in sparsely populated areas (pp. 265–285). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lundmark, L., Müller, D. K., & Bohn, D. (2020). In press). Arctification and the paradox of overtourism in sparsely populated areas. In L. Lundmark, D. B. Carson, & M. Eimermann (Eds.), Dipping into the North: Living, working and traveling in sparsely populated areas (pp. 379–371). Palgrave Macmillan.

- MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. University of California Press.

- Mair, H. (2009). Searching for a new enterprise: Themed tourism and the re-making of one small Canadian community. Tourism Geographies, 11(4), 462–483. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903262638

- Müller, D. K. (2011). Tourism development in Europés “last wilderness”: An assessment of nature-based tourism in Swedish lapland. In A. A. Grenier, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Polar tourism: A tool for regional development (pp. 129–153). Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Müller, D. K. (2013). Hibernating economic decline? Tourism and labor market change in Europe’s northern periphery. In G. Visser, & S. Ferreira (Eds.), Tourism and crisis (pp. 113–128). Routledge.

- Müller, D. K. (2015). Issues in Arctic tourism. In B. Evengård, J. N. Larsen, & Ø Paasche (Eds.), The new Arctic (pp. 147–158). Springer.

- Müller, D. K. (2021). Tourism in national Arctic strategies: A perspective on the tourism geopolitics nexus. In M. Mostafanezhad, M. Córdoba Azcárate, & R. Norum (Eds.), The geopolitics of tourism: Assemblages of power, mobility and the state (pp. 91–111). University of Arizona Press.

- Müller, D. K., Byström, J., Stjernström, O., & Svensson, D. (2019). Making “wilderness” in a northern natural resource periphery. In E. C. H. Keskitalo (Ed.), The politics of Arctic resources: Change and continuity in the ‘Old North’ of northern Europe (pp. 99–111). Routledge.

- Müller, D. K., Carson, D. A., Barre, S., Granås, B., Jóhannesson, G. T., Oyen, G., Rantala, O., Saarinen, J., Salmela, T., Tervo-Kankare, K., & Welling, J. (2020). Artic tourism in time of change (Temanord Report No. 2020-529). Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Müller, D. K., & Viken, A. (2017). Toward a de-essentializing of indigenous tourism? In A. Viken, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism and indigeneity in the Arctic (pp. 281–289). Channel View Publications.

- Paasi, A. (1986). The institutionalization of regions: A theoretical framework for understanding the emergence of regions and the constitution of regional identity. Fennia – International Journal of Geography, 164(1), 105–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11143/9052

- Paasi, A. (2010). 2010). Re-visiting the region and regional identity: Theoretical reflections with empirical illustrations. In R. Barndon, A. Engevik, & I. Øye (Eds.), The archaeology of regional technologies case studies from the palaeolithic to the Age of the vikings (pp. 15–33). The Edwin Mellen Press.

- Pedersen, A.-K. (2016). Is the official use of names in Norway determined by the place-names act or by attitudes? In G. Puzey, & L. Kostanski (Eds.), Names and meaning: People, places, perceptions and power (pp. 213–228). Multilingual Matters; Illustrated edition.

- Pedersen, K., & Viken, A. (1996). From Sami nomadism to global tourism. In M. F. Price (Ed.), People and tourism in fragile environments (pp. 69–88). John Wiley.

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2006). Local and regional development. Routledge.

- Pretes, M. (1995). Postmodern tourism: The Santa Claus industry. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00026-O

- Rantala, O., Barre, S. D. L., Granås, B., Jóhannesson, GÞ, Müller, D. K., Saarinen, J., Tervo Kankare, K., Maher, P. T., & Niskala, M. (2019). Arctic tourism in times of change: Seasonality (Temanord Report No. 2019:528). Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Rantala, O., Hallikainen, V., Ilola, H., & Tuulentie, S. (2018). The softening of adventure tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(4), 343–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1522725

- Regeringskansliet. (2020). Regeringens skrivelse 2020/21:7. Strategi för den arktiska regionen. https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2020/09/regeringensskrivelse-strategi-for-den-arktiska-regionen/.

- Retriever Business. (2020). Affärsinformation. https://www.retrievergroup.com/sv/business-suite.

- Saarinen, J. (2005). Tourism in the northern wildernesses: Wilderness discourses and the development of nature-based tourism in northern Finland. In C. M. Hall, & S. Boyd (Eds.), Nature-based tourism in peripheral areas: Development or disaster (pp. 36–49). Channel View Publications.

- Saarinen, J. (2019). What are wilderness areas for? Tourism and political ecologies of wilderness uses and management in the Anthropocene. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(4), 472–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1456543

- Saarinen, J., & Varnajot, A. (2019). The Arctic in tourism: Complementing and contesting perspectives on tourism in the Arctic. Polar Geography, 42(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1578287

- Salazar, N. B. (2012). Tourism imaginaries: A conceptual approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 863–882. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.10.004

- Shoval, N. (2013). Street-naming, tourism development and cultural conflict: The case of the Old City of Acre/Akko/Akka. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(4), 612–626. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12003

- Syssner, J. (2010). Place branding from a multi-level perspective. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.1

- Tillväxtverket. (2020). Turismens årsbokslut 2019. https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/vara-undersokningar/resultat-franturismundersokningar/2020-09-30-turismens-arsbokslut-2019.html.

- Tuan, Y. F. (1991). Language and the making of place: A narrative-descriptive approach. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 81(4), 684–696. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01715.x

- Väätänen, V., & Zimmerbauer, K. (2020). Territory–network interplay in the co-constitution of the Arctic and ‘to-be’Arctic states. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(3), 372–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1559759

- Varnajot, A. (2020). Rethinking Arctic tourism: Tourists’ practices and perceptions of the Arctic in Rovaniemi. University of Oulu.

- Viken, A. (2013). What is Arctic tourism, and who should define it? In D. K. Müller, L. Lundmark, & R. H. Lemelin (Eds.), New issues in Polar tourism: Communities, environment, politics (pp. 37–50). Springer.

- Viken, A., & Granås, B. (2014). Destinations, dimensions of tourism. In A. Viken, & B. Granås (Eds.), Tourism destination development turns and tactics (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0