ABSTRACT

This chapter magnifies the voices of Alaskan children in considering education for sustainability in the Arctic. The collaborative research explored how children understood and enacted environmental stewardship in three distinct Alaskan locations: Interior Alaska, the Kenai peninsula, and a rural southwest Alaska Native village. Honoring children’s agency, the study involved child-centered research methods, including children’s drawings and descriptions, role-playing, class discussions, and video tours utilizing wearable cameras. Findings revealed common themes of environmental stewardship, yet the way children perceived and enacted stewardship varied according to the social, cultural, and geographical contexts. Cleaning up litter was perceived as immediate and important for children from Kenai and the southwest Alaskan village, yet it was scarcely mentioned by Interior Alaskan children. Interior Alaskan children emphasized pet care, while children from Kenai and the southwest Alaskan village discussed animal care in relation to hunting and fishing ethics. Care for plants was less common than care for snow. Children’s spatial autonomy, sense of belonging and personal connection with place, plays an important role in the development of competencies to live more sustainably on the land. Findings point towards contextualized and child-centered approaches to promote children’s agency to act in and for their environments.

Introduction

Our children are living in an unpreceded time of great change. With increasing sea levels and pH in the ocean, melting permafrost and glaciers receding, coastal margins shifting and sea ice shrinking, children of the Arctic and subarctic regions are experiencing the effects of global warming at a rate of almost twice the global average (Thoman & Walsh, Citation2019). In Alaska, where Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples depend on the land and sea for survival, such changes are having a profound impact on land and sea life as we know it (Thoman & Walsh, Citation2019). The climate crisis is a children’s rights crisis (Makuch et al., Citation2019). It is important now more than ever that we pay attention to their voices and ideas for living more sustainably on this planet:

The consequences of the climate crisis are all around us, affecting children the most and threatening their health, education, protection and very survival. Children are essential actors in responding to the climate crisis. We owe it to them to put all our efforts behind solutions we know can make a difference (UNICEF, Citation2019).

Education for sustainable development in the Arctic

Sustainable development has been defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs’ (World Commission on Environment and Development, Citation1987). Broad goals of sustainable development center around balancing three pillars, including the economy, society, and environment. A healthy environment is foundational for a healthy society, and in turn, a healthy economy (Purvis et al., Citation2019). Education has and continues to play a critical role in the promotion of sustainable development. Namely, Agenda 21, Chapter 36 of the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro promoted ‘education, public awareness, and training’ (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development & Sitarz, Citation1993). UNESCO designated 2004–2014 as a decade for education for sustainable development (ESD). More recently, The United Nations identified 17 interrelated sustainable development goals, with the fourth goal pertaining to quality education (United Nations, Citation2020). Among these, emphasis is placed on good health and well-being, responsible consumption and production, reduction of poverty and inequalities, economic growth and industry, and climate action and partnerships. While each goal specifies a particular emphasis, sustainable development is recognized as complex and locally dependent. Thus, ESD should address the needs of peoples that inhabit particular regions or places, while also considering global implications.

International goals for sustainable development have long been criticized for not being ‘designed with the Polar Regions in mind’ (Nilsson & Larsen, Citation2020, p. 2). Particularly in the Arctic, sustainability must be considered in light of the extremities of its climate and amidst rapid social, economic, and environmental change. Furthermore, the Circumpolar North is made up of modern contemporary cities as well as many small remote Indigenous villages located off the road system. Access to material goods and infrastructure varies greatly between urban and rural contexts. Petrov et al. (Citation2016) argues that there is a need for Arctic sustainability research that considers ‘the interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities’ and ‘urban-rural relationships’ (p. 173). Additionally, Arctic scholars argue for a deeper understanding of the gendered and generational differences in understanding of sustainability (Petrov et al., Citation2016). Inclusive and participatory approaches are necessary for engaging all stakeholders (Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Nilsson & Larsen, Citation2020). In this article we argue for the need to include children and youth’s perspectives in ESD Arctic research and practice.

Sustainability and children’s perspectives

The negative effects of climate change are unequally experienced by ‘the poor, the children, and the nonhuman’ (Malone, Citation2020, p. 4). There is a need for an increased unified international framework for the protection of the environmental rights of children (Makuch et al., Citation2019). Such environmental rights not only include protections from environmental degradation, they also include provisions for access to natural settings, which are explicitly linked to children’s physical health and mental and spiritual well-being (Makuch et al., Citation2019). ESD offers a framework that links human rights with environmental protections (UNESCO, Citation2014). A growing body of ESD scholars have argued that children should take an active role in problem-solving and addressing sustainability issues (Elliott et al., Citation2020).

In the Arctic, young people are becoming increasingly engaged in environmental advocacy and the fight against climate change. For example, Swedish youth Greta Thunberg boldly argues that humanity is facing an existential crisis because of global warming (Thunberg, Citation2019). Young activists in Alaska are also taking a stand. Recently, sixteen youth sued the State of Alaska for its role in contributing to climate change, arguing the State’s negligence in inaction is a violation of public trust and endangerment to their future (Joling, Citation2019). Two Alaska Native youth, Nanieezh Peter and Quannah Chasing Horse Potts, advocated for the Alaska Federation of Natives to take a more prominent stand on climate policies; they presented a resolution – collaboratively drafted with guidance from Elders – that was passed declaring a state of emergency on climate change and reinstating a climate action leadership task force (DeMarban, Citation2019).

Around the globe, childhood researchers advocate for children to take a more active role in research (Green, Citation2015). Approaches that honor research with children are important not only because of the role children will have in shaping our future, but also in recognizing the agency of children in the present (Elliott et al., Citation2020). Childhood is a vulnerable period, whereas, children typically have little power to create change in their homes and in their communities. Historically speaking, approaches in research and education have disenfranchized the agency of children (Corsaro, Citation2018). However, with the rise of the children’s rights movement (UNICEF, Citation2019), approaches in research and education are shifting to ensure that children are positioned to share what’s important to them and to honor their voices and perspectives.

Children and youth in the Arctic face the impacts of climate change more rapidly and more extremely than children in other parts of the world, as the effects of anthropogenic climate change become more pronounced and disruptive in polar regions. Through a participatory project, this research extends understanding of youth advocacy in Alaska by exploring young children’s perceptions and enactment of environmental stewardship in both Alaskan urban and rural Indigenous communities.

Research methods

Context

The research presented in this article emerged as a final collaborative project in a graduate education course titled, Children as Cultural Change Agents, at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Six graduate students and their professor became co-researchers in a participatory study aimed at exploring how children from three unique Alaskan communities understood and enacted environmental stewardship. Theories of children’s agency formed the foundation of this course, and subsequently this project. Specifically, we recognized children as individuals capable of change in their own right, who ‘can make a difference to a relationship, a decision, to the workings of a set of social assumptions or constraints’ (James, Citation2009, p. 34).

The varying Alaskan settings makes this study unique. All of the studies took place inside the classroom and outside in the snow-covered spaces around the schools. Our selection of the three Alaskan schools relied heavily on our existing roles and relationships. Two researchers served as teachers at two sites. These two teachers partnered with two non-teachers from the graduate education course, each forming an insider-outsider researcher dyad. The first involved a Kindergarten teacher and her class of fifteen 5–6-year-old children from Kenai Peninsula. Kenai children drew pictures in the classroom and visited a wooded forest near their school. The second involved a teacher and her five Senior (12th year) students enrolled in a capstone class at a southwest Alaskan Yup’ik village school. The Seniors took on the role of co-researchers in facilitating the project with eight kindergartners (5–6-year-old children). The children were invited to draw pictures and role-play in their Kindergarten classroom; they also ventured outside their school on a cold, dark, and windy day.

The third site was facilitated by the remaining two graduate student researchers and involved eleven 4–5-year-old children from a university early childhood education lab school in Interior Alaska. The Interior Alaskan children enacted environmental stewardship inside their school (house) and in their fenced-in outdoor schoolyard.

The Kenai and Interior Alaskan sites are ‘on the road system’ and predominately made up of students from non-Native backgrounds. While the southwest Alaskan site is located ‘off the road system,’ only accessible by plane, and consisted primarily of Yup’ik children. Therefore, when interpreting the transferability of these findings to other communities in the Arctic, the reader should consider the distinguishing characteristics of the study sites (Miles et al., Citation2020).

Methodological approach

Our collective goal was to include children as active participants through honoring their agency in each context. As such, we implemented the mosaic approach, as a multi-method, participatory, and adaptable framework for listening to and understanding children’s shared experiences (Clark, Citation2017). ‘The Mosiac approach gives young children the opportunity to demonstrate their perspectives in a variety of ways’ (Clark, Citation2017, p. 34). It includes two main stages. First, children are invited to engage in multiple methods to document and share their understandings. Second, data from the various methods are brought together and organized into themes. Children and adults are invited to engage in dialogue, reflect on and interpret meaning from the findings (Clark, Citation2017; Rogers & Boyd, Citation2020). In our study, we enacted the mosaic method by asking children, at each site, to articulate and represent how environmental stewardship is enacted in their own lives through multiple modes of expression. In this way, the various data sources were triangulated to increase the trustworthiness and credibility of the findings.

The study was approved by the institutional review board in which the researchers were affiliated. Permission was granted from school administrators and teachers. Informed consent was provided by parents of child participants at all sites. Verbal child assent was also sought on an ongoing basis; whereas children were invited to choose whether they wanted to participate in each research activity. We recognized that our role as teacher-researchers would inevitably influence (to varying degrees) how children expressed their agency around the topic of environmental stewardship. Thus, our approach was both reflexive and flexible, adapting to the changing needs and dynamics in the children in each research setting.

Data collection methods

All sites employed the following participatory methods: child-led tours, children’s drawings and descriptions, and role-playing/discussions. At the southwest village site, the Seniors developed a list of discussion questions to guide the activities. The kindergartners rotated between three stations led by the Seniors during a 45-minute period. At the Kenai site, children engaged in sensory tours, created drawings and described them, and engaged in class discussions about their experiences. At the Interior Alaskan site, researchers worked with the children over three days, facilitating art activities, child-led photography and tours, and partnering with the teacher to facilitate discussions.

Importantly, at each site, children were oriented to and guided through each activity with a focus question related to environmental stewardship. At the Interior Alaska site, children were asked who and what they take care of, and conversely, who and what takes care of them. As well they were also asked how they take care of their indoor and outdoor environments at the school and/or at home. At the southwest village site, the Senior student-researchers developed a set of questions to stimulate conversation with the younger students prior to and during activities. At the Kenai site, children were prompted with the question ‘how do we take care of our environment’ prior to and during art-making activities, discussions, and sensory tours. Below, data collection methods are described in more detail.

Child-led tours

All sites engaged children in some form of a ‘tour’ in both their indoor and outdoor spaces. ‘Tours allow opportunities for children to show something that cannot be explained’ apart from the setting (Green, Citation2012, p. 275). Given the tendency for children to ‘talk while they are doing’ (Parkinson, Citation2001, p. 145), tours provided an opportunity for children to both direct their movements and share what was important to them in their setting. As part of the mosaic framework for listening to children, children were also invited to engage in interactive discussions both before and after their tours to share about their experiences (Clark, Citation2017).

Following the sensory tour method employed by Green (Citation2016), children at the Kenai site were invited to wear small wearable cameras as they ventured into a wooded area behind their school. Two groups of 5–7 students went out with the three researchers and a teacher assistant to the nature trail for approximately 15 min. They followed the nature trail together, before venturing and exploring on their own. Children took turns wearing the cameras to document their experiences. Researchers also used iPads to video and take pictures of children’s activities.

At the Interior Alaskan site, iPads were also used to video child-led tours. Prompted with the question of how they take care of things at school, children were divided into three groups and invited to show their indoor and outdoor classroom spaces. This activity occurred on the first day, as planned, and emerged again as an interest of children on the third day. Planned child-led photography was modified into child-led video tours in response to children’s interest.

In the southwest village, the Senior student-researchers designed an ‘exploration station’ with the goal to take Kindergarteners outside to see and explore their environment with minimal restrictions. During the exploration, the Seniors utilized activity prompts to stimulate discussions with the younger children. Kindergarteners were provided small digital cameras to take pictures or videos; a Senior also recorded the explorations with a digital camera.

Children’s drawings and descriptions

Children engaged in drawing at all three sites. After their drawings were complete, children were invited to describe them. This method allows for a better understanding of the complexity of children’s ‘voices’ in letting them express themselves in more than one way (Eldén, Citation2013). In this method, focus is ‘placed on the process of meaning making rather than children’s artistic abilities or finished products’ (Green, Citation2017, p. 11).

At the Kenai site, researchers prompted children to draw pictures of how to take care of the environment. An older class of 10–11-year-old ‘study buddies’ helped the younger children label and write descriptions of their pictures. Researchers also took videos of the children’s descriptions.

At the Interior Alaskan site, preschoolers were invited to draw two pictures: one showing how they took care of something inside, and the other showing how they took care of something outside. Children were then placed in groups of three to five, and an adult invited each child to discuss their drawing. Children’s descriptions were either audio-recorded or written on sticky notes that were placed on their drawings. Additionally, children were given the opportunity to create artwork on other days of the research and provided opportunities to share during whole class discussions.

At the village site, one Senior student led the drawing station, and asked the children to draw what they do when they see trash on the ground and what they like to do outside. While the children drew, the Senior students asked the children other questions related to environmental stewardship. The young children were then invited to discuss and explain their drawings to ensure that they were properly understood. A laptop was used to video record the discussions.

Role-playing, puppets, and group discussions

At all three sites, children engaged in role-play and discussions to gain further insight. We adopted puppets and role-play in our research to harness children’s creativity and imagination and to keep activities engaging and fun (Clark, Citation2017; Green, Citation2012) and because ‘role-play requires children to consider ideas from various perspectives and draw upon their own beliefs, values, and experiences’ (Green, Citation2017, p. 13).

The researchers worked closely with the teacher and a spruce-tree puppet named ‘Mr. Tree’ at the Interior Alaskan preschool to engage children in discussions. Activities from previous days, accompanied with pictures, were shared with the children to stimulate their memory, as well as a tool to listen to their feelings about different topics that had emerged during other activities. Some of the children's responses to specific questions were written on a large sheet of paper, providing a visual for children to map their understanding (Clark, Citation2017).

At the southwest village site, two Seniors led the younger children in acting out simple local activities, including: picking up trash, fishing, ‘going by boat,’ etc. Children were invited to act things out and describe what they were doing.

Children at the Kenai site participated in group discussions before and after their outdoor explorations. The researchers posed the question: ‘How do we take care of the environment?’ Children shared their ideas while the teacher-researcher recorded them on large chart paper.

Discussions at all three sites were video recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Data analysis and children’s involvement

At the three sites, researchers and youth participated in analysis of data for emergent themes. Children from Interior Alaska and Kenai participated in post-tour discussions about their experiences. At the southwest village site, Senior student assistant researchers engaged in initial analysis by reviewing video and counting the frequency of themes that emerged among the kindergartners’ responses. Seniors reflected on the data collection process and engaged in discussion with each other and their teacher-researcher. The Senior’s interpretations of the Kindergartener’s engagement in environmental stewardship are included in the findings. At the Interior Alaska site, the researchers watched the videos and coded data for themes after their first visit. They then brought printed screen shots of emergent themes from the video tours in order to elicit analysis discussions with the preschoolers about their experiences. At the Kenai site, Kindergarteners reflected together with the teacher-researchers on what they noticed and what they did to further discuss what it means to take care of their community.

In the first cycle analysis, the researchers assigned codes to describe the stewardship behaviors that emerged from the various forms of data at each site. Descriptive codes were used to assign labels to data in a word or short phrase. In vivo codes were also used where appropriate to highlight children’s voices and perspectives (Miles et al., Citation2020) Miles et al. (Citation2020) note that descriptive codes are appropriate for ‘studies with a wide variety of data forms’ (p. 65). While initial analysis rendered a larger number of descriptive codes to the data at each site, in a second cycle of analysis the researchers worked together to combine the codes from each site to form broader themes. Themes were constructed to cluster codes according to commonalities and depict similarities and differences in stewardship behavior in all three sites (Miles et al., Citation2020). For instance, ‘cleaning up litter’ and ‘recycling’ were initially coded at the Kenai site, however, because recycling was scarcely mentioned at the Interior Alaska and Southwest Alaska sites these codes were combined under the broader theme of ‘picking up litter.’ The various forms of data (i.e. children’s drawings, quotes, and descriptions) are presented in the findings under four main themes of children’s environmental stewardship behaviors.

Credibility/Transferability/Triangulation

Cresswell and Guetterman (Citation2019) explain that the trustworthiness of qualitative data can be established in four ways. First, developing codes and themes from multiple sources of data establishes the credibility of the findings. Second, our goal was to provide sufficient detail of the study context and methodological procedures in order to establish transferability from one setting to another. Thirdly, findings from the different types of data and different individuals at each site were triangulated to strengthen the trustworthiness of qualitative findings. Fourthly, in-depth descriptions of qualitative findings are presented to render insight on participant’s perspectives and increase credibility of the findings.

Findings

Common themes of children’s environmental stewardship included: picking up trash, care for animals, care for plants, and snow. Children’s perceptions and enactment of these four themes varied in relation to children’s daily interactions and the needs and cultural practices within their community. Quotes from the children are italicized in order to highlight their voices. Photographs of children’s drawings are also shared to elicit children’s understandings. Additionally, qualitative descriptions of children’s tours and role-play activities reveal the context of their enactment of environmental stewardship in familiar settings.

Picking up trash

‘Picking up trash’ was an important stewardship activity at all three Alaskan locations.

Interior

In Interior Alaska, cleaning up trash arose in the initial group discussion:

We’re studying what children, like you, do to take care of the world around you–what you do to take care of your environment.

Um, clean up trash.

Oh, that’s a really good idea.

We clean up trash every single day.

Clean up trash like WALL-E

Kenai

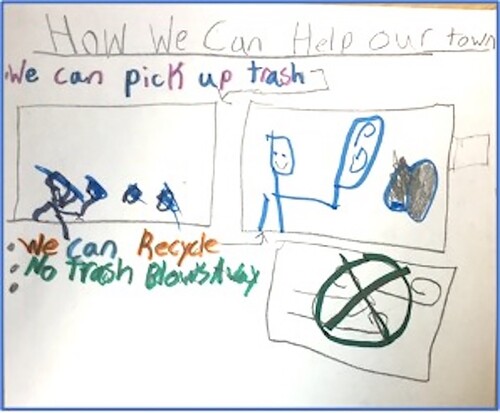

At the Kenai site, 12 of the 15 Kindergarteners mentioned picking up trash during a draw and write activity with fifth-grade study buddies. For these kindergartners, picking up trash was fresh in their minds because, together with their study buddies, they had recently picked up litter along the nature trail behind their school. reveals children’s written descriptions of picking up trash.

Table 1. Kenai children’s descriptions of ‘how we take care of our community’.

Along with picking up litter, these children also talked about recycling and reducing plastic waste in the ocean. Children’s drawings and written statements provided directives, indicating the perception of picking up trash as a social action. They associated the importance of this activity in conserving nature and helping the community ().

Southwest village

Picking up trash was also one of the first topics that emerged among Seniors as they discussed how they would direct the project with the Kindergarteners from the southwest Alaskan village. Though efforts are being made to improve the garbage system, litter is common in the village. Trash is often dumped into insecure bins that dogs get into and tear apart; trash also is blown across the landscape from improperly disposed bags at the dump.

Seniors developed six prompts to invite Kindergarteners to share their perspective about trash:

What do you do if you see trash on the ground?

Do your parents scold you when you throw trash on the ground?

When you go camping where do you put your trash?

How do you feel when you see trash on the ground?

How can trash hurt our animals, like birds, seals, whales, or fish?

When you're playing out and have a snack, where do you put your trash?

In the role-playing station, the Seniors modeled and Kindergarteners pretended to pick up trash and throw it away. They role-played camping, boating, and playing outside. When asked about seeing trash on the ground or where to put trash, all the kindergartners were quick to respond with, ‘pick it up’ or ‘put it in the garbage.’

The Seniors reviewed the videos of the data collection activities and made the following observations:

They said they knew where the trash had to go.

They drew trash and what they do about it. They drew what they do outside.

The conversation was about picking up trash.

Picking up trash was the most.

Garbage kept coming up in all of the stations.

You throw it away in the trash.

The thing that stood out to me was how their parents don’t talk to them about the trash outside, they just did what was right for nature.

Care for animals

Care for animals emerged as an important theme in every location. Children primarily focused on caring for pets, but reference to wild (non-domesticated) animals also arose in all of the locations ().

Table 2. Children’s expressions on care and stewardship for animals across sites.

Interior

Preschool children from the Interior Alaskan site, discussed specific ways in which they cared for their pets (dogs, cats, and reptiles), including providing food and water, and ‘petting’ them. Two children also mentioned caring for chickens and eggs at their home ():

Tricia shared ‘I take care of chickens. Me and my chicken and my tortoise. I get the chicken on the tortoise. I feed and water them.’

During a classroom tour, the preschool children inadvertently bumped the rabbit cage and spilled food. They demonstrated stewardship, through their own initiative, taking turns with a handheld vacuum to clean it up.

Outdoors, two of the preschool children demonstrated an awareness that they shared their schoolyard with a squirrel. During a tour of the schoolyard, the girls pointed out ‘Chippy’s tree’ and a small piece of cloth on the ground.

And he takes our napkins.

He takes everything.

Stewardship, in this interaction, applied to both caring for the wellbeing of the squirrel and their schoolyard.

Kenai

Similarly, Kindergarten children from Kenai shared about taking care of pets (cats and dogs) and not hurting them. Related to cleaning up litter, Billy said, ‘We pick up trash and then if we see a moose we go to the sign.’ When asked, ‘Does that help take care of the moose?’ most of the class responded, ‘Yes.’ Mary added, ‘By not eating us.’

Additionally, during the draw and write activity one child shared about being nice to the butterflies ‘by not touching them.’ ()

These children were becoming aware of their surroundings and providing wild animals with space.

Southwest village

Animal care was also a topic of interest among both the Seniors and the Kindergarten children in the southwest Alaskan village. The Seniors wrote three question prompts related to animals:

How do we take care of animals?

How can trash hurt our animals, like birds, seals, whales, or fish?

When you go fishing, what do you do if you catch a really little fish?

What do you do if you see an animal that's sick?

Discussions among Seniors included ideas involving animal stewardship and the importance of cultural and sustainable subsistence hunting practices. The Seniors talked about different laws, unofficial rules, and community expectations with regards to hunting or collecting wild bird eggs, such as not taking all the eggs from a nest. They emphasized the importance of humane hunting practices that limit suffering, such as shooting to kill an animal rather than wounding it.

In the role play station, the actions and conversations mostly focused on two sub-themes: taking care of pets, and what to do with sick or injured animals. This topic was emphasized in the role-play station. Seniors and kindergartners pretended to pet their dogs, feed them, and play with them. They emphasized not hitting their animals ().

Table 3. Children’s expressions of environmental stewardship at role play station.

Kindergarteners also acted out ‘looking for mouse food’ – a traditional subsistence practice that involves looking for where a mouse has stored its cache and digging up the roots and twigs to take home and eat. When the Seniors asked kindergartners what they would do if they saw a sick animal in the wild, several answered, ‘Shoot it!’ and mimed shooting a gun. Elia, a Senior, asked the Kindergartners about taking a sick animal to an ‘animal rescuer,’ although the village does not have an animal rescuer. Layla, another Senior, pointed out that the Department of Fish and Game operates in the area, and that while they do not necessarily rescue animals, they keep track of sick animals. Kindergarteners also mentioned the importance of killing fish once they are pulled out of the water. Bob acted out fishing and catching one. He said, ‘cut it,’ and Earl added, ‘Hit it.’ Later, when Mike and Petunia ‘went fishing,’ after pulling in their fish, Elia asked them what they do when they catch a fish and it’s flopping around on the ice, and they both answered, ‘Kill it!’ Petunia also talked about her mom cutting up the fish and showed with her hands how her mom cut it.

Care for plants

A few children mentioned care for plants. This act of stewardship was less common, perhaps because data were collected during the winter when snow covered the ground.

Interior

Among preschool children at the Interior Alaskan site, Gina drew a picture of her garden. She described, ‘Mom's garden. We water and put some seeds. We put soil in and we water it every day. I tell mom that we have to water every day. Mom picked some flowers for Luna (a bee) because she was about to die.’

Interestingly, a garden did not come up at any other site.

Kenai

At the Kenai site, two Kindergarten children expressed care for forest flora. Charlie described being nice to the grass, explaining, ‘I don’t pull it up.’ A video from Steven’s tour revealed his effort to preserve a small tree:

‘That’s a baby tree! Don’t step on it!’ Steven yelled to his peers.

He moved carefully around the tree.

‘This is a papa tree, this is a dead tree.’ Steven explained.

This example shows how empathy informs children’s stewardship. By spending time in the forest, James took notice of the trees and how to care for them.

Care for plants was inferred at the southwest Alaska site. Seniors asked children two questions that indirectly referred to care for plants:

When you go camping where do you put your trash?

When you go berry picking/fishing/egg hunting/ how do you take care of the environment?

Clearing snow

Clearing snow was a stewardship activity that came up at both the Interior Alaskan and Kenai sites. This activity was primarily associated with making the environment ready for humans.

Interior

During a video tour, children, dressed in their snowsuits, shuffled their bodies outdoors and immediately ran to collect kid-sized snow shovels and brooms. Back and forth, back and forth they pushed the shovels and brooms across the snow-covered walkways next to the building.

‘Get off the snow. Get all the snow not in the aisle,’ Tricia said.

Kenai

Similarly, at the Kenai site, two Kindergarten children took the initiative to sweep snow off logs in an area in the forest, which had formerly been used by their class as an outdoor learning space. During a whole group discussion after their forest exploration, Bennie shared that he swept the snow off the logs so that his peers ‘won’t get wet if they don’t have snow pants on.’ With this act, he was taking care of both the outdoor environment, and his classmates.

Southwest Alaska

The theme of ‘clearing snow’ did not arise among children from the southwest Alaskan village. Rather children expressed excitement in the opportunity to be in the snow. The day of the research coincided with the first real snow of the season, so most of the children were excited. In the role-play station, when asked what they liked to do outside, kindergartners acted out snow-related activities, including: ‘making snowballs, building a snowman, and sliding (sledding).’ Likewise, children were eager to be out in the snow during the ‘exploration station’ (i.e. when the Seniors and Kindergartners went outside to walk around). While outside, Petunia, a Kindergartner, said her hands were cold; Rebecca, one of the Seniors, asked if she wanted to go inside, and she quickly said ‘no,’ indicating that she just wanted to put her gloves back on. Later, she ran, slipped and fell; she immediately picked herself up and said she was okay. Overall, these interactions reveal children’s resiliency to ‘play out’ in their environment.

Discussion

Our findings reveal similarities and differences in children’s perceptions of environmental stewardship across all three sites. This aligns with the understanding that approaches to sustainable development in the Arctic will vary according to the social and cultural contexts and the infrastructure that exists in a community (Nilsson & Larsen, Citation2020; Petrov et al., Citation2016).

For children at all three sites, picking up trash/litter was deemed as important and is in line with the global sustainability goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation (UNESCO, Citation2014). The relevance of this action varied across sites. Among Interior Alaskan preschoolers, ‘cleaning up trash’ emerged in the initial group discussion, but was scarcely talked about again. In discussion, it was referred to more symbolically than concretely, as evident in one child’s comment, ‘clean up trash like WALL-E.’ The issue of litter, for these children, appeared to be more distant and it was not perceived as a problem in their everyday settings (i.e. home, school). Among children in Kenai, however, picking up trash was a tangible act in which many of them had recently participated in along the nature trail near their school. These children, as well as their third-grade study buddies, recognized litter as a problem both on land and in the ocean. One child even drew himself in a dump truck, imagining himself taking on the role of collecting garbage and recyclables. In the southwest Alaska village, the Seniors explained, litter was a problem in the village because of improper disposal. For these youth, cleaning up litter was necessary and important. The Seniors developed question prompts to guide the Kindergarten children into thinking about what they can do to take care of trash while playing out, camping, and during other common activities. By discussing trash in various contexts, children were prompted to think about proper waste disposal and its relevance to their daily lives. While the Senior’s prompts undoubtedly influenced how the younger children perceived stewardship, their position as role models cannot be understated. Youth teaching and engaging younger children in addressing an important community issue sparks the potential to provoke intergenerational environmental action (Lawson et al., Citation2018). Indeed, the Seniors enjoyed the opportunity to engage as active researchers in the project with the younger children, and expressed a desire to extend their outreach to other grade levels.

Care for animals was also expressed across all three sites, relating to global sustainability goals 14 and 15: Life on Land and Life on Water (UNESCO, Citation2014). All of the children discussed the importance of caring for and not hurting domesticated animals, such as cats or dogs. Children from Interior Alaska also talked about caring for chickens and a tortoise. These children discussed putting away and cleaning up their belongings so that animals do not ‘get our stuff.’ Stewardship was perceived as protecting and preserving one’s belongings; this could also be related to sustainable development goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production (UNESCO, Citation2014). Children in Kenai extended ideas to include taking precautions when encountering potentially dangerous mammals (i.e. bears and moose). One child discussed hunting moose with his father for food. Additionally, another drew a picture of keeping the ocean clean of litter to protect fish. Care for sea animals (seals, whales, and fish) was similarly discussed among Seniors and Kindergarteners from the southwest Alaskan village, who live on the coastline 500 miles west of the Kenai children. Children from the village discussed care for sick animals. Specifically, they emphasized the importance of shooting a suffering animal and ensuring proper processing of fish. Others discussed ‘looking for mouse food,’ a traditional Yup’ik subsistence practice. This study reveals that even at a very young age, subsistence is seen as an integral part of environmental stewardship. While cultural subsistence is not specified within the global sustainability goals, it is recognized essential to sustainability in the Arctic, and, therefore, should be emphasized in educational efforts.

Interestingly, stewardship practices associated with care for plants were less common in this study. Cultivating plants by way of a garden only emerged at the Interior Alaska site. On the other hand, clearing snow and enjoying it through playful activity was perceived as an act of stewardship among these Arctic children. While this finding is not surprising, this just echoes the fact that education for sustainable development must be positioned within a place-based context. Children’s relations with snow also develops their resiliency. While Interior Alaska children indicated they were cold and asked to go inside, children from the village eagerly went outside even amidst unfavorable weather conditions. Future sustainability research and educational efforts with children in the Arctic might explore the degree to which cultural, geographical, and climate conditions inform children’s resiliency.

Global Sustainable Development goals related to economic growth, energy, hunger, and poverty were not specifically mentioned by the children in this study. Yet many if not all of these goals are related to the children’s perceptions and enactments of environmental stewardship. As scholars point out, human livelihoods in the Arctic are dependent on a mixed subsistence-token economy (Nilsson & Larsen, Citation2020). Findings reveal that children both from Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities related environmental stewardship to maintaining cultural subsistence practices.

This study also revealed that for children of the Arctic the development of spatial autonomy is a precursor for knowing your place and living sustainably on the land. Children’s spatial autonomy, their sense of belonging and personal connection with place, informs the way in which they learn to steward and take care of their places (Green, Citation2017; Lunda & Green, Citation2020). While outside, the Interior Alaskan children took ownership by shoveling snow from the walkway, and taking care to ensure that their schoolyard squirrel did not eat a napkin accidently left on the ground. While the Kenai children had previous experiences on the nature trail outside their school, during the research project the children were given their first opportunity to freely explore off trail on a wet snowy day. This allowed for children to take notice and care for a ‘baby tree.’ Children from the village emphasized the importance of playing out. This included activities that ranged from playing in snow and taking care of pets to boating, fishing, and hunting. For these children, it appears that being outdoors refines their sense of self in stewarding their environment.

Conclusion

Taken together, children from all three Alaskan sites shared common ideas regarding environmental stewardship, including concerns about litter, taking care of pets, ethics of subsistence practices, and relating with snow. While findings show that these sustainability topics are in particular reach for young children, it is important to note that the expressions of these stewardship practices varied in association with cultural practices, geographical locations, and ways of relating with place, people, animals, and the land. Thus, while these topics might provide a starting point for developing Education for Sustainable Development curriculum, it is important that the methods for teaching such topics be designed in a way that honor children’s voices and perspectives.

The process of facilitating a project such as this required openness and flexibility. None of us knew what to expect when we posed the question, what does environmental stewardship mean to Alaskan children and how is it enacted? None of us knew exactly how children would respond and in what ways our participatory project would unfold. At each site the methods evolved in unexpected ways and from the beginning we knew it was important to take a step back from the urge to control the situation – to step back from approaches to education that dictate what children should do when and how (Jickling et al., Citation2018). To be successful in our child-led inquiry, we felt it was important that we as researchers should be quiet observers from the sidelines, allowing children the opportunity to pick up the snow shovel, clean up litter, preserve a tree, and clean up rabbit food. Through emerging methods, child-centered approaches promote children’s agency to act both in and for their environments. Arctic education for sustainable development must be inclusive and empowering, and as findings from our study show, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach; rather, it will take teachers open to listening, open to learning, open to developing frameworks that honor culture, place, and our children’s perspectives. By opening ourselves up to the unpredictable, we are enabling our children to grow as agents of cultural change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Clark, A. (2017). Listening to young children, expanded third edition: A guide to understanding and using the mosaic approach. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Corsaro, W. A. (2018). The sociology of childhood (5th ed.). Sage publications.

- Cresswell, J., & Guetterman, T. C. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson.

- DeMarban, A. (2019). AFN declares ‘state of emergency’ for climate change. Anchorage Daily News. https://www.adn.com/alaska-news/2019/10/20/afn-declares-state-of-emergency-for-climate-change/

- Eldén, S. (2013). Inviting the messy: Drawing methods and children’s voices. Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark), 20(1), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568212447243

- Elliott, S., Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E., & Davis, J. (Eds.). (2020). Researching early childhood education for sustainability: Challenging assumptions and orthodoxies. Routledge.

- Green, C. (2012). Listening to children: Exploring intuitive strategies and interactive methods in a study of children’s special places. International Journal of Early Childhood, 44(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-012-0075-9

- Green, C. (2016). Sensory tours as a method for engaging children as active researchers: Exploring the use of wearable cameras in early childhood research. International Journal of Early Childhood, 48(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-016-0173-1

- Green, C. (2017). Children environmental identity development in an Alaska Native rural context. International Journal of Early Childhood, 49(3), 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-017-0204-6

- Green, C. J. (2015). Toward young children as active researchers: A critical review of the methodologies and methods in early childhood environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 46(4), 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2015.1050345

- James, A. (2009). Agency. In J. Qvortrup, W. A. Corsaro, & M. S. Honig (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies (pp. 34–45). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jickling, B., Blenkinsop, S., Morse, M., & Jensen, A. (2018). Wild pedagogies: Six initial touchstones for early childhood environmental educators. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 34(2), 159–171.

- Joling, D. (2019, October 9). Alaska supreme court hears youths’ climate change lawsuit. Anchorage Daily News. https://www.adn.com/alaska-news/2019/10/09/alaska-supreme-court-to-hear-youths-climate-change-lawsuit/

- Lawson, D. F., Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., Carrier, S. J., Strnad, R., & Seekamp, E. (2018). Intergenerational learning: Are children key in spurring climate action? Global Environmental Change, 53, 204–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.002

- Lunda, A., & Green, C. (2020). Harvesting good medicine: Internalizing and crystalizing core cultural values in young children. Ecopsychology, 12(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2019.0066

- Makuch, K. E., Zaman, S., & Aczel, M. R. (2019). Tomorrow's stewards: The case for a unified international framework on the environmental rights of children. Health and Human Rights, 21(1), 203–214.

- Malone, K. (2020). Children in the anthropocene: How are they implicated? In A. Cutter- Mackenzie-Knowles, K. Malone, & E. Barratt Hacking (Eds.), Research handbook on childhoodnature: Assemblages of childhood and nature research (pp. 507–533). Springer International Publishing.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage.

- Nilsson, A. E., Carson, M., Cost, D. S., Forbes, B. C., Haavisto, R., Karlsdottir, A., Larsen, J. N., Paasche, Ø., Sarkki, S., Larsen, S. V., & Pelyasov, A. (2019). Towards improved participatory scenario methodologies in the Arctic. Polar Geography, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937x.2019.1648583

- Nilsson, A. E., & Larsen, J. N. (2020). Making regional sense of global sustainable development indicators for the Arctic. Sustainability, 12(3), 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031027

- Parkinson, D. D. (2001). Securing trustworthy data from an interview situation with young children: Six integrated interview strategies. Child Study Journal, 31(3), 137–157. .

- Petrov, A. N., BurnSilver, S., Chapin, F. S., III, Fondahl, G., Graybill, J., Keil, K., Nilsson, A. E., Riedlsperger, R., & Schweitzer, P. (2016). Arctic sustainability research: Toward a new agenda. Polar Geography, 39(3), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2016.1217095

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

- Rogers, M., & Boyd, W. (2020). Meddling with mosaic: Reflections and adaptations. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(5), 642–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1817236

- Thoman, R., & Walsh, J. E. (2019). Alaska's changing environment: Documenting Alaska's physical and biological changes through observations. International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- Thunberg, G. (2019). No one is too small to make a difference. Penguin.

- UNESCO. (2014). Shaping the future we want: UN decade of education for sustainable development (2005–2014) final report. UNESCO.

- UNICEF. (2019). The climate crisis is a children’s rights crises. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/fact-sheet-climate-crisis-child-rights-crisis

- United Nations. (2020). Envision 2030: 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/envision2030.html

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, & Sitarz, D. (1993). AGENDA 21: The Earth Summit strategy to save our planet. EarthPress.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press.