Introduction and background

The representation of diverse scholars from various ethnic, cultural, and ability groups in the Earth sciences is critically low exhibiting a crucial need and an opportunity to not only increase diversity but also to create agency for diverse scholars (Bowser & Cid, Citation2021). These needs can be effectively accomplished through the development of innovative strategies that focus on damaging policies, practices, and opinions prevalent within academia as it struggles and create equitable spaces for all to feel supported and welcome (Guillory & Wolverton, Citation2008; Smythe et al., Citation2020). VOICES of Integrating Culture in the Earth Sciences (VOICES) is a collaborative program dedicated to identifying persistent issues preventing the retention, representation, and recruitment of all racial, ethnic, and cultural groups currently underrepresented in the Earth sciences. Here we define with intention diverse scholars as those historically underrepresented, as a construct of ableism, gender, sexuality, cultural, and racial identities using asset-based language to capture the intersection of these complex identities (Gomez et al., Citation2021; Steele, Citation1997; Steele & Aronson, Citation1995). Studies have show that brief interventions have positive influences on sense of belonging (e.g., being part of something or feeling welcome, Freeman et al., Citation2007) and efficacy of identify as a scientist (Syed et al., Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2018; Walton & Cohen, Citation2011; White et al., Citation2019), of which a majority of these interventions have not been disseminated beyond the small group they originally focused on. As such, the lack of cultural diversity in a dominant white, male, and able-bodied discipline persists and the lack of diversity continues to be alarming (Bowser & Cid, Citation2021; Sheffield et al., Citation2021). Various efforts to recruit and retain diverse scholars across a spectrum of racial, cultural, and gender identities have failed to effect meaningful change in the Earth sciences as barriers to inclusion remain (Bell & White, Citation2020; Estrada et al., Citation2016; White & Bell, Citation2019; Yoder, Citation2016). The intention of the VOICES program is to foster safe spaces that empower diverse scholars to reclaim their voice, to acknowledge the necessity of power sharing by those in positions of power and privilege, and to provide foundational knowledge of belonging, access, justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (BA-JEDI).

Overview

The perspectives within traditional Earth science disciplines coupled with various cultures and ethnic groups within the current undergraduate and professional populations are complex due to differing worldviews. Through the power of storytelling that links barriers to the participation of diverse students, faculty, and field research personnel in the Earth sciences, VOICES examines four elements of voice to research, develop, and disseminate a multifaceted approach to identify and support diversity leaders in the Earth sciences. VOICES combines social elements with science learning to create strategies for professional development for diversity leaders to teach them how to provide voice in their curricula, field activities, and related research activities in order to raise awareness of the complexity of diverse scholars’ perspectives. This approach recognizes intersectionality across groups but also encourages the integration of disaggregated knowledge of the diversity of individual cultures for successful strategies.

VOICES considers the four elements of Identity, Belonging, Place and Security, of which each element is situational (e.g., classroom or field activities) as well as highly individual. VOICE of Identity explores trends, patterns, and individual stories from Earth science professionals who represent diverse scholars and diverse groups. VOICE of Belonging focuses on structured social science research theory around a sense of belonging as an intervention for individual performance and identity. VOICE of Place considers local and regional power of place to provide cultural, historical, and national context of the role that place plays in Earth science, and it intersects with the VOICE of Identity. The element of Security focuses on developing long-term strategies for shifting current trends of diversity and inclusion and considers both emotional and physical security. Overall, the VOICES project offers an innovative approach to combine cultural constructions and intersectionality with discipline-specific recruitment, retention, recognition, and goals.

Power in asset-minded language

Words drive conversation, deepen understanding, and create relationships (Chen & Berger, Citation2013). Identifying and addressing deficit-derived language (e.g., minority) toward diverse peoples challenges the speaker to consider whom and what they are intending to communicate. This also allows for an accurate use of asset language to be used to describe diverse peoples (William, Citation2020). The language used to refer to or describe a group is of utmost importance as it is a silent signal as to the value placed on one’s knowledge or on the group as a whole. Deficit-based language is pervasive in mainstream society. While there has been push back from time to time, acknowledging the damage of deficit-minded language has never caught on as it has been difficult to facilitate change in current norms due to the low numbers of diverse scholars in Earth sciences (Burke, Citation2022). However, the time for that capacity to change has arrived, with an increase in diverse scholars, a boldness to amplify individual voices, and the advocacy of allies. We are at a juncture to facilitate change. Now that we have arrived at this juncture, we need to consider using language that does not “other” or set apart individuals with the intent to demean those from various racial and ethnic groups, those with different gender identities, and abilities. It remains bewildering to witness the resistance to change to make academia more welcoming, culturally aware, and to provide equitable education that is inclusive of all students.

Terminology and identity

Who are we and how do we want to be acknowledged? Language shapes perceptions that can perpetuate negative stereotypes, exclude, and dehumanize diverse peoples and language can build collaborative and respectful relationships with diverse scholars and communities (Brock & Haslam, Citation2010). For example, there is a robust body of literature that discusses the damage and offensive nature of the commonly used term minority to describe diverse scholars. The term remains common place without regard for the impacts and anguish this deficit-based term confers to these scholars (Ferguson, Citation2014; Lambert, Citation2020; Ly, Citation2011; Thurman, Citation2009; Visconti, Citation2006; William, Citation2020). This issue demonstrates how others see diverse scholars and how diverse scholars are trained by mainstream society to see ourselves (William, Citation2020). How does language impact the credibility and perceived intentionality of diverse scholars? Describing or introducing someone by their racial identity or disability type is an accepted and covert form of lateral violence that denounces one’s presence within a department, research group, or to meet a diversity initiative rather than for one’s scholarship. Oftentimes when this occurs diverse scholars are hesitant to advocate for themselves due to an imbalanced power dynamic (Korff, Citation2020; Mzinegiizhigo-kwe Bédard, Citation2018).

Individuals from diverse groups must be granted the autonomy to decide with whom and when to assert their identity if they choose to at all. Identity is an intangible feature that is owned by an individual and not to be used as a proclamation of a diversity initiative. It is common practice to use racial identifiers using proper nouns to describe a group as a monolith. This practice is harmful in its dismissiveness of the uniqueness of diverse populations. These descriptive synonyms are rooted in colonialism that embody numerous mistaken notions of an individual or group and fail to acknowledge the diversity within groups who often have their own concepts for themselves and those around them. It is important to know and acknowledge the differences in these groups and how these words are used to describe another human being. For example, the terms African American and Black are used interchangeably however these are very distinctive populations who may not share a history, culture, or world view. Even so, western society continually groups these distinctive populations as one based solely on phenotypic skin color (Ray, Citation2020). The same issue arises for Indigenous, Native American, American Indian, Alaska Native. What term is appropriate? How does one know how to address a group? The short answer here is ask the community. There is a western perception that indigeneity is owned resulting in Indigenous peoples often having their beinghood stripped away, mislabeled. Often there is a failure to address Indigenous people as a human, this is expressed through the misspelling of Indigenous as indigenous thereby removing beinghood. It is of utmost importance to address diverse individuals, groups, and populations correctly and with respect.

The practice of describing someone by their identity is rooted in racism, ableism, and pervasive negative stereotypes that perpetuate deficit assumptions that diverse scholars lack adequate education or are inferior due to limited physical, sensory, or cognitive ability (Atchison & Libarkin, Citation2016; Mzinegiizhigo-kwe Bédard, Citation2018; Carabajal & Atchison, Citation2020; Ford et al., Citation2001; Kingsbury et al., Citation2020; Parham et al., Citation2011; Rushton & Rushton, Citation2003; Walton & Carr, Citation2012). When the collective community of diverse scholars voice concern of the damaging effects of deficit assumptions, it is only reasonable to expect the broader academic corporate communities to be responsive, respectful, and equitable. The goal of VOICES is to ensure offensive terms are no longer used without question, without excuse, and without acts of performative contrition.

The VOICES approach to developing an inclusive Earth science culture

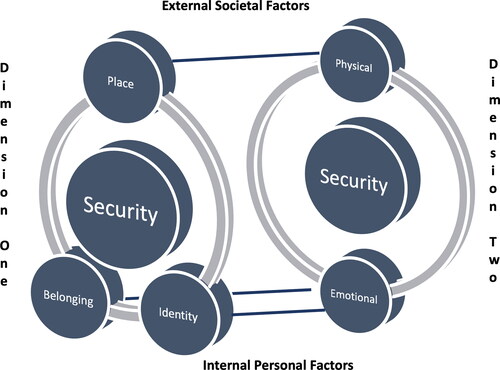

VOICES explores inclusion through the interconnected elements of Place, Belonging, and Identity, each of which impacts and informs an individual feelings of physical and emotional security in the Earth sciences (). The project integrates interactive Earth science experiences with social science behavioral approaches to build a network of diverse science scholars, and identify persistent issues preventing the retention, representation, and recruitment of different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups that are currently underrepresented in the Earth sciences.

Figure 1. The four elements of VOICES: Place, Identity, Belonging, and Security aiming to depict how an individuals sense of security is enhanced when their identity is acknowledged, when they belong, and when places of origin are recognized. An additional dimension of security has to consider the feelings of physical and emotional security brought by place and by belonging and identity.

Identity

Identity is a complex and fluid element that considers life experiences, beliefs, and cultural teachings. Cultural heritage is deeply ingrained and expressed through artistic expression, music, song, poetry, dance, and ceremony. Even so, Identity is connected to professional disciplines which are often stereotyped with specific ability, gender, and culturally specific norms which can negatively influence one’s self-identity as a scientist (Ballen et al., Citation2017; Davis et al., Citation2012; Halliwell et al., Citation2020; Smythe & Peele, Citation2021). This lack of efficacy becomes a barrier to recruitment and participation in the Earth sciences. One goal of VOICES is to empower diverse scholars to reclaim their voice that may have been passively silenced or superimposed with other identities that disaffirms their individual cultural identity (Miriti, Citation2019) while encouraging the concept and practice of power sharing to those who have retained their voice. Reclaiming and amplifying voice promotes an understanding of the intersectionality of diversity, culture, and ability that is needed to seed a cultural shift toward inclusion in traditional academic perspectives.

Belonging

Belonging focuses on an individual’s sense of belonging in the Earth sciences (Walton & Cohen, Citation2011). Belonging as a researcher, educator, and respected member of a disciplinary community has the potential to bring relief from “impostor syndrome” and is closely tied with Identity as measures of persistence in a discipline or academic field (Bressan, Citation2017; Freeman et al., Citation2007; Gopalan & Brady, Citation2020; Guillory & Wolverton, Citation2008; Smythe et al., Citation2020). Belonging can be characterized by individual declarations of being a member of a group, discipline, or project; while lack of belonging is often situational and captured by concepts of “otherness” or disconnection from a core group (Halliwell et al., Citation2020). For example, as field experiences are often unpredictable and conducted in locations with variable accessibility, students with disabilities are often faced with barriers to participation when decisions are made for them, without their voice being considered (Carabajal et al., Citation2017; Kingsbury et al., Citation2020; Stokes et al., Citation2019). Students with disabilities are often provided with alternative assignments that they complete individually without engaging in field activities (Carabajal et al., Citation2017) consequently missing the opportunity to interact with peers in a community of learning which is vital to developing critical thinking skills and the application of Earth science content (Atchison et al., Citation2019; Carabajal et al., Citation2017).

Place

Understanding sense of Place refers not only to ownership of land and water resources but to the spiritual, historical, and cultural connections to place (CEMA Task Group, 2015; Datta, Citation2015; Halliwell & Bowser, Citation2019; Russ et al., Citation2015). How do various groups align their understandings to the places and landscapes when in the field conducting research? How does the history of place inform Earth science research today? Recognizing that landscapes are associated with many cultures, placing an emphasis on the connection to culture and resident people can be elucidated by understanding the importance of Place and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) that is co-created with distinct protocols, histories, languages, and community practice (Bethel et al., Citation2014; Datta, Citation2015; Smythe et al., Citation2020; Smythe & Peele, Citation2021). It is important to understand and acknowledge what research sites mean to various groups. For example, a site considered a place of national pride for many may also be a place of pain, suffering, dispossession, slavery, loss of culture, and loss of language to members of Native and African American groups. History of Place considers the impact of the actions of Native Americans that inform Earth science research today, such as the mound sites across Louisiana that were constructed thousands of years ago (Louisiana Division of Archaeology, Citation2014). Acknowledging that these structures changed the landscape, and subsequently the geochemistry, soil chemistry, and geology that is the focus of research today (Kean, Citation2019). Understanding what TEK systems are and how they are constructed both locally and regionally inform research interpretation and practices to allow for accurate meaning making of results, as cultural practices of Indigenous peoples had and continue to have an impact on the landscape and ecosystems all of which continue to impact scientific studies today. TEK is a separate knowledge system of which there is no single definition, rather TEK is based on a spectrum of beliefs, values, and perceptions that include the voices of Indigenous peoples regarding their ancestral lands or those of urban dwellers connected to historic and cultural struggles such as environmental justice and civil rights (Hoagland, Citation2017; Russ et al., Citation2015; Smythe et al., Citation2020; Smythe & Peele, Citation2021; Tulshyan, Citation2019; Writer, Citation2008). Landscapes have culture and the characteristics of a landscape are multifaceted and yet essential to understanding concepts of “special places” (Halliwell & Bowser, Citation2019).

Security

Sense of Security is situational and highly unique to an individual scholar’s personal experiences and identity. While security is synonymous with safety in some situations, these terms have distinctive meanings when viewed through the lens of culture, ability, gender, race, and sexual orientation. Safety specific to geoscience field work has been presented in the context of risk to one’s physical health (Cantine, Citation2022; Sohn, Citation2016, Citation2017; Orr, Citation2017). As such, security and safety are presented separately, while keeping them closely aligned by adding to the inherent risk associated with one’s social-emotional well-being. Security is an effective voice influenced by the elements of Identity, Belonging, and Place and is critical for creating equitable pathways to learning and research experiences in the Earth sciences for diverse scholars.

Intersection of VOICES

Acknowledging how Place ties to participation in field experiences is also associated with Belonging and Identity, the combination of which can lead to self-confidence associated with learning gains and long-term engagement and retention in the Earth sciences (Beltran et al., Citation2020; Marshall, Citation2018; Streule & Craig, Citation2016; Walton & Cohen, Citation2011).

The element of Security is complex and solely based on personal and situational experiences and perspectives, while being closely aligned with multiple facets of an individual’s intersecting identities. Sense of Security is informed equally by an individual’s sense of Belonging, Identity, and Place. For example, possessing a strong sense of Identity without Belonging and connection to Place can drastically diminish one’s sense of Security when engaging in a new field experience in an unfamiliar setting and location (Buchanan & Wiklund, Citation2021; Byars-Winston & Rogers, Citation2019).

The intersection of the elements of Belonging, Identity, Place and Security creates a two-dimensional framework (). Dimension One influences personal internal factors and provides both emotional and physical security for Earth scientists, and can have an immediate impact on both diverse scholars and the broader Earth science community. Acknowledging and accepting the unique differences, strengths, and abilities offered by diverse scholars increases environmental justice through developing critical thinking skills, and enhancing innovation with collaborative problem solving of local, regional, and global real-world issues.

Figure 2. Two-dimensional framework illustrating the intersection of the elements of Place, Belonging, Identity and how they impact emotional and physical Security.

Dimension Two is based on external professional factors such as the Earth science discipline, academia, industry, and other work spaces that result from cultural shifts and changing attitudes with the retention and subsequent increase of diverse scholars in the Earth sciences. A sense of Belonging within a peer group or sharing a cultural connection with another individual allows for a student to possess emotional Security (Martinez-Cola, Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2018). Physical Security for diverse scholars can be situational, especially during field experiences while working in different regions of the country or when encountering the privilege and power of a dominant demographic, and can have detrimental and sometimes violent outcomes.

Implications and a way forward

Increasing the diversity of representation and overall inclusivity in Earth science requires recognizing, accepting, and empowering the full range of identities one brings to the discipline. Doing so requires work by the entire community, at both the individual and the collective levels. In Ali et al. (Citation2021), the authors emphasize the central importance of developing actionable policies and procedures, requiring institutional accountability, and moving beyond simple statements of support. When strategies are viewed and designed through the lens of justice, equity, and anti-racist practices and combatting discrimination, real and effective change can be achieved and sustained. There are tremendous benefits to achieving these goals because when individuals cannot bring all of themselves to the STEM enterprise we risk losing ideas, creative strategies and solutions for solving 21st century environmental problems.

VOICES explores the interconnected elements and impacts of an individual’s Identity, sense of Belonging, history and cultural connections to Place, and sense of emotional and physical Security creating a multidimensional framework for diversifying the Earth sciences. Internal factors are one dimension and examine an individual’s personal perceptions. These factors consider the voice of Identity where diverse scholars recognize the power, responsibility, and right to own their identity. They inform the voice of Belonging in the Earth sciences and bring with it emotional Security in academic and cultural spaces. Equally important, external factors are a second dimension that examines historical and cultural connections to Place and connects to the need for Earth scientists to have physical Security in all social and academic contexts. Understanding and acknowledging the importance of these four elements can positively impact the recruitment and retention of diverse scholars, create equitable academic and field research practices and opportunities, create welcoming environments in the Earth sciences, and bring fresh perspectives and worldviews to the Earth sciences enhancing creativity, problem solving, and scientific innovation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Gillian Bowser, Richard Harvey, and Nina Roberts. Thanks to Jana Towne, Christopher Ramos, and Chessaly Towne for their assistance with figure readability.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ali, H. N., Sheffield, S. L., Bauer, J. E., Caballero-Gill, R. P., Gasparini, N. M., Libarkin, J., Gonzales, K. K., Willenbring, J., Amir-Lin, E., Cisneros, J., Desai, D., Erwin, M., Gallant, E., Gomez, K. J., Keisling, B. A., Mahon, R., Marín-Spiotta, E., Welcome, L., & Schneider, B. (2021). An actionable anti-racism plan for geoscience organizations. Nature Communications, 12(1), 3794. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23936-w

- Atchison, C L., & Libarkin, J. C. (2016). Professionally held perceptions about the accessibility of the geosciences. Geosphere, 12(4), 1154–1165. https://doi.org/10.1130/GES01264.1

- Atchison, C. L., Parker, W. G., Riggs, N. R., Semken, S., & Whitmeyer, S. J. (2019). Accessibility and inclusion in the field: A field guide for central Arizona and Petrified Forest National Park. In P. A. Pearthree (Ed.), GSA phoenix field guides: Geological society of America field guide 55 (pp. 39–60). The Geological Society of America. https://doi.org/10.1130/2019.0055(02)

- Ballen, C. J., Wieman, C., Salehi, S., Searle, J. B., & Zamudio, K. R. (2017). Enhancing diversity in undergraduate science: Self-efficacy drives performance gains with active learning. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(4), ar56. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-12-0344

- Bell, R., White, L. (2020). The geosciences community needs to be more diverse and inclusive. Scientific American. blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/the-geosciences-community-needs-to-be-more-diverse-and-inclusive/

- Beltran, R. S., Marnocha, E., Race, A., Croll, D. A., Dayton, G. H., & Zavaleta, E. S. (2020). Field courses narrow demographic achievement gaps in ecology and evolutionary biology. Ecology and Evolution, 10(12), 5184–5196. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6300

- Bethel, M. B., Brien, L. F., Esposito, M. M., Miller, C. T., Buras, H. S., Laska, S. B., Philippe, R., Peterson, K. J., & Richards, C. P. (2014). Sci-TEK: A GIS-based multidisciplinary method for incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into Louisiana’s coastal restoration decision-making processes. Journal of Coastal Research, 30(5), 1081–1099. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-13-00214.1

- Bowser, G., & Cid, C. (2021). Developing the ecological scientist mindset among underrepresented students in ecology fields. Ecological Applications: A Publication of the Ecological Society of America, 31(6), e02348. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2348

- Bressan, D. (2017). Indigenous knowledge helps scientists to assess climate change. Forbes Media LLC. forbes.com/sites/davidbressan/2017/07/05/indigenous-knowledge-helps-scientists-to-assess-climate-change/#2ab192b15527

- Brock, B., & Haslam, N. (2010). Excluded from humanity: The dehumanizing effects of social ostracism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.06.022

- Buchanan, N. T., & Wiklund, L. O. (2021). Intersectionality research in psychological science: Resisting the tendency to disconnect, dilute, and depoliticize. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00748-y

- Burke, L. E. C. A. (2022). Foregrounding intersectionality in considerations of diversity: Confronting discrimination in science teacher education. Research in Science Education, 52(4), 1157–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-021-10001-1

- Byars-Winston, A., & Rogers, J. G. (2019). Testing intersectionality of race/ethnicity × gender in a social–cognitive career theory model with science identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000309

- Cantine, M. (2022). Playing it safe in field science. EOS. American Geophysical Union. https://eos.org/opinions/playing-it-safe-in-field-science

- Carabajal, I. G., & Atchison, C. L. (2020). An investigation of accessible and inclusive instructional field practices in US geoscience departments. Advances in Geosciences, 53, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-53-53-2020

- Carabajal, I. G., Marshall, A. M., & Atchison, C. L. (2017). A synthesis of access and inclusion in geoscience education literature. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65(4), 531–541. https://doi.org/10.5408/16-211.1

- CEMA Task Group. (2015). CEMA indigenous traditional knowledge framework project: Indigenous traditional knowledge framework. C. Candler, & D. Thompson (Eds.). The Firelight Group Report.

- Chen, Z., & Berger, J. (2013). When, why, and how controversy causes conversation. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(3), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1086/671465

- Datta, R. (2015). A relational theoretical framework and meaning of land, nature, and sustainability for research with Indigenous communities. Local Environment, 20(1), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.818957

- Davis, E., Bowser, G., & Brown, M. A. (2012). The Global Mindset: Engaging multicultural students in multidimensional learning. In D. R. Gallaher (Ed.), Environmental leadership in practice: a reference handbook (Vol. 2, pp. 891–899). Sage Publications.

- Estrada, M., Burnett, M., Campbell, A. G., Campbell, P. B., Denetclaw, W. F., Gutiérrez, C. G., Hurtado, A., John, G. H., Matsui, J., McGee, R., Okpodu, C. M., Robinson, T. J., Summers, M. F., Werner-Washburne, M., & Zavala, M. (2016). Improving underrepresented minority student persistence in STEM. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(3), es5. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0038

- Ferguson, H. E. (2014). Why the term “minority” is problematic. blackyouthproject.com/why-the-term-minority-is-problematic/

- Ford, D. Y., Harris, J. J., III, Tyson, C. A., & Frazier Trotman, M. (2001). Beyond deficit thinking: Providing access for gifted African American students. Roeper Review, 24(2), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190209554129

- Freeman, T. M., Anderman, L. H., & Jensen, J. M. (2007). Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and campus levels. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.203-220

- Gomez, K., Gomez, L. M., & Worsley, M. (2021). Interrogating the role of CSCL in diversity, equity, and inclusion. In U. Cress, C. Rosé, A. F. Wise, & J. Oshima (Eds.), International handbook of computer-supported collaborative learning. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Series (vol 19, pp. 104–110). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65291-3_6

- Gopalan, M., & Brady, S. T. (2020). College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19897622

- Guillory, R. M., & Wolverton, M. (2008). It’s about family: Native American student persistence in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(1), 58–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2008.0001

- Halliwell, P., & Bowser, G. (2019). A diverse sense of place: Citizen science as a tool to connect underrepresented students to science and the national parks. Mountain Views Cirmount, 13(1), 4–8.

- Halliwell, P., Whipple, S., & Bowser, G. (2020). 21st century climate education: Developing diverse, confident, and competent leaders in environmental sustainability. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 101(2), e01664. https://doi.org/10.1002/bes2.1664

- Hoagland, S. J. (2017). Integrating traditional ecological knowledge with western science for optimal resource management. IK: Other Ways of Knowing, 3(1), 1–15. doi. https://doi.org/10.189113/P8ik359744

- Kean, S. (2019). Historians expose early scientists’ debt to the slave trade. AAAS Science, April 4, 2019. Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax5704

- Kingsbury, C. G., Sibert, E. C., Killingback, Z., & Atchison, C. L. (2020). “Nothing about us without us:” The perspectives of Autistic geoscientists on inclusive instructional practices in geoscience education. Journal of Geoscience Education, 68(4), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2020.1768017

- Korff, J. (2020). Bullying and lateral violence. Creative Spirits. creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/people/bullying-lateral-violence

- Lambert, R. (2020). There is nothing minor about us: Why forbes won’t use the term minority to classify black and brown people. Forbes. forbes.com/sites/rashaadlambert/2020/10/08/there-is-nothing-minor-about-us-why-forbes-wont-use-the-term-minority-to-classify-black-and-brown-people/?sh=2ed5d4957e21

- Louisiana Division of Archaeology. (2014). Poverty point. In Discover archaeology. Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. crt.state.la.us/cultural-development/archaeology/discover-archaeology/pover-ty-point/

- Ly, P. (2011). As people of color become a majority, Is the time for journalists to stop using the term “minorities”? Poynter. www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2011/as-people-of-color-become-a-majority-is-it-time-for-journalists-to-stop-using-the-term-minorities/

- Marshall, A. (2018). Moving forward: Overcoming our ideas about disability in Geosciences. Speaking of Geoscience, The Geological Society of America Blog. https://speakingofgeoscience.org/2018/10/08/moving-forward-overcoming-our-ideas-about-disability-in-the-geosciences/

- Martinez-Cola, M. (2020). Collectors, nightlights and allies, Oh my! White mentors in the academy. Understanding and Dismantling Privilege, 10(1), 26–56.

- Miriti, M. (2019). Nature in the eye of the beholder: A case study for cultural humility as a strategy to broaden participation in STEM. Education Science, 9(4), 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040291

- Mzinegiizhigo-kwe Bédard, R. E. (2018). “Indian in the cupboard” lateral violence and indigenization of the academy. In C. Cho, J. Corkett, & A. Steele (Eds.), Exploring the toxicity of lateral violence and microaggressions (pp. 75–101). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Orr, E. (2017). Put safety first. Nature, 551, 663–665. doi. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-017-07529-6

- Parham, T. A., Anderson, A., & White, J. L. (2011). The psychology of blacks: Centering our perspectives in the African consciousness. Routledge Press.

- Ray, R. (2020). Black American are not a monolithic group so stop treating us like one. The Guardian, US Politics. theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/14/black-americans-are-not-a-monolithic-group-so-stop-treating-us-like-one

- Rushton, J., & Rushton, E. W. (2003). Brain size, IQ and racial-group differences: Evidence from musculoskeletal traits. Intelligence, 31(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040291

- Russ, A., Peters, S. J., Krasny, M. E., & Stedman, R. C. (2015). Development of ecological place meaning in New York City. The Journal of Environmental Education, 46(2), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2014.999743

- Sheffield, S. L., Cook, M. L., Ricchezza, V. J., Rocabado, G. A., & Akiwumi, F. A. (2021). Perceptions of scientists held by US students can be broadened through inclusive classroom interventions. Communications Earth & Environment, 2(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00156-0

- Smythe, W. F., Clarke, J. B., Hammack, R., & Poitra, C. (2020). Native perspectives about coupling indigenous traditional knowledge with western science in geoscience education from a focus group study. Global Research in Higher Education, 3(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.22158/grhe.v3n2p10

- Smythe, W. F., & Peele, S. S. (2021). The (un)discovering of ecology by an Alaska Native ecologist. Ecological Applications, 31(6), e02354. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2354

- Sohn, E. (2016). Fieldwork: Extreme research. Nature, 529, 243–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7585-243a

- Sohn, E. (2017). Health and safety: Danger zone. Nature, 541, 247–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7636-247a

- Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. The American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613

- Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797

- Stokes, A., Feig, A., Atchison, C. L., & Gilley, B. H. (2019). Making geoscience fieldwork inclusive and accessible for students with disabilities. Geosphere, 15(6), 1809–1825. https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02006.1

- Streule, M., & Craig, L. (2016). Social learning theories-an important design consideration for geoscience fieldwork. Journal of Geoscience Education, 64(2), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.5408/15-119.1

- Syed, M., Zurbriggen, E. L., Chemers, M. M., Goza, B. K., Bearman, S., Crosby, F. J., Shaw, J., Hunter, L., & Morgan, E. M. (2019). The role of self-efficacy and identity in mediating the effects of STEM support experiences. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy: ASAP, 19(1), 7–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12170

- Taylor, D. E. (2018). Racial and ethnic differences in the students’ readiness, identity, perceptions of institutional diversity, and desire to join the environmental workforce. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 8(2), 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-017-0447-4

- Thurman, R. (2009). Why I wish nonprofits would stop using the word “minorities”. Sandford Social Innovation Review. ssir.org/articles/entry/why_i_wish_nonprofits_would_stop_using_the_word_minorities

- Tulshyan, R. (2019). Do your diversity efforts reflect the experiences of women of color? Harvard Business Review. hbr.org/2019/07/do-your-diversity-efforts-reflect-the-experiences-of-women-of-color#comment-section

- Visconti, L. (2006). Should you use the word “minority”. DiversityInc. www.diversityinc.com/should-you-use-the-word-minority/

- Walton, G. M., & Carr, P. B. (2012). Social belonging and the motivation and intellectual achievement of negatively stereotyped students. In M. Inzlicht & T. Schmader (Eds.), Stereotype threat: Theory, process, and application (pp. 89–106). Oxford University Press.

- Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science (New York, N.Y.), 331(6023), 1447–1451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198364

- White, L. D., Pagnac, D., & Bowser, G. (2019, October 9). Fieldwork Inspiring Expanded Leadership and Diversity (FIELD): Overcoming barriers to fieldwork in paleontology. [Paper presentation]. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts, 2019 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 79th Annual Meeting, Brisbane, Australia.

- White, L., & Bell, R. (2019). Why diversity matters to AGU. Eos, 100. Published on 01 December 2019. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO136457

- William, T. L. (2020). Underrepresented minority considered harmful, racist language. Communications of the ACM. cacm.acm.org/blogs/blog-cacm/245710-underrepresented-minority-considered-harmful-racist-language/fulltext

- Writer, J. H. (2008). Unmasking, exposing, and confronting: Critical race theory, tribal critical race theory and multicultural education. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 10(2), 1–15.

- Yoder, B. L. (2016). Engineering by the numbers. In Engineering college profile and statistics book (pp. 11–47). American Society for Engineering Ed.