ABSTRACT

This article presents an ethnography of listening behavior in Japanese interactions. In research on listeners’ behavior, academics have tended to focus on actions and gestures directly related to the ongoing conversation. In reality in everyday life, however, listeners often multitask. This study, therefore, attempts to investigate the nature of listeners’ multi-activities in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of their involvements. It particularly focuses on a type of listening behavior I refer to as “nagara listening,” whereby the listener is involved in various other actions and gestures while listening. This type of listening behavior involves tacit rules that enable the conversation to run smoothly.

Introduction

In everyday situations, listeners are often engaged in multi-activity behaviors such as eating, cooking, or looking at something while conversing. Therefore listeners’ behavior consists of two types of actions: those which are directly related to the ongoing interaction, and those which are not related to it but occur at the same moment. Existing research on listeners’ behavior tends to focus on the former types: gestures, postures and gaze (Goodwin, Citation1984, Citation2009; Heath, Citation1986), head nod (Stivers, Citation2008), facial expressions (Brunner, Citation1979; Kaukomaa et al., Citation2015), verbal responses such as claims of understanding, questions and minimal responses (Bavelas et al., Citation2000; Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2012; Holt, Citation1993; Kraut et al., Citation1982; Kushida, Citation2009; Ueno, Citation2011), aizuchi (Japanese minimal responses) (Imaishi, Citation1993; Kita & Ide, Citation2007; Szatrowski, Citation2000), interactional alignment and affiliation (Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2012; Stivers, Citation2008), and emotional display e.g., surprise, affirmation and indignation (Heath et al., Citation2012; Maynard & Freese, Citation2012; Wilkinson & Kitzinger, Citation2006). These investigations overlook two important aspects that are very much part of listeners’ behavior: multitasking and involvements and gestures that do not necessarily relate to ongoing utterances.

Only a few researchers have explored these two aspects. Heath (Citation1986, pp. 50, 61) describes ways in which doctors engage in a multitude of other activities in front of patients while listening to them during medical examinations. These include “conducting physical examinations, reading and writing the medical record cards, and issuing prescriptions, sick notes and the like.” Heath scrutinizes speakers’ management of gaining an appropriate level of attention from multi-tasking listeners, however his research is limited to a few comments on listeners’ multitasking. Similarly, Goodwin (Citation1984, p. 227) briefly mentions that during dinner conversational participants always engage in a variety of other activities, including eating, distributing food, and taking care of children. Goodwin (Citation2009) also analyzes a conversation between a little girl and her aunt during which the girl is reading a recipe for baking cookies, thus delineating listeners’ multi-activities. However, because he studies how speakers change their utterance through observing listeners’ displays, he does not develop the meanings of listeners’ multitasking or the effects of listeners’ other involvements on the conversation. Therefore, although researchers have previously identified the wide range of listeners’ multi-layered behavior in natural settings, their actions and gestures are still not understood as a whole.

In an experimental setting, Bavelas et al. (Citation2000) gave participants different tasks such as listening in order to summarize, listening while counting holidays, and listening while counting the number of words a narrator said beginning with the letter ‘t.’ The listeners with the counting tasks made significantly fewer generic responses (e.g., back-channels) and specific responses (e.g., mirroring the speaker’s gesture or replying with a phrase directly connected to what the narrator has said), which had an adverse effect on the speaker’s story-telling process. However, the study points out that while engaging in conversations, listeners are capable of dealing with several demands simultaneously as long as they attend to narrative meanings. In my research, I would like to suggest the possibility that listeners’ simultaneous actions and gestures sometimes even help interlocutors to conduct smooth conversations, especially in Japanese cultural contexts.

A few studies focus on the type of multitasking that happens during social interaction and point out that this type of reseach has been largely ignored by researchers (Haddington et al., Citation2014, p. 5). These studies include social TV viewing, driving while conversing, and workplace multitasking, using either a quantitative approach or ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (Haddington et al., Citation2014; Hilde & Viswanathan, Citation2015; Mark et al., Citation2015; Kushniryk & Levine, Citation2012). Especially in studies that use the latter methods, some examples can be interpreted as descriptions of listeners’ multiactivity, but the research mainly focuses on speakers’ multi-activities and are limited to understandings of conversational and behavioral functions.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of listeners’ behavior, this paper analyzes a type of listening that most listeners acquire naturally: being involved in several other actions and gestures while listening in interactions. This behavior appears to facilitate smooth communication, although it is difficult to determine if this is conscious or unconscious. I name this “nagara listening” (in Japanese nagara is attached to verbs to describe actions/gestures that take place at the same time). Firstly, I will define what this listening is and elaborate on the concept by explaining the limitations of existing theories, and then I will proceed to discuss the reasons that interlocutors engage in such listening based on my observations in Japanese contexts. Finally, I will scrutinize the factors that may influence the degree and types of nagara listening.

My theoretical frameworks draw on the notion of tacit rules in Erving Goffman’s argument (Goffman, Citation1990) and the “habitus of listening” in Judith Becker’s explanation (Becker, Citation2010). Goffman (Citation1990) notes that actors/performers have tacit consent to manage a situation and skillfully express themselves before audiences. Even though listeners are often considered to be audiences, they must also perform as listeners in a way that accords with the tacit rules in Goffman’s sense. One of the tacit rules for listeners can be nagara listening, because they appear to skillfully and instinctively manage a situation through such listening. Nagara listening can also be considered a “habitus of listening.” Adopting the term “habitus” from Pierre Bourdieu, Becker (Citation2010 pp. 129–130) explains that people listen in a particular way without noticing that it is a specific kind of listening; he calls this “tacit, unexamined, seemingly completely ‘natural’” way of listening a “habitus of listening” that is influenced by place, time, culture, and personal biography. Similarly, nagara listening is a particular way of listening influenced by cultural and personal codes, and listeners naturally embody this listening. In this paper, I wish to establish the concept of nagara listening to understand listeners’ unwritten rules in everyday life.

In order to achieve this, I carried out both covert and overt fieldwork. The former involved observation in a café, restaurant, bars and university lectures, while the latter was carried out while working in a hostess club (night club) and by taking part in volunteer listening groups. In addition, I observed conversations in Japanese TV dramas. Based on these observations, I produced ethnographic data and analyzed them using domain and taxonomic analysis (Spradley, Citation1980).

Nagara listening – An intrinsic part of listening behavior

A typical example of nagara listening takes place on a sunny day at a Starbucks store in Tokyo. Two women in their fifties meet for a late-morning coffee and sit next to each other on a sofa. One of them touches her smartphone in front of her on the table with her left hand, then combs her hair with that same hand, grabs a fork on a plate in her right hand, and eats a slice of chocolate cake, all while she listens to her friend explaining an app on her phone. She turns her face to her friend and then looks at the chocolate cake again. She crosses both hands on her lap, looks at her friend’s smartphone, nods and mumbles “hō,” while her friend keeps talking about the app. She drinks her coffee and then rests her left elbow on her bag, which is placed next to her on the sofa, and cups her chin in the palm of her right hand. With her right hand she scratches the right side of her short hair and nods while turning to face her friend again (22/01/2016).

In this example, at the same time as listening to each other, responding verbally, nodding and thinking about the topic, these two friends drank coffee, ate cake, checked their smartphones, touched their hair, and changed their posture. In Japanese, actions/gestures that take place at the same time can be expressed in the form of “stem of verb + nagara” to describe “while doing” followed by the verb describing the main activity in its usual grammatical form. For example, kōhī o nomi-nagara hanashi o kiku (listening while drinking coffee), where nomi is the stem of the verb nomu “to drink.” This type of nagara activity is one of the main characteristics of listeners’ behavior.

Establishing a theoretical framework

Goffman’s involvement theory and Hall’s concept of polychronic/monochronic-culture serve as analytical perspectives to refine the idea of nagara listening and to show how, in contrast with their theories, nagara listening consists of both hierarchical and nonhierarchical actions and gestures.

Goffman (Citation1966) introduced the concept of “main and side involvements” and “dominant and subordinate involvements.” A main involvement is the focus of a person’s attention, and a side involvement is an activity that can be conducted in a casual manner without disturbing the main activity, such as “humming while working and knitting while listening” (Goffman, Citation1966, p. 43). By contrast, a dominant involvement is determined by the social situation within the social roles; it is an involvement that the social occasion requires the person to be ready to recognize. On the other hand, a subordinate involvement is an activity in which people can be engaged when their attention is not required by the dominant involvement. For example, “while waiting to see an official, an individual may converse with a friend, read a magazine, or doodle with a pencil, sustaining these engrossing claims on attention only until his turn is called” (Goffman, Citation1966, p. 44).

In the previous example of two women in a coffee shop, listening to her friend explaining an app on her smartphone is the main and dominant involvement for the listener, because the social situation requires her to show her attention as a friend. As side and subordinate involvements, she also drinks coffee, combs her hair, eats chocolate cake, crosses both hands on her lap, and cups her chin in her hand. Goffman’s framework helps in delineating how listeners skillfully juggle their various involvements.

However, listeners do not always prioritize one behavior over others in the way that Goffman’s theory describes. Listeners sometimes perform several actions/gestures without any obvious prioritization, or may be engaged in involvements which can be viewed as main and dominant involvements from one perspective, but as side involvements from another.

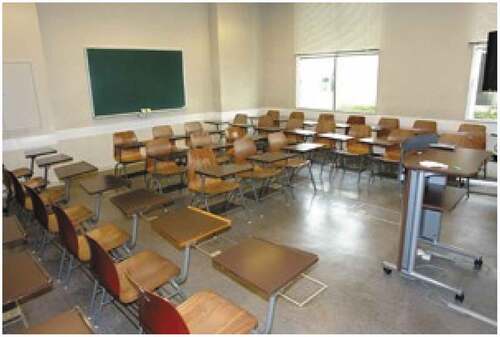

For example, my fieldwork notes from visiting Keio University describe seven people (four female students, two male students and a male professor) sitting in a seminar room (14/01/2016). The room on the ground floor is approximately 30 square meters in size and has 40 chairs (). A strict hierarchy exists between the professor and the students. During the seminar, a female student nods and says “un un” in a small voice. The professor asks, “This means …, doesn’t it?” and she replies “hai” (yes), takes notes, leafs through a book, and uses a smartphone to check a German word in an online dictionary. Additionally, all four of the female students smile or laugh when the professor smiles or laughs.

In this case, listening to the professor is the main and dominant involvement. If listening is prioritized, looking at an online dictionary can be considered a side involvement. However, because the student understands the necessity of looking up the word, this activity can also be understood as a main involvement. Smiling and laughing can also be seen as either main and side activities; they are not strictly related to the subject of the seminar but they can be viewed as an obligatory part of attending and taking part in the seminar. In this way, multiple other activities can become main involvements.

Similarly, in the TV drama “Around 40: Women with many demands” (Setoguchi & Takanari, Citation2008), a 40-year-old female doctor, Satoko, works at a hospital. Satoko’s younger friend, Nao, visits her during working hours and they talk in the hospital office sitting next to each other on a sofa in front of a low table (8:50–9:25, episode 1). Nao shows Satoko a black dress and persuades her to wear it to an alumni party to show that she is living a happy single life. Satoko listens to her and tidies up medical papers on the table. When Nao explains that an alumni party is a place to confirm how happy you have become, Satoko looks surprised and says “Sō na no?” (Is that so?), while putting a pen that is in her right hand into the left chest pocket of her lab coat.

It is not clear what the main or dominant involvement is for Satoko. As a doctor, tidying up and putting a pen in her pocket could be regarded as the main and dominant involvements, and listening to Nao as a side and subordinate involvement. However, in her role as a friend, listening and responding to Nao could be seen as the main and dominant involvement, with tidying up and placing a pen as side and subordinate involvements. This reflects the nonhierarchical nature of these involvements in this particular situation. In these two cases, nagara listening transcends Goffman’s categorization and provides a means of approaching both hierarchical and nonhierarchical involvements.

Hall’s (Citation1983, pp. 45–54) “polychronic/monochronic culture” is sometimes used in analyses of multitasking behavior. He describes how compared to people in a monochronic culture such as Northern Europe and North America who prefer to focus on one task at a time, people in polychronic cultures, such as Latin America and Asia, typically carry out multitasking or make several appointments simultaneously. A major drawback of Hall’s theory for understanding listeners’ behavior is that due to listeners’ multiactivity, no society can be truly considered a monochronic culture.

Furthermore, his theory deals only with tasks and actions, and not with unintentional momentary body movements and intentional gestures, such as turning one’s face and eye contact. “Task” means “a piece of work to be done or undertaken” (Oxford Dictionary of English, Citation2010), so his study is limited to jobs, duties, and actions and does not include intentional or voluntary gestures. However, nagara listening can include both aspects. For the same reason, nagara listening cannot simply equate to multitask-listening. Moreover, since Hall makes no mention of a hierarchy of tasks or gestures, his theory only comprises nonhierarchical multitasking.

Thus, Goffman’s concept explains involvements, including actions and gestures, only as hierarchical behavior, whereas Hall’s notions of polychronic/monochronic-culture treats involvements only as nonhierarchical actions and excludes gestures. Consequently, both theories have limitations when applied to an analysis of listening behavior. Therefore, nagara listening, which includes both hierarchical and nonhierarchical actions and gestures, can be viewed as a useful extension of these two theories.

Creating an appropriate distance

Adjusting self-investment

Why do listeners act in this complicated way? One possibility is that nagara listeners are attempting to create and regulate a comfortable psychological distance between themselves and their interlocutors by means of various actions and gestures, thereby creating a smooth conversation.

In an interaction, people communicate in a way that is appropriate to the situation; this has been described as the rule of “situational proprieties” (Goffman, Citation1966, p. 24). Listeners act so as to maintain harmony; they do not attract undue attention to themselves, but also do not avoid attention. They also adjust their degree of focus on speakers: they may increase their attention to speakers by looking at them, or they may reduce the level of attention by conducting side or other main involvements, which allow them to look away from the speaker.

An example of such balanced attention by nagara listeners in a serious and potentially embarrassing conversation can be seen in the Japanese TV drama “Around 40” (Setoguchi & Takanari, Citation2008) in which a father talks with Satoko, his grown-up daughter, in his medical examination room at night (Episode 1, 28:00–29:33). The father, while standing and replenishing medical equipment in a desk drawer, says to his daughter who is sitting on a chair, “I’m surprised that you’re becoming more and more like your mother [who passed away].” He glances at her only once. Satoko says, “Ehh?” and looks at her father with mild surprise, “Do I really look that old? Please stop it!” Her father gives a slight smile. They have brief eye contact and the father walks to the other desk. Satoko says, “That’s right. She passed away when she was 40, didn’t she? I’ll soon be that old, but I don’t feel as though I am at all.” She stands up, follows her father, and leans against a shelf in front of him. He replies: “Tatsuya [her younger brother] talks as though he raised himself to be an adult, but you acted just like a substitute mother for him.” He tidies the books on the shelves, crouching down without making eye contact. Then he stands up, moves to a desk, and glancing at his daughter, says, “You have only known heavy responsibility.” He sits down on a chair, and begins to work on a paper while listening to her. She replies, “What’s this, all of a sudden? It was difficult for you too, wasn’t it? […]” and continues talking while looking at her father. He carries on working, looking at Satoko just once when replying, but generally directing his gaze to his desk as a listener. He tries to find a pen on his desk. Satoko, while listening, finds and gives a pen to her father. He replies, “That’s why you don’t find it easy to be indulged.” She responds, “I’m relying on this household now. I’ve come round here to eat three times this week.” Without looking up at her, he makes his final comment, “Well, all the while that we can.” And then he looks up at her.

In this example, to regulate the seriousness of their conversation, the father, both as a speaker and a listener, demonstrates his balanced self-investment by his nagara activities. He continues his work and divides his self-investment into several activities, which creates the impression that the topic of conversation is not especially serious. He does not look at Satoko, apart from a few glances. However, as many Japanese avoid looking at each other in a serious conversation (Sugiyama, Citation1976, p. 48), the lack of eye contact can connote his seriousness too. In this way, nagara activities assist in achieving a balancing between the casual and serious aspects of a conversation.

The concept of “margins of disinvolvement,” which describes how people often make a show of not completely focusing on one activity (Goffman, Citation1966, p. 60), helps in understanding nagara listeners, as in the case of the father above. In accordance with this tacit rule, people show that they are not entirely invested in the main involvement by maintaining a “slight margin of self-command and self-possession” in order to demonstrate an “appropriate” degree of self-investment, except in the case of activities such as exams and sporting competitions. For example, when a man slips on the road, he reacts with a little smile on his face, which shows his “margin of disinvolvement” to the fact that he has slipped (Goffman, Citation1966, p. 60). English people often feign not to be too earnest in their work or even during exams; when they speak they understand the rule of “not being too earnest,” and their listeners understand whether they are being earnest or not (Fox, Citation2005, pp. 62, 180). In the same way that listeners understand the speakers’ margin of disinvolvement in such situations, speakers may understand the listeners’ margin of disinvolvement conveyed by nagara listening. Goodwin (Citation1984, p. 232) states that in multitasking situations “the rule that a recipient should be gazing at a gazing speaker may be relaxed, permitting the recipient to look away and attend to competing activities;” So while nagara listeners maintain a margin of self-possession, other interlocutors permit it.

Just as an appropriate self-investment does not signify a complete investment of the self, overly attentive listening does not always mean that listeners listen well. According to Sartre (Citation1957, p. 60): “The attentive pupil who wishes to be attentive, his eyes riveted on the teacher, his ears open wide, so exhausts himself in playing the attentive role that he ends up by no longer hearing anything.” In the original French text, Sartre (Citation1943) uses the word “écouter” (to listen) rather than “entendre” (to hear), so a more literal translation would be “he ends up by no longer listening to anything.” A possible reason for this failure is that listeners’ “currently available central processing capacity” (Imhof, Citation1998) is limited and hence people become saturated and fatigued. Bavelas et al. (Citation2000) also conclude that an increase in cognitive demand does not improve listeners’ responses. Therefore, listeners do not necessarily need to invest themselves intensively to listen well.

Moreover, Heath (Citation1986 pp. 161–162) suggests the possibility that doctors’ multitasking during medical examinations may serve as an opportunity for patients to disclose embarrassing information when the doctors look away. Therefore, listeners are not only allowed to avoid giving their full attention to a speaker, but also sometimes need to do so through nagara activities to ensure a smooth conversation.

Auxiliary artifacts

Nagara listeners often use small material things, which serve as a focus for hands and eyes and help to manage their balanced attention and maintain a smooth conversation. In cafés in Tokyo I found examples such as: listening while touching a cup, holding a fork to eat, using a smartphone or laptop, toying with one’s hair/lip/ears/neck/arms/nails, using a pen to write memos, spinning a pen, rocking a pram, and removing a wristwatch. Through observing customers in bars in San Fransisco, Cavan (Citation1966, p. 57) also confirms that toying with a glass or ashtray functions to create a smooth conversation. I refer to these objects as “auxiliary artifacts.”

Auxiliary artifacts differ from both “safe supplies” and “social facilitators.” “Safe supplies” (Goffman, Citation1966, pp. 103, 154) refer to innocuous topics of conversation or activities such as knitting or smoking a pipe that interlocutors engage in to avoid potentially awkward silences. While “safe supplies” occupy time and space with tangible or intangible aids and help to avoid silences, “auxiliary artifacts” govern one’s hands and eyes and allow a communicator to control their self-investment. Avoiding awkward silences is just one of their functions, as I will explain below. “Social facilitators” (Riggins, Citation1990, p. 351) signify material things which give different dynamics to an interaction. For instance, a deck of cards can create partners and opponents, but when played alone the cards would not be a “social facilitator.” Social facilitators, therefore, overlap with the concept of auxiliary artifacts in the way that both sustain interactions, but the particular function of auxiliary artifacts is to support and regulate one’s level of self-investment in the interaction.

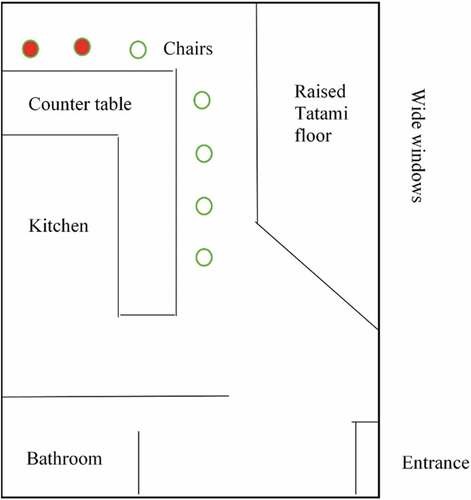

Hostess clubs in Ginza, Tokyo (deluxe bars where predominantly male customers drink alcohol and enjoy conversing with female hostess companions) make the most of auxiliary artifacts. Club Mizuno, where I worked as a hostess (fieldwork 15/01/2018 – 20/04/2018), is located in a large building famous for hostess clubs, but it is a relatively small club compared to others in Ginza (). It has only one rectangular main room and two semi-private spaces at the back. The club itself can accommodate a maximum of 50 people in total. The lighting is subdued with three Galle chandeliers hanging from the ceiling. Jazz music plays continuously at a low volume ().

Several items are placed on the table, including bottles of water, paper napkins, small ashtrays, a matchbox, larger glasses for customers, smaller glasses for hostesses, and small snacks (). For both hostesses and customers, these items allow them to look away and occupy their hands, which in turn allows them to control their level of self-investment. The most typical nagara activity for a hostess is making a drink while listening to her customer. The more experienced the hostess, the less she gives the impression of multitasking.

Sometimes auxiliary artifacts provide a safe haven for nagara listeners. One day, a regular customer, a man in his 70s, brings two male guests, and they sit with me and three other hostesses at a table. After about half an hour or so of talking as a group, we begin to talk in pairs. While I am conversing about traveling abroad with the customer facing, the young hostess sitting in front of me and next to the customer I am talking with starts wiping the waterdrops off everyone’s glasses with paper napkinsFootnote1 and puts the used ashtrays on the edge of the table (where the male concierges can collect them). She is either reluctant to join a conversation or has failed to join one, but as she is not allowed to leave the table, she needs to avoid appearing awkward (14/03/2018). Thus, she used glasses and paper napkins as “safe supplies” and auxiliary artifacts, occupying her hands and eyes as if she is hearing the conversation, but is too busy to listen to the customer.

In another case, I observed visitors at a volunteer listening open-café, a place where anyone (mainly local elderly people) can come and enjoy conversations with listening volunteersFootnote2 and other visitors over green tea and small sweets. One Friday around three o’clock, two male visitors in their early 90s sit at a counter table next to each other, looking at the cups of green tea that they are holding in their hands, while others in the room were having conversations (16/03/2018) (, two red seats). Being occupied with the cups as auxiliary artifacts appeared to allow them to be silent while still engaging in their interaction. Their behavior with the cups created their own space in which to embrace silence rather than acting as a means of avoiding awkward gaps in conversation.

Thus we have seen how auxiliary artifacts can help nagara listeners to regulate their level of self-investment, provide a safe haven, and even create a silent space.

The mechanism of nagara listening

If nagara listening allows regulation and control of self-investment by means of actions and gestures, what then determines the various types and degree of nagara listening? There are many elements to be considered: the purpose of a situation, the physical environment, the time/timing, the status and roles of people in a situation, their gender, emotions, language use, and the dynamics of their relationships. In this paper, I investigate the purpose, the physical environment and the social status and roles of the individuals involved, because these clearly show their effect on nagara listening behavior during my observations.

The purpose and physical environment

The purpose of interaction and the physical environment govern the level of formality of situations, which in turn influences the types and degree of nagara listening.

A funeral provides an example of a formal situation where people need to be serious and grieve. In the Japanese comedy film, “Osōshiki” [The funeral] (Itami, Citation1984), ten or so people gather in a home for a funeral (1:14:51–1:17:37). When the monk sits facing the Buddhist altar and starts reading a sutra, they sit Japanese-style on the floor behind him, close their eyes, join their hands in prayer, and listen to the sutra. One of them starts crying, and she covers her mouth with a white handkerchief. Two children become noisy and start fighting, so some of the adults try to stop them. Five of the adults start to experience pins and needles in their feet, so they try to move their feet or slightly change the way they are sitting. Suddenly a phone rings, so one of them jumps up to take the call, but he stumbles because of his numbed feet. The others try to stifle their laughter.

In this case, listening to the sutra with eyes closed and hands together is the main and dominant involvement. Shifting one’s sitting position and flexing one’s feet can be defined as side and subordinate involvements. Crying can also be a side and subordinate involvement as well as a main involvement because it is considered part of mourning. Children squabbling, however, is not considered an appropriate side activity, hence the adults put a stop to it. People try to stifle their laughter, as they recognize that this too is not an appropriate activity. In this situation, people likely recognize the formality of the occasion in advance with its corresponding degrees and types of involvement.

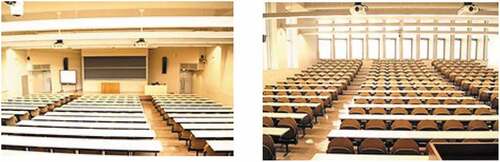

In addition to the purpose, the physical environment also determines the degree of formality and therefore influences nagara listening. For instance, one of the two large rooms on the Shōnan Fujisawa Campus of Keio University is a rectangular-shaped lecture room with a maximum audience of 285 (see in a later paragraph). The lecturer usually stands on a stage at the front of the room, speaks with a microphone, and uses a screen to show slides. The rooms are usually brightly lit, apart from when the lights are turned off to show videos. Lectures are attended by at least 50 students in different academic years. Five of the six lecturers whom I observed allowed the students to eat and drink during their lectures.

I noticed a wide range of side and subordinate behavior. Students sitting in the front rows of the large lecture rooms wrote lecture notes or looked at the screen and at handouts, which can both be categorized as main or dominant involvements in addition to listening. I observed a wider variety of behaviors in the middle and back rows, including various activities on smartphones and laptops such as sending messages, watching YouTube, Facebook and other websites, playing games, preparing presentations, and writing essays. They also studied foreign languages, read textbooks unrelated to the subject of the lecture, and slept. Students sitting in the back rows or on the far left and right-hand sides whispered or ate snacks (both side and subordinate involvements) while students in afternoon lectures sometimes took a nap.

By contrast, in smaller seminar rooms (See ), involvements were more limited. While listening to a lecturer, the students showed main involvements such as writing lecture notes, laughing at what the lecturer said, checking a dictionary, looking at a textbook, and turning a page of a book. Their side involvements were mostly limited to scratching their arm, touching their lip or neck with their finger, or stroking their hair. They appeared to need to show more self-investment than students in a larger room.

Therefore, although having the same purpose – listening to a lecture and learning – the physical environments changed the type of acceptable nagara listening. Students in a large lecture room were often involved in a wide range of side and subordinate involvements, while those in a smaller seminar were focused on their main involvements and were engaged in only limited side involvements. In these situations, as the physical distance between speakers and listeners increases, so does the extent of side or subordinate involvements permitted to students.

The status and role of participants

Social status and role can also influence how people judge the acceptability of nagara listening in a given situation. The following two examples reveal cases where nagara listeners are evaluated differently due to their social status, despite being involved in similar nagara listening.

Matsushima Midori, a 60-year-old female Japanese politician, was severely criticized in the media after her listening behavior at a committee meeting of the Japanese parliament was broadcast on TV (Unknown, Citation2016, Accessed 19/03/ 2016). While sitting next to a young male politician, who was standing and explaining to the committee an issue of diplomacy, she sits somewhat slumped in her seat with her left elbow on the table and pats her hair with her left hand. She looks at someone in front of her, and then with her left elbow on the table touches her lips. She touches a book she brings on the table with her right hand and looks in front of her again. She straightens her back, rubs her left eye, folds her arms across her chest, and yawns. Matsushima then holds her mobile phone and looks at it with her back hunched. She yawns again and starts reading the book that is lying on the table, then picks it up in both hands to continue reading while leaning against the back of her chair. She touches the frame of her glasses and her lips with her left hand and holds the book in her right hand.

In this case, merely attending the committee was judged to be an insufficient display of involvement in the main activity, and her side and subordinate involvements of checking her phone and reading a book were considered to have superseded the main and dominant involvement of listening to the speaker. As a result, observers of her behavior concluded that she was not listening at all. From the video, it is not clear whether or not she was keeping “one ear open” to hear the talk, but it is evident from the criticism leveled at her that what was required as a politician was to demonstrate that she was listening rather than simply hearing.

Similar behavior to Matsushima’s in other situations is not always criticized as “not listening.” During an afternoon lecture at Keio University, I observed about 50 students in a large rectangular lecture room (). A male student wearing a sports club uniform sits slightly behind the middle row and places his large black bag on the left-hand side of the desk. While a female lecturer talks about child development, he opens his laptop in front of him, opens a textbook which is not related to the lecture in front of his laptop, and reads it while chewing gum. He sometimes uses his smartphone in front of his open laptop but does not turn his face to look at the lecturer. Then he folds his arms on the desk, places his head on them, and begins to sleep.

In this example, the student tries to hide his side and subordinate involvements behind his open laptop to maintain the appearance of attending to the main and dominant involvement, namely, listening to the lecture. Sleeping would appear to threaten this as it precludes paying any attention to the lecture. However, dozing in a lecture is often permitted as a side or subordinate involvement in Japan, because expressing deference by attending the lecture is more important than understanding the content (Steger, 2003). Despite his side and subordinate involvements, the student was not criticized by the lecturer and was probably judged to have demonstrated sufficient engagement with the lecture by just attending. Thus, although Matsushima and this student were involved in similar nagara listening, only the former’s listening was criticized. In these cases, the status and role of the individual changed the acceptability of the degree and type of nagara listening. The different formality of the two situations may also have contributed to the differences in acceptable nagara listening. A comparison of similar nagara listening in similar settings with people of different social status would be an interesting subject for further research.

“Dozing nagara listening” is exhibited in various Japanese contexts. It is common for politicians to sleep during parliamentary sessions in Japan where they should be listeners. Brigitte Steger (2003) observes that sleeping in the workplace in Japan is often viewed as the result of hard work and of having sacrificed nighttime sleep due to work responsibilities. Mizutani Osamu, a male commentator in a TV show called Bibit, also comments that in the case of Matsushima Midori, sleeping would have been acceptable, but not reading or using a mobile phone (Unknown, Citation2016, Accessed 14/08/ 2016). This is despite the fact that, unlike sleeping, they do not preclude the possibility of hearing and remaining aware of the main and dominant activity.

Another interesting example of social status is provided by Okuda Aki, a university student and a representative of a youth political group, who politely requested the MPs before whom he was about to speak in a public hearing in the Japanese parliament to refrain from sleeping. His implication was that they were likely to do this due to his youth and humble status as a student or because they held the discussion to be of little importance (2020 summer, Citation2015, Accessed 10/09/2020). If it is true that the acceptability of side and subordinate involvements increases along with the relative status of the listener, why, then, was it not acceptable for Matsushima Midori, as a relatively high-ranking politician, to check her phone and read a book while listening to someone of lower status than herself?

Two more aspects should be noted in the criticism aimed toward her. First, a gender aspect: she may have been singled out for criticism due to being a woman who did not listen to a male politician. This aspect requires further research. Secondly, she was reading something unrelated to the ongoing topic; this required a certain level of focus that would impede listening and pull a listener’s eyes from the speaker, which could indicate indifference toward the speaker. As a fundamental conversational rule, a listener is supposed to gaze at a speaker when the speaker looks at the listener (Goodwin, Citation1984, p. 230). In Matsushima’s case, she was sitting next to the speaker rather than in front of him, so the speaker never looked directly at her. Thus she was not criticized for failing to return eye contact but for failing to exhibit a level of focus appropriate to her role.

In these examples, we have seen how the status and role of an individual, in addition to cultural codes, can limit or expand the acceptable types and degree of nagara listening, and how the combination of different elements generates different tacit rules for listeners.

Conclusion

This paper has analyzed nagara listening, whereby a listener engages in several other actions and gestures while listening. Some of these actions and gestures relate to the ongoing conversation, but others do not. Both types of actions and gestures are used, often in combination with “auxiliary artifacts,” to help the conversation run smoothly, although this may not be achieved if the listener fails to pay adequate attention to the conversation. Previous research has captured this multitasking aspect of listeners, but has failed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon, despite it being an important part of listeners’ behavior.

The acceptable types and degree of nagara listening can differ from society to society. Tolerance of “dozing nagara listening” and criticism of “reading nagara listening” are specific to Japanese cultural contexts. Nagara listeners embody these tacit rules (Goffman, Citation1990) and the “habitus of listening” (Becker, Citation2010) to perform as listeners. Further work needs to be carried out to explore how gender and emotional aspects affect nagara listening or what makes a good nagara listener. Nagara listening can serve as a perspective for understanding not only listening, but also society and culture through the lens of listeners.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dr Brigitte Steger, Dr Falk Parra, Julian Sedgwick, Heather Phoon and two anonymous reviewers for giving of their time on many occasions to advise me on this research.

Funding

This work was supported by The Honjō International Scholarship Foundation; The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation [5124]; The Aoi Foundation; The Japan Foundation Endowment Committee; The Japan Anthropology Workshop; and The International SoroptimistKunitachi Japan.

Notes

1 Hostesses wipe the waterdrops off glasses to avoid customers getting their hands wet. It is to demonstrate that hostesses care about even trifling matters for customers, and also to determine how much alcohol remains in a glass as hostesses need to keep pouring drinks until customers decide to leave.

2 Keichō borantia (active listening volunteers). Usually in their 60s and 70s, these volunteers learn active listening skills, which originally derive from client-centered therapy established by Carl Ransom Rogers in the US in 1942. They offer their services mainly (but not exclusively) to elderly people by visiting individual houses and nursing homes, or by running an open-café in a local area. Many local councils’ social welfare departments and established non-governmental organizations hold training courses every year and those who participate often establish their own groups. Large cities may have several local groups.

References

- Setoguchi K., & Takanari M. (2008) Around 40: Chūmon no ōi onnatachi. [Around 40: Women with many demands.] [TV series]. TBS; TBS.

- Bavelas, J., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.941

- Becker, J. (2010). Exploring the habitus of listening: Anthropological perspectives. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Series in affective science. Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications (pp. 128–157). Oxford University Press.

- Brunner, L. J. (1979). Smiles can be back channels. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(5), 728–734. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.5.728

- Cavan, S. (1966). Liquor license: An ethnography of bar behavior. Al-dine Publishing Co.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2012). Exploring affiliation in the reception of conversational complaint stories. In A. Peräkylä & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in interaction (pp. 113–146). Oxford University Press.

- Fox, K. (2005). Watching the English: The hidden rules of English behaviour. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Goffman, E. (1966). Behavior in public places. The Free Press.

- Goffman, E. (1990). The presentation of self in everyday life. Pelican Books.

- Goodwin, C. (1984). Notes on story structure and the organization of participation. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 225–246). Cambridge University Press.

- Goodwin, C. (2009). Embodied hearers and speakers constructing talk and action in interaction. Cognitive Studies, 16(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.11225/jcss.16.51

- Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., & Nevile, M. (2014). Multiactivity in social interaction: Beyond multitasking. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Hall, E. T. (1983). The dance of life: The other dimension of time. Anchor Press/Doubleday.

- Heath, C. (1986). Body movement and speech in medical interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Heath, C., Von Lehn, D., Cleverly, J., & Luff, P. (2012). Revealing surprise: The local ecology and the transportation of action. In A. Peräkylä & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in interaction (pp. 212–234). Oxford University Press.

- Hilde A. M. V., & V. Viswanathan (2015). An observational study on how situational factors influence media multitasking with TV: The role of genres, dayparts, and social viewing. Media Psychology, 18(4),499–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.872038

- Holt, E. (1993). The structure of death announcements: Looking on the bright side of death. Text, 13(2),189–212. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/5512

- Imaishi, S. (1993). Kikite no kōdō: Aizuchi no kitei jōken [Behavior of listeners: A model of aizuchi for analysis]. Bulletin of Osaka University Japanese Language Studies, 5, 95–109. http://hdl.handle.net/11094/5420

- Imhof, M. (1998). What makes a good listener? Listening behavior in instructional settings. International Journal of Listening, 12(1), 81–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.1998.10499020

- Kaukomaa, T., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2015). How listeners use facial expression to shift the emotional stance of the speaker’s utterance. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 48(3), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2015.1058607

- Kita, S., & Ide, S. (2007). Nodding, aizuchi, and final particles in Japanese conversation: How conversation reflects the ideology of communication and social relationships. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(7), 1242–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.02.009

- Kraut, R. E., Lewis, S. H., & Swezey, L. W. (1982). Listener responsiveness and the coordination of conversation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(4), 718–731. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.4.718

- Kushida, S. (2009). Kikite ni yoru katari no shinkō sokushin [Recipient’s methods for facilitating progress of telling: Sustaining, prompting, and promoting continuation]. Cognitive Studies, 16(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.11225/jcss.16.12

- Kushniryk, A., & Levine, K. J. (2012). Impact of Multitasking on Listening Effectiveness in the Learning Environment. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 3(2). http://org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2012.2.7

- Mark, G., Shamsi T. Iqbal, M. Czerwinski, & P. Johns. (2015). Focused, aroused, but so distractible: Temporal perspectives on multitasking and communications. Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 903–916. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675221

- Unknown (2016). Matsushima Midori at a committee meeting of the Japanese parliament [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TPk65caGkB8

- Maynard, D., & Freese, J. (2012). Good news, bad news, and affect: Practical and temporal “emotion work” in everyday life. In A. Peräkylä & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in interaction (pp. 92–112). Oxford University Press.

- 2020 summer (2015, September 15).9/15 Okuda Aki SEALDs Kōchōkai [September 15 Okuda Aki SEALDs a public hearing][Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5dsMhkj6eHk

- Itami J. (1984). Osōshiki [The funeral][Film] New Century Producers & Itami production.-

- Stevenson, A. (2010). Task In Oxford Dictionary of English 3rdedition. Oxford University Press,

- Riggins, S. H. (1990). The power of things: The role of domestic objects in the presentation of self. In S. H. Riggins (Ed.), Beyond Goffman: Studies on communication, institution, and social interaction (pp. 341–368). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Sartre, J. (1943). L’être et le néant: Essai d’ontologie phénoménologique. Gallimard.

- Sartre, J. (1957). Being and nothingness: An essay on phenomenological ontology. Methuen & Co.

- Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Steger, B. (2013). Negotiating gendered space on Japanese commuter trains. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 13, 3. https://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol13/iss3/steger.html

- Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701691123

- Sugiyama, L. T. (1976). Japanese patterns of behaviour. University Press of Hawaii.

- Szatrowski, P. (2000). Relation between gaze, head nodding and aizuti ‘back channel’ at a Japanese company meeting. Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: General Session and Parasession on Aspect, 26(1),283–294. https://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v26i1.1154

- Unknown (2016) Bibit[Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WrSNNfHEIPg

- Ueno, K. (2011). Kikite kōdō no shakaigengo-teki kōsatsu: Katari ni taisuru kikite no hatarakikake [A sociolinguistic analysis of listening practices in Japanese conversation]. Memoirs of the Japan Women’s University, Faculty of Literature, (61), 57–68. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/235231975.pdf

- Wilkinson, S., & Kitzinger, C. (2006). Surprise as an interactional achievement: Reaction tokens in conversation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(2), 150–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250606900203