ABSTRACT

The impact of food on physical and mental co-complications of ulcerative colitis (UC) has not been clearly defined. The current study aimed to evaluate the effects of a dietary modification program (DMP) on fatigue, mental health, quality of life, fasting blood glucose, and lipid profile of UC patients during the remission phase. To conduct this parallel, randomized controlled trial study, 80 UC patients were recruited and allocated randomly to an intervention or a control group. Participants were provided dietary guidelines in the form of an educational booklet and a dedicated diet that was recommended for use for 12 weeks. The DMP consisted of recommendations that participants eat often and little (4–6 times per day), consume foods at a balanced temperature, decrease consumption of spicy foods, decrease excess intake of fat, decrease simple carbohydrates and drink adequate fluids. Moreover, increase good-quality protein and eliminate dairy products in the presence of lactose intolerance. Furthermore, it included avoidance of margarine, limiting alcohol, caffeine, and commercially prepared foods such as fast foods, ready meals, and canned foods. Baseline and post-intervention measurements of primary and secondary outcomes were recorded for final analysis. Overall, 76 patients completed the study. The participants in the DMP group consumed higher amounts of protein, zinc, vitamin C, and D and lower amounts of dietary energy, carbohydrate, saturated fat, sodium, and lactose compared to the control group (all P values <.05). Recommendations to follow the DMP resulted in a significant improvement of fatigue and mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress) in the intervention group compared with usual recommendations and a significant increase in some aspects of quality of life, including bodily pain and general health (all P values <.05). No significant changes were found in fasting blood glucose and lipid profile (all P values >.05). The study suggests that there is likely to be a link between the provided dietary advice with physical and mental improvements. The effect of diet does not arise through the elimination or the addition of specific nutrients; rather, each food syndicate many nutrients that let for a synergistic or an antagonistic action when present in a certain composition.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing-remitting immune-related disease of undetermined etiology with devastating symptoms, which impair the performance, mental health, and quality of life.[Citation1,Citation2] Abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, and fecal urgency are among common symptoms associated with this chronic inflammatory disorder mainly affecting the large intestine. There is still a lack of understanding of the condition, and immune-mediated processes have been revealed to be imperative, with evidence from efficient therapies such as corticosteroid, 5-aminosalicylate derivatives, immune-modulating drugs (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine), and biologic agents .[Citation3]

Regardless of these therapeutic agents, clinicians and patients frequently refer to complementary therapies, primarily because of the side effects associated with current therapeutic approaches .[Citation4] Moreover, patients have stated that consumption of some dietary items tends to worsen their symptoms. As a result, they frequently intend to adjust their intake based on this belief. Ballegaard et al. documented that 64% of individuals with UC report intolerance to one or more food items compared with 14% of controls .[Citation5] This indicates a possibly broad role for diet in diminishing the symptoms of UC and also in the treatment of flare-ups.

In the past four decades, extensive research has been dedicated to discovering how diet accounts for the pathology of inflammatory bowel disease. Based upon previous investigations, it has been identified that dietary factors such as high intake of simple carbohydrate, [Citation6] fast food, [Citation7] margarine, [Citation8] processed and red meat, [Citation9] fat, [Citation10] polyunsaturated fatty acids, [Citation6] omega-6 fatty acids, [Citation11] cola drinks and chocolate, [Citation6] Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols (FODMAPs)[Citation12] and a low intake of probiotic yogurt[Citation13] and fish[Citation14] increased the risk of UC.

These findings are expanding the hypothesis generated at first by Burkitt[Citation15] that alterations in the diet can be the most important modulators in UC expression. Therefore, all these dietary factors should be addressed in comprehensive dietary advice provided to patients with UC. The current study aimed to evaluate the effects of a dietary modification program (DMP) on fatigue, mental health, quality of life, fasting blood glucose (FBG), and lipid profile of UC patients during the remission phase.

Materials and methods

Design

This was a parallel-group, single-blind randomized controlled trial comparing a DMP with usual care in UC patients during the remission phase.

Participants

From January to April 2020, we consecutively evaluated patients with a suspect of UC in the IBD center, Salamat clinic, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. Our IBD clinic or other general medicine or gastroenterology clinics located in Isfahan city were used for the recruitment of eligible patients. Individuals (18–80 years old) with a confirmed diagnosis of UC by a gastroenterologist who gave their informed consent entered this study. Subjects were excluded if they had any changes in the dosage of oral 5-aminosalicylic acid in the preceding 4 weeks, used antibiotics, probiotics, or prebiotics, or were on any special diet in the preceding 8 weeks, had significant comorbidities, and/or were pregnant or lactating.

The study protocol complied with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Following approval of the research ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1397.065), the study was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (registration number; IRCT20150304021342N2). Besides, the study was planned based on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement guidelines .[Citation16]

Sample size

Based on equations used in similar studies, [Citation17] considering type 1 and 2 errors of 5% (α = 0.05) and 20% (β = 0.2; power = 80%), and a possible loss, a sample size of 40 patients in each group was determined.

Trial procedures

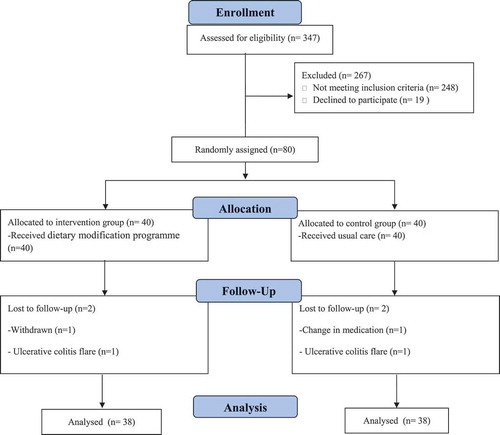

Of the 347 patients who were referred to the IBD center, participants fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to participate in the dietary modification program (n = 40) or receive usual care (n = 40). A blocked randomization method with randomly permuted blocks sizes 4 was used to assign each patient to an intervention or control group, to guarantee recruitment balance between the 2 groups and avoid possible risk for selection bias. Treatment assignments were buried in numbered closed envelopes, which were opened sequentially upon patient admission. The gastroenterologist (B.T) was blinded to the treatment assignment.

Intervention group and description of DMP

Patients who were assigned to the intervention group (n = 40) participated in a 3-months dietitian-led DMP. Participants were provided dietary guidelines in the form of an educational booklet and a dedicated diet. The dietary guidelines of DMP primarily focused on the reduction of UC symptoms and nutritional deficiency risks and also co-complications of patients including mood disorders, fatigue, and diminished quality of life. The provided guidelines endeavored to consolidate the existing documents as well as existing guidelines on diet and UC .[Citation2,Citation9,Citation18–Citation21]

The DMP consisted of recommendations that participants eat often and little (4–6 times per day), consume foods at a balanced temperature, decrease consumption of spicy foods, decrease excess intake of fat, decrease simple carbohydrates and drink adequate fluids. Moreover, increase good-quality protein and eliminate dairy products in the presence of lactose intolerance. Furthermore, it included avoidance of margarine, limiting alcohol, caffeine, and commercially prepared foods, including fast foods, ready meals, and canned foods.

In summary, DMP includes (i) low fat (especially emphasizing the need to avoid saturated and trans-fats and substituting them with polyunsaturated fats), (ii) low carbohydrate (especially emphasizing the need to avoid refined simple carbohydrate and surplus of some FODMAPs (Beet, asparagus, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, fennel, garlic, onion, mushrooms, leeks, apples, avocado, apricot, cherry, mango, peach, plums, pear, persimmons, watermelon, pistachios, almonds, dried fruits, fruit juice), (iii) high protein (without any processed or red meat), and (iv) probiotics consumed as food. To determine adherence, participants were contacted weekly and food records were also collected.

Control group

Patients in the control group (n = 40) underwent the usual care at the IBD center. Routine dietary advice (UDA) included general oral and written information about healthy food choices based on the Healthy Eating Plate[Citation22] with 50–60% carbohydrates, 15–20% protein, and 30% total fat. This composition was more parallel to the Iranian dietary pattern .[Citation23]

Outcome measures

Measurement of fatigue, quality of life, and mental health (primary outcomes), as the main co-complications in UC, is crucial when examining the treatment efficacy. Furthermore, FBG and lipid profile were selected as secondary outcomes. Outcomes were examined both at baseline and at the end of the study.

Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) is a symptom-based disease activity index that uses six clinical domains, including daytime and nocturnal bowel frequency, urgency, amount of blood in the stool, wellbeing, and extra-intestinal manifestations .[Citation24] In this study, remission was defined as SCCAI of less than 2.5 .[Citation25] The 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF-36) is a validated common instrument for examining the health-related quality of life .[Citation26] Eight scales included in this questionnaire are physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RE), and mental health (MH). Each scale ranges from 0–100 scores with lower scores indicating more disability .[Citation27] Mental health was determined by the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS- 21) questionnaire, which had previously been validated in the Iranian population .[Citation28] Each question of DASS-21 has four scales from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time) to determine the symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression. The sum of scores for each domain should be multiplied to 2 to evaluate the original 42-item DASS .[Citation29] The fatigue severity scale (FSS) was used to assess patients’ fatigue status. This scale contained nine brief items; each of them graded from 1 (strong disagreement) to 7 (strong agreement) and previously had validated in the Iranian population .[Citation30,Citation31]

The dietary intakes of participants were assessed using a food record questionnaire at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks during the intervention, and data was analyzed by nutritionist 4 software (First Databank, Hearst Corp, San Bruno, CA, USA). Bodyweight was measured using the Omron BF-511 digital scale (OMRON, Japan) to the nearest 0.1 kg after fasting at night, without shoes, and with minimal clothing. Using a SECA stadiometer (Hamburg, Germany), height was measured with 0.1 cm accuracy. Finally, BMI was computed as weight/(height)2.

Fasting Blood samples (10 ml) were centrifuged (Avanti J-25, Beckman, Brea, CA, USA) at 3500 rpm for 10 min to separate serum immediately after collection and were then maintained at −70°C for further analyses. We used commercial kits (Pars Azmoon Company, Tehran, Iran) to measure plasma lipids (i.e., total cholesterol [TC], triglycerides [TG], low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol) and FBG. The intra- and inter-assay coefficient variances (CVs) for lipid profile and FBG measurements were <10%. Measurements of lipids and FBG were performed in a blinded fashion in duplicate, in pairs (before and after the intervention) at the same time, in the same analytic run, and in random order to reduce systematic error and inter-assay variability. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) was assessed using the immunoturbidimetric method by Archem Diagnostics kit (Turkey), with inter- and intra-assay CVs lower than 20%.

A stool sample was taken from the patients at the beginning of the study. The fecal calprotectin was analyzed by the ELISA method (HK325; Hycult Biotech kit, Uden, Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical data were presented as mean±standard error (SE) and percentage, respectively. Kolmogrove-smirnov statistical test was used to evaluate normality, and non-normality distributed data were subjected to natural logarithmic transformation. Within and between groups comparison in terms of quantitative data were conducted using paired samples t-test and analysis of covariance (adjustment was made for potential confounding factors) while for categorical data generalized Mc-Nemar test and chi-square tests. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided P-value of less than 5% was taken as statistically significant.

Result

Among the 80 UC patients who enrolled in the current trial, 4 patients withdraw due to personal reasons (n = 1), change in medication (n = 1), and UC flare (n = 2) (). Finally, analyses were done on 76 patients (38 in the DMP group and 38 in the UDA group). As illustrates, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, gender, smoking, weight, BMI, SCCAI, fecal calprotectin, CRP, and number of Mesalazine used by each patient (all P values >.05) while marital status, time since UC diagnosis, and UC extent were significantly different (all P values <.05) between the two groups.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of UC patients who received either dietary modification program in addition to usual care or just usual care.

shows the dietary intake of participants throughout the study. The participants in the DMP group consumed higher amounts of protein, zinc, vitamin C and D and lower amounts of dietary energy, carbohydrate, saturated fat, sodium, and lactose compared to the control group (all P values <.05). All these data indicate relatively good compliance of the patients’ DMP.

Table 2. Dietary intakes of the participants throughout the study.

The effects of DMP on mental health, fatigue, and quality of life are summarized in . Recommendations to follow the DMP resulted in a significant improvement of fatigue and mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress) in the intervention group compared with usual recommendations (all P values <.05). The following 12-months of DMP resulted in a significant increase in some scales of SF-36, including BP and GH (all P values <.05) and marginally for VT (P < .06). Furthermore, the RP score in the intervention group decreased less relative to the control group (P < .05). The results of the between-group analysis show that adherence to DMP could not improve the metabolic profile of the intervention group, including FBG, TG, TC, HDL, and LDL compared to the control group (all P values >.05) ().

Table 3. Mental health, fatigue, and quality of life at the baseline and following 12-wk intervention in UC patients who received either dietary modification program in addition to usual care or just usual care.

Table 4. Metabolic profile at the baseline and following 12-wk intervention in UC patients who received either dietary modification program in addition to usual care or just usual care.

Discussion

In this study, a topic was addressed on which few or no previous studies have been conducted. We intended to inquire about the effects of comprehensive dietary advice on physical and mental co-complications of patients with UC during the remission phase. This single-blind randomized controlled trial suggests that 3-months of DMP can influence mental health, fatigue, and some subsets of quality of life and may therefore provide potential therapeutic benefits.

The current document suggests that a link is likely between the provided dietary advice and quality of life. This was concluded by improvements in BP and also GH of the SF-36 questionnaire. In agreement with this finding, Kyaw et al.[Citation2] proposed a significant improvement in UC patients’ quality of life following comprehensive dietary advice. Furthermore, dietary advice has been proved to be helpful among other populations, [Citation33,Citation34] especially on physical components of quality of life, which is consistent with our findings.

An improvement in mental health and fatigue in the intervention group, as opposed to the controls, also suggests a beneficial role for diet in terms of physical and mental health among UC patients. Despite the lack of any study investigating the effects of comprehensive dietary advice on mood status and fatigue in UC patients, Leedo et al.[Citation35] reported that healthy meals could improve these parameters among healthcare staff.

The current study is original in using a comprehensive dietary approach in patients with UC. The effect of diet does not arise through the elimination or the addition of specific nutrients; rather, each food syndicate many nutrients that let for a synergistic or an antagonistic action when present in a certain composition. Accepting the heterogeneous nature of dietary intake and bearing in mind the dietary pattern rather than a single nutrient or food group, is an imperative step toward improving our understanding of the association between UC and diet .[Citation2,Citation36] Besides, epidemiological and migrant studies have indicated the urgent need for a comprehensive dietary approach in UC, [Citation37–Citation41] confirming that a switch in the environment from one place to another and from one food culture to another also changes the incidence of UC; so, a fault is presented when environmental and cultural confounders are reduced to a single nutrient or food group. The dietary guidelines (DMP) provided for this study represent a comprehensive approach addressing the adjustment of typical dietary factors in a western diet. The macronutrient composition (low fat and carbohydrate, high protein) was selected based on the following evidence:

It has been reported that a high-fat diet could increase gut permeability, alter the gut microbiota, and also influence the inflammatory response[Citation42,Citation43] which is in agreement with existing guidelines[Citation19] and previous studies .[Citation37,Citation44,Citation45] The low-carbohydrate diet recommendation is based on previous reports that the large intestine microbiome responds to both the quantity and the type of dietary carbohydrate .[Citation32] This recommendation is consistent with previous documents[Citation2,Citation37] that the improper consumption of simple carbohydrates may increase gut permeability, compromise the fermentation process, and alter mucosal immune systems. Reduced protein absorption is accompanying by bowel resection, diarrhea, active disease, and medication, specifically for the treatment of UC (e.g. corticosteroids, sulphasalazine, and immunosuppressants). Furthermore, increased protein intake is crucial to facilitate the repair of the inflamed colon .[Citation2,Citation46]

Although the participants met the criteria for the UC, they were not on the upper end of abnormal cut-points for FBG, TC, TG, HDL, and LDL, which might reduce the chance of achieving significant changes in these features following the intervention. In the present study, compared with UDA for UC patients, recommendations to follow the DMP resulted in significant reductions in dietary energy density and intakes of carbohydrates, saturated fats, lactose, and Na along with increased intakes of proteins, Zn, vitamin D, and C. It is mostly unrecognized how these dietary changes might influence health in UC patients and still a matter for research. Several possibilities have been suggested: high serum sodium: potassium ratio has led to progesterone secretion, which may change the neural activity of the brain possibly leading to mood deterioration .[Citation47] It is speculated that, through interplay with noradrenergic, serotonergic, and dopaminergic systems, and also by blocking N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, vitamin C might exert improvements in mood .[Citation48] Zn could be involved in the serotonergic and glutamatergic system, as well as neurotrophic factors (BDNF) and antioxidant mechanisms that may have resulted in mood regulation. Zn administration could increase the density of serotonin receptors in the hippocampus and the frontal cortex, as well as, NMDA receptors blockage, which is the key mechanism of antidepressant drugs .[Citation47,Citation49] Moreover, vitamin D regulates the production of dopamine, adrenalin, and noradrenaline through vitamin D receptors and prevents the depletion of dopamine and serotonin centrally .[Citation50,Citation51] Given the role of vitamin C in carnitine biosynthesis, an essential cofactor in long-chain fatty acid’s transportation into the mitochondria, it plays a crucial role in energy production through beta-oxidation, and insufficient vitamin C supply can be responsible for weakness, fatigue, or muscle aching .[Citation52]

Limitations of the study are as follows: food records used to assess participants’ dietary compliance are not ideal for this purpose. Finding a suitable biomarker for adherence to dietary patterns, in particular, to the DMP, can be considered in future studies. Moreover, as the Iranian food composition database was not complete, we had to use the USDA food composition database, which includes some enriched foods and might overestimate iron, dietary fiber, and vitamin C contents for Iranian foods.

Conclusion

In conclusion, recommendations to follow the DMP for 12 weeks among UC patients during the remission phase, compared with UDA, improved mental health, fatigue, and some subsets of quality of life. No significant changes were found in FBG and lipid profiles. The findings of this study may offer a new perspective for potential intervention by practical dietary modifications in UC, and as such, are eagerly awaited by the patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors are warmly thankful to the participants, the IBD center, Salamat clinic, and all the personnel for their support. The authors declare no conflict of interest. A. A and B. T contributed to conception, design, statistical analysis, and manuscript drafting. A. A contributed to the data collection. A. A and B. T contributed to the manuscript drafting.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Goodhand, J.; Wahed, M.; Mawdsley, J.; Farmer, A.; Aziz, Q.; Rampton, D. Mood Disorders in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Relation to Diagnosis, Disease Activity, Perceived Stress, and Other Factors. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. 2012, 18(12), 2301–2309.

- Kyaw, M. H.; Moshkovska, T.; Mayberry, J. A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, Exploratory Study of Comprehensive Dietary Advice in Ulcerative Colitis: Impact on Disease Activity and Quality of Life. Eur. J. Gastroenteol. Hepatol. 2014, 26(8), 910–917.

- Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus Jr EV, Danese S, Colombel JF, Törüner M, Jonaitis L, Abhyankar B, Chen J, Rogers R, Lirio RA. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019 Sep 26;381(13):1215Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus Jr EV, Danese S, Colombel JF, Törüner M, Jonaitis L, Abhyankar B, Chen J, Rogers R, Lirio RA. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019 Sep 26;381(13):1215-1226.

- Greenlee H, DuPont‐Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG, Carlson LE, Cohen MR, Deng G, Johnson JA, Mumber M, Seely D, Zick SM, Boyce LM. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence‐based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017 May 6;67(3):194–232.

- Ballegaard, M.; Bjergstrøm, A.; Brøndum, S.; Hylander, E.; Jensen, L.; Ladefoged, K. Self-reported Food Intolerance in Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 32(6), 569–571.

- Rizzello F, Spisni E, Giovanardi E, Imbesi V, Salice M, Alvisi P, Valerii MC, Gionchetti P. Implications of the Westernized Diet in the Onset and Progression of IBD. Nutrients. 2019 May; 11(5):1033.

- Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Wilson J, Williams J, Hair C, Knight R, Prewett E, Dabkowski P, Alexander S, Allen B, Dowling D. Influence of food and lifestyle on the risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease. Internal Med. J. 2016 Jun; 46(6):669-776.

- Maconi, G.; Ardizzone, S.; Cucino, C.; Bezzio, C.; Russo, A. G.; Porro, G. B. Pre-illness Changes in Dietary Habits and Diet as a Risk Factor for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case-control Study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16(34), 4297.

- Hou, J. K.; Abraham, B.; El-Serag, H. Dietary Intake and Risk of Developing Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106(4), 563–573.

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, Higuchi LM, de Silva P, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Richter JM, Chan AT. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gut. 2014 May 1;63(5):776-784.

- Investigators, I.;. Linoleic Acid, a Dietary N-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid, and the Aetiology of Ulcerative Colitis: A Nested Case–control Study within a European Prospective Cohort Study. Gut. 2009, 58(12), 1606–1611.

- Gearry, R. B.; Irving, P. M.; Barrett, J. S.; Nathan, D. M.; Shepherd, S. J.; Gibson, P. R. Reduction of Dietary Poorly Absorbed Short-chain Carbohydrates (Fodmaps) Improves Abdominal Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—a Pilot Study. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 2009, 3(1), 8–14.

- Ganji‐Arjenaki, M.; Rafieian‐Kopaei, M. Probiotics are a Good Choice in Remission of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Meta Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233(3), 2091–2103.

- Mozaffari H, Daneshzad E, Larijani B, Bellissimo N, Azadbakht L. Dietary intake of fish, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Nutr. 2020 Feb;59(1):1-17. doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-01901-0.

- Burkitt, D.;. Related Disease—related Cause? Lancet. 1969, 294(7632), 1229–1231.

- Bennett, J. A.;. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT): Guidelines for Reporting Randomized Trials. Nurs Res. 2005, 54(2), 128–132.

- Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Farquharson FM, Louis P, Fava F, Franciosi E, Scholz M, Tuohy KM, Lindsay JO, Irving PM, Whelan K. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and a probiotic restores bifidobacterium species: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2017 Oct 1;153(4):936-947.

- Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Pearce MS, Phillips E, Gregory W, Barton JR, Welfare MR. Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2004 Oct 1;53(10):1479–1484.

- Brown, A. C.; Rampertab, S. D.; Mullin, G. E. Existing Dietary Guidelines for Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 5(3), 411–425.

- Forbes A, Escher J, Hébuterne X, Kłęk S, Krznaric Z, Schneider S, Shamir R, Stardelova K, Wierdsma N, Wiskin AE, Bischoff SC. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Nutrition. 2017 Apr 1;36(2):321–347.

- Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, Matsui T, Hirai F, Inoue N, Kato J, Kobayashi K, Kobayashi K, Koganei K, Kunisaki R. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of gastroenterology. 2018 Mar 1;53(3):305–353.

- School, H. M.;. Healthy Eating Plate Dishes Out Sound Diet Advice: More Specific than MyPlate, It Pinpoints the Healthiest Food Choices. Harv. Heart Lett. 2011, 22, 4.

- Azadbakht, L.; Mirmiran, P.; Hosseini, F.; Azizi, F. Diet Quality Status of Most Tehranian Adults Needs Improvement. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 14, 2.

- Jowett, S.; Jowett, S.; Jowett, S.; Jowett, S.; Jowett, S.; Jowett, S. Defining Relapse of Ulcerative Colitis Using a Symptom-based Activity Index. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38(2), 164–171.

- Higgins, P.; Schwartz, M.; Mapili, J.; Krokos, I.; Leung, J.; Zimmermann, E. Patient Defined Dichotomous End Points for Remission and Clinical Improvement in Ulcerative Colitis. Gut. 2005, 54(6), 782–788.

- Montazeri, A.; Goshtasbi, A.; Vahdaninia, M. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Translation and Validation Study of the Iranian Version. 2006.

- Lins, L.; Carvalho, F. M. SF-36 Total Score as a Single Measure of Health-related Quality of Life: Scoping Review. SAGE Open Med. 2016, 4, 2050312116671725.

- Samani, S.; Joukar, B. A Study on the Reliability and Validity of the Short Form of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21). 2007.

- Henry, J. D.; Crawford, J. R. The Short‐form Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS‐21): Construct Validity and Normative Data in a Large Non‐clinical Sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44(2), 227–239.

- Fereshtehnejad, S.-M.; Hadizadeh, H.; Farhadi, F.; Shahidi, G. A.; Delbari, A.; Lökk, J. Reliability and Validity of the Persian Version of the Fatigue Severity Scale in Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Parkinson’s Dis. 2013, 2013.

- Johansson, S.; Kottorp, A.; Lee, K. A.; Gay, C. L.; Lerdal, A. Can the Fatigue Severity Scale 7-item Version Be Used across Different Patient Populations as a Generic Fatigue Measure-a Comparative Study Using a Rasch Model Approach. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2014, 12(1), 24.

- Macfarlane S. Chapter 10 - Prebiotics in the Gastrointestinal Tract. In: Watson RR, Preedy VR, editors. Bioactive Foods in Promoting Health. Boston: Academic Press; 2010, 145–156.

- Swisher AK, Abraham J, Bonner D, Gilleland D, Hobbs G, Kurian S, Yanosik MA, Vona-Davis L. Exercise and dietary advice intervention for survivors of triple-negative breast cancer: effects on body fat, physical function, quality of life, and adipokine profile. Supportive Care Cancer. 2015 Oct 1; 23(10):2995–3003.

- White, C.; Drummond, S.; De Looy, A. Comparing Advice to Decrease Both Dietary Fat and Sucrose, or Dietary Fat Only, on Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance and Perceived Quality of Life. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 61(3), 282–294.

- Leedo, E.; Beck, A. M.; Astrup, A.; Lassen, A. D. The Effectiveness of Healthy Meals at Work on Reaction Time, Mood and Dietary Intake: A Randomised Cross-over Study in Daytime and Shift Workers at an University Hospital. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118(2), 121–129.

- Nourian, M.; Askari, G.; Golshiri, P.; Miraghajani, M.; Shokri, S.; Arab, A. Effect of Lifestyle Modification Education Based on Health Belief Model in Overweight/obese Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Parallel Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2020, 38, 236–241.

- Sakamoto N, Kono S, Wakai K, Fukuda Y, Satomi M, Shimoyama T, Inaba Y, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Okamoto K, Kobashi G. Dietary risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease A Multicenter Case‐Control Study in Japan. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. 2005 Feb; 11(2):154–163.

- Park JB, Yang SK, Byeon JS, Park ER, Moon G, Myung SJ, Park WK, Yoon SG, Kim HS, Lee JG, Kim JH. Familial occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease in Korea. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2006 Dec 1; 12(12):1146–1151.

- Sood, A.; Midha, V.; Sood, N.; Bhatia, A.; Avasthi, G. Incidence and Prevalence of Ulcerative Colitis in Punjab, North India. Gut. 2003, 52(11), 1587–1590.

- Pinsk, V.; Lemberg, D. A.; Grewal, K.; Barker, C. C.; Schreiber, R. A.; Jacobson, K. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the South Asian Pediatric Population of British Columbia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102(5), 1077–1083.

- Shivashankar, R.; Lewis, J. D. The Role of Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Current Gastroenterol. Reports. 2017, 19(5), 22.

- Shi, C.; Li, H.; Qu, X.; Huang, L.; Kong, C.; Qin, H.;; et al. High Fat Diet Exacerbates Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Changes Gut Microbiota in Intestinal-specific ACF7 Knockout Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 537–545.

- Guerreiro, C. S.; Calado, Â.; Sousa, J.; Fonseca, J. E. Diet, Microbiota, and Gut Permeability—the Unknown Triad in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 349.

- Simopoulos, A. P.;. Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Autoimmune Diseases. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2002, 21(6), 495–505.

- Xie R, Sun Y, Wu J, Huang S, Jin G, Guo Z, Zhang Y, Liu T, Liu X, Cao X, Wang B. Maternal high fat diet alters gut microbiota of offspring and exacerbates DSS-induced colitis in adulthood. Front. Immunol. 2018 Nov 13;9:2608.

- Steiner, S. J.; Noe, J. D.; Denne, S. C. Corticosteroids Increase Protein Breakdown and Loss in Newly Diagnosed Pediatric Crohn Disease. Pediatr. Res. 2011, 70(5), 484–488.

- Arab, A.; Mehrabani, S.; Moradi, S.; Amani, R. The Association between Diet and Mood: A Systematic Review of Current Literature. Psychiatry. Res. 2019, 271, 428–437.

- Bahramsoltani, R.; Farzaei, M. H.; Farahani, M. S.; Rahimi, R. Phytochemical Constituents as Future Antidepressants: A Comprehensive Review. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 26(6), 699–719.

- Szewczyk B, Poleszak E, Sowa-Kućma M, Wróbel A, Słotwiński S, Listos J, Wlaź P, Cichy A, Siwek A, Dybała M, Gołembiowska K. The involvement of NMDA and AMPA receptors in the mechanism of antidepressant-like action of zinc in the forced swim test. Amino Acids. 2010 Jun 1; 39(1):205–217.

- Cass, W. A.; Smith, M. P.; Peters, L. E. Calcitriol Protects against the Dopamine‐and Serotonin‐depleting Effects of Neurotoxic Doses of Methamphetamine. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1074(1), 261–271.

- Arab, A.; Golpour-Hamedani, S.; Rafie, N. The Association between Vitamin D and Premenstrual Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Current Literature. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38(7), 648–656.

- Tardy, A. L.; Pouteau, E.; Marquez, D.; Yilmaz, C.; Scholey, A. Vitamins and Minerals for Energy, Fatigue and Cognition: A Narrative Review of the Biochemical and Clinical Evidence. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1.