Abstract

Dissatisfied users of public services may choose to voice or exit. But when does voice emerge? To answer this question, we deploy Hirschman’s exit, voice, and loyalty (EVL) model. We set out an ‘available alternatives’ hypothesis—increasing the number of exit options reduces voice—in contrast to an ‘effective voice’ hypothesis where voice is lower when there is no choice. We expect the exit-voice relationship to be moderated by loyalty; and providers that respond to user voice improve satisfaction and reduce exit. We evaluate these hypotheses in a survey experiment on publicly funded doctors’ services in the UK. We find no effects of the number of exit options on voice, nor evidence for loyalty as a moderator. A response by the provider results in higher satisfaction and lower intention to exit, strengthened by loyalty. Providers can promote satisfaction and discourage users moving to alternative providers by responding to voice.

Introduction

Users may respond to a decline in the quality of public services in two ways: voice a complaint or exit to other providers. The former is familiar as political and consumer participation; the latter is often designed into public service provision as choice and competition, justified through alleged benefits for service users and efficiency gains (Osborne and Gaebler Citation2000; Dowding and John Citation2009; Propper, Wilson, and Burgess Citation2006; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017). Although writing nearly forty years ago, Albert Hirschman’s famous exit, voice, and loyalty (EVL) model raises a salient contemporary concern that expanding choice may reduce voice because having more exit options reduces the incentive to complain (Hirschman Citation1970). In this model, users exit instead of voicing concerns to providers in ways that could improve performance. Hirschman also includes loyalty into his model, which is attachment to the current provider and moderates the tendency to exit. In his use of loyalty and account of dissatisfaction, Hirschman is surprisingly up to date, as his approach is consistent with contemporary perspectives in public administration that recognize rational economic-actor models of exit in markets do not match the evidence on how users actually respond to service decline (Dowding and John Citation2012; Jilke, Van Ryzin, and Van de Walle Citation2016). Even though there have been empirical evaluations of Hirschman’s general model in many contexts, there is still relatively little research in public management that addresses the effect of exit on voice (John Citation2017), a gap the research for this article seeks to fill.

The first section of this article sets out expectations about the effect of exit options on user voice following a decline in the quality of public services. We build on Hirschman’s work to explicate two versions of his model and outline the empirical implications. An ‘available alternatives’ hypothesis expects that voice will be higher when exit options are absent, and that increasing the number of exit options further reduces voice. An ‘effective voice’ hypothesis expects that voice rises when moving from no choice to at least minimal choice but declines as the number of exit options increase thereafter. In this version, users regard voice as ineffective when there is no possibility of exit; monopoly providers have no incentive to respond to voice so consumers/citizens do not bother to voice under such a circumstance. Following Hirschman, we argue that loyalty in the form of attachment to the current provider will reduce the effect of exit options on suppressing voice. Drawing on the dynamic element to Hirschman’s model, we hypothesize that, at a second stage, a response by the service provider acknowledging the decline in performance and pledging to improve performance will improve satisfaction and reduce exit intentions compared to no response.

The second section sets out a survey experiment to evaluate the hypotheses using a scenario of a decline in quality of publicly funded ‘General Practitioner’ (GP) doctor services in the UK National Health Service (NHS). Few studies evaluate Hirschman’s model with an experiment. Instead, most research about the exit-voice trade off in the Hirschman model has been observational, using case studies and survey-based investigations (Dowding et al. Citation2000; Dowding and John Citation2012). Panel data, such as used by Dowding and John (Citation2012), is an improvement on one-shot studies; but it lacks the well-known advantages of experimental designs of ruling out unobserved factors that are not possible to model for in a regression set up. The context of UK NHS public-doctor services is appropriate for testing the EVL framework because it is free at the point of delivery, and GP doctors’ practices are funded in part by a government payment per patient so have an incentive to retain them. The potential for exit options is of contemporary concern by policymakers because patient choice has been encouraged by recent reforms in several countries with publicly funded healthcare, including UK National Health Service (Tan et al. Citation2015).

The third section presents the findings that, contrary to Hirschman’s model, there is neither evidence of effects of the number of exit options on voice, nor for loyalty as a moderator. However, there is support for the dynamic part of the model, with a response by the service provider resulting in higher satisfaction and lower exit than no response. These effects are strengthened by loyalty of users to the provider. We conclude by discussing how these findings advance understandings of exit and voice, especially through the provider response to user dissatisfaction. We set out the implications for how service providers could interact with dissatisfied users.

The exit-voice tradeoff and decline in service quality

Decline in service quality—leading to dissatisfaction of users—is a common problem that providers of public services face. Hirschman was interested in theorizing how users react to service quality decline and what choices they were likely to make, in particular when they respond with voice, consisting of individual and collective user complaints about their situations to service providers, which has been a major topic of interest in public management (Dowding and John Citation2012).

He did not explicitly set out the foundations for his theory in individual psychology, but the theory is consistent with contemporary behavioral understandings of perception and reasoning, reactions that are not strictly explained by a simple rational actor model. Although writing in a period before the field of behavioral economics was developed, Hirschman's approach had already incorporated an approach to decision-making more attuned to human psychology than was common in mainstream economics at that time.

Hirschman started from a conception of a loyal consumer who is content to consume services and in general does not wish to complain. Routine behavior and regular interactions with other service givers play a role in generating loyalty. In his account, consumers are information-economising individuals who prefer to use shortcuts. Individuals are reluctant to assess actions unless they are forced to. As with conventional behavioral economics, costs and benefits are important, but psychological processes mediate perceptions of these costs. There is a threshold, whereby low or intermittent poor performance does not affect citizen satisfaction, but a major decline in quality is noticed. Consumers, particularly alert ones, then have to think what to do in response to decline.

The mix of cost-benefit and psychological considerations inform the next stage, which is the consideration of voice as a response to get things right. Dissatisfaction is a key experience for Hirschman consumers, something they wish to address in their actions and need to confront. In this world, loyal consumers prefer to use voice because it is seen as more appropriate as well as more convenient, with the intention of getting the service back on track. They will use voice first before considering the alternative of exit (Hirschman Citation1970:37; Dowding et al. Citation2000).

A key factor affecting voice is the extent to which exit opportunities exist. This is at the core of the EVL model, questioning the claim that switching products is the sole basis of market competition and efficiency. Pure exit does not always exist because of the lack of competition and the availability of alternatives. The question becomes how this variation in choice affects the citizen or consumer decisions to use the more useful and constructive form of citizen reaction for the organization, which is voice, which is also a route to greater efficiency. The availably of exit reduces the costs of getting a good service and places a reasonable alternative for the consumer: the greater the possibility of exit, the less likely the citizen is to voice. In his original work, he discussed the case of the nationalized monopoly rail service in Nigeria, in particular how citizen activism helped keep public officials on their toes. In that case, exit options undermine this route to efficiency by providing this alternative to voice, reflecting the tradeoff between increasing exit options and decline in voice.

In its simplified and pure form, lack of exit, as in the Nigerian rail example, generates voice as the only realistic option for the consumer or citizen: ‘The voice option is the only way in which dissatisfied consumers or members can react when the exit option is not available’ (Hirschman Citation1970:33), which he compares to classic monopolies of family, state, or church. This argument generates the expectation that when choice is limited voice is encouraged, and when choice expands, voice declines.

In other parts of the book he makes his approach subtler by arguing that there can be a positive interaction between exit and voice. Consumers or citizens might use exit constructively to threaten voice for which they need some degree of exit to be credible. As Hirschman writes, 'the role of voice would increase as the opportunities for exit decline, up to the point where, with exit wholly unavailable, voice must carry the whole burden of alerting management to its failings (Hirschman Citation1970:34). In other words, the consumer or citizen has less incentive to voice when there is no possibility of exit and it cannot be threatened.

Voice itself is more variegated than was originally recognized by Hirschman. As argued by Dowding and John (Citation2012), voice is a complex act that encompasses individual actions that the individual does not need cooperation to carry out and more collective acts where such cooperation is needed. In this way, we consider voice both as individual where a user complains and collective when the user cooperates with other users to raise a complaint.

Even though Hirschman's idea has been heavily cited in the literature in public policy and public management, there have been relatively few applications to the study of public services and very little experimental evidence (John Citation2017). The main evidence about the exit and voice in public management comes from studies of urban services in the 1980s and 1990s, in particular survey work on local public services, satisfaction, and citizen choice (Sharp Citation1984b, Citation1984a; Lyons, Lowery, and DeHoog Citation1992; Lyons and Lowery Citation1989; DeHoog, Lowery, and Lyons Citation1990). The work of Lowery, Lyons, and deHoog took a different theoretical tack based on a typology of responses to dissatisfaction as captured by the Exit, Voice, Loyalty and Neglect (EVLN) framework, and draws on the work of psychologist Caryl Rusbult (Rusbult Citation1980; Rusbult et al. Citation1988). It is important to note that EVLN is a departure from Hirschman in its use of concepts even though it is inspired by him (Dowding et al. Citation2000; Dowding and John Citation2012). More recent work includes sector-based studies (Egger de Campo Citation2007), assessments of providing information about poor service performance on citizen voice (James and Moseley Citation2014), and exit-voice intentions of public employees (Whitford and Lee Citation2015). Researchers have also examined the effect of varying the number of exit options (contrasting three exit options with eighteen) following decline in service quality on the whether people exit. This research found that the higher number of exit options reduced exit consistent with choice overload creating cognitive burdens and reducing users’ motivation to choose (Jilke et al. Citation2016). However, there has been little study of the effect of different amounts of exit options on voice.

We derived a set of hypotheses from the logic of Hirschman's writing to examine the effect of exit options on voice.Footnote 1 We assessed them in a survey experiment that tested for hypothesized effects of exit options through the availability of choice of alternative provider. We varied the number of exit options with three treatment groups: G1 = only their own GP (no choice); G2 = choice of own GP plus one other (minimal choice); and G3= choice of own GP and four others. G1 captures the idea that in some situations there is no choice, which means consumers or citizens cannot use the exit option as leverage for voice, and also have no exit option to respond to dissatisfaction; G2 is a situation where there is choice, but it is the minimum amount of choice available consistent with there being choice; and G3 is four alternative providers, constituting a higher amount of available choice. In this way, we wanted to have a set of choices that clearly indicated that the user had substantially more than the minimal choice set, but not to many options as potentially to introduce issues arising from choice overload that have been found in the case of providing a double-digit number of options of public service providers (Jilke et al. Citation2016).

The first hypothesis is derived from the basic exit-voice relationship that extends from a more choice (G3) through minimal choice (G2) to pure monopoly (G1).

H1: When experiencing service failure, respondents will voice to the extent they experience lack of choice: G1 > G2 > G3.

The second hypothesis is derived from the part of Hirschman’ theory that some exit is necessary for voice to occur even if more extreme levels of exit options beyond minimal choice reduce voice, which is derived from Hirschman's more subtle approach to the effect of exit options discussed earlier. Here no choice (G1) actually exhibits less voice compared to minimal choice (G2), even though more choice (G3) reduces voice compared to minimal choice (G2). This is because voice is a substitute for exit when exit is less available (G2 compared to G3), but not in the extreme case when there is no choice (G1) because voice will be seen as ineffective unless there is at least some potential exit which pressures providers into responding to voice. Without minimal exit options people will perceive insufficient pressure and so will not voice. In this way, there is a positive relationship between increasing exit options and voice when comparing no choice to minimal choice (comparing G1 with G2). Beyond this situation where there is at least a minimal level of choice (two providers), these consequences for voice are outweighed by the availability of more choice, which strengthens the depressing effect of more exit options on voice. This feature of the model is reflected in is a negative relationship when comparing minimal choice to a higher amount of choice (comparing G2 with G3).

H2: When experiencing service failure, respondents with no choice will voice less than those who have minimal choice, while respondents who experience a wider range of choices will voice less than those who have minimal choice: G1 < G2 > G3.

Associated with H2, we consider the mechanism by which increased choice promotes voice through users perceiving that providers subject to competitive pressures have more incentive to respond to both their individual and collective voice than those having a monopoly in provision. This perception is reflected in users perceiving their voice as more efficacious with increasing exit options. Consistent with the distinction between individual and collective voice (Dowding and John Citation2012), we argue that exit is more attractive when there is collective action involved.

H3: The reduction in voice in response to exit options is greater for collective voice (with other patients) than individual voice in all comparisons where a reduction in voice is expected.

Hirschman also considered loyalty, which has caused a lot of critical comment over the decades about its lack of clarity role in the model, notably by Barry (Citation1974) who referred to it as an 'equation filler'. Hirschman (Citation1970:77) defined it as a special attachment to the current provider, whereby loyal individuals are in general willing to use low cost voice to rectify decline and do not necessarily always utilize exit where it is available. Additionally, Hirschman’s model expects a differential response to dissatisfaction arising from service decline because users vary in their loyalty. In the model, loyalty itself is more of a psychological disposition, affected by habit, routines, and lack of willingness to change, and a liking of the people who are in an organization a person is being loyal to. This relates to The Exit, Voice, Loyalty and Neglect (EVLN) framework, which was an attempt to introduce a more psychologically grounded account of individual reaction to decline (Lyons et al. Citation1992). Even though we do not use the full framework of EVLN, we deploy its insights to view loyalty, which moderates the effect of exit options on voice, as something that is a function of personality or past experience of individuals.

We examine two versions for loyalty, which are consistent with Hirschman but potentially have different moderating effects. First, there is domain specific loyalty to a service provider as reflected in length of time they spend with that organization in that service area. The expectation is that loyalty reduces the size of the effect of having more exit options in all comparisons because loyal users are less affected by having options to exit. Second, there is general loyalty to providers of services in multiple domains. This form of generalized loyalty leads those who switch less in other domains of service provision in their lives also to show more loyalty to the specific provider. For people with higher generalized loyalty, the effect of being given more exit options will be lessened by increasing loyalty on this measure.

H4A: Prior length of time with an actual GP (domain loyalty) reduces the effect of the choice option on voice (as a moderator in H1 and H2).

H4B: Lower switching behavior in other contexts (general loyalty) reduces the effect of the choice option on voice (as a moderator in H1 and H2).

In H5, we introduce perceived efficacy of individual and collective voice, which according to Hirschman is influenced by the amount of exit available. This is necessary for the ‘effective voice’ version of the model to operate. More exit options are perceived as creating greater competitive pressure on providers to respond to voice, so this pressure increases perceptions of voice efficacy.

H5: The perceived effectiveness of voice will increase the greater the exit options that are available: G1 < G2 < G3.

Hirschman’s model contains a dynamic element, in the response of the service provider to inform service users about providers’ own views about performance. In our research, we build on this aspect of the model to consider expectations about the effect of provider’s explicitly recognizing the decline in service quality and pledging to improve performance in communication with service users. Where choice is available, this response is a further important factor on user satisfaction and intention to exit. In Hirschman’s model, not responding harms satisfaction and increases subsequent exit. In this way, the relationship between exit options, voice and exit is dynamic. The effect of exit options is felt not only in initial voice but whether respondents think their voice has been responded to by the organization. These reactions emerge over time as consumers wait for a complaint to be replied to. The organization is not passive but can feed back to the individual so long as this is done credibly. Such feedback can reduce dissatisfaction, and reduce exit too. Hirschman saw response to voice as important for organizational survival, with organizations that are not able to respond in a way that satisfies those who voice concerns risking subsequent exit of these users and further decline.

We examine the dynamic aspect of Hirschman’s theory using a second randomization after the initial manipulation of exit options and measurement of voice. At the second stage, we manipulated a report of a response (R) by the provider to users’ voice. In the case of those allocated to group R1, there is no response, with the R2 group receiving a response. This manipulation examines the effect of responsiveness after individuals either voiced or did not voice following the decline in service quality with the response phrased generically.

H6: If there is a response to the service failure by the provider then satisfaction at the end of the scenario is higher than if there is no response: R2 > R1.

Our focus is on the effect of receiving a response or not on participants’ satisfaction but, as a guide for future research, we also assess factors that affect the influence of receiving a response on these outcomes. Because of our focus on whether participants voiced individually or collectively we examine if there are differences in the effect of response depending on whether they voiced in the first stage.

H7: As a moderator of H6, the difference in satisfaction will be greater for those participants that voiced (in any form) compared to those that did not voice.

As well as satisfaction, there is an impact on exit from being responded to by the provider because this option is potentially not needed by users if they received a response. The effect on exit is only relevant for the groups of participants to whom exit was initially presented as being an option (because those in G1 never had an exit option). We hypothesize that receiving a response from the provider will make people less inclined to exit.

H8: If there is a response to the service failure by the GP then exit is lower than if there is no response R1 < R2 (for those in G2 and G3 only).

In H9 exit is minimized if there is a response but when consumers reach a threshold whereby dissatisfaction leads to giving up on the provider by exiting and where lack of response to voice is the last straw, which is a more direct test of Hirschman. A test of this is whether the exit response is affected by participants’ voice at the first stage.

H9: As a moderator of H8, the difference in exit will be greater for those participants that voiced compared to those that did not voice (for those in G2 and G3 only).

Study design

We assessed these hypotheses with a survey experiment. The study was conducted for the context of public health services in the UK, using the specific example of local ‘general practitioner’ (GP) doctors’ services. General practitioners work with nurses and other staff to give advice and treatment to patients on a registered list. They treat a wide range of minor medical conditions, manage on-going conditions, and refer patients to specialist services as required. Individual users are signed up to receive medical services from GP practices, and these practices constitute the service providers for the experiment. In this context, the survey experiment design used for the study is preferable to a field experiment because it allows the amount of choice to be manipulated by researchers in a way that would raise ethical concerns in a field experiment (James, John, and Moseley 2017). Restricting exit options following a decline in the quality of service provider would effectively lock in service users to receive this level of performance. At the same time, survey experiments using high-quality representative samples share the benefit of field experiments of external validity to groups beyond the experimental participants that are the focus on hypothesized effects (Mutz Citation2011), in this case to the general population using doctor’s services.

Public health services in the UK are suitable for the experiment because they are universally provided free at the point of delivery and there is varying amounts of choice typically available to service users, along with reforms to increase available choice (Tan et al. Citation2015). Variation in the number of GP practices is evident in practice with about ten per cent of the population having access to fewer than two practices in a three-kilometre radius whilst others have more options and some practices, including within this radius of distance, are full and not accepting new patients (National Audit Office Citation2015). Furthermore, people consider the possibility of moving between different practices. In a survey, 52.0% of respondents said they would consider registering with a practice close to where they lived other than their current one (Lagarde, Erens, and Mays Citation2015). In surveys of patients who actually moved practice, 13.9% reported this was because of dissatisfaction with their previous provider (Tan et al. Citation2015).

The survey experiment incorporated a scenario of a sharp decline in service quality for the GP practice from a previously outstanding level of service, and emphasized the decline on a range of aspects of service provision. The scenario also noted that this decline was recognized by an independent inspector of quality. In this way, the participants were given clear information both that the performance had declined from previously being outstanding above the performance of providers in general, and were given assurance about the source of the information to boost its credibility. The scenario-based design further enabled the amount of exit to be manipulated in a realistic standardized scenario about response to decline, showing a different number of practices available within a five-mile radius. This distance was chosen as an outermost boundary of what would be a believable typical maximum distance to travel to a local doctor in the UK given distances actually traveled which in the large majority of cases do not exceed this amount (National Audit Office Citation2015).

Statistical power

The experiment had three equal-sized groups of 500 each. With power set at 80% and to perform two-sided tests with an alpha of p=.05 on a scale of 1–10 (where we assume the comparison point is five, the mid-point), the study has the ability to detect a difference of 0.1774 between each of the experimental groups. We did not have strong priors of the expected effect size; much depended on the salience of the scenarios, which we did not know in advance. The sample size overall is similar to other survey experiments about public services that have detected hypothesized effects (James and Moseley Citation2014; Jilke et al. Citation2016). We are confident that the sample size for the current study provides fair tests of the hypotheses.

The large number of hypotheses, and different ways to test them with individual and collective voice, means we need to avoid reporting correlations that might have occurred by chance. As a result, we adjust the p-values according to a well-known correction for multiple comparisons (Benjamini and Hochberg Citation1995). The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure is less stringent but more acceptable than the classic Bonferroni adjustment, which is widely accepted to be overly conservative. In Appendix 9, we report both these corrections for all thirty tests we carry out in this article, and discuss them in the results section below.

Study implementation

The study was carried out in July 2018. The survey experiment was implemented online by the survey company, Survation, using the banks of its partner companies to recruit subjects. Subjects were allocated to a quota according to sex, age, and region to ensure representativeness across the UK.,Footnote 2 with recruitment happening after registration. Respondents were drawn from its panel of adults (aged over 18 years) living in the UK. The company invited 1,800 respondents to participate in the survey in order to guarantee a sample of 1,500 when disqualifications and partial responses were accounted for. Participants were first asked to consent to the research; then they filled out demographic questions. Respondents who went extremely slowly or very speedily in the first questions were excluded before randomization as not engaging with the task. In order to guarantee that the population that was sampled those who answered ‘outside the UK’ for the question ‘Where do you currently live?’ and those who answered ‘under 18′ for the question ‘What age are you?’ were disqualified.

The survey included two points at which the sample was randomly split and with each subgroup allocated a separate treatment. In the first case the sample was split into three experimental groups with different amounts of choice. To achieve this a hidden value was inserted into the script, which allocated a random number between one and three to respondents. The respondents were then shown an image and accompanying text that corresponded to their allocated number of options. Respondents were given one scenario in which they had no exit option (G1); another group got a scenario with minimal choice of one exit (G2) while the remainder were shown a choice of four alternative providers (G3). The randomization achieved an equally balanced sample of respectively 33, 35, and 32%.

For the second randomization, the sample was again randomly split, this time into two. Respondents were either allocated to one scenario (R1) in which the GP practice did not respond to patient comments or another (R2) in which the GP practice did respond. In the second randomization, the split between groups was 51 and 49%.

All questions throughout the survey were required and respondents could not proceed until they had answered the previous question. The survey utilized a slider scale of 0–10 in several questions. To ensure the best data the extremities were clearly labeled while the default option on the slider was 5 (the mid-point on a scale of 0 − 10). Respondents had to click the slider to answer the question. One question on the script was an open text question as check to help validate responses, which required respondents to enter a number between 0 and 100.

Only those respondents who were randomly allocated in the first instance to a sub-sample where they were presented with an exit option were shown the final question about exit in the script (because it would not make sense to be asked about exit when it was not presented as an option). To achieve this, those who received a random number of one in the first randomization (group G1 with no exit option) were excluded from answering that question.

On 11 July the survey was given a ‘soft launch’, which received 107 responses. This allowed the survey questions to be piloted and to ensure that the randomisations worked. Once these checks were finished, the survey was launched on the 12 July and then closed the day after. The final sample size was 1,528. We do not report all the details of the survey and tests of its validity in the main text of the paper, but these are contained in the online appendices: Appendix 1 contains the survey; Appendix 2 reports descriptive statistics; Appendix 3 shows balance checks; and Appendix 4 gives the details of the manipulation check. In addition, the appendices report additional statistical analysis: Appendix 5 reports the results with covariate adjustments; Appendix 6 provides some additional tests of hypotheses 6 and 7; Appendix 7 supplies ordered probit estimates of the OLS regressions reported in the paper; Appendix 8 contains a table of correlations of the covariates used in the regression analysisFootnote 3 ; and Appendix 9 reports the corrections for multiple comparisons.

Results

As the voice variables are ten-point interval scales, we used two-sided t-tests to appraise comparisons between the groups. Regression (OLS) tests for experimental differences, using one of the experimental groups as the baseline (e.g., G1 for Hypothesis 1 and G2 for Hypothesis 2). Additional models apply the covariates of region, sex, age, education, household size, employment status (full time versus other), band of household income, education (scale or binary variables), and ethnicity/Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME)(white/BAME).

We examine each hypothesis in turn. contains the basic data to interrogate hypotheses 1 and 2. In the table, none of the differences is statistically significant (with the exception for the difference between minimal and extensive choice for collective efficacy, which is significant at the ten per cent level, t = 1.7).Footnote 4 The hypotheses are also examined by the regressions in , which include interactions to examine hypotheses H4A and H4B about loyalty as a moderator. H1—that when experiencing service failure respondents will voice to the extent to which they experience lack of choice—is not supported for individual or collective voice (see , 2A, and 2B). For H2—that when experiencing service failure, respondents with no choice will voice less than those who have minimal choice, while respondents who experience a wider range of choices will voice less than those who have minimal choice—is also not supported for individual or collective voice (see , , and ). Nor is there a difference between collective and individual voice (H3). H4A, the longer prior length of time with an actual GP (loyalty) reduces the effect of the choice option on voice (as a moderator in H1 and H2), is also not supported for either individual or collective voice (see and ). H4B— lower reported switching behavior in other contexts (general loyalty) reducing the effect of the choice option on voice (as a moderator in H1 and H2)—is also not supported for individual or collective voice (see and ). H5 is not supported either, as there is no statistically significant difference in conditions for the perceived effectiveness of voice.

Table 1. Mean levels of voice and efficacy by experimental condition.

Table 2A. Individual voice moderated by loyalty, OLS regression.

Table 2B. Collective voice moderated by loyalty, OLS regression.

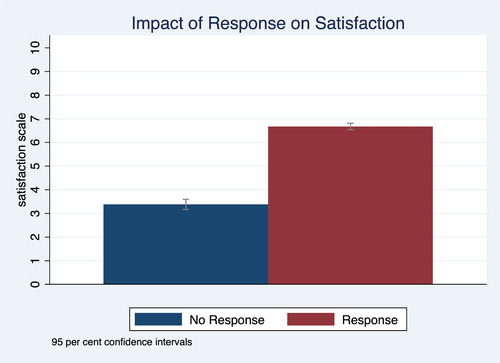

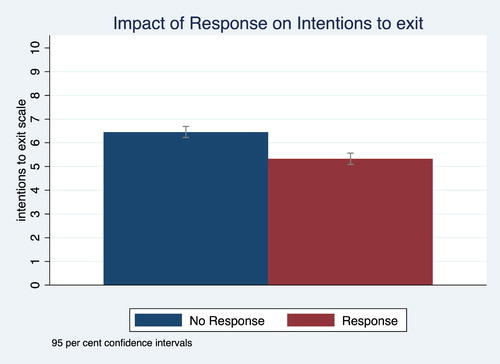

There is much clearer support for the hypotheses from about the effect of provider response to patients’ complaints about service failure. For H6, a response to the service failure by the GP results in higher satisfaction at the end of the scenario than if there is no response, so R2 > R1 is supported (see ). A response raises satisfaction by 3.30 on the scale (SD = 2.91), a Cohen’s d effect size of 1.13 (1,528 observations). If there is a response to the service failure by the GP, then exit is lower than if there is no response R1 < R2 (examined for those respondents in G2 and G3 only) so H8 is supported; a response lowers intention to exit by 1.13 on the scale (SD =2.80), a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.40 (1,022 observations). As well as in , these relationships are displayed (with 95% confidence intervals) in and . Appendix 9 shows that these highly significant differences remain significant at conventional levels after adjustments for multiple comparisons.

Table 3. Reactions to responses from GP moderated by loyalty and switching behaviors, OLS regressions.

As additional hypotheses, we tested for interactions between loyalty and getting a response from the provider. These findings are reported in . Having a response by the GP has a bigger effect for more loyal users (on both measures) for both the increase in satisfaction from a response and a bigger reduction in exit. These findings are sensitive to corrections for multiple comparisons: two remain within conventional levels of statistical significance; the other two become significant only at the ten per cent level (Appendix 9).

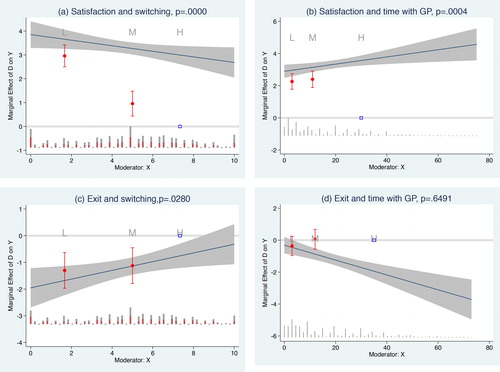

We tested whether the four interactions follow the assumption of linearity, carrying out additional analysis and checks proposed by Hainmueller, Mummolo, and Xu (Citation2019). They recommend dividing each sample into three equally sized bins (low “L”, medium “M”, and high “H”), then re-estimating, which allows for a more direct investigation of non-linear relationships as well producing a Wald test to reject the null. displays these panels with the probabilities displayed at the head of each one. They provide a more effective way of examining the interaction at different levels than the standard marginal plots that appear in most papers.

Figure 3. (a) Satisfaction and switching, p = 0.0000. (b) Satisfaction and time with GP, p = 0.0004. (c) Exit and switching, p = 0.0280. (d) Exit and time with GP, p = 0.6491.

The panels for satisfaction, (a) and (b), reflect significant probabilities for the Wald test with binned estimates some distance from the linear estimated line and variation in the estimate moderator. In both cases, the interaction at the high levels is not present, with the main impact at low and medium levels of switching and time with GP. The exit equation is significant for the switching measure, but not significant for time with GP. Note (c) reflects the reduction in exit when there is greater loyalty conditional on response from the GP, which we can safety interpret at a true relationship at medium and high levels of loyalty for switching behavior. However, no relationship is evident in panel (d) for time with GP.

Finally, we examine the findings for hypotheses H7 and H9 about whether prior voice moderates the impact of responsiveness on respectively satisfaction and exit. The results are reported in Appendix 6. We find some evidence of moderation in that the response from the GP slightly increases satisfaction for those more likely to have voiced collectively at stage one, which is goes against the disconfirmation of expectations whereby the more vocal disappointed consumers reduce their satisfaction more than non-participators. Instead, those who voiced collectively respond slightly better when responded to. The corrected p-value, when multiple comparisons are taken account, reduces to .086 for H7, so is only statistically significant at the ten per cent level (see Appendix 9). The interactions for prior voice and response from provider on intention to exit are noisy so do not show a relationship.

Conclusions

We deployed a scenario about service decline to assess the effects of increased exit options on voice. But we do not find support for our hypotheses of an impact of lack of choice on voice. Although our distinction between no choice and constrained choice is a novel extension of EVL, we do not find evidence for it in these findings. It should be stressed, however, that we have not refuted Hirschman’s voice/choice trade off. Our study is a test in a particular setting and uses a specific way of measuring the impact of choice in a survey experiment. It could be that voice in the UK health system on average is not responsive to the opening up of choice, and this could vary by respondents’ experiences with the amount of choice actually available to them where they live. It could be that choice is not influential for respondents where there is not a great deal of effective choice for them in the health system given where they live. In some urban areas in particular, actual available choice may increase our survey respondents’ reaction to the choice scenarios. We found some evidence that is suggestive of this interpretation, with respondents in London more responsive than the average, and future research could examine more choice-rich environments.Footnote 5

On the other hand, there is clear evidence for an effect of responses by public organizations to decline: response boosts satisfaction and reduces intentions to exit. This experimental evidence bolsters findings from previous observational studies (e.g., Dowding and John Citation2012) that shows that people who do not get a response from a provider are less satisfied and more likely to exit. There is a further positive interaction between loyalty and receiving responses from the provider about service quality. On both measures of loyalty (lower switching behavior and having spent a longer term with their actual GP), higher loyalty boosts the positive effect of getting a response from the GP on users’ satisfaction. There is a relationship between lower switching behavior and reduction in their intention to exit (although not evident for time with GP). Overall, the dynamic aspect of the Hirschman model receives support. This finding suggests that public organizations would do well to respond to declines in service quality that are noticed by their users.

The findings are directly relevant to the effects of exit options and provider response in public health services, an important issue not only in the UK but in several other countries where recent reforms to increase choice have been undertaken (Propper et al. Citation2006; Miani, Pitchforth, and Nolte Citation2013). Greater use of choice mechanisms and encouraging provider responsiveness has also been the focus of policy in several areas of public services, notably in education and social care (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017). Whilst these domains differ from the current study the findings are likely to apply there too, particularly where (as in the context of this study) services are free for users at the point of delivery and a portion of providers’ income comes from attracting users and leveraging the funding associated with them.

There are well-known limits to the external validity of survey experiments, but the scenario approach has a clear advantage in this context. It would not have been possible to implement a field experiment as there are practical and ethical difficulties of limiting exit options for those receiving a service suffering a decline. If these difficulties can be overcome, future research could examine some aspects of the questions explored here in field contexts. There is further potential to develop the findings that provider responses matter for satisfaction and intentions to exit. In particular, research could examine different kinds of response following service failure. The current study used a response in which the provider both accepted that there had been a decline and claimed to be working to ameliorate the situation. This response entails taking responsibility rather than giving explanations or trying to shift blame. Experiments could examine other forms of provider response thereby further assisting public managers by providing evidence about different ways to communicate in attempts to restore confidence in public services.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank University College London and University of Exeter for funding. We are grateful to Survation, which was commissioned to carry out the study, in particular we are grateful to Marius Mosoreanu and Chris Hopkins for their advice on the design. We thank participants at the lunchtime Quantitative Political Economy (QPE) “brownbag” seminar in Department of Political Economy King’s College London, 6 February 2019, and those at the EGPA Behavioural Public Administration study group session at Belfast, 12–13 September 2019, for their comments and reactions to earlier versions of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These hypotheses (H1–H9) were pre-registered on 7 September 2018: John, Peter, and Oliver James. 2020. “The Exit-voice Trade-off and the Decline of Public Services.” OSF. February 3. osf.io/btce8. Other hypotheses are exploratory.

2 The company also had “soft targets” of education (those without a degree; GCSEs and A levelsGraduates; MA & equivalent and higher) so as to improve representativeness.

3 Data and replication code are available from Peter John and will be deposited in a public archive.

4 Such a difference does not survive a correction for multiple comparisons: see Appendix 9, test 22.

5 There is some indication of a treatment effect of constrained choice for collective voice on the interaction of London respondents (coef = 1.33, t = 2.27).

References

- Barry, Brian. 1974. “Review of Review of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organization, and States, by Albert O.” British Journal of Political Science 4(1):79–107. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400009376.

- Benjamini, Yoav , and Yosef Hochberg . 1995. “Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 57(1):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x.

- DeHoog, Ruth Hoogland , David Lowery , and William E. Lyons . 1990. “Citizen Satisfaction with Local Governance: A Test of Individual, Jurisdictional, and City-Specific Explanations.” The Journal of Politics 52(3):807–37. doi: 10.2307/2131828.

- Dowding, Keith , and Peter John . 2009. “The Value of Choice in Public Policy.” Public Administration 87(2):219–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.01732.x.

- Dowding, Keith , and Peter John . 2012. Exits, Voices and Social Investment: Citizens’ Reaction to Public Services . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dowding, Keith , Peter John , Thanos Mergoupis , and Mark Vugt . 2000. “Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Analytic and Empirical Developments.” European Journal of Political Research 37(4):469–95. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00522.

- Egger de Campo, Marianne. 2007. “Exit and Voice: An Investigation of Care Service Users in Austria, Belgium, Italy, and Northern Ireland.” European Journal of Ageing 4(2):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s10433-007-0047-3.

- Hainmueller, Jens , Jonathan Mummolo , and Yiqing Xu . 2019. “How Much Should We Trust Estimates from Multiplicative Interaction Models? Simple Tools to Improve Empirical Practice.” Political Analysis 27(2):163–92. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.46.

- Hirschman, Albert O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States . New edition. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

- James, Oliver , Peter John , and Alice Moseley . 2017. “Field Experiments in Public Management.” Pp. 89–116 in Experiments in Public Management Research: Challenges and Contributions , edited by Oliver James , Seb Jilk and Gregg G. Van Ryzin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- James, Oliver , and Alice Moseley . 2014. “Does Performance Information about Public Services Affect Citizens’ Perceptions, Satisfaction, and Voice Behaviour? Field Experiments with Absolute and Relative Performance Information.” Public Administration 92(2):493–511. doi: 10.1111/padm.12066.

- Jilke, Sebastian , Gregg G. Van Ryzin , and Steven Van de Walle . 2016. “Responses to Decline in Marketized Public Services: An Experimental Evaluation of Choice Overload.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26(3):421–32. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muv021.

- John, Peter. 2017. “Finding Exits and Voices: Albert Hirschman’s Contribution to the Study of Public Services.” International Public Management Journal 20(3):512–29. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2016.1141814.

- Lagarde, Mylene , Bob Erens , and Nicholas Mays . 2015. “Determinants of the Choice of GP Practice Registration in England: Evidence from a Discrete Choice Experiment.” Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 119(4):427–36. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.10.008.

- Lyons, William E. , and David Lowery . 1989. “Citizen Responses to Dissatisfaction in Urban Communities: A Partial Test of a General Model.” The Journal of Politics 51(4):841–68. doi: 10.2307/2131537.

- Lyons, William E. , David Lowery , and Ruth Hoogland DeHoog . 1992. “The Politics of Dissatisfaction: Citizens.” Services, and Urban Institutions . Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Miani, Celine , Emma Pitchforth , and E. Nolte . 2013. “Choice of Primary Care Provider: A Review of Experiences in Three Countries.” Monograph. Retrieved Accessed January 15, 2021 https://piru.ac.uk/assets/files/Choice%20of%20primary%20care%20provider%20-%20a%20review%20of%20experiences%20in%20three%20countries%20final.pdf.

- Mutz, Diana C. 2011. Population-Based Survey Experiments . Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

- National Audit Office . 2015. “Stocktake of Access to General Practice in England.” HC 605 Session 2015-16 . London: NAO.

- Osborne, David E., and Ted Gaebler . 2000. Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector . New edition. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

- Pollitt, Christopher , and Geert Bouckaert . 2017. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis - Into the Age of Austerity . 4th edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Propper, Carol , Deborah Wilson , and Simon Burgess . 2006. “Extending Choice in English Health Care: The Implications of the Economic Evidence.” Journal of Social Policy 35(4):537–57. doi: 10.1017/S0047279406000079.

- Rusbult, Caryl E. 1980. “Commitment and Satisfaction in Romantic Associations: A Test of the Investment Model.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 16(2):172–86. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(80)90007-4.

- Rusbult, Caryl E. , Dan Farrell , Glen Rogers , and Arch G. Mainous . 1988. “Impact of Exchange Variables on Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect: An Integrative Model of Responses to Declining Job Satisfaction.” Academy of Management Journal 31(3):599–627.

- Sharp, Elaine B. 1984a. “Citizen-Demand Making in the Urban Context.” American Journal of Political Science 28(4):654–70. doi: 10.2307/2110992.

- Sharp, Elaine B. 1984b. “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty’ in the Context of Local Government Problems.” Political Research Quarterly 37(1):67–83. doi: 10.1177/106591298403700106.

- Tan, Stefanie , Bob Erens , Michael Wright , and Nicholas Mays . 2015. “Patients’ Experiences of the Choice of GP Practice Pilot, 2012/2013: A Mixed Methods Evaluation.” BMJ Open 5(2):e006090. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006090.

- Whitford, Andrew B. , and Soo-Young Lee . 2015. “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty with Multiple Exit Options: Evidence from the US Federal Workforce.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25(2):373–98. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muu004.