Abstract

The interactions and relationships between front-line regulators and the regulated impact the implementation of environmental policy. Much of the existing research to date investigates the regulatory enforcement styles of regulators or the compliance motivations of firms. It is equally important to consider the role of women and their experiences as front-line workers. This qualitative research is one of the first to provide insight into the untold stories of women on the front-lines of environmental regulation. Through an examination of original interview data from 25 environmental regulators with the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (DEPA) and Montana Department of Environmental Quality (MT DEQ), the findings suggest steps must be taken to ensure the voices of women on the front-lines of environmental regulation are no longer overlooked. Instead, we recognize how their day-to-day experiences impact our understanding of the implementation of environmental regulations.

Women make up half of the world’s population and should presumably represent our public institutions at a similar rate. Public administration and environmental policy research note this is not the case for a myriad of reasons (Smith, Citation2014; Sneed, Citation2007) ranging from, but not limited to, glass walls (Sneed, Citation2007), behavioral differences (Nielsen, Citation2015), gender stereotypes, and bureaucratic representation (Selden, Citation1997). However, most environmental regulation research to date focuses on regulatory interactions between regulator and the regulated (Pautz & Rinfret, Citation2013), overlooking the gender dynamics at play in policy implementation.

Importantly, “Women have been government employees now nearly a century and a half, and from the first days of their entry into public employment they had work experiences, career opportunities, and problems unique to them” (Stivers, Citation2000, p. 15). An examination into the environmental policy, policy implementation, regulatory policy, or front-line literature reveals a focused attention on women and regulation is infrequent (Bardach & Kagan, 2002/Citation1982; Lipsky, Citation1980; Pautz, Citation2009, Pautz & Rinfret, Citation2013. Since front-line actors are the ones most responsible for the success or failure of policy execution (Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2003), we should be aware of and consider how gender is an ever-present demographic characteristic that informs regulatory decisionmaking (Pederson and Nielsen, 2009). As a result, the focus here is to address: what is it like to be a woman on the front-lines of environmental regulation?

To address this question, we use a qualitative research approach, focusing on front-line regulators within Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality (MT DEQ) and the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (DEPA). Specifically, 25 MT DEQ and DEPA interviews are examined to investigate the perceptions from women and their male counterparts on the front-lines of environmental regulation. In order to contextualize their organizational realities, this paper uses Nisbet’s (Citation2010) work as a baseline to design a new theoretical approach—the gender-front-lines (GFL) framework. The findings call attention to a neglected population of study, perceptions from and about women, emphasizing the importance of gender in advancing our understanding about the front-lines of environmental policy. The interview data reminds us, “Gender is an important element of the story of how public administration came to define itself” (Stivers, Citation2000, p. 3).

A view from the street-level

A range of scholarship contextualizes the foundation for this paper. Specifically, investigations focused on street level bureaucracy, representative bureaucracy, gendered institutions, and gender stereotypes serve as necessary baselines to inform and situate this research. Each area of research illustrates why a clearer picture about the role of women on the front-lines of environmental regulation is essential to understand environmental policy implementation more broadly.

Street level bureaucracy, gender stereotypes & gendered institutions

To begin, street-level bureaucracy is a well-developed area of scholarship. Front-line workers, often referred to as street-level bureaucrats, as defined by Lipsky (Citation1980) are individuals that “occupy a critical position in American society” (p. 3). Riccucci (Citation2005) additionally suggests front-line workers influence policy implementation profoundly and with far less influence from management than we might expect. Simply put, front-line workers are charged with implementing vague legislative policy or regulatory language (Pautz & Rinfret, Citation2013).

In terms of environmental regulation, front-line actors (e.g. environmental regulators) are responsible for implementing and ensuring regulated facilities comply with regulation within a command and control structure (Rinfret & Pautz, Citation2019). Employed by an array of organizations—from pharmaceutical companies and water-treatment facilities to dry cleaners and quarries—members of the regulated community are responsible for dealing with environmental matters on a routine basis (Pautz & Rinfret, Citation2016). The implementation approaches of environmental regulators and their interactions have extensively been studied (Bardach & Kagan, Citation2002/1982; May & Winter, Citation2000; Nielsen, Citation2006.

Exploring the interactions of regulators and members of the regulated community reveal the realities of implementing environmental regulations on a daily basis. The study of these interactions often centers on the regulatory style a particular regulator may use. One perspective is regulators adopt an accommodative regulatory approach (Hutter, Citation1997), seeking cooperation with regulated firms. In contrast to this approach, the sanctioning approach (Hawkins, Citation1984) emphasizes coercion or other more punitive means of achieving compliance. Instead of regulators adopting one of the two approaches in their work implementing environmental regulation, research has demonstrated that regulators employ both approaches in varying combinations, depending on the circumstances, settings, and policy arenas (Braithwaite et al., Citation1987; Pautz & Rinfret, Citation2016). The general takeaway from this research is that we consider the interactions of the two parties largely responsible for the day-to-day work of environmental regulation, we understand what environmental protection looks like on the front-lines (Pautz & Rinfret, Citation2016).

When we consider regulatory interactions, we must also consider our bureaucratic institutions and those who occupy them. As Smith (Citation2014) succinctly notes, “A representative bureaucracy is one in which the characteristics are similar to the characteristics of those they serve. In theory, if the bureaucracy resembles those it serve, bureaucrats will implement policies in ways that benefit the demographic groups they represent” (p. 477). Representative bureaucracy contains two guiding principles—active and passive representation. Active representation assumes that if the bureaucracy looks like the public it serves, policies reflect the preferences of this public. Passive representation, “implies equal access to government positions promoting the empowerment and connection with government in diverse communities” (Rosenbloom, Citation1977). Using representative bureaucracy as a theoretical framework, scholars note the importance of studying the role of women to advance our understanding across policy areas. For example, Sneed (Citation2007) finds state bureaucracies present glass walls to describe obstacles that deter women from obtaining employment or positions in specific state-level agencies. Smith (Citation2014) argues women are more ethical than men in their decision-making approaches, but reportedly represent masculine traits to achieve leadership positions.

Representative bureaucracy is an important concept, but due to gendered institutions or gender stereotypes it is often not achievable because, “Organizations start out with the norms and values of their founders, and women and people of colour stand out against these largely white, male backgrounds” (Mastracci & Bowman, Citation2015, 858). Furthermore, Freeman (Citation1984) suggests bureaucratic hierarchical structures strips those on the front-lines (lower positions of the hierarchy) from making decisions, magnifying gender inequalities. Hierarchy reinforces social inequities because, “Managers have power over the managed, men over women, and whites over people of color, and so on” (Freeman, Citation1984, 29). Acker (Citation1992) more concisely classifies this as gendered institutions because our institutional structures are organized by gender and the absence of women. For Acker (Citation1992), “The only institution which has been defined by women is the family” (567).

Gendered institutions are also driven by stereotypes (Arora-Jonnson, Citation2009). Gender stereotype research employs the concepts communion and agency (Bakan, Citation1966) to define those that occupy organizations. More specifically, communion is defined as feminine—adopting approaches such as compassion or warmth in how individuals orient to others and their well-being. By way of comparison, agency is masculine, focused on goal attainment and defined as ambitious, assertive, or competitive. One common assumption is that due to substantial changes in employment and educational opportunities, gender stereotypes in public organizations would change over time. According to Donnelly et al. (Citation2016) this is not accurate because gender stereotypes persist because of occupational segregation, division of labor, uneven wages, and domestic work between men and women.

Women and environmental regulation: What’s missing?

According to Pederson and Nielsen (2019) the lack of representative bureaucracies, gendered institutions, and gender stereotypes may result in gender-biased decisonmaking. Men and women have been normalized to approach situations differently and therefore, can impact policy implementation. Limited studies, however, have applied the aforementioned scholarship to environmental policy and regulation. What we do know is Nielsen (Citation2015) argues gender affects our understanding of bureaucratic behavior.

For example, in Nielsen’s (Citation2015) examination of Danish regulatory institutions, behavioral differences effect specific tasks in a variety of jobs (e.g. environmental inspection, counseling high school students, elder care). Furthermore, Elmagrhi et al. (Citation2019) suggest the role of female directors in the implementation of environmental policy and regulation positively effect regulatory compliance and/or environmental performance in China. Yet, Arora-Jonsson and Agren (Citation2019) conclude, “Analyses of attempts at diversity in environmental organizations will remain fragmentary without understanding of how organizational practices constitute natures in the course of their work as much as how understanding of nature dictate organizational practice” (881). Despite these findings, a gap still exists with focused attention on the role of women on the front-lines of environmental regulation.

Arora-Jonsson (Citation2014) remind us the that ubiquitous discussion of gender in environmental policy research can be a stumbling block to seeing the inequities on the ground. As a result, this paper builds upon the existing aforementioned literature to examine the discursive frames or stories exhibited by regulatory actors on the front-lines of environmental regulation. Kamieniecki (Citation2006) argues theories of issue definition (e.g. agenda setting, agenda building, agenda blocking, framing) are useful for evaluating environmental regulation because they offer a conceptual framework to analyze the actors involved. This interpretative process considers the social interactions of persons to comprehend societal issues (Cook, Citation2018; Lewicki et al., Citation2003; Rinfret, Citation2011).

Moreover, scholars have used frame analysis to understand environmental policy issues more broadly. Frame analysis is an interpretative process in which scholars across disciplines (political science, sociology, criminology, and communications) consider the social interactions of persons to comprehend societal issues (Lewicki et al., Citation2003). Nisbet (Citation2010) recommends environmental policy is best examined through a series of frames, which include: social progress (improving quality of life), economic development/competitiveness (market benefit or risks), morality/ethics (terms of right or wrong), scientific/technical understanding (expert understanding), Pandora’s Box/Frankenstein’s monster (no turning back mentality), public accountability/governance (use or abuse of science in decsionmaking), middle way/alternative path (possible compromise position), and conflict strategy (battle of personality or groups). Arguably, Nisbet’s (Citation2010) framework is a beneficial starting point to create a new theoretical model to examine the role of women on the front-lines of environmental regulation, offering insight into an understudied area of research to date.

Montana and Denmark

To advance our understanding of the role of women on the front-lines of environmental regulation, this study uses an exploratory case study approach, comparing the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (MT DEQ; Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Citation2020a) and the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (DEPA). According to Creswell (Citation2013), the case study approach allows a researcher to examine the “real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple courses of information” (p. 97). Moreover, Yin (Citation2003) clearly states, “The case study method allows investigators to retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events—such as individual life cycles, organizational and managerial processes, neighborhood change, international relations, and maturation of industries” (p. 2). This study focuses on Montana and Denmark for a variety of factors.

First, the processes inspectorsFootnote1 use within their respective public organization (MT DEQ and DEPA) are comparative and similar. In the United States, the regulatory process is guided by federal statute (legislation/Congress) and rulemaking from the US Environmental Protection Agency, which is carried out by front-line regulators within the MT DEQ. In Denmark, the European Union and Danish Parliament set statutory guidance for DEPA environmental regulators on the front-lines to ensure compliance with the law. Additionally, the demographic makeup for Montana and Denmark are somewhat similar. In terms of population size—Montana contains approximately one million people and Denmark five million. Additionally, more than 80 percent of Montana and 90 percent of Denmark is white/Caucasian (Central Intelligence Agency, Citation2020; United States Census Bureau, Citation2020).

Second, their respective agency missions have strong commitments to the implementation of environmental policy. The MT DEQ mission states, “To protect, sustain, and improve a clean and healthful environment to benefit present and future generations.” The Danish DEPA suggests, “Our core objective is to implement nature and environmental legislation, balancing the use of resources and protection of human health and nature.”

Third, both have been exemplars in their focus on gender equity. Former Montana Governor Steve Bullock’s Office of the Governor initiated an Equal Pay Taskforce to address pay inequities in state level government. State level agencies like the MT DEQ receive directives from the Montana Governor’s office. Denmark has a Ministry for Equal Opportunities—responsible for finding ways to close inequities across government entities. However, very few women within the MT DEQ and DEPA are in top-level positions within their organizational structures.

Fourth, the length of time employed as a regulator, who they regulate, and educational background are similar. Specifically, the participants selected for this study were women and men who worked for their respective agency for more than five years, regulate heavy polluters (e.g. mining, coal, gas) and have educational backgrounds in science or law, most common for regulators (Pautz & Rinfret, Citation2013).

Data

A total of 25 interviews were conducted between May 2019 and January 2020 with MT DEQ and DEPA regulators—10 from Denmark and 15 from Montana. Of these interview participants, 14 were women and 11 men. We interviewed both men and women to determine how they collectively perceive the role of women on the front-lines of regulation. Although women are the focus of this study, it is also important to capture the perceptions of their male counterparts to determine if the discursive frames used, by gender, differ and how this effects women on the front-lines of environmental regulation.

The interviews took place in person and lasted approximately 45-60 minutes. All participants were asked the same questions.Footnote2 The interview questions were designed to obtain background information about regulatory processes, the role of gender, perceptions about their own work, and pathways for the future. Interviewing agency personnel allowed for inquiry into the types of arguments regulators use, their perceptions about their work, and their respective roles and experiences within their organizations. The snowball method was also employed, asking participants to identify additional persons to be interviewed (Gerring, Citation2007).

All interviews were transcribed into plain-text files by the author and one graduate student. We conducted a content analysis using NVivo, a qualitative software program, to examine participant interview responses. We uploaded the interviews as plaintext files into NVivo. We applied elements of Nisbet’s (Citation2010) work and our own to create a codebook. This codebook included the following codes (referred to as nodes in NVivo) from Nisbet (Citation2010): social progress (improving quality of life), morality/ethics (terms of right or wrong), scientific/technical understanding (expert understanding), public accountability/governance (use or abuse of science in decision-making); and our own additions: gender bias (if their gender was perceived to impact their work), stereotypical traits (masculine, feminine), unfair treatment (harassment by colleagues or regulated community), and emotional labor (responsibilities not in a job description, but tasks overwhelmingly completed by women). illustrates how we coded participant responses by gender.

Table 1. Coded samplesa.

Issues of reliability and validity surround content analyses. To ensure consistency in coding, we used NVivo to assure validity in our coding. The NVivo software allows for the researchers and subusers (e.g. a graduate student) to directly code raw data through its interface. A pretest detected mismatches or matches between coders. In addition, as the project progressed, the NVivo system tracked codes by user, tracking validity over time.

We argue the coded data presents apparent collective themes across the MT DEQ and DEPA to build a new theoretical framework for analysis. Such an approach provides understanding from the vantage point of the participants here into the role of gender and its consequences of how we implement environmental regulation on the front-lines. Importantly, this assists a growing body of research to “raise questions about the fact of women’s presence in bureaucracies … instead [of] taking them for granted…” (Stivers, Citation2000, p. 15). Moreover, it identifies what it is like to be a woman on the front-lines of environmental regulation, an understudied aspect of research to date.

The GFL framework

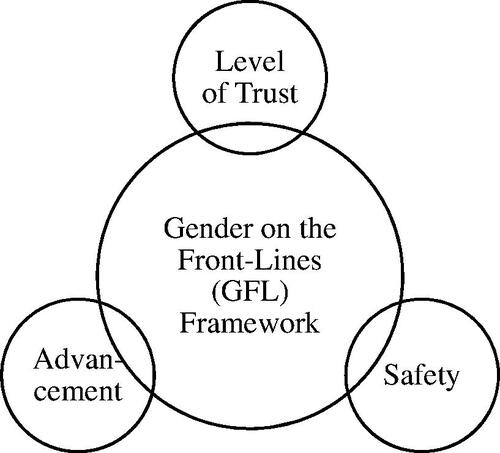

Importantly, a person’s narrative is “their preferred meaning-making” (Jones et al., Citation2014) and by listening to the “arguments presented that people, by nature, are inclined to impose meaning on the world and that when they do…” (Crow & Jones, Citation2018, p. 216). The aforementioned coded data was categorized into a new exploratory framework—gender on the front-lines (GFL) to capture the overall story of the interview participants. The GFL is defined by three interrelated themes: level of trust in expertise; safety; and advancement opportunities ().

Level of trust

The first element of the GFL framework is level of trust, the participants’ perceived knowledge and expertise. For many participants, they self-defined themselves as the “gatekeepers of regulatory knowledge,” defined by their training, experience, commitment to serving the public, and education. This knowledge is used to ensure businesses comply with the law, upholding their respective agency mission to protect the natural environment and engage the public in their decision-making processes.

Specifically, agency personnel within the MT DEQ or DEPA use their backgrounds in science, policy, or law to guide the implementation and compliance of environmental regulation. The majority of participants, regardless of gender, from both agencies stressed they were selected for their position based upon their expertise, however, differences exist in who trusts this knowledge.

Unanimously, DEPA and MT DEQ regulators stressed their expertise is valued by the general public and the regulated community, most of the time, due to long-standing relationships. On average, the regulators under investigation worked within their current position from 5 to 35 years. However, the role of trust varied across the data. Pautz and Wamsley (Citation2012) remind us trust is fundamental in regulatory interactions. Participants from the MT DEQ and DEPA suggested the longevity of their job impacted how they would classify their relationships with the regulated community or the general public.

For example, as one DEPA participant stated, “We have a dialogue with the companies on how they can move further along with environmental protection.” Similarly, a MT DEQ participant noted, “I think our relationships have been pretty positive because we have an open-door policy—we are here to provide guidance.” In addition to working directly with the regulated community, regulators must also meet with the general public to inform their decision-making. A DEPA participant recalled, “In addition to doing site visits with the regulated, we must also engage the public through public hearing. Folks show up making sure we are asking their community for input.”

Yet what was most apparent in the data was that the role of gender impacted participant perceptions regarding their apparent level of trust between those they regulate. The vast majority of Danish participants stressed gender did not impact the level of trust in their day-to-day interactions with the regulated community. Many argued that their expertise, regardless of gender, was trusted by their peers and facilities they work with on a daily basis. For instance, one participant stated, “I do not think that it matters; whether the regulator is male or female—they are equally respected by the party they meet.” Comparatively, the role of gender in regulatory interactions across MT DEQ data was mixed. One interviewee noted, “Most of the industry I interact with are men, but overall they are okay. There’s some hesitancy at the beginning of an inspection because I am a woman, but they get over it; generally, it is pretty positive.” According to another MT DEQ interviewee, “If you are a female regulator, it depends on the size of the firm if they trust your expertise or not.” Collectively, the perceived role of expertise is respected by their regulatory counterpart in Montana and Denmark; however, if you are a woman, it can impact trust levels with MT DEQ regulators.

Safety

The second element of the GFL is safety, which is interconnected to a regulator’s level of trust. Inevitably, if there’s a perceived lack of trust by their regulatory counterpart, as reported by many female participants, many of those same individuals experienced safety concerns. Safety is defined by a person’s physical well-being in their daily job.

For example, the vast majority of DEPA participants argued their safety at work has increased because of the trust in their work by regulatees and their development of technology for compliance protocols (e.g. drones for monitoring). One DEPA interviewee concluded, “Early on, we had too many spills within the harbor; it was dangerous, and hard work. Because of technology, the job is much safer.” Other interviewees, who had been with the agency for more than 10 years, noted relationships have strengthened over time and if conflict occurred, agency leadership would support front-line decisions, regardless of gender.

Many female MT DEQ participants demonstrated concern for their physical safety. Several women described stories where women were harassed, bullied, or not taken seriously. Their male colleagues confirmed such stories. A few participants suggested the size of the firm impacted the treatment of female front-line staff. In one person’s opinion, “The larger the firm, the more experience they have working with a myriad of individuals; however, smaller [mom and pop] facilities in rural parts of the state might not like working with a woman.” For example, one MT DEQ participant shared when she was writing a notice of violation, “the onsite company personnel asked to take a photo of her.” Another MT DEQ participant suggested when making difficult decisions about compliance outcomes, a regulatee “showed his gun.” Men, on the other hand, did not document these experiences in their daily interactions with the regulated community.

Advancement

Trust and safety lead into the third theme element of the GFL—advancement. Inevitably if there is a high (or low) level of trust and/or safety, this impacts the organizational realities of women within DEPA and MT DEQ. Recall, the MT DEQ and DEPA do have some women at the top of the organizational hierarchy. Specifically, out of the five high level positions within the DEPA, three are women (Ministry of Environment & Food of Denmark, Citation2020b). This may appear to be progress for DEPA, but we cannot forget that hierarchical organizations are layered. The vast majority of MT DEQ top-level positions (e.g. director’s office or bureau chiefs) are occupied by men (Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Citation2020b).

We cannot forget the lived experiences of the front-line regulators studied here are also defined by their hierarchical structures, which can mask the organizational realities of women (Acker, Citation1992). In closing each interview segment, participants were invited to share thoughts they would like to be known that were not previously discussed in conversations. In 90 percent of the interviews, participants sought to offer solutions for what they defined as the organizational advancement problem for women. In both agencies, male and female participants recognized the shortage of women in upper-level management positions. Simply put, “advancement” is used to categorize participant observations or awareness of their organization’s promotion or progress (or lack thereof) to advance women in regulation.

DEPA respondents ardently stressed their country’s role since World War II was to advance the role of women in their society. As one interviewee argued, “After the War, more women went to work and kept our economy going.” Another person suggested, “It would be really rare to see a Danish housewife today.” However, when pressed about the role of women within their respective agency, the consensus was, “gender is quite equal for their work.” Yet, women still do not maintain positions within top levels of DEPA. Several respondents noted this is because there is still a shift underway from the “old to new Denmark.” Women still dominate traditional roles (e.g. teachers, nurses), and as more women pursue degrees in law and education, their belief is that progress will be made in filling higher level positions with DEPA by women. Sentiments celebrating gender equality are positive, but Arora-Jonnson (Citation2009) remind us of, “a line of feminist arguments that claims that the emphasis on gender equality has shifted attention from the real problem, that is, discrimination against women” (217).

MT DEQ respondents defined advancement for the role of women through the lens of progress and persistence. For example, one interviewee stated, “Most professional men now yield respect for females in our organization. It is a good time for gender in the workplace because of the respect that woman have earned and what they bring to the table—our different tactics and approaches.” Another respondent noted, “We [women] have been fighting since the 1970s. We cannot give up now.” Nonetheless, interview participants stressed the organization has changed over time, but more work is necessary due to persistent gender stereotypes and the absence of women (Acker, Citation1992).

By way of summary, we suggest each element in the GFL is interconnected, illustrating what women (and their male counterparts) define as their lived experiences on the front-lines of environmental regulation with the MT DEQ and DEPA. The three elements of the GFL framework capture the collective storylines of 25 participants from the MT DEQ and DEPA. Inevitably, barriers are present for women on the front-lines of regulation because our public sector organizations and those that occupy them bring gender biases due to societal normalizations (Nielsen, Citation2015).

Most apparently, participants recognized can be treated differently in their role as environmental regulators, positing tangible solutions to address obstacles. The safety experiences shared by MT DEQ participants may sound the alarm. To address these concerns, the agency (MT DEQ) has a database to track problematic site visits because women and their male allies continue to share and record experiences. A tracking system is used to identify difficult facilities, flagging as a multi-site inspection where more than one person is present to conduct a site visit.

Moreover, the GFL pushes us to consider broader questions about the democratic nature of regulatory policy. The MT DEQ and DEPA hierarchical structures continue to perpetuate what Acker (Citation1992), almost thirty years ago, coined as gendered institutions burdened by gendered stereotypes. Women lack representation in high-level positions in both agencies, resembling passive representation (Keiser et al., Citation2002) perpetuated by gendered norms and societal stereotypes (Pederson and Nielsen, 2019). In order to make significant strides, MT DEQ participants posit mentorship and supervisors who present future opportunities for women are essential for success. Mid-level managers interviewed from the MT DEQ identified the desire to create a formal mentorship program to assist in the advancement of women.

Additionally, interview participants suggested more women were moving into mid-level positions and as a result, day-to-day interactions and policy decisions are changing. For many, men are serving as allies or as one person defined, “supervisors that act” to advance the role of women within the organization. In turn, the role of women on the front-lines of environmental policy implementation, according to an interviewee, “Offers insight often missing in conversations and interpretation of the law.” Nevertheless, “no one makes it to top positions without substantial assists, whether active or passive” (Hilton & O’Leary, Citation2018, p. 6).

DEPA participants consistently pointed to shifts in outward, societal norms, affording women equal opportunity. Their organization has “made a concerted effort to pay women for equal work,” but has some “work to do to do in moving women into higher level positions,” according to an upper-level management participant. Many claimed the work of the Ministry of Gender Equality continues to promote policies to ensure gender equality across Denmark. However, Arrora-Jonnson’s work (2009) stresses gender research, regardless of progress, must continue. If not, “Gender to become a technocratic measure, resulting in its depoliticization as it turned into a matter of monitoring and planning, rather than struggle” (Arrora-Jonnson, 2009, 220).

Conclusion and future research

A variety of important implications arise from this exploratory study focused on the role of women on the front-lines of environmental regulation. The barriers identified in this project should not go unnoticed and offer several important implications. For example, much like Arora-Jonsson (Citation2014), the research here calls attention to highlighting the role of gender in the implementation of environmental policy. Simply put, if we do not investigate the role of gender in how we implement environmental regulations through a comparative lens then conversations about women’s unequal positions in policy work will not occur.

Another implication from this work points to the front-lines of environmental regulation as a critical area of research for environmental policy and public administration scholars. The vast majority of environmental regulation is implemented on the front-lines of policy. The research here reveals some of the organizational realities of women within these roles. The collective female voices in this study described their organizational structure as something to “tackle,” or “keep fighting.” We argue broader systems in place continue to pose constraints for women in regulation. The hierarchical structure of the MT DEQ and DEPA or the command and control system they implement does present challenges. However, Hilton and O’Leary (Citation2018) offer a different perspective. Alternatively, the organizational system could afford opportunities for women to lead in place—“the observed phenomenon of women not making it into top positions of leadership is at least partially a function of how leadership is conceived, recognized, and awarded. Women lead: whether in remunerated roles in the workplace or non-renumerated roles in their communities” (p. 7). This does not mean women could or should not reach top-level positions, but use their current positionality to advance policy solutions.

All too often we approach research through a quantitative lens. We cannot forget the value of qualitative research. Interviews, in this case, are particularly useful for getting the story behind a participants’ experiences (McNamara, Citation1999). Future research could use the same qualitative GFL framework and theoretical components discussed in this paper as a starting point to investigate the role of women in other regulatory agencies, both environmental and otherwise. Such studies could seek to determine if experiences are different than reported in this study.

This investigation is not without its limitations. One glaring shortcoming is that all interview participants were white/Caucasian. These voices do not reveal the observations of racial minorities within their respective organizations. Some of the MT DEQ respondents did, however, suggest much more work is needed in the diversification of their workforce, especially within a state where almost seven percent of the population is Native American (United States Census Bureau, Citation2020).

In summary, understanding the role of gender matters for public sector organizations. The stories of and about women on front-lines of environmental regulation yield significant insight for the fields of public administration and environmental policy. As this paper indicates, we must begin to examine this body of research through a different lens—the role of gender. If we do not, then how can women within professions such as environmental regulation move from lower and mid-level positions to overseeing organizational change, direction, and policy execution? Women should not remain leading in place (Hilton & O’Leary, Citation2018), but be examined to more fully understand compliance solutions for environmental policy in Montana, Denmark, and beyond.

We are only beginning to understand the forces at work here and cannot forget, “Gender equality is regarded as a prerequisite for economic growth, democracy and welfare, and also as the basis for the full enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms in political, economic, social, cultural and civil spheres of life” (Minster of Gender Equality, 2020). Women do shape the successes and failures of environmental policy execution, and it is up to us to share their experiences to understand environmental policy today and tomorrow.

Notes

1 Inspector and regulator are used interchangeably in this paper—both refer to front-line actors responsible for ensuring compliance with environmental policy in their respective country.

2 Questions included: description of inspection process; demographic makeup for role (inspectors and firms); perceived role of gender in their work; perceived treatment in their position; if gender matters in environmental regulations; other insights to offer about their work to date.

References

- Acker, J. (1992). From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions. Contemporary Sociology, 21, 565–569. https://doi.org/10.2307/2075528

- Arora-Jonnson, S. (2009). Discordant connections: Discourses on gender and grassroots activism in two forest communities in India and Sweden. Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 35(1), 213–239.

- Arora-Jonsson, S. (2014). Forty years of gender research and environmental policy: Where do we stand? Women's Studies International Forum, 47(Part B), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.02.009.

- Arora-Jonsson, S., & Agren, M. (2019). Bringing diversity to nature: Politicizing gender, race, and class in environmental organizations. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 2(4), 874–898. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619866381

- Bakan, D. (1966). The Duality of Human Existence. Addison Wesley.

- Bardach, E., & Kagan, R. (2002/1982). Going by the book: The problem of regulatory unreasonableness. Transaction Publishers.

- Braithwaite, J., Walker, J., & Grabosky, P. (1987). An enforcement taxonomy of regulatory agencies. Law & Policy, 9(3), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.1987.tb00414.x

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2020). World factbook: Denmark. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/da.html.

- Cook, J. J. (2018). Framing the debate: How interest groups influence draft rules at the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Policy and Governance, 28(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1801

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among the five approaches. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Crow, D., & Jones, M. (2018). Narratives as tools for policy change. Policy & Politics, 46(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230061022899

- Donnelly, K., Twenge, J. M., Clark, M. A., Shaikh, S. K., Beiler-May, A., & Carter, N. T. (2016). Attitudes toward women’s work and family roles in the United States, 1976–2013. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315590774.

- Equal Pay for Equal Work Task Force. (2020). Equal pay MT. Montana.Gov. https://equalpay.mt.gov/

- Freeman, J. (1984). The tyranny of structurelessnes. In untying the knot: Feminisim, anarchims, and organization. Dark Star/Rebel Press.

- Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Gray, B. (2003). Framing of environmental disputes. In R. Lewicki, B. Gray, & M. Elliot (Eds.), Making sense of intractable environmental conflicts (pp. 34–50). Island Press.

- Hawkins, K. (1984). Environment and enforcement: Regulation and the social definition of pollution. Claredon Press.

- Hilton, R. M., & O’Leary, R. (2018). Leading in place: Leadership through a different lens. Routledge.

- Hutter, B. M. (1997). Compliance: Regulation and environment. Clarendon Press.

- Jones, M. D., Shanahan, E. A., & McBeth, M. K. (Eds). (2014). The science of stories: Applications of the narrative policy framework in public policy analysis. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kamieniecki, S. (2006). Corporate America and environmental policy: How often does business get its way? Stanford Law and Politics.

- Keiser, L., Wilkins, V., Meier, K., & Holland, C. (2002). Lipstick and logarithms: Gender, institutional context, and representative bureaucracy. American Political Science Review, 96(3), 553–563. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055402000321

- Kumar, R. (2005). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide. Sage Publications.

- Lewicki, R., Gray, B., & Elliott, M. (2003). Making sense of environmental conflicts: Concepts and cases. Island Press.

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Mastracci, S., & Bowman, L. (2015). Public agencies, gendered organizations: The future of gender studies in public management. Public Management Review, 17(6), 857–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.867067

- May, P., & Winter, S. (2000). Reconsidering styles of regulatory enforcement: Patterns in Danish agro-environmental inspection. Law & Policy, 22(2), 143–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9930.00089

- Maynard-Moody, S., & Musheno, M. (2003). Cops, teachers, counselors: Stories from the front lines of public service. University of Michigan Press.

- McNamara, C. (1999). General guidelines for conducting interviews. Free Management Library. https://managementhelp.org/businessresearch/interviews.html.

- Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark. (2020a). The Danish Environmental Protection Agency. https://eng.mst.dk/

- Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark. (2020b). Organisation. Danish Environmental Protection Agency. https://eng.mst.dk/about-us/organisation/.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. (2020). Gender Equality. https://um.dk/en/gender-equality/

- Elmagrhi, M. H., Ntim, C., Elamer, A., & Zhang, Q. (2019). A study of environmental policies and regulations, governance: structures, and environmental performance: The role of female directors. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(1), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2250

- Montana Department of Environmental Quality. (2020a). Organizational structure. https://deq.mt.gov/DEQAdmin/about/orgchart.

- Montana Department of Environmental Quality. (2020b). Department of Environmental Quality Directory. https://directory.mt.gov/govt/state-dir/agency/deq.

- Nielsen, V. L. (2006). Are street level bureaucrats compelled or enticed to cope? Public Administration, 84(4), 861–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00616.x.

- Nielsen, V. L. (2015). Personal attributes and institutions: Gender and the behavior of public employees. Why gender matters to not only gendered policy areas. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(4), 1005–1029. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu019

- Nisbet, M. C. (2010). Knowledge into action: Framing the debates over climate change and poverty. In Paul D’Angelo & Jim A. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 43–83). Routledge.

- Pautz, M. (2009). Trust between regulators and the regulated: A case study of environmental inspectors and facility personnel in Virginia. Politics & Policy, 37(5), 1047–1072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2009.00210.x

- Pautz, M. C., & Rinfret, S. R. (2013). The lilliputians of environmental regulation: The perspective of state regulators. Routledge.

- Pautz, M. C., & Wamsley, C. S. (2012). Pursuing trust in environmental regulatory interactions: The significance of inspectors’ interactions with the regulated community. Political Science Faculty Publications, 9.

- Pautz, M., & Rinfret, S. (2016). State environmental regulators: Perspectives about trust with their regulatory counterparts. Journal of Public Affairs, 16(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1558.

- Riccucci, N. M. (2005). How management matters: Street-level bureaucrats and welfare reform. Georgetown University Press.

- Rinfret, S. R. (2011). Behind the shadows: Interest groups and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 16(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2011.536910

- Rinfret, S., & Pautz, M. (2019). Environmental policy in action. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Rosenbloom, D. (1977). Federal equal employment opportunity: Politics and public personnel administration. Praeger.

- Selden, S. C. (1997). The promise of representative bureaucracy: Diversity and responsiveness in a government agency. ME Sharpe.

- Smith, A. (2014). Getting to the helm: Women in leadership in federal regulation. Public Organization Review, 14(4), 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-013-0240-0

- Sneed, B. (2007). Glass walls in state bureaucracies: Examining the difference departmental function can make. Public Administration Review, 67(5), 880–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00775.x

- Stivers, C. (2000). Bureau men, settlement women: Constructing public administration in the progressive era. University of Kansas Press.

- United States Census Bureau. (2020). Montana facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/MT.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications.