Abstract

Background

Children with special educational needs experience limited levels of participation at school; their participation is influenced by the physical and social environment. Interventions that have been applied in school environments are described in the literature.

Aims

To illustrate the main features of interventions targeting school environments to support participation of children with special educational needs in mainstream education.

Materials and methods

A scoping review using a qualitative, thematic analysis was conducted in May 2021.

Results

We included a total of 20 articles. We found that intervention features contributed to children’s participation and targeted social and physical school environments. The majority of the intervention features focussed on applying supportive teaching methods to enable individual children’s participation. A small number of interventions described a systemic holistic approach that involved changes to the school environment. In these interventions, different professionals such as occupational therapists collaborated with teachers to adapt the school environment.

Conclusions and significance

A shift from individual child-focussed to environment-focussed approaches that target all children’s participation could impact classroom setup and teachers’ roles. Occupational therapists’ expertise in matching school environments and task requirements with individual children’s needs could be valuable in their collaboration with schools to support this transition.

Introduction

Children’s education is a fundamental human right [Citation1] that contributes to their social and emotional development [Citation2] and participation [Citation3]. Research has emphasised the importance of school participation on children’s development and well-being [Citation4,Citation5], as it supports the development of skills, expression of creativity and self-identity and fosters the development of friendships [Citation6,Citation7]. Participation is defined by the World Health Organisation as ‘involvement in a live situation’ [Citation8]. Imms et al. [Citation9] added two essential elements to this definition: attendance (e.g. how often does the child conduct, for example, a writing activity) and involvement (e.g. how involved the child is in the writing activity). Attendance, as well as involvement, is seen as an essential aspect of experiencing participation. In the Netherlands, more than 1.5 million children (4–12 years) attend school during weekdays; of these, about 25% require extra support to be able to participate in daily education [Citation10]. However, numerous studies have indicated that participation at school for children with special educational needs (SEN) remains limited in comparison to their peers without disabilities [Citation11–14].

Children with SEN are defined as ‘children who, for a wide variety of reasons, require additional support and adaptive pedagogical methods in order to participate and meet learning objectives in an educational programme. Reasons may include (but are not limited to) disadvantages in physical, behavioural, intellectual, emotional and social capacities’ [Citation15]. Previous research has indicated that children with SEN might experience problems with peer acceptance [Citation16], have fewer social contacts [Citation17], perceive more environmental barriers [Citation18] and are more dependent on adults than their peers without a disability [Citation19]. Furthermore, these children rated their interaction with peers and adults as lower than that of their peers [Citation16].

For a number of years, schools have been obligated to provide children with SEN the opportunity to participate in mainstream education. For instance in the Netherlands, a new law aimed at inclusive education was introduced in August 2014 [Citation20]. The process of adapting schools, classrooms and activities so all children can learn and participate together is internationally described by the term ‘inclusive education’ [Citation21,Citation22]. Further to this, research has demonstrated that a majority of Dutch teachers favour inclusive education [Citation23]. However, teachers experience a high workload and tend to lack the skills and knowledge to effectively support the diversity of children with SEN in the classroom [Citation24]. Therefore, Dutch teachers have emphasised the need to develop a repertoire of practical skills and knowledge for applying inclusive approaches in their daily teaching routines [Citation25]. Moreover, Pijl [Citation26] underlined the importance of providing opportunities for teachers to acquire this repertoire of skills on the job by working in teams. In these teams, teachers collaborate with outside professionals within the school environment to learn from each other in formal and informal ways [Citation27,Citation28].

Occupational therapists have started to play a growing role in supporting the inclusion of children with SEN at school [Citation29], as they are experts in matching school environments and task requirements with the needs of children who experience restrictions in their participation [Citation30]. The American Occupational Therapy Association has identified education as a key performance area for occupational therapists who work with children [Citation31]. Recent studies have demonstrated the relationship between environmental factors and the level of school participation for children with SEN [Citation32–34]. Bronfenbrenner [Citation35] subdivided the school environment into different levels, each of which influenced children’s development and participation at school. These levels are defined as the micro-, meso-, exo- and macro-environment. The level which is closest to the child is called the micro-environment. The micro-environment encompasses the relationships, interactions and structures a child has in their immediate surrounding; as a consequence, the micro-environment directly influences children’s participation at school. Besides identifying the levels, Bronfenbrenner [Citation35] also distinguished between the physical environment (e.g. classroom, furniture, learning materials) and the social environment (e.g. peers, teachers, parents) in each level. Interactions in the microsystem have the most powerful influence on a child’s engagement in school activities and their overall participation [Citation36–38]; therefore, this study primarily focuses on children’s microsystems, which are divided into their social and physical school environments.

Despite scientific insight into the importance of the environment in enabling participation, many educational support programmes still focus on the training of individual children (e.g. training to improve their social skills [Citation39] or motor skills [Citation40] without consideration of environmental factors). A recent study [Citation41] has shown that rather than focussing on adapting the school environment, a majority of occupational therapists working with children with SEN still use pull-out approaches with individual children to primarily address sensory, hand function or daily living needs. Literature has recently emphasised a shift in occupational therapy interventions from traditional pull-out approaches (individual interventions) to holistic approaches that are integrated into the student’s classroom [Citation42] and focus on the social and physical school environment [Citation29]. Consequently, interventions that aim to enhance participation of children with SEN must focus on individual factors, on the nature of the participation activity and on factors in the environment in which the activity is being performed [Citation43]. For example, a Swiss study found that occupational therapists reported a need to primarily experience the educational, social and physical school environment in order to understand its impact on a child’s participation [Citation44].

To our knowledge, little is yet known about existing school-based interventions that aim to enable school participation and focus on changing or enabling the school environment. School-based interventions have been defined as approaches that are integrated in the natural school context in collaboration with different stakeholders, including occupational therapists [Citation29]. Therefore, mapping current interventions could shed light on this gap and help to identify the main features of school-based interventions that focus on the school environment. Such a synthesis could support future research on the enhancement of participation of children with SEN at school and the possible role of experts (e.g. occupational therapists). For this reason, we conducted a scoping review with a focus on the following research question: ‘What is known in the literature about the main features of interventions that target the school environment to enable the participation of children with SEN in mainstream education?’

Methods

Scoping reviews

For this scoping review, we applied Arksey and O’Malley’s [Citation45] methodological framework. Therefore, the research team followed the following five main stages: (1) identify the research question, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) select studies, (4) chart the data and (5) collate, summarise and report the results. The method of a scoping review is chosen in order to identify gaps in the literature of existing interventions not limited to interventions (already) proven to be effective or studies that meet the criteria of a quality assessment [Citation46]. Therefore, our use of a scoping review method will not necessarily identify research gaps if the research itself is of poor quality. We chose the most recent decade as the rational time period for this work.

Search terms and search strategies

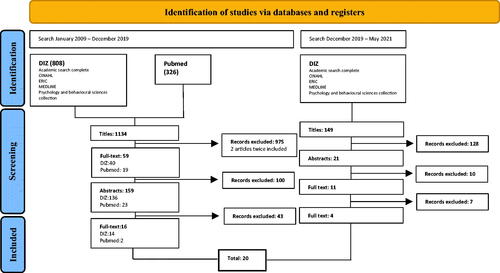

This scoping review focuses on interventions that change the school environment to enable the participation of children with SEN within mainstream education. Therefore, we applied a search strategy that used the following formula: ‘participation’ AND ‘children’ AND ‘environment’ AND ‘special educational needs’ AND ‘mainstream education’ AND ‘intervention’. Each search term was linked to several MeSH terms. Search terms for ‘participation’ included ‘engagement’ and ‘inclusion’ or ‘involvement’. Search terms for ‘children’ included the MeSH terms ‘kids’, ‘youth’, ‘child’ or ‘pupil’. MeSH terms focussing on the search term ‘environment’ included ‘contextual’, ‘context’, ‘environmental’, ‘context-based’ or ‘school-based’, while ‘special educational needs’ MeSH terms included ‘special needs’, ‘impairment’, ‘limited’, ‘disability’, ‘disabled’ or ‘disabilities’. Search terms for ‘mainstream education’ included ‘elementary school’, ‘primary education’, ‘elementary education’ or ‘primary school’ MeSH terms. Finally, we also used the ‘intervention’ MeSH terms ‘approach’ and ‘program’. We searched via the ‘Zuyd Discovery Service’ (DIZ), that included ‘Academic Search Complete’, ‘Cinahl’, ‘ERIC’, ‘Medline’, ‘Psychology & Behavioural Sciences Collection’ databases, and via ‘PubMed’ for the first time at the end of June 2019 (24/6/19). The articles that were searched were published between January 2009 and December 2019. We then conducted a second search to include recent literature that had been published between December 2019 and May 2021.

Study selection

Study selection criteria were identified in several stages of the study review, and we did not impose restrictions regarding the type of design. The study languages were limited to English, German and Dutch. Studies were included if they (a) provided information about a school-based intervention, (b) focussed on adapting, changing or using the school environment, (c) targeted primary school children (between the ages of 4 and 12), (d) targeted children with a special (educational) need (not necessarily referring to a diagnosis) and (e) aimed to enhance school participation or any related concept of school participation. Studies were excluded if (a) services were offered exclusively outside the school environment, (b) interventions were provided only in special school settings or (c) exclusively focussed on the child’s level of function, such as improving tactile function. Both literature searches were conducted by the first author (SM), while SM and a second reviewer (HS) independently evaluated and scored the results of each stage based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria that have been described above. They recorded their evaluation by labelling each study as either relevant (R), irrelevant (I) or doubtful (D). Any that were rated as D were discussed with additional reviewers (BP, PH and DD; other authors of this article). Finally SM (first author) performed a preliminary full-text analysis.

Charting the data

The data extracting and charting process was developed with input from BP, PH and DD. SM extracted data such as publication year, country, aim of the study, target group and study methodology from the included articles (see ). In addition, detailed information regarding intervention features, main findings and methods for outcome evaluation were extracted and charted using an Excel spreadsheet.

Table 1. Descriptive summary of the relevant studies.

Collating, summarising, and reporting the results

A qualitative thematic analysis [Citation67] regarding intervention features that target the school environment to enable participation of children with SEN was performed on the extracted information. Initial codes were generated, reviewed and collated into potential themes, which we then repetitively reviewed and defined. All of this article’s authors were involved in the process of determining how best to describe the data. The resulting main themes are shown in .

Results

A total of 1283 articles from the ‘DIZ’ and ‘PubMed’ databases were identified as potentially relevant. After screening, 180 abstracts and 70 full-text articles appeared to be relevant. We evaluated all 70 of the articles on a full-text level, which resulted in a final total of 20 articles that were relevant for further analysis (see ).

Descriptive summary of the studies

The majority of the 20 relevant articles that remained after selection criteria was applied had been conducted in the United States, Canada and Australia. All of the articles had been published between 2009 and 2021; thirteen of the articles were quantitative studies, one was a qualitative study, five used a mixed method approach and one used an intervention description (see ).

Narrative summary of the studies

The qualitative thematic analysis resulted in an overview of intervention features organized along two major themes: (1) Changing the social school environment and (2) Changing the physical school environment. In , the intervention strategies are presented in relation to the major themes. Intervention strategies can be applied for an individual child, a group of children and/or the whole class. ‘Individual child’ means intervention strategies applied to support individual children with SEN, ‘group of children’ implies that at least two children of one class are targeted, and ‘whole class’ indicates strategies were applied for all children in one classroom.

Table 2. Overview of themes.

Changing the social school environment to support children’s participation

This theme is about changing the social school environment to support children’s participation. In this scoping review, ‘changing’ refers to modifying the knowledge, ideas, strategies and approaches of the school team and/or individual school personnel to enable children’s participation at school. This first main theme is distributed in five subthemes, each of which describes one of the emerged intervention features.

Applying supportive teaching approaches

A total of fifteen interventions incorporated features of applying supportive teaching approaches. Here, an approach is defined as a vision and use of teaching and learning strategies in the classroom situation. The description of supportive teaching approaches in the research varied between more general descriptions of frameworks to specific examples. The supportive teaching approach known as ‘Response to Intervention’ refers to designing teaching environments to foster skills development in all children. Within this approach, teachers were additionally supported to use differentiated instructions for groups of children and to apply accommodations for individual students [Citation55,Citation57]. Trussell et al. [Citation62] evaluated ‘Universal Design for Learning’ teaching strategies that were applied for all children in the classroom, whereas Abawi et al. [Citation47] described an approach in which support is matched to children’s individual needs. Narozanick et al. [Citation58], however, gave a more specific example of an intervention in which teachers were trained to use ‘class passes’ (visual cards) as an approach for improving classroom behaviour among children with disruptive behaviour. In this approach, children have the option of using their class pass to take an additional break during classroom activities when they need it. In line with this, Wagner et al. [Citation65] trained teachers to implement the Alert Program® – originally developed by occupational therapists – to enhance the self-regulation skills of all children. In Selaniko et al.’s [Citation50] study, training provided by occupational therapists enhanced the whole school team’s knowledge and collaboration in order to provide children with more choices during curriculum activities. Panaerai et al. [Citation59] and Strain et al. [Citation61], meanwhile, supported teachers’ use of alternative communication methods (e.g. implementation of visual schedules) instead of verbal or written information for individual children with autism. Furthermore, during the TEACCH intervention [Citation59], teachers applied differentiated, alternative communication methods during education (e.g. additional visual instructions). Approaches targeting individual children who experience SEN in one classroom [Citation47,Citation48,Citation54,Citation59–62] were found to be the most prominent, followed by groups of children [Citation50,Citation58] and the whole class [Citation51,Citation65,Citation66]. Three interventions stood out as they targeted children on all three levels [Citation53,Citation55,Citation57].

Promoting home to school collaboration

Five of the intervention studies described the feature of facilitating collaboration between parents and teachers [Citation54–57,Citation59]. One strategy used parent–teacher training to provide information about the value of visual support for individual children at home and in the classroom [Citation54,Citation56]. Visuals that addressed goals of an individual child were chosen in collaboration with the parents. Further strategies regarding collaboration were described in the ‘Partnering for Change’ (P4C) [Citation57] intervention, in which an occupational therapist supported the exchange between parents and teachers to support individual children’s school participation. In TEACCH [Citation59], the parents are recognized as the experts on their own child; for this approach they collaborated with the teacher at school and were given the role of co-therapist. Strategies to promote home to school collaboration were always applied to support participation of an individual child [Citation54–57,Citation59].

Adding curriculum activities

Adding curriculum activities means that an ‘additional programme’ is implemented over and above routine teaching activities. In the inclusive school-based resilience intervention ‘Success and Dyslexia’, teachers implemented a ‘universal coping programme’ during the education of all of the children in the class [Citation53]. This intervention offers activities for children with dyslexia, and those children could also participate in additional withdrawal sessions with regard to a dyslexia-related goal. During the ‘Superheroes Social Skills’ intervention [Citation60], a school personnel offered weekly training outside of regular curriculum activities for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). This training incorporated several evidence-based strategies (e.g. inclusion of typically-developing peers, self-monitoring procedures). Fillippatou et al. [Citation52], Cassiere et al. [Citation49] and Wagner et al. [Citation65] trained teachers to implement an additional teaching approach (e.g. disability awareness training) within their own curriculum for all of their students that was aimed at enabling group work, academic performance and motivation [Citation52], improving self-regulation [Citation65] or enhancing disability awareness [Citation67]. Only Nota [Citation63] evaluated imbedded modules for all children for enhancing disability awareness, which was carried out by an independent psychologist. In all of the four included interventions, school personnel were trained beforehand to apply these additional programmes. In line with the previous subthemes, curriculum activities are most often applied to support an individual child [Citation49,Citation52,Citation60], and only the school-based resilience intervention [Citation53] integrated elements for all three levels.

Educating about special needs topics

The term ‘education’ in the context of this study refers to the activity of teaching something to someone. In practice, this refers to new information that is delivered to one or more recipients who are in turn responsible for transferring that knowledge into their own classroom practices. A total of three interventions [Citation48,Citation50,Citation53] described features intended to educate school personnel about the needs of and possible support strategies for children with SEN. For example, the Success and Dyslexia program delivers information about dyslexia to the whole school team as a part of their professional development [Citation53]. Two other interventions contained strategies in which some teachers were educated by speech therapists or occupational therapists regarding social engagement in children with ASD [Citation48] or children with intellectual and developmental disabilities [Citation50]. These educational sessions were implemented as additional training outside of regular teaching activities and targeted at least two teachers at the same time. As this subtheme is related to children’s diagnoses, these intervention features were focussed on the group of children level.

Creating a shared vision

The creation of a shared vision of inclusion for the entire school team was encouraged in three of the interventions [Citation47,Citation51,Citation55], though their main emphasis varied. For instance, Crosskey [Citation51] focussed on building a communication-friendly school environment (e.g. written instructions presented in differentiated ways) that is supported by language specialists. A pedagogical understanding shared by the entire school team [Citation47] and school-wide usage of inclusive teaching strategies [Citation55] are enhanced by the establishment of engagement protocols in addition to training and collaboration with stakeholders (e.g. special education teachers, parents). As the vision of the whole school team is encouraged, all strategies within this subtheme are related to the whole class level.

Changing the physical school environment to support children’s participation

This second main theme addresses intervention features that describe how the physical school environment could be changed in order to enhance participation of children with SEN. In this study, the physical school environment is defined as spaces in which school activities take place and objects (either fabricated or naturally occurring) that are present at school. In line with this definition, the theme is divided in two subthemes.

Using supportive tools

Eight of the interventions described the use of supportive tools during classroom routines. The majority of the interventions made use of visual aids which were printed, laminated and provided to the child in appropriate ways. For example, visual cards [Citation51,Citation54,Citation64] or visual schedules and work systems [Citation59] that keep students informed about the requirements of activities that must be done could be implemented. Other examples include written expectations used to remind a student of an individual goal [Citation61] or a reward system [Citation56,Citation61]. Additionally, daily report cards were suggested as supportive tools for enhancing collaboration between school and home [Citation56]; the use of class passes [Citation58] that can serve as visual signals for students who may need a break was also suggested. Vazou et al. [Citation66] evaluated a web-based plenary learning programme that combined physical activity or exercise with school tasks. Most of the supportive tools focussed on the individual child [Citation54,Citation56,Citation59,Citation60,Citation64].

Changing classroom arrangements

Classroom arrangements refer to the setup of classroom furniture (e.g. chairs and tables, [smart] board, shelves, etc.) or study areas. Two interventions focussed on changing classroom arrangements [Citation57,Citation59]. Panerai et al. [Citation59] explained environmental adaptations that address the layout or setup of the teaching and studying area. During the P4C intervention [Citation57], teachers, with the help of occupational therapists, arranged their classrooms in ways that supported successful learning and restricted distraction possibilities. As the classroom is used by all children, all of the features within this subtheme are related to the whole class level.

Discussion

This scoping review explores the main features of school-based interventions that target the school environment for primary school children. Our results show that intervention features generally target the individual child, a group of children and/or a whole class. Furthermore, to enable participation of various target groups, intervention features could be divided into those that focus on changing the social environment or those that focus on intervening on the physical school environment. This review demonstrates that the majority of the interventions described in the literature have focussed on individual children. Only one intervention, the Partnering for Change approach [Citation57], included all three of the target groups and focussed on adapting both the physical and the social school environment. Teachers collaborated with occupational therapists from outside the school within the school environment to learn from (and with) each other about how to support children’s participation within the classroom setting. Support for teachers from other experts within the classroom setting was one of the most common principles used to deliver school-based services for children with disabilities [Citation68]. The literature also underlined the importance of focussing on teachers’ competencies [Citation69,Citation70]. Our results revealed that teachers applied supportive teaching methods in eleven out of the sixteen studies that were included in this work. Some examples of these methods described in literature include the Response to Intervention approach [Citation71], Universal Design for Learning [Citation72], tailored strategies [Citation73] and the use of alternative communication and information [Citation74]. The promotion of home to school collaboration was presented as the second strategy. Moreover, recent studies [e.g. Citation75] confirmed the effectiveness of collaboration between professionals (e.g. occupational therapists and teachers) and families for supporting children with SEN at school.

The results of this scoping review indicate that changes to the physical school environment must be implemented through the collaboration of teachers and other experts who are committed to learning from and with each other (e.g. special education teachers or speech therapists) within the school environment [Citation47,Citation49–51,Citation54,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation63]. In several of the studies included in this work, occupational therapists, as experts on environmental influences on participation, collaborated with teachers [Citation49,Citation50,Citation54,Citation57]. The importance of interventions that focus on the social environment rather than just the physical school environment has been confirmed by other studies [e.g. Citation68,Citation76] that reveal that collaboration between teachers and occupational therapists is beneficial and valuable to children’s participation [Citation71,Citation72]. However, most of the studies did not emphasize collaboration, but rather interventions performed by teachers. Strategies emerged that were related to the physical school environment; these were shown to be strengthened by others’ studies. These strategies focussed on the adaptation of furniture (e.g. into dynamic furniture) [Citation77], classroom design [Citation78] and the use of supportive tools as visuals [Citation79]. However, it is remarkable that the use of technology as a supportive tool as described by Roschelle et al. [Citation80] was not identified in the interventions included in this review, with the exception of two examples of studies in which computer-based applications were used [Citation60,Citation66]; these were perceived to enhance children’s active engagement and participation in groups.

This scoping review reveals that overall, intervention strategies were applied for individual children with SEN in the classroom. Only a small number of interventions [Citation52,Citation55,Citation56] served children on all three levels (i.e. individual child, group of children and the whole class). Recent studies in education and health sciences have indicated that individual practices are well-known and commonly documented principles for organizing and delivering school-based services for children with disabilities both within the classroom [Citation81] and outside the classroom [Citation82]. In contrast to this, however, recent studies have encouraged the use of ‘Universal Designs for Learning’ interventions to effectively promote all children’s school participation [e.g. Citation83]. Recent work has also supported the use of Response to Intervention tiers [e.g. Citation84,Citation85]. Response to Intervention consists of three tiers [Citation86]; at each tier, strategies are applied to enhance children’s participation. The first tier includes strategies that are implemented for all children in the classroom, the second tier encompasses interventions in addition to classroom instructions that are provided in a small group – these may take place in a separate location – and the third tier consists of additional support provided to individual children.

The literature indicates a trend towards school-based interventions that focus on more than one strategy for enhancing classroom participation [Citation70], focus on the physical as well as the social environment [Citation77] and not only target children that already experience SEN but also proactively target individual children, groups of children and the whole class [Citation77]. In this scoping review, one intervention, P4C [Citation57], stood out, as it integrates intervention features that target both the social and physical environments as well as children on all three levels.

It is interesting to note that this scoping review also revealed a small number of interventions that described a more systemic, holistic approach to serving the needs of more than one individual child. To evaluate their effectiveness on children’s participation at school, more focus is needed on exploring the benefits of these systemic, holistic approaches in inclusive education. Future interventions must balance the level at which children should be targeted and address a combination of several target groups; they must also focus on changing and using both the social and physical school environments. A shift from an individual child-focussed approach to an environment-based approach that targets the participation of all children will have a major impact on the role of teachers as well as classroom setup. In line with our findings, these changes will also have an impact on the education and work of health care professionals who work in the school context. The implication of this for health care professionals is that they are taking on a role as an enabling expert and collaborator rather than just a practitioner who intervenes with those in need of a treatment. In other words, teachers and occupational therapists become partners in co-designing strategies to optimize the school environment. Occupational therapists are experts in enabling participation through analysing the interaction of a child, their occupation and their environment. Therefore, their expertise can provide valuable insight when collaborating with schools to support this transition.

Methodological considerations and limitations

The results of this study may be hampered by some limitations. First, we may have missed studies due to database selection bias. This scoping review focussed solely on elementary students and mainstream education; therefore, studies that evaluated or described school-based interventions that have been implemented in other educational contexts were not considered. Furthermore, there is a minor possibility that some studies were missed, as the search was limited to the database search results – we did not conduct extensive manual searching. Non-English studies may also have been overlooked as most of the reported studies were conducted in Canada and the US.

The findings of this study might also portray a limited picture of school-based strategies, as most studies were conducted in Western societies such as the United States and Canada. The first (SM) and second (BP) authors have held an interest in school-based occupational therapy for some years, which might have led to the development of preconceived notions that may have influenced the interpretation of the data. However, discussions with the other members of the research team are likely to have reduced this bias.

Acknowledgements

This articles refers to the first study of the PhD-project of the first author.

Disclosure statement

Herewith the authors of this article vouch for the accuracy of the manuscript according to the guidelines given by the Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. The material or parts of the material have not been published elsewhere.

The topic of the proposed review has been discussed with the Editor-in-Chief before submission and approval was obtained.

Additional information

Funding

References

- UNESCO. Policy guidelines on inclusion in education. Paris: UNESCO; 2009.

- Miyamoto K, Huerta MC, Kubacka K. Fostering social and emotional skills for well‐being and social progress. Eur J Educ. 2015;50:147–159.

- Koster M, Pijl SJ, Nakken H, et al. Social participation of students with special needs in regular primary education in The Netherlands. Intern J Disabil Dev Educ. 2010;57:59–75.

- Griebler U, Rojatz D, Simovska V, et al. Effects of student participation in school health promotion: a systematic review. Health Promot Int. 2017;32:195–206.

- Jose PE, Ryan N, Pryor J. Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well‐being in adolescence over time? J Res Adolesc. 2012;22:235–251.

- Simovska V, Jensen BB. Conceptualizing participation: the health of children and young people. Brussels: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2009.

- Petrenchik TM, King GA. Pathways to positive development: childhood participation in everyday places and activities. In Bazyk S, editor. Mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention in children and youth: a guiding framework for occupational therapy. North Bethesda (MD): AOTA Press; 2011. p. 71–94.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:16–25.

- Ledoux G, Waslander S, Eimers T. Evaluatie passend onderwijs Eindrapport. Amsterdam: Kohnstamm Instituut; 2020.

- Piskur B. Parents’ role in enabling the participation of their child with a physical disability: actions, challenges and needs. Maastricht: Datawyse/Universitaire Pers Maastricht; 2015.

- Schwab S. Friendship stability among students with and without special educational needs. Educ Stud. 2019;45:390–401.

- McCoy S, Banks J. Simply academic? Why children with special educational needs don’t like school. Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2012;27:81–97.

- Bossaert G, de Boer AA, Frostad P, et al. Social participation of students with special educational needs in different educational systems. Ir Educ Stud. 2015;34:43–54.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. International standard classification of education: ISCED 2011. Montreal (QC): UNESCO-UIS; 2012.

- Pinto C, Baines E, Bakopoulou I. The peer relations of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream primary schools: the importance of meaningful contact and interaction with peers. Br J Educ Psychol. 2019;89:818–837.

- Avramidis E, Avgeri G, Strogilos V. Social participation and friendship quality of students with special educational needs in regular Greek primary schools. Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2018;33:221–234.

- Guichard S, Grande C. Differences between pre-school children with and without special educational needs functioning, participation, and environmental barriers at home and in community settings: an international classification of functioning, disability, and health for children and youth approach. Front Educ. 2018;3:7.

- Sadownik A. Belonging and participation at stake. Polish migrant children about (mis) recognition of their needs in Norwegian ECECs. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. 2018;26:956–971.

- Rijksoverheid [Internet]. The Netherlands: Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap; [cited 2022 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/passend-onderwijs

- Inclusive education – Including children with disabilities in quality learning: what needs to be done? [Internet]. Europe: UNICEF; 2017 [cited 2020 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/IE_summary_accessible_220917_brief.pdf

- Armstrong AC, Armstrong D, Spandagou I. Inclusive education: international policy & practice. California: SAGE; 2009.

- Cusiël N. Onderzoek naar de attitude en competentiebeleving van leerkrachten in het regulier onderwijs ten aanzien van passend onderwijs [research about attitude and perceived competence of teachers in general education concerning inclusive education]. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen; 2010.

- Leinonen J, Brotherus A, Venninen T. Children’s participation in Finnish pre-school education-identifying, describing and documenting children’s participation. Nord Early Child Educ Research. 2014;7:1–16.

- Deunk MI, Doolaard S, Smalle-Jacobse A, et al. Differentiation within and across classrooms: a systematic review of studies into the cognitive effects of differentiation practices. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen: GION onderwijs/onderzoek; 2015.

- Pijl SJ. Preparing teachers for inclusive education: some reflections from The Netherlands. J of Research in Spec Educ Needs. 2010;10:197–201.

- Richter D, Kunter M, Klusmann U, et al. Professional development across the teaching career: teachers’ uptake of formal and informal learning opportunities. Teach Prof Dev. 2011;27:116–126.

- Borg E, Drange I. Interprofessional collaboration in school: effects on teaching and learning. Improv Sch. 2019;22:251–266.

- Cahill SM, Bazyk S. School-based occupational therapy. In Clifford O’Brien J, Kuhaneck H, editors. Case-Smith’s occupational therapy for children and adolescents. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier; 2020. p. 627–658.

- Case-Smith J, O’Brien JC. Occupational therapy for children and adolescents. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier; 2014.

- Boop C, Cahill SM, Davis C, et al. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process fourth edition. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74:1–85.

- Egilson ST, Jakobsdóttir G, Ólafsson K, et al. Community participation and environment of children with and without autism spectrum disorder: parent perspectives. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:187–196.

- Anaby D, Hand C, Bradley L, et al. The effect of the environment on participation of children and youth with disabilities: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1589–1598.

- Egilson ST, Traustadottir R. Assistance to pupils with physical disabilities in regular schools: promoting inclusion or creating dependency? Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2009;24:21–36.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development. Intern Encycl Educ. 1994;3:37–43.

- Izadi-Najafabadi S, Ryan N, Ghafooripoor G, et al. Participation of children with developmental coordination disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;84:75–84.

- Piškur B, Meuser S, Jongmans AJHM, et al. The lived experience of parents enabling participation of their child with a physical disability at home, at school and in the community. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:803–812.

- Härkönen U. The Bronfenbrenner ecological systems theory of human development. Joensuu: University of Joensuu; 2001.

- Camargo SPH, Rispoli M, Ganz J, et al. A review of the quality of behaviorally-based intervention research to improve social interaction skills of children with ASD in inclusive settings. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44:2096–2116.

- Farhat F, Hsairi I, Baati H, et al. The effect of a motor skills training programme in the improvement of practiced and non-practiced tasks performance in children with developmental coordination disorder (DCD). Hum Mov Sci. 2016;46:10–22.

- O’Donoghue C, O’Leary J, Lynch H. Occupational therapy services in school-based practice: a pediatric occupational therapy perspective from Ireland. Occup Ther Intern. 2021;2021:1–11.

- Bazyk S, Michaud P, Goodman G, et al. Integrating occupational therapy services in a kindergarten curriculum: a look at the outcomes. Am J Occup Ther. 2009;63:160–171.

- Novak I, Honan I. Effectiveness of paediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019;66:258–273.

- Kaelin V, Ray-Kaeser S, Moioli S, et al. Occupational therapy practice in mainstream schools: results from an online survey in Switzerland. Occup Ther Intern. 2019;2019:1–9.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Intern J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

- Abawi L, Oliver M. Shared pedagogical understandings: schoolwide inclusion practices supporting learner needs. Improv Schools. 2013;16:159–174.

- Locke J, Kang-Yi C, Pellecchia M, et al. It’s messy but real: a pilot study of the implementation of a social engagement intervention for children with autism in schools. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2019;19:135–144.

- Cassiere AR. Inclusion through infusion: disability awareness training for elementary educators [dissertation]. Boston (MA): Boston University; 2017.

- Selanikyo E, Yalon-Chamovitz S, Weintraub N. Enhancing classroom participation of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Can J Occup Ther. 2017;84:76–86.

- Crosskey L, Vance M. Training teachers to support pupils’ listening in class: an evaluation using pupil questionnaires. Child Lang Teach Ther. 2011;27:165–182.

- Filippatou D, Kaldi S. The effectiveness of project-based learning on pupils with learning difficulties regarding academic performance, group work and motivation. Intern J Spec Educ. 2010;25:17–26.

- Firth N, Frydenberg E, Steeg C, et al. Coping successfully with dyslexia: an initial study of an inclusive school‐based resilience programme. Dyslexia. 2013;19:113–130.

- Foster‐Cohen S, Mirfin‐Veitch B. Evidence for the effectiveness of visual supports in helping children with disabilities access the mainstream primary school curriculum. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2017;17:79–86.

- Mahdavi JN, Beebe-Frankenberger ME. Pioneering RTI systems that work: social validity, collaboration, and context. Teach Except Child. 2009;42:64–72.

- Mautone JA, Marshall SA, Sharman J, et al. Development of a family–school intervention for young children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. School Psych Rev. 2012;41:447–466.

- Missiuna C, Pollock N, Campbell WN, et al. Use of the medical research council framework to develop a complex intervention in pediatric occupational therapy: assessing feasibility. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:1443–1452.

- Narozanick T, Blair KSC. Evaluation of the class pass intervention: an application to improve classroom behavior in children with disabilities. J of Pos Behav Interv. 2019;21:159–170.

- Panerai S, Zingale M, Trubia G, et al. Special education versus inclusive education: the role of the TEACCH program. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:874–882.

- Radley KC, McHugh MB, Taber T, et al. School-based social skills training for children with autism spectrum disorder. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2017;32:256–268.

- Strain PS, Wilson K, Dunlap G. Prevent-teach-reinforce: addressing problem behaviors of students with autism in general education classrooms. Behav Disord. 2011;36:160–171.

- Trussell RP, Lewis TJ, Raynor C. The impact of universal teacher practices and function-based behavior interventions on the rates of problem behaviors among at-risk students. Educ Treat Child. 2016;39:261–282.

- Nota L, Ginevra MC, Soresi S. School inclusion of children with intellectual disability: an intervention program. J Intel & Dev Dis. 2019;44:439–446.

- Zimmerman KN, Ledford JR, Gagnon KL, et al. Social stories and visual supports interventions for students at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Beh Dis. 2020;45:207–223.

- Wagner B, Latimer J, Adams E, et al. School-based intervention to address self-regulation and executive functioning in children attending primary schools in remote Australian aboriginal communities. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234895.

- Vazou S, Long K, Lakes KD, et al. ‘Walkabouts’ integrated physical activities from preschool to second grade: feasibility and effect on classroom engagement. Child Youth Care Forum. 2021;50:39–55.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Method. 2008;8:1–10.

- Anaby DR, Campbell WN, Missiuna C, et al. Recommended practices to organize and deliver school‐based services for children with disabilities: a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2019;45:15–27.

- Kurniawati F, De Boer AA, Minnaert AEM, et al. Characteristics of primary teacher training programmes on inclusion: a literature focus. Educ Res. 2014;56:310–326.

- Lee FLM, Yeung AS, Tracey D, et al. Inclusion of children with special needs in early childhood education: what teacher characteristics matter. Topics Early Child Spec Educ. 2015;35:79–88.

- Murawski WW, Hughes CE. Response to intervention, collaboration, and co-teaching: a logical combination for successful systemic change. Prevent School Fail. 2009;53:267–277.

- ] Hartmann E. Universal design for learning (UDL) and learners with severe support needs. Intern J Whole School. 2015;11:54–67.

- Lindsay S, Proulx M, Scott H, et al. Exploring teachers’ strategies for including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. Intern J Incl Educ. 2014;18:101–122.

- Calculator SN. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) and inclusive education for students with the most severe disabilities. Inter J Incl Educ. 2009;13:93–113.

- Killeen H, Shahin S, Bedell GM, et al. Supporting the participation of youth with physical disabilities: parents’ strategies. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;82:153–161.

- Maciver D, Rutherford M, Arakelyan S, et al. Participation of children with disabilities in school: a realist systematic review of psychosocial and environmental factors. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0210511.

- Ivory DM. The impact of dynamic furniture on classroom performance: a pilot study [master’s thesis]. Tacoma (WA): University of Puget Sound; 2011.

- Ramli NH, Ahmad S, Masri MH. Improving the classroom physical environment: classroom users’ perception. Proc-Soc Behav Sci. 2013;101:221–229.

- Woolner P, Clark J, Hall E, et al. Pictures are necessary but not sufficient: using a range of visual methods to engage users about school design. Learning Environ Res. 2010;13:1–22.

- Roschelle JM, Pea RD, Hoadley CM, et al. Changing how and what children learn in school with computer-based technologies. Future Child. 2000;10:76–101.

- Hutton E, Tuppeny S, Hasselbusch A. Making a case for universal and targeted children’s occupational therapy in the United Kingdom. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79:450–453.

- White H, LaFleur J, Houle K, et al. Evaluation of a school‐based transition program designed to facilitate school reentry following a mental health crisis or psychiatric hospitalization. Psychol Schs. 2017;54:868–882.

- Capp MJ. The effectiveness of universal design for learning: a meta-analysis of literature between 2013 and 2016. Inter J Incl Educ. 2017;21:791–807.

- Saad MAE. The effectiveness of a life skills training based on the response to intervention model on improving functional communication skills in children with. Autism. Inter J Psycho-Educ Sci. 2018;7:56–61.

- Hite JE, McGahey JT. Implementation and effectiveness of the response to intervention (RTI) program. Georgia School Counsel Assoc J. 2015;22:28–40.

- Brown-Chidsey R, Steege MW. Response to intervention: principles and strategies for effective practice. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2011.