Abstract

Background

Goal setting is an essential component of reablement programmes. At the same time it is also an important aspect in the evaluation of reablement from the perspective of clients.

Objectives

As part of the TRANS-SENIOR project, this research aims to get an in-depth insight of goal setting and goal attainment within reablement services from the perspective of the older person.

Material and methods

A convergent mixed methods design was used, combining data from electronic care files, and completed Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) forms with individual interviews.

Results

In total, 17 clients participated. Participants’ meaningful goals mainly focused on self-care, rather than leisure or productivity. This mattered most to them, since being independent in performing self-care tasks increased clients’ confidence and perseverance. Regarding goal attainment, a statistically significant and clinically relevant increase in self-perceived performance and satisfaction scores were observed.

Conclusion

Although most goals focused on self-care, it became apparent that these tasks matter to participants, especially because these often precede fundamental life goals.

Significance

Reablement can positively contribute to goal setting and attainment of clients and may contribute to increased independence. However, effectiveness, and subsequently long-term effects, are not yet accomplished and should be evaluated in future research.

Introduction

Many countries encourage ageing in place, which means promoting older people to remain living at home for as long as possible [Citation1–3]. Moreover, most older people prefer to remain living at home despite increasing care needs [Citation2,Citation4–6]. This is in line with the Healthy Ageing framework; the goal of the framework is to enable older people to continue to remain in their usual place of residence and avoid or delay transitions to institutional care [Citation1,Citation7]. The framework also emphasises the importance of maintaining functional ability, preserving intrinsic capacity, and creating a supportive environment to meet a person’s needs [Citation8–10]. Being able to perform meaningful daily activities creates a sense of purpose, especially when these activities take place in the community and result in social connectedness [Citation4,Citation5]. Both the physical and social environment of older people play an important role in their health and well-being, thus investing in a supportive environment, and devoting attention to how people engage with their environment becomes all the more important [Citation10,Citation11].

Reablement is a strategy to stimulate independence in an older person’s own environment. It is a person-centred, holistic approach that promotes older adults’ active participation in daily activities through social, leisure, and physical activities chosen by the older person in line with their preferences, either at home or in the community. It is delivered by an interdisciplinary team often led by an occupational therapist and/or registered nurse [Citation12,Citation13]. An important element of reablement is that individuals define their own meaningful goals together with care professionals [Citation11,Citation14]. Care professionals assist individuals in identifying their capabilities and opportunities to maximise their independence and support them in achieving their goals, through participation in daily activities, home modifications, assistive devices, and the involvement of their social network [Citation12,Citation13,Citation15–17]. Finally, it is important to monitor and evaluate the achievement of goals [Citation12,Citation18].

The evidence on the effectiveness of reablement compared with traditional home care is mixed and limited [Citation16]. While some literature reviews highlight promising results [Citation19–22], especially in terms of daily functioning, health-related quality of life, and health-care utilisation, others report significant ambiguity regarding its effects, costs, and cost-effectiveness [Citation13,Citation23–25]. The mixed results are mostly due to the fact that different outcome measures are used, making it hard to compare findings [Citation26]. Moreover, a lot of these outcome measures are generic. However, reablement is a tailored approach guided by personal goals, needs, and resources. This means that the less sensitive generic measures are not the most suitable to detect improvements in independence [Citation13].

A core component of reablement is setting personal goals and the engagement of people therein; when participants are not fully consulted regarding their reablement goals this could lead to a lack of engagement of the older person (e.g. ignored need for social connectedness during goal setting) [Citation27]. More insight is needed into what meaningful goals are and whether these goals are achieved while using reablement programmes. Despite the importance of goal setting and goal attainment in reablement services, they are often overlooked as outcome measures when evaluating reablement [Citation11,Citation28]. For example, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation29] has been found to be sensitive to measuring improvements in older people’s participation in chosen daily activities [Citation30]. However, only three reablement studies have included this outcome measure in their evaluation [Citation28]. Moreover, despite conflicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of reablement, participants’ and their carers’ experiences are mostly positive [Citation27,Citation31,Citation32]. Therefore, in a person-centred approach, it is recommended to evaluate changes and gains experienced by older people by using qualitative research methods.

Despite its critical role, goal setting and goal attainment are often neglected as outcome measures. Moreover, combining and integrating both the quantifiable effects regarding goal attainment and the person’s experiences regarding both goal setting and attainment, comprehensively captures clients’ progress and perceptions, shedding light on the effects of reablement services beyond mere quantitative metrics. Therefore, this research aims to get an in-depth insight of goal setting and goal attainment within reablement services from the perspective of the older person.

Material and methods

Study design

This study entails a convergent mixed-methods design [Citation33], meaning that both qualitative data (individual interviews to gain an in-depth insight into clients’ experiences with the goal-oriented approach) and quantitative data (regarding goal setting and goal attainment scores) were collected and analysed simultaneously. Subsequently, both analyses were compared and results were integrated. The integration involved merging the results from the quantitative and qualitative data so that a comparison could be made and a more complete understanding is obtained than that provided by the quantitative or the qualitative results alone [Citation33]. Data collection and analysis took place during the period March 2022 and May 2023.

Setting

The study took place in the Netherlands, more specifically the ‘Longer Vital at Home’ (LVaH) reablement programme was evaluated at one care provider in the province of North Holland in cooperation with the local municipality. The long-term care organisation provides home care (i.e. district nursing and domestic care), primary care (i.e. allied health), social care, inpatient geriatric rehabilitation and residential care.

Intervention: Longer Vital at Home

LVaH is a community-based interdisciplinary reablement programme to promote self-management and self-reliance of community-dwelling older adults. LVaH is based on the principles of I-MANAGE, a model for a reablement approach tailored to the Dutch home care setting. The model provides guidance and structure for implementation in different local care contexts and leaves room for tailoring to the specific needs and resources of the organisation and the needs of care receivers [Citation18]. LVaH is intended for community-dwelling older adults with care needs regarding self-care, mobility, household activities and/or well-being. Exclusion criteria are lack of motivation, terminal illness or receiving end-of-life care, planned nursing home admission, complex cognitive problems, or a care need which only requires technical nursing skills (e.g. complex wound care). An interdisciplinary team consisting of occupational therapists (OTs), district nurses, registered nurses, certified nursing assistants, physical therapists (PTs), domestic support workers and community consultants from the municipality join forces to promote the self-management and self-reliance of participants. This may entail activities of daily living (e.g. self-care activities, household chores) as well as mobility and well-being activities either at home or in the community, depending on the older adult’s personal goals. The programme lasts up to 12 weeks and has 5 phases. After programme referral by district nurses, community consultants from the municipality, or the general practitioner (GP) (Phase 1), the OT visits the participant together with the community consultant or district nurse for a comprehensive assessment (Phase 2). Based on the principles of Positive Health [Citation34], both the current level of self-management and self-reliance is examined, as well as gaining insight into what the older adult’s wishes are and what they value in life. If necessary, additional assessments (e.g. environmental assessment) or a conversation with the family caregiver may take place. Next, the OT conducts the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation29] to identify the older adult’s personal goals, and draws up a tailored support plan together with the older adult and the reablement team (Phase 3). The LVaH team then delivers care and support according to the support plan (Phase 4). Interventions that could be deployed include training of daily activities, using helping aids, home modification and health-care technology (e.g. telemedicine) or informal caregiver support. Depending on the goals of the older adult, other disciplines may be involved, for instance welfare staff, social workers, or dieticians. Family caregivers and the older adult’s social network are also closely involved in the process. The core team (OT, district nurse, community consultant, domestic support planner) have weekly interdisciplinary meetings to discuss progress. Based on these meetings, the team determines whether the care plan should be continued or adjusted, which is then discussed with the participant. A final evaluation takes place at the end of the programme, including the reassessment of the COPM [Citation29] by the OT to see whether clients achieved their goals or need referral to follow-up care (Phase 5). Three months after the end of the programme, there is a follow-up with the older adult.

Participants

All LVaH participants who enrolled in the programme between March 2023 and December 2023 were eligible to participate in the study. To participate in the interviews, they had to be able to communicate in Dutch. Participants were approached by one of the OTs of the LVaH team. The OT explained the purpose and method of the study and asked clients if they were interested in participating. Interested clients additionally received a patient information letter and signed a consent form to participate in the study. Participants’ contact details were then shared with the researcher (IM). It was anticipated that 30 clients would enrol in the LVaH programme. Eventually, 17 clients participated in the study of whom 9 were interviewed at the end ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

Data collection

Data were collected using three data collection methods: electronic care files (ECFs) of participants; COPM [Citation29] forms completed by care professionals together with participants; and semi-structured interviews with a subsample of participants. Socio-demographic characteristics (i.e. age, sex, living situation, and marital status) from participants were collected through their ECFs. Additionally, the route of referral to the programme (i.e. through the general practitioner (GP), district nurse, or community consultant from the municipality) was tracked in a logbook by care professionals.

Quantitative data on goal setting and goal attainment was gathered through the completed COPM [Citation29] forms, i.e. the number of goals, type of goals, and patients’ perceived performance and satisfaction scores. The COPM [Citation29] was structurally embedded in the LVaH programme and conducted by the occupational therapist at baseline and after approximately 12 weeks (i.e. at the end of the programme). The COPM [Citation29] consists of a semi-structured interview, in which the participant is encouraged to identify problems they experience during daily activities, categorised into self-care, productivity and leisure. Self-care consists of personal care (e.g. dressing, bathing), functional mobility (e.g. transfers indoor or outdoor), and community management (e.g. transportation, shopping. Productivity consists of (un)paid work (e.g. volunteering), household management (e.g. cleaning, laundry), and play or school (e.g. homework). Leisure consists of quiet recreation (e.g. hobbies, crafts), active recreation (e.g. sports, travel), and socialisation (e.g. visiting, phone calls). The client scores the five most important problems on a scale of 1 to 10 in terms of performance and satisfaction. Subsequently, the total score is calculated by summing up all performance or satisfaction scores and dividing the sum by the number of problems. After the reassessment, the change in both the performance and the satisfaction scores was calculated by subtracting the score from the reassessment from the score from the initial assessment.

Simultaneously, the project leader (SvH) conducted semi-structured interviews with a subsample of the participants. Participants did not know the project leader beforehand. The subsample was selected based on whether the participants completed the programme and agreed to participate in the interview. Participants were approached to participate in the interviews and included until data saturation was reached. Data saturation was considered achieved when no new themes or codes were identified. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide, which included topics such as the care they received during the programme, how they experienced receiving the programme and more specifically the goal-setting aspect of the programme (i.e. how they perceived the process on working towards reaching these goals). The interviews took place at the place of participant’s residence. The duration of the interviews ranged from 14 to 45 min and lasted 24 min on average. The full interview guide is available in Appendix A. All interviews were audio-recorded. Furthermore, the reablement process of one participant was explored and described more in detail (Box 1). We wanted to describe the process and results from start to finish. Therefore, we collected data on the background of this participant, the goals that were set, the actions that were performed to achieve these goals, the progress of this participant, and their end result. These data were gathered through the ECF of this participant, the completed COPM [Citation29] form, and an individual interview with the participant.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25). Firstly, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and percentages) were used to describe the background characteristics of participants. Secondly, change scores regarding performance and satisfaction were calculated to assess whether a client has achieved his or her goals. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to compare both the COPM [Citation29] performance and satisfaction score at the start of the programme and the end of the programme, and to test the statistical significance of change scores. A change score of 2 points on satisfaction or performance was deemed a clinically relevant difference as it is a widely used cut-off in literature and no other cut-off points have yet been defined [Citation35,Citation36].

Data regarding the type of goals that were set by participants were collected and classified according to the predefined (sub-)categories as described in the COPM manual [Citation29] by researcher IM. This classification was discussed within the research team and adapted when needed, for example, when there was any doubt to which (sub-)category a goal belonged.

Qualitative data derived from the interviews were anonymized, transcribed verbatim, and analysed with support from the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti Windows (Version 23.0.8). A thematic analysis approach was used, following the steps identified by Braun and Clarke [Citation37]. A combination of open and axial coding was used. First, two researchers (IM & SM) read the transcripts several times to familiarise themselves with the data. They also made notes to mark sections of the transcripts that could be relevant to answer the research question, for example, parts of the interview that contributed to understanding goal setting and goal attainment from the perspective of the participant. Subsequently, open coding was used to analyse the data. Both researchers (IM & SM) independently coded the first transcript by creating open codes which were close to the original transcript text. The codes were compared for similarity and differences were discussed. Afterwards, researcher IM coded the other transcripts in a similar manner. Relationships between codes were identified by means of axial coding; initial codes were organised under potential themes and similar codes were collated. These themes were reviewed within the research team and, keeping the research questions in mind, axial coding led to the final themes. The analysis was an iterative process during which initial codes were recoded and relationships and themes were revised. Disagreements were discussed within the research team.

After analysing both quantitative and qualitative data, we triangulated out findings to create cohesive results. We started with the quantitative findings and complemented these with relevant parts of our qualitative analysis to fit the main focus of the research aim, being goal setting and goal attainment. Therefore, we opted to include the qualitative analysis as an Appendix (Appendix B), which presents the code tree, so more insight into the qualitative analysis and the (sub)themes derived can be found here.

Ethics

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Maastricht University, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (approval number FHML-REC/2022/054). Participants voluntarily signed informed consent after they were fully informed about the purpose and procedures of the study and had the opportunity to ask additional questions or raise any concerns. The informed consent stated that participation in this study was completely voluntary and withdrawal from the study was possible at any moment, with or without providing a reason, by contacting one of the researchers. The informed consent also stated explicitly that their participation in or withdrawal from the study would not affect the service they received by any means.

Results

In total, 17 clients participated in the study. The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are displayed in . Thirteen participants finished the full reablement programme during the study period; one was still in the programme at the end of data collection with no perspective on when this would be finished. Three participants dropped out of the programme. Reasons for dropout were: not being able to formulate goals (n = 2) and deterioration of health status (n = 1). Nine participants were interviewed.

The following sections first presents the findings related to goal setting and subsequently the findings related to goal attainment. Both sections start with a presentation of the quantitative results, which are then complemented by qualitative findings that were relevant and related to the quantitative results, meaning that not all (sub)themes are described in detail in the result section. More insight into the qualitative analysis and the themes derived can be found in Appendix B. Additionally, an example case is presented at the end of the result section.

Goal setting

In total, 15 out of 17 participants were able to set goals at the start of the programme. In total, these participants formulated 62 goals. On average, 4.2 (SD = 1.15) goals per participant were formulated. An overview of the goals that were set by participants classified according to the (sub-)categories of the COPM [Citation29] are listed in . Overall, most goals were related to self-care (n = 39), followed by leisure (n = 14), and productivity (n = 9) ().

Figure 1. Bar chart presenting the classification of goals set by participants. The bar chart displays the number of goals set within each category of the COPM [Citation29] (i.e. leisure, productivity, and self-care). All categories are divided into sub-categories each presented with the number of goals set.

![Figure 1. Bar chart presenting the classification of goals set by participants. The bar chart displays the number of goals set within each category of the COPM [Citation29] (i.e. leisure, productivity, and self-care). All categories are divided into sub-categories each presented with the number of goals set.](/cms/asset/99e2e341-5165-4776-8054-70ef8d078053/iocc_a_2356548_f0001_c.jpg)

Table 2. Overview of the goals that were set by participants classified according to the (sub-)categories of the COPM [Citation29].

Regarding setting goals, participants mentioned that they felt heard and could express all their needs. Additionally, they felt that the care professionals supported them throughout this process and helped them to focus on their possibilities and what they were still able to do. Participants indicated that the goals that were set were in line with their wishes. So despite of the holistic nature of reablement, most goals were focused on self-care. In the interviews participants mentioned that these activities were important to them, as they contributed to their well-being and quality of life. Being less dependent during self-care meant that they were able to remain living at home for as long as possible, and that they did not have to rely on others. These were also the motivations for participants to enrol in the programme and were therefore reflected in the goals that were set. Other reasons for participating were being able to (re-)do the things they loved, staying active, and receiving the right care. These reasons reflect the underlying principles of reablement and may indicate how participants were convinced of the benefits of the programme.

And if it’s too much for you, you can say so. But yes, [the occupational therapist] also listened so well, […] She picked up things between the lines anyway. (Participant, 73, F)

For a very long time, I couldn’t do what I always wanted to do. […] Couldn’t cut my own nails and peel an apple anymore, my husband had to do these things for me… All that fell away, then you only have a small world left. […] Having my nails cut by someone else is terrible to me, those are things I really wanted to do again, those were very important things to me. (Participant, 72, F)

Well look, if I sit in a chair all day and nurses take care of me, then I myself suffer. I then only deteriorate because I sit all day. (Participant, 91, M)

Goal attainment

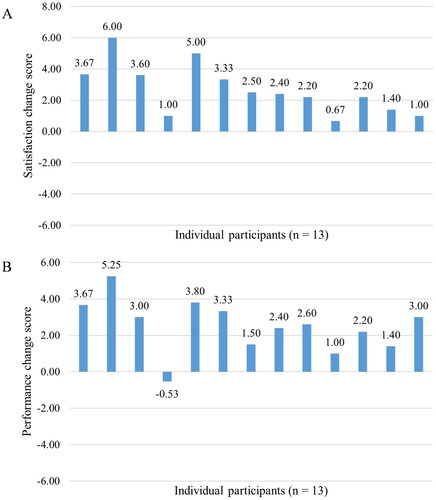

Regarding goal attainment, 13 out of 15 COPM [Citation29] reassessments were completed. Three (re-) assessments were missing scores for some goals. There was a significant increase in the performance score after completing the programme (Mdn = 6.25) compared to at the start of the programme (Mdn = 4.2); Z = −3.11, p = 0.002. Additionally, there was a significant increase in the satisfaction score after completing the programme (Mdn = 6.67) compared to at the start of the programme (Mdn = 4.33); Z = −3.18, p < 0.001). When looking at the individual change scores, nine participants had a change score greater than two on both performance and satisfaction, indicating a clinically relevant difference. presents the individual change scores on performance as well as satisfaction.

Figure 2. Column chart presenting the individual change scores of participants (n = 13) for both performance (A) and satisfaction (B).

These results are in line with the experiences of participants regarding goal attainment. Most participants mentioned that they did reach (some of) their goals and that they were also able to maintain this. They expressed that by participating they gained in confidence, perseverance, and independence. They also mentioned that they had become more self-reliant, that it made their life easier and that it gave them more freedom. This related to the clinically relevant change score of 2 or higher and was also reflected in the individual interviews. This may indicate that working towards and achieving personal goals has a lasting impact on participants.

I always say it gives me a lot of freedom. That may sound very strange, but it really gives a lot of freedom. (Participant, 72, F)

Well, I no longer have that many goals at 91. But at least now I can get by in the household and with the grandchildren. And you may smell it, I am making a nice bowl of soup again. […] I am convinced I will keep doing what I have learnt. (Participant, 91, M)

Several strategies and interventions were used by the reablement team to reach goals; mostly participants mentioned the use of assistive devices. Other strategies were providing information and advice, for example how to order food online or which financial aid options are available to them through the municipality.

They found out that my walker was actually not good at all. Now I have one of those walkers with elbow rests. […] With the other one, I really had to sit down after a while. Pain in my shoulders, my elbows, my wrists. Had to sit. I can really walk for hours now without having to sit. She [the occupational therapist] helped me tremendously with that. (Participant, 66, F)

Additionally, some clients received help from a physical therapist, providing them with exercises and helping them to regain their functional mobility and staying active so that they, for example, will be able to walk their dog. The involvement of the social network to work towards goals was mixed. Some participants mentioned that their children and neighbours were involved, whilst others mentioned there was no specific attention for family caregivers, which was also not desired by these participants.

Moreover, participants indicated they appreciated the personal attention and practical help they received. They clearly felt well-supported by care professionals in reaching their goals. For example, they mentioned it was pleasant that they did not have to reinvent the wheel and care professionals proactively looked for the right solutions. The participants appreciated the type and amount of support, which resulted in a feeling of trust in the team’s professionalism and put participants at ease. They felt that the reablement team had everything under control.

I liked it so much that I didn’t always have to invent the wheel myself, but that the occupational therapist was there. […] She knew all the ways and also arranged it for you. It saved me so much energy. Yes, I loved that so much. (Participant, 72, F)

Box 1. Description of a real-life ‘Longer Vital at Home’ trajectory.

This box provides an example (Marie, a pseudonym) and detailed description of a completed ‘Longer Vital at Home’ trajectory from start to finish by means of a specific case.

Background information

Marie is a 72-year-old woman living in a ground floor apartment with her husband. Due to a recent hand operation, she feels limited in performing daily activities. At the moment, Marie receives home care twice a week for showers and daily help with compression socks. Once a week, she also gets assistance with heavier tasks like vacuuming. She can manage light chores like folding laundry and uses a walker indoors, while her mobility scooter allows her to do light grocery shopping. Marie is a very social person. She was a taxi driver for over 30 years and served as a volunteer afterwards. She is also a member of the residents committee of the community she resides in. She is an active community member, participating in activities like cards, coffee chats, and crafting, although her recent hand operation has made crafting challenging.

Setting personal goals

During their initial conversation, Marie expressed her desire to assist her husband more with household tasks, resume driving, and return to crafting. She also mentioned her wish to participate in community activities on foot instead of using her mobility scooter. Following this conversation, the OT conducted the COPM [Citation29] and set five personal goals with Marie: 1) crafting; 2) (un)loading the dishwasher; 3) clearing the table; 4) driving her car; and 5) clipping her own nails. She mentioned she really missed the crafting activities that were organised in the community, but due to the pain she experiences in her hand she is unable to do this anymore. Additionally, she wanted to ease her husband’s burden by (un)loading the dishwasher by herself. Lastly, she mentioned that she hates it when other people have to clip her nails and would like to be able to do this by herself again.

Working towards her goals

Marie worked on her goals with the reablement team, receiving advice from the OT, like placing her cup in the sink while pouring boiling water instead of on the countertop. The OT also recommended assistive devices such as a custom nail clipper, suitable clothes pegs, and a vegetable peeler. After training and using these devices for a few weeks, Marie showed visible improvement in several tasks. The home care team also assisted her in relearning to dress herself, and the OT found ways to support her in returning to crafting, such as applying a thickening on the crochet hook which made it easier for Marie to hold it.

Achieving goals

After three months, the OT conducted a final assessment of Marie’s goals using the COPM [Citation29]. She had made significant progress, with an average change score of 5.25 for performance and 6 for satisfaction. Marie found the thickening of the crochet hook very helpful. She felt more independent, especially with loading the dishwasher, but on her doctor’s advice couldn’t resume driving. Marie was thankful that she had participated in the programme and said ‘I can manage myself, I matter again’. At the three month follow-up, Marie mentioned that she still experiences a lot of pain in her right hand, making it harder to perform some of the activities trained before. However, she still very grateful for the things that she has learned during the programme. She is still able to perform most of the activities and is happy with the devices and advice that she received.

Discussion

This research aimed to get an in-depth insight of goal setting and goal attainment within reablement services from the perspective of the older person. Participants appreciated the programme and its personalised and practical approach. It helped them to set clear goals that were in line with their preferences, which were mainly self-care related. Most participants reached their goals and indicated several personal gains they had obtained from participating in the programme (e.g. self-reliance, confidence, independence).

With regard to setting goals, our findings show that the majority of the goals set were on self-care level, more specifically, personal care and functional mobility, which is in line with previous research [Citation30,Citation32]. Several authors claim that more attention should be paid to social needs, social connectivity and leisure activities in reablement programmes, as it is assumed that these are the most meaningful activities for older adults [Citation15,Citation32,Citation38]. It has been argued that the lack of focus on social needs may be in line with governmental priorities since investing in those needs does not necessarily reduce dependency on ongoing care and support services [Citation27,Citation39]. However, our research underlines that the setting of self-care goals aligned with the wishes and preferences of older adults. Despite reablement’s broader focus on meaningful activities and well-being, participants emphasised that self-care tasks were crucial to their well-being and quality of life. Self-care is associated with staying at home longer without relying on others. Performing self-care activities in one’s own home is important for people to view themselves as an independent person [Citation40]. Previous research argues that goals set by older people do not necessarily need to be ‘big’, meaning that independence in ‘simple’ activities, such as self-care, increases the participant’s self-confidence [Citation40,Citation41]. It is more than merely the task of showering, for example, but also about their subjective experience; they want to remain autonomous and being able to manage their everyday life, which contributes to their quality of life [Citation31,Citation42]. This is also reflected in the WHO’s Healthy Ageing framework, which defines Healthy Ageing as ‘the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age’ [Citation43], and is seen as fostering an individual’s functional ability to be and do what they value [Citation8]. Often people have multiple types of goals (i.e. care or medical-related goals, and fundamental or life goals), which all contribute to a person’s well-being and quality of life [Citation44,Citation45]. However, smaller, more specific, targeted care goals are a necessity to achieve fundamental goals and cannot be neglected when providing person-centred care [Citation45,Citation46].

Our findings indicated that most participants at the end of the programme achieved the goals that were set at the beginning and that they believe they will be able to maintain performing these activities. This was reflected in both statistically significant and clinically relevant change scores in self-assessed performance and satisfaction of valued activities in everyday life. Moreover, interviews with participants showed that they gained in confidence, perseverance, freedom, and independence, and became more self-reliant. Within reablement, it is important that participants formulate their goals themselves in line with their own preferences, with the necessary support of the reablement team. Moe and Brinchmann [Citation41] emphasise the importance of service users setting their own goals at their own pace to maintain motivation. Similarly, Hjelle et al. [Citation47] found that allowing users to define goals without restrictions boosts intrinsic motivation. Involving service users in goal setting, as noted by Rose et al. [Citation48], enhances confidence and a sense of ownership. Mulquiny and Oakman [Citation27] highlight the significance of setting goals that were in line with their meaning of independence for the success of reablement. Our findings regarding self-assessed performance and satisfaction of meaningful activities in everyday life are in line with previous research [Citation36,Citation49], which were both larger trials (i.e. n = 61 and n = 828 respectively) and used the COPM [Citation29] as the primary outcome measure. Both studies found significant improvements in self-perceived performance and satisfaction scores, although it is unclear whether these effects were sustained long-term [Citation26,Citation36,Citation49]. Nevertheless, these promising findings could be an indication that reablement may offer a solution to address the needs of an ageing population, such as increasingly complex care needs, the shift from in-patient to home-based care, and the growing pressure on financial and workforce resources in long-term care [Citation1,Citation50–52].

Some methodological considerations have to be made. First, the sample for this study only entails 17 participants of which not all completed the full programme. It is therefore important to interpret the quantitative findings with the necessary caution, since small sample sized tend to overestimate effect sizes [Citation53]. Second, it is possible that only highly motivated and enthusiastic people were included in our study, leaving out the more critical voices, because these people will likely not enrol in a reablement programme in the first place (e.g. lack of willingness or motivation), which could lead to more positive experiences and effects [Citation42]. Moreover, participants were approached by the OT member of the reablement team, which could also lead to selection bias. However, an information session took place with the OTs before the start of the study to explain the process in detail to make sure they did not select participants beforehand based on their assessment of whether clients would want or be able to participate. Additionally, we asked the participants about their experiences retrospectively, which may induce recall bias. Previous research has also shown that reflecting on their trajectory and personal gains after they have experienced improvement in functioning and daily life could lead to a more positive view of their perceived trajectory [Citation42]. We used the COPM [Citation29] as a measurement for goal attainment (i.e. self-assessed performance and satisfaction scores). There is, however, insufficient evidence for the cut-off value of 2 points being a clinically relevant change, despite this being used in multiple studies [Citation35,Citation36]. However, because of the triangulation and mixed-methods design, the statements from participants formed an additional validation for our findings regarding clinical relevance. Additionally, the COPM [Citation29] is preceded with an extensive intake conversation exploring what is meaningful to the participant. Performing this initial conversation could have a therapeutic effect and could motivate and convince participants to look for and work towards suitable solutions for their problems themselves [Citation36,Citation49], which could diminish the effects of the reablement programme as a whole.

This study has some implications for future research and practice. Our research showed positive experiences and promising results regarding goal setting and goal attainment in reablement. However, it is still necessary to conduct more robust trials to investigate its effectiveness. Additionally, previous research has shown that participants may experience the end of reablement services as abrupt and often fall back into the care-dependent model afterwards, losing all gains previously achieved [Citation27,Citation41]. Therefore, more research needs to be conducted to investigate the long-term effects of reablement. For practice, it would be beneficial to invest in the sustainability and maintenance of the achieved gains in the shape of long-term follow-up. Additionally, where people are referred back to usual care after the reablement services, it is important to invest in the training of these care professionals so that the obtained gains are not lost. Second, an important finding both in our study as well as in previous literature is the lack of focus on social needs and wishes, especially in the light of fundamental life goals succeeding the necessary care goals. More attention needs to be provided on both these aspects within reablement services, and care professionals need to be trained and supported herein.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Maastricht University, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (approval number FHML-REC/2022/054).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Woonzorggroep Samen for their collaboration within this project. Additionally, we would like to thank all clients who participated in the reablement programme as well as in the research.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy or consent of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA, et al. The world report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet. 2016;387(10033):1–14. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4.

- Rostgaard T, Glendinning C, Gori C, et al. Livindhome: living independently at home: reforms in home care in 9 European countries. Copenhagen: SFI - Danish National Centre for Social Research; 2011.

- Forsyth A, Molinsky J. What is aging in place? Confusions and contradictions. Housing Policy Debate. 2021;31(2):181–196. doi:10.1080/10511482.2020.1793795.

- Bigonnesse C, Chaudhury H. The landscape of “aging in place” in gerontology literature: emergence, theoretical perspectives, and influencing factors. J Aging Environ. 2020;34(3):233–251. doi:10.1080/02763893.2019.1638875.

- Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, et al. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist. 2012;52(3):357–366.

- Kuluski K, Ho JW, Hans PK, et al. Community care for people with complex care needs: bridging the gap between health and social care. Int J Integr Care. 2017;17(4):2.

- World Health Organization. Age-friendly environments in Europe: a handbook of domains for policy action. 2017.

- World Health Organization. Decade of healthy ageing 2020-2030. 2020.

- Bosch-Farré C, Malagón-Aguilera MC, Ballester-Ferrando D, et al. Healthy ageing in place: enablers and barriers from the perspective of the elderly. A qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6451.

- Beard JR, Araujo de Carvalho I, Sumi Y, et al. Healthy ageing: moving forward. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(11):730.

- Tuntland H, Parsons J, Rostgaard T. 2: perspectives on institutional characteristics, model features, and theories of reablement. In: Rostgaard T, Parsons J, Tuntland H, editors. Reablement in long-term care for older people: international perspectives and future directions. Bristol: Policy Press; 2023:21–45.

- Metzelthin SF, Rostgaard T, Parsons M, et al. Development of an internationally accepted definition of reablement: a delphi study. Ageing Soc. 2022;42(3):703–718. doi:10.1017/S0144686X20000999.

- Buma LE, Vluggen S, Zwakhalen S, et al. Effects on clients’ daily functioning and common features of reablement interventions: a systematic literature review. Eur J Ageing. 2022;19(4):903–929. doi:10.1007/s10433-022-00693-3.

- Azim FT, Burton E, Ariza-Vega P, et al. Exploring behavior change techniques for reablement: a scoping review. Braz J Phys Ther. 2022;26(2):100401.

- Doh D, Smith R, Gevers P. Reviewing the reablement approach to caring for older people. Ageing Soc. 2019;40(6):1371–1383. doi:10.1017/S0144686X18001770.

- Aspinal F, Glasby J, Rostgaard T, et al. New horizons: reablement - supporting older people towards independence. Age Ageing. 2016;45(5):572–576. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw094.

- Metzelthin SF, Zijlstra GA, van Rossum E, et al. Doing with …’ rather than ‘doing for …’ older adults: rationale and content of the ‘stay active at home’ programme. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(11):1419–1430. doi:10.1177/0269215517698733.

- Mouchaers I, Verbeek H, Kempen GIJM, et al. Development and content of a community-based reablement programme (I-MANAGE): a co-creation study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(8):e070890. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070890.

- Sims-Gould J, Tong CE, Wallis-Mayer L, et al. Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation and restorative interventions With older adults in receipt of home care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(8):653–663. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.070.

- Ryburn B, Wells Y, Foreman P. Enabling independence: restorative approaches to home care provision for frail older adults. Health Soc Care Commun. 2009;17(3):225–234. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00809.x.

- Tessier A, Beaulieu M-D, McGinn CA, et al. Effectiveness of reablement: a systematic review [efficacité de l’autonomisation: une revue systématique]. Healthcare Pol. 2016;11(4):49–59.

- Pettersson C, Iwarsson S. Evidence-based interventions involving occupational therapists are needed in re-ablement for older community-living people: a systematic review. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(5):273–285.

- Cochrane A, Furlong M, McGilloway S, et al. Time-limited home-care reablement services for maintaining and improving the functional independence of older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:cd010825.

- Legg L, Gladman J, Drummond A, et al. A systematic review of the evidence on home care reablement services. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(8):741–749. doi:10.1177/0269215515603220.

- Whitehead PJ, Worthington EJ, Parry RH, et al. Interventions to reduce dependency in personal activities of daily living in community dwelling adults who use homecare services: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(11):1064–1076. doi:10.1177/0269215514564894.

- Lewin G, Parsons J, O’Connell H, et al. 5: does reablement improve client-level outcomes of participants? An investigation of the current evidence. In: Rostgaard T, Parsons J, Tuntland H, editors. Reablement in long-term care for older people: international perspectives and future directions. Bristol: Policy Press; 2023. p. 93–117.

- Mulquiny L, Oakman J. Exploring the experience of reablement: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis of older people’s and carers’ views. Health Soc Care Commun. 2022;30(5):e1471–e1483. doi:10.1111/hsc.13837.

- Tuntland H, Doh D, Ranner M, et al. 6: examining client-level outcomes and instruments in reablement. In: Rostgaard T, Parsons J, Tuntland H, editors. Reablement in long-term care for older people: international perspectives and future directions. Bristol: Policy Press; 2023. p. 118–136.

- Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, et al. The Canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1990;57(2):82–87. doi:10.1177/000841749005700207.

- Tuntland H, Kjeken I, Folkestad B, et al. Everyday occupations prioritised by older adults participating in reablement. A cross-sectional study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(4):248–258.

- Bergström A, Vik K, Haak M, et al. The jigsaw puzzle of activities for mastering daily life; service recipients and professionals’ perceptions of gains and changes attributed to reablement - A qualitative meta-synthesis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2023;30(5):604–615.

- Wilde A, Glendinning C. ‘If they’re helping me then how can I be independent?’ The perceptions and experience of users of home-care re-ablement services. Health Soc Care Commun. 2012;20(6):583–590. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01072.x.

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Chapter 3: core mixed methods designs. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2017. p. 51–99.

- Huber M, van Vliet M, Giezenberg M, et al. Towards a ‘patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010091. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010091.

- McColl MA, Denis CB, Douglas KL, et al. A clinically significant difference on the COPM: a review. Can J Occup Ther. 2023;90(1):92–102. doi:10.1177/00084174221142177.

- Tuntland H, Aaslund MK, Espehaug B, et al. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):145. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0142-9.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Magne TA, Vik K. Promoting participation in daily activities through reablement: a qualitative study. Rehabil Res Pract. 2020;2020:6506025–6506027. doi:10.1155/2020/6506025.

- Stausholm MN, Pape-Haugaard L, Hejlesen OK, et al. Reablement professionals’ perspectives on client characteristics and factors associated with successful home-based reablement: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):665. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06625-8.

- Haak M, Fänge A, Iwarsson S, et al. Home as a signification of independence and autonomy: experiences among very old swedish people. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14(1):16–24. doi:10.1080/11038120601024929.

- Moe C, Brinchmann B. Optimising capasities. A service user and caregiver perspective on reablement. Ground Theory Rev. 2016;15:25–40.

- Jokstad K, Hauge S, Landmark BT, et al. Control as a core component of user involvement in reablement: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1079–1088. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S269200.

- World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Schellinger SE, Anderson EW, Frazer MS, et al. Patient self-defined goals: essentials of person-centered care for serious illness. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(1):159–165. doi:10.1177/1049909117699600.

- Vermunt NP, Harmsen M, Elwyn G, et al. A three-goal model for patients with multimorbidity: a qualitative approach. Health Expect. 2018;21(2):528–538.

- Boeykens D, Boeckxstaens P, De Sutter A, et al. Goal-oriented care for patients with chronic conditions or multimorbidity in primary care: a scoping review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0262843. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262843.

- Hjelle KM, Tuntland H, Førland O, et al. Driving forces for home-based reablement; a qualitative study of older adults’ experiences. Health Soc Care Commun. 2017;25(5):1581–1589. doi:10.1111/hsc.12324.

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):65–75. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.030.

- Langeland E, Tuntland H, Folkestad B, et al. A multicenter investigation of reablement in Norway: a clinical controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):29. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1038-x.

- Rostgaard T, Tuntland H, Parsons J. 1: introduction: the concept, rationale, and implications of reablement. In: Rostgaard T, Parsons J, Tuntland H, editors. Reablement in long-term care for older people: international perspectives and future directions. Bristol: Policy Press; 2023. p. 3–20.

- Oliver D, Foot C, Humphries R. Making our health and care systems fit for an ageing population. London: King’s Fund London; 2014.

- Zingmark M, Tuntland H, Burton E. 7: reablement as a cost-effective option from a health economic perspective. In: Rostgaard T, Parsons J, Tuntland H, editors. Reablement in long-term care for older people: international perspectives and future directions. Bristol: Policy Press; 2023. p. 137–160.

- Van Calster B, Steyerberg EW, Collins GS, et al. Consequences of relying on statistical significance: some illustrations. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(5):e12912. doi:10.1111/eci.12912.

Appendix A

Semi-structured interview guide

Could you tell us a little more about yourself (age, children …)?

Recently, you have received a new form of care, namely the ‘Longer Vital at Home’ programme. During this programme, the team worked with you on your personal goals;

Can you tell me a bit more about the care you received during this period?

What was it like for you to set goals together with the occupational therapist?

How did the team work towards these goals with you?

How did you experience this goal-oriented care?

What did you found positive?

What did you found negative?

What helped you work on your personal goals?

Can you elaborate a little more about that?

What prevented you from working on your personal goals?

Can you elaborate a little more about that?

Looking back on the past period, what do you think could be improved?